Abstract

Gastrointestinal involvement is the most common visceral organ manifestation in systemic sclerosis. Symptoms from the gastrointestinal tract are very frequent among scleroderma patients and in many cases present a therapeutic challenge. However, gastrointestinal involvement may also be asymptomatic, presenting with complications later in the disease course. Early recognition of gastrointestinal scleroderma is therefore important both for symptomatic control and prevention of complications. Gastrointestinal imaging alongside clinical assessment forms the mainstay of diagnosis. Radiological investigations, traditionally plain radiographs and barium studies, with the more recent advances in computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound, provide means for accurate evaluation of visceral organ involvement and more effective patient care. Awareness of the characteristic images is important not only for radiologists but also for the treating physicians and gastroenterologists.

Keywords: Scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, gastrointestinal involvement in scleroderma, gastroparesis, intestinal pseudo-obstruction, oesophageal dilatation, gastroesophageal reflux, scleroderma radiological imaging, dysmotility

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis is a chronic multisystem disorder with heterogeneous clinical manifestations involving the skin, lungs, heart, kidneys, musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal (GI) systems. The disease is characterized by sclerotic skin lesions as a result of collagen deposition in the skin, and hence, also known as scleroderma (meaning ‘hard skin’ in Greek). Scleroderma is an uncommon, rather than rare, condition, affecting 88 per million people in the United Kingdom, with a female preponderance of 4:1. 1

Traditionally, systemic sclerosis (SSc) is divided into limited (lcSSc) and diffuse cutaneous (dcSSc) disease. The classification is based on the extent of skin and concomitant visceral organ involvement. 2 In diffuse cutaneous SSc there is skin sclerosis extending to proximal limbs, trunk and neck, while in limited cutaneous disease sclerosis is confined to areas distal to elbows and knees, with or without facial involvement. 2 In dcSSc there is a greater risk of respiratory, cardiac and renal manifestations, with faster disease progression and increased morbidity and mortality.

GI involvement occurs in more than 90% of scleroderma patients, affecting both diffuse and limited cutaneous subtypes in almost identical patterns. 3 Any part of the GI tract can be involved, with the oesophagus being the most prevalent one. Patients suffer due to problems with digestion, absorption and excretion, anywhere from the mouth to the anus. 4 Despite advances in diagnosis and management, the more severe GI manifestations of SSc carry a poor prognosis, with 5-year mortality rates exceeding 50%. 5 Fortunately, only 8% of patients will develop severe GI disease. A considerable percentage will remain asymptomatic for a long time, despite upper and lower GI tract involvement. Many of them will present symptoms late in the disease course. Advanced GI scleroderma is associated with poor quality of life, contributing further to the overall morbidity of the disease.

Pathophysiology

SSc is a progressive connective tissue disorder of autoimmune origin. The exact mechanisms underlying the complex pathogenesis of the disease remain to be fully understood. The resultant disease phenotype is a combination of pathobiological mechanisms involving innate and adaptive immunity, together with vascular, neural and connective tissue dysfunction. Excessive production and deposition of structurally normal collagen and other extracellular matrix molecules, alongside microvascular damage and neural pathology, lead eventually to muscle atrophy and fibrosis, with skin and visceral organ damage. 2 The commonest hypothesis for the observed neuronal and myogenic abnormalities involves an initial vascular dysfunction causing endothelial cell injury and small vessel obliteration. An inflammatory phase follows where there is aggregation of perivascular mononuclear infiltrates, as well as cytokine and growth factor upregulation. Finally, the increased deposition of extracellular matrix components alongside the destruction of normal tissue results in the characteristic fibrosis. 2 Central role to these processes has the activated fibrogenic fibroblast population that seems to act as an effector cell to the disease. 6 Animal models have been developed confirming fibroblast dysfunction in scleroderma, and showing that enhanced TGF-β activity is linked to organ fibrosis. 7 The clinical benefit from IV immunoglobulin in cases of GI scleroderma with overlap myositis further supports the immunological pathophysiology underlying SSc. 8

