Abstract

Introduction

Earlier application of oral androgen receptor-axis-targeted therapies in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) has established improvements in overall survival, as compared to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) alone. Recently, the use of apalutamide plus ADT has demonstrated improvement in mCSPC-related mortality vs. ADT alone, with an acceptable toxicity profile. However, the cost-effectiveness of this therapeutic option remains unknown.

Methods

We used a state-transition model with probabilistic analysis to compare apalutamide plus ADT, as compared to ADT alone, for mCSPC patients over a time horizon of 20 years. Primary outcomes included expected life-years (LY), quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), lifetime cost (2020 Canadian dollars), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Parameter and model uncertainties were assessed through scenario analyses. Health outcomes and cost were discounted at 1.5%, as per Canadian guidelines.

Results

For the base-case analysis, expected LY for ADT and apalutamide plus ADT were 4.11 and 5.56, respectively (incremental LY 1.45). Expected QALYs were 3.51 for ADT and 4.84 for apalutamide plus ADT (incremental QALYs 1.33); expected lifetime cost was $36 582 and $255 633, respectively (incremental cost $219 051). ICER for apalutamide plus ADT, as compared to ADT alone, was $164 700/QALY. Through scenario analysis, price reductions ≥50% were required for apalutamide in combination with ADT to be considered cost-effective, at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $100 000/QALY.

Conclusions

Apalutamide plus ADT is unlikely to be cost-effective from the Canadian healthcare perspective unless there are substantial reductions in the price of apalutamide treatment.

Introduction

Since 2004, there has been a rapid expansion in life-prolonging systemic treatment options for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC).1 More recently, these systemic treatments, including docetaxel, abiraterone, and enzalutamide, have been evaluated earlier in the disease course, in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC), demonstrating significant improvements in both progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS).2–6 However, the toxicity profiles of these agents raise some concerns about the generalizability of these treatments.6–8

The androgen receptor-axis-targeted therapy (ARAT), apalutamide, is the fourth agent to demonstrate efficacy for patients with mCSPC. The phase 3 TITAN trial compared the addition of apalutamide to ADT vs. ADT alone, demonstrating a significant improvement in both radiographic PFS (hazard ratio [HR] 0.48, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–0.60), p<0.001) and OS (HR 0.65, 95% CI 0.53–0.79, p<0.0001).9,10 This benefit was seen irrespective of volume of metastatic burden, in keeping with the volume-independent benefits demonstrated with abiraterone and enzalutamide.2,3,6 In addition, a tolerable toxicity profile was also demonstrated in the TITAN trial, with grade 3/4 adverse events (AE) occurring in 49% of patients, as compared to 42% in those treated with ADT alone.9,10

With improved efficacy and a tolerable toxicity profile, the use of apalutamide may be the preferred systemic therapy for patients with mCSPC. However, monthly costs for apalutamide are estimated at upwards of $3000 per patient, necessitating the demonstration of cost-effectiveness prior to recommendation. The objective of this study was to conduct a cost-utility analysis of apalutamide in combination with ADT (apalutamide+ADT), in comparison to ADT alone, from the perspective of the publicly funded Canadian healthcare system.

Methods

Model overview

A cost-utility analysis using a state-transition model was used to compare the treatment strategies of apalutamide+ADT vs. ADT alone as first-line systemic therapy for patients with mCSPC. The state-transition model consisted of three, mutually exclusive health states of progression-free (PF), progressive disease (PD), and death.

The Canadian healthcare perspective was adopted for this analysis, incorporating only costs associated with publicly funded medical interventions. Primary outcomes included expected life-years (LY), quality-adjusted life-years (QALY), lifetime cost, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Health outcomes and cost were calculated over an estimated lifetime horizon (i.e., 20 years) in one-month time steps (cycle length). As per Canadian guidelines, health outcomes and cost were discounted at 1.5% per annum.11

The model was implemented using TreeAge 2021 software (TreeAge Software Inc., Williamstown, MA, U.S.).

