Abstract

1,3-Beta-d-glucan (β-glucan) is a component of mold cell walls and is frequently found in fungi and house dust mites. The studies of β-glucan are inconsistent, although it has been implicated in airway adverse responses. This study was carried out to determine whether airway hyperresponsiveness was seen 24 h after airway exposure to β-glucan in guinea pigs. Two matching guinea pigs were exposed intratracheally to either β-glucan or its vehicle. Twenty-four hours after intratracheal instillation, there was no difference between these two groups in the baseline of the total pulmonary resistance (RL), dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn), arterial blood pressure, and heart rate. In contrast, the responses of RL to capsaicin injection were significantly increased in β-glucan animals; capsaicin at the same dose of 3.2 μg/kg increased RL by 184% in vehicle animals and by 400% in β-glucan animals. The effective dose 200% to capsaicin injection was lower in the β-glucan animals. Furthermore, the increases in RL were partially reduced after transient lung hyperinflation to recruit the occluding airways; however, the RL induced by capsaicin injection after lung hyperinflation was significantly larger than the baseline in β-glucan animals; also, the lung wet-to-dry ratio in capsaicin-injected animals was augmented in the β-glucan group. Moreover, the airway hyperresponsiveness was accompanied by increases in neutrophils in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in the β-glucan animals. Furthermore, the levels of substance P and the calcitonin gene-related peptide in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid collected after capsaicin injection were increased in β-glucan animals. We provide definitive evidence that β-glucan can induce airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs, and the neuropeptide releases play an important role in this airway hyperresponsiveness.

Keywords: airway hyperresponsiveness, airway inflammation, bronchoconstriction, capsaicin, glucan

Environmental allergen exposure is known to play a major role in the development and exacerbation of asthma. 1,3-Beta-d-glucan (β-glucan) is an airborne biohazard that originates mainly in fungal cell walls.1,2 It has been reported that the β-glucan level is significantly elevated in patients with airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation.1,3 In addition, β-glucan exacerbated allergic airway inflammation responses to house dust mite allergen during both sensitization and challenge.4 On the other hand, β-glucan has been shown to exert beneficial therapeutic effects in several diseases and prevent airway hyperreactivity and pulmonary inflammation in the murine asthma model.5,6 Thus, the role of β-glucan in airway diseases is still inconsistent and controversial.

Airway hyperresponsiveness, characterized by exaggerated bronchomotor responses to various nonspecific inhaled stimuli, is the main feature of bronchial asthma. Other exaggerated characteristics include cough, airflow obstruction, and airway inflammation;7−10 all of these have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma induced by several airway insults such as endotoxin,1 cigarette smoke,11 and environmental allergens.12

A recent study carried out in our laboratory has shown that airway hypersensitivity induced by β-glucan exposure is mediated primarily through the sensitization of pulmonary C-fiber afferents via TRPA1 and dectin-1 receptors.13 Furthermore, stimulation of these nonmyelinated afferents is known to evoke bronchoconstriction reflexes via the cholinergic pathway14 and elicit a local release from these afferent endings of neuropeptides, which can induce more intense bronchoconstriction reflexes.15,16

Whether lung exposure to β-glucan causes airway hyperresponsiveness remains unknown. Because airway inflammation has been implied to increase the sensitivity of C-fiber afferents,17 it is highly possible that the mechanism of airway hyperresponsiveness induced by β-glucan exposure may involve activation and sensitization of these C-fiber afferents, and the same level of stimulus will make it easier to fire for the C-fiber afferents and induce more intense bronchoconstriction responses.18,19 In this study, we therefore determined the airway hyperresponsiveness induced by β-glucan exposure in guinea pigs.

