The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a plethora of acute and long-term diseases, with lung health remaining an important focus. Even though reports of fetal viral transmission of SARS-CoV-21 and viral placental infection2 have raised concerns, implications for longer-term lung health induced by a virus with high affinity to the respiratory epithelium3 have not been addressed. Our study was designed to elucidate the effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the fetus, especially in light of ongoing discussions about the benefits of vaccination during pregnancy. Additionally, we aimed to inform future studies on pulmonary health in children exposed to SARS-CoV-2 during pregnancy. We used fetal MRI to assess lung volume as a measure of pulmonary growth in the offspring of women with uncomplicated SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. This study was approved by the local institutional review board (ethical approval #LMU-207–33).

We analysed the MRI data of 34 pregnant women (median gestational age 33·5 weeks [range 24–40]; appendix p 3) with only mild symptoms of PCR-proven SARS-CoV-2 infection and no related hospital admissions. Fetal lung volume, normalised to estimated fetal weight, was described as a percentage of the respective 50th percentile reference values (appendix p 6).4 The effects of gestational age at MRI scan, sex, timepoint (trimester) of infection (confirmed by positive PCR), and duration of infection in days (PCR to MRI) on fetal lung volume were assessed by generalised linear modelling with identity link function for normal distribution. Placental heterogeneity and thrombosis were scored from 0 (none) to 4 (severe).

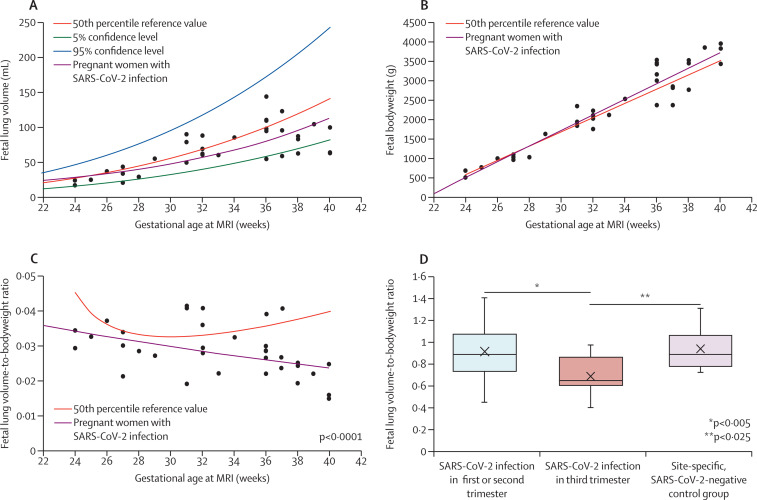

In pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, normalised fetal lung volume was significantly reduced compared with age-adjusted reference values,4 in the absence of structural abnormalities or organ infarction, and was unexplained by differences in somatic growth (84% vs 24% of 50th percentile reference; p<0·0001; figure ). The timepoint of infection showed significant effects on fetal lung growth, with reduced lung volumes observed with SARS-CoV-2 infections acquired during the third trimester (69% vs 91% of 50th percentile reference in the first or second trimester; p=0·0249; figure). Duration of infection (p=0·5657), gestational age at MRI scan (p=0·5704), and sex (p=0·3721) did not show significant effects. The reduction in normalised lung volume was supported by the masked comparison to a site-specific, SARS-CoV-2-negative control group (n=15, 95% vs 69% of 50th percentile reference with infection in third trimester; p=0·0050; appendix p 4), as well as a second reader study (appendix p 4). Compared with pregnant women who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2, pregnant women who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 showed increased placental heterogeneity (p=0·0475) and thrombotic changes (p=0·0230); however, the association between placental changes and normalised lung volume was not significant when taking gestational age at MRI scan into account (p=0·4508 and p=0·4004, respectively). Neonatal follow-up in 21 (62%) of 34 neonates at birth (gestational age 35–42 weeks) showed adequate birthweight for gestational age and no indication of acute postnatal respiratory distress (Apgar score 9–10; pulse oximetry 97–100%).

Figure.

Effects of SARS-CoV-2 on fetal lung volume and bodyweight

(A) 50th percentile values, 95% confidence level, and 5% confidence level of total fetal lung volume (mL) over gestational age (weeks at MRI), and the trend observed in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. (B) 50th percentile reference values of estimated fetal bodyweight (g) over gestational age (weeks at MRI) and the trend observed in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. (C) 50th percentile reference values of fetal lung volume-to-bodyweight ratio over gestational age (weeks at MRI) and the trend observed in pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. (D) Fetal lung volume normalised by fetal bodyweight (expressed as a percentage of 50th percentile reference value) with timepoint of infection in the third trimester vs timepoint of infection in the first or second trimester vs a site-specific, SARS-CoV-2-negative control group.

The effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy on fetal lung development have been largely understudied throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing reduced fetal lung volume in otherwise healthy pregnant women with SARS-CoV-2 infection. This reduction was dependent on the timepoint of infection, indicating that the most significant results occurred in the third trimester, thereby overlapping with the saccular stage of lung development dedicated to the expansion of (future) air spaces.5 Despite equivocal findings on placental transmission,6 predominant viral transmission in the third trimester,1 and the significant correlation between positive maternal PCR test and amniotic presence of SARS-CoV-2 near term7 might enhance exposure of the developing lung parenchyma to the virus, facilitated through increased fetal breathing in the third trimester. Specifically, the high affinity of the virus to alveolar epithelial cells3 could affect the so-called developmental sprint of these cells. The absence of postnatal respiratory distress in this cohort points to an important, subclinical phenotype related to prenatal exposure to SARS-CoV-2 that should be functionally and structurally addressed in follow-up studies under consideration of exposure to environmental hazards, including infections and toxins. Furthermore, recommendations of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination during pregnancy might be supported by our data.

This online publication has been corrected. The corrected version first appeared at thelancet.com/respiratory on April 28, 2022

SS, VK, JR, and AH contributed equally. TK holds stock of Roche and Biontech and has a relative who is employed at Roche. SM is in the advisory board of, and receives research support, honoraria, and travel expenses from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Clovis, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Medac, Merck, Novartis, Olympus, PharmaMar, Pfizer, Roche, Sensor Kinesis, Teva, and Tesaro. All other authors declare no competing interests. This work was supported by the programme Physician Scientists for Groundbreaking Projects at Helmholtz Zentrum München (Munich, Germany) and part of the research programme GRK 2338: Targets in Toxicology. The funders of the study had no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Kotlyar AM, Grechukhina O, Chen A, et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:35–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patane L, Morotti D, Giunta MR, et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA on the fetal side of the placenta in pregnancies with coronavirus disease 2019-positive mothers and neonates at birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridges JP, Vladar EK, Huang H, Mason RJ. Respiratory epithelial cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19. Thorax. 2022;77:203–209. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2021-217561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyers ML, Garcia JR, Blough KL, Zhang W, Cassady CI, Mehollin-Ray AR. Fetal lung volumes by MRI: normal weekly values from 18 through 38 weeks' gestation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:432–438. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367:427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00441-016-2545-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahyuddin AP, Kanneganti A, Wong JJL, et al. Mechanisms and evidence of vertical transmission of infections in pregnancy including SARS-CoV-2s. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40:1655–1670. doi: 10.1002/pd.5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda MFY, Brizot ML, Gibelli M, et al. Vertical transmission of SARS-CoV2 during pregnancy: a high-risk cohort. Prenat Diagn. 2021;41:998–1008. doi: 10.1002/pd.5980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.