Abstract

Nuclear medicine procedures are generally avoided during pregnancy out of concern for the radiation dose to the fetus. However, for clinical reasons, radiopharmaceuticals must occasionally be administered to pregnant women. The procedures most likely to be performed voluntarily during pregnancy are lung scans to diagnose pulmonary embolism and 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) scans for the staging of cancers. This article focuses on the challenges of fetal dose calculation after administering radiopharmaceuticals to pregnant women. In particular, estimation of the fetal dose is hampered by the lack of fetal biokinetic data of good quality and is subject to the variability associated with methodological choices in dose calculations, such as the use of various anthropomorphic phantoms and modeling of the maternal bladder. Despite these sources of uncertainty, the fetal dose can be reasonably calculated within a range that is able to inform clinical decisions. Current dose estimates suggest that clinically justified nuclear medicine procedures should be performed even during pregnancy because the clinical benefits for the mother and the fetus outweigh the purely hypothetical radiation risk to the fetus. In addition, the fetal radiation dose should be minimized without compromising image quality, such as by encouraging bladder voiding and by using positron emission tomography (PET)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) devices or high-sensitivity PET scanners that generate images of good quality with a lower injected activity.

Introduction

The administration of radiopharmaceuticals to pregnant women is a reason for concern due to the possible higher radiosensitivity of the embryo and fetus. Given that the number of nuclear medicine examinations has been steadily increasing worldwide for the past few decades1, it seems likely that the number of pregnant women being administered radiopharmaceuticals will continue to increase commensurately. Indeed, over the course of the last 20 years, positron emission tomography (PET) went from being a sophisticated research tool available in only few selected academic institutions to being routinely used in more than two million clinical examinations per year in the US alone, with an annual rate of increase of about 6% per year2.

Radiopharmaceuticals are sometimes injected into women whose pregnancies are unknown3, most often during early pregnancy. They can also be voluntarily administered if the procedure carries a clear clinical benefit and cannot be postponed until the end of the pregnancy or replaced by non-irradiating alternatives. In both cases, the fetal risk related to radiation should be known in order to reach an informed clinical decision and to appropriately counsel the patient4. The nuclear medicine examinations most likely to be voluntarily performed in pregnant women are lung scans to diagnose pulmonary embolism and 8F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) scans to diagnose and stage cancers. Pulmonary embolism accounts for 9.2% of all pregnancy-related deaths, or approximately 1.5 deaths per 100,000 live births in the United States5. Cancer in pregnancy remains a rare event—occurring in about 1 in 1000 pregnancies annually—but its incidence is expected to increase due to the worldwide trend in delayed childbearing6. Notably, the four most common cancers in pregnancy—melanoma, breast cancer, cervical cancer, and lymphomas7—are all 18F-FDG-avid cancers, which presents a compelling indication for PET imaging.

The dose of radiation absorbed by the fetus is understandably the most important piece of information needed to assess fetal risk. The total dose is the sum of the fetal self-dose, which depends on the accumulation of the radiopharmaceutical inside the fetal body, and the photon irradiation from the organs of the mother. Therefore, biokinetics in both fetal and maternal tissues must be estimated and used in association with anthropomorphic pregnant phantoms and the Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) formalism8 to calculate the final dose.

Biokinetic data

All internal dosimetry calculations are associated with inherent limitations and uncertainties9, but fetal dosimetry is particularly challenging because of the lack of biokinetic data. Biodistribution in the mother’s tissues can reasonably be assumed to be similar to that of nonpregnant women, and average population values for the mother’s organs are thus readily available for a variety of radiopharmaceuticals10. Biokinetic data in the fetal body, however, can only be measured by images acquired during pregnancy and, for obvious ethical reasons, these images can only be derived from clinical scans in humans or from research scans in animals. Both human and animal data, however, remain exceedingly rare in the literature.

In 1997, Russell and colleagues combed the literature looking for data on placental crossover and found data on 15 single photon emitting radiopharmaceuticals, mostly drawn from animal studies11. By assuming that the percent of activity crossing the placenta in animals was the same as in humans, these biological data were used in association with pregnant phantoms newly-developed by Stabin and colleagues12 to estimate fetal doses in humans. For most radiopharmaceuticals, however, no placental transfer information of any kind was available, and fetal doses were calculated by taking into account only the irradiation from maternal organs13.

In this context, it is important to note that the placenta may actively regulate the accumulation of radiopharmaceuticals in the fetal body14 and could therefore be an important variable influencing fetal dose. For example, glucose—and, by extension, 18F-FDG—accumulates into the placenta for its own metabolic needs and crosses the placenta to reach the fetus thanks to facilitated diffusion transporters of the glucose transporter (GLUT) family, primarily GLUT115, 16. In addition, while some drugs rapidly cross the placenta and equilibrate in maternal and fetal plasma (a situation known as “complete transfer”), other drugs cross the placenta incompletely and their concentrations are lower in fetal than maternal plasma (“incomplete transfer”), and an even smaller number of drugs reach concentrations in fetal plasma that are higher than those in the maternal plasma (“exceeding plasma”)17. With regard to radioactive drugs, the differential accumulation between fetal and maternal tissues would, of course, affect dosimetry.

Importantly, placental exchanges can be studied in vivo by calculating the ratio of fetal-to-maternal drug concentrations in blood and in the umbilical artery after delivery, or by measuring the concentration of the drug in amniotic fluid18. In contrast with PET imaging, however, these approaches only provide a snapshot of the drug repartition and cannot fully describe the kinetics of the radiopharmaceuticals nor their distribution in the different fetal organs. As an example, while PET allows complete description of the kinetics of 11C-methionine into the fetus and its accumulation in the fetal liver of monkeys19, the study of placental transport with 35S-methionine in the same species can only give a cross-sectional picture of the distribution of the amino acid20.

