Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has had strong economic repercussions on the industrial fabric of many countries around the world, with different degrees of impact depending on the level of severity with which the pandemic hit these countries. Italy has suffered a significant impact on its economy and export volumes have dropped dramatically for some product categories. The objective of this research is to understand how the pandemic has affected some selected logistics flows (i.e., fruit, automotive and machinery) transiting through the ports of Genoa and Savona, and to highlight the mitigation strategies that have been implemented during the pandemic period. The research was carried out analyzing customs and port data, as well as with the support of interviews and focus groups with experts of the Ligurian port sector. Finally, some policy indications are outlined with the aim of increasing the resilience of the supply chains analyzed in this research. These indications should help supply chains to be efficient and effective in forwarding flows of goods to/from ports even in the occurrence of unforeseen high-impact events.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Customs data, Ports, Goods categories, Resiliency, Mitigation strategies, Italian real case studies

1. Background and literature review

1.1. The COVID-19 pandemic and supply chains

The COVID-19 pandemic represents one of the most important supply chain (SC) disruptors in recent history, which has weakened and structurally modified many supply chains at a global level (Ivanov and Dolgui, 2020). Researchers have highlighted that modern supply chains, while efficient or hyper-efficient, are frequently rigid (O’Leary, 2020: O’Neil, 2020, Shih, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized the need to increase the robustness and resilience of logistics chains (Ivanov, 2020). In such a context, “robustness” relates to the ability of supply chains to maintain the same performance after a disruption (Simchi-Levi et al., 2018), whereas “resilience” denotes the ability of SCs to recover their performance after having absorbed the effects of the disruption (Ivanov, 2018, Hosseini et al., 2019, Barman et al., 2021, Nair and Vidal, 2011, Ponomarov and Holcomb, 2009, Spiegler et al., 2012, Baz and Ruel, 2021). The concept of resilience has been linked to three different levels by Ivanov and Dolgui (2019): a) absorptive capacity in the form of redundant inventory, b) adaptive capacity, such as the establishment of backup suppliers, and c) restorative capacity due to technology diversification (Hosseini et al., 2019).

To reinforce empirical research, the literature has focused on identifying the drivers to make supply chains more sustainable (Karmaker et al., 2021), discussing specific aspects such as localization, agility, and the characteristics of digitalization (Nandi et al., 2021). In this perspective, recent studies have highlighted that while COVID-19 has been responsible for economic downturns, it has had the merit of focusing attention on the need to make logistics chains more sustainable (Sharma et al., 2020).

While the impact of the pandemic on the performance of supply chains is undoubtable, the extent of the effects that may affect transport supply and demand are closely linked to the characteristics of specific supply chains. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the impact of COVID-19 on transport volumes and on the dynamics of freight capacity (Loske, 2020). The effects of COVID-19 related policies on supply chains have been investigated from different perspectives (Gereffi, 2020). For example, some studies have compared the effects of the pandemic on food, electronics, pharmaceutical and textile supply chains (Nikolopoulos et al., 2021).

The factors driving supply chain disruptions are often unclear. The dynamic forces of the supply chains differ substantially, not only by sector, but also on the basis of the characteristics of specific products, the strategies of the companies that produce them, and the distribution channels involved (Staritz et al., 2011). Furthermore, the drivers of supply chains are different in importing and exporting countries, in advanced industrial and developing nations, and in the countries where large multinational companies have their headquarters and their local branches (Stolzenburg et al., 2019, Horner and Alford, 2019).

Researchers of supply chains have tried to investigate the pandemic effects in a very limited time frame. A review of studies of supply chain related to the pandemic revealed the dominance of opinion articles. This is due to the unexpected onset and the overwhelming scope of the pandemic, and the limited opportunities for researchers to collect and analyze real-world data. Consequently, additional research with real data is needed (Chowdhury et al., 2021). The present study contributes to fill this gap through descriptive statistics and a survey-based method of investigation.

This paper focuses on the supply chains patterns of some selected logistics flows, namely fruit, automotive and machineries, which pass through the Italian ports managed by the Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority and their macro-regional context. The analysis is based on ports data, customs data and interviews/focus groups with the stakeholders involved, collecting key information on trade flows (Elliott and Bonsignori, 2019). In the context of the agri-food sector, many authors have already pointed out the significant difference between perishable goods and storable goods. During the pandemic, perishables were affected by the vulnerability of harvest and production phases, but benefited from the resilience of the transport and logistics sector, which ensured the supply of storable products to final consumers (Coluccia et al., 2021). Food consumption patterns have also been strongly affected by the pandemic. For example, eating out has been replaced by eating at home (Faour-Klingbeil et al., 2021).

In general, commodity trade among countries has been severely curtailed and the exportation of food products has been halted (Gray, 2020). The mitigation actions adopted by export companies mainly concern the sale of export-oriented commodities in the domestic market (Lin and Zhang, 2020). Another important element highlighted by the research is the concentration of interruptions of supply chains in Europe. This was a consequence of the shortage of foreign labourers due to the border blockade and not compensated by national labourers (COLDIRETTI, 2020). Forecasts of the future development of international trade remain very uncertain as the measures adopted today by governments are constantly changing (Gruszczynski, 2020).

Most existing papers regarding COVID-19 are analyses of the health and food industry, while very few focus on the machinery sector. One exception is Handfield et al. who studied the impact of the pandemic on the earth-moving equipment supply chain (Handfield et al., 2020).

1.2. The relationship between the Italian production system and logistics

Based on the framework described above, this research focuses on the impact of the pandemic on some supply chains involving two Northern Italian ports. despite Italy being the European nation with the lowest economic growth between 2009 and 2019, Italian imports and exports have increased due to the greater internationalization of some companies that sell ever greater shares of their goods on foreign markets. Italy currently imports 36% from the European Union, including energy products, while exports are more concentrated towards the EU (62%). Due to the geographic characteristics of Italy, all international trade passes through ports or Alpine border crossings. The growth of exports and imports in the pre-pandemic period led to net growth in transport and logistics. The strong elasticity of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of freight transport is mainly due to the following factors: internationalisation, significant presence of foreign operators, lengthening of international logistics chains, and new models of distribution logistics. In Italy the transport structure is heavily dependent on the road transport mode, and is mainly in foreign hands in terms of control of logistics chains (Cascetta, 2021). Italy suffered a devastating impact from COVID-19 with a drop in GDP of −8.8% in 2019/2020, compared to −6.8% in the Eurozone. There are many uncertainties regarding the post-COVID situation, particularly with respect to the trend of reshoring, the rising costs of transoceanic routes, the possible increase in intra-EU trade and a decrease in extra-EU commerce.

The logistics sector in Italy represents 9% of the national GDP and involves almost 100 thousand active companies, 1.5 million employees, and €85 billion turnover in 2019. The future challenges for this sector are (i) strengthening the country's position in shipping, where innovation is crucial to achieve the changes expected in energy transition and sustainability; (ii) the digitalisation and automation of ships and terminals; and (iii) abandoning the old vision of ports as merely places of departure and arrival of goods, and rather considering them as poles of economic development and intermodality (Panaro et al., 2021, Deandreis, 2021).

This paper analyzes how the pandemic has affected some important supply chains (fruits, automotive and machineries) that transit through the Italian ports of Genoa and Savona, with the ultimate goal of making these supply chains more resilient against unexpected events such as a pandemic.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the features of the Ligurian ports of Genoa and Savona and their related macro-regional context. Section 3 illustrates the methodology adopted in the present study, including the rationale behind the choice of the supply chains analyzed. A detailed analysis of the three selected supply chains - i.e., fruit, automotive and machineries - is provided in Section 4. Section 5 outlines some policy indications, whereas Section 6 provides some conclusions and suggestions for future research.

2. The ports of Genoa and Savona and their macro-regional context

The ports of Genoa and Savona, managed by the Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority, rank as Italy’s main port system in terms of total traffic, product diversity and economic output, handling 58,5 million tons, 2.5 million TEU and 12.1 million RO-RO tonnage in 2020. These two ports alone represent one third of the total freight throughput passing through Italian ports. They are also the most important in terms of extra-UE containerized maritime traffic. About 46% of export and 36% of import, in value, and about 33% of export and import, in weight pass through these ports.

