Abstract

Salicylate and acetylsalicylate slightly increased fluoroquinolone resistance in ciprofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Salicylate allowed a greater number of cells from ciprofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant strains to survive on high fluoroquinolone concentrations. Salicylate also increased the frequency with which a susceptible strain mutated to become more resistant to ciprofloxacin.

Growth of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Pseudomonas cepacia in the presence of salicylate increases quinolone resistance (4, 7, 8, 19). Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone used to treat staphylococcal infections, including infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (13). We now report the effects of salicylate on fluoroquinolone resistance in S. aureus.

Effects of salicylate and related compounds on fluoroquinolone MICs.

The S. aureus strains used in this study are described in Table 1. Stock solutions of 1 M sodium salicylate (ICN) and 1 M sodium acetate (BDH) were prepared in water. Acetylsalicylic acid (ICN) and saligenin (Sigma) stock solutions (0.5 M) were made up in ethanol. The pH of all solutions was adjusted to 7 with NaOH, and when necessary, they were filter sterilized and stored in dark containers at 4°C. Fluoroquinolone MIC determinations were performed by agar dilution on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid) in accordance with National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards guidelines and the gradient plate method essentially as described by Szybalski and Bryson (20). Ciprofloxacin gradients of 0 to 40 mg/liter were prepared in square plates (120 by 120 mm) with Luria base agar (LBA; Gibco). Overnight Luria broth (LB; Gibco) cultures inoculated with single colonies were diluted to an optical density at 625 nm of 0.1 with LB and streaked onto freshly prepared ciprofloxacin gradient plates with sterile cotton swabs. Inoculated plates were incubated at 35°C and read following 48 h of incubation. The MIC was defined as the point at which confluent bacterial growth halted. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Salicylate or related substances were added to media as required by the experiment.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, ciprofloxacin MICs, and resistance phenotypes

| Strain | Avg MIC (mg/liter) ± SD of:

|

Resistance phenotypea | Reference or source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | Norfloxacin | |||

| BB255 | 0.20 ± 0b | 0.46 ± 0.1b | 3 | |

| BB270 | 0.17 ± 0.05b | 0.60 ± 0b | Metr | 3 |

| WBG525 | 0.47 ± 0.1b | 1.30 ± 0.2b | Cdr Emr Gmr Kmr Lmr Metr Tcr | 21 |

| WBG8287 | 0.43 ± 0.05b | 1.10 ± 0.1b | Cdr Far Emr Lmr Metr | This study, clinical isolate |

| WBG9229 | 0.23 ± 0.06b | 0.80 ± 0.8b | Cdr Emr Gmr Kmr Lmr Metr Tcr | This study, clinical isolate |

| RPH593 | 12.5c | Cdr Cipr Emr Gmr Hgr Kmr Lmr Metr Rfr Tcr | This study, clinical isolate | |

| WBG8994 | 9.4c | Cdr Cipr Far Emr Gmr Kmr Lmr Metr Tcr | This study, clinical isolate | |

| WBG9011 | 11.5c | Cdr Cipr Emr Gmr Kmr Lmr Metr Tcr | This study, clinical isolate | |

| WBG9312 | 6.0c | Cdr Cipr Emr Kmr | This study, clinical isolate | |

Abbreviations: Cipr, ciprofloxacin resistance; Cdr, cadmium acetate resistance; Emr, erythromycin resistance; Far, fusidic acid resistance; Gmr, gentamicin resistance; Kmr, kanamycin resistance; Lmr, lincomycin resistance; Metr, methicillin resistance; Norr, norfloxacin resistance; Rfr, rifampin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

Agar dilution MIC.

Gradient plate MIC.

