Abstract

Background

Life expectancy of individuals with spina bifida has continued to improve over the past several decades. However, little is known about the longitudinal course of scoliosis in individuals with myelomeningocele (MMC), a spina bifida subtype, across their lifespan. Specifically, it is not known whether management during or after the transition years from adolescence to adulthood is associated with comorbidities in adulthood nor if these individuals benefit from scoliosis treatment later in life.

Questions/purposes

In this systematic review, we asked: (1) Is the risk of secondary impairments (such as bladder or bowel incontinence, decreased ambulation, and skin pressure injuries) higher among adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis than among those with MMC without scoliosis? (2) Is there evidence that surgical management of scoliosis is associated with improved functional outcomes in adolescents and adults with MMC? (3) Is surgical management of scoliosis associated with improved quality of life in adolescents and adults with MMC?

Methods

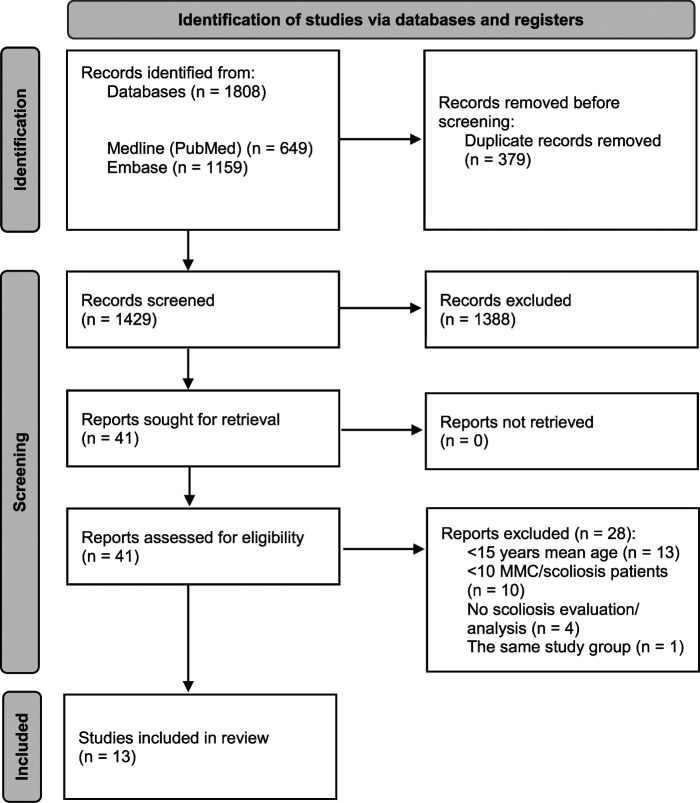

We performed a systematic review of articles in Medline and Embase from 2000 until February 5, 2021. Search terms such as “spinal dysraphism,” “spina bifida,” “meningomyelocele,” and “scoliosis” were applied in diverse combinations. A total of 1429 publications were identified, and 13 were eligible for inclusion. We included original studies reporting on scoliosis among individuals older than 15 years with MMC. When available, we extracted the prevalence of MMC and scoliosis, studied population age, percentage of patients experiencing complications, functional outcomes, and overall physical function. We excluded non-English articles and those with fewer than 10 individuals with scoliosis and MMC. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses, and registered the review before data collection (PROSPERO: CRD42021236357). We conducted a quality assessment using the Methodologic Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) tool. In 13 included studies, there were 556 individuals with MMC and scoliosis. Most were retrospective case series, although a minority were retrospective/comparative studies. The mean MINORS score was 12.3 ± 1.65 (a MINORS score over 12 generally is considered good reporting quality, scores below 12 are considered at high risk of bias).

Results

In general, studies found that individuals with MMC and scoliosis were more likely to have secondary impairments such as bladder/bowel incontinence, decreased ambulation, and pressure injuries than were patients with MMC without scoliosis. These secondary impairments were associated with hydrocephalus and high-level MMC lesions. However, when one study evaluated mortality, the results showed that although most deceased individuals who had spina bifida had scoliosis, no association was found between the age of death and scoliosis. Among the studies evaluating functional outcomes, none supported strong functional improvement in individuals with MMC after surgery for scoliosis. No correlation between the Cobb angle and sitting balance was noted; however, the degree of pelvic obliquity and the level of motor dysfunction showed a strong correlation with scoliosis severity. There was no change in sitting pressure distributions after spinal surgery. The lesion level and scoliosis degree independently contributed to the degree of lung function impairment. Although studies reported success in correcting coronal deformity and stopping curve progression, they found no clear benefit of surgery on health-related quality of life and long-term outcomes. These studies demonstrated that the level of neurologic function, severity of hydrocephalus, and brainstem dysfunction are greater determinants of quality of life than spinal deformity.

