ABSTRACT.

We test the safety of fluoxetine post-ischemic stroke in sub-Saharan Africa. Adults with acute ischemic stroke, seen <14 days since new-onset motor deficits, were enrolled from November 2019 to October 2020 in a single-arm, open-label phase II trial of daily fluoxetine 20 mg for 90 days at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. The primary outcome was safety with secondary outcomes of medication adherence and tolerability. Thirty-four patients were enrolled (11 were female; mean age 52.2 years, 65% < 60 years old; mean 3.3 days since symptom onset). Participants had hypertension (74%), diabetes (18%), and smoked cigarettes (18%). The median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score at enrollment was 10.5. The median Fugl-Meyer Motor Scale score was 28.5 (upper extremity 8, lower extremity 17.5). 32/34 participants (91%) survived to 90 days. There were eight serious and two nonserious adverse events. Deaths occurred due to gastrointestinal illness with low serum sodium (nadir 120 mmol/L) with seizure and gastrointestinal bleed from gastric cancer. The average sodium level at 90 days was 139 mmol/L (range 133–146) and alanine transaminase was 28 U/L (range 10–134). Fluoxetine adherence was 96%. The median modified Rankin Scale score among survivors at 90 days was 2 and Fugl-Meyer Motor Scale score was 66 (upper extremity 40, lower extremity 27). Median 90-day Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Montgomery-Åsberg scores were 3.5 and 4 (minimal depression). Fluoxetine administration for 90 days poststroke in sub-Saharan Africa was generally safe and well-tolerated, but comorbid illness presentations were fatal in 2/34 cases, even after careful participant selection.

INTRODUCTION

Stroke has reached epidemic proportions in sub-Saharan Africa, where it is now a leading cause of death and disability. Limited research on poststroke disability has occurred in sub-Saharan African populations; however, these populations could especially benefit from therapeutic advances in poststroke recovery, particularly interventions that are cost-effective, available, and administrable by non-neurologist providers. Poststroke depression is also an under-recognized condition in sub-Saharan Africa. Risk factors for poststroke depression may parallel risk factors for poststroke motor disability but also extend to other psychosocial factors including social support, employment, and income.1–3 Poststroke rehabilitation is a nascent field globally. Limited poststroke clinics, research, and mental health professionals exist to take on this increasing number of patients in most settings. Many stroke patients exhaust their personal resources during the acute event, leaving limited options to pay for recurring poststroke care visits in resource-limited settings. To fully address the mood, disability, and other impacts of being a stroke survivor, much more work is needed at the policy and scientific levels to improve the situation for patients and clinicians with limited resources.

Fluoxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), is used to treat depression worldwide and may improve motor recovery after an acute ischemic stroke. In 118 adults in the FLAME trial4 in France, fluoxetine was found to improve motor recovery on the Fugl-Meyer Motor Scale (FMMS) score and lessen depression poststroke. There were few safety concerns and excellent tolerability. FLAME participants had an average age of 66 years, an average National Institutes of Health (NIH) stroke scale (NIHSS) score of 13 at onset in the fluoxetine-treated arm, a predominance of male participants (∼60%), a poststroke fatality of < 3%, and no report on race.

Since that time, several large-scale pragmatic trials have emerged. In 2018, FOCUS5 reported the administration of fluoxetine after acute ischemic stroke in > 3,000 patients in the United Kingdom, finding no beneficial impact of fluoxetine on modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at 90 days. An increase in bone fractures was reported. The EFFECTS6 and AFFINITY7 trials followed, finding mixed impact of fluoxetine on poststroke depression,8 increased safety risks with daily poststroke fluoxetine use, but no major impact on the mRS score at 6 months poststroke.

To date, no study has focused on fluoxetine’s potential to impact stroke outcomes for individuals living in Africa. However, fluoxetine could have significant impact in stroke survivors in low-income countries with its widespread availability, listing on the WHO’s Essential Medicines Lists, familiarity to prescribers through use in common psychiatric disorders, and low cost (∼0.10USD per pill). We report a single-group, open-label phase II trial, called Measuring Ambulation, Motor, and Behavioral Outcomes (MAMBO), of fluoxetine in urban Tanzania.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Approvals.

Approvals were granted from the Muhimbili National Hospital Ethical Review Board (MNH/IRB/1/2018/191), National Institute for Medical Research of Tanzania (NMIR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/2272), Tanzanian Food and Drugs Authority (TZ19CT0012), and Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board (2018P002441) (clinicaltrials.gov [NCT03728153]). Each participant, or when necessary, next of kin, provided written, informed consent in Kiswahili or English. A copy of our participant consent form in English is provided in the supplemental materials.

Location.

