Abstract

Background

Understanding the psychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in vulnerable groups, such as pregnant and parenting women, is a critical research and clinical imperative. Although many survey-based perinatal health studies have contributed important information about mental health, few have given full voice about the experiences of pregnant and postpartum women during the prolonged worldwide pandemic using a qualitative approach.

Objective

The purpose of this study is to explore the lived experience of pregnant and postpartum women in the United States during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

Qualitative phenomenological study.

Setting

This study was conducted in the community, by recruiting women throughout the U.S.

Participants

Fifty-four pregnant and postpartum women participated in qualitative interviews.

Methods

Data from one-on-one semi-structured interviews were analyzed using a team-based phenomenological qualitative approach.

Results

Two key themes were apparent: the pandemic has shined a light on the many typical struggles of motherhood; and, there is a lack of consistent, community-based or healthcare system resources available to address the complex needs of pregnant and postpartum women, both in general and during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Going forward, as the world continues to deal with the current pandemic and possible future global health crises, health care systems and providers are encouraged to consider the suggestions provided by these participants: talk early and often to women about mental health; help pregnant and postpartum women create and institute a personal plan for early support of their mental health needs and create an easily accessible mental health network; conceptualize practice methods that enhance coping and resilience; practice in community-based and interdisciplinary teams (e.g., midwives, doulas, perinatal social workers/ psychotherapists) to ensure continuity of care and to foster relationships between providers and pregnant/ postpartum women; and consider learning from other countries’ successful perinatal healthcare practices.

Registration

Number (& date of first recruitment): not applicable.

Tweetable abstract

Pregnant and postpartum women insist that mental health care must be overhauled, stating the pandemic has highlighted inherent cracks in the system.

Keywords: Perinatal, Pregnancy, Postpartum, Pandemic, Mental healthcare, Qualitative

Introduction

The novel coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19) has had a significant and lasting impact on the health and well-being of populations across the world (Wang et al., 2020). The United States government and healthcare systems have instituted policies and recommendations to protect the public's health, including mask-wearing, social distancing, and quarantine. While many of these public health measures have limited the spread of the disease, they have also had psychosocial and mental health impacts (Vindegaard and Benros, 2020, Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2021, Hotopf et al., 2020). A recent review by Suwalska and colleagues (2021) suggests that alterations to prenatal appointments, lack of social support, financial difficulties, health status, and other COVID-related stressors have been identified as key risk factors for perinatal anxiety and depressive sympto (Suwalska et al., 2021). A study of a sample of 524 pregnant and postpartum women revealed that women who had major family concerns, job concerns, and low resilience and adaptability scores seem to be at highest risk of psychological sequelae (Kinser et al., 2021). Although many survey-based studies have contributed important information about depressive symptoms and anxiety in perinatal women, few of these studies have explored the actual qualitative experience of pregnant and postpartum women during the pandemic.

Several recent calls to action encourage researchers to understand the mental health and biopsychosocial impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in vulnerable groups, such as pregnant and parenting women (Holmes et al., 2020, O’Connor et al., 2020). A qualitative study is necessary to create space for women to voice their experiences during this unique time in our world's history. A qualitative study design may enable insights into how the concept of resilience arises in women's experiences. An understanding of complex concepts such as social connection, coping, and resilience (Preis et al., 2020) is essential in the planning for future prevention and intervention strategies regarding perinatal mental health during acutely stressful events. This phenomenological qualitative study was designed to shed light on women's personal experiences and healthcare interactions; given that qualitative research is not hypothesis-driven, we intended to create space for women to share all aspects of their experience. These data may contribute to development of interventions and prevention strategies for the current and subsequent public health crises.

Methods

This hermeneutic phenomenological qualitative study involves a subset of pregnant and postpartum participants from a parent study who expressed interest in participating in in-depth interviews. The parent study, described elsewhere, (Kinser et al., 2021) is an observational study evaluating psychosocial quantitative survey data in adult pregnant and postpartum (up to 6 months post-delivery) women first enrolled in April-June 2020 in the U.S. This was the initial U.S. shutdown timeframe and thus captured the acute reactions to the pandemic. There was no in-person contact for recruitment, enrollment, or data collection. Upon approval from the university's Institutional Review Board, women who met the parent study's inclusion criteria (pregnant or up to 6 months postpartum in April-June 2020) were recruited through social media posts, email listservs, direct contact via phone or text message, and word of mouth from providers or other individuals in the community. Interested individuals engaged in the informed consent and data collection processes via an electronic capture system hosted on servers at the study university.

For this qualitative study, team members contacted participants from the parent study who volunteered to be interviewed. Interviews were conducted October 2020 through January 2021 by team members trained in qualitative interviewing (PK, NJ, SM, MW, DB, NM, LS, AR). Interviews were conducted and recorded via Zoom in private settings, were transcribed, and checked for accuracy. Continuous consent was obtained at every contact with the participant, with reminders about confidentiality. All interviewers used the same semi-structured interview guide; examples of questions are listed in Table 1 . Because the qualitative data were not connected with demographic data from the parent study, basic demographic information was collected at the completion of the interview (age, race/ethnicity, and marital status of participant; number of living children). Interview questions were adapted over time as key themes arose that warranted follow-up, consistent with the concept of emergent design that is often used in qualitative research (Rodgers, 2009, Rodgers and Cowles, 1993). No repeat interviews occurred. To address any potential distress that may have arisen during the interviews, interviewers provided information about Postpartum Support International (postpartum.net) to all participants at the completion of the interview. Interviews ranged in time from 30 minutes to two hours, with the average length of interview approximately one hour.

Table 1.

Examples of Questions used by Interviewers during Semi-Structured Interview.

| 1. Tell me about your experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, overall. How has it been to be pregnant and/or a parent during this time? |

| 2. What advice do you have for other pregnant and postpartum women during this time, or, thinking ahead to any situations like this that might occur in the future? |

| 3. Can you tell me about feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression that you might have experienced during your pregnancy and/or the postpartum period? What resources have you accessed that were helpful? What resources have you wished you could access? |

Ethical approval for the larger parent study and for this qualitative study was obtained by the university's Institutional Review Board (#HM20019176).