Conclusion

This systematic review found that adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis are more likely to have secondary impairments than their peers with MMC only. The best-available evidence does not support strong functional improvement or health-related quality of life enhancement after scoliosis surgery in adolescents and adults with MMC. The level of neurologic dysfunction, hydrocephalus, and brainstem dysfunction are greater determinants of quality of life. Future prospective studies should be designed to answer which individuals with MMC and scoliosis would benefit from spinal surgery. Our findings suggest that the very modest apparent benefits of surgery should cause surgeons to approach surgical recommendations in this patient population with great caution, and surgeons should counsel patients and their families that the risk of complications is high and the benefits may be small.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Myelomeningocele (MMC), an important subtype of spina bifida, has an estimated birth prevalence of 0.8 to 1 cases per 1000 live births [13]. Among the three main spina bifida types (spina bifida occulta, meningocele, and MMC), MMC is the most severe form. It results in secondary conditions including neurologic disorders, orthopaedic abnormalities, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and the risk of skin pressure injury. Scoliosis is one of the most common and severe orthopaedic co-occurring conditions among individuals with MMC, with an estimated proportion as high as 50% in this group [25, 32]. It further varies by neurologic level of involvement, with thoracic functional level of involvement having the highest incidence of scoliosis at approximately 90% [24, 37]. The scoliosis management in this population is complex. Although there is a consensus that brace treatment does not halt curve progression, surgery carries a high risk of complications including infection, pressure sores, nonunion, failure of instrumentation, and even death [5, 14, 19]. At the same time, the potential effects of untreated scoliosis are thought to include changes in cardiopulmonary function, chest wall deformity, diminished truncal height, alteration in sitting balance, cosmetic deformity, and disruption to self-image, physical function, and health-related quality of life [26].

In part because of advances in health services (including comprehensive care from multidisciplinary teams), individuals with spina bifida are living longer, with most surviving well into adulthood [18, 33]. The combination of folic acid fortification efforts and recommendations for the use of prenatal folic acid supplementation have led to a decreased overall prevalence of neural tube defects at birth [8]. In addition, because of the advent of improved management strategies for neurogenic bladder and the evolution of treatments for hydrocephalus over many decades, life expectancy has improved [10]. Although more than 67% of the overall spina bifida population at present are adults [17, 29], it is likely that most of the individuals who have scoliosis have experienced most of their curve progression by 15 years of age [24]. However, despite advances in healthcare, little is known about the longitudinal course of scoliosis in individuals with spina bifida across their lifespan. Specifically, it is not known whether management during or after the transition years is associated with comorbidities in adulthood or if these individuals benefit from pediatric scoliosis treatment later in life.

We therefore performed a systematic review in which we asked: (1) Is the risk of secondary impairments (such as bladder or bowel incontinence, decreased ambulation, and skin pressure injuries) higher among adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis than among those with MMC without scoliosis? (2) Is there evidence that surgical management of scoliosis is associated with improved functional outcomes in adolescents and adults with MMC? (3) Is surgical management of scoliosis associated with improved quality of life in adolescents and adults with MMC?

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy and Information Sources

We performed a comprehensive search using the Medline (PubMed) and Embase databases. Also, we performed a maximally expanded search using the following terms: “spinal dysraphism,” “spina bifida,” “diastematomyelia,” “lipomeningocele,” “lipomyelomeningocele,” “meningomyelocele,” and “scoliosis” in diverse combinations following a search strategy described by McKibbon [21]. Our secondary search included an examination of the reference lists of all eligible articles. In addition, we used Google Scholar to complete an inquiry of recently published studies. The publications from these initial searches were screened to only include original English-language and full-length articles published between 2000 and 2021. The search was performed on February 5, 2021.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included original studies reporting on scoliosis in individuals older than 15 years with MMC. The exclusion criteria were studies with fewer than 10 individuals with MMC and scoliosis in the described cohort, studies with the same patient group as were reported on in another article, case reports, reviews, conference abstracts, preprint server posts, comments, editorials, and animal studies. The search was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Fig. 1) [23]. The method for the analysis and inclusion criteria were specified in advance and documented through a PROSPERO protocol (CRD42021236357).

Fig. 1.

This PRISMA flow diagram shows our study search.

Screening and Selection Process

Two authors (VB, EF) independently screened the titles and abstracts for full-article review. After a further screening by the same authors, any incongruencies were presented to a third reviewer (JC), and the three authors reached a consensus about ultimate inclusion through rounds of discussions.

Study Quality Assessment

A level of evidence was assigned to each study according to the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume, Level of Evidence guidelines [41]. One author (VB) quantitatively assessed the quality of included studies using the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) checklist [35]. A score of 12 is considered to be of low quality (high risk of bias), whereas a study with MINORS score greater than 12 is thought to be of higher quality. Noncomparative studies received an ideal score of 16, and comparative studies received an ideal score of 24. Generally, studies were attributed to high quality with a mean MINOR score of 12.3 ± 1.65 (Appendix 1; http://links.lww.com/CORR/A705). Eleven studies were classified as level of evidence IV and two were level of evidence III.

