Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the epidemiology of systemic sclerosis in Valcamonica, an Italian Alpine valley, during an 18-year-long period.

Methods:

Patients with systemic sclerosis living in Valcamonica between 1999 and 2016 were identified by capture/recapture method using: (1) clinical databases of the only secondary Rheumatology Unit present in the valley and of the tertiary referral center for this area; (2) administrative data, extracting records with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, code for systemic sclerosis. Patients were included in the analysis when either the 1980 American Rheumatism Association classification criteria for systemic sclerosis or the 2013 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria were satisfied. To study temporal changes, mean yearly incidence during three different 6-year interval was calculated. Prevalence rates were estimated at four different time points.

Results:

General population with age over 14 years living in Valcamonica varied during the evaluated period between 85,168 and 91,245 inhabitants. A total of 65 patients with systemic sclerosis were identified (female 84.6%, limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis: 84.6%; anticentromere: 64.6%). Systemic sclerosis incidence and prevalence increased during the study period (p = 0.029 and p < 0.0001, respectively). The increase of incidence was accounted for by cases satisfying only the 2013 criteria, with limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis, and with anticentromere, whereas the incidence of systemic sclerosis cases classified according to the 1980 criteria did not significantly increase. The prevalence at 31 December 2016 was 58.6 (95% confidence interval, 44.8–76.6) per 100,000 persons aged >14 years. Survival at 10 years after systemic sclerosis diagnosis was 83.0% (standard error, 5.6).

Conclusion:

Systemic sclerosis incidence and prevalence increased over time in this area, due to the increased recruitment of patients with milder forms of the disease.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis, epidemiology, incidence, prevalence, classification criteria

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an autoimmune connective tissue disease characterized by immune activation, vasculopathy, and progressive fibrosis of the skin and internal organs. 1

Previous epidemiological studies demonstrated a great variability in the incidence and prevalence of SSc.2,3 This variability might be explained not only by true genetic and/or environmental factors but also by variability in the design and methods used in the studies. 2 Moreover, classification criteria developed in 1980 by the American Rheumatism Association (now the American College of Rheumatology, ACR) 4 lacked sensitivity for early SSc and limited cutaneous SSc (lSSc) and were therefore not very suitable to precise disease prevalence and incidence evaluation. Therefore, more recent epidemiological studies also considered SSc cases defined by the criteria for the classification of early SSc suggested by LeRoy and Medsger 5 in 2001. These criteria, however, were never validated. More sensitive criteria, also useful for early SSc patients’ classification, were developed only in 2013 by a joint effort of the ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR). 6

Despite these limitations, it is notable that the estimated prevalence of SSc in Italy in the first decade of the 2000 was very similar in three epidemiological studies, although performed in different areas of the country (Brescia, Ferrara, and Sardinia). Using multiple source case ascertainment, and both the 1980 ACR and the LeRoy and Medsger classification criteria to define SSc cases, in these studies SSc prevalence was calculated to be around 35 cases per 100,000 inhabitants.7–9 This was much higher than that observed in the decade 1966–1975 in an Italian tertiary referral Hospital (1 per 100,000 inhabitants). 10

However, there is a general lack of information on the variations in SSc incidence and prevalence over time. Moreover, no study has yet applied the new 2013 classification criteria in studying the SSc epidemiology in Italy. It is likely that these new criteria can identify more SSc cases, as shown by a Swedish study, in which their application resulted in a 30%–40% higher estimate of SSc incidence and prevalence compared to the previous 1980 criteria. 11

A further evaluation of SSc epidemiology in Italy might therefore be useful to evaluate epidemiology variations over time and the impact of EULAR/ACR 2013 classification.

For these purposes, we have evaluated the variations in prevalence and incidence rates of SSc over an 18-year period in Valcamonica, Province of Brescia, Italy.

Methods

Valcamonica and its healthcare system

Valcamonica is an Alpine valley located in the Province of Brescia, Italy. General population with age over 14 years living in Valcamonica varied during the study period (1999–2016), slowly increasing from 85,168 (1999) to 91,245 inhabitants (2011), and thereafter decreasing. 12 Access to public healthcare in Italy is high, irrespective of socioeconomic factors.

