Abstract

Objectives:

The objective of this study was to systematically review the mortality and morbidity associated with scleroderma renal crisis and to determine temporal trends.

Methods:

We searched MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews from database inception to 10 February 2020. Bibliographies of selected articles were hand-searched for additional references. Data were extracted using a standardized extraction form. Study quality was assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Results were analysed qualitatively.

Results:

Twenty studies with 14,059 systemic sclerosis subjects, of which 854 had scleroderma renal crisis and 4095 had systemic sclerosis–associated end-stage renal disease, met inclusion criteria. Study quality was generally moderate. Cumulative mortality in the post-angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor era was approximately 20% at 6 months, 30%–36% at 1 year, 19%–40% at 3 years and almost 50% at 10 years from scleroderma renal crisis onset. Although the introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in the early 1970s resulted in a 50% improvement in scleroderma renal crisis mortality, there was no further improvement thereafter. Scleroderma renal crisis mortality rates were proportionally higher than mortality rates associated with other systemic sclerosis organ involvement. The rate of permanent dialysis after scleroderma renal crisis in the post-angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor era ranged from 19%–40%. Three to 17% of systemic sclerosis patients underwent renal transplant. Survival was better in patients post-renal transplant (54%–91%) compared to those on dialysis (31%–56%). Graft survival improved over time and appeared similar to that of patients with other types of end-stage renal disease.

Conclusion:

While there has been considerable improvement in scleroderma renal crisis–related outcomes since the introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, morbidity and mortality remain high for affected patients without convincing evidence of further improvement in the post-angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor era. Novel treatments are required to improve outcomes of scleroderma renal crisis.

Keywords: Mortality, morbidity, scleroderma renal crisis, systemic sclerosis, autoimmune diseases

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare autoimmune disease with the highest cause-specific mortality rate among the rheumatic diseases. 1 The standardized mortality ratio (SMR) has been estimated to be over 4, and 5-year survival rates range from 50% to 90%, depending on the time of the study and the population selected.2–5 Main contributors to the high mortality include visceral organ involvement, especially pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), interstitial lung disease (ILD) and, historically, scleroderma renal crisis (SRC).6–8 In the past few decades, there has been progress in the detection and treatment of SSc organ involvement, leading to improvement of organ-specific prognosis. Several drugs for PAH have demonstrated improvement in hemodynamic measures, functional capacity and quality of life in SSc.9–11 Similarly in ILD, immunosuppressive agents have shown benefit in stabilization of lung function and improvement in symptoms and quality of life.12–14 Whether these treatments translate into improved cause-specific or overall SSc survival remains uncertain.15,16 On the other hand, the introduction of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in the early 1970s resulted in marked improvement in SRC-associated mortality and morbidity. 8

SRC is a life-threatening complication of SSc, characterized by malignant hypertension and acute kidney injury. It can also be associated with microangiopathic hemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia and target organ dysfunction (retinopathy, cardiomyopathy and encephalopathy). Historically, SRC was managed with various immunosuppressive agents, occasionally dialysis, if available, plasma exchange, nephrectomy and renal transplant. Nevertheless, it was almost universally and rapidly fatal.8,17 The introduction of ACE inhibitors resulted in marked improvement in clinical outcomes, and ACE inhibitors are now recommended as first-line treatment in SRC. 18

Despite the undisputed improvement in outcomes of SRC since the availability of ACE inhibitors, estimates of mortality and morbidity vary considerably. In this systematic review, our objectives were to identify, appraise and synthesize the evidence on mortality and morbidity associated with SRC and non-SRC renal disease, and to identify temporal trends.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was performed using a pre-defined protocol registered in the PROSPERO database (#CRD42019121237), and the results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Eligibility criteria

Types of studies

We screened published, full-length manuscripts reporting original data on human subjects and restricted language to English. Due to the high risk of selection bias in case reports, we selected studies of all types that reported on at least 20 or more study patients.

Types of participants

All participants had a diagnosis of SSc and either SRC or non-SRC renal disease related to SSc. Data on subjects with overlapping connective tissue diseases were excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcomes were mortality and morbidity. Mortality was reported using various measures, including mortality and survival rates. Morbidity included rates of dialysis and renal transplantation. Studies that did not provide sufficient information to estimate SRC- or non-SRC-specific mortality, survival or morbidity rates were excluded.

Information sources and search

MEDLINE, Embase and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews were searched from database inception to 10 February 2020. The complete search (Supplemental Table 1) was developed with the assistance of a professional librarian. We also hand-searched references of selected papers to identify additional studies addressing our topic.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers (H.K. and F.L.) screened titles and abstracts using a standardized form. When there was discrepancy, the study in question was included in the full-length text review. One reviewer (H.K.) screened full-length papers for the final selection of eligible studies. If more than one study was published with the same patient cohort, we included the publication that encompassed the longest duration or the largest sample.

Data extraction and data items

Data extraction was performed using a standardized data extraction form to collect the following information: (1) study identification and characteristics (geographic location, time period, design, sample size, criteria used to define SSc and follow-up time), (2) characteristics of study patients (age, sex, ethnicity, SSc subtype, disease duration, autoantibody profiles and clinical manifestations of SSc), (3) characteristics of renal disease (SRC vs non-SRC renal disease, definition of SRC or renal disease, subtypes of SRC (hypertensive, normotensive), clinical and laboratory manifestation of renal disease, disease duration from SSc diagnosis to SRC onset and follow-up time after SRC onset), (4) outcomes (mortality, survival, dialysis, renal transplant, renal recovery and dialysis discontinuation, time to renal recovery and graft survival post-renal transplant).

Definition of study designs

Study designs were classified using the following definitions:

Case series: a study in which SRC cases were presented without a comparison group;

Retrospective cohort studies: a study in which the data on SRC were collected retrospectively with a comparison group from the same cohort;

Prospective cohort studies: a study in which the data on SRC were collected prospectively with a comparison group from the same cohort.

Risk of bias assessment

The cohort studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies. The maximum attainable score was 9, with a maximum of 4 points for the selection category, 2 points for the comparability category and 3 points for the outcome category. 19 For the purpose of risk of bias assessment, the exposure was set as SRC or non-SRC renal disease and the outcome of interest was mortality or morbidity. No points were given if the primary exposure or the outcome in the study were not consistent with our definitions. There is no standard risk of bias tool for case series. They are usually considered at high risk of bias due to the risk of selection bias and the lack of a comparison group. However, we only included those with 20 or more study patients to mitigate this possible bias.

Statistical analysis

Data were extracted, summarized in tabular form and analysed descriptively. Heterogeneity in study designs and reported outcomes precluded further quantitative analyses.

Study types included cohort studies (retrospective and prospective) and case series, with variable follow-up duration, ranging from 6 months to over 13 years. Mortality outcomes were reported as either mortality rate or survival rate and, in some cases, estimated from the number of cause-specific death reported. Morbidity outcomes were even more variable, including range of renal replacement therapies and different measures for renal recovery. The studies were first grouped based on the type of reported outcomes. Then, they were further grouped based on the follow-up periods for meaningful comparisons. Only two to three studies remained in each group, and qualitative analyses were deemed more valuable.