Results

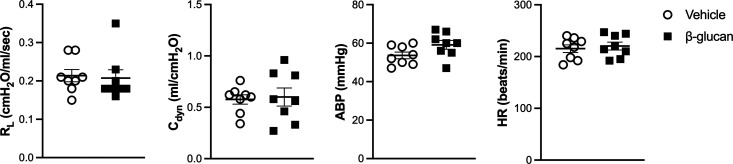

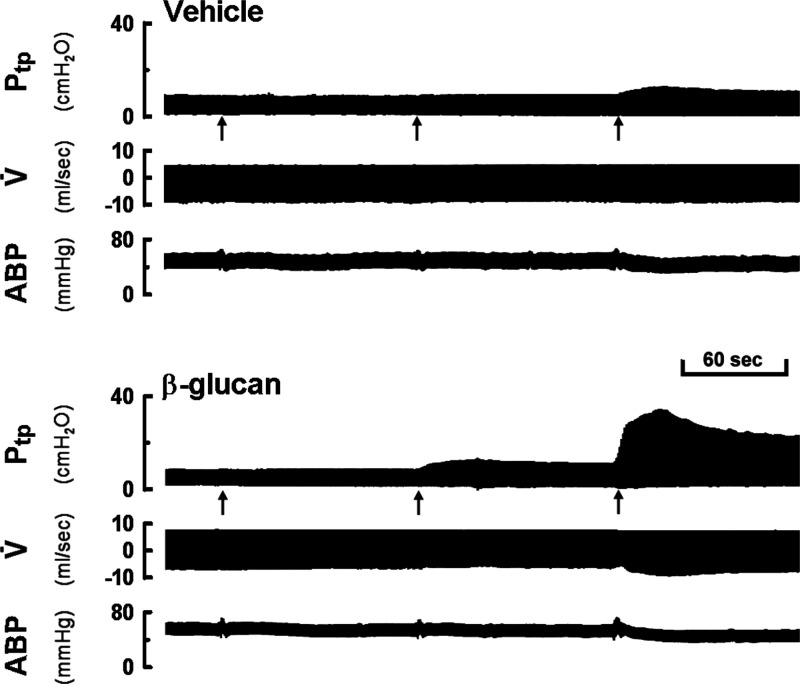

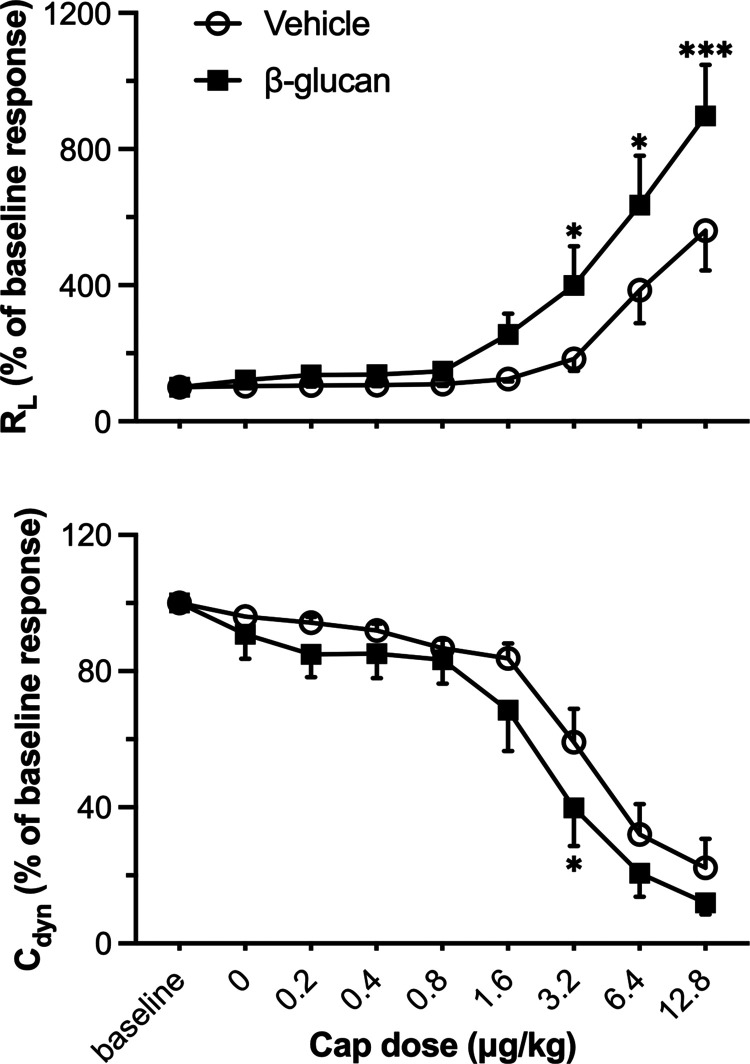

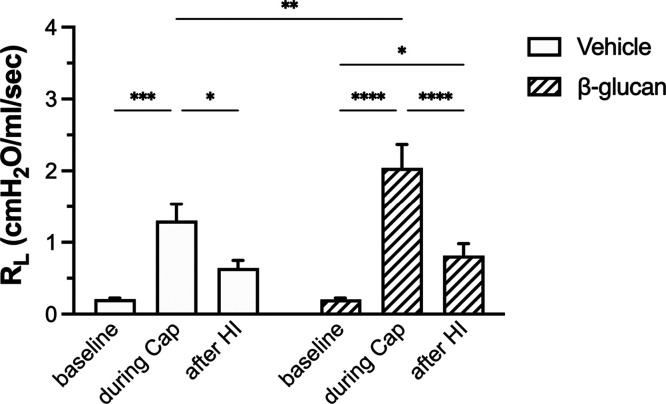

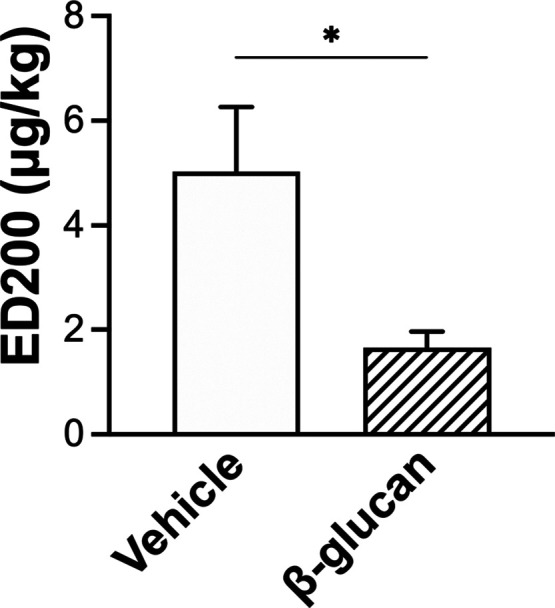

There was no significant difference between the vehicle- and β-glucan-treated guinea pigs in the average baseline of lung mechanics (total pulmonary resistance, RL; dynamic lung compliance, Cdyn; Figure 1) and cardiovascular parameters (arterial blood pressure, ABP; heart rate, HR; Figure 1). However, the bronchoconstrictive responses to capsaicin were significantly increased in β-glucan animals: the capsaicin (3.2 μg/kg) increased RL by 184% in vehicle animals and by 400% in the β-glucan animals (n = 8, P < 0.05; Figures 2 and 3). The airway response to capsaicin challenge was dose-dependent: the bronchoconstrictive responses were increased at a higher dose of capsaicin challenges (Figures 2 and 3). Furthermore, as compared to the responses to the vehicle, the β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness was further evidenced by a large decrease in effective dose 200% (ED200), which is the equivalent dose of capsaicin causing a 200% increase in RL (n = 8, ED200 in the vehicle: 5.0 ± 1.2 μg/kg; in β-glucan: 1.7 ± 0.3 μg/kg; P < 0.05; Figure 4). At the end of the experiment of bronchoconstrictive responses, the application of lung hyperinflation reversed nearly 50% of increased RL in both the vehicle and β-glucan groups (n = 8, vehicle: from 1.3 ± 0.2 to 0.6 ± 0.1 cmH2O/mL/s, P < 0.05; β-glucan: from 2.0 ± 0.3 to 0.8 ± 0.2 cmH2O/mL/s, P < 0.0001; Figure 5). However, the RL induced by capsaicin injection was still significantly larger than the baseline (0.2 ± 0.02 cmH2O/mL/s) after lung hyperinflation (0.8 ± 0.2 cmH2O/mL/s) in β-glucan animals (n = 8, P < 0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Effect of β-glucan exposure on the baseline of airway reactivity and cardiovascular parameters. Baseline data of total pulmonary resistance (RL; cmH2O/mL/s), dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn; mL/cmH2O), arterial blood pressure (ABP; mmHg), and heart rate (HR; beats/min) were calculated as the mean over 10-breath interval before capsaicin injection. Data represent mean ± SEM of 8 guinea pigs in each group. No statistical significance was found between any two groups.

Figure 2.

