Abstract

Background

Cholecystectomy is one of the most frequently performed operations. Open cholecystectomy has been the gold standard for over 100 years. Small‐incision cholecystectomy is a less frequently used alternative. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was introduced in the 1980s.

Objectives

To compare the beneficial and harmful effects of laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (6 April 2004), The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2004), MEDLINE (1966 to January 2004), EMBASE (1980 to January 2004), Web of Science (1988 to January 2004), and CINAHL (1982 to January 2004) for randomised trials.

Selection criteria

All published and unpublished randomised trials in patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis comparing any kind of laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus small‐incision or other kind of minimal incision open cholecystectomy. No language limitations were applied.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently performed selection of trials and data extraction. The methodological quality of the generation of the allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, and follow‐up was evaluated to assess bias risk. Analyses were based on the intention‐to‐treat principle. Authors were requested additional information in case of missing data. Sensitivity and subgroup analyses were performed if appropriate.

Main results

Thirteen trials randomised 2337 patients. Methodological quality was relatively high considering the four quality criteria. Total complications of laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy are high: 26.6% versus 22.9%. Total complications (risk difference, random‐effects ‐0.01, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.07 to 0.05), hospital stay (weighted mean difference (WMD), random‐effects ‐0.72 days, 95% CI ‐1.48 to 0.04), and convalescence were not significantly different. High‐quality trials show a quicker operative time for small‐incision cholecystectomy (WMD, high‐quality trials 'blinding', random‐effects 16.4 minutes, 95% CI 8.9 to 23.8) while low‐quality trials show no significant difference.

Authors' conclusions

Laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy seem to be equivalent. No differences could be observed in mortality, complications, and postoperative recovery. Small‐incision cholecystectomy has a significantly shorter operative time. Complications in elective cholecystectomy are prevalent.

Plain language summary

Laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy seem equivalent in complications and recovery, but small‐incision cholecystectomy is quicker to perform

The laparoscopic and the small‐incision cholecystectomy are two alternative minimally invasive techniques for removal of the gallbladder. There are no significant differences in mortality and complications between the two minimal invasive procedures. The laparoscopic and the small‐incision operation should be considered equal apart from a quicker operative time using the small‐incision technique. The complications in both techniques are common.

Background

Gallstones are one of the major causes of morbidity in western society. It is estimated that the incidence of symptomatic cholecystolithiasis is up to 2.17 per thousand inhabitants (Legorreta 1993; Steiner 1994) with an annual performance rate of cholecystectomies of more than 500,000 in USA (Olsen 1991; NIH Consensus 1993; Roslyn 1993). Until the end of the 1980s, open cholecystectomy was the gold standard for treatment of stones in the gallbladder. As incisions for cholecystectomy were shortened resulting in 'small‐incision' cholecystectomy, morbidity and complications seemed to decline and patients recovered faster. In the early 1970s small‐incision cholecystectomy was introduced as a minimal invasive procedure (Dubois 1982; Goco 1983). This technique was introduced in order to decrease surgical trauma and consequently accelerate convalescence. Conflicting data on clinical outcome and effectiveness arose from studies evaluating this technique.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was introduced in 1985 (Mühe 1986) and rapidly became the method of choice for surgical removal of the gallbladder (NIH Consensus 1993) although the evidence of superiority over small‐incision cholecystectomy was absent. This rising popularity was based on many arguments, including assumed lower morbidity and complication proportions, and a quicker postoperative recovery compared to open cholecystectomy and despite an increase in bile duct lesions. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy seemed superior to small‐incision cholecystectomy (Dubois 1982; Goco 1983; Moss 1986; Merrill 1988; Ledet 1990; O'Dwyer 1990; O'Dwyer 1992; Assalia 1993a; Olsen 1993; Tyagi 1994; Downs 1996; Assalia 1997; Schmitz 1997; Seale 1999). However, the aforementioned studies were non‐randomised observations, which may not provide an adequate assessment of intervention effects.

Differences in primary outcomes like mortality and complication proportions (particularly bile duct injuries) are important reasons to choose one of the operative techniques. When these primary outcomes show no significant difference, then secondary outcomes like non‐severe complications, pulmonary outcomes, differences in health status related quality‐of‐life, hospital stay, and differences in cost‐effectiveness analysis should help decide which technique is superior.

Up to now, despite the availability of numerous randomised trials on this topic, no systematic review or meta‐analysis of such trials has been conducted in order to compare laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy. This lack of evidence was the main reason for writing this systematic review. The objective was to evaluate the assumed superiority of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Objectives

To evaluate the beneficial and harmful effects of two different types of cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. To assess whether laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy are different in terms of primary (mortality, complications, and relief of symptoms) and secondary outcomes (conversions to open cholecystectomy, operative time, hospital stay, and convalescence). If data were present, differences in other secondary outcomes like analgesic use, postoperative pain, pulmonary function, and costs were compared as well.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised clinical trials comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy to small‐incision or other kind of minimal‐incision open cholecystectomy. Trials were included irrespectively of blinding, number of patients randomised, and language of the article. Quasi‐randomised studies were excluded.

Types of participants

Patients with one or more stones in the gallbladder confirmed by ultrasonography or other imaging technique and symptoms attributable to them, scheduled for cholecystectomy. Acute cholecystitis is a disease with different operative results including the number of complications and conversions. Cholecystectomy in patients suffering from acute cholecystitis should be distinguished from cholecystectomy in patients suffering from symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Therefore, randomised trials only including patients with acute cholecystitis were excluded from this review. Randomised trials including both symptomatic cholecystolithiasis and acute cholecystitis were included in the review only if the large majority (more than half) of the included patients were operated on because of symptomatic cholecystolithiasis.

Types of interventions

Any kind of laparoscopic cholecystectomy was assessed versus any kind of small‐incision cholecystectomy.

The following classifications of the surgical procedures (based on intention‐to‐treat) were used: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy includes those procedures started as a laparoscopic procedure. Any kind of laparoscopic cholecystectomy with creation of a pneumoperitoneum (by Veress needle or open introduction) or mechanical abdominal wall lift, irrespective of the number of trocars used. Only if the words 'small‐incision', 'minimal access', 'minilaparotomy' or similar as intended terms were mentioned in the primary classification of the procedure, the surgical intervention was classified as a 'small‐incision' cholecystectomy (eg, length of incision of less than 8 cm). The length of incision up to 8 cm was chosen arbitrary as in literature most authors used this length as a cut‐off point between small‐incision and (conversion to) open cholecystectomy. In all other cases the surgical intervention was classified as 'open cholecystectomy' and was excluded.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcome measures are mortality, complication proportions (intra‐operative, severe, bile duct injuries, and total complications; except minor complications), and relief of symptoms (pain relief). Although relief of symptoms is the aim of cholecystectomy, some patients continue to suffer from their complaints and have persistent pain. Most important in obtaining a high proportion of patients with relief of symptoms is adequate decision making in setting the indication to operate or not. However, it cannot be ruled out that some of this persistent pain should be attributed to the way of incision for cholecystectomy. Therefore it is of interest to include pain relief as a primary outcome.

Secondary outcome measures are all other outcomes assessed in comparing the two operative techniques. We assessed the following secondary outcomes: conversion proportions to open cholecystectomy, operative time, hospital stay, convalescence, analgesic use, postoperative pain (visual analogue scale), health status related quality‐of‐life, pulmonary outcome (pulmonary function tests by flow‐volume curves), and cost‐effectiveness if data were available.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following databases: The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (6 April 2004), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, all in The Cochrane Library (Issue 1, 2004), The National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE) (1966 to January 2004), The Intelligent Gateway to Biomedical & Pharmacological Information (EMBASE) (1980 to January 2004), ISI Web of Knowledge (Web of Science) (1988 to January 2004), and CINAHL (1982 to January 2004). The search strategies used are provided in Appendix 1.

Our aim was to perform a maximal sensitive search in order to conduct a more complete review. As describing an operation of the gallbladder in medical terms without the word cholecystectomy is impossible, a maximal sensitive search with the term cholecystectomy was used. For our MEDLINE search, a more sophisticated strategy, advised by the Dutch Cochrane Centre and listed in Appendix 1 was used (with help from Geert van der Heijden, Julius Center, Utrecht).

Additional relevant trials were looked for by cross reference checking of identified randomised trials. Finally all authors of included trials were requested by letter for additional information on any published, unpublished, or ongoing trials.

Furthermore, during data extraction it turned out that in a large number of trials essential data and information on methods were missing. To improve the quality of the analysis, individual trialists were contacted and asked for missing data.

Data collection and analysis

The review was conducted according to the present protocol (Keus 2004) and the recommendations by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2005). All identified trials were listed in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table and an evaluation whether the trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria was made. Excluded trials and the reasons for exclusion were listed as well (table with 'Characteristics of excluded studies').

Assessment of methodological quality Inadequate methodological quality in randomised controlled trials carries the risk of overestimating intervention effects (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001). Methodological quality, study design, and reporting quality have been recognised as criteria which can restrict bias in the comparisons of interventions (Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001). Therefore the methodological quality of randomised clinical trials was assessed using the following components.

Generation of the allocation sequence

Adequate, if the allocation sequence was generated by a computer or random number table. Drawing of lots, tossing of a coin, shuffling of cards, or throwing dice was considered as adequate if a person who was not otherwise involved in the recruitment of participants performed the procedure.

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used for the allocation sequence generation was not described.

Inadequate, if a system involving dates, names, or admittance numbers were used for the allocation of patients. These studies are known as quasi‐randomised and were excluded from the present review.

Allocation concealment

Adequate, if the allocation of patients involved a central independent unit, on‐site locked computer, or sealed envelopes.

Unclear, if the trial was described as randomised, but the method used to conceal the allocation was not described.

Inadequate, if the allocation sequence was known to the investigators who assigned participants or if the study was quasi‐randomised.

Blinding

Adequate, if the trial was described (at least) as blind to participants or assessors and the method of blinding was described. We are well aware that it is very difficult to properly blind trials comparing surgical treatments.

Unclear, if the trial was described as (double) blind, but the method of blinding was not described.

Not performed, if the trial was not blinded.

Follow‐up

Adequate, if the numbers and reasons for dropouts and withdrawals in all intervention groups were described or if it was specified that there were no dropouts or withdrawals.

Unclear, if the report gave the impression that there had been no dropouts or withdrawals, but this was not specifically stated.

Inadequate, if the number or reasons for dropouts and withdrawals were not described.

Extraction of data Inclusion and exclusion criteria used in each trial.

The following data on the randomisation procedure have been extracted: (1) Number of randomised patients (2) Number of patients not randomised and reasons for non‐randomisation (3) Exclusion after randomisation (4) Drop‐outs (5) 'Intention‐to‐treat' analysis.

Also information on sample size, single‐ or multicentre study design, assessment of primary and secondary outcome measures, use of antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical experience, and intra‐operative cholangiography was registered (Table 1).

1. Randomised, excluded, and included in LC versus SIC.

| Trial | Randomised | Excluded | Included LC | Included SIC | cholangiography | antibiotics | surgical expertise |

| Barkun 1992 | 70 | 8 | 37 | 25 | N | Y | SS |

| Bruce 1999 | 22 | 0 | 11 | 11 | U | Y | SS |

| Coelho 1993 | 45* | 0 | 15 | 15 | U | U | U |

| Grande 2002 | 40 | 0 | 18 | 22 | N | Y | U |

| Keus 2006 | 270 | 13 | 120 | 137 | N | Y | R |

| Kunz 1992 | 100 | 0 | 50 | 50 | U | U | U |

| Majeed 1996 | 203 | 3 | 100 | 100 | Y | U | SS |

| McGinn 1995 | 310 | 0 | 155 | 155 | N | U | R |

| McMahon 1994 | 302 | 3 | 151 | 148 | N | Y | R |

| Ros 2001 | 726 | 2 | 362 | 362 | Y | U | R |

| Secco 2002 | 181 | 9 | 86 | 86 | N | Y | S |

| Srivastava 2001 | 100 | 1 | 59 | 40 | N | U | SS |

| Tate 1993 | 22 | 0 | 11 | 11 | U | U | SS |

| Total | 2391 | 39 | 1175 | 1162 | |||

| * three‐arm trial, patients in the OC group not listed in this table. | N = no | Y = yes | U = unknown | S = one surgeon | SS = a few surgeons | R = also registrars |

General descriptive data (like sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification) are supposed to be equally divided due to randomisation (Assmann 2000). These data are presented in Table 2 as far as available. Outcome data on mortality, complications, health‐related quality‐of‐life, pulmonary function, pain, duration of operation, hospital stay, and convalescence were extracted according to availability.