Results

Study selection

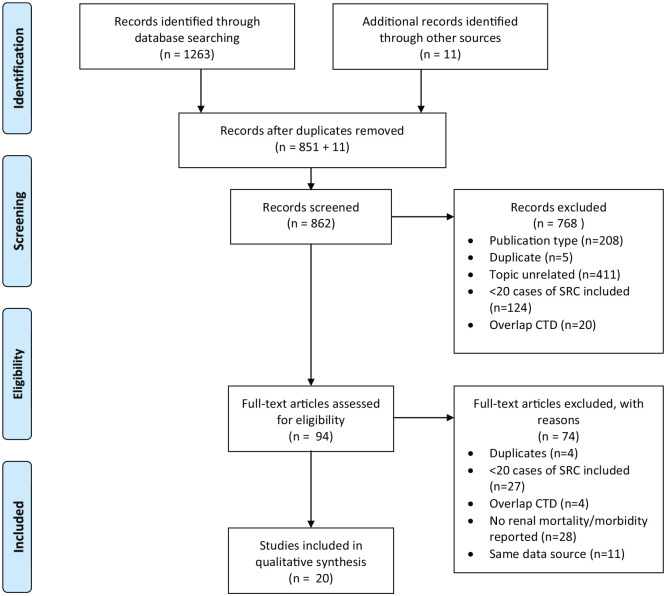

The search results and the reasons for exclusion are summarized in Figure 1. The electronic search identified 1263 potentially relevant papers. We also performed a hand-search of references in selected papers and identified 11 additional studies. After removal of duplicate papers (n = 412), ineligible papers based on title and abstract review (n = 768) and after full-text review (n = 74), a total of 20 studies were selected for inclusion in this systematic review. Thirteen studies were retrospective cohort studies, one was a prospective cohort study and six were case series. Twelve studies reported SRC outcomes, seven studies reported SSc-associated end-stage renal disease (ESRD) data from dialysis or transplant registries, and one study reported on non-SRC renal disease. Overall, 14,059 SSc subjects were included, of which 854 had SRC, 4095 had SSc-ESRD and 173 had non-SRC renal disease. All cohort studies were of medium quality with the NOS score ranging from 3 to 5,4,5,17,20–27 except two studies with a score of 628,29 and another study with a score of 2. 30

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

SRC-associated mortality

Twelve studies were included in this analysis: 11 studies reported on mortality over varying time periods (range: 6 months–9.6 years),4,5,8,17,20–22, 28,31–33 3 studies reported both mortality and survival rates,22,28,33 while one study only reported survival rates in SRC. 34 All studies reflected the usual epidemiology of SSc patients, with the proportion of females ranging from 66.7% to 89.2% and most patients being middle aged (40.6–55 years old). The proportion of diffuse cutaneous SSc subtype was 22%–40.3% in the overall SSc group, while it was 74.4%–97.2% in the SRC groups (Table 1).4,5,8,17,20–22, 28,31–34

Table 1.

Description of studies included in SRC mortality and morbidity analysis.

| Study | Design | Country | Inclusion period | SSc, N | SSc-SRC, N | Female, n (%) | Age, yearsab | Mortality/survival data | Morbidity data | Quality assessment score (maximum 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubio-Rivas et al. 20 | Retrospective cohort | Spain | 1955–2018 | 1625 | 39/1613 | 1447 (89.0) | 45.5 (16.4) | Y | N | 5 |

| Hao et al. 5 | Retrospective cohort | Australia, Canada and Spain | Australia 2007–2014, Canada 2005–2014, Spain 2000–2014 | 1070 inception cohort | 62 | 882 (82.4) | 51.7 (13.8) | Y | N | 3 |

| 3218 prevalent cohort | 128 | 2780 (86.4) | 45.9 (14.2) | |||||||

| Chighizola et al. 31 | Case series | United Kingdom | Not provided | 20 | 20 | 14 (70.0) | . | N | Y | c |

| Hudson et al. 21 | Prospective cohort | International | 2010–2012 | 75 | 75 | 50 (66.7) | 52.5 (12.2) b | Y | Y | 4 |

| Sampaio-Barros et al. 4 | Retrospective cohort | Brazil | 1991–2010 | 947 | 25 | 838 (88.5) | 42.6 (14.1) | Y | N | 4 |

| Cozzi et al. 32 | Case series | Italy | 1980–2005 | 20 | 20 | 14 (70.0) | 49 (12.1) | Y | Y | c |

| Guillevin et al. 22 | Retrospective cohort | France | Unknown | . | 91 | 69 (75.8) | 50 (15) b | Y | Y | 4 |

| 427 | . | 353 (82.7) | 55 (16) b | |||||||

| Codullo et al. 34 | Case series | Italy | 1987–2007 | 46 | 46 | 38 (82.6) | 52.8 (13.2) | Y | Y | c |

| Penn et al. 33 | Case series | United Kingdom | 1990–2005 | 110 | 110 | 87 (79.1) | 50.7 (range, 24–80) 55 (16) b |

Y | Y | c |

| Steen and Medsger 28 | Retrospective cohort | United States | 1979–1996 | 807 | 145 | 109 (75.2) | 50 at SRC onset | Y | Y | 6 |

| Traub et al. 8 | Case series | United States | 1955–1981 | 824 | 68 | 48 (70.5) | . | Y | Y | c |

| LeRoy and Fleischmann 17 | Retrospective cohort | United States | 1970–1975 | 100 | 25 | 22 (88.0) | 42 (range, 19–61) b | Y | Y | 3 |

SRC: scleroderma renal crisis; SSc: systemic sclerosis; SD: standard deviation.

Values are mean ± SD or (range), at disease onset.

If age at disease onset was not available, age at diagnosis was used.

No quality assessment was done for case series; considered as high risk of bias.

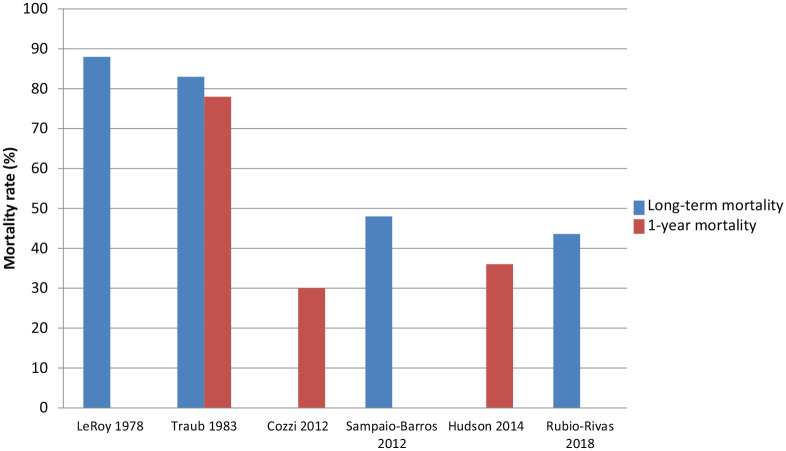

Mortality rates associated with SRC ranged widely between studies from 13%5,22 to 88% 17 (Table 2 and Figure 2). Heterogeneity in time period of data collection, sample selection, and follow-up time precluded pooling of the data. Instead, data were analysed descriptively, as follows.