Even when data on placental transfer are available11, limitations linked to extrapolating this information from animals must be considered. The first limitation comes from the fact that animals are typically imaged under anesthesia, which may alter the biodistribution of the radiopharmaceuticals21, 22. Second, placental transfer may differ between animals and humans, as can be inferred by the fact that toxic fetal effects can be species-dependent23, the most famous example is undoubtedly thalidomide24. Placental transfer data in the study by Russell and colleagues11 were largely drawn from biologically distant animals, such as rats, mice, or guinea pigs, and none were from monkeys. Although both primates and rodents have a hemochorial placenta25—that is, the trophoblast is in direct contact with maternal blood—humans and guinea pigs have hemomonochorial placentas—that is, with one trophoblast layer. In addition, rats and mice have hemotrichorial placentas (with three trophoblast layers). Furthermore, the hemochorial placentas of primates are of the villous type while those of rodents (including guinea pigs) are of the labyrinthine type26. These critical anatomical features may cause interspecies differences in placental transfer23.

Being primates, monkeys would of course be a more accurate model for humans. But even in the case of monkeys, species differences in placental transfer may not be negligible; for instance, 80% of rhesus monkeys have two placentas27. Notably, even with the relatively simpler task of estimating standard whole-body dosimetry, large dose differences have been found for the same radiopharmaceutical between monkeys and humans, both in terms of effective dose and organ doses28–31.

Another key point is that in the study by Russell and colleagues11 only one gestational period was often available. In that case, the data were conservatively extrapolated to the other gestational periods by using, for example, the ratio of the weight between animals and women. Although these assumptions were as reasonable as possible at the time, extrapolation to different stages of pregnancy is necessarily associated with some uncertainty. For instance, monkey data showed that the concentration of 18F-FDG is similar in maternal and fetal tissues in late pregnancy18, and this information was assumed to hold true in early pregnancy as well when human standard doses were extrapolated from monkey data32. However, subsequent 18F-FDG human case reports suggested that fetal uptake in early pregnancy, when a rapid growth phase takes place, could be higher than that found in maternal tissues33, 34

Under these circumstances, it is clear that human data drawn from different stages of pregnancy would be preferable for dose estimations. The largest amount of data currently comes from 18F-FDG scans because, along with lung scans, these are virtually the only procedures that are voluntarily performed during pregnancy. Standard 18F-FDG fetal doses were first proposed by Russell and colleagues without placental transfer information13, and then refined by Stabin and colleagues, who extrapolated from monkey data32. The first attempt to quantify fetal 18F-FDG uptake from an actual human scan was published in 200833. This was a case report of a woman with Hodgkin’s lymphoma who was eight weeks pregnant; her pregnancy had been unknown at the time of the PET scan. The case was followed by several others over the years34–38, thus allowing investigators to determine human-based standard values (Table 1)35, 39. It should be noted that all available cases to date consist of a single static image acquired about one hour after injection, even though determining fetal biokinetics requires dynamic data. To obviate this, some (conservative) assumptions must be made, such as considering the physical decay of 18F as the effective time of 18F-FDG35. While they may slightly overestimate the dose, these assumptions should not be a significant source of error, especially considering the overall uncertainties in fetal dose estimates. It is likely that dose estimates will be further refined when future dynamic data become available.

Table 1.

Standard dose values (mGy/MBq) for 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) in the fetus, estimated with different biokinetic data. For comparative purposes, all values reported in this table are estimated using the same pregnant anthropomorphic phantoms12. Different results, but within the same order of magnitude, were obtained when the same biokinetic data were used with voxel-based anthropomorphic phantoms35, 76.

| Source of fetal 18F-FDG kinetics | Early pregnancy | First trimester | Second trimester | Third trimester | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Only maternal contributions | 2.7E-02 | 1.7E-02 | 9.4E-03 | 8.1E-03 | Russell 199713 |

