Abstract

Solid core nanoparticles coated with sulfonated ligands that mimic heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG) can exhibit virucidal activity against many viruses that utilize HSPG interactions with host cells for the initial stages of the infection. How the interactions of these nanoparticles with large capsid segments of HSPG-interacting viruses lead to their virucidal activity has been unclear. Here, we describe the interactions between sulfonated nanoparticles and segments of the human papilloma virus type 16 (HPV16) capsids using atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. The simulations demonstrate that nanoparticles primarily bind at interfaces of two HPV16 capsid proteins. After equilibration, distances and angles between capsid proteins in the capsid segments are larger for the systems in which the nanoparticles bind at interfaces of capsid proteins. Over time, the nanoparticle binding can lead to breaking of contacts between two neighboring proteins. The revealed mechanism of nanoparticles targeting the interfaces between pairs of capsid proteins can be utilized for designing new generations of virucidal materials and contribute to the development of new broad-spectrum non-toxic virucidal materials.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Among many infectious disease threats that humans face from microbes, viral infections are arguably the biggest pandemic threat at present. Even in the absence of pandemics, viral infections kill millions of people every year, as viruses have high rates of replication, mutation and transmissibility1. Available antiviral drugs often target specific viruses or, in some cases, members of a viral family2. Current antiviral drugs include small molecules, such as nucleoside analogues and peptidomimetics, monoclonal antibodies, proteins that are able to stimulate the immune response, such as interferon, and oligonucleotides2. Many of these drugs act intracellularly with selectivity for viral enzymes. However, since viruses mostly depend for their replication on infected host cells, the specificity of antiviral drugs for viral proteins is not ideal, often causing general intrinsic toxicity upon administration3,4. Furthermore, due to high mutation rates, most viruses develop drug resistance5–7.

When antiviral drug development is based on single virus-specific protein as a target, the discovered therapeutics lack the broad-spectrum effects and thus the capability of targeting many viruses that are phylogenetically unrelated and structurally different. Yet, there is a demand for development of broad-spectrum antiviral therapeutics that are non-toxic to hosts. One development approach is to identify substances that can favorably interact with many viruses outside of host cells and determine if these interactions can prevent the first stages of infection and the viral replication cycle. Previous efforts, based on the principle of targeting virus-cell interactions that are common to many viruses, identified many non-toxic substances that interact with a broad spectrum of viruses, such as heparin and polyanions8–12. However, most of these substances exhibit only virustatic properties where their activity depends on a reversible binding event. Binding reversibility makes these substances therapeutically ineffective: upon dilution, these materials detach from intact viral particles allowing the viruses to infect again.

Virucidal materials show large promise for use against viral infections. Virucidal molecules cause irreversible viral deactivation, which is not adversely affected by dilution13. Virucidal materials can include detergents, strong acids, polymers, and nanoparticles14–18. However, most of these materials have intrinsic cellular toxicity, since materials that can chemically damage the virus often also affect the host in which the virus replicates.

Recent studies demonstrated that non-toxic broad-spectrum virucidal materials can be developed based on the principle of mimicking the virus-host interactions common to many viruses19,20. In particular, virucidal material design can be inspired by viral attachment ligands / host cell receptors called heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), which are responsible for the initial steps of the virus replication cycle21. Many viruses, including human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16), human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), herpex simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2), attach to HSPGs, which are expressed on the surfaces of almost all eukaryotic cell types22. Nanoparticles (NPs) coated with long and flexible sulfonated ligands mimicking HSPG were shown to effectively associate with such viruses and eventually lead to irreversible viral deformation. These non-toxic nanoparticles (NPs) show in vitro irreversible virucidal activity against HSV-2, HPV-16, RSV, Dengue and lentivirus, and are also active ex vivo in human cervicovaginal histocultures infected by HSV-2 and in vivo in mice infected with RSV19.

Previous transmission electron microscopy analyses suggested the mechanism of the virucidal activity of NPs coated with sulfonated ligands against the HPV16 virus: NPs eventually break the capsid or the virus particle19. Few materials with reported virucidal effects have been examined with computational methods19,20,23–25, to explore their mechanisms of virucidal activity with atomistic resolution. In the present study, we use large scale atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to explore this suggested mechanism on systems containing 2.4 nm gold core nanoparticles coated with HSPG-mimicking ligands and extended capsid segments of two, three and four HPV16 major late pentamer proteins (L1). Our studies expand on previous modeling of sulfonated nanoparticles interacting with single HPV16 capsid proteins19. The present simulations explore the preferred sites of interaction between sulfonated NPs and capsid segments, as well as the perturbations induced in the capsid segments by the presence of NPs.

2. Methods

Constructing HPV16 Capsid Segments.

The cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the Human Papillomavirus Type 16 (HPV16) L1 capsid proteins, assembled into a capsid structure, shown in Figure 1a, was obtained from the RCSB protein databank (PDB: 3J6R)26. Segments of either two, three or four L1 proteins with the least empty space between them were selected and then extracted from the capsid. As L1 protein structures in the extracted segments were defined via the coordinates of the backbone atoms only, each L1 protein structure in three extracted segments was replaced by a crystal structure of HPV16 L1 protein (PDB: 5W1O)27. In all three segments, each L1 pentamer structure was docked into the cryo-EM structure-based protein density using colores tool in Situs software using a resolution of 5 Å28. Structures of resulting three HPV16 capsid segments were then further flexibly fitted into cryo-EM-extracted densities of L1 proteins using the molecular dynamics flexible fitting (MDFF) method in NAMD 2.1329–31. MDFF simulations, using the CHARMM36 force field32, were carried out for 50,000 steps with timestep of 1 fs in the constant volume and temperature conditions at 310 K in vacuum, with the scaling factor for potential, gscale (ξ), set to the value of 0.3 and with Langevin constant γLang set to 5.0 ps–1. Secondary structure, cispeptide bonds, and chirality restraints were applied on L1 pentamers to prevent the unnatural distortions during the fitting procedure.