Table 2.

SRC-associated mortality and survival rates.

| Study | Cohort | SSc, N | SSc-SRC, N | SSc subtypes, n (%) | Follow-up, years a | Time from diagnosis to SRC onset, years a | Overall SSc mortality, n (%) | SRC death, n (%) | Survival rates | Mortality rate from other organ involvement | Conclusion – SRC mortality | Definition of SRC mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubio-Rivas et al. 20 | 1625 | 39 | DcSSc: 350 (21.6), LcSSc: 968 (59.7), Sine SSc: 180 (11.1), Early or pre-SSc 124 (7.6) | 8.1 (7.7) | 4.4 ± 8.3 in RP onset subgroup 6.5 ± 10.9 in non-RP onset subgroup b |

277 (17.0) | 17/39 (43.6) | ILD 32/675 (4.7%); PH defined by ECHO or RHC 43/311 (13.8%); PAH defined by RHC 43/119 (36.1%) | 43.6% over 8.1 years of follow-up | Deaths due to SRC | ||

| Hao et al. 5 | Inception cohort | 1070 | 62 | DcSSc: 431 (40.3), LcSSc: 622 (58.1), Sine SSc: 0 | Median 3.0 (IQR 1.0–5.2) | 140 (13.1) | 12/62 (19.4) | ILD 18/264 (6.8%); PAH 22/58 (37.9%); PAH + ILD 8/15 (53%); myocardial involvement 13/45 (28.9%); GI 12/684 (1.8%) | 19.4% over 3 years of follow-up | SRC as a principal cause of death | ||

| 29% over 3 years of follow-up | SRC as a principal or contributing cause of death | |||||||||||

| Prevalent cohort | 3218 | 128 | DcSSc: 1006 (31.3), LcSSc: 2086 (64.8) | 3.1 (1.0–5.2) | 440 (13.7) | 17/128 (13.3) | ILD 53/719 (7.4%); PAH 88/240 (36.7%); PAH + ILD 32/78 (41.0%); myocardial involvement 22/184 (12.0%); GI 24/2157 (1.1%) | 13.3% over 3 years of follow-up | SRC as a principal cause of death | |||

| 21% over 3 years of follow-up | SRC as a principal or contributing cause of death | |||||||||||

| Hudson et al. 21 | 75 | 75 | DcSSc: 56 (74.4), LcSSc: 16 (21.3), Sine SSc: 3 (4.0) | 1 | Median 1.5 (IQR 0.9–3.7) | 27/75 (36.0) | No comparator group | 36% in the first year after SRC onset | All deaths after SRC | |||

| Sampaio-Barros et al. 4 | 947 | 25 | DcSSc: 294 (31.0), LcSSc: 533 (56.4), Sine SSc: 79 (8.3), Overlap: 41 (4.3) | 9.6 (7.7) | 168 (17.7) | 12/25 (48.0) | ILD 18/538 (3.3%); PH 18/221 (8.1%); ILD + PH 17/132 (12.9%); GI 5/897 (0.6%); heart failure 20/111 (18.0%); arrhythmia 7/111 (6.3%) | 48% over 9.6 years | Deaths due to SRC | |||

| Cozzi et al. 32 | 20 | 20 | DcSSc: 16 (80.0), LcSSc: 4 (20.0) | 1 year minimum | 3.7 (4.8) | 6/20 (30.0) within 1 year | Survival 50% at 5 years | Not reported | 30% in the first year after SRC onset | Deaths due to SRC and SRC treatment | ||

| Guillevin et al. 22 | 518 | 91 | DcSSc: 78 (85.7), LcSSc: 13 (14.2) | 3.8 (5.1) | 3.2 (8.1) | 37/91 death overall (40.7); 12 of 37 (13.2%) death due to SRC | Survival 70.9%, 66.6%, 60% and 41.9% at 1, 2, 5 and 10 years. Dialysis-free survival 55.3%, 44.4% and 33.7% at 1, 2 and 5 years | Organ-specific mortality not reported. Mortality of controls (427 SSc without SRC) 46/427 (10.8%) over 79 months of follow-up | 20.9% over 6 months after SRC onset, 40.7% over 3.8 years after SRC onset | All deaths after SRC | ||

| 13.2% SRC-specific mortality over 3.8 years of follow-up | Deaths related to SRC and SRC treatment | |||||||||||

| Codullo et al. 34 | 46 | 46 | DcSSc: 40 (87.0), LcSSc: 6 (13.0) | Median 1 (range 0–16.5) | Cumulative survival 64%, 53%, 40% and 35% at 1, 2, 5 and 10 years; median survival from onset of SRC 3 (0.7–5.3) years | No comparator group | ||||||

| Penn et al. 33 | 110 | 110 | DcSSc: 86 (78.2), LcSSc: 24 (21.8) | Median 3.1 (range 0–14.7) | Median 0.6 (range 0–16.7) | 44/110 (40.0) | Survival 82%, 74%, 71%, 59% and 47% at 1, 2, 3, 5 and 10 years | No comparator group | 40% over 3.1 years of follow-up | All deaths after SRC | ||

| Steen and Medsger 28 | 807 | 145 | DcSSc: 141 (97.2), LcSSc: 4 (2.8) | 5–10 years | Median 2.4 | 28/145 (19.3) | Cumulative survival in no-dialysis or temporary dialysis groups: 90% at 5 years, 80%–85% at 8 years | No comparator group | 19.3% over 6 months after SRC onset | All deaths after SRC | ||

| Traub et al. 8 | 68 | 68 | Average 3.0 (3.2) | 57/68 (83.8); 53 within 1 year (78.0) | No comparator group | 83.3% overall; 78.0% over 1 year after SRC onset | All deaths after SRC | |||||

| LeRoy and Fleischmann 17 | 100 | 25 | 22 (88.0) | SSc without renal failure 19/75 (25.3%) | 88% overall | All deaths after SRC |

SRC: scleroderma renal crisis; SSc: systemic sclerosis; DcSSc: diffuse cutaneous SSc; LcSSc: limited cutaneous SSc; RP: Raynaud phenomenon; ILD: interstitial lung disease; PH: pulmonary hypertension; ECHO: echocardiogram; RHC: right heart catheterization; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension; GI: gastrointestinal; IQR: interquartile range; mo: month; SD: standard deviation.

Values are mean ± SD or (range) unless noted otherwise.

This study separated SSc patients into two groups: those who presented with RP as first symptom and those who did not.

Figure 2.

Mortality in scleroderma renal crisis and trends over time.

