Summary

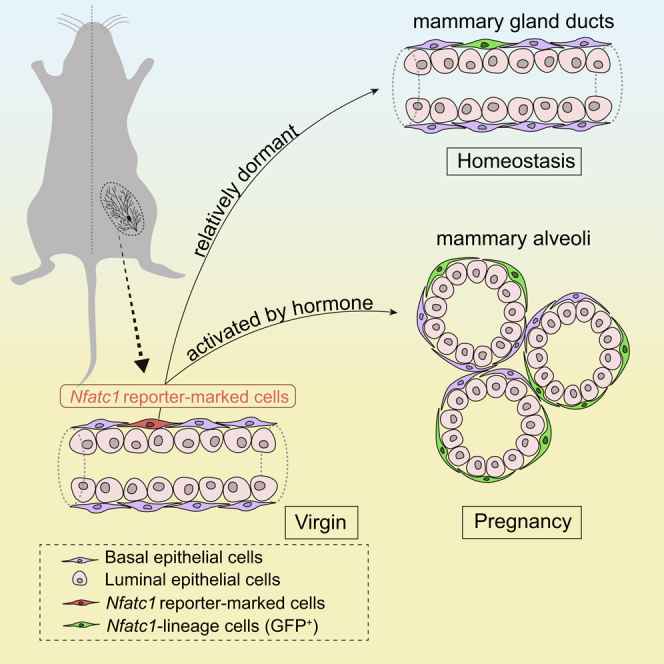

The Mammary gland undergoes complicated epithelial remodeling to form lobuloalveoli during pregnancy, in which basal epithelial cells remarkably increase to form a basket-like architecture. However, it remains largely unknown how dormant mammary basal stem/progenitor cells involve in lobuloalveolar development. Here, we show that Nfatc1 expression marks a rare population of mammary epithelial cells with the majority being basal epithelial cells. Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are relatively dormant mammary stem/progenitor cells. Although Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells have limited contribution to the homeostasis of mammary epithelium, they divide rapidly during pregnancy and contribute to lobuloalveolar development. Furthermore, Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are preferentially used for multiple pregnancies. Using single-cell RNA-seq analysis, we identify multiple functionally distinct clusters within the Nfatc1 reporter-marked cell-derived progeny cells during pregnancy. Taken together, our findings underscore Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells as dormant stem/progenitor cells that contribute to mammary lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy.

Subject areas: Biological sciences, Molecular physiology, Stem cells research, Omics

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Nfatc1 marked a subpopulation of basal dormant stem/progenitor cells

-

•

Nfatc1-marked cells have limited contribution to the homeostasis of mammary gland

-

•

Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells divide rapidly during pregnancy

-

•

Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells are preferentially used for multiple pregnancies

Biological sciences; Molecular physiology; Stem cells research; Omics

Introduction

The mammary gland is unique in that the majority of its epithelial morphogenesis occurs postnatally (Richert et al., 2000). It undergoes complicated epithelial remodeling at multiple distinctive stages from embryonic and pubertal development to reproductive life (Macias and Hinck, 2012). After birth, the gland just rests with a rudimentary structure until puberty; with the onset of puberty, the increase of estrogen and growth hormone levels promote the rapid proliferation of mammary epithelial cells leading to the formation of a mammary ductal tree that fills the fat pad (Inman et al., 2015; Macias and Hinck, 2012). During pregnancy, massive tissue changes occur within the mammary gland in response to progesterone and prolactin, resulting in the formation of milk-secreting lobuloalveoli in preparation for lactation. In this process, both basal and luminal epithelial cells divide rapidly and globally within the ductal branches and developing alveoli, and the luminal alveolar cells form a sphere-like single-layer structure surrounded by a basket-like architecture of basal contractile myoepithelial cells (Hens and Wysolmerski, 2005). However, although it has been known that the numbers of basal myoepithelial cells increase 11-fold in the basal compartment during pregnancy (Asselin-Labat et al., 2010), the cellular mechanism underlying basal mammary stem/progenitor cells' role in driving contractile basket-like architecture remains to be fully understood.

Increasing evidence indicates that mammary stem cells (MaSCs) are diverse (Fu et al., 2020). MaSCs have been shown to reside in the basal layer and can reconstitute the entire mammary gland when transplanted into a cleared fat pad (Shackleton et al., 2006; Stingl et al., 2006). Subsequently, lineage tracing assays with K5, Lgr5, and Axin2 promoter drivers have demonstrated the existence of long-lived basal-restricted unipotent progenitor cells that drive postnatal morphogenesis and replenishment of the basal layer during homeostasis in the adult stage (van Amerongen et al., 2012; Van Keymeulen et al., 2011; Wuidart et al., 2016). Bipotent basal cells have also been identified in the adult mammary gland in lineage tracing assays using the same or more restricted gene promoter drivers (K5, Lgr5, Procr, and Dll1) (Chakrabarti et al., 2018; Rios et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). In addition, Lgr5+Tspan8high cells and Bcl11bhigh cells have been identified as quiescent MaSCs in the basal compartment, with Lgr5+Tspan8high cells residing predominantly in the proximal region (Chakrabarti et al., 2018) and Bcl11bhigh cells localizing throughout the mammary gland (Cai et al., 2017). It has been implicated that a striking expansion of basal epithelial cells during pregnancy is fueled by distinct MaSC subsets (Chakrabarti et al., 2018; Rios et al., 2014; Van Keymeulen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015). However, our understanding of the contribution of mammary stem/progenitor cells to lobuloalveolar development remains limited.

Nfatc1 is a transcription factor the expression of which labels the quiescent bulge stem cells of the hair follicle, and it maintains the stem cells in a quiescent state as a downstream factor of BMP signaling (Horsley et al., 2008; Keyes et al., 2013). Interestingly, Nfatc1 regulates prolactin receptor, Prlr, in hair follicles during pregnancy (Goldstein et al., 2014). As prolactin/Prlr signaling is a key driver of mammary lobuloalveolar development and milk protein production (Sternlicht, 2006), we entertained the possibility that Nfatc1 may also mark mammary epithelial cell subsets that are important for lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy. In this study, we demonstrated that Nfatc1 marked a rare population of mammary epithelial cells as dormant long-lived stem/progenitor cells. Nfatc1 reporter-marked stem/progenitor cells show limited contribution to the homeostasis of mammary epithelial cells, whereas they contribute to mammary lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy and are preferentially used for multiple pregnancies.

Results

Nfatc1 expression labels a small population of mammary stem/progenitor cells

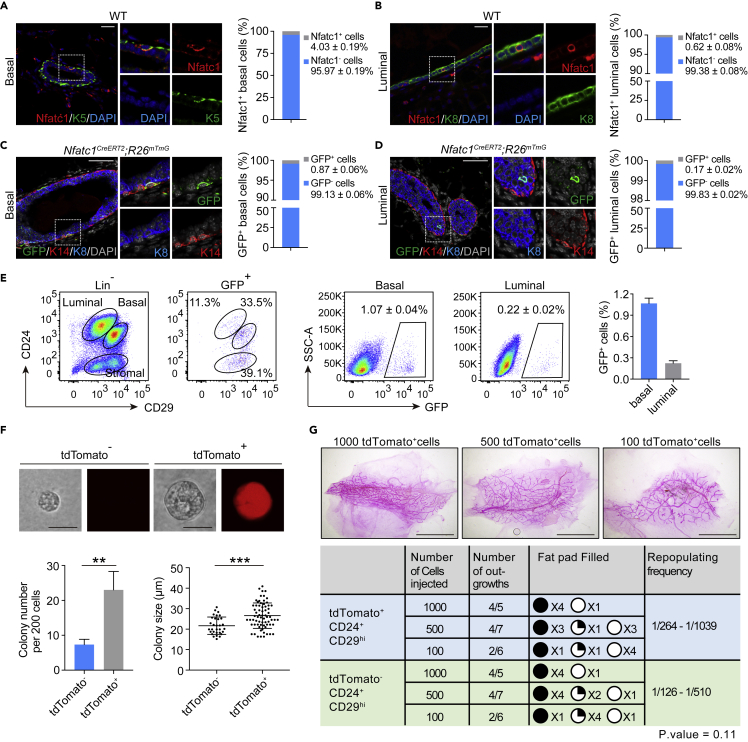

To identify and characterize Nfatc1+ epithelial cells in the mammary gland, we first performed immunofluorescence assay to detect the Nfatc1 expression pattern in the mammary gland. We found that a small population of Nfatc1+ epithelial cells was sporadically distributed in both basal and luminal layers of mammary epithelium (Figures 1A and 1B). Quantification analysis showed that 4.03 ± 0.19% of the basal cells were Nfatc1+ (Figure 1A), and 0.62 ± 0.08% of the luminal cells were Nfatc1+ (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Nfatc1 expression labels a small population of mammary stem/progenitor cells (see also Figure S1)

(A and B) Co-immunofluorescence assay for Nfatc1 and K5 (A) or Nfatc1 and K8 (B) in eight-week-old WT mammary glands. n = 3 mice. Scale bar, 25 μm. High-magnification images are shown on the right. The percentages of Nfatc1+ basal cells among total basal cells (A) and Nfatc1+ luminal cells among total luminal cells (B) were quantified. A total of 1,952 basal cells and 8,335 luminal cells from three mice were counted

(C and D) Co-immunofluorescence assay for GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in mammary glands from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at the age of eight weeks. GFP+ cells were present in the basal (C) and luminal (D) layers. n = 3 mice. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis shows the percentages of GFP+ basal cells among total basal cells (C) and GFP+ luminal cells among total luminal cells (D). A total of 1,614 basal cells and 5,314 luminal cells from three mice were quantified

(E) Flow cytometry assay of GFP+ cells from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at the age of eight weeks. The mice were administered TAM three times, and the samples were collected 48 h after the last induction. Quantification analysis showing the percentages of GFP+ basal cells among total basal cells and GFP+ luminal cells among total luminal cells. Another analysis approach is also shown. Total GFP+ cells were applied to CD24 and CD29 gates, showing the distribution of GFP+ cells in the basal and luminal layers. n = 3 mice

(F) Colony formation efficiency and colony size in the Matrigel culture. For tdTomato+ and tdTomato− basal cells, a total of 69 and 31 clones were analyzed from three independent experiments. Scale bar, 25 μm

(G) Transplantation of tdTomato+ and tdTomato− basal epithelial cells by limiting dilution. Data are pooled from two independent experiments. Scale bar, 5 mm. The repopulation frequency was calculated using the method in http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/. Data represent the mean value ±SD ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001

In order to further characterize Nfatc1+ mammary epithelial cells, we generated a tamoxifen-inducible Cre (CreERT2) knock-in allele targeted immediately downstream of the eighth exon of the endogenous Nfatc1 locus (Figure S1A), thereby targeting all isoforms. The targeted allele was validated by PCR (Figure S1B). After crossing, Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG or Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato reporter mice were obtained for labeling Nfatc1+ cells and their progenies (Figure S1C). To validate these Nfatc1 reporter mice, we administered one single pulse of tamoxifen (TAM) into Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice and analyzed the mice 48 h after TAM induction for hair follicle labeling. As expected, we found Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells in the bulge regions of the hair follicles at both telogen and anagen stages that also stained positive for Nfatc1 protein (Figure S1D), indicating the validity of the Nfatc1 reporter mice as a useful lineage tracing tool.