| Monkeys | 2.2E-02 | 2.2E-02 | 1.7E-02 | 1.7E-02 | Stabin 200432 |

| Humans | 2.3E-02 | 7.5E-03 | 6.3E-03 | 5.5E-03 | Zanotti-Fregonara 201635 |

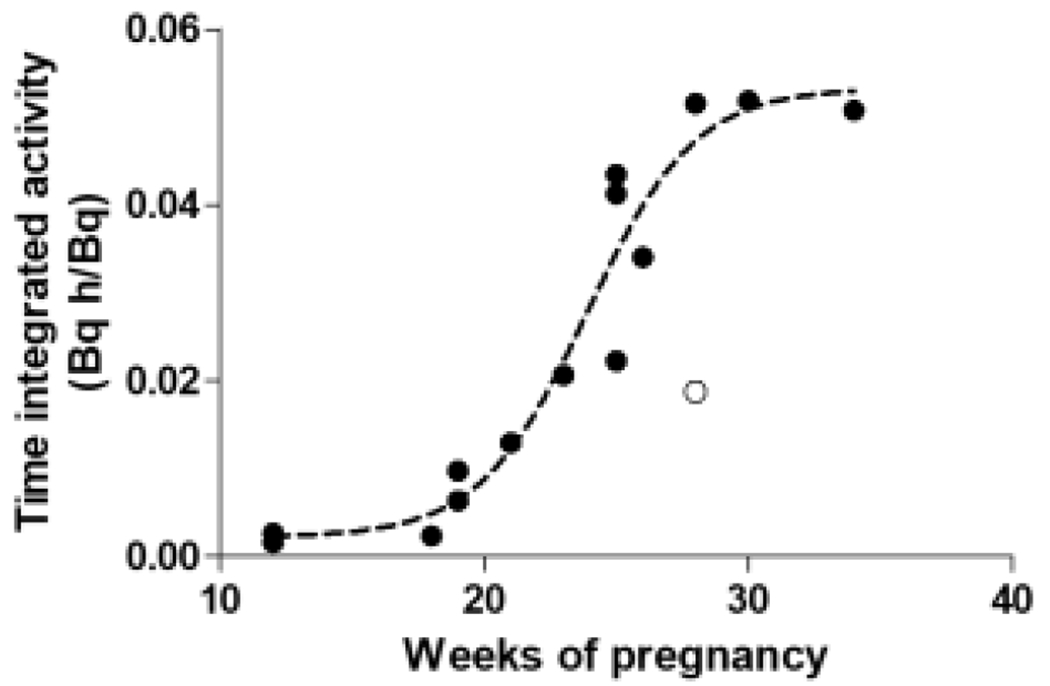

Despite these uncertainties, data from these case reports represented an important step forward compared to the previous values derived from phantoms and animals because they derived from actual (non-anesthetized) humans. Another key point is that the data spanned almost the whole duration of pregnancy, from 5 to 34 weeks, thus providing a more complete picture of the evolution of 18F-FDG uptake through the trimesters. Interestingly, the data showed that fetal 18F-FDG uptake is characterized by three phases: a first phase of slow increase, a second phase starting at about 20 weeks that correspond to the rapid growth of the fetus, and a final plateau towards the end of the pregnancy when the fetus reaches maturity and the fetal mass increases at a much smaller rate (Figure 1). By fitting a logistic function through the datapoints, it becomes possible to extrapolate the doses for the weeks of gestation where cases are not available40. Notably, fetal doses at the very end of the pregnancy (for which data are not yet available) are likely to be less important from a clinical point of view because an 18F-FDG scan can be more easily postponed until the end of the pregnancy or labor can be artificially induced.

Figure 1:

Plotting the fetal time-integrated activity data points calculated in pregnant women injected with 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) shows that fetal uptake follows a sigmoid curve. A mathematical function fitted through the datapoints allows the fetal dose to be interpolated for the weeks of pregnancy for which data are not currently available. Before the 10th week, when the fetus is not clearly visible in the images, the dose to the uterus was used as proxy35. The white point represents an outlying point automatically removed during the fitting process. Figure adapted from40.

In addition to dosimetry data, in vivo human imaging provides a fascinating view into the metabolic development of the fetus. While the heart and the kidneys are well-visualized as soon as they are functional, the fetal brain shows very low metabolism until the very last weeks of pregnancy, especially compared to the mother’s brain35. This finding seems to be mirrored in monkeys; for instance, Benveniste and colleagues reported that the maternal brain-to-myocardial SUV ratio in anesthetized macaques was 45% higher than the fetal brain-to-myocardial SUV ratio18.

For radiopharmaceuticals predominantly excreted through the urines, like 18F-FDG, the maternal bladder is the main contributor of photon dose to the fetus. In this context, the amount of activity in the bladder, and the voiding parameters in the phantom simulation, affect the final fetal dose to a large extent. For instance, the 18F-FDG dose to the fetus from maternal organs—as extrapolated from monkeys—would increase by 20-35% if maternal voiding was simulated at four hours instead of at two hours32. In human data, the dose to the fetus in early pregnancy can almost be halved by early voiding36, 38. Because bladder voiding has such an outsized effect on the final fetal dose, fetal estimates across different studies can be appropriately compared only if the photon irradiation from the mother is kept constant. Indeed, when new reference values were established by reanalyzing 17 cases of 18F-FDG in pregnancy35, the irradiation from the mothers’ organs was taken from the standard 18F-FDG values reported in the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Publication 10610. In particular, the voiding time was set at one hour in all women because, in clinical practice, 18F-FDG images are started 45-60 minutes after injection, and the patient is usually asked to void the bladder just before image acquisition.

Phantom data

While the estimation of biokinetic data suffers from a dearth of in vivo images, anthropomorphic phantoms to model the distribution of radiation to different tissues and organs have become increasingly more sophisticated and accurate. The first “stylized” phantoms contained simple geometric forms, such as spheres or cylinders, that represented the internal organs. More recently, increased computing power has allowed the creation of more realistic “voxel-based” phantoms whose anatomy derives from morphological imaging data of a representative individual, such as those obtained with MRI or CT. In addition, “hybrid” phantoms can model variations in anatomy and differences in organ size and morphology. Using appropriate affine transformations, the anatomical structures may be modified to match those of any given individual41.

