Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the safety and efficacy of regorafenib combined with anti-PD-1 antibody sintilimab (rego-sintilimab) as a second-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

This multicenter retrospective study evaluated consecutive patients with advanced HCC who received rego-sintilimab (rego-sintilimab group) or regorafenib alone (regorafenib group) as a second-line treatment from January 2019 to December 2020. Adverse events, objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) were compared between the two groups. Uni- and multi-variable analyses of prognostic factors for OS and PFS were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression models.

Results

In total, 113 patients were included in the study: 58 received rego-sintilimab and 55 received regorafenib. The rego-sintilimab group had higher ORR (36.2% vs 16.4%, P = 0.017), longer PFS (median 5.6 vs 4.0 months; P = 0.045), and better OS (median 13.4 vs 9.9 months; P = 0.023) than the regorafenib group. Regorafenib alone, Child-Pugh B, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) > 3.6 were independent prognostic factors for poor OS. Regorafenib alone, α-fetoprotein level, and NLR > 3.6 were independent prognostic factors for poor PFS. Subgroup analyses showed a survival benefit of rego-sintilimab in patients with NLR ≤ 3.6 (hazard ratio 0.518 [95% CI, 0.257–0.955]) but not in those with NLR > 3.6 (0.852 [0.461–1.572]); P = 0.002 for interaction. The difference in incidence of grade 3/4 adverse events between the two groups was not statistically significant (39.7% vs 30.9%; P = 0.331).

Conclusion

Rego-sintilimab was tolerated and led to better OS than regorafenib as a second-line treatment for advanced HCC patients, especially in those with NLR ≤ 3.6.

Keywords: liver cancer, regorafenib, anti-PD-1 antibody, second-line treatment, overall survival, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

Introduction

Despite recent improvements in surveillance programs, 50–75% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are diagnosed at an advanced stage.1 Multi-kinase inhibitor sorafenib and lenvatinib are the first-line treatments for advanced HCC, as recommended by updated Barcelona Clinical Liver cancer (BCLC) treatment algorithms.1 However, these two drugs only result in a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 3.7–7.3 months,2,3 and a second-line treatment is needed after disease progression. Multi-kinase inhibitor regorafenib,4 cabozantinib,5 and VEGFR-2 inhibitor ramucirumab6 are appropriate for pretreated patients with advanced HCC. Nonetheless, these second-line treatments only result in an objective response rate (ORR) of 4–11% and a median overall survival (OS) of 8.5–10.6 months versus a median OS of 7.3–8.0 months for patients treated with placebo. Among the current standard second-line HCC therapies, regorafenib appears to be the best choice in terms of OS.7 However, given the low ORR and modest improvement in OS, a more effective second-line treatment is needed.

Immunotherapy with anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody is a possible second-line option. Data from Phase 1/2 trials have shown durable responses with anti-PD-1 antibodies, including nivolumab and pembrolizumab, in HCC patients for whom prior sorafenib treatment had failed;8,9 however, phase 3 data for pembrolizumab has failed to demonstrate any improvement in OS compared with placebo in a second-line setting.10 As anti-PD-1 antibody monotherapy has not proved to be significantly effective, combinations of anti-PD-1 antibody and tyrosine-kinase inhibitors or VEGF inhibitors are being widely considered.11 Regorafenib is a potent VEGFR2/3 inhibitor, which may lead to a promising ORR in combination with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy.12 In an HCC model, the combination of regorafenib and anti-PD-1 antibody has been shown to increase intratumoral CD8+ T-cell infiltration by normalizing the tumor vasculature13 and subsequently improving the efficacy of the anti-PD-1 antibody.

Recently, anti-PD-1 antibody sintilimab combined with a VEGF inhibitor (a bevacizumab biosimilar) showed a significant OS benefit versus sorafenib as a first-line treatment for Chinese HCC patients.14 Sintilimab has a high PD-1 occupancy rate (> 95%)15 and long occupancy duration on circulating T cells,16 indicating a potentially powerful anti-tumor immune effect. Considering the characteristics of regorafenib and sintilimab described above, it is reasonable to speculate that their combination (rego-sintilimab) may have an advantage over the current standard second-line regorafenib monotherapy. Therefore, this multicultural retrospective study aimed to investigate the safety and efficacy of rego-sintilimab, in comparison with regorafenib alone, for advanced HCC patients in a second-line setting.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

We reviewed the electronic medical records of consecutive patients with advanced HCC who received rego-sintilimab or regorafenib after disease progression on sorafenib or lenvatinib treatment, from January 2019 to December 2020, at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Jieyang People’s Hospital, and the First People’s Hospital of Zhaoqing. Patients were assigned to receive either rego-sintilimab or regorafenib, according to the patient’s decision and the attending physician’s suggestion. This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review boards of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, Jieyang People’s Hospital, and the First People’s Hospital of Zhaoqing. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to treatment.

HCC was diagnosed according to the European Association for the Study of Liver and American Association for the study of Liver Disease guidelines.17 The inclusion criteria for the study population were as follows: 1) age between 18 and 75 years; 2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0 or 1; 3) BCLC stage C HCC; 4) Child-Pugh A or B liver function; and 5) radiographic disease progression on first-line treatment with sorafenib or lenvatinib. Patients were excluded from this study if they 1) had previously received targeted therapy in addition to sorafenib or lenvatinib monotherapy; 2) had previously received immunotherapy; 3) currently or previously had any malignant tumor in addition to HCC; 4) had severe medical comorbidities including severe organ dysfunction and coagulation disorders, such as creatinine ≥1.5 upper limit of normal or international normalized ratio ≥1.5; or 5) had a follow-up less than 3 months.

Data Collection

Baseline characteristics were collected within 1 week before the initiation of rego-sintilimab or regorafenib treatment. Inflammation-based prognostic scores consisting of the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) were calculated based on the baseline data. NLR was calculated as the neutrophil count divided by the lymphocyte count, and PLR was calculated as the platelet count divided by the lymphocyte count.18

All dynamic computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging analyses, including analyses of tumor size, tumor number, macrovascular invasion, extrahepatic metastasis, and treatment response, were conducted independently by two diagnostic radiologists who were blinded to treatment allocation and clinical information. When there was any ambiguity, the final determination was made by consensus.