Study Characteristics

We identified 1429 reports, 41 of which met the criteria for full-text review; 13 were determined to be eligible for inclusion in this systematic review (Fig. 1). In sum, there were 556 individuals with MMC and scoliosis in the included studies. Eleven articles (531 individuals) had data relevant to our first research question, three articles (67 individuals) were relevant to research question 2, and two articles (64 individuals) were relevant to question 3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study comparison table

| Author, year; journal | Number of individuals | Type of study/level of evidence | MINORS score | Studied population age | Purpose | Individuals with scoliosis | Results or conclusions |

| McDonnell and McCann [20], 2000; Child’s Nervous System | 237 with SB; 211 with MMC (193 were reviewed for pressure injuries and musculoskeletal problems) |

Retrospective case series/IV | 10 | 14 to 59 years (mean 28.1 years) | To evaluate the clinical and demographic profile of adults with SB and hydrocephalus, particularly their needs. | Scoliosis was present in 48% (92 of 193), and 67% (129 of 193) had joint deformities or contractures. For 4.1% (8 of 193), pressure sores and skin breakdown were currently a problem, and they had been a problem in a further 38.3% (74 of 193). | This study reflects the considerable range of disabilities in adults with SB, the challenges presented in long-term management, and the need for organized follow-up. The authors believe that the multidisciplinary model of care must be considered just as relevant for adults with SB as it is for children. |

| Bowman et al. [4], 2001; Pediatric Neurosurgery | 71 with MMC | Retrospective case series/IV | 10 | 19.4 to 24.8 years (mean 21.7 years) | To report the 20-year to 25-year outcome of individuals with MMC treated in a nonselective, prospective manner. | Forty-nine percent (35 of 71) patients had scoliosis, with 43% (15 of 35) eventually undergoing spinal fusion. Eighty-seven percent (13 of 15) had fusion at the thoracic motor level. | At least 75% of children born with an MMC can be expected to reach their early adult years. Late deterioration is common. |

| Trivedi et al. [37], 2002; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, American Volume |

141 with MMC | Retrospective case series/IV | 15 | 10 to 42 years (mean 19 years) | To identify clinical and radiographic factors that may predict the onset of developmental scoliosis in individuals with MMC. | Fifty-two percent (74 of 141) had scoliosis. Scoliosis developed before the age of 9 years in 58% (43 of 74) individuals and after the age of 9 years in 42% (31 of 74), with new curves continuing to develop until 15 years old. |

In individuals with MMC, the term scoliosis should be reserved for curves of > 20°. New curves may continue to develop until the age of 15 years. The level of the last intact laminar arch is a useful early predictor of the development of scoliosis in these individuals. |

| Özerdemoglu et al. [30], 2003; Spine | 112 with syringomyelia; 27 with MMC |

Retrospective comparative study/III | 15 | Follow-up: 2 to 45 years (mean 12.9 years). Mean age at the time of diagnosis of scoliosis: 8.7 years (0-54 years). Mean age at the time of diagnosis of syringomyelia:14.2 years (0.1-49 years). Mean age at the onset of neurologic deficits: 15.2 years (0.3-49 years). Mean age at onset of pain: 18 years (3-48 years). |

To review individuals with scoliosis associated with syringomyelia. To analyze the indirect etiologic factors of scoliosis, as well as the relationship between the curve, syrinx, presence of neurologic deficits, and other additional pathologic conditions. |

All 100% (112 of 112 ) had scoliosis. Group 1: 56% (63 of 112) with neither congenital scoliosis nor MMC. Group 2: 20% (22 of 112) with congenital scoliosis, but no MMC. Group 3: 20% (22 of 112) with MMC, but no congenital scoliosis. Group 4: 4% (5 of 112) with both congenital scoliosis and MMC. |

The apex, the upper-end, and lower-end vertebrae of the curve were more caudally located in Group 3 than in Groups 1 and 2: upper-end vertebrae, lower-end vertebrae, and apex of the curve. Likewise, the length of the curve was longer in Group 3 than in Groups 1, 2, and 4. Individuals with MMC had a longer scoliosis curve because tethering of the spinal cord seems to be the main parameter that increases the length of the curve. |

| Verhoef et al. [38], 2004; Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology |

179 with SB; 109 with MMC | Observational cross-sectional study/III | 12 | 16 to 25 years (mean 20.9 years) | To examine the prevalence of secondary impairments in young adults with SB and to relate the prevalence to the type of SB and level of lesion. | Fifty-two percent (57 of 109) had scoliosis. In SB aperta with hydrocephalus, 41% (49 of 119) had scoliosis. For those with a high-level lesion (Level 2 and above), obvious scoliosis could be diagnosed in 59% (43 of 73). Problems with sitting balance were present only in these two groups. |

Most secondary impairments were found for individuals with SB aperta with hydrocephalus, and individuals with SB aperta without hydrocephalus were mostly comparable to individuals with SB occulta. According to the level of lesion, most medical problems were found in the high-level lesion group. |

| Ouellett et al. [28], 2009; Spine | 19 with MMC | Retrospective case series/IV | 13 | 9 to 21 years (mean 15.6 years) | To examine whether greater scoliosis curve correction with third-generation spinal implants correlates with improved pressure distribution and resolution, or prevention of skin ulcerations in individuals with MMC. | One hundred percent (19 of 19) wheelchair-dependent individuals with MMC and scoliosis who underwent spinal surgery were prospectively followed with regular pressure mappings for a minimum of 2 years. | Despite surgical correction in radiographic parameters, there were small changes in pressure distributions. Pressure mapping may not be a useful tool in predicting the outcome of spinal surgery. Skin ulceration is probably a result of multiple factors, and spinal deformities may not be the critical factor. Factors that were proven to influence pressure distribution are the sagittal pelvic orientation and achieving coronal spine balance. |

| Bartnicki et al. [2], 2012; Ortopedia Traumatologia Rehabilitacja |

19 with MMC | Retrospective case series/IV | 12 | 13 to 35 years (mean 21.5 years) | To assess the influence of sitting stability in skeletally mature individuals on their quality of life and general physical function and to assess the relationship between sitting balance and the severity of scoliosis or other disorders of individuals with MMC. | One hundred percent (19 of 19) had scoliosis. None of the individuals had been surgically treated for spine deformity. The mean Cobb angle was 77.5° (30°-120°). |