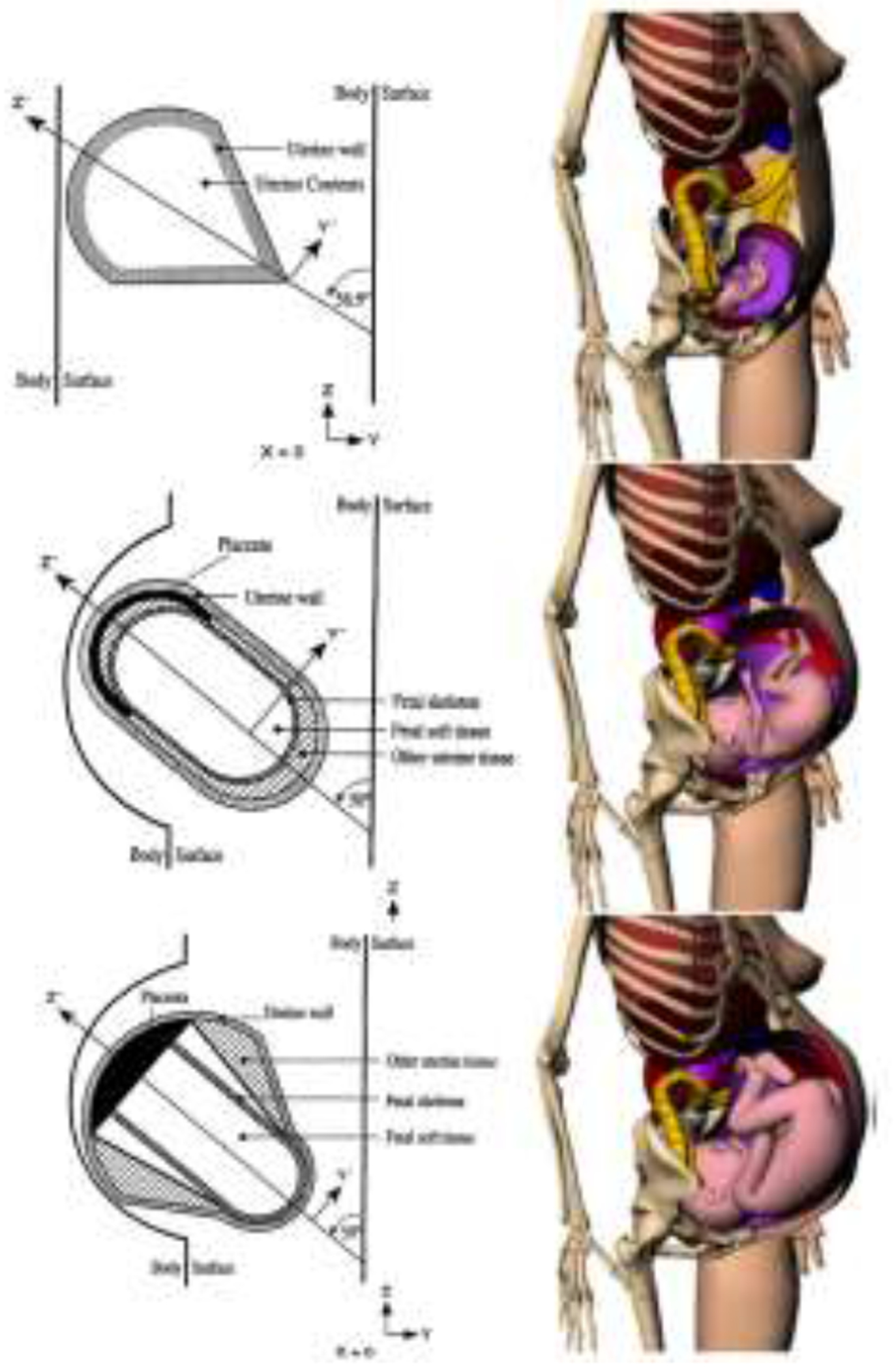

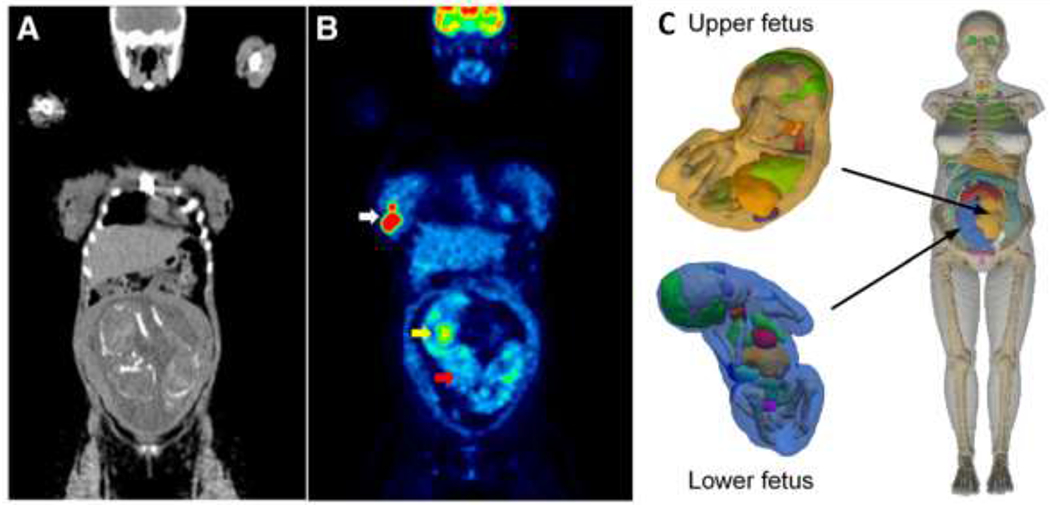

The origin of stylized anthropomorphic phantoms containing specific organs dates back to the 1970s, when Fisher and Snyder created the Reference Man—which was really a hermaphrodite phantom42—and used Monte Carlo codes to calculate the dose absorbed by each target organ as a function of the disintegrations occurring in each source organ. The organs were described by geometric forms and their masses were based on ICRP Publication 2343. Building on this work, Cristy and Eckerman created a series of more sophisticated stylized phantoms in the 1980s, which included an adult man and five children up to 15 years of age, with the 15 year-old child phantom representing the adult female44, 45. The first stylized phantoms modeling pregnant women did not appear until 1995, when Stabin and colleagues created phantoms for the third, sixth, and ninth months of pregnancy, as well as a proper phantom for nonpregnant adult females12. These pregnant phantoms have been the most widely used for internal dose calculations, especially because they were implemented first in the MIRDOSE46 and then in the OLINDA/EXM 1.0 dose calculation software47. More recently, and building on realistic rendering of the human body obtained with b-spline modeling48, Stabin and the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging RAdiation Dose Assessment Resource (RADAR) task force developed a new series of adult, pediatric, and pregnant phantoms49 (Figure 2). These phantoms, which are implemented in the newer version 2.0 of OLINDA/EXM50, provide a more realistic description of the human body, and the mass of their organs was updated with the values recommended by the ICRP Publication 8951. Imaging data of individual patients can be used to create patient-specific phantoms that may be particularly useful for radionuclide therapy, when the radiation doses involved are much higher than in a diagnostic setting, and in those cases marked by significant deviations from normal anatomy. For instance, Xie and colleagues created a personalized phantom from the images of a pregnant patient who underwent an 18F-FDG PET/CT scan while expecting twins and estimated the dose to the two fetuses separately by considering their masses and positions inside the uterus52. In addition, newer phantoms may allow the calculation of the absorbed dose at the level of the fetal organs53.

