Abstract

Background

Bronchodilators are the mainstay for symptom relief in the management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Aclidinium bromide is a new long‐acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) that differs from tiotropium by its higher selectivity for M3 muscarinic receptors with a faster onset of action. However, the duration of action of aclidinium is shorter than for tiotropium. It has been approved as maintenance therapy for stable, moderate to severe COPD, but its efficacy and safety in the management of COPD is uncertain compared to other bronchodilators.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of aclidinium bromide in stable COPD.

Search methods

We identified randomised controlled trials (RCT) from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), as well as www.clinicaltrials.gov, World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website and Almirall Clinical Trials Registry and Results. We contacted Forest Laboratories for any unpublished trials and checked the reference lists of identified articles for additional information. The last search was performed on 7 April 2014 for CAGR and 11 April 2014 for other sources.

Selection criteria

Parallel‐group RCTs of aclidinium bromide compared with placebo, long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABA) or LAMA in adults with stable COPD.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, assessed the risk of bias, and extracted data. We sought missing data from the trial authors as well as manufacturers of aclidinium. We used odds ratios (OR) for dichotomous data and mean difference (MD) for continuous data, and reported both with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration. We applied the GRADE approach to summarise results and to assess the overall quality of evidence.

Main results

This review included 12 multicentre RCTs randomly assigning 9547 participants with stable COPD. All the studies were industry‐sponsored and had similar inclusion criteria with relatively good methodological quality. All but one study included in the meta‐analysis were double‐blind and scored low risk of bias. The study duration ranged from four weeks to 52 weeks. Participants were more often males, mainly Caucasians, mean age ranging from 61.7 to 65.6 years, and with a smoking history of 10 or more pack years. They had moderate to severe symptoms at randomisation; the mean post‐bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) was between 46% and 57.6% of the predicted normal value, and the mean St George's Respiratory Questionnaire score (SGRQ) ranged from 45.1 to 50.4 when reported.

There was no difference between aclidinium and placebo in all‐cause mortality (low quality) and number of patients with exacerbations requiring a short course of oral steroids or antibiotics, or both (moderate quality). Aclidinium improved quality of life by lowering the SGRQ total score with a mean difference of ‐2.34 (95% CI ‐3.18 to ‐1.51; I2 = 48%, 7 trials, 4442 participants) when compared to placebo. More patients on aclidinium achieved a clinically meaningful improvement of at least four units decrease in SGRQ total score (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.31 to 1.70; I2 = 34%; number needed to treat (NNT) = 10, 95% CI 8 to 15, high quality evidence) over 12 to 52 weeks than on placebo. Aclidinium also resulted in a significantly greater improvement in pre‐dose FEV1 than placebo with a mean difference of 0.09 L (95% CI 0.08 to 0.10; I2 = 39%, 9 trials, 4963 participants). No trials assessed functional capacity. Aclidinium reduced the number of patients with exacerbations requiring hospitalisation by 4 to 20 fewer per 1000 over 4 to 52 weeks (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.88; I2 = 0%, 10 trials, 5624 people; NNT = 77, 95% CI 51 to 233, high quality evidence) compared to placebo. There was no difference in non‐fatal serious adverse events (moderate quality evidence) between aclidinium and placebo.

Compared to tiotropium, aclidinium did not demonstrate significant differences for exacerbations requiring oral steroids or antibiotics, or both, exacerbation‐related hospitalisations and non‐fatal serious adverse events (very low quality evidence). Inadequate data prevented the comparison of aclidinium to formoterol or other LABAs.

Authors' conclusions

Aclidinium is associated with improved quality of life and reduced hospitalisations due to severe exacerbations in patients with moderate to severe stable COPD compared to placebo. Overall, aclidinium did not significantly reduce mortality, serious adverse events or exacerbations requiring oral steroids or antibiotics, or both.

Currently, the available data are insufficient and of very low quality in comparisons of the efficacy of aclidinium versus tiotropium. The efficacy of aclidinium versus LABAs cannot be assessed due to inaccurate data. Thus additional trials are recommended to assess the efficacy and safety of aclidinium compared to other LAMAs or LABAs.

Keywords: Aged; Female; Humans; Male; Middle Aged; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists; Adrenergic beta‐2 Receptor Agonists/therapeutic use; Bronchodilator Agents; Bronchodilator Agents/therapeutic use; Disease Progression; Muscarinic Antagonists; Muscarinic Antagonists/therapeutic use; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive; Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/drug therapy; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Scopolamine Derivatives; Scopolamine Derivatives/therapeutic use; Tiotropium Bromide; Tropanes; Tropanes/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Effectiveness and safety of inhalers containing the drug aclidinium bromide for managing patients with stable COPD

Review question

We reviewed the evidence on the effectiveness and safety of aclidinium inhalers used by people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Background

COPD, also known as 'smoker's lung disease', includes conditions called emphysema and chronic bronchitis where there is airway narrowing that cannot be fully corrected. It is a progressive disease. COPD patients usually have breathing problems and a cough that produces a lot of phlegm. It is diagnosed by international guidelines set by the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Symptoms may worsen during flare‐ups. The main aims of treating COPD patients are to relieve symptoms, reduce flare‐ups and improve quality of life. Aclidinium is a new inhaled drug that widens the airways (a bronchodilator). It is delivered by an inhaler called Genuair or Pressair. We wanted to discover whether aclidinium was better or worse than using other inhalers or a dummy inhaler.

Study characteristics

The evidence was current to 7 April 2014. We included 12 studies involving 9547 COPD patients over a period of four to 52 weeks. These studies were sponsored by drug companies and were well designed. Both patients and the people doing the research did not know which treatment the patients were getting; although in one study one treatment was known to both parties. More men than women took part, and they were mostly Caucasians. They were in their 60s and had smoked a lot in their lives. These people had moderate to severe symptoms when they started treatment.

Key results

Aclidinium did not reduce the number of people with flare‐ups that need additional drugs. There was little or no difference in deaths or serious side effects between aclidinium and a dummy inhaler. Aclidinium inhalers improved quality of life more than the dummy inhalers.

People who took aclidinium had fewer hospital admissions due to serious flare‐ups. Based on our results, among 1000 COPD patients using a dummy inhaler over four weeks to one year 37 would have severe flare‐ups needing hospital admission. Only 17 to 33 patients out of 1000 would require hospital admission if they were using aclidinium inhalers. We also set out to compare this new medication with tiotropium, which is already used to treat COPD. There were only two studies for this comparison thus we could not be sure how aclidinium compared to tiotropium. We also could not compare aclidinium with another well known inhaler that contains the drug formoterol because of unreliable data.

Quality of the evidence

For the comparison of aclidinium inhalers and dummy inhalers, we are confident that there are benefits in terms of the number of hospitalisations and patients' quality of life; we are less certain about the numbers of flare‐ups needing additional drugs and serious side effects. We do not have enough information to assess any effect on the number of deaths. We did not have enough information to reliably compare aclidinium with tiotropium or formoterol.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Aclidinium bromide compared to placebo for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Aclidinium bromide compared to placebo for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Settings: community Intervention: aclidinium bromide Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Aclidinium bromide | |||||

| Mortality (all‐cause) Follow‐up: 6‐52 weeks | 5 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (2 to 10) | OR 0.92 (0.43 to 1.94) | 5252 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1 | |

| Exacerbations requiring steroids, antibiotics or both Follow‐up: 4‐52 weeks | 137 per 1000 | 122 per 1000 (105 to 141) | OR 0.88 (0.74 to 1.04) | 5624 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4 | |

| Quality of life Number of patients who achieved at least 4 units improvement in SGRQ total score Follow‐up: 12‐52 weeks | 396 per 1000 | 494 per 1000 (462 to 527) | OR 1.49 (1.31 to 1.7) | 4420 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high | The mean quality of life (SGRQ total score change from baseline) in the intervention groups was 2.34 lower (3.18 to 1.51 lower); (4442 participants; 7 studies) |

| Functional capacity Six‐minute walking distance | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No study assessed functional capacity |

| Hospital admissions due to exacerbations Follow‐up: 4‐52 weeks | 37 per 1000 | 24 per 1000 (17 to 33) | OR 0.64 (0.46 to 0.88) | 5624 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high2,3 | |

| Non‐fatal serious adverse events Follow‐up: 4‐52 weeks | 56 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (40 to 64) | OR 0.89 (0.7 to 1.14) | 5651 (10 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 ‐2 for imprecision: the CI includes the possibility of both appreciable benefit and harm. 2Chanez 2010 failed to report some outcomes of lung function in the published full text but it is unlikely to affect this outcome. 3Chanez 2010 is double blinded for aclidinium and placebo arms though it is open label for tiotropium arm with no study limitation for this comparison. 4 ‐1 for imprecision: the CI includes important benefit and potential harm.

Summary of findings 2. Aclidinium bromide compared to tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Aclidinium bromide compared to tiotropium for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Settings: community Intervention: aclidinium bromide Comparison: tiotropium | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Tiotropium | Aclidinium bromide | |||||

| Mortality (all‐cause) | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 329 (1) | See comment | No deaths were reported |

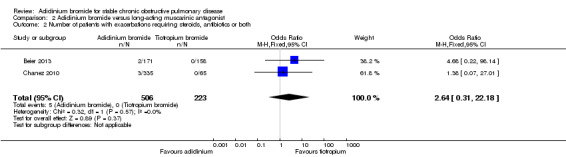

| Exacerbations requiring steroids, antibiotics or both Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks | 0 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (0 to 26)1 | OR 2.64 (0.31 to 22.18) | 729 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

| Quality of life St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies measured and reported quality of life for aclidinium and tiotropium |

| Functional capacity Six‐minute walk distance | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 0 (0) | See comment | No studies measured and reported functional capacity for aclidinium and tiotropium |

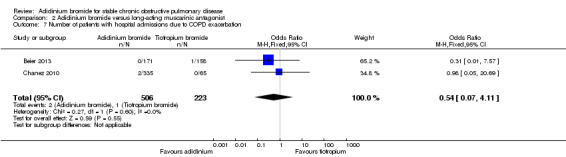

| Hospital admissions due to exacerbations Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks | 4 per 1000 | 2 per 1000 (0 to 18) | OR 0.54 (0.07 to 4.11) | 729 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

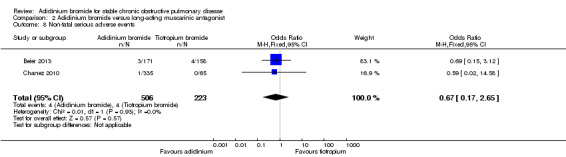

| Non‐fatal serious adverse events Follow‐up: 4‐6 weeks | 18 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (3 to 46) | OR 0.67 (0.17 to 2.65) | 729 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 The corresponding risk for aclidinium bromide was calculated using the risk difference to avoid having zero in both columns.

