Abstract

Compounds in a series of cholic acid derivatives, designed to mimic the activities of polymyxin B and its derivatives, act as both potent antibiotics and effective permeabilizers of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. Some of these compounds rival polymyxin B in antibacterial activity against gram-negative bacteria and are also very active against gram-positive organisms. Other compounds interact synergistically with hydrophobic antibiotics to inhibit bacterial growth.

We have developed a series of cholic acid derivatives that includes compounds that act as potent antibiotics against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. In addition, compounds within this series effectively permeabilize the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria, thereby sensitizing the bacteria to hydrophobic antibiotics. These cholic acid derivatives were developed (3, 4) to mimic the bactericidal behavior of polymyxin B (PMB) and the outer membrane-permeabilizing properties of truncated versions of PMB, such as deacyl PMB (10) and PMB nonapeptide (9). The cholic acid derivatives contain elements conserved among the polymyxin family of antibiotics, that is, a cluster of three amine groups and a hydrophobic chain. Cholic acid derivatives containing these two elements are potent antibiotics, while those lacking the hydrophobic chain effectively sensitize gram-negative bacteria to erythromycin, novobiocin, and rifampin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibacterial compounds.

The syntheses of compounds 1 to 8 have been reported previously (3, 4). Erythromycin was obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co. (Milwaukee, Wis.), and rifampin and novobiocin were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.) and were used as received.

Microorganisms.

Reference strains were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, Md.) or Difco Laboratories (Detroit, Mich.). The following specific ATCC strains were used: Escherichia coli 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae 13883, Pseudomonas aeruginosa 27853, Salmonella typhimurium 14028, Enterococcus faecalis 29212, Staphylococcus aureus 25923, Streptococcus pyogenes 19615, and Candida albicans 90028. Bacterial strains were maintained on Mueller-Hinton agar plates (S. pyogenes and E. faecalis were maintained on Mueller-Hinton agar supplemented with 5% sheep blood), and C. albicans was maintained on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates.

Determination of MICs and MBCs.

MICs and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBCs) for bacteria were determined by a broth macrodilution method with Mueller-Hinton broth (6, 7) (Mueller-Hinton broth for S. pyogenes and E. faecalis was supplemented with lysed horse blood [6]). Sabouraud dextrose broth was used with C. albicans. Each compound was initially screened to determine its MIC range. Subsequently, concentration increments of the cholic acid derivatives were varied by the following criteria. For MICs above 10 μg/ml, increments of 5 μg/ml were used; for MICs between 1 and 10 μg/ml, increments of 1 μg/ml were used; and for MICs less than 1 μg/ml, increments of 0.1 μg/ml were used. This procedure was used in an effort to observe small differences in MICs and MBCs. Each MIC and MBC was measured a minimum of 10 times, with results varying less than 10%. The averaged results are reported.

Determination of MHCs.

The cholic acid derivatives were dissolved in 0.85% saline, and the solution was diluted with Dulbecco phosphate-suffered saline and added to a 1% suspension of sheep erythrocytes. The samples were incubated for 24 h and centrifuged. The minimum hemolytic concentrations (MHCs) were determined by measuring the absorbance of the supernatant at 540 nm. The MHC of each compound was measured a minimum of 10 times, with results varying by less than 10%. The averaged results are reported.

Determination of FICs.

Fractional inhibition concentrations (FICs) (1) were calculated as follows: FIC = [A]/MICA + [B]/MICB, where MICA and MICB are the MICs of compounds A and B, respectively, and [A] and [B] are the concentrations at which compounds A and B, in combination, inhibit bacterial growth. Synergism is defined by a FIC of <0.5. Synergy tests with erythromycin, novobiocin, and rifampin were performed by a broth macrodilution method. A concentration of 0.5 μg of rifampin/ml was used with E. coli and K. pneumoniae, and a concentration of 3 μg of erythromycin/ml was used with P. aeruginosa. In all other experiments, the antibiotics were used at 1 μg/ml. Each FIC was measured a minimum of 10 times, with results varying by less than 10%. The averaged results are reported.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

MIC and MBC data for the cholic acid derivatives with representative strains of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria are shown in Table 1. Also included in the table are MICs for C. albicans. For comparison purposes, the MICs of PMB for various organisms were also measured and are presented in Table 1. The cholic acid derivatives display a range of activities, some with submicrogram-per-milliliter MICs. In addition, for many organisms, MICs and MBCs are very similar, especially with the most active compounds.

TABLE 1.

MICs and MBCs of cholic acid derivatives 1 to 8

| Organism | MIC (MBC) (μg/ml)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound

|

PMB | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Gram-negative rods | |||||||||

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 22 (22) | 5.1 (6.8) | 1.4 (3.8) | 80 (90) | 36 (40) | 6.6 (7.4) | 3.0 (3.0) | 0.31 (0.37) | 1.8 (1.8) |

| K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 24 (>36) | 14 (17) | 3.0 (6.7) | >100 (>100) | 47 (50) | 23 (27) | 2.6 (5.8) | 0.84 (3.0) | 5.3 (6.8) |

| P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | 26 (38) | 11 (>17) | 5.9 (9.9) | 85 (97) | 21 (36) | 4.6 (6.4) | 2.0 (3.2) | 2.0 (2.9) | 0.20 (3.9) |

| S. typhimurium ATCC 14028 | 21 (>25) | 13 (16) | 2.2 (3.8) | >100 (>100) | 43 (>47) | 86 (90) | 2.6 (6.7) | 0.81 (1.8) | NMa |

| Gram-positive cocci | |||||||||

| E. faecalis ATCC 29212 | 4.9 (50) | 3.4 (19) | 2.2 (16) | 12 (>100) | 3.3 (19) | 3.1 (4.7) | 3.1 (5.5) | 3.0 (5.8) | 40 (>100) |

| S. aureus ATCC 25923 | 3.1 (5.7) | 1.0 (4.7) | 0.6 (3.2) | 8.6 (54) | 2.0 (9.2) | 0.55 (4.2) | 0.40 (2.0) | 0.59 (1.4) | 26 (>100) |

| S. pyogenes ATCC 19615 | 3.0 (4.4) | 2.0 (2.3) | 2.0 (2.1) | 18 (37) | 4.2 (5.8) | 2.4 (3.0) | 2.3 (2.9) | 3.5 (3.5) | 19 (16.3) |

| Fungus | |||||||||

| C. albicans ATCC 90028 | 49 (>50) | 30 (42) | 11 (50) | 75 (92) | 14 (29) | 41 (45) | 31 (45) | 53 (76) | NM |

NM, not measured.

The nature of the group extending from the steroid nucleus at C-17 greatly influences the activity of the compounds with gram-negative bacteria. Compounds with a hydrophobic chain (e.g., 7 and 8) are potent antibiotics, while those with smaller chains extending from C-17 (e.g., 4 and 5) give higher MICs and MBCs. We have suggested (4) that the role of the hydrophobic chain is to facilitate “self-promoted transport” (2) of the compounds through the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria, allowing access to the cytoplasmic membrane.

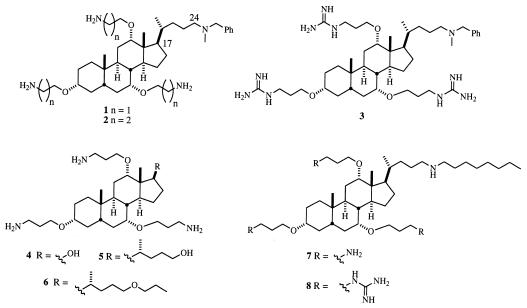

Compared to trends observed with gram-negative bacteria, the role of a hydrophobic chain in the activity of the cholic acid derivatives is less pronounced with gram-positive organisms because self-promoted transport is unnecessary. With a few exceptions (most notably compound 4), the cholic acid derivatives shown in Fig. 1 have similar activities against gram-positive bacteria.

FIG. 1.

Structures of cholic acid derivatives 1 to 8.

The cholic acid derivatives are much less active against C. albicans than against bacteria. Under physiological conditions the cholic acid derivatives bear multiple positive charges and likely associate strongly with the negatively charged membranes of bacteria. The membranes of eukaryotic cells generally bear less of a negative charge than those of prokaryotes (5). Consequently, it is not unexpected that the cholic acid derivatives demonstrate decreased activity against C. albicans.

The MHCs (in micrograms per milliliter) of the compounds shown in Fig. 1 are as follows: compound 1, 78; 2, 58; 3, 26; 4, >100; 5, 100; 6, 5.9; 7, 29; and 8, 9.0. These results suggest that some of these compounds are well tolerated by eukaryotic cells.

The cholic acid derivatives lacking a hydrophobic chain were designed to increase the permeability of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. Some of the compounds display potent synergism with hydrophobic antibiotics that ineffectively traverse the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria (Table 2). We determined the FICs of compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 with erythromycin, novobiocin, and rifampin (Tables 3 to 5). Many of the FICs shown in Tables 3 to 5 are comparable to those reported for PMB derivatives (8). Compounds 3, 7, and 8 are potent antibiotics alone, and therefore the FICs of these cholic acid derivatives were not determined.

TABLE 2.

MICs of erythromycin, novobiocin, and rifampin alone

| Drug | MIC (μg/ml) for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 | S. typhimurium ATCC 14028 | |

| Erythromycin | 30 | 33 | >100 | 61 |

| Novobiocin | 41 | 75 | >100 | >100 |

| Rifampin | 7.6 | 19 | 26 | 21 |

TABLE 3.

Concentrations of compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 required to lower the MIC of erythromycin and FICs of combinations

| Compound | Concn and FIC fora:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli ATCC 25922 [1.0]

|

K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 [1.0]

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 [3.0]

|

S. typhimurium ATCC 14028 [1.0]

|

|||||

| Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC3.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | |

| 1 | 2.5 | 0.15 | 1.0 | 0.072 | 6.6 | <0.29 | 3.6 | 0.19 |

| 2 | 0.23 | 0.078 | 0.25 | 0.048 | 2.4 | <0.25 | 2.0 | 0.17 |

| 4 | 3.2 | 0.073 | 3.6 | <0.066 | 16 | <0.22 | 7.1 | <0.088 |

| 5 | 1.5 | 0.074 | 0.21 | 0.035 | 2.1 | <0.13 | 0.87 | 0.037 |

| 6 | 0.59 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.035 | 1.0 | <0.24 | 0.20 | 0.019 |

All concentrations are in micrograms per milliliter. Concentrations of erythromycin are indicated in brackets.

TABLE 5.

Concentrations of compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 required to lower the MIC of rifampin and FICs of combinations

| Compound | Concn and FIC fora:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli ATCC 25922 [0.50]

|

K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883 [0.50]

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853 [1.0]

|

S. typhimurium ATCC 14028 [1.0]

|

|||||

| Concn | FIC (IC0.5) | Concn | FIC (IC0.5) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | |

| 1 | 0.74 | 0.099 | 0.40 | 0.043 | 1.5 | 0.096 | 0.84 | 0.089 |

| 2 | 0.80 | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.035 | 0.50 | 0.086 | 0.39 | 0.079 |

| 4 | 4.2 | 0.12 | 1.8 | 0.044 | 11 | 0.17 | 1.4 | 0.064 |

| 5 | 0.70 | 0.085 | 0.16 | 0.030 | 0.84 | 0.083 | 0.55 | 0.063 |

| 6 | 0.81 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.031 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.051 |

All concentrations are in micrograms per milliliter. Concentrations of rifampin are indicated in brackets.

The cholic acid derivatives display activities similar to those of PMB and its derivatives against gram-negative bacteria. That is, compounds containing a hydrophobic chain (PMB, 7, and 8) act as potent antibiotics and compounds lacking the hydrophobic side chain (deacyl PMB, PMB nonapeptide, 4, and 5) are effective permeabilizers of the outer membranes of gram-negative bacteria. To the extent that the cholic acid derivatives mimic the behavior of PMB, the compounds may indicate the functionality necessary for the activity of PMB. This functionality can be distilled down to an array of amines (or other basic groups, such as guanidines) oriented on one face of a hydrophobic scaffolding, with an attached acyl or alkyl chain facilitating self-promoted transport through the outer membrane.

Permeabilizers, such as compounds 4 and 5, may be useful in synergistic combination with antibiotics, such as erythromycin or rifampin, in inhibiting the growth of gram-negative bacteria, whereas alone the antibiotics are ineffective. Derivatives with a hydrophobic side chain, such as compounds 6, 7, and 8, alone display low MICs with gram-negative and gram-positive strains of bacteria. However, their systemic use may be limited by their hemolytic activity. Nevertheless, due to their potent activity and simplicity, they may be well suited for topical applications.

TABLE 4.

Concentrations of compounds 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 required to lower the MIC of novobiocin and FICs of combinations

| Compound | Concn and FIC fora:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E. coli ATCC 25922

|

K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883

|

P. aeruginosa ATCC 27853

|

S. typhimurium ATCC 14028

|

|||||

| Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | Concn | FIC (IC1.0) | |

| 1 | 0.35 | 0.041 | 4.7 | 0.21 | 3.9 | <0.16 | 4.4 | <0.22 |

| 2 | 0.33 | 0.089 | 0.49 | 0.048 | 2.9 | <0.27 | 4.5 | <0.36 |

| 4 | 4.7 | 0.084 | 8.9 | 0.10 | 30 | <0.36 | 8.4 | <0.094 |

| 5 | 0.30 | 0.033 | 0.73 | 0.029 | 5.3 | <0.26 | 1.8 | <0.052 |

| 6 | 0.40 | 0.085 | 0.19 | 0.022 | 0.72 | <0.17 | 0.39 | <0.015 |

All concentrations are in micrograms per milliliter. The concentration of novobiocin used was 1.0 μg/ml.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM 54619) is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eliopoulos G M, Moellering R C., Jr . Antimicrobial combinations. In: Lorian V, editor. Antibiotics in laboratory medicine. Baltimore, Md: Williams and Wilkins Co.; 1991. pp. 432–492. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hancock R E W. Alterations in outer membrane permeability. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:237–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li C, Peters A S, Meredith E L, Allman G W, Savage P B. Design and synthesis of potent sensitizers of Gram-negative bacteria based on a cholic acid scaffolding. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:2961–2962. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li C, Budge L P, Driscoll C D, Willardson B M, Allman G W, Savage P B. Incremental conversion of outer-membrane permeabilizers into potent antibiotics for Gram-negative bacteria. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:931–940. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Molecular basis for membrane selectivity of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3423–3429. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. 1997. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically, 4th ed. Approved standard M7-A4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard M27-A. Villanova, Pa: National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaara M. Agents that increase the permeability of the outer membrane. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:395–411. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.395-411.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaara M, Vaara T. Sensitization of Gram-negative bacteria to antibiotics and complement by nontoxic oligopeptide. Nature. 1983;303:526–528. doi: 10.1038/303526a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viljanen P, Matsunaga H, Kimura Y, Vaara M. The outer membrane permeability-increasing action of deacylpolymyxins. J Antibiot. 1991;44:517–523. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]