Abstract

In the United States, family formation decision-making is more complex than the predominant models that have been used to capture this phenomenon. Understanding the context in which a pregnancy occurs requires a more nuanced examination. In-depth interviews were conducted with 60 men and women, aged 18-35, who had children or were pregnant. Using grounded theory analysis, themes emerged that revealed participants’ ideal criteria desired before pregnancy. We stratified by those who met and did not meet these criteria. Almost universally, participants shared ideal criteria: to graduate, gain financial stability, establish a relationship, and then become pregnant. Many participants did not accomplish these goals. Those who had not met their criteria had experienced traumatic childhoods and suffered economic concerns. For this group, having children prompted positive changes within their control, but financial stability remained limited. Efforts should focus on improving circumstances for all individuals to fulfill their criteria before pregnancy.

Keywords: family planning, pregnancy, qualitative research, family health

Introduction

Family formation decision-making is more complex than the predominant models of pregnancy intentions that have been used to capture this phenomenon in the United States (Aiken, Borrero, Callegari, & Dehlendorf, 2016; Luker, 1999; Sable, 1999). Pregnancy intention measures often force a dichotomization of pregnancy intendedness based on active cognitions, categorized as unintended (mistimed or unwanted) or intended (Santelli et al., 2003). Commonly studied factors in pregnancy decisions include: partner influences, societal norms, inner desire for parenthood, external demands of parenthood, financial needs and attitudes about career (Barrett, Smith, & Wellings, 2004; McQuillan, Greil, & Shreffler, 2011a; Miller, in preparation). These are often examined to develop an understanding of what factors women and couples considered before becoming pregnant. This operating framework posits that becoming pregnant is a decision in which the benefits and drawbacks of having children are weighed by an individual or couple and subsequently incite action (Hall, 2012). This conceptualization, though, does not account for the dynamic social, financial and other contextual variables that may affect those living at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum differently than the socioeconomically advantaged (Kendall et al., 2005; Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006). Further, it infers that, without exception, people actively engage in thinking about pregnancy prior to initiating sex.

The predominant intentions-oriented framework for studying pregnancy assumes a rational model of decision-making. In this way, it promotes interventions to reduce unintended pregnancy by increasing knowledge of and access to contraception. Unfortunately, many of these intervention efforts have been unsuccessful (Becker, Koenig, Kim, Cardona, & Sonenstein, 2007; Kirby, 2008), perhaps because they fail to address how the larger social determinants of health, including the way in which broader contextual factors, such as life experiences or financial expectations, can influence sexual behavior and family formation (Marmot & Wilkinson, 2006). Using an alternate framework that assesses this social context may provide a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of how people approach family formation.

Preliminary research suggests that individuals have personal criteria they would like to fulfill prior to forming a family (Borrero et al., 2015; Manze, McCloskey, Bokhour, Paasche-Orlow, & Parker, 2016). Using this framework, and examining who can and cannot meet their personal criteria before childbearing as well as the social contexts in which they live, can help health professionals and researchers better understand what structural and social changes are needed in order to help people have children under their own ideal conditions.

Although there has been some preliminary qualitative research that suggests the pregnancy intentions framework does not align with how people approach pregnancy (Barrett & Wellings, 2002; Borrero et al., 2015; McQuillan, Greil, & Shreffler, 2011b), there remains a dearth of qualitative research providing an in-depth understanding of contextual influences among individuals across different racial/ethnic groups, income, and education levels related to becoming pregnant and forming families. Understanding the context in which a pregnancy occurs, and childrearing thereafter, requires a more nuanced examination (Bachrach & Newcomer, 1999; Gipson, Koenig, & Hindin, 2008; Luker, 1999; Sable, 1999). Qualitative methods are well suited to capture this nuance, given the open-ended nature of in-depth interviewing (Tolley, Ulin, Mack, Robinson, & Succop, 2016); Corbin & Strauss, 2007).

Our research takes a new approach to understanding how circumstances and events in peoples’ lives are related to family formation and their perceived role as a parent. In this qualitative exploration, we will investigate how and why some participants were able to meet their ideal criteria before pregnancy and others were not, within the context of social, family, environmental, financial, and cultural factors. In doing so, we employ a new framework to allow for a more realistic understanding of how women and men conceptualize getting pregnant. Research in this area has been predominantly quantitative (Gipson et al., 2008; Santelli et al., 2003) and focused on women (particularly women of color and those with low income) (Aiken, 2015; Ewing et al., 2017; Finer & Zolna, 2011; Paterno, Hayat, Wenzel, & Campbell, 2017; Wolfe, 2003), despite family formation being a behavior enacted by those of all genders. Our approach allows us to glean how pregnancy happens in the daily lives of individuals, in their relationships, families, and social environments. This work is intended to offer an alternate way to conceptualize the experience of becoming pregnant and having children, as embedded in one’s life context and trajectory of life events. This can facilitate an improved understanding of the determinants of pregnancy among women and men of different socioeconomic positions to inform more appropriate and effective interventions than those that currently exist. Thus, we hope to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of influences that can determine if, how, and when to effectively intervene to prevent pregnancies heretofore labeled as unintended, attributed to poor or no planning, and viewed as problematic.