2 ‐1 for high risk of bias in Chanez 2010 because it was open label for tiotropium arm. 3Chanez 2010 failed to report some outcomes of lung function in the published full text but it is unlikely to affect this outcome. 4 ‐2 for imprecision: the CI includes the possibility of both appreciable benefit or harm.

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is "a common, preventable and treatable disease, characterised by persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles or gases" (GOLD 2013). Tobacco smoke is the major risk factor in the pathogenesis of COPD; chemicals, occupational exposures, indoor and outdoor air pollution are also recognised risk factors (GOLD 2013; Hogg 2009; MacNee 2006; TSANZ 2012; WHO 2012).

COPD is the third leading cause of death after heart disease and malignancy in the United States (CDC 2011) and accounts for approximately 30,000 deaths each year in the UK (NICE 2010). It was the fourth leading cause of mortality in 2004, with three million deaths worldwide (WHO 2008). Ninety per cent of deaths from COPD occurred in low and middle‐income countries in 2008 (WHO 2010). The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that COPD will become the third leading cause of death worldwide in 2030 due to a projected increase in smoking and environmental pollution (WHO 2012a). Exacerbations and co‐morbidities contribute to the overall severity of COPD in patients (GOLD 2013). Currently available prevalence data do not reflect the actual total burden of COPD because of under reporting, with diagnosis only being made when the disease is clinically apparent (GOLD 2013).

COPD also has a significant economic impact, mainly due to exacerbations. The total annual cost of COPD to the National Health Service (NHS) in the UK is estimated to be over GBP 800 million, for direct healthcare costs (NICE 2011). It accounts for 56% (EUR 38.6 billion) of the total cost of respiratory diseases in the European Union, while the estimated cost in the United States (US) is USD 29.5 billion and USD 20.4 billion, for direct and indirect costs respectively (GOLD 2013).

Acute exacerbations are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in COPD patients and are defined as "an event in the natural course of the disease characterised by a change in the patient's baseline dyspnoea, cough, and/or sputum, that is beyond normal day‐to‐day variations, is acute in onset and may warrant a change in medication in a patient with underlying COPD" (GOLD 2013).

Currently there is no cure for COPD. Apart from smoking cessation and long‐term oxygen therapy in severely hypoxic patients, other therapeutic options do not improve survival (GOLD 2013). Thus, the major goal of medication is to relieve symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve quality of life (ATS/ERS 2011; Chong 2012; GOLD 2013; Sutherland 2004; TSANZ 2012).

Management of stable COPD is multidisciplinary, with options such as smoking cessation (van der Meer 2012); education (Effing 2009); vaccination for influenza (Poole 2010) and pneumococcal infections (Walters 2010); breathing exercises (Holland 2012); pulmonary rehabilitation (Lacasse 2009); pharmacotherapy with inhaled bronchodilators, inhaled corticosteroids for severe COPD or frequent exacerbations (GOLD 2013; TSANZ 2012; Yang 2012), phosphodiesterase‐4 inhibitors (Chong 2011); long‐term domiciliary oxygen therapy (Cranston 2008); and lung volume reduction surgery (Tiong 2009). Regular long‐term use of oral corticosteroids is not recommended for stable COPD and is associated with an increased risk of systemic side effects (GOLD 2013; Walters 2009). Oral theophylline has a modest bronchodilator effect (Ram 2009) but is less effective than inhaled long‐acting bronchodilators (GOLD 2013). Mucolytic agents show a slight reduction in exacerbations but have no effect on the overall quality of life (Poole 2012). Neither of these medications are routinely recommended for stable COPD (GOLD 2013). Long‐acting bronchodilators, either a long‐acting beta2‐agonist (LABA) (Nannini 2012; Welsh 2011) or a long‐acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) (Karner 2012), are the first‐line maintenance therapy for moderate to severe, stable COPD (GOLD 2013; NICE 2010).

Description of the intervention

Aclidinium bromide is a new long‐acting antimuscarinic agent that blocks the action of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on 23 July 2012 for use in moderate to severe, stable COPD patients (FDA 2012). It is marketed as Tudorza Pressair by Forest Laboratories and Almirall in the US. It is a dry powder formulation (Sims 2011) and the FDA approved dosage is 400 µg inhaled twice daily. In Europe and the UK it has been launched as Eklira Genuair by Almirall.

It is delivered by a state of the art multidose dry powder inhaler (MDPI), termed Genuair or Pressair, which is preloaded with a one‐month supply of medication. The MDPI is specially designed with a visible dose level indicator with an anti‐double dosing mechanism, multiple feedback mechanisms to indicate successful inhalation, such as an audible click and a slightly sweet taste, as well as an end‐of‐dose lock‐out system to prevent further use after the final dose (Maltais 2012; Sims 2011).

How the intervention might work

Airway obstruction mediated by vagal cholinergic tone is the major reversible contributor to COPD (Jones 2011). Currently there are five known subtypes of muscarinic cholinergic receptors (M1 to M5), of which three (M1, M2 and M3) are present in the bronchial airway smooth muscle (Karakiulakis 2012; Maltais 2012).

Acetylcholine acts on M1 receptors to facilitate further neurotransmission from parasympathetic ganglia, and binds to M3 receptors located on the airway smooth muscle cells to induce bronchoconstriction. M2 receptors mediate feedback inhibition of acetylcholine release at the cholinergic nerve endings (Karakiulakis 2012; Sims 2011; Vogelmeier 2011).

Aclidinium bromide is a LAMA which inhibits the action of acetylcholine at the muscarinic receptors with approximately a six‐fold kinetic selectivity for M3 receptors compared to the M2 subtype, resulting in a more effective bronchodilator action with fewer M2 mediated cardiac side effects (Maltais 2012; Sims 2011). The onset of action of aclidinium bromide (30 minutes) is similar to ipratropium (30 minutes) but faster than tiotropium (80 minutes). The duration of action of aclidinium (t1/2 = 29 hours) is shorter than for tiotropium (t1/2 = 64 hours) but longer than for ipratropium (t1/2 = 8 hours) (Maltais 2012).

These muscarinic receptors are also present in other parts of the body, such as M1 receptors in the central nervous system (CNS); M2 in the heart; M3 in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), iris and sphincter; and M4 in the neostriatum, whereas the functional role of M5 receptors is unclear (Gavaldà 2010). Thus, the non‐selective blockade of muscarinic receptors has the potential for systemic side effects.

Aclidinium has been shown in preclinical and clinical studies to rapidly hydrolyse in the plasma into two inactive metabolites, with a very short plasma half life of 2.4 minutes, while the plasma half life for ipratropium is 96 minutes and for tiotropium it is more than six hours (Maltais 2012). This low and transient level in the plasma leads to less drug‐drug interaction and contributes to a more favourable safety profile.

Why it is important to do this review

Although a long‐lasting bronchodilator effect and favourable safety profile of aclidinium bromide has been shown in a number of clinical trials (Jones 2011; Jones 2012), the summarised safety and efficacy profile of this agent is lacking when compared to placebo or currently established treatment options such as LABAs or LAMAs. We aimed to fill this gap by performing a systematic review of the findings of all available randomised controlled trials to help clinicians provide evidence‐based, long‐term management of stable COPD.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of aclidinium bromide in stable COPD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a parallel‐group design comparing aclidinium bromide with placebo or a LABA or LAMA, both open‐label and blinded studies. Since COPD is a progressive disorder which deteriorates with time, we excluded cross‐over trials. We also excluded cluster‐randomised trials to avoid bias.

Types of participants

We included studies involving adults (over 18 years of age) diagnosed with moderate to severe COPD as defined by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 2013), American Thoracic Society (ATS), European Respiratory Society (ERS) (ATS/ERS 2011), Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ 2012), UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE 2010) or the WHO. Participants in the studies had evidence of airway obstruction (post‐bronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio of < 70% and FEV1 < 80% of predicted value) with clinical presentation of dyspnoea, chronic cough or sputum production with or without a history of smoking. We excluded studies which enrolled patients with bronchial asthma, bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis or other lung diseases.

Types of interventions

Aclidinium bromide versus placebo

Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting beta2‐agonist (LABA)

Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA)

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Mortality (all‐cause and respiratory)

Exacerbations requiring a short course of an oral steroid or antibiotic, or both

Quality of life measured by a validated scale, the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) or Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ)

Secondary outcomes

Change in lung function (FEV1, FEV1/FVC)

Functional capacity by six‐minute walking distance

Hospital admissions due to exacerbations or from all causes

Improvement in symptoms measured by the Transitional Dyspnoea Index (TDI)

Adverse events

Non‐fatal serious adverse events

Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy or adverse events

We assessed mortality and exacerbations as primary outcomes since exacerbations are the major cause of morbidity and mortality in COPD patients. We also classified quality of life as a primary outcome since it is one of the most important parameters that can measure both the subjective and objective well‐being of COPD patients, who have to live with this chronic disease. We recorded change in lung function from the baseline, exercise capacity, hospital admissions and symptom improvement as secondary outcomes as these may not directly reflect mortality and morbidity in COPD. For the safety profile of this new intervention (aclidinium bromide), we studied adverse events, non‐fatal serious adverse events and withdrawals from studies as secondary outcome measures.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and handsearching of respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 1 for further details). We searched all records in the CAGR coded as 'COPD' using the following terms:

Aclidinium* or "LAS34273" or "Tudorza" or "Eklira" or "Genuair" or "Pressair" or "LAMA" or "Muscarinic Antagonist*".

