Abstract

Physical activity is a powerful modifiable risk factor for disease and mortality. Physical activity levels in people with spinal cord injury (SCI) have not been quantified relative to uninjured individuals in a large population-based sample. We aimed to quantify and compare physical activity in people with and without SCI, and to examine the associations between physical activity, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors. The 2010 Canadian Community Health Survey (n > 57,000) was used, which includes three measures that assess physical activity levels (i.e., leisure time activity frequency, leisure time activity intensity, and transportation time activity intensity). Bivariable and multivariable logistic regressions were performed and odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated. The odds of physical activity in people with SCI were 0.43 (95% CI 0.3–0.61), 0.53 (95% CI 0.36–0.75), and 0.42 (95% CI 0.28–0.61), across the three measures of physical activity, respectively. These differences persisted after adjustment for lifestyle, comorbidities, and socioeconomic factors. Physical activity is reduced in the SCI population compared with the general population. This knowledge is important to direct future research and guide the allocation of health care resources.

Subject terms: Spinal cord diseases, Physiology

Introduction

Low physical activity is a powerful modifiable risk factor for non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes1–3. Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a devastating neurological condition leading to paralysis of skeletal muscle and autonomic cardiovascular dysfunction, both of which are profound barriers to being physically active4. People with SCI have higher rates of heart disease, stroke, and diabetes2,3. Increasing physical activity levels may be a powerful clinical intervention for preventing these conditions1. Physical activity, exercise, and rehabilitation are health care priorities for people with SCI5. Moreover, increased participation in leisure-time physical activity levels has a positive association with increased quality of life in people with SCI6,7. However, a previous study showed that approximately half of people with SCI report no leisure-time physical activity, and, it is not clear if this is a similar rate as those reported in non-SCI populations8,9. A key step in understanding the potential of increasing leisure-time physical activity on a large scale is to understand the population-level physical activity levels of people with SCI compared to the general population.

Various lifestyle and socioeconomic factors are associated with physical activity in the general population, including income, education level, gender, diet, cigarette smoking, and alcohol consumption10–15. Due to different lifestyles and socioeconomic profiles in the SCI population, the association between these factors and physical activity may be unique in people with SCI16–21. We do not understand the association of various lifestyle and socioeconomic factors with physical activity levels in the SCI population.

We aimed to compare the physical activity level of individuals with and without SCI on a population scale. We also aimed to understand the relationship between lifestyle and socioeconomic factors with physical activity levels in the SCI population. This knowledge is important to direct future research, and potential interventions and educational strategies for people with SCI, to ultimately reduce the development of risk factors that impact long-term health.

Results

Overall sample characteristics

The CCHS was completed by just over 57,000 individuals, of whom 330 self-reported SCI (Table 1). Each physical activity measure of the CCHS was completed by the following number of participants: leisure time activity frequency (n = 57,487); leisure time activity intensity (n = 57,497); transportation time activity intensity (n = 57,096). A similar proportion of males and females completed the survey (Table 1). The overall sample included a similar number of females (49.8%) and males (50.2%), with a median age of 50 to 59 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 26 kg/m2 (Table 1). Sample sizes differed following adjustments to confounders (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the population-based survey by physical activity status.

| Variable | Frequency of all leisure time physical activity lasting over 15 min (PACDFR) | Leisure time physical activity index (PACDPAI) | Transportation and leisure time physical activity index (PACDLTI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 57,487) | Physical activity (n = 46,943) | No physical activity (n = 10,544) | Total sample (n = 57,497) | Physical activity (n = 30,358) | No physical activity (n = 27,139) | Total sample (n = 57,096) | Physical activity (n = 31,054) | No physical activity (n = 26,042) | ||

| Spinal cord injury | ||||||||||

| Yes | 330 (0.47) | 198 (60.8) | 132 (39.2) | 330 (0.47) | 116 (35.5) | 214 (64.5) | 326 (0.44) | 114 (32.0) | 212 (68.0) | |

| No | 57,157 (99.5) | 46,745 (81.8) | 10,412 (18.2) | 57,167 (99.5) | 30,242 (52.8) | 26,925 (47.3) | 56,770 (99.6) | 30,940 (55.0) | 25,830 (45.0) | |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Male | SCI | 202 (0.35) | 125 (0.27) | 77 (0.73) | 202 (0.35) | 73 (0.24) | 129 (0.48) | 199 (0.35) | 71 (0.23) | 128 (0.49) |

| No SCI | 26,275 (45.71) | 21,854 (46.55) | 4,421 (41.92) | 26,285 (45.72) | 14,586 (48.05) | 11,699 (43.11) | 26,067 (45.65) | 14,924 (48.06) | 11,143 (42.79) | |

| Female | SCI | 128 (0.22) | 73 (0.16) | 55 (0.52) | 128 (0.22) | 43 (0.14) | 85 (0.31) | 127 (0.22) | 43 (0.14) | 84 (0.32) |

| No SCI | 30,882 (53.72) | 24,891 (53.02) | 5,991 (56.82) | 30,882 (53.71) | 15,656 (51.57) | 15,226 (56.10) | 30,703 (53.77) | 16,016 (51.57) | 14,687 (56.40) | |

| Median age category (years) | SCI | 55–59 | 55–59 | 52–56 | 55–59 | 55–59 | 55–59 | 55–59 | 55–59 | 55–59 |

| No SCI | 50–54 | 45–49 | 55–59 | 50–54 | 45–49 | 50–54 | 50–54 | 45–49 | 55–59 | |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) | SCI | 26 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 27 |

| No SCI | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 26 | |

SCI spinal cord injury, BMI body mass index.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the population-based survey by physical activity status following adjustments to confounders.