Data Analysis

A hermeneutic phenomenological qualitative approach was utilized, as it is based on the goal of understanding a phenomenon by examining individuals’ interpretations of their experiences and how they assign meaning to these experiences, with an awareness of the impact of the researcher's subjective experience and biases (Cohen et al., 2000, Thomas and Pollio, 2002). The use of “hermeneutics” reflects that there is an iterative interpretation process by the researcher about the themes in the participants’ experiences (Cohen et al., 2000). As a first step, the analysis team (PK, NJ, SM, MW, DB, NM, LS) met to engage in reflexivity and discuss personal biases (e.g., preconceived ideas, beliefs, assumptions) that could affect the data analysis process. Several members identified their current roles as mothers and other members identified their roles as maternal mental health researchers, both of which could serve as a potential bias towards mental health issues. All members acknowledged that they would likely empathize with many of the pandemic experiences expressed by our participants. We identified that the interviews were conducted during a time of unrest in the United States: the presidential election and the Black Lives Matter movement were occurring at the time, which affected many of the analysis team members in a variety of personal ways. We recognized the need to constantly acknowledge our personal biases, in order to allow the voices of the participants to shine through the analysis process. For example, some members of the team expressed concern that they might over-empathize with participants who remarked about discrimination or hope for a certain election result; thus, the team reminded each other to avoid the use of leading questions or comments. Throughout the course of the data collection and analysis, the team returned to conversations acknowledging personal biases to continually emphasize reflexivity.

Using a team approach, we followed the analysis process described in Cohen et al. (2000). In the manner of a hermeneutic circle, the team used an iterative process whereby the meanings of small units of data (e.g., quotes) were analyzed within the context of the whole text of the transcribed interviews as well the context of the participants. Of note, consistent with hermeneutic phenomenology, fieldnotes were maintained by interviewers and were included in the interview transcriptions; these notes contained descriptions by the interviewers about details observed during the interview sessions (e.g., participant behaviors, the setting as observed through the Zoom camera, noises or other distractions in the participants’ spaces, and similar) as well as personal reflections of the interviewer (Cohen et al., 2000). The use of the hermeneutic circle allowed the team to interpret individual participant experiences not only within the larger context of all participants’ data but also within the context of the reflexive stance of researcher-as-instrument (e.g., the participants experiences interpreted within the pandemic as a common context; biases/ assumptions revealed in fieldnote, and similar). In order to provide a coherent picture of participants’ experiences, the team explored the data for commonalities and differences by engaging in thematic analysis, and ultimately, a figure was developed to depict the interpretation of key themes and sub-themes. No a priori coding was used. The analysis team met monthly to report on their individual processes, the analysis, and interpretations of the data and theme development.

The analysis team used several strategies to ensure trustworthiness of the findings. Credibility, or the confidence that identified themes accurately represent participants’ experiences, was addressed through peer debriefing in which a colleague who did not participate in the primary analysis process (AR) reviewed the data and confirmed the findings (Lincoln and Guba, 1986). Dependability, or consistency of findings, was ensured by having several authors engage in independent analysis of the data prior to the group process (Lincoln and Guba, 1986). To avoid researcher bias and ensure replicability and confirmability, we maintained an audit trail of decisions made regarding coding and thematic development during all analysis sessions (Rodgers and Cowles, 1993, Tong et al., 2007). Finally, we attempt to provide “thick description,” or description of a phenomenon in such detail that the reader may have the ability to consider transferability of findings to other people, settings, or times (Cohen et al., 2000, Lincoln and Guba, 1986). Further, data was analyzed in an iterative, spiral process that enabled constant questioning and reinterpretation in an attempt to face and minimize personal research team biases (Cohen et al., 2000).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Fifty-four pregnant and postpartum women participated in the qualitative interviews. Demographic characteristics are described in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Population (n=54).

| Characteristic | n (%) or Mean (STD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 34.38 (4.15) |

| Marital Status Single Partnered/ married Divorced/ separated Unknown |

0 (0%) 49 (91%) 0 (0%) 5 (9%) |

| Self-identified Race/ Ethnicity Black/ African-American White/ Caucasian More than one race/ethnicity Other Unknown |

3 (5.6%) 43 (79.6%) 5 (9.3%) 1 (1.9%) 2 (3.7%) |

| Status during Interview Pregnant at time of interview Postpartum at time of interview |

1 (1.9%) 53 (98.1%) |

| Mean reported number of children in household | 2 (0.76) |

| Motherhood Status during Pandemic First-time mother (primiparous) Experienced mother (multiparous) |

25 (46.3%) 29 (53.7%) |

Themes

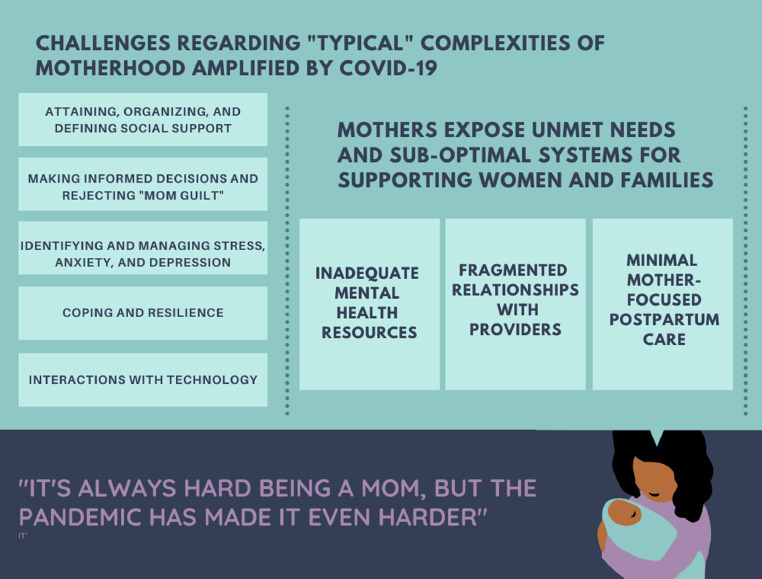

The key themes that arose from the qualitative interviews were centered around the following: (1) the typical complexities of new motherhood have been amplified by the uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic; and, (2) women voiced concerns about unmet needs and sub-optimal systems for supporting women and their families– both in general and during a public health crisis. Within these key themes were several sub-themes, represented in Fig. 1 . Quotes that support these themes are provided below.