There is only one secondary Rheumatology Unit in the valley (Esine Hospital). The Department of Rheumatology of the Spedali Civili/University Hospital in Brescia is a referral center for SSc. There is a long-standing collaboration between the two hospitals, including direct contact between rheumatologists for cases referral.

Disease certification is needed to exempt from payment of disease-related medical costs and was recorded by the Azienda Socio-Sanitaria Territoriale, Agenzia di Tutela della Salute della Montagna (ASST Valcamonica, ATS Montagna).

The study was approved by the Brescia Provincial Ethics Committee.

SSc identification and case ascertainment

All patients with clinical diagnosis of SSc living in Valcamonica between 1999 and 2016 were identified by capture/recapture method using: (1) clinical databases of the Esine Hospital and of the Spedali Civili, Brescia; (2) administrative data (ASST Valcamonica, ATS Montagna) extracting all records with the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) code for SSc (710.1). All clinical charts were reviewed by a senior rheumatologist (P.A.), and patients were included in the analysis when either the 1980 ACR classification criteria for SSc 4 or the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria 6 were satisfied.

Characterization of patients

Patients were classified into diffuse SSc (dSSc) or lSSc according to LeRoy et al. 13 Patients were evaluated according to standardized procedures; since 2003, essential clinical data were recorded in the EUSTAR registry.14,15 All patients were tested for antinuclear antibodies, anticentromere (ACA), and anti-topoisomerase I, and in 60 cases also for autoantibodies against anti-RNA polymerase III (although, not always at the moment of our first evaluation).

Survival status of all patients was established by contacting the patients themselves or relatives. Information on date of death was obtained by the regional public health system. 16 No patient was lost at follow-up.

Incidence estimates

Incidence was estimated using the number of new cases observed as the numerator, and the Valcamonica population with age over 14 years as the denominator for each year; to study temporal changes, mean yearly incidence during three different 6-year intervals was calculated.

Prevalence evaluation at different time points

Prevalence rates were estimated at four different time points dividing the number of living patients by the number of individuals with age over 14 years in the population.

Statistical analysis

Demographic data were expressed as the median (interquartile range, IQR). Incidence and prevalence rates were expressed with 95% confidence intervals. Incidence and prevalence rates observed in different periods were compared using contingency tables. Survival was estimated with the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

Using multiple source case ascertainment, patients with SSc with age over 14 years resident in Valcamonica during the study period (1999–2016) were identified. After the review of the clinical charts, SSc clinical diagnosis was confirmed in 68 cases; 65 patients fulfilled the 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria, and 45 of them (69%) also the 1980 criteria. Only cases fulfilling the ACR/EULAR criteria were considered for further analysis. The source of cases is described in Figure 1. In 14 cases, the diagnosis of SSc was made before the time period considered in the study and in 51 cases during this period. Main demographic and clinical features are reported in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Source of SSc cases.

Table 1.

Main demographic, laboratory, and clinical features of 65 patients with SSc.

| Sex | Female | 55 (84.6%) |

| Male | 10 (15.4%) | |

| Race | Caucasian | 63 (96.9%) |

| African | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Sub-Saharan | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Age at diagnosis | 60 (45–67) | |

| Subset | Diffuse SSc | 10 (15.4%) |

| Limited SSc | 55 (84.6%) | |

| Autoantibodies | Anticentromere | 42 (64.6%) |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (topo I) a | 10 (15.4%) | |

| Anti-RNA polymerase III (RNAP3) a | 4/60 (6.7%) | |

| Anti-Th/To | 1/60 (1.7%) | |

| Anti-PM/Scl | 1/60 (1.7%) | |

| Main clinical features | Interstitial lung disease | 12 (18.5%) |

| Group 1 pulmonary arterial hypertension | 11 (16.9%) | |

| Renal crisis | 4 (6.2%) |

SSc: systemic sclerosis.

One patient was positive both for anti-topo I and RNAP3.