| Variable | Frequency of all leisure time physical activity lasting over 15 min (PACDFR) | Leisure time physical activity index (PACDPAI) | Transportation and leisure time physical activity index (PACDLTI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample (n = 35,666)* | Active (n = 30,385) | Inactive (n = 5,281) | Total sample (n = 35,675)* | Active (n = 20,136) | Inactive (n = 15,539 ) | Total sample (n = 35,437)* | Active (n = 20,643) | Inactive (n = 14,794) | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| Yes | SCI | 126 (0.35) | 72 (0.24) | 54 (1.02) | 74 (0.21) | 46 (0.23) | 80 (0.51) | 125 (0.35) | 45 (0.22) | 80 (0.54) |

| No SCI | 16,296 (45.69) | 13,390 (44.07) | 2906 (55.03) | 16,350 (45.83) | 8505 (42.24) | 7793 (50.15) | 16,222 (45.78) | 8694 (42.12) | 7528 (50.88) | |

| No | SCI | 55 (0.15) | 37 (0.12) | 18 (0.34) | 55 (0.15) | 28 (0.14) | 27 (0.17) | 54 (0.15) | 27 (0.13) | 27 (0.18) |

| No SCI | 19,189 (53.80) | 16,886 (55.57) | 2303 (43.61) | 19,196 (53.81) | 11,557 (57.39) | 7639 (49.16) | 19,036 (53.72) | 11,877 (57.53) | 7159 (48.39) | |

| Hypertension | ||||||||||

| Yes | SCI | 22 (0.06) | 9 (0.03) | 13 (0.25) | 22 (0.06) | 8 (0.04) | 14 (0.09) | 22 (0.06) | 8 (0.04) | 14 (0.09) |

| No SCI | 2311 (6.48) | 1854 (6.10) | 457 (8.65) | 2311 (6.48) | 1199 (5.95) | 1112 (7.16) | 2304 (6.50) | 1219 (5.91) | 1085 (7.33) | |

| No | SCI | 159 (0.45) | 100 (0.33) | 59 (1.12) | 159 (0.45) | 66 (0.33) | 93 (0.60) | 157 (0.44) | 64 (0.31) | 93 (0.63) |

| No SCI | 33,174 (93.01) | 28,422 (9.35) | 4752 (89.99) | 33,183 (93.01) | 18,863 (93.68) | 14,320 (92.16) | 32,954 (92.99) | 19,352 (93.75) | 13,602 (0.09) | |

| Alcohol | ||||||||||

| High | SCI | 125 (0.35) | 78 (0.26) | 47 (0.89) | 125 (0.35) | 55 (0.27) | 70 (0.45) | 124 (0.35) | 54 (0.26) | 70 (0.47) |

| No SCI | 28,128 (78.86) | 24,392 (80.28) | 3736 (70.74) | 28,136 (78.87) | 16,183 (80.37) | 11,953 (76.92) | 27,963 (78.91) | 16,608 (80.45) | 11,355 (76.75) | |

| Low | SCI | 56 (0.16) | 31 (0.10) | 25 (0.47) | 56 (0.16) | 19 (0.09) | 37 (0.24) | 55 (0.16) | 18 (0.09) | 37 (0.25) |

| No SCI | 7357 (20.63) | 5884 (19.36) | 1473 (27.89) | 7358 (20.63) | 3879 (19.26) | 3479 (22.39) | 7295 (20.59) | 3963 (19.20) | 3332 (22.52) | |

| Fruits and vegetables | ||||||||||

| High | SCI | 84 (0.23) | 55 (0.18) | 29 (0.55) | 84 (0.24) | 43 (0.21) | 41 (0.26) | 83 (0.23) | 42 (0.20) | 41 (0.28) |

| No SCI | 18,037 (50.57) | 16,156 (53.17) | 1881 (35.62) | 18,039 (50.56) | 11,747 (58.34) | 6292 (40.49) | 17,891 (50.49) | 11,960 (57.94) | 5931 (40.09) | |

| Low | SCI | 97 (0.27) | 54 (0.18) | 43 (0.81) | 97 (0.27) | 31 (0.15) | 66 (0.42) | 96 (0.27) | 30 (0.15) | 66 (0.45) |

| No SCI | 17,448 (48.92) | 14,120 (46.47) | 3328 (63.02) | 17,455 (48.93) | 8315 (41.29) | 9140 (58.82) | 17,367 (49.01) | 8611 (41.71) | 8756 (59.19) | |

| Income | ||||||||||

| High | SCI | 90 (0.25) | 59 (0.19) | 31 (0.59) | 90 (0.25) | 39 (0.19) | 51 (0.33) | 89 (0.25) | 38 (0.18) | 51 (0.34) |

| No SCI | 25,455 (71.37) | 22,574 (74.29) | 2881 (54.55) | 25,463 (71.37) | 15,315 (76.06) | 10,148 (65.31) | 25,277 (71.33) | 15,670 (75.91) | 9607 (64.94) | |

| Low | SCI | 91 (0.25) | 50 (0.16) | 41 (0.78) | 91 (0.26) | 35 (0.17) | 56 (0.36) | 90 (0.25) | 34 (0.16) | 56 (0.38) |

| No SCI | 10,030 (28.12) | 7702 (25.35) | 2328 (44.08) | 10,031 (28.12) | 4747 (23.57) | 5284 (34.00) | 9981 (28.17) | 4901 (23.74) | 5080 (34.34) | |

| Education | ||||||||||

| High | SCI | 128 (0.36) | 81 (0.27) | 47 (0.89) | 128 (0.36) | 55 (0.27) | 73 (0.47) | 126 (0.36) | 53 (0.26) | 73 (0.49) |

| No SCI | 28,691 (80.44) | 25,172 (82.84) | 3519 (66.63) | 28,699 (80.45) | 16,980 (84.33) | 11,719 (75.42) | 28,502 (80.43) | 17,438 (84.47) | 11,064 (74.79) | |

| Low | SCI | 53 (0.15) | 28 (0.09) | 25 (0.47) | 53 (0.15) | 19 (0.09) | 34 (0.22) | 53 (0.15) | 19 (0.09) | 34 (0.23) |

| No SCI | 6794 (19.05) | 5104 (16.80) | 1690 (32.00) | 6795 (19.05) | 3082 (15.31) | 3713 (23.89) | 6756 (19.06) | 3133 (15.18) | 3623 (24.49) | |