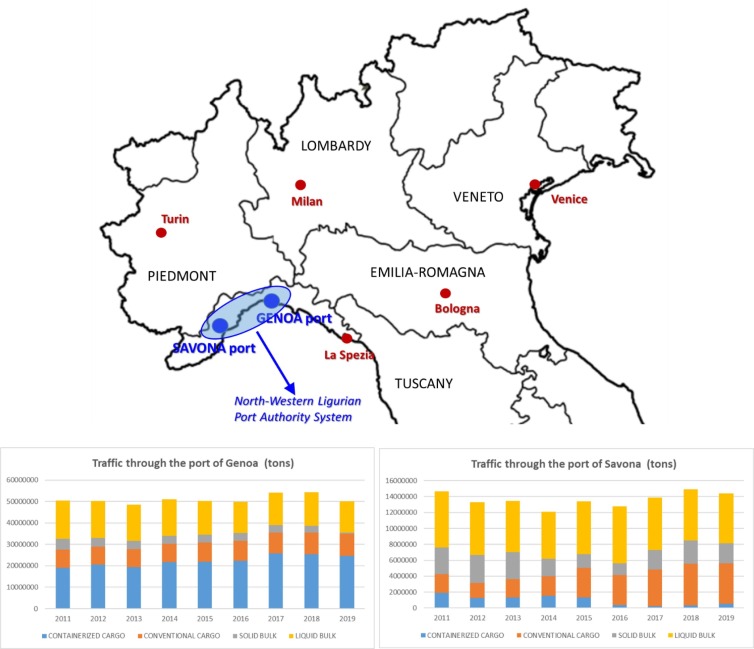

As shown in Fig. 2 , the catchment areas of the ports of Genoa and Savona are mainly represented by the regions of Lombardy, Piedmont, Emilia Romagna and Veneto, with some connections beyond the Alps. More specifically, 49.2% of the containerised traffic transiting through the ports of Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority are related to the Lombardy (49.2%), to Piedmont (20%) to Emilia Romagna (8.5%), and to Veneto (7.8%). These percentages fall to 16.3%, 6.6%, 2.8% and 2.6% when considering the traffic generated by all Italian ports. The catchment area of Genoa and Savona ports was already affected by significant changes in the pre-COVID period, such as an important concentration of traffic, and the pandemic seems to have accelerated these trends (Panaro et al., 2021).

Fig. 2.

Italian provinces of destination-IMPORT (left side) and origin- EXPORT (right side) Source: Italian Customs data.

A recent survey was conducted by Panaro et al. (2021) on the maritime economy and involved 400 companies representing 41% of Italy's GDP and 50% of Italian trade and based in Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Veneto. The study highlights that all Italian manufacturing sectors that use containerised transport have been significantly affected by COVID, with the exception of the agri-food and pharmaceutical sectors. The survey also revealed a process of traffic concentration: in the last three years, the port of Genoa has been used by 85% of companies for exports, with a growing trend. In particular, the port of Genoa is used for exports by 98% of Lombardy companies, 69% of Veneto companies and 93% of Emilian companies. In import, the port is used by 88% of companies with a strong upward trend in the last three years. Specifically, in import, the port of Genoa is used by 100%, 79% and 79% of companies located respectively in the regions of Lombardy, Veneto and Emilia. The main competitors in the containerized sector are represented by the ports of Venice, La Spezia, Ravenna and, only marginally, Trieste. Based on the same analysis, in the period affected by the pandemic, the use of intermodal transport decreased1 . The intermodal choice, which is preferable for sustainability reasons, is mainly influenced by the frequency of rail transport service and the difficulty in reaching economies of scale (Ferrando, 2021, Panaro et al., 2021).

Fig. 1 shows the location of the ports of Genoa and Savona in the Ligurian Sea and their traffic statistics, divided by cargo type, from 2011 to 2019. It can be noted that, before 2020, the overall traffic through the port of Genoa was, on average, about 50 million tons. In 2020 a large contraction of flows occurred due to COVID-19. The rate of change between 2019 and 2020 indicates a reduction of 14% in overall traffics (−9% for containerized cargo, −12% for conventional cargo, −6% for solid bulk and even −25% for liquid bulk).

Fig. 1.

The location of the ports of Genoa and Savona, and related traffic flows from 2011 to 2019 Source: Data of the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority.

Table 1 highlights the main 15 containerized and non-containerized cargo types, in terms of volume percentage, related to the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority (ports of Genoa and Savona), both for export and import flows for the year 2019. Table 1 evidences that there is a high degree of concentration of logistic flows in terms of weight, especially for non-containerized freight. 81% and 89% of respectively import and exports flows relate to the first 15 categories of goods. With regards to containerized freight, the degree of concentration is lower. Machinery and mineral fuel represent the most important freight categories, respectively for containerized and non-containerized cargo, which are managed by the two Italian ports as a whole. The “Fruit” category accounts for 3.3% of the total containerized goods, while the “Vehicles” represent respectively 2.3% an 7.7% of the total containerized and non-containerized cargo. The analyses carried out in this research focus on these three categories of goods due to their high percentages in terms of freight passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona.

Table 1.

Percentage of containerized and non-containerized volumes handled by the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority System, Export and Import, for 15 selected categories, Year 2019.

|

Containerized freight |

Non-containerized freight |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXPORT | IMPORT | EXPORT | IMPORT | |

| Mineral fuels | 1.0% | 0.5% | 36.8% | 81.7% |

| Machinery | 10.2% | 9.5% | 12.6% | 0.8% |

| Plastics | 7.5% | 9.2% | 3.5% | 1.0% |

| Beverage | 11.0% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| Fruits | 3.3% | 6.7% | 0.8% | 1.3% |

| Articles of iron/steel | 4.1% | 4.6% | 7.0% | 0.3% |

| Cellulosic material | 6.6% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| Cast, iron/steel | 3.5% | 4.3% | 4.9% | 1.5% |

| Chemicals (miscellaneous) | 4.7% | 2.0% | 0.6% | 0.2% |

| Chemicals (organic products) | 1.4% | 7.2% | 0.3% | 0.8% |

| Ceramic | 4.9% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.1% |

| Rubber | 1.9% | 4.6% | 1.1% | 0.1% |

| Paper | 3.9% | 0.8% | 1.2% | 0.4% |

| Vehicles | 2.3% | 3.0% | 7.7% | 0.3% |

| Electrical equipment | 1.8% | 3.4% | 2.6% | 0.4% |

| Total of the 15 categories | 68.1% | 58.4% | 81.0% | 89.0% |

| Others 82 categories | 31.9% | 41.6% | 19.0% | 11.0% |

Table 2 shows the specific countries of destination for export flows and the countries of origin for import cargo, related to the Western Ligurian port system. Also in this case, there is a high degree of concentration of both import and export flows. For containerized traffic, the Italy’s top 15 trading partner countries represent approximately 68% of the export flows passing through Genoa and Savona ports and 78% of the import flows. A greater degree of concentration is observed for non-containerized traffic: 78% of export and 82% of import is generated by the first 15 countries. USA and China are the most important partners respectively for export and import containerized goods whereas Russia and USA are the top performers for non-containerized freight.

Table 2.

