Abstract

Understanding the cancer stem-cell (CSC) landscape in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is desperately needed to address treatment resistance and identify novel therapeutic approaches. Patient derived DIPG cells demonstrated heterogeneous expression of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) and CD133 by flow cytometry. Transcriptome-level characterization identified elevated mRNA levels of MYC, E2F, DNA damage repair (DDR) genes, glycolytic metabolism and mTOR signaling in ALDH+ compared to ALDH- supporting a stem-like phenotype and indicating a druggable target. ALDH+ cells demonstrated increased proliferation, neurosphere formation and initiated tumors that resulted in decreased survival when orthotopically implanted. Pharmacological MAPK/PI3K/mTOR targeting downregulated MYC, E2F and DDR mRNAs and reduced glycolytic metabolism. In vivo PI3K/mTOR targeting inhibited tumor growth in both flank and an ALDH+ orthotopic tumor model likely by reducing cancer stemness. In summary, we describe existence of ALDH+ DIPGs with proliferative properties due to increased metabolism, which may be regulated by the microenvironment and likely contributing to drug resistance and tumor recurrence.

Keywords: DIPG, Aldehyde dehydrogenase, CD133, PI3K, mTOR, MAPK, cancer stem cells

Introduction

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a uniformly lethal pediatric brain tumor that arises in the midline brain during adolescence [1, 2]. DIPG is the most common and aggressive pediatric brain stem cancer with a median 5-year survival of 1% [1]. The sensitive location and diffuse nature of the tumor makes full resection unfeasible therefore targeted radiation has been the standard therapy to alleviate pain and temporarily preserve neurological function [1, 3]. More than 250 clinical trials testing different chemotherapeutic regimens and combinations with radiation have only marginally increased survival over existing radiotherapy; this lack of clinical efficacy has prompted recent research interest in the development of molecular targeted therapies for DIPG [2, 3].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been increasingly identified in a number of malignancies over the past decade including high-grade gliomas [4–6]. CSCs can be characterized by their unlimited self-renewal properties, ability to produce differentiated tumor cells, high tumorgenicity and are thought to drive drug resistance [7, 8]. Evidence suggests that CSCs maintain a different metabolic phenotype than non-CSC differentiated bulk tumor cells which may drive proliferation and evasion of apoptosis [9]. Specifically, in glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), the cell surface stem cell marker CD133 marks brain tumor-initiating cells (BTICs) where an increase of CD133+ cells in brain malignancy correlates with elevated aggressiveness, higher tumor grade and tumor recurrence [10]. In DIPG, CD133+ cells have been identified and their neural stem cell-like phenotype has been reported [11]. However, CD133 has shown to identify only a subset of self-renewing cancer-initiating cells in glioma [12] and CD133 is also expressed in normal neural cells [13] necessitating the evaluation of other CSC markers. Aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) is highly expressed in many malignancies including gliomas and is implicated in increased cell proliferation, maintenance of CSC properties and to negatively impact patient survival [14, 15]. ALDH isotype ALDH1, specifically ALDH1A, is predominantly found in tumor-initiating cells in gliomas [16]. Expression of stem cell factors CD133 and ALDH are correlated in multiple brain malignancies resulting in double positive CD133+/ALDH+ cells, however it remains to be investigated if these cells are particularly aggressive, initiate tumor recurrence or contribute to treatment resistance in DIPG [17].

Mutations in histone 3, H3.3 and H3.1/2 K27M as well as G34R/V, result in a broad loss of di- and tri-methylation leading to elevated acetylation, un-folding of the chromatin structure and increased aberrant transcription [18, 19]. In DIPG, important work has elucidated mutations in genes encoding histone 3, HIST1H3B (H3.1), HIST1H3A (H3.2) and H3F3A (H3.3), which exhibit tumors with distinct active regulatory elements, oncogenic reprogramming and result in heterogeneous enhancer architecture dependent on the oncohistone variant [20]. In particular, the H3.3K27M variant have highly accessible enhancer elements regulating retinoic acid (RA) receptors-mediated signaling compared to H3.1K27M variants [20] where ALDH is a key enzyme [21]. Overexpression of RA signaling has been observed to coincide with overexpression of ALDH+ CSCs [22] and therefore could explain increased aggressiveness and treatment resistance observed clinically in the H3.3K27M mutation in DIPG [23]. In addition to mutations in histone H3.1 or H3.3 (80%), ongoing characterization of the genomic landscape of DIPG has led to identifications of co-occurring mutations in Activin A receptor type I (ACVR1) (20–32%), TP53 (22–40%), PDGFRA (32%), PI3KR1/PIK3CA (15%) [3, 24] and amplification of PDGFR resulting in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/ mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway activation in 50% of DIPG tumors [2, 24]. Thus, it comes with no surprise that pre-clinical single agent targeting of PI3K/mTOR pathway in DIPG have appeared promising to date [2, 25].

However, single agent therapy targeting PI3K/mTOR pathway in other malignancies has produced insufficient long-term clinical response to date [2, 26–29]. The lack of long-term response stems from acquired resistance occurring in tumors as a result of targeted single agent therapy [30, 31] and a compensatory upregulation in associated MAPK pathway following PI3K inhibition due to cross talk [30–34]. Meta-analysis of 1000 high grade pediatric glioma and DIPG samples revealed alterations in the MAPK pathway as well as the PI3K pathway indicating additional druggable targets [24]. Dual inhibition of MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathway in DIPGs has shown to induce synergistic antitumor effects in cells by inhibiting growth, inducing death and therefore may be efficacious in reducing tumor resistance [2, 35].

We posit the high rate of relapse in DIPG patients may be linked to the presence of a resistant CSC, and targeting this sub-population is of particular interest to advance effective tumor eradication. The aim of this study was to determine whether DIPGs, like other malignancies of the brain, harbor aggressive, stem-like subpopulations needing to be considered for the design of effective therapies. Furthermore, we sought to determine whether targeted therapy inhibiting the MAPK and PI3K/mTOR signaling axes, individually and together, show promise in targeting DIPG cells in particular the stem-like ALDH+ subpopulations, ultimately leading to improvements in patient outcome by addressing treatment resistance in this disease.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Human SU-DIPG IV,SU-DIPG XIII cell lines [36] were kindly provided by Drs. Maachani and Souweidane, SU-DIPG 29 by Dr. Monje and HSJD-DIPG 007 (DIPG 007) [37] by Dr. Venneti. SU-DIPG XIII were infected with FUGW plasmid expressing luciferase and GFP [38]. HSJD-DIPG 007 (DIPG 007) cells was infected with pLVX-IRES-mCherry to obtain DIPG 007 cherry positive expressing cells [39]. Cells were maintained in: Tumor Stem Neurobasal-A medium mixed 1:1 with DMEM F-12 supplemented 10 mM HEPES, 100 mm Sodium Pyruvate, Non-essential Amino Acids, GlutaMAX-I supplement, 100X Antibiotic-Antimycotic, B27(-A) (all reagents from Invitrogen) and: 20 ng/ml of human-FGF (20ng/ml), human-EGF and human PDGF-AB (all from Shenandoah Biotech) each as well as 10 ng/ml heparin (STEMCELL Technologies). Cells obtained from other institutions were not re-authenticated in our lab. Human SF7761 and SF8628 cell lines, obtained from Millipore were cultured according to manufacturer. Each lot of Millipore’s cells was genotyped by STR analysis to verify the unique identity of the cell line. For 2D proliferation assays, DIPG 007 cells were maintained in Tumor Stem Neurobasal-A medium mixed 1:1 with DMEM F-12, 10mM. HEPES, 100mm Sodium Pyruvate, Non-essential Amino Acids, GlutaMAX-I, 100X Antibiotic-Antimycotic and 10% FBS. Neurospheres were dissociated in TrypLE Express (Thermo Fisher) and 2D cultures with Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco). All cell lines were regularly checked for mycoplasma contamination using MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza). Cell lines were cultured for a period of ~ 2 month after which they were replaced by new thaws.

Therapeutics

PD0325901 (PD-901), GSK2126458 (GSK-458) and GDC-0084 were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). Stock solutions were prepared in DMSO. Control wells were incubated with media containing 0.1% DMSO carrier solvent.

DIPG mouse models and in vivo drug treatment

All animals were maintained in accordance with the University of Michigan’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines approved protocol (UCUCA PRO00008646).

Orthotopic xenograft model:

DIPG 007-Luciferase expressing cells sorted for ALDH (+/−) or left unsorted were intracranially implanted into five-to-seven-week old male NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIl2rgtm1WjlISzJ (NSG, Jackson Laboratory) mice using a protocol adapted from Monje et al. [11]. In brief, the skull was exposed by a 1 cm incision to expose the area of the lambdoid suture. A small 26 g burr hole using an electric drill was made 1 mm to the right of the sagittal suture and 0.8 mm posterior to the lambdoid suture. Using a stereotactic setup, 1×105 cells in 2 μl of serum free media were implanted 5 mm deep from the skull surface at a rate of 1 μl per minute using a 26-gauge Hamilton syringe. Mice were monitored for tumor growth using bioluminescence imaging and body weight changes. Mice implanted with 1×105 ALDH+ or ALDH- DIPG-007-luc cells were randomly assigned to a GDC-0084 (ALDH+: n=4; ALDH-: n=3) or VEH control (ALDH+: n=2; ALDH-: n=2) treated group at day ~80 post-implantation. GDC-0084 was administered via oral gavage at 10 mg/kg, daily for 14 days. In vivo BLI was acquired before treatment initiation and at day 14.