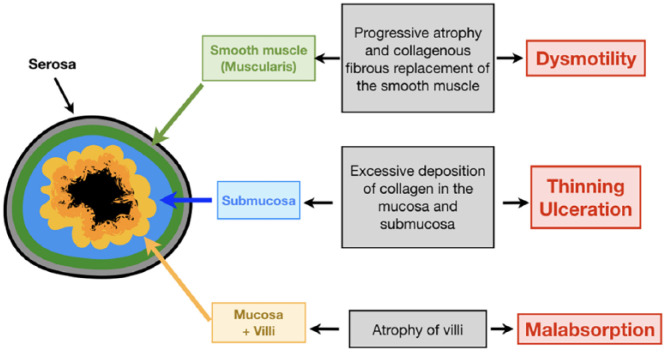

Regardless of site, GI SSc pathology involves progressive atrophy and collagenous replacement of the circular smooth muscle layer, with resultant GI tract dysmotility (Figure 1). Recent evidence suggests that aspiration secondary to gastroesophageal reflux causes peri-bronchial changes and is implicated in the development of interstitial lung disease 9 (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Schematic cross-section of bowel wall layers showing how scleroderma affects the different layers of the bowel wall.

Figure 2.

Frontal chest radiograph in a 42-year-old man with scleroderma on the waiting list for a lung transplant, showing a dilated oesophagus with an air/fluid level (black arrow) and severe scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (basal) (SSc-ILD) (white arrow).

Diagnosis and management

In practice, the diagnosis of scleroderma is clinical and serological tests are used to identify different SSc phenotypes, classify disease subtypes and exclude scleroderma mimics. Radiological investigations help quantify the extent and stage of visceral involvement and confirm clinical findings. Imaging changes can precede symptom onset.

The management of GI SSc is mainly symptomatic. The progressive nature of the disease, together with the short-term efficacy and side effects of medications, limit even further the therapeutic options. A proportion of patients will eventually require enteral feeding, and those with severe disease may ultimately need parenteral nutrition. The decision to initiate the latter is primarily clinical; however, imaging is a useful confirmatory tool and has an important role in excluding other causes of weight loss and malnutrition, such as malignancy. Surgical options are poorly tolerated, and should be generally avoided, unless absolutely indicated (e.g. in rectal prolapse, volvulus). Response to novel therapies such as immunosuppression and neural stimulation have so far produced mixed results and need further evaluation.5,10

Organ-specific pathology and imaging

Oesophagus

The oesophagus is the most commonly affected internal organ in SSc, affecting 70%–90% of patients. 4 The distal two thirds of the oesophagus are involved, with smooth muscle fibrosis and atrophy leading to dilation, decreased peristalsis and hypotensive lower oesophageal sphincter (LES). Symptoms are primarily related to acid reflux, regurgitation and dysphagia, which for some patients are the earliest disease indicators. Other oesophageal reflux related symptoms in scleroderma patients include chronic cough, voice hoarseness, pharyngitis, laryngospasm and asthma. Severe and long-standing reflux disease (gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)) can lead to peptic stricture formation and Barrett’s oesophagus, and this could potentially progress to oesophageal adenocarcinoma. 11 Another complication of long-standing oesophageal dysmotility is the development of interstitial lung disease due to microaspiration. 12 About 30% of patients with oesophageal involvement will remain asymptomatic, posing a diagnostic challenge to the treating physician and should not be overlooked. 13

The classic chest radiograph of a patient with SSc demonstrates oesophageal dilatation of the lower oesophagus to the level of the aortic arch, and there may be shortening of the oesophagus due to fibrosis. There may be additional lung pathology, with radiological signs of aspiration pneumonia and fibrotic changes of scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD). Radiographic features of pulmonary hypertension may or may not be present (Figure 2).

