Abstract

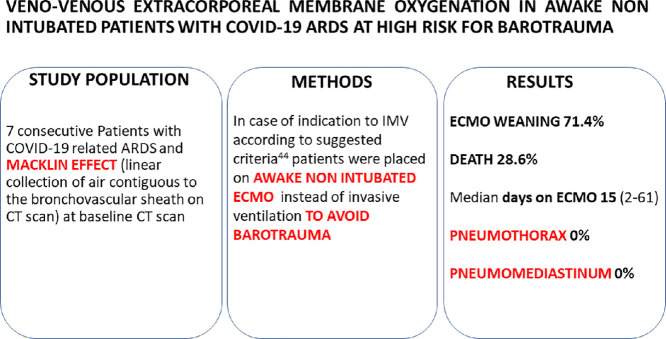

Objectives: To assess the efficacy of an awake venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VV-ECMO) management strategy in preventing clinically relevant barotrauma in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) at high risk for pneumothorax (PNX)/pneumomediastinum (PMD), defined as the detection of the Macklin-like effect on chest computed tomography (CT) scan.

Design: A case series.

Setting: At the intensive care unit of a tertiary-care institution.

Participants: Seven patients with COVID-19-associated severe ARDS and Macklin-like radiologic sign on baseline chest CT.

Interventions: Primary VV-ECMO under spontaneous breathing instead of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV). All patients received noninvasive ventilation or oxygen through a high-flow nasal cannula before and during ECMO support. The study authors collected data on cannulation strategy, clinical management, and outcome. Failure of awake VV-ECMO strategy was defined as the need for IMV due to worsening respiratory failure or delirium/agitation. The primary outcome was the development of PNX/PMD.

Measurements and Main Results: No patient developed PNX/PMD. The awake VV-ECMO strategy failed in 1 patient (14.3%). Severe complications were observed in 4 (57.1%) patients and were noted as the following: intracranial bleeding in 1 patient (14.3%), septic shock in 2 patients (28.6%), and secondary pulmonary infections in 3 patients (42.8%). Two patients died (28.6%), whereas 5 were successfully weaned off VV-ECMO and were discharged home.

Conclusions: VV-ECMO in awake and spontaneously breathing patients with severe COVID-19 ARDS may be a feasible and safe strategy to prevent the development of PNX/PMD in patients at high risk for this complication.

Key Words: COVID-19, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, barotrauma, mechanical ventilation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, Macklin effect

Graphical Abstract

PATIENTS WITH CORONAVIRUS DISEASE 2019 (COVID-19) frequently develop acute respiratory distress Syndrome (ARDS) with admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) and institution of mechanical ventilation.1, 2, 3 Several studies suggest that pneumomediastinum (PMD) and pneumothorax (PNX) frequently occur in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19–related ARDS, with a reported rate of 12% to 20%.4, 5, 6 Patients with COVID-19 with ARDS are at higher risk for PMD/PNX occurrence as compared with patients with ARDS due to other than COVID-19 causes.6 , 7 A higher than expected incidence of PMD/PNX also was observed in patients with COVID-19 not requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).8, 9, 10 Notably, PNX/PMD have been reported to occur despite the use of lung-protective mechanical ventilation strategies.4 , 6 , 7 , 11 Unfortunately, PNX/PMD have difficult, non-standardized management,4 , 11 , 12 and mortality rates for patients with COVID-19 with ARDS who develop PNX/PMD may be >60%.4 , 6 , 13

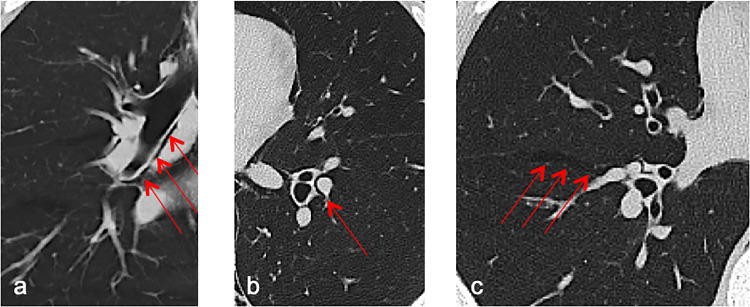

A Macklin-like radiologic sign on chest computed tomography (CT) scan (ie, linear collection of air contiguous to the bronchovascular sheath on lung parenchyma windowed CT images14 , 15) (Fig 1 ) is a consistent, highly reproducible predictor of barotrauma in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 with ARDS 8 to 12 days before overt PNX/PMD development (reported sensitivity: 89.2%, specificity: 95.6%, overall accuracy: 94.2%).4 , 16 Of note, Palumbo et al16 reported an almost perfect inter-reader agreement for the detection of this radiological sign.

Fig 1.