Experimental record illustrating the responses of transpulmonary pressure (Ptp), respiratory flow (V̇), and ABP to accumulating doses of capsaicin injections (0.8, 1.6, and 3.2 μg/kg were injected intravenously at 2 min intervals, as indicated by arrows). The responses were recorded 24 h after vehicle (upper) or β-glucan (lower) intratracheal instillation in two guinea pigs (vehicle: 380 g body weight; β-glucan: 360 g body weight).

Figure 3.

Dose responses of RL and Cdyn to intravenous injections of capsaicin (Cap) in vehicle and β-glucan-treated guinea pigs. Peak responses to each dose of capsaicin in each guinea pig were averaged over the three consecutive breaths that occurred. ○: responses in vehicle animals; ■: responses in β-glucan-treated animals. Data were mean ± SEM of eight guinea pigs in each group. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, significant difference comparing corresponding data between the vehicle and β-glucan-treated animals.

Figure 4.

Effective dose 200% (ED200) to capsaicin injections 24 h after the vehicle (open bar) or β-glucan (hatched bar) instillation in guinea pigs. ED200 is the dose of the stimulant (capsaicin was chosen in the present study) that produced a doubling of the baseline response of RL. Data were mean ± SEM of eight guinea pigs in each group. *P < 0.05, a significant difference between the vehicle and β-glucan animals.

Figure 5.

Effect of lung hyperinflation (HI) on the RL changes induced by capsaicin (Cap) injection in the vehicle (open bars) and β-glucan (hatched bars) animals. Lung hyperinflation was done by blocking the airflow outlet of the ventilator for two respiratory cycles (3 × VT). Data were mean ± SEM of eight guinea pigs in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

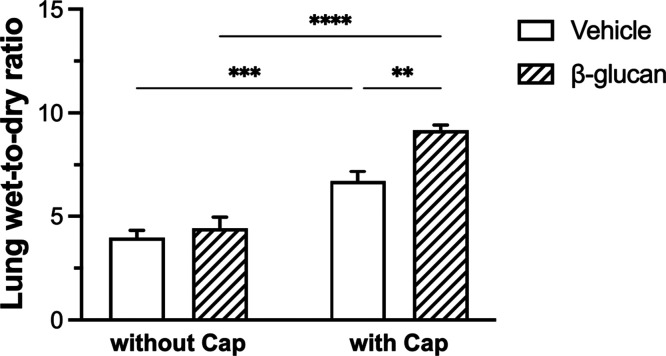

The wet-to-dry ratio of lungs without capsaicin injection in the vehicle and β-glucan groups exhibited no significant difference (n = 8, vehicle: 4.0 ± 0.3; β-glucan: 4.4 ± 0.5; P > 0.05; Figure 6). However, the wet-to-dry ratio of lungs of capsaicin-injected animals was significantly increased in β-glucan groups (9.2 ± 0.3) as compared to that in vehicle groups (6.7 ± 0.5; P < 0.01; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the lung wet-to-dry ratio without or with capsaicin (Cap) injection in the vehicle (open bars) and β-glucan (hatched bars) animals. Data were mean ± SEM of eight guinea pigs in each group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