Progression and survival estimates

The published TITAN PFS and updated OS Kaplan-Meier curves were used to inform the transition probabilities between health states. The curves were digitized with Plot Digitizer software (http://plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net) to derive estimates of pseudo-individual patient-level data, which were then used to generate fitted parametric survival curves (i.e., exponential, gamma, log-normal, log-logistic, Weibull). The best-fit parametric curve was derived according to best statistical fit (using the Akaike Information Criterion), visual inspection, and clinical plausibility. Based on this, the log-normal distribution was chosen to model the transitions from the PF to PD health states. The best-fit parametric curves were used to extrapolate survival beyond the trial duration to a lifetime time horizon.12,13 An exponential distribution was used to model the transition from the PD to death health state, based on clinical plausibility and model calibration to observed data from the updated OS Kaplan-Meier survival curves from the TITAN trial.10 The statistical analysis for curve generation and fitting was completed using R software (R Core Team 2013. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Baseline mortality due to non-cancer-related factors was also included in the transition from PF to death, as informed by Canadian-derived mortality tables for men aged 65 and older.14

Utility estimates

Utility estimates for the PF and PD health state for both treatment strategies were informed by the published literature from U.K.-derived estimates for patients with mCSPC for the PF health state and mCRPC for the PD health state.15–18 In order to capture a loss in health utility due to severe (i.e., grade 3/4) AE, disutilities for fall, fracture, rash, and seizure, were also included, with base values and duration informed by the published literature19–22 (Table 1)

Table 1.

Base-case analysis

| Treatment strategy | Life-years | QALY | Cost ($) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apalutamide + ADT | 5.56 | 4.84 | 255 633 | – |

| Progression-free | 4.71 | 4.19 | 240 021 | |

| Post-progression | 0.85 | 0.65 | 15 612 | |

| ADT | 4.11 | 3.51 | 36 582 | |

| Progression-free | 2.89 | 2.57 | 18 549 | |

| Post-progression | 1.22 | 0.94 | 18 033 | |

| Difference | 1.45 | 1.33 | 219 051 | – |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (cost ($)/LYG) | ||||

| Undiscounted | $142 767/LYG | |||

| Discounted (1.5%) | $151 070/LYG | |||

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (cost ($)/QALY) | ||||

| Undiscounted | $157 996/QALY | |||

| Discounted (1.5%) | $164 700/QALY | |||

Disaggregated health outcomes (life-years and QALYs) and costs for treatment with ADT with and without apalutamide. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, per LYG and QALY, for treatment with apalutamide + ADT, as compared to ADT alone demonstrated. All costs represented in 2020 Canadian dollars. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; LYG: life-year gain; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

Cost estimates

Costs for apalutamide+ADT were derived from list price estimates, as per the pan-Canadian Oncology Drug Review (pCODR) recommendations for the use of apalutamide for non-metastatic CRPC.23 Systemic therapy costs for post-progression treatment with abiraterone, bicalutamide, docetaxel chemotherapy, and enzalutamide was incorporated into the respective PD health states, as per the TITAN trial, with cost estimates based on list prices estimates and local institutional prices.10,23,24 Costs associated with physician visits and routine imaging during active systemic therapy were also included (Supplementary Table 1; available at cuaj.ca).

Costs for AE of interest that are expected to result in hospital admission were included for grade 3/4 fall, fracture, and/or seizure, based on rates informed by the TITAN trial.10 Costs were estimated from the Ontario Case Costing Initiative (OCCI) Cost Analysis Tool (CAT) as the mean (standard deviation) cost for hospitalization inclusive of direct patient costs only (i.e., nursing, diagnostic imaging, pharmacy and laboratory costs).25

A one-time cost for end-of-life care in hospital was incorporated into our model as a terminal cost for the PD health state. As the majority of patients receive their end-of-life care in hospital, this cost estimate was derived from the published literature based on the reported mean length of stay in hospital and/or hospice at the end-of-life for Canadian patients with a diagnosis of cancer.26

All costs were inflated to 2020 Canadian dollars using the Canadian Consumer Price Index (www.bankofcanada.ca).