Flank xenograft model:

four-six-week old male NSG mice (Jackson Laboratory) were inoculated with 2×106 SF8628 cells in 1:1 suspension of serum free media with Matrigel (BD Bioscience) via subcutaneous injection in right and left flanks. Tumor-bearing mice were randomly assigned to GSK-458 (n=6, 8 tumors) or vehicle control (VEH, n=4, 6 tumors) treated groups. Tumor progression was monitored bi-weekly via caliper and treatment initiated via oral gavage at a 3 mg/kg dose daily for 14 consecutive days when tumor volume reached ~100–150 mm3.

For all drug treatment studies with GSK-458 or GDC-0084, the vehicle control formulation was as follows: 2% DMSO, 40% PEG, 2% Tween-80 in 1xPBS.

Immunoblot Analysis

Cells were seeded 24 hours prior to treatment and incubated with the respective inhibitors for 2 hours or as otherwise indicated. Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (Thermo Fisher) supplemented with protease inhibitors (Complete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail, Roche) and phosphatase inhibitors (PhosSTOP, Roche). Western blotting was performed as previously described [32]. Primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling against pErk1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), pAKT (S473), total ERK, AKT and secondary HRP-conjugated antibodies from (Jackson ImmunoResearch). ECL-Plus substrate (BioRad) and BioRad ChemiDoc MP imager were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Reverse Phase Protein arrays

SU-DIPG XIII cells were treated for indicated times and cell lysates were prepared in RPPA lysis buffer (1% Triton X-100, 50mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150mM NaCl, 1.5mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 100mM NaF, 10mM Na pyrophosphate, 1mM Na3VO4, 10% glycerol, containing freshly added protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche) and 60 ug of protein was submitted for RPPA analysis. RPPA was performed by RPPA Core at MD Anderson Cancer Center. For RPPA description, materials and methods as well as RPPA core publication refer to https://www.mdanderson.org/research/research-resources/core-facilities/functional-proteomics-rppa-core.html.

Aldefluor assay and CD133 flow cytometry

The Aldefluor kit (STEMCELL Technologies) was used to identify cell populations with high ALDH enzymatic activity according to manufacturer’s recommendations. For CD133 co-staining APC-conjugated CD133 (BD Pharmingen) or APC-conjugated isotype control IgG1 was used (BD Pharmingen). Cells were analyzed on Synergy Head cell sorter at the UMMS Flow Cytometry Core and FCS Express 7 cytometry software. In all cases debris, dead cells, and doublets were gated out prior to sorting to ensure purity. Sorted cells were counted using trypan blue to ensure desired number of live cells. When cells were sorted for orthotopic implantation and for the Bru-sequencing experiment, top 10% of ALDH+ and the bottom 10% of ALDH- cells were included in the sort.

Proliferation assays

2500 cells/well cells were plated in 96-well plates. Cell viability was assessed using a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent viability assay (Promega) or AlamarBlue Cell Viability assay (Invitrogen) and Envision multi-label plate reader (Perkin Elmer) at 24, 48 and 96 hours post treatment according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Assays were conducted at least three times with inhibitors each run in triplicate.

Neurosphere assay

Neurosphere size and formation was evaluated for 10 days by using 250,000 cells sorted and treated cells after plating in flasks and analyzed by taking images of three different field of views per condition on day 3, 7 and 10. Neurosphere size and number was quantified in ImageJ software and averaged over the three fields of view for four independent experiments as performed by three different raters.

Clonogenic Assay

SF8628 cells were stained with Aldelfluor and FACS sorted, live/dead cells were counted to ensure viability following sorting and 500 ALDH+ and ALDH- cells per well were plated in triplicates. On day 14, media was removed and colonies were stained using crystal violet (0.1% in 20% methanol; Sigma-Aldrich). Colonies were manually counted if they contained >50 cells as assessed by microscopy.

Bromouridine-sequencing (Bru-seq)

SU-DIPG XIII cells were treated with 100 nM of PD-901, 100 nM of GSK-458, 50 nM PD-901 + 50 nM GSK-458 (combination) or equimolar DMSO for 2 hours. Bromouridine sequencing (Bru-Seq) was performed as previously described [32, 40]. cDNA libraries were sequenced at the University of Michigan Sequencing Core using an Illumina (San Diego, CA) HiSeq 2500 and NovaSeq sequencers as previously described [40, 41]. The sequencing reads were mapped using STAR onto the hg38 human reference genome and analyzed using Gencode 27 gene annotation. GSEA of rLogFC-ranked gene lists was performed to identify up- and downregulated gene sets. The only cut-off used on the gene set was that genes had to have >10 normalized counts. The gene sets were obtained from version 4.0 of the Molecular Signatures Database (http://www.broadinstitute. org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp). Gene sets with FDR corrected P values <0.01 were considered to be significantly enriched and were used in the analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

RNA was extracted using QIAshredder and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcription performed with QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen) using 1–1.5 μg RNA. RT-qPCR was performed with QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) on Eppendorf Realplex 2 Master cycler. Samples were run in technical replicates. RT-qPCR primers are listed in Supplemental Table S4.

Histology

Formalin fixed tissue was paraffin embedded and sectioned at the University of Michigan Cancer Center core facility. H&E and antibody stains were performed using standard IHC/IF protocols with the following antibodies: anti-Nestin (Chemicon), anti-Ki67 (DAKO), anti-ALDH1 (BD Transduction Labs) or anti-H3K27M (Sigma Aldrich) and developed with a biotinylated-secondary antibody by a peroxidase HRP system (Vectastain Elite ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) and DAB substrate (Vector Laboratories) following manufacturer’s instructions. Anti-H3K27M was developed using a fluorescent-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary (Alexa Fluor 594, Invitrogen). Sections were counterstained CytoSeal 60 (Thermo Scientic) or ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent (Life Technologies). Microscopy was performed with an Evos FLc microscope (Life Technologies). Quantification was performed using Image J software of three separate fields of view of three separate sections. All images were scored by 3 different raters. One-way ANOVA were performed to obtain p values for multiple comparisons from Tukey’s post-hoc tests.

In vivo and ex vivo bioluminescent imaging

In vivo bioluminescence imaging (BLI) was performed using IVIS Spectrum Imaging System (PerkinElmer) according to manufacturer using intraperitoneal injection of 100 μl of D-luciferin (40 mg/mLstock, Promega). Quantification of total flux (photons per second, p/s/cm3) was performed at indicated time points. For ex vivo BLI, mice were injected with same concentration of luciferin pior to sacrifice and extraction of the brain. BLI was acquired using IVIS Lumina LT Series III (Perkin Elmer).

BOILED-Egg predictive model for drug delivery

BOILED-Egg predictive model (SwissADME, http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php, [42]) was used to predict the blood brain barrier (BBB) penetration and gastrointestinal (GI) absorption of GSK-458 and GDC-0084. The molecular structure of each molecule was submitted as a simplified molecular-input line-entry system (SMILES) into the online database where evaluation of BBB penetration and gastrointestinal absorption, a function of the position of the molecule in the WLOGP versus TPSA referential, was plotted. The white region is a high probability that the molecule will be absorbed by the GI tract and the yellow region (yolk) is a high probability of BBB penetration.

Cryo-Fluorescence Tomography

Murine brain from mCherry labeled DIPG 007 ALDH+ implanted cells was removed on day 91 post implantation, resected immediately on dry ice and shipped to Emit Imaging (Boston, MA, USA) where brain was embedded in OCT. Imaging was performed on an Xerra Imaging System (EMIT Imaging). Cryo-Fluorescence Tomography (CFT) was conducted automatically in the Emit unit using a minimal field of view and 30 μm thick sections. Brightfield images and cherry fluorescence was acquired using an automatically determined exposure: 1) excitation 470, emission filter 511/20, average exposure 98 ms; 2) excitation 555, emission filter 585/11, average exposure 25 ms; 3) excitation 555, emission filter 610/10, average exposure 226 ms.

Single cell RNA sequencing analysis

Primary H3K27M-glioma biopsy samples were collected and processed for single cell RNA sequencing as previously described [51]. The single cell RNAseq data is publicly available at GEO or the Broad Institute Single-Cell Portal (GSE102130 / https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP147/single-cell-analysis-in-pediatric-midline-gliomas-with-histone-h3k27m-mutation ). Data was read and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Immune cells were filtered from the dataset and identified based on expression of cell type specific immune markers (T cell: “CD3E”, “CD3D”, “CD3G”, “CD8A”, “CD8B”, “CD4”, “FOXP3”, Myeloid: “CD14”, “CXCR2”, “ITGAM”, “EMR1”, “MNDA”, Dendritic cell: “CD14”, “ITGAM”, “ITGAX”, “CX3CR1”, B cell: “MS4A1”, “CD19”, “CD79A”, “CD79B”, “IGJ”). Average expression of ALDH genes were calculated per immune cell population.

Statistics

All statistics were performed using Graphpad Prism v7 (GrpahPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical analysis is presented of no fewer than three independent experiments and data represents mean ± SEM. p-values were calculated using unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test. For survival analysis, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated and log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests were used to compare survival curves. In all cases, alpha was set at p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Heterogeneity in stem cell marker expression of Aldehyde dehydrogenases and CD133 among DIPGs.