Methodology

Study Design and Sampling Frame

The Social Position and Family Formation (SPAFF) study is a cross-sectional, in-depth interview (IDI) study of 200 heterosexual men and women, aged 18-35 years. We sought to draw a diverse sample of participants across racial/ethnic, income, and educational backgrounds, as well as different relationship statuses, from the New York metropolitan area.

We used a population-based approach to establish the sampling frame from which participants were recruited by examining the demographic profile of New York City (NYC) and northern New Jersey (NJ) based on the racial/ethnic, income, and educational distribution of the population. We examined demographic data from the 42 neighborhoods in the NYC Community Health Survey and from the American Community Survey to inform selection of potential neighborhoods for data collection in NYC and NJ, respectively. The final sampling frame included the following neighborhoods: Lower East Side of Manhattan, Northwest Brooklyn, Southwest and Central Queens, Fordham and Bronx Park and Jersey City, NJ. The objective was to recruit participants from neighborhoods that had demographic characteristics similar to NYC or northern NJ overall. This study was approved by the Hunter College Institutional Review Board. A more detailed account of the sampling methodology is described elsewhere (Romero et al, 2019, as are related analyses (Manze et al, 2019; Melnikas et al, 2019)).

Data Collection

The IDIs were conducted in 2011 by an extensively trained team of interviewers who were graduate (mostly doctoral) students in the social sciences and public health. Individuals were recruited from various public venues (e.g., cafes, salons, libraries, fitness centers) in the selected neighborhoods in an effort to draw a community-based sample. (Recruitment procedures are also described in detail elsewhere (Romero et al., 2019)). Participants completed a short screener to determine eligibility, which included data on gender, income, race/ethnicity, age, borough of residence, children, and current relationship status. A semi-structured interview guide was used to explore topics related to family-formation decision-making, including relationships, pregnancy, parenting, career, finances, and education. Among the questions included were: 1) How does your income/financial situation factor into your thinking about children? 2) How do your work/career/educational goals factor into your thoughts about children? and, 3) What do you think is a good age and situation for having a child? Interviews were conducted and digitally recorded (for transcription purposes) either in the participant’s home or in public settings conducive to interviewing, and two were conducted via Skype. All interviews lasted approximately one hour. Participants were given a $5 gift card for the completion of the initial screener and $45 for their participation in the interview, which recognized the extra time and effort expended by participants to either host the interview in their private homes or make arrangements to travel to a different location on a different day to participate in the interview.

Analysis

This analysis of IDI data is from a parent study broadly examining how social position influences decisions related to family formation. For this paper our analysis specifically focused on issues related to ideal and actual pregnancy circumstances. We analyzed data from a subset of respondents (n=60) who reported having children or were pregnant/had a pregnant partner, in order to capture participants who had lived experiences with getting pregnant. Interviews were coded first by generally identifying all discussions of considerations in pregnancy and parenting. The research team coded the transcripts using techniques informed by grounded theory, an approach which allows theory to be generated based on emergent themes that are grounded in the data rather than by testing a priori hypotheses (Charmaz, 2006; Corbin & Strauss, 2007; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). To achieve theory development, an inductive and iterative process from ‘repeating ideas’ to theme to construct was used (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003; Charmaz, 2006). This allowed analysis to move to higher levels of abstraction in order to facilitate greater understanding of complexities of ideal and actual pregnancy experiences. Data were coded and recoded according to definitional shifts in the developing themes and constructs, until the analysis team agreed upon a final coding structure with operational code definitions.

One of the key themes that emerged from this iterative coding process began as being labeled ‘criteria for pregnancy readiness’ (e.g., finances, career, education, partner influences). Next, these ‘criteria’ were discussed and revised among the coding team members to begin assemblage of a higher order concept that was labeled as ‘ideal criteria for family formation.’ Once this key construct was identified and defined, all interviews were re-coded according to the final coding structure.

In addition to marked discussions of having ideal criteria, participants shared whether or not these criteria were met before having children. Given the prominence of this division within the sample, we chose to use this construct of ideal criteria as the guiding framework for our analysis, segment the sample, and explore circumstances and contextual issues in the lived experiences of those who did and did not meet their own ideal criteria before their first pregnancy. Therefore, after each interview was coded, the analyst evaluated the participant’s own stated criteria and then assigned each participant to one of the following groups: having had a child 1) before, or 2) at/after their ideal criteria were met, herein referred to as the ‘ideal not met’ and ‘ideal met’ groups, respectively. The rationale for combining those who had children at or after their ideal criteria was namely to compare those who did not meet their ideal criteria to all others who had. A subsample of the assigned categories was then cross-checked by analysts to ensure reliability of category assignment. We excluded those who had foster children, whose only children were stepchildren, those who never wanted children but were forced to have them, those who had an abortion (and did not have any other children), and those for whom we could not determine if they had or had not met their ideal criteria before getting pregnant, after consultation with the research team (n=15). This allowed for a more appropriate sample that could be stratified by those who had met or did not meet their ideal pregnancy criteria for analysis of the underlying factorsi.