Calibration and validation

Model calibration was conducted to the published PFS and updated OS Kaplan-Meier survival curves from the TITAN trial for the transition probability of PF to PD and transition probability of PD to death, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1; available at cuaj.ca)

Base-case analysis

A probabilistic analysis was used to evaluate all primary outcomes for apalutamide+ADT as compared to ADT alone, for a base-case cohort of Canadian men with newly diagnosed mCSPC. Cost estimates were characterized by gamma distributions, as derived by the mean and standard error (SE). Health state utility estimates and probabilities for events were characterized by beta distributions, as derived from the mean and SE (Supplementary Table 1; available at cuaj.ca) For estimates that did not have a value for SE, this was estimated as 25% of the expected range. Cholesky decomposition of the covariance matrix was used to correlate the parameters of the utilized log-normal distributions. The ICER was evaluated for apalutamide+ADT vs. ADT alone.

Scenario analyses

Scenario analyses were conducted to explore model uncertainty. This included two scenario analyses used to evaluate the uncertainty of the expected effectiveness estimates for the treatment strategies. First, a scenario analysis was completed within a trial time horizon (i.e., 52 months) to evaluate the proportion of expected health outcomes and costs derived from observable data, as compared to long-term expected outcomes. In addition, the uncertainty in the post-progression effectiveness estimates for apalutamide+ADT was evaluated through a scenario analysis of alternative expected mortality rates, as modeled with alternative rate parameters in the exponential distribution for the transition from the PD health state to death, to estimate varying five-year survival expectations.

Additionally, scenario analyses with alternative probabilities of post-progression systemic treatment following either treatment strategies were conducted, given the uncertainty in these estimates due to short followup in the TITAN trial.

A scenario analysis of price reductions for apalutamide was also conducted, given the high cost of treatment with apalutamide as compared to ADT, by evaluating the expected costs and ICER through price reduction of apalutamide by 25%, 50%, and 75%.

Results

Base case analysis

Apalutamide+ADT was associated with 5.56 expected LY, as compared to 4.11 with ADT. QALYs for apalutamide+ADT and ADT were 4.84 and 3.51, respectively. The expected lifetime costs of apalutamide+ADT and ADT were $255 633 and $36 582, respectively. The resultant ICER for apalutamide+ADT vs. ADT was $164 700/QALY. Table 1 presents the disaggregate health outcomes and cost for each strategy.

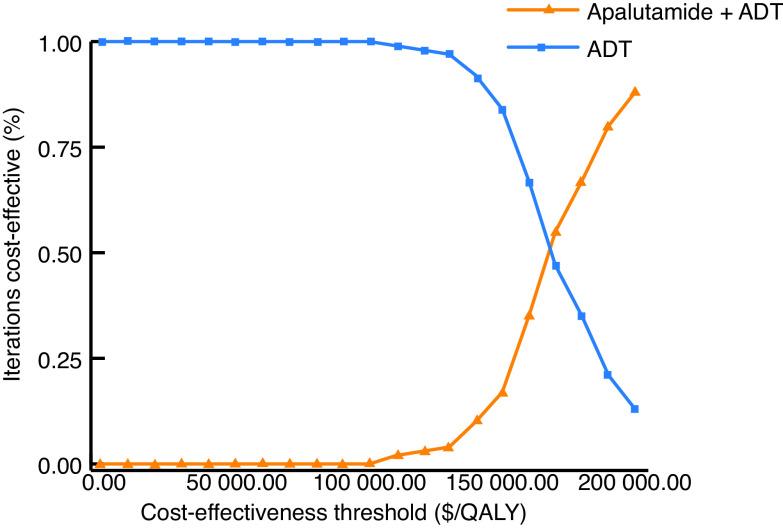

Fig. 1 depicts the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. At cost-effectiveness thresholds less than $100 000/QALY, ADT was the preferred therapeutic strategy.

Fig. 1.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve demonstrating the cost-effective strategy over a range of cost-effectiveness thresholds. ADT: androgen deprivation therapy; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

Scenario analyses

In the scenario analysis conducted using a within-trial time horizon from the updated OS analysis, apalutamide+ADT and ADT generated QALYs of 2.61 and 2.29, respectively, with an incremental gain in QALY of 0.32 with the combination. The incremental cost was $114 487 with the addition of apalutamide to ADT, with a resultant ICER of $357 772/QALY (Table 2). The incremental QALY within trial time horizon made up 24% of the expected lifetime incremental QALYs, while the incremental cost within trial time horizon made up 52% of expected lifetime incremental cost for apalutamide+ADT vs. ADT.

