Summary

Background

Vaccination against Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) is not included in China's national immunization programme. To inform China's immunization polices, we estimated annual national, regional, and provincial childhood mortality and morbidity attributable to pneumococcus and Hib in 2010–17.

Methods

We estimated proportions of pneumonia and meningitis deaths and cases attributable to pneumococcus and Hib using evidence from vaccine clinical trials and surveillance studies of bacterial meningitis and pathogen-specific case fatality ratios (CFR). Then we applied the proportions to model provincial-level pneumonia cases and deaths, meningitis deaths and meningitis CFR in children aged 1–59 months, accounting for vaccine coverage. Non-pneumonia, non-meningitis (NPNM) invasive disease cases were derived by applying NPNM meningitis ratios to meningitis estimates.

Findings

In 2010–17, annual pneumococcal deaths fell by 49% from 15 600 (uncertainty range: 10 800–17 300) to 8 000 (5 500–8 900), and Hib deaths fell by 56% from 6 500 (4 500–8 800) to 2 900 (2 000–3 900). Severe pneumococcal and Hib cases decreased by 16% to 218 200 (161 500–252 200) in 2017 and 29% to 49 900 (29 000–99 100). Estimated 2017 national three-dose coverage in private market was 1·3% for PCV and 33·4% for Hib vaccine among children aged 1–59 months. Provinces in the west region had the highest disease burden.

Interpretation

Childhood mortality and morbidity attributable to pneumococcal and Hib has decreased in China, but still substantially varied by region and province. Higher vaccine coverage could further reduce disease burden.

Funding

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Keywords: Immunization, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae type b, China

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed in English and CNKI, Wanfang and CQVIP in Chinese for national and subnational estimates of pneumococcal and Hib morbidity and mortality in children in China from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2019. No regional and provincial estimates of pneumococcal and Hib morbidity and mortality were identified in the literature. Estimates of annual national pneumococcal and Hib morbidity and mortality for 2000–15 among children aged 1–59 months were reported by Wahl et al. in 2018,1 with 7 400 (uncertainty range [UR] 5 000–8 400) pneumococcal deaths, 3400 (2 200–4 600) Hib deaths, 214 800 (158 200–249 500) severe pneumococcal cases, and 77 500 (44 900–150 600) Hib cases in 2015. A major limitation of these national estimates is that they used World Health Organization (WHO)/UNICEF WEUNIC estimates for vaccine coverage of Hib vaccine and PCV, which were both 0% in China.1 However, evidence suggests that a substantial proportion of children in some parts of the country receive these vaccines through the private sector, which should affect the pneumococcal and Hib estimates of mortality and morbidity in China.

Added value of this study

The study presents comprehensive (i.e. pneumonia, meningitis, and non-pneumonia, non-meningitis) subnational estimates of pneumococcal and Hib morbidity and mortality in children aged 1–59 months in China. In addition, we identified Hib vaccine and PCV doses administered at the provincial level to estimate subnational vaccine coverage. Given the high efficacy of these vaccines on disease outcomes, we consider our national estimates more reliable than previous estimates that assumed 0% vaccine coverage. Our estimates are based on recently published subnational cause of death and case estimates of pneumonia and meningitis in China by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. Hib vaccine and PCV coverage rates were estimated using the total doses of Hib vaccine and PCV in 31 provinces, survey results of Hib vaccine and PCV dose distributions in ten provinces, and child population data by age from National Bureau of Statistics of China and Chinese CDC immunization population database. We also incorporated new meningitis data from studies published between 2006 and 2017, including eight studies from China, and meningitis surveillance data from five sites in China from the Chinese CDC. These studies reported pathogen-specific meningitis case fatality and/or the distribution of meningitis case estimates by cause.

Implications of all the available evidence

Our study provides estimates of the remaining vaccine-preventable Hib and pneumococcal disease burden in China. Furthermore, subnational estimates available here highlight provinces that have not benefited from vaccination where private market use is very limited. In the provinces with sufficient private market use of PCV and Hib vaccine, our estimates provide insight into the contribution of these vaccines to the reduction of childhood morbidity and mortality associated with pneumococcal and Hib diseases. These data can be used in economic modeling to inform national and provincial policies related to expanding access to PCV and Hib vaccine to all children in China.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

China has made substantial progress in improving child health outcomes in recent decades. China reduced the under-five mortality rate by 70% between 1990 and 2012, and achieved the under-five mortality rate target (i.e. two-thirds reduction in child mortality) specified by the Millennium Development Goal 4 in 2008.2

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) and Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) commonly cause pneumonia, meningitis, and other serious infections in children. Highly efficacious vaccines that provide protection against these pathogens are now used in many countries globally. Invasive Hib diseases in children have been virtually eliminated in countries with high routine Hib vaccine coverage.3, 4, 5 Vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal diseases in children have been substantially reduced where pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) has been used.6, 7, 8 China was estimated to be among the ten countries with the greatest number of pneumococcal and Hib deaths in children aged 1–59 months in 2000.9,10 Wahl, et al. estimated that China still had approximately 7 400 pneumococcal deaths and 3 400 Hib deaths in 2015.1

Hib vaccine and 7-valent PCV were made available in the private sector in China in 1996 and 2008, respectively. Up to June 2020, 193 of 194 countries globally have included Hib vaccine in their national immunization programmes (NIP), and PCV has been used in the NIP of 144 countries. However, China has not yet included either of these vaccines into its NIP.

Given the challenges of disease surveillance for the two pathogens, there are no directly measured estimates of pneumococcal or Hib disease burden from China. Modelled estimates can help support decision-making in the absence of empirical data. However, previous modeling studies have assumed vaccination coverage for Hib vaccine and PCV was 0%, thereby overestimating disease burden due to these pathogens. Subnational estimates are particularly useful, as provinces in China can make their own policies of adding new vaccines according to the Vaccine Management Law newly released in 2019. China is the only country in the Western Pacific Region that has not introduced Hib vaccine in its NIP and one of a handful of countries that have not introduced PCV. We used updated data, including new estimates of Hib vaccine and PCV coverage, to prepare national, regional, and provincial level estimates of Hib and pneumococcal morbidity and mortality. These data can be used for policy making in the country.

Methods

We estimated pneumococcal and Hib specific disease burden in children aged 1–59 months at the national, regional and provincial levels in China using methods similar to those that have been previously published.1 In brief, we estimated the burden separately for the three clinical syndromes associated with pneumococcus and Hib: pneumonia, meningitis, and invasive non-pneumonia, non-meningitis disease (NPNM). We used the WHO 2005 case definitions for pneumonia and meningitis (WHO 2005).11 NPNM was considered as disease outcomes associated with the isolation of pneumococcus or Hib from normally sterile body fluid but without the clinical findings of pneumonia or meningitis. Input parameters for each model are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Province-specific model parameters and sources.

| Model Parameter | Source of data from China | Sources of data from outside China and approach when data are not applicable |

|---|---|---|

| Pathogen-specific pneumonia (lower respiratory infection) | ||

| All-cause pneumonia deaths | Modelled estimates based on the Global Disease Burden (GBD) study from China1 | Not applicable |

| Pneumonia cases | Modelled estimates based on the Global Disease Burden (GBD) study from China1 | Not applicable |

| Proportion of pneumonia cases and deaths attributable to each pathogen | Not available | Global estimates with clinical trial data2 |

| Pathogen-specific meningitis | ||

| All-cause meningitis deaths | Modelled estimates based on the Global Disease Burden (GBD) study from China1 | Not applicable |

| Proportion of meningitis cases attributable to each pathogen | Meningitis surveillance in 5 sites3 and 6 studies4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 | Meningitis surveillance from Asia: 31 studiesǂ |

| Pneumococcal meningitis CFR | Pneumococcal meningitis surveillance from low mortality settings: 2 studies10,11; medium mortality settings: 1 study5 | Pneumococcal meningitis surveillance from low mortality settings: 37 studies; medium mortality settings: 13 studiesǂ |

| Hib meningitis CFR | Hib meningitis surveillance from low mortality settings: not available; medium mortality settings: not available | Hib meningitis surveillance from low mortality settings: 31 studies; medium mortality settings: 18 studiesǂ |

| Pathogen-specific NPNM | ||

| Pneumococcal NPNM case multiplier | Severe pneumococcal disease surveillance from low or medium mortality settings: not available | Severe pneumococcal disease surveillance from low or medium mortality settings: 26 studies |

| Hib NPNM case multiplier | Hib disease surveillance from low or medium mortality settings: not available | Hib disease surveillance from low or medium mortality settings: 26 studies |

| Pneumococcal NPNM CFR multiplier | Pneumococcal disease surveillance: not available | Pneumococcal disease surveillance: 2 studies |

| Hib NPNM CFR multiplier | Hib disease surveillance: not available | Hib disease surveillance: 5 studies |