Codes and emerging themes were analyzed within and across these trajectory groups; we analyzed the transcripts for contextual factors and dominant themes related to pregnancy and parental role within each group. We retrospectively assessed their ideal criteria for pregnancy as well as other factors (e.g., social, family, environmental, financial, and cultural contexts) and reviewed how these factors differed by those who met their ideal criteria versus those who became pregnant before fulfilling their ideal criteria. Although participants were assigned as having met or not met their ideal criteria before their first pregnancy, other themes that emerged from the data were included regardless of being explicitly related to their pregnancy or ability to meet this criterion. This was intended to gain an in-depth understanding of participants’ daily lived experiences and contextual issues, such as social and financial factors, that may be related to the ability to meet their ideal criteria (even if not explicitly stated). To that end, we also captured discussion related to their perceived role of being a parent.

Concurrent to code structure development and the interview coding process, team members wrote detailed memos that captured emergent theories based on the data to help explain how and why some people were able to bear children based on their ideal criteria and others were not. Our approach to data collection, analysis, and reporting the findings was guided by recommended criteria for assessing quality in qualitative research. (Mays & Pope, 2000) Dedoose (version 4.9.0), a mixed-methods analytic tool, was used for all analyses. All names used to identify participants are pseudonyms, assigned by the participant him/herself or the researcher.

Results

Sample Description

We first present the quantitative findings for the total sample followed by the sociodemographic characteristics by those in the ideal met and the ideal not met groups (Table 1). Next, the qualitative thematic findings for both groups are presented (Table 2). Sixty participants met the inclusion criteria for this study. The majority of participants were female (71%) and married or living with a partner (54%). Many had a Bachelor’s degree or above (39%) and were an average age of 29 years. The sample was comprised of Hispanic (41%), African-American (37%), White (15%), Asian/Pacific Islander (5%) and Other (2%) individuals.

Table 1.

Sample Sociodemographic Characteristics by Pregnancy Criteria (n=60)

| TOTAL n (%)* |

Ideal Criteria Not Met (n=42) n (%)* |

Ideal Criteria Met (n=18) n (%)* |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | |||

| Female | 42 (71) | 31 (76) | 11 (61) |

| Male | 17 (29) | 10 (24) | 7 (39) |

| AGE (mean yrs) | 29 | 28 | 32 |

| RACE/ETHNICITY | |||

| African-American | 22 (37) | 18 (44) | 4 (22) |

| White | 9 (15) | 3 (7) | 6 (33) |

| Hispanic | 24 (41) | 19 (46) | 5 (28) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 3 (17) |

| Other/Multi | 1 (2) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) |

| INCOME | |||

| ≤$19,999 | 20 (35) | 20 (50) | 0 (0) |

| $20,000-$59,999 | 25 (43) | 18 (45) | 7 (39) |

| ≥ $60,000 | 13 (22) | 2 (5) | 11 (61) |

| EDUCATION | |||

| < High school (HS) completion | 5 (9) | 5 (13) | 0 (0) |

| HS diploma or GED | 7 (13) | 6 (15) | 1 (6) |

| Some college/technical school or Associates | 22 (39) | 19 (48) | 3 (19) |

| Bachelors or above | 22 (39) | 10 (25) | 12 (75) |

| RELATIONSIP STATUS | |||

| Married/living with partner | 32 (54) | 18 (44) | 14 (78) |

| Divorce or separated | 5 (9) | 4 (10) | 1 (6) |

| Single/Open relationship | 15 (25) | 13 (32) | 2 (1) |

| Committed relationship | 7 (12) | 6 (15) | 1 (6) |

May not sum to 100% due to rounding

Table 2.

Constructs, Themes and Codes by Pregnancy Criteria Groups

| Construct | Key Theme | Theme Description |

Ideal Criteria Not Met: Subcodes |

Ideal Criteria Met: Subcodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADVERSE EXPERIENCES | Traumatic life events | Substantial, life-altering or life-changing personal event |

|

|

| Stereotypes/discrimination | Beliefs/experiences related to stigma, race, gender or ethnicity |

|

||

| CONSIDERATIONS & NEEDS IN CHILDBEARING | Financial outlook | Impact of the current economic situation on having children | Financial Worries

|

Financial Aspirations

|

| Social influences | Pressures/obligations related to having children |

|

|

|

| Safety net | Safety net that people expect, need or used to support them & their family |

|

|

|

| CHANGES FOR CHILDREN | Transformation | Transformations related to having children | Personal change

|

Lifestyle change

|

Of those in the ideal not met group (n=42) most were African-American (44%) or Hispanic (46%), had an annual income of less than $20,000 (50%), some college or Associates degree (48%), and had a mean age of 28 years. In comparison, those in the ideal met group (n=18) had a mean age of 32 years, were distributed across all racial groups, were mostly married/living with a partner, had an annual income of $60,000 or more and had a Bachelor’s degree or more. Given the sample size, statistical comparisons between those who had met and did not meet their ideal criteria were not possible.

Qualitative Findings

Participants almost universally held the same ideal criteria for becoming pregnant, which were sequenced according to the following trajectory: to graduate from school, gain financial stability, establish a relationship, and then get pregnant and have children. Having such ideal criteria, however, did not always translate into individuals planning a pregnancy after their initial criteria were met. All participants had or were expecting children, yet only some were able to satisfy these criteria in the desired sequence prior to childbirth. The two quotes that follow are illustrative of the ideal not met and ideal met scenarios, respectively.