Pre-ACE inhibitor era

Two studies from the pre-ACE inhibitor era met study inclusion criteria. LeRoy and Fleischmann reported on 100 consecutive cases of SSc in two university referral centres between 1970 and 1975, of which 25 developed SRC. Treatments included dialysis, nephrectomy and/or renal transplant. In this study, 22 of 25 (88%) SSc-SRC patients died, including 8 before dialysis could be considered or implemented. 17 In 1983, Traub et al. 8 reported on 68 SSc-SRC patients assessed between 1955 and 1981 and reported an overall mortality rate of 83.3%. This study further compared the mortality rates in SRC before and after 1971, and found that they were 100% and 72%, respectively. 8

Post-ACE inhibitor era

In the post-ACE inhibitor era, early SRC mortality rates were reported over varying time periods and were grouped into 6-month, 1-year and 3-year groups. Steen and Medsger 28 reported a mortality rate of 19.3% and Guillevin et al. 22 reported a mortality rate of 20.9% within 6 months after SRC onset. One-year mortality rates ranged from 30% to 36%.21,32 Three-year mortality rates reported in three studies ranged from 19.4% to 40.7%.5,22,33

In the post-ACE inhibitor era, long-term SRC mortality rates were reported in two studies. Rubio-Rivas et al. 20 reported a mortality rate of 43.6% over 8.1 years of follow-up, while Sampaio-Barros et al. 4 reported a mortality rate of 48% over 9.6 years of follow-up.

Temporal trends in SRC mortality

When comparing pre- and post-ACE inhibitor era, mortality associated with SRC improved considerably (Figure 2). Traub et al. 8 reported a 1-year mortality rate of 78%. In contrast, 1-year SRC mortality rates in contemporary studies ranged from 30% to 36%, suggesting the short-term SRC mortality rates in the post-ACE inhibitor era are roughly half of those in the pre-ACE inhibitor era.21,32 Two pre-ACE inhibitor era studies reported long-term mortality rates of 88% and 83.8%.8,17 In contrast, two contemporary studies reported long-term mortality rates after SRC of 48% 4 and 43.6%, 20 consistent with a 50% reduction in mortality in the post-ACE inhibitor era.

However, despite considerable improvement in SRC-associated mortality compared to the pre-ACE inhibitor era, there is no convincing evidence of further improvement in the post-ACE inhibitor era.

There is considerable variability in mortality rates in the post-ACE inhibitor era for many reasons, including study design (retrospective, prospective), subject selection (prevalent, incident) and definition of ‘SRC mortality’, with studies reporting rates when SRC was the principle cause of death only, 5 when it was either a principle or contributing case of death, 5 when it was due to SRC and SRC treatment,22,32 and simply any mortality after SRC21,22,28,33 (Table 2). The variability in estimates makes it difficult to conclude with certainty. Nevertheless, the most recent studies report rates of 36% at 1 year, 21 29% at 3 years 5 and 44% at >8 years. 20

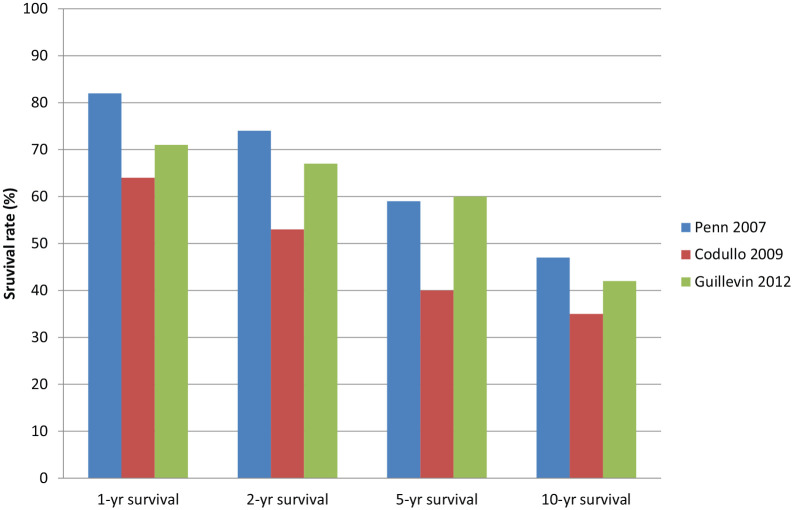

Moreover, survival rates have not changed much comparing studies from 2000 to 2012.22,28,32–34 Three contemporary studies reported 1-, 2-, 5- and 10-year survival rates. These were 64%–82%, 53%–74%, 40%–59% and 35%–47%, respectively (Table 1, Figure 3).22,33,34 Thus, we conclude that mortality remains high in SRC, without convincing evidence of further improvement in the post-ACE inhibitor era.

Figure 3.

1-, 2-, 5- and 10-year survival rates in scleroderma renal crisis.

Mortality in SRC compared to other organ involvement

Studies that reported mortality rates from SRC and other organ involvement showed generally higher rates in SRC compared to ILD or PAH. Rubio-Rivas et al. reported mortality rates of 4.7% and 36.1% for ILD and PAH, respectively, compared to 43.6% in SRC over an 8-year period of follow-up. Similarly, Sampaio-Barros et al. reported lower mortality rates in ILD (3.3%) and PAH (8.1%) compared to SRC (48%) over almost 10 years of follow-up. Although Hao et al. reported ILD and SRC mortality of 6.8% and 19.3%, respectively, during a median follow-up period of 3 years, PAH mortality was highest at 37.9%.

Two studies showed approximately fourfold higher mortality rates in SSc patients with SRC compared to SSc patients without SRC. Guillevin et al. 22 demonstrated overall mortality of 10.8% in SSc without SRC, compared to 40.7% in SSc-SRC. Similarly, LeRoy and Fleischmann 17 had reported 25.3% mortality in SSc without SRC, compared to 88% in SSc-SRC.

SRC-associated morbidity

Nine studies were included in this analysis (Table 3).8,17,21,22,28,31–34 The rates of dialysis after SRC varied widely, ranging from 25% to 68%, depending on the era, the duration of follow-up and the definitions used. The highest rate of 68% was in the pre-ACE inhibitor era. 17 In the post-ACE inhibitor era, the lowest rate of dialysis at 1 year after SRC onset was reported as 25%, but that was among patients who survived, and the rate of dialysis among those who died in the first year was not reported. 21 Most other studies reported rates of any dialysis between 45% and 64%. The proportion of SRC patients who recovered renal function and discontinued dialysis were reported in four post-ACE inhibitor era studies, and they ranged from 14.2% to 27%. Time to renal recovery was reported in two contemporary studies, 8 months (range 2–18 months) 28 and 11 months (range 1–34 months) 33 after SRC onset. The rate of permanent dialysis was reported in two studies ranging from 19% to 39.6%.22,28 Renal transplantation was performed in 3%–8% of all SRC patients. None of the studies reported the rate of SRC recurrence post-renal transplant.

Table 3.