Macklin-like radiologic sign on lung parenchyma window chest computed tomography scans (red arrows). (A) A crescent collection of air contiguous to the right main bronchus (coronal view) to the (B) left inferior lobar bronchovascular bundle, and (C) within the main right fissure.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is an extracorporeal life support technique that is used to support or replace lung function in case of severe respiratory failure refractory to conventional strategies.17 Accordingly, ECMO generally is instituted in patients already receiving IMV, although cases of “awake” ECMO for nonintubated patients have been described.18, 19, 20, 21

The study authors, therefore, hypothesized that nonintubated patients with COVID-19 with severe ARDS and at high risk for barotrauma (ie, patients already with Macklin effect on CT scan) might benefit from early, awake ECMO and avoidance of IMV.

In this case series, the study authors present characteristics, management protocols, and outcomes of the first 7 patients managed according to this strategy.

Methods

For this observational study, the authors obtained Ethical Committee approval (Comitato Etico Regionale per la Sperimentazione Clinica della Regione Toscana [Regional Ethics Committee for Clinical Experimentation of the Tuscany Region]; protocol no. 20729). They enrolled all consecutive adult (age ≥18) patients with COVID-19 ARDS who underwent awake venovenous (VV) ECMO implantation instead of IMV, after the detection of Macklin-like radiological Sign14 on chest CT scan by a trained radiologist.

Criteria for VV-ECMO implantation are described below.

The authors collected data from 7 patients enrolled in the period between March 1, 2021 (when the authors started searching systematically for Macklin sign on chest CTs),4 to June 1, 2021.

COVID-19 ARDS was defined as a documented infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 together with clinical and radiological signs of ARDS according to Berlin criteria.22 Documented infection was defined as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 RNA detection on nose and throat swabs or bronchoalveolar lavage using multiplexed-tandem polymerase chain reaction technology.

Patients who were already under IMV at the time of VV-ECMO implantation were excluded from the study.

ECMO Implantation Algorithm

General management of patients with COVID-19 patients at the authors’ institution follows international guidelines and recommendations regarding the institution of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) and invasive ventilation and consideration for ECMO support.18 , 23, 24, 25, 26 Awake pronation for nonintubated patients with COVID-19 with ARDS, with or without continuous positive airway pressure, also is used at the authors’ institution.27 , 28

All patients with moderate-to-severe (as defined by the ratio of arterial oxygen tension to a fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FIO2 ≤200 mmHg)22 COVID-19–related ARDS received chest CT at the discretion of attending clinicians. Patients were considered for IMV according to criteria suggested by Pisano et al.29