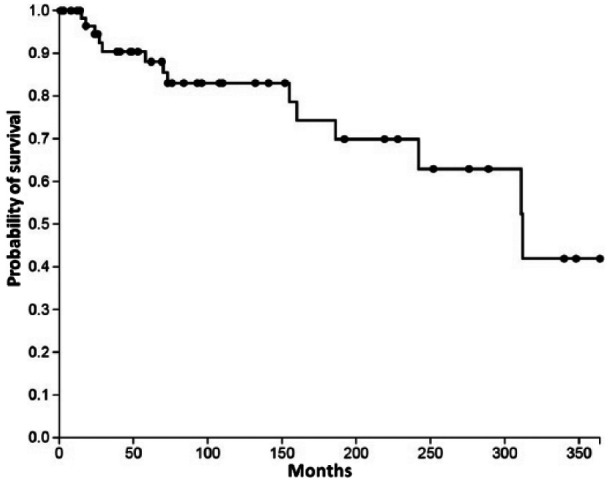

Among this population, 14 cases of death were observed during the study period (in six cases, main cause was related to SSc). Survival estimated by Kaplan–Meier analysis was at 3 years: 90.4% (standard error (SE), 4.1); at 5 years: 88.0% (4.6); at 10 years: 83.0% (5.6; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Survival of patients after SSc diagnosis.

The incidence and prevalence of SSc during the study period are reported in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Table 2.

Incidence of SSc in Valcamonica.

| Sex | Study period | Mean population >14 years | New diagnosis with 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria | Incidence (95% CI) with 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria | New diagnosis with 1980 ARA criteria | Incidence (95% CI)with 1980 ARA criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male + female | 1999–2004 | 86,205.5 | 9 | 1.74 (0.9–3.3) | 8 | 1.55 (0.8–3.1) |

| 2005–2010 | 89,448.5 | 17 | 3.17 (2–5.1) | 10 | 1.86 (1.0–3.4) | |

| 2011–2016 | 90,843 | 25 | 4.59 (3.1–6.8) | 15 | 2.75 (1.7–4.5) | |

| Female | 1999–2004 | 44,106.5 | 6 | 2.27 (1–4.9) | 6 | 2.27 (1.0–4.9) |

| 2005–2010 | 45,339.5 | 14 | 5.15 (3.1–8.6) | 7 | 2.57 (1.2–5.3) | |

| 2011–2016 | 46,008.5 | 22 | 7.97 (5.3–12.1) | 13 | 4.71 (2.7–8.1) | |

| Male | 1999–2004 | 42,099 | 3 | 1.19 (0.4–3.5) | 2 | 0.79 (0.2–2.9) |

| 2005–2010 | 44,109 | 3 | 1.13 (0.4–3.3) | 3 | 1.13 (0.4–3.3) | |

| 2011–2016 | 44,834.5 | 3 | 1.12 (0.4–3.3) | 2 | 0.74 (0.2–2.7) |

SSc: systemic sclerosis; ACR: American College of Rheumatology; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; CI: confidence interval; ARA: American Rheumatism Association.

Table 3.

Prevalence of SSc in Valcamonica.

| Sex | Date | Population >14 years | Living cases with 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria | Prevalence (95% CI) with 2013 ACR/EULAR criteria | Living cases with 1980 ARA criteria | Prevalence (95% CI) with 1980 ARA criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male + female | 31 December 1999 | 85,168 | 14 | 16.44 (9.8–27.6) | 13 | 15.26 (8.9–26.1) |

| 31 December 2005 | 88,011 | 24 | 27.27 (18.3–40.6) | 21 | 23.86 (15.6–36.4) | |

| 31 December 2011 | 91,245 | 38 | 41.65 (30.3–57.2) | 27 | 29.59 (20.3–40.1) | |

| 31 December 2016 | 90,441 | 53 | 58.60 (44.8–76.6) | 35 | 38.7 (27.8–53.8) | |

| Female | 31 December 1999 | 43,755 | 13 | 29.71 (17.4–50.8) | 12 | 27.43 (15.7–47.9) |

| 31 December 2005 | 44,751 | 20 | 44.69 (28.9–69.0) | 19 | 42.46 (27.2–66.3) | |