In agar, a dilution of 5 mM salicylate or acetylsalicylate caused a slight increase in the ciprofloxacin (1.4- to 2-fold) and norfloxacin (1.3- to 1.7-fold) MICs for fluoroquinolone-susceptible S. aureus strains. It also caused a slight increase in the ciprofloxacin resistance levels of ciprofloxacin-resistant strains on gradient plates (1.4- to 2.7-fold). Saligenin (2 mM) reduced norfloxacin MICs for all ciprofloxacin-susceptible strains (1.2- to 1.8-fold), reduced ciprofloxacin MICs for strains BB255 and BB270 (2.1- and 1.8-fold, respectively), did not affect the MIC for WBG525, and increased the MICs for WBG8287 and WBG9229 (1.4- and 1.6-fold, respectively). Saligenin at 5 mM completely inhibited the growth of WBG9312 and decreased ciprofloxacin gradient plate MICs for the other ciprofloxacin-resistant strains by 1.3- to 1.6-fold. Acetate did not have any affect on the fluoroquinolone MICs for any of the strains used in this study. Salicylate (pKa, 3.0), acetylsalicylate (pKa, 3.5), and acetate (pKa, 4.8) are all weak acids. This indicates that the acidity of salicylate and acetylsalicylate is not the only factor required to induce an increase in S. aureus fluoroquinolone resistance. The alcohol of salicylate, saligenin, had a tendency to decrease resistance to fluoroquinolones. Therefore, the structure of salicylate and acetylsalicylate, including a functional carboxylic acid group, is required to induce fluoroquinolone resistance in S. aureus.

In E. coli, salicylate or acetylsalicylate induces the multiple-antibiotic resistance (mar) operon, which leads to an increase in fluoroquinolone resistance (for a review, see reference 1). The expression of intrinsic multiple-antibiotic resistance in E. coli requires the AcrAB multidrug efflux system (18). Perhaps salicylate and acetylsalicylate induce a mar-like operon in S. aureus, which leads to an increase in the activity or production of the S. aureus fluoroquinolone efflux pump NorA (17) or an AcrAB homolog, causing a decrease in fluoroquinolone accumulation.

Effects of salicylate on fluoroquinolone resistance population analyses of ciprofloxacin-susceptible and -resistant strains.

Population analyses were performed at 37°C on LBA containing increasing concentrations of ciprofloxacin or norfloxacin and inoculated with serially diluted overnight LB cultures initiated with single colonies as described by Berger-Bächi et al. (3). CFU were counted after 48 h of growth.

Both ciprofloxacin-susceptible (BB255 and BB270) and -resistant (RPH593 and WBG9312) strains demonstrated heterogeneous resistance to ciprofloxacin and norfloxacin (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). The majority of BB255 and BB270 cells were killed by low levels of ciprofloxacin (0.2 mg/liter), and large proportions of the WBG9312 and RPH593 cell populations were killed by ciprofloxacin at 16 and 24 mg/liter, respectively. S. aureus also expresses heterogeneous resistance to methicillin (for a review, see reference 5), vancomycin (11), and fusidic acid (16).

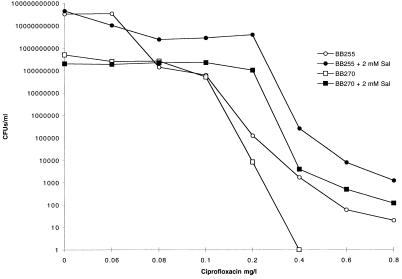

FIG. 1.

Population analysis of ciprofloxacin-susceptible strains BB255 and BB270 in the presence of ciprofloxacin performed with and without 2 mM salicylate (Sal).

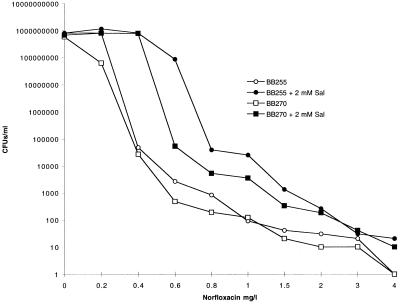

FIG. 2.

Population analysis of ciprofloxacin-susceptible strains BB255 and BB270 in the presence of norfloxacin performed with and without 2 mM salicylate (Sal).

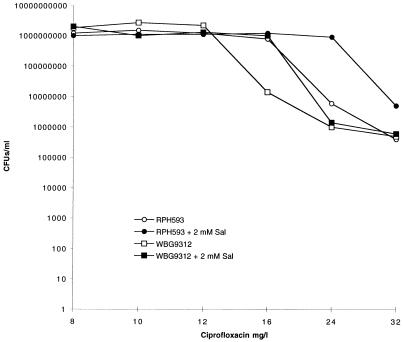

FIG. 3.

Population analysis of ciprofloxacin-resistant strains RPH593 and WBG9312 in the presence of ciprofloxacin performed with and without 2 mM salicylate (Sal).

The addition of 2 mM salicylate increased the number of BB255 and BB270 CFU appearing on ciprofloxacin- and norfloxacin-containing LBA (Fig. 1 and 2). BB270 was unable to produce colonies from the highest dilution plated (10−1) on plates containing 0.4-mg/liter ciprofloxacin, yet when salicylate was added, colonies continued to appear up to the highest concentration tested (0.8 mg/liter). On LBA containing 4-mg/liter norfloxacin alone, BB255 and BB270 were unable to produce viable cells at the highest dilution plated (10−1), yet they did so on LBA containing salicylate. The addition of 2 mM salicylate increased the number of cells surviving on LBA containing 16-mg/liter ciprofloxacin for WBG9312 and 24-mg/liter ciprofloxacin for RPH593 (Fig. 3). At 32 mg/liter the number of RPH593 cells surviving was higher in the presence of 2 mM salicylate compared to the control.

Ten colonies of BB255 were picked from LBA containing 0.2-, 0.4-, or 0.6-mg/liter ciprofloxacin with or without the addition of 2 mM salicylate, for a total of 60 isolates. All isolates were grown in three passages of drug-free LB before ciprofloxacin MICs were determined. For all colonies picked from LBA containing 0.2-, 0.4-, or 0.6-mg/liter ciprofloxacin alone and from LBA containing 2 mM salicylate and 0.4- or 0.6-mg/liter ciprofloxacin, the ciprofloxacin MICs (>0.8 mg/liter) were higher than for the parent strain. These isolates therefore express genotypic ciprofloxacin resistance. Expression of fluoroquinolone resistance in S. aureus is mediated by at least three mechanisms working in concert or separately: (i) increased fluoroquinolone efflux mediated by NorA (14, 17); (ii) amino acid substitutions in GyrA, one of the subunits of DNA gyrase (12); and (iii) amino acid alterations in GrlA, one of the subunits of topoisomerase IV (9). Since topoisomerase IV is the main target of fluoroquinolones and independent single-step mutants possess mutations in the gene encoding GrlA, grlA (15), it is probable that at least some of these BB255 single-step ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants contain grlA mutations.

For none of the colonies picked from LBA containing 2 mM salicylate and 0.2-mg/liter ciprofloxacin were the ciprofloxacin MICs increased compared to the parent strain and they therefore expressed phenotypic salicylate-inducible ciprofloxacin resistance. Salicylate also induces phenotypic low-level fluoroquinolone resistance in E. coli by inducing the mar regulon (for a review, see reference 1).

BB255 ciprofloxacin-resistant mutants arose at mutation frequencies of 5.2 × 10−8 and 1.8 × 10−9 on LBA containing 0.4- and 0.6-mg/liter ciprofloxacin, respectively, and arose on LBA containing 2 mM salicylate and 0.4- and 0.6-mg/liter ciprofloxacin at mutation frequencies of 5.5 × 10−6 and 1.8 × 10−7, respectively. This data demonstrates that growth in the presence of both ciprofloxacin and salicylate increases the mutation frequency to higher ciprofloxacin resistance levels. Mutations in marO or marR, the operator and repressor of the mar operon, lead to a multiple-antibiotic resistance phenotype in E. coli (6), including increased resistance to fluoroquinolones (for a review, see reference 1). Mar mutants of E. coli mutate more readily to higher fluoroquinolone resistance levels (10). This provides additional evidence that a possible mar-like operon is located within the S. aureus genome.

Concluding remarks.

Salicylate and acetylsalicylate are frequently ingested for therapeutic reasons. The concentrations of these substances used in this study are similar to those recommended for the treatment of rheumatic fever (2). Since salicylate is known to induce multiple-antibiotic resistance in other bacteria, the effects of salicylate and related compounds on S. aureus resistance levels to additional antistaphylococcals should be investigated.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Australian Research Council for funding this research project.

We thank John Pearman of Royal Perth Hospital for strains used in this study. We also thank Prerna Rajput and Bradley Shelton for preliminary data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alekshun M N, Levy S B. Regulation of chromosomally mediated multiple resistance: the mar regulon. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2067–2075. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Axon J M C, Huskisson E C. Use of aspirin in inflammatory diseases. In: Vane J R, Botting R M, editors. Aspirin and other salicylates. London, England: Chapman & Hall; 1992. pp. 295–320. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berger-Bächi B, Strässle A, Gustafson J E, Kayser F H. Mapping and characterization of multiple chromosomal factors involved in methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1367–1373. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns J L, Clark D K. Salicylate-inducible antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas cepacia associated with absence of a pore-forming outer membrane protein. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2280–2285. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers H F. Methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1988;1:173–186. doi: 10.1128/cmr.1.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S P, Hächler H, Levy S B. Genetic and functional analysis of the multiple-antibiotic-resistance (mar) locus in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:1484–1492. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.5.1484-1492.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen S P, Levy S B, Foulds J, Rosner J L. Salicylate induction of antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli: activation of the mar operon and a mar-independent pathway. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7856–7862. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7856-7862.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domenico P, Hopkins T, Cunha B A. The effect of sodium salicylate on antibiotic susceptibility and synergy in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1990;25:343–351. doi: 10.1093/jac/26.3.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrero L, Cameron B, Manse B, Lagneaux D, Crouzet J, Famechon A, Blanche F. Cloning and primary structure of Staphylococcus aureus DNA topoisomerase IV: a primary target of fluoroquinolones. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:641–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldman J D, White D G, Levy S B. Multiple antibiotic resistance (mar) locus protects Escherichia coli from rapid cell killing by fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1266–1269. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hiramatsu K, Aritaka N, Hanaki H, Kawasaki S, Hosoda Y, Hori S, Fukuchi Y, Kobayashi I. Dissemination in Japanese hospitals of strains of Staphylococcus aureus heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Lancet. 1997;350:1670–1673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07324-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito H, Yoshida H, Bogaki-Shonai M, Niga T, Hattori H, Nakamura S. Quinolone resistance mutations in the DNA gyrase gyrA and gyrB genes of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2014–2023. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neu H C. Ciprofloxacin: an overview and prospective appraisal. Am J Med. 1983;83(Suppl. 4A):395–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng E Y W, Trucksis M, Hooper D H. Quinolone resistance mediated by norA: physiological characterization and relationship to flqB, a quinolone resistance locus on the Staphylococcus aureus chromosome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1345–1355. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.6.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ng E Y W, Truckis M, Hooper D C. Quinolone resistance mutations in topoisomerase IV: relationship to the flqA locus and genetic evidence that topoisomerase IV is the primary target and DNA gyrase is the secondary target of fluoroquinolones in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1881–1888. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.8.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien F G, Botterill C I, Endersby T G, Lim R L G, Grubb W B, Gustafson J E. Heterogeneous expression of fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus with plasmid or chromosomally encoded fusidic acid resistance genes. Pathology. 1998;30:299–303. doi: 10.1080/00313029800169486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohshita Y, Hiramtsu K, Yokota T. A point mutation in norA gene is responsible for quinolone resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;172:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91549-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okusu H, Ma D, Nikaido H. AcrAB efflux pump plays a major role in the antibiotic resistance phenotype of Escherichia coli multiple-antibiotic-resistance (Mar) mutants. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:306–308. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.306-308.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumita Y, Fukasawa M. Transient carbapenem resistance induced by salicylate in Pseudomonas aeruginosa associated with suppression of outer membrane protein D2 synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2743–2746. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Szybalski W, Bryson V. Genetic studies on microbial cross resistance to toxic agents. I. Cross resistance of Escherichia coli to fifteen antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1952;64:489–499. doi: 10.1128/jb.64.4.489-499.1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Udo E E, Al-Obaid I A, Jacob L E, Chugh T D. Molecular characterization of epidemic ciprofloxacin- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains colonizing patients in an intensive care unit. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3242–3244. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3242-3244.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]