Treatment Protocol and Adjustment

Regorafenib was initially prescribed at 120 mg/day, which could be adjusted to 160 or 80 mg/day according to the patient’s tolerance, during weeks 1–3 of each 4-week cycle. Sintilimab (Innovent Biologics, Suzhou, China) was prescribed at a fixed dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks.

Follow-up of patients was conducted at 3- to 6-week intervals. Treatment was discontinued in cases of progressive disease confirmed by CT or MR imaging at follow-up, or where patients had hepatic decompensation with Child-Pugh C or clinical progression to ECOG performance status > 2, or intolerable toxicity even after the dose adjustment of regorafenib (to 80 mg/day), or treatment interruption. Patients who experienced intolerable toxicity in the rego-sintilimab group could discontinue either regorafenib or sintilimab treatment and retain the other following their physician’s suggestion. Patients discontinuing second-line treatment might receive post-line treatments such as apatinib, and/or anti-PD-1 antibody immunotherapy other than sintilimab, and/or regional therapies, ie, transarterial chemoembolization, or iodine 125 seed implantation for patients with Child-Pugh A/B and ECOG score 0–2, or best support treatment for patients with Child-Pugh C or ECOG score > 2, according to the attending physicians’ consensus.

Outcomes

Adverse events (AEs) related to treatment were recorded according to National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 5.0.19

Treatment responses were assessed based on dynamic CT or MR imaging, according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.120 and modified RECIST.21 ORR was defined as the incidence of complete response and partial response. Disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the incidence of complete response, partial response, and stable disease.

PFS was defined as the time from the initiation of regorafenib until the date when tumor progression or death was confirmed or the last follow-up in censored data. OS was defined as the time from the initiation of regorafenib until death or the last follow-up in censored data.

Statistical Analyses

Categorical data are presented as numbers (percentages) and quantitative data as median values (interquartile range [IQR]) unless otherwise indicated. Pearson’s χ2-test, correction of continuity, or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical data (baseline patient characteristics, AEs, and treatment responses) between the two groups, as appropriate. Mann–Whitney U-test or Student’s t-test was used to compare quantitative data (baseline characteristics or mean dose of regorafenib) between the two groups. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to determine the optimal cut-off values of lymphocyte, neutrophil, and platelet levels, NLR, and PLR for predicting 1-year survival. OS and PFS curves were constructed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and the Log rank test was used for comparisons. Univariate analyses and multivariate analyses of prognostic factors for OS and PFS were performed with Cox proportional hazard regression models. Variables with P<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. All tests were two-sided and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Study Population

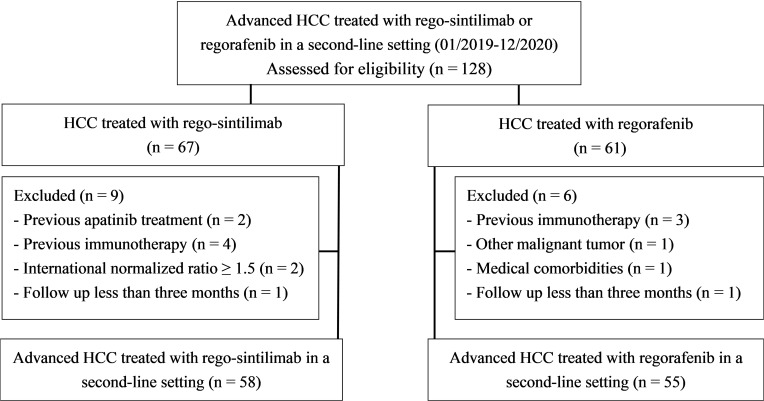

A total of 128 patients with advanced HCC who received rego-sintilimab or regorafenib as a second-line treatment were assessed for eligibility during the study period. Fifteen patients were excluded because they met the exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Finally, 113 patients were included in this study (rego-sintilimab group, n = 58; regorafenib group, n = 55). The baseline characteristics between the two groups were not significantly different (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing exclusion of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who received regorafenib combined with sintilimab (rego-sintilimab) or regorafenib in a second-line setting.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics at Initiation of Second-Line Treatment

| Characteristic | Rego-Sintilimab Group (N = 58) | Regorafenib Group (N = 55) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 51 (87.9) | 50 (90.9) | 0.608 |

| Age (years) | 54 (41–62) | 51 (47–63) | 0.776 |

| ECOG score 1 | 23 (39.7) | 28 (50.9) | 0.230 |

| Positive for HBsAg | 48 (82.8) | 49 (89.1) | 0.335 |

| Child-Pugh B | 21 (36.2) | 20 (36.4) | 0.986 |

| Presence of ascites | 14 (24.1) | 13 (23.6) | 0.950 |

| Tumor diameter (cm) | 6.4 (4.3–9.5) | 5.5 (4.3–8.5) | 0.531 |

| Tumor size >5 cm | 40 (69.0) | 34 (61.8) | 0.424 |

| >3 intrahepatic tumors | 42 (72.4) | 41 (74.5) | 0.798 |

| Macrovascular invasion | 40 (69.0) | 31 (56.4) | 0.166 |

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 37 (63.8) | 29 (52.7) | 0.233 |

| First-line treatment with lenvatinib† | 23 (39.7) | 20 (36.4) | 0.719 |

| Time on first-line treatment (months) | 7.3 (4.1–12.0) | 7.5 (3.7–14.6) | 0.508 |

| Previous treatment procedures | 0.996 | ||

| Surgery or radical ablation | 15 (25.9) | 14 (25.5) | |

| TACE or HAIC ‡ | 38 (65.5) | 36 (65.5) | |

| Others § | 5 (8.6) | 5 (9.1) | |

| Laboratory test | |||

| α-fetoprotein (ng/mL) | 1087 (19–16,763) | 264 (19–5455) | 0.299 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 30 (21–48) | 37 (28–49) | 0.110 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 45 (32–83) | 47 (31–67) | 0.927 |

| Total bilirubin (μmol/L) | 13.3 (9.0–20.2) | 14.8 (9.7–25.3) | 0.222 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 35.4 (31.3–39.4) | 34.7 (32.0–38.9) | 0.508 |

| Lymphocyte (109/L) | 1.05 (0.72–1.49) | 0.91 (0.74–1.33) | 0.373 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 2.92 (2.39–3.76) | 2.79 (2.04–4.26) | 0.776 |

| Platelet (109/L) | 143 (102–225) | 113 (84–176) | 0.299 |

| Inflammation-based prognostic score | |||

| NLR | 2.81 (1.92–5.33) | 3.56 (2.01–5.64) | 0.640 |

| PLR | 155 (95–198) | 137 (82–200) | 0.299 |

| Study Center | 0.664 | ||

| Center 1 a | 31 (53.4) | 33 (60.0) | |

| Center 2 b | 15 (25.9) | 14 (25.5) | |

| Center 3 c | 12 (20.7) | 8 (14.5) | |

| Change of α-fetoprotein (%) & | −1.3 (−22.1–39.4) | 12.0 (−18.7–51.6) | 0.346 |

