Dear Editor,

Many COVID-19 patients develop a coagulopathy characterized by thrombocytopenia, minor prolongation of bleeding times and elevated serum d-dimer and fibrinogen levels, similar to consumption coagulopathy [1], together with severe endothelial injury, and alveolar capillary microthrombi [2]. Moreover, several studies reported an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), as well as large-vessel thrombosis. In particular, the incidence of VTE in COVID-19 patients was 8 to 69% [3], which is significantly higher than in critically ill patients with H1N1 influenza and sepsis. Two retrospective studies from China also confirmed that overt DIC is a common finding in COVID-19 patients, occurring in about 70% of non-surviving patients [4]. A recent meta-analysis also showed a high incidence of pulmonary embolism (PE) in COVID-19 patients, reaching 15.3% in those needing hospitalization [5].

Therefore, COVID-19-related coagulopathy and thrombotic events likely contribute to COVID-19-related morbidity and mortality, suggesting that anticoagulation treatment may be beneficial for hospitalized patients. In particular heparin, which has proven anti-inflammatory effects, and is commonly used in hospitalized patients with a high risk of VTE, appears to be the drug of choice. However, the appropriate treatment regimens are still uncertain, as standard dose anticoagulation does not appear to be completely effective in preventing VTE in COVID-19 patients [6]. Moreover, therapeutic-dose anticoagulation may be effective in hospitalized patients with moderate COVID-19 not requiring ICU level care, but not in those with severe COVID-19 in critical care settings, due to increased risk of bleeding [7]. Additionally, prophylactic-intensity anticoagulation over other regimens was recommended in spite of low-level evidence of its beneficial effects [8].

Therefore, we conducted an observational, retrospective, case-control study to investigate the appropriate anticoagulation treatment for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, comparing standard prophylactic dose of Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) and higher doses of LMWH based on patients’ weight. We assessed heparin efficacy in preventing VTE events, mortality rates and need for ICU treatment, as well as the occurrence of bleeding complications.

We enrolled 277 consecutive COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe symptoms, admitted to San Matteo Foundation Hospital in Pavia during the first COVID-19 epidemic wave (February 2020-June 2020). All patients had clinical, laboratory and radiological findings consistent with infection, as well as molecular evidence of SARS-COV-2 either from nasopharyngeal swabs and/or broncho-alveolar lavage or a positive serological test.

Supplementary material, Table 1S and 2S, show inclusion criteria and the main clinical characteristic respectively. Eligible patients (mean age 65 ± 8 years) were then divided into two groups: one hundred and forty-six (36 F, 110 M) received a standard prophylactic dose of enoxaparin (4000 IU once daily), irrespective of body weight while one hundred and thirty-one (62 F, 69 M) received weight-adjusted enoxaparin. In particular, sixty-five patients received 4000 IU once daily if their weight was between 45 and 65 Kg (23.5%), fifty-eight received 6000 IU once daily if their weight was between 66 and 100 Kg (20.9%) and eight were administered 8000 IU once daily if their weight was > 100 Kg (2.9%). Enoxaparin was administered in both cohorts for 14 days or until discharge, death or the occurrence of complications requiring heparin discontinuation or upgrading.

Patients were evaluated daily for their respiratory function, hemodynamic stability and oxygen need during hospitalization (Supplementary material, Table 3S). CT scan of the thorax was performed when respiratory conditions rapidly deteriorated to exclude pulmonary embolism, and vascular ultrasound was used for the diagnosis of suspected deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

Main in-hospital complications (Table 4S) were co-infection by bacterial or fungal agents, acute kidney failure and acute liver failure. Acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed in 14 patients; of these, 13 were in the standard dose enoxaparin group and only 1 in the weight-adjusted enoxaparin group (p-value 0.002).

Twenty-eight patients developed VTE (10.1%). Of these, 11 were diagnosed with venous thrombosis, the majority either in the upper or lower limbs: 4 in the group treated with standard dose enoxaparin (2 distal and 2 proximal DVT) and 7 in the other group (2 distal and 5 proximal DVT). Seventeen patients (10 in the group treated with standard dose LMWH and 7 in the group receiving weight-adjusted LMWH) had PE.

Eleven patients had bleeding complications. Of these, seven were in the group treated with weight-adjusted enoxaparin, but the increased frequency of these events was not statistically significant. Major bleeding events occurred in five patients in the group treated with LMWH adjusted to weight versus three in the group treated with standard dose heparin. Such difference was not statistically significant.

Thirty-three patients were admitted to the ICU during the first seven days of hospitalization. Of these, 20 received 4000 IU enoxaparin once daily irrespective of weight, while 13 were treated with LMWH adjusted to weight.

The combined endpoint of in-hospital mortality or admission to the ICU during the first week of hospitalization was observed in 85 patients, with a rate of 10.9 events per 100 patients per week (95%, CI 8.8 - 13.4).