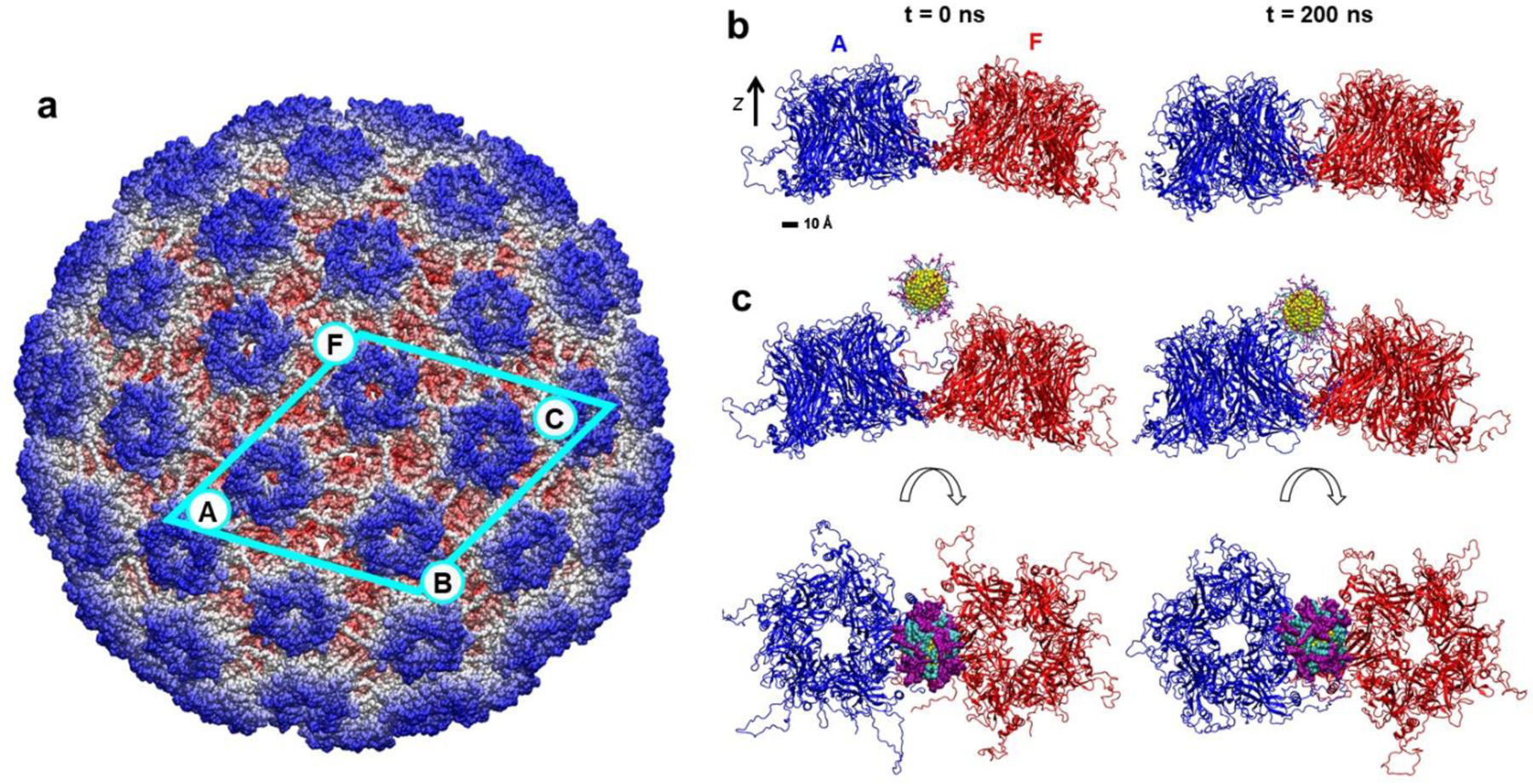

Figure 1. HPV16 virus capsid and its segments formed by L1 pentamer proteins.

a) Cryo-EM structure of the HPV16 capsid, assembled from L1 pentamer proteins (from Ref.26). Labeled pentamers contribute to capsid segments examined in MD simulations. The largest segment examined, formed by four L1 pentamers, is marked by the cyan frame. The atoms are colored according to their radial distance from the capsid center. Pentamer labels (A, F, B, C) correspond to labels used in figures and analyses described below. b) Conformations of the capsid segment containing two L1 pentamers at the initial time and after 200 ns of MD simulations. The pentamers are colored in blue (A) and red (F), and the aqueous solution is not shown for clarity. c) Conformations of the same segment in the presence of the MUS:OT gold nanoparticle at the initial time (left) and after 200 ns of MD simulations (right), presented in the side and top views. Gold atoms, MUS ligands and OT ligands are shown in yellow, purple, and teal, respectively.

Individual chains of L1 protein crystal structures fitted into capsid segments, based on PDB: 5W1O, were missing residues 404 to 431 and several residues at C- and N-termini. The structures of these missing residues (backbone atoms) were provided in pdbID: 3J6R, where they assumed flexible coil secondary structures. Since these missing residues form important contacts with the neighboring pentamers within capsid segments (Figure S1c), they were reconstructed in our models fully based on the structures reported in pdbID: 3J6R and covalently attached to the initial models L1 proteins (after MDFF fitting). Disulfide bonds were built between C161 and C324 residues for all the chains in L1 proteins. Final completed capsid segments were solvated with TIP3P water and neutralized with 0.15 M NaCl with solvate and ionize VMD plugins33, respectively.

Ligand Docking on HPV Pentamer.

Small sulfonated ligands (CH3CH2SO3−) were docked onto a single L1 protein and a pair of L1 proteins using the Autodock Vina software34,35. Docking was performed using the finalized structures of one and two L1 proteins described above. Sulfonated ligand structures were built using AMPAC graphical user interface. In Autodock Vina, the grid box was centered at various positions on a grid, scanning the protein surfaces with five fixed z-coordinates and changing the x and y coordinates from −40 Å to 40 Å for both, with an interval of 1 nm. Docking procedure was automated using our in-house Linux shell script. Each grid box dimension was 1 × 1 × 1 nm3 with a default spacing and exhaustiveness of 0.0375 nm and 8, respectively. The above procedure determined the locations of the ligands with the lowest docking scores on the L1 protein surfaces (Figure S1). These locations guided the placement of the nanoparticles with sulfonated ligands above the capsid segments.

Nanoparticle Model.

Atomistic model of a spherical nanoparticle was prepared by cutting a face centered cubic lattice of gold (Au) atoms (Au-Au bond length 2.88 Å) into a sphere with diameter of ~2.4 nm. The gold core was ligated with a random spherical array of 40 1-octanethiol (OT) and 40 11-mercapto-1-undecanesulfonate (MUS) ligands. All ligands were built with AMPAC, and then arranged into a random spherical array with 0.3949 per Au atom surface density using our own code. The built NP was then solvated in TIP3P water and ionized with sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions at a 0.15 M NaCl concentration using the VMD solvate and ionize plugins33. After solvation and ionization, short MD simulations were performed to obtain a structure of the equilibrated NP as an input for the NP-capsid segment simulations. NPs, described with the generalized CHARMM force field36, were minimized for 2,000 steps using NAMD2.13 software29 and equilibrated for 20 ns in the NPT ensemble with Langevin dynamics (Langevin constant γLang = 1.0 ps–1), where temperature and pressure remained constant at 310 K and 1 bar, respectively. The particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method was used to calculate the Coulomb interaction energies, with periodic boundary conditions applied in all directions. Evaluation of van der Waals and Coulombic interactions was performed every 1- and 2-timesteps, respectively. A timestep of 2 fs was used for equilibration of NPs.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations.

Atomistic simulations were conducted to investigate interactions of HPV16 capsid segments alone and in the presence of a 2.4 nm-core MUS:OT NP. All the systems were described with CHARMM36 force field parameters32,36. MD simulations were performed with the NAMD2.13 package29. All the simulations were conducted with Langevin dynamics (Langevin constant γLang = 1.0 ps–1) in the NPT ensemble, where temperature and pressure remained constant at 310 K and 1 bar, respectively. The particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method was used to calculate the Coulomb interaction energies, with periodic boundary conditions applied in all directions. The evaluation of van der Waals and Coulombic interactions was performed every 1- and 2-timesteps, respectively.

