Abstract

Vibrational spectroscopy is a useful technique for probing chemical environments. The development of models that can reproduce the spectra of nitriles and azides is valuable because these probes are uniquely suited for investigating complex systems. Empirical vibrational spectroscopic maps are commonly employed to obtain the instantaneous vibrational frequencies during molecular dynamics simulations but often fail to adequately describe the behavior of these probes, especially in its transferability to a diverse range of environments. In this paper, we demonstrate several reasons for the difficulty in constructing a general-purpose vibrational map for methyl thiocyanate (MeSCN), a model for cyanylated biological probes. In particular, we found that electrostatics alone are not a sufficient metric to categorize the environments of different solvents, and the dominant features in intermolecular interactions in the energy landscape vary from solvent to solvent. Consequently, common vibrational mapping schemes do not cover all essential interaction terms adequately, especially in the treatment of van der Waals interactions. Quantum vibrational perturbation (QVP) theory, along with a combined quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical potential for solute–solvent interactions, is an alternative and efficient modeling technique, which is compared in this paper, to yield spectroscopic results in good agreement with experimental FTIR. QVP has been used to analyze the computational data, revealing the shortcomings of the vibrational maps for MeSCN in different solvents. The results indicate that insights from QVP analysis can be used to enhance the transferability of vibrational maps in future studies.

I. INTRODUCTION

Vibrational spectroscopy is a powerful tool to investigate the structure and dynamics of complex systems with atomistic details.1–14 To gain specificity, vibrational probes or isotope labels are often chosen to produce localized modes and shift frequencies away from crowded regions of the spectrum.5,15–19 In particular, nitriles and azides have been widely used in biological systems such as proteins. These probes are useful because their absorption peaks occur in the so-called quiet zone of the infrared spectrum (1800–2500 cm−1), a region where biomolecules are generally inactive and the probes are measured with little interference.18–21 These moieties can also be covalently linked to specific residues in a protein, often without significant perturbations to the protein structure.18,21,22 Finally, these probes are highly sensitive to the local environment, making it convenient to investigate the conformational dynamics.18,20,21 To extract molecular information from these probes, it is necessary to connect spectral changes to conformational ensembles and local environments. For example, previous studies have used carbonyl groups as reporters of hydrogen bonding populations in lipid membranes and micelles,23 amides, and polypeptides to probe protein structures, backbone flexibility, and solvent exposure,24–27 as well as the R–OH groups to understand the degree of hydrophobicity on hydrogenated nanodiamonds.28

To aid the interpretation of experimental observations, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are useful tools to provide insights into the specific intermolecular interactions between a vibrational probe molecule and its surroundings. These studies require a rapid evaluation of the instantaneous vibrational frequencies of the probe functional group on the fly of molecular dynamics simulations, and several alternatives are available, including instantaneous harmonic frequency analysis,29,30 vibrational spectroscopic maps,31 perturbation theory,32 and the solution of the vibrational Schrödinger equation.33 Among these approaches, the vibrational spectroscopic map is perhaps the most popular for its computational efficiency, although it is known that it sometimes suffers from a lack of transferability and the challenges for specific parameterization and validation. The general implementation of a vibrational map relies on the assumption that the vibrational frequency, ω, of a probe molecule in a condensed-phase environment is the sum of the gas phase frequency or the ensemble average frequency in a condensed-phase system, ω0, and the change, δω, in response to the electric field and potential φ of the chemical environment,

| (1) |

For some oscillators, such as C=O in esters and amides, this electrostatic perturbative model is highly effective and the vibrational maps created in one solvent can be transferred to a variety of different environments.34–36 For other probes, such as nitriles and azides, a purely electrostatic map shows greater dependency on the specific solvent used and lacks a broader applicability than probes featuring the carbonyl group.37 In particular, nitriles and azide frequencies are influenced by a range of interactions such as repulsion forces38–43 and hydrogen-bonding geometry,37,44 which are not all purely electrostatic in nature. Consequently, it is essential to develop computational models that are efficient, transferrable, and capable of capturing the dynamic changes in the potential energy surface resulting from solvent fluctuations to yield the instantaneous vibrational frequencies of probe molecules.

Combined quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical (QM/MM) potentials have been successfully employed to probe the underlying mechanisms of vibrational spectral shifts in many systems.32,45,46 In a combined QM/MM approach, the probe molecule is treated explicitly by an electronic structure theory to provide the most systematic representation of the potential energy surface, in which the effects of solvent dynamics are naturally incorporated.32,47,48 However, the direct use of ab initio molecular orbital and density functional theory (DFT) techniques to obtain on-the-fly vibrational frequencies is still limited because of the computational cost needed to determine the Hessian or to solve the vibrational Schrödinger equation repeatedly during the dynamics simulation.49,50 To circumvent this difficulty, we have used a quantum vibrational perturbation (QVP) theory,32,47,48,51 which only requires single-point energy calculations on an optimized set of grid points, discussed below. In this article, we compare and contrast the performance of results from vibrational spectroscopic map approaches and that of the QVP method, making use of the methyl thiocyanate (MeSCN) probe molecule in aqueous and organic solvents.

The shortcomings of electrostatic maps for nitriles will be discussed in this paper, expressed by using the MeSCN probe molecule in different solvents. It is shown that electrostatic maps can be fit to a variety of solvents individually, but the results indicate that it is difficult for the map fitted for one solvent to describe other solvents simultaneously. We examine some of the underlying similarities and differences in the electrostatic environments of different solvents. We found that the use of a quantum vibrational perturbation (QVP) theory and quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations provides a viable route to calculating the nitrile spectra in different solvents. Finally, the underlying differences that these methods capture are discussed. The findings of this work may be useful to creating vibrational maps that can capture fundamental interactions in addition to electrostatic terms.

II. METHODS

A. FTIR spectra

Samples of MeSCN in various solvents were prepared at 250 mM by adding 8.5 µl of MeSCN to 491.5 µl of solvent. Spectra were recorded at room temperature using a Bruker INVENIO spectrometer at a 0.5 cm−1 resolution with a 50 µm path length. The spectra were background corrected, and, when necessary, a Fourier filter was applied to remove any interference patterns in the frequency domain due to the presence of air bubbles in the sample. After cleanup, the spectra were normalized by the peak area.

B. Molecular dynamics simulations

Trajectories used for generating the vibrational maps and examination of local electrostatic features were carried out both using the empirical CHARMM36 general forcefield52–54 and a combined quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical (QM/MM) potential. For simulations employing combined QM/MM calculations, we employed a box of ∼45 × 45 × 45 Å3 with varying numbers of solvent molecules plus a single MeSCN solute. Here, we employed solvents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), tetrahydrofuran (THF), carbon tetrachloride (CCl4), diethyl ether (Et2O), methanol (MeOH), and water to represent a range of solvent polarity. In combined QM/MM simulations, the solute MeSCN was represented by the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE)55 density functional theory and the 6-31G(d) basis set. For solvents, the three point charge TIP3P model was used for water,56 and the Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations All Atoms (OPLS-AA) force field57 was used to describe the solvents. The Lennard-Jones parameters from the force field52 were further optimized for the “QM” atoms by considering bimolecular interactions (below). In all cases, the geometric mean for pair interaction sites was used.