Containerized and non-containerized flows handled by the Italian Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority (ports of Genova and Savona), Export and Import percentage for 15 selected categories, Year 2019.

| Destination (EXPORT) | Cont. | Destination (EXPORT) | Non-cont. | Origin (IMPORT) | Cont. | Origin (IMPORT) | Non-cont. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 20.4% | Russia | 16.0% | China | 32.2% | USA | 15.0% | |||

| China | 7.9% | Turkey | 15.8% | India | 7.5% | Turkey | 10.9% | |||

| India | 4.3% | USA | 6.3% | Turkey | 6.8% | Tunisia | 9.5% | |||

| Turkey | 4.3% | Lybia | 5.8% | USA | 6.4% | Algeria | 8.3% | |||

| Emirates | 3.9% | Egypt | 5.7% | South Corea | 5.0% | Ghibraltar | 8.1% | |||

| Canada | 3.4% | Ucraina | 5.3% | Brazil | 4.3% | Lybia | 5.1% | |||

| Australia | 3.3% | Brazil | 4.4% | Egypt | 3.3% | Marocco | 4.8% | |||

| Israele | 3.0% | Algeria | 3.6% | Vietnam | 1.9% | Lybanon | 4.5% | |||

| Japan | 3.0% | Iraq | 3.3% | Thailand | 1.8% | Egypt | 4.0% | |||

| Saudi Arabia | 3.0% | Qatar | 3.3% | Taiwan | 1.7% | Albania | 3.6% | |||

| Egypt | 2.7% | Nigeria | 2.3% | South Africa | 1.6% | Brazil | 2.0% | |||

| Indonesia | 2.4% | Camerun | 2.0% | Mexico | 1.6% | Israele | 1.8% | |||

| Brazil | 2.4% | Saudi Arabia | 1.7% | Indonesia | 1.6% | Singapore | 1.5% | |||

| Vietnam | 2.3% | India | 1.6% | Pakistan | 1.5% | South Africa | 1.5% | |||

| Mexico | 2.2% | Georgia | 1.5% | Canada | 1.4% | China | 1.3% | |||

| Total of the 15 countries | 68.5% | 78.5% | 78.5% | 81.9% | ||||||

| Others 188 countries | 31.5% | 21.5% | 21.5% | 18.1% |

With respect to imports and exports to/from Italian provinces, northern Italy represents the main area of destination (Fig. 2) for flows to/from the ports of Genoa and Savona. The first five provinces generate 55% of imports and 41% of exports of containerized flows, and 88% of imports and 62% of exports of non-containerized flows. The biggest performer for containerized flows is the province of Milan with 29% of import and 16% of export, followed by Turin (9% and 5% respectively), Bergamo (6% and 9%) and Brescia (5% and 4%). As for non-containerized flows, the top performers are Pavia (39%), Savona (29%) and Genoa (14%) for import, and Genoa (32%), Milan (17%) and Turin (5%) for export.

Furthermore, 66% of exports and 57% of imports of the 12 provinces of Lombardy, which is the Italian region most affected by the pandemic, pass through the ports of Genoa and Savona.

3. Methodology

This section describes the methodology used in this study. Fig. 3 describes all the phases of the methodology, each of which is explained in detail below.

Fig. 3.

The adopted methodology.

3.1. Phase 1

The first step of the methodology regards the analysis of the Italian customs data. The Italian Customs Agency provided a detailed database2 containing the time series of the overall extra-UE import and export flows that have passed through the Italian borders from January 2012 to July 2020. The Italian customs dataset is composed of about 233 million records that collect information about the main features of the commercial transactions: the date of customs operations; the identification code of the customs office where the goods transited; the commodity category of the goods3 ; the transport mode used to reach the Italian border; the country of origin of imports or the country of destination of exports; the Italian province of import destination or the province of origin, in case of export flows; if the goods are containerized or not; and the weight and the monetary value of the goods.

The original data were then filtered and reorganized to be analyzed according to our purposes. All the trade flows passing through the Italian borders by a mode other than maritime transport have been excluded. All the customs offices identification codes have been reorganized by matching each of them, if possible, to one of the 15 Italian Port Authorities (PAs). In this way all the trade flows concerning the Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority were identified. Additionally, the over 37,000 TARIC commodity identification codes have been reclassified into 14 commodity macro-categories. The resulting dataset was composed by about 17 million records (11.6 for exports and 5.4 for imports). It was developed by collapsing the information of the original dataset with respect to the weight of the goods, aggregating the information according to the following grouping variables: (i) the year and the month of the customs operation, (ii) the port where the commodities were handled, (iii) the province of destination/origin, (iv) the extra UE Country of origin/destination, and (v) the macro category of goods. All the data provided by the Italian Customs Agency have been managed and analyzed using the statistical software R. This first analysis provided a clear picture of the goods passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona, both in import and export. The port market is highly concentrated, with the Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority acting as primary gateway for all the main flows, as described in Section 2.

3.2. Phase 2

The information collected in Phase 1 was enriched with the traffic data related to the ports of Genoa and Savona provided by the Western Ligurian Port Authority System. Moreover, in-depth interviews with some experts on the ports of Genoa and Savona were conducted with the aim of selecting the most interesting supply chains in terms of their volumes and of the impact that the pandemic had on these categories of goods.

3.3. Phase 3

On the basis of the analysis carried out in Phases 1 and 2, three supply chains were selected. They were chosen among the most important types of cargo, in terms of volume and value, passing through ports of Genova and Savona (Table 1, Table 2), and that were most affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

It should be noted that almost all extra-EU import and export flows pass through the Italian port Authorities with four cargo categories that account for more than 40% of the overall trade (Ferrari et al., 2021). Machinery, cars and food (including fruit), i.e. the categories selected for this study, are three of these cargo categories.

3.4. Phase 4

In this phase, detailed analysis of the three selected supply chains, i.e., fruit, automotive and machinery were carried out. More specifically, the following aspects were investigated: main destinations and origins of goods, breakdown of traffics into containerized and non-containerized, identification of seasonal patterns in all the time-series of flows considered and the underlying trend component, how the supply chains was affected by COVID-19 pandemic and how they reacted to this perturbation, i.e. which mitigation strategies were implemented.

3.5. Phase 5

The analysis and insights performed on the three selected supply chains were subsequently validated and enriched during a focus group that has involved some crucial stakeholders of the logistic system related to the ports of Genoa and Savona. In this phase, the main mitigation strategies adopted by the three selected supply chains were highlighted in 4.1.1, 4.2.1, 4.3.1, as a result of the insights and analysis of the previous phases of the research, including an investigation on both the academic and “grey” literature.

3.6. Phase 6

On the basis of the outcome of the previous steps, the final phase of the methodology concerned the outline of some policy indications for the post-COVID period in order to make the three selected supply more resilient.

4. Analysis of three selected supply chains: fruit, automotive and machinery

As already pointed out, fruit, automotive and machinery supply chains are associated with high volumes of goods passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona and, at the same time, were hit by COVID-19 pandemic more than other categories of goods. Below, each of the three supply chains will be analysed in detail.

4.1. The fruit supply chain

The analysis of the fruit supply chain presented hereafter is the result of the first part of the methodology (phase 1). The data collected were integrated with the traffic data from the ports of Genoa and Savona and with the interviews conducted individually with the following port experts: two Marketing Managers at the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority System, the Customs Process Manager at Nord Ovest Spa, Savona/Vado Ligure office, the Deputy Secretary General at CISCO- International Center for Container studies (phase 2 of the methodology). The analysis of Italian customs data, supported by interviews with the port experts listed above, made it possible to select the fruit supply chain over the other Italian supply chains (phase 3 of the methodology). The following is a detailed description of the supply chain for the fruit sector (phase 4 of the methodology).

Italy is the second largest producer of fruit and vegetables in the European Union, a sector representing over 25% of the gross Italian agricultural production4 . With reference to the type of product categories using the ports of Genoa and Savona5 , the “fruit” category was one of the most affected by the pandemic. In fact, the port of Savona-Vado is one of the main gateways in the Mediterranean for the import of fruit into Europe. The impact of COVID-19 can be easily assessed by analysing the 12-month moving average (dotted lines) of the graphs in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5 , that point out a clear decrease in fruit movements, mainly for export flows.

Fig. 4.

Fruit supply chain - EXPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2011–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Fig. 5.

Fruit supply chain - IMPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2011–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

In order to analyze the “Fruit” supply chain, the dataset of the Italian Customs was filtered on Chapter 08 of the TARIC code: “Edible fruit and nuts; peel of citrus fruit or melons”.

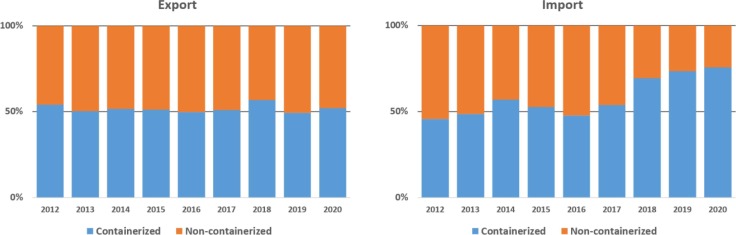

As shown in Fig. 6 , the amount of containerized cargo is the majority when referring to export flows, whereas the two types (containerized and non-containerized) are fairly balanced in import.

Fig. 6.