2. Description of background data (age, sex, BMI, and ASA).

| Trial | N | Age | Age | Sex (m/f) | Sex (m/f) | BMI | BMI | ASA (I‐II‐III‐IV) | ASA (I‐II‐III‐IV) |

| LC vs SIC | randomised | LC | SIC | LC | SIC | LC | SIC | LC | SIC |

| Barkun 1992 | 37 / 25 | 51.4 (16.1) | 52.3 (18.7) | 11 / 26 | 6 / 19 | 25.8 (4.6) | 27.5 (5.8) | 31 ‐ ? ‐ ? ‐ ? | 23 ‐ ? ‐ ? ‐ ? |

| Bruce 1999 | 11 / 11 | 48* (37‐56)$ | 48* (37‐63)$ | 2 / 9 | 2 / 9 | 26.5* (23‐29)$ | 26.3* (24‐31)$ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Coelho 1993 | 15 / 15 | 42.7 (25‐70) | 42.5 (25‐66) | 3 / 12 | 2 / 13 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Grande 2002 | 18 / 22 | 41.3 (9.7) | 42.3 (9.7) | 6 / 12 | 12 / 10 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Keus 2006 | 120 / 137 | 48.4 (14.1) | 48.5 (14.0) | 31 / 89 | 30 / 107 | 27.5 (4.8) | 27.9 (4.6) | 81 ‐ 39 ‐ 0 ‐ 0 | 91 ‐ 46 ‐ 0 ‐ 0 |

| Kunz 1992 | 50 / 50 | nd | nd | nd | nd | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Majeed 1996 | 100 / 100 | 48.9 (14.6) | 51.1 (15) | 20 / 80 | 19 / 81 | 27.4 (4.5) | 26.6 (4.6) | 58 ‐ 39 ‐ 3 ‐ 0 | 56 ‐ 36 ‐ 8 ‐ 0 |

| McGinn 1995 | 150 / 150 | 53* (18‐81) | 57* (26‐84) | 42 / 108 | 46 / 104 | 25 (3.6) | 26 (5.3) | ‐ | ‐ |

| McMahon 1994 | 151 / 148 | 54* (41‐64) | 52* (41‐63) | 18 / 133 | 24 / 124 | 26.7 (4.8) | 26.1 (4.8) | 66 ‐ 61 ‐ 19 ‐ 5 | 66 ‐ 51 ‐ 25 ‐ 6 |

| Ros 2001 | 362 / 362 | 50.3 (15.1) | 50.9 (16.1) | 110 / 252 | 113 / 249 | 27.3 (4.3) | 26.6 (4.4) | 346 ‐ 14 ‐ 0 | 346 ‐ 14 ‐ 0 |

| Secco 2002 | 86 / 86 | 54* (23‐83) | 52* (19‐76) | 34 / 52 | 31 / 55 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Srivastava 2001 | 59 / 40 | 41.1 (37‐44)^ | 39.2 (35‐42)^ | 4 / 55 | 9 / 31 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Tate 1993 | 11 / 11 | 38.6 (10.5) | 49.9 (11.9) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| * median | ^ confidence interval | $ inter quartile range | nd: 'no difference' reported |

Statistical analysis With adequate binary data available, a priori presentation in odds ratios was preferred, based on clinical considerations and statistical robustness of the odds ratio. From this, results could be presented in relative risk (ratio) (RR(R)) or numbers needed to treat (NNT) by recalculation. However exploring the data showed that for many binary data the outcome was rare or zero in both arms. Odds ratios (OR) and risk ratios (RR) are not estimable in trials with zero events in both arms (Sweeting 2004). Binary outcomes with zero events in both arms can merely be presented in risk differences (RD). Although risk differences are statistically less robust and result in conservative estimates, they are simple measures, easy to understand, and useful for public communication.

For continuous data, authors generally present their results in medians with ranges due to suspicion of skewed data. However, for the analysis of data in a meta‐analysis, means with their corresponding standard deviations (SD) are needed to calculate mean differences (MD) or weighted mean differences (WMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Using means from all trials would ignore a non‐Gaussian distribution. Therefore, skewness ratios (mean divided by the standard deviation) were calculated first (Higgins 2005, page 96). With a ratio larger than two, skewness is ruled out, whereas skewness is suggested when the ratio is between one and two and a ratio less than one indicates strong evidence of skewness. In situations where skewness could be ruled out, assumptions on equality of median to mean was made and used in the sensitivity analyses. For trials presenting confidence intervals or standard error of means, we performed a recalculation to a standard deviation (SD) (Higgins 2005, page 90‐91). In case no data on standard deviation was available, we calculated an average standard deviation from those observed in other studies and imputed this value for the standard deviation in the sensitivity analysis (Higgins 2005, page 92).

Results were considered according to the four different criteria of quality. The existence of an overall difference in outcome was clear when all four criteria showed significance. However, when the different quality criteria showed contradicting results, then an overall conclusion considering one outcome was not obvious and had to be made individually. In each individual component, results from high‐quality trials subgroups were given more weight compared to analyses including all trials or low‐quality trials subgroups. Results with confidence intervals that touched, but did not cross, the line of equivalence were considered not significant.

Apart from comparisons in the four individual quality criteria, another comparison was performed with trials divided into low‐bias risk trials (high methodological quality) and high‐bias risk trials (low methodological quality). Trials that were assessed as adequate regarding all four methodological criteria were considered low‐bias risk trials. All trials that were not assessed as adequate with regard to all the four methodological criteria were considered high‐bias risk trials.

Bias detection We have used funnel plots to provide a visual assessment of whether treatment estimates were associated with study size. The presence of publication bias and other biases (Begg 1994; Egger 1997; Macaskill 2001) varies with the magnitude of the treatment effect, the distribution of study size, and whether a one‐ or two‐tailed test is used (Macaskill 2001).

Both the random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) and the fixed‐effect model (DeMets 1987) for pooling effect estimates were explored.

In case of no discrepancy (and no heterogeneity) the fixed‐effect models were presented.

In case of discrepancy between the two models (ie, one giving a significant intervention effect and the other no significant intervention effect) both results were reported. Discrepancy will only occur when substantial heterogeneity is present.

Most weight was put on the results of the fixed‐effect model if the meta‐analysis included one or more large trials, provided that they had adequate methodology. (By large trials we refer to those that outnumber the rest of the included trials in terms of numbers of outcomes and participants (ie, more than half of all included events and participants)).

Otherwise, most weight was put on the results of the random‐effects model as it incorporated heterogeneity. The reason for this was that the random‐effects model increases the weight of small trials. Small trials however are more often than large trials conducted with unclear or inadequate methods (Kjaergard 2001).

In situations of excessive heterogeneity we refrained from reporting a pooled estimate when inappropriate.

The main focus of looking at heterogeneity in meta‐analysis is to discriminate true effect modifiers from other sources of heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was calculated by the Cochrane Q test and quantified by measuring I2 (Higgins 2002). If excessive heterogeneity occurred, data were re‐checked first and then adjusted. Extreme outliers were excluded (and tested in sensitivity analyses) when adequate reasons were available. If excessive heterogeneity still remained, depending on the specific research question, alternative methods were considered: subgroup analysis and meta‐regression if appropriate.

Subgroup analysis Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the effects of the interventions according to the methodological quality of the trials (adequate compared to unclear/inadequate). Furthermore, causes of heterogeneity (defined as the presence of statistical heterogeneity by chi‐squared test with significance set at P‐value < 0.10 and measured by the quantities of heterogeneity by I2 (Higgins 2002)) were explored by comparing different groups of trials stratified to level of experience of the surgeon and other factors that may explain heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed assuming zero mortality and zero conversions for missing data. Sensitivity analyses were performed imputing medians and using average standard deviations for missing data. In case of outliers and borderline trials sensitivity analyses were performed as well. Subgroup analyses were performed testing the influence of antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical experience and intra‐operative cholangiography on operative time, complications and hospital stay. These subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed as far as data were available.

The statistical package (RevMan Analyses) provided by The Cochrane Collaboration was used (RevMan 2003). The statistical analyses were performed by FK and CL.

Results

Description of studies

Searches and trial identification For the search strategies used and the number of hits we refer to Appendix 1.

The search was conducted in The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (840 hits, 65 selected) and The Cochrane Library, Issue 1, 2004 with the following results: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (33 hits, none were selected), the Database of Abstracts of Reviews on Effects (DARE) (17 hits, 5 selected), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (1343 hits, 146 selected), the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database (11 hits, 4 selected), and the NHS Economic Evaluation Database (43 hits, 6 selected).

The search further comprised the following databases: The National Library of Medicine (MEDLINE) (8354 hits, 347 selected), The Intelligent Gateway to Biomedical & Pharmacological Information (EMBASE) (685 hits, 131 selected), ISI Web of Knowledge (Web of Science) (1163 hits, 148 selected), and CINAHL (740 hits, 9 selected).

Altogether, the search resulted in 13229 hits. The first selection process was performed based on the title of the publications. In each step of selection, we included the publication in case of any doubt. The total number of selections by title from this group of 13229 publications was 911 hits. After correction for duplicates, 586 remained.

The abstracts of these 586 publications were reviewed independently by two reviewers (FK and JJ) in order to evaluate whether the study should be included in the review. Differences between FK and JJ were discussed with CL. A total of 428 publications could be rejected based on their abstract. Initially, trials which did not clearly mention whether they were randomised clinical trials or not, were given the benefit of the doubt. If appropriate, they were excluded later on. Eventually, 158 publications were selected for further evaluation and these are all listed in this review with reasons for in‐ or exclusion.

A total of 123 publications were excluded (see table with 'Characteristics of excluded studies'). A total of 35 publications describing 13 trials including 2337 patients were included (see table with 'Characteristics of included studies' and Table 1). Critical appraisal and data extraction of these 13 trials were done by FK, JJ, and CL separately. Any disagreements were solved in several consensus meetings.

The study by Redmond (Redmond 1994) is excluded because of no correct randomisation. However this study must be considered a borderline case, therefore the results of this study were included in sensitivity analyses on total complications and operative time. For data management reasons this study is listed in the characteristics of included studies table.

Of the 13 included trials, one trial was only described in short (comment: Tate 1993). Therefore only limited information was obtained from this trial. As no language restrictions were used, one publication (Secco 2002) was translated. Double publications of the trial results by the same research group are listed in the references of included studies, and are considered one trial (eg, McMahon 1994; Bruce 1999). After contacting individual trialists additional data and information were obtained from 3 out of 13 included trials (see acknowledgement).

Patient characteristics All included trials used similar inclusion criteria, ie, patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis who were scheduled for elective cholecystectomy. The extensiveness in which exclusion criteria were described varied among the trials, but nearly all trials excluded acute cholecystitis. Trials with exclusively acute cholecystitis as inclusion criterion for cholecystectomy were excluded. Trials that included minorities of patients with acute cholecystitis in addition to patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis were included.

Trial designs Only one trial used a three‐arm design (Coelho 1993). All other trials used a two arm, parallel‐group design.

Surgical interventions Usually laparoscopic cholecystectomy was not further specified. Some trials stated that a four trocar technique was used, creating a pneumoperitoneum by using carbon dioxide insufflation with a maximum intraperitoneal pressure of 12 to 15 millimetres mercury. As noted before, an incision length of 8 centimetres was taken as the cut‐off point between small‐incision and open cholecystectomy. Some trials using the small‐incision technique did not mention the size of the incision. We classified these trials as a small‐incision cholecystectomy and not an open cholecystectomy, based on how the author labelled the operation procedure. Two trials performed small‐incision cholecystectomy by a 5 centimetres midline incision, the others by a transverse subcostal incision, some with muscle splitting, others by transsection of the rectus or oblique muscles.

Antibiotic prophylaxis administered at induction of anaesthesia was explicitly mentioned in some trials. In others the explicit omission of antibiotic prophylaxis was mentioned, but most trials did not report on its use. Information on surgical experience (one or a few highly experienced surgeons performing all operations or also involving registrars) and intra‐operative cholangiography (attempted in all or only in selected patients) was recorded as well.

Outcome measures A problem considering relief of symptoms and pain is how this outcome is defined and measured. Apart from differences in measurement, very few trials reported on this outcome. Therefore, we were unable to report results considering relief of symptoms and pain. Nearly all trials reported on complications, operative time, and hospital stay. We analysed conversion proportions between both techniques. Duration of sick leave was another commonly examined outcome. Not all trials clearly mentioned mortality. In trials in which mortality remained unclear, only in a sensitivity analysis the assumption that no patient had died was made when mortality was not mentioned (mean and most probable outcome of a trial). Some trials included mortality in their complications; we considered them separately. Because of the wide range of the types of complications described, we classified (subcategorised) all complications into four subcategories (intra‐operative, minor, severe, or bile duct injury) in addition to a total complication proportion (Table 3). Each complication was classified twice: once in one of the four subcategories (intra‐operative, minor, severe, or bile duct injury) and once again in the total complication proportion. Consequently, all bile duct complications were registered separately from all other complications (and not counted in the severe and minor subcategories). Likewise, all intra‐operative complications (except from the bile duct injuries) were categorised separately from other minor and severe complications.

