ABSTRACT

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) comprises an important diarrheagenic pathotype, while uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) is the most important agent of urinary tract infection (UTI). Recently, EAEC virulence factors have been detected in E. coli strains causing UTI, showing the importance of these hybrid-pathogenic strains. Previously, we detected an E. coli strain isolated from UTI (UPEC-46) presenting characteristics of EAEC, e.g., the aggregative adherence (AA) pattern and EAEC-associated genes (aatA, aap, and pet). In this current study, we analyzed the whole genomic sequence of UPEC-46 and characterized some phenotypic traits. The AA phenotype was observed in cell lineages of urinary and intestinal origin. The production of curli, cellulose, bacteriocins, and Pet toxin was detected. Additionally, UPEC-46 was not capable of forming biofilm using different culture media and human urine. The genome sequence analysis showed that this strain belongs to serotype O166:H12, ST10, and phylogroup A, harbors the tet, aadA, and dfrA/sul resistance genes, and is phylogenetically more related to EAEC strains isolated from human feces. UPEC-46 harbors three plasmids. Plasmid p46-1 (~135 kb) carries some EAEC marker genes and those encoding the aggregate-forming pili (AFP) and its regulator (afpR). A mutation in afpA (encoding the AFP major pilin) led to the loss of pilin production and assembly, and notably, a strongly reduced adhesion to epithelial cells. In summary, the genetic background and phenotypic traits analyzed suggest that UPEC-46 is a hybrid strain (UPEC/EAEC) and highlights the importance of AFP adhesin in the adherence to colorectal and bladder cell lines.

KEYWORDS: UTI, UPEC, EAEC, hybrid-pathogenic E. coli, aggregate-forming pilus

Introduction

Escherichia coli is a highly versatile Gram-negative microorganism that colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of humans and various animal species. E. coli usually comprises an important commensal bacterial of the normal intestinal microbiota. However, according to their set of virulence factors and clinical properties, E. coli strains can be classified as diarrheagenic E. coli, also designated intestinal pathogenic E. coli (IPEC), which are capable of causing diarrhea; and extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), which cause extraintestinal infections, i.e., urinary tract infection (UTI), sepsis and meningitis [1–3].

Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) represents an important pathotype that belongs to the IPEC group, which is responsible for cases of acute and persistent diarrheal illness in developing countries and cases of travelers´ diarrhea [4–7]. EAEC strains are identified by the production of the aggregative adherence (AA) on cultured epithelial cells, which is characterized by adhered bacteria on the surface of epithelial cells and the coverslip between cells in an arrangement resembling stacked bricks [8,9]. Several virulence factors were identified in the prototypical EAEC 042 strain, which caused diarrhea in volunteers [10]. Among these virulence factors are fimbriae and secreted proteins, such as the aggregative adherence fimbriae (AAF), the anti-aggregation protein (dispersin), the plasmid-encoded toxin (Pet), the protein involved in colonization (Pic), and a pathogenicity island encoding a type 6 secretion system (T6SS) [11–19]. Some of these factors are under the regulation of AggR, an AraC transcriptional activator [20,21].

UTIs are among the most prevalent extraintestinal infections in humans worldwide [22]. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) represent the leading cause of community-acquired UTIs (about 70–90%). UPEC infections are highly prevalent in women, children, the elderly, and immunocompromised patients [23,24]. UPEC strains comprehend a heterogeneous pathotype with a wide range of virulence factors that can be combined into different genotypes. Although the isolation source (UTI) implies pathogenicity on epidemiological grounds, different virulence markers have been reported to differentiate UPEC strains from commensal and IPEC strains [25–27]. In addition, these virulence genes play an essential role in ascending UTI promoting the colonization of the bladder and kidney, which can lead to a bloodstream infection, known as urosepsis [22].

In the last years, EAEC has emerged as a causative agent of extraintestinal infections [28–36]. Some studies have described EAEC-associated characteristics, such as the AA pattern on epithelial cells and/or the presence of EAEC-associated genes in collections of E. coli strains causing UTI [31,33–37], suggesting that some EAEC strains might have uropathogenic potential. Accordingly, a multiresistant clonal EAEC strain (serotype O78:H10) was associated with an outbreak of UTI in a cluster of 18 patients in Denmark [38,39].

Abe et al. [40] reported IPEC and ExPEC genes in a collection of UPEC strains isolated from patients presenting symptomatic UTI in Brazil. Among the UPEC strains harboring IPEC genetic markers, the strain UPEC-46 presented characteristics of the EAEC pathotype, producing the AA pattern on HeLa cells and harboring the EAEC-associated genes aatA, aap, and pet. Recently, Nunes et al. [41] showed that UPEC-46 belongs to phylogroup A related cluster composed by the diarrheagenic strain EAEC 17–2 (O3:H2) that presented some ExPEC characteristics [18,42] and the strain EAEC C555-91, which was isolated from a UTI outbreak in Denmark [39]. Santos et al. [43] adopted the terms “hybrid-pathogenic” or “hybrid-pathogen” for strains that harbor defining IPEC and ExPEC virulence factors or are isolated from an extraintestinal infection and exhibit IPEC defining virulence factors. Although hybrid-pathogenic E. coli strains have been found in UTI, many questions about the role of these genes in the colonization, virulence potential, and pathogenicity in the urinary tract remain unanswered. Taking these into consideration, UPEC-46 could be classified as a hybrid UPEC/EAEC.

A general analysis of virulence and phenotypic characteristics of the UPEC-46 strain is essential to understand infections caused by hybrid-pathogenic E. coli strains. Thus, the goal of this study was the characterization of UPEC-46 by means of phenotypic and genotypic assays and comparative genomic analysis.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains

The E. coli strain UPEC-46 used in this study was obtained from a patient presenting symptomatic UTI, who was admitted to the emergency room of Hospital São Paulo (a tertiary university hospital in São Paulo city, São Paulo, Brazil). This strain was isolated in pure culture and identified in the Microbiology Service of the Central Laboratory at Hospital São Paulo [40]. The UPEC-46 strain was stored in lysogeny broth (LB) (Difco, USA) supplemented with 15% glycerol at −80°C.

The strains used as controls in various experiments in this study are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

Antimicrobial resistance profile

The disc diffusion test was performed with Mueller Hinton agar and paper discs (Sensibiodisc – CECON, Brazil) following the standard disk diffusion method recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [44]. The test discs were tetracycline, gentamicin, ampicillin, streptomycin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, rifampicin, imipenem, sulfatrim, amikacin, ceftazidime, norfloxacin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, cefepime, and cephalothin.

Adherence assays

HeLa (ATCC CCL-2), HT-29 (ATCC HTB-38), and 5637 (ATCC HTB-9) cells were used to evaluate the ability of the bacterial strain to interact with eukaryotic cells in culture. The qualitative adherence assays were performed as described by Cravioto et al. [45], with some modifications. Briefly, the specific cell lineages were seeded at about 1 × 105 cells per well in 24-well culture plates (Corning, USA) containing 13 mm round glass coverslips. Adherence assays were performed in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) (Cultilab, Brazil) for HeLa/HT-29 cells or Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) (Cultilab) for 5637 cells, containing 1% D-mannose and 2% fetal bovine serum, and a bacterial inoculum containing bacteria with multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. The assay mixture was incubated for 3 h or 6 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. After the incubation period, preparations were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), fixed with methanol, stained with May-Grunwald/Giemsa (Merck Millipore, USA), and examined by light microscopy.

Quantitative adhesion assays were also performed with HeLa, HT-29, and 5637 cells cultivated in 24-well culture plates without coverslips, as described above. After the incubation period (3 h or 6 h), the epithelial cells were lysed in PBS plus 1% (v/v) Triton X-100 for 10 min. Recovered bacteria were serially diluted and plated on MacConkey (MC) agar (Difco) plates, incubated overnight, and the colonies were counted to calculate the CFU/mL. Assays were performed three times in duplicate.

Biofilm formation assays

The UPEC-46 strain was evaluated for the capacity to form biofilm on glass or polystyrene under the following culture conditions: DMEM high glucose (Cultilab), preconditioned DMEM in HeLa cells, or pooled human urine. Preconditioned DMEM was prepared according to Munhoz et al. [46], using supernatants of HeLa cells cultures in DMEM. Pooled human urine was composed of samples collected from 10 healthy adult female volunteers who had no history of UTI or antibiotic use during 30 days prior to the sample collection. This protocol was approved by the National Council of Ethics in Research of Brazil (CONEP, Ministry of Health, Brazil) under Protocol No. 11159019.7.0000.5474. Urine samples collected from these individuals were pooled, filter sterilized, and stored at −20°C.

All biofilm assays were conducted in the presence and absence of 1% methyl α-D-mannopyranoside (α-D-man) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and performed three times in triplicate. The biofilm assays in polystyrene and glass surfaces were performed following the protocols previously described [47,48]. For the kinetics of biofilm formation, overnight bacterial cultures grown in LB were inoculated in a 1:40 ratio under five incubation intervals (3, 6, 9, 12 or 24 h). In these experiments, the cutoff (forming and non-forming biofilm) for the UPEC-46 strain was established according to Stepanovic et al. [49], using the E. coli strain DH5α as negative control.

Curli, cellulose and bacteriocin production

The production of curli fimbriae was evaluated using Congo red agar plates incubated at 26°C during 48 h or at 37°C during 24 h [50]. Cellulose production was detected on cellulose agar plates, as previously described [51]. The plates were also incubated at 26°C during 48 h or 37°C during 24 h. The bacteriocin production assay was based on the method described by Pugsley and Oudega [52].

Detection of Pet in culture supernatant

The secretion of Pet in the culture supernatant of UPEC-46 was investigated by immunoblotting using a rabbit polyclonal anti-Pet serum (anti-Pet IgG) [53].

Plasmid DNA analyses

The plasmid profile of UPEC-46 was determined using the protocol of Birnboim and Doly [54], and the plasmid content of E. coli strain 39R861 [55] was used as a molecular size marker and control of extraction. The conjugation experiments were based on the protocol previously described [56]. UPEC-46 (tetracycline-resistant) was used as the donor strain and E. coli MA3456 (nalidixic acid-resistant) as the recipient.

Whole-genome sequencing

Long-read Oxford Nanopore MinION (Oxford Nanopore, UK) and short-read Illumina Hiseq 1500 (Illumina, USA) platforms were combined to generate the whole-genome sequence. To generate short-read sequences, the rapid protocol (2x250 paired-end reads) was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol for sequencing. For long-read genome sequencing, a MinION sequencing library was prepared using the Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit (Oxford Nanopore). The library was sequenced with an R9.4.1 MinION flow cell for a 24 h run using MinKNOW (v2.0) with the default settings. The FAST5 files were base called and converted to FASTQ format in real-time using Guppy (v3.3.0, Oxford Nanopore). Prior to assembly, the raw reads were quality checked with FastQC (v0.11.5, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc), and low-quality reads were trimmed using Sickle (v1.33, http://github.com/najoshi/sickle). Long reads were then filtered by quality using Filtlong (v0.2.0) program, available at http://github.com/rrwick/Filtlong.