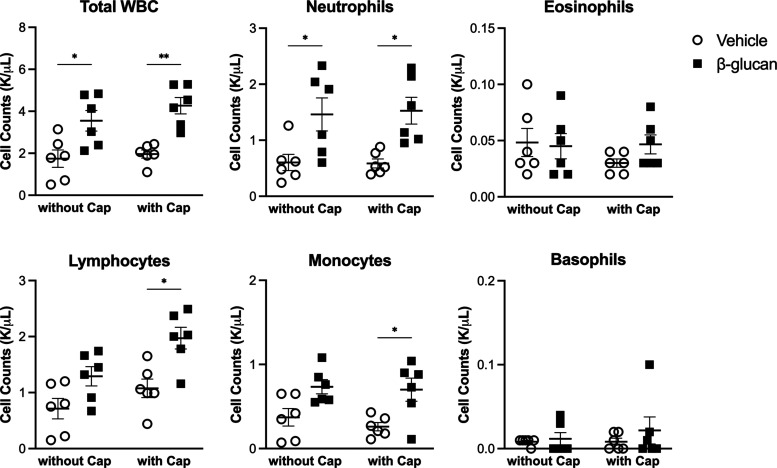

We examined whether β-glucan exerted any systemic effect without capsaicin challenge on the cellular composition in the white blood cells (WBCs) in the blood even when it was instilled into the lungs of guinea pigs. The WBC count (n = 6, vehicle: 1.7 ± 0.4 K/μL; β-glucan: 3.5 ± 0.5 K/μL, P < 0.05; Figure 7) and neutrophils (n = 6, vehicle: 0.6 ± 0.1 K/μL, β-glucan: 1.5 ± 0.3 K/μL, P < 0.05; Figure 7) were higher in β-glucan-treated animals. We also assessed the WBC composition in capsaicin-injected animals with the vehicle or β-glucan treatment. The count of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes was significantly increased in capsaicin-injected animals with β-glucan pretreatment (P < 0.01 in total WBC, P < 0.05 in neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes; Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Systemic impact of intratracheal instillation of the vehicle (round) or β-glucan (square) in the complete blood count. Data were mean ± SEM of six guinea pigs in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

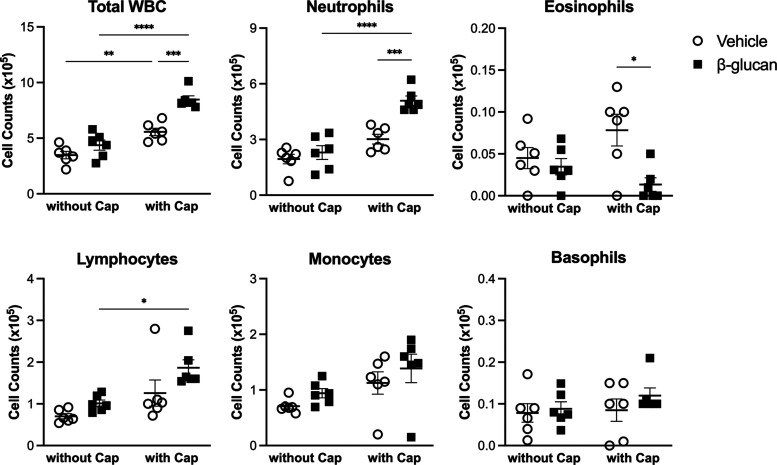

Furthermore, we determined the effect of the instillation of β-glucan on the composition of cell populations present in the lungs. Thus, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was collected from the lungs, and there was no significant difference between the vehicle and β-glucan in the cell compositions. In contrast, β-glucan instillation significantly changed the composition of inflammatory cells that accumulate in the capsaicin-injected group. As a result, the total WBC and the total number of neutrophils were significantly increased (P < 0.001), while the total number of eosinophils (P < 0.05) was decreased in the capsaicin-injected guinea pigs with β-glucan pretreatment (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Effect of the intratracheal instillation of the vehicle (round) or β-glucan (square) in cell numbers in the BALF. Data were mean ± SEM of six guinea pigs in each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