The value of the Cobb angle is not a good indicator of sitting balance in individuals with scoliosis and MMC, as well as walking ability, presence of pressure sores, and age. The statistical analysis showed that sitting stability assessed by examiners or parents was positively correlated with overall quality of life, general physical function, pelvic obliquity measured by the Osebold method, and the level of motor spine dysfunction. |

| Sibinski et al. [34], 2013; Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B | 19 with SB; 11 with stable sitting and 8 with poor sitting (0 with no sitting stability) |

Retrospective comparative study/III | 11 | 13 to 35 years (mean 21.4 years) | To assess the quality of life, physical function, self-motivation, and self-perception of skeletally mature individuals with SB and scoliosis | One hundred percent (19 of 19) of individuals had SB, were skeletally mature, and had scoliosis. | Authors found no association between spinal deformity or other features related to SB and self-perception, motivation, and overall physical function. More severe scoliosis affects quality of life and is related to the degree of pelvic obliquity and the age of the individual. Most limitations in individuals with SB were not related to the degree of scoliosis but to other associated disabilities. |

| Werhagen et al. [39], 2013; Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery | 127 with SB; 114 with MMC | Retrospective comparative study/III | 11 | 18 to 50 years (mean 34 years) | To evaluate the prevalence of different medical complications in an SB cohort to increase knowledge in adults with SB. | Thirty percent (38 of 127) with scoliosis. Urinary tract infection, scoliosis, and pain were the most common complications, in 46% (58 of 127), 30% (38 of 127), and 28% (36 of 127) of the individuals, respectively. Less common complications were epilepsy in 11% (14 of 127), pressure ulcers in 9.5% (12 of 127), and spasticity in 6% (7 of 127). |

SB leads to disability including motor and sensory dysfunction, and individuals suffer from a high frequency of medical complications such as urinary tract infections, scoliosis, pain, and epilepsy. Data provide the basis for adequate routines for medical examination at follow-up. |

| Khoshbin et al. [15], 2014; The Bone and Joint Journal | 45 with SB; 34 in operative group and 11 in nonoperative | Retrospective comparative study/III | 12 | 18.8 to 34.7 years (mean 27.0 years) | To evaluate the health-related quality of life outcomes of adults with SB who had been treated either operatively or nonoperatively for scoliosis during childhood. | One hundred percent (45 of 45) of individuals: 75.6% (34 of 45) had been treated operatively and 24.4% (11 of 45) were treated nonoperatively. |

Both groups were statistically similar at follow-up with respect to walking capacity, neurologic motor level, sitting balance, and health-related quality of life outcomes. Spinal fusion in SB corrects coronal deformity and stops progression of the curve but has no clear effect on health-related quality of life. |

| North et al. [27], 2018; Child’s Nervous System | 147 with MMC: Group 1: 101 Group 2: 46 |

Retrospective comparative study/III | 13 | Group 1: 8.6 to 19.6 years (mean 13.4 years) Group 2: 10.5 to 20 years (mean 15.7 years) |

To examine trends over time in the incidence and outcomes of MMC in British Columbia. | Group 1: 42% (42 of 101) were documented as having some form of kyphoscoliosis and 38% (16 of 42) had orthopaedic instrumentation for correction. Group 2: 50% (23 of 46) had kyphoscoliosis and 30% (7 of 23) had orthopaedic instrumentation for correction. |

The incidence of new-onset MMC decreased between 1971 and 2016, while the probability of survival for these individuals increased. Despite earlier and more universal postnatal repair, long-term outcomes did not improve over time. |

| Crytzer et al. [9], 2018; Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine | 29 with SB; 26 with MMC |

Observational cross-sectional study/III | 14 | 17 to 71 years (mean 30.48 years) | To describe the pulmonary function of adolescents and adults with SB. To determine the impact of neurologic level of spinal injury, scoliosis, and obesity on the severity and pattern of lung function impairment. |

There were 62.1% (18 of 29) of individuals with scoliosis with a Cobb angle < 19°, 10.3% (3 of 29) with 20° to 45°, and 27.6% (8 of 29) with > 45°. In multivariate models, the level of lesion and degree of scoliosis independently contributed to the degree of lung function impairment. |

A high prevalence of restrictive pulmonary complications was present in people with SB, with more-rostral neurologic levels and greater degree of scoliosis associated with a higher degree of pulmonary function impairment. |

| Dicianno et al. [11], 2018; American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation | 487 with SB; 36 deceased individuals with MMC and 12 deceased individuals without MMC |