Table 2.

Scenario analysis within trial time-horizon

| Treatment strategy | QALY | Cost ($) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lifetime | Trial | % | Lifetime | Trial | % | |

| Apalutamide + ADT | 4.84 | 2.61 | 54 | 255 633 | 138 566 | 54 |

| Progression-free | 4.19 | 2.29 | 55 | 240 021 | 130 986 | 55 |

| Post-progression | 0.65 | 0.32 | 49 | 15 612 | 7580 | 49 |

| ADT | 3.51 | 2.29 | 65 | 36 582 | 24 079 | 66 |

| Progression-free | 2.57 | 1.72 | 67 | 18 549 | 12 394 | 67 |

| Post-progression | 0.94 | 0.57 | 61 | 18 033 | 11 685 | 65 |

| Difference | 1.33 | 0.32 | 24 | 219 051 | 114 487 | 52 |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [cost ($)/QALY] | $357 772/QALY | |||||

Disaggregated health outcomes and cost for treatment with apalutamide with and without ADT using a within trial time-horizon (i.e., 52 months), represented as the proportion of expected health outcomes and cost in a lifetime time-horizon. ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

The scenario analysis with different expected mortality rates post-progression with apalutamide+ADT is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2 (available at cuaj.ca). With an expected five-year survival rate of 67%, the ICER improved to $104 904/QALY.

Given the short trial followup, a scenario analysis of alternative probabilities of subsequent therapy was conducted, as summarized in Table 3. Although higher probabilities of subsequent therapy led to higher costs, no substantial difference in the resultant ICER was seen. Similarly, the ICER remained >$160 000/QALY in the scenario where higher rates of subsequent therapy were only applied following initial treatment with ADT alone.

Table 3.

Scenario analysis with alternative probabilities for subsequent therapy

| Scenario | Treatment strategy | QALY | Cost ($) | ICER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal probabilities to base case following ADT | Apalutamide+ADT | 4.84 | 255 578 | – |

| ADT | 3.51 | 36 582 | – | |

| Incremental | 1.33 | 218 996 | $164 659/QALY | |

| Two times the base case probability for subsequent therapy following ADT (equal) | Apalutamide+ADT | 4.84 | 256 283 | – |

| ADT | 3.51 | 38 221 | – | |

| Incremental | 1.33 | 218 062 | $163 956/QALY | |

| Two times the base case probability for subsequent therapy following ADT (for ADT only) | Apalutamide+ADT | 4.84 | 253 633 | – |

| ADT | 3.51 | 38 221 | – | |

| Incremental | 1.33 | 215 412 | $161 964/QALY | |

| Three times the base case probability for subsequent therapy following ADT (equal) | Apalutamide+ADT | 4.84 | 257, 823 | – |

| ADT | 3.51 | 39 553 | – | |

| Incremental | 1.33 | 218 270 | $164 113/QALY | |

| Three times the base-case probability for subsequent therapy following ADT (for ADT only) | Apalutamide+ADT | 4.84 | 253 633 | – |

| ADT | 3.51 | 39 553 | – | |

| Incremental | 1.33 | 214 080 | $160 962/QALY |

Scenario analysis of different rates of post-progression therapy, including: a) subsequent therapy for apalutamide+ADT equal to rates reported following ADT from TITAN trial; b) subsequent therapy estimated as twice the reported rate following ADT (applied to both strategies); c) subsequent therapy estimated as twice the reported rate following ADT (applied to the ADT strategy only); d) subsequent therapy estimated as three-times the reported rate following ADT (applied to both strategies); e) subsequent therapy estimated as three-times the reporting rate following ADT (applied to the ADT strategy only). ADT: androgen-deprivation therapy; ICER: incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

In the scenario analysis by price reduction for apalutamide, at a price reduction of 50%, apalutamide+ADT demonstrated an ICER of $87 567/QALY (Supplementary Table 2; available at cuaj.ca).