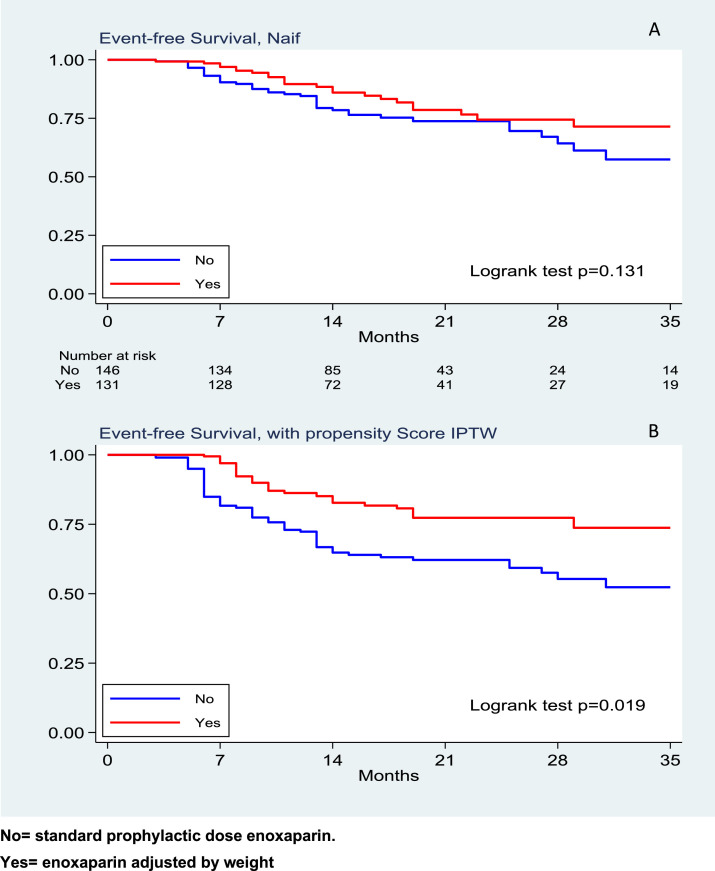

We observed 48 deaths in the group treated with 4000 IU enoxaparin once daily and 37 deaths in the group treated with weight-adjusted enoxaparin. This resulted in a mortality rate of 12 (95%, CI 9 – 16) and 9 (95% CI 7 - 13) events respectively, per 100 patients per week (logrank test p = 0.131) (Fig. 1 A.) The corresponding HR was 0.72 (95%CI 0.46–1.11); after weighting the analysis by the inverse probability of using the weight-adjusted strategy, such treatment resulted in a protective effect toward the combined endpoint of death and intensive care admission, with a HR 0.46, (95%,CI 0.24–0.88, p = 0.019), (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Event-free survival with univariate analysis (A) and with propensity score (B) respectively

No= standard prophylactic dose enoxaparin.

Yes= enoxaparin adjusted by weight.