Muhimbili National Hospital is a tertiary referral hospital in Dar es Salaam with ∼50 inpatient neurology beds. Patients with stroke are self-referred, transferred from clinics, or referred from hospitals throughout Tanzania. Services on the neurology ward are minimal with a mixture of out-of-pocket payments and basic supplies provided through insurance and the hospital. There is scant use of thrombolysis; however, stroke services are growing in Tanzania, with plans for additional expertise and resources to be invested in the near future. Most patients have access to a head computed tomography (CT) before admission to the neurology ward.

Study procedures.

A phase II, single-center, single-group, and open-label study of fluoxetine 20 mg orally daily was modeled after the phase III FLAME study.4 MAMBO emphasized safety as the primary outcome with secondary endpoints of fluoxetine tolerability and adherence. Safety focused on clinical adverse events with scheduled laboratory testing of serum sodium and liver enzymes with at least an alanine transaminase (ALT) reported at Muhimbili Hospital laboratories at 30, 60, and 90 days post enrollment. Study eligibility criteria accounted for factors that were known to be associated with fatal outcomes at 90 days in Tanzania based on prior observational cohort work at Muhimbili National Hospital.9 Inclusion criteria were age ≥ 18 and < 80 years; symptomatic onset of acute ischemic stroke < 14 days before enrollment; upper and/or lower extremity motor weakness; and CT-confirmed ischemic stroke. Exclusion criteria were NIHSS > 20, unconscious at presentation, current antidepressant or psychoactive drug use, current pregnancy, recent head trauma, motor deficits attributable to non-stroke etiologies, moribund and unlikely to survive to 90 days, hemorrhagic conversion of ischemic infarct, dysphagia preventing pill swallowing, CT-confirmed hemorrhagic stroke, renal impairment (creatinine > 180 micromol/L or glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/minute/1.73m2), transient ischemic symptoms, hyponatremia (< 125 mmol/L), and/or hepatic impairment (serum ALT > 120 units/L).

All clinical study staff were trained and certified in the NIHSS. The study physical therapist and selected study physicians were trained in the administration of the FMMS scoring, using both online and in-person instruction.

Participants were reimbursed 515,000 Tanzanian shillings (approximately 220 USD) allotted over the study visits.

Study drug.

Fluoxetine was procured through the University of Iowa Pharmacy laboratory using strict clean room packing procedures and hand-carried to Tanzania with 90 tablets in each pill bottle. The fluoxetine was stored with all necessary temperature and quality control requirements by the lead hospital pharmacist and distributed to each participant upon enrollment with safe storage instructions. The drug came as 20 mg tablets, necessitating one tablet per day.

Baseline evaluations and neuroimaging.

Baseline measurements included an enrollment interview, NIHSS,10 upper and lower extremity FMMS scores,11 mRS score,12 Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA),13 and the Identification and Intervention for Dementia in Elderly Africans (IDEA) scale.14 The IDEA cognitive assessment is validated in Tanzania15 and includes recall, frontal lobe functioning, verbal fluency, abstract reasoning, praxis, and memory.

The FMMS is a stroke-specific, performance-based index of motor impairment. Possible scores range from 0 to 100 with weighting of 2/3 for the upper extremity subscale and 1/3 for the lower extremity subscale.

Hand grip strength was measured using a dynamometer (Baseline 12-0241 Lite Hand 200 lbs.). Participants underwent laboratory (serum sodium and ALT) testing at the baseline visit.

Head CT was interpreted by a radiologist, a neurologist, and study investigators in Tanzania. Whenever possible, a brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (3-Tesla, Siemens) was used to confirm the diagnosis of stroke, although a brain MRI was not required for enrollment. Images were later reviewed by a neurologist and neuroradiologist at the Massachusetts General Hospital.

All participants received usual care at Muhimbili National Hospital, including management of poststroke comorbidities. Rehabilitation and physical therapy are not standard for inpatients and remain difficult to obtain poststroke.

Follow-up evaluations.

Participants were requested to return at 30, 60, and 90 days in person. At each visit, remaining pills were counted as a medication possession ratio (MPR). An mRS score was assessed and laboratory tests drawn. At the 90-day visit, additional tests included FMMS, MoCA, IDEA, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),16 Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale,17 and the Stroke Impact Scale (SIS). The SIS18 is a self-reported questionnaire that assesses health-related quality of life poststroke (ranges 0–100).

Outcomes.

Safety was evaluated by the number of reported adverse clinical events and data from laboratory tests (serum sodium and ALT levels) at the prespecified study endpoints. Participants and family members were advised to call the study project lead in Tanzania with any new symptoms or event. Adverse events were recorded by the study team upon notification. Participants were also asked about adverse events at 30, 60, and 90 days and telephoned with reminders throughout the study period. Adverse events were categorized as 1) serious or nonserious, and 2) related, possibly related, unlikely related, or unrelated by at least one study neurologist from United States and Tanzania.