Fig. 1.

Visual representation of key qualitative findings.

Key Theme #1: Uncertainties of Pandemic Amplified Complexities Typical in Motherhood

Throughout every interview, participants consistently expressed a generalized sense of uncertainty. This sense of unknown created an experience whereby they were challenged to evaluate whether their experiences of uncertainty were due to the typical complexities of motherhood or the global pandemic. Many participants expressed that “it's always hard being a mom, but the pandemic has made everything harder” and that everything was “more daunting with the unknowns.” Most women acknowledged they expected this sense of uncertainty due to the arrival of a new child in their life. Yet, the general loss of control experienced in the perinatal period was compounded by the loss of control in the pandemic, which was then experienced as pervasive stress and anxiety, and in some cases, depressive symptoms. Participants felt “helpless” and “freaked out” for much of the time, knowing that “the stress of everything going on right now will not go away for a long time”. For example, a pregnant participant with her second child summarized this experience: the perinatal period naturally involves “a lot of isolation and huge amounts of anxiety anyway”, but with COVID the anxiety “becomes enormous and catastrophic.” Other participants echoed this sentiment, such as the following statement from a first-time mother:

When you have a new baby, there is a sense to savor these moments. The undercurrent of the pandemic, of this constant discussion of death, has been stressful when you're already adjusting to such a big life shift on your own well-being. I had really bad prenatal anxiety and crazy panic attacks.

Participants acknowledged the major loss of their vision for their pregnancies, their postpartum period, and the experience of being a new mom. As one mother expressed “my whole schema was falling apart” whereby the pandemic stripped away their plans and their ideals.

Although not expressed by all participants, the continual uncertainty related to the pandemic was compounded for some participants by the larger context of political election unrest and a social justice movement in the United States. For example, one participant stated: “being a black woman and being pregnant is literally the happiest and most terrifying experience.” Participants worried about their own mental health as well as the emotional development of their children. Many participants also expressed frustration about “COVID politics” causing a challenge to controlling the pandemic: “It takes a village to raise a child. And because of the pandemic, the village got stripped away from us... longer than it needed to because of other people's inability to sacrifice a little bit for the greater good. Very frustrating.” These contextual aspects of the experience created a sense of living in a “gray area”, in which nothing was clear or easy or typical.

Subtheme: Challenges with attaining, organizing & defining social support: Mothers consistently reflected upon the importance of attaining, organizing, and defining social support, whether as a new mother or an experienced mother bringing a new child into the world. The complexity of doing this within the context of a pandemic was enormously challenging. Many participants spoke in language of losses and being unseen/ unheard/ uncared for: “Coronavirus robbed me of my pregnancy, of my postpartum period” and “my whole schema of what the postpartum time was supposed to look like was falling apart- no family support- I have no idea how we got through it.” Many often expressed a wish for their “village, the whole network” to help them with this uncertainty of pregnancy plus pandemic, which was largely impossible for the majority of participants. A lack of connectedness was a pervasive theme in the perinatal experience.

There was a significant sense of grief and loss with regard to in-person activities that would have typically been available such as prenatal education groups, prenatal yoga classes, postpartum mom support groups, play groups, and similar. These activities often provide a space for women to share experiences, advice, and support with each other. Without them, there was a profound sense of loss expressed by many participants: “I was surprised at how upset I was that (my baby shower) got cancelled” and “I really missed the physical intimacy- nobody got to touch my belly or measure it.” Many women had plans to engage with other mothers, such as the participant who stated “I have lost that sense of community with mothers. I had so many plans, giving him opportunities to interact with other babies- and that was taken away from me.” In particular, new mothers expressed a significant sense of loss: “I really wish I had access to other first-time moms going through this. I just want to be able to speak with other women who are going through this.” In summary, women felt “Pretty much everything has been taken away and it was just a loss.” These losses of “typical” activities and experiences with other mothers, family members, and friends required a re-organizing and defining of social support.

Sub-theme: Challenges with making informed decisions and rejecting “mom guilt”: Another tension experienced by participants pertained to decision-making regarding every aspect of being a mother in light of COVID precautions. Participants reported the “cumulative fatigue” of making constant, pandemic-related personal and family health decisions, in addition to the typical decision-making complexities of pregnancy and the postpartum period. For example, one participant highlighted how this decision-laden experience of being a new mother was made worse during the pandemic: “where are you going to feed her, where is she going to sleep, are you going to try pumping? Those are the decisions that come, pandemic or not. To add on more difficult decisions, and the multitasking that is required of living through [the pandemic] is just exhausting.”

Participants felt challenged to be confident in their decisions which might have been at odds with others’ decisions, particularly in the context of obtaining social support. As several participants described, they declined offers of social support in settings where “some people think that things are safe that I don't think are safe.” Many women had to forgo necessary support because of “this big gray cloud of disease and death around”, forcing them to consider “what way can I feel safest and most supported for myself and my baby?” Tensions were experienced when their decisions clashed with opinions of others: “The hardest part was managing expectations from family– having to explain they are not allowed in the hospital and not allowed to hold the baby. We got a lot of pushback.” Participants were forced to identify the most like-minded individuals with whom to interact, engaging with only those “on the same page as you” and with “values in line with mine.” Many participants reported the challenges with decision-making related to returning to work and sending children back to school or daycare, within the context of incredible fatigue:

When I had to go back to work, that's when we decided to take on the risk of sending them to school, because the options were: we don't make any money and everyone's mental health is basically trash, or we send them to school and we go back to work… I've had to process the trauma and grief of bringing a baby into a global pandemic… my husband and I haven't had a night off from parenting since March. It's a nonstop marathon of parenting with no support.

The constant questioning of decision-making by all, compounded by “typical mom-guilt,” was experienced as significant stress and anxiety: “Just knowing if I'm making the right choice or not has given me a lot of anxiety.” Participants feel that this constant questioning has defined their experience of pregnancy and new motherhood: “It was really, really hard. I chewed on all the options. I really had to lean into how was I going to be the best to myself... and for my baby.” Although many women reported that the ability to work virtually and stay home with their child helped eliminate stress, several women expressed concern that staying home constantly affected their mental health. One mother provided an example of feeling constant guilt: “I have mom guilt every day. Am I potentially endangering my children for my benefit, by sending them to school? My mental health is directly linked to my family's health.” One participant provided an example of guilt related to self-care: Sometimes I even feel guilty about sitting, and then I have to remind myself that five or ten minutes is the difference between being a present mom and somebody who is so overstressed that I can't be present for my children.”