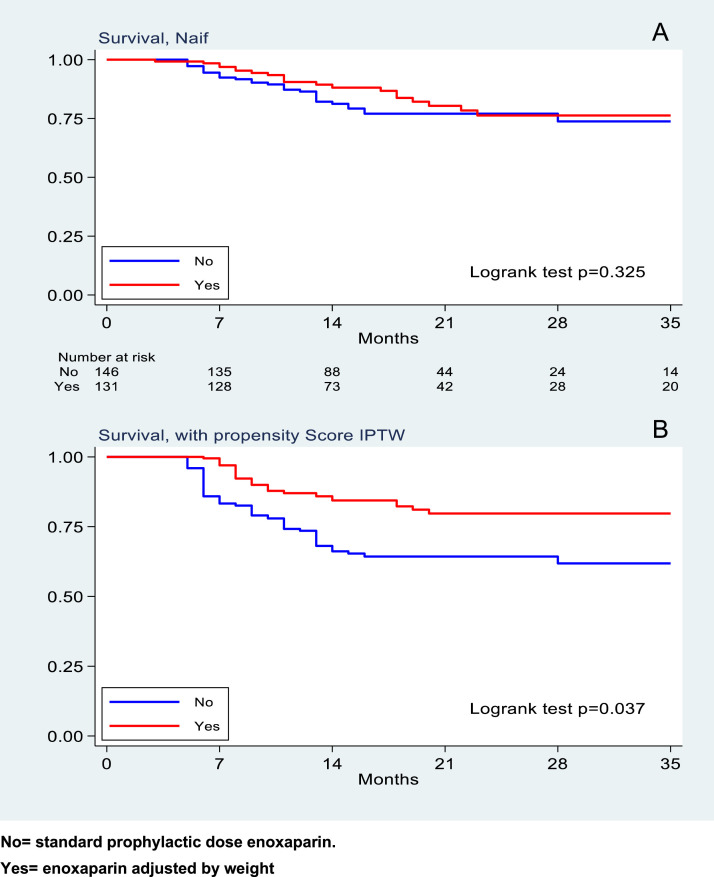

In-hospital mortality was observed in 57 patients, with a rate of 7.1 events per 100 patients per week (95%, CI 5.5 - 9.2). 33 deaths were in the group treated with standard enoxaparin and 24 deaths in the weight-adjusted enoxaparin group. This results in a mortality rate of 8 (95% CI 6 – 12) and 6 (95% CI 4 – 9) events per 100 patients per week (log-rank test p = 0.325), (Fig. 2 A). The corresponding HR was 0.77 (95% CI 0.45–1.3); after weighting the analysis by the inverse probability of using the weight-adjusted strategy, such treatment resulted in a protective effect toward the secondary endpoint of in-hospital mortality, with a HR 0.46, (95% CI 0.22–0.95, p = 0.037), (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Survival with univariate analysis (A) and with propensity score (B) respectively.

No= standard prophylactic dose enoxaparin.

Yes= enoxaparin adjusted by weight.

Additionally, the use of CPAP was lower in the group treated with weight-adjusted LMWH compared to the group receiving standard dose heparin (42 vs 83 patients; p-value 0.090). The same observation was not confirmed for oro-tracheal intubation: though fewer patients were intubated when treated with LMWH adjusted to weight, the difference was not significant. At three-month follow-up one patient died and one was readmitted for PE, both in the standard heparin dose group.

Our results show that the use of LMWH adjusted to weight for the treatment of hospitalized COVID-19 patients with moderate to severe symptoms appears to be effective in reducing in-hospital mortality rates and the need for admission to the ICU during the first week of hospitalization. This is particularly clear when the propensity score model is used to reduce the effect of confounding factors.

Moreover, our study shows that the use of higher doses of LMWH compared to standard doses significantly reduces the need for CPAP in hospitalized patients, but it does not have the same beneficial effects if oro-tracheal intubation is required. This confirms the need to administer heparin at the onset of the disease, possibly to contrast the effects of the “cytokine storm” and subsequent thrombus formation.

Our data suggest that there is no difference between standard dose LMWH vs. weight-adjusted LMWH in terms of VTE events, though PE appears to be more frequent in the group treated with 4000 IU once daily. However, these findings could be underestimated because our patients were not routinely screened for DVT by venous ultrasound and CT scans of the thorax were initially limited to patients with a high suspicion of PE based on worsening clinical conditions and laboratory findings.

Our observation of significantly lower mortality rates and a reduced need for short term intensive treatment without a concomitant reduction of VTE events suggests that higher doses of LMWH may have an impact primarily on the formation of thrombi in the microcirculation instead of large vessels. In fact, microthrombi were found in pulmonary vessels [2] and heart specimens [9] of COVID-19 patients. Moreover, in the majority of PE diagnoses, radiological findings were consistent with micro- or subsegmental embolism. Our hypothesis is further supported by evidence from our study that the use of higher doses of heparin compared to standard doses also appears to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction in COVID-19 hospitalized patients. Indeed, an association between microthrombosis and myocardial infarction in COVID-19 patients has been suggested [10].

In terms of safety, our study shows that the administration of weight-adjusted heparin is not associated with a significantly increased risk of bleeding, but additional studies are needed to support this conclusion.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The Authors report no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2022.03.015.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Barrett C.D., Moore H.B., Yaffe M.B., Moore E.E. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19: a comment. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):2060–2063. doi: 10.1111/jth.14860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M., Haverich A., Welte T., Laenger F., Vanstapel A., Werlein C., Stark H., Tzankov A., Li W.W., Li V.W., Mentzer S.J., Jonigk D. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., Arbous M.S., Gommers D.A.M.P.J., Kant K.M., Kaptein F.H.J., van Paassen J., Stals M.A.M., Huisman M.V., Endeman H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao S.C., Shao S.C., Chen Y.T., Chen Y.C., Hung M.J. Incidence and mortality of pulmonary embolism in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):464. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03175-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miesbach W., Makris M. COVID-19: coagulopathy, risk of thrombosis, and the rationale for anticoagulation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26 doi: 10.1177/1076029620938149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giannis Dimitrios, Douketis James, Spyropoulos Alex. Anticoagulant therapy for COVID-19: what we have learned and what are the unanswered questions? Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2021:96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuker A., Tseng E.K., Nieuwlaat R., Angchaisuksiri P., et al. American Society of Hematology 2021 guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis in patients with COVID-19. Blood Adv. 2021;5(3):872–888. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bois M.C., Boire N.A., Layman A.J., Aubry M.C., Alexander M.P., Roden A.C., Hagen C.E., Quinton R.A., Larsen C., Erben Y., Majumdar R., Jenkins S.M., Kipp B.R., Lin P.T., Maleszewski J.J. COVID-19-associated non occlusive fibrin microthrombi in the heart. Circulation. 2021;143(3):230–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guagliumi G., Sonzogni A., Pescetelli I., Pellegrini D., Finn A.V. Microthrombi and ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction in COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;142(8):804–809. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.049294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.