Juan, a young man living with his wife’s family due to financial constraints who did not meet his ideal criteria before his wife became pregnant, reflected:

“I did want to be financially, I guess, stable [before having a child]. I don’t want to say secure, but stable, like having a stable job, at least have to have my own place or car at least, a mode of transportation. I had planned it out, but, again, things don’t work out the way you plan it at times. I wouldn’t change it. I’m a firm believer that everything happens for a reason. It’s matured me.” –Hispanic, Male, 25 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

By contrast, Gerard, a married man who talks about how he always wanted kids and did meet his ideal criteria, noted:

“There was never really an age discussion; we knew that she had to be done with college and established in her job [before getting pregnant].” –White, Male, 35 yrs, >$60,000/yr

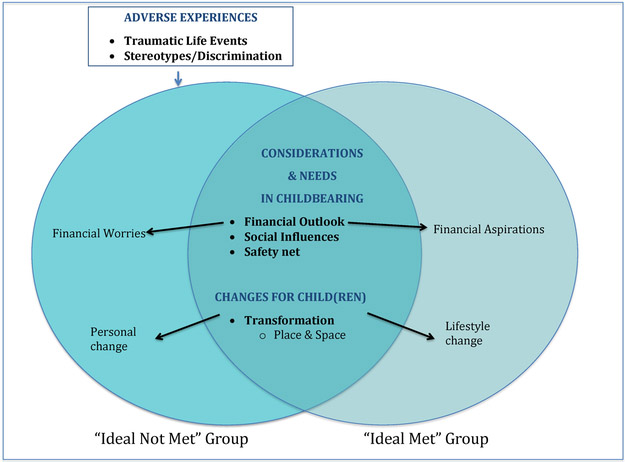

In-depth analysis of the coded data revealed six broad themes related to pregnancy and parenting that were subsumed within three main constructs in the following manner: Adverse Experiences (traumatic life events, stereotypes/discrimination), Considerations and Needs in Childbearing (financial outlook, social influences, safety net), Changes for Children (transformation) (Figure 1). Some of these themes were similar across both groups (financial outlook, social influences, needing a safety net, and having a child as a transformative event). However, the contexts within which these themes were discussed differed by group (Table 2). In addition, several themes were only present in the ideal not met group narratives, including responsibilities in molding a future generation, stereotypes in becoming pregnant, and personal traumatic events. Below we present each of the three overarching constructs, the key themes within them and the ways in which they are either similar or different across groups based on having met (or not met) one’s ideal criteria for childbearing. Thus, the analysis comparing those in the “ideal met” and “ideal not met” groups is embedded within the presentation of each theme.

Figure 1.

Relationship of Contextual Factors and Effects of Pregnancy by Criteria Group

Adverse Experiences

Within the construct of adverse experiences, two themes emerged that only pertained to the ideal not met group. These themes were traumatic life events in the participant’s own childhood and perceptions of discrimination or stereotypes, often related to having children.

Traumatic Life Events.

Participants in the ideal not met group spoke of traumatic events in their own childhood, including periods of homelessness, exposure to or engagement in violent acts, incarceration, absent or abusive parents, and parental or personal substance abuse. Melissa, a single mother of two who was unemployed at the time of the interview, recounted her experience in an abusive relationship and being without housing for a year when she was pregnant:

“I’ve been independent since I got pregnant when I was 19 and I went and I left the house and I went into a homeless shelter. Specifically more because my boyfriend at the time was abusive so I had to go into a domestic [violence shelter] and that’s when I had my daughter.” –Hispanic, Female, 32 yrs, ≤$19,999/yr

Experiences such as this were not always discussed within the context of plans to have children or to parent. In some cases, though, they explicitly prompted the desire for a stable and reliable partner, or to be better parents themselves, in order to spare their children the traumatic events they experienced growing up. Jakob, who was abandoned by his parents at age 14 and homeless for two years, noted:

“I think it’s because of those experiences that I went through, I don’t want my son to ever go through that. I don’t want my kids to ever say that dad wasn’t there for them.”

–Hispanic, Male, 27 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

Stereotypes/Discrimination.

Several participants also felt as if they were targets of stereotypes or discrimination. With regard to the potential for being viewed as a stereotype, several participants spoke about feeling ashamed or anticipating judgment as a result of becoming parents before meeting their ideal criteria. Several spoke about how men of color are stereotyped as being absent, uninvolved, and financially unsupportive of their children. Ryan, who was homeless at the time his son was born, was keenly aware of this stereotype and explained his struggle to defy the odds stacked against him:

“Being somebody’s husband and father you got to know what you are doing. Know how to get that money. Always have a plan…started figuring out things. It’s like certain tribes who throw a young boy out into the jungle and he comes back a man…I knew there was nobody there for me so I had to do things myself. I made sure I wasn’t going to be another statistic. I was already a statistic in some ways, but I was going to figure out a way to know the system and not let the system get me.” –African-American, Male, 22 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

Considerations and Needs in Childbearing

Financial Outlook.

Participants’ considerations of finances were directly queried and, thus, were prevalent in the interviews. Monetary issues were clearly evident in discussions about having children but presented differently for those able and not able to meet their ideal criteria prior to having a child. Those in the ideal not met group talked about financial worries, whereas those in the ideal met group discussed financial aspirations or lack of concern about their finances. For those in the ideal not met group, financial concerns related to providing the basic necessities for their children. They discussed wanting financial stability prior to further childbearing. These participants also discussed concerns about debt, including school loans.

Tata, a single mother who had her daughter at 16 years old, felt overwhelmed with financial worries related to raising a child:

“Money, money. Money, money don’t grow on trees. You have to have money for everything. Every little thing, like if the baby have a rash, you got to buy the cream. Cream ain’t cheap. You got to buy $8.00 cream. Diapers…they’re expensive. They’re like $40 each box…If you don’t have WIC, you have to buy that milk. Those things are $10 for a little can, and that little can goes out to five or six bottles. You’ve got to buy about $20 a day…Clothes. You don’t want your baby looking all ratty… Everything. Babysitting is money. Toys, everything, the light bill, everything.” –Hispanic, Female, 20 yrs old, $20,000–59,999/yr

Participants in the ideal met group held a financial outlook that encompassed lifestyle changes that accompany having children, and not about financial concerns. Their apprehensions included being able to afford the additional space to accommodate children and an upgrade in neighborhood. For example, Sharon, who is from England and felt the maternity leave policies in the U.S. were unreasonably short, discussed considerations in having more children:

“I think the reality is if we have another child we’ll probably be looking to another apartment, and we probably [will] be looking to stay in the city somewhere in a bigger apartment, probably, within a public school area. That’s probably, like, the golden triangle where we are trying to get to which is probably where everyone is trying to get to, too…there are sort of complicating factors are just you know how do you afford the next level of accommodation? And you know what financial situation are you in? And what do I do when I have another kid? Do I stop working and if so then how do you afford that next level of accommodation?” –White, Female, 33 yrs, >$60,000/yr

Social Influences.

Participants felt influenced by various social groups. For those whose ideal criteria were not met, family and partner influences were more prominent, whereas cultural and peer influences applied more to the ideal met group. Respondents who had children before their ideal criteria were met also articulated pride in molding the next generation. Providing an environment for their children more stable than the one they had been exposed to themselves, with more opportunities for high-quality education and social mobility, became a primary goal. Many respondents felt privileged to be a key player in molding a future generation and thus felt obligated to provide the best possible environment to nurture their children. Tonya described ‘hanging out in the streets’ during her own childhood, while her father was incarcerated. Her narrative encompasses the notion of wanting to provide more for her own children:

“I want to go back to school and I want to better myself so I can be able to take care of me and my son better. And not have him have to go through stuff that I went through as a child. Not having enough or not having anything. That’s basically it…. I worry about my son growing up in this environment….I want to do better for him. I want him to be able to grow up in a better life than I did. Again, I was on my own since I was 14. I don’t want my son to be on his own when he is 14 years old. I don’t want him to have to do things to make money just because I don’t have it or I can’t afford it. You know? That’s not what I want for him. I want to better myself so he can live good and he can have a better life….He makes me really want to do it like now and not two years from now, not later, now. Right now.” –Hispanic, Female, 26 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

The narratives of respondents who had met their ideal criteria were more focused on cultural and peer pressures to have children, and considerations for becoming pregnant in the context of siblings. Peter, married to Sharon, quoted above, with one daughter, described these pressures:

“I think we probably felt in a good way forced into having a baby because a) her age, b) our age, c) everyone else had already done it, not [her] close friends but mine were probably all onto kid number two, so it seemed really natural.” –White, Male, 34 yrs, >$60,000/yr

Safety Net.

Both the ideal met and not met groups discussed needing some form of safety-net as support for their child(ren). The government and family were the primary safety nets for the ideal not met group, necessary in terms of financial and child care support. For some participants, the government provided needed financial support for which recipients were thankful, but they were embarrassed to need this support. Ryan, also quoted above, revealed the emotional impact of needing government assistance:

“I had to go on welfare. It’s so degrading the way they talk to you. They are very rude, nasty people. They treat you like you are nothing. The government…. Now you see what it is like to be on the bottom. When you are on the bottom you can see everybody on the top.” –African-American, Male, 22 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

Immediate family members were cited as providing childcare and, sometimes, financial support for their children. Below Blue described the social support she received from her family while raising her son:

“My mom, I think everyone did their part. My brothers, my aunts, because I was going back and forth to school and I was working a full time job, so babysit and pick-ups from daycare and drop off at daycare. So I had a lot of assistance which I guess is why I give back the way I do. ‘Oh you all was there for me.’ So now that my little brothers and my brothers have kids now, it’s like ‘Oh, yeah. I’ll babysit.’ Because they’re like ‘We did it for you when we was young and you was only 18 and we was 12 and 13.’ I’m like ‘Oh, okay.’ So now they got kids and I’m like ‘yeah, I’ll babysit.’”–African-American, Female, 30 yrs, $20,000-$59,999

Among those whose ideal criteria were met, participants also spoke of needing family as a support system. Parents were the main providers of such support through regular childcare or “helping out” when needed. Kerri, who became pregnant with her son as she was finishing her Master’s degree, noted:

“My parents live close to me as well. They take care of my son, which they are of great help. Very important. It’s the closest bond I have- my family.” –Hispanic, Female, 30 yrs, >$60,000

Those in the ideal met group did not have prominent discussions of needing financial or government support.

Changes for Children

Transformation.

Both groups discussed transformations that occurred as a result of having a child. For those who did not meet their ideal criteria, this was a personal transformation about becoming more mature as a parent. For those who did meet their ideal criteria, theirs was more of a lifestyle transformation.

As opposed to those who did not meet their ideal criteria, those in the ideal met group did not discuss the personal or internal changes that accompanied having a child. Instead, they spoke about structural or external change. Agnes, who has two children, stated:

“I always picture myself in a house, so I think that’s one of my other goals of getting is something, not in the city, per se, more likely on the [outskirts] of the city, maybe in Westchester or Long Island. So, hopefully, I’m in a house, because living in an apartment is not fun with two children.” –Hispanic, Female, 32 yrs, $20,000-$59,999/yr

Their concerns were focused on moving into nicer neighborhoods and having more space than they currently do.

Although the large majority of the sample (70%) had children prior to when their ideal criteria had been met, they spoke about having children as a positive, transformative event that prompted personal change and maturity. One man, John Doe, whose family is from Honduras and who has two children, discussed how having a family incited this type of change:

“…I mean, in this world, these days I think I need a family. I don’t know where I’d be. I wouldn’t be the person I am today. I would be a lot worse. They helped me get back on track. They saved my life. Things that I was doing I would have ended up dead or in jail, stuff like that. They definitely helped me step back, appreciate life, value it more than I was.” –Hispanic, Male, 24 yrs,≤$19,999/yr

Becoming pregnant triggered motivations to gain financial stability, relocate to a more desirable neighborhood and, in some cases, move out of their parent’s/their partner’s parent’s house and into a place of their own. Having a child was the impetus for these changes, namely to ensure that their child was safe and had access to high-quality education. Melissa, who experienced domestic violence during her first pregnancy and had periods of homelessness, relayed:

“I wanted to be a role model for my daughter. So I’ve got myself a little apartment from there I could afford with the Section 8 program that I had let’s say, just earned at the homeless shelter being there a year. I used that and I just studied. I studied and I graduated. I was for two years, I felt rehabilitated from my life in the past....”

–Hispanic, Female, 32 yrs, ≤$19,999/yr

Participants felt they were successful in this transformation mostly due to behavioral changes that involved less ‘partying’ and becoming what they perceived as a responsible parent. In most cases, though, participants continued to struggle financially; making the economic transformation a reality remained a challenge. Their universal goal, however, of becoming financially stable and moving into a safer neighborhood, remained.

Discussion

Participants universally shared an ideal trajectory of wanting children after completing their education, establishing a career, and gaining financial stability, similar to other qualitative findings (Borrero et al., 2015; Manze et al., 2016). However, in comparing those who did and did not meet these criteria, the findings point to the divergent experiences, considerations, and perceptions of being a parent between the two groups. Their distinct life experiences, considerations, and needs in childbearing signal factors that may have influenced their ability to meet such criteria before forming families.

In our analysis of life experiences and contextual factors among the two trajectory groups, we found that those who did not meet their ideal criteria before becoming pregnant held financial concerns and felt compelled to provide a better lifestyle for their offspring than the one they experienced as children. Despite this, those who had children before their ideal criteria were met talked retrospectively about having a child as a transformative experience that prompted motivations for positive behavior change and pursuing financial stability, echoing earlier findings (Kavanaugh, Kost, Frohwirth, Maddow-Zimet, & Gor, 2017; Shanok & Miller, 2007). Participants were often successful in executing the desired behavior changes that were within their control, such as less ‘partying,’ but the pursuit of financial stability remained a challenge.

In addition, the men and women who did not meet their ideal criteria also reported exposure to significant adverse events in their lives, such as violence, addiction, periods of homelessness and having neglectful or abusive parents – that is, major, negative life events largely outside of their control. Though not stated explicitly, these experiences may have influenced a perception of limited control (or having an external locus of control) (Rotter, 1966) over the ability to plan future life events, such as pregnancy and family formation. Other findings have alluded to perceived control as an influence in pregnancy (Barrett & Wellings, 2002; Cubbin et al., 2002; Dodson, 1998; Kendall et al., 2005; Moos, Petersen, Meadows, Melvin, & Spitz, 1997). For example, in her examination of poor young women, Dodson found that “…how girls come to know their role and place in the world when there is no tangible path to college and career affected how girls understand the notion of choice [in pregnancy]” (Dodson, 1998). Thus, the construct of intention, as currently employed in pregnancy research, may not be relevant for individuals who, despite having specific ideal criteria before becoming pregnant, do not necessarily plan if and when to have children (Luker, 1999; Moos et al., 1997). Our findings are consistent with another study that found structural and individual level factors affect women’s ability to delay pregnancy until their ideal circumstances are fulfilled (Kendall et al., 2005); our analysis extends beyond that of Kendall et al. given our socioeconomically diverse sample of men and women, and our stratification by ideal pregnancy criteria.

Those who did not meet their ideal criteria before childbearing had a higher proportion of those of lower income, with lower levels of education, who were not married, and people of color, similar to the disproportionate rates of unintended pregnancy among these groups (Finer & Zolna, 2016). Framing pregnancy by people’s ability to meet their ideal criteria (versus “intentions”) allows for a contextualized understanding of the structural and social factors driving family formation. This reframing will allow more appropriate interventions to support the range of family formation pathways, including pregnancy and pregnancy prevention, for individuals of all backgrounds. In this way, this framework is consistent with the construct of pregnancy ‘supportability,’ recently introduced as an alternative to the intentions framework (Macleod, 2016). ‘Supportability’ is proposed as a framework to assess the person, micro, and macro-level social and structural determinants of pregnancy, and thus highlight the areas of needed support for preventing or maintaining a pregnancy. Assessing ability to meet one’s ideal criteria before family formation (or expansion) can be considered one component of this framework and reveal needed supports, in order to improve reproductive autonomy and reproductive health outcomes (Elsenbruch et al., 2007).

These findings should be interpreted within the limitations of the study. There may be recall bias in participants’ ability to accurately reconstruct their ideal criteria before becoming pregnant. Social desirability bias may be present if participants thought that the interviewers expected them to have ideal criteria prior to pregnancy. While some might worry about the potential for socially desirable responses pertaining to childbearing (e.g., providing a romanticized view of pregnancy before ideal criteria are met), we did not identify this in the data overall nor differentially between those whose ideal criteria had been met versus not met. In addition, given that most participants did not meet their criteria, we do not believe that post-rationalization of meeting criteria before pregnancy was over-reported. All participants included in the analysis had children or were currently pregnant, but were interviewed at different points in their lives. This could influence how participants talked about having children and the impact that had on them. In order to minimize the effect of this variation across individuals, we categorized individuals as ideal criteria met and not met based on their first child. The other themes that emerged in the data provide context when examining those who did and did not meet their ideal criteria. We do not, however, make claims about their causing individuals to be able to meet their ideal criteria (or not) before becoming pregnant. Further research is needed to conduct an in-depth interrogation as to how socioeconomic circumstances influence the ability to fulfill one’s ideal criteria prior to childbearing. Although the inferential transferability of our findings is limited to those living in a large, urban setting, the results have theoretical transferability in informing our understanding the circumstances surrounding childbearing (Lewis, Ritchie, Ormston, & Morrell, 2014).

These findings provide an in-depth understanding of contextual factors, experiences and beliefs of those who did and did not follow their own desired criteria before becoming pregnant. This contributes to the current literature that has begun to recognize the currently incomplete understanding of the phenomenon of becoming pregnant for people with different life circumstances and creates a starting point to re-conceptualize how we frame, study, and discuss how women and men think about pregnancy. The findings also reveal the distinct perceptions, concerns, and transformations that having a child brings, among those who do and do not meet their ideal criteria for childbearing. Future research can further explore which specific factors are associated with being able to meet one’s ideal criteria before pregnancy, in order to effectively intervene so that individuals and couples can follow supportive pathways to family formation (including pregnancy prevention) under their ideal circumstances. Assessing the social and structural context of who is able to meet these criteria and why can provide researchers and policymakers with an understanding of the social and structural changes that may be needed to help individuals have children under their own ideal conditions.

The findings suggest a redirection of the ‘intentions’ approach used to understand pregnancy. Instead, a focus on ascertaining the criteria under which individuals would like to become pregnant and form families should be a starting point. Future research can examine if and how meeting these criteria is associated with maternal and child health outcomes.

The results point to needed structural and social level supports, such as increased government benefits, quality jobs, and safe, affordable housing, in order to help people meet their criteria and support families. Providing linkage to relevant resources may be more successful in helping people become pregnant after ones’ ideal criteria have been met, than approaches primarily if not exclusively centered on contraceptive knowledge and access. Using a framework of ideal criteria for pregnancy met or not met may more effectively identify the underlying issues related to timing of pregnancy and allow researchers and health care providers to shift their efforts from measuring intendedness to supporting the ideal conditions under which pregnancy occurs for individuals.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amy Kwan, MPH, who in her capacity as research manager of the Social Position and Family Formation (SPAFF) study, provided invaluable assistance with issues pertaining to the dataset as well as technical and conceptual support in the early phase of analysis. This work was supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under grant #K01 HD055263 (PI: Romero, D). The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

The study design sought to recruit individuals for analysis (not couples). Despite two couples (i.e., four individuals) being included in the sample, each transcript was analyzed independently.