Fluoroscopy with barium swallow demonstrates a dilated tubular, aperistaltic oesophagus (above the aortic arch peristalsis remains normal) with a patulous LES (Figure 3). The main imaging differential for oesophageal dilatation is achalasia, which also results in oesophageal dysmotility but is characterized by impaired relaxation of the LES (Figure 3). Both conditions result in oesophageal dilatation. In achalasia, however, the dilatation can affect the entire oesophagus, as opposed to the predominantly distal dilatation in scleroderma. In the former, there is an abrupt focal narrowing distally (bird beak sign) and there may be pooling of barium in the lower oesophagus as a result of the hypertonic LES. In scleroderma the gastro-oesophageal junction is widened, and the contrast medium may be seen quickly emptying into the stomach and there may be also regurgitation back to the oesophagus.

Figure 3.

Fluoroscopy images from barium swallow studies showing oesophageal dilatation: (a) In a 42-year-old man with scleroderma, with a patulous gastroesophageal junction (black arrow) in addition to extensive lung changes caused by SSc-ILD (white arrow), and (b) in a patient with achalasia, with a tight focal narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction (black arrow).

Fluoroscopy can be used in the assessment of structural abnormalities such as strictures or diverticula. It may also facilitate assessment of mucosal pathology such as reflux and candida oesophagitis, which may occur as a result of poor oesophageal emptying and immunosuppression. In combination with upper GI endoscopy, it aids the diagnosis and characterization of structural abnormalities.

Reflux oesophagitis is common (70%) 14 and can progress to complications such as erosions, superficial ulcers and fusiform strictures, identifiable on fluoroscopy. Acid reflux has also been implicated in the development of SSc-ILD9,15 and given the high mortality of this, acid reflux management should be initiated early. The rate of Barrett’s metaplasia is estimated to be 12%, which is similar to that of the non-SSc GERD patients (Figure 4); however, there might be increased risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma, as suggested in a recent European cohort. 13

Figure 4.

(a) Sagittal and (b) axial post-contrast CT images in a 64-year-old woman with scleroderma demonstrating a dilated oesophagus (black arrow) with circumferential wall thickening, endoscopically proven to be Barrett’s metaplasia, and (c) axial images (lung windows) from the same patient showing SSc-ILD.

It is likely that a patulous LES combined with a hypomotile oesophagus increases oesophageal acid contact time, so prompt and effective acid control is imperative both for symptomatic relief and also for reducing GERD complications.

Stomach

Gastric involvement in SSc manifests as gastroparesis and gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE). Gastric involvement is not as common as oesophageal, anorectal, small and large bowel disease. Gastroparesis is a result of autonomic dysfunction and causes gastric dilatation and delayed gastric emptying 5 (Figure 5). Patients complain of early satiety, bloating, nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness and abdominal pain. GERD may be aggravated. 13 GAVE usually presents as iron deficiency anaemia and less commonly with acute upper GI bleeding.4,16 Its pathophysiology is related to immune-mediated vasculopathy and is similar to the mechanisms underlying telangiectasias and Raynaud’s phenomenon. 17 The diagnosis is endoscopic.16,18

Figure 5.

Coronal CT image from a 67-year-old female patient with scleroderma and anaemia, demonstrating a markedly dilated stomach.

The role of imaging in gastric involvement in scleroderma is primarily to exclude other causes of gastric outlet obstruction. Barium swallow may point to a dilated, atonic stomach and gastric emptying scintigraphy establishes the diagnosis. 19

Dietary modification alongside prokinetic agents are the mainstay of treatment for gastroparetic patients. 5 GAVE is treated conservatively, with iron supplementationl and blood transfusions, or endoscopically with argon plasma coagulation (APC) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA).17,20

Small bowel

The small bowel is the third most commonly affected organ in SSc. Clinical symptoms are mainly due to small intestinal dysmotility. Reduced gastric acid production, as a result of PPI (proton pump inhibitors) use, also contributes to resulting pathology. Small bowel manifestations include small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIPO) and malnutrition, and less commonly pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, jejunal diverticula and small bowel volvulus. Patients complain mainly of abdominal pain and bloating and may have diarrhoea as a result of malabsorption and SIBO. 21

Small bowel dysmotility is the result of a range of myogenic and neurogenic factors, alongside with vasculopathy and vascular ischaemia that leads to muscle atrophy and irreversible bowel wall fibrosis. 17 Impairment in motility results in stasis of luminal contents, dilation of bowel lumen and secondary SIBO. 21 Malabsorption frequently ensues, which is a poor prognostic indicator, with 50% mortality at 8.5 years. 10 Radiological findings are nonspecific and include the small bowel faeces sign, which is observed on cross-sectional imaging and describes faecalisation of small bowel contents due to delayed intestinal transit, bacterial overgrowth and increased water absorption in the small bowel.18,22 This finding is also seen with other causes of slow transit such as chronic strictures in Crohn’s disease.