We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov (Appendix 2) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (WHO ICTRP) for additional trials. We searched all databases from their inception with no restrictions on language of publication. The initial search was conducted in March 2013 and it was updated in April 2014.

Searching other resources

We thoroughly checked the reference lists of all primary studies and review articles for additional references. We contacted corresponding authors of identified trials and asked them to identify other published and unpublished studies. We also contacted manufacturers and experts in the field. We searched the US FDA website (FDA 2012) for details of the clinical trials. In addition, we searched the manufacturers' websites (Forest Pharmaceuticals and Almirall) for additional information on the studies identified through the electronic searches. We had planned to translate studies published in a language other than English.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (HN and SM) independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author (ZS) who is an expert in the field. We included the trials meeting the criteria regardless of language or publication status (published, unpublished, in press and in progress). We recorded the excluded studies together with the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (HN and SM) independently extracted and recorded the data from included studies using standard data extraction forms. The data were cross‐checked. The data extraction included study characteristics: mainly study design, participants, interventions, primary and secondary outcome measures; and the analysis performed in the original studies. Where there were discrepancies, we consulted a third review author (ZS) to resolve the inconsistencies. In the case of insufficient or missing data, we contacted the corresponding authors of the studies for additional information. One of the review authors (HN) entered the data into Review Manager 5 software for analysis and the data were checked by another review author (SM).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (HN and SM) independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We resolved any disagreement by discussion or by involving a third assessor (ZS). We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

blinding of participants and personnel;

blinding of outcome assessment;

incomplete outcome data;

selective outcome reporting;

other bias.

We graded each potential source of bias as high, low or unclear. We recorded these judgements in the 'Risk of bias' tables accompanying the characteristics of each included study and summarised them in the 'Risk of bias' summary figure. We contacted the investigators of the RCTs for the details of procedures involved in the conduct of the trials and the replies were kept for evidence. We had planned to exclude trials with high risk of bias. We used the information from the assessment of risk of bias to carry out stratified analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We analysed dichotomous outcome data (such as mortality, exacerbations and withdrawals) using the Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). We had planned to apply the Peto odds ratio if events were rare.

We also calculated the number needed to treat (NNT) for dichotomous outcomes to reflect the number of patients necessary to obtain a beneficial or harmful outcome with the intervention.

Continuous data

We assessed continuous data variables (such as quality of life, symptoms, lung function and exercise capacity) as fixed‐effect mean differences (MD) with 95% CIs when the same scale was used to measure the outcome in all the included studies. We planned to use the standardised mean difference (SMD) when all studies assessed the same outcome but measured it in different ways. We preferentially applied the MD based on change from baseline over the MD based on absolute values.

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed the participants as the unit of analysis for dichotomous data. For continuous data we used the MD, which was the average change from baseline and not the absolute mean. For outcomes that may occur more than once, such as exacerbations, hospital admissions and adverse events, we analysed the number of participants with one or more events.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the investigators or study sponsors in order to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data, where possible. In cases where missing data were not available despite attempts to obtain the data, we recorded this information in our review. We performed sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of unknown status or assumptions made about missing data on participants who withdrew from the trials on the overall pooled result of the meta‐analysis. We followed the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) principle in the analysis of outcomes from the randomised trials, if appropriate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity between the trials by checking for poor overlap of the confidence intervals in the forest plot and by applying the Chi2 test, with a 10% level of significance. in each analysis we used the I² statistic to measure the percentage of inconsistency in results due to inter‐trial variability. When we identified substantial heterogeneity, we explored it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis. The level of statistical variation between the trials was considered as high if the I² value was more than 50%.

Assessment of reporting biases

We minimised reporting bias as a result of non‐publication of studies or selective outcome reporting by using a systematic search strategy, contacting study authors and manufacturers, and checking multiple references of the included studies. We also visually inspected funnel plots for asymmetry. If we suspected reporting bias because of the asymmetrical appearance of the funnel plot after exclusion of other reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, we had planned to contact the study authors requesting them to provide any missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we had planned to explore the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Data synthesis

We analysed the data using Review Manager 5. For pooling the outcomes of the studies, we used a fixed‐effect model if the I2 statistic was consistent with homogeneous results. We applied a random‐effects model for data synthesis when heterogeneity was identified (I2 > 50%) and it could not be explained by factors identified in the subgroup analyses. We combined dichotomous outcome variables using a Mantel‐Haenszel OR with 95% CI. For continuous outcome data, we analysed the results as MD with 95% CI. Where treatment effects were reported as MD with 95% CI or exact P value, we had planned to calculate the standard error, enter it with the MD, and combine the results using a fixed‐effect model generic inverse variance (GIV) analysis. We calculated the NNT from the pooled OR and assumed control risk (ACR) using the formula described in Section 12.5 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

We created summary of findings tables using the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) and using the GRADEpro software for overall grading of the quality of the evidence. We included the following outcomes.

Mortality (all‐cause and respiratory).

Exacerbations requiring a short course of an oral steroid or antibiotic, or both.

Quality of life.

Functional capacity by the six‐minute walking distance.

Hospital admissions due to exacerbations or all causes.

Non‐fatal serious adverse events.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If there was significant heterogeneity, we had planned to perform subgroup analysis in order to explain it. We had planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses.

Dose of aclidinium bromide (e.g. 200 µg; 400 µg).

Frequency of aclidinium bromide (once daily; twice daily).

Duration of treatment period (short‐term (12 weeks or less); long‐term (more than 12 weeks)).

Disease severity at baseline (FEV1 < 50% predicted; FEV1 ≥ 50% predicted).

Concurrent therapy with theophylline (dichotomised as yes or no).

We had planned to include the following outcomes in subgroup analyses.

Exacerbations.

Quality of life.

Change in lung function.

Sensitivity analysis

We assessed the robustness of our analyses by repeating the meta‐analysis after exclusion of studies with high risk of bias and those with unclear methodological data.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification and Characteristics of ongoing studies for complete details.

Results of the search

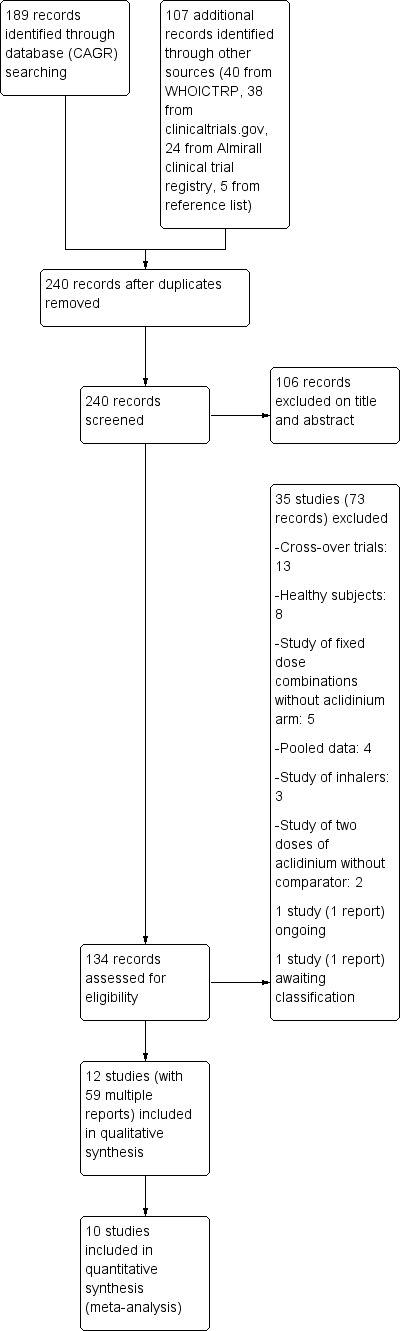

We conducted the initial search of the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR) on 14 March 2013 and the search of other sources (WHO ICTRP, Almirall, www.clinicaltrials.gov) on 28 June 2013 with no restriction on language. In January 2014, a second search was done for all resources. A third updated search was conducted on 7 April 2014 for the CAGR and on 11 April 2014 for other sources. We identified a total of 189 records from the CAGR (103 from the first search, 59 from the second, and 27 from the third search) and a total of 107 reports from other sources (40 from WHO ICTRP, 38 from www.clinicaltrials.gov, 24 from Almirall clinical trial registry, five from the reference lists of included studies). After removal of duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 240 records for eligibility and excluded 106 reports. We thoroughly studied the remaining 134 references for further assessment, retrieving full text articles where applicable and contacting manufacturers about unpublished trials. From our search, we excluded a total of 73 references for 35 studies with complete agreement between the authors. Details of studies which failed to meet the inclusion criteria were recorded in 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. One study (NCT01636401) had been completed but the results were not available and it was awaiting classification. Another ongoing study (ASCENT COPD) is expected to be completed by January 2018. We identified a total of 12 studies reported in 59 references that were eligible for inclusion. For details of the search results please see Figure 1. We asked Forest Research Institute if there were any additional study reports or references to studies that they had sponsored, but there was no reply. Two of the included studies (AUGMENT COPD; Sliwinski 2010) were in abstract form and upon request we received the required information for AUGMENT COPD from Almirall. They also provided data for ACLIFORM and NCT01572792. From the correspondence, NCT01572792 data was in the public domain at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) conference in San Diego in May 2014.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

See Table 3 for an overview of the included studies.

