Abstract

The response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria have been the gold standard for monitoring treatment response in glioblastoma (GBM) and differentiating tumor progression from pseudoprogression. While the RANO criteria have played a key role in detecting early tumor progression, their ability to identify pseudoprogression is limited by post-treatment damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which often leads to contrast enhancement on MRI and correlates poorly to tumor status. Amino acid positron emission tomography (AA PET) is a rapidly growing imaging modality in neuro-oncology. While contrast-enhanced MRI relies on leaky vascularity or a compromised BBB for delivery of contrast agents, amino acid tracers can cross the BBB, making AA PET particularly well-suited for monitoring treatment response and diagnosing pseudoprogression. The authors performed a systematic review of PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase through December 2021 with the search terms “temozolomide” OR “Temodar,” “glioma” OR “glioblastoma,” “PET,” and “amino acid.” There were 19 studies meeting inclusion criteria. Thirteen studies utilized [18F]FET, five utilized [11C]MET, and one utilized both. All studies used static AA PET parameters to evaluate TMZ treatment in glioma patients, with nine using dynamic tracer parameters in addition. Throughout these studies, AA PET demonstrated utility in TMZ treatment monitoring and predicting patient survival.

Keywords: amino acid PET, glioblastoma, glioma, pseudoprogression, treatment response, temozolomide

Background

Temozolomide(TMZ) is a second-generation oral alkylating agent that is considered a relatively effective treatment for gliomas. The first-line treatment for newly diagnosed glioblastoma (GBM) is surgical resection when feasible. Following resection, the standard treatment is six weeks of radiochemotherapy using concomitant daily TMZ (RCT-TMZ) followed by adjuvant TMZ for six cycles, as established by the Stupp Protocol.1 Adjuvant TMZ may also be administered beyond six cycles, as some studies have shown survival benefits with extended TMZ.2 Despite the established treatment, the prognosis of patients with GBM and other high-grade gliomas (HGG) is poor with a high tumor recurrence rate.3 Recurrent HGG requires prompt treatment with further resection, RCT, or other chemotherapy agents. The treatment for low-grade glioma (LGG) is more controversial, since no standard has been established, although chemotherapy with TMZ alone or in combination with other agents is often used. Since TMZ carries hematologic toxicities and its efficacy is often uncertain in LGG, some patients may benefit from alternative treatments if TMZ is not effective.4 Therefore, for both HGG and LGG, a method to accurately assess the efficacy of TMZ therapy, especially at an early stage, is needed to promptly revise the treatment plan in the event of TMZ resistance or to avoid overtreatment in the absence of tumor progression.

Currently, the primary treatment monitoring method is MRI before and after treatment with periodic follow-up imaging. Established in 2010, the response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria, which categorizes outcomes from complete and partial response to disease progression, have been widely utilized for assessing treatment response in HGG and LGG.5 While the RANO criteria take into account clinical factors, they rely heavily on the appearance of contrast-enhancing lesions on MRI, which is affected by post-treatment damage to the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and often correlates poorly to tumor status.6 Furthermore, the phenomenon of pseudoprogression is observed in approximately 36% of HGG patients treated with standard RCT-TMZ and cannot be effectively identified on MRI.7 Pseudoprogression may be associated with the radiosensitizing effect of TMZ, and is, therefore, most commonly observed in patients treated with RCT-TMZ.8,9 Continuation of TMZ in patients with pseudoprogression yields improved survival; therefore, it is important to promptly distinguish pseudoprogression from true progression to avoid erroneously terminating an effective therapy.9

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a rapidly growing imaging modality in oncology. The most widely used radiotracer for PET is 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose ([18F]FDG), although its usage in neurooncology is limited, as [18F]FDG is nonspecific to tumor tissues due to its high background uptake in the brain.10 In the recent decades, however, PET utilizing radiolabeled amino acids (AA PET) has gained attention for its potential in assessing treatment response in gliomas, in addition to diagnostic and prognostic values.11,12 The ability of AA tracers to cross the BBB is a crucial advantage that overcomes the limitations of contrast-enhanced MRI, which relies on leaky vascularity or compromised BBB for delivery of contrast agents.13 Furthermore, unlike [18F]FDG, AA radiotracer uptake is specific to tumor tissues due to the considerable difference in AA metabolism, yielding minimal background activity. Several AA radiotracers have shown potential in neuro-oncologic imaging, including O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine ([18F]FET), [11C]methyl-L-methionine ([11C]MET), and 3,4-dihydroxy-6-[18F]fluoro-L-phenylalanine ([18F]FDOPA).

Among these AA tracers, [18F]FET and [11C]MET are the most widely studied and both appear to be reliable radiotracers with no major uptake differences in glioma patients.14,15 Although some reported that the uptake of [18F]FET in inflammatory tissue is lower than that of [11C]MET, and thus [18F]FET may be more specific to tumor, most do not consider the difference significant.14,15 The major difference between these two tracers is that the half-life of [11C]MET is 20 minutes, requiring an onsite cyclotron, while [18F]FET has a longer half-life of 110 minutes, allowing broader usage.14 Although this review does not discuss studies that utilized [18F]FDOPA in detail, this AA tracer has also been studied for the diagnosis and prognosis of recurrent glioma. [18F]FDOPA is a substrate of aromatic amino acid decarboxylase, which is highly expressed in dopaminergic neurons. As a result, the high physiologic [18F]FDOPA uptake in the basal ganglia presents a limitation, which has been shown to interfere with delineating tumors in its vicinity.16 This review aims to summarize and evaluate the role of AA PET imaging in assessing treatment response to TMZ therapies in HGG and LGG.

Literature Search

Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

A literature review was conducted in the PubMed, MEDLINE, and Embase databases on June 22, 2020, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRIMSA) guidelines.17 A combination of the search terms “temozolomide” OR “Temodar,” “glioma” OR “glioblastoma,” “PET,” and “amino acid” were used along with the filters “humans” and “English.” No time limit was placed on the search.

The screening of abstracts and full-text articles was performed independently by two reviewers (K.Y.P. and A.M.W.). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion to achieve a consensus decision or, if consensus could not be reached, by referral to a third reviewer (C.A.G). To be included, studies must: (1) involve patients with glioma who underwent some form of TMZ treatment, (2) perform AA PET on patients during and/or after TMZ treatment, (3) utilize AA PET data to assess treatment response to TMZ, and (4) report clinical or histological outcomes of the patients. The bibliographies of relevant reviews and original studies were examined for any relevant papers that were not included in the database search results.