To detect the distribution of reporter-marked cells in the mammary gland, eight-week-old Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice were induced with three pulses of TAM, which enhances the labeling efficiency relative to one pulse of TAM, and the mice were analyzed 48 h after the last induction (Figure S1E). In agreement with Nfatc1 protein expression, Nfatc1 reporter labeled rare mammary epithelial cells in both the basal and luminal layers, with 0.87 ± 0.06% of basal cells and 0.17 ± 0.02% of luminal cells being GFP+ (Figures 1C and 1D). We also quantified the proportions of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal and luminal cells by flow cytometry, which revealed 1.07 ± 0.04% and 0.22 ± 0.02% GFP+ cells in basal and luminal cells, respectively (Figure 1E). These values are lower than those of Nfatc1+ cells assayed by immunofluorescence, which is most likely due to incomplete labeling efficiency. These results were further corroborated using the Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice (Figures S1F and S1G). Taken together, our findings show that Nfatc1 labels a rare population of mammary epithelial cells with the majority of them being in the basal compartment.

Next, we sought to examine whether Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells are mammary stem/progenitor cells. We sorted Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells (tdTomato+/CD24+/CD29hi) using Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice and cultured the cells in Matrigel. Nfatc1 reporter-marked (tdTomato+) basal epithelial cells gave rise to 3-fold more colonies than their tdTomato− (tdTomato−/CD24+/CD29hi) counterparts (Figure 1F), and the average size of the colonies derived from tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells was significantly larger than that from tdTomato− basal epithelial cells (Figure 1F). These data indicate that tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells possess higher colony-forming and proliferative ability than tdTomato− basal epithelial cells. Furthermore, We sorted Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells (tdTomato+/CD24+/CD29hi) and Nfatc1 reporter-negative basal epithelial cells (tdTomato−/CD24+/CD29hi) using Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice and transplanted them into cleared fat pads. We found that the tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells were able to reconstitute the whole mammary gland, although the repopulating frequency of tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells is generally identical to tdTomato− basal epithelial cells (Figure 1G). It suggests that tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells contain mammary stem cells with high colony-forming capacity and that their activation might be context-dependent.

Nfatc1 reporter-marked stem/progenitor cells are dormant and distinct from other known MaSCs

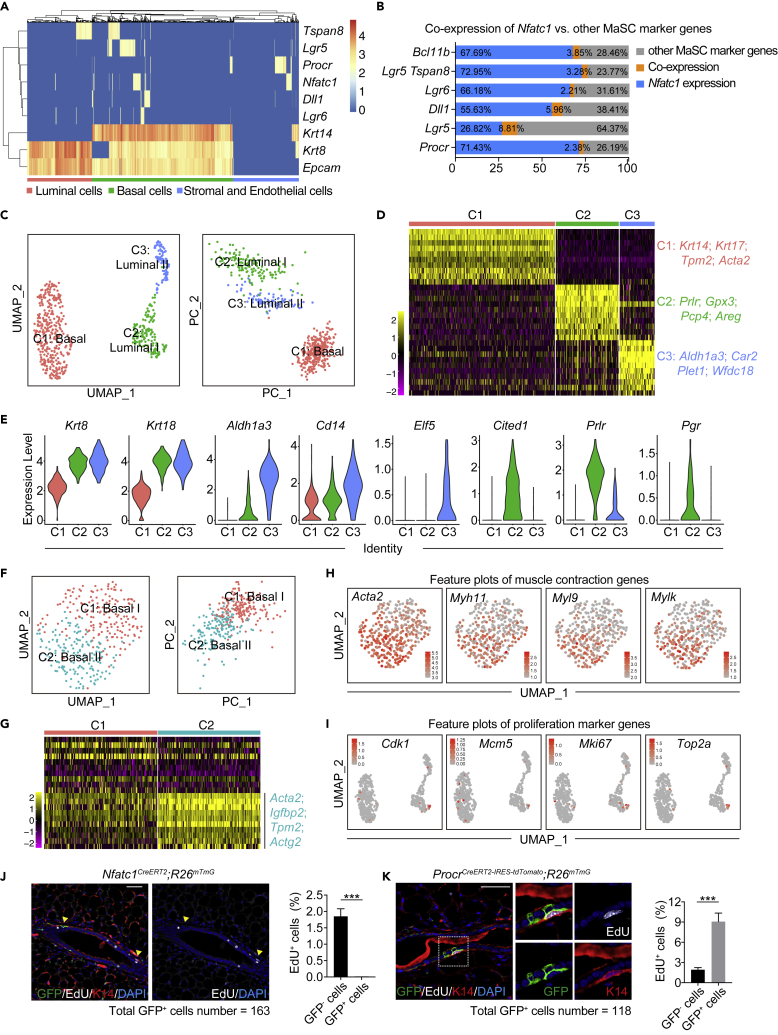

Next, we wanted to distinguish between tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells and other mammary stem/progenitor cells identified by known marker genes including Procr, Lgr5, Lgr6, and Dll1 (Blaas et al., 2016; Chakrabarti et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). We thus compared the Nfatc1 expression pattern to those known mammary stem/progenitor marker genes in mammary epithelial cells at a single-cell level. We analyzed an scRNA-seq database (https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org) for mammary epithelial cells from adult female mice, which is adapted from a previously published literature in Nature (Tabula Muris Consortium et al., 2018). With a cutoff of nUMI count >150, quantification of the cells positive for each marker gene showed that the proportions of Nfatc1+, Procr+, Lgr5+, Lgr6+ and Dll1+ basal epithelial cells out of total basal epithelial cells were 7.09%, 2.75%, 14.57%, 3.51% and 5.11%, respectively (Figure S2A). These values were generally consistent with the proportions for each marker gene (Procr+, 3%; Lgr5+, 11.4%; Lgr6+, 4.7%; Dll1+, 12%) that were analyzed by flow cytometry in previously published studies (Blaas et al., 2016; Chakrabarti et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2015). Thus, we utilized this cutoff to perform heatmap analysis, and found that Nfatc1+ basal epithelial cells rarely overlap with Lgr6+, Tspan8+, Procr+, and Dll1+ basal epithelial cells, and the overlap between Nfatc1+ and Lgr5+ basal epithelial cells is 8.81% out of Nfatc1+ and Lgr5+ cells (Figures 2A and 2B). The conclusion of low overlap was further supported by feature t-SNE assays (Figure S2B). Therefore, the Nfatc1 reporter-marked mammary stem/progenitor cells are generally distinct from other known mammary stem/progenitor cells.

Figure 2.

Nfatc1 repotrer-marked stem/progenitor cells are dormant and distinct from other known MaSCs (see also Figure S2)

(A) Heatmap analysis of the scRNA-seq database shows the expression patterns of Nfatc1 and other MaSC marker genes (Tspan8, Lgr5, Procr, Dll1, and Lgr6), as well as Krt14 (K14), Krt8 (K8), and Epcam. The scRNA-seq database for mammary epithelial cells was adapted from a previously published study in Nature and downloaded from https://tabula-muris.ds.czbiohub.org. A nUMI count >150 was used as a cutoff for low-expression cells

(B) Quantification for the percentages of basal cells expressing Nfatc1 or the MaSC marker genes Bcl11b, Tspan8/Lgr5, Lgr6, Dll1, Lgr5, and Procr in (A). Blue indicates Nfatc1+cells; grey indicates other MaSC marker genes; and orange indicates double-positive cells

(C) UMAP and PCA plots reveal cellular heterogeneity of 558 tdTomato+ mammary epithelial cells that were sorted from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice

(D) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes in each cluster for (C). Selected signature genes are shown on the right

(E) Violin plots show marker genes of common luminal cells (Krt8/K8 and Krt18/K18), milk lineage cells (Cd14, Aldh1a3, and Elf5), and ER+ lineage cells (Cited1, Prlr, and Pgr) for each cluster in (C)

(F) UMAP and PCA plots showing the reclustering results for 333 tdTomato+ basal cells. Luminal epithelial cells were removed

(G) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes in each cluster for (F). Selected signature genes are shown on the right

(H) Feature plots showing expression distribution of genes functioning in muscle contraction

(I) Feature plots showing expression distribution of genes functioning in cell proliferation in each cluster for (C)

(J and K) Co-immunofluorescence for GFP, EdU, and K14 in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice (J) and ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice (K) at 48 h post-TAM induction. Scale bar, 50 μm. The samples were collected 3 h after one dose of EdU injection. Quantification analysis shows the percentages of GFP+EdU+ cells versus GFP+ cells and GFP−EdU+ cells versus GFP− cells in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice (J) and ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice (K). For Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice, 163 GFP+ cells and 1766 GFP- cells were quantified, respectively. For ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice, 118 GFP+ cells and 1949 GFP- cells were quantified, respectively. n = 3 mice for each mouse model. Data represent the mean value ±SD ∗∗∗p < 0.001

To further characterize the identity of Nfatc1 reporter-marked epithelial cells, we performed unbiased single-cell transcriptomic analysis on tdTomato+ mammary epithelial cells that were isolated from eight-week-old female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice 48 h after three pulses of TAM induction (Figure S2C). After quality control, 2,952 cells were used for downstream analysis (Figure S2D). Unsupervised clustering identified seven distinct clusters (Figure S2E). Based on known gene signatures, cluster C4 was identified as basal epithelial cells, cluster C6 as luminal epithelial cells, clusters C1 and C3 as endothelial cells, cluster C2 as stromal cells, cluster C5 as muscle cells, and cluster C7 as immune cells (Figures S2E–S2G). After removing non-epithelial cells, tdTomato+ epithelial cells were regrouped into three distinct clusters (Figures 2C and 2D). Basal epithelial cells belonged to a single cluster (C1), whereas luminal epithelial cells were divided into two clusters, C2 and C3. Among them, the cells in C3 were identified as milk lineage cells, as they highly express marker genes of luminal progenitor cells, Aldh1a3, Cd14, and Elf5 (Bach et al., 2017; Pervolarakis et al., 2020; Shehata et al., 2012) (Figure 2E). The cells in C2 were identified as ER+ lineage cells, as they highly express differentiated cell marker genes, Prlr, Pgr, and Cited1 (Bach et al., 2017; Shehata et al., 2012) (Figure 2E). To better define the identity of tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells, we removed luminal epithelial cells and then performed unsupervised clustering on these cells. tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells can be further divided into two distinct subgroups based on the expression levels of genes functioning on muscle contraction (Figures 2F–2H). We also examined the proliferative status of tdTomato+ mammary epithelial cells. Cell cycle genes were barely expressed in tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells (Figure 2I), suggesting a dormant status. To confirm this idea, we performed an EdU incorporation assay using Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at 48 h post induction, then quantified EdU+GFP+ cells versus GFP+ cells and EdU+GFP− cells versus GFP− cells in mammary gland at the age of eight weeks. It showed that no Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells were found in S phase, whereas 1.85 ± 0.13% of Nfatc1 reporter-negative cells were in S phase (Figure 2J). In comparison, a parallel experiment showed that approximately 9.06 ± 0.73% of Procr reporter-marked cells were in the S phase at the same stage, whereas 1.93 ± 0.18% of Procr reporter-negative cells were in the S phase (Figure 2K). These data suggest that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are dormant relative to both Nfatc1 reporter-negative cells and Procr-reporter marked cells.