In full MM simulations with the CHARMM36 force field, cubic boxes of different sizes, consisting of 1000 solvent molecules, were used. To consider a broad applicability, we modeled a total of 15 different solvents, matching the same solvents used in the experimental FTIR measurements. Thus, in addition to those listed above in combined QM/MM simulations, we included acetone, acetonitrile (ACN), benzyl alcohol, butanol (BuOH), hexanol (HexOH), dimethyl acetamide (DMA), dimethyl formamide (DMF), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and pyridine. For solvent molecules not included in the CHARMM36 force field, the Chemistry at Harvard Macromolecular Mechanics (CHARMM) general force field (CGenFF)52–54 was adopted.

In all simulations, long-range electrostatic interactions were determined by using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method,58,59 and van der Waals interactions were truncated using a cutoff distance of 12 Å, identical to that of the real space part of the Ewald sum. The LINear Constraint Solver (LINCS) algorithm60 was applied to constrain the bond lengths of solvent molecules. First, the initial simulation boxes were minimized using the steepest-descent energy minimization method or the adopted basis Newton–Raphson algorithm.61 After equilibration lasting for at least 1 ns, we carried out 500 ps production simulation with an integration time step of 1 fs under the isothermal–isobaric ensemble (NPT) at 303.15 K and 1 atm for each solution using the fully MM force field, and 1 ns of production in combined QM/MM simulations at 298.15 K. Coordinates were saved at an interval of 20 fs in the MM calculations and of 10 fs in the QM/MM trajectories, respectively, to generate the electrostatic potential maps and to perform the QVP analysis. The MM simulations were carried out using the GROMACS 2019 program62,63 and combined QM/MM calculations with the CHARMM package.61

C. Vibrational frequencies from electrostatic potential map

The vibrational spectroscopic maps follow the functional form presented by Choi et al.,44 in which virtual sites are placed around MeSCN in different solutions and the electrostatic potential is measured at each site for each saved step of the trajectory. There are seven groups of “sites” in this model, shown in Fig. 1. Two sites (sites 6 and 7) are circular distributions of eight points, which describe π interactions. These remaining sites describe the potential at each non-hydrogen atom, with site 5 used to describe σ interactions with nitrogen. The frequency shift for each step, δω, is given as the sum of products between the site potential, ϕj, and an empirical site coefficient, lj,

| (2) |

FIG. 1.

Schematic illustration of the multisite model to represent the electrostatic potential around methyl thiocyanate for the vibrational map. Groups 6 and 7 indicate a set of eight equally spaced points around nitrogen and the nitrile carbon, respectively.

In this case, rather than parameterizing the map directly to ab initio frequency shifts, the maps were fitted to the experiment by calculating the instantaneous frequency shifts and the corresponding absorptive response function, which is directly compared to the measured FTIR spectrum.34 The response function used is described below [Eq. (3)]. A modified least-squares fitting was used to compare computed spectra with measured spectra. Specifically, the penalty function included a harmonic potential on the position of the peak and a harmonic potential on the sum of the lj coefficients, which should sum to zero.44

A genetic algorithm was used to find sets of coefficients. The population size was between 1000 and 2000 with a maximum number of 300 generations. The genetic algorithm was run between 10 and 50 times for each system. A global search algorithm with the same penalty function was used to further minimize the output coefficients from each finished genetic algorithm run.

To calculate the charge distribution, MeSCN was aligned with the nitrile carbon at the origin, the C≡N bond along the Y-axis in the positive direction, and the methyl carbon on the XY-plane in the positive X-direction. Charges within ±1 nm in the XY-direction and ±0.6 nm in the Z-direction were treated as in-plane (no Z-component). A mesh was created with 0.01 nm spacing along the XY-plane and the charges were summed at each point with a gaussian filter being used to select only nearby charges. The gaussian filter was a symmetric 2D-gaussian with a sigma of 0.08 nm. These charges were averaged over every 400 fs of a 200 ps trajectory. The same calculation can be done for electrostatic potential, but it is very slow to average due to r ≅ 0 extrema. It also suffers more from non-charge-neutrality because the decay of electrostatic potential is much slower than a gaussian decay.

D. Quantum vibrational perturbation method

The instantaneous vibrational frequency of the C≡N stretching mode of the probe molecule MeSCN in solution was determined by using the quantum vibrational perturbation (QVP) theory developed by Li and co-workers.32,47,48,51 Because the one-dimensional vibrational Schrödinger equation was solved numerically, both nuclear quantum effects (NQE) and anharmonicity are included, and the numerical efficiency allows the vibrational frequency of the probe molecule to be determined on the fly during molecular dynamics simulations. The computational procedure in QVP includes two steps. First, we determine the reference state, a snapshot of the solute–solvent configuration in a dynamics trajectory, by using the potential optimized discrete variable representation (PO-DVR)64–66 approach. In the second step, the instantaneous vibrational frequency of the C≡N stretch mode is obtained as a perturbation to the reference frequency due to fluctuations of the solvent configurations and the change in the solute geometry in the dynamics trajectory. Computational efficiency is achieved as a result of the PO-DVR procedure because only single-point energy calculations at the quadrature points are needed. We found that a resolution within 0.1 cm−1 can be obtained at the fourth-order perturbation using 10 PO-DVR points along the C≡N stretching mode vector in this work.

We have examined a number of density functionals and found that the QVP@PBE/6-31G(d) combination yields an adequate description of the C≡N stretching frequency of MeSCN, with a small deviation of 7.7 cm−1 in comparison with the experimental value of 2171 cm−1 in the gas phase.67 This model was adopted in all instantaneous vibrational frequency calculations and in combined QM/MM molecular dynamics simulations. Again, in particular, the solute molecule, the chromophore MeSCN, was treated by density functional theory with the PBE functional and 6-31G(d) basis set, and the rest of the solvent systems were represented by the OPLS-AA force field.68,69 Since the solute molecule is small and the C≡N stretching is relatively local,70,71 only a single C≡N mode was considered without specific mode coupling with other degrees of freedom and there were no constraints or restrains applied to the solute molecule during the dynamics simulations.

Having obtained the time-dependent sequence of vibrational frequencies ω(t), we computed the vibrational IR line-shape, I(ω), within the Condon approximation,72–75

| (3) |

where is the average frequency of the 1 → 0 transition of the C≡N stretch mode and is the frequency fluctuation at time t. We computed the vibrational energy relaxation rate T1, in the term , following the work of Straub and co-workers76–79 by computing the autocorrelation function of the force along the constrained C≡N bond in the solvent environment. The calculated T1 in different solutions are 36.2 ps in water, 53.1 ps in MeOH, 206.5 ps in DMSO, 219.1 ps in THF, 221.9 ps in CCl4, and 225.4 ps in Et2O, in accord with the experimental data reported by van Wilderen et al.41

For comparison, we have also computed the linear absorption line shapes based on the Fourier transform of the autocorrelation function of the instantaneous dipole moment from combined QM/MM molecular dynamics simulations,80,81

| (4) |

Here, the effects of solvation due to electrostatic interactions and anharmonicity of the potential energy surface are included, but nuclear quantum effects are absent. That is, QVP treats nuclear vibrations quantum-mechanically by solving the vibrational Schrödinger equation numerically with the DVR approach, while the dipole autocorrelation function (DAF) uses classical trajectories.

E. Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to understand correlated contributions to the computed spectral shifts due to electrostatic interactions with the solvent. The software package from MATLAB R2021b was used. Principal component analysis is a change-of-basis operation that uses the means and eigenvectors of a dataset to transform the data such that it exists in a space where the axes are ordered in terms of maximum variance of the dataset. PCA was used with the distribution of charge around the MeSCN oscillator to determine which solvents have similar electrostatic environments and which solvents show different electrostatic environments. Furthermore, the observations with the highest “score” (greatest absolute value) in the first dimension are selected to determine the coordinates of the charge distribution that contribute the most to the variance of the data. The following equation relates the data with each series (column) centered on the mean, Xc, the transpose of the principal components, C′, and the scores, S, where represents the matrix product:

| (5) |

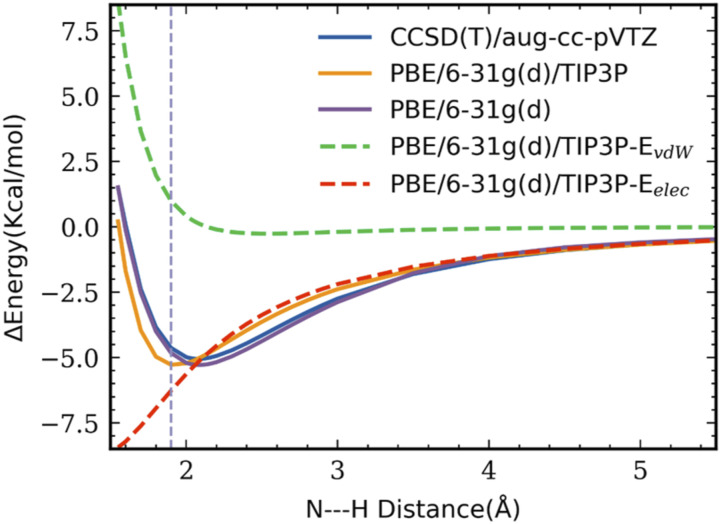

F. Bimolecular complex interactions and frequency shift

To validate the performance of the present combined QM/MM model for the MeSCN vibrational dynamics, linear and distorted hydrogen-bonding configurations44 of MeSCN–H2O and MeSCN–MeOH complexes are examined. In these calculations, the optimized monomer geometries of MeSCN and MeOH were held fixed in the complex at the corresponding level of theory, but the experimental geometry for water was used in the complex with water.82,83 Intermolecular geometries were optimized by the QM/MM model and the results were compared with those obtained from full coupled-cluster single double triple [CCSD(T)]/aug-cc-pVTZ//MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ calculations (Fig. 2). Overall, both interaction energies and hydrogen-bonding geometries from the combined QM/MM model and CCSD(T) results are in reasonable agreement.

FIG. 2.

Optimized geometries and interaction energies of MeSCN–H2O and MeSCN–MeOH complexes. CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ//MP2/aug-cc-pVTZ values are given along with the PBE/6-31G(d)/MM results in parentheses. (a) and (c) represent the linear type σ-hydrogen bonding interactions and (b) and (d) feature the π-type polarization. Distances are given in angstroms, angles in degrees, and energies in kcal/mol. (a) ΔE = −5.05(−5.29). (b) ΔE = −5.10(−5.49). (c) ΔE = −5.37(−5.64). (d) ΔE = −5.70(−5.75).

Several studies42,44 on the R–CN probe have shown that the two different hydrogen-bonding patterns in Fig. 2 can have significant and different influence on the vibrational frequency shifts,

| (6) |

where ω is the frequency in a molecular complex and ω0 is the C≡N vibrational frequency of the isolated MeSCN, having a value of 2163.3 cm−1 from QVP@PBE/6-31G(d) calculations. The vibrational frequencies are computed using the QVP method as described in Sec. II D. The MeSCN–H2O complex geometry is fully optimized at the PBE/6-31G(d) level. The π-type of hydrogen-bonding interactions tends to increase the C≡N bond length, whereas the σ-hydrogen bonding arrangement leads to a decrease in the C≡N bond distance. Consequently, the CN vibrational frequency is, respectively, red-shifted to 2155.1 cm−1 (Δω = −8.2 cm−1) and blue-shifted to 2170.6 cm−1 (Δω = 7.3 cm−1) in the π and σ-types of hydrogen bonding interactions. The trends in bond length and frequency shift are in accord with those reported by Cho and co-workers,44 demonstrating that the present combined QM/MM model can adequately describe intermolecular interactions between MeSCN and hydrogen bonding solvents in molecular dynamics simulations.

III. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A. Electrostatic maps

Vibrational electrostatic maps were optimized for MeSCN in eight selected solvents by fitting the peak positions and widths of the experimental spectra (see Fig. S1 of the supplementary material). The solvents selected were chosen to clearly represent patterns in the electrostatic environments, which are explained further below. In principle, the vibrational frequency shifts and spectral lineshape functions can be readily obtained based on the vibrational map model, providing insights into the electrostatic environments of the solute. We first computed the charge distribution around the solute molecule MeSCN in each system, which is plotted in the molecular plane in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

The mean distribution of charge around MeSCN in eight solvents. All solvents and contour lines use the same scale.

Several features of the local electrostatics can be identified in different solvents (Fig. 3). First, in order of the three atoms in the Me–S–C≡N functional group, a positive–negative–positive pattern was found in the charge distribution of the solvent, reflecting the strong electronegativity of nitrogen with a partial negative charge to accept hydrogen bonds (or positive electrostatic sites) and the lone-pair of electrons of sulfur. Since the CN carbon site carries a partial positive charge, it is surrounded by negative charge density, ranging from weakly negative in diethyl ether to strongly negative (deep blue) in DMSO and acetonitrile. Second, the positive charge density about the nitrogen site differs from both those of the CN carbon and sulfur atoms in that the external (solvent) positive-charge donation can take place both in directions along (σ-type) and perpendicular to (π-type) the CN bond axis. As will be seen below, the two orientations can have significant implications in hydrogen bonding effects on spectral shifts. We also notice variations in charge distribution patterns, which is localized in protic solvents including water and alcohols, diffusive in ether and THF, and distinctive lobes in DMSO and acetonitrile. The latter is particularly striking since there is no specific hydrogen-bonding donating group in these two solvent molecules; yet, a strong preference for positive charge centers (from methyl hydrogen atoms) still exists. Finally, of the four protic solvents shown in Fig. 3, the positive charge density increases in the order of hexanol < butanol < methanol < water, primarily reflecting steric effects that reduce the number of nearest neighbors by the nitrogen site as the size of the side chain increases.