Secondary outcomes were 1) fluoxetine adherence measured by the MPR, and 2) tolerability measured as the number of participants who discontinued because of adverse events. Additional outcomes of interest included 1) the change in poststroke motor impairment from baseline to 90 days on the FMMS and 2) the depressive symptom burden at 90 days measured by the PHQ-9 and the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

A poststroke mortality of approximately 30% at 90 days was anticipated.19,20 The trial was predetermined to be feasible if > 50% of the participants took 80% of their fluoxetine and were evaluable at 90 days. MAMBO stopped recruitment in October 2020 due to two unanticipated situations: 1) COVID-19 including the death of a participant from COVID-19, and 2) release of the EFFECTS and AFFINITY trials reporting no measurable beneficial effect on mRS with poststroke fluoxetine at 6 months, and an increased risk of bone fractures and hyponatremia (EFFECTS) and seizures (AFFINITY).

Analysis.

An intention to treat analysis was performed. Variables were described by their means, SDs, medians, and ranges as appropriate. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The number of adverse events were counted and are provided as a proportion of study participants.

RESULTS

About 34 participants enrolled (November 2019–October 2020) with mean age at ischemic stroke symptomatic onset 52.2 years, range 21–76; 65% < 60 years old, all African black; 11 women. The mean time to enrollment from stroke symptom onset was 3.3 days (SD = 2.3). The average number of hours from stroke symptom onset to first presentation to a health facility was 8 hours (range 0.33–48; median 3). Inpatient enrollment was the most common (94%, N = 32). Participants received oral aspirin upon stroke presentation but not thrombolysis. One started warfarin. Only hypertension was present in most participants (Table 1). No participant had HIV/AIDS.

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics

| Female | Male | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (% of full sample) | 11 (32) | 23 (68) | 34 (100) |

| Age, n(%) | |||

| < 40 years | 0 | 5 (22) | 5 (15) |

| 40–49 years | 3 (27) | 3 (13) | 6 (18) |

| 50–59 years | 5 (45) | 6 (26) | 11 (32) |

| ≥ 60 years | 3 (27) | 9 (39) | 12 (35) |

| Days from symptom onset to enrollment, median (range) | 3 (1–12) | 3 (1–6) | 3 (1–12) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 7 (64) | 12 (52) | 19 (56) |

| Some secondary school | 3 (27) | 1 (4) | 4 (12) |

| Complete secondary | 1 (9) | 7 (30) | 8 (24) |

| University | 0 | 2 (9) | 2 (6) |

| Medical history, n (%) | |||

| Any alcohol intake | 0 | 5 (22) | 5 (15) |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | 1 (9) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Depression | 1 (9) | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 5 (45) | 1 (4) | 6 (18) |

| Dyslipidemia | 1 (9) | 1 (4) | 2 (6) |

| Family history of stroke | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Hypertension | 11 (100) | 14 (61) | 25 (74) |

| Transient ischemic attack | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Cigarette smoking | 0 | 6 (26) | 6 (18) |

| Examination findings, n (%) | |||

| Altered level of consciousness | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (3) |

| Aphasia/language disturbance | 2 (18) | 10 (43) | 12 (35) |

| Decreased sensation | 4 (36) | 9 (39) | 13 (38) |

| Dysarthria | 2 (18) | 4 (17) | 6 (18) |

| Weakness/paresis | 11 (100) | 23 (100) | 34 (100) |

| Vision disturbance | 2 (18) | 3 (13) | 5 (15) |

| Medication administered at hospital, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 10 (91) | 20 (87) | 30 (88) |

| Blood pressure at presentation to hospital, mean (mm of Hg; SD) | |||

| Systolic | 175 (24) | 162 (28) | 165 (27) |

| Diastolic | 108 (27) | 94 (22) | 98 (24) |

| BMI, mean(kg/m2; SD) | 33.4 | 25.1 | 27.2 |

| BMI > 30, n | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Laboratory data, mean (SD) | |||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 99.4 (30.8) | 102.1 (31.85) | 101.2 (31.1) |

| Cholesterol (total; mmol/L) | 5.8 (1.4) | 4.8 (1.2) | 5.2 (1.3) |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.5 (0.4) | 1.4 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.5) |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.1 (0.2) | 1.2 (0.3) |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 3.9 (1.6) | 5.6 (9.2) | 5.0 (7.2) |

| NIH Stroke Scale score, mean (SD) | 9.5 (3.7) | 10.5 (5.0) | 10.1 (4.6) |

| Dynamometer grip strength for affected upper extremity, mean (kg; SD) | 6.0 (6.5) | 3.1 (7.9) | 2.93 (6.0) |