3. Complications specified per operative technique: LC versus SIC.

| Complications | LC | SIC |

| INTRA‐OPERATIVE | (153 / 13.1%) | (88 / 7.6%) |

| galbladder perforation | 112 | 62 |

| bleeding | 23 | 19 |

| stone in common bile duct | 0 | 1 |

| stone left in abdomen | 10 | 0 |

| vascular injury (hepatic artery) | 0 | 1 |

| bowel injury | 5 | 3 |

| hepatic injury | 1 | 1 |

| cardiac | 1 | 1 |

| cerebrovascular | 1 | 0 |

| POSTOPERATIVE ‐ MINOR | (97 / 8.3%) | (106 / 9.2%) |

| thrombo‐embolic event | 2 | 1 |

| retained bile duct stone (ERCP) | 4 | 1 |

| subcutaneous emphysema | 1 | 0 |

| wound infection | 36 | 52 |

| wound hematoma | 6 | 0 |

| urinary retention | 8 | 18 |

| urinary tract infection | 5 | 11 |

| flebitis | 3 | 0 |

| dyspeptic syndrome | 11 | 12 |

| other | 21 | 11 |

| POSTOPERATIVE ‐ SEVERE | (46 / 4.0%) | (48 / 4.2%) |

| bleeding: drainage / bloodtransfusion | 11 | 4 |

| bleeding: re‐operation | 6 | 3 |

| ileus (re‐operation) | 1 | 2 |

| pancreatitis | 3 | 6 |

| abscess (drainage / unspecified) | 2 | 5 |

| abscess (re‐operation) | 1 | 1 |

| pneumonia | 14 | 18 |

| septic shock | 2 | 0 |

| septic shock (re‐operation) | 0 | 1 |

| cardiovascular | 2 | 6 |

| cerebrovascular accident | 1 | 1 |

| hernia cicatricalis | 2 | 1 |

| epididymitis (re‐operation) | 1 | 0 |

| BILE DUCT INJURY | (14 / 1.2%) | (22 / 1.9%) |

| cystic duct leakage: drainage/ERCP | 2 | 1 |

| cystic duct leakage: re‐operation | 0 | 3 |

| accessory duct leakage (re‐operation) | 0 | 1 |

| minor common bile duct injury (intra‐operative) | 5 | 3 |

| major common bile duct injury: re‐operation | 3 | 2 |

| hepatic duct injury (intra‐operative) | 0 | 1 |

| bile leakage (origin unknown): conservative | 2 | 8 |

| bile leakage (origin unknown): re‐operation | 2 | 3 |

| TOTAL COMPLICATIONS | 310 (26.6%) | 264 (22.9%) |

| RE‐OPERATIONS (all complications) | 19 (1.6%) | 18 (1.6%) |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF PATIENTS INCLUDED (all trials) | 1175 | 1162 |

The following outcomes were reported in one trial only or in different ways: bowel function, immunological parameters and cytokines, acute phase proteins, and acute phase hormones. Pain scores and analgesic use as well as health status related quality‐of‐life were frequently examined outcomes. Due to the great variation in the way these were measured and reported, it appeared impossible to pool results.

Considering pulmonary function there is some limited data available from randomised trials. However, considering the inconsistency in the type of effect measure reported, as well as the difference in moments in time the outcome was measured, and the statistical problems that arise in pooling these results, we decided to refrain from reporting these results. Our intention was to cover costs (an important secondary outcome) as well, but although costs were described in several trials, it was reported in a lot of different ways. Moreover, as different points of view were taken in those analyses, and regarding the cultural differences (Vitale 1991) as well as differences in local costs, we decided that reporting this outcome would not be meaningful.

Risk of bias in included studies

We evaluated the internal validity of the trials by considering the four quality components, resulting in the following number of high‐quality (ie, adequate) trials. Information that was not mentioned in a trial, was scored 'unclear'. When necessary information about randomisation, blinding procedure, or follow‐up was unclear or missing, the authors were contacted to obtain specific additional information on these issues. Trials of which no response was received, remained classified as 'unclear' trials.

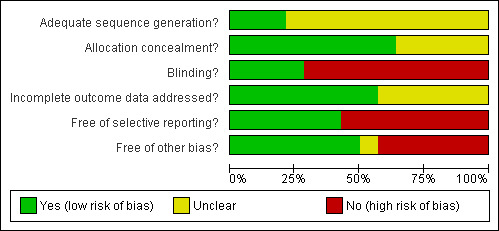

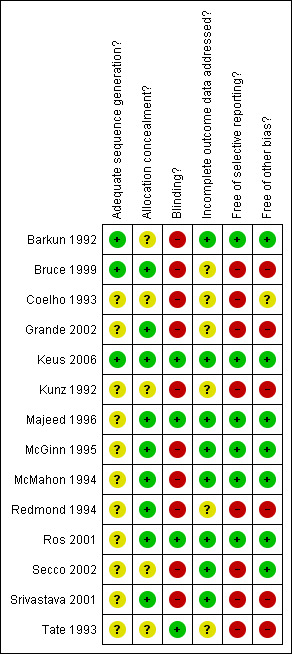

We assessed the quality of the 13 included trials as follows: generation of allocation sequence was adequate in three trials (23.1%), allocation concealment in eight trials (61.5%), blinding in four trials (30.8%), and follow‐up in eight trials (61.5%) (Table 4) (Figure 1; Figure 2).

4. Internal validity assessment of included trials: LC vs SIC.

| Trial | Generation of alloc | Concealment of alloc | Blinding | Follow‐up |

| Barkun 1992 | A | U | N | A |

| Bruce 1999 | A | A | N | U |

| Coelho 1993 | U | U | N | U |

| Grande 2002 | U | A | N | U |

| Keus 2006 | A | A | A | A |

| Kunz 1992 | U | U | N | U |

| Majeed 1996 | U | A | A | A |

| McGinn 1995 | U | A | N | A |

| McMahon 1994 | U | A | N | A |

| Ros 2001 | U | A | A | A |

| Secco 2002 | U | U | N | A |

| Srivastava 2001 | U | A | N | A |

| Tate 1993 | U | U | A | U |

| A: Adequate | U: Unclear | I: Inadequate | N: Not performed |

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

A comparison dividing trials into low‐bias risk trials (adequate methodological quality in all four criteria) versus high‐bias risk trials could not be performed as only one trial was considered low‐bias risk.

Effects of interventions

We conducted five analyses: four comparisons based on the four methodological quality components including the subgroups high‐ and low‐quality trials, and a fifth comparison containing sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Background data of all trials on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification are shown in Table 2.

We identified a total of 13 randomised trials comparing laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy, including one trial described in a comment (Tate 1993) and one unpublished trial (Keus 2006). A total of 1175 and 1162 patients were included in the laparoscopic and small‐incision groups respectively. Data are presented in Table 1 together with data on antibiotic prophylaxis, performance of cholangiography, and experience of the surgeon.

We defined a complication as something the author called a complication and refrained from our own interpretation, except for a non‐aesthetic scar (Secco 2002): we agreed on this not being regarded as a complication.

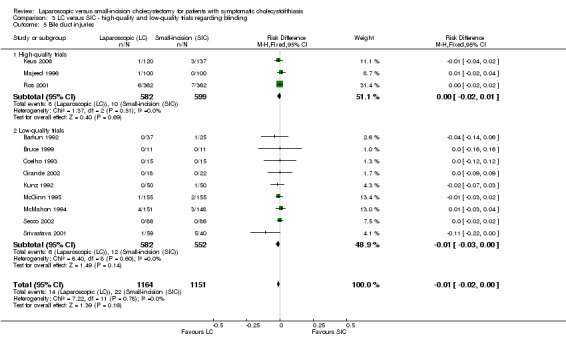

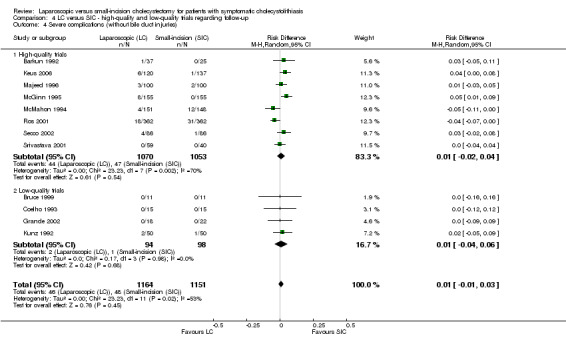

In the analyses, there were no significant differences in mortality, minor complications, severe complications, and bile duct injuries considering all trials, neither in the subgroups high‐quality and low‐quality trials, nor between the fixed‐effect model and the random‐effects model. As 'concealment of allocation' is considered the most important component of methodological quality, all subgroup results considering this aspect (except for the fore‐mentioned results that were not significantly different) were presented in additional Table 5.

5. Results of LC vs SIC: allocation concealment (comparison 2).

| Outcome | RD/WMD | HQ/LQ/AT | Fixed | Random | Discrepancy | Emphasize | HQ‐LQ difference | Significant |

| intraoperative complications | RD | HQ | 0.07 (0.04, 0.09) * | 0.02 (‐0.04, 0.08) | yes | |||

| LQ | 0.00 (‐0.02, 0.02) | 0.00 (‐0.02, 0.02) | no | |||||

| AT | 0.06 (0.03, 0.08) * | 0.01 (‐0.03, 0.06) | yes | random | no | no | ||

| total complications | RD | HQ | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08) * | ‐0.01 (‐0.09, 0.07) | yes | |||

| LQ | 0.01 (‐0.05, 0.08) | ‐0.01 (‐0.06, 0.05) | no | |||||

| AT | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07) * | ‐0.01 (‐0.07, 0.05) | yes | random | no | no | ||

| conversion rate | RD | HQ | ‐0.03 (‐0.06, 0.00) | ‐0.01 (‐0.07, 0.04) | no | |||

| LQ | 0.01 (‐0.04, 0.07) | 0.02 (‐0.03, 0.07) | no | |||||

| AT | ‐0.02 (‐0.05, 0.01) | 0.00 (‐0.05, 0.04) | no | random | no | no | ||

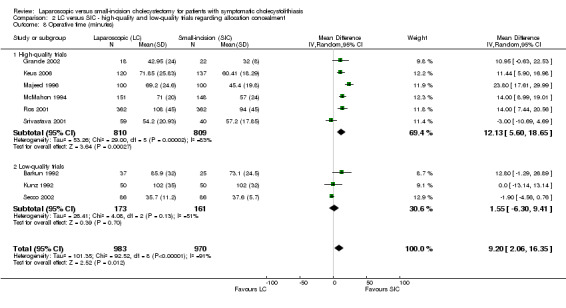

| operative time | WMD | HQ | 13.06 (10.44, 15.67) * | 12.13 (5.60, 18.65) * | no | |||

| LQ | ‐1.34 (‐3.90, 1.22) | 1.55 (‐6.30, 9.41) | no | |||||

| AT | 5.70 (3.87, 7.53) * | 9.20 (2.06, 16.35) * | no | random | yes | yes | ||

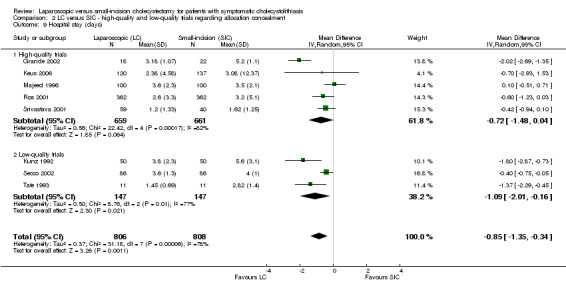

| hospital stay | WMD | HQ | ‐0.65 (‐0.95, ‐0.35) * | ‐0.72 (‐1.48, 0.04) | yes | |||

| LQ | ‐0.63 (‐0.94, ‐0.32) * | ‐1.09 (‐2.01, ‐0.16) * | no | |||||

| AT | ‐0.64 (‐0.85, ‐0.43) * | ‐0.85 (‐1.35, ‐0.34) * | no | random | yes | no | ||

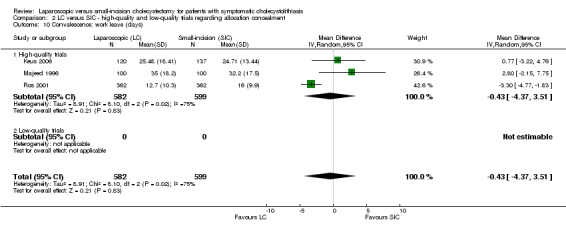

| convalescence work leave | WMD | HQ | ‐0.30 (‐0.83, 0.23) | ‐0.69 (‐3.61, 2.23) | no | |||

| LQ | no data | no data | ‐ | |||||

| AT | ‐0.30 (‐0.83, 0.23) | ‐0.69 (‐3.61, 2.23) | no | random | ‐ | no | ||

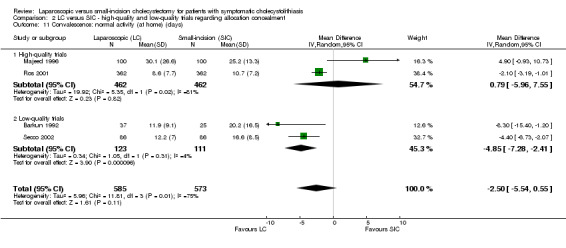

| convalescence activity | WMD | HQ | ‐1.87 (‐2.93, ‐0.80) * | 0.79 (‐5.96, 7.55) | yes | |||

| LQ | ‐4.78 (‐6.99, ‐2.57) * | ‐4.85 (‐7.28, ‐2.41) * | no | |||||

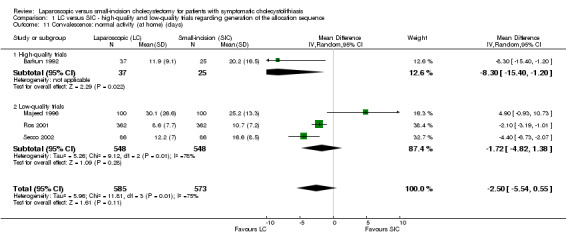

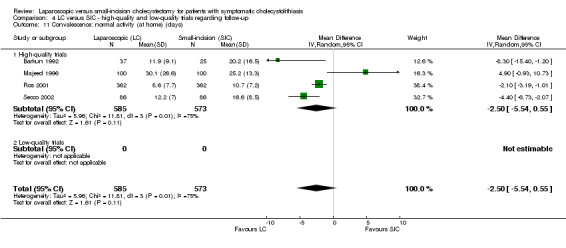

| AT | ‐2.42 (‐3.38, ‐1.45) * | ‐2.50 (‐5.54, 0.55) * | yes | random | yes | no | ||

| * significant result | HQ: high quality trials | LQ: low quality trials | AT: all trials |