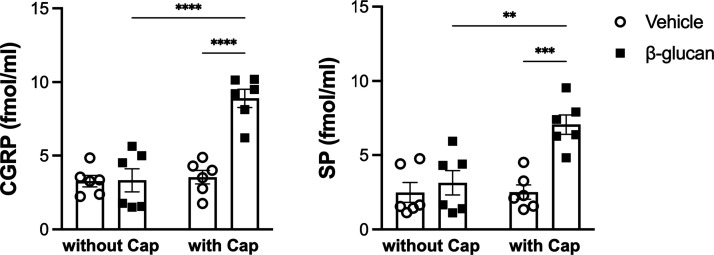

There was no significant difference between the vehicle and β-glucan-treated guinea pigs in the level of the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP). The level of the CGRP was 8.9 ± 0.6 fmol/mL, and that of SP was 7.1 ± 0.7 fmol/mL in the BALF obtained from β-glucan-pretreated guinea pigs after a bolus injection of capsaicin. These levels of tachykinins were significantly higher than those obtained from vehicle guinea pigs after the bolus injection of an identical dose of capsaicin (n = 6, CGRP: 3.5 ± 0.5, P < 0.0001; SP: 2.5 ± 0.5, P < 0.001; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Level of CGRP and substance P (SP) in BALF obtained from the vehicle (round) and β-glucan (square) animals. Data were means ± SEM of six guinea pigs in each group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrated that β-glucan instillation induced airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs without affecting the baseline lung mechanics and cardiovascular parameters (Figure 1). RL to intravenous injection of capsaicin was significantly higher in guinea pigs exposed to β-glucan instillation than in those exposed to the vehicle (Figures 2 and 3). RL and Cdyn were analyzed to compare airway reactivity affected by β-glucan in this present study. RL is affected much more by the central airways than the small ones. Reciprocally, a decrease in Cdyn reflects the elevation of the resistance of small airways. Collectively, β-glucan elevated RL but not Cdyn, suggesting that bronchoconstriction occurred primarily in the large airways.

The mechanisms underlying β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness to capsaicin provocation remain unknown. The pulmonary C-fiber afferents are localized in the endings of the sensory nerves innervating the airways and lungs; neuropeptides can be synthesized and activated in the cell bodies of these afferents by noxious stimuli, and, in turn, trigger potent bronchoconstriction.16,20 Capsaicin, the bronchoconstrictive substance used in the present study, produced the stimulation effect on pulmonary vagal C-fibers and resulted in both neuropeptide release and cholinergic reflex. However, the cholinergic reflex is relatively minor, and the tachykinin mechanism is particularly pronounced in the bronchoconstriction responses in guinea pigs.15,21,22 In addition, β-glucan was reported to activate the dorsal root ganglion neurons and lead to CGRP production;23 β-glucan also induces allodynia, which is the consequence of the hyperreactivity of pain sensation.24 This information is compatible with our present findings that the neuropeptidergic mechanism is important in the β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in guinea pigs (Figure 9).

Our previous study has demonstrated the Dectin-1 immunoreactivity on the TRPV1-positive pulmonary vagal neurons.13 Moreover, β-glucan-induced sensitization of pulmonary vagal sensory neurons and airway hypersensitivity are mediated primarily through the sensitization of pulmonary C-fiber afferents via TRPA1 and dectin-1 receptors.13 However, the role of Dectin-1 in the β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness remains largely unknown and needs to be further explored.

Furthermore, the ED200 of capsaicin is much lower in the β-glucan-treated guinea pigs (Figure 4). This airway hyperresponsiveness does not result from repeated capsaicin challenges because vehicle animals do not show such a hyperreactive response. Moreover, the lung hyperinflation application (3 × VT), which can reopen the constricted airways, reversed nearly 50% of the alteration of RL in both vehicle and β-glucan-treated animals (Figure 5). However, the RL after lung hyperinflation application was still significantly greater than the baseline, suggesting another mechanism than the bronchomotor tone that contributes to the changes in RL, such as lung edema and inflammation. We have shown that lung edema occurs after capsaicin challenge in β-glucan-treated animals (Figure 6). In addition, the wet-to-dry ratio of the lung to capsaicin challenge is significantly higher in β-glucan-treated animals. Indeed, it has been suggested that lung edema may amplify bronchoconstriction by excess fluid into the airway lumen and thickening the airway wall.25,26 In addition, it is well established that lung edema and inflammation are observed in patients with airway hyperreactive diseases such as asthma.26,27 On the other hand, airway mucosal inflammation is an obvious feature of airway hyperreactivity.7,28,29 In addition, the sensitivity of pulmonary C-fibers can be augmented by airway mucosal inflammation or airway mucosal injury;30,31 the neuropeptide release can be enhanced upon C-fiber sensitization, in turn inducing more potent airway responses.29−31 The role of pulmonary C-fiber sensitization in β-glucan-generated airway responses is supported by our previous observation that β-glucan instillation enhances the excitability of pulmonary C-fibers and isolated C-neurons to capsaicin.13 Here, we further prove the downstream complications and airway hyperresponsiveness development.

The β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness was associated with lung inflammation, as exemplified by the marked increase in the BALF levels of inflammatory cell infiltration (Figure 8). Here, we demonstrated a significant increase in the cell number of neutrophils and a decrease in that of eosinophils in BALF after capsaicin challenge in β-glucan-treated animals (Figure 8). However, in contrast, β-glucan is shown to develop more profound pulmonary inflammation and exacerbate allergic airway responses to house dust mites in rodents.4 Furthermore, a higher number of eosinophils when β-glucan plus house dust mite challenge and a slight increase in neutrophils and monocytes have been demonstrated.4 Moreover, we also observed that the cell number of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes was increased in blood after the capsaicin challenge in β-glucan-treated animals compared to vehicle animals (Figure 7). These data suggested that compared to vehicle instillation, β-glucan instillation may reduce eosinophil influx into the lungs after the capsaicin challenge. Indeed, previous studies have shown that neutrophils are the first cell type to enter the lungs, following allergen exposure.32−34 In addition, neutrophils dominated more often than eosinophils in the sputum35 and the BALF36 of patients with acute asthma exacerbations, with33,35 or without36 respiratory tract infections. Together, with these data, it appears that β-glucan is specific in targeting and resulting neutrophilia in the model of this present study.