BMI = body mass index; HDL = high-density lipoprotein; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

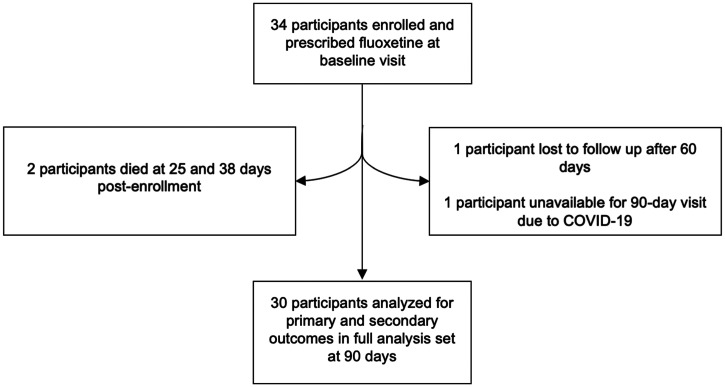

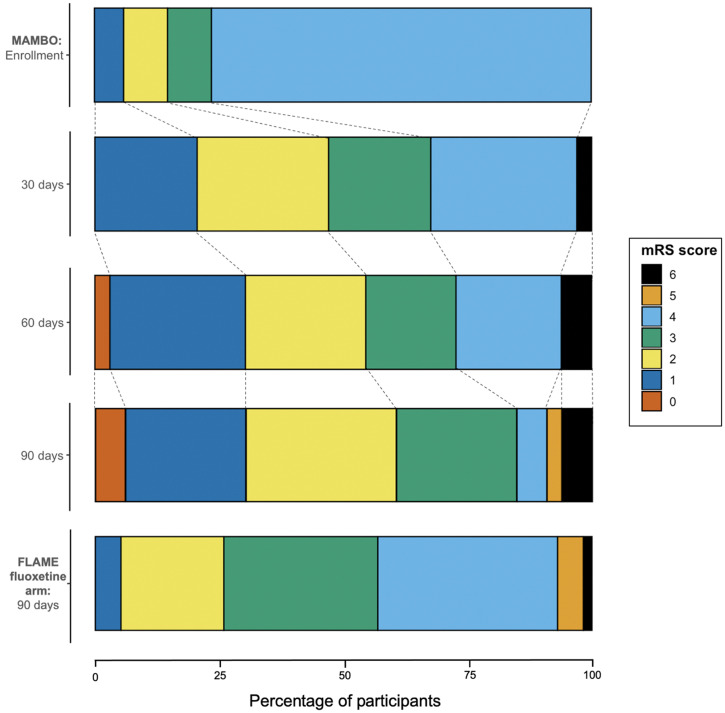

There were two participants with incomplete follow-up (Figure 1). One participant migrated after 60 days and discontinued fluoxetine but survived past 90 days. One participant died of COVID-19 at 101 days post enrollment (i.e., after the planned study period) but missed the 90-day visit due to illness. Figure 2 shows the mRS scores of MAMBO versus FLAME’s fluoxetine-treated participants at 90 days.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of MAMBO participants.

Figure 2.

Participants’ modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores at scheduled post enrollment follow-up compared with 90-day FLAME fluoxetine scores. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

Adverse events.

There were 10 adverse events including 8 serious and 2 nonserious adverse events (Table 2). Of two deaths, one was unrelated and one was possibly related to fluoxetine.

Table 2.

Participant safety outcomes

| Adverse event severity* | Event related to fluoxetine use† | Demographic information | Safety event | Number of days post-fluoxetine initiation | Number of days poststroke | Comorbidities | Concomitant medications | Fluoxetine discontinued due to event | Event outcome | 90-day mRS outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious | Possible | 62 M(A) | Intermittent emesis and decreased appetite, hyponatremia serum Na+ = 120 mmol/L | 25 | 27 | EtOH HTN | Amlodipine Atorvastatin Clopidogrel Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan Unknown medication | Suspended for 9 days | No resolution of symptoms, death | 6 |

| 62 M(B) | Abnormal laboratory results, ALT = 91 U/L, K+ = 2.7 mEq/L, serum Na+ = 139 mmol/L | 90 | 94 | HTN | Amlodipine Aspirin Atorvastatin Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan | Yes | Study completed, fluoxetine discontinued | 3 | ||

| Unlikely | 42 F | Confusion, dizziness, weakness, transient aphasia | 63 | 64 | HTN | Aspirin Atorvastatin Bisoprolol Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan Pantoprazole | No | Readmitted, diagnosed with TIA | 0 | |

