Abstract

Background

Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) are of great horticultural importance throughout the world for their foliage and decorative berries, yet a dearth of genetic information has hampered our understanding of phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history. Here, we compare chloroplast genomes from across Ilex and estimate phylogenetic relationships.

Results

We sequenced the chloroplast genomes of seven Ilex species and compared them with 34 previously published Ilex plastomes. The length of the seven newly sequenced Ilex chloroplast genomes ranged from 157,182 bp to 158,009 bp, and contained a total of 118 genes, including 83 protein-coding, 31 rRNA, and four tRNA genes. GC content ranged from 37.6 to 37.69%. Comparative analysis showed shared genomic structures and gene rearrangements. Expansion and contraction of the inverted repeat regions at the LSC/IRa and IRa/SSC junctions were observed in 22 and 26 taxa, respectively; in contrast, the IRb boundary was largely invariant. A total of 2146 simple sequence repeats and 2843 large repeats were detected in the 41 Ilex plastomes. Additionally, six genes (psaC, rbcL, trnQ, trnR, trnT, and ycf1) and two intergenic spacer regions (ndhC-trnV and petN-psbM) were identified as hypervariable, and thus potentially useful for future phylogenetic studies and DNA barcoding. We recovered consistent phylogenetic relationships regardless of inference methodology or choice of loci. We recovered five distinct, major clades, which were inconsistent with traditional taxonomic systems.

Conclusion

Our findings challenge traditional circumscriptions of the genus Ilex and provide new insights into the evolutionary history of this important clade. Furthermore, we detail hypervariable and repetitive regions that will be useful for future phylogenetic and population genetic studies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12864-022-08397-9.

Keywords: Aquifoliaceae, Chloroplast genome, Hypervariable regions, Phylogenomics, Relationship

Introduction

Ilex L., comprised of ca. 600 evergreen or deciduous tree and shrub species, is the only genus in the family Aquifoliaceae [1]. Members of the genus are mostly distributed in the tropics, with centers of species diversity located in tropical America and southeast Asia, but also extending into temperate regions [2, 3]. Most species of Ilex, including I. cornuta Lindl. et Paxt., I. purpurea Hassk., I. paraguariensis A. St.-Hil., and I. rotunda Thunb., have economic and horticultural value [4–8] and relatively broad ranges, although many species are narrowly endemic. To date, as many as 250 species of Ilex have been classified as endangered and placed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) red list [9].

In the past two decades, advances in sequencing technology and analytical methods have contributed to greater phylogenetic resolution within Ilex. Several loci from both the nuclear and plastid genomes, including rbcL, trnL-trnF, atpB-rbcL, nuclear ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers (nrITS), and chloroplast glutamine synthetase (nepGS), have been used to estimate phylogenetic relationships within the genus [10–17]. However, a broad and representative sample of Ilex species has not yet been achieved in any phylogenetic study; thus the phylogeny of Ilex remains largely unresolved [13, 16]. Furthermore, recent phylogenetic studies have revealed substantial incongruence between the nuclear and plastid topologies [10, 13–15]. Recent molecular phylogenies did not support traditional classifications of Ilex based on morphological features [18, 19]; however, these studies used only a few plastid or nuclear gene fragments and had generally poor resolution due to high conservation of plastid genes. At present, the phylogenetic relationships among lineages in genus Ilex remain uncertain, thus, further investigations are needed to reconstruct the evolutionary history of this clade.

Complete chloroplast genomes have been relatively more successful than short sequence fragments in resolving the relationships of many land plant clades at different taxonomic levels [20–22]. In general, land plant chloroplast genomes are relatively stable and contain four extremely evolutionarily conserved regions: a pair of inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb), a large single-copy region (LSC), and a small single-copy region (SSC) [23]. At the same time, chloroplast genomes contain a large amount of phylogenetic information with a mutation rate sufficient for phylogenetic inference and species delimitation [24].

To date, the complete chloroplast genome sequences of a total of 34 Ilex species have been made available in the NCBI GenBank database (accessed on 1 August 2021), which accounts for only ca. 5.7% of the total species diversity. Here, we expand Ilex genetic resources by newly sequencing the chloroplast genomes of seven species: I. dasyphylla, I. fukienensis, I. lohfauensis, I. venusta, I. viridis, I. yunnanensis, and I. zhejiangensis. Three of which, Ilex fukienensis, I. venusta, and I. zhejiangensis, are known to have a very narrow distribution in China [15, 25], while the other four species are widely distributed in China and adjacent regions. We aimed to (i) investigate the structural and compositional variations of Ilex chloroplast genomes, (ii) identify highly variable regions useful for resolving interspecific relationships and species delimitation, and (iii) test the cyto-nuclear discordance by reconstructing high-resolution phylogenetic trees.

Results

Chloroplast genome structure of Ilex

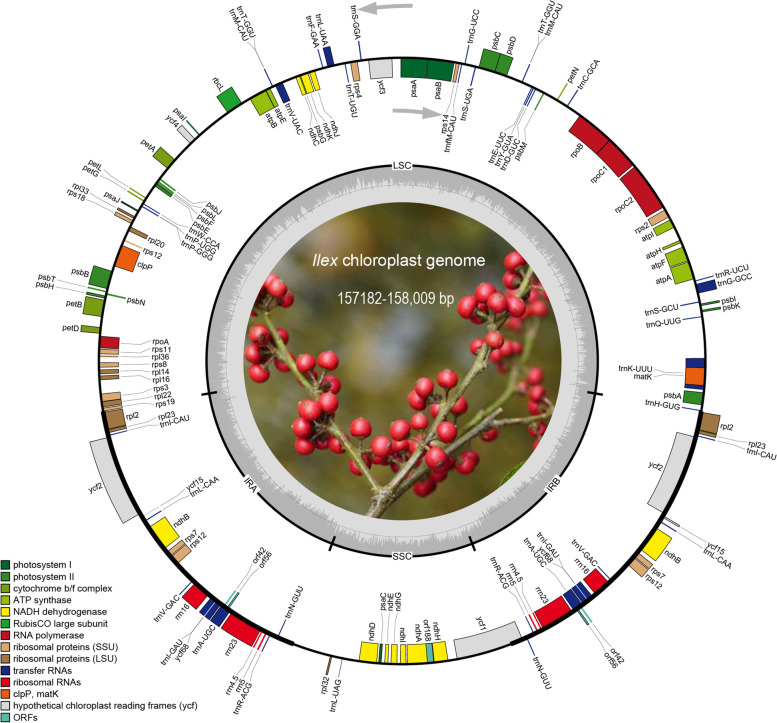

All seven newly sequenced Ilex chloroplast genomes possessed typical vascular plant quadripartite structure, which consisted of two single-copy regions (LSC and SSC) that were separated by a pair of inverted repeats (IRa and IRb) (Fig. 1). The length of the newly sequenced chloroplast genomes ranged from 157,182 bp (I. zhejiangensis) to 158,009 bp (I. dasyphylla). The length of the LSC regions ranged from 86,575 bp (I. zhejiangensis) to 87,389 bp (I. yunnanensis), SSC regions ranged from 18,228 bp (I. yunnanensis) to 18,447 bp (I. lohfauensis), and IR regions ranged from 26,065 bp (I. viridis) to 26,108 bp (I. yunnanensis) (Table 1). The GC content ranged from 37.62% (I. dasyphylla) to 37.69% (I. zhejiangensis) (Table 1). All newly assembled plastomes contained 117 genes, including 82 protein-coding, 31 tRNA, and four rRNA genes, except for I. dasyphylla, which had 83 protein-coding genes (Tables 2 and 3). All chloroplast genomes had the same gene order and arrangement.