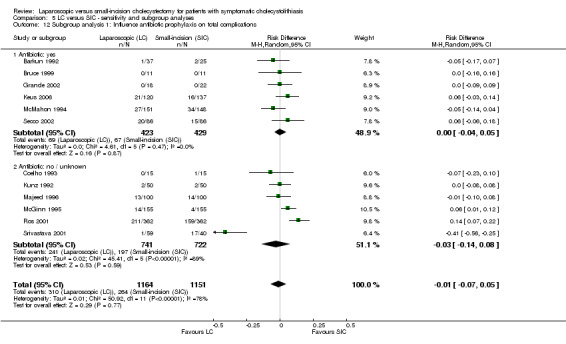

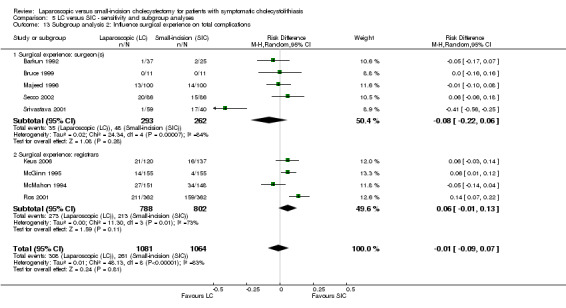

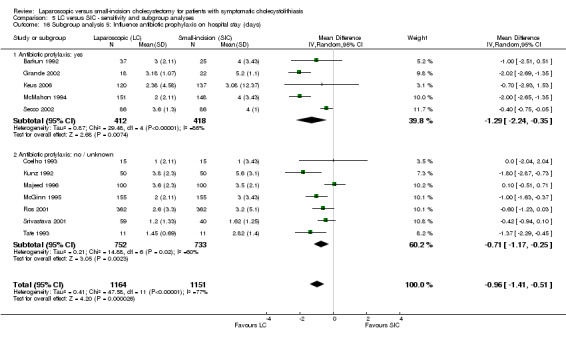

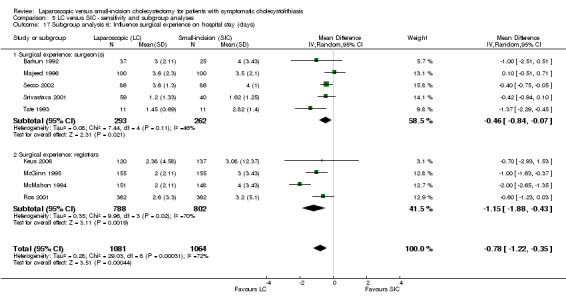

Sensitivity analyses were performed assuming zero mortality and zero conversions, imputing medians and standard deviations for missing data, omitting one outlier in complications and hospital stay, and adding results from the borderline trial of Redmond (Redmond 1994). Subgroup analyses were performed testing the influence of antibiotic prophylaxis, surgical experience and intra‐operative cholangiography on operative time, complications and hospital stay. Other sensitivity and subgroup analyses were not performed as necessary data were missing or analyses were considered inappropriate.

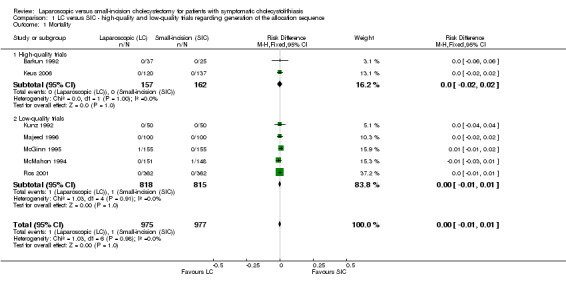

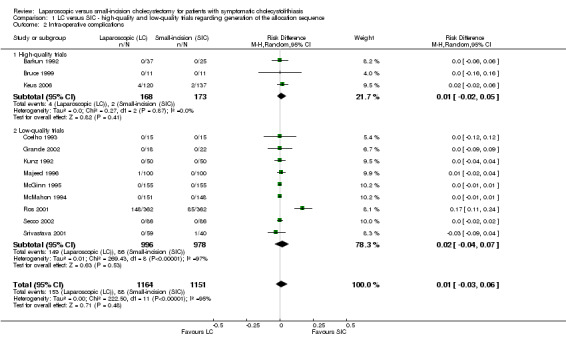

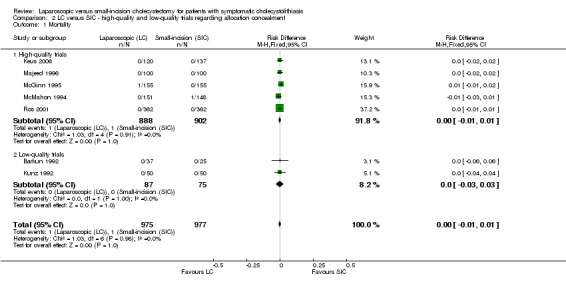

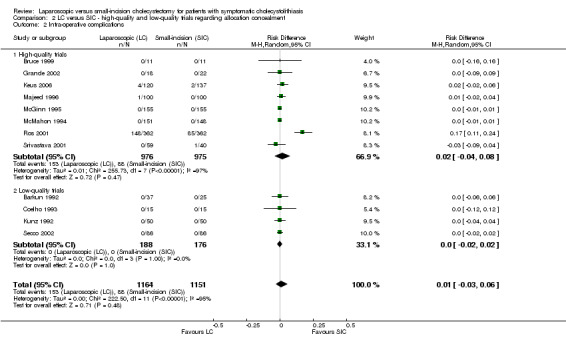

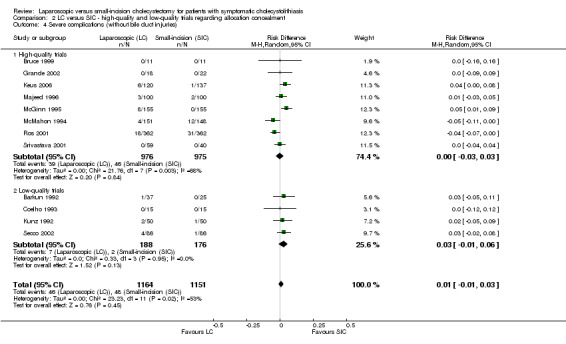

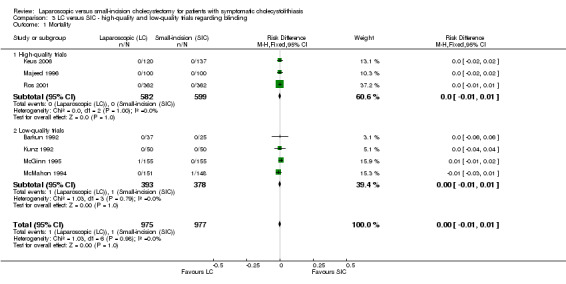

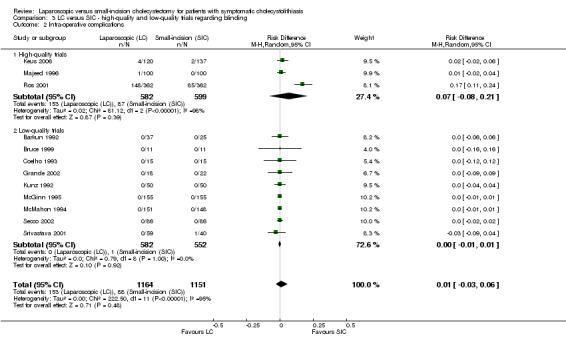

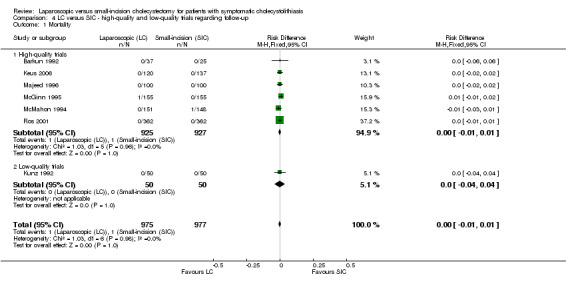

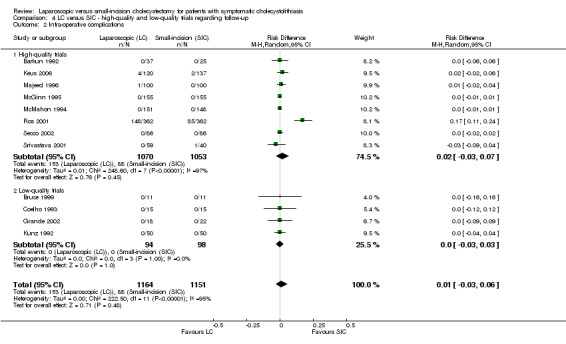

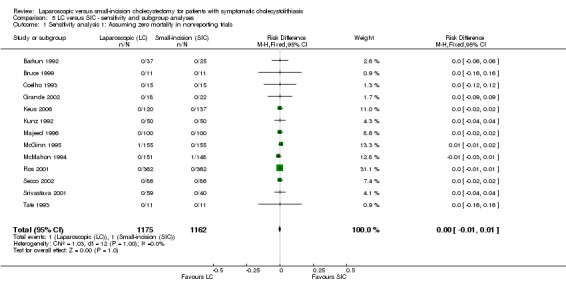

Mortality Mortality was only explicitly reported in seven trials. Mortality was not reported in six trials (Coelho 1992a; Tate 1993; Bruce 1999; Srivastava 2001; Grande 2002; Secco 2002). No significant differences were identified in analyses stratifying trials for all four quality components. There was no heterogeneity, therefore the fixed‐effect model has been applied. Sensitivity analysis (5‐1) assuming zero mortality in non‐reporting trials, led to the same result (risk difference 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.01). In both treatment groups one patient died (resulting in mortality proportions of 0.09% in both laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy). Intra‐operative complications Complications were explicitly reported in all but one trial. Intra‐operative complications were 13.1% and 7.6% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively. There was severe heterogeneity (up to 98%), therefore the random‐effects model has been applied resulting in no significant effects in all subgroups in all four comparisons (risk difference 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.06). The majority of the events were accounted for by the trial of Ros (Ros 2001) (most of the intra‐operative complications in this trial were gallbladder perforations).

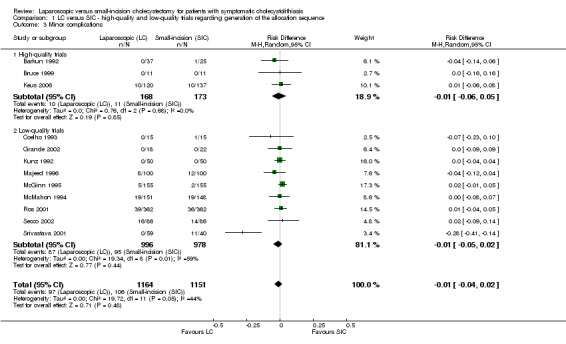

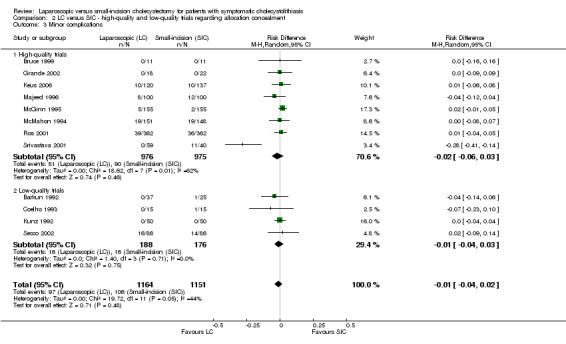

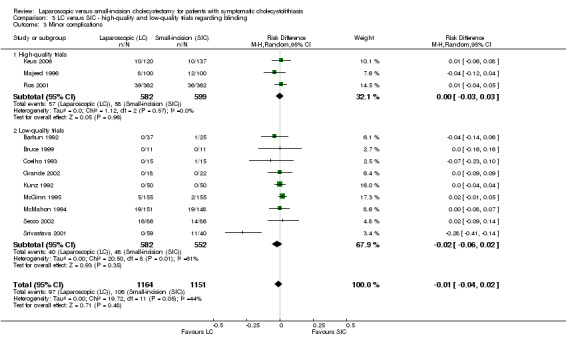

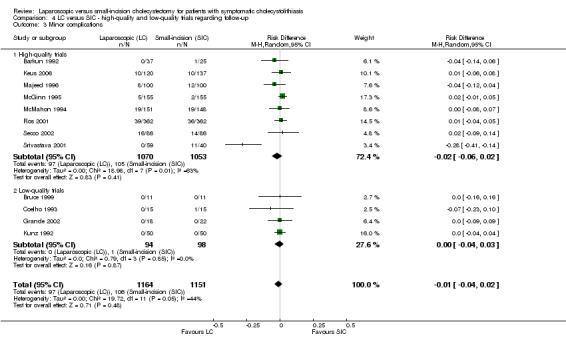

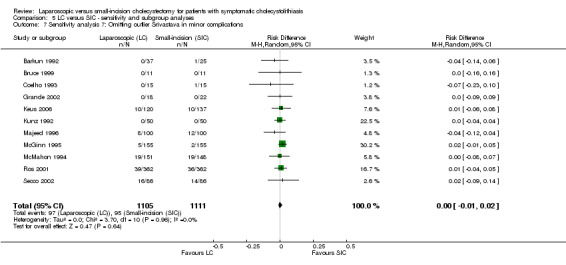

Minor complications The minor complication proportions were 8.3% and 9.2% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively. The random‐effects model has been applied and there were no significant differences present in the four quality components in the subgroups (risk difference all trials, random‐effects ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.02). Performing a sensitivity analysis (5‐7) by omitting the outlier (Srivastava 2001) led to disappearance of heterogeneity, but still showed no significant difference (risk difference, fixed‐effect 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.03).