| Population at risk and demographic model parameters | ||

| Child mortality | Modelled estimates based on the Global Disease Burden (GBD) study from China1 | Not applicable |

| Child population | China National Bureau of Statistics in 2010-2017, Child Immunization Population Statistics in 2010-2017 from Chinese CDC | Not applicable |

| Access to care for meningitis | Data from China Family Panel Studies in 2010, 2012, 2014, and 2016 | Linear interpolation and extrapolation to 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017 |

| Hib vaccine doses | Chinese CDC in 2010-2017 | Not applicable |

| PCV doses | Chinese CDC in 2010-2017 | Not applicable |

| 1. Zhou M, Wang H, Zeng X, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019; 394: 1145–58. | ||

| 2. Wahl B, O'Brien KL, Greenbaum A, et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000-15. Lancet Glob Health 2018; 6: e744–e57. | ||

| 3. Li Y, Yin Z, Shao Z, et al. Population-based surveillance for bacterial meningitis in China, September 2006-December 2009. Emerg Infect Dis 2014; 20: 61–9. | ||

| 4. Mao F, Wang J, Li J, Yu X. Aetiological spectrum and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial meningitis in infants and children in Hangzhou, China. Acta Paediatr 2005; 94: 1162–3. | ||

| 5. Lin M, Dong B, Tang Z, et al. Epidemiological features of bacterial meningitis among children under 5 years old in Nanning. South China Journal of Preventive Medicine 2004; 30: 30–3. In Chinese | ||

| 6. Gao J, Yi Z, Zhong J. The etiology and antibiotic resistance patterns of childhood purulent meningitis: a report of 164 cases. Journal of Pediatric Pharmacy 2013; 19: 35–8. In Chinese | ||

| 7. Wang L, Tian F, Chen G, et al. Distribution of pathogenic bacteria and analysis of drug resistance of purulent meningitis in Chongqing Area from 2009 to 2013. Journal of Pediatric Pharmacy 2013; 19: 37–42. In Chinese | ||

| 8. Du L, Han H, Shi K, et al. Pathogen distributions and drug resistance of children's bacterial meningitis in Taiyuan. Journal of Clinical Medical Literatures 2014; 11: 2068–70. In Chinese | ||

| 9. Yang Y, Leng Z, Shen X, et al. Acute bacterial meningitis in children in Hefei, China 1990-1992. Chin Med J 1996; 109: 385–8. | ||

| 10. Peng Q, Liao H, Tang J. Clinical analysis of purulent meningitis caused by streptococcus pneumoniae in 12 children. Chinese Pediatric Emergency Medicine 2013; 20: 169–71. In Chinese | ||

| 11. Shi X, Zhang B, Li Y, et al. Analysis of clinical manifestation and serotype of 39 children with meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in Suzhou. Journal of Nantong University (Medical Sciences) 2018; 38: 408–12. In Chinese | ||

A full list of citations for studies provided in Webappendix 3 & 4.

We supplemented a previous systematic review of pneumococcal and Hib invasive disease with published and unpublished data from three Chinese-language databases (i.e. CNKI, Wanfang, CQVIP).12 We followed the same literature review methodology described in the previous literature review, including review procedures, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, quality assessment criteria and search strategy (Webappendix 2).

All analyses were done with Stata, version 15 and compliant with the Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) statement (Webappendix 1).

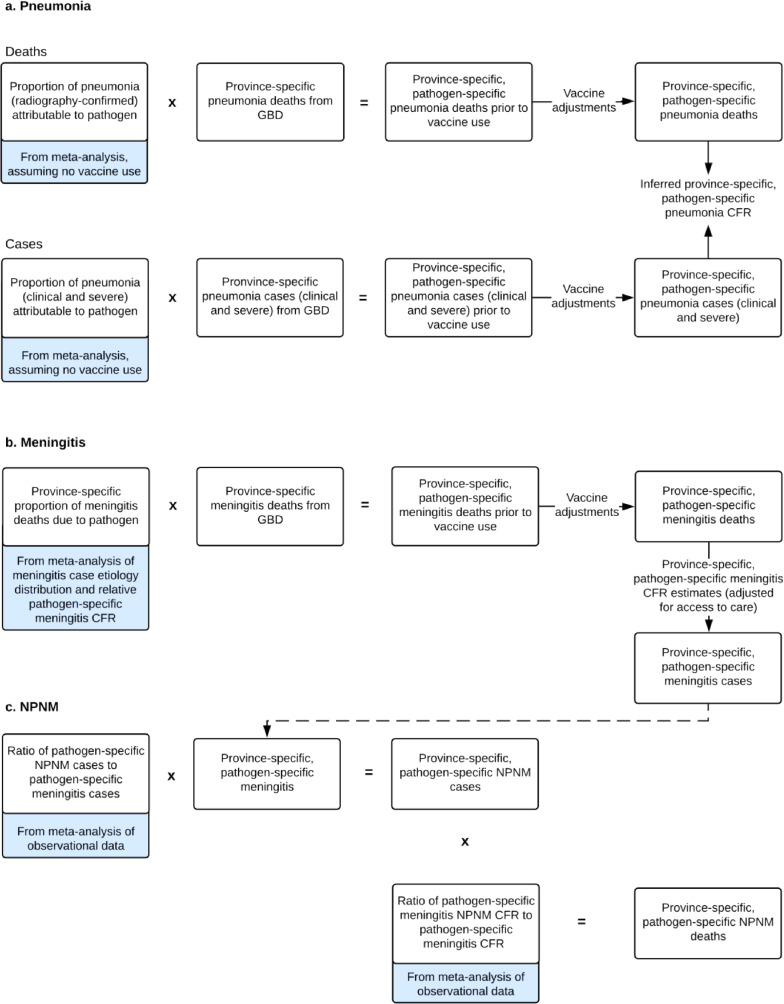

Pathogen-specific pneumonia model

Pathogen-specific pneumonia deaths and cases were prepared by applying estimates of the proportion of pneumonia deaths and cases attributable to each pathogen to all-cause pneumonia mortality and morbidity estimates (Figure 1, A. Pneumonia). The latter were obtained from annual modelled provincial-level estimates for children aged 1–59 months in China for 2010 to 2017 prepared by Global Burden of Disease, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (GBD),13 led by the Chinese CDC and Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation. The GBD study populated the model using mortality and morbidity data for children aged 1–59 months from the Disease Surveillance Point System (including Cause of Death Reporting System) maintained by the Chinese CDC, the Maternal and Child Health Surveillance System maintained by the National Office for Maternal and Child Health Surveillance of China, and various surveys, cancer registries and censuses in China. Detailed methods for deriving these estimates are described elsewhere.13, 14, 15

Figure 1.

Pathogen-specific pneumonia, meningitis, and NPNM morbidity and mortality conceptual models.

NPNM=non-pneumonia, non-meningitis. CFR=case-fatality ratio.

Efficacy against pneumonia endpoints from randomized controlled PCV and Hib vaccine trials were used to estimate the attributable fraction for each pathogen.1 Vaccine efficacy and effectiveness estimates were combined in a random effects meta-analysis, and we used the delta method to calculate standard errors for each trial. A jackknife, leave-one-study-out approach was adopted for the upper and lower bounds of pathogen-specific pneumonia fractions to address the between-study variation in vaccine efficacy estimates (Webappendix 5). We used efficacy against radiograph-confirmed, primary endpoint pneumonia as a proxy for efficacy against pneumonia mortality, as PCV and Hib vaccine trials did not explore the efficacy against pneumonia mortality. Efficacy against clinical severe pneumonia was used to estimate pathogen-specific pneumonia morbidity. We adjusted the efficacy estimates to account for the proportion of diseases not preventable by vaccines due to non-vaccine serotypes and imperfect efficacy, as described elsewhere.1 Because efficacy against invasive pneumococcal disease may overestimate pneumococcal pneumonia efficacy, we performed sensitivity analyses: (1) using vaccine efficacy against nasopharyngeal carriage and (2) adjusting the proportion of pneumonia deaths due to pneumococcus by the ratio of IPD to pneumococcal pneumonia efficacy from the adult Dutch CAPiTA trial in Webappendix 12.16

Pathogen-specific meningitis model

We used the proportion of meningitis cases attributable to each pathogen and pathogen-specific meningitis case fatality ratios (CFR) to estimate the proportion of meningitis deaths attributable to pneumococcus and Hib as previously described (Figure 1, B. Meningitis).1 For each province, we prepared summary estimates for each of these parameters by meta-analyzing data reported in literature (Webappendices 3–4). The proportion of meningitis cases attributable to each pathogen were informed by data from Asia. We stratified global data for pathogen-specific meningitis CFR by child mortality setting (i.e. <30 deaths per 1 000 livebirths, 30 to <75 deaths, and ≥75 deaths), and applied them to each province in China based on their child mortality settings.