Discussion

Apalutamide+ADT resulted in an improvement in health outcomes as demonstrated by an improvement in both LYs and QALYs, as compared to ADT alone. However, the combination treatment also generated higher expected lifetime costs. With a resultant ICER of $164 700/QALY, apalutamide+ADT was not found to be cost-effective from the perspective of the Canadian, public-payer healthcare system at current list prices. However, apalutamide+ADT may be cost-effective at a cost-effectiveness threshold of $100 000/QALY with a price reduction of 50% or more.

Our analysis supports the clinical effectiveness of apalutamide+ADT vs. ADT alone, as evidenced by improvements in both LYs and QALYs. Consistent with clinical trial efficacy data, the clinical benefit for apalutamide+ADT was mostly driven by gains in health outcomes in the mCSPC setting.9 However, with a longer time spent in the mCSPC health state, patients treated with apalutamide+ADT also accrued higher expected costs in this health state, as compared to ADT. Accordingly, the lack of cost-effectiveness of apalutamide+ADT is largely driven by the high recurrent drug cost of apalutamide. As such, to improve cost-effectiveness, it is evident that reductions in the price of apalutamide are required, a conclusion supported by our scenario analyses.

The result of our scenario analysis within trial time horizon highlights the need for caution when interpreting expected, as compared to observed, data on health outcomes and cost. For both treatment strategies, the expected gains in QALYs and costs within trial time horizon represented less than 60% of the expected outcomes for apalutamide+ADT and less than 70% of the expected outcomes of ADT over a lifetime horizon. This highlights the impact of extrapolated outcomes on total expected lifetime estimates. As such, this highlights the need for re-evaluation with ongoing maturity of the TITAN trial, to more accurately assess the cost-effectiveness of this novel combination.

Across abiraterone, apalutamide, and enzalutamide, there is no clear superior choice for systemic therapy in mCSPC, with similar demonstrated efficacy through improvement in PFS and/or OS seen with all three agents.2,3,6,9,15,27 Although these therapies have the potential to lead to significant health benefits, their substantial costs highlight the need for demonstration of cost-effectiveness prior to adoption. Prior evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of abiraterone, in combination with ADT as compared to ADT alone, and as compared to docetaxel have been completed.18,28–30 Across these cost-effectiveness analyses of abiraterone plus ADT, none have demonstrated cost-effectiveness for abiraterone at current prices. A recently published cost-effectiveness analyses comparing all three ARATs, docetaxel+ADT and ADT alone found abiraterone+ADT to be the most cost-effective systemic therapy for mCSPC from the U.S. payer perspective.31 Future cost-effectiveness analyses of all available systemic therapy agents in mCSPC from the Canadian healthcare perspective is warranted.

Notable limitations of our analysis include the absence of granular data to inform all cost and effectiveness estimates. For instance, this model included only one line of therapy for patients who transitioned into the mCRPC setting, which may have misrepresented the included costs with both treatment strategies. There may also be under-representation of total healthcare costs, as only costs associated with select grade 3/4 AE were included. Further, in the absence of published results for Canadian-specific, preference-based estimates for quality-of-life in the PF and PD health state, utilities from the published literature based on U.K. populations were used, which may not be entirely representative of the Canadian population.32

Conclusions

Apalutamide in combination with ADT as first-line systemic therapy in the management of mCSPC was not found to be cost-effective at the current list price from the Canadian healthcare perspective. Cost-effectiveness may be improved with price reductions of apalutamide. Re-evaluation of cost-effectiveness with ongoing maturity of survival data is warranted to reduce the uncertainty in cost-effectiveness conclusions.