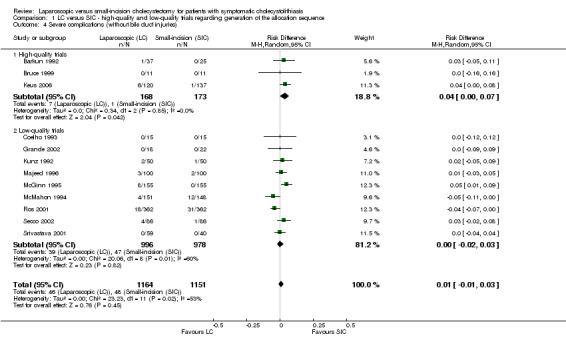

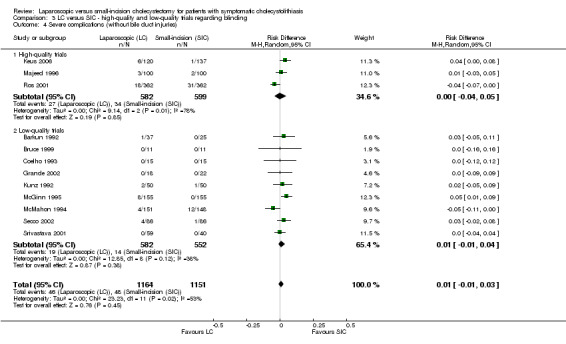

Severe complications The severe complication proportions were 4.0% and 4.2% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively. As heterogeneity was present (up to 78%), the random‐effects model has been applied. There were no significant differences in the four quality components present, neither in the high‐quality and in the low‐quality subgroups (risk difference all trials, random‐effects 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.03).

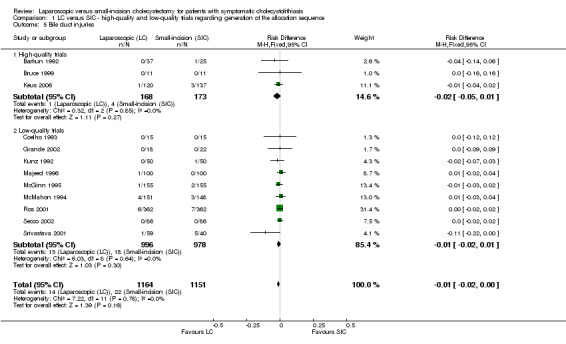

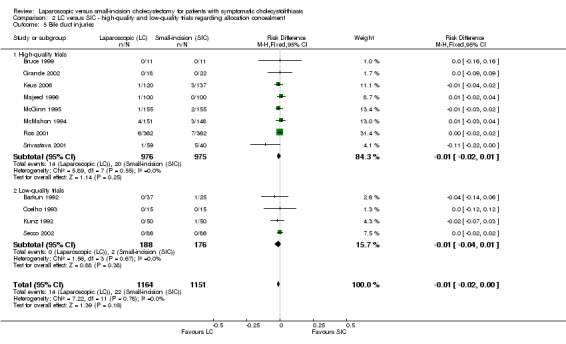

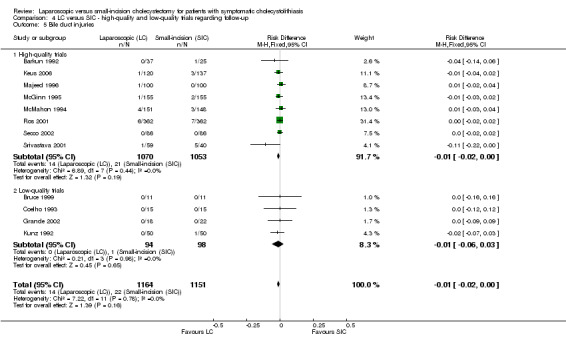

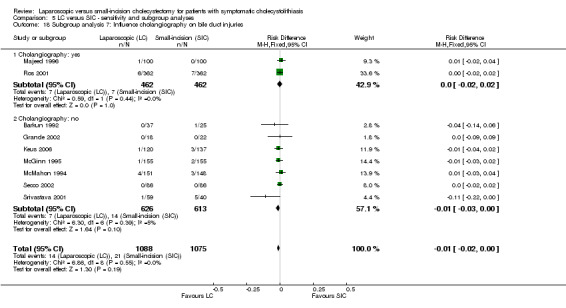

Bile duct injury The bile duct injury proportions were 1.2% and 1.9% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively. The difference was mainly caused by eight cases of bile leakage with unknown origin and conservative treatment in the small‐incision group (five cases from one trial). As no heterogeneity was present, the fixed‐effect model has been applied, and there were no significant differences present in all four quality components (risk difference all trials ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.00).

Comparing in a subgroup analysis (5‐18) the bile duct injuries from trials that explicitly mentioned they did attempt intra‐operative cholangiography in all patients versus the bile duct injuries from trials that explicitly mentioned they did not attempt routine intra‐operative cholangiography in all patients (but only in selected or no patients), did not show an influence of cholangiography on the bile duct injury proportion (regression coefficient 0.452, 95% CI ‐1.003 to 1.907, P = 0.54).

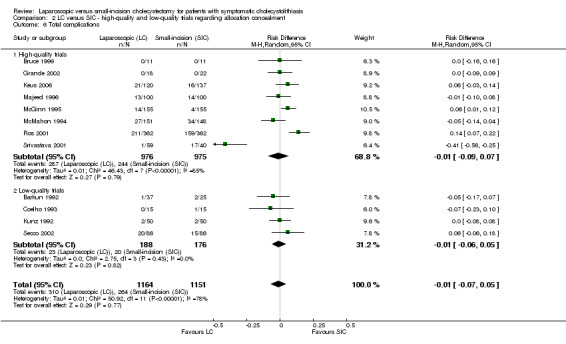

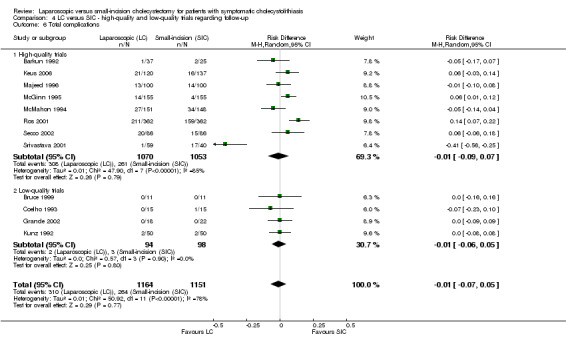

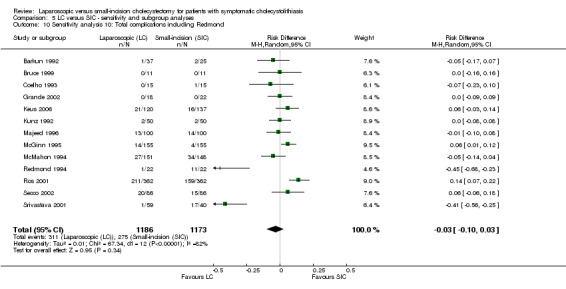

Total complications Complications were not reported in one trial (Tate 1993). All complications (and frequencies) were listed (Table 3).

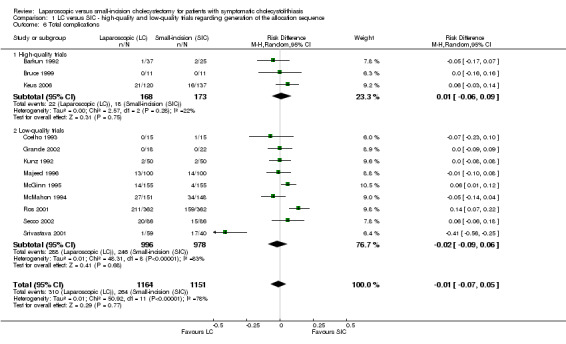

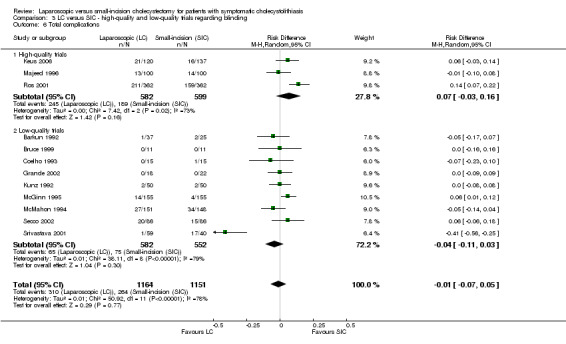

The total complication proportions were 26.6% and 22.9% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group respectively (Table 3). There were 19 re‐operations in the laparoscopic group and 18 in the small‐incision group. Reoperation proportions were 1.6% in both groups. Because of heterogeneity the random‐effects model has been applied and no significant difference was present (risk difference all trials ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.05). Also in the low‐quality and high‐quality subgroups there were no significant differences present applying the random‐effects model.

Complications in trials with three or more quality components assessed as high‐quality (Majeed 1996; Ros 2001; Keus 2006) were summarised and presented in additional Table 6. Complication proportions in both treatment groups were comparable, but overall complication proportions were higher compared to complications in additional Table 3 including all trials.

6. Complications specified per operative technique: LC vs SIC: high‐quality trials.

| Complications | LC | SIC |

| INTRA‐OPERATIVE | (153 / 26.3%) | (87 / 14.5%) |

| gallbladder perforation | 112 | 62 |

| bleeding | 23 | 19 |

| stone left in abdomen | 10 | 0 |

| vascular injury (hepatic artery) | 0 | 1 |

| bowel injury | 5 | 3 |

| hepatic injury | 1 | 1 |

| cardiac | 1 | 1 |

| cerebrovascular | 1 | 0 |

| POSTOPERATIVE ‐ MINOR | (57 / 9.8%) | (58 / 9.7%) |

| thrombo‐embolic event | 0 | 1 |

| retained bile duct stone (ERCP) | 0 | 1 |

| wound infection | 21 | 25 |

| wound hematoma | 2 | 0 |

| urinary retention | 6 | 11 |

| urinary tract infection | 5 | 9 |

| flebitis | 3 | 0 |

| other | 20 | 11 |

| POSTOPERATIVE ‐ SEVERE | (27 / 4.6%) | (34 / 5.7%) |

| bleeding: drainage / blood transfusion | 3 | 2 |

| bleeding: re‐operation | 4 | 4 |

| pancreatitis | 3 | 6 |

| abscess (drainage / unspecified) | 1 | 4 |

| abscess (re‐operation) | 1 | 0 |

| pneumonia | 12 | 12 |

| cardiovascular | 1 | 5 |

| cerebrovascular accident | 1 | 1 |

| epididymitis (re‐operation) | 1 | 0 |

| BILE DUCT INJURY | (8 / 1.4%) | (10 / 1.7%) |

| cystic duct leakage: drainage/ERCP | 1 | 1 |

| cystic duct leakage: re‐operation | 0 | 3 |

| accessory duct leakage (re‐operation) | 0 | 1 |

| common bile duct injury (intra‐operative) | 5 | 1 |

| major common bile duct injury: re‐operation | 2 | 1 |

| hepatic duct injury (intra‐operative) | 0 | 1 |

| bile leakage (origin unknown): re‐operation | 0 | 2 |

| TOTAL COMPLICATIONS | 245 (42.1%) | 189 (31.6%) |

| RE‐OPERATIONS (all complications) | 10 (1.7%) | 12 (2.0%) |

| TOTAL NUMBER OF PATIENTS INCLUDED | 582 | 599 |

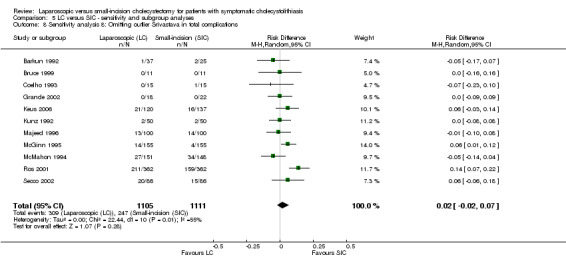

Performing a sensitivity analysis (5‐8) by omitting the outlier (Srivastava 2001) led to a reduction of heterogeneity (but it was still present: 55%) and also showed no significant difference in the random‐effects model (risk difference 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.07).

As the study of Redmond was considered a borderline case, the complications of this study were included in a sensitivity analysis (5‐10). There was no significant difference present between both groups including this study.

Comparing the total complication proportions from trials that explicitly mentioned the use of antibiotic prophylaxis versus the total complication proportions from trials that explicitly mentioned that they did not use antibiotic prophylaxis or trials that did not mention the use of antibiotic prophylaxis, did not show a significant influence of antibiotic prophylaxis in a subgroup analysis (5‐12) (regression coefficient ‐0.220, 95% CI ‐0.557 to 0.118, P = 0.20).

