Abstract

Systemic sclerosis is a rare systemic autoimmune disease characterized by microvascular impairment and fibrosis of the skin and other organs with poor outcomes. Toxic causes may be involved. We reported the case of a 59-year-old woman who developed an acute systemic sclerosis after two doses of adjuvant chemotherapy by docetaxel and cyclophosphamide for a localized hormone receptor + human epithelial receptor 2—breast cancer. Docetaxel is a major chemotherapy drug used in the treatment of breast, lung, and prostate cancers, among others. Scleroderma-like skin-induced changes (morphea) have been already described for taxanes. Here, we report for the first time a case of severe lung and kidney flare with thrombotic microangiopathy after steroids for acute interstitial lung disease probably induced by anti-RNA polymerase III + systemic sclerosis after docetaxel.

Keywords: Docetaxel, chemotherapy, scleroderma, drug-induced autoimmune disease, systemic sclerosis, paraneoplastic

Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare systemic autoimmune disease characterized by microvascular impairment and fibrosis of the skin and other organs with poor outcomes. Toxic causes may be involved.

Case report

We reported the case of a 59-year-old woman who developed an acute SSc after two doses of adjuvant chemotherapy by docetaxel (75 mg/m2) and cyclophosphamide (600 mg/m2) (DC) for a localized hormone receptor (HR) + human epithelial receptor 2 (HER2)—breast cancer.

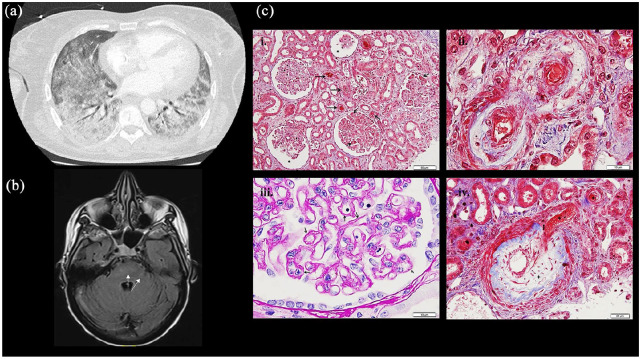

After 2.5 months of partial mastectomy and after 2 cycles of DC, the patient was hospitalized for severe hypoxemia (PaO2 = 48 mmHg) with interstitial syndrome on the computed tomography (CT) scan and right heart failure (Figure 1). The bronchial fibroscopy with broncho-alveolar lavage found an inflammatory alveolitis made of numerous neutrophils (300,000 cells/mL with 83% of neutrophils). Echocardiography showed an elevated mean pulmonary arterial pressure (mPAP) of 44 mmHg and left ejection function (LEF) of 64%. Infectious causes were eliminated, and steroids therapy (1 mg/kg/day) was started. Under steroids, she developed an acute renal failure with creatinine value of 273 µmol/L (glomerular filtration rate (DFG) = 16 mL/min/1.73 m2) and hemolytic anemia with 2.5% circulating schistocytes, ADAMTS13 activity at 33% (normal = 50%–150%), low haptoglobin rate at 0.4 g/L, and thrombopenia at 50G/L, and a diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) was made. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) because of increased need of oxygen with 70% of FiO2 (PaP02/FiO2 = 115) and intermitted hemodialysis for KDIGO III (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) renal organic failure due to TMA. A renal biopsy was performed and showed lesions of acute TMA and medium-caliber interlobular arterioles with a myxedema appearance referring to SSc (Figure 1). In hypothesis of scleroderma renal crisis provoked by glucocorticoids, this therapy was reduced and completed with plasma exchanges. While patient was out of ICU, she developed confusion with transient loss of consciousness. The analysis of cerebrospinal fluid did not find any infectious or paraneoplastic etiology, but brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed intense multiple signals in the white matter of two pyramidal tracks (Figure 1). A PRES (posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome) associated with hypertension associated with SSc renal crisis was diagnosed. The patient developed sphincter disorders in link with suspected central involvement and pyramidal syndrome for several weeks.

Figure 1.

Capture of different clinical manifestations: (a) Chest CT scan: Bilateral interstitial diffuse syndrome on the CT (lung window), (b) brain MRI (Flair axial) with evidence of hypersignal in the right cerebellar hemisphere axial plan of Flair sequence, (c) renal biopsy ((i)–(iv)): (i) Glomeruli show ischemic features with thickening of the glomerular capillary basement membranes and/or dilated urinary space (*). Many thrombosis or red blood cells are seen in arterioles and capillary lumen of glomeruli (→). (Masson’s trichrome, ×200). (ii). Mucoid intimal thickening with considerable reduction of the interlobular arterial lumen (+) with red blood cells are seen in vascular luminary of small afferent arteries (*). (Masson’s trichrome, ×400). (iii). Pale mucoid intimal hyperplasia of a small interlobular artery, with swelling of medial myocytes (*). (Masson’s trichrome, ×1000). (iv). Thickening and wrinkling of the glomerular capillary wall with double-contour appearance (→). (Periodic-acid Schiff, ×1000).