SRC-associated morbidity.

| Study | SSc, N | SSc-SRC, N | SSc subtypes, n (%) | Follow-up, years a | Disease duration, years a | Dialysis requirement, n (%) | Death after being on dialysis, n (%) | Dialysis discontinuation rate, n (%) | Time to renal recovery, months | Renal transplant rate, n (%) | Recurrence of SRC post-renal transplant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chighizola et al. 31 | 20 | 20 | DcSSc: 17 (85.0), LcSSc: 3 (15.0), Sine SSc: 0 | 0.8 (0.5–1.1) | 9 (45) | ||||||

| Hudson et al. 21 | 75 | 75 | DcSSc: 56 (74.4), LcSSc: 16 (21.3), Sine SSc: 3 (4.0) | 1 | Mean 1.5 (IQR 0.9–3.7) | 19 (25) on dialysis at 1 year among survivors | |||||

| Cozzi et al. 32 | 20 | 20 | DcSSc: 16 (80.0), LcSSc: 4 (20.0) | 1 year minimum | 3.7 (4.8) | 11 (55) in the first 1 year | 6/11 (54.5) patients died on dialysis in the first year | ||||

| Guillevin et al. 22 | 91 | DcSSc: 78 (85.7), LcSSc: 13 (14.2) | 3.8 (5.1) | 49 (53.8) overall: 36 (39.6) permanent dialysis and 13 (14.2) temporary dialysis | 24/49 (50) patients died on dialysis (no timeline given) | 13 (14.2) | |||||

| Codullo et al. 34 | 46 | 46 | DcSSc: 40 (87.0), LcSSc: 6 (13.0) | 26 (62) overall (timeline not provided) | 7/26 (26.9) | 3/46 (6.5) with mean follow-up of 140 (54) months after SRC | |||||

| Penn et al. 33 | 110 | 110 | DcSSc: 86 (78.2), LcSSc: 24 (21.8) | Median 3.1 (range 0–14.7) | 70 (64) required dialysis at presentation of SRC | 19/70 (27) patient died on dialysis | 24/106 (22.6), although 2/24 required dialysis again after discontinuation. | Median 11 (range 1–34) | 3/110 (2.7), of which one died in the peri-operative period | ||

| Steen and Medsger 28 | 807 | 145 | DcSSc: 141 (97.2), LcSSc: 4 (2.8) | 5–10 years | 90 (62) overall: 34 (23) temporary dialysis and discontinued at mean of 8 months; 32 (19) required permanent dialysis | 34/145 (23.4) | Mean 8 (range 2–18) | 6/145 (4.1) over 4 or more years after dialysis | |||

| Traub et al. 8 | 68 | 68 | 17 (25) | 4/68 (5.9), rejection in all | |||||||

| LeRoy and Fleischmann 17 | 25 | 25 | 17 (68) and 8 died before dialysis started | 14/17(82) died either on dialysis (n = 9), post-nephrectomy (n = 4), post-renal transplant (n = 1) | 0 | 2/25 (8.0) of which one died due to acute rejection |

SRC: scleroderma renal crisis; SSc: systemic sclerosis; DcSSc: diffuse cutaneous SSc; LcSSc: limited cutaneous SSc; IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation.

Values are mean ± SD or (range) unless noted otherwise.

SSc-associated ESRD mortality

Seven studies reported data on SSc patients in dialysis or transplant registries (Table 4). Since the cause of ESRD was not specifically attributed to SRC, these studies were considered separately. Inclusion periods spanned from 1977 to 2013. As these were often nationwide registries, the numbers of SSc patients included was relatively large (n = 127–2393). All studies reflected the usual epidemiology of SSc patients with the proportion of females ranging from 67.5% to 89.2% and most patients being middle aged (40–64 years old).23–27,30,35 Four studies reported both mortality and survival rates,24–26,30 two studies reported only survival rates27,35 and one study reported only mortality rate. 23

Table 4.

Description of studies included in SSc-ESRD mortality and morbidity analysis.

| Study | Design | Country | Data source | Inclusion period | Total, N | SSc-renal disease, N | Female, n (%) | Age, years a | Quality assessment score (maximum 9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hruskova et al. 24 | Retrospective cohort | Europe | European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry | 2002–2013 | 236,082 | 342 | 233 (68.1) | At initiation of RRT: Median 59.9 (Q1–Q3 50.2–68.2) | 5 |

| Sexton et al. 23 | Retrospective cohort | United States | United States Renal Data System (USRDS) | 1996–2012 | 1,677,303 | 2398 | 1820 (75.9) | At initiation of RRT: 11.2% were <40 years, 57.5% were 40–64 years, 28.1% were 65–79 years, 3.2% were >80 years | 5 |

| Bertrand et al. 3 5 | Case series | France | 20 kidney transplant centres | 1987–2013 | 34 | 26 | 23 (67.6) | At transplantation: 52.9 (range 27.7–75.5) | b |

| Siva et al. 25 | Retrospective cohort | New Zealand | ANZDATA registry | 1963–2005 | 40,238 | 127 | 92 (72.4) | 54.7 (11.1) | 5 |

| Gibney et al. 30 | Retrospective cohort | United States | Nation-wide kidney transplant list (United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS)) | 1985–2002 | 258 | 258 | 201 (77.9) | At listing: 51 (9); at transplant: 52 (10) | 2 |

| Tsakiris et al. 26 | Retrospective cohort | Europe | ERA-EDTA Registry | 1977–1993 | 440,665 | 625 | 422 (67.5) | At initiation of RRT: more than 50% | 5 |

| Nissenson and Port 27 | Retrospective cohort | United States | 28 ESRD networks, representing 89% of all new ESRD patients in United States covered by Medicare | 1983–1985 | 4792 | 311 | 224 (72.0) | No mean age. Majority in the 40- to 59-year group (n = 52) | 5 |

SSc: systemic sclerosis; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; RRT: renal replacement therapy; Q: quartile; SD: standard deviation.

Values are mean ± SD or (range).

No quality assessment was done for case series; considered as high risk of bias.

Mortality

Five studies were included in this analysis and reported overall mortality rates of 22.9% 30 –67% 25 (Table 5). Patients in the study by Gibney et al., which reported the lowest mortality rate of 22.9%, were from a kidney transplant waiting list registry, possibly missing deaths occurring prior to registration. Three of the four studies using renal replacement registries (including both dialysis and kidney transplant) reported similar mortality rates, ranging from 52.7% to 67%.23–26 However, only one study reported the period over which this mortality occurred. Sexton et al. 23 reported mortality rates of 66.9% over 3.3 years following initiation of dialysis, 24.2% over 5 years following listing for renal transplant and 34.6% over 5.4 years after renal transplant. These rates are somewhat higher than those reported in studies of SRC above.

Table 5.

