Abstract

Background:

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a widely utilized biomarker of autonomic regulatory functioning, and concomitant health or pathological states. A growing body of work is exploring HRV under sleeping conditions. Most of this literature utilizes either averaged HRV indices calculated from multiple sleep stage epochs, or averaged HRV throughout the night. Both approaches implicitly assume that HRV within sleep epoch types is consistent throughout the night. Given the robust literature indicating the existence of an endogenous cardiovascular circadian rhythm as well as the potential for effects for cumulative time asleep, we hypothesized that HRV would vary across distinct sleep epochs.

Methods:

Participants underwent at least one night of home polysomnography that included electroencephalogram, electromyogram, and electrocardiogram (N = 73). All rapid eye movement (REM) and non-REM stage 2 (N2) sleep epochs with a duration greater than or equal to five minutes were identified for HRV analysis. Time and frequency domain indices of HRV were calculated for each sleep stage epoch. Linear mixed models were used to examine main effects of time on HRV indices for N2 and REM sleeps epochs respectively.

Results:

Main effects of time were observed for all models. Patterns emerged for both the N2 and REM epochs, suggesting HRV indices are non-stationary (i.e., variable) across distinct sleep epochs through the course of the night.

Conclusions:

The present findings indicate HRV is non-stationary across sleep stage epochs. Aggregating HRV indices across sleep stage epochs likely obscures important transient effects and increases risk of type-I and type-II errors.

Keywords: heart rate variability, sleep-stage, N2 sleep, REM sleep, stationarity

1. Introduction

Heart rate variability (HRV)—the variance in beat-to-beat intervals of the heart—is a widely utilized biomarker of central autonomic network regulatory functioning, and concomitant health and pathological states (1, 2). Physical and psychological health states are typically associated with high resting HRV, reflecting psychophysiological complexity and flexibility (3, 4). Conversely, physical disease states and psychopathology are commonly associated with lower HRV (5, 6).

Whereas most research has focused on HRV under waking conditions, a growing body of work is exploring HRV during sleep. Most of this literature utilizes either averaged HRV indices calculated from multiple sleep stage epochs (e.g., average HRV across REM epochs; 7, 8) or averaged HRV throughout the night (i.e., without considering distinct sleep stages; 9, 10). Both these approaches assume stationarity of HRV measures across sleep stage epochs and types. We explored HRV within two important sleep stages; rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, which is characterized by saccadic eye movements, variable respiratory and heart rate, muscle atonia, and dream activity, and non-REM stage 2 (N2) sleep, which is characterized by slower and more stable heart rate, reduced body temperature, and electroencephalographic K-complexes and sleep spindles.

Given the robust literature indicating the existence of an endogenous cardiovascular circadian rhythm (11) as well as the potential for effects for cumulative time asleep, we hypothesized that HRV would vary across distinct N2 epochs and REM epochs.

2. Method

Parent study methods have previously been reported (12) and are summarized here. This study was approved by the Mass General Brigham Institutional Review Board.

2.1. Participants

Participants were adults, ages 18-70 with insomnia or major depressive disorder (MDD), as well as healthy controls who were recruited for a study evaluating regional neurochemical alterations in insomnia and MDD using Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy.

2.2. Procedure

Participants underwent at least one night of home polysomnography that included electrocardiogram (ECG). Polysomnography was conducted using an ambulatory Somte PSG (Compumedics, Charlotte, NC). The digitized polysomnography sleep data were visually scored by a single licensed polysomnographic technologist (PSGT) using revised scoring criteria specified by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Visual scoring included standard measures of sleep architecture identifying sleep stages N2 and REM. Patients with an apnea-hypopnea index score >15, or with >15 periodic limb movements during sleep were excluded from analyses.

All N2 and REM sleep epochs with a duration ≥5min were identified for HRV analysis. ECG waveforms from the specified epochs were visually examined for irregularities such as missed, misplaced, or ectopic beats using Kubios (13), and where possible these were manually corrected. In cases where manual correction was insufficient or impossible, the automatic correction feature in Kubios was applied. Indices of HRV were calculated for individual epochs of at least five minutes of uninterrupted N2 sleep and REM sleep.