| 31 December 2011 | 46,149 | 33 | 71.51 (50.9–100.4) | 22 | 47.67 (31.5–72.2) | |

| 31 December 2016 | 45,868 | 47 | 102.47 (77.1–136.2) | 30 | 65.41 (45.8–93.4) | |

| Male | 31 December 1999 | 41,413 | 1 | 2.41 (0.4–13.7) | 1 | 2.41 (0.4–13.7) |

| 31 December 2005 | 43,260 | 4 | 9.25 (3.6–23.8) | 2 | 4.62 (1.3–18.9) | |

| 31 December 2011 | 45,096 | 5 | 11.09 (4.7–26.0) | 5 | 11.09 (4.7–25.9) | |

| 31 December 2016 | 44,573 | 6 | 13.46 (6.2–29.4) | 5 | 11.22 (4.8–26.3) |

SSc: systemic sclerosis; ACR: American College of Rheumatology; EULAR: European League Against Rheumatism; CI: confidence interval; ARA: American Rheumatism Association.

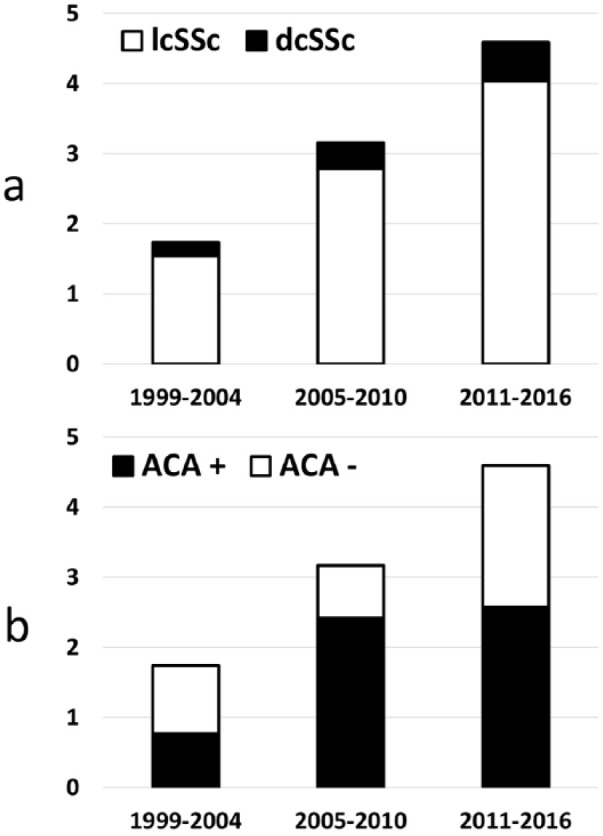

A significant increase in incidence was observed during the period of time evaluated in the study (G-test: p: 0.029; Table 2). Notably, the increase in incidence of SSc cases classified according to the 1980 criteria was not significant (G-test: p: 0.37). Analogously, the incidence of cases with limited cutaneous involvement or ACA increased (p: 0.05 and p: 0.04, respectively), but not that of cases with diffuse cutaneous involvement or without ACA (p: 0.63 and p: 0.14, respectively; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Incidence of SSc cases (n/100,000 inhabitants aged over >14 years) divided according to cutaneous subset (panel a) and ACA positivity (panel b).

Analysis of SSc prevalence also revealed a continuous increase, using both the 1980 criteria and 2013 criteria (p < 0.00001 for both comparisons; Table 3). The proportion of living patients with a SSc diagnosis not satisfying the 1980 criteria within the whole group of SSc patients increased with time (p: 0.02; contingency tables).

The prevalence of SSc in Valcamonica at 31 December 2016 was 58.6 (44.8–76.6) per 100,000 persons with age over 14 years.