SSc-ESRD mortality and morbidity in systemic sclerosis.

| Study | Total, N | SSc-renal disease, N | Follow-up, years a | Mortality, survival or both | Death, n (%) | Renal recovery, n (%) c | Time to renal recovery | Time on dialysis until the renal transplant, years b | Renal transplant, n (%) | 3-year survival rate on dialysis | 3-year survival rate post-renal transplant | 3-year graft survival rate post-renal transplant | Other | Recurrence of SRC post-renal transplant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hruskova et al. 24 | 236,082 | 342 | Both | SSc 156/296 (52.7), diabetes mellitus 1613/3253 (49.6), other ESRD 1134/3224 (35.2). | Renal recovery within 90 days of dialysis: SSc 3 (0.9), diabetes mellitus 21 (0.6), other ESRD 38 (1.1). Renal recovery after 90 days: SSc 7.6%, diabetes mellitus 0.7%, other ESRD 2.0% | SSc: median 255 days (IQR 130–454), diabetes mellitus: median 112 (IQR 40.5–178), other ESRD: median 167.5 (IQR 60–353) | SSc 2.9 (1.6–4.7), diabetes mellitus 1.6 (0.8–2.9), other ESRD 1.6 (0.5–3.6) | SSc 46 (13.7), diabetes mellitus (18.7), non-diabetes mellitus controls (27.1) | SSc 56.5%, diabetes mellitus 62.3%, other ESRD 74.4% | SSc 90.7%, Diabetes mellitus 90.3%, other ESRD 92.9% | SSc 85.8%, diabetes mellitus 84.9%, other ESRD 86.7% | |||

| Sexton et al. 23 | 1,677,303 | 2398 | From initiation of RRT 3.3; from listing for renal transplant 5; after renal transplant 5.4 | Mortality | SSc: 1605/2042 (66.9) following initiation of RRT; 95/392 (24.2) following listing for renal transplant; 90/260 (34.6) following renal transplant. Not reported for other ESRD. | SSc more likely to recover renal function (HR 2.67, CI 1.90–3.76 compared to demography-matched ESRD without SSc) | SSc 260/2398 (10.8), non-SSc controls 203,594/1680,073 (12.1) | Graft failure 116/260 (44.6); SSc less likely to have graft failure compared to non-SSc ESRD (HR 0.90, CI 0.87–0.95, p < 0.001) | ||||||

| Bertrand et al. 3 5 | 34 | 26 | After renal transplant 9.9 | Survival post-renal transplant, graft survival (no survival on dialysis) | 3.8 (0.4–12.8) | 34 (100) | 90.3% | Death-censored graft survival 97.2% | 7 graft losses after a mean of 82.2 months (1.5–176) | 3 of 34 renal transplant | ||||

| Siva et al. 25 | 40,238 | 127 | SSc: median 1.6 (IQR 0.7–3.8); other ESRD: median 3.6 (IQR 1.6–7.8) | Both | 85 (66.9) in SSc and 22,882 (56.9) in other ESRD | SSc 13 (10.2), other ESRD 437 (1.1) | SSc 14.1 months, other ESRD 39.1 months | 22 (17.3) | Deceased donor renal allograft survival was 78% at 1 year, 53% at 5 years and 28% at 10 years. All six living donor renal allografts were still functioning at the end of the study | |||||

| Gibney et al. 30 | 258 | 258 | Both | Overall 59/257 (22.9): 29 (11.2) on the transplant list, 30 (11.7) post-renal transplant | 142 (55.1) | On transplant list 54.6% | 79.5% | 60.3% | Graft failure 63/142 (44.4) | 3 of 142 renal transplant, of 63 graft failure due to recurrence. | ||||

| Tsakiris et al. 26 | 440,665 | 625 | Both | SSc 377 (60.3), other ESRD 198,644/439,752 (45.2) | 28 (4.5) | SSc 31%, primary renal disease 66% | SSc 54%, primary renal disease 81% | SSc 44%, primary renal disease 60% | ||||||

| Nissenson and Port 27 | 4792 | 311 | Survival | 21 (6.8) | 12 (3.9) | SSc 35%, controls 40–65% |

SSc: systemic sclerosis; ESRD: end-stage renal disease; SRC: scleroderma renal crisis; IQR: interquartile range; RRT: renal replacement therapy; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; Q: quartile; SD: standard deviation.

Values are mean ± SD or (range) unless noted otherwise.

Values are the median (IQR).

Values are n(%) unless noted otherwise.

Temporal trends in mortality over time

Mortality data were difficult to compare over time due to heterogeneity between studies. Studies by Hruskova et al. and Tsakiris et al. were performed with the European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association (ERA-EDTA) Registry, but at different time periods (2002–2013 (11 years) in Hruskova et al. and 1977–1993 (16 years) in Tasakiris et al.). The proportion of overall deaths was 52.7% in Hruskova et al. 24 compared to 60.3% in Tsakiris et al. 26

Survival on dialysis and post-renal transplant

Three-year patient survival rates on dialysis ranged from 31% to 56.5% (n = 4 studies),24,26,27,30 and 3-year patient survival rates post-renal transplant ranged from 54% to 90.7% (n = 4 studies)24,26,30,35 (Supplemental Figure 1). Of note, SSc-ESRD survival rates on dialysis were consistently lower when compared to non-SSc ESRD survival rates.24–27

SSc-associated ESRD morbidity

Renal recovery

Rates of renal recovery were reported in three studies and ranged from 6.8% to 10%.24,25,27 Renal recovery and discontinuation of dialysis were more likely in SSc-ESRD than in non-SSc-ESRD. Hruskova et al. demonstrated a renal recovery rate of 7.6% in SSc, 0.7% in diabetes mellitus and 2.0% in other ESRD. Siva et al. showed similar results, with 10% renal recovery in SSc-ESRD, while it was 1% in other ESRD. Sexton et al. estimated that SSc-ESRD was almost three times more likely to recover renal function (hazard ratio 2.67, 95% confidence interval 1.90–3.76) compared to matched ESRD patients without SSc. Time to renal recovery was reported in two studies and ranged from 8 to 14 months.24,25

Renal transplant

The proportion of patients on dialysis who underwent renal transplant were reported in six studies.23–27,30 Using registries of patients on kidney transplant waiting lists, Gibney et al. 30 found that 55% of SSc-ESRD patients proceeded to renal transplant. Other studies using registries of dialysis patients reported renal transplant rates ranging between 3.9% and 17.3%,23–27 compared to 3%–8% of all SSc-SRC patients reported above.

Earlier studies that included patients from the 1970 to the 1980s showed lower rates of renal transplant (3.9%–4.5%),26,27 while the rate of renal transplant increased to 10.8%–13.7% in the two most recent studies.23,24 Nonetheless, compared to other ESRD patients, SSc-ESRD patients were less likely to receive renal transplant.23,24

Three-year graft survival post-renal transplant ranged from 44% to 85.8% (Supplemental Figure 1).24,26,30 Although early studies presented lower graft survival in SSc-ESRD compared to other ESRD, 26 two more recent studies showed comparable graft survival post-renal transplant.23,24

Two studies each reported three cases of SRC recurrence post-renal transplant, 8.8% 35 and 2.1% 30 of the total renal transplants. Bertrand et al. confirmed the recurrence of SRC by a renal graft biopsy. Methods of SRC recurrence diagnosis are unclear in the study by Gibney et al. Two cases from Bertrand et al. had recurrence at 1 and 4 months after the renal transplant, but the third case had recurrence at 57 months post-renal transplant. Gibney et al. also stated that two patients had ‘early recurrence’ in the form of thrombotic microangiopathy, although no specific duration was mentioned.