Fruit supply chain - Distribution of flows between containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona, EXPORT (right graph) and IMPORT (left graph), years 2011–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

A further analysis was conducted to analyse the aforementioned aggregated flows in more detail, considering:

-

•

the Italian provinces of origin and the countries of destination for export flows;

-

•

the Italian provinces of destination and the countries of origin for import flows.

It emerges that, for exports, the largest containerized volumes of fruit transiting through the Ligurian ports come from the Italian province of Cuneo and the main destination country is India (Table 3 ). As far as import flows are concerned, the most important country of origin is Costarica6 and the most significant destination is the province of Rome (Table 4 ).

Table 3.

Fruit supply chain - EXPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Origin |

Destination |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Cuneo | 49% | Verona | 45% | India | 19% | Lybia | 35% | |||

| Bolzano | 22% | Bolzano | 21% | Saudi Arabia | 17% | Egypt | 15% | |||

| Milano | 6% | Sondrio | 11% | Egypt | 15% | India | 11% | |||

| Verona | 5% | Cuneo | 7% | Brazil | 9% | Saudi Arabia | 9% | |||

| Trento | 4% | Trento | 7% | Emirates | 7% | Qatar | 6% | |||

| Total | 86% | Total | 91% | Total | 66% | Total | 75% | |||

Table 4.

Fruit supply chain - IMPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Countries of origin and Italian provinces of destination – year 2019.

|

Destination |

Origin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Roma | 23% | Milano | 51% | Costarica | 34% | Colombia | 42% | |||

| Milano | 17% | Savona | 22% | Panama | 13% | Costarica | 35% | |||

| Genova | 17% | Torino | 7% | South Africa | 8% | New Zeland | 5% | |||

| Torino | 14% | Cuneo | 5% | Colombia | 7% | Turkey | 3% | |||

| Savona | 11% | Verona | 4% | Chile | 5% | Chile | 3% | |||

| Total | 82% | Total | 90% | Total | 66% | Total | 89% | |||

The first draft of the supply chain analysis was finally presented and validated through a focus group with the same stakeholders during January-March 2021 (phase 5 of the methodology), which was essential to support the interpretation of data and to gather additional knowledge.

By analysing the moving averages from years 2012 to 2020 (Fig. 7 ), it can be observed that the COVID pandemic has strongly affected not only exports but also imports. One of the main reason of the negative impacts sustained by export flows is due to fruit seasonality: since fruit is a seasonal food, seasonal labour is required for harvesting at certain times of the year. However, travel restrictions and health measures imposed by the pandemic have created serious problems with the availability of seasonal workers and their accommodation7 .

Fig. 7.

Fruit supply chain- EXPORT and IMPORT flows for containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and moving average of order 12 (dotted lines). Top performer Italian provinces (upper graph) and Countries (lower graph) Source: Italian Customs data.

Concerning the import of exotic fruits, the total volumes exported from Costa Rica in 2020 decreased by 7% compared to 2019 and by 14% compared to 2018 against a demand that remained stable during the pandemic. This was due to the reduction of meals consumed away from home, to a greater propensity to spend on food and to purchase healthy food. The demand-offer imbalance and COVID restrictions, such as safety distances required for workers, have generated higher fruit prices for Italian consumers.

The pandemic also significantly affected the availability of refrigerated containers, essential for transporting fruit. The situation of congestion of refrigerated containers in many Asian and especially Chinese ports, due to the pandemic, in addition to determining additional costs for refrigerated transport (with prices ranging between 1,000 and 1,250 dollars per refrigerated container), has meant that many shipping companies were obliged to unload their cargo elsewhere (such as Hong Kong, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan, etc.). Containers were stuck in the unloading ports for weeks before feeder ships were able to ship these containers to their correct destinations. The containers blocked in East Asian ports have caused a shortage of reefer containers elsewhere8 .

Fig. 7 shows the trend of the most important provinces and countries (i.e., Cuneo - Costarica and Rome-India) respectively for export and import flows.

4.1.1. Mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian fruit sector during the COVID-19 pandemic

The description of mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian fruit sector is the outcome of phase 5 of the methodology. The aim of the focus groups activity was not only to validate the analysis based on data collection and literature review, but also to identify the mitigation strategies adopted by the sector through the direct experience of operators. Due to the recent disruptive impact of the pandemic, most of the available information on response strategies has not yet been formalised through data collection and literature.

During the pandemic, the Italian companies that work in the fruit sector have shown a strong resilience. Specifically, during the lockdown, these companies continued to work by adopting the necessary measures to avoid contagion, despite the fact that 70% of them experienced organizational complexity, 55% an extension of time, 60% a lower working efficiency and 65 % an increase in costs (Osservatorio Nomisma, 2021). Another action taken by the fruit sector in order to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic was to push fruit consumption towards the Italian national market. This was also due to the fact that the pandemic determined a marked reduction of maritime services (phenomenon of blank sailings) which has greatly hampered Italian exports. In fact, in the first seven months of 2020, the Italian consumption of fruit reached higher levels than the pre-COVID period. According to a survey conducted by Bva Doxa Italian Food Union, which involved 11.5 million Italians, during the pandemic the Italian consumption of fruits increased from 42 to 60%9 . This means that, in addition to COVID effects, a decrease in export flows is partly due to the fact that a part of the fruit was destined to the National market (instead to extra-EU countries). In the literature it is also noted that, during the lockdown period, the mitigation strategies adopted by export companies have focused, among other things, on the sale of export-oriented commodities on the domestic market (Lin and Zhang, 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought substantial changes to the Italian fruit market. Although retail purchases have remained fairly stable, consumer habits have changed and the consequences will also affect post-Covid. In particular, Italians are expected to give more and more importance to elements such as Italian origin, seasonality and freshness of products (Osservatorio Nomisma, 2021).

4.2. The automotive supply chain

The analysis of the automotive supply chain is mainly the result of phase 1 of the methodology, i.e., the analysis of the Italian customs data. The customs data were then enriched with interviews, focused on the automotive supply chain, conducted individually with the following port experts: two Marketing Managers at the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority System, the Senior Sales Manager at Marittima Spedizioni LTD of Savona Terminal Auto, the Customs Process Manager at Nord Ovest Spa, Savona/Vado Ligure office, the Deputy Secretary General at CISCO- International Center for Container studies (phase 2 of the methodology). The selection of the automotive supply chain was made on the basis of the analysis of Italian customs data, supported by interviews with port experts (phase 3 of the methodology). Below, a detailed description of the automotive supply chain is provided (phase 4 of the methodology). All analyses were validated through a focus group with the same above mentioned stakeholders during the period January-March 2021 (phase 5 of the methodology).

In the first seven months of 2020, the main Italian exporting sectors recorded very negative changes. In particular, the machinery and automotive sectors (especially cars), which had already shown signs of weakness in 201910 , suffered a strong backlash.

In the last years, the Italian automotive sector has generated a turnover of around 50 billion euros (around 100 billion if indirect activities are also considered) and its competitiveness is higher than that of the manufacturing sector as a whole. The Italian automotive supply chain is positioned in the segments with the highest added value thanks not only to the excellence in the production of high-end and commercial vehicles, but also by virtue of production specializations that characterize in particular the component manufacturing districts. Among European countries, Italy has suffered the impact of the crisis more intensely. The full lockdown that began on March 11, 2020 resulted in a drop in monthly sales of more than 85%, which reached nearly 98% in April. In two months the market recorded an 18% drop in the total number of cars sold in all of 2019. Employment in the sector was already contracting before March 2020, and the pandemic is likely to affect around 70,000 workers. Small and medium-sized enterprises, which largely comprise the sector's supply chain, in addition to the commercial network, are the most affected11 .

In order to analyze the Italian “Automotive” supply chain trend in the COVID-19 period, the dataset of the Italian Customs was filtered on Chapter 87 of the TARIC code: “Vehicles other than railway or tramway rolling stock, and parts and accessories thereof”. A subsequent in-depth study on “Cars” supply chain concerns the 4-digits TARIC code: “Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of persons (other than those of heading 8702), including station wagons and racing cars”.

Unlike the fruit category, the automotive flows passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona are indifferently containerized or not, with a net increase in containerized goods for import starting from 2017 (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

Automotive supply chain - Distribution of flows between containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona, EXPORT (right graph) and IMPORT (left graph), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

However, the main means of transport for cars is non-containerized one: they are mainly handled on RO-RO ships or car carriers (Fig. 9 ).