Notes: Categorical data was presented as number (percentage) and quantitative data as median value (Interquartile range). †Sorafenib was as reference. ‡TACE or HAIC without surgery or radical ablation. §Including palliative ablation, radiotherapy, or Iodine 125 seed implantation, without surgery, radical ablation, TACE, or HAIC. aThe Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. bJieyang People’s Hospital. cThe First People’s Hospital of Zhaoqing. &Change of α-fetoprotein = (lowest α-fetoprotein level after treatment – baseline α-fetoprotein level)/baseline α-fetoprotein level × 100%.

Abbreviations: rego-sintilimab, regorafenib combined with sintilimab; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization; HAIC, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

In detail, 36.2% (21/58) of patients in the rego-sintilimab group and 36.4% (20/55) in the regorafenib group had Child-Pugh B liver function (P = 0.986); and 39.7% (23/48) of patients in the rego-sintilimab group and 36.4% (20/35) in the regorafenib group had received lenvatinib as first-line treatment (P = 0.719). The median duration of first-line treatment was 7.3 months (IQR, 4.1–12.0) in the rego-sintilimab group and 7.5 months (IQR, 3.7–14.6) in the regorafenib group (P = 0.508). The mean daily dose of regorafenib was 109.0 mg ± 23.4 in the rego-sintilimab group and 115.6 mg ± 23.9 in the regorafenib group (P = 0.137). The median duration of second-line treatment with rego-sintilimab or regorafenib was 5.7 months (IQR, 3.5–10.1) in the rego-sintilimab group and 4.1 months (IQR, 2.4–7.1) in the regorafenib group.

Safety

Treatment-related AEs are shown in Table 2. No treatment-related mortality occurred. The overall incidence of AEs was similar between the rego-sintilimab group and the regorafenib group (any grade: 93.1% vs 89.1%, P = 0.675; grade 3/4: 39.7% vs 30.9%, P = 0.331). There was a higher incidence of rash of any grade in the rego-sintilimab group compared with the regorafenib group (22.4% vs 7.3%, P = 0.024). Incidences of other AEs were not significantly different between the two groups. AEs of any grade with an incidence over 20% in the rego-sintilimab group included fatigue, hand–foot skin reaction, rash, hypertension, hypothyroidism, hyperbilirubinemia, diarrhea, and anorexia. Grade 3/4 AEs with an incidence over 5% in the rego-sintilimab group included hand–foot skin reaction, hypertension, hyperbilirubinemia, and diarrhea.

Table 2.

Adverse Events in the Two Groups

| Adverse Events | Any Grade | Grade 3 or 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rego-Sintilimab Group (N=58) | Regorafenib Group (N=55) | P value | Rego-sintilimab Group (N=58) |

Regorafenib Group (N=55) | P value | |

| Overall incidence | 54 (93.1) | 49 (89.1) | 0.675 | 23 (39.7) | 17 (30.9) | 0.331 |

| Fatigue | 21 (36.2) | 16 (29.1) | 0.420 | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 0.452 |

| Hand–foot skin reaction | 17 (29.3) | 18 (32.7) | 0.695 | 4 (6.9) | 7 (12.7) | 0.296 |

| Rash | 13 (22.4) | 4 (7.3) | 0.024 | 2 (3.4) | 0 | 0.499 |

| Pneumonitis | 7 (12.1) | 1 (1.8) | 0.079 | 2 (3.4) | 0 | 0.499 |

| Hypertension | 16 (27.6) | 13 (23.6) | 0.631 | 8 (13.8) | 6 (10.9) | 0.642 |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 (22.4) | 8 (14.5) | 0.282 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hyperthyroidism | 5 (8.6) | 2 (3.6) | 0.479 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 13 (22.4) | 11 (20.4) | 0.792 | 4 (6.9) | 2 (3.6) | 0.724 |

| Increased GGT | 6 (10.3) | 5 (9.1) | 0.822 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | >0.999 |

| Increased AST | 11 (19.0) | 8 (14.5) | 0.530 | 2 (3.4) | 3 (5.5) | 0.952 |

| Increased ALT | 7 (12.1) | 5 (9.1) | 0.608 | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | >0.999 |

| Leukopenia | 7 (12.1) | 3 (5.5) | 0.365 | 2 (3.4) | 0 | 0.499 |

| Lymphopenia | 6 (10.3) | 3 (5.5) | 0.540 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Neutropenia | 5 (8.6) | 6 (10.9) | 0.682 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | >0.999 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (10.3) | 5 (9.1) | 0.822 | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | >0.999 |

| Anemia | 7 (12.1) | 3 (5.5) | 0.365 | 1 (1.7) | 0 | >0.999 |

| Proteinuria | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.9) | 0.675 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Increased creatinine | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | >0.999 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Diarrhea | 16 (27.6) | 11 (20.0) | 0.345 | 3 (5.2) | 1 (1.8) | 0.649 |

| Nausea | 6 (10.3) | 6 (10.9) | 0.922 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Anorexia | 15 (25.9) | 13 (23.6) | 0.784 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0.979 |

| Weight loss | 2 (3.4) | 4 (7.3) | 0.627 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Constipation | 4 (6.9) | 3 (5.5) | >0.999 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Presence of ascites | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.963 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 2 (3.4) | 3 (5.5) | 0.952 | 2 (3.4) | 3 (5.5) | 0.952 |

| Gingival bleeding | 4 (6.9) | 6 (10.9) | 0.675 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Epistaxis | 1 (1.7) | 1 (1.8) | >0.999 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Hoarseness | 6 (10.3) | 5 (9.1) | 0.822 | 0 | 0 | — |

| Infusion reaction | 5 (8.6) | — | — | 0 | — | — |

Note: Data are numbers of patients and data in parentheses are percentages.