Non-SRC renal disease in SSc

Only one study by Steen et al. 29 reported outcomes specifically related to SSc renal disease other than SRC. This retrospective cohort study conducted in the United States between 1972 and 1993 included 675 patients all with diffuse cutaneous SSc with a mean follow-up of 8.5 years (quality assessment score 6/9). They reported that 173 (26%) patients had renal abnormalities (defined as blood urea nitrogen (BUN) > 25 mg/dL, serum creatinine > 1.2 mg/dL and 3 or 4+ proteinuria on two occasions on dipstick or proteinuria > 250 mg/24 h). Likely etiologies were identified for 105 patients, including pre-renal causes (congestive heart failure, pulmonary fibrosis, non-scleroderma heart disease, gastrointestinal disease, medications (D-penicillamine, diuretics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and sepsis). None of these patients developed chronic or progressive renal insufficiency.

Discussion

This systematic review included 20 studies and 14,059 SSc patients, of whom 854 had SRC, 4095 SSc-ESRD and 173 non-SRC renal disease. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systemically collect and analyse all published literature on the mortality and morbidity associated with SRC, SSc-ESRD and non-SRC renal disease in SSc. We found that the mortality associated with SSc-SRC remains high in the post-ACE inhibitor era (20% at 6 months, 30%–36% at 1 year and 20%–40% at 3 years from SRC onset). Even though this represents a 50% improvement compared to rates in the pre-ACE inhibitor era, there has not been any convincing evidence of improvement in mortality since. Furthermore, although ILD and PAH are more frequent causes of death in contemporary studies because they are more common than SRC, the mortality rate in SRC is proportionally as high if not higher than these. In terms of morbidity, the rate of permanent dialysis after SRC in the post-ACE inhibitor era ranged from 19% to 40%, and 3%–17% of SSc patients underwent renal transplant. Survival was better in patients post-renal transplant (54%–91%) compared to those on dialysis (31%–56%). In addition, graft survival post-renal transplant in SSc improved over time and appeared similar to that of patients with other types of ESRD. Thus, in the absence of renal recovery after 1–2 years, renal transplant remains an important option.

The literature on SSc renal disease focussed largely on SRC and ESRD. Only one study reported specifically on non-SRC renal diseases in SSc. The predominant etiology was non-scleroderma-related causes, and outcomes were favourable without any development of chronic or progressive renal insufficiency. However, this is based on one single-centre study, and further studies are required to aid our understanding in non-SRC renal disease in SSc.

SRC is known to be life-threatening and our study confirms this. 36 In addition, our findings may represent underestimates of the true rates. Indeed, most studies were retrospective studies of prevalent SRC cases, possibly introducing a survival bias. In fact, Hao et al. compared mortality in incident and prevalent patients in the same study sample and demonstrated that SRC mortality was higher in the incident (19.4%) than in the prevalent (13.3%) cases. The only prospective study of mortality in an inception cohort of SRC reported a 1-year mortality rate of 36%. 21 There are no long-term estimates from prospective studies.

Our findings are in agreement with previous studies showing that SRC mortality has declined with ACE inhibitor use. Steen et al. 37 compared the Pittsburgh SSc cohort with and without ACE inhibitor and found that 6-month mortality fell from 75% to 27%. Of note, this study was not included in our systematic review, as another study reporting on a larger number of patients from the Pittsburgh cohort (and for a longer period of follow-up) was included instead. 28

Steen and Medsger 7 further demonstrated that the proportion of scleroderma-related deaths due to SRC significantly decreased over a 30-year period (1972–2002) from 42% to 6%, while the proportion of deaths due to pulmonary fibrosis and PAH increased steadily. A note should be made that those rates are not mortality rates, but rather proportions of death due to specific organ involvement. In fact, our systematic review suggested that SRC still imposes a high mortality rate, proportionally higher than ILD and in some cases PAH, and that SRC mortality has not improved since the late 1970s.

The trends in improved survival on dialysis and post-renal transplant, and in graft survival, need to be interpreted with caution. Indeed, compared to non-SSc ESRD patients, SSc-ESRD patients still have poor outcomes. Therefore, the improvement in survival rates in SSc-ESRD may be secondary to overall improvement in ESRD survival, rather than specifically improved survival in SSc-ESRD.

Although the rate of renal transplant in SSc has increased over time, it only accounts for a small proportion of SSc-SRC patients (3%–8% of SSc-SRC and 4%–17% of SSc-ESRD patients). Also, compared to other ESRD patients, SSc-ESRD patients were less likely to receive renal transplant. One could speculate that this is partly due to a higher renal recovery rate and that less SSc-ESRD patients require renal transplant. On the other hand, this may be because of a greater burden of disease from SSc or a greater proportion of SSc-ESRD patients who die before renal transplant could be performed. Patient survival rates post-renal transplant were consistently better than patient survival rates on dialysis. Although this may be due to selection bias (i.e. selection of those patients who survived long enough on the transplant list and those who were healthy enough to be a renal transplant candidate), renal transplant remains an important option for the treatment of SSc-ESRD.

Recurrence of SRC in allograft appears rare, and some studies suggest that SRC recurrence occurs early after the renal transplant. In our literature review, two studies reported three cases of SRC recurrence post-renal transplant each (8.8% and 2.1% of total renal transplants).30,35 The recurrence of SRC post-renal transplant is reported rarely in literature. This may be an underestimation, as causes of allograft failure are often difficult to ascertain. One literature review on SRC recurrence post-renal transplant identified five cases of recurrent SRC in the allograft, all within a year of onset of native kidney SRC. 38 This appears to be in line with SRC recurrences reported in two included studies.30,35

We recognize the limitations of our study, although we attempted to address these. First, there was significant heterogeneity in study design, follow-up period in which mortality data were collected and reported outcome measures. We analysed data in subsets, categorized based on the period over which death was reported and the reported outcome measures, in an attempt to allow meaningful comparisons. Second, our study was limited by heterogeneous definitions of SSc, SRC and renal disease, as well as potential misdiagnosis. Definitions varied from physician opinion, registry code and use of clinical and laboratory findings. Development of classification criteria for SRC is ongoing and would promote consistency of patient populations in future research in SRC. 39 Finally, none of the included studies were of high methodological quality. In many cases, this was due to the lack of a non-SRC or non-SSc renal disease cohort as a control group. This was inevitable as SRC is a rare condition and only a few studies had the primary aim of studying SRC mortality and morbidity. In addition, only one study was a prospective cohort study and the rest were either retrospective cohort studies or case series. It is possible that SRC mortality was underestimated in the retrospective studies due to survival bias. Alternatively, in the case series, there may also have been bias to over-report severe (or alternatively better) outcomes. We only selected case series with more than 20 SRC cases to reduce selection bias.

