Abstract

Background:

Psychotherapy non-completion rates for veterans and their families are high. This study sought to 1) measure non-completion rates of such patients at a university-based treatment center, 2) compare veteran and family member attrition rates, 3) identify dropout predictors, and 4) explore clinicians’ perspectives on treatment non-completion.

Methods:

Using quantitative and qualitative approaches, we analyzed demographic and clinical characteristics of 141 patients (90 military veterans; 51 family members) in a university treatment center. We defined dropout as not completing the time-limited therapy contract. Reviewing semi-structured interview data assessing clinicians’ perspectives on their patients’ dropout, three independent raters agreed on key themes, with interrater coefficient kappa range 0.74 to 1.

Results:

Patient attrition was 24%, not differing significantly between veterans and family members. Diagnosis of major depression (MDD) and exposure-based therapies predicted non-completion, as did higher baseline Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) total scores, severe depression (HDRS>20), lack of Beck Depression Inventory weekly improvement, and history of military sexual trauma. Clinicians mostly attributed non-completion to patient difficulties coping with intense emotions, especially in exposure-based therapies.

Conclusion:

Non-completion rate at this study appeared relatively low compared to other veteran-based treatment centers, if still unfortunately substantial. Patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD and exposure-based therapies carried greater non-completion risk due to the MDD component, and this should be considered in treatment planning. Ongoing discussion of dissatisfaction and patient discontinuation, in the context of a strong therapeutic alliance, might reduce non-completion in this at-risk population.

Keywords: Dropout, Non-completion, PTSD, Depression, Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Prolonged Exposure, Veterans

Introduction

Veterans who initiate outpatient treatment have distressingly high dropout rates across settings and diagnoses (mean 42%, range 36–68%) (Fischer et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2011; Goetter et al., 2015; Steenkamp & Litz, 2013). In comparison, a recent meta-analysis found only 19.7% dropout for the general adult population, with 18.3% for manualized, time-limited treatments (Leichsenring et al., 2019; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Recent meta-analyses have shown that patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) alone had a higher dropout rate (22–30%) than major depressive disorder (MDD) alone (17.5%) (Cooper & Conklin, 2015; Lewis et al., 2020). The use of exposure-based therapy may have raised PTSD attrition (Berke et al. 2019). Our previous randomized controlled trial (RCT) found that patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD, when randomly assigned to exposure-based therapy, dropped out nine times more than non-depressed exposure-based patients, and than patients in non-exposure interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), suggesting that comorbid MDD/PTSD is a risk factor for attrition (Markowitz et al., 2015).

Although veterans’ family members also face high risk for psychopathology (Diehle et al., 2017), almost no research has addressed their treatment. Veterans’ family members, whom veterans’ psychiatric issues often affect (Yager et al., 2016), frequently lack access for treatment services. No studies have examined attrition rates among veterans and their family members nor compared the rates of veterans and family members. Differences in dropout rates may reflect difficulties specific to treating veterans, such as receiving treatment in the same setting that determines their eligibility for disability, and receiving treatment at no cost (Hoge et al., 2014; Kehle-Forbes et al., 2016).

Although “dropout” is an accepted term in outcome research, we have generally substituted “non-completion” in this article in recognition of its potential stigma. Patients have various reasons for not completing treatment, and our goal is to understand rather than to blame. Understanding non-completion is critical for improving treatment outcome in mental health services. Prior studies exploring therapist and patient characteristics influencing attrition have yielded predictors including younger age, lower intelligence, less education, ethnicity (Rizvi, Vogt, & Resick, 2009; Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001), greater symptom severity, disability status, and comorbidities (e.g., psychotic or anxiety disorders, history of traumatic brain injury) (Berke et al. 2019; Fischer et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2011; Gros et al., 2018). Other studies have contradicted these findings (Gros et al., 2013; Olfson et al., 2009; Van Minnen et al., 2002). These mixed findings might partly reflect the definition of treatment non-completion, which has varied across studies: for example, discontinuing treatment against therapist advice before the tenth session, regardless of therapy length (Brogan et al., 1999); failure to meet for a predetermined number of sessions (Beckham, 1992; Gunderson et al., 1989); and not completing the treatment contract (Maher et al., 2010). Psychotherapy type, such as exposure therapy, has also been suggested as possibly predicting non-completion (Kehle-Forbes et al., 2016).

Although prior studies have explored patient perspectives on non-completion, limited research has addressed therapist perspectives. One pilot study (Palmer et al., 2009) found that outpatients with substance use disorder (n=22) and their therapists (n=22) identified similar reasons for non-completion: lack of social supports, staff limitations, connection issues, and readiness to change. Nordheim et al., also studying patients with substance use disorders (n=15), reported that emotion regulation difficulties triggered non-completion (Nordheim et al., 2018). The single study to date investigating attrition of veterans with PTSD from a patient perspective identified therapy-related (Prolonged Exposure [PE] and Cognitive Processing Therapy [CPT]) issues, including viewing treatment as ineffective, weak therapeutic alliance, practical barriers, and high stress levels in treatment (Hundt et al., 2018). Yet interpreting patient accounts of non-completion can be difficult: some patients leave without comment, while others may offer polite excuses, obscuring actual motivations (Clinton, 1996). However, no studies have examined patient or clinician perspectives of veterans’ non-completion from IPT (Pickover et al, 2021).