Retrospective comparative study/III | 12 | 20.5 to 89.4 years (mean 40.9 years) | To identify secondary conditions and medical comorbidities in adult individuals with SB and to determine which factors were associated with an earlier age at the time of death. | Among deceased individuals, 75% (36 of 48) had an MMC (mean age 41.6 years) and 77% (37 of 48) had scoliosis (mean age 42.9 years). There was no association between age at the time of death and a tethered spinal cord (p = 0.550), scoliosis (p = 0.197), or abnormal renal function (p = 0.509). |

In a sample of deceased adults with SB, earlier age at the time of death was associated with a history of hydrocephalus, Chiari II malformation, and the MMC subtype. |

The MINORS had a possible score of 24 for comparative studies (Level II) and 16 for noncomparative studies (Levels III and IV); higher scores represent better study quality. A score of 12 or less is considered to indicate a study with low quality (high risk of bias), whereas MINORS scores of greater than 12 are thought to have a lower risk of bias and higher reporting quality; SB = spina bifida; MMC = myelomeningocele; MINORS = Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies.

Individuals with both spina bifida and scoliosis represented the total study cohort (100%) in five articles [2, 15, 28, 30, 34], at least half of the cohort (50% to 75%) in six articles [4, 9, 11, 20, 27, 37], and approximately one-third of the cohort (30% to 32%) in two articles [15, 30]. In addition, five studies consisted entirely of individuals with MMC [2, 4, 27, 28, 37], five consisted primarily of individuals with MMC [9, 11, 20, 38, 39], and two consisted of patients with spina bifida cystica [15, 34]. One study had individuals with scoliosis and associated syringomyelia as a main criterion for inclusion; 24% (27) of individuals had MMC in that cohort [30]. Studies varied in the participants’ mean age: four articles described cohorts of patients between 15 and 19 years old [27, 28, 30, 37], six studies consisted of participants in their 20s [4, 9, 11, 27, 28, 34], and three articles consisted of individuals in their 30s and older [9, 11, 39]. A by-gender analysis was not conducted because of heterogeneity of studies and incompleteness of reports. All but two articles were retrospective [9, 38].

Four studies [11, 20, 38, 39] reported secondary impairments, comorbidities, and complications that are common among mature individuals with spina bifida and scoliosis. Five studies [2, 9, 28, 30, 37] assessed functional outcome associated with scoliosis, with two studies [2, 28] using pressure mapping to evaluate sitting stability and its influence on general function. One study used spirometry and body plethysmography lung testing to describe pulmonary function in adolescents and adults with spina bifida and scoliosis [9]. Two studies assessed the quality of life, physical function, self-motivation, and self-perception of skeletally mature patients with spina bifida and scoliosis using questionnaires [15, 34].

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

Our primary study goal was to compare the risk of secondary impairments in adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis to those with MMC only. Five studies were used to inform this comparison [4, 11, 30, 37, 38].

Our secondary study goal was to compare the possible improvement in functional outcome and quality of life after surgical management of scoliosis in individuals with MMC to those with MMC without scoliosis. Two studies were used to inform each of these comparisons [2, 15, 28, 34].

Results

Secondary Impairments, Comorbidities, and Complications

In general, studies found that patients with MMC and scoliosis were more likely to have secondary impairments such as bladder/bowel incontinence, decreased ambulation, and pressure injuries than were patients without scoliosis [4, 11, 30, 37, 38]. In patients with spina bifida and mean age of 21 to 43 years, the incidence of scoliosis was reported to be 30% to 77% [4, 11, 20, 27, 38, 39]. Data reflected a considerable range of disability among adults with spina bifida; in general, increasing levels of disability were more frequently seen among patients with hydrocephalus and those with high-level MMC lesions [11, 20, 38, 39]. Pressure injuries were noted to range from 22.2% (10 of 45) to 42% (8 of 19) [2, 15, 28], nonambulatory status varied from 63% (12 of 19) to 86% (25 of 29) [2, 9, 15, 28, 34], and high-level lesions occurred in 47% (9 of 19) to 71% (32 of 45) [2, 9, 15, 28, 34]. One study reported that among individuals with spina bifida, the percentage of those having had scoliosis surgery was highest among individuals with high-level lesions (41%) and hydrocephalus (27%). In addition, more secondary impairments existed in these two groups [38]. The only study that evaluated mortality in adults with spina bifida showed a mean age at death of 44.4 years, with 77% (37 of 48) of patients having scoliosis. However, no association was found between the patient’s age at the time of death and scoliosis [11].

Functional Outcomes

Among the studies that evaluated functional outcomes [2, 9, 28], none found substantial functional improvement in individuals with MMC treated for scoliosis. There was no change in sitting pressure distributions after spinal surgery, despite surgical correction of the Cobb angle (52%), pelvic obliquity (89%), and, to a lesser degree, pelvic tilt [28]. There was no correlation between the Cobb angle (mean 77.5°) and sitting balance in a study of patients with no previous operative treatment; however, the degree of pelvic obliquity and the level of motor dysfunction showed a strong correlation with scoliosis severity [2]. Pulmonary function testing performed on adults with spina bifida and scoliosis showed that the lesion level and scoliosis degree independently contributed to the degree of lung function impairment [9].

