Abstract

Nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations about the impact of COVID-19 on children and families have shifted. Initial advice for parents stressed topics such as how to talk about the pandemic with children or cope with illness-related distress. They now focus on youth adjustment to a heavily disrupted school year and on strategies for building long-term resilience. Although these conversations often center on youth adjustment, they have—at last—started to consider the well-being of parents (and other caregivers) as well. This shift in focus is crucial given the enormous challenges that parents face right now and the direct links between their well-being and that of their children. What continues to lag, even well into the pandemic, however, is the provision of workable solutions for addressing parents’ mental health. While we applaud the renewed focus on parenting stress and well-being, we remain deeply concerned by the absence of a plan for intervening.

Nearly a year into the COVID-19 pandemic, conversations about the impact of COVID-19 on children and families have shifted. Initial advice for parents stressed topics such as how to talk about the pandemic with children or cope with illness-related distress. They now focus on youth adjustment to a heavily disrupted school year and on strategies for building long-term resilience. Although these conversations often center on youth adjustment, they have—at last—started to consider the well-being of parents (and other caregivers) as well. This shift in focus is crucial given the enormous challenges that parents face right now and the direct links between their well-being and that of their children. What continues to lag, even well into the pandemic, however, is the provision of workable solutions for addressing parents’ mental health. While we applaud the renewed focus on parenting stress and well-being, we remain deeply concerned by the absence of a plan for intervening.

Early data suggest that in the wake of the pandemic, rates of psychiatric illness have surged, with nearly a quarter of adults meeting key criteria for major depressive disorder and nearly a third meeting criteria for generalized anxiety disorder.1 Data from both past quarantines and the current pandemic suggest that primary caregivers are at even greater risk than the general population.2 , 3 There are also new data on COVID-19 adjustment suggesting that parents find themselves less emotionally supported than they were before the onset of the pandemic.4 The risks posed by parental psychopathology are not trivial during the best of times: they shape numerous aspects of the home environment and elevate risk of youth psychopathology considerably, even when genetic factors are considered. During times of high stress and uncertainty, it is potentially worse. For example, during the influenza A virus subtype H1N1 outbreak, caregiver fear and experience of threat impacted child anxiety directly.5 For youths who need psychiatric treatment during the pandemic, there is evidence that parental psychopathology attenuates outcomes and that this is not adequately addressed by treatment of the child.6

Even among parents who do not have diagnosable mental health problems, the toll of these extraordinary circumstances should not be overlooked. Many parents are caring not only for their children but also for aging parents. Some are grieving the death of loved ones. Many are coping with job loss that has precipitated financial instability and caused food and housing insecurity. Juggling the demands of work, virtual schooling, and restless children amidst intense isolation and poor social support do not make for better parenting. They create stress, irritability, and guilt, which can lead to greater mental health problems, chaotic home environments, and the potential for harsh parenting. For parents of youths with special needs, these challenges are particularly pronounced. All of this comes amidst reduced contact with schools and social services agencies for families in need.

These challenges exist for all parents, but they are the tip of the iceberg for parents who are disproportionately affected by the pandemic. In Black and Latinx communities with markedly higher rates of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality, limited access to care, and systemic barriers to quality care that lead to disparate health outcomes, the pandemic is likely to bring far greater parenting stress. These challenges are amplified further by our national reckoning with generations of racism, a long overdue process that may bring additional stress and exhaustion for Black families as a spotlight is directed on deeply painful and personal issues.

If the stressors and their consequences are well known, what then do we do? The first step: seize every opportunity to evaluate and promote parent well-being, even when it falls outside of traditional models of care. Universal screening for youth mental health problems has gained traction over the past decade, and it has a demonstrated record of success for improving early identification and access to care among youths with common conditions such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and depression. Many practices now administer measures such as the Pediatric Symptom Checklist-17 as part of routine visits. Why not do the same for parents? Brief inventories exist to capture parenting stress and adjustment, and they not only provide information about parent mental health, but also provide critical context for understanding the ecosystem in which pediatric patients live. They are a valuable treatment-planning tool and can be used to guide discussions on how to promote well-being. When these measures prove burdensome or unfeasible, routinely asking parents “How are you holding up?” or expressing empathy about the strain of their multiple caregiving roles can create valuable openings to addressing parent mental health. Such questions can be posed in the context of adolescent and child psychiatry visits or during adult psychiatry visits where the focus may not typically be on parenting. These family-based approaches to screening and triage are not new. Strategies such as the Vermont Family Treatment Model have well-documented success7, but they bear further translation, particularly right now.

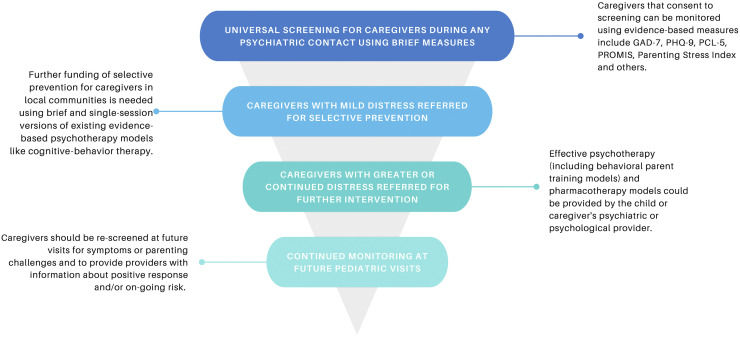

Amidst a pandemic that has already consumed the better part of a year and will be with us for some time, we already know enough about the impact on parents. The impact on children is not far behind. To offset the damage, we encourage a broader screening approach that captures parents and caregivers during any point of contact with psychiatric care providers, whether it be child- or parent-directed services, across settings (Figure 1 ). We recommend widely available, reliable, and valid tools for assessment of caregiver distress, parenting behavior, and symptoms. Many tools are free and easily administered electronically or during in-person visits. For parents who screen positive, brief and single-session interventions8 , 9 are available that target key mechanisms of change in anxiety and depression, many in telehealth and compelling digital formats that are low-burden and cost-effective options. They can be purchased by health systems or quickly deployed at individual or small group levels by psychiatric or psychological care providers and broader community service agencies to prevent further symptoms. These brief treatments can provide meaningful support, often using evidence-based treatment strategies found in lengthier psychotherapy protocols. For parents whose distress persists, psychological services nationwide, including Medicaid-funded services, are now available via telehealth and/or phone. Given changes to Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act privacy and billing coverage laws, these services may be accessed by providers outside an individual’s immediate local community. Finally, we strongly recommend that clinical practices develop resource lists that can be shared with parents as part of routine child visits and link them to bibliotherapy and other low-cost, low-burden intervention options for their own care. For parents who need more, referral lists for practitioners who provide evidence-based psychotherapy can be shared. A list of primary care and psychiatric providers who are comfortable with prescribing effective pharmacotherapy is also vital. Finally, ongoing screening of caregivers by pediatric and family or internal medicine providers throughout this pandemic may be needed to meet the mental health needs of caregivers. As with all universal screening efforts, there are bound to be implementation challenges. Time is limited, and virtual sessions complicate data collection. Nonetheless, advanced planning and even informal probes can pave the way for brief systematic assessment that is also done virtually. Extant data on pandemic mental health outcomes already tell us that this would be time well spent.

Figure 1.

Screening, Prevention, and Intervention for Caregivers of Youth During COVID-19

Note:GAD-7 = General Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; PCL-5 = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System.Please note color figures are available online.

Although the full mental health impact of these tumultuous times remains to be seen, it is clear that rates of anxiety and depression were rising well before these challenges arrived. Without quick and responsive deployment of effective screening, prevention, and evidence-based intervention, we risk leaving rising numbers of children and parents in increasingly stressful environments ripe to leave a pandemic legacy of toxic stress, mental illness, and, potentially, abuse and neglect. We can act now with proven prevention measures to ensure the best possible outcomes for children and families.

Footnotes

The authors have reported no funding for this work.

This work has been previously posted on a preprint server: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xzf2c.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Peris

Writing – original draft: Peris, Ehrenreich-May

Writing – review and editing: Peris, Ehrenreich-May

ORCID

Tara S. Peris, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3643-3994

Jill Ehrenreich-May, PhD: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7436-5393

Disclosure: Dr. Peris has received research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She has received royalties from Oxford University Press. Dr. Ehrenreich-May has received funding from the Children’s Trust. She has reported additional prior grant funding from the Ream Foundation, NIMH, and the Upswing Fund. She has received royalties from Oxford University Press.

All statements expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not reflect the opinions of the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. See the Guide for Authors for information about the preparation and submission of Commentaries.

References

- 1.U.S. Census Bureau. Data reported from May 7-12, 2020. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/demo/hhp/hhp2.html. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 2.Sprang G., Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7:105–110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei S., Jiang F., Su W., et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID-19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;21:100331. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Center for Translational Neuroscience RAPID-EC Project. 2020. https://medium.com/rapid-ec-project Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 5.Remmerswaal D., Muris P. Children’s fear reactions to the 2009 swine flu pandemic: The role of threat reinforcement as provided by parents. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;25:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maliken A.C., Katz L.F. Exploring the impact of parental psychopathology and emotion regulation on evidence-based parenting interventions: A transdiagnostic approach to improving treatment effectiveness. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013;16:173–186. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0132-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudziak J., Ivanova M.Y. The Vermont family based approach: Family based health promotion, illness prevention, and intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2016;25:167–178. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schleider J.L., Weisz J.R. Little treatments, promising effects? Meta-analysis of single-session interventions for youth psychiatric problems. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schleider J.L., Dobias M.L., Pati S. Promoting treatment access following pediatric primary care depression screening: Randomized trial of web-based, single-session interventions for parents and youths. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:770–773. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]