We applied the proportion of meningitis deaths caused by pneumococcus and Hib to modelled provincial all-cause deaths of meningitis aged 1–59 months from 2010 to 2017 prepared by GBD in China to estimate pathogen-specific meningitis deaths for each province, which were divided by pathogen-specific meningitis CFR estimates to derive pneumococcal and Hib meningitis morbidity estimates.

Pathogen-specific invasive non-pneumonia, non-meningitis model

Pathogen-specific morbidity from NPNM invasive syndromes (eg, sepsis) were estimated by applying to the meningitis case estimates the pathogen-specific NPNM to meningitis case ratios, obtained from meta-estimates of published studies globally, stratified by high or very high (i.e. >75 deaths per 1 000 live births) and low or medium (i.e. <75 deaths per 1 000 live births) all-cause child mortality, as previously described (Figure 1,C. NPNM).1,17 We stratified pneumococcal NPNM cases into severe and non-severe cases. For each pathogen, we estimated NPNM deaths by multiplying NPNM severe cases by the meningitis CFR and the NPNM-to-meningitis CFR ratio obtained from a meta-estimate of published literature.

Population data

We described sources of demographic and population data for each province in Table 1. Under-five population data were retrieved from two sources: National Statistical Bureau of China and Chinese CDC. National Statistical Bureau of China collected population information in the 2010 census and in a 1% population sample survey in 2015. Chinese CDC also collected the number of children age-eligible for vaccination for each NIP vaccine from all counties and districts in China (approximately 3 000) annually in 2010–17. Provincial data for each age group were used in this study. Under-five child mortality rates in 2010–17 were obtained from the GBD in China.13

Adjustment for vaccine use

Pathogen-specific pneumococcal and Hib disease burden was initially estimated assuming no vaccine use, and then adjusted to account for provincial vaccine coverage and the impact of Hib vaccine and PCV use with dose-dependent vaccine efficacy against invasive Hib diseases10 and serotype-specific invasive pneumococcal diseases1,18,19, respectively. Chinese CDC does not collect vaccine coverage of Hib vaccine and PCV as they are not in China's NIP, but each county and/or district in China (i.e. approximately 3 000 counties and districts) is required to report the number of doses for all vaccines administered to Chinese CDC, including Hib-containing vaccines, PCV7 and PCV13. We aggregated the number of Hib vaccine and PCV doses used in each county and/or district to the provincial level. In 2019, we conducted a nationally representative survey in ten provinces by collecting vaccination records of more than 6 000 children.20 In the vaccination records, the number of Hib vaccine and PCV doses received by each respondent was clearly written or printed. We then used dose-specific vaccine efficacy data10,18,19,21 to aggregate the Hib vaccine and PCV coverage by the number of doses as an equivalent three doses of these vaccines. We did a sensitivity analysis by dividing the total number of vaccine doses by three to obtain a three-doses’ coverage of Hib vaccine and PCV respectively with an assumption that all children received three doses of each vaccine (Webappendix 14). We also applied the Hib vaccine and PCV coverage rates in 2010 to calculating the disease burden in 2017, and compared the disease burden with that under the real-world coverage rates in 2017 (Webappendix 15).

Reporting

We reported pathogen-specific mortality and incidence per 100 000 children aged 1–59 months for each year by province and region. China has 34 provinces or province-equivalent administrative regions: 31 are in Mainland China (i.e. 22 provinces, 5 autonomous regions, and 4 municipalities directly under administrative control of the central government); the other three are Taiwan, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, and Macau Special Administrative Region, which all have different pneumococcal and Hib disease patterns and Hib vaccine and PCV policies. The present study focused on the disease burden in 31 provinces in mainland China and the term “China” refers to mainland China. Similarly, “province” refers to all province-equivalent areas, including autonomous regions or municipalities, directly administrated under the central government. To show the diversity of disease burden geographically, we used three geographically contiguous and socioeconomically distinct regions: east, central, and west according to National Statistical Bureau of China (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chinese (mainland) provinces and characteristics by region in 2017.

| Region | Province | Under 5 years population (million) | Hib vaccine coverage | PCV coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 81.4 | 33.4 | 1.3 | |

| East | 26.5 | 38.1 | 2.5 | |

| East | Beijing | 0.9 | 38.6 | 9.9 |

| East | Fujian | 2.5 | 29.5 | 1.2 |

| East | Guangdong | 7.5 | 50.3 | 2.1 |

| East | Jiangsu | 3.8 | 13.2 | 1.7 |

| East | Liaoning | 1.4 | 23.6 | 2.0 |

| East | Shandong | 6.1 | 33.8 | 0.4 |

| East | Shanghai | 1.0 | 75.8 | 10.2 |

| East | Tianjin | 0.6 | 56.3 | 3.0 |

| East | Zhejiang | 2.7 | 45.2 | 5.6 |

| Central | 31.8 | 34.3 | 0.6 | |

| Central | Anhui | 3.9 | 36.1 | 0.5 |

| Central | Hainan | 0.7 | 29.5 | 1.4 |

| Central | Hebei | 5.2 | 23.3 | 0.3 |

| Central | Heilongjiang | 1.1 | 32.1 | 1.4 |

| Central | Henan | 7.4 | 42.1 | 0.7 |

| Central | Hubei | 3.2 | 51.2 | 1.0 |

| Central | Hunan | 4.4 | 27.8 | 0.8 |

| Central | Jiangxi | 3.1 | 38.1 | 0.5 |

| Central | Jilin | 1.0 | 23.4 | 0.4 |

| Central | Shanxi | 1.8 | 15.8 | 0.2 |

| West | 23.2 | 26.2 | 0.7 | |

| West | Chongqing | 1.6 | 47.3 | 2.1 |

| West | Gansu | 1.5 | 6.2 | 0.1 |

| West | Guangxi | 4.0 | 32.0 | 0.3 |

| West | Guizhou | 2.8 | 22.9 | 0.4 |

| West | Inner Mongolia | 1.0 | 11.4 | 0.0 |

| West | Ningxia | 0.5 | 7.5 | 0.4 |

| West | Qinghai | 0.4 | 5.0 | 0.0 |

| West | Shaanxi | 2.0 | 15.8 | 1.0 |

| West | Sichuan | 4.2 | 50.6 | 1.5 |

| West | Tibet | 0.3 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| West | Xinjiang | 2.0 | 2.1 | 0.3 |

| West | Yunnan | 2.8 | 24.8 | 0.8 |

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of this study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication. All authors had full access to all the data used in the study and the corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Population-based surveillance at five sites in China to detect bacterial meningitis caused by pneumococcus, Hib, and Neisseria meningitidis has been implemented since 2006 by the Chinese CDC.22 These data were used in the model. In addition, a literature review identified eight additional studies at other Chinese sites which covered east, central and west regions in China and 29 studies from other countries in Asia that reported the distribution of pathogens among children under five years old with meningitis. Three studies in China reported pneumococcal meningitis case fatality ratios, but no study in China reported Hib meningitis case fatality ratios. Additional studies from low and medium mortality settings contributed data to estimate pathogen-specific meningitis case fatality. We did not identify any studies in China reporting pneumococcal or Hib NPNM cases or CFR multipliers; therefore, data from other countries in the global study were used.17 All studies are listed in Webappendices 3–4.

Hib vaccine and PCV coverage at the national level in 2017 was estimated to be 33·4% and 1·3% respectively, but varied greatly by region and province (Webappendix 14). Hib vaccine coverage was estimated to be 50% or greater mostly in economically developed areas with higher per capita Gross Regional Domestic Product rankings in 2017 (eg, Guangdong, Hubei, Shanghai, and Tianjin), but as low as 2–7% in five provinces, all in western China. Shanghai had the highest Hib vaccine coverage with 75·8% of age-eligible children in 2017 receiving three vaccine doses. PCV coverage was low in all provinces, ranging from 3·0% to 10·2% in four developed provinces and no more than 2·1% in other areas.

We estimated that the number of pneumococcal deaths in Chinese children aged 1–59 months fell from 15 600 (UR: 10 800–17 300) in 2010 (Webappendix 8) to 8 000 (5 500–8 900) in 2017 (Table 3), and Hib deaths fell from 6 500 (4 500–8 800) in 2010 (Webappendix 9) to 2 900 (2 000–3 900) in 2017 (Table 4). In 2017, the national mortality rates per 100 000 children aged 1–59 months were 10 (7–11) for pneumococcal infection and 4 (2–5) for Hib infection (Tables 3 and 4), and pneumococcus and Hib accounted for 4% and 1% of all deaths, respectively.

Table 3.