Fig. 9.

Car supply chain - Distribution of flows between containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona, EXPORT (right graph) and IMPORT (left graph), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Fig. 10 shows the trend of export flows (solid lines) for the automotive (left side of Fig. 10) and aar (right side of Fig. 10) supply chains, together with the relative 12-month moving averages (dashed lines), from 2011 until July 2020. The impact of the pandemic is evident in both cases, with a much worse and unstable trend for the car sector.

Fig. 10.

Automotive (left side) and Car (right side) supply chains - EXPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Similarly, Fig. 11 shows the trend in imported goods for both the automotive and car segments, and the related 12-month moving averages (dashed lines), in the same years. Again, COVID-19 significantly impacted these cargo flows.

Fig. 11.

Automotive (left side) and Cars (right side) supply chain - IMPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Analysing the main Italian provinces of origin and destination (Table 5, Table 6 ), it is clear that the Piedmont region represents the leading area for this type of goods, both automotive and car. 45% of the vehicles are produced in the provinces of Asti and Turin (Table 5) and 35% are imported into the provinces of Turin and Novara (Table 6).

Table 5.

Automotive supply chain - EXPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Origin |

Destination |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Asti | 29% | Torino | 18% | USA | 27% | Lybia | 13% | |||

| Torino | 16% | Cuneo | 8% | Brazil | 19% | Nigeria | 10% | |||

| Bologna | 12% | Piacenza | 7% | Mexico | 10% | Tunisia | 8% | |||

| Trento | 8% | Brescia | 5% | Turkey | 6% | USA | 7% | |||

| Bergamo | 6% | Milano | 4% | China | 3% | China | 7% | |||

| Total | 70% | Total | 42% | Total | 65% | Total | 44% | |||

Table 6.

Automotive supply chain - IMPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Destination |

Origin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Torino | 28% | Torino | 30% | China | 59% | Japan | 24% | |||

| Milano | 14% | Bergamo | 13% | India | 9% | China | 17% | |||

| Brescia | 10% | Piacenza | 10% | Japan | 8% | Turkey | 15% | |||

| Piacenza | 10% | Verona | 9% | Taiwan | 7% | Tunisia | 11% | |||

| Novara | 7% | Milano | 8% | Turkey | 5% | Serbia | 10% | |||

| Total | 69% | Total | 71% | Total | 88% | Total | 78% | |||

The USA and China are respectively the main countries of destination and origin for the containerized automotive category (Table 5, Table 6). Since these two countries were seriously affected by the pandemic - albeit in slightly different periods: USA at the end of March 2020 and China at the beginning of 2020 -, the negative impact on the Italian sector was significant.

Regarding car supply chain, the main provinces of origin are located in the North-East of Italy and the main country of destination is Nigeria, with 46% of total traffic (Table 7 ). A different picture can be depicted for the import flow of containerized cars: China and the USA are the main countries of origin, Fig. 12 shows the trend of the top performer provinces (that is Turin for both import and export) and countries (China and Serbia, respectively for export and import flows) (Table 8 ).

Table 7.

Cars supply chain - EXPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Origin |

Destination |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Modena | 9% | Torino | 68% | Nigeria | 46% | China | 31% | |||

| Padova | 8% | Frosinone | 3% | Ghana | 9% | USA | 16% | |||

| Verona | 6% | Potenza | 3% | Senegal | 8% | Japan | 8% | |||

| Brescia | 6% | Bergamo | 2% | Togo | 7% | Nigeria | 6% | |||

| Milano | 5% | Milano | 2% | Camerun | 7% | South Korea | 5% | |||

| Total | 35% | Total | 78% | Total | 78% | Total | 65% | |||

Fig. 12.

Cars - EXPORT and IMPORT flows for containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines). Top performer Italian provinces (upper graph) and Countries (lower graph) Source: Italian Customs data.

Table 8.

Cars supply chain - IMPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Destination |

Origin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Milano | 18% | Torino | 91% | China | 25% | Serbia | 45% | |||

| Torino | 13% | Como | 3% | USA | 21% | Turkey | 42% | |||

| Monza | 10% | Savona | 2% | Taiwan | 18% | Taiwan | 8% | |||

| Varese | 9% | Roma | 1% | Emirates | 5% | China | 2% | |||

| Genova | 7% | Monza | 1% | Vietnam | 4% | USA | 2% | |||

| Total | 56% | Total | 97% | Total | 72% | Total | 98% | |||

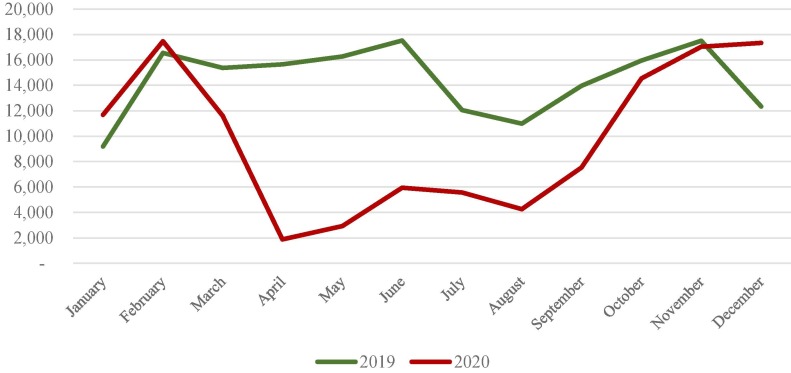

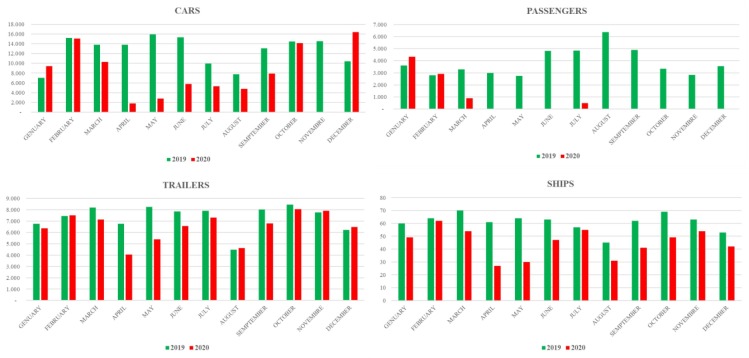

Due to its geographical location with respect to Piedmont, which is the most important Italian region for this cargo category, the port of Savona is the most used for this type of cargo. Savona Terminal Auto, located in the port of Savona, is one of the largest RO-RO terminal of the Western Ligurian Sea Port Authority and plays a key role for the automotive sector from/to Northern Italy. The impact of the pandemic on the terminal’s performances was devastating (Fig. 13 ): from May 2020 to mid-May 2020 the terminal almost stopped its operations linked to the movement of cars. The closure of many companies, including car dealerships, has caused severe congestion at the terminal, risking its paralysis. Immediately after the start of the first Italian lockdown (March 2020), the cars began not to be collected by the customers of the terminal, with the consequence for the terminal having to suspend most of its maritime services. The revenues from the demurrage of the cars certainly did not compensate for the losses due to the decrease in handling. Another reason for the reduction in car flows is due to the energy transition that is still underway and which is affecting the segment of private motorized cars.

Fig. 13.

Number of cars handled by Savona Terminal Auto, years 2019 and 2020 Source: Western Ligurian Port Authority System.

Fig. 14 shows the trend of cars, passengers, trailers and ships handled by Savona Terminal Auto compared to all the months of 2019 and 2020. It can be noted that, starting from March 2020 - that is when Italy entered the first lockdown -, for the reasons already mentioned, the number of cars handled by the terminal has started to decrease significantly. Only in October 2020 the flows of cars returned to the level of volumes recorded in 2019. The negative impact of the pandemic was not so strong for the trailer category. This is due to the fact that the trailers transport goods that also include primary goods, such as food and drugs, which could not be stopped during the pandemic. As for trailers, another impact of COVID-19 was the reduction of driver travel due to the risk of infection. In fact, unaccompanied transport has increased compared to accompanied transport.

Fig. 14.

