Dear Editor,

With interest we read the recent publication by Levin and colleagues reporting recommendations from the International Society of Nephrology consensus meeting on defining kidney failure in clinical trials. In this manuscript the authors urge the nephrology community to standardize kidney endpoints in clinical trials to “enhance the ability to conduct clinical trials, harmonize and compare results”(1). We fully support the conclusion drawn and feel that their message is perfectly illustrated by a recent example.

Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors have received a great deal of attention due to their kidney protective actions. In the dedicated chronic kidney disease (CKD) trials CREDENCE and DAPA-CKD, attenuation of hard kidney outcomes including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), renal replacement therapy/dialysis or renal death were demonstrated by this drug class in people with or without diabetes. First clues for kidney protection induced by these drugs, however, came from cardiovascular outcome trials involving patients at high cardiovascular disease risk, but with relatively low kidney disease risk. These trials, as indicated below, heavily relied on surrogate kidney endpoints. As such, 40%, 50% or 57% decline in eGFR were used and combined with low-prevalence hard kidney endpoints, including renal replacement therapy, to form composite outcomes.

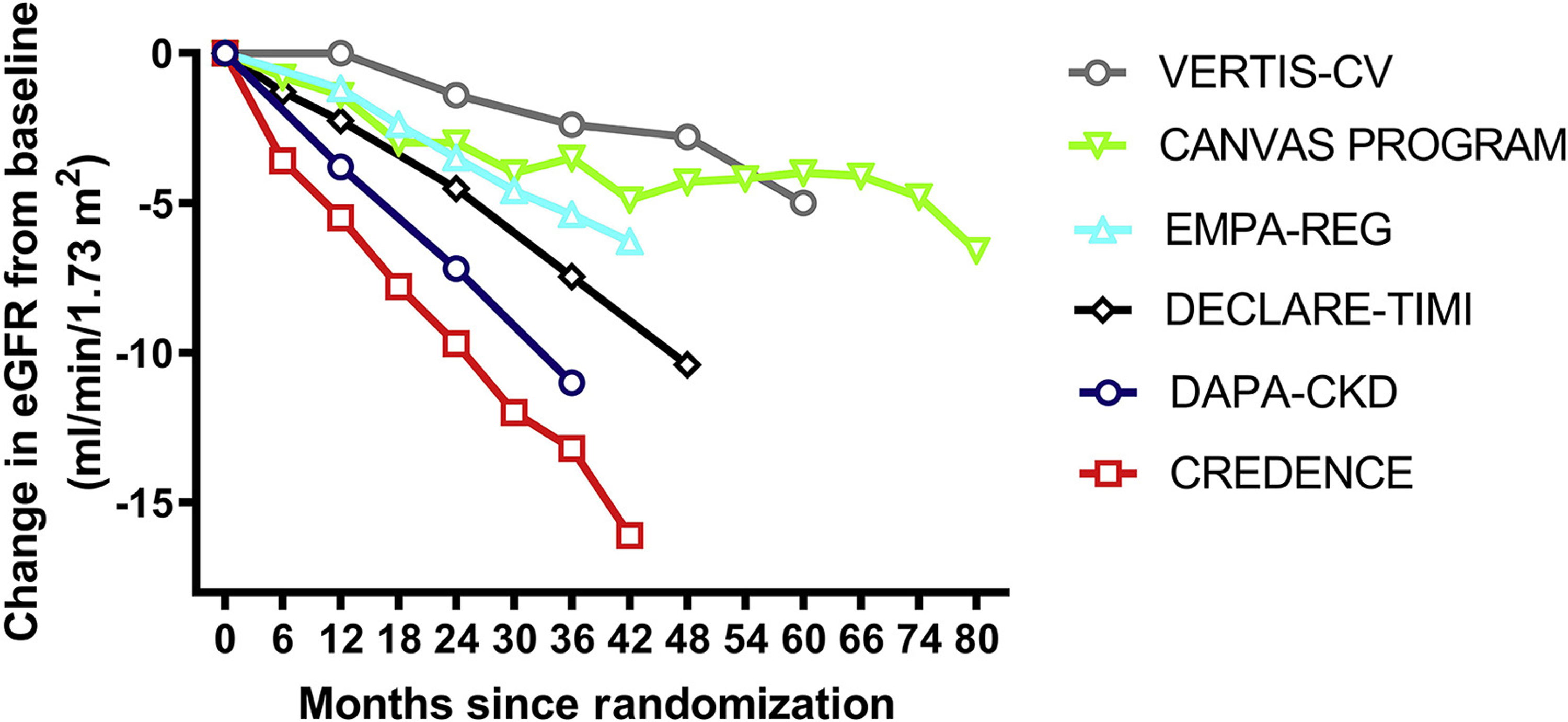

In the first three large cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) including EMPA-REG OUTCOME(2), CANVAS Program(3) and DECLARE-TIMI(4), renal composite outcomes were significantly improved, although it should be noted that in each of these studies, the composite definitions were different. However, in a fourth recent trial, VERTIS CV, with ertugliflozin, the impact on the key kidney composite did not reach statistical significance (hazard ratio 0.81, 95% CI 0.63–1.04)(5). This led to speculation that ertugliflozin might have different kidney effects compared to other SGLT2 inhibitors, although based on chemical structure, PK-PD data as well as mechanistic evidence, this assumption does not seem plausible. A closer look at the composite revealed that the threshold for eGFR decline chosen (≥57%, based on doubling of serum creatinine) was greater than what most other studies reported, did not have to be sustained, and did not require that the eGFR decline fall below 60 or 45 ml/min/1.73m2. In addition, across the CVOTs, the rate of eGFR decline was smallest in the placebo group included in VERTIS-CV, suggesting lower overall kidney risk at baseline (Figure 1). Finally, similar to other CVOT results, when the definition of kidney function decline was set at ≥40% in VERTIS CV, ertugliflozin treatment significantly reduced kidney function loss and the kidney composite consistently with other SGLT2 inhibitors(6).

Figure 1.

eGFR of slopes of the placebo arms in the major trials conducted with SGLT2 inhibitors in cardiovascular outcome studies and dedicated kidney outcome trials. Change over time was estimated from eGFR curves of published individual trials, since some numerical data were not available.

A similar example was the EMPEROR-Reduced trial that reported a benefit of empagliflozin in subjects with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. A prespecified composite kidney outcome seemed to be of greater benefit as compared to that seen in the previously published DAPA-HF. However, when kidney composite definitions were aligned, no differences were observed between the studies.