Furthermore, it has been indicated that insults inhaled into the lungs such as ozone37 and cigarette smoke38,39 can inhibit the activity of airway neuropeptidase, the main enzyme for neuropeptide degradation. Neuropeptidase activity reduction followed by insult exposure might amplify the neuropeptidergic effects and develop airway hyperresponsiveness. However, the involvement of neuropeptidase in the β-glucan-induced airway hyperresponsiveness needs further investigations.

In summary, our present study shows that airway exposure to β-glucan that induces airway hyperresponsiveness to the capsaicin challenge is associated with neutrophilic inflammation. Furthermore, this airway hyperresponsiveness is potentially mediated through neuropeptide release from the nerve endings of pulmonary C-fiber afferents. Results obtained from this study may provide new insight into the pathogenic mechanisms of fungi-associated airway hyperresponsiveness and potential therapy.

Methods

Study Approval

The procedures described below were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, published by the United States National Institute of Health, and were also approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Taipei Medical University (2015-0411).

Animal Preparation

Male guinea pigs are initially anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of α-chloralose (100 mg/kg) and urethane (500 mg/kg). Next, a short cannula is inserted via tracheostomy. The right femoral artery was cannulated for measuring ABP. The right jugular vein was cannulated for the administration of anesthetics and pharmacological agents. Body temperature was maintained at ∼36 °C throughout the experiments using a heating pad placed under the rat lying in a supine position.

β-glucan Instillation Treatment

Twenty-four hours prior to studying the bronchoconstrictive responses, the wet-to-dry ratio of the lung, blood and BALF analysis, male guinea pigs (350–450 g) were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Zoletil and Rompum. Solutions of β-glucan (5 mg in 0.1 mL; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or the vehicle (sterile isotonic saline) were instilled into the trachea.

Measurement of Bronchoconstrictive Responses

Animals were ventilated mechanically (Harvard model 683, South Natick, MA). A catheter for measuring the intrapleural pressure was inserted into the right intrapleural cavity. Transpulmonary pressure was measured as the difference between the tracheal and intrapleural pressure. Airway flow was measured and integrated to give the tidal volume. All signals were recorded continuously, and an on-line computer analysis (Biocybernetics TS-100, Taipei, Taiwan) was performed to calculate two of the indexes of bronchoconstrictive responses: RL and Cdyn. Results from the computer were routinely checked for accuracy by hand calculation. The dose–response curves of the bronchoconstrictive response induced by capsaicin were generated by the intravenous injection of capsaicin at 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, 3.2, 6.4, and 12.8 μg/kg, at 2 min intervals.

Measurement of the Wet-to-Dry Ratio of the Lung

The lung wet-to-dry ratio was used as an index of lung water accumulation in lung edema. The lung weight was measured immediately (wet weight) after the animals were dissected under anesthesia; then, the lung tissue was dried in an oven at 65 °C for 3 days and weighed again (dry weight).

Measurement of the Cell Composition in Blood

Blood samples were taken 24 h after the vehicle or β-glucan pretreatment. In both groups of vehicle and β-glucan, the cell composition of blood was measured without or with an injection of capsaicin (12.8 μg/kg) using a hematology analyzer (ProCyte Dx, IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, MA), following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Inflammatory Cell and Neuropeptide Analysis in BALF

The BALF samples were taken 24 h after the vehicle or β-glucan pretreatment. In both groups of the vehicle and β-glucan, BALF was obtained by injecting 6 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (3 mL, twice) via the tracheal cannula without or with an injection of capsaicin (12.8 μg/kg). The collected BALF (∼5 mL) was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The levels of SP and CGRP were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI).

Experimental Design and Protocols

A total of 72 guinea pigs were studied in four series of experiments. Study series 1: the dose–response curves of RL and Cdyn to bolus injections of capsaicin (0–12.8 μg/kg) were determined in each animal by gradually increasing the dose of capsaicin at 2 min intervals. These dose responses were then compared between the vehicle and β-glucan groups to verify the airway hyperresponsiveness. At the end of the experiment of bronchoconstrictive responses, lung hyperinflation was applied to verify the active involvement of the bronchomotor tone (n = 16; n = 8 for each group). Study series 2: to assess the lung edema, the lung wet-to-dry ratios were compared in both the vehicle and β-glucan groups, with or without capsaicin injection (n = 32; n = 8 for each group). Study series 3: to investigate the systemic inflammatory response, the WBC in blood was measured in both vehicle and β-glucan groups, without or with capsaicin injection (n = 24; n = 6 for each group). Study series 4: to assess airway inflammation and the tachykinins release, the inflammatory cell number and neuropeptides from BALF were measured in both vehicle and β-glucan groups (n = 24; n = 6 for each group, the same animals in study series 3).

Data Analysis

These parameters were analyzed using a computer equipped with an analog-to-digital converter and software (GraphPad Prism 9.1, San Diego, CA). Data were analyzed using the t test or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A P value <0.05 is considered significant. Data are mean ± SEM.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sheng-Hsuan Lan, I-Hsuan Huang, and Tzu-Chun Lin for their valuable technical assistance.