Number of cars, passengers, trailers and ships handled by Savona Terminal Auto, years 2019 and 2020 Source: Savona Terminal Auto, port of Savona, Italy.

Fig. 14 indicates that, starting from April 2020, the flows of passengers have completely stopped (apart from a little flow managed in the month of July 2020). The number of ships handled also suffered a negative impact from March 2020, with a peak reached in April and May 2020.

4.2.1. Mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian automotive sector during the COVID-19 pandemic

In this chapter, the description of the mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian automotive sector (phase 5 of the methodology) are presented.

In the two-year period 2018–2019, the Italian automotive sector contracted by more than 4%, attributable to the crisis in diesel engines, the gradual emergence of the hybrid/electric vehicle segment and the new consumption models focused on cars as a service and no longer as an “object of desire”. The crisis induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the prolonged closure of factories in the main producing countries starting from March 2020, is to be placed in a phase in which significant transformations were already underway in the global industrial supply chain. These transformations were mainly related to the huge investments for the development of both traditional engines, but with less emissions, and electric batteries.

During the COVID-19 outbreak, the automotive sector perceived that the best strategies to mitigate the risks associated with COVID-19 were to develop localized sources of supply and use advanced industry 4.0. This industry has also paid cloese attention to Big Data Analytics (BDA), which can provide real-time information on supply chain activities, and to cooperation, which can improve transactions among supply chain stakeholders (Belhadi et al, 2021).

The pandemic has accelerated an already underway process in which car manufacturers are investing more and more in electric mobility. The pandemic has made public opinion and consumers more sensitive to issues of health and environmental sustainability. Compared to the pre-COVID period, Italian consumer interest in hybrid and electric vehicles has grown from 58% to 71% (2020, Deloitte Global Automotive Consumer Study) confirming the market potential driven by high-income demand.

4.3. The machinery supply chain

The description of the machinery supply chain (phase 4), similarly to the previous case studies, is the result of the analysis of the Italian customs and port data, and of the interviews conducted with the following port experts: two Marketing Managers at the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority System, the Customs Process Manager at Nord Ovest Spa, Savona/Vado Ligure office, the Deputy Secretary General at CISCO- International Center for Container studies (phases 2 and 3).

The results were then validated through a focus group with the same stakeholders during January-March 2021 (phase 5).

The Italian production of machine tools, robots and automation is characterized by the presence of about 400 companies and 32,000 employees for a turnover that exceeds 8 billion euros (including in the calculation, in addition to the production of machines, the production of parts, tools and numerical controls).

In order to analyze the “Machinery” supply chain, the dataset of the Italian Customs was filtered on Chapter 84 of the TARIC code: “Nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery and mechanical appliances; parts thereof”.

This crucial supply chain is mainly managed in container, both for imports and exports, as illustrated in Fig. 15 .

Fig. 15.

Machinery supply chain - Distribution of flows between containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona, EXPORT (right graph) and IMPORT (left graph), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

As highlighted by the graphs in Fig. 16, Fig. 17 , the pandemic has profoundly compromised the results of the Italian industry in the machinery sector, both in import and export (according to the Italian Institute of Statistics -ISTAT, in 2020 this segment suffered a contraction in exports equal to −29.9%). This negative result was determined both by the drop in deliveries of Italian producers on the domestic market (which fell by 28.2% to 2,090 million euros), and by the negative trend in exports (which fell by 20% to 2,880 million euros).12 Sales in the United States, the first country of destination for Made in Italy (Table 9 ), fell to 229 million euros (-21.4%), followed by Germany (-31.2%), China (-28.2%), France (-34.3%) and Poland (-30.8%). The sharp reduction in domestic consumption of machine tools led to an increase in the export-to-production ratio, which went from 55.3% in 2019 to 57.9% in 2020.

Fig. 16.

Machinery supply chain - EXPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Fig. 17.

Machinery supply chain - IMPORT flows for containerized and non-containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and 12-month moving average (dotted lines), years 2012–2020 Source: Italian Customs data.

Table 9.

Machinery supply chain - EXPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Origin |

Destination |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Milano | 18% | Milano | 12% | USA | 28% | USA | 17% | |||

| Bergamo | 8% | Torino | 9% | China | 7% | China | 9% | |||

| Brescia | 7% | R. Emilia | 8% | Brazil | 6% | India | 6% | |||

| Torino | 5% | Brescia | 6% | Egypt | 5% | Tunisia | 4% | |||

| Asti | 4% | Modena | 6% | Saudi Arabia | 5% | Australia | 4% | |||

| Total | 42% | Total | 41% | Total | 50% | Total | 40% | |||

The health emergency has made its effects felt even more incisively on the domestic front; in 2020, the consumption of machine tools, robots and automation in Italy decreased by 30.3% to 3,385 million euros, penalizing both the deliveries of Italian manufacturers and imports, which fell by 33.4% to 1,295 million.

Analysing more in detail the flows of machinery transited through the ports of Genoa and Savona in 2019 (Table 9, Table 10 ), it emerges that the most of the export flows originated in the Italian provinces of Milan, Bergamo and Brescia, which were among the most hit Italian provinces by the pandemic - as shown in Fig. 18 - and were destined to the United States of America, whose first lockdown was ordered by the end of March 2020.

Table 10.

Machinery supply chain - IMPORT containerized flows through the ports of Genoa and Savona: Italian provinces of origin and Countries of destination – year 2019.

|

Destination |

Origin |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | cont. | Province | non-cont. | Country | cont. | Country | non-cont. | |||

| Milano | 38% | Torino | 24% | China | 58% | China | 50% | |||

| Torino | 25% | Milano | 20% | Brazil | 7% | India | 12% | |||

| Brescia | 5% | Parma | 8% | Japan | 7% | South Korea | 10% | |||

| Varese | 4% | Bergamo | 6% | Turkey | 6% | Malaysia | 5% | |||

| Monza | 3% | Monza | 4% | India | 5% | Tunisia | 5% | |||

| Total | 75% | Total | 61% | Total | 82% | Total | 82% | |||

Fig. 18.

Cumulative incidence rates (per 100,000 inhabitants) of COVID-19 cases diagnosed in Italy and excess total mortality compared to the average of 2015–2019 deaths (percentage values) in the period February-May 2020 Source: ISTAT (Italian statistical institute) data.

Another important destination for Italian machinery in 2019 was Brazil, which accounted for 6% of export in 2019 (Table 9), one of the countries hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. Some Italian companies located in the province of Bergamo import parts of machinery from Germany and China and then produce laser machines for cutting stone that are then exported to Brazil. For these companies the pandemic crisis in Brazil, combined with the local pandemic situation, has had a very negative effect.

Regarding import flows, over 50% of the machinery comes from China and the main destinations are the province of Milan (38%), followed by that of Turin (25%). Again, China and Milan, have been strongly affected by the pandemic.

Fig. 19 further highlights the negative trends of the top performer provinces and countries, for both import and export flows regarding the Italian machinery category.

Fig. 19.

Machinery - EXPORT and IMPORT flows for containerized cargo passing through the ports of Genoa and Savona: absolute flows in tons (continuous lines) and moving average of order 12 (dotted lines). Top performer Italian provinces (upper graph) and Countries (lower graph) Source: Italian Customs data.

4.3.1. Mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian machinery sector during the COVID-19 pandemic

The mitigation strategies adopted by the Italian machinery sector are described in the following (phase 5 of the methodology).

The industrial machinery sector is a set of heterogeneous subsectors. The four main sectors are: high-tech goods; electrical machinery and equipment; mechanical engineering; repair and installation of machinery. Mechanical engineering is the most relevant sector due to its fifth position in the world in terms of turnover, second in Europe only to Germany. In terms of exports, industrial machinery represents 26% of the entire national export of goods. The export of mechanical engineering products is equivalent to 18% of all Italian export.

With respect to the machinery industry, at least three sector-specific resilience factors can be identified. The first is the average size of the company, on average higher than the national average. The second is productivity. A third is represented by the presence of supply chains and production districts in different parts of the country that allow companies in the sector to integrate as a supply chain and have access to shared resources (skills, purchasing centers, innovation, etc.). These resilience factors have allowed the shortening of the Italian machinery supply chain in the most critical phase of the lockdown (Camerano et al, 2020).