Given the complexity and length of time required to perform kidney outcome trials, the use of surrogate outcomes – such as significant eGFR loss – in patients with lower baseline kidney risk is justified. However, as illustrated by the SGLT2 inhibitor trial literature, standardization around the selection and reporting of kidney outcomes is critical to establish kidney protective effects with novel therapies. Based on existing literature and consensus statements, eGFR decline of ≥40% merits uniform use across clinical trials.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

DHVR has acted as a consultant and received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi and AstraZeneca and has received research operating funds from Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly Diabetes Alliance, AstraZeneca and Novo Nordisk; all honoraria are paid to his employer (AUMC, location VUMC). Dr. Bjornstad reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Bristol Meyer Squibb, grants and personal fees from Boehringer-Ingelheim, personal fees from Eli-Lilly, grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisk, personal fees and non-financial support from Sanofi, personal fees from XORT, grants and personal fees from Horizon Pharma, outside the submitted work; .HJLH is consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chinook, CSL Pharma, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mundi Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novo Nordisk, and Retrophin. He received research support from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen. FP reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Astra Zeneca, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Novo Nordisk, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants and personal fees from Amgen, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from MSD, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Eli Lilly, personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. D.Z.I.C has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly, Merck, AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, Abbvie, Janssen, Bayer, Prometic, BMS, Maze and Novo-Nordisk and has received operational funding for clinical trials from Boehringer Ingelheim-Lilly, Merck, Janssen, Sanofi, AstraZeneca and Novo-Nordisk.

References:

- 1.Levin A, Agarwal R, Herrington WG, Heerspink HL, Mann JFE, Shahinfar S, et al. International consensus definitions of clinical trial outcomes for kidney failure: 2020. Kidney Int [Internet] 2020. Oct;98(4):849–59. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0085253820309054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, et al. Empagliflozin and Progression of Kidney Disease in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2016. Jul 28;375(4):323–34. Available from: 10.1056/NEJMoa1515920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perkovic V, de Zeeuw D, Mahaffey KW, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: results from the CANVAS Program randomised clinical trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet] 2018. Sep;6(9):691–704. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213858718301414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosenzon O, Wiviott SD, Cahn A, Rozenberg A, Yanuv I, Goodrich EL, et al. Effects of dapagliflozin on development and progression of kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the DECLARE–TIMI 58 randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol [Internet] 2019. Aug;7(8):606–17. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2213858719301809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, Mancuso J, Huyck S, Masiukiewicz U, et al. Cardiovascular Outcomes with Ertugliflozin in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2020. Oct 8;383(15):1425–35. Available from: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Data presented at symposium (S16) Vertis CV outcome; EASD 2020. (virtual meeting).