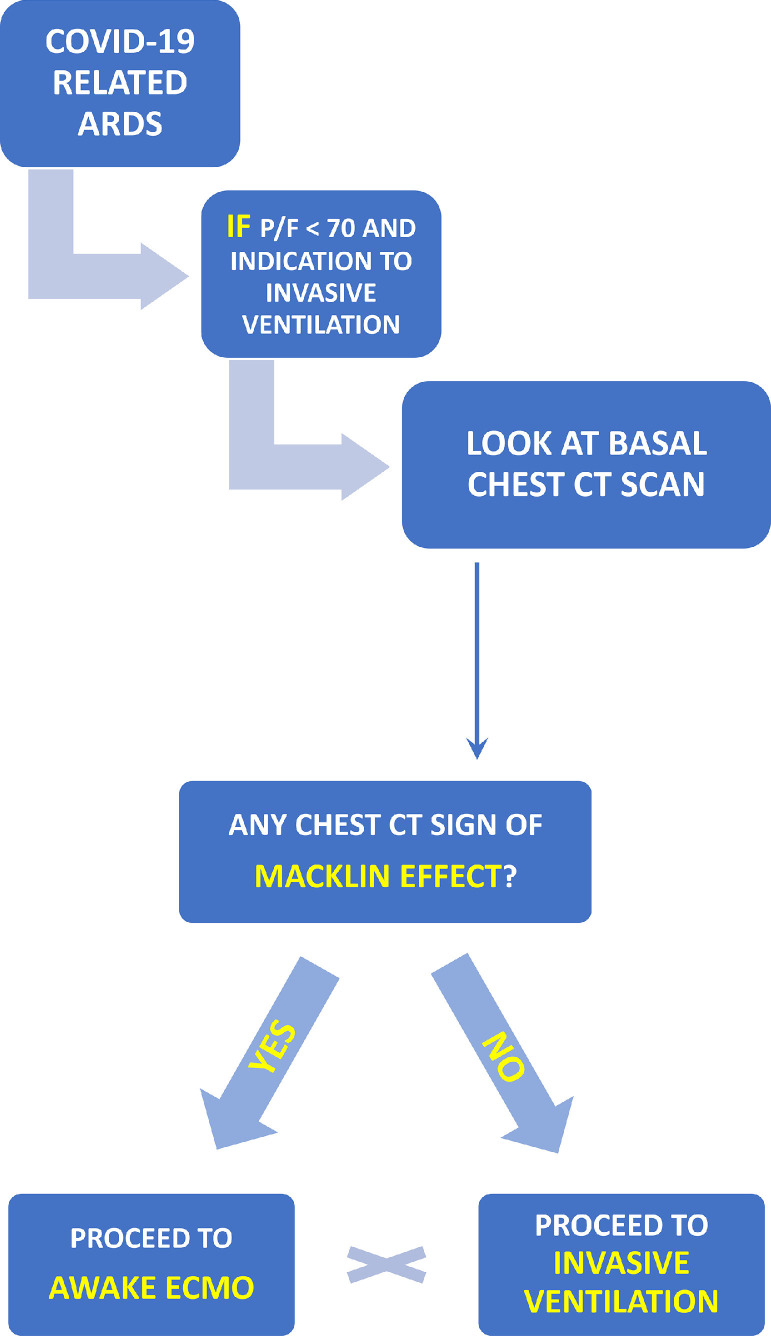

However, in the case of detection of Macklin-like radiological sign on the first chest CT scan performed in the emergency department in non-intubated patients with severe COVID-19 ARDS, the authors decided to avoid intubation and proceed directly with VV-ECMO implantation. Macklin-like radiological sign effectively predicts the subsequent development of PNX/PMD in mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 with ARDS.4 , 16 The study authors, therefore, decided to proceed directly with ECMO to maintain spontaneous ventilation and avoid further barotrauma in patients already at risk for severe complications, such as PNX/PMD (Fig 2 ).

Fig 2.

Awake ECMO implantation algorithm. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. CT, computed tomography; EMCO,

The decision to proceed with VV-ECMO as the initial strategy instead of IMV, including potential advantages and risks, was discussed with each patient, and each patient provided consent.

ECMO Cannulation and Management Protocol

Cannulation was performed using a transthoracic echocardiography-guided approach. The decision to use a femoro-jugular, femoro-femoral, or a single, double-lumen, internal jugular cannula30 configuration was at the discretion of attending clinicians.

Before site cannulation, in all patients, ultrasound color Doppler was performed to assess the dimension and patency of target vessels and exclude the presence of thrombi.

During cannulation, patients were placed in the supine position, and, after local anesthesia and mild sedation, cannulation was performed. During the cannulation maneuvers, 5 patients received oxygen through a high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC), and 2 patients (previously on helmet continuous positive airway pressure) through a nonrebreathing mask with an oxygen reservoir.

The decision to proceed with tracheal intubation after ECMO initiation was individualized and based on clinical signs of persistent respiratory distress despite optimization of NIV and ECMO support, marked agitation requiring deep sedation, cardiovascular failure, or an inability to protect airways.

Anticoagulation during ECMO was maintained with a continuous infusion of unfractionated heparin, titrated to achieve an Anti-factor Xa activity of 0.2 to 0.4. Anti-factor Xa monitoring represents the institutional preference since assessing the common pathway of the coagulation cascade may be the most reliable measure of the anticoagulation status.31 An heparin bolus (5,000 international units) was administered before cannulation.

The ECMO machines used in the authors’ case series were the Cardiohelp HLS 7.0 (Getinge AB, Göteborg, Sweden) in 5 patients and the Rotaflow PLS (Getinge AB, Göteborg, Sweden) in 2 patients. ECMO flow was 2.5 L/min to 5 L/min.

Study Outcomes and Data Collection

This study aimed to assess the efficacy of awake ECMO management in preventing clinically relevant barotrauma in patients with COVID-19 with severe ARDS and at high risk for PNX/PMD based on CT scan evaluation if treated with IMV.

The primary outcome was the development of PNX/PMD after the institution of VV-ECMO.

Along with baseline characteristics, data collection included comorbidities, chronic medications, COVID-19–specific data, concomitant medical treatment, ECMO settings, and outcomes data (occurrence of PNX/PMD, hospital survival, awake ECMO strategy failure [defined as the need for intubation for worsening respiratory failure or agitation after ECMO initiation], duration of ECMO support, length of ICU and hospital stay, and adverse events during support).

Statistical Analysis

A convenience sample was considered for this analysis. All data were stored in an electronic database. Dichotomous and categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, whereas continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard deviations in case of normal distribution or median and interquartile range in case of non-normal distribution. Given the small sample size and the study design, the authors performed only a descriptive analysis.

All analyses were performed with Stata (version 15, StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Concomitant Treatment

During the study period, the study authors enrolled a total of 7 consecutive patients with severe COVID-19 ARDS, PaO2/FIO2 ratio <70, and Macklin-like radiological sign at the baseline CT scan who underwent ECMO implantation instead of IMV. The topographic distribution of the Macklin-like radiological sign within the lungs was found to be peripheral (adjacent to segmental/subsegmental bronchial branches) in five 5 out of 7 cases (71.4%) and central (adjacent to lobar bronchial branches) in the remaining 2 (29.6%). Patients were followed up for a total of 117 ± 18 days.

The majority of patients were men (71%) with a mean age of 51.71 ± 12.46 (range 41-67) years. All patients had at least 1 comorbidity (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Received Awake ECMO Without Invasive Ventilation

| Characteristic | Pt 1 | Pt 2 | Pt 3 | Pt 4 | Pt 5 | Pt 6 | Pt 7 | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | M | M | M | M | F | M | F | |

| Age, y | 62 | 67 | 32 | 57 | 57 | 41 | 46 | |

| Weight, kg | 120 | 100 | 85 | 90 | 70 | 87 | 67 | |

| Height, cm | 175 | 170 | 180 | 180 | 165 | 170 | 151 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 39.1 | 34.6 | 26.2 | 27.7 | 25.7 | 29.4 | 24.6 | |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

|

No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 (28.5%) |

|

No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 1 (14.3%) |

|

Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 3 (42.8%) |

| Concomitant treatment | ||||||||

|

Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 (85.7%) |

|

No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | 2 (28.5%) |

|

Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | 3 (42.8%) |

|

No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | 1 (14.3%) |

|

No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 1 (14.3%) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Pt, patient.

only before ECMO.

All patients received steroids, and most patients were on antibiotics. Most patients received cardiovascular support with vasopressor or inotropes during ECMO support (Table 1).

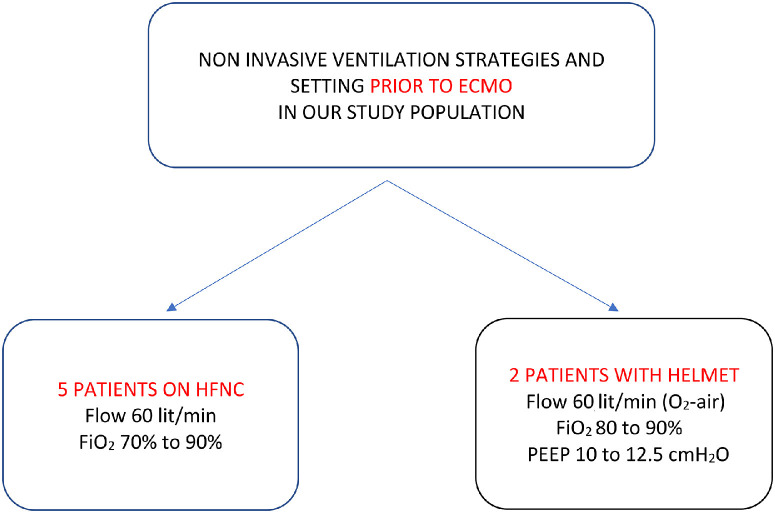

All patients received oxygen through HFNC/NIV before ECMO (Fig 3 ), although all of them received oxygen through HFNC during ECMO. One patient underwent awake pronation on NIV before ECMO implantation.

Fig 3.

Noninvasive ventilation strategies prior to ECMO implantation. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; HFNC, high-flow nasal cannula; PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure.

The median time between the onset of symptoms and ICU admission and from ICU admission and the start of ECMO support are presented in Table 1.

Baseline Respiratory Parameters and ECMO Configuration

ECMO cannulation was femoro-femoral in 4 patients, femoro-jugular in 2 patients, whereas 1 patient received a single, double-lumen internal jugular cannula (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

ECMO setting, complications, and outcome

| Variables | Value (N=7) |

|---|---|

| Blood gas analysis at time of ECMO implantation | |

|

53 ± 9.0 |

|

47 ± 5.1 |

|

72 ± 48.3 |

|

7.41 ± 0.11 |

|

56 ± 8.9 |

| ECMO details | |

|

7 (100%) |

|

4 (57.1%) |

|

2 (28.5%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

| Complications | |

|

4 (57.1%) |

|

2 (28,5%) |

|

2 (28.5%) |

|

2 (28.6%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

2 (28.5%) |

|

3 (42.8%) |

| Outcomes | |

|

0 (0.0%) |

|

0 (0.0%) |

|

2 (28.5%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

1 (14.2%) |

|

5 (71.4%) |

|

2 (28.6%) |

| Length of stay | |

|

5 (1-10) |

|

7 (1-20) |

|

15 (2-61) |

|

29 (2-47) |

|

32 (4-47) |

ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; ICU: intensive care unit; IQR: interquartile range; MOF: multiple organ failure; NIV: non-invasive ventilation; PaCO2: arterial partial carbon dioxide tension; PaO2: arterial partial oxygen tension

Blood gas analysis parameters at the time of ECMO implantation are presented in Table 2. Notably, PaO2/FIO2 ratio was 56 ± 8.9.

The median duration of the ECMO support was 15 (2-71) days.

Complications and Outcomes

Complications and outcomes are presented in Table 2. No patient developed PNX, PMD, or other signs of barotrauma.

In 1 patient (14.2%), tracheal intubation was performed 18 hours after the start of ECMO support due to persistent hypoxemia and worsening respiratory mechanics. In this case, a third venous cannula was added to improve venous return, leading to restored ECMO efficacy. This patient survived hospital discharge. This patient was considered a case of awake ECMO failure (Table 2).

A total of 2 patients (28.6%) died because of multiorgan failure as a consequence of septic shock secondary to bacterial superinfection. One of the 2 patients was intubated 3 hours before death. The authors did not consider this as ECMO failure as the patient was intubated due to worsening of cognitive function and hemodynamics requiring high-dose inotropes and vasopressors and not for worsening respiratory failure. The 2 patients who died received femoro-femoral cannulation.

One patient developed intracranial bleeding (subarachnoid hemorrhage) without indication to surgical treatment, according to neurosurgeons. The patient ultimately recovered and was discharged home.

No pulmonary embolism was observed.

At the time of this report, all survived patients have been discharged home.

Discussion

Key Findings

In this observational study, the study authors found that the early institution of VV-ECMO in patients with COVID-19 with severe ARDS and at high risk for barotrauma is feasible and resulted in no barotrauma event. These results are particularly encouraging considering the high risk of barotrauma in patients with COVID-19 with ARDS4 , 16 and the high mortality rates for patients who developed this complication.6

Relationship to Previous Studies

The use of ECMO in awake, spontaneously breathing patients has been described previously in several case series in patients with ARDS,32 cardiogenic shock,33 waiting for lung transplantation,34 immunocompromised,35 and in mixed respiratory failure populations,36 including cases of ECMO before intubation.19 , 35 , 37

In addition, the successful application of the VV-ECMO approach instead of IMV has already been described in patients with COVID-19.19 , 20 , 37 , 38 Schmidt et al reported a successful case of awake VV-ECMO in a patient with severe ARDS who refused intubation.19 Similarly, Azzam et al reported the case of a patient with extensive surgical emphysema, PMD, and bilateral PNX, in which ECMO was used instead of mechanical ventilation.20 The patient survived and was discharged home. In a small case series of 7 patients by Assanangkornchai et al, 4 patients ultimately required intubation, and 1 died.37

Compared to all these studies, in the authors’ case series, the decision to start awake VV-ECMO instead of IMV was undertaken after the evaluation of chest CT scans that classified patients at high risk for subsequent barotrauma development. The authors’ previous experience in patients with COVID-19 with ARDS showed that Macklin-like radiological sign has an 89% sensitivity and a 95% specificity in predicting PNX/PMD development; ie, 33 out of 39 Macklin-positive patients (84%) developed overt PNX/PMD within the next 12 days.4 , 16 On the contrary, in the present study, the authors found 0 cases of PNX/PMD out of 7 Macklin-positive patients. To the best of their knowledge, this is the first description of ARDS management and extracorporeal life support algorithm, including Macklin-like radiological sign to stratify a patient's risk. Furthermore, this is also the first study in which the early detection of Macklin-like radiological sign led to a change in clinical management. The use of awake VV-ECMO without IMV probably allowed the authors to avoid PNX or PMD development despite the high risk.4 , 16 Indeed, the study authors believe that this is the most interesting finding of their study (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Awake Spontaneous Breathing During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Prevention of barotrauma | Only performed in experienced ECMO centers |

| Maintenance of respiratory muscles and diaphragm tone; less impact on functional residual capacity | High work of breathing with increase in oxygen demand and CO2 production |

| Less V/Q mismatch | Risk of high transpulmonary pressure with the risk of patient self-induced lung injury |

| Improved venous return due to negative inspiratory pressure | Difficulty in monitoring ventilation parameters and airway pressures |

| Less sedation | Collapse in IVC during inspiration with difficulties in maintaining ECMO flow |

| Patient cooperation to treatment | Need for highly skilled teams |

| Possible reduction of secondary respiratory infections (VAP) | Need for 1:1 nursing |

| Patients can follow rehabilitation, exercise training and nutrition | Higher costs of care |

| Patients can better interact with relatives and staff | Need for anticoagulation |

Abbreviations: ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IVC, inferior vena cava; P-SILI, patient self-induced lung injury; VAP, ventilator-associated pneumonia; V/Q, ventilation/perfusion.

Mortality and intubation rate in this study are comparable to a previous case series on awake VV-ECMO in COVID-19 and non-COVID ARDS patients32 , 37 and are lower as compared with case series on immunocompromised patients.35 Comparison with data from other series is generally difficult, as in several cases awake ECMO was not the first strategy, and patients underwent IMV first,21 , 36 but the authors’ results here are nevertheless encouraging. Interestingly, the mortality rate is lower as compared with large case series on VV-ECMO in patients with COVID-19 with ARDS.39 , 40 However, this study has a very small sample size, and, therefore, comparison with large case series should be interpreted with caution.

Significance of Study Findings

There is a strong rationale for the use of VV-ECMO in the treatment of respiratory failure in awake, spontaneously breathing patients that previously has been reviewed.18 In particular, awake ECMO allows patients to avoid several side effects related to prolonged sedation and paralysis, reduce the risk of secondary infections related to prolonged IMV, and avoid possible complications of additional invasive procedures, such as tracheostomy. Furthermore, patients on awake VV-ECMO may undergo early active physiotherapy, with potential long-term benefits and shorter recovery time in terms of functional capacity and neuropsychological recovery.

In addition to these potential advantages, the authors’ data suggest that awake VV-ECMO without intubation is feasible in severe COVID-19 ARDS and may have the additional advantage of preventing barotrauma-related complications.

The authors’ management strategy is based on their observation that patients with COVID-19 ARDS with Macklin-like radiological sign have a very high risk of developing barotrauma despite protective IMV,4 , 16 that barotrauma is common in COVID-19 ARDS patients,6 and the associated mortality rate is >60%.6 , 13 , 41 The authors, therefore, hypothesized that patients with severe COVID-19 ARDS and Macklin-like radiological sign on chest CT scan might benefit from the early application of awake VV-ECMO rather than IMV, considering that their preliminary results show a halved mortality rate in these high-risk patients.

Patients with COVID-19 ARDS may be the ideal candidate for such a strategy, as dissociation between the degree of hypoxia and clinical signs of respiratory distress has been reported frequently in patients with COVID-19.42 This may help in maintaining wakefulness with minimal anxiolysis and potentially reduce the risk of self-induced lung injury by avoiding excessive respiratory drive.43 , 44

The study authors believe that their findings may have relevant clinical implications. Their data suggest for the first time that in COVID-19 severe ARDS progression of barotrauma from clinically silent (Macklin-like radiological sign) to overt PNX/PMD may be avoided successfully by the early application of alternative strategies, such as VV-ECMO. Although this might seem excessive, the authors should consider the 60% mortality rate for patients with COVID-19 ARDS with barotrauma, which in the authors’ opinion, justifies the application of a resource-consuming technology, such as ECMO. Although they performed their studies in COVID-19 ARDS, the authors’ findings encourage exploring the clinical significance of Macklin-like radiological effect and alternative management strategies also in non-COVID-19 ARDS.

It might be argued whether the early application of a risky procedure such as ECMO before conventional strategies (including rescue strategies, such as proning and inhaled nitric oxide) is justified. This remains a key issue to be determined, as complications of ECMO are well described.45 Indeed, 1 patient enrolled in the authors’ study developed subarachnoid hemorrhage, from which the patient recovered. Nevertheless, major complications, such as hemorrhagic stroke and massive bleeding, were similar between patients with ARDS treated with versus without ECMO in the recent ECMO to Rescue Lung Injury in Severe ARDS (EOLIA) trial,46 although the ischemic stroke rate was even lower in the ECMO group. Furthermore, mechanical ventilation is associated with a relatively high rate of complications itself, including barotrauma (6%-10% of patients with ARDS receiving invasive ventilation), ventilator-associated pneumonia, and adverse effects of prolonged sedation and immobilization. Notably, with the exception of prone positioning, none of currently recommended rescue strategies for severe ARDS has been proven to be effective in improving outcomes,47 , 48 and some (eg, recruitment maneuvers, inhaled nitric oxide) actually may be harmful.49 , 50 On the contrary, there is some evidence that ECMO ultimately may improve survival in patients with ARDS.51 Accordingly, the authors do believe that early ECMO may be considered and justified in high-risk patients (such as those at high risk for barotrauma) and that future studies should be focused on identifying such patients.

An interesting and challenging aspect of the authors’ described approach regards the potential of patient self-induced lung injury (P-SILI).52, 53, 54 The main mechanism leading to P-SILI is supposed to rely upon large inspiratory efforts imposed on severely injured lungs during mechanical ventilation, either invasive or noninvasive.55 Although not addressed yet, P-SILI remains a theoretical risk when keeping patients awake on ECMO, especially if they become agitated or when they do physical therapy. In such conditions, patients can induce wide swings in transpulmonary pressures despite breathing spontaneously. However, in the authors’ experience, the use of ECMO offered some advantages in this regard. Restoring the gas exchange by ECMO assistance contributed to blunting the major stimulus for a high respiratory drive and altered respiratory mechanics in patients with ARDS, consisting in gas exchange impairment. In the authors’ series, the normalization of gas exchange by ECMO limited respiratory efforts significantly. They very closely clinically monitored the patients’ spontaneous ventilation, looking for signs of respiratory distress throughout the ICU stay. Any sign of increased effort was immediately managed through a fine modulation of the respiratory trigger by both regulating the sweep flow and titrating pharmacologic effects of remifentanil and dexmedetomidine.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study has several strengths. The authors’ management strategy is based on previous evidence showing the high accuracy and reproducibility of Macklin-like radiological sign in predicting PNX/PMD, the relatively high prevalence of this condition among patients with COVID-19 with ARDS, and the high mortality associated with this condition. The application of awake VV-ECMO and avoidance of IMV has a strong rationale and increasingly is suggested as an alternative strategy.

This study has some limitations. The sample size is small; therefore, the authors do acknowledge that their positive results may be a chance finding. However, the sample size is comparable to that of previous studies on awake VV-ECMO focused on patients with ARDS.35 , 37

In the authors’ awake patients, they did not measure esophageal pressure, so only the clinical assessment of patients’ respiratory effort was achieved. However, close clinical monitoring was effective in guiding ECMO and anxiolysis management. This study has all of the limitations of observational studies. However, this is the first description of this approach. The authors do not have a control group, and the study is not randomized; therefore, these findings only can be considered hypothesis-generating, and no definitive conclusion can be drawn. In particular, the efficacy of an ECMO-first strategy in this setting requires to be tested in randomized trials. It is possible that the low mortality rate observed in this study was related to the early institution of ECMO. However, this would further support an ECMO-first strategy in the authors’ patients, should their findings be confirmed.

The authors cannot exclude that the application of ultra-protective mechanical ventilation instead of ECMO also could result in no barotrauma events. However, this would have required intubation anyway and, hence, potentially exposed patients to adverse effects of mechanical ventilation.

Future Studies and Prospects

Future studies should confirm in broader populations and different settings the accuracy and clinical relevance of Macklin-like radiological sign in predicting barotrauma in patients with ARDS. In addition, future studies should aim to identify optimal timing (if any) of repeated chest CT scan for patients with ARDS and initial CT negative for Macklin-like radiological sign. Furthermore, future studies should confirm that the application of alternative management strategies, such as early VV-ECMO, in spontaneously ventilating patients can avoid the development of barotraumas in patients with COVID-19 and non-COVID patients with ARDS and improve outcomes. Future studies should investigate whether ultra-protective mechanical ventilation also could be feasible and effective in preventing barotrauma in high-risk patients. Finally, randomized controlled trials will be needed to confirm that prevention of barotrauma translates into improved outcomes.

Conclusions

The authors found that the early application of awake VValECMO without IMV in patients with COVID-19 with severe ARDS at high risk for barotrauma (defined as evidence of Macklin-like radiological sign on chest CT) resulted in no barotrauma events and low intubation and mortality rates. Future studies should confirm these findings in broader populations and different clinical settings (eg, non-COVID-19 ARDS).

