Abstract

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) of orthodontic patients is a diagnostic tool used increasingly in hospital and primary care settings. It offers a high-diagnostic yield, short scanning times, and a lower radiation dose than conventional computed tomography. This article reports on four incidental findings—that appear unrelated to the scan's original purpose—arising in patients for whom CBCT was carried out for orthodontic purposes. It underlines the need for complete reporting of the data set.

Keywords: Orthodontics, Cone beam computed tomography, Enamel pearl, Mandibular condyle, Cervical atlas

INTRODUCTION

Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) scanners dedicated for oral and maxillofacial use were pioneered in the late 1990s independently by Arai et al.1 in Japan and Moshiri et al.2 in Italy. CBCT offers advantages over conventional or medical computed tomography in that it can produce excellent submillimeter resolution,3 and the radiation dose is markedly lower.4,5 With most CBCT units the patient sits upright rather than supine so a more accurate representation of the soft tissues is obtained.6 The machines often resemble panoramic units; this provides a more familiar environment for orthodontic patients, which may be important, particularly when scanning children. The literature has already reported on a number of CBCT applications in orthodontics. A recent systematic review7 reported that 16% of their included articles dealt with CBCT imaging in orthodontics, and they covered the use of miniscrews in assessing palatal bone thickness,8,9 safe zones for placement in the maxillary and mandibular arches,10 fabrication of surgical guides for their placement,11cephalometrics,12–14 tooth position15 and inclination,16,17 assessment for rapid maxillary expansion,18 determining skeletal age based on cervical vertebrae morphology,19 and three-dimensional evaluation of upper-airway anatomy in adolescents.20 Other orthodontic uses include planning surgical exposure of impacted canines21 and orthognathic surgery in patients with facial asymmetry,22 temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders,23 and obtaining additional diagnostic information to assist in treatment planning.24

Reports of incidental findings on CBCT are sparse.6,25 In this article, four cases are presented of patients who underwent CBCT of the maxilla to aid orthodontic diagnosis. In all cases the scan was carried out on a Classic i-Cat (Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA) using the same scan parameters (5 cm height, 40 second scan time, 0.2 voxel size). Subsequent radiological reporting revealed a foreign body and rare anomalies of the enamel, condyle, and cervical vertebrae. The implications for each finding are discussed and the importance of formal interpretation of CBCT is highlighted in line with recent guidelines from the European Academy of Dentomaxillofacial Radiology26 and the Health Protection Agency (HPA).27