Streptococcus pneumoniae mortality in Chinese children aged 1–59 months in 2017.

| Province |

Streptococcus pneumoniae deaths |

Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia deaths |

Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis deaths |

Streptococcus pneumoniae severe NPNM deaths |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | |||||||||

| Anhui | 277 | 190 | 310 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 208 | 147 | 217 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 37 | 23 | 49 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 33 | 20 | 44 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Beijing | 45 | 31 | 50 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 36 | 25 | 37 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Chongqing | 107 | 74 | 119 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 84 | 60 | 88 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 12 | 8 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Fujian | 149 | 103 | 165 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 115 | 82 | 120 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 18 | 11 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 10 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gansu | 284 | 195 | 318 | 19 | 13 | 22 | 211 | 150 | 220 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 39 | 24 | 52 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 35 | 21 | 46 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Guangdong | 580 | 399 | 642 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 451 | 320 | 470 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 68 | 42 | 91 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 60 | 37 | 81 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Guangxi | 290 | 200 | 319 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 234 | 166 | 243 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 30 | 18 | 40 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 26 | 16 | 36 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Guizhou | 217 | 151 | 235 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 184 | 131 | 192 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 17 | 11 | 23 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 15 | 9 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hainan | 127 | 88 | 139 | 19 | 13 | 21 | 107 | 76 | 111 | 16 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Hebei | 583 | 395 | 666 | 11 | 8 | 13 | 386 | 274 | 402 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 104 | 64 | 140 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 93 | 57 | 124 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Heilongjiang | 101 | 68 | 115 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 67 | 47 | 69 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 18 | 11 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Henan | 461 | 314 | 523 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 318 | 226 | 332 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 76 | 47 | 101 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 67 | 42 | 90 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Hubei | 154 | 107 | 169 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 125 | 89 | 131 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 15 | 9 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 8 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Hunan | 151 | 105 | 166 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 123 | 87 | 128 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inner Mongolia | 156 | 106 | 176 | 15 | 10 | 17 | 110 | 78 | 115 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 24 | 15 | 32 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 21 | 13 | 29 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Jiangsu | 90 | 61 | 101 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 64 | 46 | 67 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 7 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jiangxi | 514 | 354 | 568 | 16 | 11 | 18 | 405 | 287 | 422 | 13 | 9 | 14 | 57 | 36 | 77 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 51 | 32 | 69 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Jilin | 116 | 79 | 133 | 12 | 8 | 14 | 77 | 54 | 80 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 21 | 13 | 28 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 19 | 11 | 25 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Liaoning | 47 | 32 | 53 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 32 | 23 | 34 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ningxia | 79 | 54 | 87 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 63 | 45 | 66 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Qinghai | 135 | 93 | 149 | 36 | 25 | 40 | 107 | 76 | 112 | 28 | 20 | 30 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Shaanxi | 328 | 225 | 366 | 16 | 11 | 18 | 244 | 173 | 254 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 44 | 27 | 59 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 39 | 24 | 53 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Shandong | 158 | 107 | 181 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 100 | 71 | 105 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 30 | 19 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 27 | 17 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Shanghai | 50 | 34 | 55 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 39 | 28 | 41 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Shanxi | 269 | 185 | 302 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 198 | 140 | 206 | 11 | 8 | 11 | 38 | 24 | 51 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 34 | 21 | 45 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Sichuan | 610 | 424 | 665 | 15 | 10 | 16 | 515 | 365 | 536 | 12 | 9 | 13 | 51 | 31 | 68 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 45 | 28 | 60 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tianjin | 48 | 33 | 53 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 38 | 27 | 40 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Tibet | 157 | 108 | 173 | 57 | 40 | 64 | 139 | 99 | 145 | 51 | 36 | 53 | 9 | 5 | 15 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Xinjiang | 782 | 560 | 879 | 38 | 28 | 43 | 676 | 479 | 704 | 33 | 24 | 35 | 56 | 43 | 93 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 50 | 38 | 83 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Yunnan | 821 | 571 | 890 | 29 | 20 | 31 | 704 | 499 | 734 | 25 | 18 | 26 | 61 | 38 | 83 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 55 | 34 | 73 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Zhejiang | 127 | 87 | 142 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 92 | 65 | 96 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 18 | 11 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Central | 2753 | 1886 | 3091 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 2013 | 1427 | 2098 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 392 | 242 | 526 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 349 | 216 | 468 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| East | 1292 | 887 | 1443 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 969 | 687 | 1010 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 171 | 106 | 229 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 152 | 94 | 204 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| West | 3965 | 2763 | 4377 | 17 | 12 | 19 | 3271 | 2320 | 3409 | 14 | 10 | 15 | 367 | 234 | 512 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 326 | 209 | 456 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| National | 8010 | 5535 | 8912 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 6253 | 4434 | 6517 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 929 | 582 | 1267 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 827 | 519 | 1128 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Table 4.

Haemophilus influenzae type b mortality in Chinese children aged 1–59 months in 2017.

| Province | Hib deaths |

Hib pneumonia deaths |

Hib meningitis deaths |

Hib severe NPNM deaths |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | |||||||||

| Anhui | 87 | 59 | 119 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 79 | 55 | 104 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Beijing | 14 | 10 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 13 | 9 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chongqing | 30 | 20 | 40 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 27 | 19 | 36 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fujian | 50 | 34 | 68 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 46 | 32 | 60 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gansu | 133 | 90 | 181 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 119 | 84 | 156 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 14 | 7 | 25 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guangdong | 136 | 93 | 184 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 125 | 88 | 164 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 5 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guangxi | 100 | 69 | 135 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 93 | 65 | 122 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Guizhou | 86 | 60 | 116 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 82 | 57 | 107 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hainan | 47 | 32 | 63 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 44 | 31 | 58 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hebei | 201 | 135 | 278 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 172 | 121 | 226 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 28 | 13 | 51 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heilongjiang | 31 | 21 | 42 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 26 | 19 | 35 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Henan | 127 | 86 | 175 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 111 | 78 | 146 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 8 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hubei | 40 | 28 | 55 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 38 | 26 | 49 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hunan | 56 | 38 | 75 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 52 | 36 | 68 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Inner Mongolia | 63 | 43 | 86 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 55 | 39 | 73 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 14 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jiangsu | 35 | 24 | 48 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 31 | 22 | 41 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jiangxi | 162 | 111 | 220 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 149 | 105 | 196 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jilin | 38 | 26 | 53 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 33 | 23 | 43 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Liaoning | 17 | 11 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 14 | 10 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ningxia | 36 | 25 | 49 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 34 | 24 | 44 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Qinghai | 63 | 43 | 85 | 17 | 11 | 22 | 58 | 41 | 76 | 15 | 11 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shaanxi | 133 | 91 | 182 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 120 | 84 | 158 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shandong | 46 | 31 | 64 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 39 | 27 | 51 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shanghai | 7 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Shanxi | 112 | 76 | 154 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 100 | 70 | 132 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 22 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sichuan | 164 | 113 | 220 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 154 | 108 | 203 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tianjin | 11 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 7 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tibet | 84 | 57 | 112 | 31 | 21 | 41 | 77 | 54 | 102 | 28 | 20 | 37 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Xinjiang | 423 | 285 | 554 | 21 | 14 | 27 | 388 | 273 | 510 | 19 | 13 | 25 | 35 | 11 | 44 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yunnan | 321 | 222 | 430 | 11 | 8 | 15 | 305 | 215 | 401 | 11 | 8 | 14 | 16 | 8 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zhejiang | 34 | 23 | 46 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 30 | 21 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Central | 902 | 612 | 1233 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 804 | 565 | 1056 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 97 | 46 | 175 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| East | 349 | 238 | 476 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 314 | 221 | 413 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 35 | 16 | 62 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| West | 1636 | 1117 | 2191 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 1512 | 1064 | 1987 | 7 | 5 | 9 | 123 | 53 | 202 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National | 2888 | 1966 | 3900 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2631 | 1850 | 3457 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 255 | 115 | 440 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