1. Overview of included studies.

| Duration of study | Number randomised | Severity of participants | Dose of aclidinium | Frequency of aclidinium | |

| ACCLAIM/COPD I | 52 weeks | 843 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200 µg | Once daily |

| ACCLAIM/COPD II | 52 weeks | 804 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200 µg | Once daily |

| ACCORD COPD I | 12 weeks | 561 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200, 400 µg | Twice daily |

| ACCORD COPD II | 12 weeks | 544 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200, 400 µg | Twice daily |

| ACLIFORM | 24 weeks | 1729 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

400 µg | Twice daily |

| ATTAIN | 24 weeks | 828 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200, 400 µg | Twice daily |

| AUGMENT COPD | 24 weeks | 1692 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

400 µg | Twice daily |

| Beier 2013 | 6 weeks | 414 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

400 µg | Twice daily |

| Chanez 2010 | 4 weeks | 464 | Moderate to severe (ATS) |

25, 50, 100, 200, 400 µg |

Once daily |

| Maltais 2011 | 6 weeks | 181 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

200 µg | Once daily |

| NCT01572792 | 28 weeks | 921 | Moderate to severe (GOLD) |

400 µg | Twice daily |

| Sliwinski 2010 | 4 weeks | 566 | Moderate to severe | 200 µg | Once daily |

Study design and duration

All trials were randomised, double‐blind, parallel group, multicentre studies. One trial (Chanez 2010) was open label for the tiotropium arm but double blind for the aclidinium and placebo arms. Six trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II;ATTAIN; Maltais 2011) studied aclidinium bromide and placebo. In the two trials of Beier 2013 and Chanez 2010, aclidinium bromide was assessed in comparison to both placebo and tiotropium bromide. Four trials (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792; Sliwinski 2010) studied aclidinium bromide versus placebo and formoterol along with a fixed dose combination of aclidinium and formoterol. NCT01572792 was the 28‐week extension study of AUGMENT COPD; the participants who agreed to participate in the extension study were kept on the same treatment and placebo arms as in the primary study.

The trials were of different study duration, ranging from four to 52 weeks, with a mean of 20.7 weeks. Six of the included studies were of short duration with two trials each having a duration of four weeks (Chanez 2010; Sliwinski 2010), six weeks (Beier 2013; Maltais 2011) and 12 weeks (ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II). The rest were long duration trials, with two studies of 52 weeks duration (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II), one study of 28 weeks duration (NCT01572792) and three studies of 24 weeks duration (ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD).

Setting

Most of the studies were based in the US and Canada (ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; AUGMENT COPD; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792). Other study locations were in Europe (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010), Australia and New Zealand (ACCLAIM/COPD II; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792), South Africa (ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN) and Korea (ACLIFORM).

Participants

A total of 9547 participants were randomised in 12 eligible studies. The largest trial was ACLIFORM with 1729 participants, whilst Maltais 2011 had the fewest participants with a total of 181. The remaining trials had numbers of participants ranging from 414 to 1692. The participants were current or former cigarette smokers with a smoking history of ≥ 10 pack years who were diagnosed with stable COPD according to the GOLD criteria and with a post‐bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio of < 70% and FEV1 < 80% of predicted value (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792). American Thoracic Society (ATS) criteria were used for diagnosis of COPD in patients with a smoking history of ≥ 10 pack years in one other trial (Chanez 2010). No detailed information was available for COPD diagnosis for Sliwinski 2010.

The trials were conducted in adults ≥ 40 years of age, including both male and female patients (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792). There was no specific description of age for the participants of Sliwinski 2010. The mean age of the participants ranged from 61.7 to 65.6 years and the majority were males. More than 90% of the participants were Causacians.

Participants had moderate to severe COPD according to the GOLD criteria with FEV1 ≥ 30% and < 80% in 10 studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792) and moderate to severe COPD according to the ATS criteria in one trial (Chanez 2010). Moderate to severe COPD patients were also enrolled in Sliwinski 2010, however the specific criteria used for severity assessment were not mentioned. The participants' mean post‐bronchodilator FEV1 was between 46% and 57.6% predicted normal in the trials. Their baseline mean FEV1 was 1.21 L to 1.51 L and the mean St George's Respiratory Questionnaire score (SGRQ) score ranged from 45.1 to 50.4.

Interventions

The participants underwent a two‐week run‐in period to ensure disease stability and washout of disallowed medications in eight trials with full text publications (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011).

An aclidinium dose of 200 μg was studied in the only or one of the intervention arms in eight trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011; Sliwinski 2010). A higher dose of 400 μg was studied in eight trials in one of the treatment arms (ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; NCT01572792). Three studies (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792) and Sliwinski 2010 studied aclidinium 400 μg and 200 μg, respectively, in comparison to formoterol and placebo together with fixed dose combination arms of aclidinium plus various doses of formoterol. NCT01572792 was the extension study of AUGMENT COPD in which the patients who completed AUGMENT COPD and agreed to participate were kept on the same intervention in a double‐blind fashion for another 28 weeks.

Aclidinium was given once daily in five trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011; Sliwinski 2010) while a twice daily dosage was used in the other seven trials (ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; NCT01572792).

Administration of aclidinium was by inhalation via a novel, multidose dry powder inhaler (Genuair) in 10 trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792; Sliwinski 2010), whereas either a Genuair or Pressair inhaler was used to deliver aclidinium in two studies (ACCORD COPD II; Beier 2013).

Tiotropium was delivered by the Handihaler in Beier 2013 and Chanez 2010; the latter was an open label study. Formoterol was studied as one of the interventions in ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792 and Sliwinski 2010 where it was given via a Genuair inhaler, which was not an approved inhaler for formoterol.

Concomitant medications

The participants were permitted to continue inhaled corticosteroids (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011), systemic corticosteroids (oral or parenteral) at doses equivalent to prednisone ≤ 10 mg/day or 20 mg every other day (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011) and oral sustained‐release theophylline (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010) provided the administration of these medications was stable for at least four weeks prior to screening; these medications had to be discontinued at least six hours before each study visit. Use of salbutamol or albuterol as rescue medication was also allowed (ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011). Oxygen therapy for less than 15 hours per day could be continued but not for two hours before study visits (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011). In ACCORD COPD I inhaled anticholinergics and LABAs were specifically mentioned as not allowed during the study period.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of the included studies were not identical with our review's primary outcomes because most of the individual trials assessed lung function as the primary outcome. Change from baseline in the morning pre‐dose (trough) FEV1 was the primary outcome in eight individual trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Chanez 2010), which was analysed as a secondary outcome in this review. Quality of life measured by the SGRQ, one of the primary outcomes of our review, was studied in the same eight trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Chanez 2010) either as the change from baseline or as the percentage of participants who achieved the minimal clinically important difference (that is ≥ four unit decrease in SGRQ total score). Most of the data for the other primary outcomes of mortality and exacerbations were well reported in the trials and the authors also provided further necessary information regarding the number of patients with exacerbations who required a short course of oral steroids or antibiotics, or both.

None of the included studies assessed functional capacity by the six‐minute walking distance, which was one of the secondary outcomes of our review. Specific data on hospital admissions due to exacerbations were also not mentioned in the published texts. However, the trial investigators provided the required data for this outcome. Other secondary outcomes of this review such as adverse events, non‐fatal serious adverse events and withdrawals were well reported. Data in the format required for the meta‐analysis of some of the secondary outcomes, especially lung function and TDI score, were kindly provided on request.

Funding

Studies were sponsored by Almirall, SA, Barcelona, Spain or Forest Laboratories, Inc, NY, USA.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 35 studies with 73 references as they failed to meet the eligibility criteria of our review (see Characteristics of excluded studies for details). Thirteen had a cross‐over study design; eight were phase one studies conducted in healthy participants; five lacked aclidinium as one of the treatment arms; four were reports of pooled data; three assessed the efficacy of and preferences for inhalers; and two studied aclidinium without a comparator.

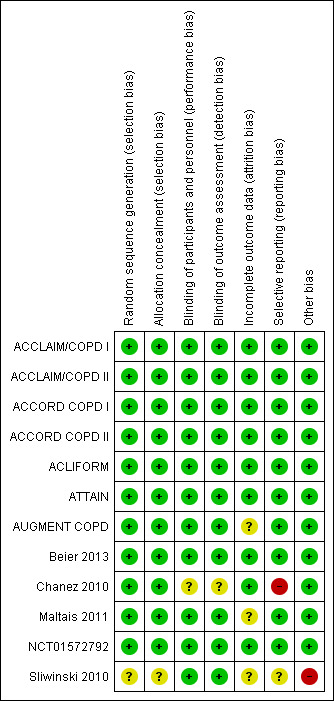

Risk of bias in included studies

Generally the included studies had good methodological quality with low risk of bias in most of the domains. Detailed assessment of risk of bias across all studies is presented in Characteristics of included studies; and Figure 2.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

One published study (Beier 2013) provided detailed information on random sequence generation by a computer generated schedule and allocation concealment via an interactive voice‐response system (IVRS). Although not explicitly described in the trial reports, from correspondence all Almirall‐sponsored trials applied a computer generated randomisation schedule which was prepared prior to initiating the trial. This was used to assign a treatment sequence to a randomisation number by the statistics and programming group within Almirall, according to the relevant standard operating procedures. The randomisation was performed in order to avoid any possible bias. The block size was determined in agreement with the clinical trial manager and the statistician and was not to be communicated to the investigators. In all studies, the IVRS (and in some cases an interactive web‐response system (IWRS)) was used to sequentially randomise patients to the intervention arms according to the randomisation ratio defined in each study as well as the block size that was determined by the sponsor (Appendix 3). Since Sliwinski 2010 was available as an abstract only, the information was insufficient to accurately assess the selection bias.