Genome assembly, annotation, and in silico analyses

Hybrid de novo genome assembly of the Nanopore and Illumina reads was performed using Unicycler (v0.4.8) [57], with default parameters. The genome assembly was analyzed using QUAST (v4.3) [58], and contigs smaller than 500 bp were discarded. The DNAPlotter (v18.0.0) [59] was used to generate circular images of plasmid sequences. Moreover, Prokka (v1.12) [60] was used to determine coding sequences (CDS) and to automatically annotate the genome. The different web-based databases ClermonTyping (v1.4.1) [61], MLST (v2.0) [62], PlasmidFinder (v2.1) [63], ResFinder (v3.2) [64], and SerotypeFinder (v2.0) [65] were used to determine in silico the E. coli phylogroups, sequence type, plasmids, acquired resistance genes, and serotypes, respectively.

All raw sequencing data generated for this study are deposited in the NCBI sequence read archive (SRA) under the accession number PRJNA728080. The whole-genome sequences (WGS) of UPEC-46 were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession number JAHBCK000000000. The plasmid sequences p46-1, p46-2, and p46-3 replicons were deposited in the GenBank database under the accession numbers NZ_JAHBCK010000003, NZ_JAHBCK010000004, and NZ_JAHBCK010000007, respectively.

Phylogenetic analyses

The different phylogenetic trees were constructed using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based phylogeny employing the draft genome sequence of strain UPEC-46 and selected reference strains. The SNP-based phylogenetic trees were created using different core genome alignments present in the parameter settings of Snippy (v3.1.0), available at https://github.com/tseemann/snippy. Recombinant genomic regions were removed using Gubbins (v2.20) [66] and the maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogenetic trees were inferred using the RAxML (v 8.2.12) [67] GTRGAMMA model with 1,000 bootstrap resampling. Finally, the trees were visualized with iTOL (v4) [68].

Identification of virulence-associated genes in strains harboring the aggregate-forming pili (AFP)-encoding genes

The afp operon was searched in the genome assembly and annotation reports of 18,360 E. coli genomes deposited in the GenBank database (accessed on 20 November 2019). The presence of virulence factors was searched using distinct E. coli virulence factor groups with 1,154 deduced protein sequences of virulence-associated genes [69].

An automated search for protein homologs in annotated bacterial genomes and the detection of E. coli virulence factors were performed with the “prot_finder” pipeline of the “bac-genomics scripts” collection using BLASTP+ (v2.2) [70]. Additionally, a phylogenetic tree with AFP-positive strains was created as described above and combined with the virulence genes panel. The heatmap of the corresponding binary presence/absence matrix was generated using the online tool iTOL.

Construction and analysis of genetically modified strains

The plasmids and strains used for the construction of mutants and complemented strains are described in Supplementary Table S1.

A nonpolar mutation in afpA, the major structural subunit of AFP, was constructed in UPEC-46 using the suicide vector pJP5603 [71]. Briefly, a 307-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the internal region of afpA was amplified with primers 4532-Fw (5′-AACAAGACTCAGAGCACCGT-3′) and 4532-Rv (5′-CATTAACCCCGACACCACC-3′) and cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega, USA). This construction was digested with EcoRI, and the insert was subcloned in pJP5603, generating pPAS2, which was transformed into E. coli S17-1(λpir) cells [72]. One transformant was used to mobilize pPAS2 into strain UPEC-46 [73]. Transconjugants were selected on LB agar plates containing kanamycin (50 µg/mL) and tetracycline (25 µg/mL). The correct site of integration was confirmed by Sanger sequencing using the ABI 3730 DNA Analyzer system (ThermoFisher, USA), and the mutant was named as UPEC-46::afpA.

For complementation purpose, the entire afpA gene was amplified from UPEC-46 by PCR using the primers FwAfpA (5′-AATGCTCGAGATGAATATTTTTACAAAAAAAG-3′) and RvAfpA (5′-TCACAAGCTTTTATTTCAGCAGGAAGGT-3′) and the amplicon was cloned into pACYC177 [74], generating pPAS3. Sanger sequencing was used to confirm the correct insertion and absence of mutation in the afpA gene, and UPEC-46::afpA was transformed with pPAS3 generating UPEC-46::afpA(pPAS3).

UPEC-46 and derivative strains were phenotypically analyzed. Single colonies were inoculated in 3 mL of LB and incubated overnight at 37°C. Each culture was then sub-cultured into 50 mL of LB, DMEM, or RPMI medium in a 1:100 ratio and incubated at 37°C with shaking. The optical density (OD) was monitored at 30 min intervals for 6 h by spectrophotometry (600 nm). This test was performed in triplicates. Strains were also evaluated on motility agar (LB containing 0.3% agar). After incubation at 37°C for 18 h, the halos obtained were measured. This test was performed three times in duplicate.

Production of anti-AFP polyclonal serum

Anti-AFP polyclonal serum was obtained in a female New Zealand white rabbit as described by Evans et al. [75], with some modifications. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Use of the Butantan Institute (CEUAIB Protocol No. 7146050620).

Initially, a single colony of UPEC-46 was inoculated in 3 mL of LB and incubated at 37°C for 18 h statically. Then, the bacterial culture was centrifuged at 700 x g for 10 min, the pellet was resuspended in 0.5% formalin in PBS and diluted to approximately 3 × 108 CFU/mL. The rabbit was inoculated intravenously at 3-days intervals with increasing volumes from 0.5 to 4.0 mL. The rabbit was bled 14 days after the eighth dose. The obtained serum was then adsorbed with the AFP-mutant strain (UPEC-46::afpA).

The pre-immune and anti-AFP sera were analyzed by immunoblotting against UPEC-46 and UPEC-46::afpA. Briefly, the wild-type and the AFP mutant strains were incubated statically in 1 mL of LB at 37°C for 18 h. Subsequently, the cells were pelleted, resuspended in 200 μL of PBS, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12%) [76]. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes that were immunodetected with either pre-immune or anti-AFP sera as the primary antibody (1:500) and the goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000) as the secondary antibody. The membranes were revealed by ECL chemiluminescence system (Amersham, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunogold labeling of AFP

The immunogold labeling of AFP from UPEC-46 and derivative strains were performed using pre-immune or anti-AFP sera (1:10), as primary antibodies, and 1:10 diluted goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 10 nm colloidal gold (Sigma-Aldrich). Preparations were negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate on Formvar-coated nickel grids and examined under transmission electron microscope (LEO 906E – Zeiss, Germany), operated at 80 kV [46].

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the GraphPad Software package (v7.0, GraphPad Software, USA). Results were analyzed by one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test or Tukey’s multiple-comparison test. The mean values ± standard deviations (SD) are shown in the figures and statistical significance was established at p < 0.05.

Results

UPEC-46 is phylogenetically related to EAEC strains with a similar virulence profile

The whole genome of UPEC-46 was sequenced, generating 23 contigs (≥ 500 bp), where three were closed as plasmids with different sizes: 135,351 bp, 108,910 bp, and 9,161 bp. The predicted genome size was 5,087,484 bp, with 50.65% of GC content.

The in silico serotyping was performed by analyzing the wzx and wzy gene sequences, identifying the serogroup O166. The fliC gene was assigned to the H12 type. Therefore, the UPEC-46 strain belongs to serotype O166:H12. Upon automatic annotation with Prokka, 4,807 CDS, 4,902 genes, and 94 tRNA were identified. Different virulence factors were recognized to be encoded by the annotated CDSs, such as adhesins, invasins, iron uptake systems, bacteriocins, toxins, and genes involved with serum resistance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Virulence factors identified in UPEC-46

| Virulence traits | Virulence factor | Name | Associated with |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adhesion/Invasion | Aap | Dispersin | IPEC |

| Aat | Anti-aggregative transporter1 | IPEC | |

| Csg | Curli1 | Various | |

| IbeB | Invasion protein | ExPEC | |

| IbeC | Invasion protein | ExPEC | |

| NlpI | Lipoprotein | ExPEC | |

| Bacteriocin | ColE1 | Colicin E1 | ExPEC |

| Mcb | Microcin B171 | ExPEC | |

| CU fimbriae | Ecp | E. coli common pilus1 | Various |

| Fim | Type 1 fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Sfm | Sfm fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yad | Yad fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Ybg | Ybg fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Ycb | Ycb fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yde | Yde fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yeh | Yeh fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yfc | Yfc fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yhc | Yhc fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Yra | Yra fimbriae1 | Various | |

| Iron uptake | Efe | Efe system1 | Various |

| Ent, Fep | Enterobactin1 | Various | |

| Fec | Ferric citrate transport1 | Various | |

| Feo | Transport of ferrous1 | Various | |

| Fhu | Ferrichrome uptake1 | Various | |

| Ybt, Irp2, Irp1 | Yersiniabactin biosynthetic system1 | Various | |

| FyuA | Yersiniabactin siderophore receptor | ExPEC | |

| Serum resistance | Iss | Serum survival | ExPEC |

| Etk, Etp, Gfc | Group 4 capsule1 | ExPEC | |

| T2SS | Gsp | T2SS-11 | Various |

| T3SS | Eiv, Epa, Epr, Yge | ETT22 | Various |

| T4P | AFP | Aggregate-forming pili1 | IPEC |

| T5SS | AatA | APEC autotransporter | ExPEC |

| Pet | Plasmid-encoded toxin | IPEC | |

| UpaC | UPEC autotransporter C | ExPEC | |

| UpaI | UPEC autotransporter I | ExPEC | |

| EhaC | EHEC autotransporter C | IPEC | |

| T6SS | Aai | AggR-activated island2 | IPEC |

| Toxins | AstA | EAST1 toxin | IPEC |

| HlyE | Hemolysin E | Various |

1, operon complete; 2, operon incomplete; CU, chaperone usher; T2SS, type 2 secretion system; T3SS, type 3 secretion system; T4P, type 4 pili; T5SS, type 5 secretion system; T6SS, type 6 secretion system.

We also evaluated the uropathogenic potential based on the presence of the virulence markers chuA (heme receptor), fyuA (yersiniabactin siderophore receptor), vat (vacuolating autotransporter protein), and yfcV (YfC fimbriae), as defined by Spurbeck et al. [27]. UPEC-46 strain did not meet this criterion since only fyuA and yfcV were detected. Interestingly, none of the genes defined by Johnson et al. [77], as markers of ExPEC intrinsic virulence potential (papA and/or papC, afa/dra, sfa/foc, iucD/iutA, and kpsMT II) were found in the genome of UPEC-46.