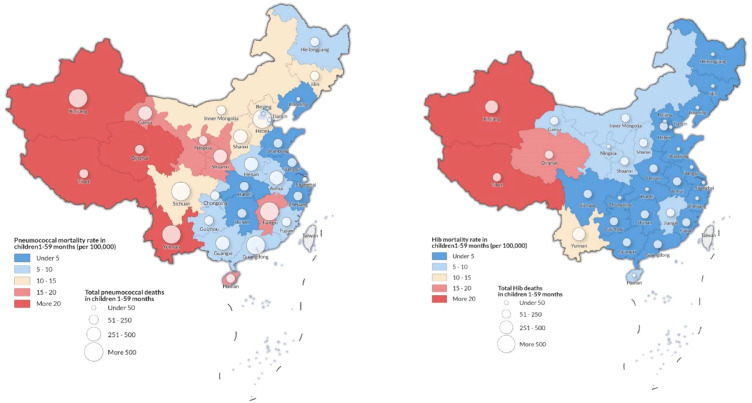

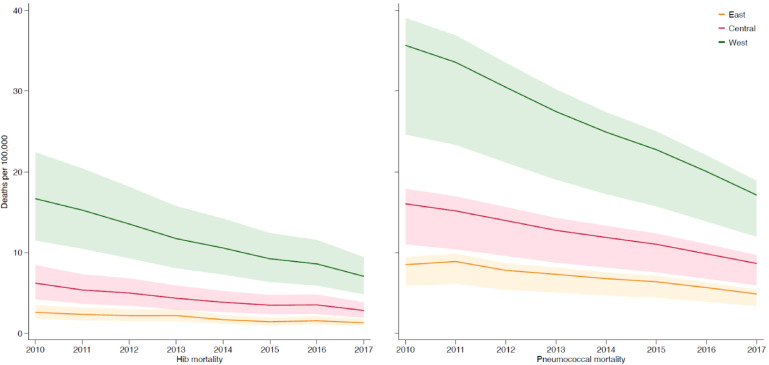

Pneumococcal and Hib mortality in China differed by region. In 2017, we estimated that 49% of pneumococcal deaths (3 600 [UR: 2 500–4 000]) and 67% of Hib deaths (1 200 [800–1 600]) occurred in the west region, which accounted for only 28% of the child population in that year (Table 3). The west region had the highest estimated pneumococcal mortality in 2017, with approximately 17 (12–19) deaths per 100 000 children aged 1–59 months, more than two times the pneumococcal mortality in the rest of China (8 [5–9]) (Table 3, Figure 2). Although the west region had the largest reduction of pneumococcal and Hib deaths from 2010 to 2017 (pneumococcal mortality declined from 36 [25–39] per 100 000 in 2010 to 17 [12–19] in 2017 and Hib mortality declined from 17 [11–22] to 7 [5–9]), the west region still had an estimated higher pneumococcal and Hib mortality in 2017 compared to other regions (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Estimated Streptococcus pneumoniae (A) and Haemophilus influenzae type b (B) deaths and mortality in 2017. Size of bubble indicates absolute number of pathogen-specific deaths.

Figure 3.

Mortality rates for Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b for 2010–2017, by region.

We reported provincial-level pneumococcal and Hib deaths and mortality rates in 2017 in Table 3 and Figure 2. Yunan province, with only 4% of under-five population in China, had the largest number of pneumococcal deaths (800 [UR: 600–900]) and the second largest Hib deaths (300 [200–400]), representing 10% and 11% of all pneumococcal and Hib deaths in China, respectively. Tibet had the highest pneumococcal mortality rate in China with 57 [UR: 40–64] per 100 000 children aged 1–59 months. Qinghai and Xinjiang also had pneumococcal mortality rates more than 30 per 100 000 aged 1–59 months. Hib deaths and mortality rates in 2017 followed the similar pattern as those for pneumococcus. In 2017, six provinces with the lowest Hib coverage in China were all in the west region: Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia. Together, these provinces accounted for 28% of Hib deaths in China in 2017 despite only accounting for 7% of under-five population.

Pneumonia accounted for 78% and 91% of pneumococcal and Hib mortality, respectively, among all the syndromes associated with these two pathogens. Pneumonia was the most common syndrome associated with pneumococcus and Hib in each province between 2000 and 2017.

Pneumococcal cases and incidence rates were reported in Table 5 and Webappendix 10. Clinical pneumococcal pneumonia cases in China decreased from 633 400 (UR: 546 500–753 000) in 2010 to 553 000 (477 100–657 400) in 2017. In 2017, Guangdong province had the largest number of pneumococcal pneumonia cases of 66 500 (57 400–79 100), and Tibet had the highest pneumococcal pneumonia incidence rate of 1 000 (900–1 200) per 100 000 children aged 1–59 months.

Table 5.

Streptococcus pneumoniae cases in Chinese children aged 1–59 months in 2017.

| Province |

Streptococcus pneumoniae pneumonia cases |

Streptococcus pneumoniae severe pneumonia cases |

Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis casesa |

Streptococcus pneumoniae severe NPNM cases |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | |||||||||

| Anhui | 23379 | 20172 | 27791 | 605 | 522 | 719 | 8572 | 6422 | 9777 | 222 | 166 | 253 | 293 | 181 | 393 | 8 | 5 | 10 | 333 | 206 | 446 | 9 | 5 | 12 |

| Beijing | 7600 | 6558 | 9035 | 812 | 700 | 965 | 2787 | 2088 | 3178 | 298 | 223 | 339 | 39 | 24 | 53 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 45 | 28 | 60 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Chongqing | 11714 | 10107 | 13925 | 714 | 616 | 849 | 4295 | 3218 | 4899 | 262 | 196 | 298 | 98 | 61 | 132 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 111 | 69 | 150 | 7 | 4 | 9 |

| Fujian | 14825 | 12791 | 17622 | 598 | 516 | 710 | 5435 | 4072 | 6199 | 219 | 164 | 250 | 141 | 87 | 189 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 160 | 99 | 215 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| Gansu | 10968 | 9463 | 13038 | 745 | 643 | 885 | 4021 | 3013 | 4587 | 273 | 205 | 311 | 310 | 192 | 417 | 21 | 13 | 28 | 353 | 218 | 473 | 24 | 15 | 32 |

| Guangdong | 66523 | 57398 | 79077 | 885 | 764 | 1052 | 24390 | 18273 | 27819 | 324 | 243 | 370 | 542 | 335 | 727 | 7 | 4 | 10 | 615 | 381 | 826 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

| Guangxi | 24189 | 20870 | 28753 | 601 | 518 | 714 | 8868 | 6644 | 10115 | 220 | 165 | 251 | 238 | 147 | 319 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 270 | 167 | 362 | 7 | 4 | 9 |

| Guizhou | 15883 | 13704 | 18880 | 562 | 485 | 668 | 5823 | 4363 | 6642 | 206 | 154 | 235 | 137 | 85 | 184 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 156 | 96 | 209 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| Hainan | 4410 | 3805 | 5243 | 669 | 577 | 795 | 1617 | 1211 | 1844 | 245 | 184 | 280 | 87 | 54 | 117 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 99 | 61 | 133 | 15 | 9 | 20 |

| Hebei | 34605 | 29858 | 41135 | 669 | 577 | 795 | 12687 | 9505 | 14471 | 245 | 184 | 280 | 831 | 515 | 1116 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 944 | 584 | 1267 | 18 | 11 | 24 |

| Heilongjiang | 9173 | 7914 | 10904 | 835 | 720 | 992 | 3363 | 2520 | 3836 | 306 | 229 | 349 | 144 | 89 | 193 | 13 | 8 | 18 | 163 | 101 | 219 | 15 | 9 | 20 |

| Henan | 36801 | 31753 | 43746 | 496 | 428 | 590 | 13493 | 10109 | 15390 | 182 | 136 | 207 | 604 | 374 | 810 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 686 | 424 | 920 | 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Hubei | 18328 | 15813 | 21786 | 568 | 490 | 676 | 6720 | 5034 | 7664 | 208 | 156 | 238 | 122 | 76 | 164 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 139 | 86 | 186 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Hunan | 23108 | 19938 | 27469 | 521 | 449 | 619 | 8472 | 6347 | 9663 | 191 | 143 | 218 | 119 | 74 | 160 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 135 | 84 | 181 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Inner Mongolia | 8772 | 7569 | 10427 | 835 | 721 | 993 | 3216 | 2409 | 3668 | 306 | 229 | 349 | 193 | 119 | 258 | 18 | 11 | 25 | 219 | 135 | 293 | 21 | 13 | 28 |

| Jiangsu | 23698 | 20447 | 28170 | 619 | 534 | 736 | 8688 | 6509 | 9910 | 227 | 170 | 259 | 107 | 66 | 144 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 122 | 75 | 163 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Jiangxi | 19089 | 16471 | 22692 | 611 | 527 | 727 | 6999 | 5243 | 7983 | 224 | 168 | 256 | 458 | 284 | 615 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 521 | 322 | 699 | 17 | 10 | 22 |

| Jilin | 8762 | 7560 | 10416 | 918 | 792 | 1091 | 3213 | 2407 | 3664 | 336 | 252 | 384 | 166 | 103 | 223 | 17 | 11 | 23 | 189 | 117 | 254 | 20 | 12 | 27 |

| Liaoning | 12264 | 10582 | 14579 | 872 | 753 | 1037 | 4497 | 3369 | 5129 | 320 | 240 | 365 | 60 | 37 | 81 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 69 | 42 | 92 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Ningxia | 3103 | 2678 | 3689 | 688 | 594 | 818 | 1138 | 852 | 1298 | 252 | 189 | 288 | 66 | 41 | 89 | 15 | 9 | 20 | 75 | 47 | 101 | 17 | 10 | 22 |