5. Policy indications for the post COVID-19 period

The final phase of this research regards the outline of some indications to make the three selected supply chains more resilient (phase 6 of the methodology). More specifically, on the basis of the analysis carried out in the previous sections, some policy indications for the post-COVID-19 period (the so-called new normal) can be outlined in relation to the fruit, automotive and machinery supply chains that pass through the Italian ports of Genoa and Savona. The final goal is to make supply chains more resilient and able to successfully deal with the unexpected events that may compromise supply and demand for goods.

5.1. The fruit supply chain

In the fruit sector, the best or worst seasonality determines the supply of a given geographical area. The pandemic has affected both the demand and supply of the fruit segment. As far as demand is concerned, an increase in the Italian consumption of fruits has been recorded. On the supply side, two main trends should be highlighted: COVID-19 wiped out the entire fruit crop due to seasonal labor shortage, resulting in huge losses for some producers and higher prices for end consumers. Moreover, the tariffs of sea freight have tripled, in particular those relating to refrigerated containers, which are used to transport fruit. There has been a gradual increase in the demand for containers ((a physiological phenomenon for years due to the growing trend of maritime transport), accompanied by a phenomenon of global (and strategic?) repositioning of empty containers.

This allowed shipping companies to significantly increase sea freight rates, which led to higher prices for importers/exporters and, consequently, also for logistics operators and end customers. These dynamics show that the ongoing race for naval gigantism does not automatically lead to a profit for stakeholders other than those of the shipping companies (including end customers), fueling the current debate on the actual benefits of naval gigantism for the community.

The increase in sea freight rates is particularly penalizing for those product categories, such as fruit, whose unit value is low, and which are also perishable products. For these categories, in fact, the transport cost strongly affects the total price of the asset. The combined increase in these cost items (sea transport and fruit prices) is strongly influencing some fruit supply chains, such as that relating to kiwi exported from Italy to the east coast of the United States. Before the pandemic, Italian fruit was preferred to Californian fruit due to the very low freight rates from Italy to the east coast compared to high land transport from the west to the east coast of the United States. If freight rates remain at current levels, fruit from Italy could lose its attractiveness on some foreign markets, with the consequence that Italian producers will see their profits decrease. This could lead to a downsizing of some supply chains, pushing producers to try to sell more on local markets rather than on foreign markets. Obviously this can only be a possibility when there is a potential demand to be intercepted. Another aspect to consider, in fact, is that the impacts caused by the pandemic could push countries to invest more in the local production of some categories of goods considered primary, such as fruit (similarly to what happened for Italian personal protective equipment such as masks, whose supply depended almost entirely from abroad before the pandemic). For example, countries like India, which is one of the main fruit importers from Italy, could consider producing locally the fruit that has hitherto been imported from Italy.

According to the Italian Observatory Nomisma (Osservatorio Nomisma, 2021), the main strategies that Italian companies operating in the fruit sector will undertake in the post-Covid scenario, in particular in the next 1–2 years, are the expansion and diversification of foreign markets together with the strengthening of the local market (actions that 38% of companies will implement). This policy is consistent with the mitigation actions taken internationally, i.e. the sale of export-oriented commodities on the domestic market (Lin and Zhang, 2020). Regarding other mitigation strategies, the ecological transition in production systems and packaging was reported by 33% of companies, the packaging of fresh product by 31% and the digital transition of industry 4.0 by 23%. Some other strategies are linked to the strengthening of goods traceability systems (13%), to the activation or strengthening of online sales, and to the increase in advertising investments (5%).

Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has made it clear how fruit supply chain is substantially dependent on the workforce employed and how its availability is more easily guaranteed when economic conditions are better. This could help push the social partners also to develop adequate contractual instruments to successfully and foresight address this possible criticality (Rete rurale nazionale, 2021).

The literature review proposed by Cardoso et al. (Cardoso et al., 2021) stresses that the main categories of policies to mitigate the negative impacts of epidemics and pandemics on food supply chains are: evaluation, monitoring and adjustment of workforce; automation of activities; implementation of health and safety protocols; availability of government financial assistance for companies; definition of stability and business continuity plans; foster cooperation and collaboration; increase the transparency of the food trade; adoption of decision support tools; use of online infrastructures and communication technologies; implementation of contingency plans such as increasing inventory levels.

5.2. The automotive supply chain

The main lines of action aimed at mitigating the negative effects of the pandemic in the new normal for the automotive sector concern: i) the adoption of short-term policies aimed at business continuity; ii) rethinking and renewing the Italian automotive supply chain; iii) the development of sustainable mobility and public transport; iv) research, university and training.

Further and more specific policy indications concern the introduction of digital technologies for the supply chain, in particular Industry 4.0, to improve resilience and mitigate the risks of the supply chain (AS B. and Ramanathan U., 2021, Spieske and Birkel, 2021). On the demand side, government interventions aimed at relaunching the renewal of the vehicle fleet (the Italian one is the oldest in Europe) are among the most likely intervention measures for the future, especially if aimed at low environmental impact and zero emissions cars (PWC Strategy &, 2020).

The most resilient to the COVID-19 crisis seems to be the Japanese manufacturers Toyota and Honda13 , which have already oriented their production towards hybrid injection systems in addition to traditional combustion systems. On the other hand, European carmakers such as Volkswagen and Renault, which began the complex transition process shortly before the pandemic, are the ones suffering the most from the crisis.

In general, therefore, COVID-19 seems to have only had a temporary effect on the decrease in automotive flows, which will return to rise again. However, what seems evident is that the pandemic has accelerated the dynamics of the energy transition for the automotive sector.

5.3. The machinery supply chain

The main measures that the Italian machinery sector will have to implement in the new normal period concern: i) increase financial support to companies; ii) increase digital investments (including industry 4.0); iii) greater transparency in supply chain management and adoption of resilient and nearshoring business models; iv) the development of partnerships to favor the growth of the sector. This includes partnerships with the most strategic suppliers through shared production plans, creation of purchasing groups, definition of strategic inventories and integration of the supply chain. Additional potential resilience strategies are vertical integration, horizontal integration and mergers and acquisitions (Camerano et al., 2020).

Another aspect to consider is that the Italian machinery sector is currently fragmented into many small-sized producers. Dimensional growth represents a key issue for the development of this sector and for maintaining its competitiveness with foreign competitors. Therefore, the consolidation of the Italian machinery supply chain, including mergers between companies, is considered another successful resilience strategy for the post-Covid. Furthermore, a national industrial policy that takes into account aspects of product and process innovation would certainly help.

Future policies could also be supported by international experience. Scholars (Handfield et al., 2020) suggest four main topics to be addressed in the future. These themes include global procurement, a combined effect of “demand and supply shortage”, strengthening local production systems and developing risk recovery strategies. Based on empirical studies, the machinery industry could see a redirection of supply chains: less cost-driven and more sensitively influenced by multiple factors such as sustainability, low emissions and better risk recovery strategies.

6. Conclusions

All global supply chains have suffered a substantial impact from the pandemic, especially those related to the manufacturing sectors. In this paper three significant supply chains which pass through the Italian ports of Genoa and Savona, were analyzed in detail to investigate the effects of COVID-19 on their functioning and their level of resilience. The analyses were performed using customs and ports data, and carrying out interviews and focus groups with port experts. The outcomes showed that, although the COVID-19 pandemic strongly affected these supply chains, each of them reacted with varying levels of resilience by implementing mitigation strategies that allowed them to continue to function.

The research clearly shows that the effects on the demand and supply of the logistic chains, and therefore the possible mitigation actions, are closely linked to their characteristics (Loske, 2020).

For the new normal, some general mitigation factors can be identified. The use of digital technologies and Big Data Analytics is crucial to increase supply chain resilience, thanks to their ability of increasing speed, favoring the connection between the stakeholders, and providing real-time information. These factors are essential to quickly react to any perturbation to planned events. Favoring cooperation between stakeholders is also essential to increase supply chain resilience. The use of backup suppliers and increase in safety stock may represent other possible mitigation strategies to face unexpected events which negatively affect the procurement of goods.