References

- Aiken AR (2015). Happiness about unintended pregnancy and its relationship to contraceptive desires among a predominantly latina cohort. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47(2), 99–106. doi: 10.1363/47e2215 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken AR, Borrero S, Callegari LS, & Dehlendorf C (2016). Rethinking the pregnancy planning paradigm: Unintended conceptions or unrepresentative concepts? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 48(3), 147–151. doi: 10.1363/48e10316 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach C, & Silverstein L (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach CA, & Newcomer S (1999). Intended pregnancies and unintended pregnancies: Distinct categories or opposite ends of a continuum? Family Planning Perspectives, 31(5), 251–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett G, Smith SC, & Wellings K (2004). Conceptualisation, development, and evaluation of a measure of unplanned pregnancy. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(5), 426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett G, & Wellings K (2002). What is a ‘planned’ pregnancy? empirical data from a British study. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 55(4), 545–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker D, Koenig MA, Kim YM, Cardona K, & Sonenstein FL (2007). The quality of family planning services in the United States: Findings from a literature review. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 39(4), 206–215. doi: 10.1363/3920607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, Freedman L, Akers AY, Ibrahim S, & Schwarz EB (2015). “It just happens”: A qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception, 91(2), 150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2014.09.014 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (introducing qualitative methods series) (1st ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, & Strauss A (2007). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Cubbin C, Braveman PA, Marchi KS, Chavez GF, Santelli JS, & Gilbert BJ (2002). Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in unintended pregnancy among postpartum women in california. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 6(4), 237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson L (1998). Choice and motherhood in poor America. Don’t call us out of name: The untold lives of women and girls in poor america (pp. 83–113). Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan P (1999). The ‘illegitimacy bonus’ and state efforts to reduce out-of wedlock births. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(2), 94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsenbruch S, Benson S, Rucke M, Rose M, Dudenhausen J, Pincus-Knackstedt MK, Klapp BF, & Arck PC (2007). Social support during pregnancy: Effects on maternal depressive symptoms, smoking and pregnancy outcome. Human Reproduction (Oxford, England), 22(3), 869–877. doi:del432 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing AC, Kottke MJ, Kraft JM, Sales JM, Brown JL, Goedken P,Wiener J, & Kourtis AP (2017). 2GETHER - the dual protection project: Design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial to increase dual protection strategy selection and adherence among african american adolescent females. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 54, 1–7. doi:S1551–7144(16)30099–4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, & Zolna MR (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception, 84(5), 478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013; 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, & Zolna MR (2016). Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. The New England Journal of Medicine, 374(9), 843–852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson JD, Koenig MA, & Hindin MJ (2008). The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: A review of the literature. Studies in Family Planning, 39(1), 18–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B, & Strauss A (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hall KS (2012). The health belief model can guide modern contraceptive behavior research and practice. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 57(1), 74–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00110.x; 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00110.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanaugh ML, Kost K, Frohwirth L, Maddow-Zimet I, & Gor V (2017). Parents’ experience of unintended childbearing: A qualitative study of factors that mitigate or exacerbate effects. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 174, 133–141. doi:S0277–9536(16)30704–3 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall C, Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Avery A, Schmidt N, & Santelli J (2005). Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans--results of qualitative research. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 60(2), 297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby D (2008). The impact of programs to increase contraceptive use among adult women: A review of experimental and quasi-experimental studies. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 40(1), 34–41. doi: 10.1363/4003408; 10.1363/4003408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Ritchie J, Ormston R, & Morrell G (2014). Generalising from qualitative research. In Ritchie J, Lewis J, Nicholls C & Ormston R (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students & researchers (2nd ed., ) [Google Scholar]

- Luker KC (1999). A reminder that human behavior frequently refuses to conform to models created by researchers. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(5), 248–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod CI (2016). Public reproductive health and ‘unintended’ pregnancies: Introducing the construct ‘supportability’. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 38(3), e384–e391. doi:fdv123 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manze M, McCloskey L, Bokhour BG, Paasche-Orlow MK, & Parker VA (2016). The perceived role of clinicians in pregnancy prevention among young Black women. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 8, 19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.srhc.2016.01.003 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manze M, Watnick DL, & Romero DR (2019) A qualitative assessment of perspectives on getting pregnant: the Social Position and Family Formation study. Reproductive Health. 16:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, & Wilkinson RG (2006). Social determinants of health (Second ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N, & Pope C (2000). Qualitative research in health care. assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 320(7226), 50–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J, Greil AL, & Shreffler KM (2011a). Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: Focusing on women who are okay either way. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 178–187. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0604-9; 10.1007/s10995-010-0604-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J, Greil AL, & Shreffler KM (2011b). Pregnancy intentions among women who do not try: Focusing on women who are okay either way. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 178–187. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0604-9 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melnikas AJ, Romero DR Ideal age at first birth and associated factors among young adults in greater New York City: findings from the Social Position and Family Formation study. Journal of Family Issues, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miller W (in preparation). Chapter 1: The reasons people give for having children. Why we have children: Building a unified theory of the reproductive mind. Aptos, CA: Transnational Family Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Moos MK, Petersen R, Meadows K, Melvin CL, & Spitz AM (1997). Pregnant women’s perspectives on intendedness of pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues : Official Publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women’s Health, 7(6), 385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterno MT, Hayat MJ, Wenzel J, & Campbell JC (2017). A mixed methods study of contraceptive effectiveness in a relationship context among young adult, primarily low-income African American women. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 4(2), 184–194. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0217-0 [doi] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero DR, Kwan A, & Suchman L (2019) Methodologic approach to sampling and field-based data collection for a large-scale in-depth interview study: The Social Position and Family Formation (SPAFF) project. PLoS One, 14(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotter J (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychology Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1–28) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sable MR (1999). Pregnancy intentions may not be a useful measure for research on maternal and child health outcomes. Family Planning Perspectives, 31(5), 249–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Gilbert BC, Curtis K, Cabral R, Hirsch JS, Schieve L, & Unintended Pregnancy Working Group. (2003). The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 94–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah PS, Balkhair T, Ohlsson A, Beyene J, Scott F, & Frick C (2011). Intention to become pregnant and low birth weight and preterm birth: A systematic review. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 15(2), 205–216. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0546-2 [doi] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanok AF, & Miller L (2007). Stepping up to motherhood among inner-city teens. Psychology of Women Quartlerly, 31(3), 252–261. [Google Scholar]

- Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, & Succop SM (2016). Qualitative methods in public health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe WA (2003). Overlooked role of African-American males’ hypermasculinity in the epidemic of unintended pregnancies and HIV/AIDS cases with young African-American women. Journal of the National Medical Association, 95(9), 846–852. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]