Blinding

All of the included studies had a double‐blind design with blinding of participants, caregivers and investigators. From correspondence, blinding was applicable for all study outcomes. In the placebo‐controlled studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II;ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013;Chanez 2010;Maltais 2011; NCT01572792; Sliwinski 2010) matching placebo was prepared to have the same external appearance with the same composition except for the active ingredient so that the aclidinium bromide and placebo were indistinguishable. In Chanez 2010 the tiotropium arm was open label, though the trial was double‐blinded for the aclidinium and placebo arms, causing a high risk of bias for the comparison with tiotropium but a low risk of bias for the comparison with placebo. For all trials, outcome assessors remained blinded with regard to the treatment assignments throughout the study period. Independent blinded experts and reviewers were assigned for analysing the spirometry data and dyspnoea scores (baseline dyspnoea index (BDI) and TDI). A double‐dummy technique was applied in Beier 2013 to ensure the double‐blinding of the trial in order to minimise bias.

Incomplete outcome data

All eight full text trials (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011) reported the number of dropouts, along with the reasons, for all the study arms. The number of and reasons for withdrawals for three trials (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792) were kindly provided on request by the investigators. However, Sliwinski 2010 did not report sufficient information to assess attrition bias. Nine of the included studies were rated as having a low risk of bias, either because the number of dropouts was considered low and was balanced between groups (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010), because withdrawal rates were high but evenly distributed across study arms (NCT01572792), or because withdrawal rates were regarded as acceptable given the methods of imputation reported in the published articles (ACCLAIM/COPD II; ATTAIN). Efficacy analyses and safety outcomes were performed on the intention‐to‐treat population which consisted of all randomised patients who received at least one dose of study medication and who had a baseline and at least one post‐baseline FEV1 assessment (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011). The last observation carried forward approach was used to impute missing data (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Chanez 2010). The remaining three trials were rated as unclear because of uneven dropouts and with no clear information on the methods of imputation (AUGMENT COPD; Maltais 2011) or because of unavailable data for dropouts (Sliwinski 2010).

Selective reporting

Seven published trials reported all the outcomes documented in the methodology section of the published manuscripts without any apparent bias (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011). The pre‐specified outcomes of the three trials (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792) were supplied on request, with no detectable reporting bias. There were two unreported outcomes, namely trough FVC and peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR), in the Chanez 2010 trial though these outcome measures were specified in the methodology. Limited information prevented full assessment of reporting bias for Sliwinski 2010.

Other potential sources of bias

The studies were sponsored and funded by manufacturers of aclidinium, Almirall, SA, Barcelona, Spain and Forest Laboratories, Inc, NY, USA, and some of the authors received financial support from the same, all of which were declared with no potential source of bias. Sliwinski 2010 was published as an abstract in 2010 but as of 2014 has failed to be published as full text, thus publication bias could not be ruled out. In ACCORD COPD II the baseline mean FEV1 was 1.40 L for the aclidinium 200 μg arm, 1.25 L for the aclidinium 400 μg arm and 1.46 L for the placebo arm. This relative imbalance in baseline lung function was taken into consideration in performing the meta‐analysis and judged as not causing a significant high risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

We included data from 10 studies for quantitative synthesis (meta‐analysis) in the comparison of aclidinium bromide versus placebo (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011). Two studies (Beier 2013; Chanez 2010) assessed tiotropium as well and these data were pooled for the comparison of aclidinium bromide versus LAMA. Four trials (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792; Sliwinski 2010) included both aclidinium and formoterol as intervention arms, however formoterol was given via the Genuair inhaler in these studies thus the data were considered inappropriate for comparison of aclidinium bromide versus LABA.

1. Aclidinum bromide versus placebo

Primary outcomes

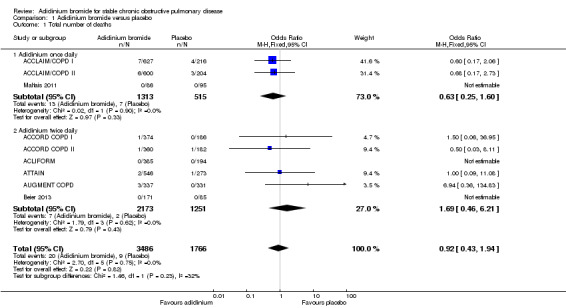

Mortality (all‐cause)

The number of deaths was reported in nine studies involving a total of 5252 participants (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011). Overall, there was no statistically significant difference in the number of deaths between the aclidinium and placebo groups (OR 0.92; 95% CI 0.43 to 1.94, low quality evidence; Table 1). Five patients out of 1000 (95% CI 2 to 10) patients receiving aclidinium died over 6 to 52 weeks, which was similar to the placebo group. Subgroup analysis of aclidinium once daily and twice daily showed an OR of 0.63 (95% CI 0.25 to 1.60; 3 trials, 1828 participants) and an OR of 1.69 (95% CI 0.46 to 6.21; 6 trials, 3424 participants) respectively (Analysis 1.1). There was no significant difference between the subgroups.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 1 Total number of deaths.

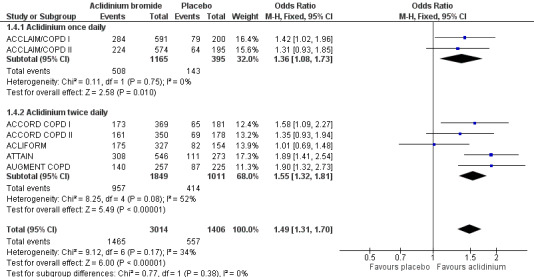

Exacerbations requiring a short course of an oral steroid or antibiotic, or both

Overall, data from 10 trials involving 5624 participants were pooled for patients experiencing at least one COPD exacerbation requiring a short course of oral steroids or antibiotics, or both (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011). The exact data for the trials which did not specifically mention the number of moderate exacerbations requiring oral steroids, antibiotics or both were kindly supplied by the sponsors. Aclidinium demonstrated a non‐significant reduction in moderate exacerbations compared to placebo (OR 0.88; 95% CI 0.74 to 1.04, moderate quality evidence). In patients on aclidinium, 122 people out of 1000 (95% CI 105 to 141) had exacerbations over 4 to 52 weeks, compared to 137 out of 1000 for patients on placebo (Table 1). In the subgroup analysis there was no significant difference between once daily (OR 0.93; 95% CI 0.73 to 1.20; 4 trials, 2201 participants) and twice daily aclidinium (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.66 to 1.05; 6 trials, 3423 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.51, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 2 Number of patients with exacerbations requiring steroids, antibiotics or both.

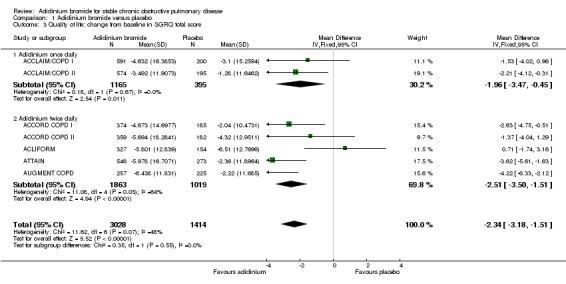

Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed by the SGRQ in seven studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD), either as the change from the baseline mean value or as the percentage of patients who achieved the minimal clinically important difference in SGRQ total score of ≥ four units reduction. Some of the data, in the format necessary for pooling, were kindly provided by the sponsors. Meta‐analysis of both measurements showed a statistically significant improvement with aclidinium bromide in comparison to placebo. Overall, aclidinium decreased the SGRQ total score by a mean difference of ‐2.34 units compared with placebo (95% CI ‐3.18 to ‐1.51; 7 trials, 4442 participants). A significant reduction in SGRQ total score was observed for both aclidinium once daily (MD ‐1.96; 95% CI ‐3.47 to ‐0.45; 2 trials, 1560 participants) and twice daily (MD ‐2.51; 95% CI ‐3.50 to ‐1.51; 5 trials, 2882 participants) with no significant difference between subgroups (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.55, Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 3 Quality of life: change from baseline in SGRQ total score.

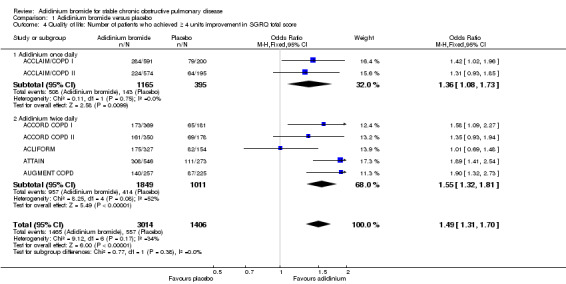

More patients on aclidinium reported a clinically significant improvement (a fall of at least four units in SGRQ total score) in quality of life than in the placebo group, which was of statistical significance (OR 1.49; 95% CI 1.31 to 1.70; 7 trials, 4420 participants; Analysis 1.4). A total of 494 per 1000 patients on aclidinium (95% CI 462 to 527) compared to 396 out of 1000 patients on placebo achieved a clinically important improvement in SGRQ score, the quality of evidence being rated as high (Table 1). In absolute terms, 98 more per 1000 (from 66 more to 131 more) patients on aclidinium experienced clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life than on placebo over 12 to 52 weeks. For every 10 people treated with aclidinium instead of placebo, one additional person was estimated to achieve this clinically important improvement in quality of life (NNT = 10; 95% CI 8 to 15). Both twice daily (OR 1.55; 95% CI 1.32 to 1.81; 5 trials, 2860 participants) and once daily aclidinium (OR 1.36; 95% CI 1.08 to 1.73; 2 trials, 1560 participants) demonstrated significant improvement with no statistical difference in the subgroup analysis (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.38; Figure 3).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 4 Quality of life: Number of patients who achieved ≥ 4 units improvement in SGRQ total score.

