Abstract

The lymph node microenvironment is extremely dynamic and responds to immune stimuli in the host by reprogramming immune, stromal, and endothelial cells. In normal physiological conditions, the lymph node will initiate an appropriate immune response to clear external threats that the host may experience. However, in metastatic disease, cancer cells often colonize local lymph nodes, disrupt immune function, and even leave the lymph node to create additional metastases. Understanding how cancer cells enter, colonize, survive, proliferate, and interact with other cell types in the lymph node is challenging. Here, we describe the use of photoconvertible fluorescent proteins to label and trace the fate of cancer cells once they enter the lymph node.

Keywords: Photoconvertible proteins, Lymph node, Metastasis, Intravital imaging, Circulating tumor cells, Photodiode, Dendra2, Confocal microscopy

1. Introduction

Metastatic cancer cells exit the primary tumor via blood and lymphatic vessels. Oftentimes the first site of colonization is the regional lymph node [1, 2]. Once tumor cells enter the lymph node through an afferent lymphatic vessel, they begin to proliferate in the subcapsular sinus and gradually invade into the parenchyma as the metastatic colony gets larger [3]. Not all cancer cells that enter the lymph node survive the new microenvironment, particularly as the lymph node is a major site for the initiation of immune responses [4]. The difficulty in studying the biology of spontaneous lymph node metastasis has left many questions unanswered. What makes some cancer cells thrive in this microenvironment versus others that do not? How do cancer cells interact with other cell types in the lymph node, including immune, stromal, and endothelial cells? What makes some cancer cells exit the node to colonize distant organs [4, 5]?

Given the dynamic response of the lymph node to changes in the host during cancer progression, it is extremely challenging to address these unanswered questions, each of which have clinical implications for eradicating cancer from lymph nodes, generating anti-tumor immune responses, and inhibiting cancer progression. Several studies have begun to elucidate the role of signaling pathways, including chemokine-chemokine receptor signaling, that regulate cancer cell entry into the lymph node and further migration in the node [5–7]. Further studies are warranted to understand the molecular mechanisms that regulate cancer cell survival, proliferation, and migration in the lymph node.

The dynamic and highly orchestrated process of cancer cell metastasis is challenging to visualize in real-time. However, recent advances in imaging technologies have made it possible to study this process in a live animal [8, 9]. Once cancer cells in the primary site invade vessels and colonize a secondary site, it can be difficult to follow the fate of metastatic cancer cells longitudinally. To overcome this challenge, light-responsive proteins can be used as a molecular tag to identify cancer cells that arrive in a secondary site [10, 11]. There are three kinds of light-responsive fluorescent proteins that can be used [12, 13]. First, photoactivatable fluorescent proteins can be switched “on” or turned from a nonfluorescent state to emit fluorescence at a specific wavelength by irradiation with light in the blue/violet spectrum. Examples of these fluorescent proteins are PA-GFP, PAmCherry, and PAmKate. Second, photoconvertible fluorescent proteins such as Dendra2, Kaede, and EosFP can change their fluorescence emission maximum from one wavelength to another (switch colors) after conversion with light at a specific wavelength. Finally, photoswitchable fluorescent proteins can be switched “on” and “off” by specific light pulses at different wavelengths. Examples of this type of light-responsive fluorescent protein include Dronpa and Kindling FP. Additional details for each category of fluorescent proteins are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details for light-responsive fluorescent proteins

| Protein | Exmax (nm) | Emmax (nm) | Structure | Activation Wavelength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

Photoactivatable proteins Photoactivatable proteins often display reduced brightness compared to traditional fluorophores and have reduced photostability. | ||||

| PA-GFP | 400 504 |

515 517 |

Monomer | Violet |

| PAmCherry | 404 564 |

595 | Monomer | 350–400 nm |

| PAmKate | 586 | 628 | Monomer | 405 nm |

|

Photoconvertible proteins These proteins emit fluorescence in the nonconverted state, making it easier to define regions of interest. Tetrameric proteins may not be optimal when expressed in cells. | ||||

| Dendra2 | 490 553 |

507 573 |

Monomer | 405 nm or 488 nm |

| Kaede | 508 572 |

518 580 |

Tetramer | Violet |

| EosFP | 506 571 |

516 581 |

Tetramer | 390 nm |

|

Photoswitchable proteins Versatile when switching between the “on” and “off” states without photobleaching. | ||||

| Dronpa | 503 | 518 | Monomer | Violet/Blue |

| Kindling FP | 580 | 600 | Tetramer | Green/450 nm |

Several advances have been made in intravital microscopy that enable real-time visualization of cell-cell interaction in a live animal. In the case of cancer, understanding how tumor cells interact with each other or with other cell types in a specific organ is critical to advancing our knowledge and exploiting dependent pathways for cancer therapy.

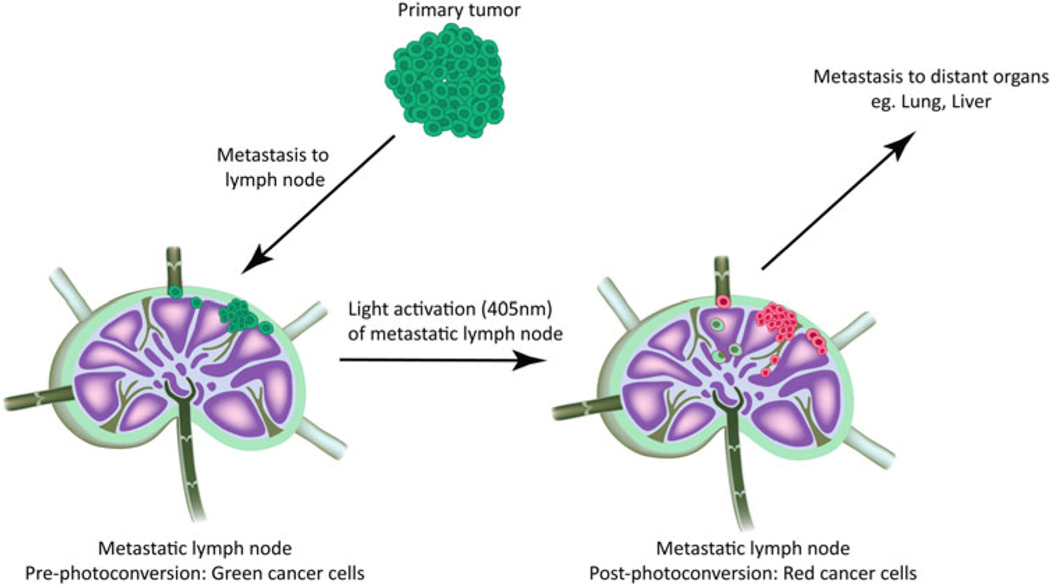

In this chapter, we describe a method for tracing cancer cell fate and progression to distant organs following their arrival in a lymph node (Fig. 1). Cancer cells engineered to express a photoconvertible protein that enables short-term fate mapping are used in this method. We generated stable cancer cell lines expressing Dendra2 [14], a photoconvertible protein that natively fluoresces green but, upon light activation, converts to red fluorescence. This technology allows specifically labeled cells that entered the lymph node to be monitored for their migratory behavior and interaction with other cell types in the lymph node. In addition, this method provides the ability to track the movement of metastatic cancer cells from the lymph node to distant organs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fate-mapping cancer cells in the lymph node. To trace cancer cells from the lymph node to distant organs, we engineer murine cancer cell lines to express the photoconvertible protein Dendra2. In the absence of light conversion, the primary tumor fluoresces green. Spontaneous lymphatic metastasis from the primary tumor results in cancer cell colonization in the lymph node in the mouse models we tested, which include B16F10 (melanoma), 4T1 (breast cancer), and SCCVII (squamous cell carcinoma). Green fluorescently labeled cancer cells in the lymph node are photoconverted to red fluorescence using a 405 nm photodiode. The red fluorescently labeled cancer cells in the lymph node are followed over time to trace their path inside the lymph node and beyond to distant organs such as the lung and liver. This is a powerful technology that can be utilized to trace the movement of cancer cells from a specific location through the complex metastatic cascade to their eventual colonization of secondary sites

2. Materials

1. Animal Models and Cell Lines

Mice: C57Bl/6, Balb/c, and C3H strains (see Note 1).

Cell lines: B16F10 melanoma cells, 4T1 mammary carcinomacells, and SCCVII squamous cell carcinoma cells (originally established in the Edwin Steele Laboratories, Massachusetts General Hospital [MGH], Boston). Store cell line stocks in aliquots of 1×106 cells/cryogenic vial in liquid nitrogen.

Complete cell culture medium: Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’sMedium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS).

2.2. General Purpose and Animal Surgery Materials

Gauze sponge.

Scalpel.

Chronic lymph node window (CLNW) for longitudinal intravital imaging [15], consisting of custom-made titanium frame, custom-made titanium ring, and tension C-ring insert.

5–0 polypropylene sutures.

Sterile cotton swabs.

11.7 mm round coverslips.

1 ml insulin syringes.

Microdissection scissors.

Surgical scissors.

2 Dumont forceps.

Heating pad.

Needle holder.

Surgical tray.

Nitrile gloves.

Cautery.

Surgical bright-field microscope.

Shaving device.

Laminar flow hood.

Surgical tape.

Sterile saline for injection.

Sterile water.

Scale.

Ketamine (controlled substance).

Xylazine.

Buprenorphine hydrochloride.

Acetaminophen.

Ophthalmic ointment.

Hair removal cream.

Glue.

Tetramethylrhodamine-dextran (two million MW) for labeling blood vessels.

Flow cytometry buffer: 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS)

2.3. Equipment and Materials for Photoconversion and Intravital Imaging

Photodiode emitting 405 nm light custom-made to focus light on the lymph node of interest, with a rheostat to control light intensity and time.

Aluminum foil.

Tape.

Plasmid containing Dendra2 for cytoplasmic overexpression in cancer cell lines (see Note 2).

Plasmid containing Dendra2-H2B for nuclear overexpression in cancer cell lines (see Note 2).

Custom-built multiphoton laser-scanning microscope (adapted from the Olympus 300) [16] and a broadband femtosecond laser source (i.e., high performance Mai Tai®)

2.4. Tissue Staining and Clearing

Anti-CD31 antibody (Clone 390, BioLegend): secondary antibody, fluorescent tagged anti-rat.

Anti-cytokeratin antibody (Clone C-11, Sigma): FITC conjugated antibody, no secondary antibody required.

Anti-podoplanin antibody (Clone 8.1.1): secondary antibody, fluorescent tagged anti-Syrian hamster.

Anti-Lyve-1 antibody (polyclonal; Catalog #NB600–1008, Novus Biologicals): secondary antibody, florescent tagged anti-rabbit.

4% formaldehyde.

Phosphate buffered saline (PBS): NaCl (0.137 M), KCl (0.0027 M), Na2HPO4 (0.01 M), KH2PO4 (0.0018 M).

Red blood cell (RBC) Lysing Buffer: Proprietary Buffer (ThermoFisher Scientific).

45 μm nylon mesh filter.

Permeabilization buffer: 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS.

PBS glycine buffer (10×): Add NaCl (3.8 g), Na2HPO4 (9.38 g), NaH2PO4 (2.07 g), and glycine (37.5 g) to 500 ml of distilled water. Adjust pH to 7.4. When making working solution, dilute to 1× using distilled water.

Immunofluorescence (IF) wash buffer (10×): Add NaCl (38 g), Na2HPO4 (9.38 g), NaH2PO4 (2.07 g), NaN3 (2.5 g), bovine serum albumin (BSA) (5 g), Triton X-100 (10 ml), and Tween 20 (2.05 ml) to 500 ml of distilled water. Adjust pH to 7.4. When making working solution, dilute to 1× using distilled water.

Blocking buffer: Prepare 1× IF wash buffer supplemented with 10% normal donkey serum.

Tetrahydrofuran (THF).

Dichloromethane (DCM).

1:2 solution of benzyl alcohol and benzyl benzoate.

3. Methods

The use of photoconvertible proteins to trace cancer cells in vivo is a powerful method to address unanswered questions in the complex metastatic process. We have validated the method described here in experiments with syngeneic mouse models that promote spontaneous lymphatic metastasis from the primary tumor to the draining lymph node. We describe the steps involved in the major procedures for this method, including in vitro measurement of photoconversion efficiency, tumor inoculation/growth and spontaneous lymph node metastasis, CLNW implantation, photoconversion of cancer cells in the lymph node (see Note 3), intravital microscopy, and tissue staining and clearing.

3.1. In Vitro Measurement of Photoconversion Efficiency

Engineer cancer cell lines to stably express Dendra2 (cytosolic) or Dendra2H2B (nuclear) protein (see Notes 1 and 2). Prior to light activation, these cell lines fluoresce by emitting green light (507 nm).

- Test the photoconversion efficiency of the Dendra2-expressing cell lines in vitro prior to inoculation in the mouse.

- Grow Dendra2-expressing cell lines in a monolayer in a 6-well tissue culture-treated plate.

- Confirm by confocal microscopy that the majority of cells express green fluorescently labeled Dendra2 (cytosolic) or Dendra2-H2B (nuclear) prior to photoconversion.

- Perform a focused light activation in a predetermined region of interest using either the 405 nm or 488 nm laser, and measure the photoconversion efficiency in vitro (see Note 4).

3.2. Tumor Inoculation, Growth, and Spontaneous Lymph Node Formation

Once the efficiency and duration of the photoconversion are established in vitro, inoculate preswitched tumor cells into mice.

Perform orthotopic implantation of tumor cells by injecting a cell pellet (1 × 105 cells in 30 μl of DMEM medium) into syngeneic mouse strains (see Note 5).

Measure the primary tumor three times per week and once it reaches a size of ~250 mm3 (approximately Day 7–10 post-inoculation of B16-F10 melanoma cells), resect the tumor mass using aseptic techniques, taking care to minimize damage to the surrounding tissue (see Note 6). Keep the wound site sterile and close with sutures.

Allow time for lymph node metastases to become established. B16-F10 cells should colonize and become established in the draining lymph node as a result of spontaneous lymphatic metastasis from the primary tumor ~4–5 days after primary tumor resection. Lymph node metastasis is typically observed in ~70% of B16F10 implanted mice.

3.3. Chronic Lymph Node Window Implantation

Prepare the mouse with lymph node metastasis for surgery by placing it on a scale to weigh, and administer ketamine-xylazine mixture at 100 mg/10 mg per kg of body weight).

Place the mouse on a heating pad for the remainder of the surgery to maintain the body temperature at 37°C.

Identify the location of the tumor draining lymph node by holding skin over the inguinal lymph node away from the body and using a bright light (see Note 7).

Place two screws through the most lateral holes in the CLNW, and secure them by tightening a nut to the frame. Position the lymph node in the center of the titanium window and pierce a hole in the skin using a scalpel. Place the screw through the skin-hole and repeat for the second screw.

Place the second CLNW on top of the first with the skin in between and secure the CLNW with two additional nuts.

Place the mouse under a bright-field surgical microscope, and carefully remove the top ventral skin (~5 mm diameter) with microdissection scissors. The lymph node will be visible once the upper dermis is open and the surrounding fat tissue is cleared by blunt dissection.

Apply sterile saline to the exposed lymph node area to prevent dehydration. Carefully place a coverslip that fits in the groove of the CLNW and secure with a tension C-ring (see Note 8).

Subcutaneously administer buprenorphine hydrochloride at 10 ml/kg of body weight once post-operatively right before the animal wakes up. Monitor the mice daily post-surgery and administer buprenorphine if the animals show signs of pain or distress.

3.4. Photoconversion of Cancer Cells in the Lymph Node

Prior to photoconversion, anesthetize the mouse using ~3–4% isoflurane for induction. Then decrease the level to ~1.5% isoflurane after confirming the mouse is relaxed and has a steady respiration rate. Maintain a constant supply of isoflurane by using a nose cone fitted snugly around the nose of the mouse (see Note 9).

Place the anesthetized mouse on its dorsal side with the inguinal lymph node and the CLNW facing upward. Secure the animal by taping its legs to a platform on the lab bench.

Once the mouse is correctly positioned, assemble the 405 nm photodiode by connecting it to the external power supply (see Note 10).

- Optimize the timing and intensity of light activation by performing the steps below on multiple mice with different settings (see Note 11):

- Image each experimental mouse on a multiphoton microscope to confirm the presence of cancer cells and the absence of any spontaneous photoconversion. To detect lymph node metastasis, the laser should be set to 840 nm with 30 mW power on the sample. The 405 nm filter is used to detect the lymph node capsule by second harmonic generation (SHG). Nonconverted green cancer cells can be detected with a 488 nm filter, and photoconverted red cancer cells can be detected using a 540 nm filter.

- Post-photoconversion, place each mouse back on the multiphoton microscope and obtain images using 840 nm laser light at 30 mW on-sample power to confirm photoconversion efficiency.

- Images should be obtained using a 488 nm filter (to monitor green fluorescence in cancer cells), a 540 nm filter (to monitor red fluorescence in cancer cells postphotoconversion), and a 405 nm filter to visualize the collagen fibers in the capsule of the lymph node.

- The distinct pattern of the collagen fibers in the capsule enable this structural feature of the node to be identified and serve as a landmark when repeated imaging is performed on the same node.

Quantify the fraction of photoconverted cells (see Note 13) by calculating the number of red cancer cells (photoconverted cells)/number of green or red cancer cells (total number of metastatic cancer cells).

Obtain repeated multiphoton images 4–5 days post light activation to confirm the presence of photoconverted cells in the lymph node longitudinally.

To determine whether cancer cells from the lymph nodeescape, collect blood and distant organs (such as lungs and liver) to monitor the presence/absence of green and red circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

- To analyze if CTCs from the blood have transited the lymphnode, collect whole blood by cardiac puncture from mice that had their lymph nodes photoconverted. As control, collect whole blood from mice that did not have light activation of the lymph node.

- Transfer whole blood (~1 ml) immediately to a roundbottom polystyrene tube and add 4 ml of 1 RBC lysing buffer. Mix the contents in the tube well while making sure not to vortex or pipette vigorously as that may damage any CTCs in the sample.

- Incubate the tube contents for 4 min at room temperature.

- After lysis, centrifuge the tube at 500 × g for 5 min, and decant the supernatant.

- Repeat the RBC lysing procedure until the supernatant is clear and lysing is complete.

- Spin down at 500 × g for 5 min, and resuspend the cell pellet in PBS.

- After counting the cells in the pellet, resuspend at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml in flow cytometry buffer. The cells should be filtered through a 45 μm nylon mesh filter and stored on ice prior to flow cytometry.

- Analyze the resuspended cells by loading and processing the samples on a flow cytometer (see Note 14).

- To analyze distant organs such as the liver and lung for thepresence or absence of photoconverted cancer cells, rinse the organs in PBS following harvest and store in a petri dish on ice until further processing.

- Gross examination of metastatic lesions can be assessed using a fluorescence dissection microscope, or higher resolution images can be obtained by confocal microscopy.

- Record images of metastatic lesions, and quantify the presence or absence of photoconverted (red) cancer cells (see Note 15).

- Detailed analysis of distant organs can be further performed by clearing the tissues as detailed in Subheading 3.5, followed by imaging the cleared tissue to detect the presence of micrometastatic lesions.

Table 2.

Recommended timing and 405 nm photodiode power to test when optimizing conditions that yield the most efficient photoconversion in a specific system

| Experimental mouse | Exposure time (in seconds) | Power intensity (mW) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 11 |

| 2 | 60 | 11 |

| 3 | 90 | 11 |

| 4 | 180 | 11 |

| 5 | 180 | 7 |

| 6 | 180 | 9 |

| 7 | 180 | 11 |

| 8 | 180 | 13 |

3.5. Tissue Staining and Clearing

Once the experiment is complete and the animals are sacrificed, the and Clearing lymph nodes and other organs should be harvested and further processed for staining and clearing. Although the lymph node microenvironment is constantly changing throughout the experiment, staining the tissue at the end-point to observe blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs) will give a clear snapshot of the interaction of these cell types with the cancer cells. Based on the mouse model used, distant organs can be harvested and metastatic colonies analyzed for the presence or absence of photoconverted cancer cells.

Fix the lymph nodes (or any other organ that requires clearing,staining and imaging to assess distant metastases) with 4% formaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature.

Rinse with PBS and permeabilize with 0.5% Triton X-100 inPBS at 4 °C overnight.

Rinse three times with 1× PBS–Glycine wash buffer for 20 min each at room temperature.

Incubate samples with Blocking buffer for 1 h at roomtemperature.

Incubate samples with primary antibody at 4 °C for 48–72 h. For the metastatic lymph node, stain cancer cells (anticytokeratin), blood vessels (anti-CD31), FRCs (antipodoplanin), and lymphatic vessels (anti-Lyve-1) to clarify the location of cancer cells as well as any cellular interaction cancer cells may have with other structures in the lymph node.

Wash 3× with 1× IF wash buffer for 3 min/wash.

Incubate samples with appropriate secondary antibody at 4 °C overnight.

Rinse 3× with PBS for 3 min/rinse.

For tissue clearance, incubate tissues in the following solutionsin glass containers: 50% THF for 30 min, 80% THF for 30 min, 100% THF for 30 min, 100% THF for 30 min, 100% THF for 30 min, 100% DCM for 30 min.

Store tissue in 1:2 solution of benzyl alcohol and benzyl benzoate until the time of imaging.

Footnotes

Notes

For relevant studies of lymph node metastasis, it is critical touse immune-competent mice with a complete immune system. We use 8–10-week-old or older mice that weigh at least 25 g. For our tumor models, we have used syngeneic mouse strains paired with murine cancer cell lines, including C57Bl/6 mice for B16F10 (melanoma), Balb/c mice for 4T1 (breast cancer) and C3H mice for SCCVII (squamous cell carcinoma). All mice were bred and housed in our facility at MGH.

The choice of subcellular localization of Dendra2 fluorescentprotein will depend on the goal of the experiment. If Dendra2 will be used to detect the presence or absence of photoconverted cells in a specific organ, then engineering the cancer cells to express Dendra2 localized to the nucleus (Dendra2H2B) is preferred. Nuclear localization of Dendra2 intensifies the fluorescence in a confined space. If Dendra2 will be used to visualize cells by intravital microscopy, then using the cytosolic version of the protein is preferred.

The photoconvertible protein-Dendra2 fluoresces green priorto light activation and converts to red fluorescence post light activation. Although the conversion of the protein is permanent, the gene is not altered so the cell and its daughter cells will continue to make Dendra2 that fluoresces green. As photoconverted cancer cells divide, the red fluorescence will dilute out with each cell division. In addition, photoconverted protein will degrade with time. This is a major limitation of this technology and hence cannot be used for long-term cell fate mapping.

In vitro, cancer cells should efficiently switch from green to redfluorescence in 30 s to 1 min using 30% laser power on a confocal microscope. The duration and laser power for the photoconversion can be optimized for each specific cell line and system.

B16F10 is implanted intradermally in the flank of C57BL/6 mice, 4T1 is implanted in the fourth mammary fat pad of Balb/ c mice, and SCCVII is implanted subcutaneously in the flank of C3H mice. As an example for highlighting the implementation of this protocol, we will describe its use in experiments with the B16F10 melanoma cell line. Each cancer line will have its own growth kinetics and rate of spontaneous metastasis.

There is a constant inflow of cancer cells into the lymph nodefrom the primary tumor as a result of spontaneous lymphatic metastasis. Hence, we first resect the primary tumor prior to photoconversion of metastatic cancer cells in the lymph node. This allows us to restrict any potential new cancer cells from arriving in the node after light activation.

The tumor draining lymph node is usually inflamed and henceshould be easy to identify by palpation.

The photoconversion of the lymph node can be done in thepresence or absence of the CLNW. It is advised to perform this procedure initially with a window so the photoconversion efficiency of cancer cells in the lymph node can be assessed in real-time. Once the exposure time and light intensity have been established, the procedure can be performed in the absence of the window by focusing the diode directly on the lymph node through the skin. Care must be taken to remove any hair that might obscure light penetration to the lymph node.

It is advised to perform the photoconversion of cancer cells2–3 days post CLNW implantation to allow the animal to recover from surgery, minimize inflammation, and enable any ruptures in capillary blood vessels to heal.

Make sure to wear UV protective glasses while handling thephotodiode. Always take care to position the photodiode away from personnel. Additionally, the process of light activation in the lymph node should be carefully carried out to avoid light penetration to any other part of the animal’s body. We cover the mouse with aluminum foil and expose only the lymph node area to the photodiode. The photodiode can be engineered to focus the light in a limited area and restrict photoconversion of any circulating cancer cells outside the node.

The settings that work best in our laboratory for photoconverting cancer cells in the lymph node with a 405 nm photodiode are 11 mW for 180 s for 5 consecutive days.

Photoconversion of Dendra2-expressing cancer cells in vitro isachievable in 30 s to 1 min using either a photodiode or focused confocal laser at 405 nm or 488 nm. However, the same parameters cannot be used for in vivo photoconversion. The time and laser intensity needs to be optimized for photoconversion in vivo. The photoconversion settings depend on several factors including depth of cancer cells from the surface, obstruction of light due to surrounding tissue and fat, and the number of metastatic cancer cells in the lymph node.

The photoconversion efficiency of cancer cells in the lymphnode is important to quantify by counting the number of green and red cancer cells post-photoconversion. It is important to note that photoconverted cells will fluoresce green and red, though the intensity of the green fluorescence is reduced compared to that in prephotoconverted cells. Information on photoconversion efficiency will enable one to correctly interpret data obtained from CTCs and distant organs.

The Amnis ImageStream imaging flow cytometer has a highspeed camera that captures an image of every event that passes through the flow cytometer. This technology enables identification of CTCs based on size exclusion using flow cytometry as well as identification of green and red cancer cells (CTCs) from the images obtained.

Due to the limited time that photoconverted cancer cells retainred fluorescence, it is not always possible to determine if a large green metastatic lesion identified in the lung or liver initially fluoresced red. Once cancer cells are photoconverted and fluoresce red, they do not pass on the red fluorescence to the daughter cells. As a photoconverted cancer cell keeps dividing, the red fluorescence dilutes out. To overcome this caveat in the system, a permanent photoconversion technology must be engineered for long-term fate-mapping.

References

- 1.Cady B (2007) Regional lymph node metastases, a singular manifestation of the process of clinical metastases in cancer: contemporary animal research and clinical reports suggest unifying concepts. Cancer Treat Res 135:185–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris RL, Lotze MT, Leong SP et al. (2012) Lymphatics, lymph nodes and the immune system: barriers and gateways for cancer spread. Clin Exp Metastasis 29(7):729–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong HS, Jones D, Liao S et al. (2015) Investigation of the lack of angiogenesis in the formation of lymph node metastases. J Natl Cancer Inst 107(9):djv155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira ER, Jones D, Jung K et al. (2015) Thelymph node microenvironment and its role in the progression of metastatic cancer. Semin Cell Dev Biol 38:98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawada K, Taketo MM (2011) Significanceand mechanism of lymph node metastasis in cancer progression. Cancer Res 71 (4):1214–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Podgrabinska S, Skobe M (2014) Role of lymphatic vasculature in regional and distant metastases. Microvasc Res 95:46–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Das S, Sarrou E, Podgrabinska S et al. (2013) Tumor cell entry into the lymph node is controlled by CCL1 chemokine expressed by lymph node lymphatic sinuses. J Exp Med 210(8):1509–1528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira ER, Kedrin D, Seano G et al. (2018) Lymph node metastases can invade local blood vessels, exit the node, and colonize distant organs in mice. Science 359 (6382):1403–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown M, Assen FP, Leithner A et al. (2018) Lymph node blood vessels provide exit routes for metastatic tumor cell dissemination in mice. Science 359(6382):1408–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kedrin D, Gligorijevic B, Wyckoff J et al(2008) Intravital imaging of metastatic behavior through a mammary imaging window. Nat Methods 5(12):1019–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulit J, Kedrin D, Gligorijevic B et al. (2012) The use of fluorescent proteins for intravital imaging of cancer cell invasion. In: Hoffman R (ed) In vivo cellular imaging using fluorescent proteins. Methods mol biol. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinney SA, Murphy CS, Hazelwood KL et al. (2009) A bright and photostable photoconvertible fluorescent protein. Nat Methods 6 (2):131–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chudakov DM, Matz MV, Lukyanov S et al. (2010) Fluorescent proteins and their applications in imaging living cells and tissues. Physiol Rev 90(3):1103–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurskaya NG, Verkhusha VV, Shcheglov AS et al. (2006) Engineering of a monomeric green-to-red photoactivatable fluorescent protein induced by blue light. Nat Biotechnol 24 (4):461–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meijer EFJ, Jeong HS, Pereira ER et al. (2017) Murine chronic lymph node window for longitudinal intravital lymph node imaging. Nat Protoc 12(8):1513–1520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown EB, Campbell RB, Tsuzuki Y et al. (2001) In vivo measurement of gene expression, angiogenesis and physiological function in tumors using multiphoton laser scanning microscopy. Nat Med 7(7):864–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]