| Qinghai | 2968 | 2561 | 3528 | 788 | 680 | 937 | 1088 | 815 | 1241 | 289 | 216 | 330 | 118 | 73 | 159 | 31 | 19 | 42 | 134 | 83 | 180 | 36 | 22 | 48 |

| Shaanxi | 13118 | 11319 | 15594 | 656 | 566 | 780 | 4810 | 3603 | 5486 | 240 | 180 | 274 | 353 | 218 | 473 | 18 | 11 | 24 | 401 | 248 | 538 | 20 | 12 | 27 |

| Shandong | 31314 | 27019 | 37224 | 515 | 445 | 613 | 11481 | 8601 | 13095 | 189 | 142 | 216 | 242 | 150 | 324 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 274 | 170 | 368 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Shanghai | 7853 | 6776 | 9335 | 822 | 710 | 978 | 2879 | 2157 | 3284 | 301 | 226 | 344 | 44 | 27 | 60 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 50 | 31 | 68 | 5 | 3 | 7 |

| Shanxi | 12895 | 11126 | 15329 | 698 | 602 | 829 | 4728 | 3542 | 5392 | 256 | 192 | 292 | 304 | 188 | 408 | 16 | 10 | 22 | 345 | 214 | 463 | 19 | 12 | 25 |

| Sichuan | 35875 | 30954 | 42645 | 863 | 745 | 1026 | 13153 | 9854 | 15002 | 316 | 237 | 361 | 403 | 250 | 541 | 10 | 6 | 13 | 458 | 284 | 615 | 11 | 7 | 15 |

| Tianjin | 4743 | 4092 | 5638 | 823 | 710 | 978 | 1739 | 1303 | 1983 | 302 | 226 | 344 | 43 | 27 | 58 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 49 | 30 | 65 | 8 | 5 | 11 |

| Tibet | 2738 | 2362 | 3255 | 1003 | 865 | 1192 | 1004 | 752 | 1145 | 368 | 276 | 419 | 33 | 18 | 53 | 12 | 7 | 19 | 37 | 20 | 60 | 14 | 7 | 22 |

| Xinjiang | 14296 | 12335 | 16994 | 703 | 607 | 836 | 5241 | 3927 | 5978 | 258 | 193 | 294 | 291 | 222 | 481 | 14 | 11 | 24 | 330 | 252 | 546 | 16 | 12 | 27 |

| Yunnan | 27765 | 23956 | 33005 | 976 | 842 | 1160 | 10180 | 7626 | 11611 | 358 | 268 | 408 | 491 | 304 | 659 | 17 | 11 | 23 | 558 | 345 | 749 | 20 | 12 | 26 |

| Zhejiang | 22278 | 19222 | 26482 | 829 | 715 | 986 | 8168 | 6119 | 9316 | 304 | 228 | 347 | 146 | 90 | 195 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 165 | 102 | 222 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Central | 190550 | 164411 | 226510 | 599 | 517 | 712 | 69862 | 52340 | 79684 | 220 | 165 | 251 | 3129 | 1936 | 4198 | 10 | 6 | 13 | 3554 | 2199 | 4768 | 11 | 7 | 15 |

| East | 191099 | 164884 | 227163 | 722 | 623 | 858 | 70063 | 52491 | 79914 | 265 | 198 | 302 | 1364 | 844 | 1831 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 1550 | 959 | 2079 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| West | 171388 | 147877 | 203732 | 740 | 639 | 880 | 62837 | 47077 | 71671 | 271 | 203 | 310 | 2731 | 1729 | 3764 | 12 | 7 | 16 | 3102 | 1964 | 4275 | 13 | 8 | 18 |

| National | 553037 | 477172 | 657405 | 679 | 586 | 807 | 202762 | 151908 | 231270 | 249 | 187 | 284 | 7225 | 4510 | 9793 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 8206 | 5123 | 11123 | 10 | 6 | 14 |

All Streptococcus pneumoniae meningitis cases are severe.

We estimated 218 200 (UR: 161 500–252 200) cases of severe pneumococcus (i.e. severe pneumococcal pneumonia, pneumococcal meningitis, and severe pneumococcal NPNM) in 2017, and severe pneumococcal pneumonia accounted for 93% of all the severe pneumococcal cases. Guangdong (25 500 [19 000–29 400]), Henan (14 800 [10 900–17 100]), and Hebei (14 500 [10 600–16 900]) had the highest number of estimated severe pneumococcal cases for children aged 1–59 months in 2017, and these three provinces also had relatively larger provincial population in China.

Hib cases and incidence rates were reported in Table 6 and Webappendix 11. We estimated that the number of Hib pneumonia cases decreased from 325 400 (UR: 297 100–531 600) in 2010 to 245 100 (223 800–400 500) in 2017. The number of severe Hib cases, including severe Hib pneumonia, Hib meningitis, and severe Hib NPNM, was estimated to decrease from 70 500 (40 600–139 400) in 2010 to 49 900 (29 000–99 100) in 2017, with a reduction of 29%. In 2017, severe Hib pneumonia accounted for 86% of all severe Hib cases.

Table 6.

Haemophilus influenzae type b cases in Chinese children aged 1–59 months in 2017.

| Province | Hib pneumonia cases |

Hib severe pneumonia cases |

Hib meningitis casesa |

Hib severe NPNM casesb |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

Number |

Rate per 100 000 |

|||||||||||||||||

| Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | Mean | UR | |||||||||

| Anhui | 9966 | 9099 | 16283 | 258 | 236 | 421 | 1751 | 1048 | 3533 | 45 | 27 | 91 | 189 | 89 | 342 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 64 | 30 | 115 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Beijing | 3276 | 2991 | 5352 | 350 | 319 | 572 | 575 | 345 | 1161 | 61 | 37 | 124 | 26 | 12 | 47 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Chongqing | 4227 | 3859 | 6907 | 258 | 235 | 421 | 743 | 445 | 1499 | 45 | 27 | 91 | 55 | 26 | 99 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 19 | 9 | 34 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Fujian | 6952 | 6348 | 11359 | 280 | 256 | 458 | 1221 | 731 | 2465 | 49 | 29 | 99 | 95 | 45 | 171 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 32 | 15 | 58 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Gansu | 6685 | 6103 | 10922 | 454 | 415 | 742 | 1174 | 703 | 2370 | 80 | 48 | 161 | 314 | 148 | 567 | 21 | 10 | 39 | 106 | 50 | 191 | 7 | 3 | 13 |

| Guangdong | 22747 | 20769 | 37167 | 303 | 276 | 494 | 3996 | 2392 | 8065 | 53 | 32 | 107 | 254 | 119 | 458 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 86 | 40 | 155 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Guangxi | 10905 | 9957 | 17818 | 271 | 247 | 442 | 1916 | 1147 | 3866 | 48 | 28 | 96 | 162 | 76 | 293 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 55 | 26 | 99 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Guizhou | 8060 | 7359 | 13170 | 285 | 261 | 466 | 1416 | 848 | 2858 | 50 | 30 | 101 | 104 | 49 | 189 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 35 | 17 | 64 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Hainan | 2070 | 1890 | 3381 | 314 | 286 | 513 | 364 | 218 | 734 | 55 | 33 | 111 | 63 | 29 | 113 | 9 | 4 | 17 | 21 | 10 | 38 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Hebei | 17463 | 15944 | 28533 | 337 | 308 | 551 | 3068 | 1837 | 6191 | 59 | 35 | 120 | 640 | 302 | 1157 | 12 | 6 | 22 | 216 | 102 | 390 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Heilongjiang | 4157 | 3795 | 6792 | 378 | 345 | 618 | 730 | 437 | 1474 | 66 | 40 | 134 | 98 | 46 | 177 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 33 | 16 | 60 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| Henan | 14348 | 13100 | 23444 | 193 | 177 | 316 | 2520 | 1509 | 5087 | 34 | 20 | 69 | 362 | 170 | 653 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 122 | 57 | 220 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Hubei | 6126 | 5593 | 10009 | 190 | 173 | 310 | 1076 | 644 | 2172 | 33 | 20 | 67 | 64 | 30 | 115 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 21 | 10 | 39 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Hunan | 11036 | 10076 | 18032 | 249 | 227 | 406 | 1939 | 1161 | 3913 | 44 | 26 | 88 | 85 | 40 | 154 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 29 | 14 | 52 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Inner Mongolia | 5060 | 4620 | 8267 | 482 | 440 | 787 | 889 | 532 | 1794 | 85 | 51 | 171 | 169 | 80 | 305 | 16 | 8 | 29 | 57 | 27 | 103 | 5 | 3 | 10 |