Comparing in a subgroup analysis (5‐13) the total complication proportions from trials that explicitly mentioned that one or a few experienced surgeons performed all the operations versus the total complication proportions from trials that explicitly mentioned that also registrars performed the operations, did not show an influence of surgical experience (regression coefficient ‐0.327, 95% CI ‐0.784 to 0.129, P = 0.16).

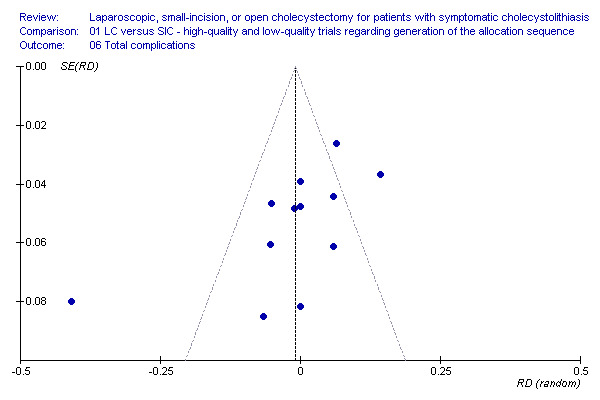

Funnel plot of total complications is shown in Figure 3, showing no bias.

3.

Funnel plot on laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy regarding generation of the allocation sequence considering total complications, including 95% confidence interval lines. There is some suspicion of bias considering the absence (in the lower right part of the figure) of small trials favoring the small‐incision technique.

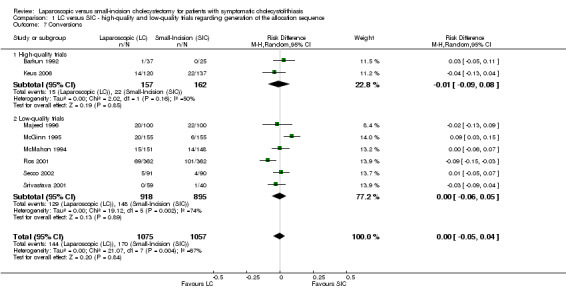

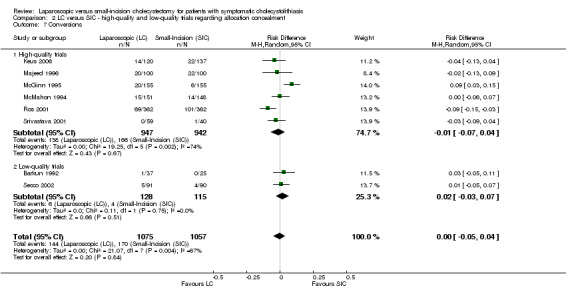

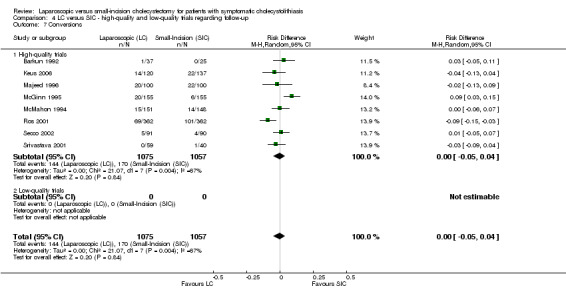

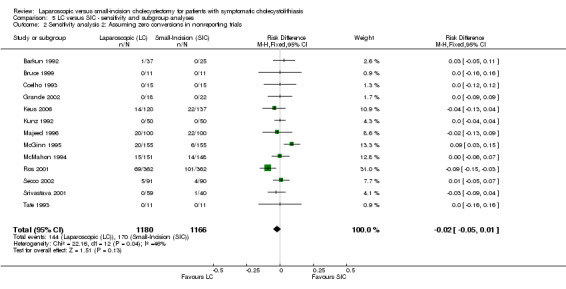

Conversion Conversions were not reported in five trials (Coelho 1992a; Kunz 1992; Tate 1993; Bruce 1999; Grande 2002). The conversion proportions were 13.4% and 16.1% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively. As heterogeneity was present, the random‐effects model has been applied. All comparisons did not show significant differences in conversion proportions, neither in the low‐quality nor in the high‐quality subgroups (risk difference all trials, random‐effects 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.04). Analysis of conversions in the 'blinding' comparison were not performed, as the decision to convert (or not to convert) could not have been made under blinded conditions.

In a sensitivity analysis the assumption was made that trials that did not mention converted operations had zero conversions. Results showed no significant difference (5‐2). Including these trials resulted in overall conversion proportions of 12.2% and 14.8% respectively. This difference was not significant (risk difference ‐0.02, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.01).

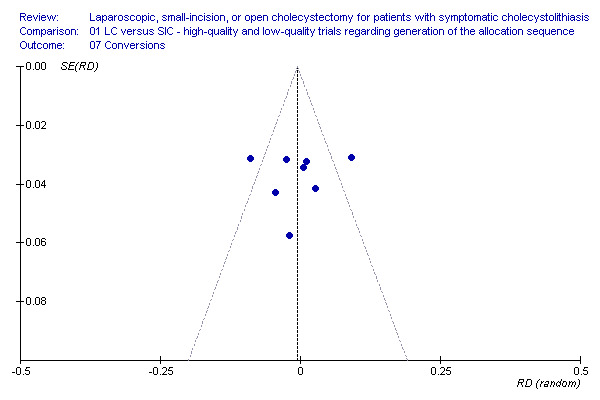

Funnel plot of conversions is shown in Figure 4, showing no bias.

4.

Funnel plot on laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy regarding generation of the allocation sequence considering conversions, including 95% confidence interval lines. No arguments for bias.

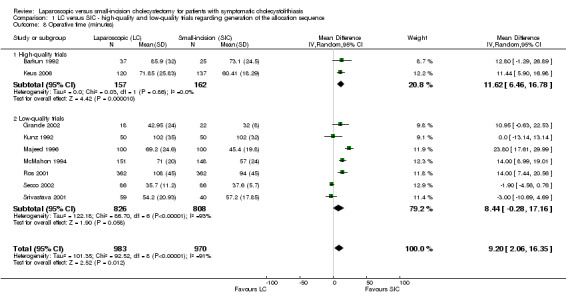

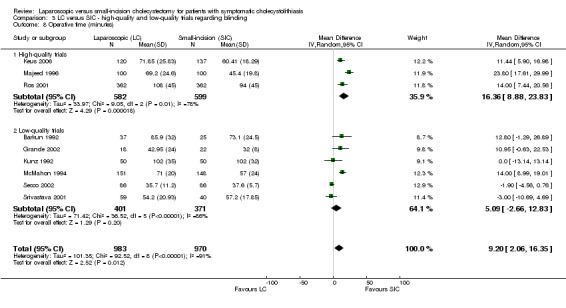

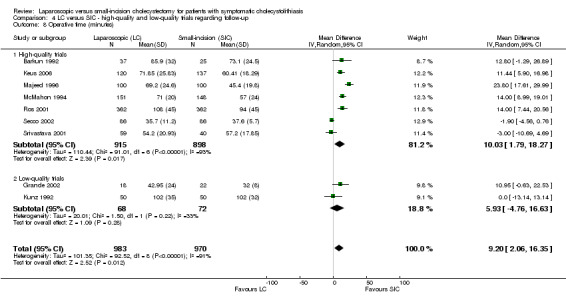

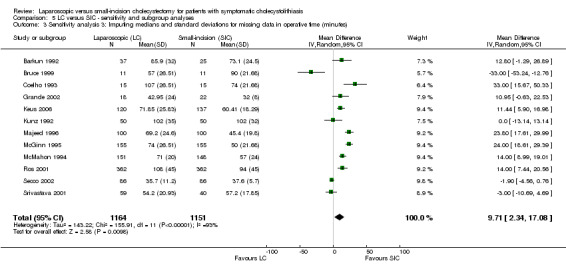

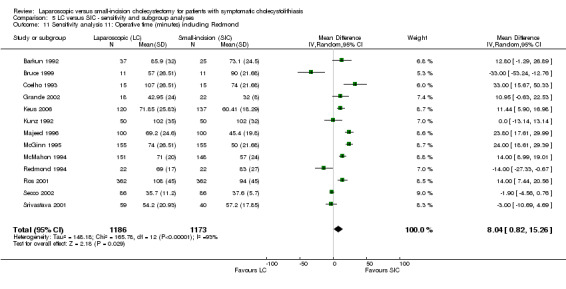

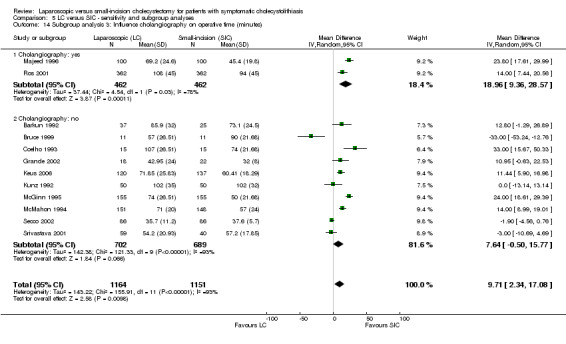

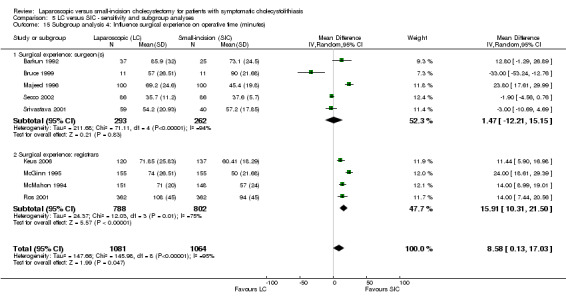

Operative time Because of heterogeneity, the random‐effects model was applied. Meta‐analyses in all comparisons showed that small‐incision cholecystectomy was significantly faster to perform than laparoscopic cholecystectomy ((WMD all trials, random‐effects 9.20 minutes, 95% CI 2.06 to 16.35); high‐quality trials ranging from 10.03 minutes to 16.36 minutes). Low‐quality subgroups showed no significant difference.

All available data were presented in Table 7. In a sensitivity analysis (5‐3) including the assumptions on standard deviations and medians considering skewness, there was a significant shorter operative time in the small‐incision group (WMD, random‐effects 9.71 minutes, 95% CI 2.34 to 17.08). As the study of Redmond was considered a borderline case, the results of operative times of this study were included in a sensitivity analysis (5‐11). The previous findings of a shorter operative time in the small‐incision group did not change.

7. Operative time LC versus SIC: all available data.

| Trial | Type of data | LC ‐ mean/median | LC ‐ SD/range | SIC ‐ mean/median | SIC ‐ SD/range | Skewness LC | Skewness SIC |

| Barkun 1992 | A ‐ SD | 85.9 | 32 | 73.1 | 24.5 | 2.68 | 2.98 |

| Bruce 1999 | M ‐ IQR | 57 | 50 ‐ 90 | 90 | 62 ‐ 99 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Coelho 1993 | A ‐ range | 107 | 55 ‐ 150 | 74 | 40 ‐ 125 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Grande 2002 | A ‐ SD | 42.95 | 24 | 32.00 | 8.0 | 1.79 | 4.00 |

| Keus 2006 | A ‐ SD | 71.85 | 25.83 | 60.41 | 18.29 | 2.78 | 3.30 |

| Kunz 1992 | A ‐ SD | 102 | 35 | 102 | 32 | 2.91 | 3.19 |

| Majeed 1996 | A ‐ SD | 69.2 | 24.6 | 45.4 | 19.8 | 2.81 | 2.29 |

| McGinn 1995 | M ‐ range | 74 | 45 ‐ 150 | 50 | 35 ‐ 150 | ||

| McMahon 1994 | A ‐ SD | 71 | 20 | 57 | 24 | 3.55 | 2.38 |

| Ros 2001 | A ‐ SD | 108 | 45 | 94 | 45 | 2.40 | 2.09 |

| Secco 2002 | A ‐ SD | 35.7 | 11.2 | 37.6 | 5.7 | 3.19 | 6.60 |

| Srivastava 2001 | A ‐ CI * | 54.2 | 48.7 ‐ 59.6 (20.93)* | 57.2 | 51.5 ‐ 62.9 (17.85)* | 2.59 | 3.20 |

| Tate 1993 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| A: average / mean | M: median | SD: standard deviation | CI: confidence interval | IQR: interquartile range | |||

| * SD calculated from CI |

Comparing in a subgroup analysis (5‐14) the operative time from trials that explicitly mentioned they did attempt intra‐operative cholangiography in all patients versus the operative time from trials that explicitly mentioned they did not attempt routine intra‐operative cholangiography in all patients (but only in selected or no patients) (and also including the assumptions on standard deviations and medians) did not show an influence of cholangiography on operative time (regression coefficient 11.381, 95% CI ‐9.645 to 32.407, P = 0.29). Comparing in a subgroup analysis (5‐15) the operative time from trials that explicitly mentioned that one or a few experienced surgeons performed all the operations versus the operative time from trials that explicitly mentioned that also registrars performed the operations (and also including the assumptions on standard deviations and medians) did not show an influence of surgical experience on operative time (regression coefficient ‐14.151, 95% CI ‐32.364 to 4.063, P = 0.13).