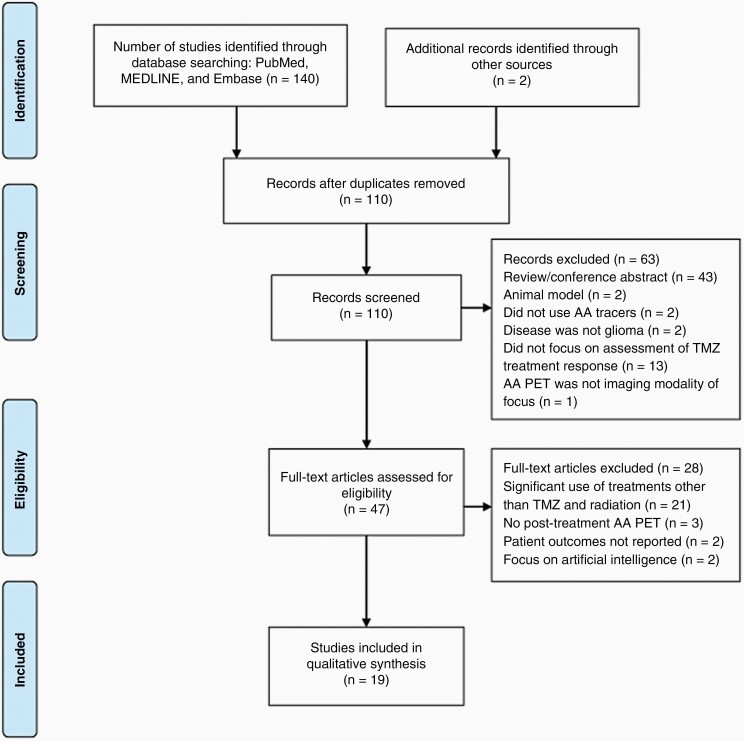

A workflow diagram of the literature selection process is shown in Figure 1. The database search yielded 110 results after deduplication, of which 63 were excluded after the initial title and abstract screening. Reasons for exclusion during the title and abstract screening were: not using amino acid radiotracers for PET (n = 2), not including human glioma patients (n = 2), disease not categorized as glioma (n = 2), not focusing on assessment of treatment response to TMZ (n = 13), not focusing on AA PET as the imaging modality of interest (n = 1), review papers (n = 24), and conference abstracts (n = 19). Two additional papers that fit all of the eligibility criteria but were not included in the original database search results were identified in the bibliographies of relevant publications.18,19 A total of 47 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 19 were ultimately selected for detailed discussion. During the full-text screening, studies were excluded if the patients received AA PET only prior to TMZ treatment and no follow-up (n = 21), if the patients received other significant treatments along with TMZ (note that RT was an exception to this criterion) (n = 3), if patient outcome was not reported (n = 2), and if the primary focus is artificial intelligence (n = 2).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for AA PET studies involving temozolomide.

Review of Studies

The imaging parameters and main findings from each qualifying study are listed in Table 1. Among the 19 studies selected, 13 utilized [18F]FET, five utilized [11C]MET, and one used both. The sample size of these studies ranged from 1 to 79. Fourteen studies focused on HGG, two focused on LGG, and three reported a combination of HGG and LGG patients. In six studies, AA PET was performed on patients before and after the initiation of RCT with concurrent TMZ, often with follow-up AA PET extending into the adjuvant TMZ period.19–24 In five studies, AA PET imaging was only available after completion of RCT.18,25–28 Four studies performed AA PET during or after the completion of adjuvant TMZ, of which two also performed AA PET prior to starting adjuvant TMZ.29–32 The remaining four papers, three of which focused on LGG, reported AA PET imaging before and periodically throughout the course of TMZ chemotherapy.33–36

Table 1.

Overview of Included AA PET Studies

| Study | Tumor Grade (Number of Patients) | Tracer & Study type | AA PET Imaging Timing | Outcome Measurement | Assessment | Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessing Response to RCT-TMZ | ||||||

| Piroth et al., 2011 | GBM (22) | Static [18F]FET Prospective |

T0: pretreatment (11–20 days after surgical resection) T1: 7–10 days after completing RCT-TMZ T2: 6–8 weeks later |

OS DFS |

TBRmean TBRmax Change in TBR Threshold: 1.6 |

[18F]FET-PET is a sensitive tool to predict early treatment response in GBM patients treated with RCT-TMZ. - Defined early responders as those who had at least 10% decrease in TBRmax 7-10 days post-treatment. - Identified 16 early responders and 6 nonresponders. Early PET responders had significantly longer DFS (10.3 vs. 5.8 months) and OS (“not reached” vs. 9.3 months) than the nonresponders. |

| Galldiks et al., 2012 | GBM (25) | Static [18F]FET Prospective |

T0: pretreatment (11–20 days after surgical resection) T1: 7–10 days after completing RCT-TMZ T2: 6–8 weeks later |

OS PFS |

TBRmean TBRmax Change in TBR Tvol Threshold: 1.6 |

Static [18F]FET-PET parameters, especially change in TBR, can detect treatment response to RCT-TMZ in GBM patients as early as one week post-treatment. - A decrease of 10% or more in TBRmax and TBRmean between T1 and T2 (early responders) correlated with a significantly longer median PFS and OS (also see study above). - Six to eight weeks later, the predictive value of TBR was less significant, but found an association between a decrease of Tvoland PFS. - Change in MRI tumor volume did not yield significant correlation to survival. |

| Piroth et al., 2013 | GBM (25) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Prospective |

T0: pretreatment (11–20 days after surgical resection) T1: 7–10 days after completing RCT-TMZ T2: 6–8 weeks later |

OS PFS |

TBRmean TBRmax Change in TBR Threshold: 1.6 TTP Slope of TAC SoD |

Dynamic [18F]FET-PET does not add significant prognostic value in detecting treatment response to RCT-TMZ in GBM. - Confirmed the high predictive value of change in TBR pre- and post-treatment for patient outcome, as described in the above two studies. - Could not confirm the prognostic value of Tvol 1.6at 6–8 weeks post-treatment that was described in the above study. - Changes in TTP, SoD, and slope of TAC pre- and post-treatment did not correlate with outcome. |

| Santoni et al., 2014 | GBM (22) HGG- AA (15) LGG (16) |

Static [11C]MET Retrospective |

T0: pretreatment (within 1 month from surgical resection) Follow-up: periodic imaging until progression |

OS | SUVmax Mean uptake index Relative uptake index |

Complementary [11C]MET-PET in addition to MRI/CT may be helpful in postoperative and successive tumor assessment in both HGG and LGG patients. - The combination of [11C]MET-PET with MRI/CT distinguished treatment-related changes from residual disease with 93.97% sensitivity and 95.18% specificity in AA, and with 96.92% sensitivity and 100% specificity in GBM patients during their RCT-TMZ and adjuvant TMZ treatment. - [11C]MET-PET allowed early detection of malignant progression from low grade to anaplastic astrocytoma with high sensitivity (91.56%) and specificity (95.18%). - Mean uptake index on MET-PET was significantly correlated with histologic grading, with GBM demonstrating the highest mean uptake index. |

| Suchorska et al., 2015 | GBM (79) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Prospective |

T0: pretreatment T1: postoperatively (Cohort A only) T2: 4–6 weeks following treatment (n = 64) T3: after 3 cycles of adjuvant TMZ (n = 31) |

OS PFS |

SUV LBRmax BTV Threshold: 1.8 TAC pattern |

Dynamic [18F]FET-PET TAC pattern and pretreatment BTVsignificantly predicted prognosis in GBM. - BTV defined by FET-PET before RCT-TMZ was the strongest predictor of PFS and OS, independent of MGMT methylation status. - The following TAC patterns were associated with longer PFS (in descending order): 1. Increasing TAC 2. Change from increasing to decreasing TAC after treatment 3. Change from decreasing to increasing TAC after treatment 4. Decreasing TAC - Both BTV and LBRmaxdecreased after completion of RCT-TMZ, although no further decrease was seen after three cycles of adjuvant TMZ. - Did not find reduction in BTV or LBRmax to correlate with PFS or OS. |

| Lohmann et al., 2018 | GBM (1) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Case Report |

4 weeks after completion of RCT-TMZ | Progression on histology | TBR Threshold: 1.6 TAC pattern |