Future research will further investigate the effects of the pandemic using more updated data, and to analyze whether COVID-19 has accelerated the trend of naval gigantism and has favored a phenomenon of concentration of traffic flows on some Italian ports.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mr. Silvio Ferrando and Mr. Leonardo Picozzi (Marketing Managers at the Italian Western Ligurian Port Authority System), Mrs. Milena Guarino (Senior Sales at Marittima Spedizioni LTD, Savona Terminal Auto), Mr. Davide Battaglia (Customs Process Manager at Nord Ovest Spa, Savona/Vado Ligure office) and Mr. Massimiliano Giglio (Deputy Secretary General at CISCO- International Center for Container studies) for their useful contribution in this research.

Footnotes

Rail freight transport initially showed a less pronounced decline, recording a slight overall increase in terms of train-km up to 8 March, but then progressively lost traffic quota. In March recorded a drop of about 12%, which however progressively increased to a drop of 26% in the period 9 March − 22 April. A more detailed analysis of rail transport shows that intermodal transport is more resilient, with an estimated drop of 16% over the previous year in the same period from 9 March to 22 April (Cascetta et al. 2020).

Database ADM. Data extraction by Statistics and Open Data Office of the Italian Custom Agency.

The classification of goods is based on the TARIC code of the Integrated Tariff of the European Communities at chapter level corresponding to the first two digits of the entire code.

https://www.italiafruit.net/DettaglioNews/53143/in-primo-piano/tutti-i-numeri-dellortofrutta-europea.

The quantity of fruit in transit in the ports of Genoa and Savona from / to non-EU countries represents about the 45% of the total amount of Italian flows.

Rapporti di previsione - Centro Studi Confindustria “Un cambio di paradigma per l’economia italiana: gli scenari di politica economica”, Autumn 2020.

CdP, EY, Louis Business School, “L’economia italiana, dalla crisi alla ricostruzione. Scenario, impatti, prospettive”, June 2020, https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/it_it/generic/generic-content/ey-settore-automotive-e-COVID-19.pdf.

References

- AS, B., Ramanathan, U., 2021. The role of digital technologies in supply chain resilience for emerging markets’ automotive sector. Supply Chain Manag., 26(6), 654-671. 10.1108/SCM-07-2020-0342.

- Barman A., Das R., De P.K. Impact of COVID-19 in food supply chain: Disruptions and recovery strategy. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.crbeha.2021.100017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhadi A., Kamble S., Jabbour C.J.C., Gunasekaran A., Ndubisi N.O., Venkatesh M. Manufacturing and service supply chain resilience to the COVID-19 outbreak: Lessons learned from the automobile and airline industries. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;163:120447. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camerano S., Carriero A., Dell’Aquila C., Valdes C., Rocco M., Mignani M., Lecis F., Chiattelli C., Peruffo E. Gruppo Cassa Depositi e Prestiti; EY, Luiss Business School: 2020. Settore Macchinari Industriali e COVID-19 L’economia italiana, dalla crisi alla ricostruzione Scenario, impatti, prospettive (2020) [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso B., Cunha L., Leiras A., Gonçalves P., Yoshizaki H., de Brito Junior I., Pedroso F. Causal Impacts of Epidemics and Pandemics on Food Supply Chains: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2021;13(17):9799. [Google Scholar]

- Cascetta, E., 2021. Logistica e trasporti per la ripresa economica, Shipping, Forwarding&Logistics meet Industry Conference, Milan, March 2021.

- Cascetta, E., Marzano, V., Aponte, D., Arena, M., 2020. Alcune considerazioni sugli impatti dell’emergenza COVID-19 per il trasporto merci e la logistica in Italia.

- Coldiretti, 2020. Coronavirus: Fuga dei braccianti stranieri, sos made in Italy. February 2020. Available online https://www.coldiretti.it/economia/coronavirus-fuga-dei-br accianti-stranieri-sos-made-in-italy. (Accessed 10 March 2021).

- Coluccia B., Agnusdei G.P., Miglietta P.P., De Leo F. Effects of COVID-19 on the Italian agri-food supply and value chains. Food Control. 2021;123:107839. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deandreis, M., 2021. Gli scenari marittimi del Mediterraneo e le nuove sfide del COVID-19, Shipping, Forwarding&Logistics meet Industry Conference, Milan, March 2021.

- Deloitte Global Automotive Consumer Study. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- El Baz, Ruel, S., 2021. Can supply chain risk management practices mitigate the disruption impacts on supply chains’ resilience and robustness? Evidence from an empirical survey in a COVID-19 outbreak era. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 233, 107972, ISSN 0925-5273, 10.1016/j.ijpe.2020.107972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Elliott D., Bonsignori C. The influence of customs capabilities and express delivery on trade flows. J. Air Transp. Manage. 2019;74:54–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jairtraman.2018.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Faour-Klingbeil D., Osaili T.M., Al-Nabulsi A.A., Jemni M., Todd E.C. The public perception of food and non-food related risks of infection and trust in the risk communication during COVID-19 crisis: A study on selected countries from the arab region. Food Control. 2021;121:107617. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2020.107617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando, S., 2021. La logistica italiana: un futuro da schiavi? Manifattura e logistica nel Nord Italia: analisi dei comportamenti logistici e commerciali prevalenti e dei conseguenti rischi sistemici per i servizi legati al trasporto internazionale, Shipping, Forwarding&Logistics meet Industry Conference, Milan, March 2021.

- Ferrari, C., Persico, L., Tei, A., 2021. Italian intermodal logistics corridors: the cargo point of view, SIGA2 2021 Conference, Antwerp, May 5th–7th.

- Gereffi G. What does the COVID-19 pandemic teach us about global value chains? The case of medical supplies. J. Int. Bus Policy. 2020;3(3):287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Gray R.S. Agriculture, transportation, and the COVID-19 crisis. Canad. J. Agric. Econ./Revue canadienne d’agroeconomie. 2020;68(2):239–243. [Google Scholar]

- Gruszczynski L. The COVID-19 pandemic and international trade: Temporary turbulence or paradigm shift? Eur. J. Risk Regul. 2020;11(2):337–342. doi: 10.1017/err.2020.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Handfield, R.B., Graham, G., Burns, L., 2020. Corona virus, tariffs, trade wars and supply chain evolutionary design. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manage. 40(10), 1649–1660.

- Horner R., Alford M. In: Handbook on global value chains. Ponte S., Gereffi G., Raj-Reichert G., editors. Edward Elgar; Cheltenham, UK: 2019. The roles of the state in global value chains; pp. 555–569. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini S., Ivanov D., Dolgui A. Review of quantitative methods for supply chain resilience analysis. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2019;125:285–307. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D. Springer; New York: 2018. Structural Dynamics and Resilience in Supply Chain Risk Management. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: a simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Transport. Res. E Logist. Transport. Rev. 2020;136:101922. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D., Dolgui A. Low-Certainty-Need (LCN) Supply Chains: A new perspective in managing disruption risks and resilience. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019;57(15-16):5119–5136. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov D., Dolgui A. Viability of intertwined supply networks: extending the supply chain resilience angles towards survivability. A position paper motivated by COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020;58(10):2904–2915. [Google Scholar]

- Karmaker C.L., Ahmed T., Ahmed S., Ali S.M., Moktadir M.A., Kabir G. Improving supply chain sustainability in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in an emerging economy: Exploring drivers using an integrated model. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021;26:411–427. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B., Zhang Y.Y. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on agricultural exports. J. Integr. Agric. 2020;19(12):2937–2945. doi: 10.1016/S2095-3119(20)63430-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loske D. The impact of COVID-19 on transport volume and freight capacity dynamics: An empirical analysis in German food retail logistics. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020;6 doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair A., Vidal J.M. Supply network topology and robustness against disruptions – an investigation using a multi-agent model. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011;49(5):1391–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi S., Sarkis J., Hervani A.A., Helms M.M. Redesigning Supply Chains using Blockchain-Enabled Circular Economy and COVID-19 Experiences. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021;27:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.spc.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos K., Punia S., Schäfers A., Tsinopoulos C., Vasilakis C. Forecasting and planning during a pandemic: COVID-19 growth rates, supply chain disruptions, and governmental decisions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021;290(1):99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary, L., 2020. The modern supply chain is snapping. The Atlantic, March 26.

- O’Neil, S.K., 2020. How to pandemic-proof globalization: Redundancy, not re-shoring, is the key to supply-chain security. Foreign Affairs, April 1. Available at: https://www. foreignaffairs.com/articles/2020-04-01/how-pandemic-proofglobalization.