Sub-theme: Challenges with identifying and managing stress, anxiety, and depression: Participants reported mental health symptoms, ranging from panic attacks and feelings of “nervous breakdowns.” Others used phrasing such as “postpartum COVID-anxiety” and having “waves” of depression and anxiety. Many women attributed this to the combination of pandemic unknowns and losses of typical supportive activities. Women were profoundly affected by their loss of a community, a “village” to support them through this transition period. One participant described feeling “invisible and invalidated. I'm really struggling here, this is really hard. I want someone to be real and say this sucks, and I'm here for you and how can I help you.” Women felt alone and without a mental health safety net: “With not having friends around, with not having much of a support network visible- that's what prevented me from feeling like I was cared for. With the ruminating thoughts came suicidal ideation.” Women described desiring interactions with other mothers and grieving the loss of a postpartum “village”: “I just wish that there were more mom groups. I don't feel I have a village. I do have a village of my family, but I don't have a village of non-family people to reach out to.” Participants who were mothers prior to the pandemic expressed concern for new mothers in the pandemic and their loss of typical community-based resources: “I do really worry about women and postpartum depression. I had postpartum depression pretty bad with my first child and the thing that helped me the most was being with other moms”.

Sub-theme: Challenges and opportunities for coping and resilience: For some participants, the pandemic challenged them to enhance their own personal resilience. In contrast to the tensions noted above, some, but not all, expressed in hushed tones and apologetic wording that they felt grateful for the privacy and quiet created by the pandemic. They made statements such as “I know there are so many people who are just not in good places… but I've had overwhelmingly a positive experience.” Participants stated they enjoyed having time to get to know their new baby without the distraction of friends, family, and co-workers. For many women and their partners, the ability to work from home has created an opportunity for “bonding time that I wouldn't have had.” Several participants expressed that they were “grateful that we've had this time to be with her and see her changes– like when she laughed for the first time.” For some women, the time at home had the beneficial effects of extended breastfeeding and strengthened partner relationships. This is exemplified in one participant's statement that the pandemic “provided me an opportunity to spend more time with my child and for my husband to spend more time with us. We were just focused on the three of us and spending that time really bonding.”

Once participants were able to acknowledge the loss of their ideal pregnancy or postpartum period, they described being able to “curate a lifestyle” that best met their personal needs. Several women discussed coping strategies such as exercise and being outdoors. The majority of participants identified that “getting my kids outside has been helpful and exercise is good” and “enjoying nature without feeling rushed” have been important coping strategies. One woman described having to force herself to “leave the house and get some sunlight”, recognizing that the isolation was affecting her mood. For others, constant family time was a “blessing and a curse”, and would find “escape routes” such as sitting in the car alone and taking advantage of open daycare to get some time to oneself.

Several participants’ quotes suggest that part of building resilience was in crafting a narrative of positivity and gratitude. This is summarized in one comment that “I have realized it's okay for me to grieve the losses that I have felt… it is really helpful to allow myself to be sad about it. But I don't want it to overtake the joy that I do have in being a mom, and he makes me smile every day.” Another participant stated: “It is important to recognize the weight that all moms have been carrying and give ourselves a lot of grace.” Participants acknowledged that things could be worse (“at least it's not a war”, “he's healthy and we haven't lost a job”) and some women expressed that focusing on their families helped them cope.

It must be acknowledged that, although many of the participants expressed gratitude for some of the opportunities of the pandemic, several participants were struggling to cope. For example, some mothers were acting as single parents: some women did not have partners and others had partners deployed in the military. These women highlighted that being a single parent and struggling to carry the family responsibilities alone might be difficult during “typical” times, but it became immensely more challenging during the pandemic. One woman summarized it as having “a garbage year” and that she was “not thriving.” Other participants were not feeling the same sense of gratitude and were clear about their frustrations with the on-going limitations: “I just can't wait until this shit is over... I want to hug my mom. I want my mom to give my son a kiss, not a mask.” Many participants were considered essential workers, and thus did not have the option to stay home and work virtually. They expressed a complete lack of coping mechanisms and social support: “I just haven't been able to have social interactions that I normally would've had” and “I've had to separate myself from my typical coping mechanisms.” Others identified the challenge of the pandemic restrictions which meant they could not bring their child with them to postpartum appointments, thus were forced to find childcare and potentially expose their child to the virus. Finally, some participants were frustrated with the phrase “self-care”, as exemplified in one woman's struggle: “They say ‘do self-care’ and I'm thinking- ‘what is that?’ It's hard to build it in your life intentionally. This whole year I've struggled- priorities are work, baby, spouse, my mom and dad, and then me, last.”

Sub-theme: Challenges and opportunities related to technology: Technology was a key aspect of the COVID and perinatal experience and, in many instances, it was considered to be a “double-edged sword”. Technology was consistently discussed as both a challenge and opportunity, in that it enabled participants to have many needs met but that technology was rarely an appropriate or substantial substitute for real contact with others.

The benefits of technology seemed to center around being able to have access to social support and healthcare providers. The majority of women described the benefits of connecting with friends and family through technology: “Support has made all the difference. I couldn't do any of it without technology- having Zoom and Google hangouts to be able to see people who are far away and won't be able to come visit has been super nice.” In the postpartum period, many women have found virtual visits to be simpler than in-person: “it's almost easier to hang out without having to drag the baby out and worry about naps… I can connect with my friends and family members and never have to leave my house.” Connection with a larger network of other mothers through social media was important: “I used the ‘Baby Center’ app and ‘KellyMom’ website a lot- finding community there was helpful, almost more helpful than going to the pediatrician about breastfeeding.” Women also reported: “we had a virtual baby shower, and it was phenomenal.” Participants expressed gratitude for the “game changer” that their employers learned that “much of my work can be done on Zoom”, thus enabling time for “the family to bond.”