Figure 2:

Phantoms for the third month (top row), sixth month (middle row), and ninth month (bottom row) of gestation of the stylized phantoms (left column) and the voxel-based phantoms (right column). Reprinted with permission from12, 77.

For diagnostic procedures, the accuracy of the fetal dose could be easily increased by having more pre-defined phantoms covering the whole pregnancy53, 54. Currently-used standard pregnant phantoms, both stylized and voxel-based, have only one phantom and fetal mass per trimester. Thus, although the fetus continuously increases its mass, the fetal mass of the phantoms at each trimester is set at a fixed value12, 49. Not only does this not take into account the mass variations during the trimester or the inter-individual differences in fetal mass, but the estimated fetal dose depends heavily on the phantom that has been used. For instance, when the biokinetic data of 17 pregnant women injected with 18F-FDG were analyzed with both stylized and voxel-based phantoms, the fetal dose was higher with voxel-based phantoms until the second trimester (up to 70%), essentially because of a smaller fetal mass in those phantoms (and also likely because the organs are more densely packed); in contrast, the dose was slightly lower (−8%) in the third trimester due to a slightly higher fetal mass in this voxel-based phantom35. Using personalized phantoms may further alter the dose. For instance, in the pregnant woman expecting twins, the dose to the fetuses estimated with stylized and voxel-based phantoms were about 50% smaller than the doses calculated with a patient-specific phantom52 (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Coronal CT (A) and 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) (B) image of a 25 weeks-pregnant woman diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma while expecting twins. The white arrow points to a lymphoma mass in the right breast. The yellow arrow points to the heart of one of the fetuses, which displays high 18F-FDG uptake, while the brain (red arrow) shows much lower metabolic activity, especially compared to the brain of the mother. This low cerebral metabolic activity is a general finding in fetuses imaged with 18F-FDG. The dose for both fetuses was calculated by creating a patient-specific anthropomorphic phantom (C) based on the CT images which was used as input for Monte Carlo calculations. Details on the construction of the phantom can be found in52. Images reproduced with permission from35, 52.

Risk to the fetus and practical recommendations

Despite the scant biokinetic data available and the variability in dose estimates that may be obtained with different methodological choices, fetal doses can be calculated with an accuracy sufficient to make informed clinical decisions. For example, the dose from 18F-FDG is variably estimated between 0.5 and 3.0E-02 mGy/MBq, depending on the stage of pregnancy and the specific phantom used (Table 1). This means that after an injection of a typical activity of 250 MBq to the mother, the fetus would receive a dose in the range of 1.25-7.5 mGy. If adding the dose of the CT scan for a PET/CT machine, the total dose may be higher than 10 mGy and may rise as high as 20 mGy in some cases55. Lung scans—the other nuclear medicine procedure most likely to be performed in pregnant women—are associated with much lower doses. A ventilation scan performed with 20-40 MBq of 99mTc-DTPA aerosol delivers a dose to the fetus in the range of 0.046 to 0.23 mGy, and a perfusion scan performed with 40-150 MBq of 99mTc-MAA delivers a dose of 0.11-0.75 mGy56. Even if the small additional dose associated with the scattered photons of the lung CT scan57 is added (if the scan is performed on a hybrid SPECT machine), the dose would not exceed 1.5-2 mGy. This dose would be even lower if the ventilation scan is performed with 81mKr56.

Radiopharmaceuticals other than 18F-FDG and lung imaging agents are likely to be used only in cases of unrecognized pregnancy and, therefore, human-based dosimetry values are virtually nonexistent. However, given that the phantom simulations of Russell and colleagues 13 accurately predicted the 18F-FDG dose that was subsequently measured in humans (Table 1), one can assume that also the other dose estimations reported in that paper are reasonably accurate, at least at the level of the order of magnitude. Among the radiopharmaceuticals reported by Russell and colleagues13, most would deliver a dose <10 mGy for the range of activities commonly injected in clinical practice. The fetal dose would be higher than 10 mGy only for studies with 67Ga citrate, 99mTc-labeled red blood cells, 201T1 chloride, or 131I-sodium iodide. Notably, since Russell and colleagues first published their paper in the 1990s 13, the use of the first three of these radiopharmaceuticals in clinical practice has declined considerably, though 131I-sodium iodide is still widely used to treat hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer58. Given the small size of the fetal thyroid, 131I could easily reach ablative doses if given after the fetal thyroid starts developing at about 10 weeks of gestation. Indeed, administration of just 1 MBq of 131I may deliver a dose of about 230 mGy to the fetal thyroid in the third month of gestation and 580 mGy at the fifth month39.

However, barring the danger of very high specific organ doses such as those delivered by thyroid-seeking agents, it is reasonable to expect that fetal doses from diagnostic radiopharmaceuticals will not exceed 20 mGy, a dose that is well below the threshold for deterministic effects4, 59, 60. Doses from radiopharmaceuticals are generally highest in early pregnancy, and the third and fourth weeks of gestation are the most sensitive period for the induction of embryonic death4. Even within this window, however, the minimum human acute lethal dose is estimated to be at least 100-200 mGy. For the remainder of early pregnancy until about the eighth week, major malformations and growth retardation appear after a threshold of 200 mGy. In later stages of gestation, the threshold for deterministic effects increases, and the average absorbed dose per unit of injected activity decreases13. Furthermore, no measurable increase in risk for stochastic effects—such as cancer induction—are observed at typical diagnostic doses59. A study on atomic bomb survivors exposed in utero or in early childhood not only found no statistically significant increase in cancer risk after in utero exposure of less than 200 mGy, but the population exposed in utero was considerably less sensitive to cancer induction than those who were exposed as children61. However, because stochastic effects do not require a threshold, detrimental effects cannot be completely ruled out even if their incidence may be so low as to be invisible in even the largest epidemiological studies. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that pregnant women are injected with radiopharmaceuticals for medical reasons, and any small future theoretical risk to the fetus must be evaluated against the immediate clinical benefit for both mother and the fetus. Opinions differ on what constitutes an acceptable cost-benefit ratio. Papers published by The Lancet explicitly discouraged the use of 18F-FDG in pregnant women with gynecological and hematological cancers62, 63, but such a radical stance is uncommon in the field, where most authors and scientific organizations recognize that clinically justified PET scans should be performed64–66. More often, the necessity of performing the examination is not in question; rather, dose-optimization recommendations specific to pregnant women are made. Arguably, these recommendations sometimes tend to overweigh the radiation risk67. For instance, despite the measurable risk of death from pulmonary embolism5, the guidelines for lung scintigraphy issued by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging recommend that the lung scan should be performed over two days, with the ventilation scan on the second day only if the perfusion scan is positive68. By using this two-day protocol, Bajc and colleagues had to scan 13 of 27 pregnant women on the second day 69. This means that, in order to avoid an examination that delivers 0.006 mGy/MBq56, half of the patients were kept an additional day without a definitive diagnosis and, among the five patients finally diagnosed with embolism, diagnosis was delayed in four.