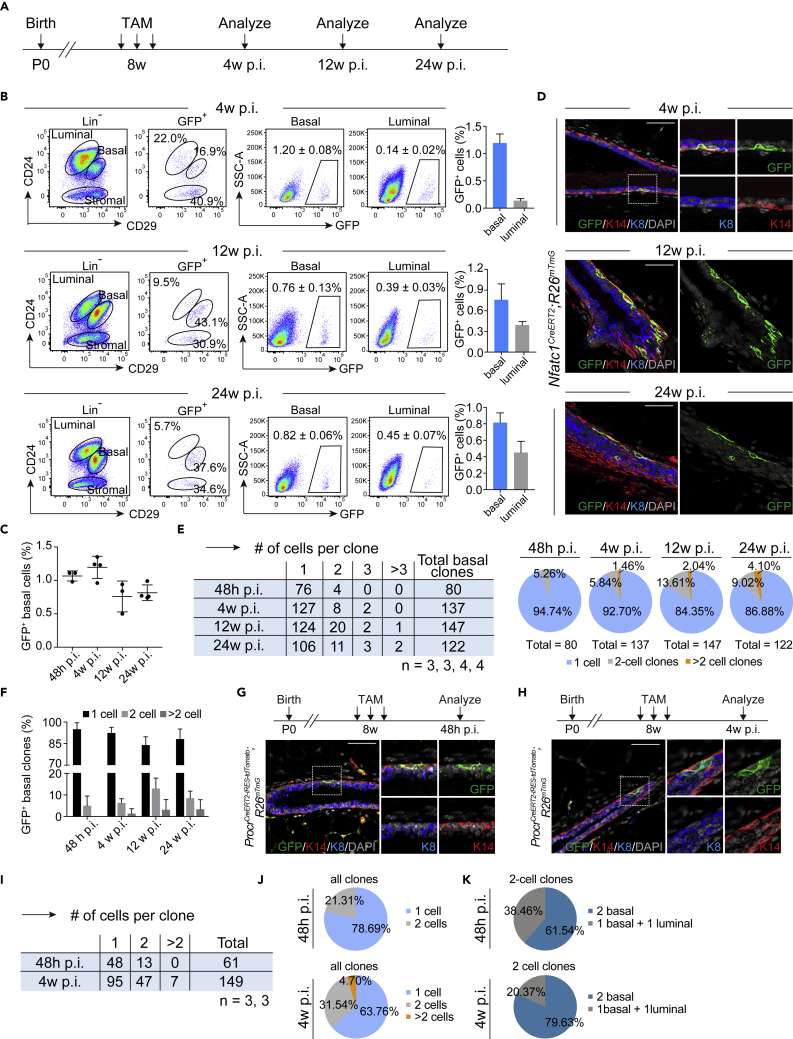

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells have restrictive contribution to mammary epithelium during homeostasis

To test the contribution of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells to the homeostasis of mammary epithelium in vivo, we performed lineage tracing assay using female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at successive timepoints. The mice were administered three doses of TAM at the age of 8 weeks and then were analyzed 4, 12, and 24 weeks after the last induction (Figure 3A). Using flow cytometry, the proportions of basal GFP+ cells 48 h, 4, 12 and 24 weeks after TAM induction were found to be 1.07 ± 0.04%, 1.20 ± 0.08%, 0.76 ± 0.13% and 0.82 ± 0.06%, respectively (Figures 1E and 3B). This result implies that basal GFP+ epithelial cells existed for a long time, whereas the proportion of GFP+ basal epithelial cells was not significantly altered with time after TAM induction (Figures 3B and 3C). Immunofluorescence assay further showed that GFP+ basal-only clones exist at distinct timepoints, whereas no GFP+ bilineage clones were observed (Figure 3D). Quantification of GFP+ clones showed that the proportions of two-cell basal clones 48 h, 4, 12, and 24 weeks after TAM induction were 5.26, 5.84, 13.61, and 9.02%, respectively, and those of multicell basal clones (≥3 cells) were 0, 1.46, 2.04, and 4.10%, respectively (Figures 3E and 3F). The data demonstrate that the proportions of two-cell and multicell basal clones increased with time. Taken together with findings above, these data suggest that Nfatc1-reporter marked basal epithelial cells, whereas relatively dormant, still contribute to the homeostasis of the mammary epithelium. In parallel experiments, we also administered the same TAM induction in ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice at the age of 8 weeks and analyzed them 48 h and 4 weeks after initial lineage labeling. We found that the proportions of two-cell clones were 21.31 and 31.54% 48 h and 4 weeks after initial lineage labeling and those of multicell clones were 0 and 4.7%, respectively (Figures 3G–3J). In comparison, 38.46 and 20.37% bilineage two-cell clones were detected in the mammary duct from ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice (Figure 3K). These findings show that, compared with Procr reporter-marked MaSCs, Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are unipotent and have limited contribution to the homeostasis of mammary epithelium.

Figure 3.

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells have restrictive contribution to mammary epithelium during homeostasis (see also Figures S3 and S4)

(A) Experimental strategy for successive lineage tracing experiments at different timepoints

(B) Flow cytometry for GFP+ epithelial cells from 8-week-old female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-TAM induction (p.i.). Another approach to analysis was also shown. Total GFP+ cells were applied to CD24 and CD29 gates, showing the distribution of GFP+ cells in the basal and luminal layers. Quantification analysis showing the percentages of GFP+ basal cells per total basal cells and GFP+ luminal cells per total luminal cells for each timepoint. n = 4, 3, and 4 mice at 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-induction, respectively

(C) Quantification analysis of the percentages of GFP+ basal cells per total basal cells in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice 48 h (n = 3), 4 weeks (n = 4), 12 weeks (n = 3), and 24 weeks (n = 4) after TAM induction

(D) Co-immunofluorescence assay for GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-TAM induction. Scale bar, 50 μm

(E and F) Quantification analysis shows the numbers (left panel of (E)) and the percentages (right panel of (E)) of single-cell, two-cell, and multicell basal clones in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at indicated timepoints (E). Another statistical result is also shown in panel (F). The total numbers of basal clones were 80, 137, and 147 and 122 at 48 h, 4, 12, and 24 weeks post-induction, respectively. n = 3, 3, 4, and 4, respectively

(G and H) Co-immunofluorescence assay for GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) from ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice 48 h (G) and 4 weeks (H) post-induction. Scale bar, 50 μm

(I–K) Quantification analysis shows the numbers (I) and the percentages of single-cell, two-cell, and multicell clones in ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato;R26mTmG mice at the indicated timepoints (J). The percentages of basal-only and bilineage two-cell clones was also quantified, shown on (K). n = 3 for each timepoint. A total of 61 and 149 clones were quantified at 48 h and 4 weeks post-induction, respectively. Data represent the mean value ±SD

Regarding the luminal layer, we found that the proportion of luminal GFP+ cells slightly decreased four weeks after initial lineage labeling, relative to 48 h after TAM induction, and then markedly increase 12 and 24 weeks after TAM induction (Figure S3A). Immunofluorescence assays revealed GFP+ multicell clones in mammary luminal epithelium at distinct timepoints (Figure S3B), and the proportions of two-cell and multicell clones increased with time (Figures S3C and S3D). These results support the idea that Nfatc1 reporter-marked luminal epithelial cells contain a fraction of luminal progenitor cells, which is consistent with the above scRNA-seq data.

Next, we examined the contribution of Nfatc1 reporter-marked epithelial cells to mammary gland development at the age of 4 weeks when it is puberty. At this stage, the mammary gland undergoes a period of expansive proliferation that is primarily regulated by estrogen and growth hormones (Macias and Hinck, 2012). Similar to the adult stage (eight-week old), GFP+ basal epithelial cells contributed to the turnover of mammary epithelium with low efficiency (Figures S4A–S4E). It further suggests a limited contribution to mammary homeostasis.