The diagnosis of SSc was made retrospectively and complete with the presence of severe Raynaud’s syndrome and a megaesophagus. Rodnan score at this time was 11/51. The diagnosis of toxic docetaxel–related SSc was retained after serological results: the antinuclear antibodies (ANA) were positive at 1/1280 with the aspect of type 1 anti-pseudo-PCNA antibodies (associated with cancer). 1 Interestingly, the anti-RNA polymerase III (anti-RNA pol III) antibodies became positive at 28 U/mL (N < 20 U/mL) in the second time and stay positive thereafter. It should be noted that the analysis of serum collected before chemotherapy did not find anti-RNA pol III antibodies, but only ANA with same speckled fine pattern of type 1 anti-pseudo-PCNA.

The patient depended on hemodialysis three times a week. Concerning her breast cancer, the 18F-FDG-PET-CT did not show any recurrence. The adjuvant radiation was excluded because of scleroderma skin involvement. As adjuvant chemotherapy was contraindicated, the complete mastectomy was realized.

Discussion

Docetaxel is a major chemotherapy drug used in the treatment of breast, lung, and prostate cancers, among others. Scleroderma-like skin-induced changes have been already described for Taxanes. 2 Sporadic cases of TMA and more frequently of docetaxel interstitial pneumopathy are reported.3,4 However, the systemic involvement is not well established. A case report presented a case of systemic scleroderma with heart congestive failure 2 years after the diagnosis of breast cancer and treatment by DC. 5 The interesting finding in our case is the complexity of the clinical picture with multi-organ involvement, especially neurological symptoms.

Besides taxanes, many drugs have been associated with the occurrence of scleroderma and scleroderma-like disorders. 6 Although chemotherapeutic agents are most often involved, cases have also been reported with others drugs (Table 1). Most cases of drug-induced scleroderma remained localized scleroderma with skin changes. Drug-induced SSc is rather rare. In localized scleroderma, skin involvement may display atypical features such as predominant edema, preferential axial or proximal involvement and bullous or vesicular lesions. Skin sclerosis may also be limited to a small area (localized scleroderma or morphea). 7 In systemic forms, specific autoantibodies (mainly, anticentromere, anti-RNA pol III, and antitopoisomerase 1 antibodies) are usually lacking. Finally, most cases improve after drug withdrawal. Three main mechanisms have been proposed to explain the occurrence of drug-induced scleroderma, echoing the three poles of SSc pathophysiology: (1) fibroblasts activation with increased production of collagen, (2) immune system stimulation, and (3) tissue ischemia induced by vasoconstriction or vascular thrombosis. 6

Table 1.

Drugs associated with the occurrence of scleroderma and scleroderma-like syndromes.

| Drugs | Clinical features | References |

|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapeutics | ||

| Bleomycin | Scleroderma-like skin changes, pulmonary fibrosis | Haustein and Haupt, 6 Inaoki et al. 9 |

| Docetaxel, paclitaxel | Scleroderma-like skin changes, possible visceral involvement | Itoh et al., 10 Winkelmann et al. 11 |

| Uracil-tegafur | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Kono et al. 12 |

| Gemcitabine | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Bessis et al. 13 |

| Capecitabine | Scleroderma-like skin changes, possible visceral involvement | Saif et al. 14 |

| Pemetrexed | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Ishikawa et al. 15 |

| Doxorubicine and cyclophosphamide association | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Alexandrescu et al. 16 |

| Hydroxyurea | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Garcia-Martinez et al. 17 |

| Analgesics | ||

| Pentazocine | Localized scleroderma at the injection sites | Palestine et al. 18 |

| Methysergide | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Kluger et al. 19 |

| Ketobemidone | Localized scleroderma at the injection sites | Danielsen et al. 20 |

| Psychotropics | ||

| Carbidopa and L-5-hydroxy-tryptophan | Scleroderma-like skin changes, localized scleroderma | Joly et al. 21 |

| Ethosuximide | Scleroderma-like skin changes associated with systemic lupus erythematosus | Teoh and Chan, 22 |