| 50 M | Right supranuclear facial palsy, left hemiparesis | 87 | 88 | None reported | Aspirin Atorvastatin | Yes | MRI revealed acute infarct involving R MCA territory, possible seizure, prescribed carbamazepine | 2 | ||

| Unrelated | 51 F | Cardiac arrest | 7 | 8 | Diabetes HTN | Aspirin Atorvastatin Bisoprolol Glimepiride Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan | Suspended for 26 days | Extubated and discharged, fully recovered | 2 | |

| 32 M | Pneumonia, severe malaria, anemia, worm infestation, and urinary tract infection | 62 | 75 | HTN | Albendazole Amlodipine Artesunate Aspirin Atorvastatin Azithromycin Metronidazole | No | Admitted for 4 days, discharged in stable condition | UNK | ||

| 38 M | Upper gastrointestinal bleeding, cardiac arrest | 38 | 42 | None reported | Pantoprazole Phenotone (phenobarbital) | No | Died, diagnosed with gastric cancer | 6 | ||

| 55 M | Hyponatremia, serum Na+ = 125 mmol/L | 80 | 90 | EtOH HTN Smoking | Amlodipine Aspirin Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan | No | Admitted, given intravenous fluids, discharged with serum Na+ = 135 mmol/L | 2 | ||

| Nonserious | Unrelated | 76 F | Urinary tract infection | 55 | 61 | Diabetes HTN | None | No | Given antibiotics, no further symptoms | 4 |

| 67 M | Swelling of L arm and L foot | 54 | 58 | HTN | Amlodipine Hydrochlorothiazide Losartan | No | Poststroke sequelae | 4 |

ALT = alanine transaminase; EtOH = alcohol use; HTN = hypertension; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; mRS= modified Rankin Scale; RMCA = right middle cerebral artery; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Serious adverse event is defined as an adverse event resulting in any of the following: death, disability, hospitalization > 24 hours, disability, or other life-threatening medical conditions.

Event relation to fluoxetine was measured on a Likert scale with the following response options: unrelated, unlikely, possible, probable, or definite.

Serious, possibly related.

A 62-year-old man with alcoholism was prescribed three antihypertensive medications poststroke: losartan, amlodipine, and hydrochlorothiazide. He had emesis because of unclear etiology (serum sodium study day 25: 120 mmol/L), was evaluated initially at Muhimbili National Hospital, and then died at home 2 days later.

Serious, unrelated.

A 38-year-old man had gastrointestinal hemorrhage (study day 38) with diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer and later death due to cardiac arrest.

Post-study, unrelated.

A 32-year-old man missed the 90-day study visit and died 11 days after the proposed study completion. He had dyspnea, cough, fever, hypotension (70/32 mmHg), ultimately diagnosed as COVID-19, and died of bronchopneumonia. He had prior anemia, malaria, worm infestation, and urinary tract infection.

Serum laboratory monitoring.

The mean serum sodium was baseline 138.7 mmol/L (SD = 2.9); 30 days: 137.2 (SD = 4.9); 60 days: 139.3 (SD = 4.0); and 90 days: 138.7 (SD = 2.9). The mean serum ALT was baseline 25.5 U/L (SD = 19.5); 30 days: 30.9 (SD = 23.5); 60 days: 26.2 (SD = 13.2); and 90 days: 28.1 (SD = 26.9).

Secondary outcomes.

Adherence.

The number of remaining fluoxetine pills was on average 59 (SD 8) at the 30-day visit; 32 (SD 10) at the 60-day study visit; and 4 (SD 9) at the 90-day study visit. Adherence was 96% for fluoxetine at the study end.

FMMS scores are seen in Table 3. MAMBO participants had slightly lower average FMMS scores compared with participants in FLAME; however, FMMS scores were generally similar across the two trials.

Table 3.

MAMBO FMMS scores with comparison to FLAME fluoxetine-treated group

| Time frame | Scale | MAMBO (N = 30) | FLAME (N = 57) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 90 | Total FMMS score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 62.7 (28.1) | 53.7 (27.8) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 65.5 (40.8–92.3) | 59.0 (22.0–47.5) | |

| Upper extremities | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.1 (22.2) | 29.7 (22.2) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 40.0 (17.0–60.0) | 32.0 (6.0–50.0) | |

| Lower extremities | |||

| Mean (SD) | 26.2 (6.8) | 24.0 (7.9) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 27.0 (24.0–32.0) | 27.0 (19.0–31.0) | |

| Change from enrollment to Day 90 | Total FMMS score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (22.4) | 36.4 (21.3) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 23.5 (19.0–49.3) | 34.0 (29.7–38.4) | |

| Upper extremities | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.0 (18.6) | 24.2 (19.8) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 15.0 (8.0–37.0) | 22.9 (18.6–27.1) | |

| Lower extremities | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.4 (8.0) | 12.2 (6.8) | |

| Median (25th–75th percentiles) | 10.0 (4.0–13.0) | 12.8 (11.1–14.5) | |

FMMS = Fugl-Meyer Motor Scale.