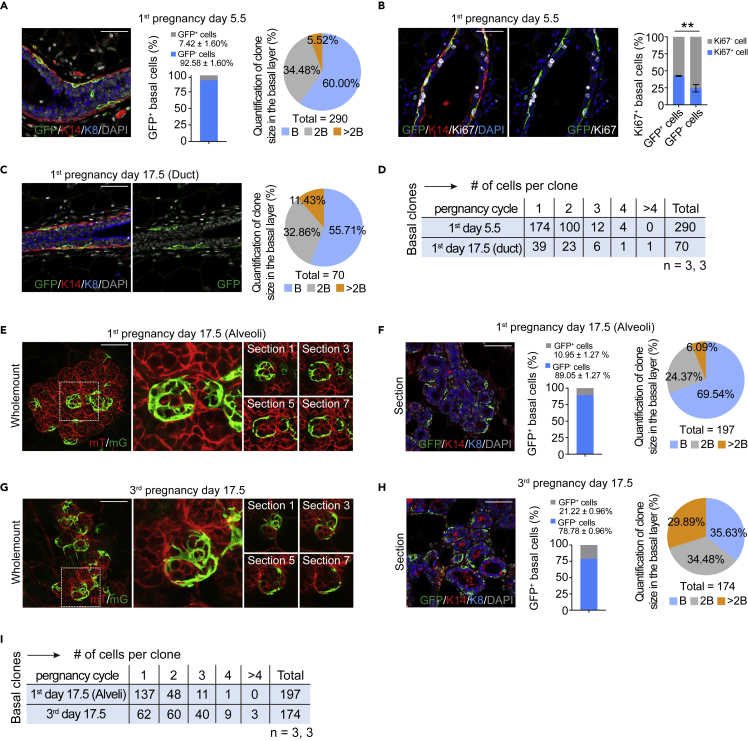

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells significantly contribute to lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy

We next sought to explore the behaviors of Nfatc1 reporter-marked epithelial cells during pregnancy (Figure S5A). Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice were administered three doses of tamoxifen at the age of 8 weeks, and then bred with WT male mice until they are pregnant. We found that basal-only GFP+ multicell clones were extensively distributed in the basal layer at pregnancy day 5.5, whereas no bilineage clones were observed (Figure 4A). Quantification for GFP+ cells of basal cells shows that 7.42 ± 1.60% of basal cells were GFP+ (Figure 4A). This result suggests that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are rapidly expanding at the early pregnancy stage. Quantification of GFP+ clones showed that the percentage of two-cell clones was 34.48% at this stage, and the proportion of multicell clones (≥3 cells) was 5.52% (Figure 4A). To validate this idea, we examined the proliferative status of GFP+ basal epithelial cells. We found that 42.43 ± 0.01% of GFP+ basal epithelial cells were Ki67+ at this stage, whereas 24.34 ± 0.03% of GFP− basal epithelial cells were Ki67+ (Figure 4B). Collectively, these data suggest that Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells and their progeny cells are more rapidly cycling relative to Nfatc1 reporter-negative basal epithelial cells at an early pregnancy stage.

Figure 4.

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells significantly contribute to lobuloalveolar development during pregnancy (see also Figure S5)

(A) Co-immunofluorescence assay of GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in mammary ducts from female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at pregnancy day 5.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis showing the percentageof GFP+ basal cells among total basal cells. A total of 2369 basal cells from three mice were quantified. Quantification analysis showing the percentages of single-cell, two-cell, and multicell basal clones. n = 3 mice. A total of 290 basal GFP+ clones were quantified

(B) Co-immunofluorescence assay of GFP (green), K14 (red), and Ki67 (white) in mammary glands from female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at pregnancy day 5.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis showing the percentage of GFP+Ki67+ cells among GFP+ cells and the percentage of GFP−Ki67+ cells among GFP− cells. A total of 175 GFP+ cells and 1,444 GFP- cells were quantified from three mice

(C) Co-immunofluorescence assay of GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in mammary ducts from female Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at pregnancy day 17.5. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis showing the percentages of single-cell, two-cell and multicell basal clones. n = 3 mice for each timepoint. The total number of basal GFP+ clones was 70

(D) Quantification analysis showing the numbers of single-cell, two-cell, and multicell basal clones for Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at indicated timepoints. n = 3 mice for each timepoint

(E and G) Wholemount confocal image for Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at the first pregnant day 17.5 (E) and third pregnant day 17.5 (G). High-magnification images were shown in the middle. Optical serial sections were shown on the right. Scale bar, 50 μm

(F and H) Co-immunofluorescence assay for GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in sections from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mammary alveoli at the first (F) and third (H) pregnant day 17.5,respectively. Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis showing the percentage of GFP+ basal cells among total basal cells. A total of 1,949 basal cells in (F) and 988 basal cells in (H) from three mice were quantified. Quantification analysis shows the percentages of single-cell, two-cell and multicell basal clones for Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at the indicated timepoints. n = 3 mice for each timepoint. The total number of basal GFP+ clones was 197 and 174 at the first (F) and third (H) pregnant day 17.5, respectively

(I) Quantification analysis showing the numbers of single-cell, two-cell and multicell basal clones for Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice at the indicated timepoints. n = 3 mice for each timepoint. Data represent the mean value ±SD ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001

At pregnancy day 17.5, we detected basal-only GFP+ clones in both mammary ducts and alveoli (Figures 4C–4F). In the mammary duct, quantification analysis showed that the proportion of two-cell GFP+ clones was 32.86% at this stage, and the proportion of multicell GFP+ clones was 11.43%. Compared with pregnancy day 5.5, the proportion of multicell GFP+ clones becomes more robust (Figures 4A and 4C). In the alveoli, GFP+ clones were clearly visible using wholemount confocal imaging (Figure 4E). Immunostaining assays of mammary tissue sections showed that most GFP+ cells were located in the basal layer of the alveoli (Figures 4F and S5B). Quantification for GFP+ cells of basal cells shows that 10.95 ± 1.27% of basal cells were GFP+ in the mammary alveoli (Figure 4F). The proportion of two-cell GFP+ clones was 24.37% and that of multicell GFP+ clones was 6.09% in the alveoli (Figures 4F and S5B). Compared with the duct, the slight decrease in the proportion of multicell GFP+ clones is likely owing to the sphere morphology of mammary alveoli. These results suggest that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are activated during early pregnancy and contributed to lobuloalveolar development.

Next, we examined the contribution of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells to lobuloalveolar development during the third round of pregnancy after TAM induction. Interestingly, more basal-only GFP+ clones were found surrounding the alveoli, as assayed by wholemount confocal imaging (Figure 4G). Co-immunofluorescence for GFP, K14, and K8 showed that most GFP+ clones were located in the basal layer (Figures 4H and S5C). Quantification for GFP+ cells of basal cells shows that 21.22 ± 0.96% of basal cells were GFP+ in the mammary alveoli (Figure 4H). The percentage of GFP+ cells increased about two-fold than that at the same stage during first pregnancy (Figures 4F and 4H). Quantification of GFP+ basal clones showed that the percentage of two-cell GFP+ basal clones was 34.48% and that of multicell GFP+ basal clones was 29.89% at the third pregnancy day 17.5, whereas they were 24.37 and 6.09%, respectively, at the same stage during the first pregnancy (Figures 4F, 4H, and 4I). Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells have stronger contribution to lobuloalveolar formation during third pregnancy than first pregnancy.

We also assessed the frequencies of Nfatc1 reporter-marked luminal cells during pregnancy. We found that the proportion of luminal GFP+ cells was less than 1% at both pregnancy day 17.5 in the first round of pregnancy and pregnancy day 17.5 in the third round of pregnancy (Figures S5D and S5E). This suggests that the contribution of Nfatc1 reporter-marked luminal cells to lobuloalveolar formation is limited. However, it is interesting that a small number of large luminal GFP+ clones containing dozens of cells were observed at pregnancy day 17.5 during both the first and third rounds of pregnancy (Figures S5D–S5G). This suggests that it is a minimal number of Nfatc1 reporter-marked luminal cells rather than most Nfatc1 reporter-negative luminal cells that are capable of generating luminal alveolar cells during pregnancy.

Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial cells are heterogeneous during pregnancy

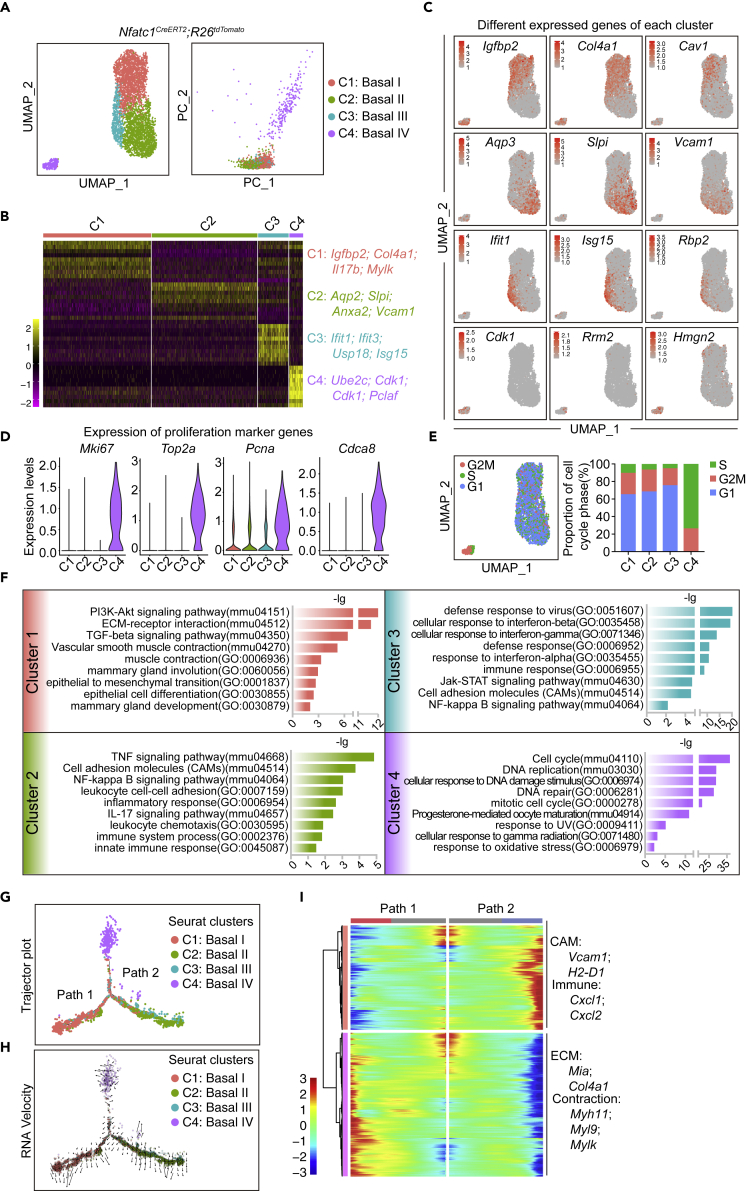

To further understand the contribution of Nfatc1 reporter-marked epithelial cells to lobuloalveolar development, we performed scRNA-seq analysis on Nfatc1 reporter-marked cell progeny at pregnancy day 14.5. Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice were administered three doses of TAM at the age of eight weeks and then bred with WT male mice until pregnancy. We isolated Lin−CD24+tdTomato+ cells from the mammary gland on pregnancy day 14.5 and subjected them to droplet-enabled 3′-end scRNA-seq. After quality control (Figure S6A), a total of 6,745 cells were used for downstream analysis. Unsupervised clustering identified seven clusters (Figure S6B), which included mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells, muscle cells, immune cells, luminal epithelial cells, and two clusters of basal epithelial cells based on signature genes (Figures S6C and S6D). After removing non-epithelial cells and luminal epithelial cells, tdTomato+ basal epithelial cells were regrouped into four clusters (Figure 5A). We utilized the differentially expressed gene signatures to assign putative cell type identities to these clusters (Figures 5B and 5C). PCA analysis showed that C4 is obviously distinct from C1 to C3 (Figure 5A). The cells in cluster 4 were enriched for the proliferating cell marker genes, Mki67, Top2a, and Pcna (Figure 5D). In agreement, cell cycle analysis showed that a majority of C4 cells were in S and G2/M phases, whereas most cells in C1–C3 were in G0/G1 phase (Figure 5E). GO and KEGG analyses showed that the pathways of cell cycle, DNA replication and DNA repair were enriched in C4 cells (Figure 5F). Thus, C4 cells are referred to “cycling basal epithelial cells.” C1 cells were enriched for genes functioning in muscle contraction, the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and the TGFβ signaling pathway, suggesting a potentially contractile feature in myoepithelial cells. C2 cells were enriched for genes in the TNF signaling pathway, cell adhesion molecules (CAM), and the NF-kB signaling pathway, suggesting a putative immune function. C3 cells were specifically enriched for gene functioning in interferon response. Therefore, Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial cells include four functionally distinct clusters during pregnancy.