Abbreviations: rego-sintilimab, regorafenib combined with sintilimab; GGT, γ glutamyltransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

Treatment was discontinued because of AE in 12.1% (7/58) of patients in the rego-sintilimab group and in 9.1% (5/55) in the regorafenib group (P = 0.608). Grade 4 skin toxicity was observed in one patient after two cycles of rego-sintilimab and grade 4 hyperbilirubinemia in one patient with immune-related hepatitis confirmed by liver biopsy after six cycles of rego-sintilimab; both recovered after discontinuation of sintilimab and treatment with glucocorticoid. Another five cases of treatment discontinuation in the rego-sintilimab group were caused by grade 3 AEs, ie rash in two patients, pneumonitis in one patient, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage in two patients.

Treatment Response

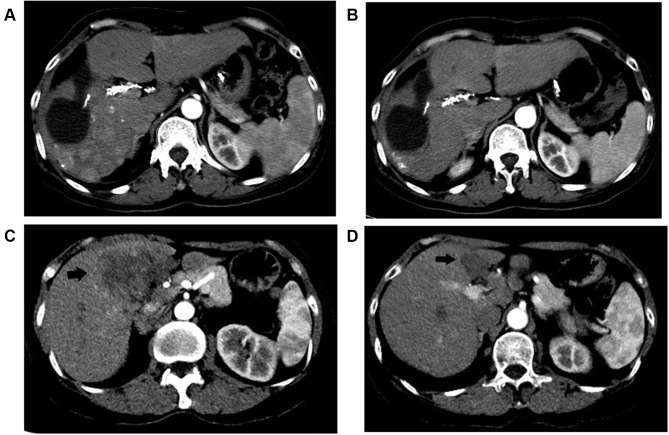

Tumor responses of the two groups are shown in Table 3. Two patients in rego-sintilimab group versus no patients in the regorafenib group showed complete response (Figure 2). The ORR for the rego-sintilimab group was significantly higher than that observed in the regorafenib group (24.1% vs 9.1% by RECIST 1.1, P = 0.033; 36.2% vs 16.4% by mRECIST, P = 0.017). Similarly, the DCR for the rego-sintilimab group was significantly higher than that observed in the regorafenib group (74.1% vs 54.5% by RECIST 1.1, P = 0.029; 74.1% vs 56.4% by mRECIST, P = 0.047).

Table 3.

Treatment Responses

| mRECIST | RECIST 1.1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Response | Rego-Sintilimab Group (N=58) | Regorafenib Group (N=55) | P value | Rego-Sintilimab Group (N=58) | Regorafenib Group (N=55) | P value |

| CR | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PR | 19 | 9 | 14 | 5 | ||

| SD | 22 | 22 | 29 | 25 | ||

| PD | 15 | 24 | 15 | 25 | ||

| ORR, % | 36.2 | 16.4 | 0.017 | 24.1 | 9.1 | 0.033 |

| DCR, % | 74.1 | 56.4 | 0.047 | 74.1 | 54.5 | 0.029 |

Notes: Objective response rate (ORR) = (CR + PR)/N, and disease control rate (DCR) = (CR + PR + SD)/N, where CR is number of patients with complete response, PR is number of patients with partial response, SD is number of patients with stable disease, and N is total number of patients.

Abbreviations: PD, progressive disease; rego-sintilimab, regorafenib combined with sintilimab; RESICT, response evaluation criteria in solid tumors; mRESICT, modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors.

Figure 2.

Two patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who achieved complete response according to modified response evaluation criteria in solid tumors during second-line treatment with regorafenib combined with sintilimab (rego-sintilimab). (A) Case 1, a 52-year-old male who sequentially underwent liver resection, transarterial chemoembolization, and sorafenib treatment. The arterial phase CT image 3 days prior to rego-sintilimab treatment showed multiple HCC nodules in the right liver lobe. (B) Arterial phase CT imaging from case 1 at 17 weeks after initiation of rego-sintilimab showed that enhancement of all HCC nodules in the right liver lobe disappeared. (C) Case 2, a 48-year-old female who sequentially underwent transarterial chemoembolization and sorafenib treatment. The arterial phase CT image 5 days prior to rego-sintilimab treatment showed a large HCC mass with inhomogeneous enhancement at segment 4 (arrow). (D) Arterial phase CT imaging of case 2 at 8 months after initiation of rego-sintilimab showed significant shrinkage and no enhancement of the HCC (arrow).

ROC Curve Analyses

ROC curve analyses for predicting 1-year survival revealed that the optimal cut-off values for NLR, PLR, lymphocytes, and neutrophils were 3.59 (area under the curve [AUC], 0.0719; 95% CI, 0.620–0.818; P <0.001), 190 (AUC, 0.653; 95% CI, 0.547–0.760; P = 0.007), 1.16*109/L (AUC, 0.617; 95% CI, 0.509–0.726; P = 0.041), and 3.16*109/L (AUC, 0.681; 95% CI, 0.575–0.787; P = 0.002), respectively. Thus, these variables were classified into NLR ≤ 3.6 vs NLR > 3.6, PLR ≤ 190 vs PLR >190, lymphocytes ≤ 1.16*109/L vs lymphocytes > 1.16*109/L, and neutrophils ≤ 3.16*109/L vs neutrophils > 3.16*109/L. The AUC for platelets was not statistically significant (AUC, 0.545; 95% CI, 0.433–0.657; P = 0.433), and thus no cut-off value for this variable could be determined using the ROC curve.