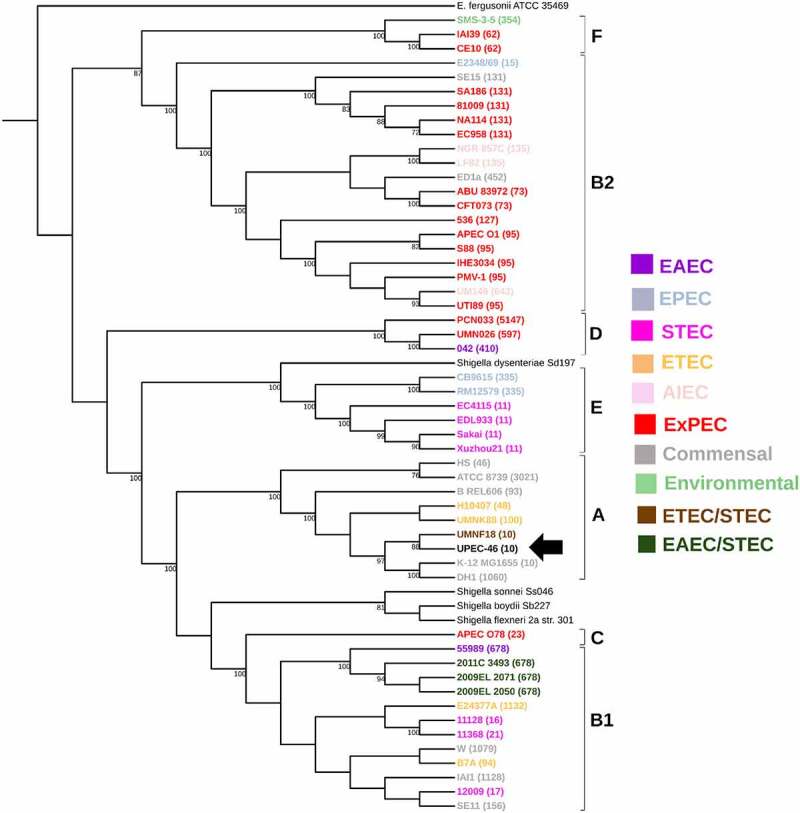

In the phylogenetic analyses, firstly, we created a general phylogenetic tree using the whole genome of UPEC-46 strain compared to genomes from 51 reference E. coli strains from public databases (Supplementary Table S2). The reference strains comprised different E. coli groups, such as commensal, environmental, IPEC, and ExPEC. These groups belong to diverse MLST and phylogenetic lineages (A, B1, B2, C, D, E, and F), indicating a high phylogenetic diversity in the strain panel. The phylogenetic tree constructed presented in general high bootstrap support values, and the UPEC-46 isolate clustered with the strains belonging to ST10 and phylogroup A, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Whole genome-based phylogenetic of UPEC-46 and reference E. coli strains. The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized with iTOL and E. coli pathotypes or E. coli groups are indicated by colors. ST numbers from the MLST analysis for each strain are given in parentheses and phylogroups appointed. The UPEC-46 strain is indicated by a black arrow. E. fergusonii serves as an outgroup

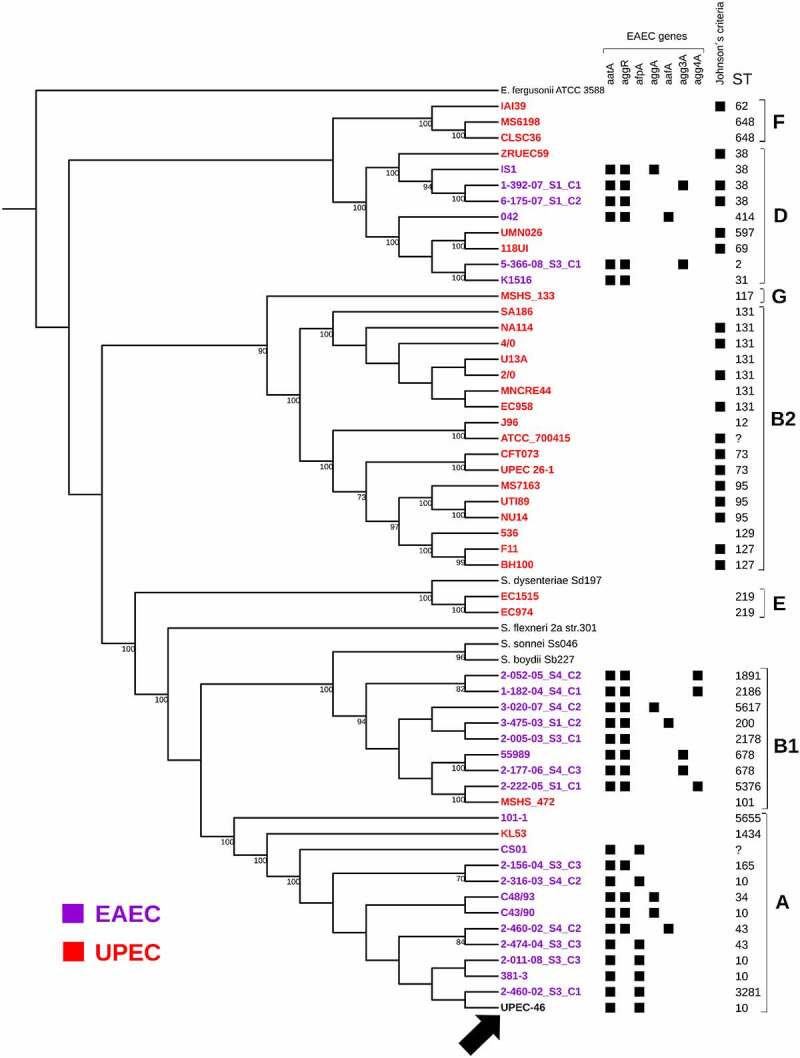

With a second phylogenetic analysis, we evaluated the relationship between UPEC-46 and representative EAEC and UPEC strains belonging to diverse phylogenetic and MLST lineages (Supplementary Table S3). As expected, this analysis showed that the majority of UPEC strains were distributed in three phylogenic groups B2, F, and D, whereas EAEC strains belonged to phylogroups A, B1, and D. UPEC-46 was related to EAEC strains since it was located in a clade closely associated only with EAEC strains, which do not meet the Johnson's criteria [77], defining E. coli strains with intrinsic ExPEC virulence (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Whole genome-based phylogeny and genetic characteristics of UPEC-46 and selected EAEC and UPEC strains. The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized with iTOL, where UPEC-46, EAEC, and UPEC strains are indicated by black, purple, and red colors, respectively. The different STs and phylogroups are appointed. The following EAEC-associated virulence genes were searched: aggR (virulence regulator), aatA (anti-aggregation protein transporter), aggA (AAF/I fimbriae), aafA (AAF/II fimbriae), agg3A (AAF/III fimbriae), agg4A (AAF/IV fimbriae), and afpA (AFP, type 4 pili). The strains were positive for Johnson’s criteria (criteria for ExPEC) if positive for ≥2 of the five ExPEC markers, i.e., pap (P fimbriae), sfa/foc (S/F1C fimbriae), afa/dra (Dr binding adhesins), iucD/iutA (aerobactin receptor), and kpsMT II (group 2 capsule synthesis) [77]. The UPEC-46 strain is indicated by a black arrow. E. fergusonii serves as an outgroup

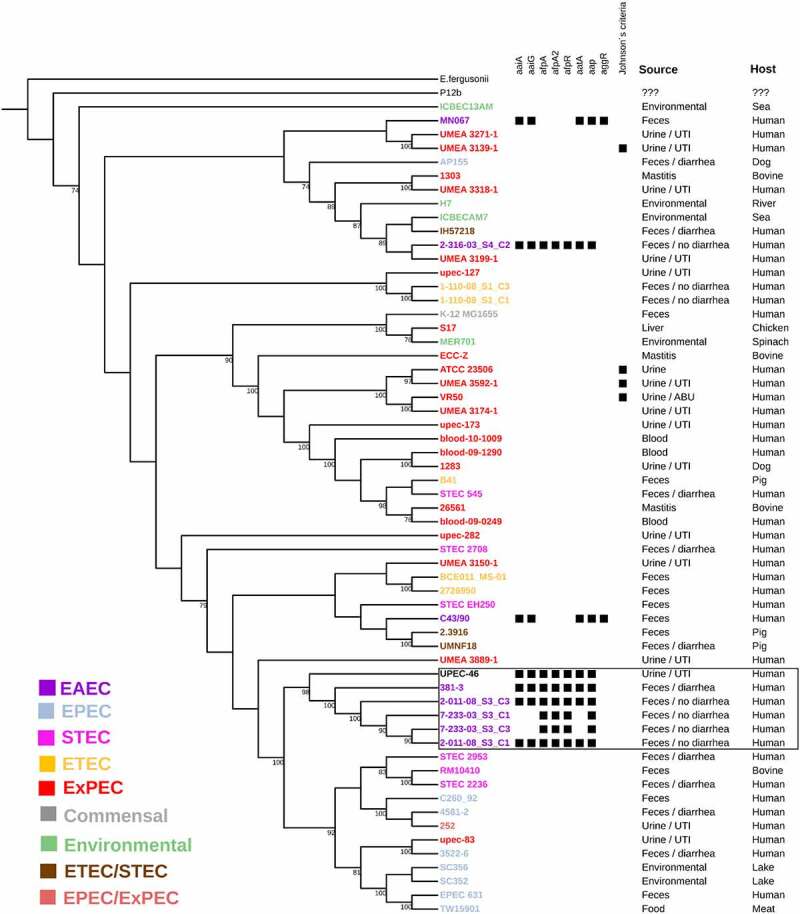

In a third phylogenetic tree, the relationship between UPEC-46 and several ST10 E. coli strains, isolated from distinct sources, was assessed. This analysis showed that UPEC-46 is phylogenetically close to a group of EAEC strains with a similar virulence profile, incl. genes associated with the AFP adhesin (afpA, afpA2 and afpR), and other EAEC genes (aatA, aap, aaiA, and aaiG) [78]. Interestingly, these strains were isolated from human feces as part of the microbiota or involved in diarrheal cases, devoid of aggR and negative for the criterion of ExPEC intrinsic virulence [77] (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S4).

Figure 3.