Many vibrational maps have been constructed solely on the basis of the local electrostatic environments of probe molecules. If the local electrostatics were a sufficient metric to reproduce spectral lineshapes, one would predict that solvents with similar charge distributions have similar spectra. Therefore, strictly based on a qualitative assessment of the electrostatic environment shown in Fig. 3, one predicts that acetonitrile and DMSO could have similar center frequencies, and potentially similar lineshapes, ether and THF solvents would belong to the same category, and the alcohol series of solvents may differ spectrally depending on steric effects. While the plot of mean charge distribution is useful qualitatively, we turn to principal component analysis (Fig. 4) to assess the likelihood of solvent environments correlating with experimental spectra. Again, if the electrostatic environment determines the variance in spectral lineshape and frequency, solvents that are minimally variant in charge distribution (nearby in the PCA) would also exhibit a similar lineshape.

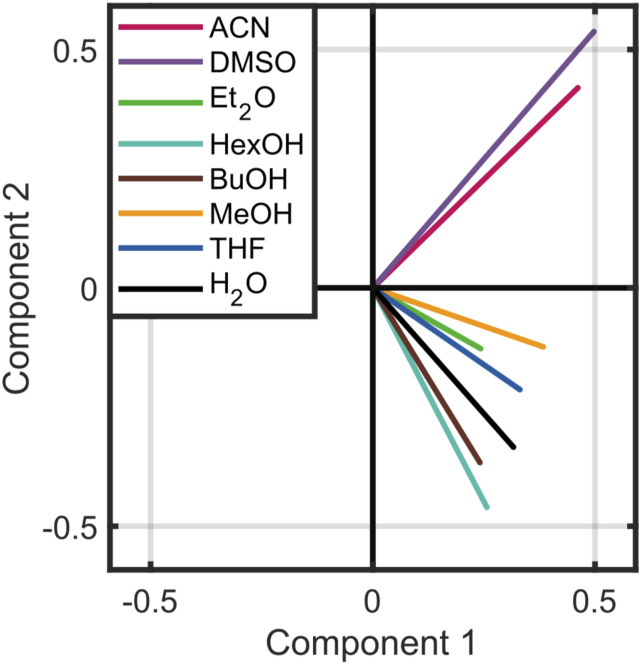

FIG. 4.

Electrostatic environments of the eight solvents in Fig. 2 projected along the first two principal components. Components 1 and 2 of the PCA correspond to 71.7% and 14.5% of the variance of the data, respectively. Component 3 (not plotted) corresponds to an additional 7.7% of the total variance. The scores of the coordinates in the principal components are plotted in Fig. S2 of the supplementary material.

All solvents that have been analyzed show a narrow distribution along the first component, but there is clustering when the first two components are considered in conjunction. Acetonitrile (ACN) and DMSO are similar in their projection to the first two PCA components, but distinct from the other solvents (Fig. 4). However, the FTIR spectra of DMSO and acetonitrile are quite different. In contrast, hexanol and butanol are clustered in the first two principal components, but they are relatively far from that of methanol. Yet, their FTIR spectra are nearly identical. Finally, ether and THF are, indeed, closely clustered in Fig. 4. Interestingly, ether and hexanol appeared to have similar charge densities based on Fig. 3, but they show different absorption spectra, and their first two principal components are very different. This illustrates the advantage of a quantitative assessment in comparing these distributions. It should also be noted that CCl4 is not included in this analysis due to known problems with non-polarizable models.84,85 The CCl4 electrostatic environment presents as an outlier from the other solvents, which reduces the usefulness of PCA for clustering solvents.

Notably, the lineshapes obtained by using the electrostatic vibrational maps for alcohols (MeOH, BuOH, and HexOH) cannot be simultaneously fitted to match the peak position and the experimental shapes (Fig. 5). In particular, the experimental spectra of methyl thiocyanate in alcohol solvents show a blue-shifted shoulder, which we attribute to σ-type hydrogen bonding interactions between the CN group and alcohol (see below). The attribution of the blue-shifted shoulder to σ-type hydrogen bonding is consistent with the previous work by Oh et al.37 This difficulty highlights the limitations of spectral correlation by electrostatic maps in that the principal components of methanol and butanol are distinctively different, but their spectra are similar.

FIG. 5.

Area-normalized FTIR spectra of MeSCN in methanol, butanol, and hexanol (solid lines). Filled areas represent spectra generated from MD simulations and individual vibrational maps.

B. Vibrational spectra from electrostatic maps

In order to further probe the apparent lack of connection between the electrostatic environment and the lineshapes, we investigated four different ways of map generation and application: (1) direct fit of map parameters to the FTIR spectrum for each solvent individually, (2) global fitting of map parameters for many solvents together, (3) map transfer from one solvent to an electrostatically similar solvent that shows a different spectrum (acetonitrile vs DMSO), and (4) map transfer optimized for one solvent to other solvents with the same functionalities, but different in solvent charge distribution (alcohol series). Cases 3 and 4 are intended to search for a connection by treating the electrostatics/spectra as the controlled variable and the spectra/electrostatics as the manipulated variable, respectively. For each of these scenarios, the root-mean-square-errors (RMSE) between the calculated and experimental spectra are given in Table I.

TABLE I.

RMSE values (×10−3) between experimental and calculated spectra from vibrational maps in four scenarios: (1) a direct fit of map parameters to FTIR for each solvent individually, (2) global fitting of map parameters for all five solvents simultaneously, (3) map transfer from one solvent to an electrostatically similar solvent that shows a different spectrum (acetonitrile vs DMSO), and (4) map transfer optimized for one solvent to other solvents with the same functionalities, but different in solvent charge distribution (butanol to methanol and hexanol).

| Solvent system | (1) Individual map RMSE | (2) Multi-solvent map RMSE | (3) ACN/DMSO swap RMSE | (4) Butanol for alcohols RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACN | 5.98 | 10.82 | 9.60 | ⋯ |

| DMSO | 3.26 | 7.43 | 6.28 | ⋯ |

| Hexanol | 4.89 | 6.30 | ⋯ | 4.25 |

| Butanol | 2.03 | 5.72 | ⋯ | ⋯ |

| Methanol | 5.39 | 7.01 | ⋯ | 8.82 |

Based on the deviations of the vibrational map spectra from the experiment in Table I, we find that the electrostatic vibrational maps do not generally perform well outside of their training solvent environment. Case 1 establishes baseline levels for the expected RMSE for the map in each solvent, which is used to compare the following cases. In case 2, the spectroscopic map was calibrated for all solvents simultaneously, resulting in an average map that does not fit any of the individual spectral data specifically. The map was able to roughly match the peak positions of the alcohols but resulted in poor peak positions for the other two solvents and strange lineshapes in all cases (Fig. 6). In case 3 (see Fig. S3 of the supplementary material), the acetonitrile map was used for DMSO and the DMSO map was used for acetonitrile. This significantly decreased the performance for both vibrational maps, primarily due to a shift in the peak position. In case 4 (see Fig. S4 of the supplementary material), the map for butanol was used on the other alcohol systems. Interestingly, it performs poorly on methanol, but very well on hexanol, even outperforming the map created in the hexanol environment. Based on the PCA, we believe that these results are due to the similarity of the electrostatic environment of hexanol and butanol and the dissimilarity of methanol and butanol. Overall, the results from different fitting procedures show that vibrational electrostatic maps do not show good transferability and extrapolation to different chemical environments, even when those environments seem similar.

