Abstract

We investigated the white matter correlates of personality profiles predictive of subjective well-being. Using principal component analysis to first determine the possible personality profiles onto which core personality measures would load, we subsequently searched for whole-brain white matter correlations with these profiles. We found three personality profiles that correlated with the integrity of white matter tracts. The correlates of an “optimistic” personality profile suggest (a) an intricate network for self-referential processing that helps regulate negative affect and maintain a positive outlook on life, (b) a sustained capacity for visually tracking rewards in the environment and (c) a motor readiness to act upon the conviction that desired rewards are imminent. The correlates of a “short-term approach behavior” profile was indicative of minimal loss of integrity in white matter tracts supportive of lifting certain behavioral barriers, possibly allowing individuals to act more outgoing and carefree in approaching people and rewards. Lastly, a “long-term approach behavior” profile’s association with white matter tracts suggests lowered sensitivity to transient updates of stimulus-based associations of rewards and setbacks, thus facilitating the successful long-term pursuit of goals. Together, our findings yield convincing evidence that subjective well-being has its manifestations in the brain.

Subject terms: Cognitive neuroscience, Emotion, Social behaviour, Social neuroscience

Introduction

What makes one experience more frequent positive feelings, become better adjusted socially and stay in good mental and physical health? A large body of research has shown that subjective well-being, which includes perceived mental and physical health as well as rewarding social interactions1, has less to do with objective circumstances such as age, gender, race, income, education or marital status and more to do with stable personality traits2–5. Although the effects of outside circumstances on well-being are often statistically weak6–8, people persist in their impression that factors such as a relocation, a higher income, getting married or having children would lead to a substantial increase in subjective well-being9–11. This perceived importance of outside circumstances is likely the result of a focusing illusion12–14, i.e., the tendency to focus on the changes that singular events bring while overlooking various other factors that will eventually also influence the actual feeling states. This is of course not to say that situational factors are not influential in subjective well-being.

The current understanding of well-being15–18 is that genes (temperament) and personality together dictate a baseline of happiness. There is a range of values by which this baseline can fluctuate (i.e. a dynamic equilibrium;16), and this is where external events19,20, an individual’s goals and values21,22 as well as social comparisons with peers23–25 can exert most of their influence. Consequently, it is the interaction between genes and personality, on one hand, and situational factors and their interpretations, on the other hand, that give a complete picture to understanding well-being. The current study investigates the existence of well-being correlates in brain anatomy. Because we cannot study variations in brain anatomy for the person × situation interaction in total (i.e., across a multitude of different situations), and because the situation factor alone cannot be expected to manifest in brain anatomy, we concentrate on the person factor here.

Among personality factors that influence subjective well-being, the most researched ones have been a dispositional optimistic outlook on life26–28, a particular pattern of Big Five personality dimensions (i.e. high extraversion and low neuroticism;29–32), higher dispositional sensitivity to rewards than to setbacks (i.e., a high aroused behavioral activation (BAS) and/or a lowly aroused behavioral inhibition system (BIS);33–36) as well as the habitual use of particular emotion regulation strategies (i.e. a frequent use of cognitive reappraisal and/or a rare use of suppression of negative affect;37–39). These personality factors not only independently predict subjective well-being but they also share significant variance with each other (e.g. Big Five with cognitive reappraisal40–43 and with BIS/BAS44; optimism with Big Five45–48 and with cognitive reappraisal49; BAS with use of cognitive reappraisal and/or low suppression of negative emotions35,50,51). The question then arises of how exactly these personality factors position themselves in relation to each other and in their predictive power over subjective well-being. Our study aimed to investigate this by running a principal component analysis (PCA) that revealed the underlying commonalities between these psychological constructs.

One of the objectives of neuroscience is to map brain-behavioral connections which may yield important insights about the processes that possibly underlie psychological constructs. Several studies exist already on the gray and white matter correlates of personality measures52–56 and of subjective well-being57. However, a limitation of these studies is that they have focused on one personality measure at a time (see58). A likely possibility is that some personality measures cluster more often together than others, giving rise to personality “profiles” or “types”59–61. For example, high extraversion and high conscientiousness tend to cluster together but are both separate from high neuroticism60,62. Therefore, it might be wiser to investigate the neural correlates of personality profiles instead of individual factors. This has only very recently been attempted. For example, Li et al.63 have looked into the grey matter correlates of personality profiles. However, no study to our knowledge has investigated the white matter correlates of personality profiles, particularly profiles that predict subjective well-being.

White matter tracts connect various grey matter regions and their integrity is a marker of how well the corresponding grey matter regions communicate with each other (e.g.,55). Therefore, individual variability in white matter tracts may underlie variability in personality profiles. Accordingly, in our study, we correlated the “positive personality profiles” from the PCA with the markers of white matter integrity. Because no other study has investigated the white matter correlates of personality profiles that are predictive of subjective well-being, we based our hypotheses on the few studies that independently probed relevant concepts (i.e., Big Five, BIS/BAS, emotion regulation strategies) in relation to white matter integrity.

For example, several studies have linked neuroticism to decreased integrity of white matter tracts in the cingulum (CNG56,64), the uncinate fasciculus (UNC;56,65), the body of the corpus callosum (CC66,67) as well as increased integrity of the posterior CC, the corticospinal tract (CST), the inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF;68) and the inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF;67,68). Extraversion correlates negatively with white matter integrity in the posterior CC67,69 and the CNG and the IFOF69. Furthermore, the BIS scale correlates positively with the integrity of the CNG, UNC, IFOF and superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF;68). We note that some other studies have failed to find a meaningful relationship between white matter integrity and the Big Five dimensions54,58,70 or the BIS/BAS71. By contrast, the association between the habitual use of cognitive reappraisal and white matter integrity has been rather consistent, implicating the UNC72–75 and the CNG72,73. Given the above-reported correlates for isolated personality characteristics, we expected the implication of these areas in our profile study, too.

To measure white matter tracts, we used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) tract-based spatial statistics, which is a commonly used voxel-based statistical framework for understanding white matter integrity76. To operationalize white matter integrity, we looked at widely used measures in DTI: (a) fractional anisotropy (FA), a measure that describes the directionality strength of local white matter tracts, (b) axial diffusivity (AD), a measure of the degree of diffusion of water molecules parallel to the axonal tracts, and (c) radial diffusivity (RD), a mean diffusion coefficient of water molecules diffusing orthogonally to the axonal tracts. These diffusivity measures provide complementary information about white matter integrity: as FA and AD values increase (integrity increases), RD values decrease.

Results

Principal component analysis results

The PCA analysis revealed that the 16 behavioral measures loaded on five principal components (eigenvalue > 1, serving as a cutoff) (Table 1). Together, these five principal components or personality profiles explained 60.8% of the total variance (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

PCA results derived from the questionnaire data.

| Behavior data | Personality profiles derived from PCA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological constructs | Mean | Standard deviation | PCA 1 Optimism | PCA 2 Avoidant behavior | PCA 3 Short-term approach behavior | PCA 4 Long-term approach behavior | PCA 5 Pessimistic reappraisal |

| LOT optimism | 8.71 | 2.08 | 0.77 | − 0.24 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| LOT pessimism | 4.04 | 2.02 | − 0.69 | 0.08 | − 0.23 | − 0.07 | − 0.17 |

| Satisfaction with life | 26.51 | 5.33 | 0.70 | − 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.11 | − 0.05 |

| COS optimism | 69.94 | 11.01 | 0.48 | − 0.12 | − 0.31 | 0.30 | − 0.01 |

| COS pessimism | 76.99 | 14.50 | 0.00 | 0.00 | − 0.03 | − 0.12 | 0.78 |

| BIS | 20.01 | 3.64 | − 0.10 | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| BAS drive | 12.34 | 2.10 | 0.17 | 0.00 | − 0.01 | 0.73 | − 0.08 |

| BAS fun seeking | 12.26 | 1.63 | − 0.11 | − 0.39 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.33 |

| BAS reward response | 16.59 | 2.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.18 | 0.78 | − 0.08 |

| BFI openness | 7.49 | 1.88 | − 0.27 | − 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.55 | 0.14 |

| BFI Conscientiousness | 7.16 | 1.77 | 0.17 | 0.44 | − 0.01 | 0.26 | − 0.11 |

| BFI extraversion | 6.89 | 1.98 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.75 | 0.21 | − 0.13 |

| BFI agreeableness | 7.05 | 1.33 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.64 | − 0.13 | 0.11 |

| BFI neuroticism | 5.79 | 1.88 | − 0.16 | 0.82 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| ERQ reappraisal | 29.34 | 5.65 | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.51 |

| ERQ suppression | 13.45 | 4.75 | − 0.13 | − 0.03 | − 0.69 | − 0.03 | − 0.01 |

Descriptive statistics of mean and standard deviation of the behavioral questionnaires are presented. Bend correlations ‘rho’ between derived components and individual questionnaires are also provided. Bold indicates significant correlations (alpha = 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons).