Whole genome-based phylogeny and genetic characteristics of UPEC-46 and selected E. coli ST10 strains. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by using the maximum-likelihood method and bootstrap with 1,000 replicates. The tree was visualized with iTOL and different E. coli pathotypes or E. coli groups are designated with a color code. The following UPEC-46-associated virulence genes were searched: aggR (virulence regulator), aatA (anti-aggregation protein transporter), aaiAG (aggR-activated Island), aap (dispersin, anti-aggregation protein) and afpA, A2, R (AFP, type 4 pili). The strains were positive for Johnson’s criteria (criteria for ExPEC) if positive for ≥2 of the five ExPEC markers, i.e., pap (P fimbriae), sfa/foc (S/F1C fimbriae), afa/dra (Dr binding adhesins), iucD/iutA (aerobactin receptor) and kpsMT II (group 2 capsule synthesis) [77]. UPEC-46 strain is related to strains with similar virulence profile (afp positive) present in the box. E. fergusonii serves as outgroup. UTI: urinary tract infection; ABU: asymptomatic bacteriuria

Therefore, by different phylogenetic comparisons, UPEC-46 was phylogenetically related to EAEC strains isolated from human feces, with similar virulence profiles (aggR-/afp+).

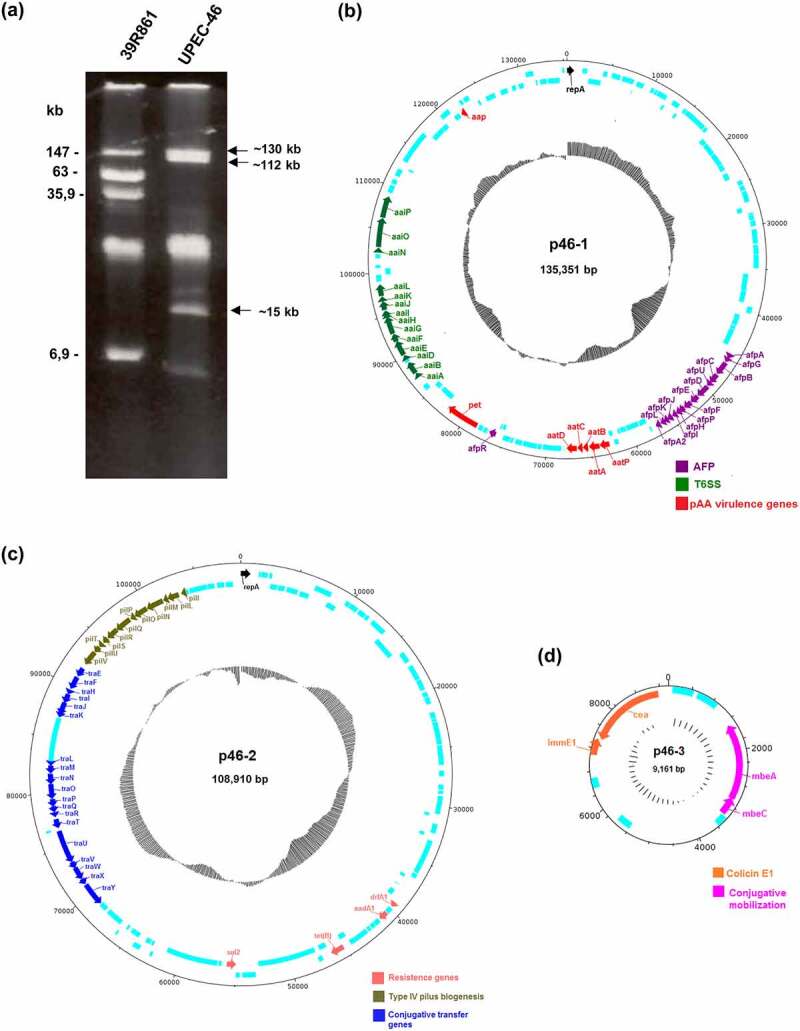

UPEC-46 harbors three circular plasmids

Plasmid profile analyses by agarose gel electrophoresis confirmed that UPEC-46 carries three plasmids: two bands of ~130 kb and ~112 kb indicated plasmids with high molecular size in addition to one plasmid band of approximately ~15 kb (Figure 4(a)).

Figure 4.

Plasmid profile and comparison of plasmids architecture present in UPEC-46. (a) Plasmid content of the UPEC-46 strain obtained by alkaline extraction, followed by electrophoresis in 0.8% agarose gel in Tris-Borate-EDTA (TBE) buffer. Approximate sizes were predicted based on the plasmid migration in agarose gel. The E. coli strain 39R861 represents the standard strain containing plasmids of known molecular weights. (b) Plasmid p46-1 (virulence plasmid) carries genes typical for EAEC strains (aatA, B, C, D, and P; aap; pet). Additionally, it contains an operon encoding an aggregate-forming pilus (afp) and an operon encoding a type 6 secretion system (T6SS, aai). (c) Plasmid p46-2 (encoding antibiotic resistance) harbors genes for the pil pilus (type 4 pili biogenesis), conjugative transfer genes and resistance genes. (d) Plasmid p46-3 (colicinogenic plasmid) carries genes for colicin E1 synthesis and conjugative mobilization genes. CDS are presented in light blue and GC-content is depicted in black inner circles

Analyzing the plasmid sequences, we observed that the ~135 kb plasmid (plasmid p46-1) contains a complete afp operon (afpAGBCUDEFPHIJKLA2) as well as afpR coding for the corresponding AraC-like regulator. The afp operon comprises the genes responsible for the biogenesis of aggregate-forming pili (AFP). p46-1 also harbors a truncated putative type 6 secretion system (T6SS) termed as aaiA-P, where aaiC and aaiM are absent. In addition, this plasmid harbors the following EAEC-associated genes: aatPABCD operon, aap, and pet (Figure 4(b)), commonly associated with the pAA plasmid present in the prototypical EAEC strain 042 [79]. The ~109 kb plasmid (plasmid p46-2) carries the resistance genes aadA1, dfrA1, sul2, and tet(B) and confers resistance to various antibiotic agents, such as streptomycin, trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline, respectively. p46-2 carries a type 4 pili biosynthesis locus (pilI-V) and the conjugative transfer genes (tra operon), associated with bacterial conjugation (Figure 4(c)). p46-3 is the smallest plasmid (~9 kb) harboring the colicin E1 gene (cea) and the genes mbeA and mbeC, associated with conjugative mobilization proteins (Figure 4(d)). Lastly, two different replicon sequences (IncFII and IncB/O/K/Z) were found in UPEC-46 using the program PlasmidFinder, which belong to p46-1 and p46-2, respectively.

To verify if these plasmids could be related to the virulence and antimicrobial resistance profile of UPEC-46, conjugation experiments were performed using strain UPEC-46 as donor and E. coli MA3456 as recipient. Among eleven transconjugants obtained, three carried both the ~112 and ~15 kb plasmid (Supplementary Figure S1), whereas eight carried only the ~112 kb plasmid. None of the eleven transconjugants produced the AA pattern on HeLa cells (data not shown) indicating that the AA pattern-related determinants were not located in these plasmids. Then, they were evaluated for their antimicrobial resistance profile. UPEC-46 showed antimicrobial resistance against streptomycin, sulfatrim (combination of sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim), and tetracycline. Likewise, the eight transconjugants harboring only the ~112 kb plasmid presented resistance to these antibiotics, confirming that the ~112 kb plasmid conjugative plasmid carried the UPEC-46 antimicrobial resistance determinants.

UPEC-46 has phenotypic characteristics associated with EAEC and ExPEC

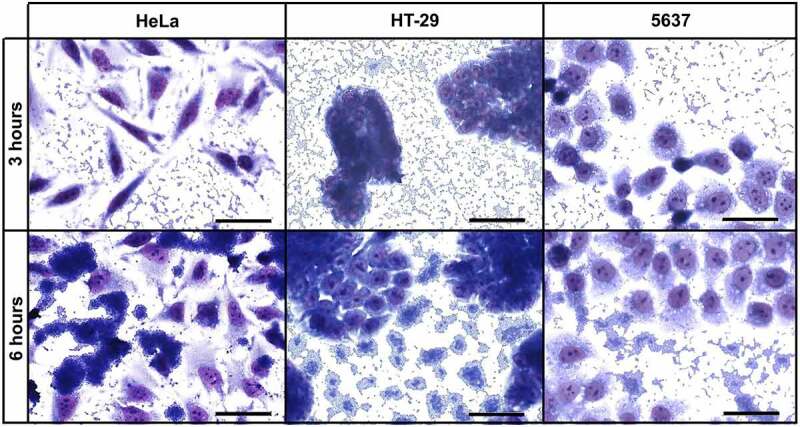

The ability of UPEC-46 to produce the AA pattern on different epithelial cell lineages was investigated. As previously reported [40], this strain adhered to HeLa cells presenting the typical AA pattern, observed after 3 h and more intensely after 6 h of bacteria-HeLa cell interaction. Likewise, UPEC-46 was able to colonize intestinal (HT-29) and urinary bladder epithelial (5637) cells, and the AA pattern was observed on both cell lines after 3 h, and more intensely after 6 h incubation (Figure 5). All adherence assays were performed in the presence of 1% D-mannose to inhibit type 1 fimbria-mediated bacterial adherence.

Figure 5.

Qualitative adherence assay of UPEC-46 with different cell lineages. The patterns were identified after 3 h and 6 h of infection, in the presence of 1% D-mannose, using HeLa (cervical carcinoma), HT-29 (colorectal adenocarcinoma) and 5637 (human urinary bladder) cells. Evaluation of patterns by light microscopy. Bars = 50 µm