Supplementary Information

Footnotes

Appendix available at cuaj.ca

Competing interests: The authors do not report any competing personal or financial interests related to this work.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Sartor O, de Bono JS. Metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:645–57. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1701695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.James ND, de Bono JS, Spears MR, et al. Abiraterone for prostate cancer not previously treated with hormone therapy. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:338–51. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1702900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fizazi K, Chi KN. Abiraterone in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1697–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1711029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gravis G, Fizazi K, Joly F, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy alone or with docetaxel in non-castrate metastatic prostate cancer (GETUG-AFU 15): A randomized, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:149–58. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70560-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:737–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, et al. Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:121–31. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa1903835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavoie JM, Zou K, Khalaf D, et al. Clinical effectiveness of docetaxel for castration-sensitive prostate cancer in a real-world population-based analysis. Prostate. 2019;79:281–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.23733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreira RB, Debiasi M, Francini E, et al. Differential side effects profile in patients with mCRPC treated with abiraterone or enzalutamide: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Oncotarget. 2017;8:84572–8. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:13–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Bjartell A, et al. Apalutamide in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: Final survival analysis of the randomized, double-blind, phase 3 TITAN study. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:2294–2303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies: Canada. 4th Edition. 2017. [Accessed October 18, 2021]. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/guidelines_for_the_economic_evaluation_of_health_technologies_canada_4th_ed.pdf.

- 12.Guyot P, Ades AE, Ouwens MJ, et al. Enhanced secondary analysis of survival data: Reconstructing the data from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saluja R, Cheng S, Delos Santos KA, et al. Estimating hazard ratios from published Kaplan-Meier survival curves: A methods validation study. Res Synth Methods. 2019;10:465–75. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics Canada. Life Tables, Canada, Provinces and Territories. 2019. [Accessed October 18, 2021]. Available at: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/catalogue/84-537-X.

- 15.Chi KN, Protheroe A, Rodriguez-Antolin A, et al. Patient-reported outcomes following abiraterone acetate plus prednisone added to androgen deprivation therapy in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic castration-naive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): An international, randomized, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:194–206. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30911-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall F, de Freitas HM, Kerr C, et al. Estimating utilities/disutilities for high-risk metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) and treatment-related adverse events. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1191–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02117-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lloyd AJ, Kerr C, Penton J, et al. Health-related quality of life and health utilities in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer: A survey capturing experiences from a diverse sample of UK Patients. Value Health. 2015;18:1152–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2015.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sathianathen NJ, Alarid-Escudero F, Kuntz KM, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of systemic therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2019;2:649–55. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doyle S, Lloyd A, Walker M. Health state utility scores in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2008;62:374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matza LS, Chung K, Van Brunt K, et al. Health state utilities for skeletal-related events secondary to bone metastases. Eur J Health Econ. 2014;15:7–18. doi: 10.1007/s10198-012-0443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nafees B, Stafford M, Gavriel S, et al. Health state utilities for non small cell lung cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:84. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. The epilepsies: Clinical practice guidelines. 2010. [Accessed October 18, 2021]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137/documents/epilepsy-update-full-guideline-appendix-p2.

- 23.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. [Accessed October 18, 2021];Erleada for castrate-resistant prostate cancer. 2018 Availabe at: https://www.cadth.ca/erleada-castrate-resistant-prostate-cancer-details. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. [Accessed October 18, 2021];Zytiga for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. 2013 Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/zytiga-metastatic-castration-resistant-prostate-cancer-details. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ministry of Health and Long Term Care. [Accessed October 18, 2021];Ontario case costing initiative. 2019 Available at: https://hsim.health.gov.on.ca/hdbportal/?destination=front_page. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bekelman JE, Halpern SD, Blankart CR, et al. Comparison of site of death, healthcare utilization, and hospital expenditures for patients dying with cancer in 7 developed countries. JAMA. 2016;315:272–83. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal N, McQuarrie K, Bjartell A, et al. Health-related quality of life after apalutamide treatment in patients with metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (TITAN): A randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:1518–30. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30620-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguiar PN, Jr, Tan PS, Simko S, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of abiraterone, docetaxel or placebo plus androgen deprivation therapy for hormone-sensitive advanced prostate cancer. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2019;17:eGS4414. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2019GS4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang CL, So TH, Lam TC, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of abiraterone acetate vs. docetaxel in the management of metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer: Hong Kong’s perspective. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23:108–15. doi: 10.1038/s41391-019-0161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hird AE, Magee DE, Cheung DC, et al. Abiraterone vs. docetaxel for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: A microsimulation model. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;14:E418–27. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sung WWY, Choi HCW, Luk PHY, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of systemic therapy for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:627083. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.627083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heijink R, Reitmeir P, Leidl R. International comparison of experience-based health state values at the population level. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:138. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.