Increased [18F]FET TBR and dynamic TAC pattern correlated well with tumor burden on histologic studies, suggesting [18F]FET-PET may accurately identify progressive tumor tissue. - Areas of histologically confirmed tumor showed TAC pattern that peaked early and then demonstrated a constant decrease in uptake,which is typical of malignant tissue. - Areas of histologically confirmed gliosis showeda constant rising TAC pattern that was consistent with normal brain. |

| Kawasaki et al., 2019 | GBM (30) | Static [11C]MET Retrospective |

T0: pretreatment(after surgical resection) Follow-up: every 3 months after completing RCT-TMZ |

OS | L/N ratio Variation rate of L/N ratio Thresholds: 2.0 and 1.3 |

A decrease in [11C]MET L/N ratio at 3 months after RCT-TMZ was significantly related to the survival time for patients with GBM. - At 3 months post-treatment, a variation rate of –0.366 in the L/N ratio differentiated patients with > 23 months versus ≤ 23 months OS. - L/N ratio decreased for 9 months after RCT-TMZ, while MRI contrast enhancement volumes decreased for 3 months, and then increased for up to 9 months. This illustrated a discrepancy in longitudinal changes between [11C]MET-PET and contrast-enhanced MRI. |

| Assessing Response to Adjuvant TMZ | ||||||

| Galldiks et al., 2010 | GBM (2) | Static [11C]MET Case Series |

Variable, based on radiological changes and concern for recurrence | Treatment Response | Uptake ratio Threshold: 1.3 |

Utilized [11C]MET-PET to monitoradjuvantTMZ-treatment response and detected recurrence earlier than MRI or clinical symptoms. - Patient 1 underwent [11C]MET-PET imaging before beginning adjuvant TMZ (after second resection), during adjuvant TMZ, 6 months after adjuvant TMZ discontinuation, and during the 20th cycle of adjuvant TMZ. - Patient 2 underwent [11C]MET-PET imaging after resection and RCT-TMZ, during adjuvant TMZ, 7 months after TMZ dose reduction, and 3 months after TMZ dose escalation (in response to suspected recurrence on [11C]MET-PET). |

| Hirono et al., 2019 | GBM (44) | Static [11C]MET Retrospective |

After extended (12 or more cycles) adjuvant TMZ | Recurrence PFS |

Tmax/Nave Threshold: 2.0 |

Tumor recurrence rate increased in a stepwise manner according to [11C]MET uptake as GBM patients with high uptake showed more frequent tumor progression than those with low uptake. Compared to MRI, [11C]MET-PET demonstrated improved ability to monitor and predict tumor progression. - A TBRmax threshold of 2.0 demonstrated 77.8% sensitivity and 80.8% specificity for predicting tumor progression within one year. - Subgroups with high uptake, even with continuation of TMZ, showed more frequent tumor progression than patients with low uptake. - Low MET uptake was associated with a 93% lower risk for recurrence within one year after PET. |

| Werner et al., 2019* | HGG (48) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Retrospective |

Mean time between progression on MRI and [18F]FET-PET: 16 ±15 days Mean time from last treatment to suspected progression: 30±38 weeks |

Progression Treatment Response OS |

TBRmean TBRmax Threshold: 1.6 Slope of TAC TTP |

Static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET parameters may be useful in differentiating progression from pseudoprogression after suspected progression on MRI. - Static parameters TBRmax or TBRmean < 1.95 were most accurate (83%) in diagnosing tumor progression alone(sensitivity, 100%; specificity, 79%). - TBRmax or TBRmean < 1.95 also significantly differentiated OS in patients, with those below the 1.95 cutoff demonstrating greater OS. - The most accurate model (93%) for diagnosing tumor progression involved the static parameters TBRmax or TBRmean < 1.95 and the dynamic parameter slope of TAC > 0.32 SUV/h (sensitivity, 78%; specificity 97%). - The DWI parameter ADC demonstrated an accuracy of 69% (sensitivity, 60%; specificity,71%) but did increase the accuracy of the static parameter model to 89%(sensitivity, 67%; specificity, 94%). |

| Ceccon et al., 2021 | HGG (41, 90% of which had GBM) | Static [18F]FET Prospective |

T0: after completion of RCT-TMZ, within 7 days before initiating adjuvant TMZ T1: after two cycles of adjuvant TMZ |

PFS OS MGMT promoter methylation |

TBRmean TBRmax Change in TBR Tvol Threshold: 1.6 |

Changes in [18F]FET-PET parameters appear to be effective for identifying responders to adjuvant TMZ early during treatment in patients with newly diagnosed malignant glioma. - After two cycles of adjuvant TMZ, a reduction in [18F]FET Tvol and TBRmax predicted a significantly longer OS and PFS, independent of MGMT promoter methylation status and other prognostic factors such as age, whereas responders identified byRANO criteria using contrast-enhancedMRI did not correlate with clinical outcome. - At baseline before initiating adjuvant TMZ, absolute Tvol of ≤ 28.2 mL or a TBRmax ≤ 2.0 predicted a near doubled PFS; absolute baseline Tvol of ≤ 13.8 mL also predicted a significantly longer OS. |

| Assessing Response to TMZ Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Galldiks et al., 2006 | HGG (14) LGG (1) |

Static [11C]MET Prospective |

T0: pretreatment T1: after 3rd cycle (n = 15) T2: after 6th cycle (n = 12) |

OS Time to progression |

TBRmax (uptake index) Change in TBRmax Threshold: 1.5 |

Changes in [11C]MET uptake correlated significantly to long-term outcome, suggesting that [11C]MET-PET is capable of monitoring metabolically active tumor when contrast enhancement is absent. - Patients with an uptake index that declined had significantly longer time to progression than patients with an uptake index that increased. - Contrast enhancement was not significantly correlated to [11C]MET uptake, supporting the ability of [11C]MET to detect tumor progression earlier than MRI. |

| Wyss et al., 2009 | LGG (11) | Static [18F]FET Prospective |

At 6-month intervals after 6 cycles of chemotherapy | PFS Time to maximal volume reduction |

T:CBL ratio Threshold: 1.1 |

[18F]FET-PET may be useful for monitoring TMZ-treatment response in patients with LGG. - Time to maximal volume reduction was seen on [18F]FET-PET earlier (8.0 ± 4.4 months) than on MRI (15.0 ± 3.0 months). - Patients who demonstrated response on both [18F]FET-PET and MRI had the longest PFS. |

| Roelcke et al., 2016 | LGG (33) | Static [18F]FET and [11C]MET Retrospective |

T0: 1 month pretreatment T1: between 2–6 months thereafter |

Response Seizure Control PFS OS |

Mean T:CBL ratio Peak uptake ratio Tvol Threshold: 1.1 |

Seizure control was correlated with reduction of metabolically active tumor volumes on [18F]FET and [11C]MET-PET, following TMZ in LGG. - Seizure control was not correlated with changes in uptake ratios or T2-weighted MRI volume. - Decrease in active tumor volume by at least 80.5% significantly predicted PFS of 60 months or more. |

| Suchorska et al., 2018* | HGG-Grade III (17) LGG-Grade II (44) |

Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Retrospective |

T0: pretreatment T1: 6 months following initiation |

Response Seizure Control PCS TTF |

TBRmax TBRmean BTV Threshold: 1.8 TAC patterns |

Patients with grade II and III glioma and no enhancement on MRI may benefit from [18F]FET-PET to monitor response to TMZ. - Patients who showed response to TMZ on [18F]FET-PET had significantly longer TTF and PCS than patients with stable or progressive disease. - Volume changes on MRI did not differ significantly between patients with responsive, stable, or progressive disease. |

| Diagnosing Pseudoprogression | ||||||

| Niyazi et al., 2012 | GBM (79) | Static [18F]FET Retrospective |

Four to six weeks following completion of RCT-TMZ and then every 3 months afterwards | OS PFS MGMT promoter methylation |