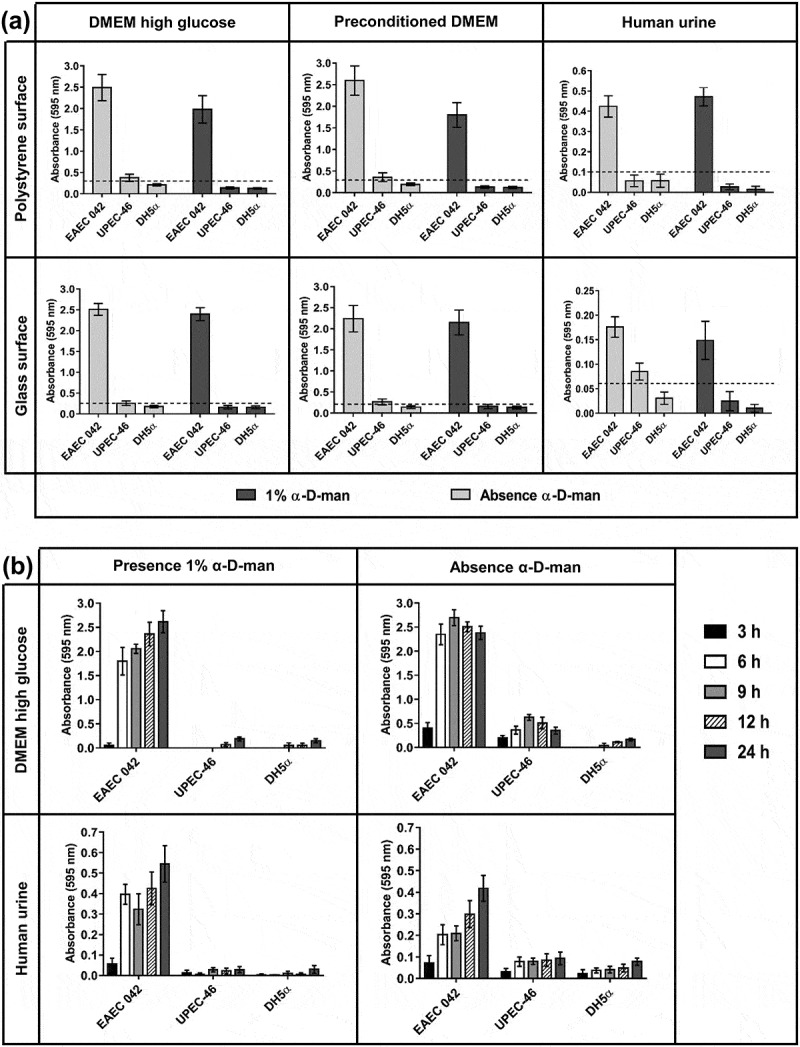

As the AA pattern is strongly associated with biofilm formation on abiotic surfaces [47], UPEC-46 was evaluated for this phenotype using different culture conditions (DMEM high glucose, preconditioned DMEM, and human urine) on glass or polystyrene surfaces. As shown in (Figure 6(a)), after 24 h of incubation in the presence of α-D-man, UPEC-46 could not form biofilm in all conditions tested, showing similar ODs as the negative control (E. coli DH5α). In the absence of α-D-man, UPEC-46 biofilm formation was weak and did not markedly differ between the different conditions analyzed, presenting absorbance values lower than the positive control (EAEC 042). As shown in (Figure 6(b)), the kinetics of biofilm formation on polystyrene was also evaluated upon 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h of incubation and under different culture conditions (DMEM high glucose vs. human urine). In the presence of α-D-man, UPEC-46 presented low absorbance values, similar to the negative control, in both conditions tested. In the absence of α-D-man, although still lower than the positive control (EAEC 042), the absorbance values for UPEC-46 were higher, increasing until 9 h of incubation, before decreasing again at later time points.

Figure 6.

Biofilm and kinetics of biofilm formation of UPEC-46. (a) The biofilm formation assays were performed in different culture media (DMEM high glucose, preconditioned DMEM, and human urine) and abiotic surfaces (polystyrene and glass), with incubation for 24 h at 37°C. The dashed line represents the cutoff OD between forming and non-forming biofilm strains [49]. The cutoff was defined as three standard deviations above the mean OD of the negative control. (b) The kinetic assays were performed in DMEM high glucose or human urine culture media during different incubation periods (3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h) on polystyrene surface at 37°C. These tests were performed in the presence or absence of 1% α-D-man. In all tests performed, EAEC 042 and E. coli DH5α were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The assays were performed in triplicate and repeated three times. The data presented consist of the mean ± standard deviation

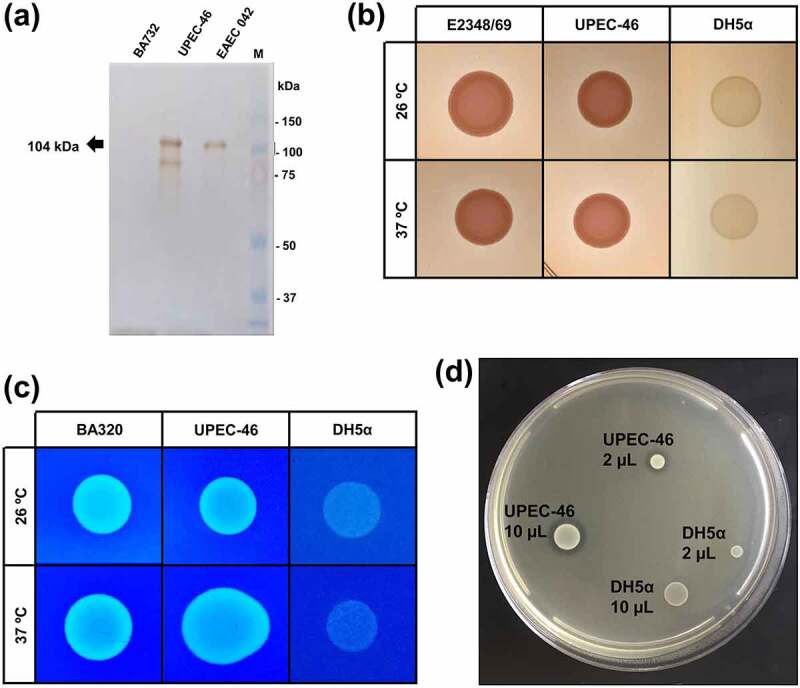

As the Pet-encoding gene was detected in UPEC-46 [40], we evaluated the secretion of Pet in the culture supernatant. Using a polyclonal serum against Pet, a 104 kDa protein was recognized in precipitated culture supernatants of UPEC-46 and EAEC 042 (positive control), strongly suggesting that Pet is secreted by UPEC-46 (Figure 7(a)).

Figure 7.

Phenotypic characteristics of UPEC-46. (a) Pet detection in the UPEC-46 using culture supernatants. The bacterial supernatants were cultivated in LB and precipitated with Trichloroacetic acid (TCA). Immunoblotting was performed with anti-Pet IgG and developed with Diaminobenzidine. Positive control: EAEC 042. Negative control: EAEC BA732. M: Precision plus protein™ dual color standards (Bio-Rad, USA) used as molecular weight. (b) Analysis of curli expression using the Congo red agar at 26°C and 37°C. EPEC E2348/69 and E. coli DH5α represent positive and negative controls, respectively. (c) Cellulose expression using the cellulose agar at 26°C and 37°C. E. coli BA320 and DH5α were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (d) Bacteriocin production of UPEC-46. A drop of 2 and 10 μL of the overnight culture (UPEC-46 and negative control) was placed on a plate containing a freshly prepared lawn of E. coli C600 (indicator strain for bacteriocin production). After overnight incubation at 37°C, the plate was examined for clear zones. E. coli DH5α was used as a negative control

Also, other important phenotypic analyses were performed with UPEC-46, including the detection of curli, cellulose, and bacteriocin production. As presented in (Figure 7(b,c)), curli and cellulose expression was detected upon incubation at 26 and 37°C. Bacteriocin production was detected by the presence of a halo surrounding the UPEC-46 colonies resulting from growth inhibition of the indicator strain E. coli strain C600 (Figure (7d)).

AFP-positive E. coli strains exhibit different virulence profiles

In the phylogenetic analyses we observed the presence of afp genes (afpA, afpA2, and afpR) in EAEC strains closely related with UPEC-46. Since AFP has been recently described [78], there is not much information on the genotypic characteristics of AFP-positive strains and whether there is indeed a functional convergence in terms of virulence genes. In order to characterize AFP-positive EAEC more precisely with regard to their virulence gene pool, all E. coli genomes deposited in the NCBI database were searched for the presence of the afp gene cluster and the virulence gene profiles of these genomes were determined.

The genome sequence analysis identified 25 afp-positive E. coli genomes deposited in NCBI (at the date of 20 November 2019) (Supplementary Table S5). The different in silico analyses performed with the 25 afp-positive strains and UPEC-46, indicated that 24 strains belonged to phylogroup A (including UPEC-46), whereas two strains belonged to phylogroup B1. Ten and six strains were allocated to two major MLST lineages (ST10 and ST43), respectively. The remaining ten strains represented different STs. In addition, all analyzed strains harbored at least one plasmid, and the IncF plasmid replicon was detected in all strains (except for the strain 381–3). Antibiotic resistance genes were predicted in 18 isolates and different resistance profiles were found. We also observed that these strains had different EAEC virulence gene profiles, where the aatA gene, described as strictly associated with AFP-positive strains [78,80], was not found in two E. coli strains (7–233-03_S3_C1 and 7–233-03_S3_C3). The in silico characteristics of the AFP-positive strains are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Genome sequence-based characterization of AFP-positive strains

| AFP-positive strain | Phylogroup | Serotype | Sequence type | Plasmid replicon sequences | EAEC-associated genes | Antibiotic resistance genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2–005-03_S4_C1 | A | ONT:H10 | 43 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA, aap | sul1, sul2, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, tet(A), dfrA14, dfrA7, blaTEM-1B |

| 2–011-08_S3_C1 | A | ONT:H10 | 10 | Col, IncFII | aatA, aap, astA | sul2, dfrA8, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM-1B |

| 2–011-08_S3_C2 | A | O111:H12 | 43 | ColpVC, IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA, aap | blaTEM-1B, tet(A), dfrA14, dfrA7, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, sul1, sul2 |

| 2–011-08_S3_C3 | A | ONT:H10 | 10 | IncFII | aatA, aap, astA | dfrA8, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM-1B |

| 2–316-03_S4_C2 | A | ONT:H10 | 10 | IncFII | aatA, aap | blaTEM-1B, sul2, dfrA8, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id |

| 2–460-02_S3_C1 | A | O111:H12 | 3281 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII | aatA, aap | dfrA14, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, sul2, tet(A) |

| 2–460-02_S3_C2 | A | O111:H12 | 3281 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII | aatA, aap | dfrA14, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, sul2, tet(A) |

| 2–474-04_S3_C1 | A | ONT:H10 | 43 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA | blaTEM-1B, tet(A), dfrA14, dfrA7, sul1, sul2, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id |

| 2–474-04_S3_C2 | A | ONT:H10 | 43 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA, aap | blaTEM-1B, tet(A), dfrA14, dfrA7, sul1, sul2, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id |

| 2–474-04_S3_C3 | A | ONT:H10 | 43 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA, aap | blaTEM-1B, tet(A), dfrA14, dfrA7, sul1, sul2, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id |

| 3–073-06_S3_C2 | A | ONT:H10 | 43 | IncFII, IncQ1 | aatA, aap | aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, tet(A), sul1, sul2, blaTEM-1B, dfrA7 |

| 7–233-03_S3_C1 | A | ONT:H10 | 10 | IncFII | aap, astA | - |

| 7–233-03_S3_C3 | A | ONT:H10 | 10 | Col, IncFII | aap | - |

| 12–05829 | B1 | O23:H8 | 26 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFIB, IncFIC | aatA, aap, astA | - |

| 381–3 | A | O126:H2 | 10 | IncB/O/K/Z | aatA, aap | blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM-1B |