Progression-Free Survival

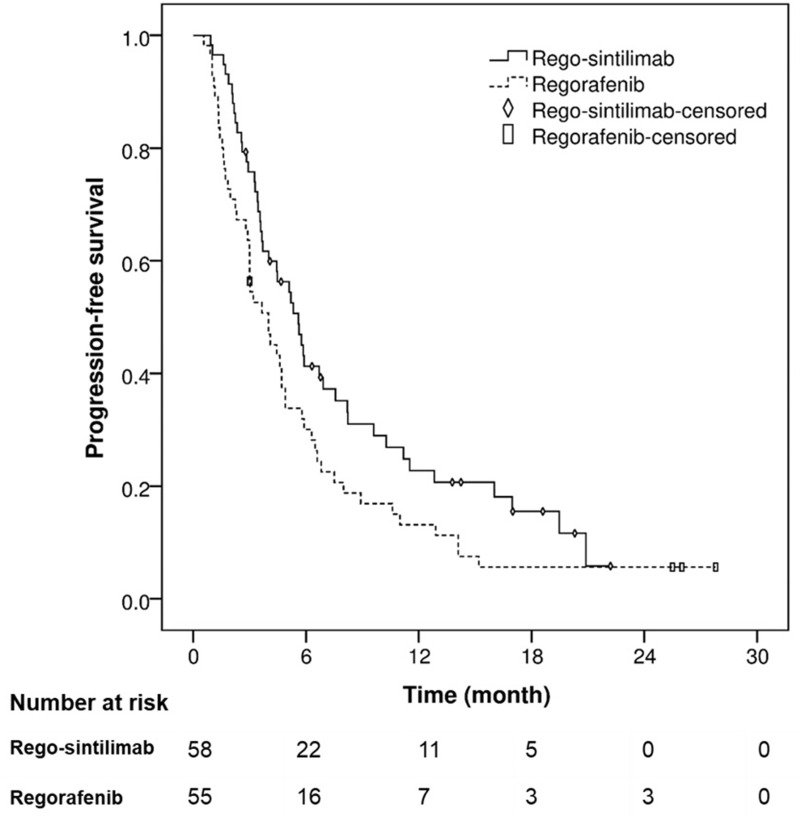

The median follow-up duration was 12.8 months (IQR, 8.0–18.7) for the rego-sintilimab group and 8.3 months (IQR, 5.9–13.0) for the regorafenib group. During follow-up, 47 of 58 (81.0%) patients in the rego-sintilimab group and 51 of 55 (92.7%) patients in the regorafenib group experienced tumor progression. The median PFS in the rego-sintilimab group was 5.6 months (95% CI, 4.2–7.0) compared with 4.0 months (95% CI, 2.5–5.5) in the regorafenib group (P = 0.045) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for progression-free survival (PFS) of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who received regorafenib combined with sintilimab (rego-sintilimab) (median PFS, 5.6 months; 95% CI, 4.2–7.0) or regorafenib (median PFS, 4.0 months; 95% CI, 2.5–5.5; P = 0.045) in a second-line setting.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

According to the univariate and multivariate analyses, regorafenib alone (hazard ratio [HR], 1.499; 95% CI, 1.005–2.237; P = 0.047), α-fetoprotein (HR per 104 ng/mL, 1.047; 95% CI, 1.023–1.070; P < 0.001), and NLR > 3.6 (HR, 1.658; 95% CI, 1.094–2.513; P = 0.017) were independent prognostic factors for PFS (Table 4).

Table 4.

Analyses of Prognostic Factors for Progression-Free Survival

| Factor | Univariable Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Regorafenib alone | 1.495 (1.005–2.225) | 0.047 | 1.499 (1.005–2.237) | 0.047 |

| Female | 1.569 (0.832–2.959) | 0.164 | ||

| >65 years | 0.708 (0.380–1.321) | 0.278 | ||

| ECOG score = 1 | 0.887 (0.592–1.330) | 0.562 | ||

| Positive for HbsAg | 0.642 (0.342–1.205) | 0.168 | ||

| Child-Pugh B | 1.033 (0.681–1.568) | 0.878 | ||

| Presence of ascites | 1.033 (0.659–1.621) | 0.887 | ||

| Tumor diameter (per cm) | 1.005 (0.954–1.058) | 0.863 | ||

| Tumor >5 cm | 1.074 (0.706–1.634) | 0.739 | ||

| >3 intrahepatic tumors | 1.417 (0.893–2.248) | 0.139 | ||

| Macrovascular invasion | 0.920 (0.608–1.393) | 0.694 | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 1.366 (0.909–2.054) | 0.133 | ||

| First-line treatment with lenvatinib | 0.771 (0.510–1.165) | 0.217 | ||

| Time on first-line treatment (per month) | 1.009 (0.997–1.021) | 0.156 | ||

| Previous surgery or ablation | 0.975 (0.618–1.540) | 0.914 | ||

| α-fetoprotein (per 104 ng/mL) | 1.050 (1.027–1.074) | < 0.001 | 1.047 (1.023–1.070) | < 0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase >50 U/L | 1.130 (0.708–1.804) | 0.609 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase >40 U/L | 1.229 (0.822–1.837) | 0.315 | ||

| Total bilirubin >22 μmol/L | 1.160 (0.734–1.836) | 0.525 | ||

| Albumin <35 g/dL | 0.955 (0.641–1.421) | 0.819 | ||

| Lymphocyte <1.16*109/L | 1.482 (0.969–2.265) | 0.069 | 0.351 | |

| Neutrophils >3.16*109/L | 1.330 (0.887–1.995) | 0.168 | ||

| Platelet of 100–200*109/L | Ref | |||

| Platelet <100*109/L | 0.844 (0.499–1.425) | 0.525 | ||

| Platelet >200*109/L | 0.909 (0.517–1.599) | 0.740 | ||

| NLR >3.6 | 1.844 (1.229–2.765) | 0.003 | 1.658 (1.094–2.513) | 0.017 |

| PLR >190 | 1.629 (1.049–2.530) | 0.030 | 0.294 | |

| Study Center 1 a | Ref | |||

| Study Center 2 b | 0.960 (0.598–1.543) | 0.867 | ||

| Study Center 3 c | 1.136 (0.666–1.935) | 0.640 | ||

Notes: The uni- and multi-variate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression model. aThe Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. bJieyang People’s Hospital. cThe First People’s Hospital of Zhaoqing.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