Fig. 1.

Gene circle maps of seven newly sequenced Ilex species. The colored bars indicate different functional groups. Thick lines of the large circle indicate the extent of the inverted repeat regions (IRa and IRb), which separate the genome into small (SSC) and large (LSC) single copy regions. Genes on the inside and outside of the large circle are transcribed clockwise and counterclockwise, respectively. The darker gray columns in the inner circle correspond to the GC content, the light gray to AT content

Table 1.

Summary of complete chloroplast genomes of Ilex species included in the present study. PCG indicates protein-coding gene

| Taxon | Accession number | Gene number | Length (bp) | GC(%) | AT(%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCG | tRNA | rRNA | Full | Plastome | LSC | IRA/IRB | SSC | ||||

| Ilex asprella | NC_045274 | 94 | 37 | 8 | 139 | 157,856 | 87,265 | 26,075 | 18,441 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. asprella var. tapuensis | MT767004 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,671 | 87,161 | 26,065 | 18,380 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. championii | MT764248 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,468 | 86,878 | 26,074 | 18,442 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. chapaensis | MT764251 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,665 | 87,155 | 26,065 | 18,380 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. cinerea | MT764247 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,215 | 86,601 | 26,094 | 18,426 | 37.69 | 62.31 |

| I. cornuta | MT764252 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,216 | 86,607 | 26,091 | 18,427 | 37.69 | 62.31 |

| I. crenata | MW528027 | 88 | 38 | 8 | 134 | 157,988 | 87,414 | 26,076 | 18,422 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. dabieshanensis | MT435529 | 90 | 37 | 8 | 135 | 157,218 | 86,723 | 26,034 | 18,427 | 37.69 | 62.31 |

| I. dasyphylla | This study | 92 | 40 | 8 | 140 | 158,009 | 87,388 | 26,105 | 18,411 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. dasyphylla | MT764253 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 158,009 | 87,388 | 26,105 | 18,411 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. delavayi | KX426470 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,671 | 87,077 | 26,078 | 18,438 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. dumosa | KP016927 | 86 | 37 | 8 | 131 | 157,732 | 87,033 | 26,087 | 18,415 | 37.62 | 62.27 |

| I. ficoidea | MT764243 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,536 | 86,922 | 26,094 | 18,426 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. fukienensis | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,474 | 86,886 | 26,074 | 18,440 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. graciliflora | MT764249 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,119 | 86,506 | 26,093 | 18,427 | 37.61 | 62.39 |

| I. hanceana | MT764246 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,478 | 86,889 | 26,074 | 18,441 | 37.63 | 62.37 |

| I. integra | NC_044417 | 86 | 37 | 8 | 131 | 157,548 | 86,936 | 26,093 | 18,426 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. intermedia | MT471320 | 89 | 37 | 8 | 134 | 157,577 | 87,083 | 26,034 | 18,426 | 37.63 | 62.37 |

| I. kwangtungensis | MT764241 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 158,020 | 87,400 | 26,104 | 18,412 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. lancilimba | MT767005 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,998 | 87,382 | 26,105 | 18,406 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. latifolia | NC_047291 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,601 | 87,020 | 26,077 | 18,427 | 37.63 | 62.37 |

| I. lohfauensis | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,464 | 86,875 | 26,071 | 18,447 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. lohfauensis | MT764240 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,470 | 86,873 | 26,078 | 18,441 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. memecylifolia | MT764250 | 87 | 37 | 8 | 132 | 157,842 | 87,249 | 26,076 | 18,441 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. micrococca | MN830251 | 89 | 37 | 8 | 134 | 157,782 | 87,200 | 26,074 | 18,434 | 37.64 | 62.36 |

| I. paraguariensis | NC_031207 | 86 | 37 | 8 | 131 | 157,614 | 87,154 | 26,076 | 18,308 | 37.63 | 62.35 |

| I. polyneura | KX426468 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,621 | 87,140 | 26,061, 25,980 | 18,434 | 37.60 | 62.40 |

| I. pubescens | KX426467 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,741 | 87,143 | 26,081 | 18,436 | 37.61 | 62.39 |

| I. purpurea | MT471318 | 89 | 37 | 8 | 134 | 157,885 | 87,289 | 26,104 | 18,388 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. rotunda | MW292559 | 88 | 37 | 8 | 133 | 157,743 | 87,069 | 26,121 | 18,432 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. sp. | KX426469 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,611 | 87,137 | 26,020 | 18,434 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. suaveolens | MN830249 | 89 | 37 | 8 | 134 | 157,857 | 87,255 | 26,102 | 18,398 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. szechwanensis | KX426466 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,822 | 87,281 | 26,053 | 18,435 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. triflora | MT764242 | 87 | 36 | 8 | 131 | 157,706 | 87,183 | 26,065 | 18,393 | 37.67 | 62.33 |

| I. venusta | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,860 | 87,290 | 26,079 | 18,412 | 37.66 | 62.34 |

| I. viridis | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,673 | 87,150 | 26,065 | 18,393 | 37.68 | 62.32 |

| I. viridis | MN830250 | 89 | 37 | 8 | 134 | 157,701 | 87,177 | 26,065 | 18,394 | 37.67 | 62.33 |

| I. vomitoria | MT471319 | 90 | 36 | 8 | 134 | 157,328 | 86,920 | 26,005 | 18,398 | 37.66 | 62.34 |

| I. wilsonii | KX426471 | 95 | 40 | 8 | 143 | 157,918 | 87,341 | 26,073 | 18,431 | 37.62 | 62.38 |

| I. yunnanensis | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,833 | 87,389 | 26,108 | 18,228 | 37.65 | 62.35 |

| I. zhejiangensis | This study | 91 | 40 | 8 | 139 | 157,182 | 86,575 | 26,092 | 18,423 | 37.69 | 62.31 |

Table 2.

List of annotated genes in the chloroplast genomes of the Ilex species

| Function of Genes | Group of Genes | Gene Name |

|---|---|---|

| Protein synthesis and DNA-replication | Transfer RNAs | trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnfM-CAU, trnG-GCCa, trnG-UCC, trnH-GUG, trnK-UUUa,, trnL-UAAa,, trnM-CAU, trnQ-UUG, trnP-GGG, trnP-UGG, trnR-UCU, trnS-GCU, trnS-GGA, trnS-UGA, trnT-GGU (× 2), trnT-UGU, trnV-UACa,, trnW-CCA, trnY-GUA, trnA-UGCa, (× 2), trnI-CAU (× 2), trnI-GAUa, (× 2), trnL-CAA (× 2), trnL-UAG, trnN-GUU (× 2), trnR-ACG (× 2), trnV-GAC (× 2), trnM-CAU |

| Ribosomal RNAs | rrn4.5 (× 2), rrn5 (× 2), rrn16 (× 2), rrn23 (× 2) | |

| Ribosomal protein large subunit | rpl33, rpl20, rpl36, rpl14, rpl16, rpl22, rpl32, rpl2a, (× 2), rpl23 (× 2) | |