Author Contributions

# Y.-Y.C. and N.-J.C. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

This study was supported in part by the MOST grants 105-2320-B-038-055-MY2 (to Y.S.L.) and 108-2320-B-038-059-MY3 (to C.-C.H.), and in part by the MOE grant DP2-110-21121-01-T-02-03 (to C.-C.H.) from Taiwan.

References

- Young R. S.; Jones A. M.; Nicholls P. J. Something in the Air: Endotoxins and Glucans as Environmental Troublemakers. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1998, 50, 11–17. 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb03299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G. D.; Gordon S. Fungal Beta-Glucans and Mammalian Immunity. Immunity 2003, 19, 311–315. 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00233-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beijer L.; Thorn J.; Rylander R. Mould Exposure at Home Relates to Inflammatory Markers in Blood. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 21, 317–322. 10.1183/09031936.03.00283603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadebe S.; Kirstein F.; Fierens K.; Redelinghuys P.; Murray G. I.; Williams D. L.; Lambrecht B. N.; Brombacher F.; Brown G. D. β-Glucan Exacerbates Allergic Airway Responses to House Dust Mite Allergen. Respir. Res. 2016, 17, 35. 10.1186/s12931-016-0352-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-A.; Lee M.-Y.; Seo C.-S.; Jung D. Y.; Lee N.-H.; Kim J.-H.; Ha H.; Shin H. K. Anti-Asthmatic Effects of an Amomum Compactum Extract on an Ovalbumin (OVA)-Induced Murine Asthma Model. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2010, 74, 1814–1818. 10.1271/bbb.100177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh M.; Zhang T.; Seljelid R.; Li X. Streptomyces Cerevisiae 1,3/1,6 Beta-Glucan Prevents Airway Hyperreactivity and Pulmonary Inflammation in a Murine Asthma Model. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, S6. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cockcroft D. W.; Davis B. E. Mechanisms of Airway Hyperresponsiveness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 118, 551–559. 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreave F. E.; Dolovich J.; O’Byrne P. M.; Ramsdale E. H.; Daniel E. E. The Origin of Airway Hyperresponsiveness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1986, 78, 825–832. 10.1016/0091-6749(86)90226-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. J. New Concepts in the Pathogenesis of Bronchial Hyperresponsiveness and Asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1989, 83, 1013–1026. 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90441-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitinen L. A.; Laitinen A.. The Pathology of Asthma: An Overview. In Pharmacology of Asthma; Page C. P., Barnes P. J., Eds.; Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 1991; pp 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. X.; Zhou D.; Chen G.; Lee L. Y. Airway Hyperresponsiveness to Cigarette Smoke in Ovalbumin-Sensitized Guinea Pigs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000, 161, 73–80. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9809121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory L. G.; Mathie S. A.; Walker S. A.; Pegorier S.; Jones C. P.; Lloyd C. M. Overexpression of Smad2 Drives House Dust Mite-Mediated Airway Remodeling and Airway Hyperresponsiveness via Activin and IL-25. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2010, 182, 143–154. 10.1164/rccm.200905-0725OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. S.; Huang I.-H.; Lan S.-H.; Chen C.-L.; Chen Y.-Y.; Chan N.-J.; Hsu C.-C. Involvement of Capsaicin-Sensitive Lung Vagal Neurons and TRPA1 Receptors in Airway Hypersensitivity Induced by 1,3-β-D-Glucan in Anesthetized Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6845. 10.3390/ijms21186845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleridge J. C.; Coleridge H. M. Afferent Vagal C Fibre Innervation of the Lungs and Airways and Its Functional Significance. Rev. Physiol. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1984, 99, 1–110. 10.1007/BFb0027715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J. M.; Saria A. Polypeptide-Containing Neurons in Airway Smooth Muscle. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 1987, 49, 557–572. 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway J.; Leff A. R. Sensory Neuropeptides and Airway Function. J. Appl. Physiol. 1991, 71, 2077–2087. 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem B. J.; Weinreich D. Electrophysiological Properties and Chemosensitivity of Guinea Pig Nodose Ganglion Neurons in Vitro. J. Auton. Nerv. Syst. 1993, 44, 17–33. 10.1016/0165-1838(93)90375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solway J.; Kao B. M.; Jordan J. E.; Gitter B.; Rodger I. W.; Howbert J. J.; Alger L. E.; Necheles J.; Leff A. R.; Garland A. Tachykinin Receptor Antagonists Inhibit Hyperpnea-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Guinea Pigs. J. Clin. Invest. 1993, 92, 315–323. 10.1172/JCI116569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray D. W.; Hernandez C.; Leff A. R.; Drazen J. M.; Solway J. Tachykinins Mediate Bronchoconstriction Elicited by Isocapnic Hyperpnea in Guinea Pigs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1989, 66, 1108–1112. 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.3.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg J. M.; Hökfelt T.; Martling C. R.; Saria A.; Cuello C. Substance P-Immunoreactive Sensory Nerves in the Lower Respiratory Tract of Various Mammals Including Man. Cell Tissue Res. 1984, 235, 251–261. 