Abstract

Background

Gynaecological cancers account for 15% of newly diagnosed cancer cases in women worldwide. In recent years, increasing evidence demonstrates that traditional approaches in perioperative care practice may be unnecessary or even harmful. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme has therefore been gradually introduced to replace traditional approaches in perioperative care. There is an emerging body of evidence outside of gynaecological cancer which has identified that perioperative ERAS programmes decrease length of postoperative hospital stay and reduce medical expenditure without increasing complication rates, mortality, and readmission rates. However, evidence‐based decisions on perioperative care practice for major surgery in gynaecological cancer are limited. This is an updated version of the original Cochrane Review published in Issue 3, 2015.

Objectives

To evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of perioperative enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programmes in gynaecological cancer care on length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications, mortality, readmission, bowel functions, quality of life, participant satisfaction, and economic outcomes.

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases for the literature published from inception until October 2020: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed, AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Scopus, and four Chinese databases including the China Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), WanFang Data, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Weipu Database. We also searched four trial registration platforms and grey literature databases for ongoing and unpublished trials, and handsearched the reference lists of included trials and accessible reviews for relevant references.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared ERAS programmes for perioperative care in women with gynaecological cancer to traditional care strategies.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently screened studies for inclusion, extracted the data and assessed methodological quality for each included study using the Cochrane risk of bias tool 2 (RoB 2) for RCTs. Using Review Manager 5.4, we pooled the data and calculated the measures of treatment effect with the mean difference (MD), standardised mean difference (SMD), and risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) to reflect the summary estimates and uncertainty.

Main results

We included seven RCTs with 747 participants. All studies compared ERAS programmes with traditional care strategies for women with gynaecological cancer. We had substantial concerns regarding the methodological quality of the included studies since the included RCTs had moderate to high risk of bias in domains including randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, and measurement of outcomes.

ERAS programmes may reduce length of postoperative hospital stay (MD ‐1.71 days, 95% CI ‐2.59 to ‐0.84; I2 = 86%; 6 studies, 638 participants; low‐certainty evidence). ERAS programmes may result in no difference in overall complication rates (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.05; I2 = 42%; 5 studies, 537 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The certainty of evidence was very low regarding the effect of ERAS programmes on all‐cause mortality within 30 days of discharge (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.68; 1 study, 99 participants). ERAS programmes may reduce readmission rates within 30 days of operation (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.90; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 385 participants; low‐certainty evidence). ERAS programmes may reduce the time to first flatus (MD ‐0.82 days, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.63; I2 = 35%; 4 studies, 432 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and the time to first defaecation (MD ‐0.96 days, 95% CI ‐1.47 to ‐0.44; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 228 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The studies did not report the effects of ERAS programmes on quality of life. The evidence on the effects of ERAS programmes on participant satisfaction was very uncertain due to the limited number of studies. The adoption of ERAS strategies may not increase medical expenditure, though the evidence was of very low certainty (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.25; I2 = 54%; 2 studies, 167 participants).

Authors' conclusions

Low‐certainty evidence suggests that ERAS programmes may shorten length of postoperative hospital stay, reduce readmissions, and facilitate postoperative bowel function recovery without compromising participant safety. Further well‐conducted studies are required in order to validate the certainty of these findings.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Length of Stay, Neoplasms, Perioperative Care, Postoperative Complications, Postoperative Complications/epidemiology, Postoperative Complications/prevention & control, Quality of Life

Plain language summary

Perioperative enhanced recovery after surgery programmes for women with gynaecological cancers

Background Gynaecological cancers lead to a significant amount of morbidity and mortality. Surgery, either by laparoscopic (key‐hole surgery) or open surgical techniques, is one of the most important approaches in the treatment of gynaecological cancer. Well‐planned perioperative care (care at or around the time of surgery) is vital for recovery following surgery.

In recent years, researchers and doctors have suggested that many aspects of traditional perioperative care practice may be unnecessary or even harmful. For example, the use of oral laxative and enema could result in preoperative abnormalities in the levels of sodium, potassium or calcium, along with dehydration. The enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme aims to reduce surgical stress and avoid harmful aspects of traditional perioperative care. It has been introduced gradually to various surgical fields, particularly bowel surgery. ERAS programmes may help recovery after surgery, shorten time in hospital, and save hospital costs without putting the person at greater risk. However, less is known about the effects of ERAS programmes in women with gynaecological cancer. This review aims to evaluate the benefits and harms of perioperative ERAS programmes in gynaecological cancer care.

Study characteristics

We searched both Chinese and English databases (up to October 2020) and found seven trials of 747 women with gynaecological cancer, including cervical cancer, uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer. Five studies only recruited women with suspected or confirmed gynaecological cancer and two studies also included a small group of women with a benign or borderline tumour. Three studies recruited women who underwent laparotomy (where a surgeon makes one large incision in the abdomen) and two studies included those who underwent laparoscopic surgery (a minimally invasive procedure that requires only small incisions). Two of the studies used both types of surgery. Women then received either perioperative ERAS programmes or traditional care.

Key results

ERAS programmes may reduce time in hospital after the operation and readmission rates within 30 days of surgery. ERAS programmes may speed up recovery of bowel functions following surgery, measured by time to when the woman first breaks wind or opens her bowels. There may be no increase in complications within 30 days of operation using ERAS programmes. Due to limited evidence, we are very uncertain about the effects of ERAS programmes on death from any cause within 30 days of operation, or on how satisfied women were with their care. We did not find any evidence about their quality of life. ERAS might not increase hospital costs, but the evidence was very uncertain.

Conclusions

ERAS programmes may shorten time in hospital after the operation, reduce postoperative readmission rates, and facilitate bowel function recovery without compromising the safety of women with gynaecological cancer, although we have limited confidence in the findings due to the quality of the studies. Future well‐conducted studies may increase the certainty of these findings.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Enhanced recovery after surgery programme compared to traditional care for women with gynaecological cancers.

| Enhanced recovery after surgery programme compared to traditional care for women with gynaecological cancers | ||||||

| Patient or population: women with gynaecological cancers Setting: hospital‐based gynaecological cancer perioperative care Intervention: enhanced recovery after surgery programme Comparison: traditional care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What this means | |

| Risk with traditional care | Risk with enhanced recovery after surgery programme | |||||

| Length of postoperative hospital stay | The mean length of postoperative hospital stay was 7.87 days | MD ‐1.71 days (‐2.59 to ‐0.84) | ‐ | 638 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low a,b | Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes might result in a reduction in length of postoperative hospital stay. |

| Overall postoperative complications (within 30 days of operation) | Study population | RR 0.71 (0.48 to 1.05) | 537 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low c,d | Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes might result in no difference in overall complications within 30 days of operation. | |

| 333 per 1000 | 237 per 1000 (160 to 350) | |||||

| Mortality (within 30 days of discharge) | Study population | RR 0.98 (0.14 to 6.68) | 99 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very lowd,e | The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of the enhanced recovery after surgery programme on all‐cause mortality within 30 days of discharge . | |

| 41 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (6 to 273) | |||||

| Readmission (within 30 days of operation) | Study population | RR 0.45 (0.22 to 0.90) | 385 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low b,d | Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes might reduce readmission within 30 days of operation. | |