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, outcome: 1.4 Quality of life: Number of patients who achieved ≥ 4 units improvement in SGRQ total score.

Secondary outcomes

Lung function

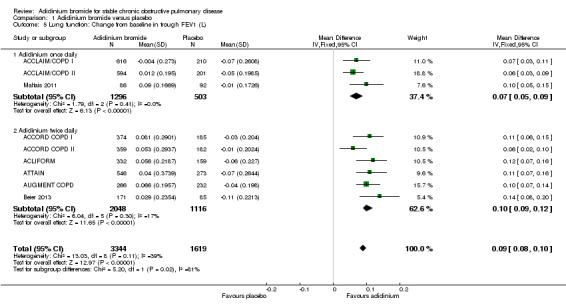

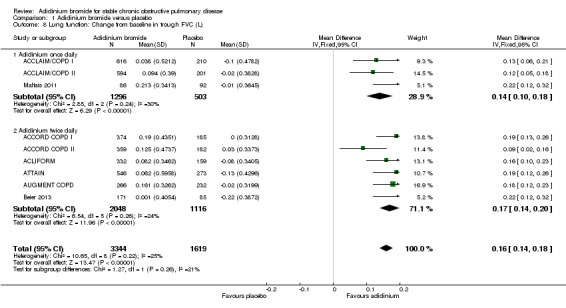

Nine trials studied changes from baseline in trough and peak FEV1, and trough and peak FVC (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Maltais 2011) and seven studies reported the change from baseline in normalised FEV1 area under the curve in the first 12 hours (FEV1 AUC0‐12) (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD). Most of the trials reported the data for these outcomes as the difference in aclidinium versus placebo values, but the required data for each intervention arm and placebo arm for our meta‐analysis were kindly provided by Almirall. These were pooled as the change from baseline to the end of the study.

The predose FEV1 for participants taking aclidinium was increased by 0.09 L (or 90 mL) at the end of the trials compared with participants using placebo inhalers (95% CI 0.08 to 0.10; 9 trials, 4963 participants). A greater improvement in the trough FEV1 was noted with twice daily dosing (MD 0.10; 95% CI 0.09 to 0.12; 6 trials, 3164 participants) compared to once daily (MD 0.07; 95% CI 0.05 to 0.09; 3 trials, 1799 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.02, Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 5 Lung function: Change from baseline in trough FEV1 (L).

The meta‐analysis for peak FEV1 change from baseline, using the random‐effects model due to significant heterogeneity (I2 = 56%), yielded an overall MD of 0.17 L (95% CI 0.15 to 0.20; 9 trials, 4962 participants). No difference in the pooled MD was observed between twice daily (MD 0.17; 95% CI 0.15 to 0.19; 6 trials, 3160 participants) and once daily aclidinium (MD 0.19; 95% CI 0.12 to 0.25; 3 trials, 1802 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.62, Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 6 Lung function: Change from baseline in peak FEV1 (L).

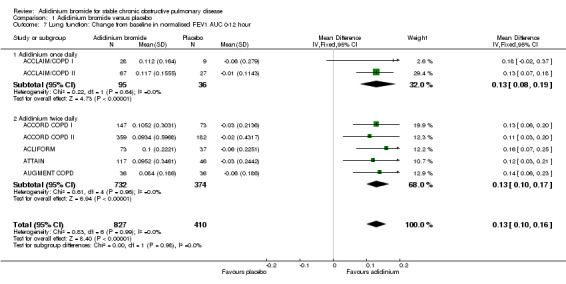

Aclidinium resulted in a statistically significant improvement of normalised FEV1 AUC0‐12 from baseline with a pooled MD of 0.13 L, or 130 mL, compared to placebo (95% CI 0.10 to 0.16; 7 trials, 1237 participants). The pooled MD for twice daily (MD 0.13; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.17; 5 trials, 1106 participants) and once daily aclidinium (MD 0.13; 95% CI 0.08 to 0.19; 2 trials, 131 participants) were similar (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 7 Lung function: Change from baseline in normalised FEV1 AUC 0‐12 hour.

The mean change in baseline trough FVC was 0.16 L greater with aclidinium than with placebo (95% CI 0.14 to 0.18; 9 trials, 4963 participants). There was no difference between twice daily (MD 0.17; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.20; 6 trials, 3164 participants) and once daily aclidinium (MD 0.14; 95% CI 0.10 to 0.18; 3 trials, 1799 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.26, Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 8 Lung function: Change from baseline in trough FVC (L).

The improvement in peak FVC from baseline was also significantly greater in patients on aclidinium compared to placebo with a pooled MD of 0.27 L (95% CI 0.23 to 0.31; 9 trials, 4962 participants) in the meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model as the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 56%). Subgroup analysis demonstrated no significant difference between twice daily (MD 0.25; 95% CI 0.22 to 0.28; 6 trials, 3160 participants) and once daily aclidinium (MD 0.33; 95% CI 0.23 to 0.42; 3 trials, 1802 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.13, Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 9 Lung function: Change from baseline in peak FVC (L).

Functional capacity

None of the individual studies measured functional capacity.

Hospital admissions due to exacerbations

The published reports of the included studies did not specifically mention hospital admissions due to either exacerbations or any cause. However, data for hospital admissions due to exacerbations, that is severe COPD exacerbations, were obtained for 10 studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011) from the study sponsors.

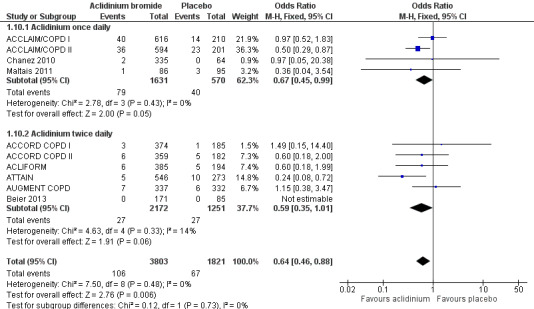

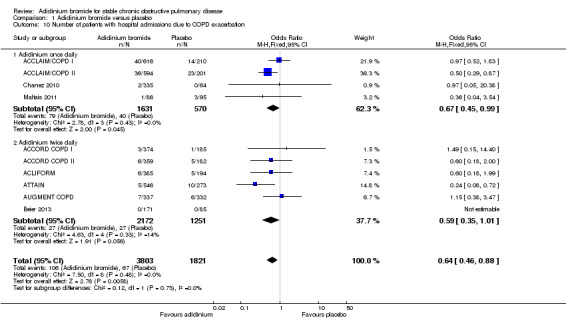

There were fewer patients on aclidinium who suffered one or more exacerbation(s) leading to hospitalisation than on placebo over 4 to 52 weeks (OR 0.64; 95% CI 0.46 to 0.88; 10 studies, 5624 participants) (Figure 4). Twenty four patients per 1000 (95% CI 17 to 33) on aclidinium suffered from at least one severe COPD exacerbation requiring hospital admission compared to 37 per 1000 on placebo, the quality of evidence being classified as high (Table 1). In absolute terms, aclidinium resulted in 13 fewer patients with exacerbation‐related hospitalisations per 1000 (4 to 20 fewer) than placebo. It was estimated that for every 77 patients treated with aclidinium instead of placebo, one additional person was free from a severe COPD exacerbation necessitating hospitalisation (NNT = 77; 95% CI 51 to 233). Subgroup analysis showed that the difference between twice daily (OR 0.59; 95% CI 0.35 to 1.01; 6 trials, 3423 participants) and once daily aclidinium (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.45 to 0.99; 4 trials, 2201 participants) was not statistically significant (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.73, Analysis 1.10).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, outcome: 1.10 Number of patients with hospital admissions due to COPD exacerbation.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 10 Number of patients with hospital admissions due to COPD exacerbation.

Improvement in symptoms

Changes in symptom of dyspnoea were assessed in eight studies using the transitional dyspnoea index (TDI) score (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Maltais 2011) and reported as either the change in mean value from baseline or as percentage of participants who achieved the minimal clinically important difference in TDI focal score of ≥ one unit increment.

Patients on aclidinium reported a MD of 0.84 units improvement in TDI compared with placebo (95% CI 0.50 to 1.18; 8 trials, 4490 participants) using a random‐effects model as the heterogeneity was high (I2 = 68%). This heterogeneity was caused by ACCORD COPD II in which the patients on aclidinium had a relatively lower baseline FEV1 with more severe disease (GOLD stage III) than in the placebo arm. Repeating the analysis with the exclusion of this particular study resulted in a MD of 0.95 units (95% CI 0.72 to 1.19) without heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Both once daily (MD 1.08; 95% CI 0.46 to 1.71; 3 trials, 1597 participants) and twice daily aclidinium (MD 0.72; 95% CI 0.33 to 1.11; 5 trials, 2893 participants) demonstrated an improvement in TDI focal score with no statistical difference in the subgroup analysis (test for subgroup differences: P = 0.33, Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 11 Improvement in symptoms: Change from baseline in TDI focal score.

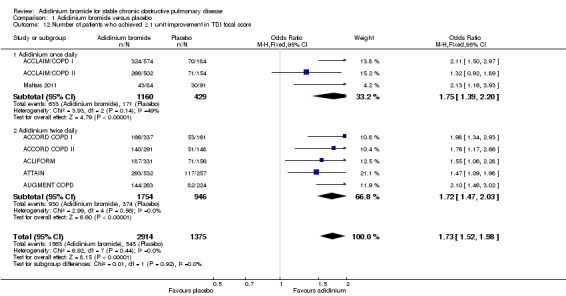

In terms of percentage of COPD patients achieving ≥ one unit improvement in TDI focal score for dyspnoea, more patients on aclidinium attained this minimal clinically important difference than for those on placebo (OR 1.73; 95% CI 1.52 to 1.98; 8 trials, 4289 participants; I2 = 0%). A similar improvement was noted for both once daily (OR 1.75; 95% CI 1.39 to 2.20; 3 trials, 1589 participants) and twice daily aclidinium (OR 1.72; 95% CI 1.47 to 2.03; 5 trials, 2700 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.92, Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 12 Number of patients who achieved ≥ 1 unit improvement in TDI focal score.