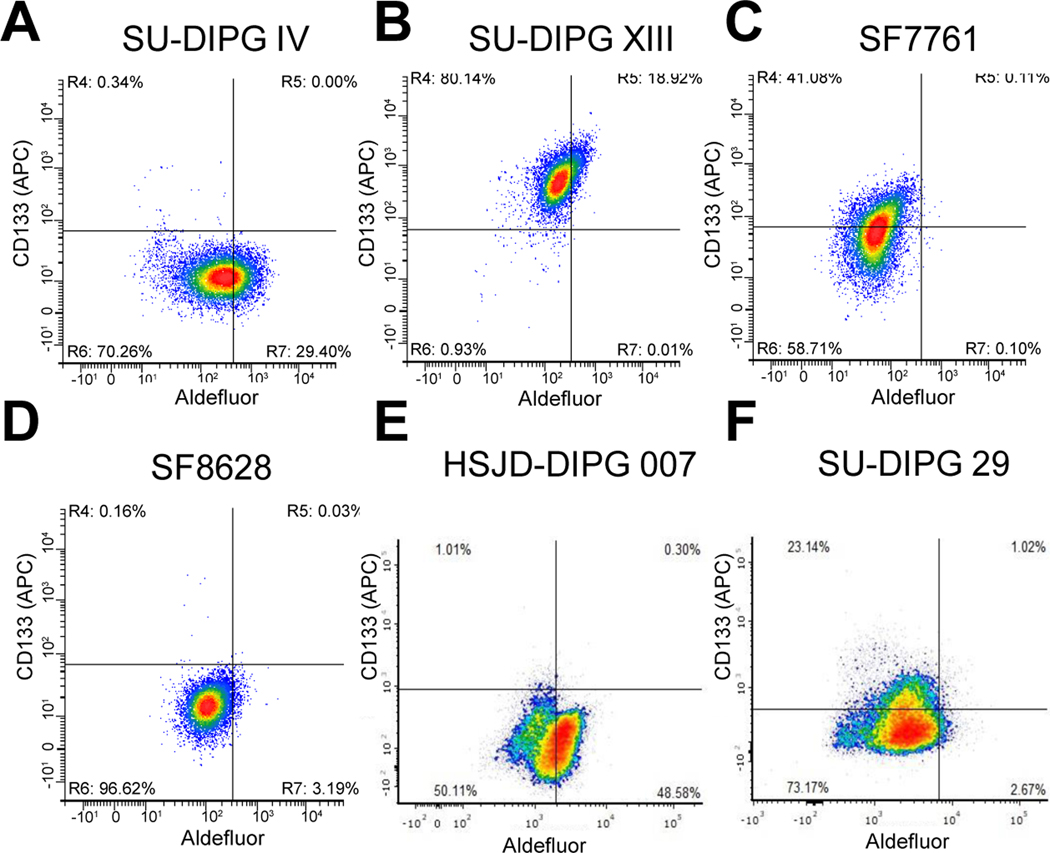

DIPGs are very aggressive childhood gliomas and new therapies are desperately needed. In other forms of glioma, stem cells have been shown to contribute to aggressiveness and recurrence driving the development of novel therapies to attack this “stem cell niche”. Here we sought to characterize stem cell marker expression of six DIPG cell lines which included cells derived from surgical biopsy with no prior known treatment or early post-mortem autopsy where treatment including radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Cells either harbored the H3.1K27M mutation or the H3.3K27M mutation (Supplemental Table 1) and were evaluated for expression of known glioma stem cell markers, ALDH and CD133 (Supplemental Table 1 and Figure 1A–F).

Figure 1: Heterogeneity of stem cell marker expression among DIPGs.

A.-F. Flow cytometry of SU-DIPG IV, SU-DIPG XIII, SF8628, SF7761, HSJD-DIPG 007 and SU-DIPG 29, respectively, stained with Aldefluor and APC conjugated CD133 antibody. Representative images are depicted of one of three independent experiments.

ALDH positive (ALDH+) cells were identified utilizing Aldefluor staining assay and CD133 positive cells with an CD133 antibody by flow cytometry. We identified high ALDH expression in SU-DIPG IV, SU-DIPG XIII and HSJD-DIPG 007 (DIPG 007) lines (Figure 1A, B and E), but low expression in the SF7761 and SF8628 lines and SU-DIPG 29 line (Figure 1C, D and F). Interestingly, high CD133 expression was observed in SU-DIPG XIII, SF7761 and SU-DIPG 29 DIPG lines (Figure 1B, C and F). Double positive populations (ALDH+/CD133+) were only detected in the SU-DIPG XIII cells. These results suggest existence of a cancer stem cell populations within DIPG tumors and are indicative of tumor heterogeneity within DIPG.

ALDH positive DIPG cells exhibit a more “stem-like” transcriptome profile.

Due to the transient nature and high cellular plasticity described for stem-like cells, a nascent RNA sequencing technology using bromouridine labeling and RNA sequencing (Bru-Seq) was performed to gain insight into transcriptomic differences between ALDH+ and ALDH- DIPG cells. We chose the SU-DIPG XIII cells for this approach due to their high level of aldehyde dehydrogenase and their double positivity with CD133 cell surface expression (Figure 1B). In brief, SU-DIPG XIII cells were incubated for 30 min with bromouridine (BrU) to label nascent RNA, were then stained with Aldefluor reagent and cells were sorted using FACS into ALDH+/− populations. Total RNA was purified from the two different fractions and nascent RNA was captured using anti-BrdU antibodies conjugated to magnetic beads. Nascent RNA was then converted into a cDNA library, sequenced as previously described [32, 40] and mapped to the human hg38 reference sequence as (Figure 2A). Bru-sequencing data revealed that ALDH+ cells exhibit significantly induced or increased gene sets in Hallmark pathways related to E2F targets, MYC targets and DNA damage repair (DDR) (Figure 2B). Specifically, we observed homologous recombination genes RECQL4, RAD51, RFC2, and BRCA1 upregulated but the individual genes did not reach statistical significance (Supplemental Table 2). We found that ALDH+ cells exhibit higher expression of canonical “stem-cell” reprogramming genes e.g. E2F1/2, OLIG1, NES, and MYC (Supplemental Table 2) which was verified using RT-qPCR (Figure 2C). This demonstrates that the ALDH+ DIPG cell population exhibits a genetic profile capable of stem cell maintenance, observed in other forms of brain malignancies [17]. Bru-sequencing data revealed ALDH+ cells demonstrated differential mean reads per kilobase million (RPKM) values in a subset of 13 genes from the ALDH family compared to ALDH- cells (Figure 2D) with the greatest RPKM increase over ALDH- observed in ALDH1B1. Not surprisingly, ALDH+ cells collectively demonstrated differential metabolic activity compared to ALDH- DIPG cells although individual gene changes were minor and not statistically significant (Supplemental Table 3). These changes include the putative metabolic oncogene PHGDH, a rate-limiting step in the conversion of 3-phosphoglycerate to serine [43] and glycolytic ENO1 and ENO1-ITI which are commonly overexpressed in tumors promoting the Warburg effect where the pathway is transcriptionally regulated by RAS and MYC [44–46]. RT-qPCR confirmation for ENO1, MAT2A and PSAT1 are depicted in Figure 2E.

Figure 2: Transcriptome analysis of ALDH+ cells reveals “stem-like” profile.

A. Diagram illustrating the main steps in Bru-seq for comprehensive transcriptome analysis performed in sorted SU-DIPG XIII cells. B. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) from the Hallmark database of induced pathways in ALDH+ cells compared to ALDH- cells. C. RT-qPCR analysis of canonical “stem-cell” reprogramming genes in sorted DIPG cells. Data were normalized to GAPDH and fold change was calculated compared to ALDH+ with values plus minus SEM. p-values calculated with an unpaired t-test. D. Sequencing reads from nascent RNA expressed as reads per thousand base pairs per 1 million reads (RPKM) of selected ALDH-family genes. E. RT-qPCR analysis of metabolism genes in sorted DIPG cells. Data normalized to GAPDH and fold change was calculated compared to ALDH+ with values plus minus SEM. P-values calculated with an unpaired t-test. F. and G. Data from single-cell RNA sequencing [47] presented as transcript per million (TPM) values from seven DIPG biopsies. F. ALDH gene-family expression in malignant, immune and oligodendrocyte cells. M=malignant cells; I=immune cells; O=oligodendrocytes. G. ALDH2 gene expression in immune cells from DIPG patient tissues.

The importance of ALDH gene expression in DIPG was further validated by analyses of publicly available single-cell RNA-sequencing (Sc-RNAseq) data performed of DIPG biopsy material obtained from seven DIPG patients harboring K27M mutations in histone H3.3 or H3.1 [47]. Our analysis indicated elevated expression across many genes in the ALDH gene family when malignant cells were compared to immune cells or oligodendrocytes isolated from these tumors (Figure 2F). Secondly, of the immune cells, ALDH2 expression was largely observed in dendritic and myeloid immune cells (Figure 2G). Although this patient cohort is too small to reach statistical significance, analyses of this Sc-RNA seq data provides validation of elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family expression in DIPG.

Patient-derived ALDH+ DIPG cells demonstrate stem-like properties.

To determine if ALDH+ SU-DIPG XIII cells exhibit stem-like characteristics including tumor initiating properties compared to ALDH- cells as described in other malignancies, we performed proliferation and neurosphere formation assays on ALDH sorted cells. ALDH+ cells demonstrated significantly greater proliferation than ALDH- cells following FACS sorting measured at various time points (Figure 3A). By 96 hours, the observed proliferation differences were no longer significant perhaps indicative of ALDH- cells regaining expression of ALDH (Supplemental Figure S6), retaining expression of other stem cell markers or ALDH+ cells losing their high ALDH+ expression. ALDH+ cells demonstrated significantly greater neurosphere size compared to ALDH- cells at day 3 through day 10 following FACs sorting (Figure 3B and C). By day 10, ALDH+ cells retained a significantly greater number of neurospheres further indicative of increased proliferation compared to ALDH- cells (Figure 3D).