| 126 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (28 to 114) | |||||

| Time to first flatus (bowel function) | The mean time to first flatus (bowel function) was 1.80 days | MD ‐0.82 days (‐1.00 to ‐0.63) | ‐ | 432 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low d,f | Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes might result in reduction in time to first flatus. |

| Time to first defaecation (bowel function) | The mean time to first defaecation (bowel function) was 3.97 days | MD ‐0.96 days (‐1.47 to ‐0.44) | ‐ | 228 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low d,g | Enhanced recovery after surgery programmes might reduce time to first defaecation. |

| Participant satisfaction | ‐ | SMD 0.92 (0.06 to 1.78) | ‐ | 228 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b,c,d | The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of enhanced recovery after surgery programmes on participant satisfaction. |

| Economic outcomes | ‐ | SMD ‐0.22 (‐0.68 to 0.25) | ‐ | 167 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low b,c,d | The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of enhanced recovery after surgery programmes on hospital costs. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited. The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate. The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aInconsistency downgraded one level because the proportion of the variability in effect estimates that is due to true heterogeneity is considerable. bRisk of bias downgraded one level because of suspected deviations from intended interventions or high risk of confounding bias and information bias. cImprecision downgraded one level due to inclusion of appreciable benefit and no effect. dPublication bias downgraded because data were reported by a limited number of studies. eImprecision downgraded two levels as CI of pooled estimate includes substantial benefit, substantial harm and no effect. fInconsistency downgraded one level as one study that could not be included in the pooled analysis reported that no significant difference was found regarding the distribution of the time to first flatus between groups. gIndirectness downgraded one level due to one of the two RCTs including participants with both benign and malignant tumours. Pooled results changed when excluding this study.

Background

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane Review (Lu 2015).

Description of the condition

Gynaecological cancers consist of cancers of the cervix uteri, corpus uteri, ovary, vulva, and vagina, and the five‐year gynaecological cancer prevalence rate is > 7.7% worldwide (WHO 2021). There were over 1.39 million new cases of gynaecological cancers in 2020, accounting for 15.2% of all new cancer cases in women. About 15% of women with cancer died of gynaecological cancers in 2020, of which ovarian cancer was found to be associated with a worse prognosis compared to other gynaecological cancers (Ledford 2019; WHO 2021). Cervical cancer is the most prevalent type of gynaecological cancer, making up 6.5% of new cases every year. It has become the fourth most common cancer in women, following breast, colorectal, and lung cancer (Arbyn 2020; WHO 2021). The age‐standardised incidence and mortality rates of cervical cancer are 13.3 and 7.3 per 100,000 persons worldwide, respectively (Arbyn 2020; WHO 2021).

Surgery, either by laparoscopic or open surgical techniques, is one of the most important approaches in the treatment of gynaecological cancers (Zalewski 2018). Other treatments include chemotherapy and radiotherapy, along with other multimodal therapies. Perioperative care, which is influenced by specific care strategies, impacts recovery following surgery. Traditional perioperative care may consist of preoperative overnight fasting and mechanical bowel preparation, intravenous fluids prior to surgery or anaesthesia, receiving pelvic drains during operation, receiving nasogastric tubes, and beginning a graduated oral intake until bowel sounds return after surgery. However, more evidence‐based results have shown that many of these traditional perioperative approaches are unnecessary or may even be harmful.

For example, with people who underwent colorectal surgery, the use of mechanical bowel preparation was not associated with a lower risk of mortality, wound infection, anastomotic leak, or reoperation as compared to those who had no mechanical bowel preparation (Cao 2012; Dahabreh 2015). Moreover, the use of mechanical bowel preparation may lead to adverse events due to preoperative dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, so impede the recovery process (Arnold 2015). Preoperative overnight fasting may also be problematic because it may cause postoperative complications such as insulin resistance (ASAC 2017). A Cochrane Review assessing the effects of preoperative carbohydrate treatment has shown that the treatment was associated with less postoperative insulin resistance, faster bowel function recovery, and shorter length of hospital stay, without compromising safety in adult participants who underwent abdominal, orthopaedic, and cardiac surgeries (Smith 2014).

With increasing concerns regarding postoperative recovery and comfort, and the development of enhanced recovery strategies, it is imperative to re‐examine the necessity and appropriateness of traditional approaches and to establish if current practice is supported by clinical evidence in the perioperative care of women with gynaecological cancers.

Description of the intervention

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS), also known as Enhanced Recovery Programme (ERP), or fast track (FT) surgery, was first incorporated in colorectal surgeries in the 1990s (Kehlet 2008). ERAS refers to a multidisciplinary, multimodal approach to minimise the physiologic deviations induced by surgery, and to avoid traditional aspects of perioperative care that have documented harm (Kehlet 1997; Ljungqvist 2017). The implementation of ERAS usually requires co‐operation and co‐ordination among surgeons, anaesthetists, an ERAS co‐ordinator (often a nurse or a physician assistant), and staff from units that care for people undergoing surgery, based on the consensus on their ERAS protocols (Ljungqvist 2017).

With continued development in the past two decades, ERAS has been widely accepted and adopted in colorectal, gastric, lung, liver, pancreatic, urological, head and neck surgeries (Li S 2017; Li Z 2017; Rouxel 2019; Spanjersberg 2011; Watson 2020). Specialists also developed ERAS guidelines for different types of diseases or surgeries by synthesising direct evidence in their areas, indirect evidence related to their areas, and expert opinions (Ljungqvist 2017; Melloul 2020). The components of different ERAS programmes vary in different settings but usually address preoperative patient assessment and counselling, avoidance of premedication, fasting and bowel preparation, appropriate use of drains and catheters, hypothermia prevention, multimodal analgesia, postoperative early oral intake, and early mobilisation (Nicholson 2014).

Recently, the ERAS® Society published updated ERAS guidelines on gynaecological oncology care and stated the latest consensus recommendations for ERAS practice (Nelson 2019). They listed a total of 21 domains, including preadmission information, education, counselling, preoperative optimisation, prehabilitation, preoperative bowel preparation, urinary drainage management, and early mobilisation. However, a recent international study showed that although 80% of the participants agreed that ERAS pathways could improve outcomes for people undergoing surgery, only 37% of them reported that ERAS was implemented at their institutions, with a range from 10% in participants from Africa to 38% in participants from Europe (Bhandoria 2020). It is obvious that, in many instances, high quality data were unavailable, and the recommendation was formed based on evidence from other surgical disciplines where abdominal surgeries are routinely performed (Nelson 2019). Furthermore, best ERAS evidence‐based practices for people with different characteristics (e.g. different types of gynaecological cancers) or undergoing different kinds of surgeries (e.g. laparotomy and laparoscopic surgery) are still unclear.

How the intervention might work

A growing body of evidence outside of gynaecological cancers, especially in colorectal cancers, has indicated that ERAS facilitates recovery by minimising physiologic stress after surgery and decreasing length of hospital stay and costs without increasing adverse outcomes. Shorter time to first flatus and defaecation, and earlier acceptance of a solid diet were observed in people with colorectal cancer from ERAS groups when compared with those in traditional care groups in previous randomised controlled trials (Ni 2019; Spanjersberg 2011). People receiving ERAS programmes also performed better on postoperative early mobilisation (Liu 2020; Spanjersberg 2011).