| Ribosomal protein small subunit | rps2, rps14, rps4, rps18, rps11, rps8, rps3, rps19, rps12a, (× 2), rps7 (× 2) | |

| Subunits of RNA polymerase | rpoA, rpoB, rpoC1a,, rpoC2 | |

| Photosynthesis | photosystem I | psaA, psaB, psaC, psaI, psaJ |

| Photosystem II | psbA, psbB, psbC, psbD, psbE, psbF, psbG, psbH, psbI, psbJ, psbK, psbL, psbM, psbN, psbT, lhbA | |

| ATP synthase | atpA, atpB, atpE, atpFa,, atpH, atpI | |

| Large subunit Rubisco | rbcL | |

| Cythochrome b/f complex | petA, petBa,, petD, petG, petL, petN | |

| NADH-dehydrogenase | ndhAa,, ndhBa, (× 2), ndhC, ndhD, ndhE, ndhG, ndhH, ndhI, ndhJ, ndhK | |

| Other genes | Translation initiation factor | infA |

| Cytochrome c biogenesis | ccsA | |

| ATP-dependent protease | clpPb | |

| Maturase | matK | |

| Inner membrane protein | cemA | |

| Acetyl-CoA carboxylase | accD | |

| Genes of unknown function | Conserved hypothetical gene | orf42 (× 2), orf56 (× 2), orf188, ycf3b, ycf4, ycf1, ycf2 (× 2), ycf15 (× 2), ycf68 (× 2) |

Note: (× 2) indicates the number of repeat units is 2; aGene contains a single intron; bGene contains two introns

Table 3.

Genes with introns in the chloroplast genome of Ilex species

| Gene | Location | Exon I(bp) | Intron I (bp) | Exon II (bp) | Intron II (bp) | Exon III (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpl2 | IRa + IRb | 393 | 661 | 435 | ||

| rps12 | LSC + IRs | 114 | 543 | 232 | 26 | |

| clpP | LSC | 69 | 819 | 291 | 602 | 78 |

| atpF | LSC | 159 | 681 | 408 | ||

| rpoC1 | LSC | 456 | 756 | 1635 | ||

| ndhA | SSC | 552 | 1140 | 540 | ||

| ndhB | IRA | 777 | 679 | 756 | ||

| petB | LSC | 6 | 745 | 657 | ||

| trnA-UGC | IRa + IRb | 38 | 807 | 35 | ||

| trnI-GAU | IRa + IRb | 42 | 934 | 35 | ||

| trnL-UAA | IRa + IRb | 37 | 490 | 50 | ||

| trnV-UAC | IRa + IRb | 39 | 579 | 37 | ||

| trnG-GCC | LSC | 23 | 703 | 48 | ||

| trnK-UUU | LSC | 37 | 2562 | 35 | ||

| ycf3 | LSC | 126 | 727 | 228 | 749 | 153 |

Comparative analysis of genomic divergence and genome rearrangement

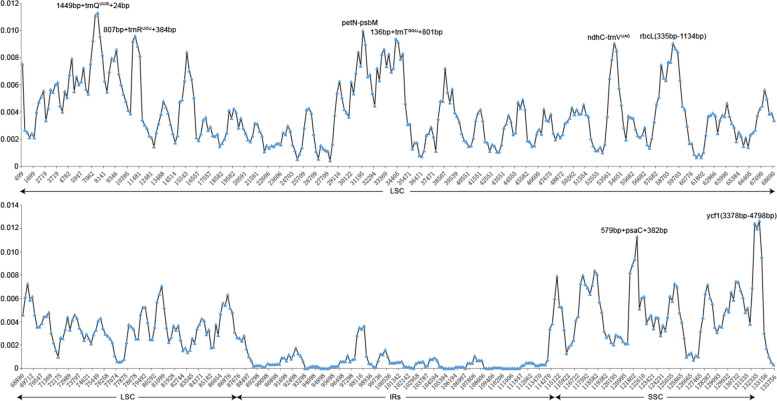

The diversity of nucleotide variability (Pi) for the seven newly assembled plastomes, combined with 34 plastomes obtained from GenBank, ranged from 0.000 to 0.01266, with an average of 0.00286. Based on the cutoff value of Pi ≥0.009, eight highly variable regions (807 bp + trnRUCU + 384 bp, 579 bp + psaC + 382 bp, ycf1 (3378 bp–4798 bp), 136 bp + trnTGGU + 801 bp, rbcL (335 bp–1134 bp), ndhC-trnVUAC, 1449 bp + trnQUUG + 24 bp, and petN-psbM) were identified; six of which (rbcL, trnQ, trnR, trnT, ndhC-trnV, and petN-psbM) were located in the LSC region, while two (psaC and ycf1) were from the SSC region (Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Table S1). The Pi value of the eight hypervariable loci ranged from 0.00754 (807 bp + trnRUCU + 384 bp) to 0.00955 (petN-psbM) (Table 4). At least four distinct gaps were observed in the chloroplast genome alignment, all located in the LSC region (Additional file 2: Fig. S1) within intergenic spacer regions, including cemA-ycf4, petA-psbJ, rpoB-trnC, and trnL-trnT. Four species (I. championii, I. fukienensis, I. hanceana, and I. lohfauensis) had a gap at the rpoB-trnC region, while three species (I. polyneura, I. pubescens, and I. rotunda) had a gap at the petA-psbJ region. Species that contained gaps at the cemA-ycf4 region also contained gaps at the trnL-trnT region, which included I. cinerea, I. cornuta, I. dabieshanensis, I. ficoidea, I. graciliflora, I. intermedia, I. latifolia, I. zhejiangensis, and Ilex sp. However, two species, I. delavayi, and I. integra only had one of these gaps, which was at the cemA-ycf4 region. Upon manual checking, these variations represented indels, ranging from about 210 bp (petA-psbJ) to 379 bp (rpoB-trnC) in length. Genome synteny of the 41 chloroplast genomes revealed no large gene rearrangement events (Additional file 2: Fig. S2). In addition, a total of 2947 polymorphic, 1630 singleton variable, and 1317 parsimony-informative sites were detected in the 41 chloroplast genome sequences.

Fig. 2.

Sliding-window analysis showing the nucleotide diversity (Pi) values of the aligned Ilex chloroplast genomes

Table 4.