Depressive symptom burden.

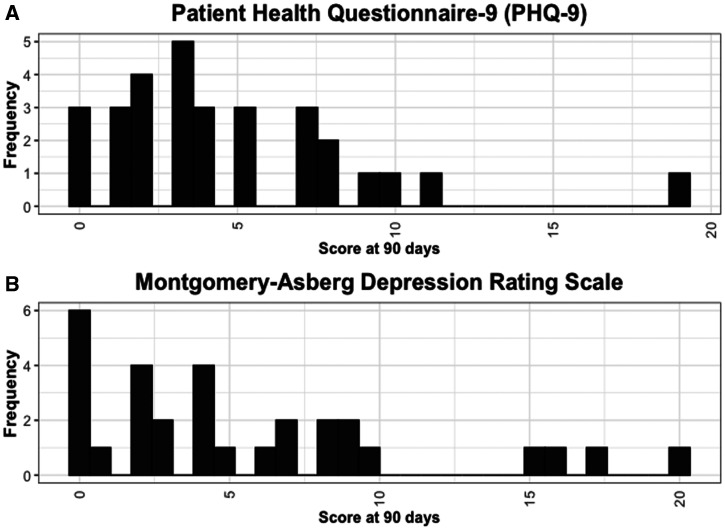

The Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating scale (mean 5.6 points, SD 5.5 points) and PHQ-9 (mean 4.6 points, SD 4.1 points) both indicated mild depression (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

90-day scores on the (A) Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and (B) Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

Poststroke cognition.

At enrollment, the mean MoCA score was 11.8 (SD = 6.5), and the mean IDEA score was 9.3 (SD = 4.5). At 90 days, the average MoCA score (15.9 points) was significantly higher than at enrollment (11.8 points), P = 0.01. The average IDEA score was also significantly higher at 90 days (enrollment: 9.3 points; 90 days: 12.3 points), P = 0.004.

Stroke impact scale.

The 90-day scores are provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

SIS scores at 90 days

| Female (N = 9) | Male (N = 13) | Total (N = 22) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall SIS score, mean (SD) | 57.2 (16.7) | 54.4 (13.7) | 55.5 (14.7) |

| Strength | 56.0 (23.9) | 43.2 (22.3) | 47.6 (23.3) |

| Memory and thinking | 70.9 (12.0) | 69.5 (13.1) | 70.0 (12.5) |

| Emotion | 60.0 (17.4) | 62.7 (9.1) | 61.6 (12.8) |

| Communication | 70.5 (22.4) | 66.8 (25.3) | 68.3 (23.7) |

| Activities of daily living | 61.1 (21.8) | 56.6 (18.1) | 58.5 (19.3) |

| Mobility | 62.5 (18.2) | 64.3 (16.8) | 63.5 (17.0) |

| Hand function | 50.2 (38.4) | 37.2 (30.7) | 42.5 (33.8) |

| Social participation | 47.8 (27.7) | 47.1 (24.5) | 47.4 (25.2) |

SIS = stroke impact scale.

DISCUSSION

Fluoxetine poststroke was overall safe in Tanzanian participants with important exceptions that could impact its use in similar locations. Several issues of pragmatic value for future early-phase trials for stroke in similar settings were identified. Although the use of poststroke fluoxetine is less likely for motor recovery given the results of recent trials,2–4 fluoxetine remains a leading medication option for depression management.

MAMBO used strict criteria for enrollment to identify participants who would likely benefit and not be harmed by poststroke fluoxetine. At Muhimbili National Hospital, the postischemic stroke fatality is 50% at 90 days.19 Our trial had two participant deaths within 90 days (6%), neither of which were directly attributed to fluoxetine, with a third participant dying shortly after the study period, due to COVID-19. Given the resource-limited setting and the COVID-19 pandemic, the trial proceeded with very limited loss to follow-up and nearly complete fluoxetine adherence. By comparison, FLAME reported three deaths in 118 participants at 90 days. MAMBO demonstrates the feasibility of careful participant selection that can lead to uptake of rigorous and detailed evaluations poststroke in nearly all participants. The resource constraints in Tanzania are notable, with a standard of stroke care that is not comparable to any of the major studies on fluoxetine to date.