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Zangrillo A, Beretta L, Scandroglio AM, et al. Characteristics, treatment, outcomes and cause of death of invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19 ARDS in Milan, Italy. Crit Care Rescusc. 2020;22:200–211. doi: 10.1016/S1441-2772(23)00387-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grasselli G, Zangrillo A, Zanella A, et al. Baseline Characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574–1581. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1345–1355. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belletti A, Palumbo D, Zangrillo A, et al. Predictors of pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum in mechanically ventilated COVID-19 patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:3642–3651. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2021.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuinness G, Zhan C, Rosenberg N, et al. Increased incidence of barotrauma in patients with COVID-19 on invasive mechanical ventilation. Radiology. 2020;297:E252–E262. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belletti A, Todaro G, Valsecchi G, et al. Barotrauma in coronavirus disease 2019 patients undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation: A systematic literature review. Crit Care Med. 2022;50:491–500. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemmers DHL, Abu Hilal M, Bnà C, et al. Pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in COVID-19: Barotrauma or lung frailty? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00385–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00385-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinelli AW, Ingle T, Newman J, et al. COVID-19 and pneumothorax: A multicentre retrospective case series. Eur Respir J. 2020;56 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02697-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palumbo D, Campochiaro C, Belletti A, et al. Pneumothorax/pneumomediastinum in non-intubated COVID-19 patients: Differences between first and second Italian pandemic wave. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;88:144–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamouri S, Samrah SM, Albawaih O, et al. Pulmonary barotrauma in COVID-19 Patients: Invasive versus noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. Int J Gen Med. 2021;14:2017–2032. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S314155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kahn MR, Watson RL, Thetford JT, et al. High incidence of barotrauma in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019. J Intensive Care Med. 2021;36:646–654. doi: 10.1177/0885066621989959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Azzawi M, Douedi S, Alshami A, et al. Spontaneous subcutaneous emphysema and pneumomediastinum in COVID-19 patients: An indicator of poor prognosis? Am J Case Rep. 2020;21 doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chopra A, Al-Tarbsheh AH, Shah NJ, et al. Pneumothorax in critically ill patients with COVID-19 infection: Incidence, clinical characteristics and outcomes in a case control multicenter study. Respir Med. 2021;184 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106464. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murayama S, Gibo S. Spontaneous pneumomediastinum and Macklin effect: Overview and appearance on computed tomography. World J Radiol. 2014;6:850–854. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i11.850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Macklin CC. Transport of air along sheaths of pulmonic blood vessels from alveoli to mediastinum: Clinical implications. Arch Intern Med. 1939;64:913–926. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palumbo D, Zangrillo A, Belletti A, et al. A radiological predictor for pneumomediastinum/pneumothorax in COVID-19 ARDS patients. J Crit Care. 2021;66:14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2021.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintel M, Bartlett RH, Grocott MPW, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1257–1276. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer T, Santini A, Bottino N, et al. “Awake” extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): Pathophysiology, technical considerations, and clinical pioneering. Crit Care. 2016;20:150. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1329-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt M, Pineton de Chambrun M, Lebreton G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation instead of invasive mechanical ventilation in a patient with severe COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;203:1571–1573. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202102-0259LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azzam MH, Mufti HN, Bahaudden H, et al. Awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in coronavirus disease 2019 patients without invasive mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3:e0454. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T, Yin P-F, Li A, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome treated with awake extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in a patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:2467–2470. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: Guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Crit Care Med. 2020;48:e440–e469. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alhazzani W, Evans L, Alshamsi F, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines on the management of adults with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the ICU: First update. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e219–e234. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foti G, Giannini A, Bottino N, et al. Management of critically ill patients with COVID-19: Suggestions and instructions from the coordination of intensive care units of Lombardy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2020;86:1234–1245. doi: 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.14762-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shekar K, Badulak J, Peek G, et al. Extracorporeal life support organization coronavirus disease 2019 interim guidelines: A consensus document from an international group of interdisciplinary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation providers. ASAIO J. 2020;66:707–721. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paternoster G, Sartini C, Pennacchio E, et al. Awake pronation with helmet continuous positive airway pressure for COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome patients outside the ICU: A case series. Med Intensiva (Engl Ed) 2020;46:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2020.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sartini C, Tresoldi M, Scarpellini P, et al. Respiratory parameters in patients with COVID-19 after using noninvasive ventilation in the prone position outside the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2020;323:2338–2340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pisano A, Yavorovskiy A, Verniero L, et al. The impact of anesthetic regiment on outcomes in adult cardiac surgery: A narrative review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:711–729. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2020.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bazan VM, Taylor EM, Gunn TM, et al. Overview of the bicaval dual lumen cannula. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;37:232–240. doi: 10.1007/s12055-020-00932-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colman E, Yin EB, Laine G, et al. Evaluation of a heparin monitoring protocol for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3325–3335. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.08.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoeper MM, Wiesner O, Hadem J, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation instead of invasive mechanical ventilation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:2056–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-3052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montero S, Huang F, Rivas-Lasarte M, et al. Awake venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021;10:585–594. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuab018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoopes CW, Kukreja J, Golden J, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge to pulmonary transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;145:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stahl K, Schenk H, Kühn C, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in non-intubated immunocompromised patients. Crit Care. 2021;25:164. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03584-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crotti S, Bottino N, Ruggeri GM, et al. Spontaneous breathing during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in acute respiratory failure. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:678–687. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Assanangkornchai N, Slobod D, Qutob R, et al. Awake venovenous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for coronavirus disease 2019 acute respiratory failure. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3:e0489. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Loyalka P, Cheema FH, Rao H, et al. Early usage of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in the absence of invasive mechanical ventilation to treat COVID-19-related hypoxemic respiratory failure. ASAIO J. 2021;67:392–394. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbaro RP, MacLaren G, Boonstra PS, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support in COVID-19: An international cohort study of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization registry. Lancet. 2020;396:1071–1078. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32008-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lorusso R, Combes A, Coco VL, et al. ECMO for COVID-19 patients in Europe and Israel. Intensive Care Med. 2021;47:344–348. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06272-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Belletti A, Landoni G, Zangrillo A. Pneumothorax and barotrauma in invasively ventilated patients with COVID-19. Respir Med. 2021;187 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2021.106552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilkerson RG, Adler JD, Shah NG, et al. Silent hypoxia: A harbinger of clinical deterioration in patients with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:2243.e5–2243.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Battaglini D, Robba C, Ball L, et al. Noninvasive respiratory support and patient self-inflicted lung injury in COVID-19: A narrative review. Br J Anaesth. 2021;127:353–364. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spinelli E, Mauri T, Beitler JR, et al. Respiratory drive in the acute respiratory distress syndrome: Pathophysiology, monitoring, and therapeutic interventions. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:606–618. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05942-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zangrillo A, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. A meta-analysis of complications and mortality of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15:172–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Combes A, Hajage D, Capellier G, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1965–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1253–1263. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute PETAL Clinical Trials Network. Moss M, Huang DT, et al. Early neuromuscular blockade in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1997–2008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1901686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griffiths MJD, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Writing Group for the Alveolar Recruitment for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Trial (ART) Investigators. Cavalcanti AB, Suzumura ÉA, et al. Effect of lung recruitment and titrated positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) vs low PEEP on mortality in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318:1335–1345. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.14171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Combes A, Peek GJ, Hajage D, et al. ECMO for severe ARDS: Systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:2048–2057. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06248-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brochard L, Slutsky A, Pesenti A. Mechanical ventilation to minimize progression of lung injury in acute respiratory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:438–442. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1081CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bellani G, Grasselli G, Teggia-Droghi M, et al. Do spontaneous and mechanical breathing have similar effects on average transpulmonary and alveolar pressure? A clinical crossover study. Crit Care. 2016;20:142. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brochard L. Ventilation-induced lung injury exists in spontaneously breathing patients with acute respiratory failure: Yes. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:250–252. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4645-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carteaux G, Parfait M, Combet M, et al. Patient-self inflicted lung injury: A practical review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:2738. doi: 10.3390/jcm10122738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]