| Jiangsu | 13543 | 12365 | 22128 | 354 | 323 | 578 | 2379 | 1424 | 4802 | 62 | 37 | 125 | 86 | 40 | 155 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 29 | 14 | 52 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Jiangxi | 7900 | 7213 | 12908 | 253 | 231 | 413 | 1388 | 831 | 2801 | 44 | 27 | 90 | 295 | 139 | 533 | 9 | 4 | 17 | 99 | 47 | 180 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Jilin | 4419 | 4034 | 7219 | 463 | 423 | 756 | 776 | 465 | 1567 | 81 | 49 | 164 | 123 | 58 | 221 | 13 | 6 | 23 | 41 | 19 | 75 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Liaoning | 6228 | 5687 | 10176 | 443 | 404 | 724 | 1094 | 655 | 2208 | 78 | 47 | 157 | 46 | 22 | 84 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 16 | 7 | 28 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ningxia | 1869 | 1707 | 3054 | 414 | 378 | 677 | 328 | 197 | 663 | 73 | 44 | 147 | 61 | 29 | 110 | 14 | 6 | 24 | 21 | 10 | 37 | 5 | 2 | 8 |

| Qinghai | 1829 | 1670 | 2988 | 486 | 443 | 793 | 321 | 192 | 648 | 85 | 51 | 172 | 109 | 51 | 197 | 29 | 14 | 52 | 37 | 17 | 67 | 10 | 5 | 18 |

| Shaanxi | 7257 | 6626 | 11858 | 363 | 331 | 593 | 1275 | 763 | 2573 | 64 | 38 | 129 | 298 | 141 | 539 | 15 | 7 | 27 | 101 | 47 | 182 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Shandong | 13782 | 12584 | 22519 | 227 | 207 | 371 | 2421 | 1450 | 4886 | 40 | 24 | 80 | 160 | 75 | 289 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 54 | 25 | 97 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Shanghai | 1511 | 1379 | 2468 | 158 | 144 | 258 | 265 | 159 | 536 | 28 | 17 | 56 | 12 | 6 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Shanxi | 7098 | 6481 | 11598 | 384 | 351 | 627 | 1247 | 747 | 2517 | 67 | 40 | 136 | 274 | 129 | 494 | 15 | 7 | 27 | 92 | 43 | 167 | 5 | 2 | 9 |

| Sichuan | 12150 | 11094 | 19853 | 292 | 267 | 478 | 2134 | 1278 | 4308 | 51 | 31 | 104 | 213 | 100 | 385 | 5 | 2 | 9 | 72 | 34 | 130 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Tianjin | 1451 | 1325 | 2371 | 252 | 230 | 411 | 255 | 153 | 514 | 44 | 26 | 89 | 20 | 9 | 36 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Tibet | 1732 | 1581 | 2829 | 634 | 579 | 1037 | 304 | 182 | 614 | 111 | 67 | 225 | 31 | 14 | 48 | 11 | 5 | 18 | 10 | 5 | 16 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Xinjiang | 9075 | 8285 | 14827 | 446 | 407 | 729 | 1594 | 954 | 3217 | 78 | 47 | 158 | 289 | 95 | 366 | 14 | 5 | 18 | 97 | 32 | 123 | 5 | 2 | 6 |

| Yunnan | 13772 | 12574 | 22501 | 484 | 442 | 791 | 2419 | 1448 | 4883 | 85 | 51 | 172 | 362 | 170 | 653 | 13 | 6 | 23 | 122 | 57 | 220 | 4 | 2 | 8 |

| Zhejiang | 8433 | 7700 | 13779 | 314 | 287 | 513 | 1481 | 887 | 2990 | 55 | 33 | 111 | 80 | 38 | 145 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 27 | 13 | 49 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Central | 84582 | 77225 | 138198 | 266 | 243 | 435 | 14858 | 8896 | 29988 | 47 | 28 | 94 | 2192 | 1032 | 3960 | 7 | 3 | 12 | 739 | 348 | 1335 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| East | 77924 | 71146 | 127320 | 294 | 269 | 481 | 13688 | 8196 | 27628 | 52 | 31 | 104 | 779 | 367 | 1407 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 263 | 124 | 474 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| West | 82621 | 75435 | 134995 | 357 | 326 | 583 | 14513 | 8690 | 29293 | 63 | 38 | 127 | 2168 | 980 | 3753 | 9 | 4 | 16 | 731 | 330 | 1265 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| National | 245127 | 223806 | 400514 | 301 | 275 | 492 | 43059 | 25781 | 86909 | 53 | 32 | 107 | 5139 | 2379 | 9120 | 6 | 3 | 11 | 1732 | 802 | 3074 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

All Hib meningitis cases are severe.

All Hib NPNM cases are severe.

Our disease burden estimates for both pathogens would vary with changes in estimates for all-cause pneumonia mortality and the fraction of pneumonia deaths associated with each pathogen. We reported the results of sensitivity analyses in Webappendix 13 using alternative sources of all-cause pneumonia at the national level. Based on these sensitivity analyses, pneumonia deaths could range from 4 700 (UR: 3 300–4 900) to 8 900 (6 300–9 300) for pneumococcus and 2 000 (1 400–2 600) to 5 500 (3 900–7 200) for Hib. In addition, in the probe approach, we used estimates of vaccine-type efficacy against invasive diseases to estimate the proportion of pneumonia deaths attributable to pneumococcus. Our sensitivity analyses using alternative estimates serotype-specific vaccine efficacy indicated that our approach might underestimate the contribution of pneumococcus to deaths from pneumonia. Specifically, we found that there might have been 12 000 (7 300–12 900) pneumococcal pneumonia deaths in 2017.

To quantify the effects of increased vaccine coverage over years, we also calculated the disease burden in 2017 by adopting the same three-dose vaccine coverage rates in 2010 (Webappendix 15). Nationally in the year of 2017, when increasing Hib vaccine coverage from 21.6% (2010) to 33.4% (2017), and PCV coverage from 0.5% (2010) to 1.3% (2017), pneumococcal deaths, Hib deaths, pneumococcal cases and Hib cases would decrease by 0.4% (8 043 to 8 010), 12.9% (3 316 to 2 888), 0.8% (557 241 to 553 037) and 13.7% (284 046 to 245 127), respectively.

Discussion

The present study estimated national, regional and provincial burden of pneumococcal and Hib pneumonia, meningitis, and NPNM in China in children aged 1–59 months. Even though PCV and Hib vaccine are not currently included in China's NIP, pneumococcal and Hib deaths declined from 2010 to 2017. These declines are likely attributable to the scale-up and effective delivery of maternal and child health programmes. Our pathogen-specific morbidity and mortality estimates can be used to further monitor maternal and child programmes in China.

In 2010–17, estimated Hib vaccine coverage in China increased from 21.6% to 33.4%, and Hib deaths and cases reduced by 56% and 26%, respectively. Pneumococcal deaths and cases declined by 49% and 14% in 2010–17, while PCV coverage rate did not increase substantially, its effect on pneumococcal mortality and morbidity was marginal.

The reduction in deaths attributable to Hib and pneumococcus reflects overall child survival trends in China during 2010–17. China's socioeconomic development (i.e. GDP growth, female education, improved access to healthcare, health insurance coverage) and China's maternal and health interventions and programmes (i.e. equal access to basic public health services, free health checks for children aged 0–6 years) contributed to the decline of child mortality, including pneumonia.23 Vaccination is seldom taken into account in such models, so its contribution to mortality decline has not been recognized until now.

We estimated that a disproportionate number of pneumococcal and Hib deaths occurred in some regions. The west region had more pneumococcal and Hib deaths and higher mortality rates compared to the east and central regions, despite it only accounts for 28% of the population in 2017. The west region is less developed, with poorer socioeconomic development indicators, and lower PCV and Hib vaccine coverage in the private sector. Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Tibet had the highest Hib mortality rates per 100 000 children in 2017 in China, and these three provinces also had the lowest Hib vaccine coverage. However, many of the government-launched maternal and child health programmes have focused on this region in the past two decades. These efforts might have contributed to the largest reduction of child mortality between 2010 and 2017 in China. The west region will achieve even higher child mortality reductions if Hib vaccine and PCV are included in the NIP.

China has a large population and there are substantial socioeconomic, cultural, and geographic differences across the country. Our subnational model enables us to assess province-level differences in vaccine coverage and their effects on disease outcomes. In 2008, China expanded its NIP from 6 vaccines to 15 vaccines. However, Hib vaccine and PCV were not included in part due to their high costs. Since then, China has not added any new vaccines into its NIP. Our estimates of pneumococcal and Hib disease burden provide new evidence to support the introduction of these vaccines into China's NIP. Provincial governments in China are empowered to include specific vaccines into local immunization programmes. For example, seasonal flu vaccine and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) have been provided to the elderly for free in several provinces and municipalities.24,25 Our provincial estimates could therefore inform local policies regarding Hib vaccine and PCV.