Quality of Life

Although studies [15, 34] reported success in correcting coronal deformity and stopping curve progression, they found no clear benefit of surgical treatment on health-related quality of life. These studies demonstrated that the level of neurologic function, severity of hydrocephalus, and brainstem dysfunction are greater determinants of quality of life than spinal deformity. In adults who had not undergone operative treatment, although more severe scoliosis affected their quality of life, the degree of scoliosis had no impact on self-perception, self-motivation, or physical function [34]. The only factor that affected physical function was a higher level of motor lesion (above L3). In contrast, a study that compared operative and nonoperative groups concluded that both groups were statistically similar at follow-up with respect to walking capacity, neurologic motor level, sitting balance, and health-related quality of life outcomes, whereas there was no association between the Cobb angle and health-related quality of life [15]. Although the study did not question the beneficial role of the scoliosis surgery for these individuals, it reported frequent complications and no clear benefit in terms of health-related quality of life after a mean follow-up of 14.1 years.

Discussion

Most individuals with spina bifida survive into adulthood [4, 27]. In contrast to an adolescent idiopathic scoliosis prevalence of 0.47% to 5.2% [16, 26] and the 8% prevalence of scoliosis among adults older than 25 years in the general population [6], some 30% to 48% of adult patients with spina bifida have scoliosis [20, 39]. Despite advances in healthcare, little is known about the longitudinal course of scoliosis in individuals with spina bifida across patients’ lifespans, the association with comorbidities in adulthood, or the benefit of surgical treatment of scoliosis later in life among patients with spina bifida. In our systematic review of the best-available evidence, we found that individuals with MMC and scoliosis were more likely to have secondary impairments such as bladder/bowel incontinence, decreased ambulation, skin pressure injuries, and high-level lesions than were individuals with MMC without scoliosis. Among the studies that evaluated functional outcomes, none found substantial functional improvement in individuals with MMC treated for scoliosis. Although studies regarding scoliosis surgery reported success in correcting coronal deformity and stopping curve progression, they found no clear benefits of treatment in terms of health-related quality of life. Our findings suggest that surgeons should counsel patients and their families that the risk of complications after spinal surgery in patients with MMC and scoliosis is high and the benefits may be small.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, only two included studies were multicenter and most were small, which limited or prevented meaningful statistical comparisons. However, as we refrained from pooling the data, the aim of our systematic review was to accumulate the source studies and resolve possible controversies using the best-available evidence in a more qualitative way. Second, because of inconsistent study quality, heterogeneity of study designs and endpoints, and most importantly, the lack of randomization among the source studies, we could not perform a formal meta-analysis; this precluded the quantitative assessment of effect sizes. Still, we believe that our qualitative assessments of the results reported in the source studies allowed us to answer our research questions as well as could be done given the limitations of those studies. Third, all but two of the included articles were retrospective, which readers should consider as they evaluate our recommendations and conclusions. In general, retrospective studies have inconsistent selection criteria for study inclusion, indications for surgery that may vary over time, follow-up that is not always fully documented, and endpoints that may be subjectively measured or measured without validated outcomes tools. All of these drive the apparent findings toward inflating the benefits of surgery. Therefore, considering the biases (specifically selection bias, transfer bias, and assessment bias) that are common among retrospective studies, the apparent benefits of surgery in our systematic review are likely inflated. Insofar as our systematic review generally did not find large improvements in function or health-related quality of life after scoliosis surgery in adolescents and adults with MMC, the fact that the apparent benefits of surgery may have been overstated in the source studies because of those kinds of biases should cause surgeons to approach surgical recommendations in these settings with great modesty. Finally, nonstandardized disease definitions and inconsistencies in reported complications made comparisons among articles challenging. This, as well, would tend to result in an underestimation rather than an exaggeration of the frequency of possible complications, which should further push surgeons toward modesty in their recommendations.

Secondary Impairments, Comorbidities, and Complications

Although children and adolescents with spina bifida often undergo many high-risk procedures, a reported complication proportion of 40% to 58% for spinal fusion sets this procedure apart as one that is particularly risky, and the longitudinal outcomes associated with operatively and nonoperatively treated scoliosis should be considered carefully [1, 12]. Among patients with hydrocephalus and a high-level lesion, one study [38] documented a higher percentage of scoliosis surgery in those patients who were the most susceptible to secondary complications.

However, when one study [11] evaluated mortality, the results showed that although most deceased individuals who had spina bifida had scoliosis, no association was found between the age of death and scoliosis. These results likely reflect a greater burden of disease in patients who died younger rather than a cause-effect relationship between scoliosis and death.

Functional Outcomes

The articles included in this study reported little or no functional improvement in patients treated with spinal fusion, despite a reduction in the Cobb angle [2, 28]. A study with nonoperatively managed individuals [2] showed no correlation between the Cobb angle and sitting balance, although pelvic obliquity correlated with sitting balance. Moreover, another study limited to patients managed surgically [28] reported no postoperative change in the distribution of pressure while sitting. Furthermore, this study mixed patients undergoing kyphectomy with those undergoing scoliosis correction. Thus, to date there are inadequate studies to delineate the relationship between scoliosis correction and sitting balance/pressure distribution in adolescents and adults with MMC. One cross-sectional study [9] showed that the degree of scoliosis independently contributed to the degree of lung function impairment, although neurologic level played the strongest role in pulmonary restriction. However, in another study not included in our review because of its younger patient population [31], no association was found between scoliosis and pulmonary restriction. Given a retrospective study design as well as differences in age and ambulatory status among the studied populations, their findings are difficult to compare with those in this report. Yet, since complications are common, and functional benefits currently appear limited, surgeons are well advised to be discerning when considering recommending these procedures. Consequently, further studies should consider the long-term effect of untreated scoliosis and the potential role of surgery in preventing late decline in pulmonary function.

Quality of Life

The findings of two studies [15, 34] support the idea that neither spinal deformity nor scoliosis surgery has a defining role on self-perception, motivation, or overall physical function in individuals with spina bifida. Another study [2] similarly found that although sitting stability was related to better quality of life and physical function, the Cobb angle was not a good indicator of balance, nor was it associated with quality of life, self-determination, or self-perception scores. Earlier, two systematic reviews raised the same question regarding the uncertain impact of the degree of scoliosis and spinal fusion on quality of life: one [22], with a Grade C recommendation, stated that spinal fusion does not improve quality of life in patients with spina bifida. Another [40], with a Grade I recommendation, concluded that the benefits of surgery for scoliosis in those with spina bifida are uncertain. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, no studies have used the Patient-Reported Outcomes Management Information System (PROMIS) analysis in adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis. Future evaluation of these individuals’ perspectives on their spine surgery and subsequent health-related quality of life, as well as analysis of differences between adolescents and adults with advancing age, would be of great importance for improvement in management of this condition.

Although the focus of this review was on the effect and treatment of scoliosis in adulthood, much of the evaluation and treatment for scoliosis should occur in younger people. The implementation of guidelines in medical care may reduce variation in clinical practice and lead to better health [36]. Our review suggests that the effects of scoliosis on an individual vary widely, and that it can be difficult to separate the effects of scoliosis from associations caused by the burden of MMC. The comorbidities associated with progressive scoliosis and the risks associated with spine surgery call for a strong partnership and care coordination between medical and surgical teams to deliver a patient-centered approach. Therefore, we suggest the most recent “Guidelines for the Care of People with Spina Bifida” (available at: https://www.spinabifidaassociation.org/resource/guidelines/) from the Spina Bifida Association [3, 7] as a resource for management of individuals with MMC in a multidisciplinary, team-oriented manner.

Conclusion

Although most studies on this topic were retrospective, the best-available evidence suggests that adolescents and adults with MMC and scoliosis are more likely to have secondary impairments than their peers who only have MMC. It does not appear that scoliosis surgery in adolescents and adults with MMC results in substantial improvements in patients’ function or health-related quality of life. Although scoliosis is among the most common and challenging comorbidities that individuals with MMC experience, it is not the only one. In contrast, studies demonstrated that the level of neurologic dysfunction, hydrocephalus, and brainstem dysfunction are greater determinants of quality of life than spinal deformity [15, 34]. Data regarding changes in sitting balance and pressure distribution after scoliosis correction in adolescents or adults with MMC is lacking but generally seems to suggest no improvement in pressure distribution [28]. Future studies in this area should focus on quality-of-life evaluation and patient-reported and functional outcomes. To determine the effect of pediatric scoliosis surgery on adolescents and adults with MMC, surgical and control groups should be matched with similar comorbidities and neurologic impairments. These cohorts should be evaluated for sitting position, pressure distribution, prevalence of pressure injuries, pulmonary function, and quality of life. Likewise, individuals who elect to undergo scoliosis correction as adolescents or adults should be prospectively studied pre- and postoperatively for possible improvements in pulmonary function, sitting position, and PROMIS scores. Results should be correlated with radiologic measures such as Cobb angle and pelvic obliquity. It will likely take collaboration between multiple centers to recruit adequate numbers of surgically managed individuals. Using this approach, future prospective studies may be able to answer which individuals with MMC and scoliosis would benefit from spinal surgery. Until or unless such benefits have been demonstrated, surgeons should avoid performing these procedures when possible, and surgeons should counsel patients and their families that the risk of complications after spinal surgery in patients with MMC and scoliosis is high and the benefits may be small.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Dormans MD for network integration and for initially providing the vision for this kind of collaboration and associated trainee education. We also thank Mark Dias MD, in the Department of Neurosurgery at Penn State College of Medicine and Penn State Hershey Children’s Hospital, for his assistance with this manuscript and for sharing his extensive expertise in neurosurgery.

Footnotes

One of the authors (BD) certifies receipt of personal payments or benefits, during the study period, in an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from Stryker Corp, in an amount of USD 10,000 to USD 100,000 from K2M, and in an amount of less than USD 10,000 from Medical Device Business Service.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Contributor Information

Viachaslau Bradko, Email: dr.bradko@gmail.com.

Heidi Castillo, Email: hacastil@texaschildrens.org.

Ellen Fremion, Email: ellen.fremion@bcm.edu.

Michael Conklin, Email: mconklin@uabmc.edu.

Benny Dahl, Email: btdahl@texaschildrens.org.