Figure 1.

Total variance explained (60.8%) by the five PCA components with an eigenvalue > 1.

The first component, which we call “Optimism” loaded the LOT Optimism, COS Optimism and Satisfaction with Life positively and LOT Pessimism negatively. The second component, dubbed “Avoidant behavior”, loaded the BIS, BFI Conscientiousness and BFI Neuroticism positively and BAS Fun Seeking negatively. The third component, “Short-term approach behavior” loaded BFI Extraversion, BFI Agreeableness and BAS Fun Seeking positively but ERQ Suppression negatively. The fourth component, “Long-term approach behavior”, loaded all three BAS components and BFI Openness positively. Finally, the fifth component “Pessimistic reappraisal” loaded COS Pessimism and ERQ Reappraisal positively (Table 1).

White matter voxel-based results

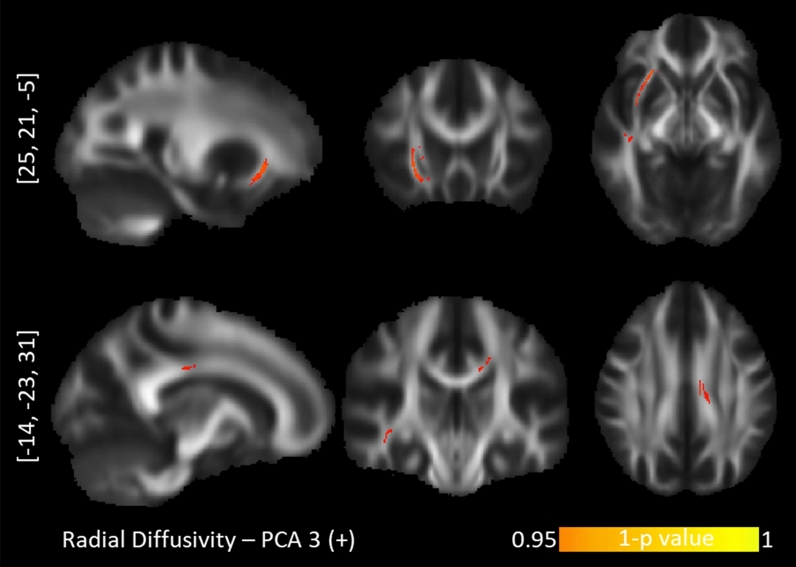

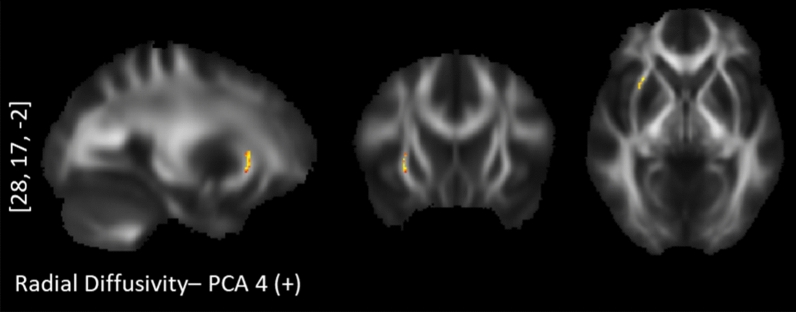

The tract-based spatial statistics correlations between personality profiles and diffusion maps are presented with Table 2. Of these five PCA components, “Optimism” (PCA 1), “Short-term approach behavior” (PCA 3) and “Long-term approach behavior” (PCA 4) revealed tract-based findings for the probabilistic diffusion maps. Specifically, the “Optimism” component correlated positively with AD values in the right hemisphere exclusively (Fig. 2): the corticospinal tract (CST), the superior longitudinal fasciculus (SLF), anterior cingulum bundle (CNG), anterior corpus callosum (CC), anterior thalamic radiation (ATR) and uncinate fasciculus (UNC). The component for “Short-term approach behavior” correlated negatively with the FA values in the left hemisphere exclusively, namely the splenium of the CC, inferior longitudinal fasciculus (ILF), and UNC (Fig. 3). This component further correlated positively with the RD values in the right UNC/inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (IFOF) and right SLF and left CNG (Fig. 4). Lastly, the component for “Long-term approach behavior” correlated positively with the RD values in the right UNC (Fig. 5).

Table 2.

TBSS randomized results with TFCE at p < .05 after 5000 permutations.

| Behavioral component | DTI marker | Cluster size | Peak voxel | Anatomy | Projections to gray matter regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Positive correlation with diffusion maps: PC 1—Optimism 1. LOT (+) 2. SWLS (+) 3. COS optimism (+) 4. LOT pessimism (−) |

AD | 1781 | [21, − 18, 43] |

R corticospinal tract 72.5% R dorsal superior longitudinal fasciculus 33.7% |

From primary motor and primary somatosensory cortex to afferent nerves in the body106,184 |

| 102 | [17, 20, 39] |

R anterior corpus callosum 100% R anterior thalamic radiation 100% R anterior cingulum bundle 92.2% |

Connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and frontal poles135,136,185,186 | ||

| 81 | [40, − 12, 28] |

R dorsal superior longitudinal fasciculus 100% R corticospinal tract 50.6% |

From angular gyrus to premotor cortices and caudal dorsolateral prefrontal cortex105,106 | ||

| 70 | [27, 35, − 1] |

R anterior thalamic radiation 100% R rostrum of corpus callosum 92.86% R uncinate fasciculus 100% |

Ventromedial prefrontal cortex and orbitofrontal cortex135,136,187 | ||

| 32 | [19, 22, 28] | R anterior cingulum bundle 100% | Anterior cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex135,136 | ||

| 21 | [6, 12, 31] | R ventral superior longitudinal fasciculus 100% | From supramarginal gyrus to ventral premotor cortex and pars opercularis105,106 | ||

|

Positive correlation with diffusion maps: PC 3—Short-term approach behavior 1. BFI Extraversion (+) 2. BFI agreeableness (+) 3. BAS fun seeking (+) 4. ERQ Suppression (−) |

RD | 905 | [25, 21, − 5] |

R Inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus 86.3% R Uncinate fasciculus |

To ventromedial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex188–190 |

| 196 | [− 14, − 23, 31] | L splenium of corpus callosum 100% | Posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus135,136 | ||

| 31 | [45, − 18, 37] | R superior longitudinal fasciculus II 96.8% | The premotor cortices, supplementary motor areas, pars opercularis106 | ||

|

Negative correlation with diffusion maps: PC 3—Short-term approach behavior 1. BFI Extraversion (+) 2. BFI agreeableness (+) 3. BAS fun seeking (+) 4. ERQ Suppression (−) |

FA | 7602 | [25, 22, − 6] | R Inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus | |

| 6960 | [− 10, − 17, 29] | L splenium of corpus callosum 49.6% | Posterior cingulate cortex135,187 | ||

| 124 | [− 32, − 78, − 1] |

L splenium of corpus callosum 93.5% L inferior longitudinal fasciculus 100% |

Medial parietal, medial occipital135,187 | ||

| 85 | [− 13, 16, 51] | L Corpus callosum (body) | Parietal to precentral regions135,136 | ||

| 83 | [− 22, − 83, 10] |

L splenium of corpus callosum 100% L inferior longitudinal fasciculus 100% |

Medial parietal, medial occipital135,187 | ||

| 56 | [− 11, − 86, 23] |

L splenium of corpus callosum 100% L inferior longitudinal fasciculus 42.9% |

Medial parietal, medial occipital135,187 | ||

| 25 | [− 36, 23, − 12] | L uncinate fasciculus 36% | Ventromedial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, inferior frontal cortex188–190 | ||

| 20 | [− 24, 13, − 13] | L uncinate fasciculus 100% | |||

| 15 | [− 19, − 80, 19] |

L splenium of corpus callosum 100% L inferior longitudinal fasciculus 100% |

Medial parietal, medial occipital135,187 | ||

|

Positive correlation with diffusion maps: PC 4—Long-term approach behavior 1. BAS Drive (+) 2. BAS Reward (+) 3. BAS Fun seeking (+) 4. BFI Openness (+) |

RD | 97 | [28, 17, − 2] |

R uncinate fasciculus 100% R Inferior frontal-occipital fasciculus |

From anterior temporal lobes (via internal and external capsules) to inferior frontal cortex, vnPFC, orbitofrontal cortex, frontal pole188–190 |

The correlation results for behavior data with DTI maps for axial diffusivity (AD), radial diffusivity (RD) and fractional anisotropy (FA) are presented along with the cluster size, peak voxel coordinate and tract anatomy of the findings. LOT—Life LOT—Life Orientation Test. SWLS—Satisfaction With Life Scale. COS—Comparative Optimism Scale. BIS—Behavioral Inhibition System. BAS—Behavioral Approach System. BFI—Big Five Inventory. A plus (minus) sign depicts positive (negative) contributions of the behavioral measures to the principal components.

Figure 2.

TBSS positive correlations between axial diffusivity and the "Optimism" personality profile. Upper row: corticospinal tract. Second row: dorsal superior longitudinal fasciculus. Third row: anterior corpus callosum. Bottom row: anterior cingulum bundle.

Figure 3.

TBSS negative correlations between fractional anisotropy and the "Short-term approach behavior" personality profile. Upper row: inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. Middle row: inferior longitudinal fasciculus/posterior corpus callosum. Bottom row: inferior longitudinal fasciculus/posterior corpus callosum.

Figure 4.

TBSS positive correlations between radial diffusivity and the "Short-term approach behavior". Top row: inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus. Bottom row: posterior corpus callosum.

Figure 5.

TBSS positive correlations between radial diffusivity and "Long-term approach behavor": right uncinate fasciculus.

Discussion

Our study is the first to investigate the white matter correlates of personality profiles that are predictive of subjective well-being. We used PCA to determine the possible profiles onto which dispositional optimism, Big Five dimensions, BIS/BAS, ERQ and SWL would load. We then searched for whole-brain white matter correlations with these profiles, and we based our hypotheses on past structural findings for each separate psychological construct. The PCA revealed five distinct profiles, three of which correlated to white matter measures: (a) “Optimism” profile, onto which LOT Optimism, COS optimism and SWLS loaded positively and LOT Pessimism loaded negatively; (b) “Short-term approach behavior” profile, onto which Extraversion, Agreeableness and BAS Fun Seeking loaded positively and EQ Suppression loaded negatively; (c) “Long-term approach behavior” profile, onto which BAS Drive, BAS Reward Responsiveness and, to a lesser degree, BAS Fun Seeking and Openness loaded.

We found that the “Optimism” profile correlated positively with AD values in white matter tracts exclusively in the right hemisphere: the CST, the SLF, and the anterior CNG, CC and ATR. Similar to FA values, the AD reflects the magnitude of diffusion parallel to fiber tracts and thus the integrity of axons77,78. The exclusivity of our findings in the right hemisphere is in line with the proposed functional asymmetry between the left and right hemispheres concerning complementary modes of processing incoming information (e.g.79,80). While the left hemisphere processes the information in a strictly sequential and unambiguously understood monosemantic context81, the function of the right hemisphere is to simultaneously capture a vast number of possible connections and to integrate them in an ambiguous but polysemantic context81–83. Because of this functionality, the right hemisphere has been involved in a variety of integrative phenomena84–86, including helping the implicit self87 maintain a positivity bias88–90. The implicit self is a highly integrative construct that processes vast amounts of self-relevant information from cognitive (e.g., autobiographical memories), motivational (e.g., values, needs) and affective (e.g., emotions) systems in parallel87,91. Because personal experiences are inherently perceived as positive in healthy individuals92, a functional implicit self is crucial in maintaining a positivity bias by assimilating negative affective experiences within a network of predominantly positive experiences81,93. Due to this holistic nature, the implicit self is believed to be a function of the right hemisphere87,90. The incapacity to regulate negative affect and display a (somewhat normal) positivity bias underlies emotional disorders such as depression, alexithymia and suicidal ideation, which are characterized both by a lack of optimism bias53 and a functionally deficient right hemisphere79,81,94, including decreased integrity of white matter tracts95. Our study thus supports previous findings that the right hemisphere is necessary for healthy individuals to express their positivity bias.

Regarding the individual tracts in the right hemisphere underlying “Optimism”, the CST was the strongest finding in terms of cluster size. The integrity of the CST is associated with a lower baseline excitability threshold, i.e. the minimum intensity at which the motor system can evoke a motor response96,97. At the same time, CST excitability indexes the degree of “wanting” a reward98; see also99 and the certainty of upcoming rewards100,101. Our finding that dispositional optimism is foremost associated with the integrity of the CST makes it thus tempting to speculate that optimism is more embodied than we may believe. Could optimism predispose us not only toward expecting good things to happen but also toward motor readiness to go after these rewards? After all, one of the aspects of dispositional optimism bringing an adaptive advantage in life102 is its ability to make us effortlessly engage in our goals103.

Other individual white matter tracts associated with the “Optimism” profile were the dorsal SLF, and the anterior CNG, CC and ATR. The dorsal SLF is essential to the dorsal attention pathway104–106 and its integrity relates to measures of sustained goal-directed visuospatial attention in children107,108 and adults109–111. That optimism and attention deployment are critically linked is demonstrated in various behavioral and neuroimaging studies (112–115, for a theoretical account, see116). Interestingly, the integrity of the right SLF has further been connected to global visual motion sensitivity117, i.e. the ability to perceive and infer the overall movement trend of a multitude of stimuli (e.g. moving dots) with otherwise random motion. In other words, the right SLF supports seeing the forest and not the trees. This holistic perception ability is likely due to the right-side hemispheric lateralization, as discussed above. The overwhelming evidence suggests that the right SLF is involved in the endogenously controlled capacity to actively detect, follow, and respond to relevant (holistic) stimuli over prolonged periods of time. Although the SLF might not be specific to optimism bias, it might maintain it when other mechanisms are in place to generate it, e.g. by supporting long-term pursuit of desirable outcomes118.

The remaining white matter tracts whose integrity correlated with the “Optimism” component, i.e. the anterior CNG, CC, and ATR, connect brain regions that are part of the anterior midline core of the default mode network (DMN). Notably, the functional connectivity between the core nodes of the DMN positively correlates with the integrity of the CC119–121, CNG122–124 and the ATR122,125. The anterior midline node of the DMN supports internally directed thought and self-referential processing126,127, including simulating one’s (mostly optimistically biased) future128–130. The integrity of the CC, in particular, has been associated with a higher dispositional optimism131,132 and a higher resistance to updating personal beliefs in a pessimistic direction133,134. Furthermore, the gray matter endings of the anterior CC, CNG and ATR all overlap in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC;135–139). There is highly converging evidence pointing to the involvement of the vmPFC in optimism bias53,140–144, and activity in the vmPFC also correlates positively with subjective well-being145. Thus, the correlation between the optimism profile and the white matter tracts of vmPFC is not surprising.

In sum, the “Optimistic” personality profile correlated with white matter tracts that suggest a motor readiness to act upon the conviction that desired rewards are imminent (CST), a sustained capacity for visually tracking rewards in the environment (SLF) and an intricate network for self-referential processing that helps regulate negative affect and maintain a positive outlook on life (anterior CNG, CC, ATR).

We called the third PCA factor “Short-term approach behavior” because impulsivity (indexed by BAS Fun Seeking;146), extraversion and agreeableness positively loaded on it. Impulsivity, i.e. the motivation to spontaneously go after novel rewards, is a core part of both extraversion147,148 and agreeableness149, so their clustering is not surprising. Furthermore, ERQ Suppression loaded negatively, suggesting an inability to suppress impulsive urges. We note that impulsivity is operationally split into motor impulsivity and cognitive impulsivity150–153. Motor impulsivity is similar to motor readiness and correlates with CST integrity and excitability (e.g.154, see also “Optimism” profile above). By contrast, cognitive impulsivity refers to the inability to compare immediate consequences and the future events with each other and, consequently, the inability to see reasons for delaying immediate satisfaction. The relevant measures on our third PCA factor, namely BAS Fun Seeking146, extraversion147,148 and agreeableness149, measure cognitive impulsivity. Altogether, the “Short-term approach behavior” profile correlated negatively with the FA values of the left splenium of CC and left ILF but positively with the RD values of the left splenium and the right UNC/IFOF. FA and RD markers are complementary: low FA and high RD values represent compromised axons (demyelination) while high FA and low RD values represent healthy tracts77. Considering this, (impulsive) short-term approach behavior seems to increase as a function of compromised integrity in the left splenium of CC, left ILF and UNC/IFOF. These findings are in line with previous literature on extraversion and compromised posterior CC and IFOF67,69 as well as with the literature on BAS Fun-Seeking and compromised left IFOF55. Interestingly, individuals with either behavioral or substance addiction show more extensive impairments of the integrity of the CC splenium155–157 and ILF158,159. These extensive impairments of both CC and ILF are, in turn, inversely related to the levels of self-reported impulsivity156. We thus propose that a minimal loss of integrity in these tracts lifts certain barriers and predisposes individuals to be more outgoing and carefree in approaching people and rewards160,161, but too extensive a damage to their integrity is a risk factor for addiction and clinical impulsivity.

We termed the fourth PCA factor “Long-term approach behavior” due to the high loading of BAS Drive (high-intensity pursuit of desired goals) and BAS Reward Responsiveness (positive affective experience in response to rewards) and, to a lower extent, the contributions of BAS Fun Seeking and Openness. Both BAS Drive and BAS Reward Responsiveness are associated with vigorous pursuit of long-term rewards despite physical or mental challenges162, while BAS Fun Seeking points to the spontaneous pursuit of novel rewards146. Although, taken in isolation, the three BAS components point to different time windows of pursuing rewards, the combined three components are compatible with pursuing long-term goals. A high BAS Drive safeguards the behavioral maintenance of long-term goals despite obstacles while a high BAS Fun Seeking component (combined with the high BFI Openness) ensures the flexibility and readiness to spontaneously seize unexpected alternative ways of attaining the long-term goal. Finally, a high BAS Reward Responsiveness ensures appropriate positive emotional reactions when attaining each milestone on the way to achieving the final behavioral goal, a process that ensures goal pursuit.

In terms of brain structures, the “Long-term approach behavior” component correlated positively with RD values in the right UNC/IFOF: the lower the integrity between the anterior temporal lobes and the frontal cortex, particularly the orbitofrontal cortex163,164, the more prominent the long-term approach behavior. It was proposed that the UNC allows temporal lobe-based stimulus associations (e.g. between the physical properties of a stimulus and the emotions associated with it) to modify behavior via interactions with the orbitofrontal cortex163,164. These interactions between the temporal lobe and the orbitofrontal cortex would be instrumental in ensuring that stored stimulus associations reflect up-to-date reward and punishment history. Applied to the present data, one may therefore speculate that the successful behavior of keeping eyes on an end goal depends on not always allowing up to date (and likely transitory) reward and punishment information to interfere with the end goal established much earlier on.

Limitations, strengths and conclusions

We would like to point out that the analyzed sample consisted mostly of females. Given that gender plays a role in brain structure and morphology165, future studies should include a balanced sample of males and females. We tried to mitigate these confounding influences by taking age, gender, and total intracranial volume as the covariates of no-interest. Our study has the strength of focusing on personality profiles as opposed to isolated constructs and investigating the white matter correlates of the profiles predictive of subjective well-being. The correlates of an “Optimistim” personality profile suggest (a) an intricate network for self-referential processing that helps regulate negative affect and maintain a positive outlook on life, (b) a sustained capacity for visually tracking rewards in the environment and (c) a motor readiness to act upon the conviction that desired rewards are imminent. Correlates of a “Short-term approach behavior” profile were indicative of minimal loss of integrity in white matter tracts supportive of lifting certain behavioral barriers, possibly allowing individuals to act more outgoing and carefree in approaching people and rewards. Lastly, a “Long-term approach behavior” profile’s association with white matter tracts suggests lowered sensitivity to transient updates of stimulus-based associations of rewards and setbacks, thus facilitating the successful long-term pursuit of goals.

Given that personality plays a crucial role in subjective well-being, identifying the morphological correlates of personality profiles may provide important information for potential therapeutic interventions. For example, an optimistic personality profile was the strongest predictor of subjective well-being both psychologically in terms of the PCA variance and in terms of structural correlates. Some of the putative mechanisms underlying such a profile are domain-general and not specific to optimism per se, e.g., an intact system for sustained attention to holistic stimuli supported by the right SLF. It will be interesting to investigate whether trainings on targeted activities that tap into the functions of the right SLF might transfer to subjective well-being by increasing optimism. Previously, we showed that an attention bias modification training could successfully enhance optimism bias118. Future studies can investigate whether such trainings can also boost subjective well-being.

Methods

Participants

We recruited 99 healthy candidates with an age criterion between 18 and 40 years (mean age = 24.03 ± 4.39, 62 females). Recruitment was made through emails, flyers and the local participant pool at the University of Bern, Switzerland. Exclusion criteria included self-reported neurological conditions, psychoactive substance usage, left-handedness, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) specific problems such as failed image reconstruction and excessive motion artefacts observed on structural scans. For their participation, the students received either course credits or 25 Swiss francs (CHF). Participants gave written informed consent, in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Experimental procedures were approved by the ethics committee of the canton Bern, Switzerland. Five participants were excluded due to incomplete questionnaires. Both DTI and T1-weighted structural scans from all participants qualified visual inspection. Final analysis was conducted on 94 participants.

Psychological assessment

Using an online portal, all participants completed various psychological questionnaires namely, Comparative Optimism Scale; COS166, Satisfaction With Life Scale; SWLS167,168, the revised Life Orientation Test; LOT-R169,170, Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; ERQ49,171, the 10-item Big Five Inventory; BFI172,173, Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation System Scales; BIS/BAS146,174. For each participant, the psychological assessment scales amounted to 16 different variables (refer to Table 1). Using PCA allowed us to reduce the multivariate behavioral dataset into fewer meaningful components, thereby enabling a better interpretation of our psychological scales. The resulting personality profiles were then correlated with MRI-based diffusivity measures of FA, AD and RD. The PCA with varimax rotation was performed with XLSTAT175. We included the principal components with an eigenvalue > 1. Only Pearson product moment correlation coefficients exceeding 0.4 with a combined alpha level of 0.05 (Bonferroni corrected for multiple testing) were considered for our analytical interpretations.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) acquisition

MRI measurements were conducted across the study cohort within a 3 T scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) using a 64-channel head coil, at the Inselspital, University Hospital Bern, Switzerland. The MRI protocol consisted of a 3D magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE or T1-weighted) sequence with repetition time (TR) = 2300 ms, echo time (TE) = 2.98 ms, inversion time (TI) = 900 ms, flip angle = 9°, matrix size = 160 × 256 × 256 with an isotropic spatial resolution = 1mm3. 2D DTI data were acquired consisting of 12 unweighted (b = 0 s/mm2) and 90 diffusion-weighted (b = 1000 s/mm2) images, with TR/TE = 3200 ms/69 ms, flip angle = 90°, in-plane matrix size = 128 × 128 with 27 axial slices (thickness = 4 mm, spacing between slices = 5.2 mm) and an in-plane resolution of 1.7 × 1.7 mm2.

Image processing

DICOM images from the MRI were converted to NIfTI format using conversion software; dcm2niix (https://github.com/rordenlab/dcm2niix/releases). Computational image processing included tract-based spatial statistics; TBSS176 for DTI images. The processes were carried out using FSL6.0.2 (https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki) in a MATLAB 2017b environment (developed by The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, United States) utilizing the cluster service UBELIX (https://ubelix.unibe.ch/) from the University of Bern, Switzerland. ‘fsleyes’ from FSL, served as the viewing software for qualitative assessment of the images.

Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS)

TBSS performed on DTI data is a commonly used voxel-based statistical framework for understanding white matter integrity76,177. Frequently used DTI-derived parameters (from diffusivities: parallel component λ1 and perpendicular components λ2, λ3;77) include (a) FA: a measure that could explain the directionality strength of local white matter tracts, (b) AD: a diffusion measure of water molecules diffusing parallel to the axonal tracts, (c) RD: a mean diffusion coefficient of water molecules diffusing orthogonal to the axonal tracts. These diffusivity measures independently should provide complementary information about white matter pathology. For example, FA and AD, on one hand, and RD values, on the other hand, represent the degree of water diffusion parallel and perpendicular to the axonal wall, respectively77. As such, these markers are complementary: low FA and AD values and high RD values represent compromised axons (demyelination) while high FA and AD values and low RD values represent healthy tracts. TBSS76, the voxel-based approach used in this paper, utilizes extracted and skeletonized white matter tracts in the FA images of all participants. TBSS has been introduced to overcome the problems associated with the use of standard registration algorithms in other voxel-based approaches177.

We used the FSL software (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki) for the preprocessing prior to TBSS. First, eddy correction (eddy_correct) was applied on DTI images to address eddy current-induced distortions and motion artefacts. After this step, the DTI images were processed with the FMRIB Software Library’s diffusion toolbox (DTIFIT;178,179), which fits a diffusion tensor model at each voxel and generates three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, λ3). Fractional anisotropy (FA = ), axial diffusivity (AD = λ1) and radial diffusivity (RD = ) maps were hence generated.

Details of the underlying processes in the TBSS analysis stream are extensively covered in the literature180–183. In brief, for the FA maps, firstly a preprocessing erosion step was applied to remove brain edge artefacts and nullify intensities of end slices, to reduce false positives from tensor fitting. Later, FA maps across the participants were non-linearly registered to a standard template in MNI space (FMRIB58_FA template). Following registration, all FA maps were transformed to the standard MNI space with an isotropic voxel size of 1mm3, by applying the registration warps to individual images. The standardized maps were merged into a single 4D image, mean FA and its subsequent skeletonized version (WM skeleton) were created. The skeleton was restricted to WM with a threshold of FA = 0.2 and standardized FA maps were projected onto the skeleton. Non-FA maps (RD and AD) were also transformed to their respective skeletonized forms by applying the FA-derived registration and projection vectors. Finally, skeletons across the DTI maps were smoothed with an 8 mm FWHM Gaussian kernel. To find the positive and negative associations between the principal components (from PCA) and the DTI maps (FA, AD, and RD), we performed a non-parametric permutation analysis (t-test) using randomize (in FSL) with 5000 permutations, with age, gender, and total intracranial volume (TIV) as the covariates of no-interest. Only the clusters surviving a family-wise error (FWE) multiple comparison at p < 0.05 are reported.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were approved by the ethical committee of the University of Bern according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent to participate

All participants provided written consent.

Author contributions

M.D. collected the data. R.K. and D.A.M. analyzed the data. M.D., R.K., D.A.M. and T.A. wrote the manuscript. T.A. designed the study.

Funding

The granting body for this work is Swiss National Science Foundation, Grant PP00P1_150492 awarded to Tatjana Aue, Protocol number: 2015-10-000008. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

Under the Swiss guidelines of data protection (Ordinance HFV Art. 5), the MRI images generated and analyzed during the current study can be made available from the corresponding author on a case-by-case basis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Diener E, Heintzelman SJ, Kushlev K, Tay L, Wirtz D, Lutes LD, et al. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Can. Psychol. 2017;58(2):87. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Potter S, Drewelies J, Wagner J, Duezel S, Brose A, Demuth I, et al. Trajectories of multiple subjective well-being facets across old age: The role of health and personality. Psychol. Aging. 2020;35(6):894. doi: 10.1037/pag0000459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummins RA, Gullone E, Lau AL. A Model of Subjective Well-Being Homeostasis: The Role of Personality. Springer; 2002. pp. 7–46. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas, R. Exploring the Associations Between Personality and Subjective Well-Being. Handbook of Well-Being (DEF Publishers, 2018). https://www.nobascholar.com/chapters/3.

- 5.Weiss A, Bates TC, Luciano M. Happiness is a personal(ity) thing: The genetics of personality and well-being in a representative sample. Psychol. Sci. 2008;19(3):205–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018;2(4):253. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diener E, Lucas RE, Oishi S. Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra Psychol. 2018;4(1):15. doi: 10.1525/collabra.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chamberlain K, Zika S. Stability and change in subjective well-being over short time periods. Soc. Indic. Res. 1992;26(2):101–117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ugur ZB. Does having children bring life satisfaction in Europe? J. Happiness Stud. 2020;21(4):1385–1406. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahuvia A. If money doesn’t make us happy, why do we act as if it does? J. Econ. Psychol. 2008;29(4):491–507. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ryff CD, Essex MJ. The interpretation of life experience and well-being: The sample case of relocation. Psychol. Aging. 1992;7(4):507. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayton P, Pott A, Elwakili N. Affective forecasting: Why can't people predict their emotions? Think. Reason. 2007;13(1):62–80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert DT, Wilson TD. Miswanting: Some Problems in the Forecasting of Future Affective States. In: Forgas JP, editor. Thinking and Feeling: The Role of Affect in Social Cognition. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schkade DA, Kahneman D. Does living in California make people happy? A focusing illusion in judgments of life satisfaction. Psychol. Sci. 1998;9(5):340–346. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diener E, Lucas RE, Scollon CN. Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill: Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being. Springer; 2009. pp. 103–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Headey B. Subjective well-being: Revisions to dynamic equilibrium theory using national panel data and panel regression methods. Soc. Indic. Res. 2006;79(3):369–403. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huppert FA. The State of Wellbeing Science: Concepts, Measures, Interventions, and Policies. In: Cooper CL, editor. Wellbeing: A Complete Reference Guide. Wiley; 2014. pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veenhoven R. Happiness: Also Known as “Life Satisfaction” and “Subjective Well-Being”. Springer; 2012. pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coles E, Cheyne H, Daniel B. Early years interventions to improve child health and wellbeing: What works, for whom and in what circumstances? Protocol for a realist review. Syst. Rev. 2015;4(1):79. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daniels K, Watson D, Gedikli C. Well-being and the social environment of work: A systematic review of intervention studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14(8):918. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oishi S, Diener E. Goals, Culture, and Subjective Well-Being. Springer; 2009. pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz SH, Sortheix F. Values and Subjective Well-Being. In: Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L, editors. Handbook of Well-Being. Noba Scholar; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carrieri V. Social comparison and subjective well-being: Does the health of others matter? Bull. Econ. Res. 2012;64(1):31–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8586.2011.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener E, Fujita F. Social Comparisons and Subjective Well-Being. In: Buunk BP, Gibbons FX, Buunk A, editors. Health, Coping, and Well-Being: Perspectives from Social Comparison Theory. Psychology Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fujita F. The Frequency of Social Comparison and Its Relation to Subjective Well-Being. In: Eid M, Larsen RJ, editors. The Science of Subjective Well-Being. Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alarcon GM, Bowling NA, Khazon S. Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2013;54(7):821–827. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheier MF, Carver CS. Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update. Cogn. Ther. Res. 1992;16(2):201–228. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Optimism, Pessimism, and Psychological Well-Being. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. University of Michigan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant S, Langan-Fox J, Anglim J. The big five traits as predictors of subjective and psychological well-being. Psychol. Rep. 2009;105(1):205–231. doi: 10.2466/PR0.105.1.205-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gutiérrez JLG, Jiménez BM, Hernández EG, Pcn C. Personality and subjective well-being: Big five correlates and demographic variables. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005;38(7):1561–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haslam N, Whelan J, Bastian B. Big Five traits mediate associations between values and subjective well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009;46(1):40–42. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiota MN, Keltner D, John OP. Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006;1(2):61–71. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Markarian SA, Pickett SM, Deveson DF, Kanona BB. A model of BIS/BAS sensitivity, emotion regulation difficulties, and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in relation to sleep quality. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(1):281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauer S, Walach H, Kohls N. Gray’s behavioural inhibition system as a mediator of mindfulness towards well-being. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011;50(4):506–511. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taubitz LE, Pedersen WS, Larson CL. BAS Reward Responsiveness: A unique predictor of positive psychological functioning. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015;80:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Updegraff JA, Gable SL, Taylor SE. What makes experiences satisfying? The interaction of approach-avoidance motivations and emotions in well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2004;86(3):496. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.86.3.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brewer SK, Zahniser E, Conley CS. Longitudinal impacts of emotion regulation on emerging adults: Variable-and person-centered approaches. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2016;47:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu T, Zhang D, Wang J, Mistry R, Ran G, Wang X. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: A meta-analysis review. Psychol. Rep. 2014;114(2):341–362. doi: 10.2466/03.20.PR0.114k22w4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Penley JA, Tomaka J. Associations among the Big Five, emotional responses, and coping with acute stress. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002;32(7):1215–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali S, Alea N. Validating the emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ) in Trinidad. Behav Sci. 2018;1:1003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balzarotti S, John OP, Gross JJ. An Italian adaptation of the emotion regulation questionnaire. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010;26(1):61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gračanin A, Kardum I, Gross JJ. The Croatian version of the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Links with higher-and lower-level personality traits and mood. Int. J. Psychol. 2020;55(4):609–617. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gullone E, Taffe J. The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (ERQ–CA): A psychometric evaluation. Psychol. Assess. 2012;24(2):409. doi: 10.1037/a0025777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erdle S, Rushton JP. The general factor of personality, BIS–BAS, expectancies of reward and punishment, self-esteem, and positive and negative affect. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010;48(6):762–766. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rey L, Extremera N. Positive psychological characteristics and interpersonal forgiveness: Identifying the unique contribution of emotional intelligence abilities, Big Five traits, gratitude and optimism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2014;68:199–204. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuurmans-Stekhoven JB. Conviction, character and coping: Religiosity and personality are both uniquely associated with optimism and positive reappraising. Ment. Health Relig. Cult. 2018;21(8):763–779. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharpe JP, Martin NR, Roth KA. Optimism and the Big Five factors of personality: Beyond neuroticism and extraversion. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011;51(8):946–951. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soto CJ. Is happiness good for your personality? Concurrent and prospective relations of the big five with subjective well-being. J. Personal. 2015;83(1):45–55. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2003;85(2):348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merchán-Clavellino A, Alameda-Bailén JR, Zayas García A, Guil R. Mediating effect of trait emotional intelligence between the behavioral activation system (BAS)/behavioral inhibition system (BIS) and positive and negative affect. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:424. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tull MT, Gratz KL, Latzman RD, Kimbrel NA, Lejuez C. Reinforcement sensitivity theory and emotion regulation difficulties: A multimodal investigation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010;49(8):989–994. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buhle JT, Silvers JA, Wager TD, Lopez R, Onyemekwu C, Kober H, et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: A meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex. 2014;24(11):2981–2990. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dricu M, Kress L, Aue T. The Neurophysiological Basis of Optimism Bias. Cognitive Biases in Health and Psychiatric Disorders: Neurophysiological Foundations. Elsevier; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Privado J, Roman FJ, Saenz-Urturi C, Burgaleta M, Colom R. Gray and white matter correlates of the Big Five personality traits. Neuroscience. 2017;349:174–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu J, Kober H, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Pearlson GD, Potenza MN. White matter integrity and behavioral activation in healthy subjects. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2012;33(4):994–1002. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xu J, Potenza MN. White matter integrity and five-factor personality measures in healthy adults. Neuroimage. 2012;59(1):800–807. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.King ML. The neural correlates of well-being: A systematic review of the human neuroimaging and neuropsychological literature. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2019;19(4):779–796. doi: 10.3758/s13415-019-00720-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avinun R, Israel S, Knodt AR, Hariri AR. Little evidence for associations between the big five personality traits and variability in brain gray or white matter. Neuroimage. 2020;220:117092. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gerlach M, Farb B, Revelle W, Amaral LAN. A robust data-driven approach identifies four personality types across four large data sets. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018;2(10):735–742. doi: 10.1038/s41562-018-0419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kövi Z, Aluja A, Glicksohn J, Blanch A, Morizot J, Wang W, et al. Cross-country analysis of alternative five factor personality trait profiles. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2019;143:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerber A, Roth M, Herzberg PY. Personality types revisited—A literature-informed and data-driven approach to an integration of prototypical and dimensional constructs of personality description. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0244849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0244849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Udayar S, Urbanaviciute I, Massoudi K, Rossier J, Fajkowska M. The role of personality profiles in the longitudinal relationship between work-related well-being and life satisfaction among working adults in Switzerland. Eur. J. Personal. 2020;34(1):77–92. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Y, He L, Zhuang K, Wu X, Sun J, Wei D, et al. Linking personality types to depressive symptoms: A prospective typology based on neuroticism, extraversion and conscientiousness. Neuropsychologia. 2020;136:107289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2019.107289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Madsen KS, Jernigan TL, Vestergaard M, Mortensen EL, Baaré WF. Neuroticism is linked to microstructural left-right asymmetry of fronto-limbic fibre tracts in adolescents with opposite effects in boys and girls. Neuropsychologia. 2018;114:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lewis GJ, Cox SR, Booth T, Muñoz Maniega S, Royle NA, Valdés Hernández M, et al. Trait conscientiousness and the personality meta-trait stability are associated with regional white matter microstructure. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2016;11(8):1255–1261. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsw037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bjørnebekk A, Fjell AM, Walhovd KB, Grydeland H, Torgersen S, Westlye LT. Neuronal correlates of the five factor model (FFM) of human personality: Multimodal imaging in a large healthy sample. Neuroimage. 2013;65:194–208. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moghaddam HS, Mehrabinejad M-M, Mohebi F, Hajighadery A, Maroufi SF, Rahimi R, et al. Microstructural white matter alterations and personality traits: A diffusion MRI study. J. Res. Personal. 2020;88:104010. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Montag C, Reuter M, Weber B, Markett S, Schoene-Bake J-C. Individual differences in trait anxiety are associated with white matter tract integrity in the left temporal lobe in healthy males but not females. Neuroscience. 2012;217:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leshem R, Paoletti P, Piervincenzi C, Carducci F, Mallio C, Errante Y, et al. Inward versus reward: White matter pathways in extraversion. Personal. Neurosci. 2019;2:E6. doi: 10.1017/pen.2019.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu W-Y, Weber B, Reuter M, Markett S, Chu W-C, Montag C. The Big Five of Personality and structural imaging revisited: A VBM–DARTEL study. NeuroReport. 2013;24(7):375–380. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328360dad7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boekel W, Wagenmakers E-J, Belay L, Verhagen J, Brown S, Forstmann BU. A purely confirmatory replication study of structural brain-behavior correlations. Cortex. 2015;66:115–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Eden AS, Schreiber J, Anwander A, Keuper K, Laeger I, Zwanzger P, et al. Emotion regulation and trait anxiety are predicted by the microstructure of fibers between amygdala and prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2015;35(15):6020–6027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3659-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pisner DA, Smith R, Alkozei A, Klimova A, Killgore WD. Highways of the emotional intellect: White matter microstructural correlates of an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence. Soc. Neurosci. 2017;12(3):253–267. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1176600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.d'Arbeloff TC, Kim MJ, Knodt AR, Radtke SR, Brigidi BD, Hariri AR. Microstructural integrity of a pathway connecting the prefrontal cortex and amygdala moderates the association between cognitive reappraisal and negative emotions. Emotion. 2018;18(6):912. doi: 10.1037/emo0000447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zuurbier LA, Nikolova YS, Åhs F, Hariri AR. Uncinate fasciculus fractional anisotropy correlates with typical use of reappraisal in women but not men. Emotion. 2013;13(3):385. doi: 10.1037/a0031163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smith A. Cognitive empathy and emotional empathy in human behavior and evolution. Psychol. Record. 2006;56(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Beaulieu C. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system—A technical review. NMR Biomed.: Int. J. Devoted Dev. Appl. Magn. Resonance In Vivo. 2002;15(7–8):435–455. doi: 10.1002/nbm.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sousa SS, Amaro E, Crego A, Gonçalves ÓF, Sampaio A. Developmental trajectory of the prefrontal cortex: A systematic review of diffusion tensor imaging studies. Brain Imaging Behav. 2018;12(4):1197–1210. doi: 10.1007/s11682-017-9761-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rotenberg VS. Right hemisphere insufficiency and illness in the context of search activity concept. Dyn. Psychiatry. 1995;150(151):54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dolcos F, Rice HJ, Cabeza R. Hemispheric asymmetry and aging: Right hemisphere decline or asymmetry reduction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2002;26(7):819–825. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rotenberg VS. The peculiarity of the right-hemisphere function in depression: Solving the paradoxes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2004;28(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/S0278-5846(03)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rotenberg VS, Weinberg I. Human memory, cerebral hemispheres, and the limbic system: A new approach. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1999;125(1):45–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rotenberg VS. An integrative psychophysiological approach to brain hemisphere functions in schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1994;18(4):487–495. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kohn B. Right-hemisphere speech representation and comprehension of syntax after left cerebral injury. Brain Lang. 1980;9(2):350–361. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(80)90154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kane J. Poetry as right-hemispheric language. J. Conscious. Stud. 2004;11(5–6):21–59. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lindell AK. In your right mind: Right hemisphere contributions to language processing and production. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2006;16(3):131–148. doi: 10.1007/s11065-006-9011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuhl J, Quirin M, Koole SL. Being someone: The integrated self as a neuropsychological system. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2015;9(3):115–132. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Koole SL, Schlinkert C, Maldei T, Baumann N. Becoming who you are: An integrative review of self-determination theory and personality systems interactions theory. J. Personal. 2019;87(1):15–36. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Quirin M, Bode RC, Kuhl J. Recovering from negative events by boosting implicit positive affect. Cogn. Emot. 2011;25(3):559–570. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.536418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Quirin M, Fröhlich S, Kuhl J. Implicit self and the right hemisphere: Increasing implicit self-esteem and implicit positive affect by left hand contractions. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018;48(1):4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kuhl J. The volitional basis of Personality Systems Interaction theory: Applications in learning and treatment contexts. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2000;33(7–8):665–703. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mezulis AH, Abramson LY, Hyde JS, Hankin BL. Is there a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychol. Bull. 2004;130(5):711. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schore AN. The experience-dependent maturation of a regulatory system in the orbital prefrontal cortex and the origin of developmental psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 1996;8(1):59–87. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weinberg I. The prisoners of despair: Right hemisphere deficiency and suicide. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2000;24(8):799–815. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Liao Y, Huang X, Wu Q, Yang C, Kuang W, Du M, et al. Is depression a disconnection syndrome? Meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies in patients with MDD. J. Psychiatry Neurosci.: JPN. 2013;38(1):49. doi: 10.1503/jpn.110180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Klöppel S, Bäumer T, Kroeger J, Koch MA, Büchel C, Münchau A, et al. The cortical motor threshold reflects microstructural properties of cerebral white matter. Neuroimage. 2008;40(4):1782–1791. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lepley AS, Ly MT, Grooms DR, Kinsella-Shaw JM, Lepley LK. Corticospinal tract structure and excitability in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A DTI and TMS study. NeuroImage: Clin. 2020;25:102157. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gupta N, Aron AR. Urges for food and money spill over into motor system excitability before action is taken. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2011;33(1):183–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07510.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Klein P-A, Olivier E, Duque J. Influence of reward on corticospinal excitability during movement preparation. J. Neurosci. 2012;32(50):18124–18136. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1701-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mooshagian E, Keisler A, Zimmermann T, Schweickert JM, Wassermann EM. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by reward depends on task framing. Neuropsychologia. 2015;68:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bestmann S, Harrison LM, Blankenburg F, Mars RB, Haggard P, Friston KJ, et al. Influence of uncertainty and surprise on human corticospinal excitability during preparation for action. Curr. Biol. 2008;18(10):775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Aspinwall LG, Richter L, Hoffman RR., III . Understanding How Optimism Works: An Examination of Optimists' Adaptive Moderation of Belief and Behavior. In: Chang EC, editor. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. University of Michigan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Carver CS, Scheier MF. Dispositional optimism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2014;18(6):293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nakajima R, Kinoshita M, Miyashita K, Okita H, Genda R, Yahata T, et al. Damage of the right dorsal superior longitudinal fascicle by awake surgery for glioma causes persistent visuospatial dysfunction. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nakajima R, Kinoshita M, Shinohara H, Nakada M. The superior longitudinal fascicle: Reconsidering the fronto-parietal neural network based on anatomy and function. Brain Imaging Behav. 2019;14(6):2817–2830. doi: 10.1007/s11682-019-00187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wang X, Pathak S, Stefaneanu L, Yeh F-C, Li S, Fernandez-Miranda JC. Subcomponents and connectivity of the superior longitudinal fasciculus in the human brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 2016;221(4):2075–2092. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Klarborg B, Skak Madsen K, Vestergaard M, Skimminge A, Jernigan TL, Baaré WF. Sustained attention is associated with right superior longitudinal fasciculus and superior parietal white matter microstructure in children. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2013;34(12):3216–3232. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Cortese S, Imperati D, Zhou J, Proal E, Klein RG, Mannuzza S, et al. White matter alterations at 33-year follow-up in adults with childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiat. 2013;74(8):591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chiang H-L, Chen Y-J, Lo Y-C, Tseng W-YI, Gau SS-F. Altered white matter tract property related to impaired focused attention, sustained attention, cognitive impulsivity and vigilance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Psychiatry Neurosci.: JPN. 2015;40(5):325. doi: 10.1503/jpn.140106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sudre G, Choudhuri S, Szekely E, Bonner T, Goduni E, Sharp W, et al. Estimating the heritability of structural and functional brain connectivity in families affected by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(1):76–84. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dong G, Li H, Potenza MN. Short-term internet-search training is associated with increased fractional anisotropy in the superior longitudinal fasciculus in the parietal lobe. Front. Neurosci. 2017;11:372. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Kress L, Bristle M, Aue T. Seeing through rose-colored glasses: How optimistic expectancies guide visual attention. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0193311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Aue T, Dricu M, Singh L, Moser DA, Raviteja K. Enhanced sensitivity to optimistic cues is manifested in brain structure: A voxel-based morphometry study. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2021;16(11):1170–1181. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsab075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Singh L, Schüpbach L, Moser DA, Wiest R, Hermans EJ, Aue T. The effect of optimistic expectancies on attention bias: Neural and behavioral correlates. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61440-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Aue T, Nusbaum HC, Cacioppo JT. Neural correlates of wishful thinking. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2012;7(8):991–1000. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsr081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kress L, Aue T. The link between optimism bias and attention bias: A neurocognitive perspective. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017;80:688–702. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Braddick O, Atkinson J, Akshoomoff N, Newman E, Curley LB, Gonzalez MR, et al. Individual differences in children’s global motion sensitivity correlate with TBSS-based measures of the superior longitudinal fasciculus. Vis. Res. 2017;141:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2016.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kress L, Aue T. Learning to look at the bright side of life: Attention bias modification training enhances optimism bias. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2019;13:222. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2019.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.O’Reilly JX, Croxson PL, Jbabdi S, Sallet J, Noonan MP, Mars RB, et al. Causal effect of disconnection lesions on interhemispheric functional connectivity in rhesus monkeys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013;110(34):13982–13987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305062110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Damoiseaux JS, Greicius MD. Greater than the sum of its parts: A review of studies combining structural connectivity and resting-state functional connectivity. Brain Struct. Funct. 2009;213(6):525–533. doi: 10.1007/s00429-009-0208-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Honey CJ, Sporns O, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Thiran J-P, Meuli R, et al. Predicting human resting-state functional connectivity from structural connectivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009;106(6):2035–2040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811168106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alves PN, Foulon C, Karolis V, Bzdok D, Margulies DS, Volle E, et al. An improved neuroanatomical model of the default-mode network reconciles previous neuroimaging and neuropathological findings. Commun. Biol. 2019;2(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.van den Heuvel M, Mandl R, Luigjes J, Pol HH. Microstructural organization of the cingulum tract and the level of default mode functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. 2008;28(43):10844–10851. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2964-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gordon EM, Lee PS, Maisog JM, Foss-Feig J, Billington ME, VanMeter J, et al. Strength of default mode resting-state connectivity relates to white matter integrity in children. Dev. Sci. 2011;14(4):738–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.01020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Vidal-Piñeiro D, Valls-Pedret C, Fernández-Cabello S, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Sala-Llonch R, Solana E, et al. Decreased default mode network connectivity correlates with age-associated structural and cognitive changes. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:256. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Andrews-Hanna JR, Smallwood J, Spreng RN. The default network and self-generated thought: Component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014;1316(1):29. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Flagan T, Beer JS. Three ways in which midline regions contribute to self-evaluation. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013;7:450. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schacter DL, Addis DR, Buckner RL. Episodic simulation of future events. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1124(1):39–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Xu X, Yuan H, Lei X. Activation and connectivity within the default mode network contribute independently to future-oriented thought. Sci. Rep. 2016;6(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep21001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schacter DL, Benoit RG, Szpunar KK. Episodic future thinking: Mechanisms and functions. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017;17:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Rose JP, Jasper JD, Corser R. Interhemispheric interaction and egocentrism: The role of handedness in social comparative judgement. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2012;51(1):111–129. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rose JP, Nagel B. Relation between comparative risk, absolute risk, and worry: The role of handedness strength. J. Health Psychol. 2013;18(7):866–874. doi: 10.1177/1359105312456325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lee Niebauer C, Christman S, Reid S, Garvey K. Interhemispheric interaction and beliefs on our origin: Degree of handedness predicts beliefs in creationism versus evolution. Laterality: Asymmetries Body Brain Cogn. 2004;9(4):433–447. doi: 10.1080/13576500342000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Lee Niebauer C, Aselage J, Schutte C. Hemispheric interaction and consciousness: Degree of handedness predicts the intensity of a sensory illusion. Laterality: Asymmetries Body Brain Cogn. 2002;7(1):85–96. doi: 10.1080/13576500143000159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bubb EJ, Metzler-Baddeley C, Aggleton JP. The cingulum bundle: Anatomy, function, and dysfunction. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018;92:104–127. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Wu Y, Sun D, Wang Y, Wang Y, Ou S. Segmentation of the cingulum bundle in the human brain: A new perspective based on DSI tractography and fiber dissection study. Front. Neuroanat. 2016;10:84. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Wright NF, Vann SD, Erichsen JT, O'Mara SM, Aggleton JP. Segregation of parallel inputs to the anteromedial and anteroventral thalamic nuclei of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013;521(13):2966–2986. doi: 10.1002/cne.23325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Grodd W, Kumar VJ, Schüz A, Lindig T, Scheffler K. The anterior and medial thalamic nuclei and the human limbic system: Tracing the structural connectivity using diffusion-weighted imaging. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–25. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-67770-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Jakabek D, Power BD, Macfarlane MD, Walterfang M, Velakoulis D, Van Westen D, et al. Regional structural hypo-and hyperconnectivity of frontal–striatal and frontal–thalamic pathways in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2018;39(10):4083–4093. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Blair KS, Otero M, Teng C, Jacobs M, Odenheimer S, Pine DS, et al. Dissociable roles of ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) and rostral anterior cingulate cortex (rACC) in value representation and optimistic bias. Neuroimage. 2013;78:103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Dricu M, Schüpbach L, Bristle M, Wiest R, Moser DA, Aue T. Group membership dictates the neural correlates of social optimism biases. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–17. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58121-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Moser DA, Dricu M, Wiest R, Schüpbach L, Aue T. Social optimism biases are associated with cortical thickness. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2020;15(7):745–754. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450(7166):102. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Moser DA, Dricu M, Kotikalapudi R, Doucet GE, Aue T. Reduced network integration in default mode and executive networks is associated with social and personal optimism biases. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2021;42:2893–2906. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Van Reekum CM, Urry HL, Johnstone T, Thurow ME, Frye CJ, Jackson CA, et al. Individual differences in amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex activity are associated with evaluation speed and psychological well-being. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2007;19(2):237–248. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2007.19.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1994;67(2):319. [Google Scholar]

- 147.Depue RA, Collins PF. Neurobiology of the structure of personality: Dopamine, facilitation of incentive motivation, and extraversion. Behav. Brain Sci. 1999;22(3):491–517. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x99002046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2001;30(4):669–689. [Google Scholar]

- 149.aan het Rot M, Moskowitz D, Young SN. Impulsive behaviour in interpersonal encounters: Associations with quarrelsomeness and agreeableness. Br. J. Psychol. 2015;106(1):152–161. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bakhshani N-M. Impulsivity: A predisposition toward risky behaviors. Int. J. High Risk Behav. Addict. 2014;3(2):e20428. doi: 10.5812/ijhrba.20428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Barrat E. Impulsiveness and Aggression. Violence and Mental Disorder. Development in Risk Assessment. University of Chicago; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 152.Chudasama Y. Animal models of prefrontal-executive function. Behav. Neurosci. 2011;125(3):327. doi: 10.1037/a0023766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;51(6):768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Goldwaser EL, Du X, Adhikari BM, Kvarta M, Chiappelli J, Hare S, et al. Role of white matter microstructure in impulsive behavior. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2022 doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.21070167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Kim I-S, Kim Y-T, Song H-J, Lee J-J, Kwon D-H, Lee HJ, et al. Reduced corpus callosum white matter microstructural integrity revealed by diffusion tensor eigenvalues in abstinent methamphetamine addicts. Neurotoxicology. 2009;30(2):209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Yip SW, Morie KP, Xu J, Constable RT, Malison RT, Carroll KM, et al. Shared microstructural features of behavioral and substance addictions revealed in areas of crossing fibers. Biol. Psychiatry: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2017;2(2):188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Arnone D, Abou-Saleh MT, Barrick TR. Diffusion tensor imaging of the corpus callosum in addiction. Neuropsychobiology. 2006;54(2):107–113. doi: 10.1159/000096992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]