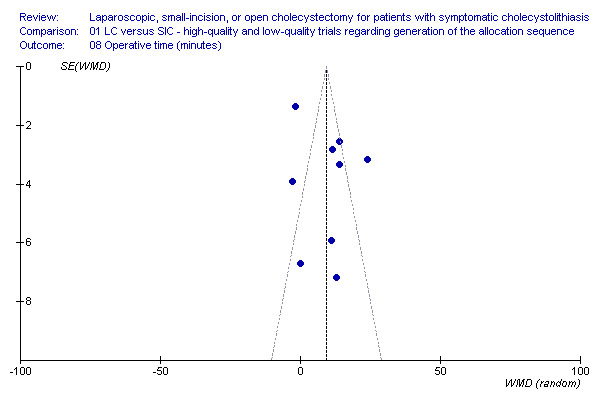

Funnel plot of conversions is shown in Figure 5, showing no bias.

5.

Funnel plot on laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy regarding generation of the allocation sequence considering operative time, including 95% confidence interval lines. No arguments for bias.

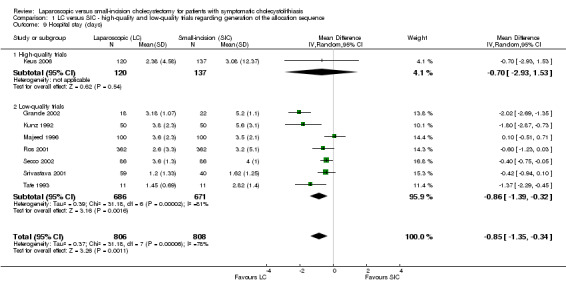

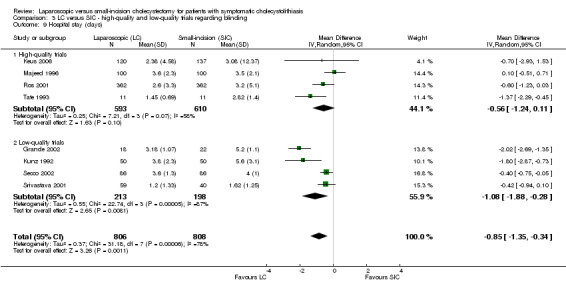

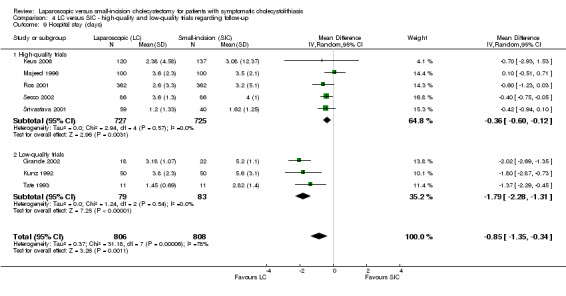

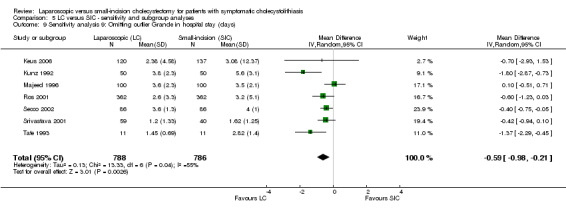

Hospital stay Heterogeneity was present (up to 87%), therefore the random‐effects model has been applied resulting in significant differences analysing all trials and in the low‐quality trials subgroups (WMD, random‐effects ‐0.85, 95% CI ‐1.35 to ‐0.34). However, there were no significances in the high‐quality trials subgroups (except for the high‐quality trials regarding adequate follow‐up). As high‐quality trials results are more reliable, a real difference is probably not present.

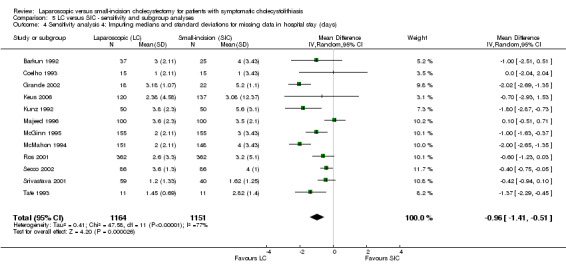

All available data were presented in Table 8. In a sensitivity analysis (5‐4) we made assumptions on standard deviations and medians considering skewness. However, the second assumption did not hold: skewness was suggested in two trials (Kunz 1992; Majeed 1996), and there was evidence of skewness in three trials (Ros 2001; Srivastava 2001; Keus 2006). Including these assumptions on all trials (ignoring skewness), again a significant shorter hospital stay was suggested in the laparoscopic group (WMD, random‐effects ‐0.96 days, 95% CI ‐1.41 to ‐0.51). Excluding the trials with evidenced skewness (as these are likely to introduce severe bias) also suggested a shorter hospital stay in the laparoscopic group (WMD, random‐effects ‐1.10 days, 95% CI ‐1.68 to ‐0.51).

8. Hospital stay LC versus SIC: all available data.

| Trial | Type of data | LC ‐ mean/median | LC ‐ SD/range | SIC ‐ mean/median | SIC ‐ SD/range | Skewness LC | Skewness SIC |

| Barkun 1992 | M ‐ range | 3 | 1 ‐ 13 | 4 | 1 ‐ 6 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bruce 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Coelho 1993 | A ‐ range | 1 | 1 ‐ 1 | 1 | 1 ‐ 1 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Grande 2002 | A ‐ SD | 3.18 | 1.07 | 5.2 | 1.1 | 2.97 | 4.73 |

| Keus 2006 | A ‐ SD | 2.38 | 4.58 | 3.08 | 12.37 | 0.52 | 0.25 |

| Kunz 1992 | A ‐ SD | 3.8 | 2.3 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 1.65 | 1.81 |

| Majeed 1996 | A ‐ SD | 3.6 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 2.1 | 1.57 | 1.67 |

| McGinn 1995 | M ‐ range | 2 | 0 ‐ 7 | 3 | 1 ‐ 8 | ‐ | ‐ |

| McMahon 1994 | M ‐ | 2 | ‐ | 4 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Ros 2001 | A ‐ SD | 2.6 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 5.1 | 0.79 | 0.63 |

| Secco 2002 | A ‐ SD | 3.6 | 1.3 | 4 | 1.0 | 2.77 | 4.00 |

| Srivastava 2001 | A ‐ CI | 1.2 | 0.9 ‐ 1.6 (1.33)* | 1.62 | 1.19 ‐ 2.0 (1.25)* | 0.90 | 1.30 |

| Tate 1993 | A ‐ SD | 1.45 | 0.69 | 2.82 | 1.4 | 2.10 | 2.01 |

| * SD calculated from CI | A: Average / mean | SD: standard deviation | M: median | CI: confidence interval |

Performing a sensitivity analysis (5‐9) by omitting the outlier (Grande 2002) and including the previous mentioned assumptions showed a significant difference in the random‐effects model (WMD, random‐effects ‐0.59 days, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.21).

Comparing in a subgroup analysis (5‐16) hospital stay from trials that explicitly mentioned that they did use antibiotic prophylaxis versus the hospital stay from trials that explicitly mentioned that they did not use antibiotic prophylaxis (and also including the assumptions on standard deviations and medians) did not show an influence of antibiotic prophylaxis on hospital stay (regression coefficient ‐0.573, 95% CI ‐1.457 to 0.312, P = 0.21). There was also no influence of surgical experience on hospital stay (5‐17) (regression coefficient 0.665, 95% CI ‐0.131 to 1.460, P = 0.11).

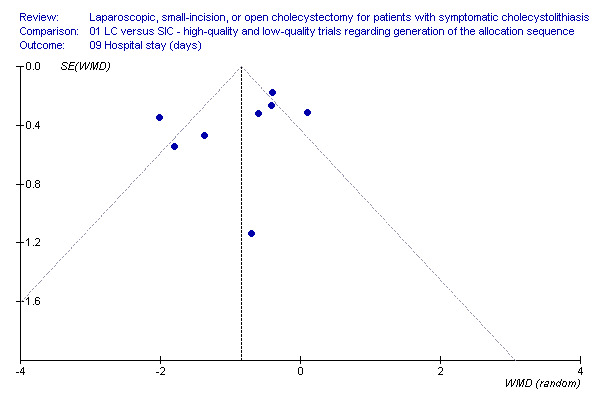

Funnel plot of conversions is shown in Figure 6, showing no bias.

6.

Funnel plot on laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy regarding generation of the allocation sequence considering hospital stay, including 95% confidence interval lines. No arguments for bias.

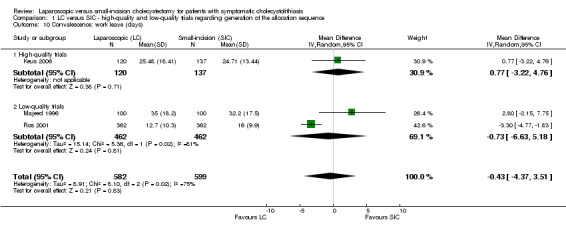

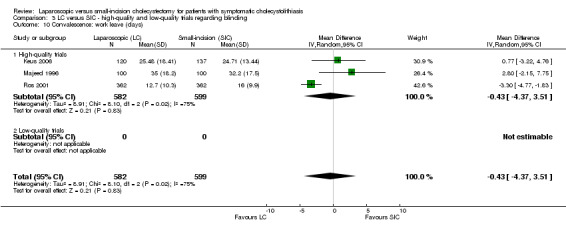

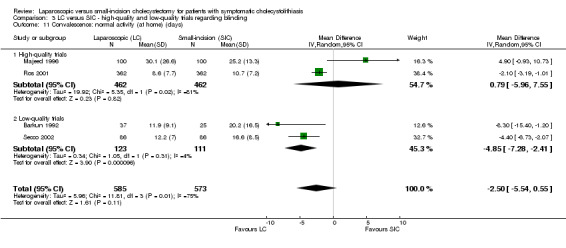

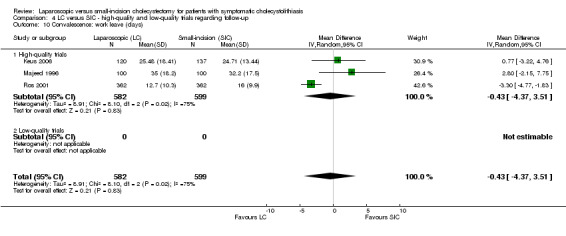

Convalescence Unfortunately convalescence was not always reported and making the distinction between return to work and to normal activity (at home) was difficult. As these can be regarded separately, we made different comparisons.

Convalescence from work leave Due to heterogeneity, the random‐effects model has been applied resulting in no significant difference between both techniques considering work leave. However, only three trials described return to work.

Convalescence to normal activity There is heterogeneity present, therefore the random‐effects model has been applied. Analysis of all trials showed no significant difference. Although, the low‐quality trials subgroups showed significant differences in two of the four methodological quality components ('concealment of allocation' and 'blinding') favouring the laparoscopic technique, the high‐quality trials subgroups on contrary, did not show significant differences in the four comparisons. Conclusions must be drawn carefully as only four trials are involved.

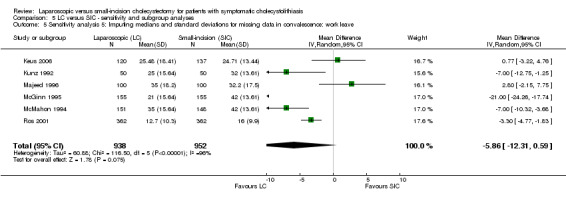

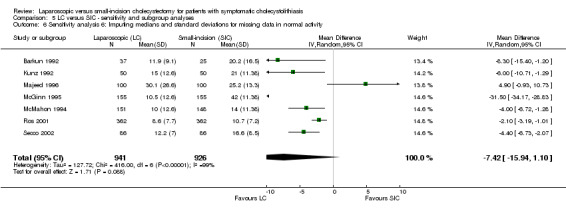

Assuming in a sensitivity analysis that convalescence (both considering work leave (5‐5) and normal activity (5‐6)) is symmetrically distributed and therefore making assumptions on standard deviations and medians, there were neither significant differences in convalescence on work leave (WMD, random‐effects ‐5.86, 95% CI ‐12.31 to 0.59) nor in convalescence on normal activity (WMD, random‐effects ‐7.42, 95% CI ‐15.94 to 1.10).

Discussion

This systematic review contains at least four major findings. First, the comparison of the clinical outcome of laparoscopic cholecystectomy to small‐incision cholecystectomy has been well tested in randomised clinical trials with over 2300 patients randomised to the two techniques in trials of relatively high methodological quality. Secondly, laparoscopic cholecystectomy carried a bile duct injury rate not significantly different from small‐incision cholecystectomy. Thirdly, the total numbers of patients with complications were high and not significantly different for the two procedures. Fourthly, laparoscopic cholecystectomy took significantly more time to perform than small‐incision cholecystectomy.

No comparison could be performed dividing trials into low‐bias risk trials (trials with adequate methodological quality in all four quality criteria) versus high‐bias risk trials, suggesting that surgical research considering cholecystectomy can be improved importantly.