Variable site analyses in the chloroplast genomes of Ilex species

| Region | Total number of sites | Polymorphic sites | Singleton variable sites | Parsimony informative sites | Nucleotide diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSC | 88,362 | 2182 | 1200 | 982 | 0.00384 |

| IRa | 26,162 | 94 | 57 | 37 | 0.00055 |

| SSC | 18,460 | 582 | 319 | 263 | 0.00498 |

| IRb | 26,167 | 89 | 54 | 35 | 0.00050 |

| Plastome | 159,151 | 2947 | 1630 | 1317 | 0.00286 |

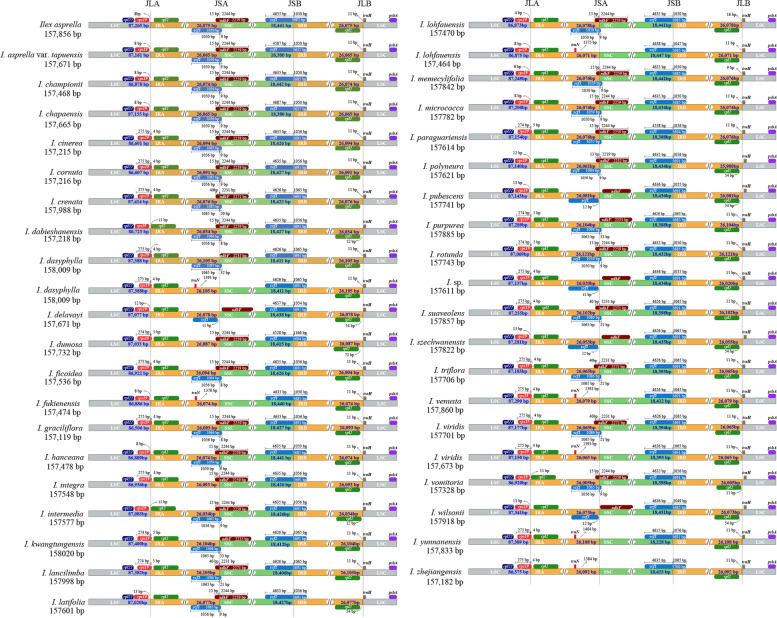

Expansion and contraction of the IR regions

Comparative sequence analysis of the Ilex species showed that chloroplast genome structure and the number and sequence of genes were highly conserved. However, some structure and size variations at the IR boundaries were detected. The lengths of IRs among all Ilex species analyzed were relatively consistent: I. vomitoria had the shortest (26,005 bp), while I. rotunda had the longest (26,121 bp). About half (22/41) of the Ilex plastomes had LSC/IRa junctions located in rps19, with 4 to 5 bp crossing into the IRa region, which indicated an expansion of the IR in these species (Fig. 3). The majority of IRa/SSC junctions were located adjacent to ycf1 and ndhF, and overlap of 22 to 61 bp between ndhF and ycf1 was detected in 26 species. However, in I. dasyphylla, I. fukienensis, I. lohfauensis, I. venusta, I. viridis, I. yunnanensis, and I. zhejiangensis, ndhF and ycf1 were absent from the IRa/SSC junction. In all analyzed Ilex chloroplast genomes, the SSC/IRb junction was located in ycf1, with an extension into the IRb region ranging from 1047 bp (I. lohfauensis) to 1166 bp (I. dumosa) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the SC/IR junctions among the 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes. JLA, LSC/IRa boundary; JSA, SSC/IRa boundary; JSB, SSC/IRb boundary; JLB, LSC/IRb boundary

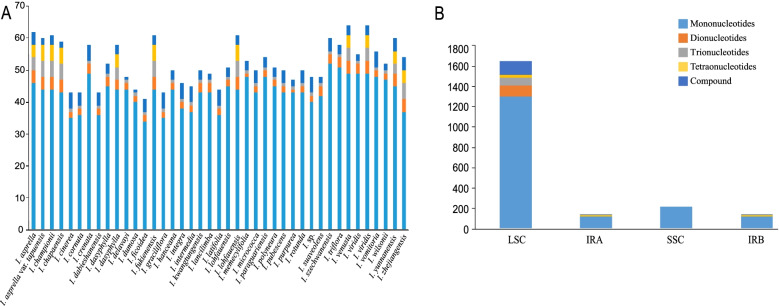

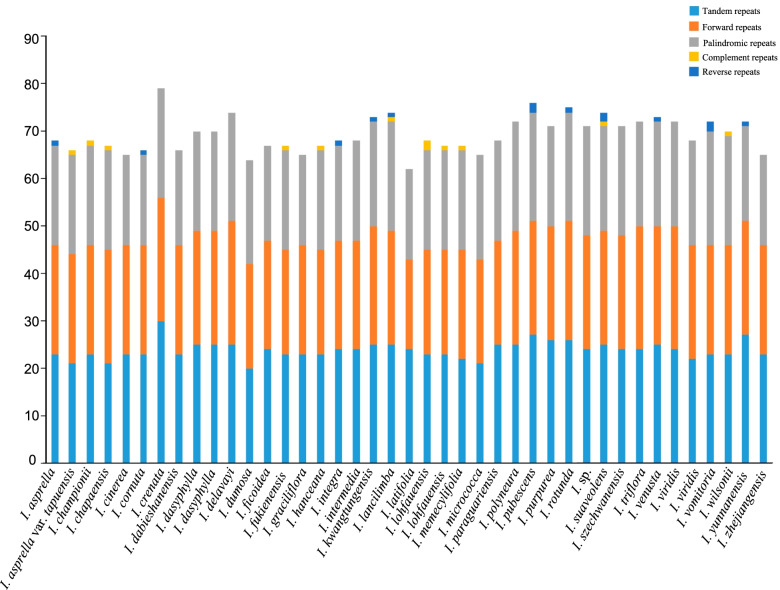

SSR polymorphisms and long repeat sequence analysis

A total of 2146 simple sequence repeats (SSRs) were detected among the 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes, ranging from 10 to 168 bp (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Table S2). Mononucleotide repeats were most abundant (1771), while tetranucleotide repeats were rarest (49). The number of di-, trinucleotide, and compound repeats were 109, 79, and 138, respectively. Of the mononucleotide repeats, A/T repeats were most frequent (1769), while C/G repeats were only detected from two taxa (I. asprella var. tapuensis and I. micrococca). Dinucleotide repeats were represented by only the AT/TA motif; while tri- and tetranucleotides contained motifs AAT/ATT, CAG/CTG, and TTC/GAA, as well as AAAG/CTTT, ATAA/TTAT, ATTT/AAAT, TATT/AATA, and TCTT/AAGA repeats, respectively. Most SSRs were located in LSC regions (1649), followed by IR (275), and SSC (222) regions.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of simple sequence repeats (SSR) in the 41 chloroplast genomes of Ilex species. A Number of different SSR types detected in the 41 genomes; B Number of different SSR types in LSC, SSC and IR regions

We detected a total of 2843 large repeats between the 41 species (Fig. 5, Additional file 1: Table S3); I. crenata had the highest (79), while I. latifolia the fewest (62), large repeats. All species involved had forward, palindromic, and tandem repeats, but only 11 had complementary and/or reverse repeats.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of long repeats in 41 chloroplast genomes of Ilex showing the number of complementary, forward, palindromic, reverse, and tandem long repeats

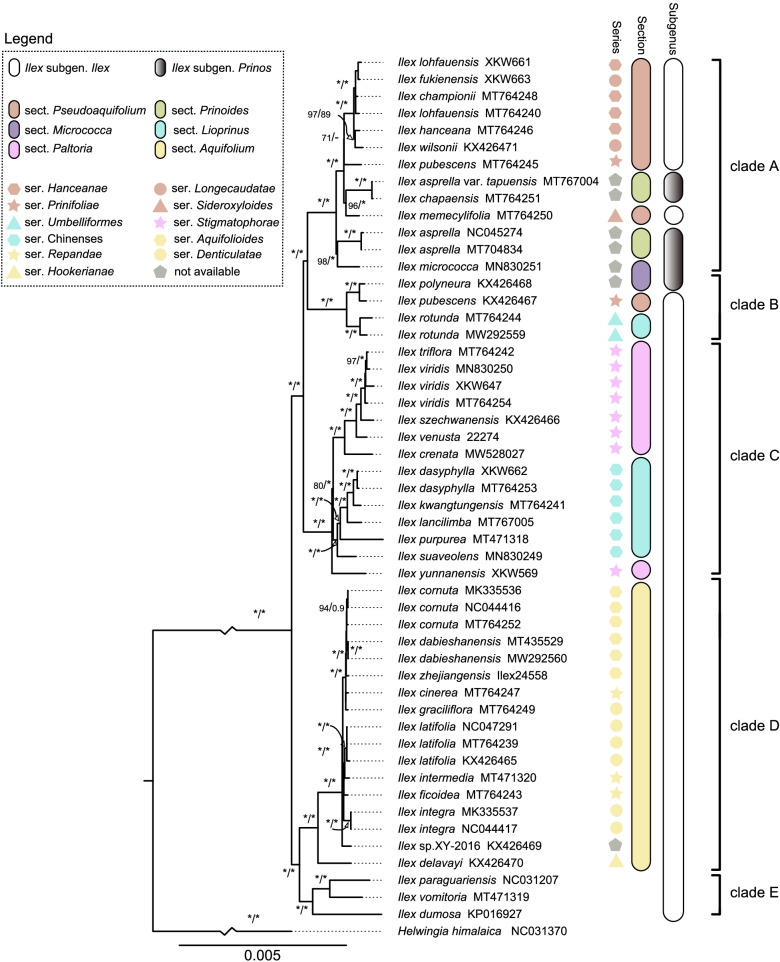

Phylogenomic analyses

We reconstructed phylogenetic relationships from 52 complete chloroplast genomes and 75 protein-coding genes using both maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods, and used the closely related species Helwingia himalaica (NC031370) as an outgroup [26]. The total alignment lengths of the complete plastome and the protein-coding gene matrices were 157,836 bp and 68,601 bp, respectively. The complete plastome matrix contained 8869 variable and 1735 parsimony informative sites, while the protein-coding gene matrix contained 2247 and 458 variable and parsimony informative sites, respectively. The backbones of trees constructed using ML and BI methods were almost identical for each sequence matrix and supported the monophyly of Ilex (Fig. 6; ML BS: 100%; BI PP: 1.00); thus, we present only the ML tree here, with posterior probability (PP) values shown (Fig. 6, Additional file 2: Fig. S3).

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic trees inferred from maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses based on the complete chloroplast genomes. Numbers near the nodes are ML bootstrap support values (BS, left of the slashes) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP, right of the slashes). 100% BS or 1.00 PP are indicated by asterisks. Incongruences between the BI and ML trees are indicated by dashes. Hu’s classification is illustrated by color graphic pattern. Recognized groups (major clades) were also marked by the right-hand black bar

Based on our phylogenetic analyses, and with consideration of macro-morphological and distribution information, we recognize five highly supported clades within Ilex (clades A–E) that were well resolved (Fig. 6; ML BS: 100%; BI PP: 1.00). Clade A comprises one species (I. micrococca) of sect. Micrococca, two species (I. asprella and I. chapaensis) and one variety (I. asprella var. tapuensis) of sect. Prinoides, and seven species (I. championii, I. fukienensis, I. hanceana, I. lohfauensis, I. memecylifolia, I. pubescens, and I. wilsonii) of sect. Pseudoaquifolium. Clade B is sister to clade A, and includes three species (I. polyneura, I. pubescens, and I. rotunda). Clade C contains five species (I. dasyphylla, I. kwangtungensis, I. lancilimba, I. purpurea, and I. suaveolens) from sect. Lioprinus and six species (I. crenata, I. szechwanensis, I. triflora, I. venusta, Ilex viridis, and I. yunnanensis) from sect. Paltoria. Clade D includes members from sect. Aquifolium, and is sister to Clade E, which only contains three species (I. dumosa, I. paraguariensis, and I. vomitoria). Only sect. Aquifolium was resolved as monophyletic, while the other five sections (Lioprinus, Micrococca, Paltoria, Prinoides, and Pseudoaquifolium) and six series (Denticulatae, Hanceanae, Longecaudatae, Prinifoliae, Repandae, and Stigmatophorae) were not. Interspecific relationships within each clade were generally well resolved with high support.

Discussion

Comparison Ilex chloroplast genomes

We found that Ilex possesses typical, quadripartite chloroplast genomes at sizes consistent with most land plants [23]. The 41 chloroplast genomes analyzed here had highly conserved structure, with minor variation between species. Expansion and contraction events at SC/IR boundaries often give rise to variation in chloroplast genome length [27], but Ilex plastomes varied by at most 901 bp in length. Although we detected small variations around IR junctions, the IR regions of the Ilex chloroplast genomes examined showed only modest expansions or contractions; IR regions varied from 25,080 to 26,121 bp, while LSC regions varied by about 900 bp (Table 1).

Variation in intergenic spacer regions, as well as gene loss and gain, also play important roles in shaping plant chloroplast genomes [23, 28]. In the seven newly sequenced chloroplast genomes, except for I. dasyphylla, all species lacked the gene psbI. Plastid gene loss has been previously documented in Ilex—specifically, deletions in the trnT-trnL and ycf4-cemA spacers of I. graciliflora [29]—which suggests that gene loss may be a relatively more common force influencing Ilex plastome architecture.

Repetitive sequence analysis

Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (SSRs) are commonly employed in population genetics and evolutionary studies because of their high rate of polymorphism and abundant variation at the species level [30]. We identified a total of 2146 SSR loci from the 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes. Few population genetic studies have used SSRs in Ilex, and these newly identified loci will facilitate future research into genetic diversity, structure, and phylogeography at the population, intraspecific, and cultivar levels in Ilex.

Long repeat sequences with lengths greater than 30 bp play important roles in creating insertion/deletion mismatches and rearrangements that lead to genomic variation [31–34]. We found that the number of long repeat sequences in Ilex is high compared to some other angiosperm clades (e.g., 364 long repeats in Oxalidaceae [35]; 403 in Veratrum [36]; 32 in Oresitrophe rupifraga, and 34 in Mukdenia rossiiand [37]). Among these long repeats, forward, palindromic, and tandem repeats were rather common, accounting for 33.84, 30.81, and 34.44% of the total number of repeats, respectively, while complementary and reverse repeats were quite rare, only accounting for 0.42 and 0.49%, respectively.

Hypervariable regions

Hypervariable regions often provide a wealth of phylogenetic information and can be used to delimit closely related taxa [38, 39]. In general, IR regions are more highly conserved than SSC and LSC regions [40]. We identified eight hypervariable regions in Ilex plastomes, including four genes and four genes with flanking regions. Consistent with angiosperm-wide patterns of plastomes variability [32, 33], all hypervariable loci were distributed in the SC regions, while IR regions exhibited low variation.

To date, phylogenetic analyses of Ilex have been based on a handful of plastid markers (mainly atpB-rbcL, psbA-trnH, rbcL, and trnL-trnF), which could not resolve many interspecific relationships [1, 2, 10, 13, 15, 41–43]. When comparing these markers to the highly variable regions identified here, only one (rbcL) has been used to construct phylogenies. We believe that these eight highly variable regions will be useful for phylogenetic inference and DNA barcoding in Ilex. However, further studies are required to evaluate the strength of these regions for identifying and delimiting species.

Phylogenetic inference

There have been numerous attempts to resolve relationships amongst major Ilex lineages and test the consistency between molecular phylogenetics and traditional taxonomic systems based on morphology evidence [10–15, 26, 41]. A dearth of genetic data has resulted in poor resolution at the species level and weak support at most nodes in the Ilex phylogeny [10, 12–14, 26, 41]. These limitations can be addressed by using longer and more variable DNA sequences [44], such as complete chloroplast genomes [16, 21, 29, 45].

We present a well resolved and highly supported phylogeny of Ilex, and—in combination with macro-morphological and distribution information—suggest five clades (A-E) that are not generally congruent with traditional taxonomic systems. Clades A-E were largely consistent with previous plastid phylogenies, but relationships among clades differed significantly [10, 13, 15]. Our results showed that the American groups (Clade E) and the Eurasia groups (Clade F) were sister, and together formed the earliest diverging Ilex lineage, sister to a large clade containing the mostly Asian Clades A–C. In contrast, Manen [13] found the American (Group 3) and Eurasia (Group 4) groups to be among the most recently diverged lineages. The discordance between these results likely stems from the choice of loci included in analyses; previous studies have generally used less variable regions that led to low resolution among major clades [10, 13].

Our results highlight inconsistencies between molecular phylogenetics and traditional taxonomic systems. Almost all traditionally recognized subgenera, sections, and series included in our analysis were paraphyletic (all but sect. Aquifolium). Although the resolution of earlier phylogenetic trees was quite low, they indicated significant cyto-nuclear discordance, with nuclear phylogenies generally more consistent with traditional morphological classifications [13]. We confirmed the incongruences between plastid data and morphological systems by improving the resolution of the plastid phylogeny using complete chloroplast genomes.

Species found in close geographic proximity are often assumed to be closely related. This is accurate for most of the Ilex species in our study, including I. cornuta, I. dasyphylly, I. latifolia, and I. integra. However, both I. pubescens and I. lohfauensis were non-monophyletic in our analysis: the two accessions of I. pubescens were placed in two distinct clades (A and B), while the two accessions of I. lohfauensis were paraphyletic with respect to I. championii. Three samples of I. viridis were placed with the morphologically similar species I. trifloral. Non-monophyletic species may result from chloroplast capture or hybridization events [13, 41, 43], or stem from misidentification. Further phylogenetic studies are needed to continue to clarify relationships and taxonomy in Ilex.

Conclusions

We conducted comparative and phylogenetic analyses of 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes, including seven newly sequenced taxa. To reach a more complete understanding of the evolutionary history of the clade, future studies should focus on phylogenetic reconstructions based on nuclear DNA. We suggest using low-copy nuclear genes from genome-skimming data, which can provide better resolution than traditional, short nuclear DNA markers (e.g., ITS). Incorporating nuclear phylogenies with existing phylogenies based on complete chloroplast genomes, as well as morphology, with enhance our understanding of the complex evolutionary history of Ilex.

Materials and methods

Taxon sampling, DNA extraction, and sequencing

Seven species of Ilex (I. dasyphylla, I. fukienensis, I. lohfauensis, I. venusta, I. viridis, I. yunnanensis, I. zhejiangensis Ilex fukienensis, I. venusta, and I. zhejiangensis) were collected from their native ranges in China. Fresh leaf tissues were collected in the field and stored in silica gel prior to DNA extraction. Voucher specimens were prepared and deposited at the herbarium of Nanjing Forestry University (NF). In addition, 34 complete chloroplast genomes of Ilex species that are publicly available in NCBI GenBank were downloaded with annotations (Additional file 1: Table S4). Based on the classification of Ilex that is generally accepted [25], the current dataset comprised species from six sections and 11 series of the genus Ilex.

Total genomic DNA was extracted using the Plant Genomic DNA Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA extractions were visualized on agarose gels and quantified using a Qubit 2.0 (Life Technologies) for integrity, purity, and concentration. The qualified DNA (≥50 ng) was used to construct a paired-end (2 × 150 bp) library, and sequencing was conducted on a HiSeq X Ten platform (Illumina, USA).

Chloroplast genome assembly and annotation

Raw reads were filtered with fastp v.0.20.0 software [46] to remove low-quality reads. The filtered data were then fed into the NOVOPlasty 2.6.3 [47] pipeline for genome assembly, with the rbcL gene sequence of I. latifolia (Accession number: KX897017) as the seed sequence and the chloroplast genome sequence of I. latifolia (Accession number: MN688228) as reference genome. A contig was obtained at the end of the process, and annotation was conducted using Plann [48], in which the annotated chloroplast genome of I. latifolia (Accession number: MN688228) was set as reference. Start and stop codons in the chloroplast genomes were manually corrected using DOGMA [49], and tRNA genes were verified with tRNA scan-SE v2.0.3 within in GeSeq [50] using default parameters. Circular chloroplast genome maps were visualized using OrganellarGenomeDRAW [51].

Comparative genomic analyses

Sequence alignment of the 41 complete chloroplast genomes was carried out using MAFFT v.7 [52] and the alignment was further trimmed using trimAI v1.2 using the “-gappyout” setting [53]. The expansions and contractions of IR regions were visualized using IRscope [54] online and then was manually checked. The nucleotide diversity (Pi) was estimated using DnaSP v.5 [55] with a step size of 200 bp and a window length of 800 bp. The genome variability across the 41 species of Ilex was assessed using mVISTA [56] in Shuffle-LAGAN mode. The Mauve version 2.3.1 [57] plug-in available in Geneious version 11.0.3 [58] was used to identify locally collinear blocks among the chloroplast genomes with default parameters.

Repeat sequence identification

The number of large repeats, including forward, palindromic, reverse, and complementary repeats were identified using onlineREPuter [59] according to the following criteria: sequence identities of 90%, cutoff point at ≥30 bp, Hamming distance set at 3, and a minimum repeat size of 30 bp. Tandem Repeat Finder [60] was used to analyze tandem repeat sequences with the default parameters. SSRs were identified using web-MISA [61], with minimum repeat number set at 10, 5, 4, 3, 3, and 3 for mono-, di-, tri-, tetra-, penta-, and hexanucleotides, respectively. Compound SSRs were detected by identifying independent SSRs that were separated by less than 100 nucleotides and were combined into one.

Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were conducted using 52 complete chloroplast genomes and 75 protein-coding genes. A total of 39 Ilex species from six sections and 11 series were included in the phylogenetic analyses. Based Yao et al. [26], Helwingia himalaica (Accession number: NC031370) was used as the outgroup. Genome alignment was carried out using MAFFT v.7 [52] and then trimmed using trimAI v1.2 with the “-gappyout” setting [53].

Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted using IQ-tree [62] with 10,000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBS) replicates [63]. According to Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the best fitting substitution models that were estimated using ModelFinder [64] were GTR + F + I + G4 for the complete chloroplast genome sequences and GY + F + R3 for the protein-coding genes, respectively. Bayesian inference (BI) analysis was carried out using MrBayes version 3.2 [65], as implemented in CIPRES [66]. The Markov chain Monte Carlo analysis was executed for 2,000,000,000 generations, with four chains (one cold and three heated), each starting with a random tree, and sampled at every 1000 generations. Convergence of runs was accepted when the average standard deviation (d) of split frequencies was < 0.01. The first 25% of the trees were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to construct majority-rule consensus trees. The final trees from both analyses were visualized using FigTree v.1.4.2 [67].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Sequence alignment of 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes using mVISTA with I. szechwanensis as a reference. The vertical scale indicates the percent identity, ranging from 50% to 100%. The horizontal axis shows the location within the plastomes. Genome regions are color-coded as exon, intron, and untranslated regions (UTRs). Figure S2. Mauve multiple alignment of 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes revealing no interspecific rearrangements. Figure S3. Phylogenetic trees inferred from maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses based on 75 protein-coding genes. Numbers near the nodes are ML bootstrap support values (BS, left of the slashes) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP, right of the slashes). 100% BS or 1.00 PP are indicated by asterisks. Incongruences between the BI and ML trees are indicated by dashes. Recognized groups (major clades) were also marked by the right-hand black bar.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wanyi Zhao, Zhongcheng Liu of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China, for their assistance in sample collection; Yubing Zhou (Jierui Biotech, Guangzhou, China) for data analysis of chloroplast genomes; and thank Dr. Ian Gilman at Yale University for his assistance with English language and grammatical editing.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization, K.X. and K.M; methodology, K.X. and K.M; formal analysis, K.X. and K.M; investigation, K.X.; resources, K.X.; data curation, K.X. and K.M; writing—original draft preparation, K.X.; writing—review and editing, K.X., S.Y. Lee, K.M and K.M; visualization, K.X. and K.M; supervision, K.X., L.M. and K.M; project administration, K.X. and L.M.; funding acquisition, K.X. and L.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB31000000), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20210612), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32100167 and 31870506), and the Nanjing Forestry University project funding (163108093).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed in this study were included in this published article and the Additional files. The complete chloroplast genomes of the seven newly sequenced Ilex species were submitted to GenBank and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1: Table S4. All raw reads are available in the short sequence archive under accession no. PRJNA768933. All complete genome sequences used in this study were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. No specific permits were required for the collection of specimens for this study. All materials used in the study were collected in public areas of China in compliance with the relevant laws of China. The formal identification of the plant material was carried out by Kewang Xu. Voucher specimens were prepared and deposited at the herbarium of Nanjing Forestry University (NF) and their collection numbers could be found in Additional file 1: Table S4.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Lingfeng Mao, Email: maolingfeng2008@163.com.

Kaikai Meng, Email: mengkk@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Loizeau PA, Barriera G, Manen JF, Broennimann O. Towards an understanding of the distribution of Ilex L. (Aquifoliaceae) on a world-wide scale. Biol Skr. 2005;55:501–520. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell M, Savolainen V, Cuénoud P, Manen JF, Andrews S. The mountain holly (Nemopanthus mucronatus: Aquifoliaceae) revisited with molecular data. Kew Bull. 2000;55:341–347. doi: 10.2307/4115646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loizeau PA, Savolainen V, Andrews S, Spichiger R. Aquifoliaceae. In: Kubitzki K, editor. Flowering plants. Eudicots, the families and genera of vascular plants. Berlin: Springer; 2016. pp. 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Filip R, López P, Giberti G, Coussio J, Ferraro G. Phenolic compounds in seven south American Ilex species. Fitoterapia. 2001;72(7):774–778. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(01)00331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang ZX, Zhou Y, Zeng YK, Zang SL, He PG, Fang YZ. Determination of active ingredients of Ilex purpurea Hassk and its medicinal preparations by capillary electrophoresis with electrochemical detection. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2006;39:2861–2875. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yi F, Zhao XL, Peng Y, Xiao PG. Genus llex L.: phytochemistry, ethnopharmacology, and pharmacology. Chin Herb Med. 2016;8:209–230. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao X, Zhang F, Corlett RT. Utilization of the hollies (Ilex L. spp.): A Review. Forests. 2022;13(1):94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yao X, Lu Z, Song Y, Hu XD, Corlett RT. A chromosome-scale genome assembly for the holly (Ilex polyneura) provides insights into genomic adaptations to elevation in Southwest China. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhab049. doi: 10.1093/hr/uhab049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Union for Conservation of nature and natural resources (IUCN). The IUCN red list of threatened species. 2021. https://www.iucnredlist.org/. Accessed 11 Aug 2021.

- 10.Cuénoud P, del Pero Martinez MA, Loizeau PA, Spichiger R, Andrews S, Manen JF. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the genus Ilex L. (Aquifoliaceae) Ann Bot (Oxford) 2000;85:111–122. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Setoguchi H, Watanabe I. Intersectional gene flow between insular endemics of Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) on the Bonin Islands and the Ryukyu Islands. Amer J Bot. 2000;87:793–810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manen JF, Boulter MC, Naciri-Graven Y. The complex history of the genus Ilex L. (Aquifoliaceae): evidence from the comparison of plastid and nuclear DNA sequences and from fossil data. Pl Syst Evol. 2002;235:79–98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manen JF, Barriera G, Loizeau PA, Naciri Y. The history of extant Ilex species (Aquifoliaceae): evidence of hybridization within a Miocene radiation. Molec Phylogen Evol. 2010;57:961–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottlieb AM, Giberti GC, Poggio L. Molecular analyses of the genus Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) in southern South America, evidence from AFLP and ITS sequence data. Amer J Bot. 2005;92:352–369. doi: 10.3732/ajb.92.2.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang L, Xu K, Fan Q, Peng H. A new species of Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) from Jiangxi Province, China, based on morphological and molecular data. Phytotaxa. 2017;298:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yao X, Tan YH, Liu YY, Song Y, Yang JB, Corlett RT. Chloroplast genome structure in Ilex (Aquifoliaceae) Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep28559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao X, Liu YY, Tan YH, Song Y, Corlett RT. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Helwingia himalaica (Helwingiaceae, Aquifoliales) and a chloroplast phylogenomic analysis of the Campanulidae. PeerJ. 2016;4:e2734. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu S. The evolution and distribution of the species of Aquifoliaceae in the Pacific area (1) Jap J Bot. 1967;42:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loesener T. Monographia aquifoliacearum. Part I. Nova Acta Acad Caes Leop-Carol German Nat Cur. 1901;78:1–589. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang SD, Jin JJ, Chen SY, Chase MW, Soltis DE, Li HT, et al. Diversification of Rosaceae since the late cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytol. 2017;214:1355–1367. doi: 10.1111/nph.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li HT, Yi TS, Gao LM, Ma PF, Zhang T, Yang JB, et al. Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat Plants. 2019;5:455–456. doi: 10.1038/s41477-019-0421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meng KK, Chen SF, Xu KW, Zhou RC, Li MW, Dhamala MK, et al. Phylogenomic analyses based on genome-skimming data reveal cyto-nuclear discordance in the evolutionary history of Cotoneaster (Rosaceae) Molec Phylogen Evol. 2021;158:107083. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2021.107083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mower JP, Vickrey TL. Structural diversity among plastid genomes of land plants. In: Chaw SM, Jansen RK, editors. Plastid genome evolution. Amsterdam and New York: Academic; 2018. p. 2e382. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Burleigh JG, Soltis DE. Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4623–4628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen SK, Ma HY, Feng YX. Aquifoliaceae. In: Wu ZY, Raven PH, Hong DY, editors. Flora of China. Beijing and St. Louis: Science Press and Missouri Botanical Garden Press; 2008. pp. 449–461. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yao X, Song Y, Yang JB, Tan YH, Corlett RT. Phylogeny and biogeography of the hollies (Ilex L., Aquifoliaceae) J Syst Evol. 2021;59(1):73–82. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wicke S, Schneeweiss GM, De Pamphilis CW, Müller KF, Quandt D. The evolution of the plastid chromosome in land plants: gene content, gene order, gene function. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;76:273e297. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9762-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolfe KH, Morden CW, Palmer JD. Function and evolution of a minimal plastid genome from a nonphotosynthetic parasitic plant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(22):10648–10652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kong BLH, Park HS, Lau TWD, Lin Z, Yang TJ, Shaw PC. Comparative analysis and phylogenetic investigation of Hong Kong Ilex chloroplast genomes. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-84705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebert D, Peakall R. Chloroplast simple sequence repeats (cpSSRs): technical resources and recommendations for expanding cpSSR discovery and applications to a wide array of plant species. Mol Ecol Resour. 2009;9:673–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weng M, Blazier JC, Govindu M, Jansen RK. Reconstruction of the ancestral plastid genome in Geraniaceae reveals a correlation between genome rearrangements, repeats, and nucleotide substitution rates. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:645e659. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asaf S, Khan AL, Khan MA, Shahzad R, Lubna KSM, et al. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and comparative analysis of loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) with related species. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang YY, Yang ZR, Huang S, An WL, Li J, Zheng XS. Comprehensive analysis of Rhodomyrtus tomentosa chloroplast genome. Plants. 2019;8:89. doi: 10.3390/plants8040089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian J, Song JY, Gao HH, Zhu YJ, Xu J, Pang XH, et al. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of the medicinal plant salvia miltiorrhiza. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li XP, Zhao YM, Tu XD, Li CR, Zhu YT, Zhong H. Comparative analysis of plastomes in Oxalidaceae: phylogenetic relationships and potential molecular markers. Plant Divers. 2021;43:281–291. doi: 10.1016/j.pld.2021.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang YM, Han LJ, Yang CW, Yin ZL, Tian X, Qian ZG, et al. Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of medicinally important Veratrum (Melanthiaceae) in China: insights into genomic characterization and phylogenetic relationships. Plant Divers. 2021. 10.1016/j.pld.2021.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Liu LX, Wang YW, He PZ, Li P, Lee J, Soltis DE, et al. Chloroplast genome analyses and genomic resource development for epilithic sister genera Oresitrophe and Mukdenia (Saxifragaceae), using genome skimming data. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:235. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4633-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li XW, Yang Y, Henry RJ, Rossetto M, Wang YT, Chen SL. Plant DNA barcoding: from gene to genome. Biol Rev Camb Phil Soc. 2015;90:157e166. doi: 10.1111/brv.12104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng CX, Hollingsworth PM, Yang J, He ZS, Zhang ZR, Li DZ, et al. Genome skimming herbarium specimens for DNA barcoding and phylogenomics. Plant Methods. 2018;14(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13007-018-0300-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo C, Huang WL, Sun HY, Yer H, Li XY, Li Y, et al. Comparative chloroplast genome analysis of Impatiens species (Balsaminaceae) in the karst area of China: insights into genome evolution and phylogenomic implications. BMC Genomics. 2021;22:571. doi: 10.1186/s12864-021-07807-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Manen JF. Are both sympatric species Ilex perado and Ilex canariensis secretly hybridizing? Indication from nuclear markers collected in Tenerife. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selbach-Schnadelbach A, Cavalli SS, Manen JF, Coelho GC, de Souza-Chies TT. New information for Ilex phylogenetics based on the plastid psbA-trnH intergenic spacer (Aquifoliaceae) Bot J Linn Soc. 2009;159:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi L, Li NW, Wang SQ, Zhou YB, Huang WJ, Yang YC, et al. Molecular evidence for the hybrid origin of Ilex dabieshanensis (Aquifoliaceae) PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147825. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Philippe H, Brinkmann H, Lavrov DV, Littlewood D, Manuel MG, Wörheide G, et al. Resolving difficult phylogenetic questions: why more sequences are not enough. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000602. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Su T, Zhang MR, Shan ZY, Li XD, Zhou BY, Wu H, et al. Comparative survey of morphological variations and plastid genome sequencing reveals phylogenetic divergence between four endemic Ilex species. Forests. 2020;11(9):964. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen SF, Zhou YQ, Chen YR, Gu J. Fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1884–1890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dierckxsens N, Mardulyn P, Smits G. NOVOPlasty: de novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45:e18. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang DI, Cronk QC. Plann: a command-line application for annotating plastome sequences. Appl Plant Sci. 2015;3(8):1500026. doi: 10.3732/apps.1500026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wyman SK, Jansen RK, Boore JL. Automatic annotation of organellar genomes with DOGMA. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(17):3252–3255. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, et al. GeSeq–versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3. 1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martinez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amiryousefi A, Hyvönen J, Poczai P. IRscope: an online program to visualize the junction sites of chloroplast genomes. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):3030–3031. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(11):1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Frazer KA, Pachter L, Poliakov A, Rubin EM, Dubchak I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Suppl 2):273–279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Darling AC, Mau B, Blattner FR, Perna NT. Mauve: multiple alignment of conserved genomic sequence with rearrangements. Genome Res. 2004;14:1394–1403. doi: 10.1101/gr.2289704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kearse M, Moir R, Wilson A, Stones-Havas S, Cheung M, Sturrock S, et al. Geneious basic: an integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(12):1647–1649. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kurtz S, Choudhuri JV, Ohlebusch E, Schleiermacher C, Stoye J, Giegerich R. REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:4633–4642. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–580. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney R, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theor Appl Genet. 2003;106:411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35:518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ronquist F, Teslenko M, Van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, et al. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. Proceedings of the Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE), 14 November 2010, New Orleans, LA: Creating the CIPRES science gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees; 2010. p. 1–8.

- 67.Rambaut A. FigTree V1.4.2. 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 2: Figure S1. Sequence alignment of 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes using mVISTA with I. szechwanensis as a reference. The vertical scale indicates the percent identity, ranging from 50% to 100%. The horizontal axis shows the location within the plastomes. Genome regions are color-coded as exon, intron, and untranslated regions (UTRs). Figure S2. Mauve multiple alignment of 41 Ilex chloroplast genomes revealing no interspecific rearrangements. Figure S3. Phylogenetic trees inferred from maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) analyses based on 75 protein-coding genes. Numbers near the nodes are ML bootstrap support values (BS, left of the slashes) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP, right of the slashes). 100% BS or 1.00 PP are indicated by asterisks. Incongruences between the BI and ML trees are indicated by dashes. Recognized groups (major clades) were also marked by the right-hand black bar.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed in this study were included in this published article and the Additional files. The complete chloroplast genomes of the seven newly sequenced Ilex species were submitted to GenBank and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1: Table S4. All raw reads are available in the short sequence archive under accession no. PRJNA768933. All complete genome sequences used in this study were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1: Table S4.