The participants reported many challenges related to technology. Consistent with many others’ sentiments, one participant highlighted the pros and cons of using social media: “In some instances [a pregnant-during-COVID Facebook group] has been helpful… helpful in finding information about what the women were experiencing when they were delivering. And then, after I had the baby, I found it to be a place that only increased anxiety.” Many participants described needing to “detox” from social media because of its all-consuming and anxiety-provoking qualities. While social media could be a place to obtain support, it often became a place for “mindless scrolling.”

Key Theme #2: Mothers Give Voice to Unmet Needs and Sub-Optimal Systems for Supporting Women and Families

An overarching theme revealed in the study interviews was that the pandemic exacerbated cracks in the perinatal healthcare system. The majority of the participants in this study expressed gratitude to the study team for providing an opportunity to discuss the myriad of unmet needs and sub-optimal systems and resources available for perinatal women in the United States. Participants’ descriptions of their recent experiences during the pandemic revealed dichotomies regarding mental health resources, limited access to providers, and deficits in mother-focused postpartum care.

Sub-theme: Inadequate mental health resources: Participants reported significant challenges accessing formal mental health resources. Barriers included difficulty finding therapists with availability, who accepted participants’ insurance, and who had a perinatal mental health specialty. As one woman reported: “people are having trouble finding counselors or psychiatrists. I need that person-to-person connection.” For example, one mother described accessing mental health virtually: “the good news is that I was able to connect with a counselor right away and do virtual sessions. But all of this I say from a complete point of privilege.” Even women with financial means struggled to access specialists with expertise in perinatal mental health: “Sure, they put me on a SSRI [antidepressant], but that's only half the equation. Accessing mental health treatment was a joke. I think we're putting women at higher risk by not acknowledging that they need real-time support.” Several women appreciated the convenience of receiving mental health services via telehealth (“I love talking to my therapist sitting on my couch in my pajamas”), but the majority of these participants had established relationships with their providers prior to the pandemic. Many participants described difficulty finding care: “They couldn't get me in until I was ten weeks postpartum. And then they dropped me as a patient because they don't deal with financial hardship. So I didn't have any kind of means of getting any kind of counseling or postpartum depression help. There was just no way of getting any help.” Another stated “I couldn't ever find anyone who was comfortable dealing with pregnancy and depression or anxiety.”

Participants described that they had created a mental health plan early in their pregnancy, so if/when anxiety or depressive symptoms arose, there were specialists already lined up. One participant described this as: “an action plan… Be explicit with your partner about expectations. My partner, midwife, and my therapist were both aware of what to do if [depression symptoms] got bad… I authorized my therapist to allow my husband to schedule appointments for me. My therapist helped me find a psychiatrist in case I needed medicine.” When imagining a better future, one participant suggested that “It would be great to build ahead a framework for support and a network to connect and support individuals… where you can meet and feel safe.” Another participant suggested that it should be a standard procedure for providers to not rely on a depression screening tool but rather to “really check-in- how are you feeling? How are you coping with your feelings? Every single pregnancy doctor's visit could use that question. Every single one.” Women consistently suggested that no woman is going to answer screening tools honestly unless a provider is sitting with them and shows interest in having a conversation about mental health: “Six weeks after my c-section, I got a phone call and all it was- ‘Do you need any birth control? Are you depressed? See you in a year.’” Importantly, many women suggested that they were too sleep-deprived and overwhelmed in the postpartum period to sort through finding an appropriate therapist. One participant described how important it was to have a navigator through her employer who was able to secure a perinatal mental health specialist for her.

Sub-theme: Fragmented relationships with healthcare providers: Participants described varied and contradictory experiences with their perinatal and mental health providers during the pandemic. First, telehealth was a significant aspect of their experiences, which some participants experienced as positive and some did not. On the positive side, many participants appreciated the convenience of telehealth to eliminate barriers regarding transportation, child care, and general convenience. However, some participants felt uncared for when appointments were cancelled or switched to telehealth. For one participant, telehealth appointments late in pregnancy felt inadequate: “I personally didn't like [telehealth] toward the end of pregnancy. I needed to know if everything was running well” and “I was extremely stressed out because I wanted to hear his heartbeat, still wanted to make sure he was measuring okay [but I couldn't because there were only phone call visits]. I was freaking out. I had no idea what was going on and that was very stressful.” For another participant, cancelled appointments in the postpartum period exacerbated the isolation of that time: “that was pretty big for me because that was a traumatic period in my life. I felt very alone at that point. I was totally on my own.” Some participants described several physical issues that were left undetected (e.g., mastitis, non-healing and infected wounds) because they did not have an in-person postpartum visit. One participant stated that she was “high risk- I wasn't monitored as closely as I probably would've been. It's very hard to do a virtual OB visit!” Having the experience of a previous pregnancy was helpful to many participants, as one woman who stated: “I'm really glad that this is my second pregnancy and not my first, because I can only imagine being the first and not even knowing what you're supposed to see and feel, and then being responsible to relay those symptoms via some virtual visit.” Most participants acknowledged that fragmentation of care was pervasive: “Telehealth changes everything. It changes the way you express yourself. It changes the way that you are physically experienced, even the practice of looking into someone's eyes is different.”

Second, participants described concerns about how providers were communicating with them. Several participants appreciated that their providers empowered them to monitor their own health and make decisions for themselves and their families, with minimal input from the provider. For example, some participants purchased home monitoring equipment (e.g., blood pressure cuffs, fetal monitors) so that they could monitor their health and their developing babies. However, the majority of mothers were frustrated that communication remained at one end of the continuum or the other– that there were either absolute directives or no directives at all. For example, on one end of the spectrum (absolute directives), one participant described this as: “It would be helpful if our clinicians had more language around risk mitigation and balance. I've had practitioners say ‘absolutely no one can come and help with your baby’ and I was like– ‘look, I have a history of anxiety. I must have help.’ A little more richness or the ability to discuss risk trade-off would've been far more helpful than absolutism.” On the other side (no advice whatsoever), one participant expressed a wish that her providers had provided guidance about how to handle the barrage of information/ misinformation regarding the virus: “The reality is, they have more data than I do as a sleep-deprived, non-medical mom.”