Figure 5.

Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial are heterogeneous during pregnancy (see also Figure S6)

(A) UMAP and PCA plots reveal cellular heterogeneity of 4,203 tdTomato+ cells that were sorted from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mammary glands at the first pregnancy day 14.5

(B) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes in each cluster. Selected signature genes are shown on the right

(C) Feature plots showing expression distribution of selected signature genes for each cluster

(D) Violin plots showing genes functioning in cell proliferation

(E) Cell cycle analysis based on the UMAP plot of Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial cells at pregnancy day 14.5. The percentages of cells in the S, G2/M and G1 phases were quantified in each cluster

(F) KEGG and GO analysis of each cluster using the top 250 differentially expressed genes in each cluster

(G) Pseudotime ordering of Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial cells at pregnancy day 14.5.

(H) RNA velocity of Nfatc1-lineage basal epithelial cells on pregnancy day 14.5

(I) scEpath analysis identifying two gene clusters of branching genes

To examine the potential lineage relationships among these basal cell clusters, we performed pseudotime analysis, which showed that the cells in C4 were distributed in a major pseudotime trajectory that bifurcated to contractile basal epithelial cells (C1) and immunity-related basal epithelial cells (C2), whereas C3 cells were evenly distributed in the two directions (Figures 5G and S6E). We proposed a hypothesis that cycling basal progenitor cells give rise to functionally distinct differentiated cells. This idea was further supported by RNA velocity (Figure 5H). A large number of differentially expressed genes were presented along the pseudotime trajectory. We identified 1327 “branching” genes that are potentially important for the differentiation of contractile basal epithelial cells versus immunity-related basal epithelial cells (Figure 5H). In agreement, we found that genes related to vascular smooth muscle contraction (Myh11, Myl9) and ECM-receptor interaction (Col4a1, Col4a2) were upregulated in path 1 (Figures 5H and S6F). In contrast, genes related to CAM (Vcam1, H2-D1) and immune function (Cxcl1, Cxcl2) were upregulated in path 2 (Figures 5I and S6F). Taken together, our computational analysis suggests a two-branch lineage differentiation trajectory for the four distinct basal epithelial cell clusters during pregnancy.

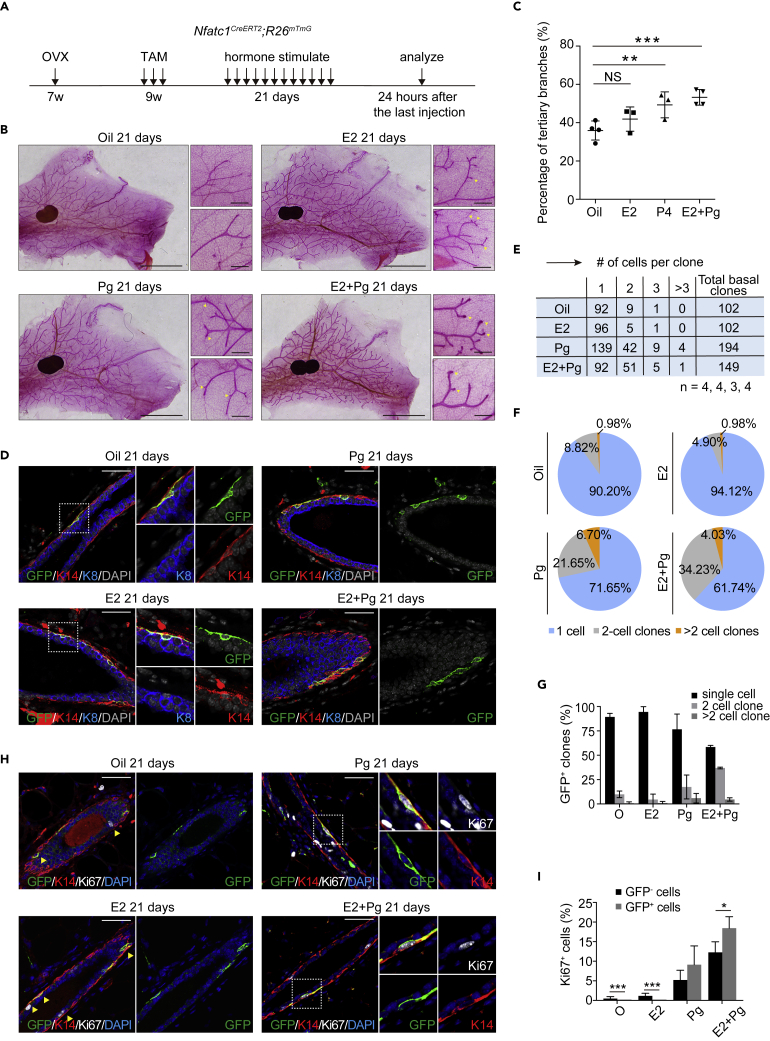

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells become activated in ovariectomized (OVX) mice in response to progesterone

Finally, we asked whether Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells can be activated in response to hormones. To this end, we surgically removed the ovaries from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG female mice as previously described (Zhao et al., 2010), to exclude the effect of endogenous hormones. After three doses of TAM induction, we intraperitoneally injected exogenous hormones (oil, E2 only, Pg only, or E2+Pg) to OVX mice every day for 21 days (Figure 6A). Upon E2+Pg treatment, enlarged terminal ducts (TDs) were extensively present in the mammary gland and the number of tertiary branches was significantly increased relative to vehicle control (Figures 6B and 6C), suggesting that E2+Pg treatment can mimic the hormone conditions of pregnancy. After 21 days of lineage tracing, the proportions of GFP+ two-cell and multicell basal clones markedly increased in response to the Pg or E2+Pg treatments compared to the vehicle control and E2 only (Figures 6D–6G). Moreover, co-immunofluorescence assay for GFP, Ki67, and K14 showed that the percentage of Ki67+GFP+ cells versus GFP+ cells is significantly higher than that of Ki67+GFP− cells versus GFP− cells under E2+Pg treatment. In contrast, the percentage of Ki67+GFP+ cells versus GFP+ cells is dramatically lower than that of Ki67+GFP− cells versus GFP− cells under conditions of no hormone treatment or only E2 treatment (Figures 6H and 6I). Taken together, these data suggest that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells are activated to rapidly divide in response to E2+Pg treatment and contribute to the expansion of mammary epithelial cells more efficiently than GFP− basal epithelial cells.

Figure 6.

Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are activated by progesterone signal in ovariectomized (OVX) mice

(A) Experimental strategy for hormone treatment and the lineage tracing

(B) Wholemount images showing mammary glands of Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG OVX mice that were stimulated for 21 days with hormones (oil, E2, Pg, and E2+Pg). Scale bar, 5 mm. For each panel, high-magnification images are shown on the right. Arrowheads indicated tertiary branches. Scale bar, 500 μm

(C) Quantification of tertiary branches in the ducts of Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG OVX mice after 21 days of stimulation with hormones (oil, E2, Pg, and E2+Pg); n = 4, 3, 3, and 4 mice, respectively

(D) Co-immunofluorescence assay of GFP (green), K14 (red), and K8 (blue) in mammary glands from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG OVX mice after 21 days of stimulation with hormones (oil, E2, Pg, and E2+Pg). Scale bar, 50 μm

(E–G) Quantification analysis shows the number (E) and the percentage (G) of single-cell, two-cell, and multicell clones in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG OVX mice after 21 days of stimulation with hormones (oil, E2, Pg, and E2+Pg); n = 4, 4, 3, and 4 mice, respectively. Another statistical method is also shown in (F). The total numbers of basal clones were 102, 102, 194, and 149

(H and I) Co-immunofluorescence of GFP (green), K14 (red), and Ki67 (white) in mammary glands from Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG OVX mice after 21 days of stimulation with hormones (oil, E2, Pg, and E2+Pg) (H). Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantification analysis shows the percentages of Ki67+ GFP+ cells versus GFP+ cells and Ki67+GFP− cells versus GFP− cells under hormone treatment. In total, 83 (Oil), 91 (E2), 180 (Pg), and 101 (E2+Pg) GFP+ cells and 567 (Oil), 1,482 (E2), 2,045 (Pg), and 1,783 (E2+Pg) GFP− cells were quantified, respectively (I). n = 3 mice for each treatment. Data represent the mean value ±SD NS, not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001

In summary, we have identified Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal mammary epithelial cells as dormant stem/progenitor cells. They divide more rapidly than Nfatc1 reporter-negative basal cells during pregnancy and contribute to the lobuloalveolar development of the mammary gland during pregnancy.

Discussion

Here we have identified Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells as dormant unipotent stem/progenitor cells in virgin mammary gland. These cells show limited contribution to mammary epithelium homeostasis, but they expand more rapidly than Nfatc1 reporter-negative cells during pregnancy to fuel mammary lobuloalveolar development. As such, this work points to the function of dormant mammary stem/progenitor cells in contributing to pregnancy-induced lobuloalveoli formation. The behaviors of Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells are reminiscent of quiescent mammary stem cells such as Lgr5+Tspan8high cells and Bcl11b+ cells. Fu et al. have identified that Lgr5+Tspan8high cells as quiescent MaSCs that located at proximal region and can be activated by ovarian hormones during pregnancy (Fu et al., 2017). Cai et al. have demonstrated that the expression level of Bcl11b, an intrinsic regulator of mammary stem cell quiescence, is markedly downregulated during pregnancy, whereas a small population of quiescent mammary stem cells express high levels of Bcl11b at homeostasis (Cai et al., 2017), supporting the idea that quiescent MaSCs are activated during pregnancy. Interestingly, scRNA-seq analysis showed that Nfatc1 is barely overlapped with Lgr5, Tsanp8, and Bcl11b. It appears that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells represent a subpopulation of dormant mammary stem cells.