A lower fetal dose might be achieved by injecting a lower activity, but if a lower activity yields images of comparable quality, then the dose should be lowered for all individuals and pregnant women should not be treated differently. If the images are not comparable, the health detriment from the loss of sensitivity and specificity of the examination should be compared to the hypothetical future health risk to the fetus induced by radiation. Although it is possible to compensate for lower activity with a longer acquisition time, the loss in image quality due to additional movement should be quantified. Given how small the radiation risk to the fetus is, it seems reasonable that preference should be given to acquiring images of good clinical quality. It should be remembered that about 5% of abdominal CT scans in children, for whom protocols of dose reduction are aggressively implemented70, may be nondiagnostic because of excessive radiation dose reduction71, 72.

Drinking water to favor bladder voiding is the most effective single procedure for reducing fetal dose post-injection without decreasing imaging quality36, 38. This common-sense advice—which should be given to all patients—is particularly important for pregnant women because the bladder is the single largest maternal contributor to the fetal dose for many radiopharmaceuticals. However, inserting a bladder catheter that continuously drains the bladder, which some case reports in the literature describe doing, should be discouraged because it increases the risk of a potentially serious urinary infection73.

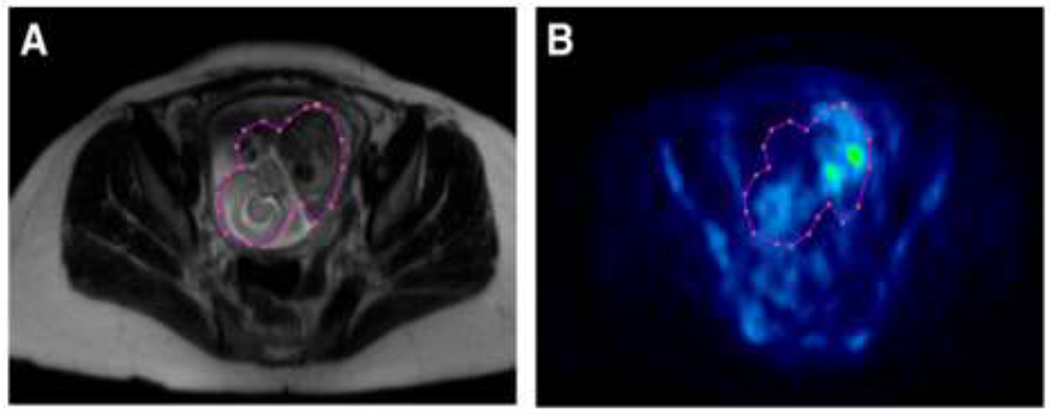

If available, PET/MRI machines should be used to image pregnant women. Not only can the dose contribution from a CT scan can be avoided with these machines, but detailed visualization of the fetus allows a more accurate retrospective dose estimation (Figure 4). In addition, new PET scans with a longer axial field of view have much higher sensitivity, which allows lower activities to be used without image quality loss74, as was recently demonstrated in a pediatric setting75. Notably, these new scanners allow the acquisition of fast dynamics that not only allow investigators to obtain high-quality dosimetric data but also calculate the metabolic rate of glucose in various fetal tissues in vivo by using the 18F-FDG blood time-activity curve as an image-derived input function.

Figure 4:

Magnetic resonance (MR) (A) and 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) (B) transaxial slices of a 19 weeks-pregnant woman with lymphoma scanned with a PET/MRI machine. The images clearly illustrate how PET/MRI allows superior delineation of the fetal body. Indeed, the region of interest around the fetus encompasses some cold areas that would not have been included if a coregistered MRI had not been available. In consequence, it can reasonably be assumed that dosimetry estimates obtained with PET/MRI are more accurate than those obtained with PET only or even with PET/CT machines. Reprinted with permission from36.

Summary

Many uncertainties surround the calculation of fetal dose from administration of radiopharmaceuticals to pregnant women. These uncertainties come from the lack of human biokinetic data for virtually all radiopharmaceuticals, including those used in pregnancy for clinical reasons, essentially lung scan agents and 18F-FDG. Moreover, methodological choices such as the use of particular anthropomorphic phantoms and the modeling of bladder contents may add considerable variability to the final fetal dose.

Nevertheless, existing data allow a range of doses to be calculated with a degree of accuracy that suffices for making informed clinical choices. Current dose estimates show that clinically justified nuclear medicine procedures should be performed in pregnant women because the immediate benefit for both the mother and the fetus clearly outweighs the small hypothetical risk to the fetus related to radiation. Furthermore, fetal radiation doses can be reduced without compromising image quality by encouraging bladder voiding and by using, if available, modern PET/MRI machines or PET/CT machines with longer axial field of view and higher sensitivity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Stabin for useful comments and Ioline Henter for her invaluable editorial assistance.