| Appetite suppressants | ||

| Diethylpropion hydrochloride, mazindol, phenmetrazine, dexamphetamine-metaqualone, fenproporex, fenfluramine | SSc (typical skin lesions, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ±visceral involvement, ±autoantibodies), localized scleroderma | Aeschlimann et al., 23 Tomlinson and Jayson, 24 Korkmaz et al. 25 |

| Food supplements | ||

| L-tryptophan | Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, eosinophilic fasciitis, scleroderma-like skin changes | Belongia et al., 26 Varga et al. 27 |

| Antihypertensive drugs | ||

| Bisoprolol | Localized scleroderma | De Dobbeleer et al. 28 |

| Fosinopril | SSc, eosinophilic fasciitis | Biasi et al. 29 |

| Immune system modulators | ||

| Human recombinant interleukin-2 | Scleroderma-like skin changes | Marie et al. 30 |

| Interferon alpha | SSc | Beretta et al. 31 |

| Anti-PD1 (pembrolizumab, nivolumab) | Scleroderma-like skin changes ± interstitial lung disease, worsening of pre-existing SSc | Tjarks et al., 32 Barbosa et al., 33 Terrier et al. 34 |

| Other | ||

| Vitamin K1 | Localized scleroderma | Pujol et al. 35 |

| Penicillamine | Scleroderma-like skin changes and restrictive lung defect | Miyagawa et al. 36 |

| Triamcinolone | Localized scleroderma | Rodriguez Prieto et al. 37 |

| Bromocriptine | Localized scleroderma | Leshin et al. 7 |

SSc: systemic sclerosis.

The hypothesis of paraneoplastic SSc was consider in our case. Several types of solid tumors have been described as potentially associated with SSc, especially with anti-RNA pol III. 8 However anti-RNA pol III positivity appeared secondary. One possibility is that anti-RNA pol III antibodies were missed by the first test but that the autoimmune process had already started before the treatment of the cancer as a paraneoplastic form of SSc. In this view, the development of megao-esophagus usually needs time in SSc. Nonetheless, more than 1 year after the mastectomy and the arrest of all therapies, our patient had complete remission of her breast cancer, and SSc does not evolve anymore.

Physician should be aware about respiratory signs and renal function changes to not ignore a severe complication induced by docetaxel.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by ERN (ReCONNET) and EU INTERREG V (PERSONALIS).

ORCID iD: Aurélien Guffroy  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0615-5305

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0615-5305

References

- 1. Guffroy A, Dima A, Nespola B, et al. Anti-pseudo-PCNA type 1 (anti-SG2NA) pattern: track down Cancer, not SLE. Joint Bone Spine 2016; 83(3): 330–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yang JQ, Dou TT, Chen XB, et al. Docetaxel-induced scleroderma: a case report and its role in the production of extracellular matrix. Int J Rheum Dis 2017; 20(11): 1835–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shrestha A, Khosla P, Wei Y. Docetaxel-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura/hemolytic uremic syndrome-related complex in a patient with metastatic prostate cancer. Am J Ther 2011; 18(5): e167–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Read WL, Mortimer JE, Picus J. Severe interstitial pneumonitis associated with docetaxel administration. Cancer 2002; 94(3): 847–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Park B, Vemulapalli RC, Gupta A, et al. Docetaxel-induced systemic sclerosis with internal organ involvement masquerading as congestive heart failure. Case Reports Immunol 2017; 2017: 4249157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haustein UF, Haupt B. Drug-induced scleroderma and sclerodermiform conditions. Clin Dermatol 1998; 16(3): 353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leshin B, Piette WW, Caplan RM. Morphea after bromocriptine therapy. Int J Dermatol 1989; 28(3): 177–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Monfort JB, Mathian A, Amoura Z, et al. [Cancers associated with systemic sclerosis involving anti-RNA polymerase III antibodies]. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2018; 145(1): 33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Inaoki M, Kawabata C, Nishijima C, et al. Case of bleomycin-induced scleroderma. J Dermatol 2012; 39(5): 482–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Itoh M, Yanaba K, Kobayashi T, et al. Taxane-induced scleroderma. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156(2): 363–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Winkelmann RR, Yiannias JA, DiCaudo DJ, et al. Paclitaxel-induced diffuse cutaneous sclerosis: a case with associated esophageal dysmotility, Raynaud’s phenomenon, and myositis. Int J Dermatol 2016; 55(1): 97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kono T, Ishii M, Negoro N, et al. Scleroderma-like reaction induced by uracil-tegafur (UFT), a second-generation anticancer agent. J Am Acad Dermatol 2000; 42(3): 519–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bessis D, Guillot B, Legouffe E, et al. Gemcitabine-associated scleroderma-like changes of the lower extremities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004; 51(2 Suppl): S73– S76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Saif MW, Agarwal A, Hellinger J, et al. Scleroderma in a patient on capecitabine: is this a variant of hand-foot syndrome? Cureus 2016; 8(6): e663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ishikawa K, Sakai T, Saito-Shono T, et al. Pemetrexed-induced scleroderma-like conditions in the lower legs of a patient with non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Dermatol 2016; 43(9): 1071–1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alexandrescu DT, Bhagwati NS, Wiernik PH. Chemotherapy-induced scleroderma: a pleiomorphic syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol 2005; 30(2): 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. García-Martínez FJ, García-Gavín J, Alvarez-Pérez A, et al. Scleroderma like syndrome due to hydroxyurea. Clin Exp Dermatol 2012; 37(7): 755–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Palestine RF, Millns JL, Spigel GT, et al. Skin manifestations of pentazocine abuse. J Am Acad Dermatol 1980; 2(1): 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kluger N, Girard C, Bessis D, et al. Methysergide-induced scleroderma-like changes of the legs. Br J Dermatol 2005; 153(1): 224–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Danielsen AG, Hultberg IB, Weismann K. Hudskader efter injektionsmisbrug. Kroniske forandringer forårsaget af ketobemidon (Ketogan) [Skin lesions after injection abuse. Chronic changes caused by ketobemidone (Ketogan)]. Ugeskr Laeger 1994; 156(2): 162–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joly P, Lampert A, Thomine E, et al. Development of pseudobullous morphea and scleroderma-like illness during therapy with L-5-hydroxytryptophan and carbidopa. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 25(2 Pt 1): 332–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Teoh PC, Chan HL. Lupus-scleroderma syndrome induced by ethosuximide. Arch Dis Child 1975; 50(8): 658–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aeschlimann A, de Truchis P, Kahn MF. Scleroderma after therapy with appetite suppressants. Report on four cases. Scand J Rheumatol 1990; 19(1): 87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomlinson IW, Jayson MI. Systemic sclerosis after therapy with appetite suppressants. J Rheumatol 1984; 11(2): 254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Korkmaz C, Fresko I, Yazici H. A case of systemic sclerosis that developed under dexfenfluramine use. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999; 38(4): 379–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Belongia EA, Mayeno AN, Osterholm MT. The eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome and tryptophan. Annu Rev Nutr 1992; 12: 235–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Varga J, Peltonen J, Uitto J, et al. Development of diffuse fasciitis with eosinophilia during L-tryptophan treatment: demonstration of elevated type I collagen gene expression in affected tissues. A clinicopathologic study of four patients. Ann Intern Med 1990; 112(5): 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. De Dobbeleer G, Engelholm JL, Heenen M. Morphea after beta-blocker therapy. Eur J Dermatol 1993; 3(2): 108–109. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Biasi D, Caramaschi P, Carletto A, et al. Scleroderma and eosinophilic fasciitis in patients taking fosinopril. J Rheumatol 1997; 24(6): 1242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Marie I, Joly P, Courville P, et al. Pseudosystemic sclerosis as a complication of recombinant human interleukin 2 (aldesleukin) therapy. Br J Dermatol 2007; 156(1): 182–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Beretta L, Caronni M, Vanoli M, et al. Systemic sclerosis after interferon-alfa therapy for myeloproliferative disorders. Br J Dermatol 2002; 147(2): 385–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tjarks BJ, Kerkvliet AM, Jassim AD, et al. Scleroderma-like skin changes induced by checkpoint inhibitor therapy. J Cutan Pathol 2018; 45(8): 615–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc 2017; 92(7): 1158–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Terrier B, Humbert S, Preta LH, et al. Risk of scleroderma according to the type of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Autoimmun Rev 2020; 19(8): 102596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pujol RM, Puig L, Moreno A, et al. Pseudoscleroderma secondary to phytonadione (vitamin K1) injections. Cutis 1989; 43(4): 365–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miyagawa S, Yoshioka A, Hatoko M, et al. Systemic sclerosis-like lesions during long-term penicillamine therapy for Wilson’s disease. Br J Dermatol 1987; 116(1): 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rodríguez Prieto MA, Quiñones PA, Aragoneses H, et al. Atrofia linear esclerodermiforme por triamcinolona [Sclerodermiform linear atrophy caused by triamcinolone]. Med Cutan Ibero Lat Am 1985; 13(4): 353–356. Spanish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]