In addition to quiescent MaSCs, it has been reported that WNT signaling-responsive Procr+ and Axin2+ MaSCs can also contribute to alveoli formation (van Amerongen et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). Procr+ cells were identified as multipotent mammary stem cells that is critical for both the homeostasis of mammary gland development and the alveolar formation during pregnancy (Wang et al., 2015). In comparison, Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal cells have limited contribution to the homeostasis of mammary gland development, but have bias to make contributions to the alveolar formation during pregnancy. It is worth noting that the percentage of Procr- and Axin2-marked cells remained unchanged after multiple pregnancies, but the percentage of Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells increases three times after three rounds of pregnancies. Therefore, although both active and dormant mammary stem/progenitor cells contribute to mammary lobuloalveoli formation, the dormant Nfatc1 reporter-marked stem/progenitor cells are preferentially used for multiple pregnancies. We speculate that this might represent a protective mechanism to ensure robust formation of functional mammary lobuloalveoli that secrete milk for feeding offspring, as the genomic DNA in dormant mammary stem/progenitor cells is relatively stable.

Recently, scRNA-seq analysis has been extensively utilized for characterizing mammary epithelial cells. Bach et al. demonstrated that the identity of basal epithelial cells is different at distinct developmental stages, whereas basal epithelial cells are homogeneous at the virgin or gestation stage (Bach et al., 2017). Pal et al. have also shown the same idea that basal epithelial cells are homogeneous at virginal stage (Pal et al., 2017). Interestingly, we found that Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells are generally homogeneous at the adult viginal stage, but they can be divided into two distinct groups based on the expression levels of genes functioning in muscle contraction, suggesting that there are differences in contractile capacity in different basal epithelial cells. Notably, Nfatc1-lineage cells are heterogeneous during pregnancy, including four clusters that appear functionally distinct. It appears that cycling progenitor cells bifurcate into two distinct groups, contractile basal epithelial cells, and immunity-related basal epithelial cells. We noticed that Rrm2 and Hmgn2, which are specifically and highly expressed in the population of cycling progenitor cells, function as important effectors of progesterone signaling to induce cell proliferation (Lei et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017), raising the possibility that these cycling progenitor cells are responsive to progesterone signaling. It is well known that mammary basal epithelial cells, also called myoepithelial cells, have contractile functions, which are essential for milk ejection (Haaksma et al., 2011; Sopel, 2010). However, GO and KEGG analyses indicate that a subset of basal epithelial cells might be important for immune function including leukocyte cell-cell adhesion and leukocyte chemotaxis. In agreement with this idea, the high levels of Vcam1 in this immunity cluster can mediate the accumulation of IgA antibody secreting cells (Low et al., 2010). Thus, our findings provide evidence that, in addition to the known heterogeneity that there are different subsets of MaSCs, mammary basal epithelial cells contain functionally distinct clusters.

Our work uncovers a specific population of basal mammary epithelial cells marked by the Nfatc1 expression. These cells are dormant basal stem/progenitor cells that contribute to mammary lobuloalveoli formation during pregnancy and are preferentially used for multiple pregnancies. The study provides significant insights for the cellular mechanisms of mammary lobuloalveoli formation.

Limitations of study

Our study aims to study the function of Nfatc1+ mammary stem/progenitor cells in contributing to lobuloalveoli formation during pregnancy. We label Nfatc1+ cells using Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice upon tamoxifen induction. However, it is hard to determine whether all of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal mammary epithelial cells are Nfatc1+ cells. The first reason is that Nfatc1 reporter-marked cells might contain a small population of Nfatc1+ cell-derived progeny cells, as the mammary samples were analyzed after three-time tamoxifen induction. Another reason is that only one allele of Nfatc1 can express its protein in Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mice owing to the knocking of CreERT2, leading to a remarkable reduction of Nfatc1 protein. Given that the reduced Nfatc1 protein is not detectable, it is hard to determine whether Nfatc1 reporter-marked epithelial cells are Nfatc1+ cells using double immunofluorescence for GFP and Nfatc1. Thus, we use “Nfatc1 reporter-marked mammary epithelial cells” in this study.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-keratin 8 | Abcam | Cat# ab59400; RRID: AB_942041 |

| Mouse anti-keratin 14 | Abcam | Cat# ab9220; RRID: AB_307087 |

| Chicken anti-GFP | Abcam | Cat# ab13970; RRID: AB_300798 |

| Rabbit anti-keratin 5 | Abcam | Cat# ab52635;AB_869890 |

| Mouse anti-Ki67 | Abcam | Cat# ab16667; RRID: AB_302459 |

| Mouse anti-NFAT2 | Abcam | Cat# ab2796; RRID: AB_303308 |

| Mouse anti-RFP | Invitrogen | Cat# MA5-15257; RRID: AB_10999796 |

| Anti-Rat CD45-APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-0451-82; RRID: AB_469392 |

| Anti-Rat CD31-APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-0311-82; RRID: AB_657735 |

| Anti-Rat TER 119-APC | eBioscience | Cat# 17-5921-82; RRID: AB_469473 |

| Anti-Mo/Rat CD24-PeCy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0291-82; RRID: AB_1234962 |

| Anti-Mo CD24-BV711 | BD Bioscience | Cat# 563450; RRID: AB_2738213 |

| Anti-Mo/Rat CD29-PeCy7 | eBioscience | Cat# 25-0242-82, RRID: AB_10853806 |

| Anti-Rat CD29-FITC | BD Bioscience | Cat# 561796; RRID: AB_10894590 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Tamoxifen (TAM) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# T5648 |

| 5-ethynyl-20-deoxyuridine (EdU) | Thermo Fisher | Cat# A10044 |

| Collagenase IV | Gibco | Cat# 17104019 |

| Hyaluronidase | Merck | Cat# H1115000 |

| Dispase | Stem Cell Technologies | Cat# 07913 |

| Ammonium chloride solution | Stem Cell Technologies | Cat# 07850 |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# D7291 |

| Fixable Viability Dye | eBioscience | Cat# 65-0863-14 |

| Matrigel | Corning | Cat# 356231 |

| Epicult-B medium | Stem Cell Technology | Cat# 05610 |

| Human Recombinant EGF | Stem Cell Technology | Cat# 78006.1 |

| Human Recombinant bFGF | Stem Cell Technology | Cat# 78003.1 |

| Heparin solution | Stem Cell Technology | Cat# 07980 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Click-iT EdU Alexa Flour 594 Kit | Beyotime | Cat# C0078S |

| Single cell 3 ‘Library and Gel Bead Kit V2 | 10× Genomics | Cat# 120237 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Single-cell RNA sequencing data | This paper | GEO: GSE175432 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Nfatc1CreERT2 | This paper | N/A |

| Mouse: R26mTmG | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX# 007676 |

| Mouse: R26tdTomato | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX# 007914 |

| Mouse: ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato | Zeng’s laboratory | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Genotyping primer, Nfatc1CreERT2-P1: CCTCCGGCCAATTCACAATC | This paper | N/A |

| Genotyping primer, Nfatc1CreERT2-P2: AGGCTTCGCTTTTCTTTGAG | This paper | N/A |

| Genotyping primer, Nfatc1CreERT2-P3: GGTCAGTAAATTGGAGCCCA | This paper | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 7 | GraphPad | N/A |

| Cellranger 2.0.1 | ||

| 10× Genomics | https://support.10xgenomics.com/singlecell-gene-expression/software/downloads/latest | |

| Seurat 3.2.2 | ||

| Stuart et al., 2019 | https://satijalab.org/seurat | |

| Monocle 2.10.1 | Qiu et al., 2017 | http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/monocle-release/ |

| Velocyto.R | La Manno et al., 2018 | https://github.com/velocyto-team/velocyto.R |

| FlowJo | BD | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Cong Lv (lvc@cau.edu.cn)

Materials availability

Mouse lines generated in this study are available upon request to Lead Contact provided the requestor covers shipping costs.

Experimental model and subject details

All mouse experimental procedures and protocols were evaluated and authorized according to the Beijing Regulations for Laboratory Animal Management. They were strictly in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Agricultural University (approval number: SKLAB-2019-04-03). Nfatc1CreERT2 mice were generated at Shanghai Biomodel Organism Science & Technology Development Co., Ltd. R26mTmG mice and R26tdTomato mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (stock number: 007676, 007914). ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato mice were obtained from Zeng’s laboratory at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai. Three-week old female NOD-SCID mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. Female age-matched mice were utilized for all experiments. Eight-week old female mice were utilized for short-term labeling, long-term tracing and pregnancy experiments. Seven-week old female mice were used for ovariectomized and hormone stimulation.

Method details

Lineage tracing

To label Nfatc1+ cells at homeostasis, the mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich, T5648) diluted in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich, C8267) at a dose of 4 mg pre 25 g body weight. Female mice were administered tamoxifen 3 times every other day at the age of 8 weeks. For the pregnancy experiment, female mice were administered tamoxifen 3 times every other day at the age of 8 weeks and then mated to WT mice at 2 weeks post-induction.

Hormone stimulation

The protocol for ovariectomy and hormone stimulation was described in previous reports (Zhao et al., 2010). In brief, female mice were bilaterally ovariectomized at the age of 7 weeks and then recovered for 2 weeks. After 3 dose of TAM induction every other day, the mice were intraperitoneally injected with 0.1 μg 17β-estradiol (Sigma, E2758) and/or 0.1 mg progesterone (Sigma, P0130) diluted in 100 mL corn oil every other day for 21 days. Mammary glands were harvested for further analysis 24 hours after the last induction.

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Mammary glands were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS and then processed and embedded in paraffin. Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4-μm. Tissue sections deparaffinized in xylene, and then rinsed in ethanol and washed in water. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) in a microwave. The sections were cooled naturally to room temperature (RT) and then blocked for 1 hour at RT with blocking solution. The sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and incubated with secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) for 1 hour at RT. The slides were then washed 3 times with PBS and stained with DAPI for 5 min. The sections were covered with mounting medium. Antibodies against the following proteins were used: keratin 8 (Abcam, Ab59400, 1:400), keratin 14 (Abcam, Ab9220, 1:400), GFP (Abcam, Ab13970, 1:1000), keratin 5 (Covance, 905501, 1:800), Ki67 (Abcam, Ab16667, 1:1000), NFAT2 (Abcam, Ab2796, 1:400), and RFP (Invitrogen, MA5-15257).