People who underwent colorectal cancer surgeries and received an ERAS intervention usually had shorter postoperative hospital stays as compared to people who received traditional care (Li J 2019; Ljungqvist 2017; Ni 2019; Spanjersberg 2011). Due to the reduction in length of hospital stay and postoperative complications, people receiving ERAS programmes had lower hospitalisation costs compared with those receiving traditional care (Baimas‐George 2020; Li J 2019). Additionally, ERAS implementation is not associated with increased postoperative complication rates and may even be associated with decreased complication rates and severity as compliance with ERAS programmes increases (Li J 2019; Ljungqvist 2017; Ni 2019; Pisarska 2016; Spanjersberg 2011). As such, ERAS implementation is not related to higher readmission rates or mortality (Baimas‐George 2020; Lohsiriwat 2019; Rouxel 2019). From the perspectives of people undergoing different kinds of surgeries, ERAS protocols did not negatively impact quality of life (Leon Arellano 2020; Wu 2019). Participant satisfaction with ERAS programmes was also generally high across different studies (Debono 2019; Liu 2020).

Though the effects of ERAS implementation on long‐term outcomes are unclear at present due to a lack of evidence, a recent study reported that ERAS programmes may facilitate long‐term survival of people with colorectal cancer, as the implementation of ERAS was associated with receiving on‐time adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery (Hassinger 2019).

Why it is important to do this review

Implementation of perioperative ERAS programmes in people with colorectal, gastric, lung, liver, and pancreatic cancer has been examined and supported by several systematic reviews and trials (Li S 2017; Li Z 2017; Rouxel 2019; Spanjersberg 2011; Watson 2020). The main components of ERAS practice for women with gynaecological cancer are mainly extended from other diseases such as colorectal oncology (Nelson 2019), and evidence‐based decisions on major surgery for gynaecological cancers remain limited. Women with gynaecological cancers may have to deal with various challenges, including concerns about physical well‐being (e.g. menopausal symptoms, bowel and urinary complications, lymphoedema, and pelvic pain) and cancer‐related psychosocial issues, such as perceptions of having an altered body image, compared with people from other cancer groups (Ringwald 2017; Sekse 2019). Therefore, we deem it important to assess the benefits and harms of ERAS programmes for women with gynaecological cancer, and to develop tailored pathways for managing the care of women with gynaecological cancer.

Objectives

To evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of perioperative enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programmes in gynaecological cancer care on length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications, mortality, readmission, bowel functions, quality of life, participant satisfaction, and economic outcomes.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and cluster‐RCTs that assessed the effects of ERAS programmes for women with gynaecological cancer. Although there has been a wealth of evidence from non‐RCTs (e.g. before‐after design trials) on the topic, we only focused on RCTs because randomisation prevents systematic differences (confounders) between baseline characteristics of participants in different intervention groups, and claims about cause and effect based on the findings can be made with greater confidence than those from non‐RCTs.

Types of participants

We included women aged ≥18 years old with indications for non‐emergency surgical treatment of gynaecological cancers. Gynaecological cancers consist of cervical, uterine, ovarian, fallopian, vulval, vaginal, and endometrial cancers. Studies including both laparoscopic and open surgical techniques were eligible for inclusion.

Some studies include all women with gynaecological tumours, regardless of whether the tumour is benign or malignant. To avoid the loss of data if such studies were excluded, we also included studies in which the majority (>50%) of the women were diagnosed with gynaecological cancers and the others were diagnosed with benign gynaecological tumours. This meant that we would include some women with benign tumours who did not meet the eligibility criteria, so we used sensitivity analysis to assess the impact of this decision on the review's findings (see Sensitivity analysis).

Types of interventions

We compared any ERAS programmes with traditional recovery strategies in perioperative care for women with gynaecological cancer. The ERAS® Society published the latest consensus reviews of ERAS practice for gynaecological oncology in their updated guidelines (Nelson 2019). A total of 21 domains with recommendations were listed, including 17 domains related to ERAS pre‐, intra‐, and postoperative practices and four related to ERAS management.

Perioperative ERAS practices consist of preadmission information, education, and counselling; preoperative optimisation; prehabilitation; preoperative bowel preparation; preoperative fasting and carbohydrate treatment; pre‐anaesthetic medication; venous thromboembolism prophylaxis; surgical site infection reduction bundles (including antimicrobial prophylaxis, skin preparation, prevention of hypothermia, avoidance of drains/tubes, and control of perioperative hyperglycaemia); standard anaesthetic protocol; nausea and vomiting prophylaxis; minimally invasive surgery; perioperative fluid management/goal‐directed fluid therapy; perioperative nutrition; prevention of postoperative ileus; opioid sparing multimodal postoperative analgesia; urinary drainage management; and early mobilisation. The other four domains related to ERAS management consist of patient‐reported outcomes, including functional recovery, role of ERAS in pelvic exenteration and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy, discharge pathways, and ERAS audit and reporting. We defined an eligible ERAS strategy as consisting of at least four domains related to ERAS practice (Chambers 2014). We considered traditional care strategies that did not adopt an ERAS protocol as comparators. Traditional care strategies may consist of preoperative overnight fasting, mechanical and antibiotic bowel preparation, intravenous fluids prior to surgery or anaesthesia, receiving pelvic drains during operation, receiving nasogastric tubes, and beginning a graduated oral intake until bowel sounds return after surgery. In this review, eligible comparators were traditional care strategies which did not consist of any ERAS components, which included some ERAS components without a standardised ERAS protocol, or which were implemented before the introduction of an ERAS protocol.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Length of postoperative hospital stay (i.e. the number of days from the day of surgery to discharge).

Postoperative complication rate within 30 days of operation, for example: acute confusion, nausea and vomiting, postoperative fever, secondary haemorrhage, atelectasis (i.e. the lack of gas exchange within alveoli owing to blood consolidation), pneumonia, wound infection, wound or anastomosis dehiscence (i.e. breakdown of the stitches), embolism and deep vein thrombosis, urinary retention, urinary tract infection, bowel obstruction owing to fibrinous adhesions, paralytic ileus, incisional hernia, persistent fistula (i.e. an abnormal connection or passageway between two organs or vessels that normally do not connect).

Early and late postoperative mortality from all causes (early mortality is defined as death within 30 days of operation; late mortality is defined as death within two to three months of operation).

Secondary outcomes

Readmission rate within 30 days of operation.

Bowel functions, including time to first flatus and time to first defaecation.

Quality of life, measured by a validated scale such as Medical Outcomes Study 36‐item Short Form Health Survey (SF‐36) and World Health Organization Quality of Life‐100 (WHOQOL‐100).

Participant satisfaction with hospital care.

Economic outcomes, including cost of care, direct, or indirect related costs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched 11 electronic databases.

This search was run for the original review in 2010 and subsequent searches were run in May 2012, November 2014, and October 2020. The Cochrane Information Specialist helped to define the search strategies for this update (Appendix 1, Appendix 2, and Appendix 3) and searched the following electronic databases:

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 10);

MEDLINE via Ovid (1946 to October week 2, 2020);

Embase via Ovid (1980 to 2020, week 42).

We also searched other English databases including PubMed, AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine), CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), and Scopus in October 2020, and adapted the search strategies accordingly. Additionally, we searched four Chinese databases including the China Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), WanFang Data, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Weipu Database. The search strategy for Chinese databases is shown in Appendix 4. There were no language, date, or publication status limitations for literature inclusion.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and Grey literature

We searched the following registries for ongoing trials: clinicaltrials.gov, www.who.int/clinical-trials-registry-platform/the-ictrp-search-portal, www.isrctn.com, and www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/clinical-trials/search. We contacted the main investigators of relevant trials for further information about the ongoing studies.

We also searched the following grey literature databases for relevant sources such as reports, dissertations, and conference abstracts: www.greynet.org/opensiglerepository.html, www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/ovid/99, and www.ntis.gov.

Handsearching

We handsearched the reference lists of all relevant trials obtained by the searches to identify any further trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

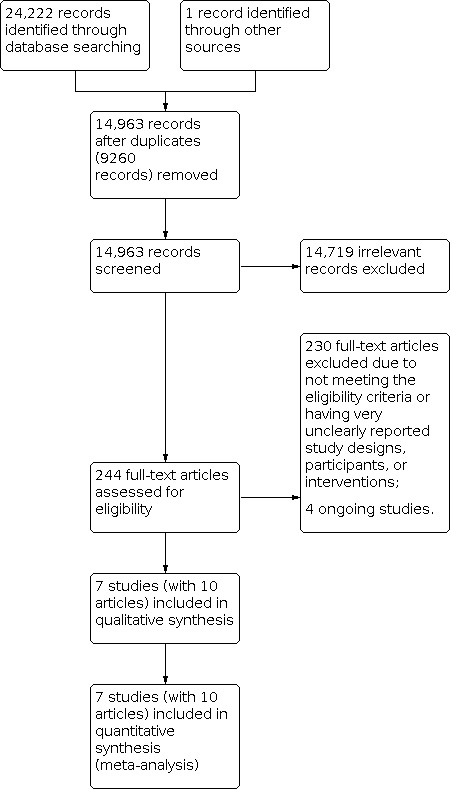

We downloaded all records retrieved from the electronic databases and imported them into Covidence, a Cochrane‐recommended tool to support authors in the stages of screening and data collection. After removing duplicates, two review authors (XL and JZ) screened the titles and abstracts independently. They excluded any studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. Two review authors (XL and JZ) then independently examined the full texts to assess their eligibility, resolving any disagreements by discussion between themselves. If consensus could not be reached, we included a third reviewer (JPC) to make recommendations for potential eligibility. The review authors documented reasons for exclusion. We drew a PRISMA flow diagram to display the selection process (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

We developed a data extraction list according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Li T 2019), and embedded it in Covidence. Two review authors (XL and JZ) independently extracted the following data from the included studies.

Study information: source of funding; duration, timing and location of the trial; author's contact details; study registration information; and potential conflicts of interest.

Methods: study design; details of randomisation and blinding; and methods used to address missing data.

Participants: inclusion and exclusion criteria; group differences in participants' demographic characteristics (e.g. age, socioeconomic status) and the prognostic factors for surgical recovery (e.g. smoking, comorbidities, American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification, and obesity) at baseline; type of gynaecological cancer; and type of surgical procedure.

Intervention and control: components of ERAS programmes according to the guidelines from the ERAS® Society (Nelson 2019); perioperative care in the control group; compliance with the interventions; and other identical perioperative co‐interventions in both groups.

Outcomes: prespecified primary and secondary outcomes, including their definitions, measurement tools and timing of outcome measurements; and the raw data of the outcomes.

We compared the extracted data and resolved any differences by discussion, or by including a third review author (SHL) if necessary. We attempted to contact authors to obtain missing or unclear information when necessary.

For dichotomous outcomes, we extracted the number of participants experiencing the event and the totals in each group of the trials. For continuous outcomes, we extracted the means with standard deviations (SDs). For some outcomes reported as medians with ranges or interquartile ranges (IQRs), we transformed the medians to means with SDs by applying the formulae provided by Luo 2018 and Wan 2014. To facilitate comparisons between trials, we converted variables that could have been reported in different metrics to a common metric. For example, we converted hours to days.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (XL and JZ) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included RCTs for all primary and secondary outcomes prespecified in the section Types of outcome measures. They resolved any disagreements by discussion between themselves or by involvement of a third review author (SHL). They assessed the risk of bias using an Excel tool developed from version two of the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) and the criteria specified in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019).

This included assessment of the following domains. The first domain was assessed at the study level, and the other four domains were assessed at the outcome level.

Bias arising from the randomisation process. This domain addresses issues about the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, and baseline differences between intervention and control groups that may suggest a problem with the randomisation process.

Bias due to deviations from intended interventions. In this review, the effect of interest is that of assignment to intervention. Therefore, we addressed the issues of whether the participants and the intervention providers delivering the interventions were aware of participants' assigned intervention during the trial, and whether there were deviations that did not reflect usual practice and affected the outcome.

Bias due to missing outcome data. This domain addresses whether the data for outcomes are available for all, or nearly all, participants randomised and, if applicable, the proportions of or the reasons for missingness in the outcomes.

Bias in measurement of the outcome. This domain addresses the appropriateness of measurement tools, measurement differences across groups, and the blinding of outcome assessors.

Bias in selection of the reported result. This domain addresses whether the analyses are in accordance with the protocols and whether there is selective reporting of a particular outcome or analysis.

There is a series of 'signalling questions' with five response options for each domain: 'yes', 'probably yes', 'probably no', 'no', and 'no information'. Two review authors answered the signalling questions according to the instructions in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2019), and the guideline for the RoB 2 tool (riskofbias.info/). We based our judgements on the risk of bias for each individual domain and the overall risk of bias for a result on algorithms that map responses to the signalling questions or the risk of bias judgements within domains to an overall judgement for a domain or a result. Possible judgments were: 'low risk of bias', 'some concerns', or 'high risk of bias'. We also recorded the supporting information for each judgement made. Responses to each signalling question within each domain across different outcomes are stored as supplemental files and deposited in an online repository.

Results are summarised in the risk of bias section of this review (located after the Characteristics of included studies) and in traffic lights on the forest plots. We interpreted the results of meta‐analyses in light of the findings with respect to risk of bias for the included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous outcomes (i.e. length of postoperative hospital stay, time to first flatus and time to first defaecation indicating bowel function, participant satisfaction, and cost) we analysed data reported using the same measures with the mean difference (MD), and used the standardised mean difference (SMD) when measures were different. For dichotomous outcomes (i.e. complications, death, and readmission), we used the risk ratio (RR) to present results. We did not identify ordinal outcome data or time‐to‐event outcome data in the included studies. We used a 95% confidence interval (CI) for all measures of treatment effect to reflect the uncertainty of the summary estimates.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was individuals. We did not identify any cluster‐RCTs in this systematic review.

Dealing with missing data

Missing outcome data from individual participants

We attempted to extract data from intention‐to‐treat analyses or for the outcomes among participants who were assessed at end point. We analysed only the available data and addressed the risk of bias due to incomplete outcome data in the risk of bias tool (RoB 2).

Missing summary data

Summary data for an outcome in a form that can be included in a meta‐analysis, for example, the SDs for continuous outcomes, may be missing. We obtained the missing data from other statistics, including standard errors, CIs, statistics, and P values. We also imputed the means and SDs from the medians with ranges and IQRs (see Data extraction and management). We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the results by removing studies with imputed means and SDs.

Missing study‐level characteristics for subgroup analyses

We conducted subgroup analyses by grouping studies with different characteristics. If necessary information was not available for some studies, we contacted the investigators to request missing data whenever possible and addressed the potential impact on the findings of the review in the discussion section.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between studies by visual inspection of forest plots and a formal statistical test of the significance of the heterogeneity. We employed I2statistic methods. We assumed the level of heterogeneity in the outcomes was substantial when the estimate of I2 reached 50%, and considerable when I2 reached 75% (Higgins 2019). If there was evidence of substantial heterogeneity, we investigated the possible reasons for this by subgroup analyses (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

We searched the protocols of every included study report to detect selective non‐reporting biases. If we could not find the protocols, we compared outcomes stated in the method section with the outcomes reported in the result section of the studies. When there were 10 or more studies included in a meta‐analysis, we planned to use funnel plots to assess the possibility that the results from studies with small‐sized or insignificant effects were missing from the meta‐analysis (Page 2019).

Data synthesis

If sufficient (usually two or more) clinically similar studies were available, we pooled their results in meta‐analyses. We considered that the intervention effects across studies had minimal similarity, so we used random‐effects models with inverse variance weighting for all meta‐analyses. For studies that could not be included in the meta‐analysis due to heterogeneity, we described the results narratively.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses if possible, grouping the trials by:

different types of surgical procedures (i.e. laparotomy versus laparoscopic surgery);

different types of gynaecological cancers;

different ERAS programmes with different ERAS components.

We considered factors such as age, stages of cancer, length of follow‐up and adjusted/unadjusted analysis in the interpretation of any heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We identified some studies that included a proportion of participants who did not meet the eligibility criteria (diagnosed as benign tumour). Thus, we conducted sensitivity analyses by removing studies with mixed participants to test whether the pooled results were influenced. To deal with missing summary data such as means with SDs, we imputed the data and used them in meta‐analyses. We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the results by removing studies with imputed data (see Dealing with missing data). We also carried out sensitivity analyses by excluding studies with high risk of bias.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

Two review authors (XL and JZ) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence with the GRADE profiler Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT). They resolved any disagreements by discussion or by involvement of a third review author (JPC). We categorised the certainty of the evidence as high, moderate, low, or very low, according to the assessment of its risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias, and magnitude of the effect. We included the following outcomes in the main summary of findings table: length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications within 30 days of operation, mortality within 30 days of discharge, readmission within 30 days of operation, time to first flatus, time to first defaecation, participant satisfaction, and economic outcomes (Table 1). We have presented the evidence for the other outcomes related to postoperative complications (such as nausea and vomiting) in the additional Table 2. We exported the summary of findings tables from GRADEpro GDT.

1. GRADE assessment results on evidence about postoperative complications within 30 days of operation.

| Enhanced recovery after surgery programme compared to traditional care for women with gynaecological cancers | ||||||

|

Patient or population: women with

gynaecological cancers Setting: hospital‐based gynaecological cancer perioperative care Intervention: enhanced recovery after surgery programme Comparison: traditional care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What this means | |

| Risk with traditional care | Risk with enhanced recovery after surgery programme | |||||

| Postoperative acute confusion | 20 per 1000 | 20 per 1000 (1 to 311) | RR 0.98 (0.06 to 15.23) | 99 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the ERAS programme on postoperative acute confusion. |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 257 per 1000 | 134 per 1000 (85 to 216) | RR 0.52 (0.33 to 0.84) | 642 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate c | ERAS programmes likely reduced postoperative nausea and vomiting. |

| Postoperative fever | 167 per 1000 | 133 per 1000 (40 to 448) | RR 0.80 (0.24 to 2.69) | 60 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b,d | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the ERAS programme on postoperative fever. |

| Postoperative secondary haemorrhage | 13 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (2 to 80) | RR 0.94 (0.14 to 6.29) | 309 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on postoperative secondary haemorrhage. |

| Postoperative pneumonia | 29 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (2 to 79) | RR 0.41 (0.06 to 2.75) | 217 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on postoperative pneumonia. |

| Postoperative wound infection | 70 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (1 to 161) | RR 0.13 (0.01 to 2.29) | 107 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the ERAS programme on postoperative wound infection. |

| Postoperative anastomosis dehiscence | 20 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (4 to 427) | RR 1.96 (0.18 to 20.92) | 99 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the ERAS programme on postoperative anastomosis dehiscence. |

| Postoperative embolism and deep vein thrombosis | 28 per 1000 | 4 per 1000 (0 to 75) | RR 0.14 (0.01 to 2.64) | 206 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on postoperative embolism and deep vein thrombosis. |

| Postoperative ileus | 97 per 1000 | 55 per 1000 (29 to 104) | RR 0.57 (0.30 to 1.07) | 492 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low b,e | ERAS programmes result in no difference in postoperative ileus. |

| Postoperative colorectal anastomotic fistula | 20 per 1000 | 40 per 1000 (4 to 427) | RR 1.96 (0.18 to 20.92) | 99 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low a,b | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of the ERAS programme on postoperative colorectal anastomotic fistula. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aImprecision downgraded two levels due to very small sample size or low incidence of events and inclusion of appreciable benefit and harm in confidence intervals. bPublication bias downgraded because data were reported by limited number of studies. cInconsistency downgraded because the pooled results changed substantially when excluding a small study with positive results (Ho 2020). dRisk of bias downgraded one level because of suspected deviations from intended interventions. eImprecision downgraded one level as confidence interval of pooled estimate includes appreciable benefit and no effect

Results

Description of studies

Studies that we included and excluded from this review, and ongoing studies, are described in tables (see Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Results of the search

We initially obtained a total of 24,223 records from electronic searching and other resources. After removal of duplicates, two review authors screened 14,963 records independently. They sought a total of 244 full texts for detailed assessment after title and abstract screening. We excluded 230 full‐text articles and identified seven eligible studies (with 10 references) (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), and four ongoing RCTs (ChiCTR1900025117; NCT02864277; NCT03640299; NCT04063072). See Figure 1 for the process of record screening and study selection.

Included studies

The review included seven studies with 747 participants. Details of the included studies are shown in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Three studies were conducted in China (Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), one in the USA (Dickson 2017), one in Spain (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020), one in Italy (Ferrari 2020), and one in Malaysia (Ho 2020). The settings of the studies included the departments of gynaecologic oncology or the departments of obstetrics and gynaecology at university hospitals or medical centres (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Zhou 2020), comprehensive cancer centres (Ho 2020; Shi 2020), a general hospital (Zhang 2016), and a referral centre for gynaecologic oncology (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). All studies were conducted in a single centre. The studies took place between 2012 and 2019.

1. Design

We included seven RCTs (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020). All the RCTs were prospective parallel studies.

2. Participants

2.1 Age

All studies reported the mean ages of women, which were between 48.4 to 57.3 years old.

2.2 Diagnosis

Five studies only recruited participants with suspected or confirmed gynaecological cancer (Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020). The other two studies recruited participants with benign, borderline, or malignant gynaecologic tumours, of which the proportions of participants with malignant tumours were 51.1% (Ferrari 2020), and 64.1% (Dickson 2017). Of the five studies including participants with cancer, two studies only included participants with one type of cancer: ovarian cancer (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020); and cervical cancer (Zhang 2016). Five studies consisted of participants with different types of cancer, including cervical cancer, uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer, and carcinosarcoma (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Shi 2020; Zhou 2020). Some researchers recruited specific groups of participants based on the stage of cancer (e.g. according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stages of gynaecological cancer); for example, Zhang 2016 only recruited participants with stage I‐II cancer; and Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020 recruited participants with advanced stages of cancer (FIGO stages IIb‐IVa, and relapses).

2.3 Type of surgery

Three studies only recruited participants undergoing laparotomy (Dickson 2017; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). Two studies only recruited participants undergoing laparoscopic surgeries (Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020). Two studies included participants undergoing both laparotomies and laparoscopic surgeries in both the intervention and control groups (Ferrari 2020; Shi 2020).

2.4 Exclusion criteria

Reported exclusion criteria included participants with severe complications or dysfunctions (Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), undergoing emergency/unplanned surgeries (Dickson 2017; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020), with poor physical condition that put them at high risk from undergoing anaesthesia and surgery (i.e. American Society of Anesthesiologists level ≥ 4) (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Zhou 2020), receiving an anti‐tumour treatment such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy before operation (Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), and undergoing surgery for vulval cancer (due to short hospital stay, usually < 1 day; Dickson 2017). For other details, see the Characteristics of included studies table.

3. Interventions

According to the 17 domains specified in the updated ERAS® Society guidelines that relate to ERAS pre‐, intra‐, and postoperative practices for gynaecological oncology (Nelson 2019), we depicted the exact ERAS components adopted in each of the included studies (Figure 2). ERAS components varied among included studies and the number of domains adopted ranged between 8 and 15 (median = 12). The most widely adopted domains (reported in all seven studies) were: preadmission information, education and counselling, preoperative fasting and carbohydrate treatment, early feeding after operation (i.e. perioperative nutrition domain), and early mobilisation after operation. Another five domains were adopted in six of the seven studies: limited preoperative mechanical bowel preparation, prevention of hypothermia, nausea and vomiting prophylaxis, perioperative fluid management/goal‐directed fluid treatment and opioid sparing postoperative analgesics. Only one study reported the intervention on prehabilitation in its ERAS pathway (Zhou 2020).

2.

ERAS domains adopted in the included studies (intervention group)

Four studies reported the level of compliance with ERAS components (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). Overall, postoperative compliance rates were generally high (usually ≥70%). Components with relatively lower compliance rates (< 70%) included avoidance of peritoneal drainage (61.4%) and energy intake on postoperative day 0 (65.1%), which were reported by Ferrari 2020.

As described in the included studies, three studies applied traditional care strategies (e.g. preoperative overnight fasting and mechanical bowel preparation) with no ERAS components (Dickson 2017; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Zhang 2016). Four studies applied traditional care strategies with several ERAS components (in addition to minimally invasive surgery) but without an ERAS protocol (Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Shi 2020; Zhou 2020). The review authors addressed sufficient discrimination between the intervention and control groups in these four studies through displaying compliance to the intervention components or by adding an explanation for the situation.

4. Outcomes

The studies reported data for length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications within 30 days of operation, mortality from all causes within 30 days of discharge (rather than our planned outcome of within 30 days of operation), readmission within 30 days of operation, bowel functions (including time to first flatus and time to first defaecation), participant satisfaction, and economic costs. No study reported the outcome that described five types of postoperative complications (i.e. urinary retention, urinary tract infection, incisional hernia, atelectasis, and wound dehiscence), and none reported quality of life.

Excluded studies

There were some studies that did not meet all the criteria, but which a reader might plausibly expect to see among the included studies; we selected and listed 28 excluded studies and detailed the primary reason for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Two were excluded because less than 50% of the participants were diagnosed with gynaecological cancer (Miller 2015; Wijk 2014). Four studies examined only a single component of ERAS (Belavy 2013; Feng 2008; Gerardi 2008; Janda 2014), while two studies compared participant outcomes between the first year and the second year after the implementation of ERAS programmes (Mukhopadhyay 2015; Pather 2011). The remaining 20 studies were non‐RCTs.

Risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias assessments for each outcome, including all domain judgements and support for judgement, are presented in the risk of bias section of this review (located after the Characteristics of included studies) and in traffic lights on the forest plots. To assess detailed responses to each signalling question within each domain across different outcomes, please use the following link (doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NRKF38).

Length of postoperative hospital stay

This outcome had a high overall risk of bias. Other than Ferrari 2020, all the studies reporting this outcome had a high risk of bias due to bias in measurement of outcomes (Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020 ), or deviations from intended interventions (Zhou 2020). We assessed the outcomes reported in Ferrari 2020, as well as Zhang 2016 and Zhou 2020, as having 'some concerns' about the randomisation process because they only reported the generation of allocation sequence and did not provide further details on allocation concealment.

Postoperative complications within 30 days of operation

Risk of bias of outcomes related to postoperative complications across all studies was similar and predominately assessed as having 'some concerns'. The only exception was postoperative fever (only reported in Zhou 2020), which we judged to be at high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions.

Early and late mortality from all causes within 30 days of operation

Only Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020 reported early mortality from all causes within 30 days of discharge. We assessed this outcome as having 'some concerns' due to deviations from intended interventions.

Readmission rate within 30 days of operation

This outcome had a high overall risk of bias due to bias in measurement of outcomes (Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). We also assessed this outcome as having 'some concerns' due to randomisation process (Ferrari 2020), and deviations from intended interventions (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020).

Bowel function recovery

We assessed the time to first flatus and time to first defaecation, which are observer‐reported outcomes not involving judgement, as having 'some concerns' regarding randomisation process (Ferrari 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), and reporting bias (Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), and having 'some concerns' (Zhang 2016) or a high risk of bias (Zhou 2020) due to deviations from intended interventions.

Participant satisfaction with hospital care

We assessed the outcome as having a high overall risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions (Zhou 2020), and having 'some concerns' on the randomisation process, measurement, and reporting bias.

Economic outcomes

We assessed the outcome as having a high overall risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions and measurement of the outcomes (Shi 2020; Zhou 2020), and having 'some concerns' about the randomisation process and reporting bias (Zhou 2020).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1. Length of postoperative hospital stay

All studies included data on length of postoperative hospital stay, abstracted from medical records and reported in different forms. Four studies reported the means with SDs (Ho 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), one reported the median with IQR (Ferrari 2020), one reported the median with range (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020), and one reported the median with a 95% confidence interval (Dickson 2017).

In each of the included studies, women in the ERAS and control groups had identical discharge criteria. The criteria judged by the gynaecologists included: tolerance to solid foods without discomfort such as nausea and vomiting (in all seven studies), absence of complications such as fever and haemorrhage (in all seven studies), adequate control of pain (in six studies), ability to mobilise independently (in five studies), passage of stool or flatus (in four studies), and participants’ agreement to be discharged (in three studies).

ERAS programmes could result in a reduction in the length of postoperative hospital stay, with an MD of ‐1.71 days (95% CI ‐2.59 to ‐0.84; I2 = 86%; 6 studies, 638 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). However, considerable heterogeneity was detected. We conducted meta‐analyses because the directions of the effect were consistent in the majority of included studies. It was shown that ERAS programmes reduced length of postoperative hospital stay in women undergoing laparotomy (MD ‐1.92 days, 95% CI ‐2.99 to ‐0.85; I2 = 92%; 3 studies, 312 participants) and laparoscopic surgeries (MD ‐1.81, 95% CI ‐3.34 to ‐0.29; I2 = 82%; 3 studies, 219 participants), without significant subgroup differences detected (P = 0.91, I2= 0%; Analysis 1.2). The results of sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled result was not substantially affected by the inclusion of a study with both benign and malignant oncology patients (Analysis 1.3), or introducing transformed mean values (Analysis 1.4). We did not pool the data Dickson 2017 because the median with 95% CI reported could not be transformed to mean with SD. Dickson 2017 found that there was no difference between the ERAS and traditional care groups in length of postoperative hospital stay in people undergoing laparotomy (median = 3.0 in both groups; P = 0.36).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 1: Outcome 1: length of postoperative hospital stay

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 2: Outcome 1: length of postoperative hospital stay—subgroup analysis—surgery type

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 3: Outcome 1: length of postoperative hospital stay—sensitivity analysis 1 (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 4: Outcome 1: length of postoperative hospital stay—sensitivity analysis 2 (excluding studies introducing transformed outcome value)

2. Postoperative complications

All seven studies reported postoperative complications within 30 days of operation. We did not find any studies that reported data on postoperative urinary retention, urinary tract infection, incisional hernia, atelectasis, or wound dehiscence, which were prespecified in the protocol.

2.1 Overall complications

Five studies reported an overall complication rate during primary stay and after surgery up to 30 days (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhou 2020). We found that there might be no difference in overall complication rates with ERAS programmes within 30 days of operation (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.05; I2 = 42%; 5 studies, 537 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5) in both types of surgery (Analysis 1.6). The results of sensitivity analyses showed that the pooled result was consistent after excluding studies with participants with both benign and malignant tumours (Analysis 1.7).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 5: Outcome 2.1: overall postoperative complications

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 6: Outcome 2.1: overall postoperative complications—subgroup analysis—surgery type

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 7: Outcome 2.1: overall postoperative complications—sensitivity analysis (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

2.2 Acute confusion

One RCT reported the occurrence of acute confusion (i.e. delirium; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020) and no significant difference was reported between groups (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.06 to 15.23; 99 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 8: Outcome 2.2: postoperative complication—acute confusion

2.3 Nausea and vomiting

Six studies reported postoperative nausea and vomiting (emesis) (Dickson 2017; Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Shi 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020). ERAS programmes likely reduced the occurrence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.84; I2 = 42%; 6 studies, 642 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.9). However, the subgroup analysis found ERAS programmes did not reduce the occurrence of postoperative nausea and vomiting in participants who underwent laparotomy (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.19 to 1.51; I2 = 84%; 2 studies, 221 participants) or laparoscopic surgeries (RR 0.53, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.25; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 146 participants), without significant subgroup differences detected (P = 0.97, I2= 0%; Analysis 1.10). The results of sensitivity analyses indicated that the pooled results were not affected by the inclusion of studies with participants with both benign and malignant tumours (Analysis 1.11).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 9: Outcome 2.3: postoperative complication—nausea and vomiting

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 10: Outcome 2.3: postoperative complication—nausea and vomiting—subgroup analysis—surgery type

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 11: Outcome 2.3: postoperative complication—nausea and vomiting—sensitivity analysis (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

2.4 Fever

Only one RCT (Zhou 2020) reported the effects of ERAS programmes on postoperative fever (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.24 to 2.69; 60 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.12). The evidence was very uncertain due to serious risk of bias, imprecision and publication bias.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 12: Outcome 2.4: postoperative complication—fever

2.5 Secondary haemorrhage

Three studies reported the complication of postoperative secondary haemorrhage (Dickson 2017; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020). Pooled results indicated that the evidence on the effect of ERAS programmes on postoperative secondary haemorrhage was very uncertain, due to imprecision and publication bias (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.29; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 309 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 13: Outcome 2.5: postoperative complication—secondary haemorrhage

2.6 Pneumonia

Two studies reported the complication of postoperative pneumonia (Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). Pooled results indicated that the evidence on the effect of ERAS programmes on postoperative pneumonia was very uncertain, due to imprecision and publication bias (RR 0.41, 95% CI 0.06 to 2.75; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 217 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 14: Outcome 2.6: postoperative complication—pneumonia

2.7 Wound infection

Only Shi 2020 reported the outcome of wound infection. The evidence on the effect of ERAS programmes on the occurrence rate of wound infection was very uncertain (RR 0.13, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.29; 1 study, 107 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 15: Outcome 2.7: postoperative complication—wound infection

2.8 Anastomosis dehiscence

Only Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020 reported the outcome of anastomosis dehiscence. The evidence on the effect of ERAS programmes on the occurrence of anastomosis dehiscence was very uncertain (RR 1.96, 95% CI 0.18 to 20.92; 1 study, 99 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 16: Outcome 2.8: postoperative complication—anastomosis dehiscence

2.9 Embolism and deep vein thrombosis

Two studies reported data on embolism and deep vein thrombosis (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020). The evidence on the effect of ERAS programmes on the occurrence rate of embolism and deep vein thrombosis was very uncertain (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.64; 2 studies, 206 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.17).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 17: Outcome 2.9: postoperative complication—embolism and deep vein thrombosis

2.10 Ileus

Four studies reported data on postoperative ileus (Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020). ERAS programmes may have no effect on the incidence of postoperative ileus (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.07; I2 = 0%; 4 studies, 492 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.18). The pooled result was similar when excluding the study that included both participants with benign and malignant tumours from the sensitivity analysis (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.26; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 324 participants = 324; Analysis 1.19).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 18: Outcome 2.10: postoperative complication—ileus

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 19: Outcome 2.10: postoperative complication—ileus—sensitivity analysis (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

2.11 Colorectal anastomotic fistula

Only Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020 reported data on postoperative colorectal anastomotic fistula. The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on the rate of postoperative colorectal anastomotic fistula (RR 1.96, 95% CI 0.18 to 20.92; 1 study, 99 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.20).