To assess non-completion rates and their correlates among veterans and their family members, we utilized data collected at a university-based clinical center between January 2016 and March 2020. Quantitative and qualitative methods identified non-completion risk factors to deepen our understanding of treatment non-completion in these populations. Specifically, this study sought to 1) measure non-completion rates of such patients at a university-based treatment center, 2) compare veteran and family member on attrition rates, 3) identify non-completion predictors, and 4) explore clinicians’ perspectives on treatment non-completion. Based on our previous RCT (Markowitz et al., 2015), we expected to find (1) higher non-completion in patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD, and (2) higher non-completion in exposure than in non-exposure therapy. The remaining aims were more exploratory in nature.

Methods

Design and participants

This university-based research center, located in New York City and provides cost-free assessment and treatment to active duty service members, veterans regardless of discharge status, and their first degree family members or partners/spouses (Lowell et al., 2019). The center assesses treatment needs and preferences, provides treatment, and monitors treatment outcome for mood, anxiety, and trauma-related symptoms and disorders. The center accepts patients without Veterans Administration (VA) benefits or who are not interested to seek care at the VA system, and in addition to treatments provided at the VA system, it also provides some treatments (e.g., Interpersonal Psychotherapy for PTSD) that the VA typically does not. All treatments were voluntary as our center does not treat involuntary patients. Patients are recruited via advertisement (Internet, local media, flyers), referrals from community organizations and hospitals, and word-of-mouth.

Of 150 individuals evaluated and found eligible, 141 patients (90 military veterans; 51 family members) began treatment between January 2016 and March 2020. Inclusion criteria were prior or active military service, or 1st degree relatives; age ≥18, significant distress affecting social and/or occupational functioning, ability to sign informed consent, and English fluency. Exclusion criteria were history of psychosis, current unstable bipolar disorder or substance use disorder, antisocial personality disorder, unstable medical condition, and acute suicide or homicide risk.

Ten clinicians (six women, four men) with 12.1 (±9.6, range 2–32) years of experience, treated the 141 patients: one psychiatrist, three Ph.D. psychologists, two Psy.D. postdoctoral fellows, two master’s level doctoral externs, a licensed master’s level social worker, and a nurse practitioner. Traumas included combat or military related, interpersonal violence, childhood physical abuse, childhood sexual abuse, traumatic loss, and terrorism or mass shooting. Intake clinical interview and standardized diagnostic assessments determined eligibility. Ineligible individuals were referred locally. Eligible patients were invited to discuss treatment options and preferences. Following team discussion, patients signed written informed consent and began treatment.

Procedure

Upon obtaining written consent, clinicians discussed with patients the available, appropriate treatment options, both exposure- and non-exposure-based (Markowitz et al., 2015)(Schneier et al., 2012), which included IPT, PE, time-limited Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), CPT, Brief Supportive Psychotherapy (BSP), Emotion Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples, and group CBT for Insomnia (CBT-I), either as monotherapy or combined with pharmacotherapy. Contributing factors included known differential therapeutics, response to previous treatments, the patient’s preference regarding the treatment focus (interpersonal relationship in IPT, trauma exposure in PE), etc. Treatment duration ranged from six (CBT-I) to 14 weekly sessions (IPT for PTSD). We defined dropout as not completing the therapy contract upon which patient and therapist agreed on in their initial meeting prior to signing consent. This definition encompasses non-completers across stages of therapy (Beckham, 1992; Brogan et al., 1999; Gunderson et al., 1989; Leichsenring et al., 2019; Maher et al., 2010; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Following missed sessions, staff members routinely attempted to contact patients by phone and voicemails. Patients who did not reply after two to three weeks were mailed a formal non-completion letter.

Measures

Data were gathered retrospectively from electronic medical records, session notes, intake reports, and the clinical center research database. Clinicians used either the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Research Version (SCID-5-RV) (First et al., 2015) or Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) (Sheehan et al., 1998) for diagnosis. Measures included demographic, Military Sexual Trauma (MST), and the Life Events Checklist (LEC) (F.W Weathers et al., 2013) questionnaires at baseline.

We used the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS-5, Weathers et al., 2018), a 30-item structured interview (range 0–80), for diagnosing DSM-5 PTSD, and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5, Blevins et al., 2015), as a self-report measure for PTSD symptoms. For the diagnosis of depression, we used the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) (HAMILTON, 1960), a 17-item structured interview (range 0–52). A score of 20 or more was considered severe depression. We used the CAPS-5, PCL-5, and HDRS at baseline, mid-, post-treatment, and 3- and 12-month follow-up; Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II, 21-item self-report questionnaire for depression symptoms, range 0–63) (Beck et al., 1996), and Intent to Attend (ITA, a 0–9 patient self-rating of likelihood of attending the next session) scale weekly (Leon et al., 2007). The CAPS-5 and PCL-5 were only repeated after baseline for individuals reporting trauma history.

Data Analysis

Quantitative analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS software, version 26.0. Pearson’s Chi-square tested possible associations between treatment completers/non-completers and demographic characteristics as sex, patient’s status (veteran vs. family member), country of birth, marital status, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, level of education, employment, and level of annual salary. Independent sample t-tests were used to compare mean score differences between treatment completers/non-completers on continues variables as age and baseline clinical measures (CAPS-5 and HDRS). Logistic regressions were used to compare categorical variables as diagnosis, level of depression (HDRS ≥ 20), treatment type, and use of medications between completers and non-completers, accounting for possible confounders. Repeated measure ANOVAs were used to compare BDI-II mean scores (continuous variables) between completers and non-completers. A two-tailed p-value of 0.05 determined statistical significance. For this exploratory study, we did not employ Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Qualitative analysis

Three authors (DA, ALY and YN) developed two semi-structured qualitative interviews. The first, comprising fourteen open-ended and four yes/no questions, assessed clinician perspectives on patient non-completion. The second included nine open-ended questions assessing patient perspectives on non-completion. The first author conducted clinician interviews between September 2018 to March 2020. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three raters independently reviewed the transcriptions for emerging themes, then discussed them and reached agreement on each item (see Table 2). Inter-rater agreement (kappa), calculated separately for each rater dyad, ranged from 0.74 to 1. Due to low compliance (25%) among patients who had dropped out, we decided not to include the data from patient interviews.

Table 2.

Comparison between Treatment Completers (n=107, 76%) and Treatment Dropouts (n=34, 24%) on Clinical Scores, Psychotherapy Type, and Use of Medication

| Item | Completers | Dropouts | Statistica | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical scores | CAPS-5 | 35.14 | 36.33 | 0.52 | 0.60 |

| PCL-5 | 48.62 | 46.00 | 0.61 | 0.55 | |

| HDRS | 14.19 | 18.06 | 2.72 | .007 | |

| HRDS ≥ 20b | 29 (27%) | 17 (50%) | 6.15 | .015 | |

| Psychotherapy | IPT | 78 (80.4) | 19 (19.6) | ||

| PEc | 16 (61.5) | 10 (38.5) | 17.8 | .003 | |

| Otherd | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | |||

| Pharmacotherapy | - | 53 (73.6) | 19 (26.4) | 0.41 | 0.51 |

Note: CAPS-5 scores were included only for people who diagnosed with PSTD.

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD), Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT).

Independent t-test

Pearson Chi-square; Percentage of total score of 20 and above (severe depression) on baseline HDRS scores.

Prolonged Exposure (PE), and Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for couples, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-i) group, and supportive therapy.

Results

Quantitative

Sample Demographic Characteristics

The study sample comprised 90 veterans (64%) and 51 family members (36%). Of the 141 patients, 107 (76%) completed treatment (“completers”) and 34 (24%) did not (“non-completers”). Non-completers attended 4.1 (±3.4) mean sessions (range 1–10). Completers and non-completers did not significantly differ by age, sex, marital status, country of birth, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, or income (Table 1). Although veteran and family member non-completion rates did not significantly differ, veterans were more likely to be male (73 [83%] vs 21 [41%], χ2=25.7, p<.000), non-white (60 [67%] vs 26 [51%], χ2=16.5, p=.035), Hispanic (24 [34%] vs 6 [15%], χ2=5.1, p=0.024), and reportedly heterosexual (66 [93%] vs 31 [76%], χ2=5.4, p=0.04). Veterans and family members did not differ in age, country of origin, marital status, education level, employment, or annual salary. Mean ITA score at last attended session was 8.4 (±1.4) for completers vs. 7.8 (±2.1) for non-completers, indicating all patients reported high motivation to attend the following session. Non-completion by clinician ranged from 18% to 27%, with no significant difference between clinicians.

Table 1.

Demographic Data for Treatment Completers (n=107) and Treatment Dropouts (n=34) groups

| Item | Completers, n (%) | Dropouts, n (%) | χ2 a | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ageb (mean+SD) | 41.9±13.6 | 39.7±12.1 | .799b | 0.43 | |

| Sex | Male | 70 (66.0) | 25 (73.5) | 0.66 | 0.42 |

| Patients Status | Veterans | 67 (62.6) | 23 (67.6) | 2.83 | 0.59 |

| Country of birth | United-States | 71 (78.9) | 22 (75.9) | 3.13 | 0.21 |

| Marital status | Single | 58 (63.5) | 20 (69.0) | 2.30 | 0.89 |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 21 (23.3) | 9 (31.0) | 1.77 | 0.41 |

| Race | White | 42 (56.1) | 12 (52.9) | 8.04 | 0.62 |

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | 75 (83.3) | 22 (75.9) | 5.35 | 0.25 |

| Level of education | College degree or higher | 43 (48.9) | 10 (35.7) | 15.6 | 0.16 |

| Employment | Full or part-time work | 42 (47.7) | 13 (46.4) | 1.96 | 0.96 |

| Annual salary | More than $50K | 42 (47.2) | 10 (39.3) | 14.9 | 0.13 |

Pearson Chi-square.

Independent t-test.

Sample Clinical Characteristics

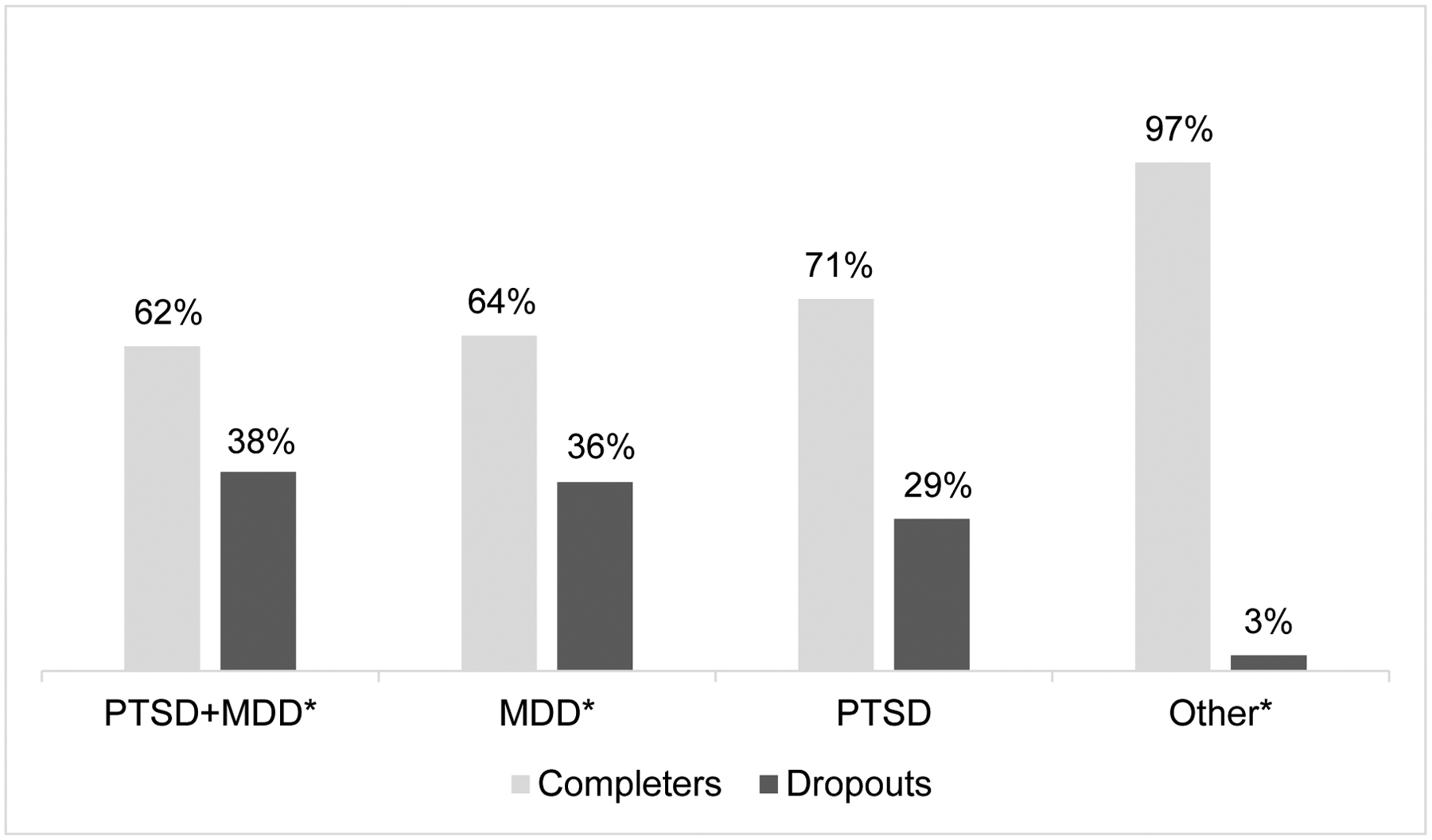

All patients had at least one DSM-5 based diagnosis. Most patients (84%) received diagnoses of either PTSD only (64%), MDD only (65%), or both (45%). Eighty-seven percent (n=123) were treated with IPT or PE. Diagnosis of MDD, either alone (36% attrition) or combined with PTSD (38%) increased non-completion risk, while PTSD diagnosis alone (29%) did not significantly raise non-completion, and patients with neither MDD nor PTSD diagnosis (3%) had lower attrition risk (Figure 1). Furthermore, MDD with or without PTSD predicted non-completion (p=.001, CI [1.87–11.39]). Baseline HDRS total scores and percentage of HDRS>20 (defining severe depression) significantly differentiated completers from non-completers: non-completers were more depressed, with higher rates of severe depression (Table 2). In contrast, PTSD measures (CAPS-5, PCL-5) did not significantly differ between completers and non-completers (Table 2). Psychotherapy type significantly differed between completers and non-completers: patients treated in PE were more likely to drop out. Furthermore, in the subgroup of patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD, PE predicted non-completion (p=.037, CI [1.06–7.55]). Pharmacotherapy use did not significantly differ between completers and non-completers (Table 2). Veterans were more likely to be treated with IPT (67 [76%] vs 30 [59%], p=.032), whereas family members were more likely to be treated in PE (11[13%] vs 15 [29%], p=.014).

Figure 1.

Comparison between Treatment Completers (n=107, 76%) and Treatment Dropouts (n=34, 24%) on Diagnosis

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Other - Persistent Depressive Disorder (PDD), Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD), General Anxiety Disorder (GAD), Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Panic Disorder, Adjustment Disorder, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Substance Use Disorder, Insomnia, Impulse Control Disorder.

* PTSD+MDD (χ2=7.54, p=.006); MDD (χ2=10.95, p=.001); Other (χ2=8.52. p=.004)

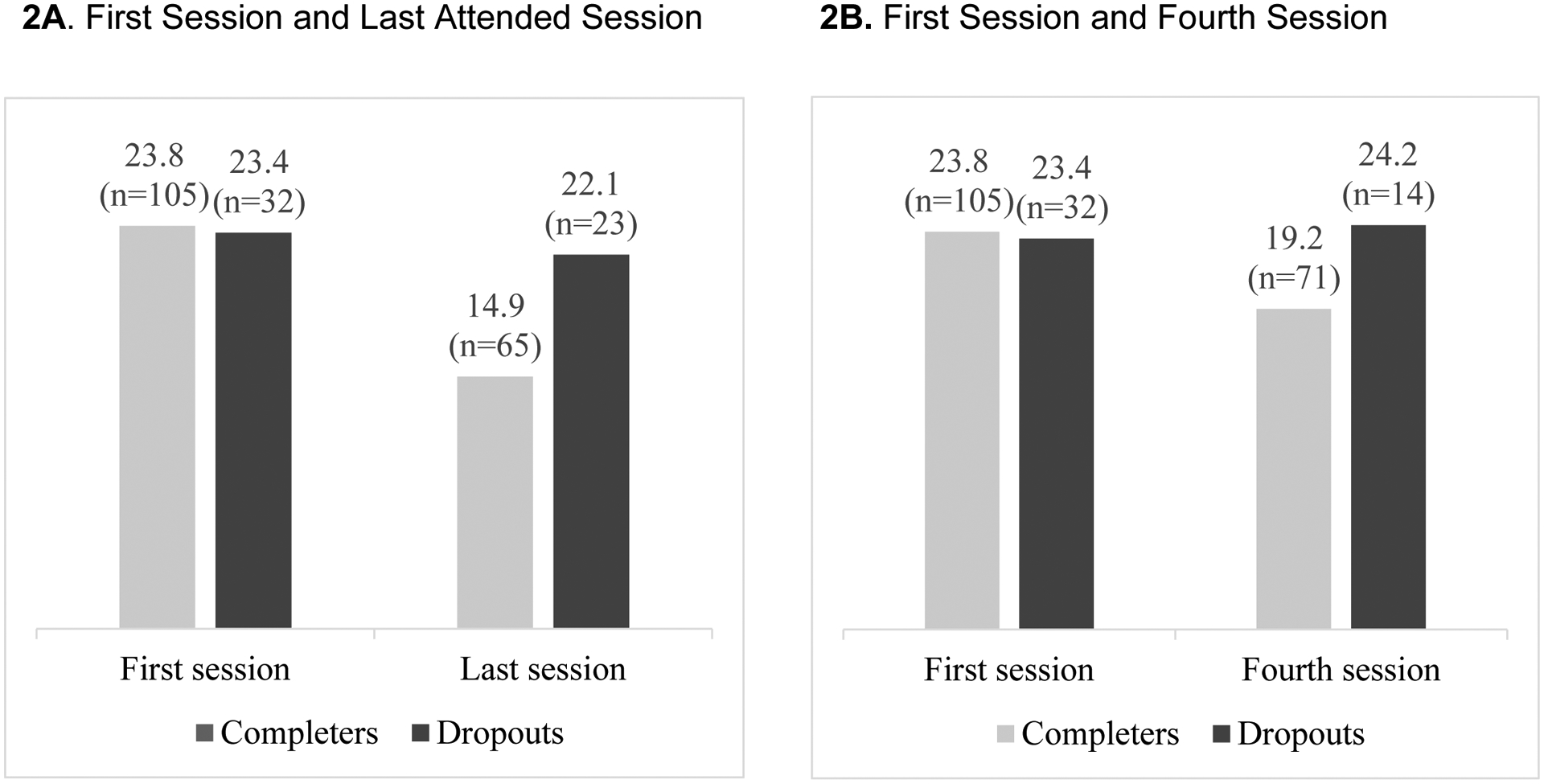

Weekly BDI scores showed a similar completer/ non-completers pattern. Two 2×2 group-by-time ANOVAs were conducted, one comparing the first and last attended session of each group (Figure 2A), the latter using completers’ fourth session as Time 2, as session 4 was the mean final session for dropouts (Figure 2B). The first analysis revealed a significant group by time interaction (F=6.99, p=.010): completers’ BDI scores significantly decreased during treatment, while non-completion scores did not decrease at all. Groups did not differ at baseline (t=0.28, p=.784); non-completers’ last session BDI scores were significantly higher than completers’ last session scores (t=2.28, p=.025). The second ANOVA yielded no significant interaction effect; time showed a significant main effect (F=10.28, p=.002). Completers’ BDI scores significantly decreased at session 4 (t=4.59, p<.001), whereas non-completers’ BDI scores did not decrease (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison between Treatment Completers and Treatment Dropouts on Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

Note: Last session for dropouts was the last therapy session before the patient dropped out of treatment (range 0–10, average of 4.22, mode of 4)

On the MST questionnaire, 39.1% of veteran non-completers reported military sexual trauma, versus 13.4% of veteran completers (χ2=11.93, p=.001). Almost one fifth of veterans (18%; n=15) endorsed experiencing uninvited or unwanted sexual attention or being forced or threatened to engage in sexual contact while in the military, and 60% (n=9) of them dropped out.

Qualitative

Clinicians were asked to describe each dropout patient’s reported reason for prematurely discontinuing treatment. Of the 34 cases, clinicians reported possible reasons for 27 patients. From their own perspective, clinicians reported an external cause as their patients’ self-reported reason for non-completion in 22 of 27 cases (81%): moving out of state, problems commuting to the clinic, and increased life demands or responsibilities. Conversely, in most cases (70%) clinicians also attributed non-completion to an internal, treatment-related cause rather than an external cause. While stratifying by treatment method, in 17 cases (63%), clinicians’ and patients’ attributions for dropout were discrepant. In non-completion during exposure-based therapies (n=10), clinicians indicated an internal reason for 80% (8 of 10) of dropout cases, compared to 53% of IPT cases (10 of 19).

Three thematic reasons for non-completion emerged: difficulty coping with intense emotions, readiness for change, and suitability for outpatient treatment. Therapists in 13 cases explicitly described the intensity of emotions experienced during treatment itself, mostly (n=11) as an outcome of an exposure (see Table 3, quote #1). One clinician described non-completion as an outcome of exposure-related anxiety during CBT treatment (quote #2), while other clinician identified difficulty of coping with emotions aroused during IPT (quote #3). Second, clinicians reported that five patients lacked motivation or readiness to change (quote #4). Third, in four cases clinicians attributed non-completion to the suitability of the clinical center for the patients’ needs, feeling they required a level or type of care beyond what the clinic could offer (quote #5).

Table 3.

Quotes

| First theme, difficulty coping with intense emotions: | |

| 1 |

|

| |

| |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

|

| Second theme, readiness for change: | |

| 4 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Third theme, suitability for outpatient treatment: | |

| 5 |

|

| Role of treatment and communication | |

| 6 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| 7 |

|

| |

| |

| 8 |

|

| |

| 9 |

|

| |

| |

Although most clinicians identified the treatment itself as a possible reason for non-completion, the clinicians nonetheless asserted the chosen treatment was the appropriate treatment for 79% of patients who eventually dropped out, that the selected treatment did not lead to non-completion in 74% of the cases, and that a different treatment would not have changed the course (71%, quote #6). Having affirmed the selected treatment type, 68% of clinicians reported that, in hindsight, they could have acted differently. They emphasized the importance of early detection in eight cases (quote #7). Others described the need to discuss non-completion with the patient (quote #8). Although 87% of patients did not forewarn clinicians of dropout, resulting in no termination session, clinicians reported thinking they had good rapport with 77% of dropouts, and 93% denied a mismatch between themselves and the patient (quote #9).

Discussion

This retrospective study sought to determine rates of, identify predictors of, and describe clinicians’ perspectives on treatment dropout. Twenty-four percent of patients dropped out of treatment, without significant attrition differences between veterans and family members. Non-completion was associated with MDD diagnosis, with or without PTSD. Exposure-based therapies (i.e., PE and CPT) for PTSD were both associated with non-completion and predicted dropout among patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD. Non-completion was associated with higher HDRS scores, severe depression, and lack of BDI improvement during treatment.

Previous research reported a mean 42% dropout rate among veterans receiving clinical care (exposure and non-exposure therapies), rising to 68% for veterans treated for PTSD (Goetter et al., 2015). Our 24% dropout rate, while lower, may also reflect the fact that our university-based center does not accept patients with bipolar disorder, psychotic disorder or substance abuse, diagnoses that often carry higher non-completion rates (Fischer et al., 2018; Garcia et al., 2011; Gros et al., 2018). Veterans have higher non-completion rates than general population patients across diagnoses and settings (Leichsenring et al., 2019; Swift & Greenberg, 2012). Age and ethnicity did not differentiate completers from non-completers, whereas previous research had found younger age and Hispanic ethnicity predicted non-completion in PTSD (for PE and CPT) (Rizvi et al., 2009) and MDD (Karyotaki et al., 2015). Additional prospective research needs to address this clinical concern.

Our findings indicating high dropout (36%) among patients with MDD, and especially those with severe depressive symptoms (41%, HRDS≥20), exceed those reported in a meta-analysis finding 20% overall and 17% IPT dropout rates for MDD (Cooper & Conklin, 2015). Our finding that exposure-based therapies predicted dropout among patients with PTSD accords with previous PE and CBT studies (Goetter et al., 2015; Gros et al., 2018). We found higher attrition in patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD (38%). However, more research is needed to define depression and/or exposure-based therapies as predictors to non-completion.

In a previous trial, we had found IPT had lower dropout and therefore better outcome than PE among patients with comorbid MDD/PTSD (Markowitz et al., 2015). That study randomized treatment regardless of patient preference (Markowitz et al., 2015, 2016), whereas the current non-randomized trial respected patient choice. This corroborates and reinforces the importance of the finding. However, the risk in the comorbid group appeared to stem from the presence of the MDD, rather than PTSD per se. We also found higher MST rates among dropouts. To our knowledge, no prior research has examined the association between MST and treatment dropout, although research has linked MST, child abuse, and suicidal ideation (Bryan et al., 2015; Wilson et al., 2015). The complexity of MDD, PTSD and MST may contribute to elevated dropout rates.

Although family members face elevated psychopathology rates, they do not typically receive free care, and no individual outcome research has assessed their mental health treatment (Johnson et al., 2007; Ramchand et al., 2017; Sheppard et al., 2010). Family member and veteran dropout rates did not significantly differ; family members were more likely to report non-heterosexual orientation and being white. Army regulations like “Don’t ask, don’t tell” (1994–2011) could help explain differences in reported sexual orientation. In addition, we found veterans were more likely to prefer IPT treatment, whereas family members more often preferred PE. One explanation of this finding could be that non-exposure therapies are not frequently offered in VA clinics, leading veterans to seek out our clinic (Lowell et al., 2019). No research has previously compared dropout rates of veterans and family members. Family members of veterans, a high risk but understudied group, warrant treatment research.

Clinicians primarily attributed dropout to general treatment-related factors, yet said their patients mostly cited external causes for dropout. Clinician reports suggested three underlying themes for dropout: difficulty coping with intense emotions (mostly in exposure-based therapies), lack of readiness for change, and unsuitability of the treatment setting. Most clinicians reported good rapport with dropouts and denied a therapist-patient mismatch. Yet, clinicians believed they, in conjunction with patient preference, had employed the appropriate treatment (e.g., IPT, PE, CBT) and that treatment elements specific to those modalities did not account for dropout. Future dropout studies should focus on aspect of communication between the patient and the clinician, around the decision to terminate the treatment, preferably immediately after dropout. Furthermore, future studies should measure the therapeutic alliance to gain deeper understanding of the clinician-patient relationship.

That patients, per clinician reports, mostly attributed dropout to external reasons contradicts a previous qualitative study on veterans’ perspectives of their treatment dropout from exposure-based therapies, which reported therapy-related barriers as the most common reason (Hundt et al., 2018). Some clinicians felt that because treatment was free, patients hesitated to express their discontent, and proffered external reasons to conceal their disappointment. Yet therapy-related barriers such as “too stressful” treatment and not committing to specific therapy tasks were similar to themes in the current study (Hundt et al., 2018). Those themes seem inherent to the diagnoses of PTSD and MDD, which most of our patients met, themes that clinicians would probably have reported for both completers and dropouts. Moreover, most of our clinicians reported good communication with patients and having the appropriate treatment (chosen with the patient), factors known to increase retention and decrease treatment dropout (Gros et al., 2013; Markowitz et al., 2016).

Several study limitations bear mention. First, sample size (N=141) was relatively small and included both veterans and families, who might have different characteristics. Second, in this retrospective, post hoc study, knowing that the patient had dropped out may have influenced clinician accounts. However, dropout is inherently a finding that could be assessed only in hindsight. Third, while clinicians reviewed their intake evaluations and session notes prior to this study, patients had dropped out over the course of the past two years before the interview, also introducing potential recall bias. Future studies should prospectively (or at least, immediately after dropout) compare patient and clinician reports to facilitate deeper understanding of reasons for dropout. Finally, despite our attempts to assess patient views, few responded, precluding understand of patients’ perspectives.

In conclusion, MDD and exposure-based treatment were each associated with dropout. Future studies should further explore risk factors. Most patients did not communicate their intention to leave treatment, and clinicians often failed to predict it. Identifying these risk factors and openly discussing them early in treatment might lower dropout rates. The difficulty of predicting dropout emphasizes the need for deeper understanding predictors (quantitative and qualitative), and for developing strategies to reduce the likelihood of treatment discontinuation. Family members of veterans, and especially minorities, should be encouraged to seek treatment. Future studies should prospectively measure both patients and clinicians’ perspectives regarding dropout.

Clinical Impact Statement.

The findings of this study have the potential to improve clinical care for veterans and family members in a number of ways. For example, providing non-exposure-based interventions to veterans, particularly to depressed patients, may reduce dropouts, and facilitate treatment completion. Furthermore, the findings suggest that openly discussing difficulties to continue treatment among patients who might consider dropping out, may lower dropout rates.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the veterans and their family members who participated in this study.

Funding/support:

The study was supported by a grant by the New York-Presbyterian Hospital (Yuval Neria, PI), Bob Woodruff Foundation (Yuval Neria and Ari Lowell, Co-PIs), Acron Hill Foundation (Yuval Neria, PI), and Stand for the Troops Foundation (Yuval Neria, PI). Benjamin Suarez-Jimenez’s work is supported by grant K01 MH118428-01 from the NIMH. John C Markowitz, Andrea Lopez-Yianilos, Ari Lowell, Alison Pickover, Shay Arnon, Benjamin Suarez-Jimenez and Amit Lazarov work on this project, supported by a grant from the New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

Funding/support:

Supported by grants from the New York-Presbyterian Hospital (Dr. Neria, PI), Stand for the Troops Foundation (Dr. Neria, PI), the Bob Woodruff Foundation (2018- Drs. Neria and Lowell, PIs; 2019- Dr. Neria, PI), Acron Hill Foundation (Dr. Neria, PI). Drs. Neria and Markowitz receive salary support from the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Role of sponsors:

The granting agencies had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or publication of this study.

Footnotes

Previous presentations: None.

References

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Beckham EE (1992). Predicting patient dropout in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy. 10.1037/0033-3204.29.2.177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS, Kline NK, Wachen JS, McLean CP, Yarvis JS, Mintz J, … & STRONG STAR Consortium. (2019). Predictors of attendance and dropout in three randomized controlled trials of PTSD treatment for active duty service members. Behaviour research and therapy, 118, 7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan MM, Prochaska JO, & Prochaska JM (1999). Predicting termination and continuation status in psychotherapy using the transtheoretical model. Psychotherapy. 10.1037/h0087773 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan CJ, Bryan ABO, & Clemans TA (2015). The association of military and premilitary sexual trauma with risk for suicide ideation, plans, and attempts. Psychiatry Research. 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton DN (1996). Why do eating disorder patients drop out? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 10.1159/000289028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper AA, & Conklin LR (2015). Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 57–65. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehle J, Brooks SK, & Greenberg N (2017). Veterans are not the only ones suffering from posttraumatic stress symptoms: what do we know about dependents’ secondary traumatic stress? In Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 10.1007/s00127-016-1292-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Williams JBW, Karg RS, & Spitzer RL (2015). Structured clinical interview for DSM-V research version. In American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer MS, Bhatia V, Baddeley JL, Al-Jabari R, & Libet J (2018). Couple therapy with veterans: Early improvements and predictors of early dropout. Family Process. 10.1111/famp.12308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia HA, Kelley LP, Rentz TO, & Lee S (2011). Pretreatment Predictors of Dropout From Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for PTSD in Iraq and Afghanistan War Veterans. Psychological Services. 10.1037/a0022705 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goetter EM, Bui E, Ojserkis RA, Zakarian RJ, Brendel RW, & Simon NM (2015). A Systematic Review of Dropout From Psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Iraq and Afghanistan Combat Veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 10.1002/jts.22038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Allan NP, Lancaster CL, Szafranski DD, & Acierno R (2018). Predictors of Treatment Discontinuation during Prolonged Exposure for PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 10.1017/S135246581700039X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gros DF, Price M, Yuen EK, & Acierno R (2013). Predictors of completion of exposure therapy in OEF/OIF veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety. 10.1002/da.22207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson JG, Prank AP, Ronningstam EF, Wachter S, Lynch VJ, & Wolf PJ (1989). Early discontinuance of borderline patients from psychotherapy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMILTON M (1960). A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Grossman SH, Auchterlonie JL, Riviere LA, Milliken CS, & Wilk JE (2014). PTSD treatment for soldiers after combat deployment: Low utilization ofmental health care and reasons for dropout. Psychiatric Services. 10.1176/appi.ps.201300307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundt NE, Ecker AH, Thompson K, Helm A, Smith TL, Stanley MA, & Cully JA (2018). “It Didn’t Fit for Me:” A Qualitative Examination of Dropout From Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy in Veterans. Psychological Services. 10.1037/ser0000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson S, Sherman M, & Hoffman J (2007). The Psychological Needs of U. S. Military Service Members and Their Families: A Preliminary Report American Psychological Association Presidental Task Force on Military Deployment Services for Youth, Families and Serice Members. [Google Scholar]

- Karyotaki E, Kleiboer A, Smit F, Turner DT, Pastor AM, Andersson G, Berger T, Botella C, Breton JM, Carlbring P, Christensen H, De Graaf E, Griffiths K, Donker T, Farrer L, Huibers MJH, Lenndin J, Mackinnon A, Meyer B, … Cuijpers P (2015). Predictors of treatment dropout in self-guided web-based interventions for depression: An “individual patient data” meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 10.1017/S0033291715000665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, & Polusny MA (2016). Treatment Initiation and Dropout from Prolonged Exposure and Cognitive Processing Therapy in a VA Outpatient Clinic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 10.1037/tra0000065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leichsenring F, Sarrar L, & Steinert C (2019). Drop-outs in psychotherapy: a change of perspective. In World Psychiatry. 10.1002/wps.20588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Demirtas H, & Hedeker D (2007). Bias reduction with an adjustment for participants’ intent to dropout of a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clinical Trials. 10.1177/1740774507083871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Roberts NP, Gibson S, & Bisson JI (2020). Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1709. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1709709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell A, Lopez-Yianilos A, Ryba M, Arnon S, Suarez-Jimenez B, Lazarov A, Fisher PW, Markowitz JC, & Neria Y (2019). A University-Based Mental Health Center for Veterans and Their Families: Challenges and Opportunities. Psychiatric Services, 70, 159–162. 10.1176/appi.ps.201800356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maher MJ, Huppert JD, Chen H, Duan N, Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, & Simpson HB (2010). Moderators and predictors of response to cognitive-behavioral therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychological Medicine. 10.1017/S0033291710000620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, Meehan KB, Petkova E, Zhao Y, Van Meter PE, Neria Y, Pessin H, & Nazia Y (2016). Treatment preferences of psychotherapy patients with chronic PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 77, 363–370. 10.4088/JCP.14m09640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markowitz JC, Petkova E, Neria Y, Van Meter PE, Zhao Y, Hembree E, Lovell K, Biyanova T, & Marshall RD (2015). Is exposure necessary? A randomized clinical trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for PTSD. American Journal of Psychiatry. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordheim K, Walderhaug E, Alstadius S, Kern-Godal A, Arnevik E, & Duckert F (2018). Young adults’ reasons for dropout from residential substance use disorder treatment. Qualitative Social Work. 10.1177/1473325016654559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Mojtabai R, Sampson NA, Hwang I, Druss B, Wang PS, Wells KB, Pincus HA, & Kessler RC (2009). Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.7.898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer RS, Murphy MK, Piselli A, & Ball SA (2009). Substance user treatment dropout from client and clinician perspectives: A pilot study. Substance Use and Misuse. 10.1080/10826080802495237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickover A, Lowell A, Lazarov A, Lopez-Yianilos A, Sanchez-Lacay A, Ryba M, … & Markowitz JC (2021). Interpersonal psychotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder for veterans and family members: an open trial. Psychiatric services, appi-ps. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramchand R, Tanielian T, Fisher M, Vaughan C, Trail T, Batka C, Voorhies P, Robbins M, Robinson E, & Ghosh Dastidar M (2017). Hidden Heroes: America’s Military Caregivers. In Hidden Heroes: America’s Military Caregivers. 10.7249/rr499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Vogt DS, & Resick PA (2009). Cognitive and affective predictors of treatment outcome in cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lacay JA, Lewis-Fernández R, Goetz D, Blanco C, Salmán E, Davies S, & Liebowitz M (2001). Open trial of nefazodone among hispanics with major depression: Efficacy, tolerability, and adherence issues. Depression and Anxiety. 10.1002/da.1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneier FR, Neria Y, Pavlicova M, Hembree E, Suh EJ, Amsel L, & Marshall RD (2012). Combined prolonged exposure therapy and paroxetine for PTSD related to the World Trade Center attack: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 80–88. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, & Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard SC, Malatras JW, & Israel AC (2010). The impact of deployment on U.S. military families. American Psychologist. 10.1037/a0020332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp MM, & Litz BT (2013). Psychotherapy for military-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Review of the evidence. In Clinical Psychology Review. 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swift JK, & Greenberg RP (2012). Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 10.1037/a0028226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Minnen A, Arntz A, & Keijsers GPJ (2002). Prolonged exposure in patients with chronic PTSD: Predictors of treatment outcome and dropout. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00024-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). National Center for PTSD. 10.1177/1073191104269954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers Frank W., Bovin MJ, Lee DJ, Sloan DM, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM, & Marx BP (2018). The clinician-administered ptsd scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation in military veterans. Psychological Assessment. 10.1037/pas0000486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson LC, Kimbrel NA, Meyer EC, Young KA, & Morissette SB (2015). Do child abuse and maternal care interact to predict military sexual trauma? Journal of Clinical Psychology. 10.1002/jclp.22143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager TJ, Gerszberg N, & Dohrenwend BP (2016). Secondary Traumatization in Vietnam Veterans’ Families. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 10.1002/jts.22115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]