Time domain indices included heart rate (HR), the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN), root mean squared of successive differences (RMSSD), and the percent of adjacent normal-to-normal intervals differing by > 50ms (pNN50). In the frequency domain, we explored high frequency HRV (HF HRV; 0.15–0.4Hz), and low frequency HRV (LF HRV; 0.04–0.15Hz) calculated using fast Fourier transform. By convention, all HRV indices except HR and pNN50 were logarithmically transformed for analysis. Multivariate measures included Kubios’ parasympathetic nervous system index (computed from mean R-R interval, RMSSD, and Poincaré plot SD1), and sympathetic nervous system index (computed from HR, Baevsky’s stress index, and Poincaré plot SD2) (14). The non-linear measure approximate entropy was also included (15), which measures HRV complexity, wherein greater values indicate greater signal irregularity and smaller values greater signal regularity.

2.3. Analyses

First, to identify and control for multivariate outliers, Mahalanobis distances (16) were calculated using the indices HR, HF HRV, and LF HRV. Skew and kurtosis were subsequently assessed for all HRV indices to ensure normal distribution.

Linear mixed models were used to examine main effects of time on HRV indices for N2 and REM sleep epochs respectively. Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) scores were used to guide selection of model variance-covariance matrix structure. Compound symmetry variance-covariance matrices were chosen for all models. Significant main effects of time were probed using least square means difference tests to assess change in HRV indices across N2 and REM epochs respectively. All analyses were conducted in SAS 9.4 (17).

3. Results

Data for 28 participants were excluded due to excessive noise artifacts in ECG signals, arrythmias, and/or excessive sleep artifacts related to movement, leaving a total of 39 participants in the MDD group, 14 participants in the insomnia group, and 20 healthy controls (N = 73). Excluded participants were on average older and had greater BMI but were not different on measures of depression, insomnia, or sleep (see 12). A total of 144.28 N2 sleep stage hours and 71.00 REM sleep stage hours were included in the analysis. On average, N2 epoch lengths were 11.05 minutes and REM epoch lengths were 13.21 minutes.

All HRV indices were found to be normally distributed. Of the 1,305 data points (i.e., number participants × distinct sleep-stages) two outliers (i.e., Mahalanobis scores with p < 0.001) were detected and removed.

The sample was on average 29.8 years old (SD = 10.9), 74% female, and had a mean body-mass index of 22.8 (SD = 3.4).

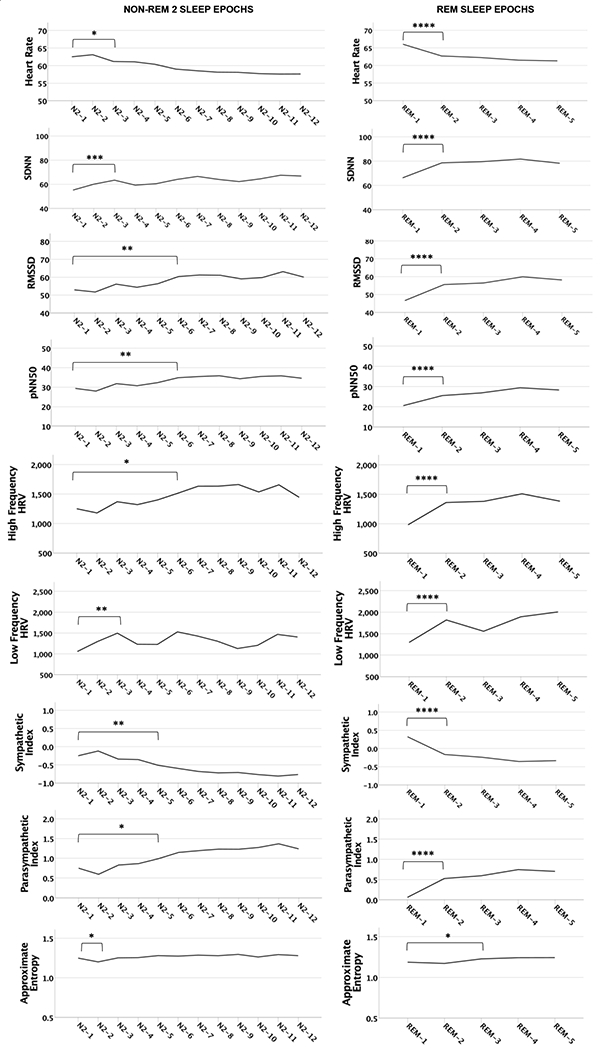

Linear mixed model results are reported in Table 1. Main effects of time were observed for all models. Post hoc tests are reported in detail in Supplemental Materials 1, with average HRV levels for each HRV index for both N2 sleep epochs and REM sleep epochs graphed in Figure 1.

Table 1.

Heart rate variability measures by sleep stage, with F statistics from linear mixed models.

| Model χ2 (df=1) | Group F (df= 2, 70) | Time F (df= 11, 695) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (bpm) | |||

| N2 | 1157.48**** | 1.67 | 22.06**** |

| REM | 387.66**** | 1.19 | 27.99**** |

| SDNN (ms) | |||

| N2 | 545.67**** | 0.56 | 3.84**** |

| REM | 228.98**** | 0.63 | 13.57**** |

| RMSSD (ms) | |||

| N2 | 903.02**** | 0.64 | 5.08**** |

| REM | 323.92**** | 0.41 | 18.24**** |

| pNN50 (%) | |||

| N2 | 948.38**** | 0.68 | 4.18**** |

| REM | 350.04**** | 0.66 | 13.61**** |

| High Frequency HRV (ms^2) | |||

| N2 | 824.44**** | 0.76 | 3.27*** |

| REM | 281.78**** | 0.32 | 12.40**** |

| Low Frequency HRV (ms^2) | |||

| N2 | 368.96**** | 0.88 | 2.29** |

| REM | 212.82**** | 0.01 | 7.48*** |

| Sympathetic Index | |||

| N2 | 889.57**** | 1.63 | 12.90**** |

| REM | 301.32**** | 1.01 | 24.69**** |

| Parasympathetic Index | |||

| N2 | 1093.30**** | 1.03 | 9.34**** |

| REM | 357.85**** | 0.94 | 17.50**** |

| Approximate Entropy | |||

| N2 | 46.51**** | 1.10 | 2.28** |

| REM | 74.84**** | 0.46 | 5.28*** |

Notes. Standard deviations are in parentheses. SDNN= Standard deviation of all normal-to-normal intervals, RMSSD= Root of the mean squared differences of successive normal-to-normal intervals, pNN50 = percent of normal-to-normal adjacent intervals greater than 50ms, HRV= heart rate variability. Model chi square (χ2) denotes model omnibus test results. F statistics are shown for model main effects of group and time.

p< .0001

p< .001

p< .001

p< .05

Figure 1.

Heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) by sleep stage (N2 / REM) and sleep epoch. Though not indicated in the figure, all epoch contrasts subsequent to the first significant contrast shown for each sleep stage/HRV index are statistically significant, with the exception of N2 / SDNN epochs 1 & 4, N2 / LF HRV epochs 1 & 3 and 1 & 4, and for N2 / Approximate Entropy all contrasts are non-significant except epochs 1 & 2; see Supplement 1 for all contrasts. Standard deviations are in parentheses. SDNN= Standard deviation of all normal-to-normal intervals, RMSSD= Root of the mean squared differences of successive normal-to-normal intervals, pNN50 = percent of normal-to-normal adjacent intervals greater than 50ms. **** p< .0001, *** p< .001, ** p< .001, * p< .05.

N2 Findings

Results from the N2 analysis showed that in terms of sympathetic nervous system activation, HR during the first N2 epoch was significantly different from all subsequent N2 epochs (with the exception of the second epoch), while the sympathetic index during N2 epoch 1 was significantly different from the fifth and all subsequent N2 epochs. In addition, post hoc contrasts indicated both mean HR and sympathetic index scores varied significantly across most other N2 epochs, suggesting these measures are highly labile across N2 episodes through the night.

The first N2 epoch of the night was also characterized by lower levels of parasympathetic nervous system activation compared to the third (SDNN), fifth (parasympathetic index), and sixth (RMSSD, pNN50, HF HRV, LF HRV) subsequent N2 epochs. In addition, post hoc contrasts indicated that SDNN, RMSSD, pNN50, HF HRV, LF HRV, and the parasympathetic index varied significantly between many other N2 epochs, indicating these measures are also labile across N2 episodes through the night. Approximate entropy was significantly higher during the first N2 epoch of the night compared to the second, but not subsequent N2 epochs.

REM Findings

Results from the REM analysis indicate the first REM episode of the night was characterized by higher levels of sympathetic nervous system activation, including mean HR and sympathetic index, than all subsequent REM epochs. The first REM epoch of the night was also characterized by lower parasympathetic nervous system activation including SDNN, RMSSD, pNN50, HF HRV, LF HRV, and parasympathetic index, compared to all subsequent REM epochs. Post hoc contrasts showed that all HRV indices for REM epochs 2-5 were not significantly different from one another, suggesting stationarity for HRV indices during REM after the first REM episode of the night. Approximate entropy was also higher during the first REM epoch of the night compared to the third, fourth and fifth REM epochs of the night, but was not significantly different from the second epoch.

4. Discussion

HRV is increasingly being explored as a biomarker of health and pathology in sleep research; however, most research to date has utilized either averaged HRV indices calculated from multiple sleep stage epochs or averaged HRV across the night. While under some circumstances this approach may be appropriate, in many study designs researchers are making assumptions about the stationarity of HRV indices across sleep stage epochs. Here we tested this assumption. Main effects of time were observed for all models, with patterns emerging for both the N2 and REM epochs suggesting that HRV indices are non-stationary (i.e., variable) across distinct sleep epochs through the course of the night. Most notably, a clear shift in HRV appears to occur from REM epoch 1 to subsequent REM episodes, and HRV during N2 sleep epochs appears highly variable through the night.

Multiple mechanisms could account for the finding of non-stationarity of HRV including a circadian process, a homeostatic time in sleep process (often measured as slow wave power), and/or a differential rate of transient arousals across the night. Circadian effects on cardiovascular function have been well documented using forced desynchrony methods (18) as well as in circadian gene polymorphisms (19) and may contribute to the observed changes in both N2 and REM over the course of the sleep period. Similarly, time-varying changes in slow wave power, which dissipates with time in sleep, even within N2 epochs, are known to affect HRV (20). Such reduction in homeostatic drive is particularly pronounced over the first part of the night, which is the time at which our observed changes in N2 were also present.

Transient arousals from sleep also produce predictable effects on HRV (21). In particular, autonomic influences on HR precede the onset of, and persist during EEG arousals. Differential distribution of arousals throughout the sleep period may account for the observed changes in HRV across both N2 and REM epochs in this study. To distinguish among these variable mechanisms responsible for our findings, the optimal approach would be to use a forced desynchrony protocol (22), in which participants’ sleep-wake cycles are adjusted to a period (e.g., 28 hours) outside the range of which the endogenous circadian clock is able to entrain, allowing it to free-run according to its own period. Using forced desynchrony, features of sleep (e.g., homeostatic drive, arousals from sleep) can be assessed at all circadian phases, disentangling otherwise confounded processes. Though the experimental design of the present study did not allow us to tease out the effects of these mechanisms, taken together, our findings highlight the importance of considering sleep epochs in nocturnal HRV research.

5. Limitations

1) Just over one-quarter of the original sample was excluded due to excessive noise artifacts in ECG signals, arrythmias, and/or excessive sleep artifacts related to movement. 2) The older age and greater body mass index of excluded participants may have introduced selection bias into the results. 3) In addition to healthy controls, our sample included individuals with depression, and insomnia. Although no between group differences in HRV were observed (12), this may have influenced the results in unknown ways. 4) We did not measure transient arousals; these might have been more frequent from one sleep stage epoch to the next, which may have influenced HRV in unknown ways. 5) Study results were dependent on the accuracy of sleep stage identification from the raw polysomnography record. Although sleep stage identification was done by a trained and certified expert, any errors in this stage of data analysis would have affected the HRV findings presented here in unknown ways.

6. Conclusions

The present findings indicate HRV is non-stationary (i.e., variable) across sleep stage epochs. Thus, aggregating HRV indices across sleep stage epochs likely obscures important circadian or cumulative time asleep effects. Further, not controlling for this variance may have led to type-I and type-II errors in previous studies exploring sleep-state HRV. Future sleep studies exploring HRV should factor variance in HRV across sleep stage epochs into their analyses.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Increasingly, heart rate variability (HRV) is being studied during sleep.

Most studies aggregate HRV scores rather than considering sleep epochs separately.

We explored the hypothesis that HRV varies across distinct sleep stage epochs.

HRV scores across distinct N2 and distinct REM epochs varied significantly.

Aggregating HRV scores across sleep stage epochs likely increases risk of error.

Acknowledgements:

This research was conducted with the support of NIMH grants RO1MH095792-01A1 and K23MH120436-01, and NIAAA grants K23AA027577-01A1 and L30AA026135-02.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beissner F, Meissner K, Bar KJ, Napadow V. The autonomic brain: An activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis for central processing of autonomic function. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33(25):10503–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCraty R, Shaffer F. Heart rate variability: New perspectives on physiological mechanisms, assessment of self-regulatory capacity, and health risk. Global advances in health and medicine. 2015;4(1):46–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehrer P, Eddie D. Dynamic processes in regulation and some implications for biofeedback and biobehavioral interventions. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2013;38(2):143–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemp AH, Quintana DS. The relationship between mental and physical health: Insights from the study of heart rate variability. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2013;89(3):288–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eddie D, Price JL, Bates ME, Buckman JF. Substance use and addiction affect more than the brain: The promise of neurocardiac interventions. Current Addiction Reports. 2021;8:431–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eddie D, Bates ME, Buckman JF (2022). Closing the brain—heart loop: Towards more holistic models of addiction and addiction recovery. Addiction Biology. 27(1), e12958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyunbin K, Heenam Y, Dawoon J, Sangho C, Jaewon C, Yujin L, et al. Heart rate variability in patients with major depressive disorder and healthy controls during non-REM sleep and REM sleep. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society Annual International Conference. 2017;2017:2312–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Togo F, Yamamoto Y. Decreased fractal component of human heart rate variability during non-REM sleep. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology.2001;280(1):H17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al Haddad H, Laursen PB, Ahmaidi S, Buchheit M. Nocturnal heart rate variability following supramaximal intermittent exercise. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2009;4(4):435–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vahle-Hinz T, Bamberg E, Dettmers J, Friedrich N, Keller M. Effects of work stress on work-related rumination, restful sleep, and nocturnal heart rate variability experienced on workdays and weekends. J Occup Health Psychol. 2014;19(2):217–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen L, Yang G. Recent advances in circadian rhythms in cardiovascular system. Front Pharmacol. 2015;6:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddie D, Bentley KH, Bernard R, Yeung A, Nyer M, Pedrelli P, et al. Major depressive disorder and insomnia: Exploring a hypothesis of a common neurological basis using waking and sleep-derived heart rate variability. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;123:89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarvainen MP, Niskanen J-P, Lipponen JA, Ranta-Aho PO, Karjalainen PA. Kubios HRV—heart rate variability analysis software. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2014; 113(1):210–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubios. Parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system indexes 2019. [Available from: https://www.kubios.com/about-hrv/.

- 15.Fusheng Y, Bo H, Qingyu T. Approximate entropy and its application in biosignal analysis. Nonlinear biomedical signal processing: Dynamic analysis and modeling. 2. New York, NY: IEEE Press; 2001. p. 72–91. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Maesschalck R, Jouan-Rimbaud D, Massart DL. The mahalanobis distance. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems. 2000;50:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.SAS Institute. SAS 9.4 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS institute Inc.; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu K, Ivanov PC, Hilton MF, Chen Z, Ayers RT, Stanley HE, et al. Endogenous circadian rhythm in an index of cardiac vulnerability independent of changes in behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(52):18223–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo MT, Bandin C, Yang HW, Scheer F, Hu K, Garaulet M. CLOCK 3111T/C genetic variant influences the daily rhythm of autonomic nervous function: Relevance to body weight control. Int J Obes. 2018;42(2):190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang CC, Lai CW, Lai HY, Kuo TB. Relationship between electroencephalogram slow-wave magnitude and heart rate variability during sleep in humans. Neurosci Letters. 2002;329(2):213–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonnet MH, Arand DL. Heart rate variability: sleep stage, time of night, and arousal influences. Electroencephalography and clinical Neurophysiology. 1997;102(5):390–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czeisler CA, Duffy JF, Shanahan TL, Brown EN, Mitchell JF, Rimmer DW, et al. Stability, precision, and near-24-hour period of the human circadian pacemaker. Science. 1999;284(5423):2177–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.