10.1007/BF00217848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajj A. M.; Burki N. K.; Lee L. Y. Role of Tachykinins in Sulfur Dioxide-Induced Bronchoconstriction in Anesthetized Guinea Pigs. J. Appl. Physiol. 1996, 80, 2044–2050. 10.1152/jappl.1996.80.6.2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L. Y.; Lou Y. P.; Hong J. L.; Lundberg J. M. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Bronchoconstriction and Release of Tachykinins in Guinea Pig Lungs. Respir. Physiol. 1995, 99, 173–181. 10.1016/0034-5687(94)00088-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K.; Takayama Y.; Kondo T.; Ishibashi K.-I.; Sahoo B. R.; Kanemaru H.; Kumagai Y.; Martino M. M.; Tanaka H.; Ohno N.; Iwakura Y.; Takemura N.; Tominaga M.; Akira S. Nociceptors Boost the Resolution of Fungal Osteoinflammation via the TRP Channel-CGRP-Jdp2 Axis. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 2730–2742. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K.; Takayama Y.; Sugisawa E.; Yamanoi Y.; Yokawa T.; Kondo T.; Ishibashi K.-I.; Sahoo B. R.; Takemura N.; Mori Y.; Kanemaru H.; Kumagai Y.; Martino M. M.; Yoshioka Y.; Nishijo H.; Tanaka H.; Sasaki A.; Ohno N.; Iwakura Y.; Moriyama Y.; Nomura M.; Akira S.; Tominaga M. The ATP Transporter VNUT Mediates Induction of Dectin-1-Triggered Candida Nociception. iScience 2018, 6, 306–318. 10.1016/j.isci.2018.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatawadekar S. A.; Inman M. D.; Fredberg J. J.; Tarlo S. M.; Lyons O. D.; Keller G.; Yadollahi A. Contribution of Rostral Fluid Shift to Intrathoracic Airway Narrowing in Asthma. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 122, 809–816. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00969.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager D.; Kamm R. D.; Drazen J. M. Airway Wall Liquid: Sources and Role as an Amplifier of Bronchoconstriction. Chest 1995, 107, 105S–110S. 10.1378/chest.107.3_Supplement.105S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager D.; Shore S.; Drazen J. M. Airway Luminal Liquid: Sources and Role as an Amplifier of Bronchoconstriction. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1991, 143, S52. 10.1164/ajrccm/143.3_Pt_2.S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djukanović R.; Roche W. R.; Wilson J. W.; Beasley C. R.; Twentyman O. P.; Howarth R. H.; Holgate S. T. Mucosal Inflammation in Asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1990, 142, 434–457. 10.1164/ajrccm/142.2.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes P. J. Neural Control of Human Airways in Health and Disease. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1986, 134, 1289–1314. 10.1164/arrd.1986.134.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undem B. J.; Sun H. Molecular/Ionic Basis of Vagal Bronchopulmonary C-Fiber Activation by Inflammatory Mediators. Physiology 2020, 35, 57–68. 10.1152/physiol.00014.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee L.-Y. Respiratory Sensations Evoked by Activation of Bronchopulmonary C-Fibers. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2009, 167, 26–35. 10.1016/j.resp.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. R.; Larsen G. L.; Cherniack R. M.; Wenzel S. E.; Voelkel N. F.; Westcott J. Y.; Bethel R. A. Inflammatory Cells and Eicosanoid Mediators in Subjects with Late Asthmatic Responses and Increases in Airway Responsiveness. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992, 89, 1076–1084. 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson A. P. The Role of Eosinophils and Neutrophils in Inflammation. Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2000, 30, 22–27. 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teran L. M.; Carroll M.; Frew A. J.; Montefort S.; Lau L. C. K.; Davies D. E.; Lindley I.; Howarth P. H.; Church M. K.; Holgate S. T. Neutrophil Influx and Lnterleukin-8 Release after Segmental Allergen or Saline Challenge in Asthmatics. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 1995, 107, 374–375. 10.1159/000237040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahy J. V.; Kim K. W.; Liu J.; Boushey H. A. Prominent Neutrophilic Inflammation in Sputum from Subjects with Asthma Exacerbation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1995, 95, 843–852. 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamblin C.; Gosset P.; Tillie-Leblond I.; Saulnier F.; Marquette C.-H.; Wallaert B.; Tonnel A. B. Bronchial Neutrophilia in Patients with Noninfectious Status Asthmaticus. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998, 157, 394–402. 10.1164/ajrccm.157.2.97-02099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murlas C. G.; Lang Z.; Williams G. J.; Chodimella V. Aerosolized Neutral Endopeptidase Reverses Ozone-Induced Airway Hyperreactivity to Substance P. J. Appl. Physiol. 1992, 72, 1133–1141. 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.3.1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusser D. J.; Djokic T. D.; Borson D. B.; Nadel J. A. Cigarette Smoke Induces Bronchoconstrictor Hyperresponsiveness to Substance P and Inactivates Airway Neutral Endopeptidase in the Guinea Pig. Possible Role of Free Radicals. J. Clin. Invest. 1989, 84, 900–906. 10.1172/JCI114251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo H. P.; Lu L. C. Sensory Neuropeptides Modulate Cigarette Smoke-Induced Decrease in Neutral Endopeptidase Activity in Guinea Pig Airways. Life Sci. 1995, 57, 2187–2196. 10.1016/0024-3205(95)02210-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]