Abstract

Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates 871 and 873 were isolated at Hacettepe University Hospital in Ankara and were highly resistant to ceftazidime (MIC, 128 μg/ml). Each produced three β-lactamases, with pIs of 5.3, 6.1, and 7.9. The β-lactamase with a pI of 5.3 was previously shown to be PER-1 enzyme. The antibiograms of the isolates were not entirely explained by production of PER-1 enzyme, insofar as ceftazidime resistance was incompletely reversed by clavulanate. The enzymes with pIs of 6.1 and 7.9 were therefore investigated. The enzyme with a pI of 6.1 proved to be a novel mutant of OXA-10, which we designated OXA-17, and had asparagine changed to serine at position 73 of the protein. When cloned into Escherichia coli XL1-blue, OXA-17 enzyme conferred greater resistance to cefotaxime, latamoxef, and cefepime than did OXA-10, but it had only a marginal (two- to fourfold) effect on the MIC of ceftazidime. This behavior contrasted with that of previous OXA-10 mutants, specifically OXA-11, -14, and -16, which predominately compromise ceftazidime. Extracted OXA-17 enzyme had relatively greater activity than OXA-10 against oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefotaxime but, in terms of kcat/Km, it had lower catalytic efficiency against most β-lactams. The enzyme with a pI of 7.9 was shown by gene sequencing to be OXA-2.

The most frequent mechanisms of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa are derepression of the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase and increased efflux (1). Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) are a greater problem in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (19). Only one TEM-related ESBL has so far been described from P. aeruginosa (24); nevertheless, several other potent plasmid-mediated β-lactamases have been described from the species. These include the IMP-1 zinc β-lactamase (34), PER-1, which is a class A ESBL (25) that is widespread in Turkey (5, 26, 31); and several extended-spectrum mutants of class D β-lactamases (4, 6, 10). The last group includes the OXA-11, -14, and -16 derivatives of OXA-10 β-lactamase (4, 8, 10), the OXA-15 derivative of OXA-2 enzyme (6), and the OXA-18 enzyme, which is closely related to the OXA-12 and AmpS chromosomal enzymes of Aeromonas sobria (27, 29, 33).

In the present study we describe a further ESBL mutant of the OXA-10 enzyme, obtained from two P. aeruginosa isolates collected in Turkey.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

P. aeruginosa isolates 871 and 873 were isolated in February and March 1992, respectively, from patients treated for burns at Hacettepe University Hospital, Ankara, Turkey. They were believed to be isolates of the same strain, since they had identical enzyme DNA restriction patterns (5). Previous work showed that they produced PER-1 β-lactamase together with β-lactamases that had pIs of 6.1 and ≥7.7 and that they carried a gene which hybridized with a probe to blaOXA-10 (5).

Both isolates were broadly resistant to β-lactams (Table 1), and ceftazidime resistance was less completely reversed by clavulanate (4 μg/ml) than in strains with PER-1 β-lactamase alone (5). P. aeruginosa PU21 ilv leu Strr Rifr (12) and a ciprofloxacin-resistant derivative, obtained as described previously (7, 9), were used as recipients in transconjugation. Escherichia coli XL1-blue MRF′ was used as a recipient in transformation experiments with the pBC SK+ cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). P. aeruginosa PU21 transconjugants with plasmids pMG40 (encoding OXA-2 β-lactamase), pMLH51 (OXA-10) (10, 20), pMLH52 (OXA-11) (10), pMLH53 (OXA-14) (4), and pMLH57 (PER-1) (7) were used as producers of reference β-lactamases. An E. coli K-12 transconjugant with plasmid R46 was used as a further reference producer of OXA-2 β-lactamase (2). E. coli NCTC 50192, with plasmids of 154, 66, 38, and 7 kb, was used in plasmid sizing (32).

TABLE 1.

MICs of β-lactams for P. aeruginosa isolates 871 and 873

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)a

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pip | Pip-Clav | Pip-Taz | Cb | Cb-Clav | Cb-Taz | Caz | Caz-Clav | Caz-Taz | Ctx | Ctr | Csl | Cpm | Cpr | Cpz | Mox | Azt | Mem | Imp | |

| 871 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 1,024 | 256 | 512 | 128 | 16 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 64 | 128 | 32 | 128 | 0.5 | 2 |

| 873 | 64 | 32 | 64 | >512 | 512 | >512 | 128 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 128 | 64 | 16 | 32 | 128 | 64 | 64 | 0.25 | 4 |

| PU21(pMLH57)/PER-1b | 8 | 4 | 8 | 512 | 128 | 256 | 256 | 4 | 128 | 64 | 128 | 128 | 32 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 128 | 1 | 2 |

| PU21 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 64 | 64 | 64 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 16 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

Azt, aztreonam; Cb, carbenicillin; Clav, clavulanate at 4 μg/ml; Cpm, cefepime; Cpr, Cefpirome; Cpz, cefoperazone; Csl, cefsulodin; Ctx, cefotaxime; Caz, ceftazidime; Ctr, ceftriaxone; Imp, imipenem; Mem, meropenem; Mox, moxalactam (latamoxef); Pip, piperacillin; Taz, tazobactam at 4 μg/ml.

P. aeruginosa PU21 with pMLH57 plasmid coding PER-1 β-lactamase.

Antibiotics and susceptibility tests.

MICs were determined on DST agar (Unipath, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom) with inocula of 104 CFU per spot. Antibiotics were supplied by the following manufacturers: aztreonam and cefepime, Bristol Myers Squibb, Syracuse, N.Y.; cefsulodin, Novartis, Basel, Switzerland; ceftazidime, Glaxo-Wellcome, Stevenage, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom; ciprofloxacin, Bayer, Newbury, Berkshire, United Kingdom; piperacillin sodium and tazobactam, Wyeth, Taplow, Berkshire, United Kingdom; cephalothin and moxalactam, Lilly, Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom; imipenem, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom; ceftriaxone, Roche, Welwyn Garden City, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom; cefotaxime and cefpirome, Roussel, Uxbridge, Middlesex, United Kingdom; benzylpenicillin, cephaloridine, cloxacillin, oxacillin, gentamicin, and rifampin, Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.; ampicillin sodium, carbenicillin disodium, and clavulanate lithium, SmithKline Beecham, Brentford, Middlesex, United Kingdom; and meropenem, Zeneca, Macclesfield, Cheshire, United Kingdom.

Plasmid transfer to P. aeruginosa PU21.

Logarithmic-phase cells of P. aeruginosa 871 and 873 were mated overnight with P. aeruginosa PU21cipr on DST agar, as described previously (7, 9). Transconjugants were selected on the same medium containing ciprofloxacin (30 μg/ml) plus either ceftazidime (25 or 50 μg/ml) or gentamicin (30 μg/ml).

Detection of β-lactamases and their genes.

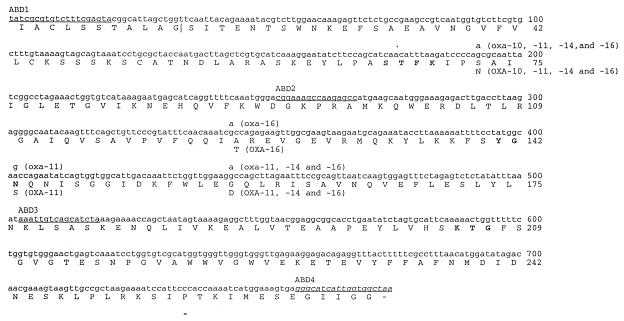

β-Lactamases were characterized by isoelectric focusing of ultrasonic extracts prepared from overnight nutrient agar cultures (22). For probing, which was undertaken as described previously (4, 10) total DNA was extracted and then digested with BamHI (when probing for blaOXA-10) or HincII (when probing for blaOXA-2) (Promega, Madison, Calif.). The probe for blaOXA-10 was made by PCR amplification of a DNA fragment from pMLH51 with primers ABD1 and ABD4 (Fig. 1). The probe for blaOXA-2 was made similarly from plasmid R46, with primers AH1 (GGAAAAGTCCATGGCAATCCGAATCTT) and AH2 (TTATCGCGCAGCGT-CCGAGTT [complementary strand]), corresponding to coordinates 118 to 144 and 955 to 935, respectively, in the sequence published by Danel et al. (6). The amplified fragments were labeled with digoxigenin with a DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Boehringer, Lewes, East Sussex, United Kingdom).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide and protein sequences of the coding region of OXA-17 β-lactamase in comparison to those of OXA-10, -11, -14, and -16 enzymes. The nucleotide sequence shown in full corresponds to that determined in this study and was allocated the GenBank accession no. AF060206. Nucleotide differences in other blaOXA-10 family genes are marked above the blaOXA-17 sequence, and the deduced amino acid changes are indicated below. The signal peptide extends from amino acid residues 1 to 20, and the proposed cleavage site is shown by a vertical line. The underlined nucleotide sequences represent the primers ABD1, ABD2, ABD3, and ABD4 used for PCR amplification or sequencing. The sequences corresponding to the amplification primers have not been independently determined for OXA-17 and are shown in italics. The three conserved elements previously described in class D β-lactamase are in boldface (14, 17).

Cloning β-lactamase genes.

Total DNA was extracted from the P. aeruginosa isolates 871 and 873 and transconjugant PU21(pMLH51) by a guanidium thiocyanate method (28). Two-microgram amounts of DNA from the test strain and of the vector pBC SK+ were then digested separately with restriction enzymes as follows: BamHI, HindIII, or PstI (Promega) for DNA from isolates 871 and 873 or BamHI only for DNA from strain PU21(pMLH51). The digestion conditions were as advised by the supplier of the enzymes. After digestion, the DNA was ligated and transformed into E. coli XL1-blue by electroporation, as described previously (6). Transformants were selected on Luria-Bertani agar (30) containing ampicillin (10 μg/ml).

Plasmids from the transformants were extracted and electrophoresed by the method of Kado and Liu (15) with plasmids of E. coli 50192 as size markers. To obtain better estimates of their sizes, plasmids were extracted and purified with Qiagen (Hybaid, Teddington, United Kingdom) kits used in accordance with the manufacturer’s directions and were digested with the same enzyme used for cloning, and then the fragments were electrophoresed and compared to a 1-kb DNA ladder marker (Gibco BRL, Uxbridge, United Kingdom).

Sequencing the β-lactamase gene.

The OXA-10-related genes from isolates 871 and 873 were amplified by PCR with ABD1 and 5′ biotin-labeled ABD4 (Fig. 1) as primers. The products were sequenced by chain termination with ABD1, ABD2, and ABD3 primers, exactly as described by Hall et al. (10). The OXA-2-related gene was amplified with AH1 and 5′ biotin-labeled AH2 and then sequenced with primers AH1 (see above); AH3, GCCTGCATCGACATTCAAGA (coordinates 434 to 453 in the sequence published by Danel et al. [6]); AH4, GCTCGGCGCTATTTGAAGAA (536 to 555); and AH5, TCGCAACTGGATACTGCGTG (833 to 851).

β-Lactamase purification.

An E. coli XL1-blue transformant with the cloned OXA-17 β-lactamase was grown overnight, with shaking, at 37°C in 0.6 liters of Luria-Bertani broth and then diluted into 12 liters of fresh, warm, identical medium. After 5 h of incubation at 37°C, the bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min at 37°C and washed once in 20 mM triethanolamine buffer, pH 7.6. The pellet was resuspended in the same buffer and frozen and thawed six times. Further purification was undertaken as for OXA-16 enzyme, with one anion- and one cation-exchange chromatographic fractionation (8). OXA-10 β-lactamase was purified from P. aeruginosa PU21(pMLH51) as described previously (7, 8). β-Lactamase purity was estimated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis on the gel system of Lugtenberg et al. (21). Protein concentrations were determined by the micro-bicinchoninic acid method (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

β-Lactamase spectrophotometric assays.

The hydrolytic activities of β-lactamases were assayed by UV spectrophotometry at 37°C in phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 (7, 10). The wavelengths were as listed by Danel et al. (4, 7), and kinetic parameters were determined from initial rate data, using the Enzfitter program (18).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The GenBank database accession number for the sequence described in Fig. 1 is AF060206.

RESULTS

Susceptibilities and β-lactamases of P. aeruginosa isolates 871 and 873.

Extracts of isolates 871 and 873 yielded β-lactamases that focused at pIs 5.3, 6.1, and 7.9. The enzyme with a pI of 5.3 corresponded to PER-1, as shown previously (5); the other two enzymes were characterized in this study.

Restriction patterns of DNA digests and hybridization with gene probes for OXA-10 and -2 β-lactamases.

DNA from isolates 871 and 873 hybridized with both the blaOXA-2 and blaOXA-10 probes, whereas DNA from PU21(pMG40) hybridized with only the blaOXA-2 probe and DNA from PU21(pMLH51) bound only the blaOXA-10 probe.

Both of the isolates carried the OXA-10-related gene on a 5-kb BamHI fragment. Banding patterns with the blaOXA-2 probe were complex because HincIII cuts twice inside the OXA-2 gene, giving a constant 0.5-kb internal fragment and two further fragments with sizes that varied according to the restriction sites in the flanking genes. The 3′ fragment had only 21 nucleotides homologous to the probe and was not detected, whereas that corresponding to the 5′ end of blaOXA-2 was detected. Isolates 871 and 873 yielded 0.5- and 1.4-kb bands with the OXA-2 gene probe, and PU21(pMG40) yielded 0.5- and 0.45-kb bands.

Sequencing blaOXA-10 and blaOXA-2 genes from isolates 871 and 873.

The blaOXA-10-related genes were amplified from both isolates by PCR, and base sequences corresponding to positions 179 to 912 of blaOXA-10 (11) were determined (see Fig. 1). This allowed prediction of the protein sequence except for the first 16 amino acids, which are part of the signal peptide, and the last 5 residues. Both isolates had the same base substitution compared with blaOXA-10, with guanine replacing adenine at position 192, predicting a change of asparagine to serine at position 73 of the protein. This new β-lactamase was named OXA-17.

The blaOXA-2-related genes were sequenced between bases 145 and 935, corresponding to the coding sequence, except for the six amino acids at the N terminus (which are part of the signal peptide) and the last five amino acids at the C terminus (6). Both sequences corresponded exactly to that of blaOXA-2 (3).

Cloning of blaOXA-17 into E. coli XL1-blue.

The presence of three β-lactamases in isolates 871 and 873 complicated purification of the OXA-17 enzyme and determination of its contribution to resistance. Transconjugation experiments did not achieve transfer of any of the β-lactamase genes, and cloning into E. coli XL1-blue was adopted to separate OXA-17 from the other β-lactamases. Transformants resistant to ampicillin at 10 μg/ml were obtained from both isolates, and crude β-lactamase extracts were prepared from representatives containing recombinant plasmids with inserts of different sizes. These extracts were subjected to isoelectric focusing (Table 2). Transformants with only the β-lactamase that focused at pI 6.1 hybridized with the probe to blaOXA-10 but not with that to blaOXA-2; those with the β-lactamase that focused at pI 7.9 showed the reverse hybridization pattern (Table 2). Transformants with each of these patterns were observed from each of the isolates 871 and 873. No producer of PER-1 β-lactamase (pI 5.3) was detected by isoelectric focusing from any of the libraries.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of E. coli XL1-blue MRF′ transformants selected with ampicillin (10 μg/ml) from the DNA libraries of isolates 871 and 873 in the pBC SK+ vector

| Library | No. of colonies | Plasmid size (kb)a | β-Lactam-ase pI | Hybridi-zation | Plasmid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate 873 | |||||

| HindIII | 10 | 10 | 7.9 | blaOXA-2 | p13A |

| 2 | 9 | 6.1 | blaOXA-10 | p13F | |

| BamHI | 4 | 11 | 7.9 | blaOXA-2 | p13D |

| PstI | 2 | 10 | 6.1 | blaOXA-10 | p13E |

| Isolate 871 | |||||

| HindIII | 17 | 10 | 7.9 | blaOXA-2 | p15A |

| 6 | 9 | 6.1 | blaOXA-10 | p15D | |

| BamHI | 4 | 18 | 6.1 | blaOXA-10 | p15C |

| PstI | 0 | NAb | NA | NA | NA |

The vector pBC SK+ had a size of 3.4 kb.

NA, not applicable.

As a control, the OXA-10 β-lactamase gene from P. aeruginosa PU21(pMLH51) was cloned and transformed into E. coli XL1-blue. Two transformants were obtained by selection on ampicillin (10 μg/ml), and each contained a 16-kb plasmid which encoded the β-lactamase.

Susceptibilities of the E. coli transformants with OXA-17 and -2 β-lactamases.

Susceptibility tests were performed on representative E. coli XL1-blue transformants with different inserts encoding OXA-17 and -2 β-lactamases (Table 3). Transformants with OXA-17 β-lactamase (pI 6.1) from the BamHI, PstI, and HindIII libraries possessed similar resistance profiles. Both the cloned OXA-17 and OXA-10 β-lactamases increased the MICs of amino and carboxy penicillins and cefoperazone for E. coli XL1-blue by 64- to 128-fold and raised those of aztreonam and ceftriaxone by 8- to 16-fold. In addition, production of OXA-17 enzyme, but not OXA-10, increased the MICs of cefotaxime, cefsulodin, ceftazidime, latamoxef, and cefepime by at least fourfold. Neither the OXA-10 nor the OXA-17 enzyme protected against carbapenems.

TABLE 3.

MICs for representative E. coli XL1-blue transformants with ampicillin resistance cloned from isolates 871 and 873

| Plasmid and β-lactamase transformanta | MIC (μg/ml)b

|

|||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amp | Pip | Pip-Clav | Pip-Taz | Cb | Cb-Clav | Cb-Taz | Caz | Caz-Clav | Caz-Taz | Ctx | Ctr | Csl | Cpim | Cpz | Mox | Azt | Imp | |

| p15C/OXA-17 from isolate 871 | 512 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 512 | 64 | 128 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 64 | 0.5 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 0.06 |

| p13E/OXA-17 from isolate 873 | 512 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 512 | 64 | 256 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 64 | 0.5 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0.12 |

| p15A/OXA-2 from isolate 871 | 256 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 512 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.06 | 32 | 0.12 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| p13A/OXA-2 from isolate 873 | 128 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 128 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.6 | 16 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

| XL1-blue(p10A)/OXA-10 | 512 | 16 | 1 | 8 | 1,024 | 128 | 128 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.25 | 8 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.06 |

| XL1-blue (no plasmid) | 4 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 16 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.06 |

Into E. coli XL1-blue.

b Amp, ampicillin; Azt, aztreonam; Cb, carbenicillin; Clav, clavulanate at 4 μg/ml; Cpim, cefepime; Cpz, cefoperazone; Csl, cefsulodin; Ctx, cefotaxime; Caz, ceftazidime; Ctr, ceftriaxone; Imp, imipenem; Mox, moxalactam (latamoxef); Pip, piperacillin and Taz, tazobactam at 4 μg/ml.

Transformants with OXA-2 β-lactamase showed resistance to ampicillin and carbenicillin and had reduced susceptibilities to piperacillin, ceftazidime, and cefoperazone, whereas susceptibilities to cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, cefsulodin, cefepime, cefpirome (not shown), aztreonam, and imipenem were not significantly altered.

Purification of OXA-17 β-lactamase.

An E. coli XL1-blue MRF′ transformant from the HindIII library of P. aeruginosa 871 was used as a source of enzyme for purification to preclude contamination by any of the other β-lactamases produced by the original P. aeruginosa isolates. OXA-10 β-lactamase was purified from P. aeruginosa PU21(pMLH51). For both enzymes, the final purity exceeded 99%; 12 liters of culture yielded 4.4 mg of pure OXA-17 β-lactamase and 3.75 mg of OXA-10 protein.

Kinetic parameters of the OXA-17 β-lactamase.

Unlike other OXA-10 derivatives (4, 8, 10), OXA-17 β-lactamase gave linear kinetics for all of the substrates tested. The lowest Km was for penicillin G (34 μM), whereas values between 153 and 300 μM were seen for oxacillin, ampicillin, carbenicillin, and cephalothin and values of 500 to 600 μM were seen for cloxacillin and ceftriaxone. The highest Kms (>2,000 μM) were for cefotaxime and cephaloridine (Table 4). The kcat exceeded 100 s−1 only for oxacillin; the values for all of the other β-lactams were less than 30 s−1. In term of Kcat/Km, the best substrate was oxacillin, followed by penicillin G and ampicillin, whereas kcat/Km, values for other substrates were at least 20-fold lower than for oxacillin. Hydrolysis of ceftazidime and carbapenems was not detected. For comparison, Table 4 also shows kinetic data for OXA-10 β-lactamase, which had biphasic kinetics for many substrates. OXA-17 generally had higher Km values than OXA-10 for cephalosporins and, except for cefotaxime, had lower kcat rates for both penicillins and cephalosporins.

TABLE 4.

Kinetic parameters for OXA-17 β-lactamase compared with OXA-10

| Substrate | OXA-17 (linear kinetics)

|

OXA-10a

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Kmb |

Vss

|

Vo

|

|||||

| Km (s−1) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Kmb | Km (μM) | kcat (s−1) | kcat/Kmb | ||||

| Penicillin G | 34 ± 0.6c | 5 ± 0.1 | 147 | 63 ± 6 | 89 ± 10 | 1,412 | −d | − | − |

| Ampicillin | 245 ± 37 | 26 ± 0.2 | 106 | 235 ± 30 | 587 ± 30 | 2,500 | 77 ± 9 | 531 ± 12 | 6,896 |

| Carbenicillin | 296 ± 31 | 2 ± 0.4 | 21 | 195 ± 13 | 31 ± 1 | 159 | 370 ± 44 | 126 ± 5 | 340 |

| Oxacillin | 153 ± 13 | 120 ± 2.0 | 784 | 222 ± 16 | 608 ± 10 | 2739 | 96 ± 8 | 660 ± 10 | 6,870 |

| Cloxacillin | 573 ± 79 | 20 ± 1.0 | 35 | 2,640 ± 323 | 520 ± 36 | 196 | 1,110 ± 100 | 2,682 ± 150 | 2,416 |

| Cephaloridine | 2,940 ± 182 | 23 ± 1.0 | 8 | 2,340 ± 300 | 79 ± 8 | 33 | 395 ± 83 | 39 ± 3 | 98 |

| Cephalothin | 286 ± 60 | 5 ± 0.1 | 17 | 38 ± 2 | 6 ± 0.1 | 158 | − | − | − |

| Cefotaxime | 2,240 ± 427 | 22 ± 3.0 | 10 | 346 ± 19 | 9 ± 0.2 | 26 | − | − | − |

| Ceftriaxone | 544 ± 52 | 1 ± 0.05 | 2 | 55 ± 2 | 3 ± 0.3 | 54 | − | − | − |

| Ceftazidime | NDe | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | − | − | − |

OXA-10 β-lactamase was shown previously (8) to give biphasic kinetics, so two sets of kinetics parameters could be determined for the initial (Vo) and steady-state (Vss) phases of hydrolysis.

(kcat/Km) × 1,000 in micromolar−1 second−1.

Values are means ± standard error.

−, results not available.

ND, hydrolysis not detected.

DISCUSSION

Isolates 871 and 873 were previously found to have PER-1 β-lactamase together with two further β-lactamases, one with a pI of 6.1 and the other with a pI of 7.9 (5). DNA from each isolate hybridized with a probe to blaOXA-10, and the enzyme with a pI of 6.1 was surmised to be related to OXA-10. The β-lactamase with a pI of 7.9 type was wrongly proposed to be an AmpC type (5). It appeared likely that one or both of these enzymes contributed to the resistance phenotype of the isolates, since their ceftazidime resistances were only partly reversed by clavulanate (Table 1) whereas strains with PER-1 β-lactamase alone became highly sensitive to ceftazidime in the presence of this inhibitor.

The present study confirmed that the two isolates had an OXA-10-related enzyme, and sequencing revealed this to be a new variant, OXA-17, with serine replacing asparagine at position 73. In addition, the studies revealed that the enzyme with a pI of 7.9 was OXA-2, not AmpC. OXA-17 β-lactamase, like OXA-10, increased the MICs of ampicillin, piperacillin, carbenicillin, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, and aztreonam. Additionally, and unlike OXA-10, OXA-17 conferred protection against cefotaxime, latamoxef, cefsulodin, cefepime, and, marginally, ceftazidime. The small effect on the MIC of ceftazidime was in contrast to those of the previously described ESBL mutants of OXA-10, namely, OXA-11, -14, and -16, all of which give high-level ceftazidime resistance (MIC > 128 μg/ml). Unlike OXA-17, these enzymes all have glycine replaced by aspartate at position 157, and this may be critical to ceftazidime resistance. The only previous OXA-10 relative to have serine at position 73 was OXA-13, which gave no resistance to cefotaxime or ceftazidime in P. aeruginosa although it did reduce the susceptibility of E. coli, especially to cefotaxime (23). However, comparison is complicated by the fact that OXA-13 has nine other amino acid differences from OXA-10, although two of these lie in the signal peptide. However, seven of the nine differences in the mature OXA-13 protein, but not the serine at position 73, are present in OXA-7, which is not an ESBL.

The mutation in OXA-17 lies close to the first conserved element of class D enzymes (15, 17), which contains the active serine. This is in contrast to the mutations in previous OXA-10 ESBLs, which lie at positions 124, 143, and 157, and to the mutations that give ESBL activity in TEM and SHV enzymes, which affect critical residues that fold towards the active serine but are remote from it in the primary sequence (16).

OXA-17 was more active than OXA-10 against oxacillin, cloxacillin, and cefotaxime and had a higher kcat for cefotaxime. Once purified, however, OXA-17 was less efficient (lower kcat/Km than OXA-10 against all the β-lactams tested—even those to which it gave greater resistance than OXA-10. This reduced efficiency was largely because the kcat values for OXA-17 were low, especially for penicillins and cephaloridine. A low kcat can arise as an artifact if an enzyme is impure, but this seems unlikely because only a single band was detected by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; furthermore, the elution peak from the final chromatography purification was symmetrical with its height (not shown). It may be that some of the purified enzyme was not active. In this context it should be noted that OXA-17 β-lactamase, unlike other OXA-10 derivatives (4, 8), was purified from E. coli and not P. aeruginosa. Maybe much of the enzyme is not correctly folded in E. coli. This might also explain why cloned OXA-10 family β-lactamases tend not to be stable in E. coli (unpublished observations). Alternatively, the OXA-17 enzyme may have been partially denatured during purification or may genuinely be less efficient than the other members of the family in hydrolyzing β-lactams, though with equally good substrate binding.

The emergence in P. aeruginosa of an OXA-10 variant that gives greater resistance to cefotaxime than to other oxyimino-aminothiazolyl cephalosporins may seem surprising, because cefotaxime is not therapeutically useful against P. aeruginosa infections. It may be that the mutation emerged by chance, or it may have been selected by low-level ceftazidime exposure or the enzyme may have transferred from another species. The absence of transmissibility from isolates 871 and 873 does not preclude the last possibility: plasmids from other species often transfer into P. aeruginosa but then cannot replicate and become chromosomally associated (13). The contributions of PER-1, OXA-2, and OXA-17 enzymes to the resistance of the original P. aeruginosa isolates is unclear, but each enzyme appeared able to contribute to give protection against ceftazidime (Table 4). Finally, it should be added that the evolution of P. aeruginosa strains with such complex arrays of potent β-lactamases is striking: the species has not, historically, been a major host for single secondary β-lactamases, which have remained much rarer than in members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (19).

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen H Y, Yuan M, Livermore D M. Mechanisms of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics amongst Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in the UK in 1993. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:300–309. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-4-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dale J W, Smith J T. The purification and properties of the β-lactamase specified by the resistance factor R-1818 in Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. Biochem J. 1971;123:493–500. doi: 10.1042/bj1230493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale J W, Godwin D, Mossakowska D, Stephenson P, Wall S. Sequence of the OXA2 β-lactamase: comparison with other penicillin-reactive enzymes. FEBS Lett. 1985;191:39–44. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(85)80989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Danel F, Hall L M C, Gur D, Livermore D M. OXA-14, another extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 (PSE-2) β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1881–1884. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.8.1881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Danel F, Hall L M C, Gur D, Akalin H E, Livermore D M. Transferable production of PER-1 β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;35:281–294. doi: 10.1093/jac/35.2.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danel F, Hall L M, Gur D, Livermore D M. OXA-15, an extended-spectrum variant of OXA-2 β-lactamase, isolated from a Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:785–790. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danel F. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates collected in Turkey. Ph.D. thesis. London, United Kingdom: University of London; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danel F, Hall L M C, Gur D, Livermore D M. OXA-16, a further extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 β-lactamase, from two Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:3117–3122. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.12.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danel F, Hall L M C, Livermore D M. Laboratory mutants of OXA-10 β-lactamase giving ceftazidime resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:339–344. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall L M C, Livermore D M, Gur D, Akova M, Akalin H E. OXA-11, an extended-spectrum variant of OXA-10 (PSE-2) β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1637–1644. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huovinen P, Huovinen S, Jacoby G A. Sequence of PSE-2 β-lactamase. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:134–136. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.1.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacoby G A. Properties of R-plasmids determining gentamicin resistance by acetylation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1974;6:239–252. doi: 10.1128/aac.6.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacoby G A. Resistance plasmids of Pseudomonas. In: Sokatch J R, editor. Bacteria: a treatise on structure and function. X. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press Inc.; 1986. pp. 265–294. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joris B, Ledent P, Dideberg O, Fonze E, Lamotte-Brasseur J, Kelly J A, Ghuysen J M, Frere J M. Comparison of the sequences of class A β-lactamases and of the secondary structure elements of penicillin-recognizing proteins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:2294–2301. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kado C I, Liu S T. Rapid procedure for detection and isolation of large and small plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;145:1365–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.145.3.1365-1373.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knox J R. Extended-spectrum and inhibitor-resistant TEM-type β-lactamases: mutations, specificity, and three-dimensional structure. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:2593–2601. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.12.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamotte-Brasseur J, Knox J, Kelly J A, Charlier P, Fonze E, Dideberg O, Frere J M. The structures and catalytic mechanisms of active-site serine β-lactamases. Biotechnol Genet Eng Rev. 1994;12:189–230. doi: 10.1080/02648725.1994.10647912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leatherbarrow R J. Enzfitter: a non-linear regression data analysis program for the IBM PC/P52. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Elsevier Biosoft; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Livermore D M. β-Lactamases in laboratory and clinical resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995;8:557–584. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Livermore D M, Maskell J P, Williams J D. Detection of PSE-2 β-lactamase in enterobacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984;25:268–272. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lugtenberg B, Meijers J, Peters R, Van der Hoek P, Van Alphen L. Electrophoretic resolution of the “major outer membrane protein” of Escherichia coli K12 into four bands. FEBS Lett. 1975;58:254–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthew M, Harris A M, Marshall M J, Ross G W. The use of analytical isoelectric focusing for detection and identification of β-lactamases. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;88:169–175. doi: 10.1099/00221287-88-1-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mugnier P, Podglajen I, Podglajen F W, Collatz E. Carbapenems as inhibitors of OXA-13, a novel integron-encoded β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 1998;144:1021–1031. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mugnier P, Dubroust P, Casin I, Arlet G, Collatz E. A TEM-derived extended-spectrum β-lactamase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2488–2493. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.11.2488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordmann P, Ronco E, Naas T, Duport C, Michel-Briand Y, Labia R. Characterisation of a novel extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:962–969. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.5.962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozen Y, Arman D, Livermore D M. Abstract book of the X Mediterranean Congress of Chemotherapy. 1996. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Ankara University Hospital, abstr. 403; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philippon L N, Naas T, Bouthors A T, Barakett V, Nordmann P. OXA-18, a class D clavulanic acid-inhibited extended-spectrum β-lactamase from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2188–2195. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen B A, Keeney D, Yang Y, Bush K. Cloning and expression of a cloxacillin-hydrolysing enzyme and a cephalosporinase from Aeromonas sobria AER 14M in Escherichia coli: requirement for an E. coli chromosomal mutation for efficient expression of the class D enzyme. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:2078–2085. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.9.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vahaboglu H, Ozturk R, Aygun G, Coskunkan F, Yaman A, Leblebicioglu H, Balik I, Aydin K, Otkun M. Widespread detection of PER-1-type extended-spectrum β-lactamases among nosocomial Acinetobacter and Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates in Turkey; a nationwide multicenter study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2265–2269. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vivian A. Plasmid expansion? Microbiology. 1994;140:213–214. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-2-213-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walsh T R, Hall L, MacGowan A P, Bennett P M. Sequence analysis of two chromosomally mediated inducible β-lactamases from Aeromonas sobria, strain 163a, one a class D penicillinase, the other an AmpC cephalosporinase. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1995;36:41–52. doi: 10.1093/jac/36.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watanabe M, Iyobe S, Inoue M, Mitsuhashi S. Transferable imipenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:147–151. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]