| 401,368 | A | O151:H12 | 10 | Col, IncFIC, IncI1 | aatA, aap, pic, astA | dfrA14, aph(3”)-Ib, aph(6)-Id, blaTEM, sul2 |

| AM22-15AC | A | ONT:H30 | 3075 | ColpVC, IncFII, IncY | aatA, aap, pet, astA | tet(A) |

| AM34-8 | A | O10:H32 | 1286 | IncFII, IncX1 | aatA, aap, pet | blaTEM-1B, qnrS1, tet(A), sul3, aph(6)-Id |

| CS01 | A | ONT:H30 | ? | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFIA, IncFIB, IncFII | aatA, aap | dfrA5, tet(B), sul1 |

| DEC6C | A | O111:H12 | 10 | IncFII | aatA, aap | - |

| ECM-1 | A | ONT:H30 | 2349 | IncFIB, IncFII, IncI1, IncX3 | aatA, aap | sul2, tet(A), aadA1, dfrA1, qnrB7, qnrS1, qnrS2, blaCTX-M-15, blaTEM |

| MRE600 | A | O150:H9 | ? | IncFII | aatA | - |

| NCTC9035 | A | O35:H10 | 10 | IncFIC | aatA, aap, pet, astA | - |

| NCTC9062 | A | O62:H30 | 34 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII | aatA, aap | - |

| NCTC9097 | B1 | O97:H- | 5466 | IncFII | aatA, aap | - |

| UPEC-46 | A | O116:H12 | 10 | IncB/O/K/Z, IncFII | aatA, aap, pet, astA | aadA1, sul2, tet(B), drfA1 |

EAEC genes searched: aggR (global virulence regulator), aatA (anti-aggregation protein transporter), aap (dispersin), pet (plasmid-encoded toxin), pic (protein involved in colonization) and astA (EAEC heat-stable enterotoxin 1); NT, non-typable.

Next, the AFP-positive strains were clustered according to the presence and absence of different virulence factors. The resulting heatmap is presented in Supplementary Figure S2. For this, the presence of 398 genes coding for main virulence-associated factors of IPEC and ExPEC were analyzed. The results are presented in Supplementary Table S6. A high diversity of virulence factors was observed among the AFP-positive E. coli strains. All of them harbored widely prevalent genetic determinants of E. coli, such as the operons encoding type 1 fimbriae, curli fimbriae, and the Flag-1 flagella system. On the other hand, other important virulence factors, such as iron transport systems (i.e., ferric citrate transport, aerobactin, and yersiniabactin), the type 2 secretion system 1 (T2SS-1), type 3 secretion system 2 (ETT-2) and the type 6 secretion systems (T6SS/1, Aai and SCI-I) were not present in all AFP-positive strains. The complete afp operon was identified in all 26 strains, and the putative AraC-type regulator, designated as AfpR, was found in all strains (except in E. coli 2–474-04_S3_C1) (Supplementary Figure S2).

AFP is expressed on the bacterial surface of UPEC-46

The AFP mutant and complemented strains were constructed to evaluate the ultrastructure of AFP on the surface of UPEC-46 and its role in bacterial adherence. Initially, the growth and motility of the mutants were analyzed. No marked differences were observed in the generation times for UPEC-46, UPEC-46::afpA, and UPEC-46::afpA (pPAS3) grown in LB, DMEM, or RPMI (Supplementary Figure S3a). Also, motility was not affected by mutation or complementation of the afpA gene (Supplementary Figure S3c).

Next, a specific anti-AFP serum was produced for immunolabeling-based transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses. The anti-AFP serum was extensively adsorbed against the afpA mutant strain (UPEC-46::afpA), and its reactivity was first evaluated by immunoblotting of total protein extract of UPEC-46. As presented in Supplementary Figure S4, the anti-AFP serum recognized a protein band with a molecular weight similar to that predicted for the major pilin AfpA (~21 kDa) in the wild-type but not in the afpA mutant strain. Also, the rabbit pre-immune serum did not recognize bands in the protein extracts evaluated (Supplementary Figure S4a).

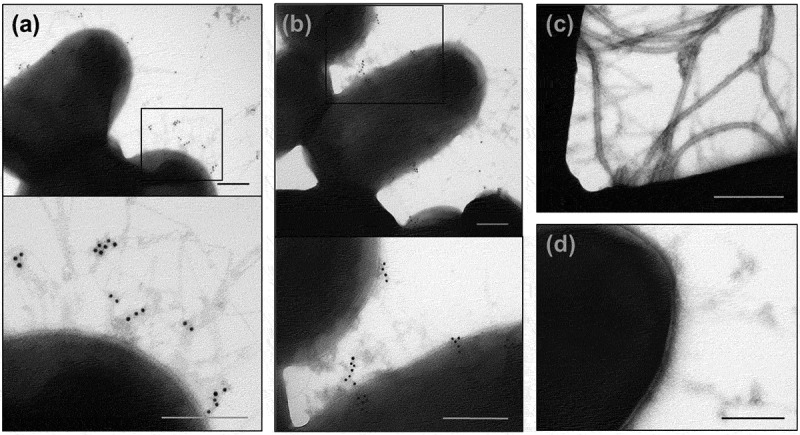

Next, the presence of AFP on the UPEC-46 cell surface was examined by immunogold labeling and electron microscopy, using the pre-immune or the anti-AFP sera as primary antibodies and goat anti-rabbit IgG antiserum conjugated to 10 nm colloidal gold as secondary antibody. Presence of fimbrial structures, presumably pili, were detected with the anti-AFP adsorbed serum in both, wild-type and complemented strains (Figure 8(a,b)) around the bacterial cell. These structures were not observed in the AFP mutant strain (Figure 8(c)), or in wild-type strain treated with the pre-immune serum (negative control of the reaction) (Figure 8(d)).

Figure 8.

Immunogold labeling of AFP and TEM analysis. (a) wild-type UPEC-46, (b) complemented mutant (UPEC-46::afpA (pPAS3)), and (c) afpA mutant (UPEC-46::afpA) were labeled with adsorbed anti-UPEC-46 serum and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with 10 nm gold particles, contrasted with 2% uranyl acetate in water. (d) Wild-type strain (UPEC-46) labeled with pre-immune serum was used as negative control. Bars = 200 nm

AFP contribute to UPEC-46 adherence to both urinary and intestinal epithelial cells

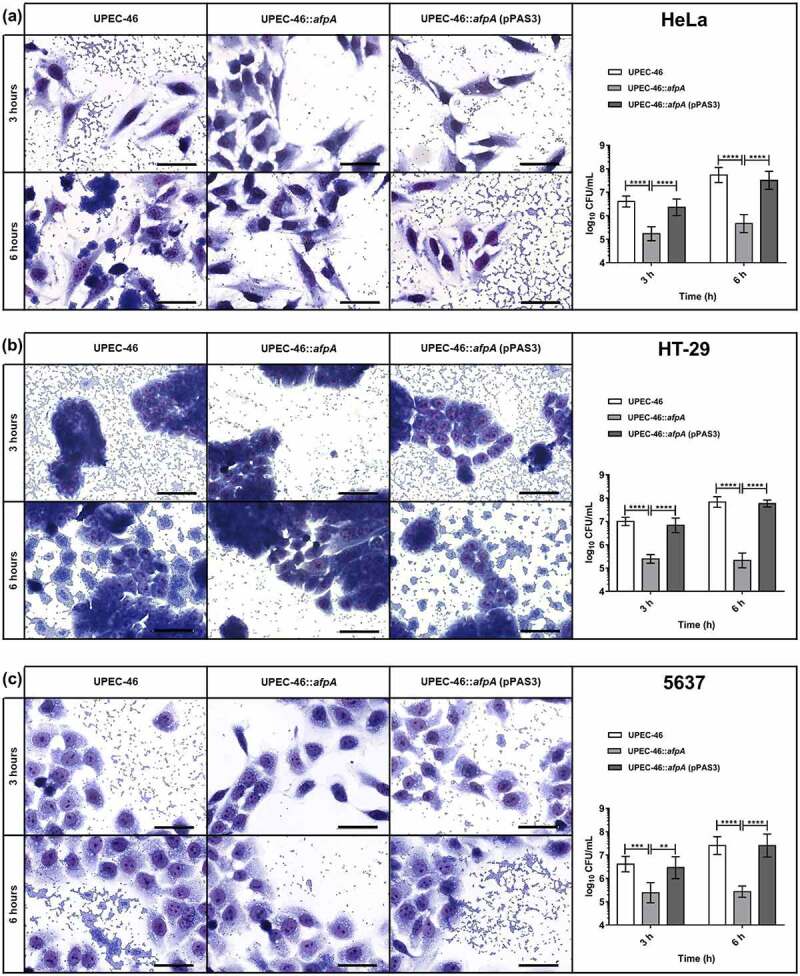

Qualitative and quantitative adherence assays of UPEC-46, UPEC-46::afpA, and UPEC-46::afpA (pPAS3) were performed with HeLa, HT-29, and 5637 cells (Figure (9)). In the qualitative assay, the AA pattern displayed by the wild-type strain was abolished in the mutant strain (UPEC-46::afpA) and restored in the complemented strain (UPEC-46::afpA (pPAS3)) with all three cell lines.

Figure 9.

Adherence assays of UPEC-46 and derivatives with different epithelial cell lineages. The adherence ability was identified after 3 h and 6 h of infection, in the presence of 1% D-mannose, using (a) HeLa (human cervical adenocarcinoma), (b) HT-29 (human colon adenocarcinoma), and (c) 5637 (human urinary bladder carcinoma) cells. In qualitative adherence assays, the evaluation of the AA pattern was performed using light microscopy. Bars = 50 µm. For quantitative adherence assays, the number of cell-adhering bacteria was quantified 3 h and 6 h post-infection as described in materials and methods. The adherence assays with UPEC-46, UPEC-46::afpA, and UPEC-46::afpA (pPAS3) were performed in duplicate and repeated three times. The data presented represent of the mean ± standard deviation. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple-comparison test was used for the statistical analysis. P-value: ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001; **** P < 0.0001

In the quantitative adherence assays, UPEC-46 showed a strong adherence to all eukaryotic cell lines upon different time points analyzed (3 and 6 h), and UPEC-46::afpA exhibited a significant (p < 0.01) decrease in adherence to all cell lines. Complementation of UPEC-46::afpA restored the adherence score under all conditions tested. In summary, these assays showed that AFP contributes to the adherence phenotype of UPEC-46 and to the establishment of the AA pattern.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the geno- and phenotypic characteristics of UPEC-46. In our initial analyses, the characteristic AA pattern was also observed with intestinal (HT-29) and bladder (5637) cell lines. These results suggested that UPEC-46 could be a hybrid-pathogenic (UPEC/EAEC) strain able to cause intestinal and extraintestinal infections. In this context, the absence of specific virulence markers used to define ExPEC or UPEC intrinsic virulence of an E. coli strain [27,77] classified UPEC-46 as ExPEC negative (ExPEC−) and UPEC negative (UPEC−). Although the presence of these specific virulence markers correlates with the extraintestinal and uropathogenic potential of E. coli isolates, extraintestinal infections may nevertheless be caused by strains devoid of these genes [29,33,36,37,81,82].