Wholemount confocal imaging

For wholemount confocal imaging, samples were dissected under a Leica M165FC stereomicroscope to yield portions containing a large area of ductal network (approximately 3 mm x 3 mm). Adipose tissue was removed using dissecting scissors (Rios et al., 2014). Small pieces of tissue were cleared in 80% glycerol overnight and then covered with mounting medium.

EdU labeling

EdU (Thermo Fisher, A10044) (0.2 mg per 10 g body weight) was intraperitoneally injected into 8-week-old wild-type (WT) female WT mice. The mammary glands were harvested 3 hours after injection. Co-staining of EdU and K14 was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 594 kit (Beyotime, C0078S).

Primary cell preparation

Single MECs were obtained from mammary glands following a published protocol (McNally and Stein, 2017). Mammary glands from female mice were isolated at indicated timepoints. The minced tissue was placed in culture medium (DMEM/F12 (Gibco) with 2% fetal bovine serum, 300 U/mL collagenase IV (Gibco, 17104019), and 300 U/mL hyaluronidase (Merck, H1115000)) and digested for 2 hours at 37 °C. After lysis of the red blood cells with ammonium chloride solution (Stem Cell Technologies, 07850), the suspension was incubated with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA at 37 °C for 2 min. A single-cell suspension was obtained via incubation with 1 U/mL dispase (Stem Cell Technologies, 07913) plus 0.1 mg/mL DNase I (Sigma, D7291) for 3 min with gentle pipetting, followed by filtration through 40 μm cell strainers.

Cell labeling and flow cytometry

Antibody incubation was performed on ice for 15 min in PBS with 2% fetal bovine serum. The primary antibodies employed were anti-CD24-PeCy7 (eBiosciences, 25-0291-82, 1:1000), anti-CD24-BV711 (BD Biosciences, 563450, 1:1000), anti-CD29-PeCy7 (eBiosciences, 25-0242-82, 1:1000), anti-CD29-FITC (BD Biosciences, 561796, 1:1000), anti-CD45-APC (eBiosciences, 17-0451-82, 1:1000), anti-CD31-APC (eBiosciences, 17-0311-82, 1:1000), anti-TER119-APC (eBiosciences, 17-5921-82, 1:1000) and anti-Dyeflour450 (eBiosciences, 65-0863-14, 1:1000). Flow cytometry analysis was performed using Aria SROP (BD). The data were analyzed using FlowJo software. For sorting cells, an Aria III (BD) instrument was used.

In vitro colony formation assay

Colony formation assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Stem Cell Technologies, 05610). Freshly sorted tdTomato+ and tdTomato- cells were embedded in 50% Matrigel (Corning, 356231) and cultured in mouse Epicult-B medium (Stem Cell Technology, 05610) containing 5% FBS, 20 ng/mL Human Recombinant EGF (Stem Cell Technology, 78006.1), 20 ng/mL Human Recombinant bFGF (Stem Cell Technology, 78003.1), and 4 μg/mL heparin solution (Stem Cell Technology, 07980). FACS-sorted cells were resuspended at a density of 80,000 cells/mL in chilled 100% growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience). The medium was changed every 2 days, and colonies were scored after 7∼8 days. Colony size was analyzed with Adobe Photoshop CC 2018.

Mammary fat pad transplantation

Sorted tdTomato+ cells (100, 500 or 1000 cells) were resuspended in 50% Matrigel and injected into the cleared fat pads of 3-week-old female NOD-SCID mice in a volume of 10 μL. Reconstituted mammary glands were harvested 8-10 weeks post-surgery. Outgrowths were detected under a dissection microscope (Leica M165FC) after Carmine staining. The repopulation frequency was calculated using the method at http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/soft-ware/elda/(Hu and Smyth, 2009).

Wholemount carmine staining

Inguinal mammary glands were spread on glass slides and fixed in Carnoy’s fixative (6:3:1, 100% ethanol: chloroform: glacial acetic acid) for 24 hours at room temperature, and then were washed in 70% ethanol for 15 min and rinsed with graded alcohol followed by distilled water for 5 min. The mammary gland was stained in carmine alum for 30 min and then dehydrated in 70%, 95% and 100% ethanol. Finally, the mammary gland was cleared in xylene and mounted with neutral gum.

Microscope image acquisition

All stained samples were mounted in Antifade Mounting Medium (P0128S; Beyotime), microscopy was performed at room temperature. For general immunefluorescence, image were captured by a microscope (LEICA DM6 B) with LEICA DFC9000 GT camera. 20× U-Plan-Apochromat/0.70 NA and 40× U-Plan-Apochromat/ 0.85 NA objective lenses were used. Wholemount confocal images were acquired using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Nikon A1). Fluorochromes included Alexa Fluor 488, Alexa Fluor 594, Alexa Fluor 647, and all nuclei were detected by DAPI staining. For wholemount carmine staining, image were captured by LEICA M165 FC with LEICA DFC450 C camera.

Quantification of lineage-specific cells and size of GFP+ clones

In Nfatc1CreERT2;R26mTmG mammary glands, clones were defined as cell clusters containing one or more GFP+ cells that contacted each other, as described in previous studies (Wang et al., 2015). A minimum of 3 mice with GFP+ clones on more than 20 sections were analyzed at each timepoint. For each clone, the number of cells was scored according to co-staining of K14 and K8. Images of representative clones were captured by microscopy (Leica DM6-B).

Single-cell mRNA sequencing

A single-cell suspension of the mammary gland epithelium was prepared as described above. TdTomato+ cells were sorted into EP tubes in single-cell mode using an Aria III (BD Biosciences) instrument. The collected cells were held on ice until they were loaded onto the GemCode single-cell platform (10×). Chromium Single Cell 3’ v2 libraries were sequenced with a NovaSeq 6000 sequencer with the following sequencing parameters: read 1,150 cycles; i7 index, 8 cycles; and read 2,150 cycles.

For the sample of cells isolated from 8-week-old Nfatc1CreERT2;R26tdTomato mice 48 hours after three pulses of TAM induction, raw Illumina data were demultiplexed and processed using Cell Ranger (10× Genomics version Cell Ranger 2.0.1) and then mapped to the mouse mm10 reference genome with transcriptome version mm10-1.2.0. The alignment metrics based on the web summary were as follows: total number of reads: 484,349,675; reads confidently mapped to the transcriptome: 68.8%; estimated number of cells: 2,604; mean reads per cell: 186,002; median genes per cell: 1,964; total genes detected: 18,299; and median UMI counts per cell: 5,516.

For the sample of Nfatc1 reporter-marked cell progeny at pregnancy day 14.5, raw Illumina data were demultiplexed and processed using Cell Ranger (10× Genomics version Cell Ranger 2.0.1) and then mapped to the mouse mm10 reference genome with transcriptome version mm10-3.0.0. The alignment metrics based on the web summary were as follows: total number of reads: 467,349,027; reads mapped to the genome: 91.9%; reads mapped confidently to the genome: 88.9%; reads confidently mapped to the transcriptome: 74.3%; estimated number of cells: 8,095; mean reads per cell: 57,733; median genes per cell: 1,936; total genes detected: 19,245; and median UMI counts per cell: 5,823.

Cluster identification using seurat

Seurat version 3.2.2 was used for filtering and subsequent clustering (Stuart et al., 2019). To remove partial cells and doublets, quality control was performed, in which cells with less than 500 genes or more than 6,000 genes were removed. Additionally, considering that a high proportion of mitochondrial expression in cells is indicative of cell stress/damage during isolation, cells with more than 10% unique mitochondrial molecular identifiers (UMIs) were removed from both of the samples. Gene-cell matrices were normalized and scaled in Seurat using the default parameters for UMIs. Variable genes/features were identified using a total of 2,000 features. The data were then scaled using the ScaleData function. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using the highly variable genes identified. Neighbors and clusters were identified using the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions, respectively, with dimensions specified by the user and visualized using UMAP. We used the VlnPlot function to highlight the expression of known marker genes for basal (Krt5/K5, Krt14/K14) and luminal (Krt8/K8, Krt18/K18) epithelial cells. Differentially expressed genes are shown using the Featureplot function. Cell cycle analysis was carried out in Seurat using a list of cell cycle genes. The gene list was obtained from the Regev laboratory (Kowalczyk et al., 2015). Differentially expressed genes were identified using the FindAllMarkers function with the following parameters enabled: logfc.threshold = 0.25 and min.pct = 0.25. The top 250 differentially expressed genes in each cluster were used for KEGG and GO analysis. Functional enrichment of gene sets with different expression patterns was performed using the Database for Annotation on http://kobas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/kobas3(Xie et al., 2011).

Reconstructing differentiation trajectories using monocle

To analyze the differentiation trajectories of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells and their progeny, Monocle version 2.10.1 was used on cells filtered from Seurat to infer differentiation trajectories (Qiu et al., 2017). An expression threshold of 0.01 was applied. The highly variable genes identified from Seurat were used as the ordering filter. DDRTree was used for dimension reduction. For the ordering_genes function, differentially expressed genes with p_val < 1e−10 were chosen to plot the cell trajectory. Branch analysis was also performed for differentially expressed genes with p_val < 1e−10.