CASE ONE

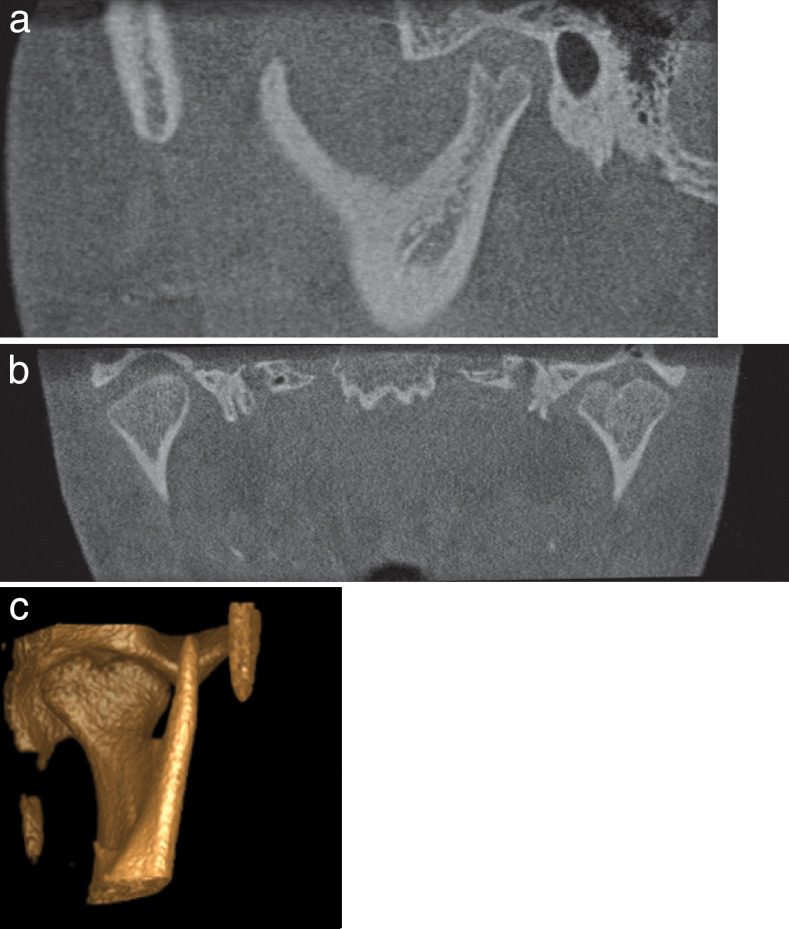

A CBCT scan of a 13-year-old girl had been requested with regard to the position of an unerupted UL1 and a possible transposition of the UL3 with the UL2. The patient had previously undergone an open exposure with gold chain to the central incisor, which had subsequently failed. The scan showed the UL1 to be unerupted, ectopic, and dilacerated, and there was a true transposition of the UL3 and UL2 (Figure 1). Incidental note was made of a cleft in the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas (Figures 2 and 3). This patient had no presenting signs or symptoms of neck pain, and as a result, no further follow-up of the atlas cleft was arranged.

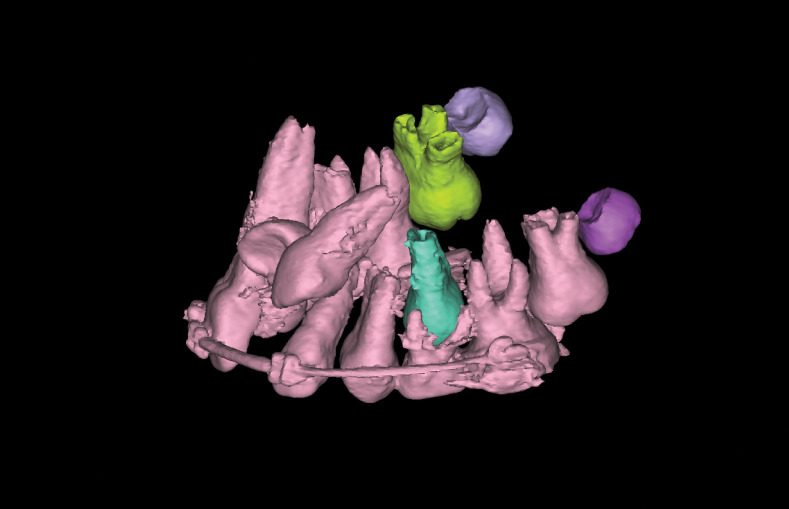

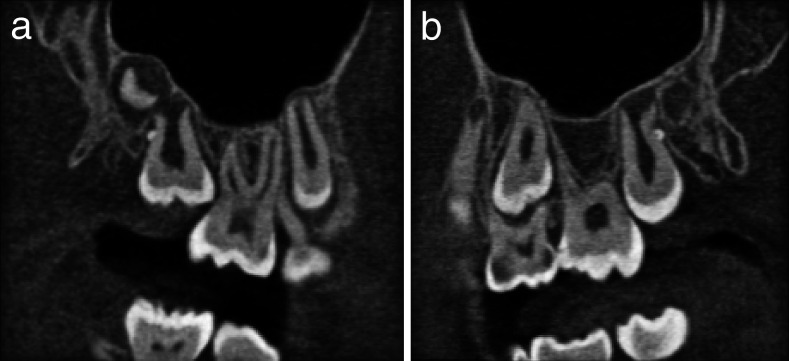

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional reconstruction showing ectopic and unerupted UL1 and transposition of UL3 and UL2. (©Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium)

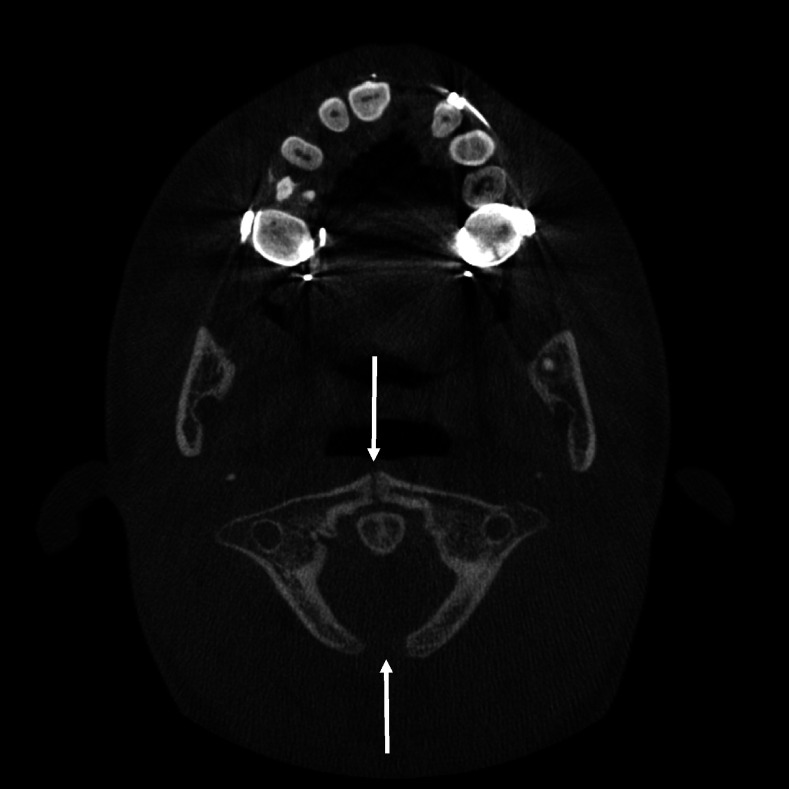

Figure 2.

Axial slice showing the clefts in the anterior and posterior arches of the atlas (see arrows). (Used with permission from Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA).

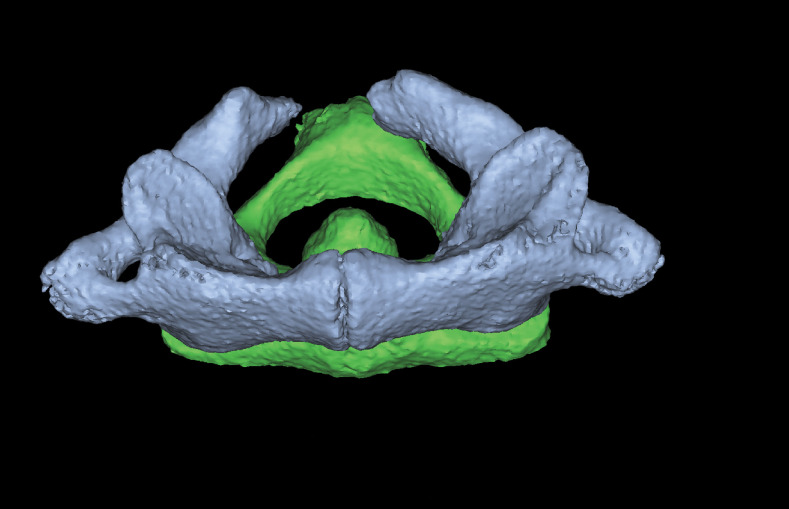

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the atlas (viewed from the anterior aspect). (©Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium)

CASE TWO

A 12-year-old girl was referred for a CBCT scan to assess the root integrity of both maxillary lateral incisors associated with unerupted buccally impacted canines (Figure 4). The scan showed no pathological resorption of the lateral incisors, but incidental note was made of enamel pearls on the distal aspects of both unerupted second permanent molars (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the maxilla showing the buccally impacted canines. (©Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium)

Figure 5.

Corrected sagittal slices through the right (a) and left (b) maxillary alveolus showing the enamel pearl on the distal aspect on the upper second molars. (Used with permission from Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA)

CASE THREE

A 16-year-old girl was referred regarding a transposition of an ectopic UL3 and UL4. The patient presented with Class II division 2 malocclusion on a Class II skeletal base with the UL3 unfavorably positioned for orthodontic alignment both vertically and horizontally. Provisional plans were made to extract the canine under general anesthetic and expose the unerupted premolar. A CBCT was requested to confirm the position of the canine to aid surgical planning so that it could be removed as atraumatically as possible. The scan demonstrated the exact position of the ectopic teeth and confirmed that there was no pathological resorption of any adjacent roots (Figure 6). In addition, a bifid left mandibular condyle was identified (Figure 7). The patient had no presenting signs or symptoms of temporomandibular dysfunction, and as a result, no further follow-up was required.

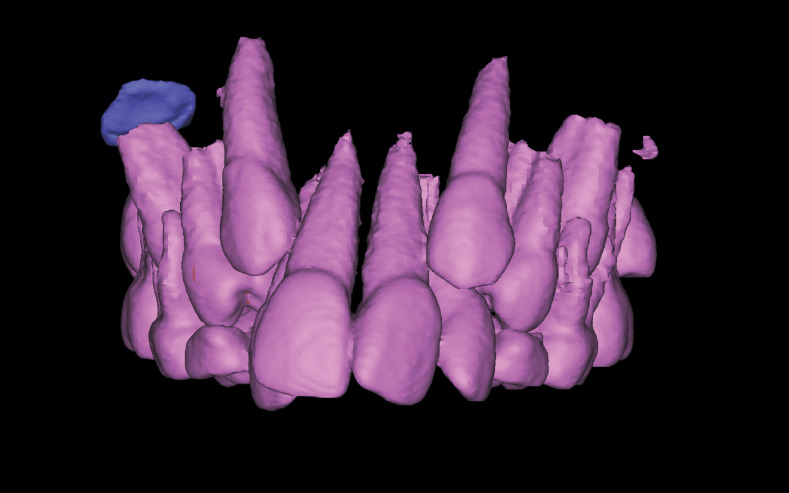

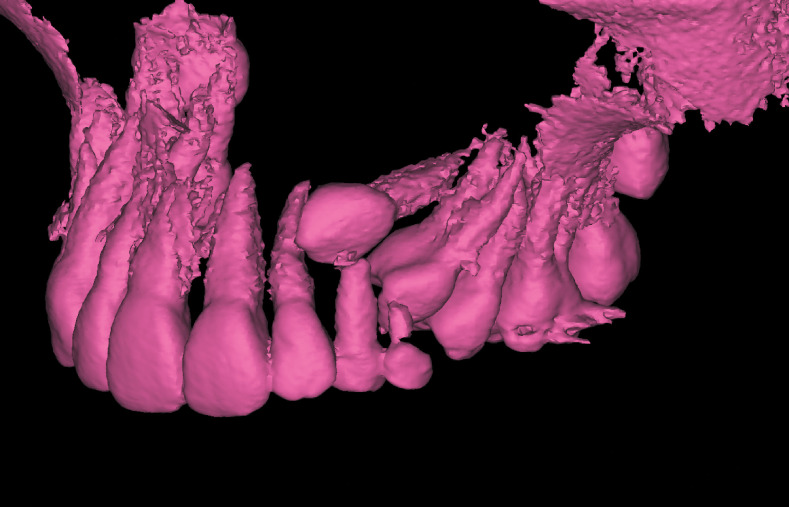

Figure 6.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of the maxillary teeth showing the position of the ectopic UL3. (©Materialise Dental, Leuven, Belgium)

Figure 7.

Corrected lateral (a), coronal (b), and three-dimensional reconstruction viewed from the anterior medial position (c) of the bifid left condyle. (Used with permission from Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA)

CASE FOUR

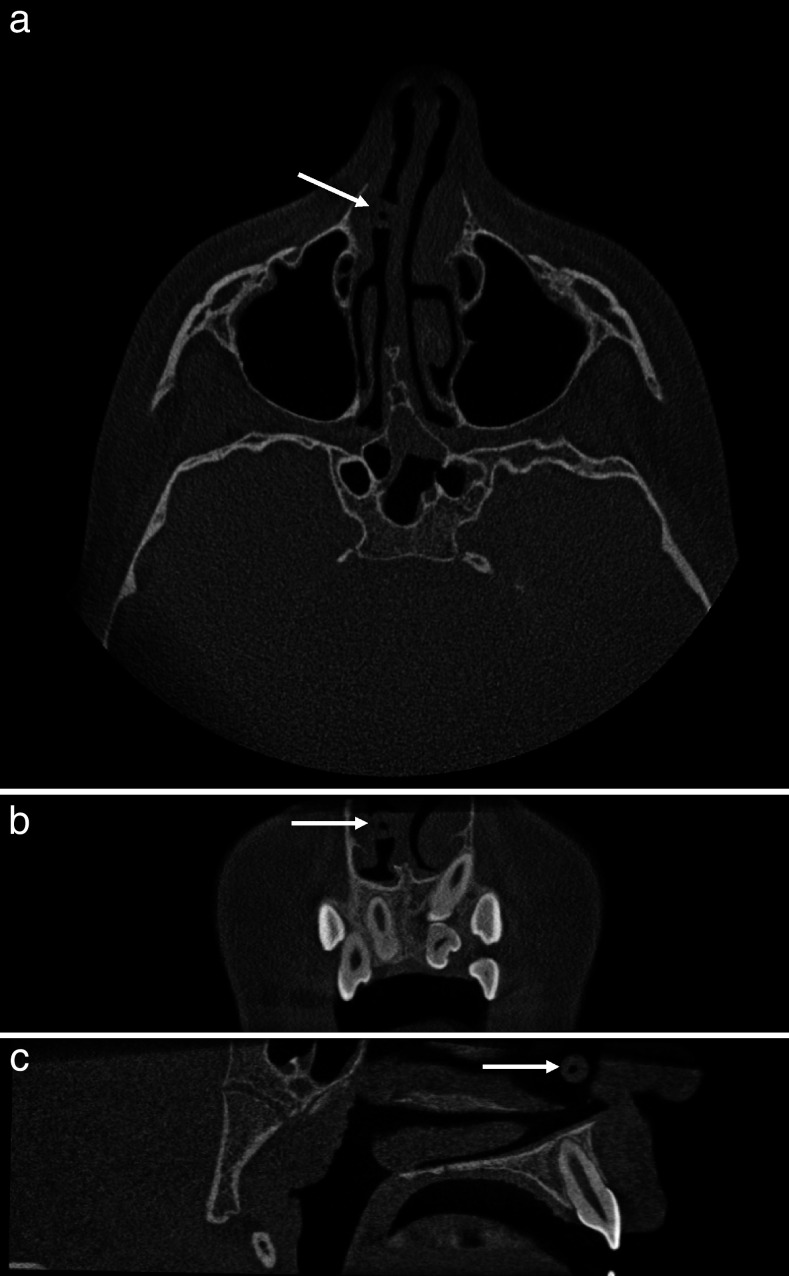

An 11-year-old boy was referred for a CBCT to facilitate treatment planning in the management of an unerupted UL1, a supplemental UL1, and associated midline supernumerary. The scan confirmed the presence of a midline supernumerary lying horizontal and palatal to the upper anterior teeth. The UL1 was impacted into the UR1 but had normal crown and root morphology. Palatal to the unerupted UL1, the supplemental incisor showed abnormal crown morphology and marked ridging on all tooth surfaces.

In addition to the dental findings a round spherical low-density, 6-mm diameter foreign body was seen on the right side anteriorly between the nasal septum and inferior concha. This was likely to represent a low-density foreign body (Figure 8). The patient was subsequently referred to the Ear, Nose, and Throat Department for further investigation, and a brightly colored plastic pellet was retrieved from the nose. The pellet originated from a toy gun set.

Figure 8.

Axial (a), coronal (b), and sagittal (c) images showing the pellet lodged between the right inferior concha and the nasal septum (see arrows). (Used with permission from Imaging Sciences International, Hatfield, PA).

DISCUSSION

Case one demonstrated an incidental finding of an atlas cleft. The first cervical vertebrae (C1) or atlas can be divided into three parts—the anterior arch, the lateral masses, and the posterior arch. It is formed from three primary centers of ossification initially in each lateral mass. At birth the bony portions are separated from one another by a narrow cartilaginous cleft and the anterior arch consists of cartilage; a separate ossification center appears at the end of the first year after birth. This joins the lateral masses, and ossification is usually complete by the age of 10 years.28

Clefts occur when there have been defects in the ossification centers of the vertebrae. Anterior arch clefts are rarer (0.1% of the population) than posterior arch clefts, which have been found in approximately 4% of adults.6 Such anomalies can occur more frequently in persons with cleft lip, cleft palate, or both.29 They may be discovered as incidental findings or may have a various pattern of presentation ranging from transient neck pain to different degrees of cord compression, including myelopathy.30,31 No particular type of arch defect seems more prone to cause symptoms than others.30 One important aspect in diagnosing atlas clefts is that they can simulate fractures. However, fractures show irregular edges with associated soft tissue swelling and a possible history of trauma,31,32 whereas congenital clefts are smooth and have an intact cortical wall,33 as reported in this case.

Case two reported an incidental finding of enamel pearls. Ectopic development of enamel on the root surface has been previously been referred to as enameloma, enamel drop, enamel nodule, or as in this case, enamel pearl.34 Their incidence has previously been reported as between 0.2% of maxillary molars and 0.03% of mandibular molars.35 The most common site is adjacent to the furcation of the root,36 and maxillary second and third molars are more commonly involved than the first molars.37 The pathogenesis of this anomaly is unknown. Several theories have been proposed; one such theory is that the inner cells of Hertwig's epithelial root sheath fail to detach from the newly laid dentin matrix.38 The possibility of a genetic association has also been postulated from reports of multiple enamel pearls on bilateral teeth in siblings.39 Enamel pearls can also be incidentally recognized during routine radiography and appear as hemispherical dense opacities projecting from the boundaries of the root surface.37 The significance of enamel pearls is that they have a weaker attachment to the periodontal ligament rendering these areas more prone to periodontal breakdown and pocket formation.36

Case three was a rare incidental finding of a bifid condyle, which is characterized by duplicity of the head of the condyle. The etiology is not clearly understood, but several theories have been proposed, including a developmental abnormality where a retained fibrous septum or vascular structure impedes ossification of the mandible,40 trauma,41 or minor trauma to the condylar growth center that may result in bifurcation or may lead to insufficient remodeling of the condylar bony fragment giving rise to the bifid formation.42 Although it is predominately an asymptomatic condition, it may also present with TMJ pain, sounds, and restricted mandibular movement. The diagnosis is usually made on the radiological manifestations, and treatment for symptomatic patients is similar to that of TMJ dysfunction—anti-inflammatory analgesics, muscle relaxants, physiotherapy, and splints. Surgery may be considered if the condition is associated with limited mouth opening or ankylosis.42

Case four showed a pellet lodged between the inferior concha and the nasal septum. In this case the pellet required removal, although it did not alter the patient's orthodontic treatment plan.

The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations 200043 do not explicitly state whose responsibility it is to report radiographs; it is usually regarded as the role of the operator. “Consensus Guidelines of the European Academy of Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology”26 suggest that for dentoalveolar CBCT images clinical evaluation should be made by a specially trained dental and maxillofacial (DMF) radiologist or, when this is impractical, an “adequately trained” general dental practitioner. By “adequately trained” the guidelines advise both theoretical and practical training. For nondental and craniofacial images either a DMF radiologist or a medical radiologist should report the scans. The HPA27 suggest that if a dentist has a CBCT unit with a large field of view then the images should be evaluated by a dentist with suitable training or a maxillofacial radiologist. In three of the cases presented here the incidental findings were located outside the teeth and supporting structures, so it would not be appropriate for a dentist without further training to report. Although in this case series none of the incidental findings affected any further proposed treatment and no further diagnostic tests were required, this has not always been the case.44

CONCLUSIONS

This case series of incidental findings reported from maxillary CBCT scans of orthodontic patients highlights the need for the complete scan to be interpreted by a radiologist or an appropriately trained clinician in line with recent guidelines from the European Academy of Dentomaxillofacial Radiology and the HPA.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor J Knox, Professor RJ Oliver, Mrs A Brown and finally PT Nicholson for allowing us the use of their patient images in this case series.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arai Y, Tammisalo E, Iwai K, Hashimoto K, Shinoda K. Development of a compact computed tomographic apparatus for dental use. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 1999;28:245–248. doi: 10.1038/sj/dmfr/4600448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mozzo P, Procacci C, Tacconi A, Martini P. T, Andreis I. A. A new volumetric CT machine for dental imaging based on the cone-beam technique: preliminary results. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1558–1564. doi: 10.1007/s003300050586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scarfe W. C, Farmna A. G, Sukovic P. Clinical applications of cone beam tomography in dental practice. J Can Dent Assoc. 2006;72:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schulze D, Heiland M, Thurman H, Adam G. Radiation exposure during mid-facial imaging using 4- and 16-slice computed tomography, cone beam computed tomography systems and conventional radiography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:83–86. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/28403350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludlow J. B, Ivanovic M. Comparative dosimetry of dental CBCT devices and 64-slice CT for oral and maxillofacial radiology. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Popat H, Drage N, Durning P. Mid-line clefts of the cervical vertebrae—an incidental finding arising from cone beam computed tomography of the dental patient. Br Dent J. 2008;204:303–306. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2008.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vos W, Casselman J, Swennen G. R. J. Cone-beam computerized tomography (CBCT) imaging of the oral and maxillofacial region: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:609–625. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gracco A, Lombardo L, Cozzini M, et al. Quantitative evaluation with CBCT of palatal bone thickness in growing patients. Prog Orthod. 2006;7:164–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.King K. S, Lam E. W, Faulkner M. G, et al. Predictive factors of vertical bone depth in the paramedian palate of adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:745–751. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0745:PFOVBD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poggio P. M, Incorvati C, Velo S, et al. Safe zones: a guide for miniscrew positioning in the maxillary and mandibular arch. Angle Orthod. 2006;76:410–416. doi: 10.1043/0003-3219(2006)076[0191:SZAGFM]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim S. H, Choi Y. S, Hwang E. H, et al. Surgical positioning of orthodontic mini-implants with guides fabricated on models replicated with cone beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:S82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farman A. G, Scarfe W. C. Development of imaging selection criteria and procedures should precede cephalometric assessment with cone beam computed tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Largravere M. O, Hansen L, Harzer W, et al. Plane orientation for standardization in 3 dimensional cephalometric analysis with computerized tomography imaging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;129:601–604. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lagravere M. O, Major P. W. Proposed reference point for 3 dimensional cephalometric analyses with cone beam computerized tomography. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;128:657–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mussig E, Wortche R, Lux C. J. Indications for digital volume tomography in orthodontics. J Orofac Orthop. 2005;66:241–249. doi: 10.1007/s00056-005-0444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erickson M, Caruso J. M, Leggitt L. Newtom QR-DVT 9000 imaging used to confirm a clinical diagnosis of iatrogenic mandibular nerve paraesthesia. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2003;31:843–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peck J. L, Sameshima G. T, Miller A, et al. Mesiodistal root angulation using panoramic and cone beam CT. Angle Orthod. 2007;77:206–213. doi: 10.2319/0003-3219(2007)077[0206:MRAUPA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rungcharassaeng K, Caruso J. M, Khan J. Y, et al. Factors affecting buccal bone changes of maxillary posterior teeth after rapid maxillary expansion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:428, e421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi H, Scarfe W. C, Farman A. G. Three dimensional reconstruction of individual cervical vertebrae from cone beam computed tomography images. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;131:426–432. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aboudara C. A, Hatcher D, Nielsen I. L, Miller A. A three dimensional evaluation of the upper airway in adolescents. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2003;6(suppl 1):173–175. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0544.2003.253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmuth G. P, Freisfeld M, Koster O, Schuller H. The application of computerized tomography (CT) in cases of impacted maxillary canines. Eur J Orthod. 1992;14:296–301. doi: 10.1093/ejo/14.4.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khambay B, Nebel J. C, Bowman J, et al. A 3D stereophotogrammetric image superimposition onto 3D CT scan images: the future of orthognathic surgery. A pilot study. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 2002;17:331–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsiklakis K, Syriopoulos K, Stamatakis H. C. Radiographic examination of the temporomandibular joint using cone beam computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2004;33:196–201. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/27403192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merrett S, Drage N, Durning P. Cone beam computed tomography: a useful tool in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. J Orthod. 2009;9:202–210. doi: 10.1179/14653120723193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cha J. Y, Mah J, Sinclair P. Incidental findings in the maxillofacial area with 3 dimensional cone beam imaging. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2005.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horner K, Islam M, Flygare L, Tsiklakis K, Whaites E. Basic principles for use of dental cone beam computed tomography: Consensus Guidelines of the European Academy of Dental and Maxillofacial Radiology. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2009;38:187–195. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/74941012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holroyd J. R, Gulson A. D. The radiation protection implications of the use of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) in dentistry—what you need to know. Available at: http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1246433630996 September 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Von Torklus D, Gehle W. The Upper Cervical Spine. New York, NY: Grune and Stratton; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugar D. A, Semb G. The prevalence of anomalies in the upper cervical vertebrae in subjects with cleft lip, cleft palate or both. Cleft Palate Craniofac. 2001;38:498–503. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0498_tpoaot_2.0.co_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currarino G, Rollins N, Diehl J. T. Congenital clefts of the posterior arch of the atlas: a report of cases including an affected mother and son. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:249–254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phan N, Marras C, Midha R, Rowed D. Cervical myelopathy caused by hypoplasia of the atlas: two case reports and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:629–633. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199809000-00140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dorne H, Lander P. H. CT recognition of anomalies of the posterior arch of the atlas vertebrae: differentiation from fracture. Am J Neurol. 1986;7:176–177. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosalkar H. S, Gerardi J. A, Shaw B. A. Combined asymptomatic congenital anterior and posterior deficiency of the atlas. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:810–813. doi: 10.1007/s002470100542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Risnes S. The prevalence, location and size of enamel pearls on human molars. Scand J Dent Res. 1974;82:403–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1974.tb00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner J. A note on enamel nodules. Br Dent J. 1945;78:39. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldstein A. Enamel pearls as a contributing factor in periodontal breakdown. J Am Dent Assoc. 1979;99:210–211. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1979.0258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langlais R, Langland O, Norje C. Diagnostic Imaging of the Jaws. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Willkins; 1995. Development and acquired abnormalities of the teeth and jaws; pp. 124–126. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kalnins V. Origin of enamel drops and cementicles in the teeth of rodents. J Dent Res. 1952;31:582–590. doi: 10.1177/00220345520310040801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saini T, Ogunleye A, Levering N, et al. Multiple enamel pearls in two siblings detected by volumetric computed tomography. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2008;37:240–244. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/86859829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shriki J, Lev R, Wong B, et al. Bifid mandibular condyle: CT and MR imaging appearance in two patients: case report and review of the literature. AJNR J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:1865–1868. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antoniades K, Karakasis D, Elephteriades J. Bifid mandibular condyle resulting from a saggital fracture of the condylar head. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1993;31:24–26. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(93)90176-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antoniades K, Hadjipetrou L, Antoniades V, Paraskevopoulus K. Bilateral bifid mandibular condyle. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endo. 2004;97:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations Vol SI 2000. London, UK: The Stationary Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nair M. K, Pettigrew J. C, Mancuso A. A. Intracranial aneurysm as an incidental finding. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2007;36:107–112. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/16588494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]