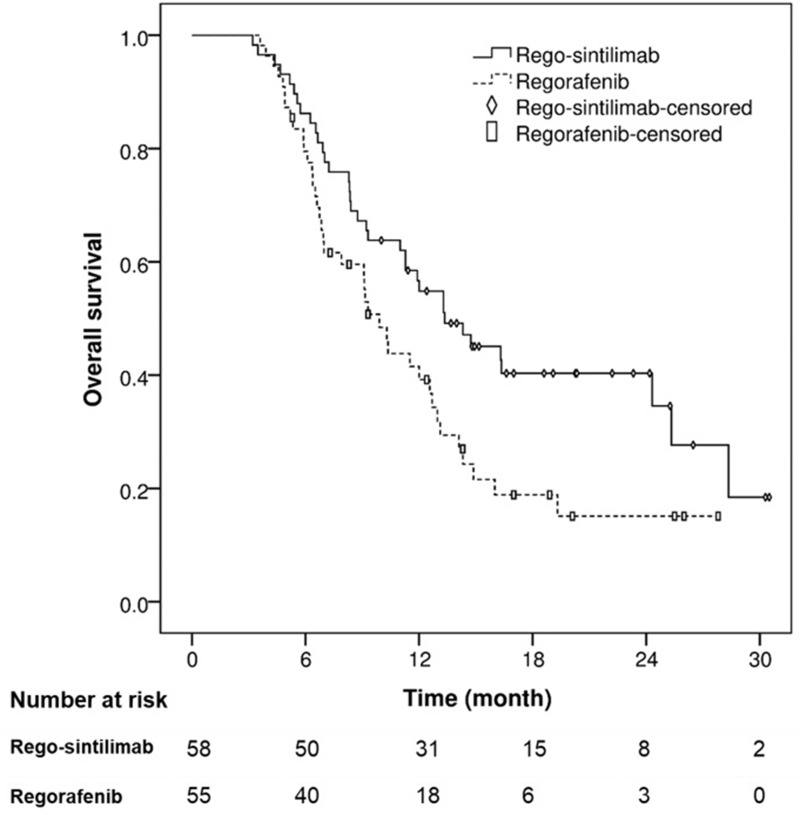

Overall Survival

During the follow-up period, 36 of 58 (62.1%) patients in the rego-sintilimab group and 39 of 55 (70.9%) patients in the regorafenib group died. The 6-, 12-, and 24-month OS rates were 86.2%, 54.8%, and 40.3% (median OS, 13.4 months [95% CI, 9.2–17.5]), respectively, in the rego-sintilimab group, and 79.5%, 39.2%, and 15.1% (median OS, 9.9 months [95% CI, 8.3–11.5]), respectively, in the regorafenib group (P = 0.023) (Figure 4). According to the univariate and multivariate analyses, regorafenib alone (HR, 1.630; 95% CI, 1.031–2.578; P = 0.037), Child-Pugh B liver function (HR, 1.595; 95% CI, 1.002–2.540; P = 0.049), and NLR > 3.6 (HR, 1.897; 95% CI, 1.075–3.348; P = 0.027) were independent prognostic factors for OS (Table 5).

Figure 4.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival (OS) of patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma who received regorafenib combined with sintilimab (rego-sintilimab) (median OS, 13.4 months; 95% CI, 9.2–17.5) or regorafenib (median OS, 9.9 months; 95% CI, 8.3–11.5; P = 0.023) in a second-line setting.

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Table 5.

Analyses of Prognostic Factors for Overall Survival

| Factor | Univariable Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P value | HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Regorafenib alone | 1.690 (1.069–2.670) | 0.025 | 1.630 (1.031–2.578) | 0.037 |

| Female | 1.284 (0.658–2.505) | 0.463 | ||

| >65 years | 0.746 (0.338–1.647) | 0.468 | ||

| ECOG score = 1 | 1.592 (1.009–2.514) | 0.046 | 0.160 | |

| Positive for HbsAg | 0.631 (0.303–1.317) | 0.220 | ||

| Child-Pugh B | 1.661 (1.044–2.642) | 0.032 | 1.595 (1.002–2.540) | 0.049 |

| Presence of ascites | 0.968 (0.574–1.632) | 0.902 | ||

| Tumor diameter (per cm) | 1.034 (0.972–1.100) | 0.288 | ||

| Tumor >5 cm | 1.215 (0.747–1.974) | 0.433 | ||

| >3 intrahepatic tumors | 1.703 (0.978–2.965) | 0.060 | 0.257 | |

| Macrovascular invasion | 1.149 (0.713–1.850) | 0.569 | ||

| Extrahepatic metastasis | 1.326 (0.819–2.147) | 0.251 | ||

| First-line treatment with lenvatinib | 0.883 (0.555–1.405) | 0.600 | ||

| Time on first-line treatment (per month) | 0.996 (0.981–1.012) | 0.626 | ||

| Previous surgery or ablation | 0.713 (0.404–1.257) | 0.243 | ||

| α-fetoprotein (per 104 ng/mL) | 1.020 (1.000–1.040) | 0.045 | 0.223 | |

| Alanine aminotransferase >50 U/L | 1.520 (0.917–2.519) | 0.105 | ||

| Aspartate aminotransferase >40 U/L | 2.039 (1.262–3.295) | 0.004 | 0.116 | |

| Total bilirubin >22 μmol/L | 1.555 (0.941–2.571) | 0.085 | 0.243 | |

| Albumin <35 g/dL | 1.371 (0.869–2.161) | 0.175 | ||

| Lymphocyte <1.16*109/L | 1.975 (1.168–3.341) | 0.011 | 0.165 | |

| Neutrophils >3.16*109/L | 2.278 (1.442–3.599) | < 0.001 | 0.066 | |

| Platelet of 100–200*109/L | Ref | |||

| Platelet <100*109/L | 1.226 (0.700–2.147) | 0.477 | 0.682 | |

| Platelet >200*109/L | 1.321 (0.723–2.413) | 0.365 | 0.624 | |

| NLR >3.6 | 2.610 (1.641–4.150) | < 0.001 | 1.897 (1.075–3.348) | 0.027 |

| PLR >190 | 2.360 (1.476–3.773) | < 0.001 | 0.133 | |

| Study Center 1 a | Ref | |||

| Study Center 2 b | 0.684 (0.375–1.246) | 0.214 | ||

| Study Center 3 c | 1.141 (0.636–2.048) | 0.659 | ||

Notes: The uni- and multi-variate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazard regression model. aThe Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. bJieyang People’s Hospital. cThe First People’s Hospital of Zhaoqing.