High‐quality trials are more likely to estimate the 'true' effects of the interventions (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Jüni 2001; Kjaergard 2001; Egger 2003). In this review high‐quality trials were more likely to show a neutral effect or a negative effect of laparoscopic surgery, whereas trials with unclear or inadequate quality tended to show more often a positive effect or a neutral effect of laparoscopic surgery. These observations are in concordance with other studies showing linkage between unclear/inadequate methodological quality to significant overestimation of beneficial effects and underreporting of adverse effects. The small trials favoring laparoscopic surgery can be regarded as an example of either low methodological quality or publication bias (illustrated in funnel plot: Figure 3 laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy considering total complications). The other funnel plots (Figure 4; Figure 5; and Figure 6) do not suggest bias.

We identified a total of 13 trials comparing laparoscopic versus small‐incision cholecystectomy with different focuses on outcome measures. Mortality in both procedures was near 0% in this systematic review, which is in concordance with the literature including non‐randomised series (Downs 1996). The total complication proportions are 26.6% and 22.9% in the laparoscopic and small‐incision group, respectively (Table 3). Excluding gallbladder perforation (as some surgeons would not regard it being a complication) results in complication proportions decreasing to 17.0% and 17.5%, respectively. These percentages are higher than figures (up to 5% overall complication proportions) known from other series and reviews including non‐randomised series, suggesting underreporting of these observational studies (Southern Surg 1991; Litwin 1992; Deveney 1993; Deziel 1993; Deziel 1994; Wherry 1994; Downs 1996). The situation in the real world, however, may be even worse due to the positive effect that randomised clinical trials may have on quality of care.

All four methodological quality subgroup analyses showed no significant difference considering intra‐operative and total complication proportions. In subgroup analysis of complications, surgical experience, the use of antibiotic prophylaxis, or performing an intra‐operative cholangiography revealed no significant difference (in regression coefficients; STATA®) for both groups. There is also no significant difference in conversion proportions. This is in line with the results from our sensitivity analysis, including all trials in the model.

Operative time was shorter in small‐incision cholecystectomy considering all four methodological subgroup analyses and despite heterogeneity, both in the high‐quality trials and all trials subgroups, while the low‐quality trials subgroups in all four component analyses do not show this difference. This is one of the many illustrations that inadequate quality trials tend to show a more favourable effect of the laparoscopic technique, while high‐quality trials show more often a positive effect of the small‐incision technique. In our sensitivity analysis we make assumptions on values for missing data (calculating average standard deviations and using medians in absence of skewness). Based on fulfillment of the condition of exclusion of the presence of skewness (Table 7; Table 8), means are supplemented by medians and averaged standard deviations are calculated, in order to pool estimates. In the subsequent sensitivity analysis with these adjustments, again a shorter operative time for the small‐incision group was found. As imputing data is dangerous, these results have to be interpreted with care.

Regarding hospital stay, the high‐quality trials showed no significant difference between the two operations with the random‐effects model, while low‐quality trials as well as all trials together do show a significant difference between the two operations with the random‐effects model. As methodological high‐quality trials produce more reliable results, we conclude that there is no significant difference in hospital stay. In our sensitivity analysis on hospital stay we make the same assumptions on average standard deviations and using medians for means. Our sensitivity analysis suggests that the duration of hospital stay in the laparoscopic group was shorter. However, skewed data are included in the analysis. Remembering that in general including skewed data are expected to falsely increase differences, combined with the fact that it is a post‐hoc hypothesis generating analysis, makes that the conclusion that hospital stay is shorter after laparoscopic cholecystectomy most uncertain. In subgroup analyses no evidence was found of antibiotic prophylaxis or surgical experience influencing hospital stay.

One might find hospital stay long compared to daily life practice. Probably study conditions and different practice over time are responsible for a longer hospital stay compared to current daily life practice. Apart from these reasons, there might be other reasons including cultural differences and others for differences in hospital stay. However, we have to remember that hospital stay is a surrogate marker for convalescence and because of numerous factors influencing its length it does not necessary reflect objective differences between two operative procedures. Differences in hospital stay in open studies may represent bias, unless the type of surgery is blinded. Differences in results have to be interpreted with care.

Considering convalescence we tried to make distinction between work leave and return to normal activity (at home). Unfortunately only three trials reported data in each category. However, it seems that there is no significant difference between both groups in convalescence in work leave, while return to normal activity seems quicker in the laparoscopic group. It must be emphasized however, that these conclusions are only based on the results of three trials. In our sensitivity analysis on convalescence considering normal activity we make assumptions on standard deviation values in three more trials. Due to heterogeneity we are forced to apply the random‐effects model resulting in a non‐significant pooled estimate. These findings emphasize to be careful with conclusions based on a small number of trials.

Considering methodological quality on generation of allocation sequence, concealment of allocation, blinding and follow‐up, there were 3, 8, 4, and 8 trials, respectively, rated as high‐quality trial. This can be regarded as a reasonable number of high‐quality trials in a total of 13 trials selected. A substantial part of the trials include an extensive description of their methods. Moreover 6 trials are described in multiple papers reporting different aspects. Remarkably, three randomised clinical trials, published in top indexed journals, scored only one or two methodology aspects as high‐quality (Barkun 1992; McMahon 1994; McGinn 1995).

Surgical experience is a potential effect modifier and needs consideration. Six trials reported the operations being done by one or two expert surgeons. Four trials explicitly mentioned that registrars were involved in performing the operations. Therefore, this influence was tested in a number of subgroup analyses. It appeared to have no influence. The combination of the relative high number of high‐quality trials, the substantial number of trials involving registrars and the lack of evidence from the subgroup analyses on surgical experience makes us to believe that surgical experience carries a low risk of bias.

We decided not to report on costs because of numerous reasons: costs were reported in a lot of different ways making pooling results impossible; different points of view were taken in the analyses leading to comparing apples and pears; cultural differences influencing convalescence are present when comparing trials from all over the world; differences in local costs are impossible to make corrections for. We decided that reporting this outcome would not be meaningful. We realise however that this (secondary) outcome probably is the most important aspect in an evidence‐based decision which procedure to prefer for cholecystectomy.

The next issue in applicability is the question whether selection for randomised trials introduces bias so that participation is associated with greater risks and that outcomes are worse than expected in daily life practice. In this issue different outcomes caused by a different (better or worse) treatment has to be distinguished from a better recording of outcomes. There is empirical evidence that participation in randomised trials does not lead to worse outcomes and that results are applicable to usual practice (Vist 2004), so there seems to be no difference in treatment. Though, one could believe that through a more careful follow‐up, outcomes are recorded better leading to more objective results.

Search strategy and data extraction Searches were performed in all databases of The Cochrane Library, and four other databases which we believed were most important (Appendix 1). The first selection, based on the title, and the second selection, based on the abstracts, both low‐threshold sensitive selections were performed by FK. The third phase was a selection based on full text articles. This selection, based on interpretation of inclusion criteria, was separately carried out by FK, JJ and CL. Inclusion of unclear articles was discussed by three co‐reviewers (see tables with Characteristics of included and excluded studies).

The quality (and value) of this review was tried to maximise by performing extreme low‐threshold sensitive searches, and performing a double full text selection. A triple internal validity score as well as a triple data extraction was performed by three co‐reviewers independently (FK, JJ and CL), by using separate Excel spreadsheets. Disagreements on interpretation were solved by discussion. A letter with a request for additional information was send twice to all authors.

Consistency of results Heterogeneity was observed in many comparisons in this systematic review. For instance there was a remarkable difference in reported complication proportions (eg, up to 40% in Ros 2001).

The following factors were identified as possible effect modifiers: the level of surgical experience, antibiotic use during operation, the use of an intra‐operative cholangiography, different local policies for planned hospital stay, cultural differences explaining convalescence (Vitale 1991) and medical insurance differences explaining convalescence and return to work. As local circumstances differ to a great extend, heterogeneity must be present by definition. For example surgical experience leads to great variations in operative time (illustrated by the between trials ranges in operative time) and homogeneity is absent by definition.

The following possible explanations were recognised as confounding factors: differences in length of follow‐up (and complication registration) and differences in effort and level of data registration (eg, micro‐atelectasis assessment by chest X‐ray analysis). Eventual occurrence of drop‐outs is mentioned in the characteristics of included studies table for each trial. Although some drop‐outs are mentioned in some trials, there is no skewness in drop‐outs between the two groups and they seem not to have major influences on the results. Background data are supposed to be equally distributed due to randomisation, but this is not always so and might as well contribute to bias (especially in studies in which the number of included patients are rather small). Data in Table 2 suggests no major inequality in distribution.

All these factors may introduce bias and cause heterogeneity. Comparisons with excessive heterogeneity, assessed by the Cochran´s Q test and quantified by the I2 test, were presented both by fixed‐effect and random‐effects models. Furthermore subgroup analyses on four methodological quality aspects were performed and presented if differences arose from them or whenever considered clinically relevant.

Although several bias introducing factors can be identified, we believe that the results from this systematic review with meta‐analysis are reliable. In our opinion, populations from individual trials are representative for the general surgical population; trials used general and comparable inclusion criteria. Moreover the methodological quality of the included randomised trials is relatively high making results even more reliable. Therefore, we believe that results of this analysis are applicable to the general surgical population.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy and small‐incision cholecystectomy should, based on clinical outcome measures, both be regarded as treatment of first choice for patients with symptomatic gallbladder stones. The only clear significant difference between both procedures was a shorter operative time using the small‐incision technique. Preferring one of both techniques does not seem justified so far for other reasons than personal experiences. Both surgical techniques are associated with high proportions of complications, ie, one in each five patients.

Implications for research.

The findings of high complication proportions in this comparison raise questions on the quality of the elective surgical laparoscopic and small‐incision cholecystectomy procedures. Whereas surgical technique and peri‐operative anaesthesia care must be considered to be the most determinant factors, improvement in these fields might improve quality and reduce complication proportions.

In order to come to a better recommendation of the procedure of first choice, cost analysis might afford valuable arguments for choosing the best and most valuable form of cholecystectomy. Research should focus on this.

Although the trials included in this systematic review had lower bias than trials included in comparable systematic reviews, a number of components need to be improved. Reports of trials ought to be improved by adopting the CONSORT statement while conducting and reporting trials (www.consort‐statement.org).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 20 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

Notes

The protocol for this systematic review was first published in Issue 3, 1997 of The Cochrane Library. The reviewers, Dr T Jørgensen and H Laugesen have abandoned the preparation of the systematic review. This necessitated that an update of the protocol and preparation of the review be performed by a new team of reviewers. They are F Keus, JAF de Jong, HG Gooszen, and CJHM van Laarhoven. Due to the large number of identified trials it was considered wiser in terms of clarity and usability to produce three separate reviews. Thus this review is one of the three.

Correction of name Eric Keus, the lead author of the protocol, and Frederik Keus, the lead author of the review, is one and the same person.

Acknowledgements

The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Review Group, Copenhagen, for excellent support; The Dutch Cochrane Centre, Amsterdam, for advice; The Library of the University Medical Center, Utrecht for cooperation in the search for full text articles; Geert van der Heijden (Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht) for advice in systematic searches; Ingeborg van der Tweel (Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center, Utrecht) for statistical advice; Laura Breuning, Jan Willem Elshof, and Yan Gong (Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Review Group, Copenhagen) for translations. We wish to thank all authors for their willingness to help in improving the review by responding to our request for additional information. Unfortunately, not all information we asked for was always useful for pooling into overall effect measures. The authors are: JS Barkun (unfortunately that the disk got lost in the mail), A Ros, and GB Secco.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Time span of search | Search strategy | Hits | Titles selected |

| The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register | 6 April 2004 | "cholelithiasis OR gallstones OR cholecystectomy" | 843 | 65 |

| The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews in The Cochrane Library | Issue 1, 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 33 | 0 |

| Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects in The Cochrane Library | Issue 1, 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 17 | 5 |

| The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library | Issue 1, 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 1343 | 146 |

| Health Technology Assessment Database in The Cochrane Library | Issue 1, 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 11 | 4 |

| NHS Economic Evaluation Database in The Cochrane Library | Issue 1, 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 43 | 6 |

| MEDLINE | 1966 to January 2004 | (((Gallbladder[Tiab] AND (Surgery[Tiab] OR Endoscopy[Tiab] OR Surgical[Tiab] OR Laparoscopy[Tiab])) OR Cholecystectomy[Tiab]) OR ((("Gallbladder"[MeSH] OR "Gallbladder Diseases"[MeSH]) AND ("Surgery"[MeSH] OR "surgery"[Subheading] OR "Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal"[MeSH] OR "Surgical Procedures, Operative"[MeSH] OR "Surgical Procedures, Minor"[MeSH] OR "Laparoscopy"[MeSH])) OR "Cholecystectomy"[MeSH])) AND (randomized controlled trial[PTYP] OR randomized controlled trials OR controlled clinical trial[PTYP] OR clinical trial[PTYP] OR clinical trials OR (clinical AND trial) OR random allocation OR random* OR double blind method OR single blind method OR (singl* OR doubl* OR trebl* OR tripl*) OR blind* OR mask* OR placebo* OR placebos OR research design OR comparative study OR evaluation studies OR follow up studies OR prospective studies OR control OR controlled OR prospectiv* OR volunteer*) | 8354 | 347 |

| EMBASE | 1980 to January 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 685 | 131 |

| Web of Science | 1988 to January 2004 | TS=(cholecystectomy AND random*) | 1163 | 148 |

| CINAHL | 1982 to January 2004 | "cholecystectomy" | 740 | 9 |

| Total | 13232 | 586 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. LC versus SIC ‐ high‐quality and low‐quality trials regarding generation of the allocation sequence.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |