Abstract

Energy poverty is prevalent in resource-limited settings, leading households to use inefficient fuels and appliances that contribute to household air pollution. Randomized controlled trials of household energy interventions in low and middle income countries have largely focused on cooking services. Less is known about the adoption and impact of clean lighting interventions. We conducted an explanatory sequential mixed methods study as part of a randomized controlled trial of home solar lighting systems in rural Uganda in order to identify contextual factors determining the use and impact of the solar lighting intervention. We used sensors to track usage, longitudinally assessed household lighting expenditures and health-related quality of life, and performed cost-effectiveness analyses. Qualitative interviews were conducted with all 80 trial participants and coded using reflexive thematic analysis. Uptake of the intervention solar lighting system was high with daily use averaging 8.23 ± 5.30 hours per day. The intervention solar lighting system increased the EQ5D index by 0.025 [95% CI 0.002 – 0.048] and led to an average monthly reduction in household lighting costs by −1.28 [−2.52, −0.85] US dollars, with higher savings in users of fuel-based lighting. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the solar lighting intervention was $2025.72 US dollars per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained making the intervention cost-effective when benchmarked against the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in Uganda. Thematic analysis of qualitative data from individual interviews showed that solar lighting was transformative and associated with numerous benefits that fit within a Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework. The benefits included improved household finances, improved educational performance of children, increased household safety, improved family and community cohesion, and improved perceived household health. Our findings suggest that household solar lighting interventions may be a cost-effective approach to improve health-related quality of life by addressing SDOH.

Introduction

Energy poverty is prevalent in resource limited settings[1], leading households to use inefficient fuels or appliances that contribute to household air pollution. Household air pollution (HAP) is among the top 10 risk factors contributing to the global burden of disease[2], is associated with acute and chronic respiratory diseases in women. and is a leading cause of pneumonia in children. Most studies of the health impact of household air pollution focus on mitigating pollution exposure through promotion of more efficient stove technologies and fuels. The health benefit of these measures have been mixed[3–7], although trials of cleaner cooking fuels such as liquid petroleum gas are ongoing[8].

Qualitative methods have been applied to studies of improved cookstoves to elucidate use and end-user experiences[9]. Cost, taste, social norms, and adequate training strongly impact utilization of cookstoves[10, 11]. Importantly, although improved cookstove trials have been designed as a health intervention, in qualitative studies trial participants often view intervention stoves’ primary benefits in terms of reduced cooking times[12] and reduced fuel consumption[13] rather than for potential health benefits.

An often-overlooked but important source of HAP in some resource-constrained areas is kerosene-based lighting. Simple open-wick kerosene lamps and other fuel-based appliances are widely used in some off-grid households as a primary lighting source[14] and have been shown to contribute to HAP[15, 16]. Notably, fuel-based lighting is often most prevalent among the most impoverished and remote households; for example, in a recent observational study in Uganda, each increase in wealth quintile was associated with a decrease in the odds of using open wick kerosene lamps by 0.90 [0.84 – 0.96], p = 0.001)[17]. Early research suggests that existing solar lighting technologies may be a viable replacement for fuel-based lighting. Some of these studies have focused on the potential role of solar lighting in reducing exposure to household air pollution[17–19], while others have focused on high adoption rates, improved user satisfaction, long term cost savings on energy expenditure, and potential educational benefits for children[20–24]. Studies suggest that addressing energy poverty may improve overall well-being[25, 26].

The impact of public health interventions can be measured using various scales that assess domains of health-related quality of life among individuals. The EQ-5D instruments[27] are one of the most widely used health-related quality of life surveys that accounts for the domains of mobility, self-care, activities of daily living, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression in eliciting how an individual perceives their health status. The EQ-5D is the preferred instrument for global economic evaluations of health care due to the widespread availability of country-specific valuation sets that allow conversion of EQ-5D survey responses into quality adjusted life years (QALYs), a standardized measure of health status with one QALY being equivalent to one year of perfect health. QALYs are often used as the health utility measure in cost-effectiveness analyses to aid policy makers in decisions regarding resource allocation.

In this study, we employed an explanatory sequential mixed methods study design as part of a randomized controlled trial of solar lighting in rural Uganda in order to understand how contextual factors, such as poverty, cultural norms and existing energy infrastructure influence use and the impact of introduced lighting technologies. We quantitatively assessed utilization, health related quality of life, and household lighting expenditures and performed a cost-effectiveness analysis. In order to explain the quantitative findings, we qualitatively assessed end user experiences through thematic analyses of individual interviews that revealed the solar lighting intervention’s impact on the participants’ Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)[28].

METHODS

Study design and population

Between 2018 and 2019, we conducted a one-year parallel group, randomized wait-list controlled trial of indoor solar lighting systems in Nyakabare parish of southwest Uganda. We recruited 80 women aged 23 to 60 years old from 7 villages.

Following enrollment, home visits were conducted prior to randomization, and at 3, 6, and 12 months after randomization to administer surveys and gather data on use of the intervention lighting systems. At 9 months following randomization, we began conducting qualitative interviews with trial participants. At 14 months, approximately two months after the installation of solar lighting systems in the control group, a final field study visit was conducted.

Randomization and masking

Randomization was performed in a 1:1 ratio using a random number generator stratified by the participant’s primary lighting source (national electrical grid or battery-powered devices, solar lamps or systems, candles, hurricane kerosene lamps, and open wick kerosene lamps).

Intervention participants received an indoor solar lighting system at the time of randomization while control participants received the solar lighting system approximately 12 months after randomization. The nature of the study intervention prevented blinding of participants and field staff.

Procedures

The study intervention was an indoor solar lighting system costing $158 US dollars (USD) which was purchased by study staff from a local vendor based in Mbarara township (Allmar Solar Systems). The solar system comprised of a 30 watt-peak (Wp) solar panel, 18 Amp-hour (Ah) battery, 5 Amp charge controller, four lighting points, installation services, and included a two-year service warranty which covered costs of repairs and consumables such as lightbulbs.

Participants selected the location for each of the four bulbs in their homes at the time of installation. These lighting systems were deployed in the intervention households between February and April 2018. To provide equitable treatment for study participants, the control group also received the same solar lighting system between June and July 2019.

Quantitative methods

Monitoring of solar system utilization

At the time of solar system installation, we incorporated a sensor to track use. These four channel event loggers (Onset UX120–017) continuously monitored the dates and times when each light bulb for the intervention solar system was switched on and off for the entire study period. The hours of lighting use per day from each light bulb was subsequently calculated.

Administration of surveys

At baseline, 3, 6, 12, and 14 months after the study intervention, trained research assistants administered surveys in Runyankole, the local language, with responses recorded on an Android tablet using an offline survey app (QuickTapSurvey). Surveys administered included questions eliciting demographics characteristics, household assets, cooking practices, lighting practices, use of lighting sources, monthly expenditures on lighting, and health status using the EQ-5D-5L instrument. The EQ-5D-5L is a standardized instrument used worldwide to elicit an individual’s rating of their overall health at the time of survey completion in the domains of mobility, self-care, activities of daily living, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression[29], and combined with country or region specific valuation sets, is used in economic evaluations of health care interventions.

Qualitative methods

Individual interviews were conducted from January to July 2019 with all 80 participants enrolled in the randomized controlled trial. Ugandan research assistants conducted the interviews in the participant’s preferred language (typically Runyankole), using a semi-structured interview guide. All interviews were translated and transcribed into English verbatim within 72 hours of the interview (see Supplement for an example transcript). Following a reflexive thematic analysis approach, an in vivo coding framework was developed with codes grouped based on similarity of meaning into themes reflecting participants’ experiences with solar lighting. Reflexive thematic analysis of qualitative data emphasizes openness, questioning preconceptions and adopting a reflective attitude to understand meaning within the context of participants’ lived experiences [30–32]. During weekly conference calls between the U.S. and Ugandan teams, patterns in the data were discussed, and coding discrepancies resolved through consensus. Discrepancies in identified themes were rare, and in these instances, discrepancies were resolved through group discussion and consensus among the study team. A final list of themes was created, and study transcripts were coded using the final thematic scheme via Dedoose (Version 8.0.35). Participant quotations illustrating these themes were selected and are presented here to demonstrate concepts relevant to our study.

Statistical analysis

To estimate the effect of the study intervention on quality of life, we first converted EQ5D-5L survey responses to health utility scores. We used valuation weights from Ethiopia[33] given that these are the only valuation weights for Africa currently endorsed by the EuroQol group for the EQ5D-5L instrument. The resulting EQ5D index has a maximum score of 1 which indicates the best possible health state, whereas a score of 0 is deemed to be a health state equivalent to death.

Summary statistics were aggregated using mean (standard deviation) or number (percentage). The Supplement contains a detailed discussion of the statistical analyses. To identify correlates of use of the intervention solar system, and to determine the effect of the solar lighting intervention on health-related quality of life as measured by the EQ5D index and on monthly lighting expenditures, we used mixed effects models in order to account for repeated measures at the household or individual level. Cost effectiveness analyses from both the individual and societal perspectives, as well as analyses focused on the individual and governmental policy impacts of a conversion from kerosene to solar based lighting are further detailed in the Supplement.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

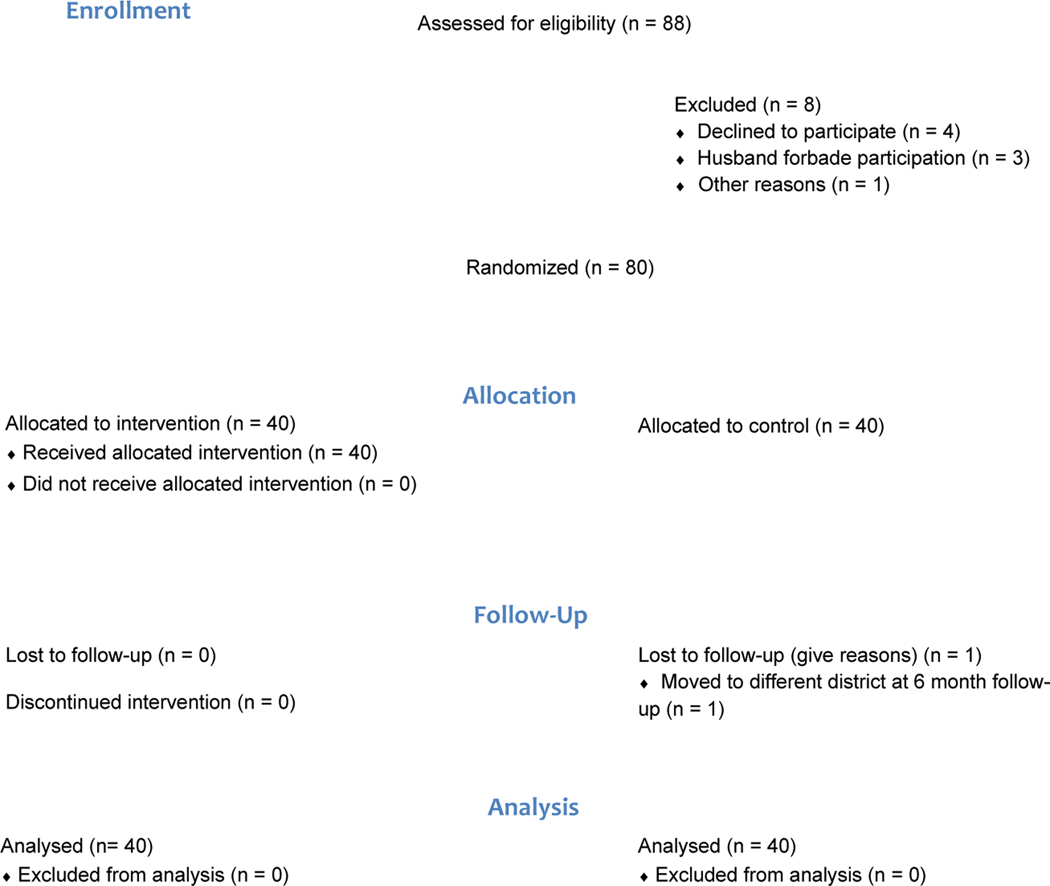

In January 2018, 88 women living in Nyakabare parish were assessed for eligibility, and 80 were successfully enrolled. Forty women were randomized to the intervention arm, and 40 to the control (Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the study cohort stratified by trial arm is depicted in Table 1. The cohort was composed of all women, 98.8% of whom were married or cohabiting, 13.8% with no and 86.2% with primary school level of education. Household assets such as car or motorcycle ownership were rare. On average 16.1 (standard deviation, 2.9) hours each day were spent indoors, with 4.8 (3.1) hours of self-reported baseline light use daily. The most common primary source of lighting was kerosene (41.2%) or solar based (33.8%), though simultaneous use of multiple lighting sources was common. Only 16.3% of participants had access to the national electrical grid. One participant was lost to follow-up (a control group participant at six months). There were no sensor failures leading to missing data in solar lighting use.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Study Flow Diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants.

| Control | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 40 | 40 |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 38.06 (7.38) | 41.30 (9.45) |

| Education (%) | ||

| None | 4 (10.0) | 7 (17.5) |

| Primary 1–2 | 12 (30.0) | 10 (25.0) |

| Primary 3–6 | 15 (37.5) | 13 (32.5) |

| Primary 7 | 9 (22.5) | 10 (25.0) |

| Marital status (%) | ||

| Married | 35 (87.5) | 36 (90.0) |

| Cohabiting | 4 (10.0) | 4 (10.0) |

| Separated/divorced | 1 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Land ownership (%) | 39 (97.5) | 39 (97.5) |

| Number rooms in house (mean (SD)) | 4.35 (1.23) | 4.20 (1.64) |

| Owns a radio (%) | 31 (77.5) | 31 (77.5) |

| Owns a motorcycle (%) | 6 (15.0) | 4 (10.0) |

| Owns a car (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) |

| Access to a ventilated improved pit latrine (%) | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Home has cement floors (%) | 6 (15.0) | 12 (30.0) |

| Wealth Quintile (mean (SD)) | 2.90 (1.24) | 3.08 (1.46) |

| Hours spent indoors daily (mean (SD)) | 15.81 (3.56) | 16.43 (2.11) |

| Self-reported hours of light use daily (mean (SD)) | 4.35 (2.81) | 5.15 (3.36) |

| Primary lighting source (%) | ||

| Candles | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.5) |

| Kerosene (open-wick) lamp | 12 (30.0) | 12 (30.0) |

| Kerosene (hurricane) lamp | 4 (10.0) | 5 (12.5) |

| Flashlight | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Solar panel powered bulbs | 14 (35.0) | 13 (32.5) |

| Electrical bulbs (national grid) | 6 (15.0) | 7 (17.5) |

| Secondary lighting sources | ||

| Candles | 5 (12.5) | 3 (7.5) |

| Kerosene (open-wick) lamp | 23 (57.5) | 19 (47.5) |

| Kerosene (hurricane) lamp | 13 (32.5) | 9 (22.5) |

| Flashlight | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Solar panel powered bulbs | 14 (35.0) | 15 (37.5) |

| Electrical bulbs (national grid) | 5 (12.5) | 4 (10.0) |

| Primary cook in house (%) | 40 (100.0) | 38 (95.0) |

| Cooking fuel type (%) | ||

| Charcoal | 1 (2.5) | 2 (5.0) |

| Firewood | 39 (97.5) | 37 (92.5) |

| LPG/Natural gas | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.5) |

Note only women were recruited for this study.

Solar lighting patterns of use

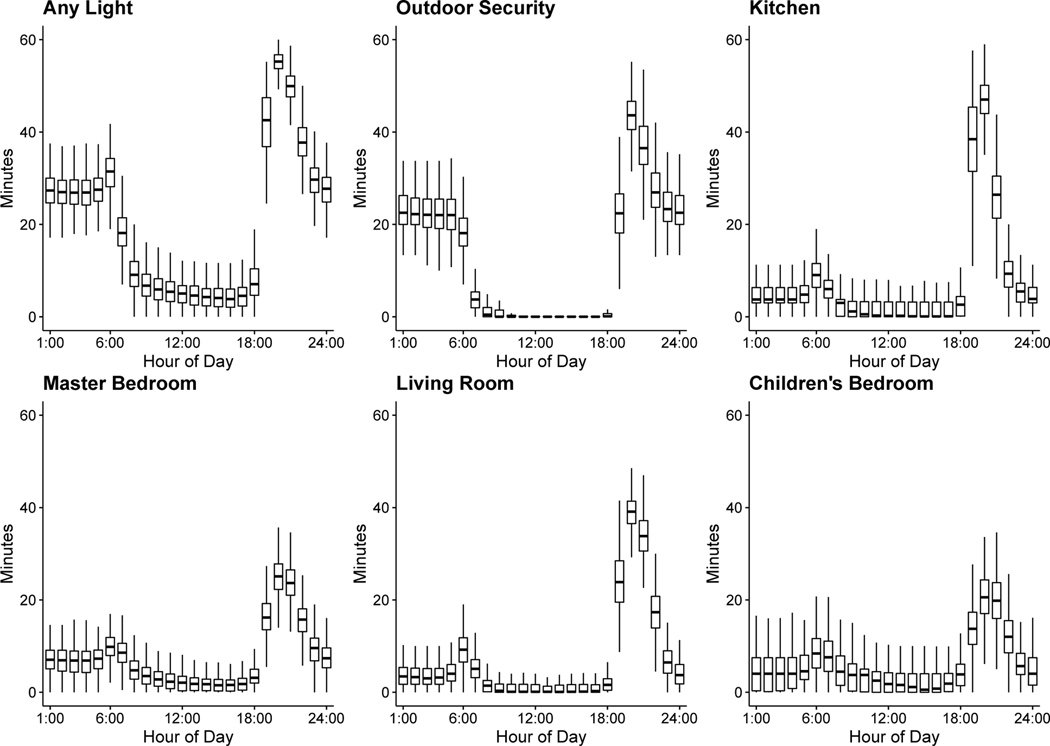

The location of light bulb placement chosen by participants is shown in Table 2. In the intervention group, based on sensor data, solar lighting was used for 8.2 (5.3) hours per day; 1.4 (2.5) hours was used during the day and 6.8 (4.2) hours at night, with daytime and nighttime determined based on sunrise and sunset times. Figure 2 depicts the usage pattern of each light bulb stratified by light location and time of day. The most heavily utilized light location was the outdoor security light (5.3 (4.9) hours per day), followed by the kitchen (3.20 (3.87) hours per day), master bedroom (3.09 (3.85) hours per day), living room (2.81 (2.62) hours per day), and children’s bedroom (2.56 (3.45) hours per day). Trends in light use over the one-year study period are depicted in Supplemental Figure 1. Using mixed effects models, there was no decline in the number of hours of lighting use per day over the entire study period overall (beta = 0.0 [0.0 – 0.0], p = 0.310) indicating sustained use over time. There were no statistically significant differences in the overall number of hours of light used per day between participants who already possessed clean lighting technology (solar panels, electrical grid access) and those who did not (kerosene and candles) at the time of randomization (p = 0.638).

Table 2.

Frequency and location of solar bulb placement selected by intervention arm households. Each of the 40 intervention households was provided with four solar bulbs. This table summarizes a total of 159 bulb placement locations; one participant’s home was small and there was no location to place a fourth bulb.

| Bulb location | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Living room | 36 (22.6%) |

| Master bedroom | 35 (22.0%) |

| Outdoor security light | 32 (20.1%) |

| Kitchen | 20 (12.6%) |

| Child’s bedroom | 17 (10.7%) |

| Storage room | 8 (5.0%) |

| Dining room | 6 (3.8%) |

| Guest bedroom | 2 (1.3%) |

| Home office | 1 (0.6%) |

| Corridor | 1 (0.6%) |

| Chicken coop | 1 (0.6%) |

Figure 2. Time and location of use of intervention solar lighting system.

Boxplot of the number of minutes (out of a maximum 60 minutes for each hour of day), stratified by time of day and light bulb location. Outliers are not shown to enhance the interpretability of the plot. Plots are sorted by location of heaviest use, being highest for the outdoor security light followed by the kitchen, master bedroom, living room, and children’s bedroom. Light was used most frequently at night, between 7PM and 8AM.

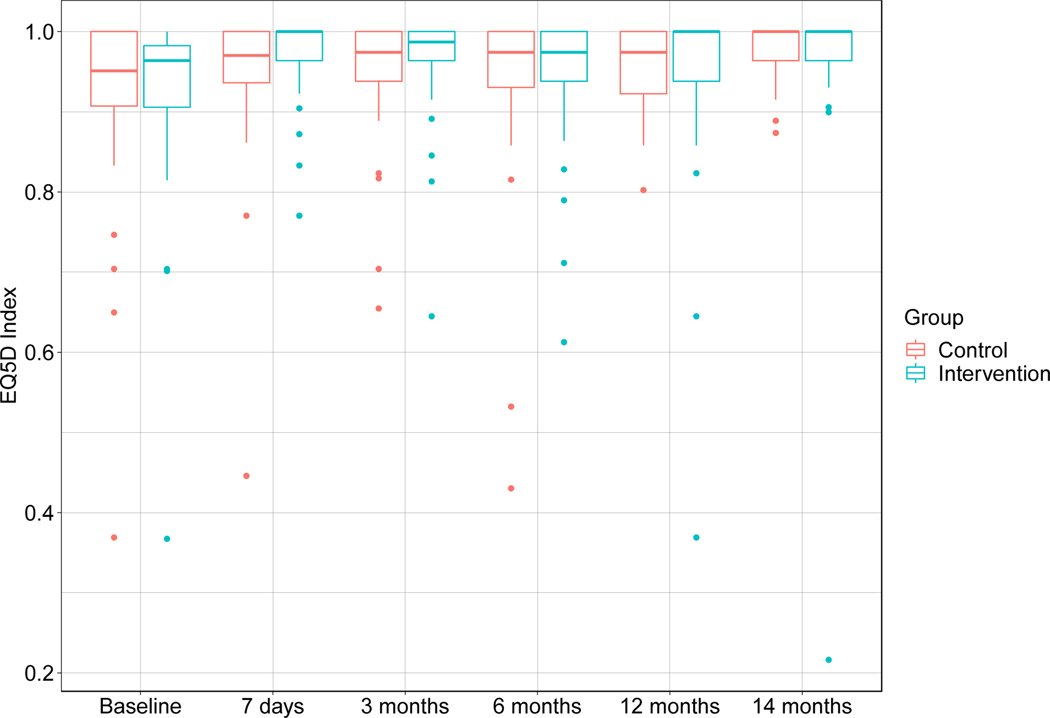

Health-related quality of life

Results of the EQ5D-5L survey administered longitudinally to both the intervention and control groups are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. The EQ5D-5L responses were converted to the EQ5D index using valuation weights derived from Ethiopia[33] as valuation weights do not exist for Uganda. Boxplots of raw data stratified by group assignment and follow-up period are depicted in Figure 3. In mixed effects models, the intervention solar lighting system increased the EQ5D index by 0.025 [95% CI 0.002 – 0.048], p = 0.038. Higher values represent better health-related quality of life.

Figure 3.

EQ5D index over time, stratified by intervention group. Y-axis is the EQ5D-index, where an index of 1 represents full health and an index of 0 represents a health state as bad as death. At baseline no group had received a solar lighting system. At 7 days, the intervention group had received a study solar system. At 14 months the control group had also received a solar lighting system. In a mixed effects model, the solar lighting intervention led to a 0.025 [95% CI 0.002 – 0.048, p = 0.038] increase in the EQ5D index value. C = control group. I = intervention group.

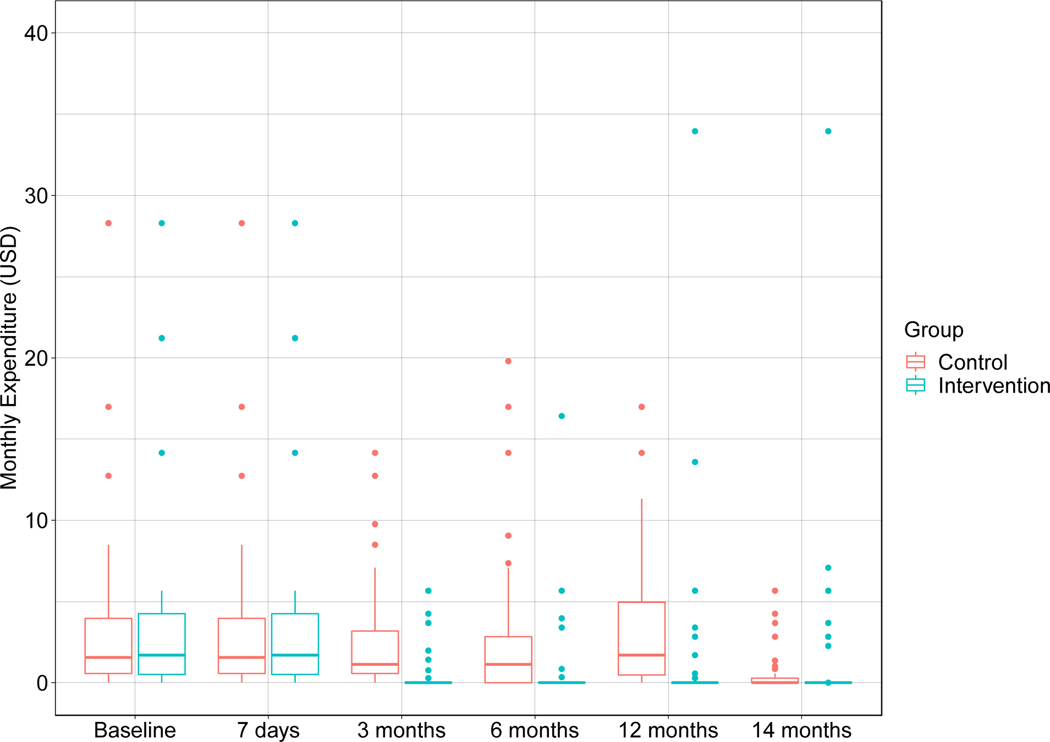

Costs

Raw monthly household expenditures on lighting are depicted in Figure 4. In mixed effects models, the solar lighting intervention led a change in household lighting expenditures by −1.28 [−2.52, −0.85] US dollars per month. Cost savings were higher in participants using kerosene-based lighting, with a change in household lighting expenditures by −2.77 [−3.87, −1.67] US dollars per month.

Figure 4.

Monthly lighting expenditures over time, stratified by intervention group. Y-axis is the monthly total expenditure on lighting in US dollars. At baseline no group had received a solar lighting system. At 7 days, the intervention group had received a study solar system. At 14 months the control group had also received a solar lighting system. In mixed effects models, the solar lighting intervention led a change in household lighting expenditures by −1.28 [−2.52, −0.85] US dollars per month. Cost savings were higher in participants using kerosene-based lighting, with a change in household lighting expenditures by −2.77 [−3.87, −1.67] US dollars per month.

Cost-effectiveness

At baseline, kerosene-using households spent $4.80 USD per month on lighting, while solar-using households spent $0.02 USD per month. From the individual perspective, assuming the government installed a household’s solar lighting system, the change from kerosene to solar lighting is a dominant strategy (that is, less costly with more health benefit).

In keeping with other studies of economic assessments of health interventions, we calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for the solar lighting intervention. In this analysis, the ICER represents the ratio of the marginal cost of an intervention to its marginal benefit— where “benefit” in our case, means QALYs gained. Based on willingness to pay thresholds recommended by the World Health Organization[34], an intervention is deemed cost-effective if the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is less than three times the gross domestic product (GDP)[35] per capita in Uganda (USD $2,451.12 in 2020, the latest year for which data are available [36]. It is deemed very cost-effective if the ICER was less than one times the GDP per capita (USD $817.04). The societal incremental cost-effectiveness (ICER) ratio for a change from kerosene to solar lighting was $2025.72 per quality adjusted life year (QALY) gained, making it a cost-effective intervention.

There are an estimated 4,489,500 households in Uganda currently using kerosene as their primary lighting source[37]. To upgrade all of these households to solar lighting systems would cost approximately USD 710 million, or 2% of the country’s one-year GDP.

We also estimated the break-even date if households paid for the transition from kerosene to solar lighting. To calculate the break-even date, the full cost of outfitting a household with a solar lighting system, USD $158.20, was assigned to Day 1, to which average daily solar lighting costs of USD $0.00055 accrued. We compared these cumulative costs with those faced by a household spending USD $0.157 per day, the average cost of kerosene lighting. Households converting to solar lighting would recoup their investment after 2.76 years, on day 1011 (Supplemental Figure 2).

Qualitative interviews

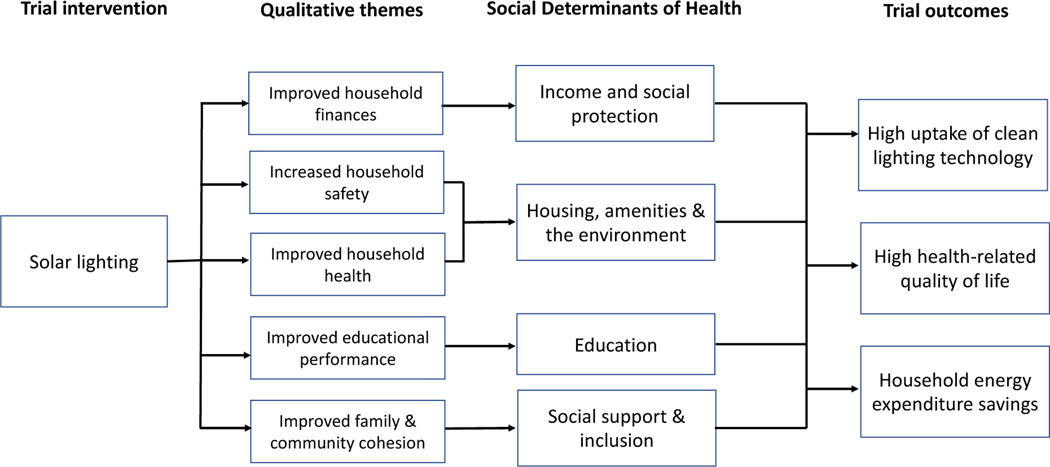

Qualitative interviews revealed that the solar lighting intervention was a transformative household energy technology, with a broad array of benefits attributed by participants to the solar lighting system. We identified five themes in the dataset: 1) improved household finances; 2) improved educational performance; 3) increased household safety; 4) improved family and community cohesion; and 5) improved household health. Themes from our qualitative data closely parallel well-described domains in the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework. SDOH are the social, physical and economic conditions into which people are born and live that impact their health and are responsible for health inequities[28]. We will consider each theme below, with supportive examples.

One of the most frequently described benefits of the solar lighting intervention was improved household finances (69% of participants). Participants reported decreased expenditures for household energy, increased time for income-generating activities, and the ability to divert funds to pay for other household expenditures. For example, participants used savings towards competing expenses such as household goods or for children’s school tuition and books.

This solar has helped a lot on minimizing home expenditures. We used to buy kerosene a lot but these days, instead of buying kerosene, we can use that money to do other things…items like washing soap, or saving money for school fees so the children are not sent home. [Nyakabare village, 37 years-old]

The money I used to spend on paraffin [kerosene]…before my children used to go to school without books. When I got the study solar, the money that would go on paraffin was shifted to buying children’s books. [Bushenyi village, 44 years-old]

The solar lighting system also contributed to improved finances by extending the workday, whether it was enabling the delay of household chores until the evening or allowing income-generating activities to be performed at night.

As I’ve told you, what I use that solar for ... if I am still outside, [now] I can see for stone quarrying. Yes, I work. I hit those stones and at times I stop at 11PM. [Nyamikanja village, 40 years-old]

Second, 81% of participants noted that solar lighting systems improved educational performance among their children. Prior to receiving solar lighting, participants describe rationing lighting fuel which prevented their children from completing homework.

There is a huge change [after receiving solar lighting] because before the children say, ‘[teachers] told us to read our books’. Then you would tell them, ‘No please, we don’t have enough kerosene.’ [Bukuna village, 41 years-old]

With the receipt of the solar lighting system, light no longer needed to be rationed and the ability for children to do homework after sunset translated into tangible academic improvements among participants’ children, and less worry among parents.

They [my children] were performing very badly [in school], they would be the last ones in class. I was very worried and I was about to get [high] blood pressure. I was worried about getting school fees and the performance of my kids at school was also discouraging. It all looked like money is being wasted. But now, I am very okay… I see that when they [my children] come back they spare some time to read books and they are performing very well these days. The school reports are good. [Bukuna village, 41 years-old]

Third, lighting was intrinsically linked with improvements to the participants’ home and neighborhood. Specifically, 68% of participants reported an increased perceived sense of safety after installation of the solar lighting, stating that the solar lighting system was instrumental in preventing crimes at night.

That bulb outside, I don’t know how I should talk about it [laughing] because it has done for me many good things. Even when I am in the house (you know my husband left me, he is no longer with us here) I am secure knowing that whatever is coming to my house, I will be seeing it since that security light is on. Anything of whatever size, or a thief. With my outdoor light on, I will be seeing him. I look through my window and see what is outside. That outdoor bulb is like my soldier. [Bushenyi village, 44 years-old]

In addition, anxiety about open-flame lighting sources as a fire hazard were alleviated with solar lighting systems.

Imagine you have left the children in the house with something that produces fire for light. You have to be worried [about starting a fire in the home]. I am sure even if I died today, I would die happy knowing that my children would never sleep in darkness. Light is secured for them because you gave them their solar. [Bushenyi village, 32 years-old]

Fourth, the solar intervention was reported by 54% of participants to improve family and community cohesion. Solar lighting was described as reducing economic stressors associated with purchasing lighting fuel, previously a common source of conflict. After receiving solar lighting systems, participants report improved relationships with their spouses.

Whenever we would lack kerosene, we would quarrel almost every day. I would be like, ‘now that we don’t have kerosene, how we will eat meals, lay kids to bed, or how will kids read their books?’. Or, at times I had to change kids’ nappies [diapers] in the dark, so conflicts would never end in my house. It was really a hard experience…. But now that I have solar, life is better and conflicts are reduced. My family now has peace. [Bukuna village, 32 years-old]

Lighting also allowed families to spend more time together as the duration of waking hours could be extended.

We used to sleep very early because of the need to save kerosene usage. However, after getting the solar, our [family] relationship has improved because after eating dinner, we now get time to sit and chat together … the solar has given us enough time to talk at night. So, it has helped us to understand each other very well. [Bukuna village, 30 years-old]

The solar intervention also was reported to bring prestige to participants within their communities, as neighboring households could share the benefits of the lighting systems. Solar lighting systems were perceived as status symbols, which served to decrease social isolation and strengthen relationships between neighbors.

After getting this solar ... neighbors [who] have got no solar now send their children to come and study at my house. They are also benefiting from this study solar. And by this, their parents are giving me more respect, which makes me feel important to the community. [Bushenyi village, 32 years-old]

Imagine having two [solar] systems when other people cannot even afford one, so that will make me big in the village. [Bukuna village, 45 years-old]

Finally, with introduction of the solar lighting systems, 40% of participants noted health improvements within their households. Participants were aware of the health dangers of smoke generated from fuel-based lighting and described how soot would gather in their children’s noses or in participant’s expectorated sputum.

Solar has no bad effect, it has only good things …. you do not get sick all the time. You do not spend a lot of money on the sicknesses of the children and the old people that live in our household. [Nyamikanja village, 33 years-old]

Participants were specifically asked about potential negative aspects of solar lighting. Concerns centered around the up-front cost of purchasing a solar system, and potential theft.

Buying solar,…do I have the money, no I don’t have the money. If it was like that everyone would be having solar… A person who does not have money cannot light solar. [Nyakabare village, 39 years-old]

The battery is my only worry. Because they [thieves or neighbors] know if they take the battery, there you just have to sell the solar because you can’t use it without a battery. [Nyamikanja village, 37 years-old]

Integration of quantitative and qualitative data reveal the broad impacts of solar lighting systems on participant’s lived experiences (Table 3). The number of hours of lighting use in the intervention group increased from 5.2 hours of self-reported use at baseline as compared to 8.2 hours of the study solar lighting system with participants reporting in qualitative interviews the ability to discontinue the practice of rationing light for cost reasons after the study intervention. The increase in wellbeing as quantitatively assessed by the EQ5D index after introduction of the study solar lighting system may be explained by participant interviews describing wide-ranging benefits to household economy, education, safety, family/community relationships, and health. Choice of lighting locations in the trial correlates with several of the benefits described in qualitative interviews. Participants’ increased sense of security correlated with high utilization of the outdoor security bulb. Improved educational opportunities for children was a frequently mentioned theme, reflecting frequent placement of a solar lightbulb in the living room or children’s bedrooms. Monthly lighting expenditures decreased after the solar lighting intervention, allowing participants to fund other household necessities.

Table 3.

Integration of quantitative trial results and qualitative themes

| Trial results | Qualitative theme | Qualitative example excerpt | % Participants reporting theme | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase in health-related quality of life | High uptake of clean lighting intervention | ↓ Fuel costs | Improved household finances | “This solar has helped a lot on minimizing home expenditures. We used to buy kerosene a lot but these days, instead of buying kerosene, we can use that money to do other things…items like washing soap, or saving money for school fees so the children are not sent home.” | 69% |

| Household placement of solar bulb | Improved educational performance | “They [my children] were performing very badly [in school], they would be the last ones in class. I was very worried and I was about to get [high] blood pressure. I was worried about getting school fees and the performance of my kids at school was also discouraging. It all looked like money is being wasted. But now, I am very okay… I see that when they [my children] come back they spare some time to read books and they are performing very well these days. The school reports are good.” | 81% | ||

| Increased household safety | “[The solar lighting] helps me outside for security reasons. If it is on, even the thief can’t hang around my house. They know that someone may see them and know who they are. Because of light, the whole place will clear and you can see everything. Since there is no darkness, the thieves fear to come around, and in that way I benefit from the solar light outdoors” | 68% | |||

| Improved family and community cohesion | “Whenever we would lack paraffin, we would quarrel almost every day. I would be like, ‘now that we don’t have paraffin, how we will eat meals, lay kids to bed, or how will kids read their books?’. Or, at times I had to change kid’s nappies [diapers] in the dark, so conflicts would never end in my house. It was really a hard experience. But now that I have solar, life is better and conflicts reduced. My family now has peace.” | 54% | |||

| Improved household health | “Solar has no bad effect, it has only good things …. you do not get sick all the time. You do not spend a lot of money on the sicknesses of the children and the old people that live in our household.” | 40% | |||

Solar lighting “helps” in concurrent and intersecting ways. This quote illustrates how solar lighting affected many aspects of a participant’s lived experience, including household economy, security, and community cohesion:

I would sometimes lack money to buy kerosene, then I would go to the nearby shop and beg for a debt [store credit]. The shopkeeper would pretend as if he has not heard my request. Then I would kneel down and beg him in front of people, ‘please give me kerosene. My kids are going to sleep in the dark’. It was too much shame and humiliation seeing an old woman kneeling down in the mud before a young man begging for kerosene of 1000 shillings ($0.30 USD). Ever since I got this solar, I have never asked for salt or a matchbox from the neighborhood. This solar has helped me a lot. [Bukuna village, 50 years-old]

DISCUSSION

In this randomized wait-list controlled trial of indoor solar lighting systems in rural Uganda, we found that use of the solar lighting intervention was high. The intervention was cost-effective when benchmarked against the willingness to pay threshold recommended by the WHO, which is three times the per capita GDP for Uganda. Our qualitative data demonstrate the transformative nature of solar lighting on participants’ daily lives, with positive impacts on multiple dimensions of lived experiences that fit within a SDOH framework. These multi-dimensional positive impacts likely explain the high and sustained uptake of clean lighting technology as well as the observation that participants who had already adopted clean lighting sources (electrical grid, solar) at study enrollment used the intervention solar lighting system just as much as participants who were using fuel-based lighting at study enrollment.

In Figure 4, we illustrate a model for how the study intervention solar lighting systems might improve SDOH. Our findings resonate with a recent systematic review of household solar systems in low and middle income countries, which found that these systems were primarily used for light, and that the impact of these systems on households mirror those found in our study with positive impacts on health, education of children, income generation, and cost savings[22]. Energy poverty has been described as a source of health inequalities[38]. Our qualitative interviews suggest that the impact of energy poverty on health may well be mediated by the relationship between energy poverty and the SDOH. Energy poverty might impact not just the immediate built environment but other important factors such as education and household finances[39]. Other global health interventions could similarly be assessed via a SDOH lens. For example, deworming programs have been linked to improved school attendance in Kenya and thus facilitate education as a SDOH[40].

A truly “patient-centered” approach to household energy interventions suggests that we should consider judging the success of an intervention based on the priorities of the end user rather than those set by study investigators or sponsors[41]. In prior studies[17] and based on our qualitative interviews, poverty is the primary reason why participants choose fuel-based lighting. Consequently, clean lighting interventions may break vicious cycles of health inequity through improving SDOH. Our findings suggest that a logical next avenue of research is to develop and validate in different contexts a survey for quantitative measures of SDOH to evaluate the efficacy of interventions, since these aspects are highly valued by the end user, likely variably influenced by different household energy interventions, and ultimately are a fundamental determinant of health disparities.

A key challenge in prior HAP interventions in global health has been uptake as well as sustained use of introduced products or technologies[42]. Clean lighting technology in the form of solar may provide direct financial benefits in several ways. First, clean lighting may increase the time the user spends on income generating activities. Second, fuel-based lighting burns inefficiently and thus is ultimately more costly than solar lighting for each lumen of light generated[43]. While the initial cost of solar systems is a concern for our study participants, our analyses show that households who transition from kerosene to solar lighting will reach a break-even point after 2.76 years. Our findings are similar to another study of home solar systems in Uganda where participants purchased solar lighting systems using a down payment followed by a monthly payment plan. Households saved on average $1.4 US dollars per week and reached a break-even point on their purchase after 3.14 years[21]. Thus, initiatives to promote clean lighting that include up-front cost subsidies, or financial services such as community savings schemes or pay-as-you-go solar lighting services may prove to be viable approaches for long term adoption of clean lighting technologies.

Our study has several strengths. To our knowledge, it is the first mixed methods study based on a randomized controlled trial of a clean lighting intervention. We monitored use of the solar lighting intervention with sensors. For qualitative studies, our sample size is considered large as individual interviews were conducted with all 80 trial participants. Although mixed methods studies have been conducted in the context of randomized controlled trials of improved cookstoves, clean cooking and clean lighting technology provide fundamentally different benefits. Thus, qualitative results from clean cooking studies cannot be easily extrapolated to clean lighting studies, making our findings novel.

Our study has some weaknesses. It is focused on one parish in southwest Uganda and lighting preferences may differ in other contexts, although kerosene-based lighting is widespread in resource limited settings where there is limited or unstable access to electricity[14]. For example, based on the 2014 Uganda National census, 61.5% of the population (70.3% in rural areas, 34.1% in urban areas) use kerosene lamps for lighting[37]. While the solar lighting intervention led to a statistically significant increase in the EQ5D index, it is not clear if this is a clinically significant improvement. Minimum clinically important differences in EQ5D index score vary by country, disease studied, and the methodology[44, 45] thus there is no universally agreed upon threshold value. However, simulation studies have suggested that the minimally important differences in EQ5D index ranges between 0.037 and 0.069 [44]; the observed improvement in the EQ5D index due to the study intervention was 0.025. The EQ5D-5L, as a generic health-related quality of life survey, suffers from a well-known “ceiling effect” where many health conditions don’t actually register as a decreased quality of life[46]. This was apparent in our study where at baseline 30.2% of participants already reported perfect health according to their EQ5D-5L responses. It is possible that the EQ5D-5L instrument is not sensitive to the things the intervention changed for the study participants. In our qualitative interviews, only 40% of participants mentioned improved household health as a benefit of the study solar system, whereas 81% noted improved educational performance of their children, 69% noted improved household finances, 68% noted increased household safety, and 54% noted improved family and community cohesion. These latter benefits fall within a SDOH framework thus downstream impacts of the solar lighting intervention on health may take time to emerge. Qualitative studies provide novel hypotheses that can subsequently be tested with quantitative methods, and our results suggest that an instrument that can quantify the SDOH may be helpful for measuring the full impact of future household energy interventions. Finally, it is possible our responses may be impacted by social desirability bias such that participants may have felt unable to express dissatisfaction after being given a solar lighting system, although interviews were conducted both before and after the solar systems were installed.

In conclusion, introduction of home solar lighting systems has high sustained use, is cost-effective, and impacts multiple SDOH. Our findings suggest that household solar lighting interventions may be a cost-effective approach to improve health-related quality of life by addressing SDOH.

Data availability

Anonymized data, study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and informed consent forms for this study will be made available to others upon reasonable request to the senior author.

Supplementary Material

Figure 5.

Schematic showing qualitative results as they correspond to selected domains of Social Determinants of Health

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health grants K23 ES023700 (PSL) and R01MH113494 (ACT), Harvard School of Public Health National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and Center for Environmental Health (P30ES000002) Pilot Project Grant (PSL), American Thoracic Society Unrestricted Grant (PSL), the Massachusetts General Hospital Department of Medicine Transformative Scholars Award (PSL), and Friends of a Healthy Uganda (ACT). We thank all participants for taking part in this study and sharing their experiences with us. We wish to thank Hellen Nahabwe, Catherine Nakasita, and John Bosco Tumuhimbise for their contribution to the conduct of the qualitative interviews.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing financial interests: No competing financial interests to disclose

Ethical statement

Written informed consent was obtained from study participants. This study was approved by the Mbarara University of Science and Technology (Protocol 02/11–16) and the Partners Human Research Committee (Protocol 2017P000306), the Ugandan National Council of Science and Technology (Protocol PS 42) and the Ugandan President’s office. The trial was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03351504) prior to commencement of the study.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arto I, et al. , The energy requirements of a developed world. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2016: p. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators, Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet, 2020. 396(10258): p. 1223–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith KR, et al. , Effect of reduction in household air pollution on childhood pneumonia in Guatemala (RESPIRE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2011. 378(9804): p. 1717–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mortimer K, et al. , A cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstove intervention to prevent pneumonia in children under 5 years old in rural Malawi (the Cooking and Pneumonia Study): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2017. 389(10065): p. 167–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quansah R, et al. , Effectiveness of interventions to reduce household air pollution and/or improve health in homes using solid fuel in low-and-middle income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Int, 2017. 103: p. 73–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thakur M, et al. , Impact of improved cookstoves on women’s and child health in low and middle income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax, 2018. 73(11): p. 1026–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jary H, et al. , Household Air Pollution and Acute Lower Respiratory Infections in Adults: A Systematic Review. PLoS One, 2016. 11(12): p. e0167656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clasen T, et al. , Design and Rationale of the HAPIN Study: A Multicountry Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Effect of Liquefied Petroleum Gas Stove and Continuous Fuel Distribution. Environ Health Perspect, 2020. 128(4): p. 47008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenthal J, et al. , Systems Science Approaches for Global Environmental Health Research: Enhancing Intervention Design and Implementation for Household Air Pollution (HAP) and Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) Programs. Environ Health Perspect, 2020. 128(10): p. 105001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seguin R, Flax VL, and Jagger P, Barriers and facilitators to adoption and use of fuel pellets and improved cookstoves in urban Rwanda. PLoS One, 2018. 13(10): p. e0203775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hollada J, et al. , Perceptions of Improved Biomass and Liquefied Petroleum Gas Stoves in Puno, Peru: Implications for Promoting Sustained and Exclusive Adoption of Clean Cooking Technologies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2017. 14(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simkovich SM, et al. , A Systematic Review to Evaluate the Association between Clean Cooking Technologies and Time Use in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2019. 16(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly CA, et al. , From kitchen to classroom: Assessing the impact of cleaner burning biomass-fuelled cookstoves on primary school attendance in Karonga district, northern Malawi. PLoS One, 2018. 13(4): p. e0193376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam NL, et al. , Kerosene: a review of household uses and their hazards in low- and middle-income countries. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev, 2012. 15(6): p. 396–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam NL, et al. , Household light makes global heat: high black carbon emissions from kerosene wick lamps. Environ Sci Technol, 2012. 46(24): p. 13531–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Apple J, et al. , Characterization of particulate matter size distributions and indoor concentrations from kerosene and diesel lamps. Indoor Air, 2010. 20(5): p. 399–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muyanja D, et al. , Kerosene lighting contributes to household air pollution in rural Uganda. Indoor Air, 2017. 27(5): p. 1022–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam NL, et al. , Exposure reductions associated with introduction of solar lamps to kerosene lamp-using households in Busia County, Kenya. Indoor Air, 2018. 28(2): p. 218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barron M. and Torero M, Household electrification and indoor air pollution. . Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 2017. 86: p. 81–92. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mahajana A, Harish S, and Urpelainen J, The behavioral impact of basic energy access: A randomized controlled trial with solar lanterns in rural India. Energy for Sustainable Development, 2020. 57: p. 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen AZ, et al. , Welfare impacts of an entry-level solar home system in Uganda. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 2017. 9(2): p. 277–294. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemaire X, Solar home systems and solar lanterns in rural areas of the Global South: What impact? WIREs Energy Environ., 2018. 7: p. e301. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner N, et al. , The impact of off-grid solar home systems in Kenya on energy consumption and expenditures. . Energy Economics, 2021. 99: p. 105314. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rom A, Gunther I, and Harrison K, Economic Impact of Solar Lighting: A Randomised Field Experiment in Rural Kenya. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rodriguez-Alvarez A, Orea L, and Jamasb T, Fuel poverty and well-being: a consumer theory and stochastic frontier approach. Energy Policy, 2019. 131: p. 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmad S, Mathai MV, and Parayil G, Household electricity access, availability and human well-being: evidence from India. Energy Policy, 2014. 69: p. 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devlin N, et al. , Methods for Analysing and Reporting EQ-5D Data [Internet]. 2020: Springer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Solar O. and IA, A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). World Health Organization, 2010: p. 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herdman M, et al. , Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res, 2011. 20(10): p. 1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braun V. and Clarke V, Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol, 2006. 3: p. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V, et al. , Thematic Analysis, in Handbook of research methods in health social sciences, LP, Editor. 2019, Springer Nature: Singapore. p. 844–58. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundler AJ, et al. , Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nurs Open, 2019. 6(3): p. 733–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Welie AG, et al. , Valuing Health State: An EQ-5D-5L Value Set for Ethiopians. Value Health Reg Issues, 2020. 22: p. 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization, Making Choices in Health: WHO Guide to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis, Edejer T. Tan-Torres, et al. , Editors. 2003, World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edejer TT-T, Edejer TT-T, and O. World Health, Making choices in health : WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. 2003, Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$) - Uganda. 2020. [cited 2021 September 25, 2021]; Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=UG.

- 37.Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS), The National Population and Housing Census 2014 – Main Report, Kampala, Uganda. 2016, Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS): Kampala, Uganda. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomson H, Snell C, and Bouzarovski S, Health, Well-Being and Energy Poverty in Europe: A Comparative Study of 32 European Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2017. 14(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Banerjee R, Mishra V, and Maruta AA, Energy poverty, health and education outcomes: Evidence from the developing world. Energy Economics, 2021. 101: p. 105447. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miguel E. and Kremer M, Worms: Identifying Impacts on Education and Health in the Presence of Treatment Externalities. Econometrica, 2004. 72(1): p. 159–217. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sesan T, et al. , Toilet training: what can the cookstove sector learn from improved sanitation promotion? Int J Environ Health Res, 2018. 28(6): p. 667–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hanna R, Duflo E, and Greenstone M, Up in Smoke: The Influence of Household Behavior on the Long-Run Impact of Improved Cooking Stoves. . American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2016. 8(1): p. 80–114. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alstone P, Gershenson D, and Kammen DM, Decentralized energy systems for clean electricity access. Nature climate change, 2015. 5(4): p. 305–314. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McClure NS, et al. , Instrument-Defined Estimates of the Minimally Important Difference for EQ-5D-5L Index Scores. Value Health, 2017. 20(4): p. 644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouelhi Y, et al. , How is the minimal clinically important difference established in health-related quality of life instruments? Review of anchors and methods. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2020. 18(1): p. 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janssen MF, et al. , Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: a multi-country study. Qual Life Res, 2013. 22(7): p. 1717–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data, study protocol, statistical analysis plan, and informed consent forms for this study will be made available to others upon reasonable request to the senior author.