| Self-perceived mental health | ||||||||||

| Good | SCI | 37 (0.10) | 19 (0.06) | 18 (0.34) | 37 (0.10) | 15 (0.07) | 22 (0.14) | 37 (0.10) | 15 (0.07) | 22 (0.15) |

| No SCI | 1799 (5.04) | 1298 (4.27) | 501 (9.49) | 1799 (5.04) | 741 (3.68) | 1058 (6.81) | 1789 (5.04) | 771 (3.73) | 1018 (6.88) | |

| Poor | SCI | 144 (0.40) | 90 (0.30) | 54 (1.02) | 144 (0.40) | 59 (0.29) | 85 (0.55) | 142 (0.40) | 57 (0.28) | 85 (0.57) |

| No SCI | 33,686 (94.45) | 28,978 (95.37) | 4708 (89.15) | 33,695 (94.45) | 19,321 (95.95) | 14,374 (92.50) | 33,469 (94.45) | 19,800 (95.92) | 13,669 (92.40) | |

| Stress | ||||||||||

| High | SCI | 132 (0.37) | 76 (0.25) | 56 (1.06) | 132 (0.37) | 50 (0.25) | 82 (0.53) | 130 (0.37) | 48 (0.23) | 82 (0.55) |

| No SCI | 22,039 (61.79) | 18,754 (61.72) | 3285 (62.20) | 22,044 (61.79) | 7917 (39.32) | 14,127 (90.91) | 21,907 (61.82) | 12,479 (60.45) | 9428 (63.73) | |

| Low | SCI | 49 (0.14) | 33 (0.11) | 16 (0.30) | 49 (0.14) | 24 (0.12) | 25 (0.16) | 49 (0.14) | 24 (0.12) | 25 (0.17) |

| No SCI | 13,446 (37.70) | 11,522 (37.92) | 1924 (36.43) | 13,450 (37.70) | 12,145 (60.31) | 1305 (8.40) | 13,351 (37.68) | 8092 (39.20) | 5259 (35.55) | |

| Migraines | ||||||||||

| Yes | SCI | 44 (0.12) | 23 (0.08) | 21 (0.40) | 44 (0.12) | 16 (0.08) | 28 (0.18) | 43 (0.12) | 15 (0.07) | 28 (0.19) |

| No SCI | 3574 (10.02) | 3001 (9.88) | 573 (10.85) | 3574 (10.02) | 1907 (9.47) | 1667 (10.73) | 3548 (9.96) | 1954 (9.47) | 1594 (10.77) | |

| No | SCI | 137 (0.38) | 86 (0.28) | 51 (0.97) | 137 (0.38) | 58 (0.29) | 79 (0.51) | 136 (0.38) | 57 (0.28) | 79 (0.53) |

| No SCI | 31,911 (89.47) | 27,275 (89.76) | 4636 (87.77) | 31,920 (89.47) | 18,155 (90.16) | 13,765 (88.58) | 31,710 (89.48) | 18,617 (90.19) | 13,093 (88.50) | |

| Mood disorder | ||||||||||

| Yes | SCI | 45 (0.13) | 24 (0.08) | 21 (0.40) | 45 (0.13) | 19 (0.94) | 26 (0.17) | 44 (0.12) | 18 (0.09) | 26 (0.18) |

| No SCI | 2516 (7.54) | 1955 (6.43) | 561 (10.62) | 2516 (7.05) | 1125 (5.59) | 1391 (8.95) | 2502 (7.06) | 1157 (5.60) | 1345 (9.09) | |

| No | SCI | 136 (0.38) | 85 (0.28) | 51 (0.97) | 136 (0.38) | 55 (0.27) | 81 (0.52) | 135 (0.38) | 54 (0.26) | 81 (0.55) |

| No SCI | 32,969 (92.44) | 28,321 (93.21) | 4648 (88.01) | 32,978 (92.44) | 18,937 (94.05) | 14,041 (90.36) | 32,756 (92.43) | 19,414 (94.05) | 13,342 (90.19) | |

| Anxiety disorder | ||||||||||

| Yes | SCI | 29 (0.08) | 16 (0.05) | 13 (0.25) | 29 (0.08) | 13 (0.06) | 16 (0.10) | 29 (0.08) | 13 (0.060 | 16 (0.11) |

| No SCI | 1857 (5.21) | 1466 (4.82) | 391 (7.40) | 1857 (5.21) | 915 (4.54) | 942 (6.06) | 1847 (5.21) | 940 (4.55) | 907 (6.13) | |

| No | SCI | 152 (0.43) | 93 (0.31) | 59 (1.12) | 152 (0.43) | 61 (0.30) | 91 (0.59) | 150 (0.42) | 59 (0.29) | 91 (0.62) |

| No SCI | 33,628 (94.29) | 28,810 (94.82) | 4818 (91.23) | 33,637 (94.29) | 19,147 (0.95) | 14,490 (93.25) | 33,411 (94.28) | 19,631 (95.10) | 13,780 93.15) | |

Data are sample sizes (percentages). Percentages are probability-weighted.

SCI spinal cord injury, BMI body mass index.

*The total sample size of the participants who responded to all the confounding variables.

Individuals with SCI are at greater risk of physical inactivity compared to able-bodied individuals

In individuals with SCI relative to able-bodied individuals, the unadjusted OR for leisure time activity frequency was 0.35 (95% CI 0.27–0.44) (Table 3). After adjusting for age, sex, and BMI the OR slightly increased to 0.39 (95% CI 0.30–0.50) (Table 3). Additionally, even after inclusion of all these variables, the results remained significant (adjusted OR 0.43; 95% CI 0.30–0.61; ROC 0.69). In individuals with SCI relative to able-bodied individuals, the unadjusted OR for leisure time activity intensity was 0.49 (95% CI 0.38–0.63) (Table 3). After adjusting for age, sex, and BMI the OR slightly increased to 0.55 (95% CI 0.43–0.71) (Table 3). Additionally, even after inclusion of all these variables, the results remained significant (adjusted OR 0.53; 95% CI 0.36–0.75; ROC 0.64). In individuals with SCI relative to able-bodied individuals, the unadjusted OR for transportation time activity intensity was 0.38 (95% CI 0.29–0.50) (Table 3). After adjusting for age, sex, and BMI the OR slightly increased to 0.43 (95% CI 0.33–0.57). Additionally, even after inclusion of all these variables, the results remained significant (adjusted OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.28–0.61; ROC 0.65) (Table 3). In other words, all three elements demonstrated converging results that those with SCI participate in less physical activity compared to people without SCI. These results remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, and BMI, as well as including all potential confounders (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 3.

Odds ratios for association between spinal cord injury and physical activity (probability-weighted).

| Frequency of all leisure time physical activity lasting over 15 min | Leisure time physical activity index | Transportation and leisure time physical activity index | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR2 (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR2 (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) | aOR2 (95% CI) | |

| Spinal cord injury | 0.35* (0.27, 0.44) | 0.39* (0.30, 0.50) | 0.43* (0.30, 0.61) | 0.49* (0.38, 0.63) | 0.55* (0.43, 0.71) | 0.53* (0.36, 0.75) | 0.38* (0.29, 0.50) | 0.43* (0.33, 0.57) | 0.42* (0.28, 0.61) |

| No spinal cord injurya | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio.

aReference category. *Statistically significant p < 0.05.

Table 4.

Spinal cord injury status, sex, age, body mass index and comorbidities.

| Variable name | CCHS code | Question | Response values | Combined response values (*reference category) | Excluded responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spinal cord injury status | NEUDSIR | “Do you have a neurological condition caused by a spinal cord injury?” |

1 = “Yes” 2 = “No” (reference category) |

(*2) | 9 = “At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)” |

| Sex | DHH_SEX | Is [respondent name] male or female? |

1 = “Male” 2 = “Female” |

(*2) | N/A |

| Age | DHHGAGE | Questions are described in detail here22 |

1 = “Age between 12 and 14” 2 = “Age between 15 and 17” 3 = “Age between 18 and 19” 4 = “Age between 20 and 24” 5 = “Age between 25 and 29” 6 = “Age between 30 and 34” 7 = “Age between 35 and 39” 8 = “Age between 40 and 44” 9 = “Age between 45 and 49” 10 = “Age between 50 and 54” 11 = “Age between 55 and 59” 12 = “Age between 60 and 64” 13 = “Age between 65 and 69” 14 = “Age between 70 and 74” 15 = “Age between 75 and 79” 16 = “Age 80 and older” |

N/A | N/A |

| Body mass index | HWTGBMI | Questions are described in detail here22 |

14 = Minimum 58 = Maximum Body mass index was categorized into the following groups: normal (18.5–25), overweight (25–30), obese class I (30–35), obese class II (35–40), obese class III (> 40) |

1—less than the median HWTGBMI of all respondents 2—greater or equal to the median HWTGBMI of all respondents (*2) |

N/A = Height and/or weight was not given; Respondent less than 20 or more than 64 years old; or Respondent is pregnant |

| Hypertension | CCC_072 | “Have you ever been diagnosed with high blood pressure?” |

1 = “Yes” 2 = “No” |

(*1) | N/A |

| Migraine | CCC_081 | “Do you have migraine headaches?” |

1 = “Yes” 2 = “No” |

(*1) | N/A |

| Mood disorders | CCC_280 | “Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia?” |

1 = “Yes” 2 = “No” |

(*1) | N/A |

| Anxiety disorders | CCC_290 | “Do you have an anxiety disorder such as phobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder or a panic disorder?” |

1 = “Yes” 2 = “No” |

(*1) | N/A |

CCHS Canadian Community Health Survey.

Table 5.

Lifestyle and socioeconomic factors.

| Variable name | CCHS code | Question | Response values | Combined response values (*reference category) | Excluded responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking |

SMKDSTY (derived variable) SMK_01A, SMK_01B, SMK_202 and SMK_05D |

Questions are described in detail here22 |

1—“Daily smoker” 2—“Occasional smoker (former daily smoker)” 3—Occasional smoker (never a daily smoker or has smoked less than 100 cigarettes lifetime) 4—“Former daily smoker (non-smoker now)” 5—“Former occasional smoker (at least 1 whole cigarette, non-smoker now)” 6—“Never smoked (a whole cigarette)” |

1—1, 2, 3, 4 2—5, 6 (*1) |

99—“At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)” |

| Alcohol consumption |

ALCDTTM (derived variable) ALC_1 ALC_2 |

Questions are described in detail here22 |

1—“Regular drinker” 2—“Occasional drinker” 3—“Did not drink in the last 12 months” |

1—1, 2 2—3 (*1) |

9—“At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)” |

| Fruit and vegetable consumption | FVCDTOT | Questions are described in detail here22 |

0 = Minimum 120 = Maximum |

1—less than the median FVCDTOT of all respondents 2—greater or equal to the median FVCDTOT of all respondents (*1) |

999.99—“At least one required question was not answered (don't know, refusal, not stated)” |

| Self-perceived mental health and life stress | GEN_02B | “In general, would you say your mental health is: |

1—…excellent?” 2—…very?” 3—good?” 4—…fair?” 5—…poor?” |

1—1, 2, 3 2—4, 5 (*1) |

N/A |

| GEN_07 | “Thinking about the amount of stress in your life, would you say that most days are: |

1—…not at all stressful? 2—…not very stressful? 3—…a bit stressful? 4—…quite a bit stressful? 5—…extremely stressful?” |

1—1, 2, 3 2—4, 5 (*1) |

N/A | |

| Total household income |

INCGHH INCDHH INC_5A INC_5B INC_5C |

Questions are described in detail here22 |

1—“No income or less than 20,000” 2—“$20,000 to $39,999” 3—“$40,000 to $59,999” 4—“$60,000 to $79,999” 5—“$80,000 or more” |

1—1 2—2, 3, 4, 5 (*1) |

9—“Required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)” |

| Educational level |

EDUDH04 EDUDR04 EDU_1, EDU_2, EDU_3 and EDU_4 |

Questions are described in detail here22 |

1—“Less than secondary school graduation” 2—“Secondary school graduation, no post-secondary education” 3—“Some post-secondary education” 4—“Post-secondary degree/diploma” |

1—1, 2 2—3, 4 (*1) |

9—“At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)” |

CCHS Canadian Community Health Survey.

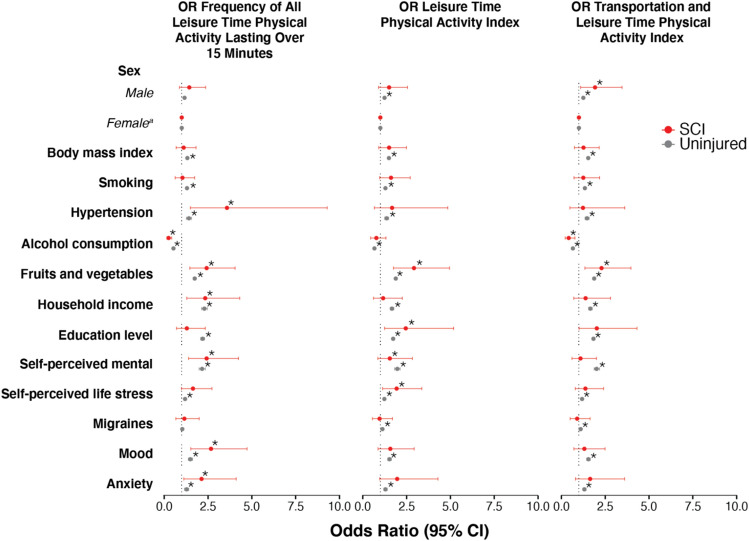

The interaction between physical activity with lifestyle and socioeconomic factors in people with and without SCI

In people with SCI, there was no association between physical activity level and sex, body mass index, migraines, or smoking. This is in contrast to people without SCI where male sex, lower body mass index, not smoking, and absence of migraines were associated with increased physical activity levels (Fig. 1). In both those with and without SCI, there was an association between increased physical activity levels and not being diagnosed with hypertension, eating more fruits and vegetables, greater household income, greater education levels, better mental health, lower stress levels, reduced likelihood of mood disorders, and reduced anxiety (Fig. 1). For details on lifestyle and socioeconomic factors, see Tables 4 and 5.

Figure 1.

Lifestyle and socioeconomic factors. Odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals for the association between physical activity levels and lifestyle and socioeconomic variables. ORs derived from logistic regression models. SCI spinal cord injury, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio.

Discussion

On a population-scale, physical activity levels are reduced in people with SCI compared to uninjured individuals. This result persisted after adjustment for age, sex, BMI, as well as numerous lifestyle and socio-economic factors. Lower-income, education, and fruit and vegetable consumption and increased alcohol use were associated with reduced physical activity in the SCI population. As such, specific socio-economic groups within the SCI population may benefit most from physical activity promotion activities.

Physical activity levels are reduced in those with SCI

Reduced physical activity in people with SCI is likely the result of numerous physical factors, including loss of skeletal muscle control, reduced skeletal muscle mass, reduced cardiovascular reserve, as well as environmental and social barriers23,24. Moreover, other psychological and behavioural barriers to engagement in physical activity include a lack of knowledge, community support, beliefs in ability, coping, conflicting goals for rehabilitation and limited access to disability-related experts and accessible rehabilitation infrastructures25–27. Reduced physical activity plausibly contributes to widespread cardiometabolic disorders after SCI, increased cardiovascular disease and diabetes risk, and a range of physical, emotional, and mental health issues that affect people with SCI1,3,28–30. As such, it is essential that targeted physical activity interventions for individuals with SCI integrate physical, psychological and behavioural based approaches to support effective uptake of interventional strategies and ensure the mitigation of these risk factors. Furthermore, strategies to increase physical activity may be more successful if they are integrated into adapted activities and/or those that directly align with an individual's goals (i.e., gardening, walking a dog, cycling, resistance training, yoga etc.)31.

Previous research has shown that approximately half of people with SCI report no leisure-time physical activity. However, it is not clear if this proportion differs from non-SCI populations, who also report very high rates of physical inactivity8,9. Another study compared physical activity levels in 40 people with SCI to age-matched uninjured controls, showing that individuals with SCI have reduced durations of dynamic activity one year after discharge from rehabilitation32. Our data provide additional support for these findings on a population-scale with control individuals.

There is a unique profile of lifestyle factors associated with physical activity levels within the SCI population. Within the SCI population there is no association between male sex, reduced body mass index, less likelihood of migraines, and not smoking with physical activity levels. This may be due to a variety of factors that are outside the scope of this study to quantitatively evaluate. Some of these may include the interaction between gender and self-efficacy before and after SCI33–35, as well as the interaction between body mass index and severity of disability after SCI36.

In the present data, greater physical activity was associated with an improved lifestyle. Greater physical activity levels in people with SCI were also associated with a reduced likelihood of being diagnosed with hypertension, anxiety and mood disorders, better mental health, and lower self-reported stress (Fig. 1). Greater household income and education, as well as lower alcohol consumption and eating more fruits and vegetables, were also factors associated with increased physical activity levels. Lower education and household income in the general population have also been associated with low physical activity levels37. It is reasonable to expect that these factors, in combination with the consequences of SCI, may be further exaggerated in the SCI population. These specific demographic groups within the SCI population (those with lower education and household incomes), should therefore be precision-targeted to understand exercise barriers, potential education programs needed and ultimately establish effective interventional strategies that promote physical activity. For example, previous public health interventions have promoted active transportation involving human energy to mobilize and travel. These programs have demonstrated success as they have been established by creating safe environments (e.g., improving community landscape, adding more sidewalks, longer pedestrian crossing times on signal lights) for the general population including pedestrians, bikers, as well as wheelchair users38,39. Interventional programs such as these provide equal opportunities for individuals with varying socioeconomic backgrounds to access transportation options and provide an example of an effective strategy that integrated the physical, behavioural, and social needs of multiple demographics to encourage uptake of a desired outcome for a broad population.

Limitations

A primary strength of this study was the use of the CCHS databases, as the sample selected is designed to be representative of the Canadian population (~ 34 million adults), and therefore the data is considered highly generalizable40. Furthermore, the ~ 330 respondents with SCI represent ~ 0.4% of the population of Canadians living with SCI41. It is also unlikely that our results suffered from response bias as is expected in a single topic survey when respondents would potentially aim to answer questions in the style that the interviewers prefer. Although self-reported physical activity levels in people with SCI are subjective, they do relate to objective physical activity measures42. However, the specific questions asked in the CCHS have not been assessed in comparison to objective measures. The CCHS data are derived from a cross-sectional study design and it is therefore not possible to determine the causality between variables. It is possible that misclassification occurred in terms of level and severity of injury. This would be most likely for individuals with less severe SCI, who would be expected to participate in physical activity more frequently than those with higher more complete SCI43. Therefore, including individuals with lower severity scores may result in an underestimation of the reported effect size.

Conclusions

On a population-level, physical activity levels in people with SCI are reduced, even after controlling for lifestyle and socioeconomic factors. Specific socio-economic groups within the SCI population, such as those in lower socioeconomic demographics, may benefit most from physical activity promotion activities.

Methods

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

All research was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines/regulations. The Tri-Council Policy Statement on Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2) states that use of publicly available, de-identified information, such as Statistics Canada data (i.e., the Canadian Community Health Survey), is exempt from review by institutional research ethics boards. This policy was confirmed by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board.

Data source

To evaluate physical activity in individuals with SCI compared to individuals without SCI, the data were accessed through the 2010 component of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). The CCHS is a comprehensive national survey conducted by Statistics Canada. The survey is voluntary and conducted on individuals aged 12 years and older, who reside in households across all Canadian provinces and territories44. Individuals living on reserves or Crown lands, full-time members of the Canadian armed forces, and those living in institutions (i.e., prisons, hospitals, universities) are excluded from the survey.

Exposure and outcome definitions

SCI status

SCI status was obtained with the question: “Do you have a neurological condition caused by a spinal cord injury?” During the survey, individuals were given the following reminder: “Remember, we’re interested in conditions diagnosed by a health professional.” Only those with valid responses for the primary explanatory variable and outcome variables were included in the analysis. Non-respondents (those in the categories of “don’t know,” “refusal,” and “not stated”) were excluded. The questions are described in detail here22,45.

Frequency of all leisure time physical activity lasting over 15 min

To capture “leisure time activity frequency”, we used the PACDFR variable from the CCHS. This variable classifies respondents as having “regular practice of leisure time activities”, “occasional practice of leisure time activities” and “infrequent practice of leisure time activities” lasting over 15 min based on the monthly frequency of physical activity reported for a three-month period. The questions are described in detail here22,45. Responses for PACDFR were binarized (Table 6).

Table 6.

Measures of physical activity levels.

| Variable name | CCHS code | Question | Response values | Combined response values (*reference category) | Excluded responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical activity levels | |||||

| Frequency of all leisure time physical activity lasting over 15 min | PACDFR | Questions are described in detail here22 |

1 = “Regular practice of leisure time activities” 2 = “Occasional practice of leisure time activities” 3 = “Infrequent practice of leisure time activities” |

1—1, 2 2—3 (*2) |

9 = Required question was not answered (don’t know, NS refusal, not stated) |

| Leisure time physical activity index | PACDPAI | Questions are described in detail here22 |

1 = “Active” 2 = “Moderately active” 3 = “Inactive” |

1—1, 2 2—3 (*2) |

9 = At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated) |

| Transportation and leisure time physical activity index | PACDLTI | Questions are described in detail here4 |

1 = “Active” 2 = “Moderately active” 3 = “Inactive” |

1—1, 2 2—3 (*2) |

9 = At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated) |

CCHS Canadian Community Health Survey.

Leisure time physical activity index

To capture “leisure time activity intensity”, we used the PACDPAI variable from the CCHS.

This variable categorizes respondents as being "active", "moderately active", or "inactive" in their leisure time based on the reported total daily Energy Expenditure values (kcal/kg/day) during the past three months. The questions are described in detail here22,45. Responses for PACDPAI were binarized (Table 6).

Transportation and leisure time physical activity index

To capture “transportation time activity intensity”, we used the PACDLTI variable from the CCHS. This variable categorizes respondents as being "active", "moderately active", or "inactive" in their transportation and leisure time based on the average daily energy expended (kcal/kg/day) during transportation and leisure-time physical activities by the respondent in the past three months. The questions are described in detail here22,45. Responses for PACDLTI were binarized (Table 6).

For details on physical activity level variables, see Table 6.

Comorbidities

Previous diagnosis of hypertension (CCC_072) was obtained with the following question: “Have you ever been diagnosed with high blood pressure?” Migraine status (CCC_081) was obtained with the following question: “Do you have migraine headaches?” Previous diagnosis of mood disorders (CCC_280) was obtained with the following question: “Do you have a mood disorder such as depression, bipolar disorder, mania or dysthymia?” Previous diagnosis of anxiety disorders (CCC_290) was obtained with the following question: “Do you have an anxiety disorder such as phobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder or a panic disorder?” An individual could provide a “Yes” or “No” answer to the aforementioned questions. The questions are described in detail here22,45.

Lifestyle and socioeconomic factors

Smoking status (SMKDSTY) indicates the type of smoker the respondent is. The questions are described in detail here22,45. The possible answers for SMKDSTY are “Daily smoker”, “Occasional smoker (former daily smoker)”, “Occasional smoker (never a daily smoker or has smoked less than 100 cigarettes lifetime)”, “Former daily smoker (non-smoker now)”, “Former occasional smoker (at least 1 whole cigarette, non-smoker now)”, “Never smoked (a whole cigarette)”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for SMKDSTY were binarized (Table 5).

Alcohol consumption status (ALCDTTM) indicates the type of drinker the respondent is for the past 12 months. The questions are described in detail here22,45. The possible answers for ALCDTTM are “Regular drinker”, “Occasional drinker”, “Did not drink in the last 12 months”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for ALCDTTM were binarized (Table 5).

Fruit and vegetable consumption (FVCGTOT) was obtained based on the derived variable FVCDTOT (indicates the total number of times per day the respondent consumes fruits and vegetables [i.e., fruit juice, fruits, green salad, potatoes, and carrots]). The questions are described in detail here22,45. The possible answers for FVCGTOT are “Eats fruits and vegetables less than 5 times per day”, “Eats fruits and vegetables between 5 and 10 times per day”, Eats fruits and vegetables more than 10 times per day”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don't know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for FVCGTOT were binarized (Table 5).

Self-perceived mental health (GEN_02B) was obtained with the question: “In general, would you say your mental health is: …excellent?, …very good?, …good?, …fair?, …poor? ”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don't know, refusal, not stated)”. Self-perceived life stress (GEN_07) was obtained with the question: “Thinking about the amount of stress in your life, would you say that most days are: …not at all stressful?, …not very stressful?, …a bit stressful?, …quite a bit stressful?, or …extremely stressful?”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don't know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for GEN_02B and GEN_07 were binarized (Table 5).

Total household income (INCGHH) is based on INCDHH (INC_5A, INC_5B and INC_5C). The questions are described in detail here22,45. The possible answers for INCDHH are “No income or less than 20,000”, “$20,000 to $39,999”, “$40,000 to $59,999”, “$60,000 to $79,999”, “$80,000 or more”, or “Required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for INCGHH were binarized (Table 5).

The highest level of education attained within the household (EDUDH04) is based on the highest level of education for each member of the household (EDUDR04). The questions are described in detail here22,45. The possible answers are “Less than secondary school graduation”, “Secondary school graduation, no post-secondary education”, “Some post-secondary education”, “Post-secondary degree/diploma”, or “At least one required question was not answered (don’t know, refusal, not stated)”. Responses for EDUDH04 were binarized (Table 5).

Statistical analysis

Logistic regression models were obtained separately for the binary outcome physical activity levels with SCI as the main explanatory variable, and with lifestyle and socio-economic factors as the main explanatory variable. Models were probability weighted to account for the clustering and stratification sampling design used by the CCHS (as previously reported)2,46. Separate logistic regression models were generated for the physical activity outcomes using the ‘glm’ (generalized linear model) function with the family argument set to ‘binomial()’ from the R Statistical Software package ‘stats’. R (R Core Team, 2017) was used for all statistical analyses. Using the logistic models, unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals are presented. Goodness of fit for the full model was assessed using a receiver-operating curve (ROC). The ORs were then adjusted for potential confounders using multivariable logistic regression. In the multivariable model, age, sex, and body mass index were input as additional explanatory variables to calculate the adjusted model (AOR). The sensitivity analysis included the lifestyle and socioeconomic variables described above. A fully adjusted model (AOR2) including all these potential explanatory variables is then presented. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value ≤ 0.05. Data are presented in accordance with the STROBE guidelines of reporting47.

Author contributions

J.E.S., J.W.S., and A.A.P. analyzed the data. J.E.S. and A.A.P. wrote the first draft of the paper. A.A.P. designed, conceptualized, and supervised the study. All authors interpreted the data, revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final version.

Funding

The Phillips Lab is supported by the Wings for Life Foundation (Project Grant), Compute Canada (Resources for Research Groups), Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada; Discovery Grant), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (Project Grant), Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, Campus Alberta Neuroscience, the Libin Cardiovascular Institute of Alberta, the Hotchkiss Brain Institute, and PRAXIS.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from Statistics Canada.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aaron A. Phillips, Email: aaron.phillips@ucalgary.ca

Zeljko Dujic, Email: zeljko.dujic@mefst.hr.

References

- 1.Warburton DER, Nicol CW, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: The evidence. CMAJ. 2006;174:801–809. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Krassioukov A, Borisoff J. Cardiovascular disease and spinal cord injury: Results from a national population health survey. Neurology. 2013;81:723–728. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a1aa68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cragg JJ, Noonan VK, Dvorak M, Krassioukov A, Mancini GBJ, Borisoff JF. Spinal cord injury and type 2 diabetes: results from a population health survey. Neurology. 2013;81:1864–1868. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000436074.98534.6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips AA, Krassioukov AV. Contemporary cardiovascular concerns after spinal cord injury: Mechanisms, maladaptations, and management. J. Neurotrauma. 2015;32:1927–1942. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Middendorp JJ, Allison H, Cowan K, Spinal Cord Injury Priority Setting Partnership Top ten research priorities for spinal cord injury. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:1167. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mickens MN, Perrin P, Goldsmith JA, Khalil RE, Carter WE, III, Gorgey AS. Leisure-time physical activity, anthropometrics, and body composition as predictors of quality of life domains after spinal cord injury: An exploratory cross-sectional study. Neural Regen. Res. 2022;17:1369–1375. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.327356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Filipcic T, Sember V, Pajek M, Jerman J. Quality of life and physical activity of persons with spinal cord injury. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginis KAM, Latimer AE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, Buchholz AC, Bray SR, Craven BC, Hayes KC, Hicks AL, McColl MA, Potter PJ, Smith K, Wolfe DL. Leisure time physical activity in a population-based sample of people with spinal cord injury part I: Demographic and injury-related correlates. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2010;91:722–728. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colley RC, Garriguet D, Janssen I, Craig CL, Clarke J, Tremblay MS. Physical activity of Canadian adults: Accelerometer results from the 2007 to 2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Rep. 2011;22:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kari JT, Pehkonen J, Hirvensalo M, Yang X, Hutri-Kähönen N, Raitakari OT, Tammelin TH. Income and physical activity among adults: Evidence from self-reported and pedometer-based physical activity measurements. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford ES, Merritt RK, Heath GW, Powell KE, Washburn RA, Kriska A, Haile G. Physical activity behaviors in lower and higher socioeconomic status populations. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1991;133:1246–1256. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim K, Taylor L. Factors associated with physical activity among older people—A population-based study. Prev. Med. 2005;40:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milicic S, Piérard E, DeCicca P, Leatherdale ST. Examining the association between physical activity, sedentary behavior and sport participation with E-cigarette use and smoking status in a large sample of canadian youth. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019;21:285–292. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw BA, Spokane LS. Examining the association between education level and physical activity changes during early old age. J. Aging Health. 2008;20:767–787. doi: 10.1177/0898264308321081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piazza-Gardner AK, Barry AE. Examining physical activity levels and alcohol consumption: are people who drink more active? Am. J. Health Promot. 2012;26:e95–104. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.100929-LIT-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krause JS, Saunders LL, DeVivo MJ. Income and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011;92:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zürcher C, Tough H, Fekete C, SwiSCI Study Group Mental health in individuals with spinal cord injury: The role of socioeconomic conditions and social relationships. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0206069. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan W-M, Mohammed Y, Lee I, Pearse DD. Effect of gender on recovery after spinal cord injury. Transl. Stroke Res. 2013;4:447–461. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walters JL, Buchholz AC, Martin Ginis KA, SHAPE-SCI Research Group Evidence of dietary inadequacy in adults with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:318–322. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garshick E, Kelley A, Cohen SA, Garrison A, Tun CG, Gagnon D, Brown R. A prospective assessment of mortality in chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2005;43:408–416. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tate DG, Forchheimer MB, Krause JS, Meade MA, Bombardier CH. Patterns of alcohol and substance use and abuse in persons with spinal cord injury: Risk factors and correlates. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;85:1837–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canada OS. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS): Annual Component—2010 Questionnaire [Internet]. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/pub/instrument/3226_Q1_V7-eng.pdf. (Accessed 1 December 2019).

- 23.Gorgey AS. Exercise awareness and barriers after spinal cord injury. World J. Orthop. 2014;5:158–162. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scelza WM, Kalpakjian CZ, Zemper ED, Tate DG. Perceived barriers to exercise in people with spinal cord injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2005;84:576–583. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000171172.96290.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kehn M, Kroll T. Staying physically active after spinal cord injury: A qualitative exploration of barriers and facilitators to exercise participation. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroll T, Jones GC, Kehn M, Neri MT. Barriers and strategies affecting the utilisation of primary preventive services for people with physical disabilities: A qualitative inquiry. Health Soc. Care Community. 2006;14:284–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawrason, S. V. C., Martin Ginis, K. A. Factors associated with leisure-time physical activity participation among individuals with spinal cord injury who ambulate. Disabil. Rehabil. 1–8 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Gill M. Psychosocial implications of spinal cord injury. Crit. Care Nurs. Q. 1999;22:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00002727-199908000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Post MWM, van Leeuwen CMC. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: A review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:382–389. doi: 10.1038/sc.2011.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DeVivo MJ, Black KJ, Richards JS, Stover SL. Suicide following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1991;29:620–627. doi: 10.1038/sc.1991.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrier M-J, Stork MJ, Martin Ginis KA, SHAPE-SCI Research Group Type, intensity and duration of daily physical activities performed by adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:64–70. doi: 10.1038/sc.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van den Berg-Emons RJ, Bussmann JB, Haisma JA, Sluis TA, van der Woude LH, Bergen MP, Stam HJ. A prospective study on physical activity levels after spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and the year after discharge. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2008;89:2094–2101. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geyh S, Nick E, Stirnimann D, Ehrat S, Michel F, Peter C, Lude P. Self-efficacy and self-esteem as predictors of participation in spinal cord injury—An ICF-based study. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:699–706. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fitzpatrick DA, Watkinson EJ. The lived experience of physical awkwardness: Adults’ retrospective views. Adapt. Phys. Activ. Q. 2003;20:279–297. doi: 10.1123/apaq.20.3.279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gater DR., Jr Obesity after spinal cord injury. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am. 2007;18(333–51):vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta N, White KT, Sandford PR. Body mass index in spinal cord injury—A retrospective study. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:92–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spinney J, Millward H. Time and money: A new look at poverty and the barriers to physical activity in Canada. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010;99:341–356. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9585-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young DR, Cradock AL, Eyler AA, Fenton M, Pedroso M, Sallis JF, Whitsel LP, American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee Creating built environments that expand active transportation and active living across the United States: A policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142:e167–e183. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Government of Canada. Canada’s National Active Transportation Strategy 2021–2026. https://www.infrastructure.gc.ca/alt-format/pdf/nats-snta/nats-strat-snta-en.pdf. (Accessed 5 July 2020).

- 40.Cassidy T, Fortin A, Kaczmer S, Shumaker JTL, Szeto J, Madill SJ. Relationship between back pain and urinary incontinence in the Canadian population. Phys. Ther. 2017;97:449–454. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Noonan VK, Fingas M, Farry A, Baxter D, Singh A, Fehlings MG, Dvorak MF. Incidence and prevalence of spinal cord injury in Canada: A national perspective. Neuroepidemiology. 2012;38:219–226. doi: 10.1159/000336014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ginis KAM, Latimer AE, Hicks AL, Craven BC. Development and evaluation of an activity measure for people with spinal cord injury. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2005;37:1099–1111. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000170127.54394.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nooijen CFJ, Act-Active Research Group. Post MWM, Spooren AL, Valent LJ, Broeksteeg R, Sluis TA, Stam HJ, van den Berg-Emons RJG. Exercise self-efficacy and the relation with physical behavior and physical capacity in wheelchair-dependent persons with subacute spinal cord injury. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 2015 doi: 10.1186/s12984-015-0099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Béland Y. Canadian community health survey—methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Statistics: Ottawa C. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS): Annual Component—2009–2010 Common Content Derived Variable (DV) Specifications. https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/pub/document/3226_D71_T9_V1-eng.pdf. (Accessed 2 December 2019).

- 46.Squair JW, Dhaliwal R, Cragg JJ, Charbonneau R, Grant C, Phillips AA. National survey of bladder and gastrointestinal dysfunction in people with spinal cord injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2019 doi: 10.1089/neu.2018.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are publicly available from Statistics Canada.