FIG. 6.

Plot of the experimental and calculated spectra resulting from case 2, a single vibrational map fit to all spectra represented in Table I simultaneously. Solid lines are experimental spectra and filled areas are calculated infrared spectra. These spectra are area-normalized.

C. Origin of solvatochromic shifts

To further probe the underlying mechanism responsible for the differences in various solvent environments, we next turn to a more direct approach, namely, a representation that explicitly treats both the potential energy surface (QM/MM) and the vibrational energies (QVP) quantum-mechanically, to gain further insights into the factors that contribute to the observed spectral features.

1. Nuclear quantum effects

The experimental and computed IR spectra of the CN stretch mode in different solvents using the QVP@PBE/6-31G(d) method are displayed in Fig. 7(a), respectively, and the numerical values are given in Table II. In addition, we have analyzed the effects of non-electrostatic interactions and computed the spectral lineshapes without including the van der Waals forces in Fig. 7(b). Both results in Figs. 7(a) and 7(b) were obtained using the quantum vibration perturbation method up to the fourth order (QVP4). Finally, for comparison, we report in Fig. 7(c) the line-shape functions determined by using the classical molecular dipole autocorrelation function (DAF) based on Eq. (4).

FIG. 7.

Amplitude-normalized IR lineshapes of the CN stretch mode of MeSCN in different solvents. The experimental spectra are given in (a) along with the computed lineshape functions in shaded areas, obtained using the quantum vibration perturbation (QVP) method. (b) displays the computed lineshape functions without van der Waals forces between the solute MeSCN and solvents. (c) gives the Fourier transform lineshapes from the dipole–dipole autocorrelation functions. Note that the intrinsic vibrational frequency is underestimated by −7.7 cm−1 using the PBE/6-31G(d) method relative to the experimental value of MeSCN, which is systematically reflected in all solvents in the computed values in all results. If this systematic shift is corrected (see Fig. S5 of the supplementary material), the computed and experimental spectra are well-superimposed in (a). The spectra in MeOH are depicted, showing that the right-hand side of the line-shape is broader than that on the left-hand side.

TABLE II.

Experimental and computational absorption peak positions and solvatochromic shifts for the C≡N stretching mode of MeSCN in water and organic solvents. Water was used as the reference for solvatochromic shifts. Vibrational frequencies are computed using the Quantum Vibration Perturbation (QVP) method up to fourth order with (νQVP) and without van der Waals contributions (νQVP_ele), and using Fourier transform of dipole autocorrelation functions (νdipole). Frequencies are given in wavenumbers (cm−1).

| Solvent system | νexp | νQVP | νQVP_elea | νdipole | Δνexp | ΔνQVP | Δνdipole |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | 2163 | 2152.8 | 2142.8 | 2189.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| CCl4 | 2161.9 | 2152.2 | 2150.8 | 2194.9 | −1.1 | −0.7 | 5.3 |

| Et2O | 2160 | 2149.5 | 2147.5 | 2192.9 | −3.0 | −3.3 | 3.3 |

| MeOH | 2160 | 2148.8 | 2145.5 | 2186.2 | −3.0 | −4.0 | −3.3 |

| THF | 2157.5 | 2148.2 | 2146.8 | 2191.5 | −5.5 | −4.7 | 2.0 |

| DMSO | 2153 | 2142.8 | 2140.8 | 2180.2 | −10.0 | −10.0 | −9.3 |

| MUDa | 0.8 | 3.9 |

Mean unsigned deviation (MUD) relative to experimental values.

First, we find that the computed spectral lineshapes from the QVP4 model are in good accord with the experimental FTIR spectra both in the relative positions at the maximum peak in different solvents and in the details of the spectral lineshape, including the weak shoulder on the high-frequency side of the frequency maximum in the MeOH solvents.37 Recall that the PBE/6-31G(d) method underestimates the CN stretch frequency by 7.7 cm−1 relative to the experimental value in the gas phase. In comparing the experimental and computational spectra, we expect that the absolute vibrational frequencies from the present MD simulations are systematically shifted to the red by the same amount, about 8 cm−1. Overall, the mean unsigned error in spectral shifts relative to that in water is 0.8 cm−1 in the maximum peak positions in different solvents. In particular, we note that the computed CN frequency is blue-shifted in water by 10 cm−1 relative to that in DMSO, which is in excellent agreement with experiments, indicating that the computation approach is reasonable, and the computational results can be further analyzed to provide insights into the origin of the observed spectral shifts.

It is interesting to note that the peak positions displayed in Fig. 7(c) on the spectra obtained by Fourier transform of the DAF (Table II) are systematically blue-shifted by about 40 cm−1 relative to those from the QVP4 calculations, in which the vibrational Schrödinger equation is solved numerically using the DVR method. Since the same potential energy function was used in both approaches with the same dynamic trajectory, the difference between the two methods can be attributed to nuclear quantum effects (NQE) of the oscillator. Similar effects have been observed in the spectra of HCl–water clusters.32 In the latter case, the smaller reduced mass involving a hydrogen atom exhibits an even greater NQE than the present case.86 These results suggest that it is necessary to include NQE in order to obtain accurate results on the vibrational spectral lineshapes using an explicit simulation method with specific intermolecular interactions.

2. Effects of electrostatic vs van der Waals interactions

To gain an understanding of the roles of electrostatic and van der Waals forces, we have computed the spectral lineshapes by excluding van der Waals interactions in the analysis, which are displayed in Fig. 7(b). The most striking finding is that the van der Waals effects are not evenly presented in different solvents. By comparison of Figs. 7(a) and 7(b), we find that the peak position in water is red-shifted by 10 cm−1, whereas the magnitudes of the spectral shift in other solvents are relatively smaller. Furthermore, we find that the shoulder, which is notable in MeOH solvent, is absent and there is a significant reduction in spectral linewidth. Thus, the van der Waals interactions play a role in restricting the range of the CN stretch mode by placing a strong solvent boundary, thereby, a steeper repulsive potential energy curve. This contributes to blue shifts in the peak position as well as to the details of the spectral lineshape.43 Therefore, we can define the spectral shifts originating from van der Waals and electrostatic effects as follows, whose numerical results are summarized in Table III:

| (7) |

| (8) |

TABLE III.

Frequency shift originating from the van der Waals and electrostatic effect of the CN stretching mode of MeSCN (vibrational frequencies given in cm−1).

| Solvent system | ΔνvdW | Δνelec |

|---|---|---|

| H2O | −10 | 17 |

| CCl4 | −1.4 | 9 |

| Et2O | −2 | 12.3 |

| MeOH | −3.3 | 14.3 |

| THF | −1.4 | 13 |

| DMSO | −2 | 19 |

The above interpretation is confirmed by analyzing the specific hydrogen bonding configurations extracted from the dynamics trajectories. Specifically, the “blue shift” phenomenon of CN stretching vibration can be attributed to the σ-type of hydrogen bonding interactions between the solute and solvent molecules.41 Notably, these van der Waals interactions are not included in the electrostatic vibrational maps. Figures 2(a) and 2(c) shows that the CN stretch moves directly along the σ-hydrogen-bonding axis, experiencing strong repulsive forces due to van der Waals interactions as the solute nitrogen atom extends further into the solvent shell (Fig. 8). Consequently, the van der Waals repulsive force contributes a significant component along the direction of the CN bond, resulting in a compressed CN bond length.87 On the other hand, in the π-type of hydrogen-bonding configurations Figs. 2(b) and 2(d), the CN bond stretch is orthogonal to the solvent molecule, giving rise to a weak dependence on the van der Waals interactions. Thus, the observed red shifts in CN stretch frequency in water and methanol are smaller than those in a polar solvent such as DMSO due to the presence of σ-type H-bonds. The frequency-shifting behaviors are quite similar to those for azido- and nitrile-derivatized probes.37,44,88,89 This contrasts with carbonyl compounds, where the relationship between H-bonding and vibrational frequency found for the C=O stretch exhibits only strong electrostatic characteristics. We attribute this behavior to the fact that there is one lone pair of electrons for nitrogen to form a σ-type H-bond in the direction along the CN bond, while C=O can form two strong H-bonds as in an sp2 hybridization. Since only the electrostatic effect of the solvent on the solute is considered in Fig. 7(b), the computed spectra are purely a reflection of the electric field projected on the stretch model.

FIG. 8.

Rigid potential energy scan along the bond vector between nitrogen of MeSCN and the donor hydrogen of water.

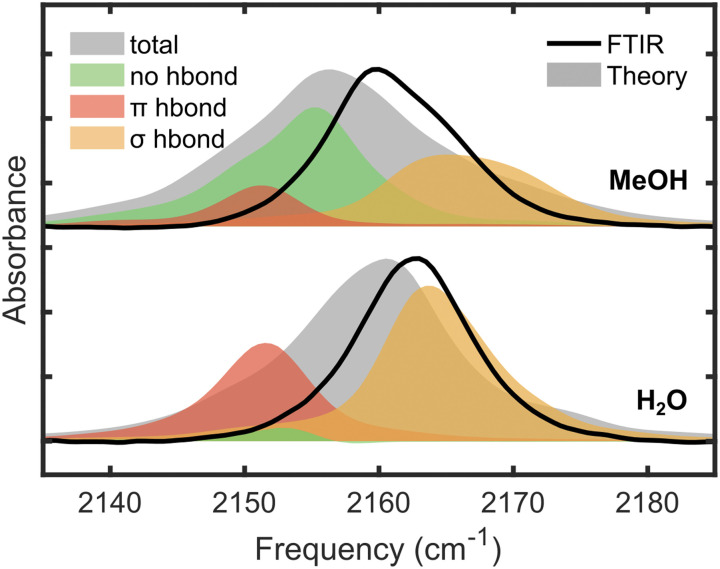

3. Specific hydrogen-bonding contributions

We have analyzed structural effects between solute and solvent interactions in water and in methanol in view of the unusually large effect of van der Waals terms and the change in spectral lineshape. To this end, we classified the configurations in the MD trajectories into three categories: (1) σ-type hydrogen-bonding interactions, (2) π-type of hydrogen-bonding geometries, and (3) no hydrogen-bonding interactions. Then, we determined the vibrational spectra based on Eq. (3) for each of the three structural categories. However, we note that this spectral decomposition is approximate since the structures in each category are not continuously and equally separated in time. Nevertheless, as will be seen below, they still provide useful interpretations and qualitative insights.

As shown in Fig. 9, the dominant type of structures consists of the σ-type hydrogen-bonding interactions in water, accounting for 61% of all configurations in the dynamics trajectory. The remaining population is mainly of the π-type hydrogen bonds with a tiny fraction of structures without exhibiting close contacts with the CN group in water. On the other hand, in MeOH, the dominant population of the three structural types belongs to that having no hydrogen bonds,37 followed by the σ-type and a small fraction of the π-type hydrogen-bonding patterns. The peak maxima of the σ-type hydrogen bonded structures and those having no hydrogen bonds differ by 10 cm−1, exhibiting a significant broadening effect on the blue side of the peak. Figure 9 shows that the two different types of hydrogen bonding components in MeOH are responsible for the shoulders on both sides of the central peak position.

FIG. 9.

For this figure, the hydrogen bond is defined when the distance between N(MeSCN) and H(H2O) is less than 2.5 Å. For the σ-type, the hydrogen bond angle (∠N⋯HO) is over 130°. All other angles are categorized as π-type hydrogen bonds. Calculated spectra are shifted positively by 7.7 cm−1 to better overlay with experimental FTIR.

IV. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

The results are consistent with the previous literature in demonstrating that van der Waals and other non-electrostatic forces are necessary for accurate reproduction of vibrational spectra with nitrile and azide probes.38,41–43 Electrostatic interactions expressed in terms of field and potential are necessary, but not sufficient for describing frequency shifts and lineshapes in dynamic environments. We have illustrated that in specific cases where two solvents have similar electrostatic and steric environments (butanol and hexanol), a purely electrostatic map may be adequate for describing the peak position and width. However, the limitations of transferability are serious and not easily predictable with electrostatics alone. Furthermore, even in the case where we found map transferability, the electrostatic map was, expectedly, still unable to describe hydrogen bonding environments and van der Waals forces and produce accurate lineshapes. In other words, limited map transferability is not sufficient evidence to show that a map adequately describes a system. This is especially relevant when the intent of the map is to be extrapolated to further systems, i.e., from solvent environments to protein environments. Explicit implementation of van der Waals forces is a promising avenue for further development, as demonstrated by Małolepsza and Straub.90 It is interesting to note that close examination of the local electrostatic environment can be a valuable guide toward understanding the nature of hydrogen-bonding and dipole–dipole interactions with the cyano group in terms of geometry (σ vs π) and the relative charge density around the molecule. However, this knowledge is unreliable for predicting whether or not a thoroughly validated vibrational spectroscopic map for one solvent would be applicable equally well in a new system. A complete picture of the energy landscape provided by QVP provides structural and energetic insights into the interactions that would otherwise remain unseen by a classical view of the local environment.

As illustrated in this study, QVP is an efficient method to provide accurate lineshapes and peak positions for thiocyanate vibrational probes. The vibrational spectra of the SCN group are rather complex and show large variations in different solvents. Yet, the SCN functional probe can provide rich information on the local structural details and the dynamics of the surrounding environment and shows an incredible promise for use in the study of biological systems. In fact, in comparison with a simple electrostatic map, the QVP approach remains expensive for on-the-fly dynamics simulations. Nevertheless, the fundamental insights provided by QVP analysis, in addition to its ability to output data on the scale of classical MD, will allow for a targeted development of vibrational maps focusing on specific intermolecular interactions that contribute most significantly to the energy landscape of a given system.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material for figures of the direct-fit vibrational maps for the eight solvents, the principal component scores, cases 3 and 4 in Table I, and an adjusted version of Figs. 7(a) and 7(b) to overlay the FTIR and calculated spectra.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The study at Shenzhen Bay Laboratory was partially supported by the Shenzhen Municipal Science and Technology Innovation Commission (Grant No. KQTD2017-0330155106581) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21533003). The work at UT Austin was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R35GM133359) and the Welch Foundation (Grant No. F-1891). Simulations were carried out at the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC) and at the SZBL Supercomputing Facility.

Note: This paper is part of the JCP Special Topic on Time-Resolved Vibrational Spectroscopy.

Contributor Information

Carlos R. Baiz, Email: mailto:cbaiz@cm.utexas.edu.

Jiali Gao, Email: mailto:gao@jialigao.org.