Financial Disclosure

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health (project number ZIAMH002852).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Grigoryan A, Bouyoucef S, Sathekge M, et al. Development of nuclear medicine in Africa. Clinical and translational imaging. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.IMV 2020. PET Imaging Market Summary Report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shao F, Chen Y, Huang Z, Cai L, Zhang Y. Unexpected Pregnancy Revealed on 18F-NaF PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2016;41:e202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent RL. Saving lives and changing family histories: appropriate counseling of pregnant women and men and women of reproductive age, concerning the risk of diagnostic radiation exposures during and before pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:4–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abe K, Kuklina EV, Hooper WC, Callaghan WM. Venous thromboembolism as a cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Semin Perinatol. 2019;43:200–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hepner A, Negrini D, Hase EA, et al. Cancer During Pregnancy: The Oncologist Overview. World J Oncol. 2019;10:28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pavlidis NA. Coexistence of pregnancy and malignancy. Oncologist. 2002;7:279–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loevinger R, Budinger TF, Watson EE. MIRD primer for absorbed dose calculations. New York: The Society of Nuclear Medicine; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stabin MG. Uncertainties in internal dose calculations for radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:853–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). ICRP Publication 106: Radiation Dose to Patients from Radiopharmaceuticals - Addendum 3 to ICRP Publication 53. Ann. ICRP 2008;38 (1-2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell JR, Stabin MG, Sparks RB. Placental transfer of radiopharmaceuticals and dosimetry in pregnancy. Health Phys. 1997;73:747–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stabin M, Watson E, Cristy M, et al. Mathematical Models and Specific Absorbed Fractions of Photon Energy in the Nonpregnant Adult Female and at the End of Each Trimester of Pregnancy. ORNL Report ORNL/TM-12907. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell JR, Stabin MG, Sparks RB, Watson E. Radiation absorbed dose to the embryo/fetus from radiopharmaceuticals. Health Phys. 1997;73:756–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffiths SK, Campbell JP. Placental structure, function and drug transfer. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 2014;15:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Illsley NP, Baumann MU. Human placental glucose transport in fetoplacental growth and metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2020;1866:165359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Jan S, Champion C, et al. In vivo quantification of 18f-fdg uptake in human placenta during early pregnancy. Health Phys. 2009;97:82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacifici GM, Nottoli R. Placental transfer of drugs administered to the mother. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1995;28:235–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benveniste H, Fowler JS, Rooney WD, et al. Maternal-fetal in vivo imaging: a combined PET and MRI study. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:1522–1530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berglund L, Halldin C, Lilja A, et al. 11C-methionine kinetics in pregnant rhesus monkeys studied by positron emission tomography: a new approach to feto-maternal metabolism. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63:641–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sturman JA, Niemann WH, Gaull GE. Metabolism of 35S-Methionine and 35S-Cystine in the Pregnant Rhesus Monkey. Neonatology. 1973;22:16–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Itoh T, Abe K, Hong J, et al. Effects of cAMP-dependent protein kinase activator and inhibitor on in vivo rolipram binding to phosphodiesterase 4 in conscious rats. Synapse. 2010;64:172–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hines CS, Fujita M, Zoghbi SS, et al. Propofol decreases in vivo binding of 11C-PBR28 to translocator protein (18 kDa) in the human brain. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt A, Schmidt A, Markert UR. The road (not) taken - Placental transfer and interspecies differences. Placenta. 2021;115:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fratta ID, Sigg EB, Maiorana K. TERATOGENIC EFFECTS OF THALIDOMIDE IN RABBITS, RATS, HAMSTERS, AND MICE. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1965;7:268–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soares MJ, Varberg KM, Iqbal K. Hemochorial placentation: development, function, and adaptations†. Biology of Reproduction. 2018;99:196–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carter AM. Animal Models of Human Placentation – A Review. Placenta. 2007;28:S41–S47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myers RE. The gross pathology of the rhesus monkey placenta. J Reprod Med. 1972;9:171–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Innis RB. Suggested pathway to assess radiation safety of 11 C-labeled PET tracers for first-in-human studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2012;39:544–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Lammertsma AA, Innis RB. Suggested pathway to assess radiation safety of 18 F-labeled PET tracers for first-in-human studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2013;40:1781–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Lammertsma AA, Innis RB. (11)C Dosimetry Scans Should Be Abandoned. J Nucl Med. 2021;62:158–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Aart J, Hallett WA, Rabiner EA, Passchier J, Comley RA. Radiation dose estimates for carbon-11-labelled PET tracers. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39:305–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stabin MG. Proposed addendum to previously published fetal dose estimate tables for 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:634–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Champion C, Trebossen R, Maroy R, Devaux JY, Hindie E. Estimation of the beta+ dose to the embryo resulting from 18F-FDG administration during early pregnancy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Jan S, Taieb D, et al. Absorbed 18F-FDG dose to the fetus during early pregnancy. J Nucl Med. 2010;51:803–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Chastan M, Edet-Sanson A, et al. New Fetal Dose Estimates from 18F-FDG Administered During Pregnancy: Standardization of Dose Calculations and Estimations with Voxel-Based Anthropomorphic Phantoms. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1760–1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Laforest R, Wallis JW. Fetal Radiation Dose from 18F-FDG in Pregnant Patients Imaged with PET, PET/CT, and PET/MR. J Nucl Med. 2015;56:1218–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Koroscil TM, Mantil J, Satter M. Radiation dose to the fetus from [18F]-FDG administration during the second trimester of pregnancy. Health Phys. 2012;102:217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takalkar AM, Khandelwal A, Lokitz S, Lilien DL, Stabin MG. 18F-FDG PET in pregnancy and fetal radiation dose estimates. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stabin MG. Radiation dose and risks to fetus from nuclear medicine procedures. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology: official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB). 2017;43:190–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Stabin MG. New Fetal Radiation Doses for (18)F-FDG Based on Human Data. J Nucl Med. 2017;58:1865–1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McParland BJ. Nuclear Medicine Radiation Dosimetry. Advanced Theoretical Principles. Ed Springer. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snyder WS. Report of the Task Group on Reference Man. ICRP PUBLICATION. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Report of the task group on reference man ICRP Publication 23 (1975). Annals of the ICRP. 1980;4:III–III. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cristy M Mathematical phantoms representing children of various ages for use in estimates of internal dose. United States1980:Medium: X; Size: Pages: 112. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cristy M, Eckerman KF. Specific Absorbed Fractions of Energy at Various Ages from Internal Photon Sources. Oak Ridge, TN: Oak Ridge National Laboratory. 1987:1–110, ORNL/TM-8381. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stabin MG. MIRDOSE: personal computer software for internal dose assessment in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:538–546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stabin MG, Sparks RB, Crowe E. OLINDA/EXM: the second-generation personal computer software for internal dose assessment in nuclear medicine. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1023–1027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Segars J Development and Application of the New Dynamic NURBS-Based Cardiac-Torso (NCAT) Phantom [dissertation]. University of North Carolina. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stabin MG, Xu XG, Emmons MA, Segars WP, Shi C, Fernald MJ. RADAR reference adult, pediatric, and pregnant female phantom series for internal and external dosimetry. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:1807–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stabin M, Farmer A. OLINDA/EXM 2.0: The new generation dosimetry modeling code. J. Nucl. Med 2012;53:585–585. [Google Scholar]