Sub-theme: Postpartum care only minimally focuses on mothers: During the interview, many participants took an opportunity to reflect upon perinatal care of women in general in the United States. More than half of the participants had had children prior to the pandemic, so they often compared their recent pandemic-specific experiences with their previous perinatal journeys. Of note, several participants were highly complimentary of their care during labor and delivery and pediatricians’ care of their newborns, highlighting that many providers were “doing the best they can” in the pandemic situation. Many participants identified having strong relationships with their midwives, which helped them feel continuity of care: “The relationship with providers is key. I felt like the midwives really cared about me as a person and I could be honest with them. I can't imagine seeing your ‘stereotypical’ OB who sees you in five minutes and doesn't have time to talk.” However, more than a few women suggested that the pandemic was highlighting existing cracks in the healthcare system regarding care of women. For example, one participant stated:

We're already so far behind in women's health as a nation. I fear that this is going to set us even further back. Our care for women was already pretty lackluster, and that impacts a whole future generation of people. That's a big reason why I wanted to participate in this [research study]. I want people to keep talking about how COVID has many waves behind it.

Many participants identified that postpartum care in the United States is insufficient for fully supporting women in the journey through motherhood. Many women expressed general concerns about inadequate postpartum care focused on women's physical and mental health, not just due to the pandemic. One participant highlighted this concern, stating:

I want to feel taken care of by my providers, but the prenatal care that is the standard in the US is very focused on risk assessment and mitigation. It's garbage- it will keep you alive, but it won't support any of these massive psychosocial transitions that happen. So much of what is challenging or difficult or stressful about pregnancy and the transition to motherhood is about routines, relationships, and day-to-day adaptations; it's about the disconnect between expectations and reality– whether in relationships, body changes, health, nutrition. These are things that are better supported in community. We don't have a formal way in our society or in our healthcare system to facilitate this.

Sub-theme: Ideas for the Future: The mothers in this study provided ideas for ways to enhance care. First, women suggested that discussions of mental health should start early in pregnancy and even in pre-conception and that resources should be clearly available. For example, a participant described her experience trying to find mental health resources:

All I wanted was a list of providers that said ‘specialty: postpartum’. I was not about to call all the providers on a huge list from my EAP [Employee Assistant Program] and ask ‘do you see pregnant women?’ in the moment, with a newborn and a three year old, in the midst of a pandemic with no childcare and working full time. Anyone who needs mental health treatment is already in a fog... and it needs to be clear [how to get help].

This participant suggested that providers should

“talk to women in their preconception days around depression and anxiety. [Tell them] you're probably going to have postpartum depression. Have those conversations early and often. I lied on most of the responses to the surveys at postpartum appointments- I was embarrassed, I guess.”

Other participants echoed this sentiment, suggesting that it would be helpful for providers and mothers to have a clearer understanding of the trajectory of needs that a woman might have throughout the entire postpartum period. For example, one participant suggested:

“We need to… map out the typical developmental mood changes that happen in the two years postpartum related to hormone shifts, sleep deprivation, and role transitions… Something that your team of midwife, doula, perinatal social worker is going to [use to] check-in with you on regular intervals… and have a referral system for people who need more support”

The participant suggested that this approach could eliminate the sense of isolation that many other women in the study reported feeling during their postpartum period.

Second, a few participants suggested that the United States should take notes from the successes of other countries that provide better postpartum care to women. For example, one participant suggested that standardized home visiting could be helpful: “I read how in other countries they do home visiting… [providers] see the environment people are living in and [can address] all the basic life skills that contribute to postpartum success, the new generation's success too.” Another participant brought up the “problem of the six-week visit”, highlighting that waiting six weeks after delivery is too long for women to wait to receive care. Other participants suggested that postpartum care needs to be sustained beyond that six-week visit as well. Finally, it was recommended to consider a shift in the healthcare system away from “pathology and reimbursement” and create a better sense of community-based care. For example, one participant suggested the following:

I would love to see a “pod system” of interprofessional care. The continuity is what's important- where someone who knows your story is there to advocate– people like community health workers or doulas or care coordinators. It's hard even as a well-resourced, well-educated person to figure out making appointments, getting prescriptions, getting referrals… and God forbid you need something like specialist care or transportation support or child care– all of these that create the barriers to engaging in well-being behaviors. Human flourishing is an important goal.

Discussion

In this qualitative phenomenological study, 54 pregnant and postpartum women were interviewed October 2020 - January 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic. As identified in these qualitative data, the pandemic has brought to light not only the complexities of motherhood, in general, but also the fact that most mothers in the U.S. face sub-optimal perinatal health support systems. Participants provided insights and suggestions for how to structure a personal network and how the healthcare system can provide enhanced quality of care for women.

The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly impacted the participants in many ways: disruption of family jobs and income; social isolation; interruption/loss of normal routines; concern for their health as well as children, family and friends, constantly changing/shifting information/policies surrounding the spread and control of the disease as well as perinatal healthcare delivery within the context of no knowledge/assurance when or how long this would last. Such unexpected challenges lead to a pervasive sense of unknown and uncertainty aptly described by participants as a feeling of living in a “gray area,” in which they experienced continual repeated stress, as well as anxiety and depression symptoms. These findings are consistent with extant literature about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2021) and are also consistent with existing literature on exposure to past epidemics and natural disasters. For example, high levels of depressive symptoms were reported during the SARS CoV-outbreak (Wu et al., 2020), the 2008 Iowa floods (Brock et al., 2015) and Hurricane Katrina (Harville et al., 2009); emotional distress such as anxiety and anger were commonly reported during the MERS outbreak (Jeong et al., 2016); and increased anxiety was identified during the Ebola outbreak. (Morganstein and Ursano, 2020) Likewise, during this COVID-19 pandemic, women during the perinatal period reported high levels of stress, anxiety, and depression (Basu et al., 2021, Farewell et al., 2020, Tomfohr-Madsen et al., 2021); those who engaged in passive coping (e.g., higher use of screen time, intake of comfort foods) experienced higher levels of psychological distress. (Werchan et al., 2022)