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; PIVKA-II, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

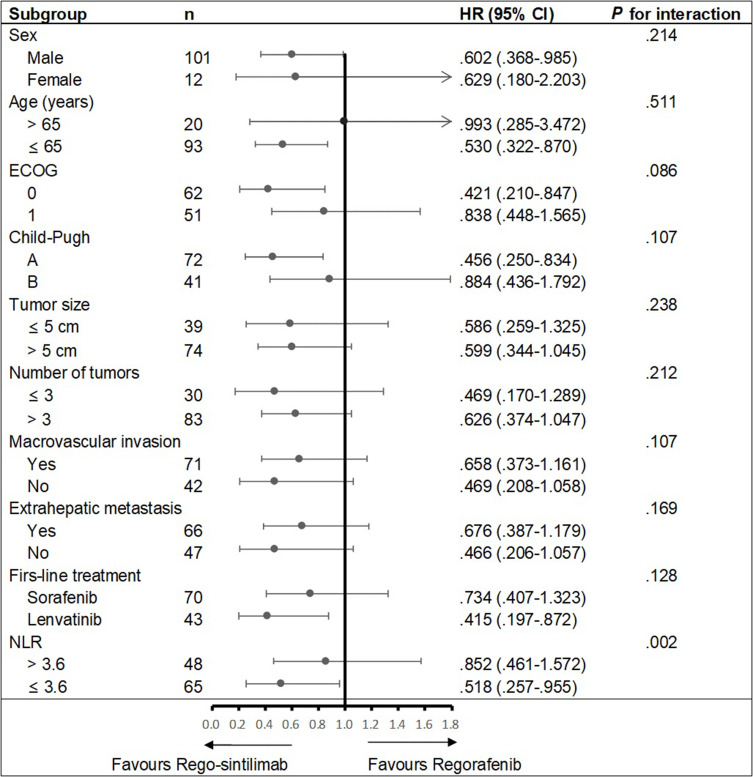

Subgroup analyses according to different variables were conducted to compare the risk of death between rego-sintilimab and regorafenib (Figure 5). A trend of lower risk of death for rego-sintilimab over regorafenib was shown in all the subgroups. Rego-sintilimab reduced risk of death, with benefit only seen in patients with NLR ≤ 3.6 (HR, 0.518 [95% CI, 0.257–0.955]) but not in those with NLR > 3.6 (0.852 [0.461–1.572], P = 0.002 for interaction). It also seemed that rego-sintilimab reduced death more in patients with ECOG score 0 (0.421 [0.210–0.847]) or Child-Pugh A liver function (0.456 [0.250–0.834]) than in those with ECOG score 1 (0.838 [0.448–1.565]) or Child-Pugh B liver function (0.884 [0.436–1.792]), but the interaction between treatment method and ECOG score or Child-Pugh class was not statistically significant (P = 0.086 and P = 0.107 for the interactions, respectively). There was no statistically significant interaction between treatment method and other subgroups (P > 0.05 for all interactions).

Figure 5.

Subgroup analyses according to different variables for comparing overall survival between regorafenib combined with sintilimab (rego-sintilimab) and regorafenib. A trend of better survival benefit for rego-sintilimab over regorafenib was observed in all the subgroups. Rego-sintilimab reduced risk of death, with benefit only seen in patients with neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) ≤ 3.6 (HR, 0.518 [95% CI, 0.257–0.955]), not in those with NLR > 3.6 (0.852 [0.461–1.572]; P = 0.002 for interaction). There was no statistically significant interaction between the treatment method and other subgroups (P > 0.05 for all interactions).

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Discussion

Our study showed that rego-sintilimab conferred a significant survival benefit when compared with regorafenib in a second-line setting in patients with advanced HCC in whom prior sorafenib or lenvatinib treatment had failed. This finding was associated with an increase in median OS from 9.9 months to 13.4 months. In the multivariate analyses, combination with anti-PD-1 antibody sintilimab was an independent predictor for better OS and PFS. This survival benefit may be attributed to a higher ORR and DCR and a longer PFS in patients who received rego-sintilimab compared to those who received regorafenib alone. A recent phase 1b trial investigated regorafenib combined with anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab in first-line treatment of HCC and showed a promising ORR of 28% by RECIST 1.1;12 by comparison, the ORR by RECIST 1.1 in the rego-sintilimab group in our study was 24.1% in a second-line setting. These results indicate that rego-sintilimab has an advantage over regorafenib alone: regorafenib potently inhibits JAK1/2-STAT1 and MAPK signaling and subsequently attenuates PD-L1 expression in tumors,22 and increases intratumoral CD8+ T-cell infiltration through vasculature normalization by targeting VEGFR2/3,13 which probably improves the efficacy of anti-PD-1 antibody. However, a randomized controlled trial formally assessing the efficacy and safety of rego-sintilimab needs to be conducted prior to using this combination as a standard second-line treatment for HCC.

The median OS in the regorafenib group was 9.9 months, slightly poorer than the median OS of 10.3–12.1 months for second-line regorafenib treatment reported by previous studies.4,23,24 It is worth noting that these studies included only patients with Child-Pugh A liver function, whereas about 35% of patients in our study had Child-Pugh B HCC. The OS of Child-Pugh B patients with regorafenib treatment was reported to be significantly poorer than that of Child-Pugh A cohort in a multicenter study,25 consistent with the results of our study. Nonetheless, an effective treatment is still required for Child-Pugh B patients. Casadei’s study showed that 35% of patients who had Child-Pugh A HCC before sorafenib treatment might experience liver function deterioration to Child-Pugh B when sorafenib ceased.26 The latest phase I/II study by Kudo et al27 showed that immune checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy had favorable safety for patients with Child-Pugh B HCC, comparable to that seen in Child-Pugh A patients. In our subgroup analyses, it seemed that rego-sintilimab reduced death more in patients with Child-Pugh A liver function than in those with Child-Pugh B liver function, but the interaction between treatment method and Child-Pugh class was not statistically significant. Whether patients with Child-Pugh B liver function could benefit from the combination of regorafenib and anti-PD-1 antibody needs further study.

An effective prognostic biomarker for immunotherapy in HCC patients is currently lacking and urgently needed.28 NLR is an easily accessed and widely available blood-based clinical biomarker. A lower NLR may delineate a healthy host immune anti-tumor response29 and was an independent predictor for PFS and OS in our study. Its clinical relevance is thought to be because an elevated peripheral neutrophil count is a marker of chronic inflammation, which often leads to impaired immunity,30 whereas the peripheral lymphocyte count is a hallmark of a healthy cytotoxic T-cell response.31 In our subgroup analyses, rego-sintilimab conferred a survival benefit only in patients with NLR ≤ 3.6, not in those with NLR > 3.6. This result may help to select patients suitable for second-line treatment with rego-sintilimab.