Inferring cellular dynamics based on RNA velocity

We applied RNA velocity technology to infer the dynamic change process of Nfatc1 reporter-marked basal epithelial cells and their progeny. In the preparation phase, the Python version of Velocyto 0.17 was applied to generate loom files (https://velocyto.org/velocyto.py/index.html) (La Manno et al., 2018). The “run10×” parameter was set because the sequencing protocol was 10×. The “mm10_rmsk.gtf.gtf” file for removing expression duplicate units was from https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgTables. The parameters for generating the “∗.gtf” file were as follows: clade=“Mamal”; genome=“Mouse”; assembly=“Dec. 2011 (GRCm38/mm10)”; group=“All Tracks”; track=“RepeatMasker”; table=“rmsk”; region=“genome”; output format=“GTF-gene transfer format (limited)”; output file=“mm10_rmsk.gtf.” In the velocity estimation phase, velocyto.R version v0.6 was applied to estimate RNA velocity using gene-relative slopes. The embeddings were derived from the pseudotime differentiation trajectory of basal cells through Monocle. We also used this approach to estimate the distance of the cells. “fit.quantile” was set to the default value of 0.02 to perform a gamma fit to the upper/lower magnitudes of expression. The amount of time to project the cells forward “deltaT” was set to 2. The number of 10 nearest neighbors (NN) was used in the slope calculation smoothing, i.e., kCells=10. Default values were used for other parameters.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Most of the experiments were repeated at least three times and the exact n is stated in the corresponding figure legend. Quantification data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software and are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) (as indicated in the figure legends). Unpaired Student’s t-tests were performed, and asterisks indicate the levels of statistical significance (∗P < 0.05; ∗∗P < 0.01; ∗∗∗P < 0.001).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for Yi Arial Zeng for generously sharing ProcrCreERT2-IRES-tdTomato mice. Z.Y. is funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, China (82025006, 81772984), Basic Research Program (2019TC227, 2019TC088), SKLB Open Grant (2022SKLAB6-03) and Plan111 (B12008). C.L. is funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82000498). J.S. is funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12090052, 11874310). M.M. and X.D. have been funded by NIH Grant, United States (R01-GM123731). We thank the flow cytometry Core at National Center for Protein Sciences at Peking University, particularly Yang Huan and Guo Yinghua, for technical help.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: J.S, Z.Y., and C.L.; methodology: R.L., C.L., and H.H.; investigation: R.L., M.M., Z.X., X.B., P.L., and H.H.; resources: H.H. and C.F.G.-J.; writing – original draft: R.L.; visualization: R.L.; writing – review and editing: Z.X., C.L., Z.Y., J.S., X.D., and M.V.P.; funding acquisition: J.S. and Z.Y.; supervision, J.S, Z.Y., and C.L.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: March 18, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.103982.

Contributor Information

Jianwei Shuai, Email: jianweishuai@xmu.edu.cn.

Zhengquan Yu, Email: zyu@cau.edu.cn.

Cong Lv, Email: lvc@cau.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

All scRNA-seq data from this study are available at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). The accession number for data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE175432. Microscopy data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. All generic and custom R scripts are available on reasonable request. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- Asselin-Labat M.L., Vaillant F., Sheridan J.M., Pal B., Wu D., Simpson E.R., Yasuda H., Smyth G.K., Martin T.J., Lindeman G.J., et al. Control of mammary stem cell function by steroid hormone signalling. Nature. 2010;465:798–802. doi: 10.1038/nature09027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach K., Pensa S., Grzelak M., Hadfield J., Adams D.J., Marioni J.C., Khaled W.T. Differentiation dynamics of mammary epithelial cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:2128. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02001-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaas L., Pucci F., Messal H.A., Andersson A.B., Josue Ruiz E., Gerling M., Douagi I., Spencer-Dene B., Musch A., Mitter R., et al. Lgr6 labels a rare population of mammary gland progenitor cells that are able to originate luminal mammary tumours. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:1346–1356. doi: 10.1038/ncb3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S., Kalisky T., Sahoo D., Dalerba P., Feng W., Lin Y., Qian D., Kong A., Yu J., Wang F., et al. A quiescent Bcl11b high stem cell population is required for maintenance of the mammary gland. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:247–260 e245. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti R., Celia-Terrassa T., Kumar S., Hang X., Wei Y., Choudhury A., Hwang J., Peng J., Nixon B., Grady J.J., et al. Notch ligand Dll1 mediates cross-talk between mammary stem cells and the macrophageal niche. Science. 2018;360:eaan4153. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu N.Y., Nolan E., Lindeman G.J., Visvader J.E. Stem cells and the differentiation hierarchy in mammary gland development. Physiol. Rev. 2020;100:489–523. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu N.Y., Rios A.C., Pal B., Law C.W., Jamieson P., Liu R., Vaillant F., Jackling F., Liu K.H., Smyth G.K., et al. Identification of quiescent and spatially restricted mammary stem cells that are hormone responsive. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017;19:164–176. doi: 10.1038/ncb3471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein J., Fletcher S., Roth E., Wu C., Chun A., Horsley V. Calcineurin/Nfatc1 signaling links skin stem cell quiescence to hormonal signaling during pregnancy and lactation. Genes Dev. 2014;28:983–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.236554.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haaksma C.J., Schwartz R.J., Tomasek J.J. Myoepithelial cell contraction and milk ejection are impaired in mammary glands of mice lacking smooth muscle alpha-actin. Biol. Reprod. 2011;85:13–21. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.090639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens J.R., Wysolmerski J.J. Key stages of mammary gland development: molecular mechanisms involved in the formation of the embryonic mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:220–224. doi: 10.1186/bcr1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horsley V., Aliprantis A.O., Polak L., Glimcher L.H., Fuchs E. NFATc1 balances quiescence and proliferation of skin stem cells. Cell. 2008;132:299–310. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Smyth G.K. ELDA: extreme limiting dilution analysis for comparing depleted and enriched populations in stem cell and other assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 2009;347:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inman J.L., Robertson C., Mott J.D., Bissell M.J. Mammary gland development: cell fate specification, stem cells and the microenvironment. Development. 2015;142:1028–1042. doi: 10.1242/dev.087643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes B.E., Segal J.P., Heller E., Lien W.H., Chang C.Y., Guo X., Oristian D.S., Zheng D., Fuchs E. Nfatc1 orchestrates aging in hair follicle stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:E4950–E4959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320301110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk M.S., Tirosh I., Heckl D., Rao T.N., Dixit A., Haas B.J., Schneider R.K., Wagers A.J., Ebert B.L., Regev A. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals changes in cell cycle and differentiation programs upon aging of hematopoietic stem cells. Genome Res. 2015;25:1860–1872. doi: 10.1101/gr.192237.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Manno G., Soldatov R., Zeisel A., Braun E., Hochgerner H., Petukhov V., Lidschreiber K., Kastriti M.E., Lönnerberg P., Furlan A., et al. RNA velocity of single cells. Nature. 2018;560:494–498. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei W., Feng X.H., Deng W.B., Ni H., Zhang Z.R., Jia B., Yang X.L., Wang T.S., Liu J.L., Su R.W., et al. Progesterone and DNA damage encourage uterine cell proliferation and decidualization through up-regulating ribonucleotide reductase 2 expression during early pregnancy in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:15174–15192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D.D., Yue L., Yang Z.Q., Zheng L.W., Guo B. Evidence for Hmgn2 involvement in mouse embryo implantation and decidualization. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017;44:1681–1695. doi: 10.1159/000485775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low E.N., Zagieboylo L., Martino B., Wilson E. IgA ASC accumulation to the lactating mammary gland is dependent on VCAM-1 and alpha4 integrins. Mol. Immunol. 2010;47:1608–1612. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias H., Hinck L. Mammary gland development. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2012;1:533–557. doi: 10.1002/wdev.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally S., Stein T. Overview of mammary gland development: a comparison of mouse and human. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1501:1–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6475-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal B., Chen Y., Vaillant F., Jamieson P., Gordon L., Rios A.C., Wilcox S., Fu N., Liu K.H., Jackling F.C., et al. Construction of developmental lineage relationships in the mouse mammary gland by single-cell RNA profiling. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1627. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01560-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pervolarakis N., Nguyen Q.H., Williams J., Gong Y., Gutierrez G., Sun P., Jhutty D., Zheng G.X.Y., Nemec C.M., Dai X., et al. Integrated single-cell transcriptomics and chromatin accessibility analysis reveals regulators of mammary epithelial cell identity. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108273. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X., Mao Q., Tang Y., Wang L., Chawla R., Pliner H.A., Trapnell C. Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:979–982. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richert M.M., Schwertfeger K.L., Ryder J.W., Anderson S.M. An atlas of mouse mammary gland development. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 2000;5:227–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026499523505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios A.C., Fu N.Y., Lindeman G.J., Visvader J.E. In situ identification of bipotent stem cells in the mammary gland. Nature. 2014;506:322–327. doi: 10.1038/nature12948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton M., Vaillant F., Simpson K.J., Stingl J., Smyth G.K., Asselin-Labat M.L., Wu L., Lindeman G.J., Visvader J.E. Generation of a functional mammary gland from a single stem cell. Nature. 2006;439:84–88. doi: 10.1038/nature04372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehata M., Teschendorff A., Sharp G., Novcic N., Russell I.A., Avril S., Prater M., Eirew P., Caldas C., Watson C.J., et al. Phenotypic and functional characterisation of the luminal cell hierarchy of the mammary gland. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R134. doi: 10.1186/bcr3334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sopel M. The myoepithelial cell: its role in normal mammary glands and breast cancer. Folia Morphol. (Warsz) 2010;69:1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht M.D. Key stages in mammary gland development: the cues that regulate ductal branching morphogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:201. doi: 10.1186/bcr1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stingl J., Eirew P., Ricketson I., Shackleton M., Vaillant F., Choi D., Li H.I., Eaves C.J. Purification and unique properties of mammary epithelial stem cells. Nature. 2006;439:993–997. doi: 10.1038/nature04496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart T., Butler A., Hoffman P., Hafemeister C., Papalexi E., Mauck W.M., III, Hao Y., Stoeckius M., Smibert P., Satija R. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888–1902 e1821. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabula Muris Consortium. Overall coordination. Logistical coordination. Organ collection and processing. Library preparation and sequencing. Computational data analysis. Cell type annotation. Writing group. Supplemental text writing group. Principal investigators Single-cell transcriptomics of 20 mouse organs creates a Tabula Muris. Nature. 2018;562:367–372. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0590-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Amerongen R., Bowman A.N., Nusse R. Developmental stage and time dictate the fate of Wnt/beta-catenin-responsive stem cells in the mammary gland. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Keymeulen A., Rocha A.S., Ousset M., Beck B., Bouvencourt G., Rock J., Sharma N., Dekoninck S., Blanpain C. Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature. 2011;479:189–193. doi: 10.1038/nature10573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Cai C., Dong X., Yu Q.C., Zhang X.O., Yang L., Zeng Y.A. Identification of multipotent mammary stem cells by protein C receptor expression. Nature. 2015;517:81–84. doi: 10.1038/nature13851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuidart A., Ousset M., Rulands S., Simons B.D., Van Keymeulen A., Blanpain C. Quantitative lineage tracing strategies to resolve multipotency in tissue-specific stem cells. Genes Dev. 2016;30:1261–1277. doi: 10.1101/gad.280057.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie C., Mao X., Huang J., Ding Y., Wu J., Dong S., Kong L., Gao G., Li C.Y., Wei L. KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y., Tan Y.S., Haslam S.Z., Yang C. Perfluorooctanoic acid effects on steroid hormone and growth factor levels mediate stimulation of peripubertal mammary gland development in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol. Sci. 2010;115:214–224. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement