Abstract

The kinetics of recovery after inhibition of growth by erythromycin and clarithromycin were examined in Staphylococcus aureus cells. After inhibition for one mass doubling by 0.5 μg of the antibiotics/ml, a postantibiotic effect (PAE) of 3 and 4 h duration was observed for the two drugs before growth resumed. Cell viability was reduced by 25% with erythromycin and 45% with clarithromycin compared with control cells. Erythromycin and clarithromycin treatment reduced the number of 50S ribosomal subunits to 24 and 13% of the number found in untreated cells. 30S subunit formation was not affected. Ninety minutes was required for resynthesis to give the control level of 50S particles. Protein synthesis rates were diminished for up to 4 h after the removal of the macrolides. This continuing inhibition of translation was the result of prolonged binding of the antibiotics to the 50S subunit as measured by 14C-erythromycin binding to ribosomes in treated cells. The limiting factors in recovery from macrolide inhibition in these cells, reflected as a PAE, are the time required for the synthesis of new 50S subunits and the slow loss of the antibiotics from ribosomes in inhibited cells.

The postantibiotic effect (PAE) is the phenomenon of continued bacterial growth inhibition after the removal of inhibitory antibiotics from the growth medium. It has been observed for a variety of different antibiotics, and its duration depends on the specific compound, its concentration, and the duration of treatment (22, 28). The length of the PAE has important clinical implications for both the duration of drug treatment, the dosage, and the problem of patient noncompliance (8, 9). A number of different microorganisms have been shown to exhibit a PAE, including Haemophilus influenzae (20), mycobacteria (18), and pneumococci (26). Studies of the macrolide PAE on Staphylococcus aureus cells have been particularly numerous (10, 11, 16, 17, 25, 29). In addition to the macrolides, a PAE has been demonstrated in S. aureus with other antibiotics, including tobramycin (9), ampicillin (11), and isepamicin (10). Although many studies have investigated the PAE, only a few have examined the molecular events occurring during the persisting inhibition (2, 15, 32). Mechanisms for the PAE have been discussed by MacKenzie and Gould (22), who have suggested reversible antibiotic target binding, enzyme resynthesis, and the repair of damaged cell structures as possible causes.

Macrolide antibiotics, such as erythromycin and clarithromycin, have two effects in susceptible bacterial cells. They inhibit protein synthesis by preventing the translocation activity of the 50S ribosomal subunit (30, 31, 33), and we have shown that they also inhibit the biosynthesis of the 50S ribosomal subunit in growing bacterial cells (3–5, 7). Recovery from both inhibitory activities is presumably required for cells to resume growth after antibiotic removal. A PAE has been demonstrated in S. aureus cells with the macrolide antibiotics erythromycin (11, 16, 17, 20, 29), clarithromycin (16), azithromycin (10, 16), and roxithromycin (16, 17). The PAE demonstrated by cells after macrolide removal suggests that one or both of these processes is limiting for recovery from drug treatment. This investigation was conducted to examine the events involved in the recovery from macrolide antibiotic inhibition by looking at ribosomal subunit synthesis, translation, and antibiotic loss from affected cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell growth and viability measurements.

Studies were conducted with S. aureus RN1786, provided by J. Sutcliffe of Pfizer. Stock solutions of clarithromycin (Abbott Laboratories) and erythromycin (Sigma) were made at 1 mg/ml in methanol. Cells were grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth (TSB) as described previously (3–6). Growth rates were measured by following the increase in cell density in a Klett-Summerson colorimeter. Viable cell counts were measured by serial dilution of cells in A salts (24) followed by plating 10 μl on square TSB agar plates by the method of Jett et. al (19). Colonies were counted after 48 h at 37°C.

PAE measurements.

Cells were exposed to erythromycin and clarithromycin at 0.5 μg/ml, the MIC of each drug under these conditions (7), until the cell density had doubled. To examine the PAE, macrolide-treated cells were collected by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 10 min, washed with 10 ml of TSB at room temperature, and resuspended in the initial volume of TSB. [3H]uracil (39 Ci/mmol; NEN) at 1 μCi/ml (2 μg/ml) was added to the culture, which was then divided into separate 5-ml samples. At intervals, a 10-min chase with 200 μg of uracil/ml was carried out before the cells were collected by centrifugation, washed, and stored frozen for ribosomal subunit analysis. To measure protein synthesis rates, the cells were labeled with [35S]methionine and cysteine (TRAN35S-LABEL; ICN Pharmaceuticals) to 1 μCi/ml. Three samples of 0.2 ml were collected at 2.5, 5, and 10 min and precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid. 35S-methionine and cysteine in proteins were measured by liquid scintillation counting. Samples were taken before and after drug removal to examine effects on ribosome synthesis and function. Untreated control cells were examined in an identical fashion.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation.

Cell lysis and sucrose gradient sedimentation of ribosomal subunits were performed as described previously (5, 6) except that an SW41 rotor was used and the centrifugation was at 200,000 × g for 4 h. Gradient fractions were mixed with 3 ml of ScintiSafe gel, and the incorporation of [3H]uracil into RNA was measured by liquid scintillation counting. Cells labeled with [3H]uracil and 14C-erythromycin were processed and centrifuged in a similar fashion. The absorbance at 254 nm for each gradient was detected with an ISCO Model UA-5 absorbance monitor and captured for computer storage by Dynamax software (Rainin). Integrated optical density units were converted into picomoles of 50S subunits from the relationship 1 A260 unit = 45 pmol (23).

Loss of 14C-erythromycin from cells.

The loss of 14C-erythromycin (55.1 mCi/mmol; NEN) from cells was examined by incubating a 12-ml TSB culture with the antibiotic at 0.5 μg/ml (0.03 μCi/ml) for one cell doubling. A 1-ml sample was removed from the culture and filtered through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Millipore), and the cells were collected on the filter for isotope counting. The remainder of the culture was collected on a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter, washed with 5 ml of TSB, and resuspended in 11 ml of TSB at 37°C. Samples of 1 ml were filtered at intervals to examine the loss of 14C-erythromycin from the cells. The culture medium was also collected to measure 14C-erythromycin accumulation. The dried filters were counted in a toluene-PPO (2,5-diphenyloxazole) cocktail, and 0.5 ml of the filtrate was counted in 5 ml of Scintisafe counting fluid.

RESULTS

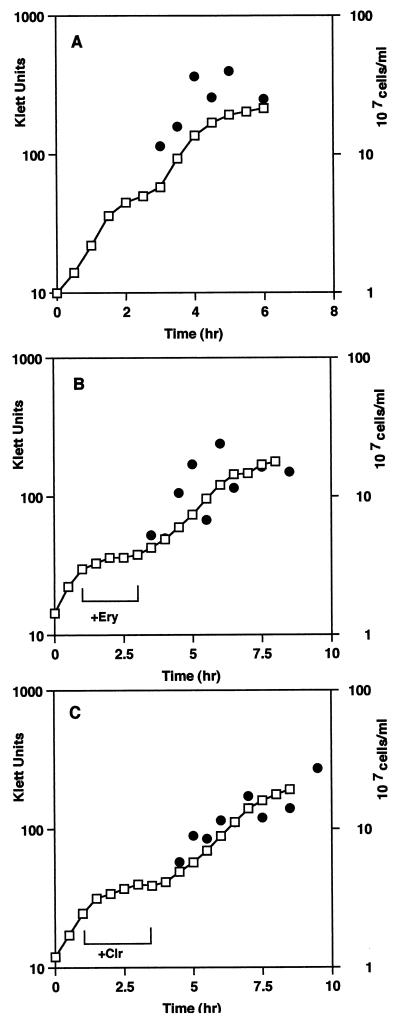

Figure 1 shows the growth characteristics of control and macrolide-treated cells. A significant inhibition of the growth rate was found for cells incubated with each drug, with generation times of 240 (erythromycin) and 270 (clarithromycin) min compared with a control rate of 45 min (Table 1). The PAE was apparent after removal of the macrolides. New growth rates were established which were two to three times slower than the untreated control rate (Table 1). This difference was also reflected in the viable-cell count (Fig. 1). Untreated-cell numbers increased, with a doubling time of 45 min after a short lag. After removal of the antibiotics, the cell numbers increased at a lower rate, three times less than that of the control, for up to 3 h (Table 1). The PAE, defined as the time for a 10-fold increase in viable-cell numbers after antibiotic removal, was 3 h for erythromycin and 5 h for clarithromycin (Fig. 1B and C).

FIG. 1.

Growth rates and viable-cell numbers for control and macrolide-treated cells. The increase in cell density (□) and cell number (●) was measured for control (A) and erythromycin (Ery) (B)- or clarithromycin (Clr) (C)-treated cells before and after antibiotic removal. The duration of antibiotic treatment is indicated by a bracket. The cell viability results are the averages of five experiments, with a standard error of ±20%.

TABLE 1.

Growth rates, cell numbers, protein synthesis rates, and ribosomal subunit synthesis levels before and after antibiotic removala

| Compound | Doubling time (min)

|

No. of cells (108/ml)

|

Protein synthesis (35S cpm)

|

Ribosome synthesisb

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre

|

Post

|

|||

| 30S | 50S | 30S | 50S | |||||||

| None | 45 | 45 | 0.9 | 3.2 | 2,372 | 4,846 | 21 | 38 | 19 | 38 |

| Erythromycin | 240 | 90 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 472 | 2,504 | 23 | 9 | 23 | 36 |

| Clarithromycin | 270 | 105 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 238 | 1,370 | 24 | 5 | 24 | 38 |

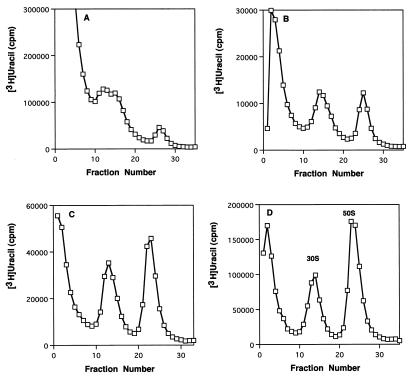

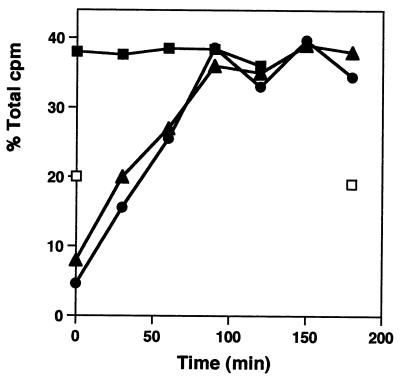

One effect of macrolides on cells is an inhibition of the formation of the 50S ribosomal subunit. Ribosomal subunit synthesis was examined in cells recovering from antibiotic treatment. Growth for one mass doubling in the presence of either erythromycin or clarithromycin reduced the number of 50S subunits to 24 and 13% of their levels in untreated cells. 30S subunit synthesis was not affected, as we have shown before (3–5). After drug removal, a period of 90 min was required to resynthesize the normal amount of 50S particles. Figure 2 shows representative sucrose gradient profiles of ribosomal subunits made in control cells and at intervals after the removal of clarithromycin. The kinetics of this resynthesis are shown in Fig. 3, with equivalent rates of reformation observed after inhibition by either antibiotic (Table 1).

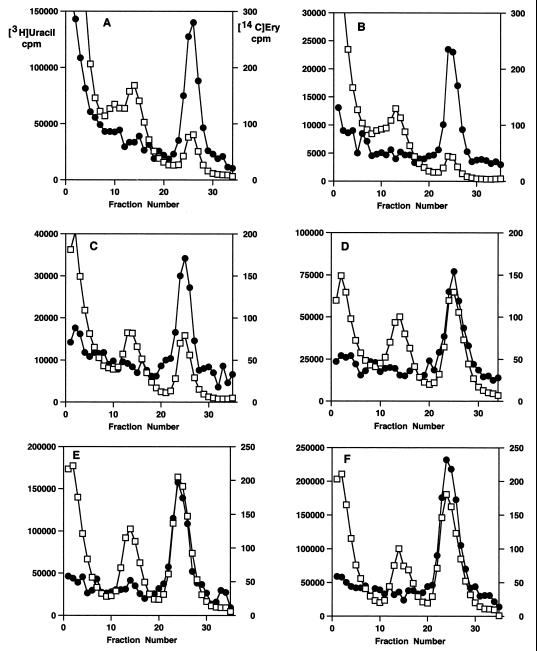

FIG. 2.

Sucrose gradient profiles of ribosomal subunits labeled with [3H]uracil before and after antibiotic removal. Profiles of clarithromycin-treated cells before (A) and at 30 (B) and 60 (C) min after washing and resuspension are shown. (D) Profile of untreated cells after washing and resuspension. Sedimentation is from left to right.

FIG. 3.

Kinetics of 50S ribosomal subunit re-formation. The percentages of the total gradient cpm in the 30S and 50S subunit regions of the sucrose gradients are shown for untreated cells (■) and for cells recovering from erythromycin (▴) and clarithromycin (●) treatments. 30S subunit levels at 0 and 180 min are also shown (□). The results are the averages of five experiments, with a standard error of ±4%.

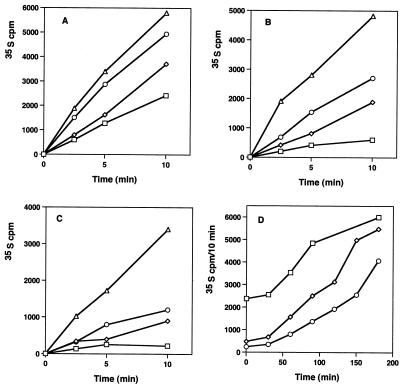

The other effect of macrolides on cell function is an inhibition of the translational activity of the 50S particle. The recovery of protein synthesis activity was also examined after the removal of antibiotics from treated cells. Figure 4 shows the rates of 35S-labeled amino acid incorporation into proteins in control cells and in cells after macrolide exposure. Before drug removal, protein synthesis rates were reduced to 20 and 10% of control values (Table 1). After macrolide removal, new rates were established which were 51 and 28% of the control rates (Fig. 4D). A period of 3 h was required for the control rate of protein synthesis to be regained after erythromycin treatment, and 4 h was needed following clarithromycin inhibition.

FIG. 4.

Rates of 35S amino acid incorporation into proteins in control and antibiotic-treated cells before and after antibiotic removal. (A) Protein synthesis rates in control cells at 0 (□), 60 (◊), 90 (○), and 180 (▵) min. (B) Protein synthesis rates in erythromycin-treated cells at 0 (□), 60 (◊), 90 (○), and 180 min (▵). (C) Protein synthesis rates in clarithromycin-treated cells at 0 (□), 60 (◊), 90 (○), and 180 min (▵). (D) Relative rates of protein synthesis (35S cpm/10 min) for untreated cells (□) and for erythromycin (◊)- and clarithromycin (○)-treated cells following antibiotic removal. The results are the averages of four experiments, with a standard error of ±4%.

These results suggested that although the cells had recovered their normal complement of 50S subunits, they were unable to immediately resume uninhibited rates of protein synthesis. This implies that the macrolides were being retained in the cells after removal from the culture medium. This possibility was investigated by using 14C-erythromycin to examine the rate of loss from treated cells after drug removal. Figure 5 shows sucrose gradient profiles of cells labeled with 14C-erythromycin and then with [3H]uracil after antibiotic removal. The increase in 50S subunit formation is apparent from this data, with normal subunit ratios established by 2 h (Fig. 5E). It is also apparent that erythromycin remained bound to 50S subunits in recovering cells for up to 3 h after removal of the drug from the culture (Fig. 5F). The kinetics of erythromycin loss and retention are shown in Fig. 6. The observed t1/2 was 1.5 h. About 50% of the drug was retained in cells for as long as 3 h after its removal from the medium.

FIG. 5.

Sucrose gradient profiles of cells labeled with 14C-erythromycin ([14C]ery) (●) before washing and resuspension and with [3H]uracil (□) afterwards. (A) Cells collected before erythromycin removal. (B) Cells collected 15 min after erythromycin removal. (C) Cells collected after 30 min. (D) Cells collected after 60 min. (E) Cells collected after 120 min. (F) Cells collected after 180 min.

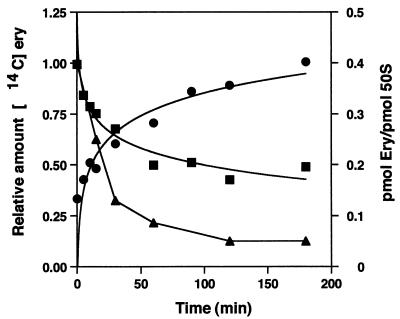

FIG. 6.

Kinetics of 14C-erythromycin ([14C]ery) retention and loss from cells and ribosomes after washing and resuspension. Relative 14C-erythromycin cpm in cells (■) and in culture medium (●) and loss of erythromycin (Ery) bound to 50S subunits (▴) are shown.

Erythromycin bound to 50S particles was quantitated by measuring the areas of the 50S subunits in each gradient and converting them to picomoles of subunits. The amount of bound erythromycin was calculated from the specific activity of the 14C-labeled antibiotic. After antibiotic removal, 40% of the subunits contained bound erythromycin, and this amount fell to a level of 5% after 120 min (Fig. 6) with an observed t1/2 of 30 min.

DISCUSSION

These experiments represent the first investigation of the molecular events associated with the recovery of S. aureus cells from macrolide antibiotic inhibition. Since these compounds have two different but related effects on ribosomes in cells, both the inhibition of 50S synthesis and the inhibition of translation need to be overcome in order for the cells to resume normal growth.

As we have shown previously, continued growth of the cells with either antibiotic present leads to a substantial reduction in the fraction of 50S ribosomal subunits in the cells (3, 4). Erythromycin at 0.5 μg/ml reduced the amount to 24% of the control value, and clarithromycin at the same concentration reduced the amount to 13%. By contrast, 30S subunit formation was unaffected. Removal of the macrolides allowed resynthesis of the deficient particles to proceed. Normal levels of ribosomes were found in cells 90 min after antibiotic removal, and the kinetics of resynthesis were the same for erythromycin- and clarithromycin-treated cells. This period of time was equivalent to the doubling time found for the cells after antibiotic removal.

Macrolide treatment also reduced the rates of protein synthesis to 20 (erythromycin) and 10% (clarithromycin) of the control values. Recovery from this inhibition was only 50% complete for erythromycin-treated cells after 90 min, and only 28% of the activity was regained in clarithromycin-treated cells. After 3 h in the absence of the drugs, there was still a persistent inhibition by clarithromycin of translational activity in these cells. The continuing inhibition of protein synthesis after drug removal seems to be the limiting factor for the increases in growth rate and cell number, since both rates were reduced by a factor of 2 (erythromycin) or 3 (clarithromycin) in treated cells. The full recovery of 50S ribosomal subunits in these cells implies a preferential synthesis of ribosomal proteins, since functioning ribosomes are needed to make new ribosomal proteins.

The continued inhibition of protein synthesis could be accounted for by the presence of bound erythromycin (and presumably clarithromycin) for up to 3 h after the removal of antibiotics from the culture. About 50% of the drug initially present in the cells was retained during this period. Part of the reason for the slow loss of erythromycin (and clarithromycin) from cells may be the tight binding of the 50S-macrolide complex. The Kd for erythromycin bound to 50S subunits from S. aureus has been reported to be about 2 × 10−9 M (12, 13), and clarithromycin binding to 50S subunits from H. pylori has a Kd of 2.3 × 10−10 M (14). Mao and Putterman (23) reported that only 36% of ribosome-bound erythromycin had dissociated from 50S particles after 20 h at 4°C. Since 50S subunits in polyribosomes are refractory to erythromycin inhibition (1, 27), the gain in protein synthesis activity is a combination of loss from the cells and diminished 50S binding. A good correlation was observed between the rate of increase of protein synthesis after erythromycin inhibition and the rate of loss of erythromycin from 50S subunits.

The results indicate a difference between the rate of loss of erythromycin from 50S subunits and from S. aureus cells. A t1/2 of 0.5 h was found for drug loss from ribosomes, while a t1/2 of 1.5 h was observed for the loss from the cells. These results suggest that export of the antibiotic from the cells may be the limiting factor for removal and not the direct dissociation from the ribosomal particles.

The PAE for erythromycin in S. aureus has been examined by other investigators. At a concentration of 1 μg/ml, no PAE was found after an exposure of 0.5 h (29). Exposures for 1 to 3 h at this concentration resulted in PAEs of 1.5 and 3.2 h (11, 17). These times are similar to the results found with erythromycin in this study.

Two different methodologies have been used to remove antibiotics from cells in studies of the PAE. Some investigators have simply diluted treated cells by a factor sufficient to reduce the drug to a subinhibitory concentration, and they have then measured the resumption of growth by cell viability measurements (11, 16, 17, 20, 25, 29). Other studies involved removal of antibiotics from the medium by centrifugation or filtration of the cells with washing to remove the drug (10, 18, 21). In these cases the cells are normally resuspended at the same density as before the drug removal. This protocol was used in our studies because it reflects more closely the situation in patients being treated for an infection. Noncompliance with a prescribed drug treatment regimen would involve drug removal, with viable cells remaining at a specific number. The PAE under these conditions would be similar to the situation examined in this study.

The PAE for macrolides can be accounted for by two factors. One is the time required to reassemble the 50S subunit pool to restore the normal 30S-to-50S ratio in cells. Under the conditions examined, normal levels were attained in 90 min following drug removal. The second factor to be overcome is the persistance of the macrolide bound to 50S particles. A slow dissociation of the drug-ribosome complex seems to be the limiting factor for resumption of normal rates of growth and cell division. Clarithromycin is a better inhibitor of S. aureus translation and 50S subunit formation than erythromycin (4, 5), and a longer recovery time for inhibition by this drug would be expected. It may also bind more strongly to S. aureus ribosomes (14).

This work establishes a molecular basis for the continued inhibition of growth after macrolide antibiotic removal from S. aureus cells. It provides clear evidence for the two sites of inhibitory activity for these compounds and the requirements for recovery from antibiotic effects. Studies with other protein synthesis inhibitors should reveal similar mechanisms for recovery from translational inhibition.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are pleased to acknowledge the generous financial support of Pfizer Pharmaceuticals for the conduct of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson S, Kurland C G. Elongating ribosomes are refractory to erythromycin. Biochimie. 1987;69:901–904. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(87)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barmada S, Kohlhepp S, Leggett J, Dworkin R, Gilbert D. Correlation of tobramycin-induced inhibition of protein synthesis with postantibiotic effect in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:2678–2683. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.12.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champney W S, Burdine R. Macrolide antibiotics inhibit 50S ribosomal subunit assembly in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2141–2144. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.9.2141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champney W S, Burdine R. 50S ribosomal subunit synthesis and translation are equivalent targets for erythromycin inhibition in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1301–1303. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.5.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Champney W S, Burdine R. Azithromycin and clarithromycin inhibition of 50S ribosomal subunit formation in Staphylococcus aureus cells. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:119–123. doi: 10.1007/s002849900290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Champney W S, Tober C L. Inhibition of translation and 50S ribosomal subunit formation in Staphylococcus aureus cells by eleven different ketolide antibiotics. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:418–425. doi: 10.1007/s002849900403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Champney W S, Tober C L, Burdine R. A comparison of the inhibition of translation and 50S ribosomal subunit formation in Staphylococcus aureus cells by nine different macrolide antibiotics. Curr Microbiol. 1998;37:412–417. doi: 10.1007/s002849900402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daikos G K. Continuous versus discontinuous antibiotic therapy: the role of the post-antibiotic effect and other factors. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1991;27:157–160. doi: 10.1093/jac/27.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.denHollander J G, Fuursted K, Verbrugh H A, Mouton J W. Duration and clinical relevance of postantibiotic effect in relation to the dosing interval. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:749–754. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuentes F, Izquierdo J, Martin M M, Gomez-Lus M L, Prieto J. Postantibiotic and sub-MIC effects of azithromycin and isepamicin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:414–418. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerber A U, Craig W A. Growth kinetics of respiratory pathogens after short exposures to ampicillin and erythromycin in vitro. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1981;8:81–91. doi: 10.1093/jac/8.suppl_c.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldman R C, Capobianco J O. Role of an energy-dependent efflux pump in plasmid pNE24-mediated resistance to 14- and 15-membered macrolides in Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1973–1980. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.10.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman R C, Kadam S K. Binding of novel macrolide structures to macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B-resistant ribosomes inhibits protein synthesis and bacterial growth. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:1058–1066. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.7.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldman R C, Zakula D, Flamm R, Beyer J, Capobianco J. Tight binding of clarithromycin, its 14-(R)-hydroxy metabolite and erythromycin to Helicobacter pylori ribosomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1496–1500. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.7.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guan L, Blumenthal R M, Burnham J C. Analysis of macromolecular biosynthesis to define the quinolone-induced postantibiotic effect in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2118–2124. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton-Miller J M T. In-vitro activities of 14,15- and 16-membered macrolides against Gram-positive cocci. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;29:141–147. doi: 10.1093/jac/29.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton-Miller J M T, Shah S. Post-antibiotic effects of miocamycin, roxithromycin and erythromycin on Gram-positive cocci. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1993;2:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0924-8579(93)90048-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horgen L, Legrand E, Rastogi N. Postantibiotic effect of amikacin, rifampin, sparfloxacin, clofazimine and clarithromycin against Mycobacterium avium. Res Microbiol. 1997;148:673–681. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(99)80066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jett B D, Hatter K L, Huycke M, Gilmore M S. Simplified agar plate method for quantifying viable bacteria. BioTechniques. 1997;23:648–650. doi: 10.2144/97234bm22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuenzi B, Segessenmann C, Gerber A U. Postantibiotic effect of roxithromycin, erythromycin and clindamycin against selected Gram-positive bacteria and Haemophilus influenzae. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;20:39–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/20.suppl_b.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li R C, Lee S W, Kong C H. Correlation between bactericidal activity and postantibiotic effect for five antibiotics with different mechanisms of action. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:39–45. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacKenzie F M, Gould I M. The post-antibiotic effect. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32:519–537. doi: 10.1093/jac/32.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mao J C-H, Putterman M. The intermolecular complex of erythromycin and the ribosome. J Mol Biol. 1969;44:347–361. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(69)90180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nougayrede A, Berthaud N, Bouanchaud D H. Post-antibiotic effects of RP 59500 with Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1992;30:101–106. doi: 10.1093/jac/30.suppl_a.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spangler S K, Lin G, Jacobs M R, Appelbaum P C. Postantibiotic effect and postantibiotic sub-MIC effect of levofloxacin compared to those of ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin against 20 pneumococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:1253–1255. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.5.1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tai P-C, Davis B D. Action of antibiotics on chain-initiating and on chain-elongating ribosomes. Methods Enzymol. 1979;59:851–862. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)59130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vogelmann B S, Craig W A. Postantibiotic effects. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1985;15:37–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/15.suppl_a.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webster C, Ghazanfar K, Slack R. Sub-inhibitory and post-antibiotic effects of spiramycin and erythromycin on Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;22:33–39. doi: 10.1093/jac/22.supplement_b.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitman M S, Tunkel A R. Azithromycin and clarithromycin: overview and comparison with erythromycin. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1992;13:357–368. doi: 10.1086/646545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams J D, Sefton A M. Comparison of macrolide antibiotics. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;31(Suppl. C):11–26. doi: 10.1093/jac/31.suppl_c.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yan S, Bohach G A, Stevens D L. Persistent acylation of high-molecular-weight penicillin-binding proteins by penicillin induces the postantibiotic effect in Streptococcus pyogenes. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:609–614. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.3.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuckerman J M, Kaye K M. The newer macrolides. Azithromycin and clarithromycin. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1995;9:731–745. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]