In total, six systems were prepared for final MD simulation runs. They consisted of two, three and four HPV16 L1 pentamers with and without the nanoparticle. Sizes and the number of atoms in all the simulated systems are listed in Table S1. Guided by docking calculations, which identified multiple sites on L1 pentamer surfaces where the bound sulfonated ligands have the most favorable docking scores (Figure S1), three systems with nanoparticles were prepared by placing a single nanoparticle 10 Å above the interfaces of two, three, or four pentamers that contained these sites identified in docking calculations. For all systems, 10,000 steps of minimization were performed, followed by 2 ns equilibration of solvent molecules around the pentamers, which were restrained by using harmonic forces with a spring constant of 1 kcal/(mol Å2). Next, the systems were equilibrated in MD production runs. To prevent the translation of the simulated capsid segments across the unit cell boundaries, the centers-of-mass (COMs) of these segments were restrained to remain at their initial values with a force constant of 2.0 kcal/mol∙Å2. COMs of capsid segments were calculated from the coordinates and masses of the α-carbon atoms of several selected buried residues (chosen to be residue 331) for all the chains of L1 pentamers. The applied single point COM restraint still allowed full rotation, capsid disassembly, and internal conformational changes of the simulated capsid segments. Yet, rigid body rotations of the capsid segments are of no interest to the present study, but could occur spontaneously by diffusion and would result in the unwanted capsid segment self-interactions across the unit cell boundaries in the rectangular prism unit cells (Table S1). Therefore, we applied an additional restraint on L1 pentamers, that would effectively prevent capsid segments to rotate as rigid bodies, but still allow L1 pentamers to move freely with respect to each other within the capsid segments. This additional restraint was applied using a collective variable distanceZ in NAMD, which allowed the z-coordinate of pentamer COMs (the coordinate along the z-axis labeled in Figure 1b) to fluctuate freely without any restraints within a 10 Å-wide window with respect to its initial value, but prevented that z-coordinate of pentamer COMs to fall outside the defined 10 Å-wide window. The distanceZ collective variable was implemented using the potential constant of 100 kcal/ mol∙Å2. The applied restraint had no effect on pentamers / capsid segments motion in the other two dimensions.

Data Analysis.

Distance between two pentamers.

To analyze distances between two L1 pentamers, we calculated distances between centers of mass (COM) of backbone atoms of individual pentamers over the duration of simulations using our scripts in VMD33.

Angle between two pentamers.

To analyze tilting of two pentamers with respect to each other, we calculated angles between vectors that align with axes of the cylindrically shaped void space in pentamer centers. Directions of these vectors were calculated by approximating shapes of pentamers as cylinders and evaluating the direction of the plane passing through COM of atoms of every alternating monomer (three in total) that forms each pentamer protein.

Residue Contacts.

To analyze interaction between neighboring pentamers and between NP and pentamers, we evaluated contacts between different protein residues and between protein residues and NP over the duration of simulations. A contact was defined to exist at a given time frame if any atom of the concerned protein residue was located within 5 Å of the other pentamer or the NP.

3. Results and Discussion

The present study examines the interactions between gold nanoparticles coated with sulfonated ligands and segments of HPV16 capsids of varying sizes. Previous modeling of these virucidal NPs interacting with a single L1 capsid protein of the HPV16 virus suggested that the initial steps of the virucidal mechanism involve NPs binding multivalently to L1 proteins via charged, polar and hydrophobic interactions19. However, the atomistic details behind the NP interactions with larger HPV16 capsid segments and the eventual distortion and breaking of the capsid, proposed to be at the core of the virucidal activity, remained unexamined and unclear. Here, we probe the effects of the NP binding on the stability of the HPV16 capsid segments. We first modeled several segments of HPV16 capsid and relaxed them in MD simulations. Then, these segments were also simulated in the presence of virucidal MUS:OT NPs. Two sets of simulations were then analyzed to determine the mechanism of virucidal activity by these nanoparticles.

MD Simulations of HPV16 Capsid Segments in the Presence and Absence of Nanoparticles.

A total of six systems, containing segments of two, three and four L1 proteins by themselves and in the presence of single MUS:OT nanoparticles, were modeled in aqueous solution and examined in atomistic MD simulations. The snapshots of these systems after between 200 ns (for two- and three-pentamer systems) and 115 ns (for four-pentamer systems) of equilibration are shown in Figures 1 and 2. During equilibration, the proteins comprising the capsid segments moved closer to each other in all the systems, and the flexible coils that make contacts between neighboring pentamers rearranged from their initial conformations. The change of the two-pentamer system from the initial to a more compact state is shown in Figure 1b. This observed change in the pentamer positions and interfacial flexible coils may indicate a need for more careful modeling of the capsid segment interfaces. However, the present study relied on modeling the interfaces based on the structural information reported in Ref26. In systems where NPs were present, pentamers also moved closer to each other, while the NPs diffused over the initial 7–9 ns from the aqueous solution towards surfaces of the capsid segments, where they remained bound for the rest of the simulations (Supplementary Movie).

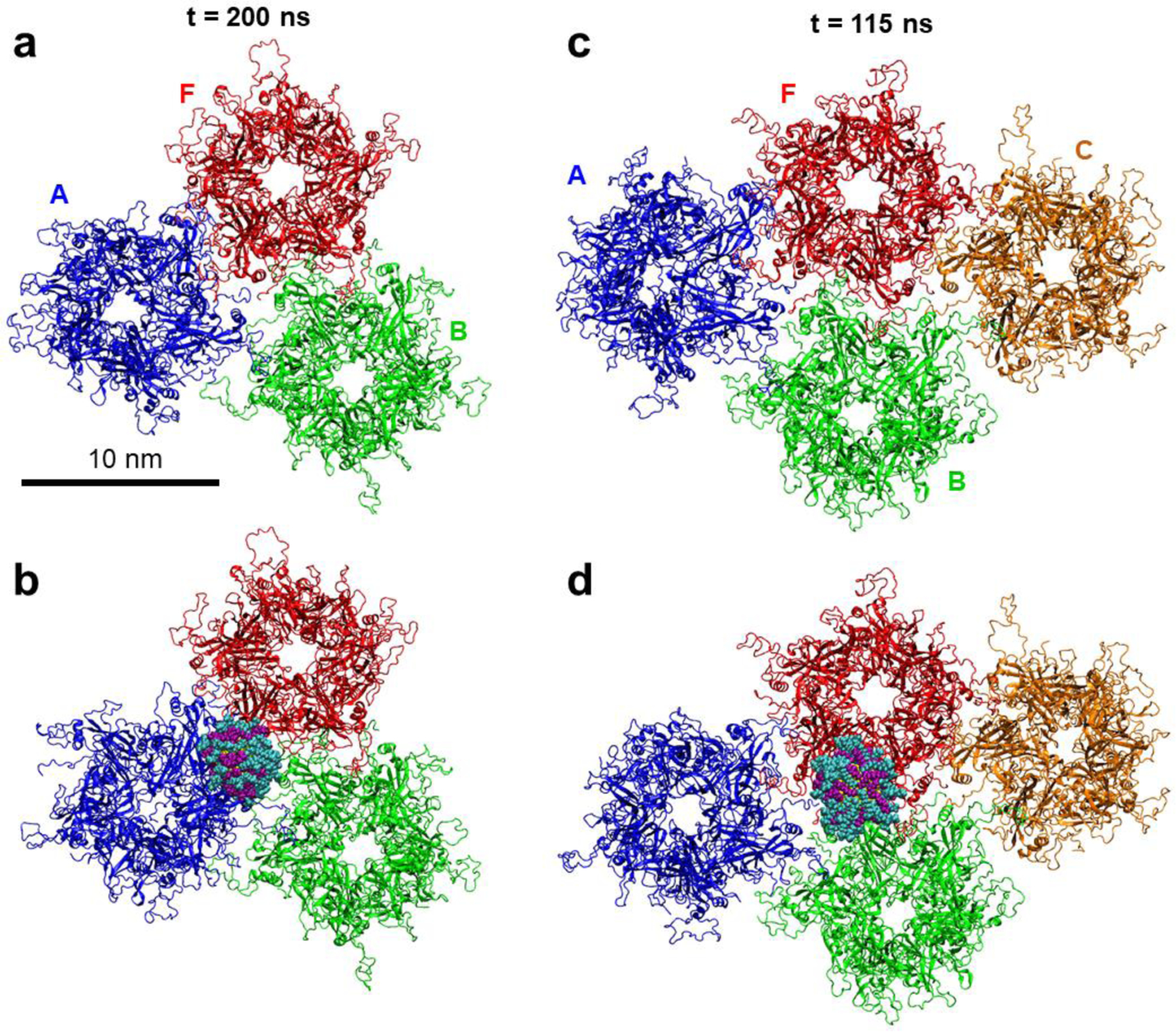

Figure 2. Simulated systems of larger HPV16 capsid segments alone and interacting with sulfonated ligand-coated gold core nanoparticle.

a) Conformations of the capsid segment containing three L1 pentamers after 200 ns of MD simulations. b) Conformations of the three pentamer segment in the presence of the MUS:OT NP after 200 ns of MD simulations. c) Conformations of the capsid segment containing four L1 pentamers after 115 ns of MD simulations. b) Conformations of the four pentamer segment in the presence of the MUS:OT NP after 115 ns of MD simulations. The pentamers are colored in blue (A), red (F), green (B), and orange (C), and the aqueous solution is not shown for clarity. The color scheme of the NP is the same as in Figure 1.

The primary binding mode between NP and capsid segments, as observed in the simulations, is shown in Figures 1c and 2b,d. In all the cases, the 2.4 nm gold core NP interacts with the capsid segment at the interface of two L1 pentamers, and over time, it is observed to wedge in between two pentamers that it binds. The NP binds to the interface of two pentamers even in three- and four-pentamer capsid segments, in which there are interfaces of three pentamers within the segments (Figure 2). Over the course of the three- and four-pentamer systems simulations, the NPs shifts from three pentamer junctions to two pentamer junctions, and eventually bind to A-F pentamer junction in three-pentamer system (after ~30 ns) and B-F pentamer junction in four-pentamer system (after ~70 ns), as shown in Figure 2b,d. The binding mode of NP to the capsid segment is likely determined by the NP size: larger NPs may have different binding modes, potentially including the junctions of three pentamers.

In all the examined systems, internal stabilities of individual L1 proteins were tracked by calculating root mean square deviation (RMSD) of parts with defined secondary structures from the systems simulated without and with the NPs. As Figures S2 and S3 show, there are no significant differences in RMSDs of analogous L1 proteins in the systems simulated without and with the NPs. Therefore, the internal stabilities of L1 proteins are not compromised in the presence of NPs.

Effects of Nanoparticle Binding on the Positions of Proteins within Capsid Segments.

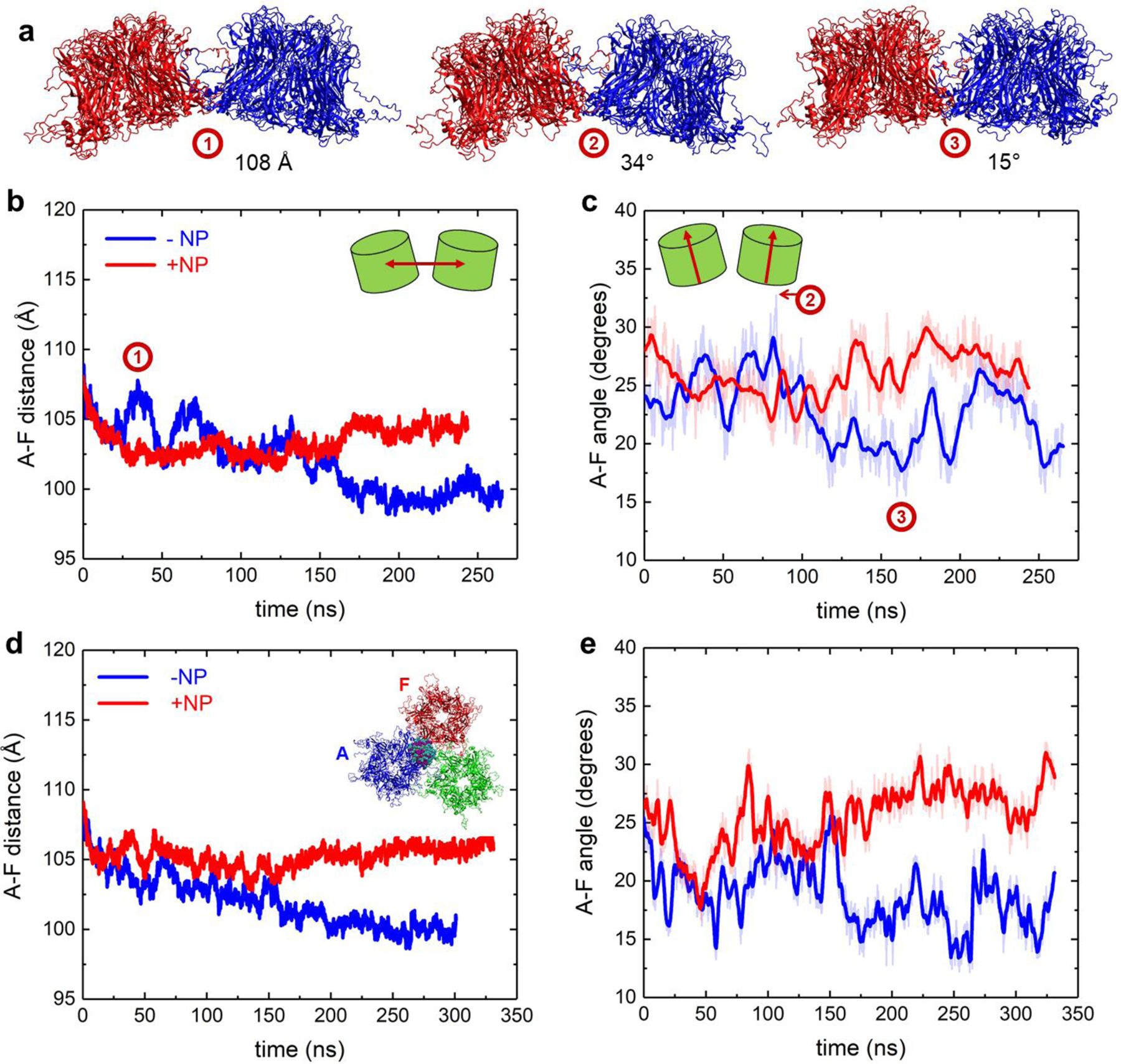

MD trajectories of all the systems, both without and with NPs, clearly show that L1 proteins move with respect to each other. To measure the changes in the positions of proteins within capsid segments, we tracked distances between centers of mass (COM) of the adjacent pentamer pairs and angles between the central axes of the adjacent pentamer pairs. The resulting distances and angles between adjacent proteins in two- and three-pentamer systems are shown in Figure 3, and their values averaged over the last 100 ns of trajectories are reported in Table S2. In two-pentamer systems, distances between A and F pentamers decrease over time from their initial values, both for the lone capsid segment and the capsid segment binding to the NP (Figure 3b), in agreement with the visual observations that capsid proteins move closer to each other over time. However, these distances fluctuate and decrease by different amounts in the absence and presence of NPs. Namely, the pentamers equilibrate at COM distances of ~99.6 Å and ~ 104 Å in the absence and presence of NP, respectively. When averaged over the last 100 ns, NP binding to two-pentamer segment leads to a COM distance between the adjacent pentamers that is greater by ~ 4.5 Å than the COM distance in the system without NP. Similar trends are observed when measuring the distances between only the chains of A and F pentamers that are in direct contact, A1, A5 and F1, F2 (Figure S15). The pentamers in two-pentamer systems also equilibrate at angles of ~22° and ~27° in the absence and presence of NP, respectively (Figure 3c). Overall, these pentamers have an angle that is ~ 5° larger when averaged over the last 100 ns in the presence of the NP than in its absence. The observations indicate that NP acts as a wedge between the pentamers.

Figure 3. Distances and angles between pentamers in HPV capsid segments alone and when interacting with MUS:OT NP.

a) Representative snapshots of two-pentamer capsid segments with pentamers assuming different distances and angles with respect to each other. The snapshot times are labeled in the distance and angle plots in panels (b-c) below. b) Distance between A and F pentamers alone and when interacting with NP for two-pentamer segment systems. c) Angle between A and F pentamers alone and when interacting with NP for two-pentamer segment systems. d) Distance between A and F pentamers alone and when interacting with NP for three-pentamer segment systems. e) Angle between A and F pentamers alone and when interacting with NP for three-pentamer segment systems.

The effects of the NP on protein positions are similar in two- and three-pentamer systems. The distances and the angles between A and F pentamers, averaged over the last 100 ns, are greater by ~ 6 Å and ~ 10°, respectively, in the system with the NP than in the system without the NP. In three-pentamer systems, distances between pentamers whose interfaces do not participate in NP binding are similar in systems with and without the NP (Figure S4). For the four-pentamer system, the NP has no clear effects on the segment perturbation, as shown in Figures S5–S6. These negligible effects are likely due to a combination of short simulation timescales and a larger network of interactions between the pentamers within the extended capsid that may increase the times over which the segment changes occur.

Effects of Nanoparticle Binding on the Pentamer Interface and the Integrity of Capsid Segments.

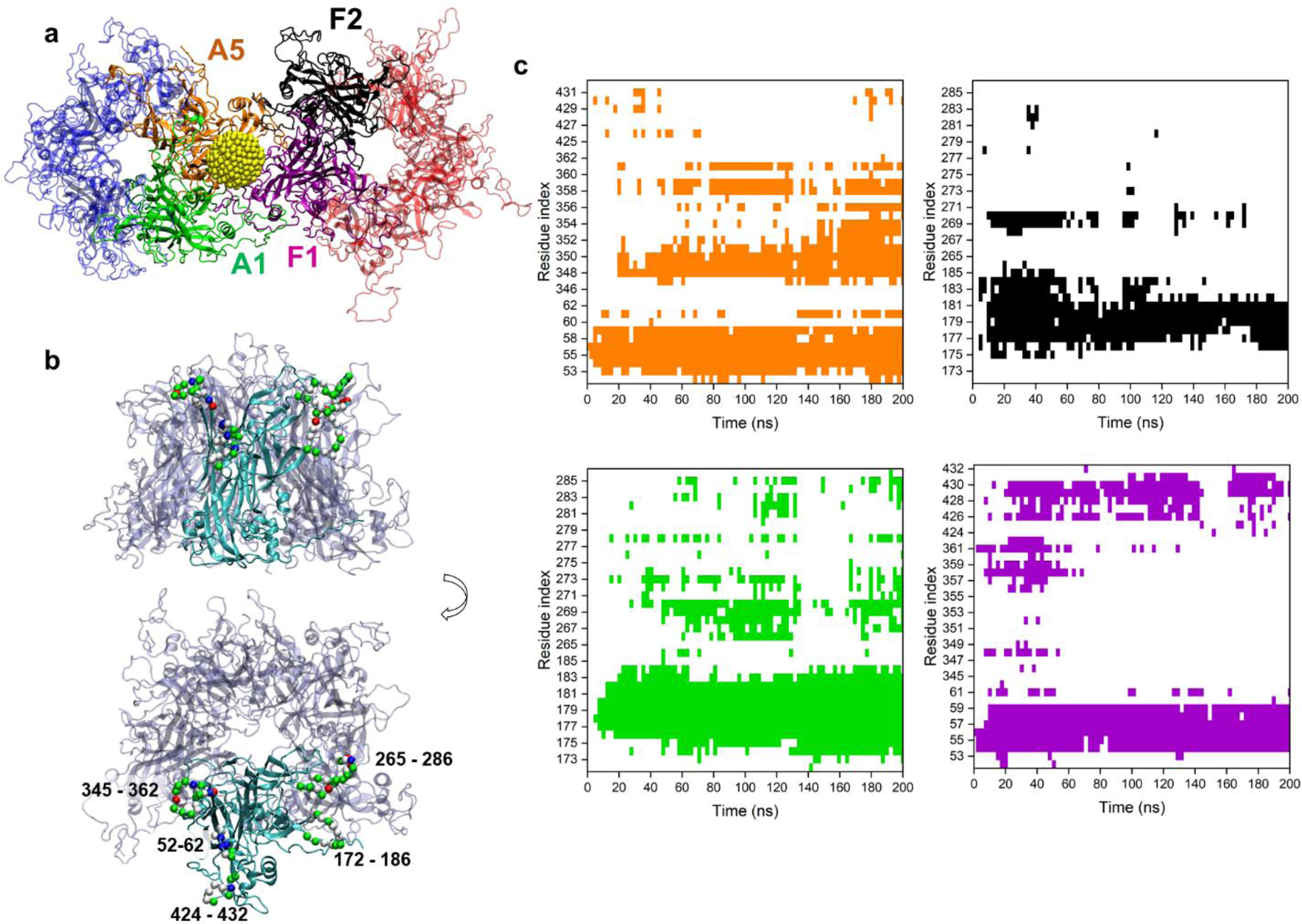

When the NP binds at the interface of two pentamers, it interacts with two out of five chains on each pentamer. These chains on A and F pentamers, labeled as A1, A5, F1 and F2, are highlighted in Figure 4a. Similar interactions are observed for NPs within three- and four-pentamer systems. The individual chains preserve their secondary structures while interacting with NPs (Figures S7–S9), as it is mostly the flexible loop regions of the chains, protruding from the capsid surface into the solvent, that interact with NPs (Figures 4b, S10). These loop regions and specifically some of the lysine residues on them (K278, K356, K361, K54 and K59) were found to be implicated in the recognition of heparan sulfate proteoglycans27,37, indicating that NPs coated with MUS and OT ligands can mimic HSPG cell receptors allowing for effective viral association.

Figure 4. Interactions of MUS:OT NP at the interface of two L1 pentamers in the two-pentamer system.

a) A snapshot of the NP interacting at the interface of two pentamers, shown in faded blue and red. The NP interacts with two distinct chains of both A and F pentamers, labeled as A1 (green), A5 (orange), F1 (purple) and F2 (black). The NP gold core is shown in yellow, and MUS and OT ligands are not shown for clarity. b) Side and top views of two chains of the pentamer typically found to interact with the NP, highlighted in red. The residues consistently found to interact with NP are shown by their Cα atoms (green, white, blue and red spheres label their residue types, namely polar, non-polar, basic and acidic) and labeled with residue indices. c) Contact maps of residues of the four chains of two-pentamer systems found to interact with NP over the course of the simulation. Colors in the contact maps match the colors of the four chains labeled within pentamers in panel a (A5 – orange, F2 – black, A1 – green, and F1 – purple). White regions in contact maps denote no contact.

As each chain is equivalent in sequence, similar in structure, but different in orientation, MUS:OT NP interacts with two unique surfaces of A1, A5, F1 and F2 chains. Figures 4b and S10 highlight the residues of these chains that interact significantly with the NP: chains F1 and A5 interact with NP via three loop regions (residues 52–62, 345–362 and 424–432), whereas chains A1 and F2 interact with NP via two loop regions (residues 172–186 and 265–286). Contacts between these loop regions and the NP are largely maintained over the simulation time, as shown in the contact maps in Figure 4c. These loop regions contain many charged and non-polar amino acids (Figure S10). For example, the loop region with residues 52–62 interacts strongly with the NP via K53, K54, and K59, as well as the polar 56–58 residues. Interactions of NP with this loop region (residues 52–62) is significant in all three examined systems indicating the importance of this region for establishing the initial NP-capsid binding through long range electrostatic interactions and preserving it later via local electrostatic and H-bond interactions. All the loops, and especially the loop with residues 172–186, also interact with the NP via its hydrophobic residues. The interactions of NP with capsid segments via charge-charge and hydrophobic interactions correlates with observations of a previous MD study of a single L1 pentamer with MUS:OT NP19. The charge-charge interactions occur between negative sulfonate groups on MUS:OT-NP and the positive HSPG-binding lysine residues of loop regions, while the hydrophobic interactions occur between non-polar alkyl chains of NP ligands and nonpolar groups on L1 protein surface. Similar pentamer-NP contacts are observed in the three-pentamer system as in the two-pentamer system (Figure S11). However, significantly fewer pentamer-NP contacts are observed in the four-pentamer system (Figure S12), indicating a need for longer simulation times in this system to capture the effects of the NP presence on the capsid segment integrity.

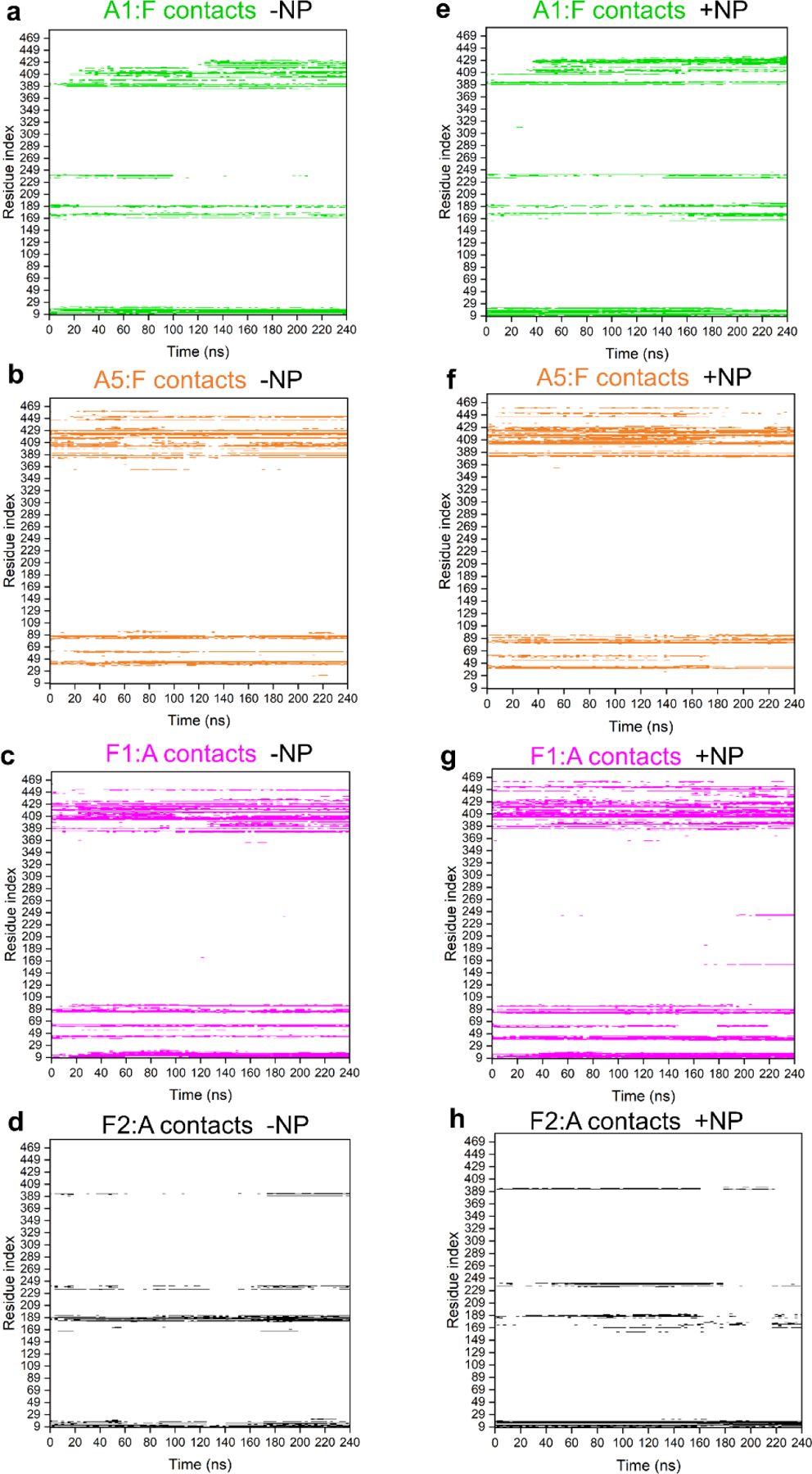

We next examine in Figure 5 how the contacts between neighboring pentamers evolve over time in the absence and presence of the NP within two-pentamer systems. Most of the time, the same inter-pentamer contacts are observed in the absence and presence of the NP. However, towards the end of the 240 ns trajectories, some contacts between pentamers become less frequent or are lost in the presence of the NP, such as the contacts that A5 segment makes with the F pentamer (residues 52 – 62 and amino acids surrounding the residue 449) and the contacts that F2 segment makes with the A pentamer (residues 169 – 189). Similar loss of interactions between pentamers interacting with the NP is observed in three-pentamer and four-pentamer systems (although less pronounced, as shown Figures S13 and S14). All these contact maps indicate that NPs are able to disrupt some interactions between neighboring pentamers over the simulation timescales.

Figure 5. Contact maps of L1 pentamer interactions in two-pentamer segments alone and when interacting with MUS:OT NP.

a-d) Contact maps of A1 and A5 chain residues in contact with F pentamer and F1 and F2 chain residues in contact with A pentamer within two-pentamer systems over the course of the simulation. e-h) Contact maps of A1 and A5 chain residues in contact with F pentamer and F1 and F2 chain residues in contact with A pentamer within two-pentamer systems in the presence of MUS:OT NP over the course of the simulation. The colors in the contact maps match the colors of the four chains within pentamers shown in Figure 4a. White regions in the contact maps denote no contact.

Overall, our studies also show that most of the residues involved in pentamer-NP and pentamer-pentamer interactions are mutually exclusive over the course of 115 – 240 ns simulations. With longer simulation times, more significant effects of NP presence are expected on pentamer-pentamer interactions.

4. Conclusion

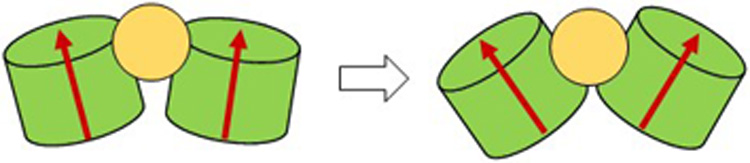

In this work, we described the interactions between virucidal MUS:OT nanoparticles with 2.4 nm gold cores and segments of HPV16 capsids using atomistic MD simulations. It was previously shown that HSPG-mimicking ligands of these NPs form multivalent interactions with L1 capsid proteins19. Here, we determine the initial effects of the MUS:OT NP presence on HPV 16 capsid segments and depict it in the scheme of Figure 6. The first step of this activity is the binding of MUS:OT NPs at interfaces of two L1 proteins forming the capsid segments. The insertion of the NP at the interface of two L1 proteins leads to distances and angles between these neighboring proteins being greater than when the NP is not present. As the time progresses, the NP presence can lead to loss of some contacts between two neighboring proteins, although our simulations captured the very initial stages of this stage of the virucidal activity. Our findings suggest that the disruption of the HPV 16 capsid by MUS:OT NPs may be starting at interfaces of two L1 capsid proteins. However, we note a possibility that our findings for two-, three-, and four-pentamer capsid segments are not necessarily translatable to the disruption of larger capsid lattice segments or the intact capsid. Further investigations of larger lattices and intact capsids are needed to reveal further insights into pathways of the NP approach and the full capsid breaking process. However, the revealed mechanism of the NP disruptions at interfaces can be experimentally tested and utilized for designing new generations of materials that can perturb and disintegrate viral capsids38 or control the integrity of other naturally occurring or engineered protein assemblies39,40.

Figure 6. A scheme of MUS:OT NP effect on HPV16 capsid segments.

MUS:OT NPs (2.4 nm gold cores) bind to interfaces of two L1 proteins and wedge in between them. The NPs eventually lead to loss of contacts between L1 proteins at this interface.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R03AI142553. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors gratefully acknowledge computer time provided by the Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Table of system sizes, results of the docking calculations and structural details of pentamer-pentamer interfaces, plots of pentamer RMSDs over simulation times for all the simulated systems, distances between centers of mass of pentamer pairs for all the simulated systems, angles between pentamer pairs in simulations of four-pentamer systems, plots of RMSDs of selected single chains within protein pentamers over time in simulations for all the systems, highlights of structures of pentamer chains that participate in pentamer-pentamer interfacial contacts, maps of contacts between nanoparticle and pentamer amino acid residues over time in three- and four-pentamer systems, maps of contacts between neighboring pentamer proteins over time in three- and four-pentamer systems, distances between centers of mass of selected chains within pentamer pairs for two and three-pentamer systems, a table of average distances and angles between neighboring pentamers in two- and three-pentamer systems. (PDF)

Nanoparticle interactions with the pentamer interface in simulations of a two-pentamer system (Movie)

References

- 1.Adalja A & Inglesby T, “Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agents: A Crucial Pandemic Tool,” Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther 17, 467–470 (2019). DOI: 10.1080/14787210.2019.1635009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Clercq E & Li G, “Approved Antiviral Drugs over the Past 50 Years,” Clin. Microbiol. Rev 29, 695–747 (2016). DOI: 10.1128/CMR.00102-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Clercq E & Herdewijn P, in Pharm. Sci. Encycl 1–56 (American Cancer Society, 2010). DOI: 10.1002/9780470571224.pse026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gröschel B, Cinatl JC & Cinatl J Jr., “Viral and Cellular Factors for Resistance against Antiretroviral Agents,” Intervirology 40, 400–407 (1997). DOI: 10.1159/000150572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Menéndez-Arias L, “Molecular Basis of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Drug Resistance: An Update,” Antiviral Res 85, 210–231 (2010). DOI: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siedner MJ, Moorhouse MA, Simmons B, de Oliveira T, Lessells R, Giandhari J, Kemp SA, Chimukangara B, Akpomiemie G, Serenata CM, et al. “Reduced Efficacy of HIV-1 Integrase Inhibitors in Patients with Drug Resistance Mutations in Reverse Transcriptase,” Nat. Commun 11, 5922 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-19801-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Addetia A, Hannon WW, Choudhary MC, Dingens AS, Li JZ & Bloom JD, “Prospective Mapping of Viral Mutations that Escape Antibodies Used to Treat COVID-19,” Science (80-. ) 371, 850–854 (2021). DOI: 10.1126/science.abf9302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rusnati M, Vicenzi E, Donalisio M, Oreste P, Landolfo S & Lembo D, “Sulfated K5 Escherichia coli Polysaccharide Derivatives: A Novel Class of Candidate Antiviral Microbicides,” Pharmacol. Ther 123, 310–322 (2009). DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riblett AM, Blomen VA, Jae LT, Altamura LA, Doms RW, Brummelkamp TR, Wojcechowskyj JA & Dermody TS, “A Haploid Genetic Screen Identifies Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans Supporting Rift Valley Fever Virus Infection,” J. Virol 90, 1414–1423 (2016). DOI: 10.1128/JVI.02055-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klimyte EM, Smith SE, Oreste P, Lembo D, Dutch RE & Dermody TS, “Inhibition of Human Metapneumovirus Binding to Heparan Sulfate Blocks Infection in Human Lung Cells and Airway Tissues,” J. Virol 90, 9237–9250 (2016). DOI: 10.1128/JVI.01362-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cagno V, Donalisio M, Bugatti A, Civra A, Cavalli R, Ranucci E, Ferruti P, Rusnati M & Lembo D, “The Agmatine-Containing Poly(Amidoamine) Polymer AGMA1 Binds Cell Surface Heparan Sulfates and Prevents Attachment of Mucosal Human Papillomaviruses,” Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 59, 5250–5259 (2015). DOI: 10.1128/AAC.00443-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donalisio M, Quaranta P, Chiuppesi F, Pistello M, Cagno V, Cavalli R, Volante M, Bugatti A, Rusnati M, Ranucci E, et al. “The AGMA1 Poly(amidoamine) Inhibits the Infectivity of Herpes Simplex Virus in Cell Lines, in Human Cervicovaginal Histocultures, and in Vaginally Infected Mice,” Biomaterials 85, 40–53 (2016). DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shogan B, Kruse L, Mulamba GB, Hu A & Coen DM, “Virucidal Activity of a GT-Rich Oligonucleotide against Herpes Simplex Virus Mediated by Glycoprotein B,” J. Virol 80, 4740–4747 (2006). DOI: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.4740-4747.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bastian AR, Kantharaju, McFadden K, Duffy C, Rajagopal S, Contarino MR, Papazoglou E & Chaiken I, “Cell-Free HIV-1 Virucidal Action by Modified Peptide Triazole Inhibitors of Env gp120,” ChemMedChem 6, 1335–1339 (2011). DOI: 10.1002/cmdc.201100177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara HH, Garza-Treviño EN, Ixtepan-Turrent L & Singh DK, “Silver Nanoparticles are Broad-Spectrum Bactericidal and Virucidal Compounds,” J. Nanobiotechnology 9, 30 (2011). DOI: 10.1186/1477-3155-9-30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broglie JJ, Alston B, Yang C, Ma L, Adcock AF, Chen W & Yang L, “Antiviral Activity of Gold/Copper Sulfide Core/Shell Nanoparticles against Human Norovirus Virus-Like Particles,” PLoS One 10, 1–14 (2015). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromberg L, Bromberg DJ, Hatton TA, Bandín I, Concheiro A & Alvarez-Lorenzo C, “Antiviral Properties of Polymeric Aziridine- and Biguanide-Modified Core–Shell Magnetic Nanoparticles,” Langmuir 28, 4548–4558 (2012). DOI: 10.1021/la205127x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Souza e Silva JM, Hanchuk TDM, Santos MI, Kobarg J, Bajgelman MC & Cardoso MB, “Viral Inhibition Mechanism Mediated by Surface-Modified Silica Nanoparticles,” ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 16564–16572 (2016). DOI: 10.1021/acsami.6b03342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cagno V, Andreozzi P, D’Alicarnasso M, Silva PJ, Mueller M, Galloux M, Goffic RL, Jones ST, Vallino M, Hodek J, et al. “Broad-Spectrum Non-Toxic Antiviral Nanoparticles with a Virucidal Inhibition Mechanism,” Nat. Mater 17, 195–203 (2018). DOI: 10.1038/NMAT5053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones ST, Cagno V, Janeček M, Ortiz D, Gasilova N, Piret J, Gasbarri M, Constant DA, Han Y, Vuković L, et al. “Modified Cyclodextrins as Broad-Spectrum Antivirals,” Sci. Adv 6, eaax9318 (2020). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax9318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spillmann D, “Heparan Sulfate: Anchor for Viral Intruders?,” Biochimie 83, 811–817 (2001). DOI: 10.1016/S0300-9084(01)01290-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu J & Thorp SC, “Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate and Its Roles in Assisting Viral Infections,” Med. Res. Rev 22, 1–25 (2002). DOI: 10.1002/med.1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zacheo A, Hodek J, Witt D, Mangiatordi GF, Ong QK, Kocabiyik O, Depalo N, Fanizza E, Laquintana V, Denora N, et al. “Multi-Sulfonated Ligands on Gold Nanoparticles as Virucidal Antiviral for Dengue Virus,” Sci. Rep 10, 9052 (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-020-65892-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gossert ST, Parajuli B, Chaiken I & Abrams CF, “Roles of Variable Linker Length in Dual Acting Virucidal Entry Inhibitors on HIV-1 Potency via on-the-Fly Free Energy Molecular Simulations,” Protein Sci 29, 2304–2310 (2020). DOI: 10.1002/pro.3949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gossert ST, Parajuli B, Chaiken I & Abrams CF, “Roles of Conserved Tryptophans in Trimerization of HIV-1 Membrane-Proximal External Regions: Implications for Virucidal Design via Alchemical Free-Energy Molecular Simulations,” Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma 86, 707–711 (2018). DOI: 10.1002/prot.25504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardone G, Moyer AL, Cheng N, Thompson CD, Dvoretzky I, Lowy DR, Schiller JT, Steven AC, Buck CB, Trus BL et al. “Maturation of the Human Papillomavirus 16 Capsid,” MBio 5, e01104–14 (2014). DOI: 10.1128/mBio.01104-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dasgupta J, Bienkowska-Haba M, Ortega ME, Patel HD, Bodevin S, Spillmann D, Bishop B, Sapp M & Chen XS, “Structural Basis of Oligosaccharide Receptor Recognition by Human Papillomavirus,” J. Biol. Chem 286, 2617–2624 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wriggers W, “Conventions and Workflows for Using Situs,” Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr 68, 344–351 (2012). DOI: 10.1107/S0907444911049791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phillips JC, Hardy DJ, Maia JDC, Stone JE, Ribeiro JV, Bernardi RC, Buch R, Fiorin G, Hénin J, Jiang W, et al. “Scalable Molecular Dynamics on CPU and GPU Architectures with NAMD,” J. Chem. Phys 153, 044130 (2020). DOI: 10.1063/5.0014475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Mitra K, Frank J & Schulten K, “Flexible Fitting of Atomic Structures into Electron Microscopy Maps using Molecular Dynamics.,” Structure 16, 673–683 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trabuco LG, Villa E, Schreiner E, Harrison CB & Schulten K, “Molecular Dynamics Flexible Fitting: A Practical Guide to Combine Cryo-Electron Microscopy and X-ray Crystallography.,” Methods 49, 174–180 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang J & Mackerell AD, “CHARMM36 All-Atom Additive Protein Force Field: Validation Based on Comparison to NMR Data,” J. Comput. Chem 34, 2135–2145 (2013). DOI: 10.1002/jcc.23354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphrey W, Dalke A & Schulten K, “VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics,” J. Mol. Graph 14, 33–38 (1996). DOI: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trott O & Olson AJ, “AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading,” J. Comput. Chem 31, 455–461 (2009). DOI: 10.1002/jcc.21334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trott O & Olson AJ, “Software News and Update AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading,” J Comput Chem 31, 455–461 (2010). DOI: 10.1002/jcc.21334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vanommeslaeghe K, Hatcher E, Acharya C, Kundu S, Zhong S, Shim J, Darian E, Guvench O, Lopes P, Vorobyov I et al. “CHARMM General Force Field: A Force Field for Drug-Like Molecules Compatible with the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Biological Force Fields,” J. Comput. Chem (2010). DOI: 10.1002/jcc.21367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knappe M, Bodevin S, Selinka H-C, Spillmann D, Streeck RE, Chen XS, Lindahl U & Sapp M, “Surface-exposed Amino Acid Residues of HPV16 L1 Protein Mediating Interaction with Cell Surface Heparan Sulfate*,” J. Biol. Chem 282, 27913–27922 (2007). DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M705127200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perilla JR, Hadden JA, Goh BC, Mayne CG & Schulten K, “All-Atom Molecular Dynamics of Virus Capsids as Drug Targets,” J. Phys. Chem. Lett 7, 1836–1844 (2016). DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li Y, Kennedy NW, Li S, Mills CE, Tullman-Ercek D & Olvera de la Cruz M, “Computational and Experimental Approaches to Controlling Bacterial Microcompartment Assembly,” ACS Cent. Sci 7, 658–670 (2021). DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sen S, Vuković L & Král P, “Computational Screening of Nanoparticles Coupling to Aβ40 Peptides and Fibrils,” Sci. Rep 9, 17804 (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-019-52594-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.