As China is the most populous country in the world, the reported Hib and pneumococcal disease burden in this country is also of important reference value, especially for nearby areas with similar epidemiological characteristics. China is also the only country which has not included Hib vaccine in its NIP despite recommendations from the WHO to include in all infant immunization programs.26 The findings can help ensure all countries in the region are using this lifesaving vaccine. Moreover, some countries in the Western Pacific region have not yet included PCV in their NIPs, including Nauru, Tonga, Tuvalu, Vanuatu and Viet Nam. The present analysis in China might help decision-making related to vaccination in these countries and therefore support global and regional efforts to reduce disease burden due to pneumococcus.

Wahl et al. estimated that China had 7 400 (5 000–8 400) pneumococcal deaths, 3 400 (2 200–4 600) Hib deaths, 214 800 (158 200–249 500) severe pneumococcal cases, and 77 500 (44 900–150 600) severe Hib cases at the national level in 2015.1 The present study estimated that there were 10 200 (UR: 7 000–11 400) pneumococcal deaths, 3 600 (2 400–4 800) Hib deaths, 230 500 (170 100–267 100) severe pneumococcal cases, and 50 100 (28 900–99 200) severe Hib cases at the national level in 2015 (reported in Webappendix 10 and 11). The estimation approach adopted by Wahl et al. and the present study are similar; however, the differences in these estimates may lie in the inclusion of vaccine coverage data, subnational estimates, and new estimates of all-cause pneumonia and meningitis mortality.

Additionally, in the present study, we provide estimates of disease burden for Hib and pneumococcus for 2010–2017. Provincial-level all-cause pneumonia and meningitis disease burden data after 2017 were not available. We further calculated the national-level pathogen-specific disease burden for 2018 and 2019 using available national-level data from GBD IHME in Webappendix 16, which may provide more up-to-date references despite the lack of provincial-level estimates.

Our analysis has several limitations, many of which have been described in detail elsewhere.1 First, the pathogen-specific pneumonia models used data from vaccine clinical trials conducted in several countries around the world, none of which were done in China and only one was from the Western Pacific Region.27 Applying these proportions derived from studies done in other settings could result in biased estimates. In addition, we used vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease efficacy as a proxy for vaccine-type pneumococcal pneumonia efficacy when estimating the proportion of pneumococcus pneumonia deaths, which might underestimate the contribution of pneumococcus to pneumonia deaths. To address this limitation, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and found that pneumococcal pneumonia deaths could be roughly twice the estimates from our base case model. Another limitation is that we were unable to account for some underlying risk factors, including HIV infection and sickle cell; however, given their low overall prevalence in China, the impact on our models would likely be modest. Our models also did not account for outbreaks of pathogen-specific meningitis, which might underestimate Hib and pneumococcal meningitis disease burden. Last, there were no data from China on pathogen-specific NPNM, so data from studies done in geographically and epidemiologically relevant settings were used. It would help improve disease burden estimates if additional pathogen-specific data were available from observational studies in China.

According to our subnational estimates, China has made substantial progress in reducing mortality and morbidity caused by pneumococcus and Hib in 2010–17, but there are still severe regional and provincial disparities. These achievements were made with other childhood interventions, while the impacts of PCV and Hib vaccine was limited, even if both have been available in the private market for a long time. Introducing PCV and Hib vaccine into NIP or specific provinces has the potential to substantially accelerate the reduction of childhood pneumococcal and Hib morbidity and mortality towards meeting the Sustainable Development Goal child survival targets by 2030.

Contributors

XL, BW, and WY did the analyses for the pneumococcal and Hib mortality and morbidity estimates and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BW, YQ, ZY, MDK, and HF designed the project and oversaw the analysis and manuscript writing. TX, HZ, and CG prepared provincial vaccine coverage and population data in China. YG had oversight responsibility for the project. All coauthors provided feedback during the design and interpretation of the project. They also contributed to revisions of the manuscript. HF supervised the entire project. XL, BW, and WY contributed equally as the co-first authors. ZY, MDK, and HF contributed equally as the senior authors.

Data sharing statement

Detailed model code and results are available from online open access database. Some model inputs are also available from the online open access database. Individuals wishing to obtain complete model inputs should submit requests to Brian Wahl (bwahl@jhu.edu).

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

HF reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Sanofi Pasteur. BW reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. MDK reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Pfizer and Gavi Alliance, and personal fees from Merck. CG reports grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Pfizer, and personal fees from Merck. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100430.

Contributor Information

Zundong Yin, Email: yinzd@chinacdc.cn.

Maria Deloria Knoll, Email: mknoll2@jhu.edu.

Hai Fang, Email: hfang@hsc.pku.edu.cn.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Wahl B., O'Brien K.L., Greenbaum A., et al. Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(7):e744–ee57. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30247-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Li X., Zhou M., et al. Under-5 mortality in 2851 Chinese counties, 1996–2012: a subnational assessment of achieving MDG 4 goals in China. Lancet. 2016;387(10015):273–283. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00554-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy T.V., White K.E., Pastor P., et al. Declining incidence of Haemophilus influenzae type b disease since introduction of vaccination. JAMA. 1993;269(2):246–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adegbola R.A., Secka O., Lahai G., et al. Elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease from the Gambia after the introduction of routine immunisation with a Hib conjugate vaccine: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005;366(9480):144–150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66788-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hammitt L.L., Crane R.J., Karani A., et al. Effect of Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccination without a booster dose on invasive H influenzae type b disease, nasopharyngeal carriage, and population immunity in Kilifi, Kenya: a 15-year regional surveillance study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016;4(3):e185–ee94. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00316-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pilishvili T., Lexau C., Farley M.M., et al. Sustained reductions in invasive pneumococcal disease in the era of conjugate vaccine. J Infect Dis. 2010;201(1):32–41. doi: 10.1086/648593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waight P.A., Andrews N.J., Ladhani N.J., Sheppard C.L., Slack M.P.E., Miller E. Effect of the 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on invasive pneumococcal disease in England and Wales 4 years after its introduction: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(5):903–911. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70044-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Gottberg A., de Gouveia L., Tempia S., et al. Effects of vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease in South Africa. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1889–1899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O'Brien K.L., Wolfson L.J., Watt J.P., et al. Burden of disease caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):893–902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watt J.P., Wolfson L.J., O'Brien K.L., et al. Burden of disease caused by Haemophilus influenzae type b in children younger than 5 years: global estimates. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):903–911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Illnesses with Limited Resources. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. Global Literature Review of Haemophilus influenzae type b and Streptococcus pneumoniae Invasive Disease Among Children less than Five Years of Age: 1980–2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou M., Wang H., Zeng X., et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2019;394(10204):1145–1158. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30427-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collaborators GBDLRI Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(11):1191–1210. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(18)30310-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He C., Liu L., Chu Y., et al. National and subnational all-cause and cause-specific child mortality in China, 1996–2015: a systematic analysis with implications for the sustainable development goals. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(2):e186–ee97. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30334-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonten M.J.M., Huijts S.M., Bolkenbaas M., et al. Polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against pneumococcal pneumonia in adults. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1114–1125. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahl B., Sharan A., Deloria Knoll M., et al. National, regional, and state-level burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in children in India: modelled estimates for 2000–15. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7(6):e735–ee47. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30081-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lucero M.G., Dulalia V.E., Nillos L.T., et al. Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines for preventing vaccine-type invasive pneumococcal disease and X-ray defined pneumonia in children less than two years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004977.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitney C.G., Pilishvili T., Farley M.M., et al. Effectiveness of seven-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against invasive pneumococcal disease: a matched case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368(9546):1495–1502. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69637-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lai X., Rong H., Ma X., et al. Willingness to pay for seasonal influenza vaccination among children, chronic disease patients, and the elderly in China: a national cross-sectional survey. Vaccines. 2020;8(3):405. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths U.K., Clark A., Gessner B., et al. Dose-specific efficacy of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(8):1343–1355. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y., Yin Z., Shao Z., et al. Population-based surveillance for bacterial meningitis in China, September 2006–December 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20(1):61–69. doi: 10.3201/eid2001.120375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.UNDP. Report on China's Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals (2000–2015). UNDP https://www.cn.undp.org/content/china/en/home/library/mdg/mdgs-report-2015-.html (accessed June 4 2020).

- 24.Lv M., Fang R., Wu J., et al. The free vaccination policy of influenza in Beijing, China: the vaccine coverage and its associated factors. Vaccine. 2016;34(18):2135–2140. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y., Cheng M., Wang S., et al. Vaccination coverage with the pneumococcal and influenza vaccine among persons with chronic diseases in Shanghai, China, 2017. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):359. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8388-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccination position paper-July 2013: introduction. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2013;88(39):413–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucero M.G., Nohynek H., Williams G., et al. Efficacy of an 11-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine against radiologically confirmed pneumonia among children less than 2 years of age in the Philippines: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(6):455–462. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31819637af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.