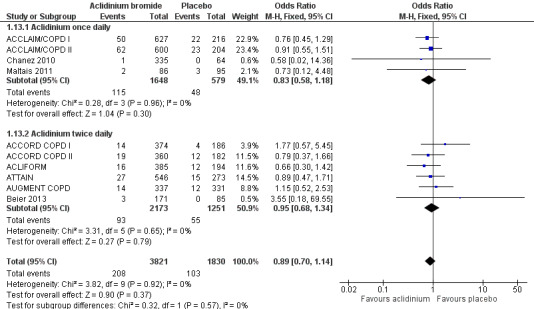

Non‐fatal serious adverse events

Ten studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011) reported this outcome with participants as the level of analysis (that is the number of people who had non‐fatal serious adverse events as opposed to the number of adverse events in total). When the findings of these studies were pooled, no difference was observed between aclidinium and placebo (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.14; 10 trials, 5651 participants) (Figure 5). Among 1000 patients, 50 receiving aclidinium (95% CI 40 to 64) and 56 on placebo developed non‐fatal serious adverse events, with moderate quality of evidence (Table 1). This result appeared to be independent of dosing (twice daily OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.34; 6 trials, 3424 participants; once daily OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.58 to 1.18; 4 trials, 2227 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.57, Analysis 1.13).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, outcome: 1.13 Non‐fatal serious adverse events.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 13 Non‐fatal serious adverse events.

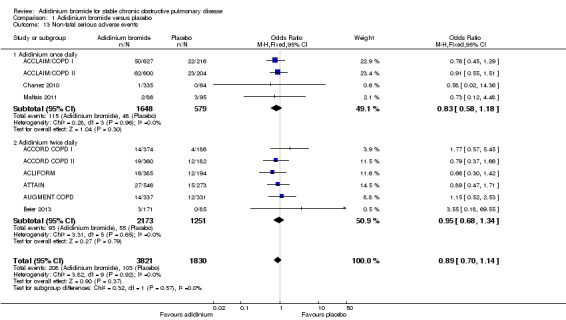

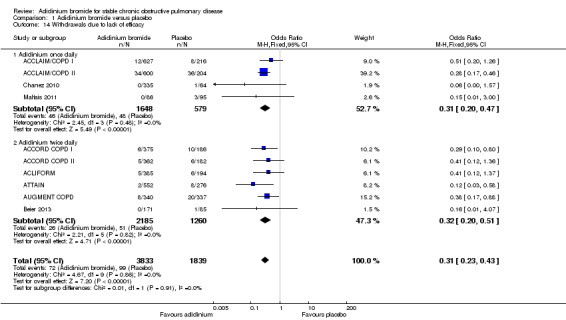

Withdrawals

Withdrawals due to either lack of efficacy or adverse events were provided in 10 studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011; NCT01572792).

There was a statistically and clinically significant reduction in withdrawals due to lack of efficacy with aclidinium compared to placebo (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.23 to 0.43; 10 trials, 5672 participants). The effect estimates were similar for twice daily (OR 0.32; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.51; 6 trials, 3445 participants) and once daily aclidinium (OR 0.31; 95% CI 0.20 to 0.47; 4 trials, 2227 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.91, Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 14 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

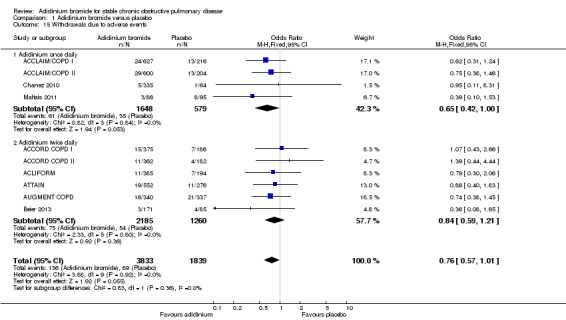

Overall, aclidinium resulted in a non‐significant reduction in withdrawals due to adverse events compared with placebo (OR 0.76; 95% CI 0.57 to 1.01; 10 trials, 5672 participants). No significant difference was observed for once daily dosing (OR 0.65; 95% CI 0.42 to 1.00; 4 trials, 2227 participants) and twice daily dosage regimens (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.59 to 1.21; 6 trials, 3445 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.36, Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Aclidinium bromide versus placebo, Outcome 15 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

2. Aclidinum bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist

Primary outcomes

There were no deaths reported for both the aclidinium and tiotropium arms in a total of 329 patients in Beier 2013 (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 1 Total number of deaths.

Two studies assessed exacerbations requiring a short course of oral steroids or antibiotics, or both, in 729 participants (Beier 2013 ; Chanez 2010). Aclidinium was associated with a higher number of exacerbations compared to tiotropium but this was not statistically significant (OR 2.64; 95% CI 0.31 to 22.18) (Analysis 2.2). There were no patients with moderate exacerbations in the tiotropium arm compared to five of 506 participants in the aclidinium arm. However, the quality of evidence was very low because of the high risk of bias in Chanez 2010, which was open label for the tiotropium arm and had very serious imprecision of the results (Table 2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 2 Number of patients with exacerbations requiring steroids, antibiotics or both.

None of the studies measured quality of life for aclidinium and tiotropium.

Secondary outcomes

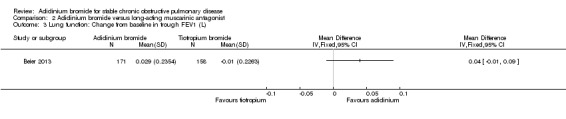

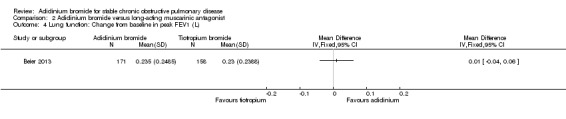

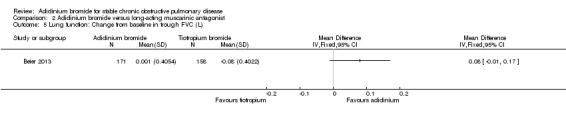

Only one trial provided data for aclidinium and tiotropium on lung function (Beier 2013). Aclidinium was associated with a greater improvement in trough FEV1 (MD 0.04; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.09; 1 trial, 329 participants) (Analysis 2.3), peak FEV1 (MD 0.01; 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.06; 1 trial, 329 participants) (Analysis 2.4), trough FVC (MD 0.08; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.17; 1 trial, 329 participants) (Analysis 2.5) and peak FVC (MD 0.04; 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.13; 1 trial, 329 participants) (Analysis 2.6) than tiotropium, however none were statistically significant.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 3 Lung function: Change from baseline in trough FEV1 (L).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 4 Lung function: Change from baseline in peak FEV1 (L).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 5 Lung function: Change from baseline in trough FVC (L).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 6 Lung function: Change from baseline in peak FVC (L).

Functional capacity was not assessed in the two studies included in this comparison.

Aclidinium reduced the number of patients with hospitalisations due to COPD exacerbations compared to tiotropium but the difference was not statistically significant (OR 0.54; 95% CI 0.07 to 4.11; 2 trials, 729 participants) (Analysis 2.7). Two patients per 1000 (95% CI 0 to 18) on aclidinium versus four patients per 1000 on tiotropium were admitted to hospital for severe COPD exacerbations, but this was very low level evidence (Table 2). The wide CI included the possibility of no difference.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 7 Number of patients with hospital admissions due to COPD exacerbation.

Data from the two trials (Beier 2013 ; Chanez 2010) were combined for non‐fatal serious adverse events. Aclidinium demonstrated a non‐significant reduction in non‐fatal serious adverse events compared with tiotropium (OR 0.67; 95% CI 0.17 to 2.65; 2 trials, 729 participants) (Analysis 2.8). In a total of 1000 patients, 12 on aclidinium (95% CI 3 to 46) and 18 on tiotropium experienced non‐fatal serious adverse events over a period of four to six weeks, with a very low quality of evidence as the CIs were wide.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 8 Non‐fatal serious adverse events.

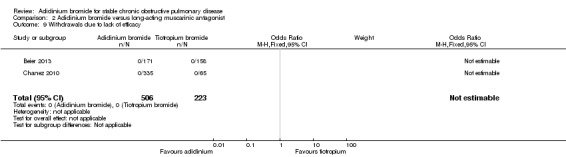

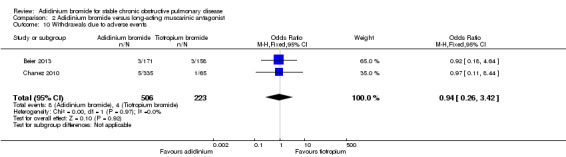

Both Beier 2013 and Chanez 2010 reported withdrawals due to lack of efficacy or adverse events. There were no withdrawals due to lack of efficacy for both aclidinium and tiotropium in these two studies (Analysis 2.9). No significant difference existed between aclidinium and tiotropium for withdrawals due to adverse events (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.26 to 3.42; 2 trials, 729 participants) (Analysis 2.10).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 9 Withdrawals due to lack of efficacy.

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Aclidinium bromide versus long‐acting muscarinic antagonist, Outcome 10 Withdrawals due to adverse events.

3. Aclidinum bromide versus long‐acting beta2‐agonist

Inadequate and inaccurate data limited this comparison as formoterol was given via the Genuair inhaler in the trials, which was not an approved inhaler for formoterol (ACLIFORM; AUGMENT COPD; NCT01572792; Sliwinski 2010).