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 20: Outcome 2.11: postoperative complication—colorectal anastomotic fistula

3. Mortality

Only Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020 reported early mortality from all causes. The study reported this outcome as mortality within 30 days of discharge, rather than our planned outcome of within 30 days of operation. The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on all‐cause mortality within 30 days of discharge (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.14 to 6.68; 1 study, 99 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.21). There were no data on late mortality, which was defined as death within two to three months in all causes.

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 21: Outcome 3: mortality

4. Readmission

Three studies reported readmission rates within 30 days of operation (Ferrari 2020; Ho 2020; Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020). ERAS programmes may reduce the risk of readmission within 30 days of operation (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.90; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 385 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.22). The pooled result was similar when excluding the study whose participants had both benign and malignant tumours (RR 0.35, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.80; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 217 participants; Analysis 1.23).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 22: Outcome 4: readmission

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 23: Outcome 4: readmission—sensitivity analysis (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

5. Bowel function

Five studies reported the outcomes related to bowel function, including time to first flatus and time to first defaecation.

5.1 Time to first flatus

Three studies reported the time to first flatus in means with SDs (Ho 2020; Zhang 2016; Zhou 2020), one reported only the mean (Ferrari 2020), and one reported the number of participants who had their first flatus on postoperative day one, day two, day three, and day four or beyond (Dickson 2017). ERAS programmes may result in a reduction in the time to first flatus (MD ‐0.82 days, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.63; I2 = 35%; 4 studies, 432 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.24). However, Dickson 2017, whose data could not be pooled with the other studies, reported no significant difference in the distributions of the time to first flatus. Subgroup analyses showed that ERAS programmes reduced the time to first flatus in participants who underwent laparotomy surgery (MD ‐1.03 days, 95% CI ‐1.30 to ‐0.76; 1 study, 118 participants) and laparoscopic surgery (MD ‐0.74 days, 95% CI ‐0.87 to ‐0.61; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 146 participants), with significant subgroup differences detected (P = 0.06, I2= 71.7%; Analysis 1.25). The pooled results were substantially similar when excluding the study with both benign and malignant oncology participants (Analysis 1.26).

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 24: Outcome 5.1: bowel function—time to first flatus

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 25: Outcome 5.1: bowel function—time to first flatus—subgroup analysis—surgery type

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 26: Outcome 5.1: bowel function—time to first flatus—sensitivity analysis (excluding studies on participants with both benign and malignant tumours)

5.2 Time to first defaecation

As for the time to first defaecation, Zhou 2020 reported the mean with a SD and Ferrari 2020 reported the mean without a SD. ERAS programmes may reduce the time to first defaecation (MD ‐0.96 days, 95% CI ‐1.47 to ‐0.44; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 228 participants; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.27).

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 27: Outcome 5.2: bowel function—time to first defaecation

6. Participant satisfaction

Different measurement tools were used by Ferrari 2020 and Zhou 2020 to survey participant satisfaction with hospital care. Ferrari 2020 investigated participant satisfaction 24 hours after surgery and at discharge using Quality of Recovery‐15 (QoR‐15), which has 15 items with acceptable reliability and validity (Stark 2013). Zhou 2020 adopted a self‐developed 10‐item questionnaire surveying participant satisfaction with nursing service, competencies, health education, and ward management. The total scores ranged from 20 to 100. The Cronbach's alpha of the scale was 0.855 in Zhou 2020. Further information about the questionnaire was not reported in the literature.

The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on participant satisfaction due to serious risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency and publication bias (SMD 0.92, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.78; I2 = 86%; 2 studies, 228 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.28).

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 28: Outcome 6: participant satisfaction

7. Economic outcomes

Three studies reported economic outcomes (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020; Shi 2020; Zhou 2020). Shi 2020 and Zhou 2020 measured the total hospital expenditures but did not provide detailed information on the constitution of the expenditures. The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on economic costs (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.25; I2 = 54%; 2 studies, 167 participants; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.29). However, one study that was not included in the pooled analysis due to lack of usable data regarding actual cost saving indicated that the ERAS protocol resulted in an annual cost reduction of 13,330 euros for 100 patients in the best scenario (Sánchez‐Iglesias 2020).

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1: ERAS programmes versus traditional care, Outcome 29: Outcome 7: economic outcomes

Discussion

Summary of main results

In this review, we searched for RCTs comparing ERAS programmes with traditional care strategies for women with gynaecological cancer after surgery. We included seven RCTs with 747 women. Primary outcomes reported in trials included length of postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications, and mortality within 30 days of discharge. Secondary outcomes included readmission within 30 days of operation, return of bowel function postsurgery, participant satisfaction and cost.

Primary outcomes

ERAS programmes may result in a reduction in the length of postoperative hospital stay (MD ‐1.71 days, 95% CI ‐2.59 to ‐0.84; I2 = 86%; 6 studies, 638 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

ERAS programmes may result in no difference in overall postoperative complication rates (RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.05; I2 = 42%; 5 studies, 537 participants; low‐certainty evidence). As for the other postoperative complications, ERAS programmes likely reduced the occurrence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.84; I2 = 42%; 6 studies, 642 participants; moderate‐certainty evidence); the evidence was very uncertain for other complications such as acute confusion, fever, second haemorrhage, pneumonia, wound infection, anastomosis dehiscence, embolism and deep vein thrombosis, and colorectal anastomotic fistula due to serious risk of bias, imprecision, and publication bias. ERAS programmes have no effect on the incidence of postoperative ileus (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.07; I2 = 0%; 4 studies, 492 participants; low‐certainty evidence). The evidence was very uncertain about the effect of ERAS programmes on all‐cause mortality within 30 days of discharge.

Secondary outcomes

ERAS programmes may reduce readmission rates within 30 days of operation (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.22 to 0.90; I2 = 0%; 3 studies, 385 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

ERAS programmes may facilitate recovery of postoperative bowel functions, as indicated by the reduction of time to first flatus (MD ‐0.82 days, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.63; I2 = 35%; 4 studies, 432 participants; low‐certainty evidence) and time to first defaecation (MD ‐0.96 days, 95% CI ‐1.47 to ‐0.44; I2 = 0%; 2 studies, 228 participants; low‐certainty evidence).

The evidence for the effects of ERAS programmes on participant satisfaction was very uncertain due to the limited number of studies found. Adoption of ERAS strategies might not increase medical expenditure. However, the evidence was of very low certainty (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.25; I2 = 54%; 2 studies, 167 participants).

Intervention compliance is important for multi‐component interventions such as ERAS. The overall compliance rates (reported in four out of seven studies) were generally high (usually ≥ 70%) with the exception of some components, such as early feeding and avoidance of peritoneal drainage. However, bias might exist since the low compliance rates of the interventions might not be reported by other researchers. Domains adopted in the majority of ERAS programmes included preadmission information, education and counselling, preoperative fasting and carbohydrate treatment, early feeding after operation (i.e. perioperative nutrition domain), early mobilisation after operation, limited preoperative mechanical bowel preparation, prevention of hypothermia, nausea and vomiting prophylaxis, perioperative fluid management/goal‐directed fluid treatment, and opioid sparing postoperative analgesia.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall completeness and applicability of the evidence available for the effects of ERAS programmes for women with gynaecological cancer is currently inadequate. Caution is needed when interpreting the evidence.