SUVmax/BG Recurrence pattern Threshold: 1.8 |

Patients with an ex-field or marginal recurrence on [18F]FET had significantly longer PFS compared to patients with an in-fieldrecurrence. - Recurrence pattern categorized as follows: 1. In-Field = 80% recurrence in field of RT 2. Marginal = 20-80% recurrence in field 3. Ex-Field = < 20% recurrence outside the field - Patients with MGMT promoter methylation had significantly longer 1- and 2-year OS (93.1% and 78.1%) than patients without (64.9% and 7.3%). - Patients with MGMT promoter methylation had significantly longer median PFS (642 days) than patients without (231 days). - Patients with recurrence and MGMT promoter methylation were more likely to demonstrate an ex-field recurrence pattern (6/17, 35.3%) than patients with recurrence and no MGMT promoter methylation (2/18, 11.1%). |

| Galldiks et al., 2015 | GBM (22) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Retrospective |

Within 12 weeks of completing RCT-TMZ Median time between progression on MRI and [18F]FET-PET:7 days Median time between last treatment and suspected recurrence: 7 weeks |

PsP Progression OS MGMT promoter methylation |

TBRmax TBRmean Threshold: 1.6 TTP TAC |

Patients with PsP had significantly lower TBRmax and TBRmean on [18F]FET-PETand longer TTPcompared to patients with early progression. - ROC analysis demonstrated that a TBRmax < 2.3 significantly differentiated PsP from early progression, with an accuracy of 96%. - Patients with PsP were significantly more likely to demonstrate positive MGMT promoter methylation status (6/11, 54.5%), compared to those with early progression (2/11, 18.2%). - Patients with early progression were most likely to demonstrate a TAC pattern of II or III, and no patients with PsP demonstrated a type III TAC pattern. |

| Kebir et al., 2016* | GBM (22) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Retrospective |

More than 12 weeks after completion of RCT-TMZ | Late PsP Progression PFS OS MGMT promoter methylation |

TBRmax TBRmean Threshold: 1.6 TTP TAC |

Patients with late PsP had significantly lower TBRmax and TBRmean on [18F]FET-PET and longer TTP compared to patients with true progression, indicating [18F]FET-PET may be useful in diagnosing late PsP. - ROC analysis demonstrated that a TBRmax < 1.9 differentiated late PsP from true progression, with an accuracy of 85%. - The majority of patients with late PsP (6/7, 86%) had MGMT methylation, which was in line with previous studies on methylation status in PsP. - No patients with late PsP demonstrated a TAC pattern of II or III. |

| Werner et al. 2021* | GBM (23) | Static and Dynamic [18F]FET Retrospective |

Less than 26 days following discovery of suspicious MRI lesion during TMZ-lomustine treatment | PsP Progression MGMT promoter methylation (all patients had positive methylation) |

TBRmax TBRmean Threshold: 1.6 TTP Slope of TAC |

In 23 patients with newly diagnosed GBM (all with methylated MGMT promoter) treated with TMZ-lomustine RCT, combined static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET appeared to be an accurate diagnostic tool in identifying PsP that was inconclusive on contrast-enhanced MRI. - In 11 out of 23 patients, PsP was diagnosed within 5–25 weeks after completion of TMZ-lomustine RCT. The rest 12 patients had confirmed tumor progression. - TBRmean (1.9 ± 0.2 vs. 2.1 ± 0.2) and TBRmax (2.8 ± 0.6 vs. 3.2 ± 0.5) were significantly lower in PsP compared to true progression. Dynamic TTP was significantly higher in PsP than true progression (36.6 ± 8.3 vs. 24.8 ± 9.4 minutes). Slope of TAC did not reach statistical significance. - The optimal TBRmean cutoff value for diagnosing PsP was 1.95 with an 87% accuracy. The optimal TTP cutoff was 35 minutes with a 74% accuracy. Furthermore, the combination of TBRmean and TTP yielded a specificity and positive predictive value of 100% in diagnosing PsP. - Conventional MRI following RANO criteria did not effectively diagnose PsP (accuracy, 58%). |

*Indicates some patients in the study were also treated with lomustine and/or procarbazine.

Abbreviations: AA, Anaplastic Astrocytoma; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficients; AUC, area under the curve; BG, Background; BTV, biological tumor volume; [11C]MET, [11C]methyl-L-methionine; DFS, disease-free survival; DWI, Diffusion Weighted Imaging; [18F]FDG, 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose; [18F]FET, O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine; HGG, high-grade glioma; LBRmax, lesion to brain ratio; LGG, low-grade glioma; L/N ratio, lesion to normal [brain] ratio; MGMT, O-6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase; NA, not applicable; OS, overall survival; PCS, Postchemotherapy survival; PFS, progression-free survival; PsP, Pseudoprogression; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SoD, sum of difference; SUV, standardized uptake value; TAC, time-activity curve; TBR, tumor-to-background ratio; T:CBL ratio, active tumor uptake to mean cerebellum uptake ratio; TMZ, temozolomide; tOS, total OS; TTF, time-to-treatment failure; TTP, time to peak; Tvol, metabolically active tumor volume; T0, time of baseline imaging; T1, time of first post-treatment imaging; T2, time of second post-treatment imaging; T3, time of third post-treatment imaging.

For PET data analysis, these studies utilized a combination of static and dynamic tracer uptake parameters. For static analysis, which was performed in all studies, the tumor-to-brain, or tumor-to-background, ratio (TBR) and metabolically active tumor volume (Tvol) were most commonly used for treatment response assessment. For dynamic analysis, the pattern and slope of tracer uptake time-activity curve (TAC) was most commonly used (n = 9), followed by time-to-peak (TTP) (n = 4). All dynamic studies utilized [18F]FET because its longer half-life better allowed for the observation of tracer uptake trends across time.18,22,24–28,31,35 It is also worth noting that three of the [18F]FET-PET articles reported on the same patient cohort, although each article focused on different aspects of treatment response assessment.20,22,23

Radiochemotherapy Using Concomitant TMZ

Several studies have utilized AA PET to assess the response to RCT-TMZ in HGG patients. These studies primarily focus on detecting the correlation between AA PET findings and clinical endpoints, such as progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), and differentiating pseudoprogression from true progression.

Piroth et al. 2011, Galldiks et al. 2012, and Piroth et al. 2013 reported on the same cohort of newly diagnosed GBM patients who underwent [18F]FET-PET prior to and after being treated with RCT-TMZ, with the latter two papers including three more patients than the first (n = 22, 25, and 25, respectively).1,20,23 Piroth et al. 2013 also included data from an extended follow-up period and offered analysis of dynamic [18F]FET-PET. These three papers reported that a decrease of at least 10% in TBRmax early after completion of RCT-TMZ was a highly significant and independent statistical predictor for longer PFS and OS.20,22,23 In addition, Galldiks et al. 2012 found a decrease in Tvol 6-8 weeks after completing RCT-TMZ to be prognostic of PFS, although Piroth et al. 2013 could not confirm the same relationship. The authors attributed this discrepancy in statistical significance to a small sample size and a longer observation time in Piroth et al. 2013. Overall, the findings from this patient cohort indicated that static [18F]FET-PET following RCT-TMZ, in particular change in TBRmax, was a robust parameter to detect treatment response as early as one week post-treatment, and may thereby help to optimize individual treatment.

In a prospective longitudinal study, Suchorska et al. 2015 performed static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET on 79 newly diagnosed GBM patients prior to and after undergoing RCT-TMZ.24 Although the primary goal of this study was to identify the prognostic value of [18F]FET-PET prior to RCT-TMZ, they also assessed the correlation between post-treatment [18F]FET-PET and patient outcome. Both the Tvol and TBRmax decreased after completion of RCT-TMZ, although no further decrease was seen after three cycles of adjuvant TMZ. While Tvol and TBRmax reduction did not correlate to PFS or OS in this study, the authors found that dynamic [18F]FET uptake with an increasing TAC pattern post-treatment was associated with longer PFS, indicating that dynamic [18F]FET-PET may predict treatment response. The authors pointed out that nonspecific [18F]FET uptake in treatment-induced reactive gliosis might interfere with the differentiation between responders and nonresponders; however, Lohman et al. later demonstrated that the TAC patterns in dynamic [18F]FET-PET might help to identify reactive gliosis.26 Dynamic [18F]FET-PET will be discussed in more detail in the Static vs. dynamic section.

Kawasaki et al. 2019 performed [11C]MET-PET before and after RCT-TMZ in 30 newly diagnosed GBM patients who had undergone surgical resection.21 A -0.366 variation rate of maximum lesion/normal brain [11C]MET uptake ratio, namely a reduction in TBRmax of 36.6% or more, correlated to a longer OS of > 23 months. TBRmax decreased until nine months after RCT-TMZ with significance until three months. Meanwhile, the volume of contrast enhancement on MRI showed decrease until three months followed by an increase up to nine months, revealing a dissociation in the longitudinal changes between [11C]MET-PET and contrast-enhanced MRI.

Santoni et al. 2014 retrospectively investigated the sensitivity and specificity of [11C]MET-PET with MRI/CT in the assessment of tumor response to TMZ in anaplastic astrocytoma (n = 15) and GBM (n = 22) patients.19 The patients underwent imaging after surgical resection and throughout their TMZ treatment at 3-month intervals. The combination of [11C]MET-PET with MRI/CT distinguished treatment-related changes from residual disease with 93.97% sensitivity and 95.18% specificity in anaplastic astrocytoma, and with 96.92% sensitivity and 100% specificity in GBM patients during their RCT-TMZ and adjuvant TMZ treatment. These findings support the utility of [11C]MET-PET in monitoring postoperative tumor response and successive TMZ treatment response in HGG. In particular, [11C]MET-PET expressed maximal potential in disclosing the recurrence of anaplastic astrocytoma and GBM at an early time point in patients treated with RCT-TMZ and adjuvant TMZ.

A postmortem case study of a GBM patient whose [18F]FET-PET imaging showed tumor progression shortly after completing RCT-TMZ confirmed that increased uptake of [18F]FET in the area of equivocal contrast enhancement on MRI correlated well with dense infiltration by vital tumor cells.26 Moreover, Lohmann et al. demonstrated that the dynamic TAC patterns in the tumor area were typical of malignant gliomas (i.e. early peak followed by decline), whereas in an area of reactive astrogliosis the uptake pattern was typical of benign lesions (i.e. constant rising), and only moderate [18F]FET uptake was seen. This result provides insights into differentiating reactive gliosis from tumor using dynamic [18F]FET-PET, which may offer additional value in the diagnosis of pseudo- versus true progression (see Pseudoprogression section).

Adjuvant TMZ

While the Stupp Protocol recommends six cycles of adjuvant TMZ following concomitant RCT-TMZ for newly diagnosed GBM patients, there exists ongoing debate regarding the duration of adjuvant TMZ.1,2 Some studies have demonstrated survival benefits of extended adjuvant TMZ beyond 6 or 12 cycles.37,38 However, the optimal length is uncertain, and an effective method to monitor tumor activity is needed to allow physicians to tailor the duration of adjuvant TMZ to the individual patient’s disease course.

Galldiks et al. 2010 reported on two GBM patients on long-term adjuvant TMZ monitored periodically by [11C]MET-PET.29 Both patients displayed stable clinical courses during treatment and were documented by [11C]MET-PET as complete responses. After the discontinuation of TMZ in one patient and dosage reduction in the other at 17 and 20 cycles, respectively, both patients experienced tumor recurrence and died. Importantly, [11C]MET-PET imaging revealed tumor recurrence months prior to clinical deterioration. The authors point out that investigation regarding the continuation of long-term adjuvant TMZ in those who do not show tumor activity is warranted.

In a retrospective case-control study, Hirono et al. 2019 aimed to assess the feasibility of terminating adjuvant TMZ based on [11C]MET-PET.29 Recurrence and PFS were analyzed in 44 newly diagnosed GBM patients who completed extended adjuvant TMZ (≥ 12 cycles). Patients with no evidence of recurrence on MRI at the completion of adjuvant TMZ underwent [11C]MET-PET imaging. Compared to MRI, [11C]MET-PET showed better ability to predict tumor progression in these long-term GBM survivors. Subgroups with high [11C]MET uptake more frequently demonstrated tumor progression than those with low uptake, even with continuation of TMZ. Specifically, low uptake at the time of extended adjuvant TMZ completion was associated with a 93% lower risk for recurrence within one year after the imaging. The authors also observed that the tumor recurrence rate increased in a stepwise manner according to [11C]MET uptake. The findings of this case-control study indicated that termination of extended adjuvant TMZ based on [11C]MET uptake was feasible, and that [11C]MET-PET better-predicted tumor progression in long-term GBM survivors than MRI.

Ceccon et al. demonstrated in a prospective study that [18F]FET-PET is an effective tool to identify early responders to adjuvant TMZ in HGG patients.32 After two cycles of adjuvant TMZ, a reduction in Tvol and TBRmax predicted a significantly longer OS and PFS, independent of other known prognostic factors such as age and MGMT promoter methylation status. Meanwhile, responders identified by RANO criteria using contrast-enhanced MRI did not adequately predict clinical outcome.

Compared to RCT-TMZ, there are fewer studies that focused on the utility of AA PET in assessing response to adjuvant TMZ. While AA PET shows potential in aiding physicians in monitoring patients on adjuvant TMZ, more studies are warranted to further evaluate its role in determining the length of adjuvant TMZ in HGG patients.

TMZ Chemotherapy Monitoring

In using AA PET to monitor response to TMZ chemotherapy administered as the primary treatment, three studies focused on LGG and one study evaluated recurrent HGG patients.

Galldiks et al. 2006 performed [11C]MET-PET in 15 recurrent malignant glioma patients before and during their TMZ chemotherapy to monitor early treatment response and detect correlation to long-term response.33 All patients had previous resection and/or radiotherapy. After three cycles of TMZ chemotherapy, response could already be demonstrated with [11C]MET-PET, and absence of progression at that time indicated a high probability of further stability during the next three cycles. The absence of an increase in [11C]MET uptake, as quantified by TBRmax, during the course of TMZ chemotherapy corresponded to a stable clinical status and a favorable long-term clinical outcome. In particular, in those with declining or stable [11C]MET uptake (i.e. responders) and increasing [11C]MET uptake (i.e. nonresponders), the median time to progression was 23 and 3.5 months, respectively.

Two studies, Wyss et al. 2009 and Roelcke et al. 2016, assessed response to TMZ chemotherapy in LGG (grade II) patients with no prior treatment, using [18F]FET- or [11C]MET-PET at baseline and throughout treatment.34,36 In both studies, responders were defined as patients with at least 10% reduction of AA PET tumor volume. Of the 11 patients reported by Wyss et al., eight showed metabolic responses on [18F]FET-PET. Only three months after treatment initiation, the active [18F]FET uptake volumes decreased in two patients, whereas the first MRI volume responses were observed at six months. The time to maximal volume reduction was 8.0 ± 4.4 months for [18F]FET, and 15.0 ± 3.0 months for MRI, indicating a delay in response on MRI compared to [18F]FET-PET. The responders had longer survival (PFS 38 ± 3 months) compared to those who did not show response on AA PET or MRI (PFS 15 ± 8 months). In addition, three of the four patients who showed disease progression were later diagnosed with progression to HGG on histology. In these three patients, prominent increases in TBR and [18F]FET tumor volume were seen. Similar trend was also seen by Roelcke et al.34 Of the 33 LGG patients, a decrease in [18F]FET- or [11C]MET-PET tumor volume of ≥ 80.5% predicted a PFS of ≥ 60 months, and a decrease of ≥ 64.5% predicted a PFS of ≥ 48 months. Interestingly, a reduction of AA PET tumor volume, but not reduction in TBR or MRI tumor volumes, correlated with improved seizure control following chemotherapy. Roelcke et al. concluded that AA PET is superior to MRI for evaluating TMZ responses in grade II glioma. Both studies reported a delayed response on MRI compared to AA PET, which favored AA PET for individualizing the duration of TMZ chemotherapy. This delay indicates that change in AA metabolism is more sensitive than structural changes in response to TMZ, and that the downregulation of AA transport potentially represents an early indicator of response to TMZ chemotherapy in grade II gliomas.

Suchorska et al. 2018 performed static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET before and six months after the initiation of chemotherapy in patients with grade II (n = 44) and III (n = 17) gliomas that did not show contrast enhancement on [18F]FET MRI. It is worth noting that 8 of the 61 patients, treated prior to 2006, received procarbazine with lomustine rather than TMZ. The authors categorized [18F]FET-PET responders as those with ≥ 10% decline in TBR or ≥ 25% reduction in [18F]FET tumor volume, while progressive disease was defined as ≥ 10% increase in TBR or ≥ 25% increase in [18F]FET tumor volume. Patients with positive [18F]FET uptake that did not fall under either category were categorized as stable disease. Response assessment on MRI was done according to the RANO criteria. Suchorska et al. found [18F]FET-PET responders (n = 34) to have the longest time-to-treatment failure (mean 78.5 months) compared to all other groups on [18F]FET-PET and MRI, while there was no significant difference between stable and progressive disease on [18F]FET-PET. A comparable pattern was observed for postchemotherapy survival. Tumor volume change on T2-weighted MRI was not associated with patient outcome. The authors thus concluded that [18F]FET is a promising biomarker for early response assessment in contrast-negative glioma patients undergoing TMZ chemotherapy.

Pseudoprogression

Pseudoprogression is most clinically relevant in HGG within 12 weeks of completing RCT-TMZ, although it can also occur later in the treatment course.39 Pseudoprogression can occur with or without clinical manifestation, although in most patients pseudoprogression remains clinically asymptomatic.25 While traditional contrast-enhanced MRI cannot differentiate pseudoprogression from true progression, AA PET has shown promising results.18–20,25,31 For example, Galldiks et al. 2012 found pseudoprogression in five of 25 GBM patients treated with RCT-TMZ.20 Among the patients with pseudoprogression, significant decline of TBRmax (median change, –22%) was seen after RCT-TMZ, and Tvol determined by [18F]FET-PET remained stable, despite all patients demonstrating increased contrast enhancement volumes on MRI (median change, 433%).

Two studies, Galldiks et al. 2015 and Kebir et al. 2016, specifically focused on differentiating pseudoprogression from true progression in GBM patients with suspected progression on standard contrast-enhanced MRI18,25 Using static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET, Galldiks et al. confirmed pseudoprogression in 11 out of 22 GBM patients within the first 12 weeks after completing RCT-TMZ, demonstrating a diagnostic accuracy of 96% (sensitivity 100%, specificity 91%) using a TBRmax cutoff of 2.3. Furthermore, TBRmax < 2.3 also predicted a significantly longer OS (median, 23 months) compared to TBRmax > 2.3 (median, 12 months). Similarly, using static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET, Kebir et al. 2016 diagnosed pseudoprogression in seven of 26 GBM patients who were suspected to have late-onset progression more than three months after completion of RCT-TMZ or initiation of second-line chemotherapy. TBRmax and TBRmean were significantly lower in patients with late-onset pseudoprogression compared to true progression. A TBRmax cutoff of 1.9 achieved a diagnosis accuracy of 85% (sensitivity 84%, specificity 86%) for pseudoprogression. In addition, the authors found that all patients with late pseudoprogression had a TBRmax below 2.4, while all patients with true progression had a TBRmax above 1.0, therefore recommending these two as safe thresholds in diagnosing true progression and pseudoprogression, respectively. For patients with a TBRmax between 1.0 and 2.4, however, more caution should be used. When a pseudoprogression is misdiagnosed as true progression, unwarranted salvage treatment may be initiated. Therefore, in patients with a TBRmax value between 1.0 and 2.4, it may be most reasonable to defer salvage treatment until a later follow-up imaging or until histopathology confirms true progression, while also taking into consideration the patient’s clinical condition. It is worth noting that three of the seven patients with late-onset pseudoprogression in Kebir et al. 2016 also received lomustine, which may be associated with increased occurrence of late-onset pseudoprogression. In both of these studies, dynamic [18F]FET-PET revealed that tracer uptake TAC patterns that peaked at midpoint or early followed by constant decline were highly associated with true progression, whereas pseudoprogression was associated with a constantly increasing tracer uptake pattern and longer TTP. This observation was consistent with those seen in several other studies utilizing dynamic AA PET.24,26,28 In a later study, Werner et al. diagnosed pseudoprogression with 87% accuracy using static [18F]FET-PET in GBM patients treated with TMZ-lomustine RCT. The addition of dynamic parameter, TTP, further improved the diagnostic specificity and positive predictive value to 100%. AA PET appears to hold unique value in differentiating pseudoprogression from tumor, where conventional MRI falls short.

Recent studies have investigated artificial intelligence (AI) as a new aid in diagnosing pesudoprogression using AA PET. In most AA PET studies, the diagnostic thresholds are determined by conventional receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, however, a recent study demonstrated the feasibility of using a machine learning algorithm to diagnose pseudoprogression in GBM patients with success.40 Unlike the binary system in conventional ROC analysis, the Linear Discriminant Analysis-based machine learning algorithm allowed for a multiparameter approach and yielded higher diagnostic performance using static and dynamic [18F]FET-PET. Radiomics, another branch of machine learning, also helped accurately diagnose all pseudoprogression in a cohort of GBM patients within 12 weeks of completing RCT-TMZ.41 AI may represent an exciting direction for the future of AA PET.

Studies have reported that MGMT promoter methylation is more frequently seen in pseudoprogression patients compared to true progression, indicating an association between pseudoprogression and MGMT promoter methylation.18,25 Kebir et al. found that 86% (6/7) of patients who exhibited late pseudoprogression had methylated MGMT promoter, whereas only 58% (11/19) of patients with true early progression had MGMT methylation. MGMT methylation is known to be associated with TMZ susceptibility, and pseudoprogression may be associated with better outcomes.42 In a study aimed to determine the factors predicting the recurrence pattern determined by [18F]FET-PET in GBM patients treated according to the Stupp Protocol, Niyazi et al. found that the recurrence pattern detected on [18F]FET-PET appeared to be associated with MGMT promoter methylation status.27 Considering all 54 patients with a known MGMT status, 41.5% (12/29) of the MGMT methylated population had no relapse, 37.9% had an in-field recurrence, and 20.7% an ex-field/marginal recurrence. Meanwhile 28.0% (7/25) of the unmethylated population had no relapse, 64.0% had an in-field recurrence and 8.0% an ex-field/marginal recurrence as detected by [18F]FET-PET. Others have found that the histogram features of [11C]MET-PET may be able to detect the MGMT promoter methylation status in glioma patients and therefore predict treatment response to TMZ.43

Static vs. Dynamic

In studies with baseline imaging and continuous monitoring, decline in TBRmax appears to be the most useful predictor of outcome, especially early after treatment.20–23,31,32,35 Some studies have also demonstrated correlation between decline in TBRmean and treatment outcome, although it appears to be of weaker predictive value than TBRmax.22 In predicting clinical endpoints, some reported that a threshold of 10% reduction in TBRmax yielded optimal PFS, while a 20% reduction better-predicted OS.20,23 When longitudinal data is available, a reduction in Tvol is also a good predictor of clinical endpoints, especially in LGG.34–36 In differentiating pseudoprogression from true progression, most studies utilized a TBRmax threshold ranging from 1.9-2.3 with success.18,25,28,31 In these studies, TBR values after treatment were used for diagnosis without comparison to pretreatment TBR. Similar to clinical outcome prediction, TBRmax appears to be more accurate than TBRmean in diagnosing pseudoprogression.25

In dynamic AA PET, the consensus is that TAC pattern with early (≤ 20 min) or midpoint (≤ 40 min) peak uptake followed by constant decline or plateau is more frequently associated with true progression.18,24–28,31,35 This is a property unique to [18F]FET because its kinetics in brain tumors appear to have the highest longitudinal stability and is not observed in other AA tracers such as [11C]MET or [18F]FDOPA.44,45 Kebir et al. demonstrated 100% specificity in identifying true progressions using these two TAC patterns. Pseudoprogression, reactive gliosis, and benign tissues are associated with TAC pattern with a constantly increasing [18F]FET uptake without identifiable peak. Suchorska et al. 2015 and 2018 found that a change in TAC from decreasing to increasing was associated with longer PFS compared with those who remained decreasing; similarly, those who remained increasing had longer PFS than those changed from increasing to decreasing, indicating that dynamic [18F]FET-PET may be of importance in prognosis and treatment response assessment.24 Interestingly, in an earlier study Piroth et al. 2013 reported that changes in dynamic parameters of [18F]FET uptake before and after RCT-TMZ, including changes in TTP and the slope of TAC, showed no relationship with survival time, suggesting that dynamic [18F]FET-PET did not provide additional prognostic information during RCT-TMZ. However, Suchorska et al. pointed out that this was likely a result of difference in methods.24 For dynamic analysis, Piroth et al. defined the region of interest (ROI) as the target volume of radiotherapy, whereas Suchorska et al. implemented automatic definition of ROI on each slice using a 90% threshold. Therefore, the definition of ROI is important in dynamic AA PET analysis. In a later study by Werner et al., TTP again demonstrated additional value in the diagnosis of pseudoprogression when combined with TBR, increasing the specificity and positive predictive value to 100%.28 Overall, dynamic analysis using [18F]FET appears to increase the efficacy of AA PET in predicting treatment outcome and diagnosing pseudoprogression.

Limitations

This review was limited by the relatively small number of studies and the difficulty in delineating the effect of TMZ from other treatments in studies that utilized combined treatment modalities, such as RT and other chemotherapy agents.18–24,35 Several studies did not specify the use of TMZ or imaging timeline in relation to TMZ treatment and were therefore not included in this review.46 There have been discussions regarding the effect of TMZ on physiologic AA uptake in the brain and other factors, such as gender, BMI, and use of dexamethasone, that should be taken into account in the calculation of TBR.33,47–49 However, few studies in this review accounted for these variabilities. Utilization of AA PET in a clinical setting faces logistical challenges such as limited access, lack of officially approved indications, and difficulty receiving insurance reimbursement. However, recent endorsement by the RANO working group has increased the momentum for the adoption of AA PET on a larger scale.50 Additionally, [18F]FET was recently granted Orphan Drug Designation by the FDA for the PET imaging of glioma, signifying a promising step toward routine use of AA PET in clinical care.51

Conclusion

AA PET has demonstrated ability to predict patient survival in both HGG and LGG patients treated with TMZ therapies. AA PET imaging reveals metabolic changes in response to TMZ that occur earlier than morphological changes seen on conventional MRI. Therefore, AA PET provides a more timely indication of true tumor progression or treatment response. When longitudinal imaging is available, a post-treatment decline in TBR that meets a threshold extent correlates well with treatment response to TMZ therapy, especially early after treatment. Another useful static parameter is change in AA PET tumor volume, although Tvol may not detect response as early as does change in TBR. Most studies agree that dynamic AA PET, particularly the TAC pattern, may provide additional prognostic and diagnostic value, especially in differentiating true progression from treatment-induced changes, such as reactive gliosis and pseudoprogression. Dynamic parameters such as TTP and slope of TAC are less studied. Further assessment involving pre- and post-treatment dynamic AA PET imaging is needed, along with exploration into what might cause the tumor AA tracer uptake pattern. While AA PET has been used to assess treatment response to RCT-TMZ in HGG patients, fewer studies exist for extended adjuvant TMZ. To investigate the feasibility of using AA PET to aid in the decision of when to terminate extended adjuvant TMZ, more studies are warranted. Furthermore, as AA PET has expressed potential in treatment monitoring in LGG patients treated with TMZ chemotherapy, more studies of its kind may help establish a standard protocol and alleviate the controversy that currently exists with LGG treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tressie M. Stephens for her administrative assistance with coordinating the research and submission of this work.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

Data collection and interpretation: KYP, CMO, AMW, HJT, AKC, CAG; Idea conception and design: KYP, CMO, KLH, JDB, CAG; Drafting of original manuscript: KYP, CMO, HJT, CAG; Edits: KYP, CMO, AMW, KLH, AKC, CAG

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- 1. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alimohammadi E, Bagheri SR, Taheri S, Dayani M, Abdi A. The impact of extended adjuvant temozolomide in newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Oncol Rev 2020;14(1):461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hau P, Koch D, Hundsberger T, et al. Safety and feasibility of long-term temozolomide treatment in patients with high-grade glioma. Neurology 2007;68(9):688–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schreck KC, Grossman SA. Role of temozolomide in the treatment of cancers involving the central nervous system. Oncology (Williston Park). 2018;32(11):555–560, 569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1963–1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chukwueke UN, Wen PY. Use of the response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) criteria in clinical trials and clinical practice. CNS Oncol 2019;8(1):CNS28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Abbasi AW, Westerlaan HE, Holtman GA, et al. Incidence of tumour progression and pseudoprogression in high-grade gliomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Neuroradiol 2018;28(3):401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chakravarti A, Erkkinen MG, Nestler U, et al. Temozolomide-mediated radiation enhancement in glioblastoma: a report on underlying mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(15):4738–4746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chaskis C, Neyns B, Michotte A, De Ridder M, Everaert H. Pseudoprogression after radiotherapy with concurrent temozolomide for high-grade glioma: clinical observations and working recommendations. Surg Neurol. 2009;72(4):423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wong TZ, van der Westhuizen GJ, Coleman RE. Positron emission tomography imaging of brain tumors. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2002;12(4):615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Galldiks N, Langen KJ. Amino acid PET—an imaging option to identify treatment response, posttherapeutic effects, and tumor recurrence? Front Neurol. 2016;7(JUL). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Roelcke U. Amino acid PET monitoring in gliomas. Memo Mag Eur Med Oncol. 2015;8(2):115–118. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Najjar AM, Johnson JM, Schellingerhout D. The emerging role of amino acid PET in neuro-oncology. Bioengineering (Basel) 2018;5(4):104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grosu AL, Astner ST, Riedel E, et al. An interindividual comparison of O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET)- and L-[methyl-11C]methionine (MET)-PET in patients with brain gliomas and metastases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81(4):1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Juhasz C, Dwivedi S, Kamson DO, Michelhaugh SK, Mittal S. Comparison of amino acid positron emission tomographic radiotracers for molecular imaging of primary and metastatic brain tumors. Mol Imaging. 2014;13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cicone F, Filss CP, Minniti G, et al. Volumetric assessment of recurrent or progressive gliomas: comparison between F-DOPA PET and perfusion-weighted MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(6):905–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kebir S, Fimmers R, Galldiks N, et al. Late pseudoprogression in glioblastoma: diagnostic value of dynamic O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-Tyrosine PET. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(9):2190–2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Santoni M, Nanni C, Bittoni A, et al. [(11) C]-methionine positron emission tomography in the postoperative imaging and followup of patients with primary and recurrent gliomas. ISRN Oncol 2014;2014:463152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Galldiks N, Langen KJ, Holy R, et al. Assessment of treatment response in patients with glioblastoma using O-(2-18F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET in comparison to MRI. J Nucl Med. 2012;53(7):1048–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kawasaki T, Miwa K, Shinoda J, et al. Dissociation between 11C-methionine-positron emission tomography and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in longitudinal features of glioblastoma after postoperative radiotherapy. World Neurosurg 2019;125:93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Piroth MD, Liebenstund S, Galldiks N, et al. Monitoring of radiochemotherapy in patients with glioblastoma using O-(2-18Fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography: is dynamic imaging helpful? Mol Imaging. 2013;12(6):388–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piroth MD, Pinkawa M, Holy R, et al. Prognostic value of early [18F]fluoroethyltyrosine positron emission tomography after radiochemotherapy in glioblastoma multiforme. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;80(1):176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suchorska B, Jansen NL, Linn J, et al. Biological tumor volume in 18FET-PET before radiochemotherapy correlates with survival in GBM. Neurology 2015;84(7):710–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Galldiks N, Dunkl V, Stoffels G, et al. Diagnosis of pseudoprogression in patients with glioblastoma using O-(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42(5):685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lohmann P, Piroth MD, Sellhaus B, et al. Correlation of dynamic O-(2-[(18)F]Fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine positron emission tomography, conventional magnetic resonance imaging, and whole-brain histopathology in a pretreated glioblastoma: a postmortem study. World Neurosurg 2018;119:e653–e660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Niyazi M, Schnell O, Suchorska B, et al. FET-PET assessed recurrence pattern after radio-chemotherapy in newly diagnosed patients with glioblastoma is influenced by MGMT methylation status. Radiother Oncol. 2012;104(1):78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Werner JM, Weller J, Ceccon G, et al. Diagnosis of pseudoprogression following lomustine-temozolomide chemoradiation in newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients using FET-PET. Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27(13):3704–3713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Galldiks N, Kracht LW, Burghaus L, et al. Patient-tailored, imaging-guided, long-term temozolomide chemotherapy in patients with glioblastoma. Mol Imaging. 2010;9(1):40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hirono S, Hasegawa Y, Sakaida T, et al. Feasibility study of finalizing the extended adjuvant temozolomide based on methionine positron emission tomography (Met-PET) findings in patients with glioblastoma. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):17794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Werner JM, Stoffels G, Lichtenstein T, et al. Differentiation of treatment-related changes from tumour progression: a direct comparison between dynamic FET PET and ADC values obtained from DWI MRI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2019;46(9):1889–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ceccon G, Lohmann P, Werner JM, et al. Early treatment response assessment using (18)F-FET PET compared with contrast-enhanced MRI in glioma patients after adjuvant temozolomide chemotherapy. J Nucl Med. 2021;62(7):918–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Galldiks N, Kracht LW, Burghaus L, et al. Use of 11C-methionine PET to monitor the effects of temozolomide chemotherapy in malignant gliomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33(5):516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roelcke U, Wyss MT, Nowosielski M, et al. Amino acid positron emission tomography to monitor chemotherapy response and predict seizure control and progression-free survival in WHO grade II gliomas. Neuro Oncol 2016;18(5):744–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suchorska B, Unterrainer M, Biczok A, et al. (18)F-FET-PET as a biomarker for therapy response in non-contrast enhancing glioma following chemotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2018;139(3):721–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wyss M, Hofer S, Bruehlmeier M, et al. Early metabolic responses in temozolomide treated low-grade glioma patients. J Neurooncol. 2009;95(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roldan Urgoiti GB, Singh AD, Easaw JC. Extended adjuvant temozolomide for treatment of newly diagnosed glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2012;108(1):173–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hsieh SY, Chan DT, Kam MK, et al. Feasibility and safety of extended adjuvant temozolomide beyond six cycles for patients with glioblastoma. Hong Kong Med J. 2017;23(6):594–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stuplich M, Hadizadeh DR, Kuchelmeister K, et al. Late and prolonged pseudoprogression in glioblastoma after treatment with lomustine and temozolomide. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(21):e180–e183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kebir S, Schmidt T, Weber M, et al. A preliminary study on machine learning-based evaluation of static and dynamic FET-PET for the detection of pseudoprogression in patients with IDH-wildtype glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(11):3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lohmann P, Elahmadawy MA, Gutsche R, et al. FET PET radiomics for differentiating pseudoprogression from early tumor progression in glioma patients post-chemoradiation. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12(12):3835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):997–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yu P, Ning J, Xu B, et al. Histogram analysis of 11C-methionine integrated PET/MRI may facilitate to determine the O6-methylguanylmethyltransferase methylation status in gliomas. Nucl Med Commun. 2019;40(8):850–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Langen KJ, Stoffels G, Filss C, et al. Imaging of amino acid transport in brain tumours: Positron emission tomography with O-(2-[(18)F]fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine (FET). Methods 2017;130:124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Langen KJ, Galldiks N, Hattingen E, Shah NJ. Advances in neuro-oncology imaging. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(5):279–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Deuschl C, Kirchner J, Poeppel TD, et al. (11)C-MET PET/MRI for detection of recurrent glioma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2018;45(4):593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Verger A, Stegmayr C, Galldiks N, et al. Evaluation of factors influencing (18)F-FET uptake in the brain. Neuroimage Clin 2018;17:491–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Stegmayr C, Schöneck M, Oliveira D, et al. Reproducibility of O-(2-(18)F-fluoroethyl)-L-tyrosine uptake kinetics in brain tumors and influence of corticoid therapy: an experimental study in rat gliomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43(6):1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carideo L, Minniti G, Mamede M, et al. (18)F-DOPA uptake parameters in glioma: effects of patients’ characteristics and prior treatment history. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1084):20170847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schiff D, Van Den Bent M, Vogelbaum MA, et al. Recent developments and future directions in adult lower-grade gliomas: Society for Neuro-Oncology (SNO) and European Association of Neuro-Oncology (EANO) consensus. Neuro Oncology. 2019;21(7):838–854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Telix Granted FDA Orphan Drug Designation for Glioma Imaging Agent North Melbourne, Australia: Telix Pharmaceuticals Limited; 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.