Discussion

There is a lack of information on the variations of SSc epidemiology over time in Italy. This lack is particularly relevant, since it has been demonstrated that an evolution of SSc pathomorphosis took place in the last years in Italy. 17

In this study, using multiple source case ascertainment, we have demonstrated a continuous increase of SSc incidence and prevalence rates in Valcamonica. The prevalence in 2016 was 58.6 per 100,000 persons aged >14 years, one of the highest ever recorded by SSc epidemiology studies. However, notably, the prevalence in Valcamonica at 31 December 2005 was 27.3 per 100,000, a figure very similar to that reported by previous other studies performed in Italy during the first decade of 2000, in which a prevalence ranging between 33.9 and 35 per 100,000 was calculated.7–9

In our series, the large majority of patients were female (84.6%) and had limited cutaneous involvement (84.6%) and ACA positivity (64.6%). An analogous observation was reported by a large study including 821 patients from three Italian centers: patients recruited in recent years were shown to have favorable clinical and prognostic parameters, including limited cutaneous involvement and ACA, compared to those observed during previous decades in the same geographical areas.17,18 The low proportion of patients with autoantibodies against anti-RNA polymerase III, a marker which recently deserved much attention for its clinical associations, including that with malignancies synchronous to SSc onset, 19 was similar to that observed in other Italian series by others and us.20,21

We have also shown that the proportion of SSc patients satisfying the 2013 criteria but not the 1980 criteria increased with time and that the increase in SSc incidence was accounted for by cases satisfying only the 2013 criteria, whereas the incidence of SSc cases classified according to the 1980 criteria did not significantly increase.

Taken together, these observations lead to the hypothesis that the increase in SSc incidence might be related to more diffuse physician and patient awareness of the disease and availability of diagnostic tools and consequent wider recruitment of patients in the early stages of the disease. 17

Accordingly, in our series, 10 years’ survival after SSc diagnosis was 83.0%. This result is very similar to that recently reported by an Italian multicenter study (80.7%), 17 which was clearly higher than previous series from the same centers (69.2%). 18 A progressive decrease in mortality rate during the first decade of 2000 in SSc was also demonstrated by a nationwide analysis in France. 22 These findings are mirrored by the literature analysis which demonstrated progressive improvement of SSc survival during the last five decades, indicating an evolution of SSc prognosis, too. 17

Previous studies reported an increase in the SSc incidence rate over time in United States and Australia23–25 during decades-long periods. It has been pointed out that case ascertainment methods also improved during this period, making it problematic to interpret these results. 3 However, the interval between a previous study of ours 7 and this study is relatively short (12 years), and case ascertainment methods was very similar in these two studies. Moreover, recent data from Northern Europe, an area traditionally considered to have lower SSc occurrence than Southern Europe, also found greatly higher SSc prevalence and incidence than those observed in the same areas a few decades before, and an increase of cases with limited cutaneous involvement,11,26 similar to what observed in Italy. It is therefore likely that this pathomorphosis evolution is a general phenomenon that could be observed also in other countries.

Our study may suffer from some limitations, including the relatively small population observed. However, a crucial issue in prevalence studies is the identification of cases, which should be as complete as possible. This objective was pursued using multiple sources and was probably achieved, as far as cases with a known diagnosis of SSc are concerned, as suggested by the concordance between the clinical and administrative sources.

We acknowledge that we cannot exclude potential sources of missed SSc patients: (1) the practices of dermatologists or specialists other than rheumatologist and immunologist; however, the organization of healthcare in Valcamonica makes this possibility unlikely, and such cases were not identified by administrative forms including disease certification. (2) Patients resident in Valcamonica who received diagnosis and care outside of the area; again, these patients should anyway receive diagnosis certification in Valcamonica and such cases were not identified. (3) Individuals with undiagnosed SSc (possibly, with even milder forms of disease).