The safety profile of rego-sintilimab was generally consistent with historical data on regorafenib4 and sintilimab,14 with no new AEs reported. The combination with sintilimab did not increase the overall incidence of any grade or grade 3/4 AEs compared with regorafenib treatment. Treatment was discontinued in 12.1% of patients in the rego-sintilimab group because of AEs, similar to the incidence previously reported with sintilimab–bevacizumab biosimilar treatment (14%).14

This study had several limitations. First, as a retrospective study, the comparison of rego-sintilimab and regorafenib may be subject to selection bias, and no matched pair analysis between the two groups was performed because of a small sample size. Instead, we conducted multivariate analyses and subgroup analyses to correct for confounding factors. Second, the sample size in this study was relatively small. Results of the subgroup analyses should be cautiously interpreted, and validation by further studies is needed. Third, different baseline NLR cut-off values were used in different studies (range 1.9–5.0).32 This heterogeneity could hinder the application of NLR in clinical settings. Thus, large cohort studies are required to establish the most appropriate NLR cut-off value in HCC patients undergoing immunotherapy.

In conclusion, rego-sintilimab was tolerated and yielded promising outcomes in a second-line setting for patients with advanced HCC. These patients appeared to benefit from rego-sintilimab and showed better treatment responses, PFS, and OS in comparison with those treated with regorafenib alone, especially in those who had an NLR ≤ 3.6.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 82001930, 81873920, and 81801809), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (Grant No. 202002030135), and High-Level University Clinical Research Promotion Program of Guangzhou Medical University (No. B185004019).

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, et al.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al.; SHARP Investigators Study Group. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised Phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–1173. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al.; RESORCE Investigators. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng AL, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced and progressing hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(1):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1717002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhu AX, Kang YK, Yen CJ, et al.; REACH-2 study investigators. Ramucirumab after sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and increased α-fetoprotein concentrations (REACH-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(2):282–296. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30937-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Yang X, Lin J, et al. Comparing the efficacy and safety of second-line therapies for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a network meta-analysis of Phase III trials. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820932483. doi: 10.1177/1756284820932483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu AX, Finn RS, Edeline J, et al.; KEYNOTE-224 investigators. Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib (KEYNOTE-224): a non-randomised, open-label Phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(7):940–952. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30351-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finn RS, Ryoo BY, Merle P, et al.; KEYNOTE-240 investigators. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma in KEYNOTE-240: a randomized, double-blind, phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(3):193–202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.01307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangaru S, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Review article: new therapeutic interventions for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(1):78–89. doi: 10.1111/apt.15573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Khoueiry AB, Kim RD, Harris WP, et al. Updated results of a phase 1b study of regorafenib (REG) 80 mg/day or 120 mg/day plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) for first-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_suppl):4078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2021.39.15_suppl.4078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shigeta K, Matsui A, Kikuchi H, et al. Regorafenib combined with PD1 blockade increases CD8 T-cell infiltration by inducing CXCL10 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8(2):e001435. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren Z, Xu J, Bai Y, et al. ORIENT-32 study group. Sintilimab plus a bevacizumab biosimilar (IBI305) versus sorafenib in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (ORIENT-32): a randomised, open-label, phase 2–3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):977–990. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00252-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brahmer JR, Drake CG, Wollner I, et al. Phase I study of single-agent anti-programmed death-1 (MDX-1106) in refractory solid tumors: safety, clinical activity, pharmacodynamics, and immunologic correlates. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3167–3175. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Fei K, Jing H, et al. Durable blockade of PD-1 signaling links preclinical efficacy of sintilimab to its clinical benefit. MAbs. 2019;11(8):1443–1451. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2019.1654303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrero JA, Kulik LM, Sirlin CB, et al. Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma: 2018 practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68(2):723–750. doi: 10.1002/hep.29913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suner A, Carr BI. Platelet-to-lymphocyte and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios predict tumor size and survival in HCC patients: retrospective study. Ann Med Surg. 2020;58:167–171. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.08.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Cancer Institute. Common terminology criteria for adverse events, version 5.0; November 27, 2017. Available from: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocolDevelopment/electronic_applications/ctc.htm#ctc_50. Accessed December 16, 2020.

- 20.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lencioni R, Llovet JM. Modified RECIST (mRECIST) assessment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2010;30(1):52–60. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu RY, Kong PF, Xia LP, et al. Regorafenib promotes antitumor immunity via inhibiting PD-L1 and IDO1 expression in melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25(14):4530–4541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-2840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekir Hacioglu M, Kostek O, Karabulut S, et al. Efficacy of regorafenib in the second-and third-line setting for patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a real life data of multicenter study from Turkey. J BUON. 2020;25(4):1897–1903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoo C, Byeon S, Bang Y, et al. Regorafenib in previously treated advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of prior immunotherapy and adverse events. Liver Int. 2020;40(9):2263–2271. doi: 10.1111/liv.14496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim HD, Bang Y, Lee MA, et al. Regorafenib in patients with advanced Child-Pugh B hepatocellular carcinoma: a multicentre retrospective study. Liver Int. 2020;40(10):2544–2552. doi: 10.1111/liv.14573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casadei Gardini A, Frassineti GL, Foschi FG, et al. Sorafenib and Regorafenib in HBV- or HCV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma patients: analysis of RESORCE and SHARP trials. Dig Liver Dis. 2017;49(8):943–944. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kudo M, Matilla A, Santoro A, et al. CheckMate 040 cohort 5: a phase I/II study of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(3):600–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.D’Alessio A, Cammarota A, Prete MG, et al. The evolving treatment paradigm of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: putting all the pieces back together. Curr Opin Oncol. 2021;33(4):386–394. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ameratunga M, Chénard-Poirier M, Moreno Candilejo I, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio kinetics in patients with advanced solid tumours on phase I trials of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2018;89:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumitru CA, Moses K, Trellakis S, et al. Neutrophils and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells: immunophenotyping, cell biology and clinical relevance in human oncology. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61(8):1155–1167. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1294-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai S, Abouljoud MS, Kazimi M, et al. Peritransplant lymphopenia is a novel prognostic factor in recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;97(6):694–701. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000437426.15890.1d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiao WK, Chen D, Li SQ, et al. Prognostic significance of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]