- 51.International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP). ICRP Publication 89: Basic Anatomical and Physiological Data for Use in Radiological Protection: Reference Values. New York, NY: Elsevier Health. 2003:1–265. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie T, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Edet-Sanson A, Zaidi H. Patient-Specific Computational Model and Dosimetry Calculations for PET/CT of a Patient Pregnant with Twins. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1451–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie T, Zaidi H. Development of computational pregnant female and fetus models and assessment of radiation dose from positron-emitting tracers. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2016;43:2290–2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bibin L, Anquez J, de la Plata Alcalde JP, Boubekeur T, Angelini ED, Bloch I Whole-body pregnant woman modeling by digital geometry processing with detailed uterofetal unit based on medical images. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2010;57:2346–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Angel E, Wellnitz CV, Goodsitt MM, et al. Radiation dose to the fetus for pregnant patients undergoing multidetector CT imaging: Monte Carlo simulations estimating fetal dose for a range of gestational age and patient size. Radiology. 2008;249:220–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker JA, Coleman RE, Grady E, et al. SNM practice guideline for lung scintigraphy 4.0. Journal of nuclear medicine technology. 2012;40:57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Niemann T, Nicolas G, Roser HW, Müller-Brand J, Bongartz G. Imaging for suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy-what about the fetal dose? A comprehensive review of the literature. Insights Imaging. 2010;1:361–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindie E, Faugeron I, et al. Update on the diagnosis and therapy of distant metastases of differentiated thyroid carcinoma. Minerva Endocrinol. 2008;33:313–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brent RL. Protection of the gametes embryo/fetus from prenatal radiation exposure. Health Phys. 2015;108:242–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindie E. Performing nuclear medicine examinations in pregnant women. Physica medica : PM : an international journal devoted to the applications of physics to medicine and biology : official journal of the Italian Association of Biomedical Physics (AIFB). 2017;43:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Preston DL, Cullings H, Suyama A, et al. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors exposed in utero or as young children. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2008;100:428–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brenner B, Avivi I, Lishner M. Haematological cancers in pregnancy. Lancet. 2012;379:580–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Morice P, Uzan C, Gouy S, Verschraegen C, Haie-Meder C. Gynaecological cancers in pregnancy. Lancet. 2012;379:558–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.International Commission on Radiological Protection; Pregnancy and Medical Radiation; ICRP Publication 84. Ann. ICRP 30. 2000;1. [Google Scholar]

- 65.https://www.iaea.org/resources/rpop/health-professionals/nuclear-medicine/pregnant-women#3. Accessed November 19th 2021.

- 66.Zanotti-Fregonara P Pregnancy should not rule out (18)FDG PET/CT for women with cancer. Lancet. 2012;379:1948–1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindie E. Linear No-Threshold Hypothesis at the Hospital: When Radioprotection Becomes a Nosocomial Hazard. J. Nucl. Med. 2017;58:1355–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bajc M, Neilly JB, Miniati M, et al. EANM guidelines for ventilation/perfusion scintigraphy : Part 1. Pulmonary imaging with ventilation/perfusion single photon emission tomography. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2009;36:1356–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bajc M, Olsson B, Gottsater A, Hindorf C, Jogi J. V/P SPECT as a diagnostic tool for pregnant women with suspected pulmonary embolism. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1325–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen MD. Point: Should the ALARA Concept and Image Gently Campaign Be Terminated? J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:1195–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goske MJ, Strauss KJ, Coombs LP, et al. Diagnostic reference ranges for pediatric abdominal CT. Radiology. 2013;268:208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brody AS, Guillerman RP. Don’t let radiation scare trump patient care: 10 ways you can harm your patients by fear of radiation-induced cancer from diagnostic imaging. Thorax. 2014;69:782–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilstrap LC 3rd, Ramin SM. Urinary tract infections during pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 2001;28:581–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vandenberghe S, Moskal P, Karp JS. State of the art in total body PET. EJNMMI Physics. 2020;7:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dickson J, Eberlein U, Lassmann M. The effect of modern PET technology and techniques on the EANM paediatric dosage card. Eur J Nucl Med Mol I. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stabin MG. New-Generation Fetal Dose Estimates for Radiopharmaceuticals. J Nucl Med. 2018;59:1005–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xu XG, Taranenko V, Zhang J, Shi C. A boundary-representation method for designing whole-body radiation dosimetry models: pregnant females at the ends of three gestational periods--RPI-P3, -P6 and -P9. Phys Med Biol. 2007;52:7023–7044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]