The mental health repercussions of COVID-19 during the perinatal period poses unique challenges for women and their families, as well as their health care providers. Of long-term concern are the potential lingering effects demonstrated in previous studies in which participants reported the psychological distress persisting for months (Jeong et al., 2016) and years. (Liu et al., 2012) In addition, uncertainty intensifies stress, provokes fear, worry, anxiety, and perceptions of vulnerability, which may lead to avoidance of decision making at the very time informed decisions are critical for health and wellbeing. (Hillen et al., 2017, Esterwood and Saeed, 2020) Clinicians will need to remain vigilant to assess for mood disorders for the “long haul” and be prepared to support with consistent messaging, and distinct guidance. Clinicians will also need to identify women in need of mental health care and provide “psychological first aid” focused on reducing distress and promoting adaptive function. (Esterwood and Saeed, 2020, Farewell et al., 2020, Giarratano et al., 2019)

Social support is a known protective factor against mental health symptoms in the perinatal period. (Yu et al., 2021, Robertson et al., 2004) Results from this study highlight the extent to which social isolation negatively influenced the postpartum period during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, literature collectively suggests that social isolation increases rates of psychiatric symptoms. (Vindegaard and Benros, 2020) The effect of social isolation can be amplified for pregnant and postpartum women, given the relative importance of social connectedness during this life stage. (Yu et al., 2021) Interestingly, previous studies have shown that social connection with other moms, in the form of groups, is a particularly effective mode of support. (Kinser and Masho, 2015, Strange et al., 2014) Yoga classes, mom groups, prenatal education seminars, and other programs typically allow mothers to establish relationships and receive encouragement. In the absence of these groups, many women turned to social media as a means to foster connection with other moms. Unfortunately, increased social media exposure during the COVID pandemic is associated with higher rates of depression and anxiety, perhaps due to the ease of access to distressing information. (Werchan et al., 2022, Gao et al., 2020, Geirdal et al., 2021) Thus, women in this study found themselves in a bind between their desire to connect and the negative mental health effects of social media use. It is important to continue to further understand how to utilize the beneficial aspects of social media while minimizing the psychological harm.

Multiple studies have highlighted the psychological toll of grief during the pandemic. (Bertuccio and Runion, 2020, Wallace et al., 2020) Grief played a prominent role in participants’ experiences, whether it was loss of a job, loss of a loved one, or loss of anticipated experiences. Indeed, many of the normalizing experiences that women looked forward to during the perinatal time (e.g. baby showers, family visits, mom groups) were fundamentally altered or cancelled due to the pandemic. However, despite an overall sense of loss, the participants collectively exhibited profound resilience in their ability to find the positives in their situation and engage in healthy behavior. Previous research shows that engagement in health behaviors and proximity to outdoor space is associated with less stress in those pregnant during the COVID-19 pandemic. (Werchan et al., 2022) Participants in this study actively sought outdoor spaces and engaged in self-care activities to deal with stress. Furthermore, the participants used healthy cognitive strategies, in particular, participants exhibited considerable gratitude for their personal situations and for the unexpected benefits of the pandemic (e.g. more time with their partner, ability to stay home with baby). Research shows that expressing gratitude increases psychological well-being. (Wood et al., 2010) Previous research has also shown that individuals often make meaning from high stress situations. (Calhoun and Tedeschi, 2014) The women in the study coped by finding positives and exercising gratitude, despite a pervasive sense of loss and grief over the unprecedented times

Participants in this study highlighted several important ideas that should be considered in the future, as methods to enhance the long-term health and wellness of women and their families. These suggestions are summarized in Table 3. The suggestions are consistent with emerging literature reflecting ongoing concerns about perinatal care in the United States. (Hendrix et al., 2021) The pandemic has played a key role in disruption of perinatal care for women, with significant impact on the mental health of pregnant and postpartum women. (Hendrix et al., 2021) However, this study has made it clear that the systems in place to support pregnant and postpartum women require improvements, whether or not there is a worldwide pandemic. Researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers alike must heed this call to action. The time is now to enact positive lasting change to support the health and well-being of women and their families.

Table 3.

Actionable Suggestions from Participants for Future Improvements to Care of Women in the Perinatal Period.

| Mother and Family | • Create personal “precautionary” plans and networks for mental health support in the preconception and early pregnancy period, in case they are needed • Brainstorm “easy” methods that enhance coping and resilience and ask your network of family and friends to support you in your use of these strategies |

| Healthcare Providers | • Talk early and often to pregnant and parenting women about mental health (without relying solely on screening tools), including in pre-conception and early pregnancy • Create a community-based and interdisciplinary team to ensure continuity of care, including midwives, physicians, doulas, community workers, navigators, and perinatal social workers • Facilitate easier access to perinatal-trained mental health workers, such as using navigators to assist women to connect with an appropriate provider |

| Healthcare Systems | • Take notes from other countries that are more successful with perinatal care • Create a system that supports relationship between pregnant/parenting women and providers, rather than being focused on reimbursement and risk mitigation |

Despite the important findings from this study, including the recommendations from participants for the future, there are several limitations of this study that must be highlighted. First, the majority of the participants self-identified as white/Caucasian and partnered/ married. Although our team suspects that this homogeneity is likely due to the use of social media as a major recruitment tool for the parent study, the lack of diversity in the study population limits generalizability of the findings. Second, the study participants were interviewed only one time, whereas it is clear that the pandemic has had a fluctuating course; there is potential that key aspects of participants’ experiences might not have been uncovered through a one-time interview. Third and finally, we did not ask about the exact location of participants (e.g., rural vs urban, area of the country) and the pandemic has affected different areas of the country in different ways, thus there could be bias due to lack of representation of certain geographic areas.

Conclusion

Two key themes were identified from the qualitative interviews with pregnant and postpartum women in this study: the pandemic shined a light on the many typical struggles of motherhood and on the lack of consistent, community/healthcare system resources available to pregnant and postpartum women. Going forward, as the world continues to deal with the current pandemic and possible future global health crises, health care systems and providers must consider the suggestions provided by these participants, which included the following: talk early and often to pregnant and parenting women about mental health; institute a personal plan for early support of mental health needs and create an easily accessible mental health network; conceptualize practice methods that enhance women's coping and resilience; create an interdisciplinary team that includes healthcare system providers communicating with community-based providers to ensure continuity of care, and one that fosters relationships between providers and pregnant/parenting women; and consider learning from other countries’ successful perinatal healthcare practices. Future research is needed to capture the voices of women across all socioeconomic and racial backgrounds.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this study provided by the Sarah P. Farrell Endowment Fund, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing (PI: Kinser). We thank the following individuals for their assistance in recruitment and data collection activities- Evelyn Jones, Mariana Telleria, Hannah Allen, and Nikki Monteserin.