We included three participants with MRI brain interpretations that did not confirm an acute ischemic stroke on secondary reading by a U.S. neuroradiologist post-study. As brain MRI is not a standard of care in Tanzania for stroke patients, we enrolled two participants with either transient ischemia or no stroke. One of these participants had a reported adverse event that was considered unlikely related to fluoxetine (aphasia, mental status changes, hypokalemia), which could have been a recurrent transient ischemic episode. The 90-day mRS was 0. A different participant had no acute brain MRI findings and no adverse event. A third participant had a chronic infarct and no adverse event. We demonstrate the complexity of enrolling stroke participants in resource-limited settings where competing diagnoses are common, stroke patients are overall younger, and central nervous system infectious diseases are prevalent. Access to brain MRI in locations like Muhimbili National Hospital is increasing. This access requires subspecialty expertise in brain MRI interpretation in real time.

One unanticipated practice for poststroke management at Muhimbili National Hospital that may have impacted our results is the rapid treatment of hypertension using multiple antihypertensive therapies. This may occur during hospitalization or upon hospital discharge. As many participants were treated with two to three antihypertensives for the first time, concomitant with fluoxetine, new-onset hyponatremia may have resulted from hydrochlorothiazide, fluoxetine, or their combination. Although fluoxetine was unlikely to be the major cause of any electrolyte disturbance poststroke, its addition to multiple other medications that can cause hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypomagnesemia make the disaggregation of effects of a single new pill difficult. In the clinical setting, poststroke laboratory monitoring for hyponatremia is feasible, at least for patients in urban settings, but would require a shift in current practice, as recurring poststroke clinic visits are not usual. There may be additional benefits to a poststroke clinic approach including poststroke blood pressure management; testing for other risk factors such as diabetes and dyslipidemia; screening for cognitive loss and depression; and reassessment of swallowing, spasticity, balance, and gait. Poststroke clinics also represent an excellent opportunity for task-sharing and task-shifting to non-neurologist providers. Given the high 90-day poststroke mortality documented in this setting, recurrent poststroke clinic visits may indeed reflect an important point of intervention with a higher yield for improving outcomes than many other practices in place in resource-limited settings.

Resource limitations affected other poststroke outcomes of trial participants. Participants who experienced stroke secondary to other medical illnesses may not have had detection of those conditions at the time of stroke diagnosis. Recurrent stroke in poststroke recovery trials is likely higher in Tanzania compared with studies elsewhere. One participant succumbed to gastrointestinal malignancy with a gastrointestinal hemorrhage, diagnosed after enrollment. This would have been an excluded condition if known at the time of enrollment. Internal hemorrhage is noted as a rare adverse event with fluoxetine; however, in the case of underlying gastrointestinal malignancy, its role is less likely to be causative.

Although our sample size was smaller than in FLAME and our primary aim was safety rather than efficacy, some comparisons of the participants between MAMBO and FLAME can be made. MAMBO had younger participants with overall better stroke recovery as measured by the 90-day mRS scores. FLAME does not specifically comment on the types or amount of physical rehabilitation use by its participants, although it is presumed this is routinely available in France. MAMBO participants had very little access to physical therapy and rehabilitation with no rehabilitation hospital admissions. Despite differences across these groups, the FMMS scores and their distribution between the two trial populations appeared very similar. Given the differences in age, location, expertise, and resources, the comparable FMMS scores imply that the FMMS has validity across populations and settings for assessment of poststroke recovery.

We also report carefully acquired postischemic stroke depressive scores in Tanzanian stroke participants, which are on average in the mild depression range. Notably, depressive symptom burden was almost never severe or even moderate in MAMBO. Although both the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the PHQ-9 are used in sub-Saharan Africa, their validity is still being established. We used the two most used depressive symptom burden scales in MAMBO to demonstrate that the findings are consistent across two scales. Our results suggest that clinically significant poststroke depression could be treated safely with fluoxetine in appropriately selected and followed patients.

MAMBO also used several other exploratory metrics for the poststroke recovery period including cognitive tests, dynamometer readings, and the SIS. These measurements were primarily performed to demonstrate feasibility for larger phase III studies.

Our study had several limitations. There was no placebo group. Three participants were later found to lack diffuse weighted imaging (DWI) changes on brain MRI when read by an off-site neuroradiologist. We are unable to report on whether fluoxetine in combination with other interventions would be valuable or is influenced by physical therapy. Depression was not measured at enrollment.

We nonetheless performed a rigorous evaluation of Tanzanian stroke participants with high participant adherence and follow-up. Stroke trials with pharmacological interventions, targeted to African needs and resources, and executed with African researchers’ priorities are rare. We demonstrate the feasibility of poststroke research in this setting.