The genomic analysis of UPEC-46 identified several virulence genes, including those encoding adhesins (e.g., operons sfm, yad, ybg, ycb, yde, yeh, yfc, yhc, and yra), bacteriocins (colE1 and operon mcb), iron acquisition factors (fyuA), polysaccharide capsule (group 4 capsule), serum resistance (iss), and invasins (ibeB and ibeC), some of them being epidemiologically associated with extraintestinal infections [25,83–86]. In addition, like other hybrid E. coli strains (UPEC/EAEC), UPEC-46 carries virulence genes related to the EAEC pathotype (e.g., aap, pet, and the aai and aat operons), reflecting the dual genotypic profile commonly associated with these strains.

Secretion of bacteriocins increases the competitiveness of E. coli strains [87]. Colicin E1 is a bacteriocin that has been associated as an important virulence factor in UPEC [88]. As UPEC-46 harbored colE1 and produced colicin E1 in vitro, this strain has a competitive colonizing potential in the urinary and intestinal tracts since bacteriocin production may interfere with the growth of colicin-sensitive E. coli variants.

Pet is a toxin firstly described in EAEC [15] that causes intracellular cleavage of fodrin, disrupting the actin cytoskeleton, leading to enterotoxic and cytotoxic effects [16,89]. The intrinsic function of Pet is associated with EAEC intestinal infections [90]. However, some studies showed the presence of the pet gene in ExPEC strains [29,32]. In addition, our group verified that Pet has a cytotoxic effect on the human urinary bladder epithelial cell line 5637 (unpublished data). As Pet secretion was detected in the culture supernatant of UPEC-46, this toxin could have a role in uropathogenesis.

UPEC-46 adhered to different epithelial cell lines in the AA pattern and expressed important virulence factors associated with biofilm formation, such as type 1 fimbriae, curli, and cellulose; however, it was unable to form strong biofilms on different abiotic surfaces and under different culture conditions, including growth in pooled human urine. Some studies have shown that specific EAEC virulence factors, such as aggR (transcriptional activator) and AAFs (EAEC fimbriae), are involved in biofilm formation at levels significantly higher than strains negative or defective of these factors [38,47], corroborating the results obtained in this study, since UPEC-46 is devoid of these two virulence factors.

The genomic analysis of UPEC-46 showed that this strain carries three distinct plasmids, two of which (p46-2 and p46-3) were successfully transferred by conjugation, thereby allowing the identification of a correlation of p46-2 with antimicrobial resistance. The genotypic analyses identified the pil/tra operons and mbeA and mbeC genes related to plasmid transfer in these two plasmids. In addition, it was observed that p46-1 carries some EAEC virulence genes (e.g., aatA, pet, aap, and the aai operon). However, it is devoid of aggR, which encodes the EAEC master virulence regulator [20]. As EAEC strains may be classified as ”typical“ or ”atypical“, based on the presence or absence of aggR, respectively [91], the presence of p46-1 provides to UPEC-46 a virulence profile of atypical EAEC strains. Also, p46-1 presented some similarities to the pAFP plasmid described by Lang et al. [78], harboring the afp and aat operons, aap, afpR, and parts of the aai operon.

In this context, from the data observed by the geno- and phenotypic analysis of UPEC-46, two hypotheses were raised regarding its phylogenetic origin: UPEC-46 could be an atypical EAEC strain that, over time, acquired ExPEC genes therefore enabling UPEC-46 to establish UTI. Alternatively, an ExPEC strain could have received the plasmid p46-1 (EAEC-associated plasmid). Our phylogenetic analyses indicated that UPEC-46 was placed in a separate phylogenetic branch together with other strains with an atypical EAEC genomic background that have been isolated from patients with or without diarrhea. Interestingly, analyzing different ST10 E. coli strains, we showed that UPEC-46 belongs to a specific cluster of atypical EAEC strains, presenting the afp operon genes and its regulator gene (afpR). In UPEC-46, the afp operon and the afpR regulatory gene were identified in the plasmid p46-1, along with other EAEC-associated genes. Thus, the data obtained from our phylogenetic analysis indicate that UPEC-46 has a genomic background associated with atypical EAEC strains harboring the afp operon. AFP was described to confer the AA pattern of a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC)/EAEC strain of serotype O23:H8 [78], and was recently found in atypical EAEC strains isolated from diarrhea [80]. Therefore, we decided to investigate further the role of AFP in adherence traits of UPEC-46.

AFP presentation was observed by immunogold labeling on the surface of UPEC-46 as fimbrial structures not assembled in bundles, as described for the bundle-forming pilus (BFP) of enteropathogenic E. coli, another type 4 pili [92]. It is interesting to note that the operons encoding AFP and BFP share the same genetic organization but have only approximately 42% protein identity [78]. The ultrastructure of AFP observed by TEM on the surface of UPEC-46 resembles fimbria-like structures observed by scanning electron microscopy with the STEC/EAEC strain as described by Lang et al. [78]. The reason for the different appearance of AFP and BFP is unclear and may be due to differences in the amino acid composition of both pilin subunits. The presence of non-labeled fimbrial structures on the bacterial surface observed in TEM preparations supports the idea that other adhesins could be co-expressed together with AFP. Furthermore, the amount of fimbrial structures labeled with anti-AFP serum could be also related to the culture medium (LB medium) and other bacterial growth conditions used in this study. Therefore, future studies will be needed to verify the best condition for AFP expression in E. coli strains in vitro.

Our bioinformatic analyses showed that AFP-positive isolates do not share a common profile of virulence factors. The diversity of virulence profiles among E. coli strains classified by isolation site or classical genetic defining markers is a common feature resulting from the high frequency of horizontal gene transfer of E. coli virulence genes. Thus, the AFP-positive strains cannot be associated with a single virulence profile. However, the results obtained in this study show that the absence of specific genes associated with ExPEC and the presence of atypical EAEC determinants could be associated with the genotypic characteristics of these strains.

The absence of genes encoding typical ExPEC adhesins or aggregative adherence fimbriae (AAF) characteristic of EAEC in the genome of UPEC-46 supports the idea that other adhesins could be involved in establishing the AA phenotype of this strain. Our data suggested that AFP mediate the AA pattern of UPEC-46. Therefore, we analyzed the effects of afpA mutation in UPEC-46 to evaluate the role of AFP in its adherence phenotype. A significant reduction of the adherence and absence of the AA pattern was observed on HeLa, HT-29, and 5637 cells. The effect of the afpA mutation confirmed that the novel AFP adhesin is essential for adhesion and the establishment of the AA pattern, as previously shown for STEC/EAEC and EAEC strains [78]. Although, to our knowledge, there are still no studies showing the prevalence of AFP in collections of E. coli strains isolated from UTI, genes of the afp operon were detected in atypical EAEC strains obtained from diarrheal patients in Brazil [80]. Further investigations by our group are currently in progress to examine whether AFP is involved in the uropathogenicity of the UPEC-46 strain and whether this adhesin also plays a role in intestinal colonization. We also highlight that the present study represents the first report that shows the role of AFP in establishing the AA pattern on either bladder or intestinal epithelial cells (HT-29 and 5637 lineages) and characterizes the ultrastructure of AFP.

In conclusion, the emergence of novel E. coli variants resulting from the combination of multiple traits of already known pathotypes represents a new challenge in epidemiology and pathogenesis. In this aspect, although isolated from UTI, UPEC-46 presented important characteristics associated with atypical EAEC allowing its classification as a hybrid UPEC/EAEC strain. We also showed that AFP is essential for the AA phenotype on bladder and colorectal epithelial cells. However, its relationship with uropathogenesis and intestinal colonization needs to be better understood. Thus, future studies will be required to understand the prevalence of these hybrid-pathogenic E. coli strains and characterize in-depth the molecular basis associated with UTI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Karin Tegelkamp (University of Münster) for technical assistance.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Grants from São Paulo Research Foundation [FAPESP 2018/06610-9 and 2018/04144-0]; Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – Brasil (CAPES) – Finance Code 001; and Brazil Centre of the University of Münster, under the auspices of the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) and the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. This study has also received funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) grant number [01DN19008].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials. The NCBI accession numbers of genome sequences are PRJNA728080, JAHBCK000000000, NZ_JAHBCK010000003, NZ_JAHBCK010000004, and NZ_JAHBCK010000007, found in https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. The raw data used to generate graphs and phylogenetic analyses are available in the Butantan Institute Repository [https://repositorio.butantan.gov.br/handle/butantan/3890].