AUTHOR DECLARATIONS

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

R.Z. and J.C.S. contributed equally to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chabal Y. J., Surf. Sci. Rep. 8, 211 (1988). 10.1016/0167-5729(88)90011-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.L. G. Wade, Jr., Organic Chemistry, 8th ed. (Pearson Education, Inc., 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos S. and Thielges M. C., J. Phys. Chem. B 123, 3551 (2019). 10.1021/acs.jpcb.9b00969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buhrke D., Oppelt K. T., Heckmeier P. J., Fernández-Terán R., and Hamm P., J. Chem. Phys. 153, 245101 (2020). 10.1063/5.0033107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park J. Y., Mondal S., Kwon H.-J., Sahu P. K., Han H., Kwak K., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 153, 164309 (2020). 10.1063/5.0025289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deniz E., Valiño-Borau L., Löffler J. G., Eberl K. B., Gulzar A., Wolf S., Durkin P. M., Kaml R., Budisa N., Stock G., and Bredenbeck J., Nat. Commun. 12, 3284 (2021). 10.1038/s41467-021-23591-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beć K. B., Grabska J., and Huck C. W., Anal. Chim. Acta 1133, 150 (2020). 10.1016/j.aca.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lansford J. L. and Vlachos D. G., Nat. Commun. 11, 1513 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-15340-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su K.-Y. and Lee W.-L., Cancers 12, 115 (2020). 10.3390/cancers12010115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamm P. and Zanni M., Concepts and Methods of 2D Infrared Spectroscopy (Cambridge University Press, New York, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu Q., Zhou R., Liu J., Sun J., and Wang Q., Nanomaterials 11, 1353 (2021). 10.3390/nano11051353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrer N., Vib. Spectrosc. 6, 381 (1994). 10.1016/0924-2031(93)e0081-c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman D. J., Fica-Contreras S. M., and Fayer M. D., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 13949 (2020). 10.1073/pnas.2003225117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alperstein A. M., Molnar K. S., Dicke S. S., Farrell K. M., Makley L. N., Zanni M. T., and Andley U. P., PLoS One 16, e0257098 (2021). 10.1371/journal.pone.0257098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valentine M. L., Cardenas A. E., Elber R., and Baiz C. R., Biophys. J. 118, 2694 (2020). 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Getahun Z., Huang C.-Y., Wang T., De León B., DeGrado W. F., and Gai F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 405 (2003). 10.1021/ja0285262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon H. A., Alfieri K. N., Clark K. A. A., and Londergan C. H., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 850 (2010). 10.1021/jz1000177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fafarman A. T., Webb L. J., Chuang J. I., and Boxer S. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13356 (2006). 10.1021/ja0650403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adhikary R., Zimmermann J., and Romesberg F. E., Chem. Rev. 117, 1927 (2017). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrews S. S. and Boxer S. G., J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 11853 (2000). 10.1021/jp002242r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Slocum J. D. and Webb L. J., Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 69, 253 (2018). 10.1146/annurev-physchem-052516-045011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dalton S. R., Vienneau A. R., Burstein S. R., Xu R. J., Linse S., and Londergan C. H., Biochemistry 57, 3702 (2018). 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baryiames C. P., Ma E., and Baiz C. R., J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 11895 (2020). 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c09086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stani C., Vaccari L., Mitri E., and Birarda G., Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 229, 118006 (2020). 10.1016/j.saa.2019.118006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan J., Zhang J., Li C., Luo Y., and Ye S., Nat. Commun. 10, 1010 (2019). 10.1038/s41467-019-08899-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baiz C. R., Lin Y.-S., Peng C. S., Beauchamp K. A., Voelz V. A., Pande V. S., and Tokmakoff A., Biophys. J. 106, 1359 (2014). 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riistama S., Hummer G., Puustinen A., Dyer R. B., Woodruff W. H., and Wikström M., FEBS Lett. 414, 275 (1997). 10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01003-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petit T. and Puskar L., Diamond Relat. Mater. 89, 52 (2018). 10.1016/j.diamond.2018.08.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boashash B., Proc. IEEE 80, 520 (1992). 10.1109/5.135376 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buchner M., Ladanyi B. M., and Stratt R. M., J. Chem. Phys. 97, 8522 (1992). 10.1063/1.463370 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin Y.-S., Shorb J. M., Mukherjee P., Zanni M. T., and Skinner J. L., J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 592 (2009). 10.1021/jp807528q [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xue R.-J., Grofe A., Yin H., Qu Z., Gao J., and Li H., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 13, 191 (2017). 10.1021/acs.jctc.6b00733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baiz C. R., Błasiak B., Bredenbeck J., Cho M., Choi J.-H., Corcelli S. A., Dijkstra A. G., Feng C.-J., Garrett-Roe S., Ge N.-H., Hanson-Heine M. W. D., Hirst J. D., Jansen T. L. C., Kwac K., Kubarych K. J., Londergan C. H., Maekawa H., Reppert M., Saito S., Roy S., Skinner J. L., Stock G., Straub J. E., Thielges M. C., Tominaga K., Tokmakoff A., Torii H., Wang L., Webb L. J., and Zanni M. T., Chem. Rev. 120, 7152 (2020). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edington S. C., Flanagan J. C., and Baiz C. R., J. Phys. Chem. A 120, 3888 (2016). 10.1021/acs.jpca.6b02887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee H., Choi J.-H., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 137, 114307 (2012). 10.1063/1.4751477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried S. D., Bagchi S., and Boxer S. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11181 (2013). 10.1021/ja403917z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh K.-I., Choi J.-H., Lee J.-H., Han J.-B., Lee H., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 128, 154504 (2008). 10.1063/1.2904558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morales C. M. and Thompson W. H., J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 7597 (2011). 10.1021/jp201591c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rey R. and Hynes J. T., J. Chem. Phys. 108, 142 (1998). 10.1063/1.475389 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fafarman A. T., Sigala P. A., Herschlag D., and Boxer S. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12811 (2010). 10.1021/ja104573b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Wilderen L. J. G. W., Kern-Michler D., Müller-Werkmeister H. M., and Bredenbeck J., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 19643 (2014). 10.1039/c4cp01498g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Błasiak B., Ritchie A. W., Webb L. J., and Cho M., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 18094 (2016). 10.1039/c6cp01578f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Błasiak B., Londergan C. H., Webb L. J., and Cho M., Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 968 (2017). 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Choi J.-H., Oh K.-I., Lee H., Lee C., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 128, 134506 (2008). 10.1063/1.2844787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garcia-Viloca M., Nam K., Alhambra C., and Gao J., J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 13501 (2004). 10.1021/jp047526g [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Błasiak B. and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 140, 164107 (2014). 10.1063/1.4872040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin H., Li H., Grofe A., and Gao J., ACS Catal. 9, 4236 (2019). 10.1021/acscatal.9b00821 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olson C. M., Grofe A., Huber C. J., Spector I. C., Gao J., and Massari A. M., J. Chem. Phys. 147, 124302 (2017). 10.1063/1.5003908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senn H. M., Thiel W., Senn H. M., and Thiel W., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 48, 1198 (2009). 10.1002/anie.200802019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kulik H. J., Zhang J., Klinman J. P., and Martínez T. J., J. Phys. Chem. B 120, 11381 (2016). 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b07814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cong Y., Zhai Y., Yang J., Grofe A., Gao J., and Li H., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24, 1174 (2021). 10.1039/D1CP04490G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanommeslaeghe K. and MacKerell A. D., J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 3144 (2012). 10.1021/ci300363c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanommeslaeghe K., Raman E. P., and MacKerell A. D., J. Chem. Inf. Model. 52, 3155 (2012). 10.1021/ci3003649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vanommeslaeghe K., Hatcher E., Acharya C., Kundu S., Zhong S., Shim J., Darian E., Guvench O., Lopes P., Vorobyov I., and Mackerell A. D., J. Comput. Chem. 31, 671 (2010). 10.1002/jcc.21367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Perdew J. P., Burke K., and Ernzerhof M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996). 10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., and Klein M. L., J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926 (1983). 10.1063/1.445869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jorgensen W. L., Maxwell D. S., and Tirado-Rives J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225 (1996). 10.1021/ja9621760 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nam K., Gao J., and York D. M., J. Chem. Theory Comput. 1, 2 (2005). 10.1021/ct049941i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Darden T., York D., and Pedersen L., J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089 (1993). 10.1063/1.464397 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H. J. C., and Fraaije J. G. E. M., J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brooks B. R., Brooks C. L., Mackerell A. D., Nilsson L., Petrella R. J., Roux B., Won Y., Archontis G., Bartels C., Boresch S., Caflisch A., Caves L., Cui Q., Dinner A. R., Feig M., Fischer S., Gao J., Hodoscek M., Im W., Kuczera K., Lazaridis T., Ma J., Ovchinnikov V., Paci E., Pastor R. W., Post C. B., Pu J. Z., Schaefer M., Tidor B., Venable R. M., Woodcock H. L., Wu X., Yang W., York D. M., and Karplus M., J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1545 (2009). 10.1002/jcc.21287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abraham M. J., Murtola T., Schulz R., Páll S., Smith J. C., Hess B., and Lindahl E., SoftwareX 1–2, 19 (2015). 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berendsen H. J. C., van der Spoel D., and van Drunen R., Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 43 (1995). 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00042-e [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Light J. C., Hamilton I. P., and Lill J. V., J. Chem. Phys. 82, 1400 (1985). 10.1063/1.448462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Echave J. and Clary D. C., Chem. Phys. Lett. 190, 225 (1992). 10.1016/0009-2614(92)85330-d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Colbert D. T. and Miller W. H., J. Chem. Phys. 96, 1982 (1992). 10.1063/1.462100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sullivan J. F., Heusel H. L., and Durig J. R., J. Mol. Struct. 115, 391 (1984). 10.1016/0022-2860(84)80096-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao J., Ma S., Major D. T., Nam K., Pu J., and Truhlar D. G., Chem. Rev. 106, 3188 (2006). 10.1021/cr050293k [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gao J. and Xia X., Science 258, 631 (1992). 10.1126/science.1411573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andrews S. S. and Boxer S. G., J. Phys. Chem. A 106, 469 (2002). 10.1021/jp011724f [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fried S. D. and Boxer S. G., Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 998 (2015). 10.1021/ar500464j [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kim H. and Cho M., Chem. Rev. 113, 5817 (2013). 10.1021/cr3005185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Faid K. and Fox R. F., Phys. Rev. A 34, 4286 (1986). 10.1103/physreva.34.4286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mukamel S., Principles of Nonlinear Optical Spectroscopy (Oxford University Press, 1995). [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kwac K., Lee H., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 120, 1477 (2004). 10.1063/1.1633549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sagnella D. E., Straub J. E., Jackson T. A., Lim M., and Anfinrud P. A., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96, 14324 (1999). 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bu L. and Straub J. E., Biophys. J. 85, 1429 (2003). 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74575-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bu L. and Straub J. E., J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 12339 (2003). 10.1021/jp0351728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sagnella D. E. and Straub J. E., Biophys. J. 77, 70 (1999). 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)76873-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bader J. S. and Berne B. J., J. Chem. Phys. 100, 8359 (1994). 10.1063/1.466780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Harp G. D. and Berne B. J., Phys. Rev. A 2, 975 (1970). 10.1103/physreva.2.975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gao J., Proc. - Indian Acad. Sci., Chem. Sci. 106, 507 (1994). 10.1007/bf02840766 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Song L., Han J., Lin Y.-l., Xie W., and Gao J., J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 11656 (2009). 10.1021/jp902710a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kunz A.-P. E., Eichenberger A. P., and Van Gunsteren W. F., Mol. Phys. 109, 365 (2011). 10.1080/00268976.2010.533208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Szklarczyk O. M., Bachmann S. J., and Van Gunsteren W. F., J. Comput. Chem. 35, 789 (2014). 10.1002/jcc.23551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ceriotti M., Fang W., Kusalik P. G., McKenzie R. H., Michaelides A., Morales M. A., and Markland T. E., Chem. Rev. 116, 7529 (2016). 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Li X., Liu L., and Schlegel H. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 9639 (2002). 10.1021/ja020213j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Oh K.-I., Lee J.-H., Joo C., Han H., and Cho M., J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 10352 (2008). 10.1021/jp801558k [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Choi J. H., Oh K. I., and Cho M., J. Chem. Phys. 129, 174512 (2008). 10.1063/1.3001915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Małolepsza E. and Straub J. E., J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 7848 (2014). 10.1021/jp412827s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for figures of the direct-fit vibrational maps for the eight solvents, the principal component scores, cases 3 and 4 in Table I, and an adjusted version of Figs. 7(a) and 7(b) to overlay the FTIR and calculated spectra.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.