Bowel wall fibrosis and abnormal peristalsis cause luminal dilatation. Intestinal loops appear distended on plain abdominal radiographs, and this is most prominent in the second and third part of the duodenum and proximal jejunum (Figure 6). Progression to ‘megaduodenum’ is a rare complication, and a luminal diameter of up to 8 cm has been described in the literature. 23 Other differentials for duodenal dilatation include malrotation, volvulus and superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome. Imaging has a key role in distinguishing between these potential causes. In scleroderma, there is duodenal and jejunal dilatation, with no transition point seen in the duodenum (Figure 7).

Figure 6.

(a) Barium follow through and (b) coronal and (c) axial post-contrast CT images from a 68-year-old female patient with scleroderma showing dilatation of the duodenum (black arrow).

Figure 7.

Patient with scleroderma showing (a) dilatation of the duodenum and jejunum. Compare this to the image in (b) from a water soluble contrast study in a 24-year-old man presenting with severe vomiting due to obstruction, secondary to malrotation. There is a marked transition point between the dilated duodenum and collapsed jejunal loops.

A pathognomonic imaging feature of scleroderma on a barium study is the ‘hide bound’ or ‘accordion’ sign. 24 The characteristic appearance of proximal small bowel is a result of tightly packed valvulae conniventes of normal thickness (despite luminal dilation), and asymmetric atrophy and fibrosis of the inner circular muscle layer with contraction of the outer longitudinal one (Figures 8 and 9). Normal jejunal fold pattern is 4–7 folds per inch, and greater than 7 folds in the context of jejunal dilatation is consistent with a fibrosed ‘hidebound’ bowel and raises the suspicion of scleroderma.15,18,25 These findings differentiate it from other diseases affecting the small bowel, such as coeliac disease, which shows bowel wall thickening and increased fold spacing in the jejunum (Figure 10).

Figure 8.

(a) Abdominal radiograph and (b) image from barium follow-through study from two patients with scleroderma demonstrating dilated small bowel loops with tightly packed jejunal folds.

Figure 9.

Scleroderma jejunal fold pattern on axial and coronal post-contrast CT images from a 68-year-old female with scleroderma. Tightened jejunal folds are likened to an accordion or stack of coins.

Figure 10.

(a) Axial and (b) coronal post-contrast CT in a 75-year-old female patient with scleroderma, demonstrating dilated bowel loops with tightly packed jejunal folds. The small bowel faeces sign is also noted. (c) Axial and (d) coronal post-contrast CT showing thickened bowel walls with increased fold spacing in a 74-year-old female patient with coeliac disease.

Asymmetric fibrosis in one side of the bowel wall results in wide-mouthed diverticula on the uninvolved side, classically detected on the antimesenteric border of the jejunum.18,26 They are relatively specific for scleroderma and are commonly an incidental finding (Figure 11). They are usually asymptomatic, but occasionally they can perforate and also promote bacterial overgrowth. 13

Figure 11.

Images from 61-year-old patient with scleroderma: (a) barium follow-through study and (b) coronal post-contrast CT demonstrating a large wide-mouthed diverticulum arising from the third part of the duodenum.

Scleroderma is a frequent cause of CIPO and results from the culmination of dilatation and reduced motility. 27 Diagnosis is confirmed by cross-sectional imaging, where there is small or large bowel dilatation in the absence of a transition point. Fluoroscopic studies additionally demonstrate delayed transit times. Other causes of chronic small bowel obstruction can cause similar appearances, but a site of transition from dilated to collapsed bowel is usually identified at the site of obstruction (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

(a) Coronal T2 image from an MR enterography study in a 21-year-old female patient with Crohn’s disease showing chronic small bowel dilatation with focal strictures (arrows) and (b) Coronal T2 image from an MR enterography of a 62-year-old scleroderma patient demonstrating dilated bowel loops, affecting the entire small bowel with no focal transition point.