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Croxen MA, Law RJ, Scholz R, et al. Recent advances in understanding enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(4):822–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gomes TAT, Elias WP, Scaletsky IC, et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Braz J Microbiol. 2016;47(Suppl 1):3–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Smith JL, Fratamico PM, Gunther NW.. Extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2007;4(2):134–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Boxall MD, Day MR, Greig DR, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli isolated from travelers returning to the UK, 2015–2017. J Med Microbiol. 2020;69(7):932–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hebbelstrup Jensen B, Olsen KE, Struve C, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27(3):614–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Huang DB, Nataro JP, DuPont HL, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli is a cause of acute diarrheal illness: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(5):556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiang ZD, DuPont HL.. Etiology of travellers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2017;24(suppl_1):S13–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nataro JP, Kaper JB, Robins-Browne R, et al. Patterns of adherence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1987;6(9):829–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Navarro-Garcia F, Elias WP. A utotransporters and virulence of enteroaggregative E. coli. Gut Microbes. 2011;2(1):13–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nataro JP, Deng Y, Cookson S, et al. Heterogeneity of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence demonstrated in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1995;171(2):465–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bernier C, Gounon P, Le Bouguénec C. Identification of an aggregative adhesion fimbria (AAF) type III-encoding operon in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli as a sensitive probe for detecting the AAF-encoding operon family. Infect Immun. 2002;70(8):4302–4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Boisen N, Struve C, Scheutz F, et al. New adhesin of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli related to the Afa/Dr/AAF family. Infect Immun. 2008;76(7):3281–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Czeczulin JR, Balepur S, Hicks S, et al. Aggregative adherence fimbria II, a second fimbrial antigen mediating aggregative adherence in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65(10):4135–4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Dudley EG, Thomson NR, Parkhill J, et al. Proteomic and microarray characterization of the AggR regulon identifies a pheU pathogenicity Island in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61(5):1267–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Eslava C, Navarro-García F, Czeczulin JR, et al. Pet, an autotransporter enterotoxin from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1998;66(7):3155–3163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Henderson IR, Czeczulin J, Eslava C, et al. Characterization of pic, a secreted protease of Shigella flexneri and enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1999;67(11):5587–5596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jønsson R, Struve C, Boisen N, et al. Novel aggregative adherence fimbria variant of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2015;83(4):1396–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Nataro JP, Deng Y, Maneval DR, et al. Aggregative adherence fimbriae I of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli mediate adherence to HEp-2 cells and hemagglutination of human erythrocytes. Infect Immun. 1992;60(6):2297–2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sheikh J, Czeczulin JR, Harrington S, et al. A novel dispersin protein in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(9):1329–1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Morin N, Santiago AE, Ernst RK, et al. Characterization of the aggR regulon in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2013;81(1):122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Nataro JP, Yikang D, Yingkang D, et al. AggR, a transcriptional activator of aggregative adherence fimbria I expression in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(15):4691–4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Terlizzi ME, Gribaudo G, Maffei ME. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, et al. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(5):269–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7(12):653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(1):261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Khairy RM, Mohamed ES, Abdel-Ghany HM, et al. Phylogenic classification and virulence genes profiles of uropathogenic E. coli and diarrheagenic E. coli strains isolated from community acquired infections. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Spurbeck RR, Dinh PC Jr, Walk ST, et al. Escherichia coli isolates that carry vat, fyuA, chuA, and yfcV efficiently colonize the urinary tract. Infect Immun. 2012;80(12):4115–4122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Boll EJ, Overballe-Petersen S, Hasman H, et al. Emergence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli within the ST131 lineage as a cause of extraintestinal infections. mBio. 2020;11(3):e00353–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Freire CA, Santos ACM, Pignatari AC, et al. Serine protease autotransporters of Enterobacteriaceae (SPATEs) are largely distributed among Escherichia coli isolated from the bloodstream. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51(2):447–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Herzog K, Engeler Dusel J, Hugentobler M, et al. Diarrheagenic enteroaggregative Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection and bacteremia leading to sepsis. Infection. 2014;42(2):441–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lara FB, Nery DR, de Oliveira PM, et al. Virulence markers and phylogenetic analysis of Escherichia coli strains with hybrid EAEC/UPEC genotypes recovered from sporadic cases of extraintestinal infections. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mandomando I, Vubil D, Boisen N, et al. Escherichia coli ST131 clones harbouring aggR and AAF/V fimbriae causing bacteremia in Mozambican children: emergence of new variant of fimH27 subclone. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(5):e0008274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nascimento JAS, Santos FF, Valiatti TB, et al. Frequency and diversity of hybrid Escherichia coli strains isolated from urinary tract infections. Microorganisms. 2021;9(4):693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Nazemi A, Mirinargasi M, Merikhi N, et al. Distribution of pathogenic genes aatA, aap, aggR, among uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) and their linkage with stbA gene. Indian J Microbiol. 2011;51(3):355–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Park HK, Jung YJ, Chae HC, et al. Comparison of Escherichia coli uropathogenic genes (kps, usp and ireA) and enteroaggregative genes (aggR and aap) via multiplex polymerase chain reaction from suprapubic urine specimens of young children with fever. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2009;43(1):51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Toval F, Köhler CD, Vogel U, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from hospital inpatients or outpatients with urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52(2):407–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Flament-Simon SC, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, García V, et al. Clonal structure, virulence factor-encoding genes and antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli, causing urinary tract infections and other extraintestinal infections in humans in Spain and France during 2016. Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9(4):161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Boll EJ, Struve C, Boisen N, et al. Role of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in uropathogenesis. Infect Immun. 2013;81(4):1164–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Olesen B, Scheutz F, Andersen RL, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O78:H10, the cause of an outbreak of urinary tract infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(11):3703–3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Abe CM, Salvador FA, Falsetti IN, et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) strains may carry virulence properties of diarrhoeagenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2008;52(3):397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Nunes KO, Santos ACP, Bando SY, et al. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli with uropathogenic characteristics are present in feces of diarrheic and healthy children. Pathog Dis. 2017;75(8). DOI: 10.1093/femspd/ftx106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gomes TAT, Abe CM, Marques LR. Detection of HeLa cell-detaching activity and alpha-hemolysin production in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains isolated from feces of Brazilian children. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33(12):3364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Santos ACM, Santos FF, Silva RM, et al. Diversity of hybrid- and hetero-pathogenic Escherichia coli and their potential implication in more severe diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020a;10:339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 27th ed. Tertel ML, Christopher JP, and Martin L , et al. eds. Wayne PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cravioto A, Gross RJ, Scotland SM, et al. An adhesive factor found in strains of Escherichia coli belonging to the traditional infantile enteropathogenic serotypes. Curr Microbiol. 1979;3(2):95–99. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Munhoz DD, Nara JM, Freitas NC, et al. Distribution of major pilin subunit genes among atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and influence of growth media on expression of the ecp operon. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Sheikh J, Hicks S, Dall’Agnol M, et al. Roles for Fis and YafK in biofilm formation by enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 2001;41(5):983–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Culler HF, Mota CM, Abe CM, et al. Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains form biofilm on abiotic surfaces regardless of their adherence pattern on cultured epithelial cells. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:845147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Stepanovic S, Vukovic D, Dakic I, et al. A modified microtiter-plate test for quantification of staphylococcal biofilm formation. J Microbiol Methods. 2000;40(2):175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Castonguay MH, van der Schaaf S, Koester W, et al. Biofilm formation by Escherichia coli is stimulated by synergistic interactions and co-adhesion mechanisms with adherence-proficient bacteria. Res Microbiol. 2006;157(5):471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Römling U, Bokranz W, Rabsch W, et al. Occurrence and regulation of the multicellular morphotype in Salmonella serovars important in human disease. Int J Med Microbiol. 2003;293(4):273–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pugsley AP, Oudega B. Methods for studying colicins and their plasmids. In: Hardy KG, editor. Plasmids: a practical approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1987. p. 105–161. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ruiz RC, Melo KC, Rossato SS, et al. Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli secretes plasmid encoded toxin. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:896235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Birnboim HC, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7(6):1513–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Moran RA, Anantham S, Hall RM. An improved plasmid size standard, 39R861. Plasmid. 2019;102:6–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lima MP, Yamamoto D, Santos ACM, et al. Phenotypic characterization and virulence-related properties of Escherichia albertii strains isolated from children with diarrhea in Brazil. Pathog Dis. 2019;77(2):ftz014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Wick RR, Judd LM, Gorrie CL, et al. Unicycler: resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):e1005595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, et al. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(8):1072–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Carver T, Thomson N, Bleasby A, et al. DNAPlotter: circular and linear interactive genome visualization. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(1):119–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(14):2068–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Beghain J, Bridier-Nahmias A, Le Nagard H, et al. Clermont Typing: an easy-to-use and accurate in silico method for Escherichia genus strain phylotyping. Microb Genom. 2018;4(7):e000192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1355–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(7):3895–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2640–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Joensen KG, Tetzschner AM, Iguchi A, et al. Rapid and easy in silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53(8):2410–2426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Croucher NJ, Page AJ, Connor TR, et al. Rapid phylogenetic analysis of large samples of recombinant bacterial whole genome sequences using Gubbins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(3):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W256–W259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Leimbach A. ecoli_VF_collection: v0.1. Zenodo. 2016b. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.56686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Leimbach A. bac-genomics-scripts: Bovine E. coli mastitis comparative genomics edition. Zenodo. 2016a. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.215824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Penfold RJ, Pemberton JM. An improved suicide vector for construction of chromosomal insertion mutations in bacteria. Gene. 1992;118(1):145–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler AA. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering: transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Nat Biotechnol. 1983;1(9):784–791. [Google Scholar]

- [73].Elias WP Jr, Czeczulin JR, Henderson IR, et al. Organization of biogenesis genes for aggregative adherence fimbria II defines a virulence gene cluster in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(6):1779–1785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chang AC, Cohen SN. Construction and characterization of amplifiable multicopy DNA cloning vehicles derived from the P15A cryptic miniplasmid. J Bacteriol. 1978;134(3):1141–1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Evans DG, Silver RP, Evans DJ Jr, et al. Plasmid-controlled colonization factor associated with virulence in Escherichia coli enterotoxigenic for humans. Infect Immun. 1975;12(3):656–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227(5259):680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Johnson JR, Kuskowski MA, Owens K, et al. Phylogenetic origin and virulence genotype in relation to resistance to fluoroquinolones and/or extended-spectrum cephalosporins and cephamycins among Escherichia coli isolates from animals and humans. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(5):759–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Lang C, Fruth A, Holland G, et al. Novel type of pilus associated with a Shiga-toxigenic E. coli hybrid pathovar conveys aggregative adherence and bacterial virulence. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2018;7(1):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Chaudhuri RR, Sebaihia M, Hobman JL, et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative metabolic profiling of the prototypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strain 042. PLoS One. 2010;5(1):e8801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Dias RCB, Tanabe RHS, Vieira MA, et al. Analysis of the virulence profile and phenotypic features of typical and atypical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC) isolated from diarrheal patients in Brazil. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Santos ACM, Silva RM, Valiatti TB, et al. Virulence potential of a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli strain belonging to the emerging clonal group ST101-B1 isolated from bloodstream infection. Microorganisms. 2020b;8(6):827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Santos AC, Zidko AC, Pignatari AC, et al. Assessing the diversity of the virulence potential of Escherichia coli isolated from bacteremia in São Paulo, Brazil. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46(11):968–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Binns MM, Mayden J, Levine RP. Further characterization of complement resistance conferred on Escherichia coli by the plasmid genes traT of R100 and iss of ColV,I-K94. Infect Immun. 1982;35(2):654–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Biran D, Rosenshine I, Ron EZ. Escherichia coli O-antigen capsule (group 4) is essential for serum resistance. Res Microbiol. 2020;171(2):99–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Köhler CD, Dobrindt U. What defines extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli? Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301(8):642–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Lüthje P, Brauner A. Virulence factors of uropathogenic E. coli and their interaction with the host. Adv Microb Physiol. 2014;65:337–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Stork C, Kovács B, Rózsai B, et al. Characterization of asymptomatic bacteriuria Escherichia coli isolates in search of alternative strains for efficient bacterial interference against uropathogens. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Smajs D, Micenková L, Smarda J, et al. Bacteriocin synthesis in uropathogenic and commensal Escherichia coli: colicin E1 is a potential virulence factor. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10(1):288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]