4. Adverse events

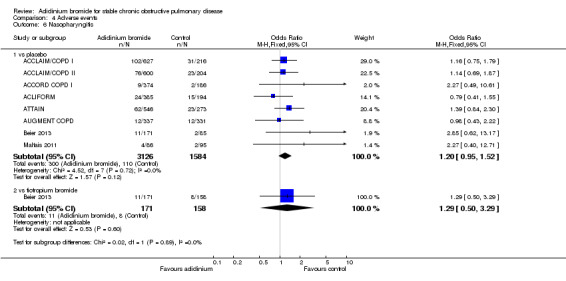

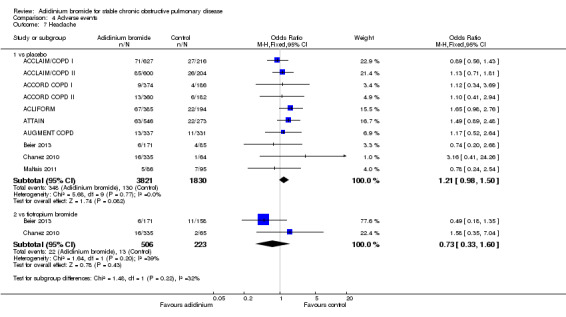

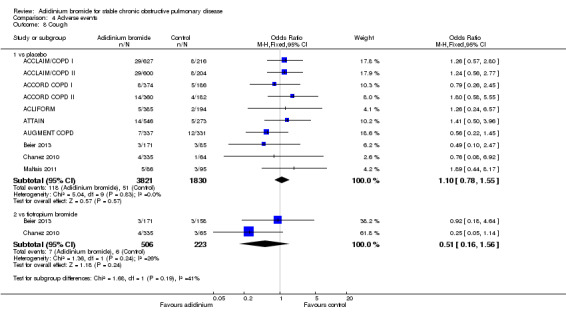

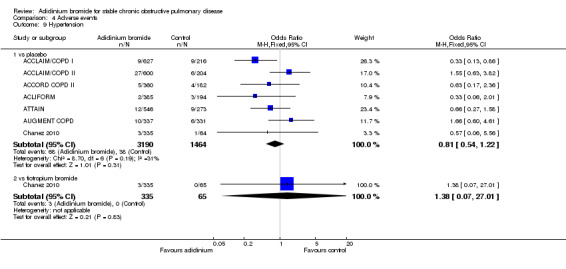

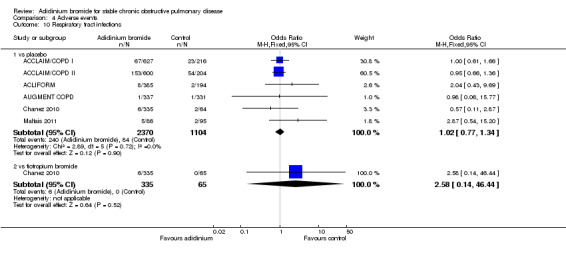

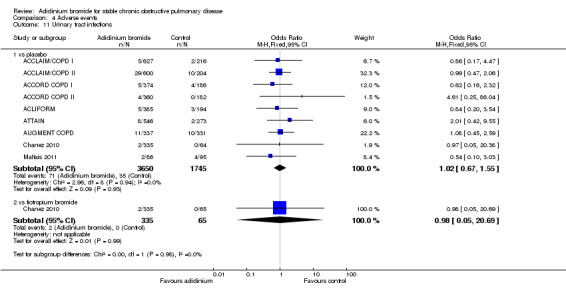

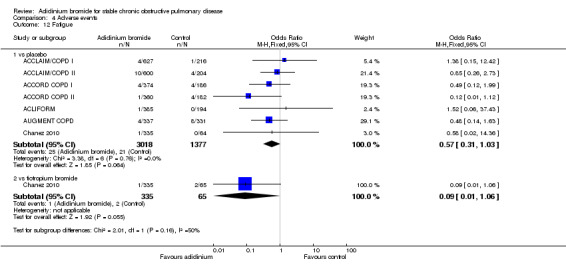

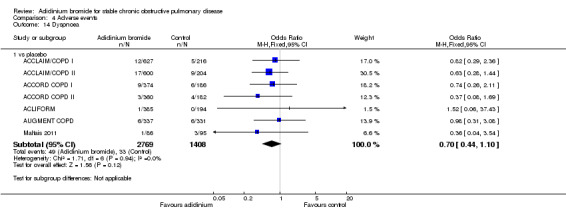

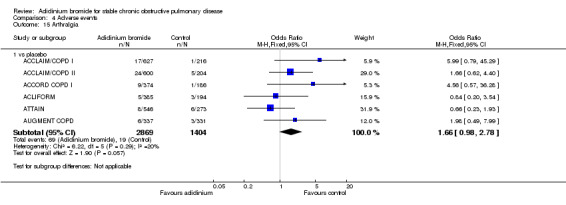

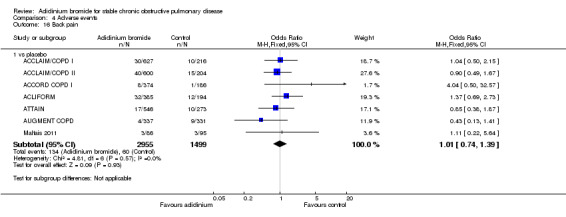

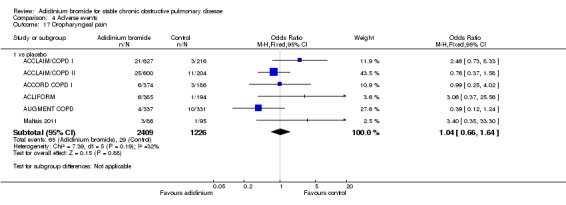

Adverse events with aclidinium were reported in a total of 10 studies (ACCLAIM/COPD I; ACCLAIM/COPD II; ACCORD COPD I; ACCORD COPD II; ACLIFORM; ATTAIN; AUGMENT COPD; Beier 2013; Chanez 2010; Maltais 2011). We have presented the adverse event data from both comparisons with placebo and tiotropium in section 4 of Data and analyses.

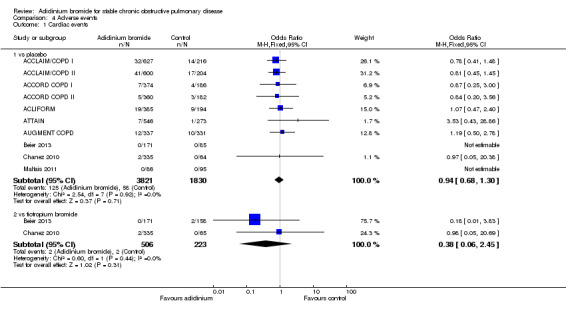

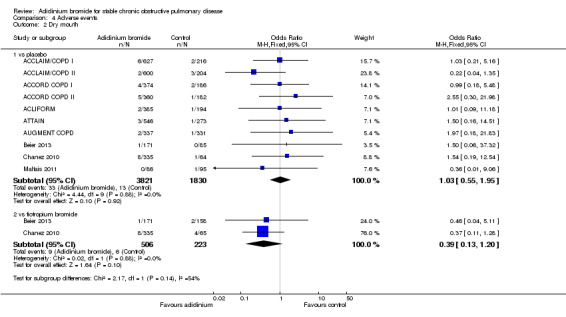

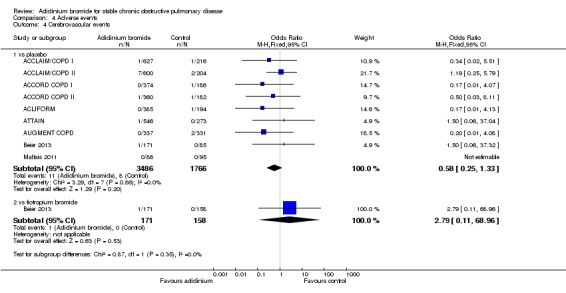

A lower incidence of cardiac events (Analysis 4.1) was more prominent with aclidinium compared to tiotropium and placebo, but both were statistically non‐significant. There was no significant difference between aclidinium and placebo or tiotropium for the anticholinergic side effect of dry mouth (Analysis 4.2). Constipation was non‐significantly more frequent with aclidinium compared to both placebo and tiotropium (Analysis 4.3). Aclidinium non‐significantly decreased cerebrovascular events (Analysis 4.4) compared to placebo (OR 0.58; 95% CI 0.25 to 1.33; 9 trials, 5252 participants). However, in Beier 2013 cerebrovascular events were more frequent with aclidinium compared to tiotropium but the CIs were very wide and the difference was not statistically significant (OR 2.79; 95% CI 0.11 to 68.96; 1 trial, 329 participants).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adverse events, Outcome 1 Cardiac events.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adverse events, Outcome 2 Dry mouth.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adverse events, Outcome 3 Constipation.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adverse events, Outcome 4 Cerebrovascular events.

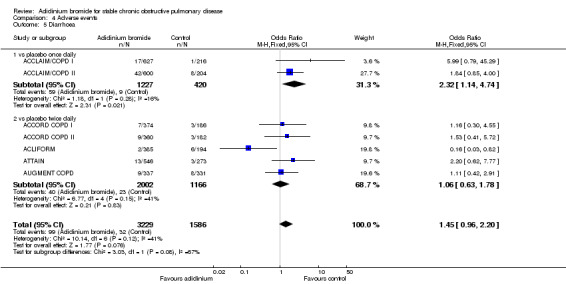

Diarrhoea was found to be significantly increased with aclidinium (once daily therapy) compared to placebo (OR 2.32; 95% CI 1.14 to 4.74; 2 trials, 1647 participants). However, no statistical difference was observed between once daily and twice daily aclidinium (OR 1.06; 95% CI 0.63 to 1.78; 5 trials, 3168 participants; test for subgroup differences: P = 0.08, Analysis 4.5).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Adverse events, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.