In conclusion, the burden of disease associated with SRC remains very high. There has been little improvement in the post-ACE inhibitor era. This study highlights the importance of pursuing research to identify novel treatments to improve outcomes of SRC.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material for Mortality and morbidity in scleroderma renal crisis: A systematic literature review by Hyein Kim, Frédéric Lefebvre, Sabrina Hoa and Marie Hudson in Journal of Scleroderma and Related Disorders

Acknowledgments

The Editor/Editorial Board Member of JSRD is an author of this paper, therefore, the peer review process was managed by alternative members of the Board and the submitting Editor/Board member had no involvement in the decision-making process.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Hyein Kim  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7546-3817

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7546-3817

Frédéric Lefebvre  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9550-046X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9550-046X

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Denton CP. Advances in pathogenesis and treatment of systemic sclerosis. Clin Med 2016; 16(1): 55–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J, et al. Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology 2012; 51(6): 1017–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bennett R, Bluestone R, Holt PJ, et al. Survival in scleroderma. Ann Rheum Dis 1971; 30(6): 581–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sampaio-Barros PD, Bortoluzzo AB, Marangoni RG, et al. Survival, causes of death, and prognostic factors in systemic sclerosis: analysis of 947 Brazilian patients. J Rheumatol 2012; 39(10): 1971–1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hao Y, Hudson M, Baron M, et al. Early mortality in a multinational systemic sclerosis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol 2017; 69(5): 1067–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tyndall AJ, Bannert B, Vonk M, et al. Causes and risk factors for death in systemic sclerosis: a study from the EULAR Scleroderma Trials and Research (EUSTAR) database. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69(10): 1809–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr. Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis 2007; 66(7): 940–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Traub YM, Shapiro AP, Rodnan GP, et al. Hypertension and renal failure (scleroderma renal crisis) in progressive systemic sclerosis. Review of a 25-year experience with 68 cases. Medicine 1983; 62(6): 335–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Badesch DB, Tapson VF, McGoon MD, et al. Continuous intravenous epoprostenol for pulmonary hypertension due to the scleroderma spectrum of disease. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132(6): 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002; 346(12): 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Badesch DB, Hill NS, Burgess G, et al. Sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol 2007; 34(12): 2417–2422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements PJ, et al. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(25): 2655–2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016; 4(9): 708–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Volkmann ER, Tashkin DP. Treatment of systemic sclerosis-related interstitial lung disease: a review of existing and emerging therapies. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016; 13(11): 2045–2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hassoun PM. Therapies for scleroderma-related pulmonary arterial hypertension. Expert Rev Respir Med 2009; 3(2): 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nikpour M, Baron M. Mortality in systemic sclerosis: lessons learned from population-based and observational cohort studies. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014; 26(2): 131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. LeRoy EC, Fleischmann RM. The management of renal scleroderma: experience with dialysis, nephrectomy and transplantation. Am J Med 1978; 64(6): 974–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kowal-Bielecka O, Fransen J, Avouac J, et al. Update of EULAR recommendations for the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76(8): 1327–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rubio-Rivas M, Corbella X, Pestana-Fernandez M, et al. First clinical symptom as a prognostic factor in systemic sclerosis: results of a retrospective nationwide cohort study. Clin Rheum 2018; 37(4): 999–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hudson M, Baron M, Tatibouet S, et al. Exposure to ACE inhibitors prior to the onset of scleroderma renal crisis-results from the International Scleroderma Renal Crisis Survey. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2014; 43(5): 666–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guillevin L, Berezne A, Seror R, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis: a retrospective multicentre study on 91 patients and 427 controls. Rheumatology 2012; 51(3): 460–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sexton DJ, Reule S, Foley RN. End-stage kidney disease from scleroderma in the United States, 1996 to 2012. Kidney Int Rep 2018; 3(1): 148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hruskova Z, Pippias M, Stel VS, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with systemic sclerosis (scleroderma) requiring renal replacement therapy in Europe: results from the ERA-EDTA registry. Am J Kidney Dis 2019; 73: 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Siva B, McDonald SP, Hawley CM, et al. End-stage kidney disease due to scleroderma – outcomes in 127 consecutive ANZDATA registry cases. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011; 26(10): 3165–3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsakiris D, Simpson HK, Jones EH, et al. Report on management of renal failure in Europe, XXVI, 1995. Rare diseases in renal replacement therapy in the ERA-EDTA Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11(Suppl. 7): 4–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nissenson AR, Port FK. Outcome of end-stage renal disease in patients with rare causes of renal failure. III. Systemic/vascular disorders. Q J Med 1990; 74(273): 63–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steen VD, Medsger TA., Jr. Long-term outcomes of scleroderma renal crisis. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133(8): 600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Steen VD, Syzd A, Johnson JP, et al. Kidney disease other than renal crisis in patients with diffuse scleroderma. J Rheumatol 2005; 32(4): 649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gibney EM, Parikh CR, Jani A, et al. Kidney transplantation for systemic sclerosis improves survival and may modulate disease activity. Am J Transplant 2004; 4(12): 2027–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chighizola CB, Pregnolato F, Meroni PL, et al. N-terminal pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide as predictor of outcome in scleroderma renal crisis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016; 34(5Suppl. 100): 122–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cozzi F, Marson P, Cardarelli S, et al. Prognosis of scleroderma renal crisis: a long-term observational study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27(12): 4398–4403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Penn H, Howie AJ, Kingdon EJ, et al. Scleroderma renal crisis: patient characteristics and long-term outcomes. QJM 2007; 100(8): 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Codullo V, Cavazzana I, Bonino C, et al. Serologic profile and mortality rates of scleroderma renal crisis in Italy. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(7): 1464–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bertrand D, Dehay J, Ott J, et al. Kidney transplantation in patients with systemic sclerosis: a nationwide multicentre study. Transpl Int 2017; 30(3): 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Denton CP, Lapadula G, Mouthon L, et al. Renal complications and scleroderma renal crisis. Rheumatology 2009; 48(Suppl. 3): iii32–iii35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Steen VD, Costantino JP, Shapiro AP, et al. Outcome of renal crisis in systemic sclerosis: relation to availability of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Ann Intern Med 1990; 113(5): 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pham PT, Pham PC, Danovitch GM, et al. Predictors and risk factors for recurrent scleroderma renal crisis in the kidney allograft: case report and review of the literature. Am J Transplant 2005; 5(10): 2565–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Butler EA, Baron M, Fogo AB, et al. Generation of a core set of items to develop classification criteria for scleroderma renal crisis using consensus methodology. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019; 71: 964–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Supplementary_material for Mortality and morbidity in scleroderma renal crisis: A systematic literature review by Hyein Kim, Frédéric Lefebvre, Sabrina Hoa and Marie Hudson in Journal of Scleroderma and Related Disorders