Figure 3: ALDH+ DIPG cells demonstrate an aggressive stem-like phenotype in vitro.

A. Alamar Blue proliferation assays were performed in ALDH FACS sorted SU-DIPG XIII cells Data plotted as mean RFU values plus minus SEM from three independent experiments. P-values calculated with a one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-hoc test to correct for multiple comparisons. ***0.0005, ****<0.0001, **0.0052, NS=not significant. B. Representative phase contrast images of ALDH sorted SU-DIPG XIII cells at 10x with scale bar= 500 μm. C. Sphere size data (μm) quantified in ImageJ plotted as average of 4 experiments plus minus SEM. D. Sphere number was quantified on day 10. Plot represents the average of 4 experiments plus and minus SEM. P-values for C and D calculated with a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test to correct for multiple comparisons. E. Representative image of FACS sorted SF8628 cells on day 14. F. Percent change of crystal violate stained colonies ± SEM from three separate experiments. P-value was calculated from a paired 2-tail t-test.

Next, we evaluated SF8628 DIPG patient-derived cells which exhibit a smaller total population of ALDH+ cells compared to SU-DIPG XIII (Figure 1B and D) to see if this line harbored these stem-like features. ALDH+ SF8628 cells demonstrated significantly increased colony formation and colony size compared to ALDH- cells (Figure 3E and F). Together, these data demonstrate tumor heterogenous ALDH expression which when elevated (ALDH+ cells) result in a more proliferative subpopulation compared to ALDH- cells.

Tumor initiating capability of ALDH+ DIPG stem cells in vivo

To determine the tumor initiating capability of ALDH+ cells in vivo, luciferase labeled DIPG 007 cells (DIPG 007-luc) were FACS sorted into ALDH+, ALDH- populations or left unsorted and implanted into the pons of immunocompromised mice. In the unsorted population roughly 16% of DIPG cells were ALDH+ and 80% ALDH- (Supplemental Figure S1A). Bioluminescence imaging (BLI) confirmed tumor growth in the ALDH+ and unsorted groups with tumor initiation observed around sixty days post implantation as measured by an increase in bioluminescence over baseline. By week twelve, average total flux was significantly greater in ALDH+ mice compared to ALDH- mice (Figure 4A–B) with unsorted implanted mice having the greatest measure of total luminescence compared to both groups. Ex vivo BLI of resected brains confirmed presence of tumors in the pons where data corroborated in vivo findings of increased bioluminescence activity in ALDH+ and unsorted brain tumors compared to ALDH- (Figure 4C). Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated that ALDH+ and unsorted tumor bearing mice exhibited significantly decreased survival compared to ALDH- implanted mice. Median survival was 100, 137 and 86 days for ALDH+, ALDH- and unsorted mice, respectively. ALDH- mice with no signs of tumor burden, such as an increase in BLI signal or body weight loss, were typically sacrificed 160–220 days post implantation. (Figure 4D).

Figure 4: Aggressive tumor progression and shorter overall survival of ALDH+ tumor bearing mice.

Aldefluor stained and FACS sorted HJSD-DIPG 007 luciferase expressing cells (DIPG 007-luc) were intracranially implanted into NSG mice. A. Data represents average total flux per implant group ± SEM. P-values calculated with unpaired t-tests. B. Representative BLI images of each implant group at 3 months. C. Ex vivo BLI of extracted brains acquired at the time of sacrifice. D. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for ALDH+ (n=13), ALDH- (n=9) and unsorted (n=6) mice, respectively with p-values from log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests. E. Representative cryo-fluorescence tomography (CFT) of a brain extracted from a mCherry expressing and ALDH+ sorted DIPG 007 mouse at day 90 post-implantation. Image presented as maximum intensity projections (MIPs) at the 555excitation acquisition. F. Representative H&E and immunohistochemical staining of extracted brain sections. Images acquired at 40x, scale bar= 100 μm. G.-I. IHC quantification using ImageJ software. One-way ANOVA with p values for multiple comparisons from Tukey’s post-hoc test.

In a different cohort we orthotopically implanted mCherry labeled DIPG 007 cells FACS sorted for ALDH. Once significant weight loss had been observed between day 88–91 post-implantation, brains were removed, cryo-preserved, embedded in OCT prior to performing cryo-fluorescence tomography (CFT) imaging (Xerra, Emit Imaging, Boston, MA) using the 555-excitation laser to visualize distribution of cherry-positive DIPG cells in the murine brain (Figure 4E). 3D reconstructions of the CFT imaging demonstrated a diffuse tumor cell infiltration in the implanted brains with the most densely populated DIPGs located near the implantation site (pons) in the 555 nM excitation maximum intensity projection images (MIPs) and becoming more diffuse moving through the midline and frontal cortex of the brain with no clear tumor boarders.

We first immunostained resected brain tissue sections for H3K27M expression to confirm the presence of DIPG cells in the ALDH+, ALDH- and unsorted implanted mice. We observed that while all implanted mice had cells positive for H3K27M compared to normal brains (NSG), ALDH+ and unsorted implants had substantially more robust H3K27M staining compared to ALDH- implants indicative of DIPG tumor-initiating cells (Figure 4F). The presence of positive H3K27M cells were most dense near the implantation site in the pons becoming more diffuse moving towards the front of the brain. Next, we probed for Ki67 to determine the presence of proliferating cells in the brain tissue. A similar diffuse staining pattern was observed in ALDH+ and unsorted tumors demonstrating robust staining compared to ALDH- brain tissue which had fewer cells positive for Ki67 demonstrating a more aggressive nature of the ALDH+ subpopulation (Figure 4F). To determine whether tissue from mice implanted with ALDH+, ALDH- and unsorted cells exhibited varying stem cell-like characteristics, we evaluated the expression of Nestin, a neural stem cell lineage marker. Dense Nestin-positive cells were observed near the implantation site in the pons with the staining characteristic becoming more diffuse moving further from the implantation site. While ALDH+, ALDH- and unsorted brain tissue had cells positive for Nestin, tumors from ALDH+ and unsorted implantations demonstrated greater numbers of Nestin-positive cells compared to ALDH- implantations. Morphologically, tumor tissue from ALDH+ and unsorted mice appeared more disorganized indicative of high-grade tumors while tissue from ALDH- tumors appeared more organized and well-differentiated. Overall, ALDH+ tumor tissue demonstrated denser cell morphology compared to ALDH- and unsorted implanted mice which can be observed by the significantly increased number of H3K27M-positive cells (Figure 4G), Ki67-positive cells (Figure 4H) and Nestin-positive cells (Figure 4I) in ALDH+ implants compared to all other groups.

MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition in DIPG cells

To evaluate the efficacy of molecular targeted therapies, we tested the effects of MAPK and/or PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition in DIPGs with differences in ALDH and CD133 expression. SU-DIPG XIII, SU-DIPG IV, SF7761, SF8628 cells were treated with the MEK inhibitor PD0325901 (PD-901), the pan-PI3K/mTOR inhibitor GSK2126458 (GSK-458) or combination of both (901+GSK). Decreased phosphorylation of ERK and AKT, surrogate markers for MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition, respectively, were observed after treatment with each inhibitor individually or in combination in all four DIPG cell lines (Supplemental Figure S2 A–D).

To gain further insight into molecular and cellular consequences of pathway inhibition cell lysates from treated SU-DIPG XIII cells were analyzed by Reverse Phase Protein Array (RPPA). Selective inhibition of the MAPK and the PI3K/mTOR pathways was confirmed as depicted in heat maps (Supplemental Figure S2 E and F). Changes in phosphorylation or protein expression downstream of PI3K/mTOR or MAPK pathways were apparent for a number of selected proteins, confirming pathway inhibition in DIPG cell lines. Together these results demonstrate selectivity of MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition by single agent therapies and in combination therapy in patient-derived DIPG cell lines.

Transcriptome analysis identifies gene sets regulated by MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition.

To verify targeted MAPK/PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway inhibition in both subtypes identified in SU-DIPG XIII, cells were treated with PD-901, GSK-458 or in combination (901+GSK) prior to sorting into ALDH+ and ALDH-. ALDH positivity in SU-DIPG XIII cells ranged from 25–45 percent in the DMSO or treated cell population with GSK-458 having the greatest effect, whereas 50–75 percent cells were negative for ALDH expression by Aldefluor assay (Supplemental Figure S1B). Following sorting, nascent transcriptome analysis was performed as described in methods. Gene expression profiles of combination treated (901+GSK) confirmed downregulation of MAPK and PI3K/mTOR signaling pathway targets (CCND1, DUSP6, MYC) and (4EBP1, VEGFA, GSK3A), respectively as a result of dual MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition (Figure 5A and B). For single agent treatment, gene expression profiles confirmed downregulation of transcriptional targets associated with MEK inhibition by PD-901 treatment and those associated with PI3K/mTOR inhibition with GSK-458 in both ALDH+ and – cells (Supplemental Figure S3 A–D). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) derived from the KEGG pathway database identified similar gene sets repressed by combination therapy in particular expected downregulation of mTOR, VEGF, phosphatidylinositol and apoptosis (Figure 5C and D). Bru-seq results were confirmed by RT-qPCR in GSK-458, PD-901, combination (901+GSK) or control treated ALDH+ and ALDH– SU-DIPG XIII cells (Figure 5E and F). In summary, our transcriptome analysis indicates that single agent therapy with PD-901 downregulated targets of the MAPK pathway, GSK-458 downregulated targets of the PI3K/mTOR pathway and combination inhibits known downstream targets of each pathway in both ALDH+ and ALDH- DIPG cell subgroups.