Our phase II clinical trial also provides the opportunity to share several lessons learnt for others who may wish to conduct early phase medication trials in similar settings for stroke recovery or related noncommunicable diseases. First, there is a lengthy and resource-intense process to gain approvals to proceed with a repurposed drug trial across locations, languages, and governing boards. These processes ensure safety for participants and adequate documentation but are not adapted for investigator-initiated small trials to get rapid results. Second, the differential diagnosis of stroke is much broader and more difficult to vet in resource-limited settings and in overall younger patients, leading to the risk of enrollment of patients who may have strokes secondary to other conditions unless considerable attention is paid to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Third, there was high adherence to the medications but limited reporting of adverse events spontaneously by participants. The recurring 30-day visits were helpful for ensuring no adverse events were overlooked. Finally, the design and engagement of multidisciplinary teams led to both capacity building as well as success in trial conduct. This included physical therapy, pharmacy, medical specialties (neurology, radiology), and regulatory affairs expertise. The involvement of junior and new investigators was crucial. Improved overall awareness of neurology and neuroscience was an additional goal of the MAMBO trial, highlighting these fields as career pathways to neurologists-in-training and future researchers.

In lower-income populations globally, poststroke care is nonstandard and often absent. We identify specific issues that may make fluoxetine use necessary to monitor more closely poststroke in Tanzania, including its combination with aggressive management of hypertension with medications that cause hyponatremia. We place MAMBO in context of the FLAME, AFFINTY, EFFECTS, and FOCUS results, in case lower-income, younger, African populations, demonstrate a different balance of risks and benefits and an absence of other self-reported risks such as bone fractures.

Supplemental Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ashfaq Shuaib, University of Alberta, and Graeme Hankey, University of Western Australia, for their helpful communications and efforts on reviewing participant safety data. We thank Annie Elieza for her support with ethics board document submissions in Tanzania.

Note: Supplemental materials appear at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nagayoshi M Everson-Rose SA Iso H Mosley TH Jr Rose KM Lutsey PL , 2014. Social network, social support, and risk of incident stroke: atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke 45: 2868–2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toivanen S , 2012. Social determinants of stroke as related to stress at work among working women: a literature review. Stroke Res Treat 2012: 873678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avendano M Kawachi I Van Lenthe F Boshuizen HC Mackenbach JP Van den Bos GA Fay ME Berkman LF , 2006. Socioeconomic status and stroke incidence in the US elderly: the role of risk factors in the EPESE study. Stroke 37: 1368–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chollet F et al. 2011. Fluoxetine for motor recovery after acute ischaemic stroke (FLAME): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 10: 123–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dennis M et al. 2019. Effects of fluoxetine on functional outcomes after acute stroke (FOCUS): a pragmatic, double-blind, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 393: 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lundström E et al. 2020. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional recovery after acute stroke (EFFECTS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 19: 661–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hankey GJ et al. 2020. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 19: 651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Almeida OP et al. 2021. Depression outcomes among patients treated with fluoxetine for stroke recovery: the AFFINITY randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 78: 1072–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vogel AC et al. 2020. MAMBO: measuring ambulation, motor, and behavioral outcomes with post-stroke fluoxetine in Tanzania: protocol of a phase II clinical trial. J Neurol Sci 408: 116563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldstein LB Bertels C Davis JN , 1989. Interrater reliability of the NIH stroke scale. Arch Neurol 46: 660–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gladstone DJ Danells CJ Black SE , 2002. The Fugl-Meyer assessment of motor recovery after stroke: a critical review of its measurement properties. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 16: 232–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quinn TJ et al. 2009. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale: a systematic review. Stroke 40: 3393–3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasreddine ZS et al. 2005. The Montreal cognitive assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 53: 695–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray WK et al. 2014. Development and validation of the identification and intervention for dementia in elderly Africans (IDEA) study dementia screening instrument. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 27: 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paddick S-M et al. 2015. Validation of the identification and intervention for dementia in elderly Africans (IDEA) cognitive screen in Nigeria and Tanzania. BMC Geriatr 15: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K Spitzer RL Williams JB , 2001. The PHQ‐9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 16: 606–613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmerman M Posternak MA Chelminski I , 2004. Derivation of a definition of remission on the Montgomery–Asberg depression rating scale corresponding to the definition of remission on the Hamilton rating scale for depression. J Psychiatr Res 38: 577–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai S-M et al. 2002. Persisting consequences of stroke measured by the stroke impact scale. Stroke 33: 1840–1844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Regenhardt RW et al. 2019. Opportunities for intervention: stroke treatments, disability and mortality in urban Tanzania. Int J Qual Health Care 31: 385–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okeng’o K et al. 2017. Early mortality and associated factors among patients with stroke admitted to a large teaching hospital in Tanzania. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 26: 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.