References

- 1.Banta JV, Drummond DS, Ferguson RL. The treatment of neuromuscular scoliosis. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:551-562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartnicki B, Synder M, Kujawa J, Stańczak K, Sibiński M. Sitting stability in skeletally mature patients with scoliosis and myelomeningocoele. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2012;14:363-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blount JP, Bowman R, Dias MS, Hopson B, Partington MD, Rocque BG. Neurosurgery guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13:467-477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman RM, McLone DG, Grant JA, Tomita T, Ito JA. Spina bifida outcome: a 25-year prospective. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;34:114-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carstens C, Schmidt E, Niethard FU, Fromm B. Spinal surgery on patients with myelomeningocele. Results 1971-1990 [in German]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1993;131:252-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter OD, Haynes SG. Prevalence rates for scoliosis in US adults: results from the first national health and nutrition examination survey. Int J Epidemiol. 1987;16:537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Conklin MJ, Kishan S, Nanayakkara CB, Rosenfeld SR. Orthopedic guidelines for the care of people with spina bifida. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2020;13:629-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crider KS, Bailey LB, Berry RJ. Folic acid food fortification-its history, effect, concerns, and future directions. Nutrients. 2011;3:370-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crytzer TM, Cheng Y-T, Bryner MJ, Wilson R, III, Sciurba FC, Dicianno BE. Impact of neurological level and spinal curvature on pulmonary function in adults with spina bifida. J Pediatr Rehabil Med. 2018;11:243-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis BE, Daley CM, Shurtleff DB, et al. Long-term survival of individuals with myelomeningocele. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dicianno BE, Sherman A, Roehmer C, Zigler CK. Co-morbidities associated with early mortality in adults with spina bifida. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;97:861-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geiger F, Parsch D, Carstens C. Complications of scoliosis surgery in children with myelomeningocele. Eur Spine J. 1999;8:22-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Greenberg F, James LM, Oakley GP. Estimates of birth prevalence rates of spina bifida in the United States from computer-generated maps. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;145:570-573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guille JT, Sarwark JF, Sherk HH, Kumar JS. Congenital and developmental deformities of the spine in children with myelomeningocele. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:294-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoshbin A, Vivas L, Law PW, et al. The long-term outcome of patients treated operatively and non-operatively for scoliosis deformity secondary to spina bifida. Bone Joint J. 2014;96:1244-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konieczny MR, Senyurt H, Krauspe R. Epidemiology of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Child Orthop. 2013;7:3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liptak GS, Robinson LM, Davidson PW, et al. Life course health and healthcare utilization among adults with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:714-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liptak GS, El Samra A. Optimizing health care for children with spina bifida. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16:66-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCarthy RE. Management of neuromuscular scoliosis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1999;30:435-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McDonnell GV, McCann JP. Issues of medical management in adults with spina bifida. Child’s Nerv Syst. 2000;16:222-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKibbon KA. Evidence-based practice. Bull Med Libr Assoc. 1998;86:396-401. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercado E, Alman B, Wright JG. Does spinal fusion influence quality of life in neuromuscular scoliosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:120-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller EB, Nordwall A. Prevalence of scoliosis in children with myelomeningocele in western Sweden. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17:1097-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller EB, Nordwall A, Odén A. Progression of scoliosis in children with myelomeningocele. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19:147-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negrini S, Donzelli S, Aulisa AG, et al. 2016. SOSORT guidelines: orthopaedic and rehabilitation treatment of idiopathic scoliosis during growth. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2018;13:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.North T, Cheong A, Steinbok P, Radic JA. Trends in incidence and long-term outcomes of myelomeningocele in British Columbia. Childs Nerv Syst. 2018;34:717-724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ouellet JA, Geller L, Strydom WS, et al. Pressure mapping as an outcome measure for spinal surgery in patients with myelomeningocele. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:2679-2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouyang L, Grosse SD, Armour BS, Waitzman NJ. Health care expenditures of children and adults with spina bifida in a privately insured U.S. population. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:552-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Özerdemoglu RA, Denis F, Transfeldt EE. Scoliosis associated with syringomyelia: clinical and radiologic correlation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28:1410-1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Patel J, Walker JL, Talwalkar VR, Iwinski HJ, Milbrandt TA. Correlation of spine deformity, lung function, and seat pressure in spina bifida. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1302-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piggott H. The natural history of scoliosis in myelodysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1980;62:54-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin M, Kucik JE, Siffel C, et al. Improved survival among children with spina bifida in the United States. J Pediatr. 2012;161:1132-1137.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sibinski M, Synder M, Higgs ZCJ, Kujawa J, Grzegorzewski A. Quality of life and functional disability in skeletally mature patients with myelomeningocele-related spinal deformity. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2013;22:106-109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies (MINORS): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soni SM, Giboney P, Yee HF. Development and implementation of expected practices to reduce inappropriate variations in clinical practice. JAMA. 2016;315:2163-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trivedi J, Thomson JD, Slakey JB, Banta JV, Jones PW. Clinical and radiographic predictors of scoliosis in patients with myelomeningocele. J Bone Joint Surg. 2002;84:1389-1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verhoef M, Barf HA, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA, Gooskens RHJM, Prevo AJH. Secondary impairments in young adults with spina bifida. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:420-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werhagen L, Gabrielsson H, Westgren N, Borg K. Medical complication in adults with spina bifida. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:1226-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wright JG. Hip and spine surgery is of questionable value in spina bifida: an evidence-based review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1258-1264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wright JG, Swiontkowski MF, Heckman JD. Introducing levels of evidence to the journal. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]