Figure 5. Gene sets regulated by MAPK and PI3K/mTOR inhibition.

A and B. Sequencing reads from nascent RNA expressed as reads per thousand base pairs per 1 million reads (RPKM) and mapped to target genes in combination (901+GSK) treated (yellow) and DMSO (blue) treated SU-DIPG XIII ALDH +/− cells, respectively. C and D. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in combination treated ALDH + and ALDH- cells, respectively. E and F. RT-qPCR analysis of MAPK and PI3K responsive genes in PD-901, GSK-458 and combination (901+GSK) treated ALDH+/ALDH- SU-DIPG XIII cells. Data were normalized to GAPDH and fold change was calculated, compared to DMSO with ± SEM from at least three independent experiments with p-values from unpaired t-test.

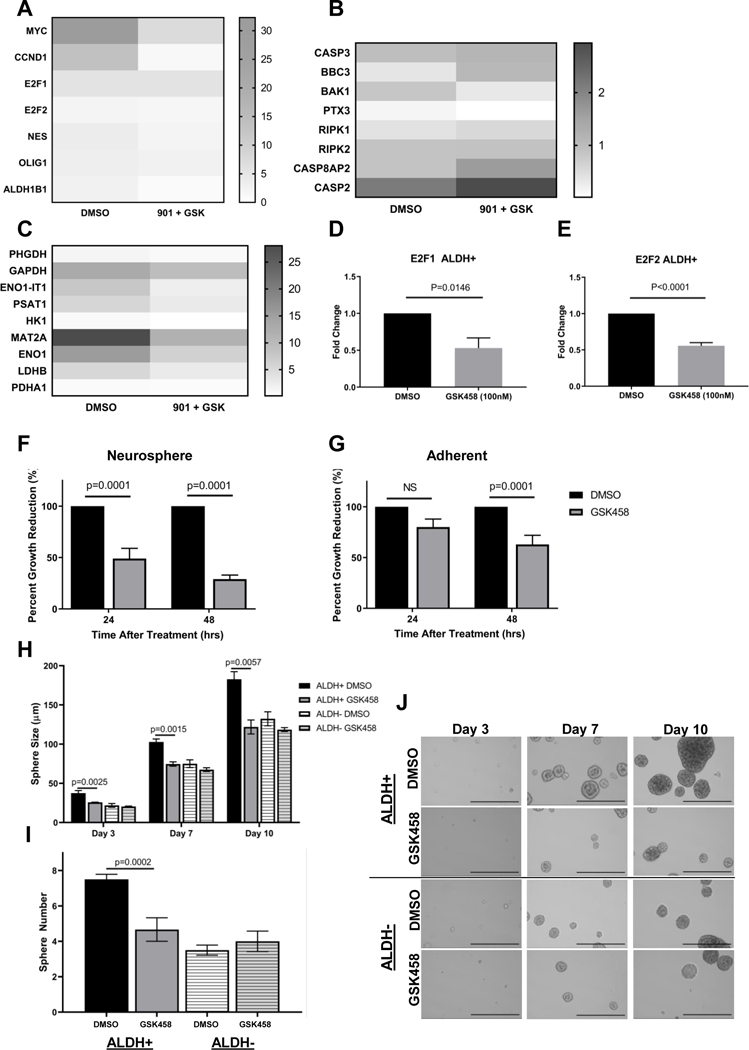

MAPK/PI3K/mTOR inhibition reduces the stem-like phenotype of the ALDH+ cells.

Here we posed the question whether MAPK, PI3K/mTOR, or MAPK/PI3K/mTOR inhibition prevents stem-like reprogramming in ALDH+ cells. To address this, we compared ALDH+ cells treated with PD-901, GSK-458 or combination (901+GSK) thereof to DMSO treated cells. Bru-Seq results demonstrated that genes such as MYC, E2F1, CCND1, ALDH1B1 and NES were significantly downregulated when MAPK/PI3K/mTOR pathway was inhibited by combination (901+GSK) compared to DMSO treated samples (Figure 6A) indicative of decreased cellular proliferation capacity as a result of treatment targeting stemness potentially addressing resistance. Interestingly, the expression of other ALDH family genes was found to be rather unchanged (Supplemental Figure 4D), yet expression of differentiation marker genes like CSPG4, PDGFRA, SOX10, Oligo2, NKX2.2 and Notch1 were found to be decreased in DIPGs treated with combination of 901 and GSK (Supplemental Figure 4E). Genes upregulated by combination therapy in ALDH+ cells included pro-apoptotic genes Caspase 3, BBC3 and BAK1 indicating efficacy of molecularly targeted kinase therapy in killing ALDH+ DIPG stem cells specifically (Figure 6B). Metabolome genes which were previously found to be upregulated in ALDH+ vs ALDH- cells (Figure 2E) became downregulated during either PI3K/mTOR, MAPK or combination inhibition in ALDH+ cells (Figure 6C). Specifically, genes associated with glycolysis and glycolytic signaling ENO1, HK1, LDHB and ENO1-IT1 were downregulated with single or dual agent therapy. Results suggest that decrease observed in tumorigenesis/proliferation by inhibition of the MAPK/PI3K/mTOR pathways may be mediated through metabolic signaling changes in ALDH+ cell population.

Figure 6: PI3K/mTOR inhibition decreases transcription of DNA-damage repair (DDR), “stem-like” and metabolic genes in ALDH+ cells and inhibits “stem phenotype”.

A-C. Heatmap of Bru-seq data from GSK-458, PD-901 and combination treated (901+GSK) ALDH+ SU-DIPG XIII cells of selected stemness (A) apoptotic (B) and metabolomic (C) genes. D-E. RT-qPCR analysis of E2F1 and E2F2 in GSK-458 treated ALDH+ SU-DIPG XIII cells. Fold change calculated by comparing to DMSO treated cell and normalized to GAPDH with values ± SEM from at least three independent experiments. p-values calculated with an unpaired t-test. F-G. Viability assay in HSJD-DIPG 007 neurospheres and adherent cells, respectively, treated with 10nM GSK-458 or equimolar DMSO from at least three independent experiments ± SEM with p-values of unpaired t-test. H.–I. SU-DIPG XIII cells were treated with 100nM GSK-458 or DMSO for 2 hours followed by FACS sorting for Aldefluor activity. Sphere size and number quantified in ImageJ and plotted of 4 independent experiments ± SEM, respectively, with p-values calculated with a one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post-hoc test to correct for multiple comparisons. J. 10x representative images (scalebar = 500 μm) of sorted and treated SU-DIPG XIII.

We observed that PI3K/mTOR inhibition alone using GSK-458 or MAPK inhibition alone using PD-901 reduced stemness but with different genes being downregulated (Supplemental Figure S4A). PD-901 had a stronger effect downregulating MYC while GSK-458 preferentially downregulated E2F1 and E2F2 where this observation was validated further by RT-qPCR of E2F1 and E2F2 depicted in Figure 6D and E. Single agent therapy also differentially targeted pro-apoptotic genes and metabolism when compared to combination therapy (Supplemental Figure S4 B and C).

Next, we determined if sensitivity to PI3K/mTOR inhibition by GSK-458 was dependent on the cells’ state of differentiation by evaluating drug efficacy in 2D cultures containing 10% FBS vs 3D neurosphere cultures in stem cell media. We observed that PI3K/mTOR inhibition by GSK-458 was more effective in 3D neurospheres (Figure 6F) compared to 2D adherent cells (Figure 6G) pointing towards its efficacy in targeting undifferentiated, high grade tumors with stem-like characteristics. Cell proliferation and neurosphere size and formation assays demonstrated PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition resulted in decreased cell growth in the ALDH+ population (Figure 6H–J). GSK-458 treated ALDH+ cells demonstrated a significant reduction in size compared to ALDH+ DMSO cells at day 3 and continuing through day 10 post treatment (Figure 6H) where a significant reduction in neurosphere number compared to ALDH+ DMSO cells was observed (Figure 6I and J). Not surprisingly, ALDH- cells treated with GSK-458 did not demonstrate a significant decrease in neurosphere size or number compared to ALDH- DMSO controls (Figure 6H–J). Taken together, these findings indicate efficacy of PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition in specifically targeting ALDH + DIPGs with stem-like characteristics and high cellular plasticity.

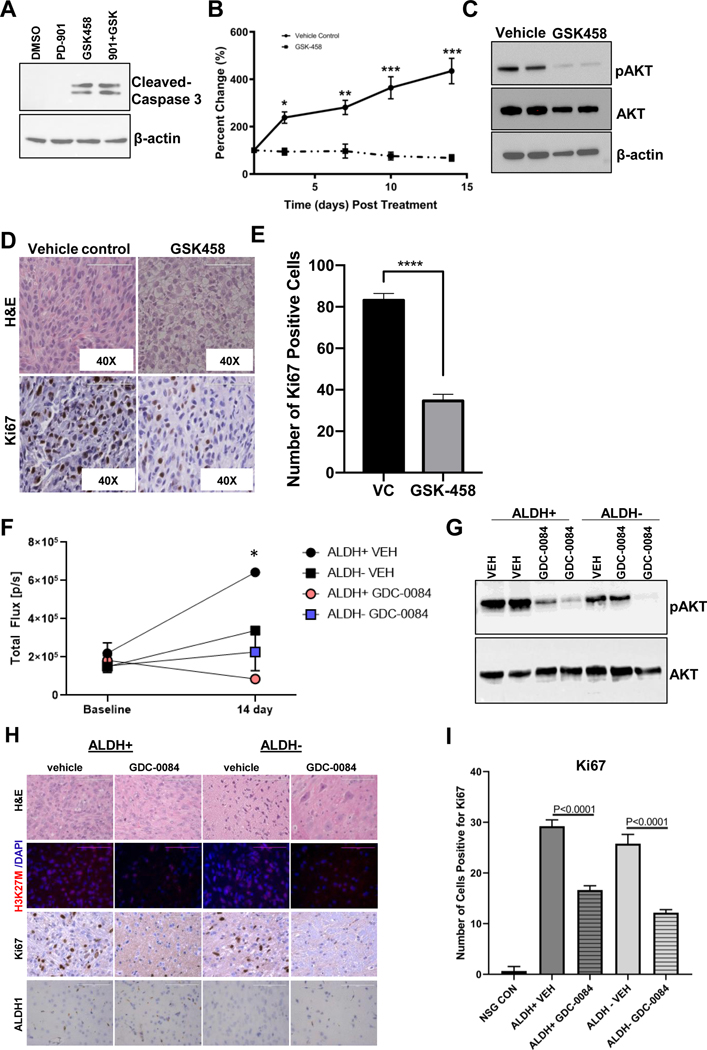

PI3K/mTOR inhibition induces Caspase-3 mediated cell death and tumor growth arrest in vivo

Using single agent GSK-458, PD-901 or combination thereof, we observed that Caspase 3 mediated cell death was driven by PI3K/mTOR inhibition indicating DIPGs dependency on PI3K/mTOR signaling (Figure 7A). Interestingly, Caspase 3 mediated cell death was only observed in cells treated with GSK-458 or combination but not in PD-901 treated cells alone. Thus, we sought to evaluate efficacy of GSK-548 PI3K/mTOR inhibition alone in vivo using a flank xenograft DIPG model. Immunocompromised mice bi-laterally implanted with SF8628 DIPG cells were treated daily for 14 consecutive days with a dose of 3 mg/kg of GSK-458 by oral gavage (p.o.) or vehicle control (VEH) when tumors reached an average size of ~100 mm3. At the end of the treatment, animal weight loss did not exceed −10% of initial starting weight indicating no adverse toxicity due to treatment. Tumor growth was significantly reduced with GSK-458 treatment compared to vehicle control treated mice (Figure 7B). Western blot analysis of resected tumor tissue revealed a near total reduction in pAKT levels (Ser473) in GSK-458 treated tumors indicative of sufficient target inhibition and delivery of GSK-458 to the tumor (Figure 7C). Histological assessment of treated vs. vehicle control tumor tissue demonstrated distinct tumor morphology of vehicle treated mice, which contained condensed cohesively growing cells with a high nuclear-cytoplasm ratio while tumors from GSK-458 treated mice exhibited areas of larger cytoplasmic volume indicative of apoptosis (Figure 7D). Furthermore, diminished proliferation marker expression of Ki67 indicative of tumor growth inhibition was observed in histological tumor sections of treated mice (Figure 7D). Quantification of Ki67 positive cells confirmed that treatment with GSK-458 significantly reduced proliferation (Figure 7E).

Figure 7: Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR signaling induces Caspase-3 mediated cell death and arrests tumor growth.

A. Representative western blot of cleaved Caspase-3 from unsorted SU-DIPG XIII cells treated for 2 hours with 10uM of PD-901, GSK-458 or combination thereof. B. NSG mice inoculated with 2×106 SF8628 cells into the flank were treated with GSK-458 (3 mg/kg/day, oral gavage) or vehicle control for 14 consecutive days. Tumor volume was measured by caliper, normalized to the volume on the first day of treatment and presented as the average percent change in volume by condition (GSK-458 N=8 tumors, VEH control N=6 tumors) ± SEM with p-values of t-tests with Holm-Sidak multiple correction. *p=0.0005; **p=0.00002; ***p<0.000001. C. Representative western blotting of tumor tissue. D. H&E and Ki67 staining of tumor tissue sections with images acquired at 40X (scale bar= 100 μm). E. IHC quantification of Ki67 using ImageJ software. *** Unpaired t-test with p < 0.0001. F. In vivo BLI of orthotopically implanted mice with ALDH+ or ALDH- DIPG 007-Luc cells prior to initiation of treatment (baseline) and day 14 of treatment with unpaired t-tests corrected for multiple comparisons using a Holm Sidak post-hoc test. Mice were treated via p.o. with GDC-0084 (10 mg/kg for 14 days) or vehicle control (VEH). * ALDH+ VEH vs. ALDH+ GDC-0084 p=0.015. G. Representative western blot of brain tissue from mice implanted with ALDH+ or ALDH- DIPG 007-Luc cells. H. Representative H&E and immunohistochemical staining of extracted brain tissue sections following 14 days of treatment with images acquired at 40x with 100 μm scale bar. I. IHC quantification of Ki67 using ImageJ software. One-way ANOVA with p values for multiple comparisons from Tukey’s spost-hoc test.

Finally, we sought to evaluate the efficacy of PI3K/mTOR inhibition using GDC-0084 in the orthotopic xenograft model established by implanting DIPG 007-luc ALDH+ or ALDH- cells. GDC-0084 was chosen as the PI3K/mTOR inhibitor since it showed superior GI absorption and BBB penetrance in a predictive drug delivery model using BOILED EGG (Supplemental Figure S5) when compared to GSK-458. DIPG 007-luc cells were Aldeflour stained, FACS sorted into ALDH+ and – cell populations and intracranially implanted into immunocompromised mice. Roughly 20 percent DIPG 007 cells were found to be ALDH+ and 80 percent to be ALDH- (Supplemental Figure S1C). After implantation of the two DIPG cell population, tumor growth was monitored by bioluminescence imaging until ~ day 80 when BLI activity increased significantly over baseline indicative of tumor growth at which point treatment with GDC-0084 was initiated and continued for 14 consecutive days with a dose of 10 mg/kg per day administered by oral gavage (p.o.). By day 14 BLI showed significant signal decrease in ALDH+ mice treated with GDC-0084 compared to ALDH+ vehicle control treated (Figure 7F). Western blot analysis of resected brain tissue revealed a reduction in pAKT levels (Ser473) in GDC-0084 treated mice indicative of target inhibition and importantly delivery of GDC-0084 to the brain (Figure 7G). Immunohistochemical assessment of treated ALDH+ and ALDH- vs. vehicle control brain tissue demonstrated reduced H3K27M expression and a dramatic reduction of Ki67 positive cells with PI3K/mTOR inhibition (Figure 7H). Quantification of Ki67 positive cells confirmed this observation where GDC-0084 treatment significantly reduced Ki67 in both ALDH+ and ALDH- brain tissue (Figure 7I). ALDH1 staining was observed in ALDH+ brain section and to a much lesser extend in ALDH- brain section, but appeared unaffected by the treatment (Figure 7H).

Taken together, these results show that PI3K/mTOR inhibition results in Caspase 3 mediated cell death and tumor regression in vivo.

Discussion

A better understanding of the pathophysiology of DIPG is critical to developing novel therapeutics desperately needed for the treatment of DIPG. To this end, we demonstrate that expression of ALDH and CD133 is heterogeneous across patient tumor material and that their expression is not mutually exclusive. Through transcriptomics, in vitro proliferation, neurosphere-based assays and in in vivo tumor models, we describe an aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH+) expressing DIPG cell population which exhibits stem-like characteristics that are reversed by MAPK/PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition. Our findings demonstrate tumor heterogeneity in DIPG with cells expressing high levels of ALDH, which in other malignancies have been linked to therapeutic resistance and described as a marker of cancer stem cells as well as a predictor of poor clinical outcome [8, 48–51]. The ALDH+ subpopulation may likely contribute to tumor resistance in DIPG and findings from our present work may have implications for the development of future therapies targeting treatment resistance and ALDH+ CSCs specifically.

The observed heterogeneity in ALDH and CD133 stem cell marker expression in DIPG may likely be a result of differences in tissue origin and prior treatment such as radiotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy. We observed, that SU-DIPG XIII, IV, 29 and DIPG 007 cells, obtained from early postmortem autopsies and from patients treated with radiotherapy alone or in combination with chemotherapy demonstrated high ALDH+ and/or CD133+ expression. In contrast, SF7761 and SF8628 cell lines were generated from biopsy material of DIPG patients not previously treated and demonstrated little-to-no ALDH+ or CD133+ expression suggesting a role for these stem cell markers in resistance mechanisms. It remains to be investigated whether previous standard of care therapies increase the emergence of a more aggressive ALDH expressing stem-like cell population observed in SU-DIPG XIII, IV, 29 and DIPG 007 and the focus of ongoing studies.

The potential relevance of an ALDH+ cancer stem cell population in DIPG with a stem-like expression profile often observed in treatment resistant CSCs in other malignancies [52, 53] was validated by our analysis of publicly available single-cell RNA sequencing data from DIPG biopsies [47]. High expression of ALDH genes in malignant DIPG cells when compared to oligodendrocytes or immune cells was found in these DIPG biopsies indicative of existence of a CSC population and a need for consideration in future therapies. It remains to be investigated why we observed upregulation predominantly of ALDH1B1 in SU-DIPG XIII cells, yet observed moderate expression of ALDH1B1 and high expression of ALDH2 in sc-RNA seq data from DIPG biopsies.

This stem-like expression profile of ALHD+ cells was further found to translate into a more proliferative behavior in cell culture as well as in in vivo studies. It should be noted that some but not all mice implanted with ALDH- cells did develop tumors or exhibited increased proliferation in vitro by 96 hrs, which may be the result of other stem cell and CSC markers present such as CD133, or activation of ALDH expression in ALDH- cells. In fact, sorted ALDH- SU-DIPG XIII cells were found to regain expression of ALDH albeit to a lesser extent than ALDH+ cells, as assessed by Aldefluor assay and flow cytometry as early as 24 hrs post initial sorting (Supplemental Figure S6). This may indicate that regulation of ALDH expression not only adds to tumor heterogeneity of the DIPG tumors, but that its expression maybe regulated by undetermined extrinsic factors contributing to cell plasticity of DIPGs. Future studies will also focus on tumor initiating capability of ALDH+ cells by utilizing limiting dilution assays in vivo.

Transcriptomic analyses of ALDH+ and – cells after MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathway inhibition indicated that both ALDH+ and ALDH- cell population responded to single agent PI3K/mTOR inhibition with an upregulation of the MAPK pathway. This is not surprising since PI3K addicted cancer cells have been shown to attempt evasion of cell death by upregulation of MAPK signaling [2, 54] and the rationale for the co-targeted approach taken here with a MEK inhibitor to simultaneously suppress the MAPK pathway. Interestingly, the observed upregulation of the MAPK pathway at the transcriptional level, was not observed at the posttranslational level in our proteomic studies, likely indicative of a delayed effect from transcription to protein translation.

As described, glyctolytic signaling was found to be upregulated in ALDH+ DIPGs likely contributing to increased proliferation observed in ALDH+ cells. Combination therapy, decreased glycolytic signaling, cell proliferation and increased cell death. This was not surprising, since PI3K/mTOR are known regulators of glucose and lipid metabolism [55, 56] supporting use and efficacy of these targeted therapies in DIPG.

Upregulation of stem cell marker expression like ALDH is often observed with radio- and chemotherapy in various malignancy and likely contributing to drug resistance and tumor recurrence [57]. Interestingly, our studies demonstrated that molecularly targeted therapy (PI3K/mTOR/MAPK) did not increase expression of ALDH or other stem markers indicating that this therapy, targeted towards CSC, may be superior over existing standard of care treatments by circumventing tumor resistance and recurrence. In fact, our transcriptomic data indicated a reversal of the stem-like gene expression profile, downregulation of DDR gene and induction of pro-apoptotic gene signatures in the ALDH+ cells supporting rationale for targeted PI3K inhibition and eradication of CSC to prevent drug resistance and tumor recurrence in DIPG. Not surprisingly, ALDH1B1 gene, which was found to be upregulated in ALDH+ cells, was modulated upon combination treatment while other ALDH family genes appeared to be rather unchanged. Histological assessment of ALDH expression after treatment indicated no effect on ALDH1 expression in tumor section, however flow cytometric analysis of ALDH+ SU-DIPG XIII cells showed an effect of combination treatment by Aldefluor staining (Supplemental Figure S7). It remains to be investigated what role ALDH1B1 or other ALDH family gene specifically play in regulating stemness in DIPG.

Interestingly, we found that PI3K/mTOR inhibition with GSK-458 demonstrated higher efficacy in inhibiting cell proliferation in less-differentiated, stem-like 3D neutrosphere cultures compared to 2D. Although we have yet determined whether ALDH+ cells differentiate into drug insensitive ALDH- cells upon treatment with PI3K/mTOR and MAPK inhibitors, we found that differentiation marker expression was decreased in ALDH+ cells upon combination treatment as similarly observed during OPC differentiation to oligodendrocytes [58]. However as described by Filbin et al [47], DIPGs appear to be most similar to OPC cells but likely lost their ability to terminally differentiate due to the H3K27M mutation.

Taken together, these findings are supported by studies in other malignancies demonstrating a key role for both, the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and MAPK signaling pathways, in activating stemness and chemo resistance of cancer cells [59–63]. Thus, inhibition of these pathways in DIPG may similarly regulate stemness and differentiation thereby overcoming therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence, providing interesting targets for the treatment of pediatric brain tumors. As radiotherapy remains the standard of care for DIPG, future work will include assessment of stem cell marker expression in response to treatment, particularly ALDH expression, and evaluate whether targeted CSC therapy, either through PI3K/mTOR inhibition or ALDH inhibition, can prevent tumor recurrence.

Efficacy of using PI3K inhibitors or a combination with MAPK inhibitors has previously been explored for DIPG [2, 35] and blood-brain barrier penetrance has been shown to be circumvented by CED delivery, however, the effect on ALDH+ CSC has yet been explored. Using a predictive drug delivery model, we determined that GDC-0084 may be superior over GSK-458. GDC-0084 has been shown to penetrate the BBB with minimal efflux [64] [65] and is currently being tested in Phase I clinical trial in combination with radiotherapy for treatment of DIPG (NCT03696355). The use of GDC-0084 in our orthotopically implanted ALDH+ and ALDH- mice resulted in a significant reduction of in vivo BLI signal indicative of tumor growth reduction in treated ALDH+ mice, but not in ALDH- mice further supporting our previous findings in cell culture. Furthermore, our data is supported by findings from Duchatel et al. where DIPGs with an H3K27M mutation were significantly more sensitive to the PI3K inhibition when compared to GBM cells, an effect which appeared independent of the PI3K mutational status in DIPGs [25]. Taken together, targeted inhibition of the PI3K/mTOR pathway may thus preferentially kill ALDH+ CSC thereby lending itself as an attractive clinical target used in combination with conventional therapies or other molecular therapeutics to particularly reduce treatment resistance and tumor recurrence.

In summary, our work identifies heterogeneity in expression of CSC markers ALDH and CD133 uncovering existence of cancer stem cells in DIPG that likely contribute to drug resistance and tumor recurrence. However, we did not find the ALDH+ cell population to be a slow-cycling, quiescent cell population as often described for cancer stem cells of relapsed patients, a conundrum to be resolved in future studies. ALDH+ DIPGs detected here, appeared to have regained their proliferative potential and tumorgenicity, maybe reflective of the fast tumor relapse rate observed in DIPG patients. ALDH expression may be fluid and controlled by yet determined factors contributing to cell plasticity in DIPG and likely their inability to terminally differentiate. Rather than determined by a fixed intrinsic state, the existence of ALDH+ DIPG cells, with a higher proliferative capacity due to metabolic rate changes may provide insight into these cancers and indicate that the microenvironment may play a significant role in regulating these cells. Future studies will focus on regulation of ALDH in DIPG as well as distinct function of specific ALDH isoforms in tumorigenesis. Our findings support the development of new therapeutic opportunities targeting the stem population in DIPG to prevent drug resistance, tumor recurrence and improve overall treatment outcomes for DIPG patients.

Limitations of the Study

Due to possible variations of staining and inhibitor efficiency in the Aldefluor assay as well as gate cut-off differences during FACS sorting, variations in ALDH+ an – cell separation are to be expected and may have contributed to the observation of tumors in ALDH- cell implants.

Supplementary Material

Implications Statement.

Characterization of ALDH+ DIPGs coupled with targeting MAPK/PI3K/mTOR signaling provides an impetus for molecularly targeted therapy aimed at addressing the CSC phenotype in DIPG.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by ChadTough/Michael Mosier Defeat DIPG foundation research grant funding (R. Surowiec, S. Ferris, S. Galban). The authors wish to thank the functional proteomics RPPA core facility supported by MD Anderson Cancer Center support Grant # 5 P30 CA016672–40 and Michelle Paulsen in assisting with Bru-Sequencing under grant support from 1 R01 CA213214 and UM1 HG009382 (K. Bedi, M. Ljungman). Flow cytometry work was performed at the University of Michigan Flow cytometry Core, which is supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers P30CA046592 and P30 CA04659229. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Mohammed Farhoud from Emit Imaging for performing the cryo-computed tomography. The authors wish to thank Drs. Uday B. Maachani, Mark M. Souweidane, Sriram Venneti as well as Michelle Monje- Deisseroth for providing us with the DIPG cell lines SU-DIPG IV, SU-DIPG XIII, HSJD-DIPG 007 and SU-DIPG 29, respectively. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Filbin’s group who has made the Sc-RNA sequencing data publicly available (https://singlecell.broadinstitute.org/single_cell/study/SCP147/single-cell-analysis-in-pediatric-midline-gliomas-with-histone-h3k27m-mutation; [47]) and Cara Spencer from the Galban lab for aiding in analyzing the scRNA seq data.

Footnotes

Resource Availability

The datasets supporting the current study are available in the ‘supplemental excel file’ as well as from the corresponding author upon request and available on GEO (accession number GSE149682).

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Misuraca KL, Cordero FJ, and Becher OJ, Pre-Clinical Models of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Front Oncol, 2015. 5: p. 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu YL, et al. , Dual Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MEK/ERK Pathways Induces Synergistic Antitumor Effects in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Cells. Transl Oncol, 2017. 10(2): p. 221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lapin DH, Tsoli M, and Ziegler DS, Genomic Insights into Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Front Oncol, 2017. 7: p. 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh SK, et al. , Identification of human brain tumour initiating cells. Nature, 2004. 432(7015): p. 396–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez-Diaz PC, et al. , Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal esterase L1 (UCHL1) is associated with stem-like cancer cell functions in pediatric high-grade glioma. PLoS One, 2017. 12(5): p. e0176879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du FY, et al. , Targeting cancer stem cells in drug discovery: Current state and future perspectives. World J Stem Cells, 2019. 11(7): p. 398–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusoglu A. and Biray Avci C, Cancer stem cells: A brief review of the current status. Gene, 2019. 681: p. 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Najafi M, Mortezaee K, and Majidpoor J, Cancer stem cell (CSC) resistance drivers. Life Sci, 2019. 234: p. 116781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chae YC and Kim JH, Cancer stem cell metabolism: target for cancer therapy. BMB Rep, 2018. 51(7): p. 319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh SK, et al. , Identification of a cancer stem cell in human brain tumors. Cancer Res, 2003. 63(18): p. 5821–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monje M, et al. , Hedgehog-responsive candidate cell of origin for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2011. 108(11): p. 4453–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clement V, et al. , Limits of CD133 as a marker of glioma self-renewing cells. Int J Cancer, 2009. 125(1): p. 244–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glumac PM and LeBeau AM, The role of CD133 in cancer: a concise review. Clin Transl Med, 2018. 7(1): p. 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vasilogiannakopoulou T, Piperi C, and Papavassiliou AG, Impact of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Activity on Gliomas. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2018. 39(7): p. 605–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu SL, et al. , Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 circumscribes high invasive glioma cells and predicts poor prognosis. Am J Cancer Res, 2015. 5(4): p. 1471–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomita H, et al. , Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in stem cells and cancer. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(10): p. 11018–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi SA, et al. , Identification of brain tumour initiating cells using the stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase. Eur J Cancer, 2014. 50(1): p. 137–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harutyunyan AS, et al. , H3K27M induces defective chromatin spread of PRC2-mediated repressive H3K27me2/me3 and is essential for glioma tumorigenesis. Nat Commun, 2019. 10(1): p. 1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe BR, et al. , Histone H3 Mutations: An Updated View of Their Role in Chromatin Deregulation and Cancer. Cancers (Basel), 2019. 11(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagaraja S, et al. , Histone Variant and Cell Context Determine H3K27M Reprogramming of the Enhancer Landscape and Oncogenic State. Mol Cell, 2019. 76(6): p. 965–980 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma I. and Allan AL, The role of human aldehyde dehydrogenase in normal and cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Rep, 2011. 7(2): p. 292–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modarai SR, et al. , The anti-cancer effect of retinoic acid signaling in CRC occurs via decreased growth of ALDH+ colon cancer stem cells and increased differentiation of stem cells. Oncotarget, 2018. 9(78): p. 34658–34669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Castel D, et al. , Histone H3F3A and HIST1H3B K27M mutations define two subgroups of diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas with different prognosis and phenotypes. Acta Neuropathol, 2015. 130(6): p. 815–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackay A, et al. , Integrated Molecular Meta-Analysis of 1,000 Pediatric High-Grade and Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Cell, 2017. 32(4): p. 520–537 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duchatel R, Jackson E, Patabendige A, Cain J, Tsoli M, Monje M, Alvaro F, Ziegler D, Dun M, Targeting PI3K using the Blood Brain Barrier penetrable inhibitor GDC-0084 for the treatment of Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG). Neuro-Oncology, 2019: p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vansteenkiste JF, et al. , Safety and Efficacy of Buparlisib (BKM120) in Patients with PI3K Pathway-Activated Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Results from the Phase II BASALT-1 Study. J Thorac Oncol, 2015. 10(9): p. 1319–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopetz S, et al. , Phase II Pilot Study of Vemurafenib in Patients With Metastatic BRAF-Mutated Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33(34): p. 4032–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munster P, et al. , First-in-Human Phase I Study of GSK2126458, an Oral Pan-Class I Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies. Clin Cancer Res, 2016. 22(8): p. 1932–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matulonis U, et al. , Phase II study of the PI3K inhibitor pilaralisib (SAR245408; XL147) in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol, 2015. 136(2): p. 246–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yuen HF, et al. , Impact of oncogenic driver mutations on feedback between the PI3K and MEK pathways in cancer cells. Biosci Rep, 2012. 32(4): p. 413–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butler DE, et al. , Inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway activates autophagy and compensatory Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK signalling in prostate cancer. Oncotarget, 2017. 8(34): p. 56698–56713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galban S, et al. , A Bifunctional MAPK/PI3K Antagonist for Inhibition of Tumor Growth and Metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther, 2017. 16(11): p. 2340–2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chappell WH, et al. , Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget, 2011. 2(3): p. 135–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gopal YN, et al. , Basal and treatment-induced activation of AKT mediates resistance to cell death by AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in Braf-mutant human cutaneous melanoma cells. Cancer Res, 2010. 70(21): p. 8736–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang RT, Voronina U, Adeuyan J, Wu O, Shweitzer LY, Pisapia ME, Becher DJ, Souweidane OJ Maachani UBMM, Combined Targeting of PI3K and MEK Effector Pathways via CED for DIPG Therapy. Neuro-Oncology Advances, 2019. 1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grasso CS, et al. , Functionally defined therapeutic targets in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Nat Med, 2015. 21(6): p. 555–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vinci M, et al. , Functional diversity and cooperativity between subclonal populations of pediatric glioblastoma and diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma cells. Nat Med, 2018. 24(8): p. 1204–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith MC, et al. , CXCR4 regulates growth of both primary and metastatic breast cancer. Cancer Res, 2004. 64(23): p. 8604–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stacer AC, et al. , Imaging Reporters for Proteasome Activity Identify Tumor- and Metastasis-Initiating Cells. Mol Imaging, 2015. 14: p. 414–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paulsen MT, et al. , Use of Bru-Seq and BruChase-Seq for genome-wide assessment of the synthesis and stability of RNA. Methods, 2014. 67(1): p. 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paulsen MT, et al. , Coordinated regulation of synthesis and stability of RNA during the acute TNF-induced proinflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2013. 110(6): p. 2240–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daina A, Michielin O, and Zoete V, SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep, 2017. 7: p. 42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zogg CK, Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase: potential therapeutic target and putative metabolic oncogene. J Oncol, 2014. 2014: p. 524101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feo S, et al. , ENO1 gene product binds to the c-myc promoter and acts as a transcriptional repressor: relationship with Myc promoter-binding protein 1 (MBP-1). FEBS Lett, 2000. 473(1): p. 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ying H, et al. , Oncogenic Kras maintains pancreatic tumors through regulation of anabolic glucose metabolism. Cell, 2012. 149(3): p. 656–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Capello M, et al. , Targeting the Warburg effect in cancer cells through ENO1 knockdown rescues oxidative phosphorylation and induces growth arrest. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(5): p. 5598–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Filbin MG, et al. , Developmental and oncogenic programs in H3K27M gliomas dissected by single-cell RNA-seq. Science, 2018. 360(6386): p. 331–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ajani JA, et al. , ALDH-1 expression levels predict response or resistance to preoperative chemoradiation in resectable esophageal cancer patients. Mol Oncol, 2014. 8(1): p. 142–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Croker AK and Allan AL, Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44(+) human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2012. 133(1): p. 75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ginestier C, et al. , ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell, 2007. 1(5): p. 555–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, et al. , Epigenetic targeting of ovarian cancer stem cells. Cancer Res, 2014. 74(17): p. 4922–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang QE, DNA damage responses in cancer stem cells: Implications for cancer therapeutic strategies. World J Biol Chem, 2015. 6(3): p. 57–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mandal PK, Blanpain C, and Rossi DJ, DNA damage response in adult stem cells: pathways and consequences. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2011. 12(3): p. 198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engelman JA, et al. , Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant Kras G12D and PIK3CA H1047R murine lung cancers. Nat Med, 2008. 14(12): p. 1351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mao Z. and Zhang W, Role of mTOR in Glucose and Lipid Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yu JS and Cui W, Proliferation, survival and metabolism: the role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling in pluripotency and cell fate determination. Development, 2016. 143(17): p. 3050–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clark DW and Palle K, Aldehyde dehydrogenases in cancer stem cells: potential as therapeutic targets. Ann Transl Med, 2016. 4(24): p. 518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emery B. and Lu QR, Transcriptional and Epigenetic Regulation of Oligodendrocyte Development and Myelination in the Central Nervous System. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 2015. 7(9): p. a020461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gao XF, et al. , LncRNA SNHG20 promotes tumorigenesis and cancer stemness in glioblastoma via activating PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Neoplasma, 2019. 66(4): p. 532–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Deng J, et al. , Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway alleviates ovarian cancer chemoresistance through reversing epithelial-mesenchymal transition and decreasing cancer stem cell marker expression. BMC Cancer, 2019. 19(1): p. 618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murat A, et al. , Stem cell-related “self-renewal” signature and high epidermal growth factor receptor expression associated with resistance to concomitant chemoradiotherapy in glioblastoma. J Clin Oncol, 2008. 26(18): p. 3015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chiou SH, et al. , Coexpression of Oct4 and Nanog enhances malignancy in lung adenocarcinoma by inducing cancer stem cell-like properties and epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation. Cancer Res, 2010. 70(24): p. 10433–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blaj C, et al. , Oncogenic Effects of High MAPK Activity in Colorectal Cancer Mark Progenitor Cells and Persist Irrespective of RAS Mutations. Cancer Res, 2017. 77(7): p. 1763–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heffron TP, et al. , Discovery of Clinical Development Candidate GDC-0084, a Brain Penetrant Inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2016. 7(4): p. 351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wen PY, et al. , A first-in-human phase 1 study to evaluate the brain-penetrant PI3K/mTOR inhibitor GDC-0084 in patients with progressive or recurrent high-grade glioma. 2016. 34(15_suppl): p. 2012–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.