Finally, we did not apply the capture/recapture technique to estimate the number of missed patients and correct the prevalence estimates, since this correction can be applied only when the case sources are independent, which was clearly not the case in our study. 27

For these reasons, we cannot exclude that the prevalence of SSc is even higher than that estimated here. However, it is likely that large majority of patients who sought medical advice were identified in our study. Since offering someone a diagnosis of SSc is not appropriate if the patient has no active problems, 28 our study offers a reasonable estimate of the prevalence of clinically relevant SSc in northern Italy. These results may have important value for clinical practice and healthcare provision strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Andrea Premoli, Dr Francesca Dall’Ara, and Dr Alessandra Bettinardi for their help in data collection.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Paolo Airò  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5241-1918

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5241-1918

References

- 1. Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017; 390: 1685–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 37(4): 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnes JK, Mouthon L, Mayes MD. Epidemiology, environmental, and infectious risk factors. In: Varga J, Denton CP, Wigley FM, et al. (eds) Scleroderma: from pathogenesis to comprehensive management. New York: Springer, 2017, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association diagnostic therapeutic criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum 1980; 23: 581–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. LeRoy EC, Medsger TA., Jr. Criteria for the classification of early systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol 2001; 28(7): 1573–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. Classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013; 65(11): 2737–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Airo P, Tabaglio E, Frassi M, et al. Prevalence of systemic sclerosis in Valtrompia in northern Italy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2007; 25(6): 878–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lo Monaco A, Bruschi M, La Corte R, et al. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis in a district of northern Italy. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2011; 29(2 Suppl. 65): S10–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sardu C, Cocco E, Mereu A, et al. Population based study of 12 autoimmune diseases in Sardinia, Italy: prevalence and comorbidity. PLoS ONE 2012; 7(3): e32487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giordano M. Epidemiology of progressive systemic sclerosis in Italy. In: Black CM, Myers AR. (eds) Progressive systemic sclerosis (current topics in rheumatology). New York: Gower, 1985, pp. 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andréasson K, Saxne T, Bergknut C, et al. Prevalence and incidence of systemic sclerosis in southern Sweden: population-based data with case ascertainment using the 1980 ARA criteria and the proposed ACR-EULAR classification criteria. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 1788–1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.http://demo.istat.it/

- 13. LeRoy EC, Black C, Fleischmajer R, et al. Scleroderma (systemic sclerosis): classification, subsets and pathogenesis. J Rheumatol 1988; 15(2): 202–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bombardieri S, Medsger TA, Jr, Silman AJ, et al. The assessment of the patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2003; 21(3 Suppl 29): S2–S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Meier FM, Frommer KW, Dinser R, et al. Update on the profile of the EUSTAR cohort: an analysis of the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research group database. Ann Rheum Dis 2012; 71(8): 1355–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.siss.regione.lombardia.it/

- 17. Ferri C, Sebastiani M, Lo Monaco A, et al. Systemic sclerosis evolution of disease pathomorphosis and survival. Our experience on Italian patients’ population and review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev 2014; 13(10): 1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ferri C, Valentini G, Cozzi F, et al. Systemic sclerosis: demographic, clinical, and serologic features and survival in 1,012 Italian patients. Medicine 2002; 81(2): 139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lazzaroni MG, Airò P. Anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies in patients with suspected and definite systemic sclerosis: why and how to screen. J Sclerod Relat Disord 2018; 3: 214–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sobanski V, Dauchet L, Lefèvre G, et al. Prevalence of anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies in systemic sclerosis: new data from a French cohort and a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 407–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Airò P, Ceribelli A, Cavazzana I, et al. Malignancies in Italian patients with systemic sclerosis positive for anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies. J Rheumatol 2011; 38(7): 1329–1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Elhai M, Meune C, Boubaya M, et al. Mapping and predicting mortality from systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(11): 1897–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medsger TA, Jr, Masi AT. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Ann Intern Med 1971; 74(5): 714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Steen VD, Oddis CV, Conte CG, et al. Incidence of systemic sclerosis in Allegheny county, Pennsylvania. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40(3): 441–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roberts-Thomson PJ, Walker JG, Lu TY, et al. Scleroderma in South Australia: further epidemiological observations supporting a stochastic explanation. Intern Med J 2006; 36(8): 489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Geirsson AJ, Steinsson K, Guthmundsson S, et al. Systemic sclerosis in Iceland. Ann Rheum Dis 1994; 53(8): 502–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tilling K. Capture—recapture methods—useful or misleading? Int J Epidemiol 2001; 30: 12–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Allcock RJ, Forrest I, Corris PA, et al. A study of the prevalence of systemic sclerosis in northeast England. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004; 43(5): 596–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]