Transient intussusceptions may also be observed and are associated with chronic distention and reduced motility. They are common incidental findings, which do not require surgical intervention; there is no lead point and they resolve spontaneously (Figure 13). Awareness of the appearances of both intussusception and pseudo-obstruction is imperative as management is radically different, with conservative, rather than surgical treatment indicated. Surgery should generally be avoided and is indicated in the event of bowel wall perforation or necrosis. 27

Figure 13.

(a) Coronal and (b) axial images from a CT following intravenous and oral contrast in a 70-year-old woman showing a jejunojejunal intussusception. (c) Axial post-contrast CT image from a 48-year-old man with scleroderma demonstrating jejunojejunal intussusception. This resolved on subsequent imaging.

Pneumatosis intestinalis (PI) is a less common complication of bowel involvement in SSc. It is characterized by air-filled cysts within the intestinal wall and is a result of gas production from bacterial overgrowth and concomitant mucosal atrophy. Progressive gaseous distension of the bowel due to bacterial fermentation causes increased intraluminal pressure. Tiny mucosal lesions allow gas lobules to accumulate in the gut wall resulting in a linear, cystic appearance5,28 (Figure 14). It is a rare radiographic diagnosis with characteristic images of both small bowel and colon. Radiolucent air-filled cysts can be seen in the submucosal and subserosal layers. 29 They are asymptomatic, but they can rupture and result in benign pneumoperitoneum 13 (Figure 15). PI is not confined to scleroderma and has been observed in a range of conditions, from more benign entities such as scleroderma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), mechanical ventilation and inflammatory bowel disease to life-threatening conditions such as intestinal ischaemia. 28 The presence of ascites, vascular occlusion, wall thickening and portal venous gas should raise the suspicion of a more life-threatening cause, such as mesenteric ischaemia. However, it should be remembered that PI is a sign rather than a disease and clinical findings are the most important factors in determining the cause.

Figure 14.

(a) Coronal and (b) axial images from a post-contrast CT scan demonstrating large bowel dilatation with loss of haustra and pneumatosis intestinalis consistent with pseudo-obstruction, in a 67-year-old female patient with scleroderma.

Figure 15.

(a) Abdominal radiograph, (b) erect chest radiograph and (c) axial CT on lung windows demonstrating extensive free gas (arrows) in a 67-year-old woman with scleroderma.

Colon

Colonic involvement in scleroderma results from collagen deposition in the mucosal and submucosal layers, atrophy of the muscularis externa and loss of the gastro-colic reflex. Findings frequently mirror those in the small bowel, with the presence of colonic dilatation, wide-mouthed diverticula and signs of pseudo-obstruction (Figures 14, 16 and 17). Patients present with abdominal distension, pain, constipation or diarrhoea. 5

Figure 16.

Abdominal radiograph of a 69-year-old female with scleroderma demonstrating colonic pseudo-obstruction.

Figure 17.

Coronal image from a post-contrast CT demonstrating wide-mouthed colonic diverticula on the antimesenteric border.

A characteristic radiological finding is colonic dilatation, which can be marked and Hirschprung-like, with complete loss of haustrations occuring later on, causing appearances similar to ulcerative colitis. Wide-mouthed diverticula are common and are usually found on the antimesenteric border of the transverse and descending colon 15 (Figure 17). Colonic transit time is prolonged as demonstrated by radiopaque markers studies. 11 Other complications of colonic involvement include transverse and sigmoid colonic volvulus, megacolon and stenosis. Plain radiographs or computerized tomography can point to the correct diagnosis and can aid to exclude presence of mechanical obstruction. 12 Telangiectasias, stercoral ulceration and endoluminal causes of constipation are diagnosed endoscopically.