References

- Basu A., Kim H.H., Basaldua R., Choi K.W., Charron L., Kelsall N., Hernandez-Diaz S., Wyszynski D.F., Koenen K.C. A cross-national study of factors associated with women’s perinatal mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertuccio RF, Runion MC. Considering grief in mental health outcomes of COVID-19. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S87–S89. doi: 10.1037/tra0000723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brock RL, O’Hara MW, Hart KJ, et al. Peritraumatic Distress Mediates the Effect of Severity of Disaster Exposure on Perinatal Depression: The Iowa Flood Study. J. Trauma Stress. 2015;28(6):515–522. doi: 10.1002/jts.22056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun L.G., Tedeschi R.G., editors. Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice. Routledge; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M., Kahn D., Steeves R. Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. Hermeneutic phenomenological research: A practical guide for nurse researchers. [Google Scholar]

- Esterwood E, Saeed SA. Past Epidemics, Natural Disasters, COVID19, and Mental Health: Learning from History as we Deal with the Present and Prepare for the Future. Psychiatr. Q. 2020;91(4):1121–1133. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09808-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farewell CV, Jewell J, Walls J, Leiferman JA. A Mixed-Methods Pilot Study of Perinatal Risk and Resilience During COVID-19. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11 doi: 10.1177/2150132720944074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zheng P, Jia Y, et al. Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID-19 outbreak. PLoS One. 2020;15(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231924. Published 2020 Apr 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geirdal AØ, Ruffolo M, Leung J, et al. Mental health, quality of life, wellbeing, loneliness and use of social media in a time of social distancing during the COVID-19 outbreak. A cross-country comparative study. J Ment Health. 2021;30(2):148–155. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2021.1875413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratano G, Bernard ML, Orlando S. Psychological First Aid: A Model for Disaster Psychosocial Support for the Perinatal Population. J. Perinat. Neonatal. Nurs. 2019;33(3):219–228. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harville EW, Xiong X, Pridjian G, Elkind-Hirsch K, Buekens P. Postpartum mental health after Hurricane Katrina: a cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-21. Published 2009 Jun 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, C., Werchan, D., Lenniger, C., et al. (2021). COVID-19 impacts on perinatal care and maternal mental health: A geotemporal analysis of healthcare disruptions and emotional well-being across the United States. SSRN. Available at doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3857679. [DOI]

- Hillen MA, Gutheil CM, Strout TD, Smets EMA, Han PKJ. Tolerance of uncertainty: Conceptual analysis, integrative model, and implications for healthcare. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017;180:62–75. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, …, Bullmore E. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotopf M., Bullmore E., O'Connor R.C., Holmes E.A. The scope of mental health research during the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2020;217:540–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.2020.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Yim HW, Song YJ, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38 doi: 10.4178/epih.e2016048. Published 2016 Nov 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser PA, Jallo N, Amstadter AB, …, Salisbury A. Depression, Anxiety, Resilience, and Coping: The Experience of Pregnant and New Mothers During the First Few Months of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Womens Health (Larchmt) 2021;30(5):654–664. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinser P, Masho S. Yoga Was My Saving Grace: The Experience of Women Who Practice Prenatal Yoga. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2015;21(5):319–326. doi: 10.1177/1078390315610554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln Y.S., Guba E.G. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation. 1986;30:73–84. doi: 10.1002/ev.1427. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, et al. Depression after exposure to stressful events: lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr. Psychiatry. 2012;53(1):15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morganstein JC, Ursano RJ. Ecological Disasters and Mental Health: Causes, Consequences, and Interventions. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:1. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00001. Published 2020 Feb 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DB, Aggleton JP, Chakrabarti B, …, Armitage CJ. Research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: A call to action for psychological science. Br. J. Psychol. 2020;111(4):603–629. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis H, Mahaffey B, Heiselman C, Lobel M. Pandemic-related pregnancy stress and anxiety among women pregnant during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2(3) doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson E, Grace S, Wallington T, Stewart DE. Antenatal risk factors for postpartum depression: a synthesis of recent literature. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2004;26(4):289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B.L., Cowles K.V. The qualitative research audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing and Health. 1993;16:219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B.L., Cowles K.V. The qualitative research audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing & Health. 1993;16(3):219–226. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B., Mateo & Kirchhoff . Research for advanced practice nurses: From evidence to practice. Springer Publishing; New York, NY: 2009. Chap 8: Qualitative research for nursing practice; pp. 129–154. [Google Scholar]

- Strange C, Fisher C, Howat P, Wood L. Fostering supportive community connections through mothers’ groups and playgroups. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014;70(12):2835–2846. doi: 10.1111/jan.12435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suwalska J, Napierała M, Bogdański P, Łojko D, Wszołek K, Suchowiak S, Suwalska A. Perinatal Mental Health during COVID-19 Pandemic: An Integrative Review and Implications for Clinical Practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(11):2406. doi: 10.3390/jcm10112406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Pollio H. Springer Publishing Company, Inc; New York, NY: 2002. Listening to Patients: A Phenomenological Approach to Nursing Research and Practice. [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr-Madsen L.M., Racine N., Giesbrecht G.F., Lebel C., Madigan S. Depression and anxiety in pregnancy during COVID-19: A rapid review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2021;300 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N., Benros M.E. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vindegaard N, Benros ME. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;89:531–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, White P. Grief During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Considerations for Palliative Care Providers. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(1):e70–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werchan D., Hendrix C., Ablow J., et al. Behavioral coping phenotypes and associated psychosocial outcomes in pregnant and postpartum women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific Reports. 2022;12(1):1209. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05299-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Froh JJ, Geraghty AW. Gratitude and well-being: a review and theoretical integration. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2010;30(7):890–905. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Zhang C, Liu H, et al. Perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms of pregnant women during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020;223(2):240. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.009. e1-240.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Sampson M, Liu Y, Rubin A. A longitudinal study of the stress-buffering effect of social support on postpartum depression: a structural equation modeling approach. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2021;1-15 doi: 10.1080/10615806.2021.1921160. [published online ahead of print, 2021 May 3] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]