Anorectal

Anorectal involvement is the second most common site of GI involvement in scleroderma, following oesophagus. Up to 70% of patients present with anorectal symptoms, namely incontinence, constipation, tenesmus and painful defaecation. 30 Faecal incontinence occurs in up to a third of patients and is a result of constipation with overflow, diarrhoea due to malabsorption, rectal prolapse, internal anal sphincter dysfunction or reduced rectal compliance. 13 Collagen deposition and vascular alterations lead to muscular and neural dysfunction 31 with resultant low anal sphincter resting pressure, disruption of anal inhibitory reflex and reduced rectal compliance. Neuropathic changes are particularly important in the anorectum given the central role of rectoanal inhibitory reflexes in maintaining normal continence. 32

Endoanal ultrasound is the best modality to assess internal anal sphincter integrity allowing anatomical visualization of the anal sphincter complex. Thin-slice endoanal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can also be used to assess sphincter anatomy. The internal anal sphincter is composed of smooth muscle, and changes here reflect those observed in the LES. Internal anal sphincter atrophy results in low resting tone and ultimately passive faecal incontinence. 32 A thinned, atrophic internal sphincter with ventral buckling of the anterior rectal wall is observed even in asymptomatic patients 30 (Figure 18). An altered contrast enhancement profile of the sphincter reflects degrees of fibrosis. 30 Incomplete defaecation also occurs and consequently stercoral ulceration from retained faecal material is occasionally seen. Patients are also at risk of associated rectal prolapse. Sacral nerve stimulation has been shown to be a safe treatment for faecal incontinence in these patients, though its efficacy is mixed.32,33

Figure 18.

Coronal T2 weighted MRI showing atrophy of (a) low rectal circular smooth muscle in a 59-year-old woman with scleroderma. Compare with (b) normal circular smooth muscle.

Conclusion

GI involvement in SSc is the most common visceral manifestation of the disease. In many cases, radiological findings precede clinical manifestations and in this setting the role of radiologist is crucial for early disease recognition. Subsequent detection of the various GI complications is vital for treatment, and imaging alongside clinical assessment forms the mainstay for diagnosis. Table 1 summarizes the main radiological findings in GI involvement in SSc. Combination of the different diagnostic modalities allows for more accurate assessment and better patient care.

Table 1.

Scleroderma GI involvement correlated with pathological site and imaging findings.

| Site | Pathology | Modality | Imaging finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oesophagus | Lower oesophageal dysmotility and dilatation Reflux |

Radiograph Fluoroscopy CT |

Distal oesophageal dilatation Patulous GOJ Oesophagitis Strictures |

| Stomach | Dilatation Poor gastric emptying GAVE |

Radiograph Fluoroscopy CT Gastric Emptying Study |

Gastric dilatation in the absence of an obstructive

cause Delayed transit |

| Small bowel | Dilatation with tightly packed valvulae

conniventes SIBO |

Radiograph Fluoroscopy CT MR enterography |

Small bowel faeces Dilated bowel loops Crowding of jejunal folds Intussusception Diverticula |

| Large bowel | Pseudo-obstruction Pneumatosis intestinalis |

Radiograph Fluoroscopy CT MR |

Dilated, ahaustral

bowel Pneumatosis Pneumoperitoneum |

| Anorectal | Internal anal sphincter atrophy | MRI | Ventral deviation of the anterior rectal wall Thinned internal sphincter Sphincter enhancement Rectal prolapse |

GI: gastrointestinal; CT: computed tomography; GOJ: gastro oesophageal junction; GAVE: gastric antral vascular ectasia; SIBO: small intestinal bacterial overgrowth; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Stamatia-Lydia Chatzinikolaou  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3157-8967

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3157-8967

References

- 1. Chifflot H, Fautrel B, Sordet C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2008; 37(4): 223–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Denton CP, Black CM. Scleroderma: clinical and pathological advances. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2004; 18(3): 271–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta RA, Fiorentino D. Localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis: is there a connection. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007; 21(6): 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forbes A, Marie I. Gastrointestinal complications: the most frequent internal complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2009; 48(Suppl. 3): 36–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Domsic R, Fasanella K, Bielefeldt K. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53: 1163–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sollberg S, Mauch C, Eckes B, et al. The fibroblast in systemic sclerosis. Clin Dermatol 1994; 12(3): 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thoua NM, Derrett-Smith EC, Khan K, et al. Gut fibrosis with altered colonic contractility in a mouse model of scleroderma. Rheumatology 2012; 51(11): 1989–1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raja J, Nihtyanova SI, Murray CD, et al. Sustained benefit from intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2016; 55(1): 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raghu G, Freudenberger TD, Yang S, et al. High prevalence of abnormal acid gastro-oesophageal reflux in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2006; 27: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gyger G, Baron M. Systemic sclerosis: gastrointestinal disease and its management. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2015; 41(3): 459–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hansi N, Thoua N, Carulli M, et al. Consensus best practice pathway of the UK scleroderma study group: gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014; 32(6 Suppl. 86): S-214–S-221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Frech TM, Mar D. Gastrointestinal and hepatic disease in systemic sclerosis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2018; 44(1): 15–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kumar S, Singh J, Rattan S, et al. Review article: pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of gastrointestinal systemic sclerosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017; 45(7): 883–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Federle M. Scleroderma, esophagus. In: Federle M, Jeffrey RB. (eds) Diagnostic imaging: abdomen (Diagnostic Imaging Series), vol. VII, no. (1). 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys, 2010, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khanna D, Nagaraja V, Gladue H, et al. Measuring response in the gastrointestinal tract in systemic sclerosis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013; 25(6): 700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stern EP, Denton CP. The pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2015; 41: 367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McFarlane IM, Bharma MS, Kreps A, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2018; 8(1): 2–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chapin R, Hant FN. Imaging of scleroderma. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2013; 39: 515–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blackwell JN, Hannan WJ, Adam RD, et al. Radionuclide transit studies in the detection of oesophageal dysmotility. Gut 1983; 24(5): 421–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Magee C, Lipman G, Alzoubaidi D, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for patients with refractory symptomatic anemia secondary to gastric antral vascular ectasia. United Eur Gastroenterol Journal 2018; 7(2): 217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tauber M, Avouac J, Benahmed A, et al. Prevalence and predicators of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2014; 32: 82–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fuchsjäger MH. The small-bowel feces sign. Radiology 2002; 225: 378–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Contreras R, Hernández JR. Megaduodenum in Systemic Sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: e20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Horowitz AL, Meyers MA. The ‘hide-bound’ small bowel of scleroderma: characteristic mucosal fold pattern. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 119(2): 332–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Federle M, Jeffrey RB. Scleroderma: diagnostic imaging: abdomen (Diagnostic Imaging Series), vol. VII, no. (1). 2nd ed. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys, 2010, pp. 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coggins CA, Levine MS, Kesack CD, et al. Wide-mouthed sacculations in the esophagus: a radiographic finding in scleroderma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176(4): 953–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shreiner AB, Murray C, Denton C, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic sclerosis. J Scleroderma Relat Disord 2016; 1(3): 247–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ho LM, Paulson EK, Thompson WM. Pneumatosis intestinalis in the adult: benign to life-threatening causes. Am J Roentgenol 2007; 188(6): 1604–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kinjo M. Lurking in the Wall: Pneumatosis Cystoides Intestinalis with scleroderma. Am J Med 2016; 129(4): 382–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. deSouza NM, Williams AD, Wilson HJ, et al. Fecal incontinence in scleroderma: assessment of the anal sphincter with thin-section endoanal MR imaging. Radiology 1998; 208(2): 529–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Savarino E, Furnari M, de Bortoli N, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis. La Presse Méd 2014; 43: 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Thoua NM, Schizas A, Forbes A, et al. Internal anal sphincter atrophy in patients with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology 2011; 50(9): 1596–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Butt SK, Alam A, Cohen R, et al. Lack of effect of sacral nerve stimulation for incontinence in patients with systemic sclerosis. Colorectal Dis 2015; 17(10): 903–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]