Abstract

As a main digestive organ and an important immune organ, the intestine plays a vital role in resisting the invasion of potential pathogens into the body. Intestinal immune dysfunction remains important pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). In this review, we explained the interactions among symbiotic flora, intestinal epithelial cells, and the immune system, clarified the operating mechanism of the intestinal immune system, and highlighted the immunological pathogenesis of IBD, with a focus on the development of immunotherapy for IBD. In addition, intestinal fibrosis is a significant complication in patients with long-term IBD, and we reviewed the immunological pathogenesis involved in the development of intestinal fibrogenesis and provided novel antifibrotic immunotherapies for IBD.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, immune system, immunological pathogenesis, immunotherapy

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) consists of ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), and it affects approximately 6 to 8 million people worldwide.1 As a chronic, progressive, relapsing, or remitting intestinal disorder, IBD has a serious impact on patient’s life quality and activities of daily living, leading to increased healthcare costs. Although it has been widely accepted that IBD is caused by an abnormal immune response against the microorganisms in genetically susceptible individuals, the exact pathogenesis remains largely unexplored.

The currently available therapies for IBD include untargeted therapies (such as amino salicylates, glucocorticoids, and immunomodulators) and targeted biologic therapies (such as anti-TNF, anti-IL-12/IL-23, and anti-α4β7 integrin).2–8 Biologic therapies are effective in many patients, while up to 30% of patients do not response to initial treatment, and the response is lost over time in up to 50% of patients.9

Intestinal fibrosis is a critical complication for patients with long-term IBD. However, the specific molecular mechanisms and pathways involved in the development of intestinal fibrogenesis remain largely unclear, and effective antifibrotic strategies are still unavailable. Therefore, we aimed to summarize the interaction among symbiotic flora, intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), and the immune system, clarify the operating mechanism of the intestinal immune system, and highlight the immunological pathogenesis of IBD, with a focus on the development of the immunotherapy for IBD. In addition, we reviewed the immunological pathogenesis associated with the development of intestinal fibrogenesis, and provide novel anti-fibrotic immunotherapies for IBD.

Intestinal Immune System

Gut Microbiota

The human gut microbiota is constituted by trillions of microorganisms, including fungi, protozoa, viruses, archaea, and predominantly bacteria, which inhabit mainly on the surfaces of the distal ileum and colon.10 Gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IBD by regulating activation of the innate immune system and influencing host energy metabolism, immune homeostasis and maturation, and maintenance of mucosal integrity (Figure 1).11,12 For instance, Clostridium difficile can induce goblet cells and dendritic cells (DCs) to secrete TGF-β and IL-10, thereby generating ample signals to elevate the Treg population.13 Moreover, Bacteroides fragilis can induce the population of Treg population and promote the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines to against colitis.14,15 In addition, gut microbiota can produce essential components, such as vitamin K, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and interfere with the invaded pathogens by competing for space and nutrients.16 Microbiota dysbiosis can be categorized into loss of beneficial organisms and overall microbial diversity and excessive growth of potentially harmful organisms.17 It has been proved that gut dysbiosis is related to various diseases, including IBD.18,19

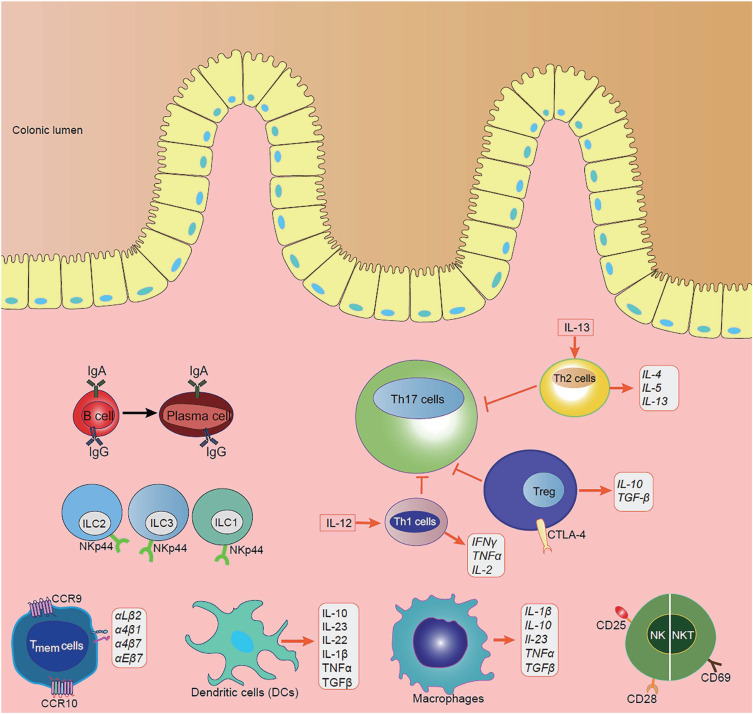

Figure 1.

The disturbance of the immune cell on the progression of IBD.

Accumulating evidence has proved that the composition of gut microbiota is altered in IBD patients.20–22 For example, Parent et al have found that IBD patients have an altered gut microbiota when Pseudomonas-like bacteria are detected in the tissues of CD patients.23 Furthermore, Escherichia coli, as pathogenic bacteria, is increased in the gut, has the capability of surviving and replicating in macrophages, and induces the secretion of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and inflammatory response in IBD.24 In addition, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, as probiotic bacteria, can stimulate DCs to secret anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, and inhibit the production of IL-12 and interferon γ (INF-γ) in the gut, whereas these cytokines were strikingly decreased in the gut of IBD patients.25–27 Although these studies are unable to precisely demonstrate the relationships between microbiota dysbiosis and IBD, they have presented possible effective treatments for IBD. Meanwhile, Britton has colonized germ-free mice with intestinal microbiota from healthy and IBD donors and found that mice receiving feces from IBD donors are more inclined to develop colitis compared with those receiving fecal matter from healthy individuals.28 However, the efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) for the treatment of IBD has not been validated in Clinical trials, since the specific components of donor feces are uncertain.29–31

It has been described that the metabolites of gut microbiota are also altered in IBD patients, such as disrupted bile acid metabolism, decreased tryptophan metabolism levels, reduced SCFAs, and increased levels of nicotinuric acid, taurine, and acylcarnitines.32 Loss of these metabolites through the course of intestinal inflammation may be a driving force for the pathogenesis of IBD. For example, SCFAs, particularly butyrate, acetate, and propionate, have been found to affect diverse biological processes and induce the proliferation of Tregs in the intestine.33,34 Butyrate can especially maintain intestinal epithelial barrier function through inducing actin-binding protein synaptopodin (SYNPO), and serve as the primary fuel source for colonocytes.35 Bile acids and gut microbiota interact mutually. Deficiency in bile acids tends to generate small intestine bacterial overgrowth, activation of inflammation, and gut epithelium damage, suggesting its importance in intestinal antimicrobial defense.36

IECs

The intestinal epithelium is the largest mucosal surface of the human body that acts as a physical and biochemical barrier between luminal contents and the underlying immune system.37 It is constituted of a single layer of different subtypes of specialized IECs, mainly including columnar epithelium, goblet cells, and Paneth cells, which are linked by tight junctions (TJs), and intercalated with immune cells.38 The main functions of the intestinal epithelium include nutrient absorption, physical barrier, and signal respondent to the intestinal microbiota and immune system (Figure 1).9

Goblet cells, as the secretory cells of the intestinal epithelium, can secrete mucins on the luminal surface of the intestinal mucosa (Figure 1).39 The mucus layer provides the first line of defense to prevent large particles and intact bacteria based on the protective function of mucins.40 Many factors, such as microbes, growth factors, neuropeptides, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and toxins, regulate the mucin expression in response to inflammation in colonic mucosa.41 It is observed that the mucin structure is markedly altered in active enterocolitis, and Muc2-knockout mice show decreased mucus secretion and develop spontaneous colitis.42 Parikh has recently found that down-regulation of whey acidic protein four-disulfide core domain 2 (WFDC2), a protein secreted by colonic goblet cells, leads to abnormalities in mucus layer formation, increases colonization and invasion of microbiota, and breakdowns of the epithelial barrier, indicating its potentially protective role in IBD.43

Paneth cells, the special granule-containing cells, find in the epithelial crypts of the small intestine, play an essential role in innate intestinal defenses and the protection of nearby stem cells (Figure 1). They can produce antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), such as alpha-defensins, lysozyme C, phospholipases, C-type lectin, and regenerating islet-derived 3-gamma (RegIIIg), which fight for invaded luminal pathogens.44 It has been demonstrated that AMPs are defective in CD patients.45 Moreover, a recent study has shown that dysbiosis resulting from Paneth cell alpha-defensin misfolding may contribute to the CD pathogenesis, suggesting that Paneth cells are potential therapeutic targets in the future.46

Another essential component of the intestinal epithelium is the apical junctional complex, consisting of the tight junction (TJ), adherens junction (AJ) and desmosome, which seal the IECs tightly to prevent the entry of pathogens and regulate permeability to water, ions and nutrients.47,48 Mutations in genes encoding TJ, and dysfunction of TJ have been elucidated as a crucial pathogenic factor of IBD.49–51 Moreover, some pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IFN-γ, have been shown to increase the permeability of TJs, resulting in the loss of epithelial barrier function and intestinal mucosal inflammation.52,53

Intestinal Immune Cells

Intestinal immune cells can be divided into innate immune cells and adaptive immune cells, both of which greatly contribute to the immune responses in IBD. Innate immune cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, natural killer (NK) cells, and innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), interact together and produce cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial agents to trigger inflammation, leading to phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and activation of the adaptive immune system (Figure 1).54

Macrophages, DCs, neutrophils, NKT cells, and ILCs constitute the first line of defense in the mucosal innate immune system (Figure 1). Macrophages and DCs share the presence of innate immune receptors (pattern-recognition receptors, PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and NOD-like receptors (NLRs), which are important for developing tolerance to certain pathogens and promoting wound healing.55 Binding to these receptors by certain pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of pathogens leads to the activation of several signaling pathways and the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides.56 Moreover, they are antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which link innate immunity and adaptive immunity by secreting cytokines and presenting antigens to the T cells.57,58 Healthy gut resident macrophages, characterized by lack of CD14 expression, manifest decreased response, proliferation, and chemotactic activity.59 However, it has been shown that gut resident macrophages have increased phagocytic activity and secretion of cytokines in IBD patients, triggering dramatic inflammation.60 Gut DCs also remain in a “hyporesponsive and tolerogenic state” in healthy mucosa, and they are activated with high levels of specific TLRs in IBD patients.61 They work by migrating to peripheral lymphoid tissue, where they generate antigen-specific T-cell responses and induce adaptive immune responses. It has been found that blockage of the interactions between DCs and T cells prevents the development of colitis.62 NK cells not only deal with pathogenic infections, but also supervise and kill tumor cells, playing an important role both in innate immunity and adaptive immunity. It has been reported that there exists NK and NKT cells expressing more active immune molecules, such as CD25, CD28, and CD69, in IBD patients.63,64 ILCs have been recognized increasingly over the past decade due to their importance in immune system, which can initiate an early and rapid response to invading pathogens and epithelial damage.65,66 Mature helper ILCs can be categorized into type-1 (ILC1s), type-2 (ILC2s), and type-3 (ILC3s).67 ILC1s are mainly located in the upper gastrointestinal tract, including the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, while ILC2s only make up a small population throughout the whole healthy intestine. On the contrary, NKp44+ ILC3s constitute the main helper ILC population in the lower gastrointestinal tract, including the caecum, ileum, and colon.68,69 Remarkable changes in local ILC populations have been found in inflamed intestine tissues of IBD patients. For example, NKp44+ ILC3s are significantly decreased at sites of active inflammation, while ILC1s, ILC2s, and NKp44- ILC3s are increased in IBD patients, highly suggesting a regulatory or protective role of ILC3s in intestinal inflammation.69–71 Moreover, trans-differentiation of other ILC subtypes into ILC1s is observed in the IL-12-enriched inflamed gut of CD patients.72 In contrast to CD patients, NKp44- ILC3s are highly accumulated in the intestinal tissue of UC patients and correlated with severe illness, making ILC1s and NKp44- ILC3s specifically important in CD and UC, respectively.69

In contrast to the innate immune cells, adaptive immune cells acquire high specificities and immune memory abilities, which supplement each other and eliminate invading pathogens. Key players of the adaptive immune response are T cells (Figure 1). Stimulated by antigens in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) or mesenteric lymph nodes, the naive T cells are activated and differentiated into different subsets, such as effector, regulatory, and memory T cells with up-regulated specific homing receptors, such as chemokine receptors (CCR9 in the small intestine and CCR10 in the colon) and integrins like αLβ2, α4β1, α4β7 and αEβ7.73 The binding of these receptors to cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs) expressed on endothelial cells of the blood vessels allows migration of leukocytes to the inflamed intestine.74 Nowadays, plenty of drugs targeting these receptors have been successfully used in clinical practice to stop leukocyte trafficking to the intestine and prevent inflammation in IBD patients.75–77

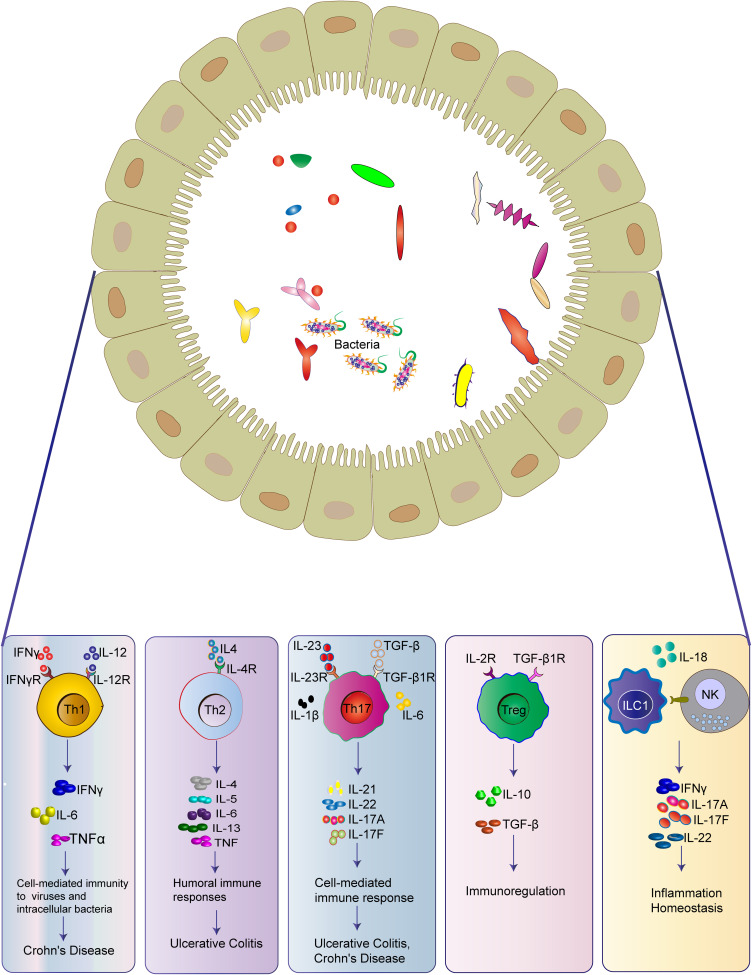

It has been reported that CD is a Th1/Th17-mediated disease, while UC is associated with a Th2-type-like response.78–80 Th1 cells are activated in response to intracellular pathogens, including intracellular bacteria, parasites, and viruses, and mediate cell-mediated immunity and delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions (Figure 1).81 Th1 cells can be induced by IL-12, secrete IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-2, and activate a transcription factor known as STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription-1), leading to up-regulation of transcription factor T-β, and recruitment of macrophages, NK cells, and CD8+ T cells.81,82 Abnormal Th1 responses are thought to be associated with intestinal inflammation. A recent study has demonstrated that Th1-type cytokine TNF-α can synergize with IFN-γ to kill IECs and disrupt gut epithelial barrier function through the CASP8-JAK1/2-STAT1 module.83

Th17 cells are first discovered in 2005 and play a crucial role in protecting the host against extracellular bacterial and fungal infections in the mucosa (Figure 1).84 Th17 cells express the transcription factor RORγt, and produce cytokines, such as IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, and IL-22, and such process is mediated by the activation of STAT3 and induced by TGF-β, IL-6 and IL-23.85,86 IL-21 up-regulates the IL-23 receptor on Th17 cells, activates STAT3, and further up-regulates RORγt, forming a positive autoregulatory feedback loop.87 Th17 cells and their cytokines are important in driving inflammation in IBD. The genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified numerous IBD susceptibility genes related to Th17, including JAK2, STAT3, IL-23R, IL-12B, and CCR6.88,89 Clinical studies have found that the intestinal mucosa and lamina propria of IBD patients contain much higher levels of Th17 cells, IL-17, and IL-23 compared with the healthy controls.90,91 Opposite effects of IL-17A and IL-17F have been demonstrated in experimental IBD models. In the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)/ 2, 4, 6-three nitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) mouse models, deficiencies of IL-17A and IL-17F are shown to be protective against colitis.92,93

Th2 cells are induced by IL-13, which release IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and specialize in eliminating helminth and extracellular microbes.94 Th2 cytokines inhibit the development of Th1 cells and enhance the innate immune response through the activation of macrophages.81 It has been shown that Th2 cytokines are higher in UC compared with the healthy controls (Figure 1).95

Treg cells, expressing the transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), play a negative immunomodulatory role in immune tolerance and an essential role in the pathogenesis of IBD (Figure 1).96,97 They exert regulatory functions by producing anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β, expressing inhibitory molecules, such as cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif domains, and suppressing the immune cell responses.98,99 Treg cells also suppress type-17 immune responses in the gut mucosa by up-regulating RORγt, the transcription factor for Th17 cells and ILC3s.100 They not only restrain effector T cell functions, but also control intestinal inflammation.60 In vivo and in vitro studies have found decreased Treg cells in the peripheral blood of UC mouse model and the intestinal mucosa of IBD patients, whereas IBD symptoms can be ameliorated by increasing the secretion of Treg-type cytokines.101,102 However, some studies found that Treg cells in the intestine fail to alleviate inflammation, which is correlated with the intestinal microenvironment.98,103 Moreover, Treg cells can be transformed into Th17 cells in the presence of IL-6, which is important in the onset of intestinal inflammation.104

Memory T cells are characterized by increased expressions of CD69 and CD103 in the gut mucosa.105 The memory T cells can position at key barrier surfaces, such as skin, intestinal, and respiratory mucosa, and mitigate the microbial load in the earliest phase of infection by directly recognizing antigen, augmenting innate immunity, and recruiting circulating memory T cells.106 Tissue-resident immune cells may play a pathogenic role in inflammatory diseases because of memory T cells activated, poised state, and the anatomical location at barrier surfaces (Figure 1).107 It has been reported that the number of memory T cells is increased in both UC and CD.108

B cells are capable of presenting antigens, producing antibodies, and secreting cytokines, which are critical to intestinal immune homeostasis (Figure 1).109 Intestinal B cells can differentiate into plasma cells and secrete IgG and IgA, which limits intestinal inflammation.110,111 They also modulate the effector response and produce anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10.112 It has been reported that IgG and IgA responses are elevated in IBD patients.113,114 Some studies have shown the ineffectiveness of rituximab (anti-CD20 antibody) in inducing remission in active UC,115 while others show IgG predominance and IgA deficiency in IBD-inflamed gut tissues,114,116 which comes up with the potential therapeutic approaches of targeting IgG-producing plasma cells or shifting the imbalance of IgG and IgA in the inflamed tissues.

Immunological Pathogenesis of IBD

STAT3-Inducing Cytokines (IL-22 and IL-6)

IL-22 is a pleiotropic cytokine, and secreted by Th22, Th17, and Th1 cells, which activates STAT3 to promote intestinal tissue repair and restrain intestinal pathogens (Figure 2) (Table 1).117 It is widely expressed in the small intestine and hardly detected in the large intestine, which can be induced by signals from commensal microbiota in IBD.118 Moreover, IL-22 not only promotes the expressions of IBD-susceptibility genes, such as fut2, sec1, bcl2115, and ptpn22,119 but also induces the expression of deleted in malignant brain tumor 1 (DMBT1) to promote epithelial cell differentiation.120 In addition, epithelial cell regeneration is activated through the IL-22-STAT3-dependent pathway.121

Figure 2.

The crucial crosstalk between immune cells and epithelial cells in the gut.

Table 1.

The Cytokines of Immunological Pathogenesis of IBD

| Cytokines | Cells Secreting Cytokines | Influence on the Inflammation | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-22 | Th22, Th17, Th1 cells | Pleiotropic function | Promote intestinal tissue repair and restrain intestinal pathogens Promoting IBD-susceptibility genes expression |

[117] |

| IL-6 | Macrophages, DCs | Pro-inflammatory | Activating CD4+ T cells and STAT-3 signaling pathway | [122, 123] |

| IL-12/IL-23 | DCs | Pro-inflammatory | Promoting the differentiation ofTh17 cells | [125] |

| IL-17 | Th17 | Pro-inflammatory | Promoting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines | [84] |

| IL-10 | Treg, macrophages, DCs | Anti-inflammatory | Inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and macrophage-ROS-NO axis | [131] |

| IL-1β/IL-18 | Macrophages | Pro-inflammatory | Promoting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines | [141] |

| TNF | Monocytes, macrophages, T cells | Pro-inflammatory | Promoting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines Activating JNK pathway and NF-κB signaling pathway |

[146] |

Abbreviations: TNF, tumor necrosis factor; IL, interleukin; DCs, dendritic cells, Treg, regulatory T cells; STAT-3, signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NO, nitric oxide; JNK, Jun N-terminal kinase; NF-κB, nuclear factor kappa B.

IL-6 is mainly produced by macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs) in lamina propria (Figure 2) (Table 1). It has been found that the level of IL-6 is increased in the serum and intestine of CD patients, which is related to the clinical disease activity, frequency of relapses, and the severity of inflammation.122,123 After binding to its receptor, IL-6 activates gp130-positive T cells and leads to the translocation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT-3), subsequently activating transcription of the anti-apoptotic genes Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl.124 Therefore, the humanized anti-IL-6R monoclonal antibody, tocilizumab, has been emerged for the treatment of IBD, which will be elucidated in the last part.

IL-12/IL-23 Pathway

IL-12 and IL-23, produces by DCs, both belong to the IL-12 family, and plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases125 (Figure 2) (Table 1). In several models of colitis, pathogenic T cell responses are driven by IL-12 and IL-23.126 IL-12 is composed of the p40 and IL-12p35 subunits and signals through the IL-12Rβ1 and IL-12Rβ2 subunits. It can promote the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into IFN-γ producing Th1 cells and the proliferation and effector functions of NK cells, NKT cells, and cytotoxic T cells.127 IL-23 is composed of IL-23p19 and p40 subunits, and it signals through IL-12Rβ1 and IL-23R.128 IL-23 exerts its biological function by reinforcing and shaping the Th17 cell response,129 while it also antagonizes anti-inflammatory Foxp3+ Treg cell responses to promote intestinal inflammation.130

IL-17 Cytokines

IL-17 cytokines, including IL-17A and IL-17F, also play an important role in the pathogenesis of IBD, which has been elucidated in the part of intestinal immune cells (Figure 2) (Table 1).

Il-10

IL-10 acts as the most important cytokine for suppressing pro-inflammatory responses in the immune system and can be produced by a large number of different types of cells, including Tregs, macrophages, DCs, and so on (Figure 2) (Table 1).131 IL-10 receptors, IL-10Rα and IL-10Rβ, are commonly expressed on most immune cells, so that IL-10 can regulate different innate and adaptive immune cells to exert its functions.132 Mutations in IL-10R subunit genes are related to intestinal hyperinflammatory immune responses in the early onset of IBD patients.133 Indeed, both IL-10- and IL-10R-deficient mice can develop spontaneous colitis.134,135 Inactivation of c-MAF in Treg cells results in the dysfunction of IL-10 production, thus developing spontaneous colitis.136 IL-10 inhibits IFN-γ production by Th1 cells in mice transferred with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells, reduces Th17 responses in the dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) model, and enables Treg cells to suppress pathogenic Th17 cell responses in colitis.137–139 IL-10 also functions through the macrophage-ROS-NO axis in the DSS-induced colitis model.140

IL-1β Family Cytokines IL-1β and IL-18

IL-1β is a type of pro-inflammatory cytokine secreted by macrophages, which acts synergistically with other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and IL-6, to induce IBD inflammation (Figure 2) (Table 1).141 Liu et al have found that IL-1β secretion is increased in IL-10 deficient mice before the spontaneous onset of colitis.142 Siegmund et al have found that deletion of the inflammasome component caspase-1 prevents the release of IL-1β and IL-18 and ameliorates DSS-induced colitis in mice.143 Moreover, genetic deficiency or inhibition of IL-1β and IL-18 signaling alleviates experimental colitis.144,145

TNF and TNF Like Ligand 1A (TL1A)

TNF, secreted by monocytes, macrophages, and T cells, has been recognized as a pro-inflammatory cytokine in the pathogenesis of IBD (Figure 2) (Table 1).146 It can stimulate the acute phase response, promote the secretions of IL-1 and IL-6, and increase the expressions of adhesion molecules.147 Three pathways can be activated by the binding of TNF-α to its receptor, including apoptosis pathway, JNK pathway, and NF-κB pathway. It has been found that TNF-α is significantly elevated in the blood, epithelial tissue, and stool of active IBD patients, and its level is correlated with the clinical disease activity of CD patients.148 Blockade of TNF-α signaling by anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) has become an important treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe refractory IBD.146

TL1A, a member of the TNF family, has also been found to be a crucial mediator of intestinal inflammation, and its level is also increased in IBD patients.149 TL1A exerts its function by mainly binding to death domain receptor 3 (DR3) and co-localizes to antigen-presenting cells and T cells in the intestine.150 TL1A can also synergistically promote the production of IL-4, IL-12, and IL-23 and increase the expression of DR3 by Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells to promote inflammation.149,151

Immune Cell Trafficking

Immune cell trafficking to the gut to initiate and maintain immune responses is crucial pathogenesis of IBD, of which T cell trafficking is the most important one (Figure 2).152 The complete process of immune cell trafficking includes tethering, rolling, activation, adhesion, and extravasation, which involves various integrins, selectins, chemokines, and their ligands or receptors. Recognition of the cognate antigens in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue leads to T cell activation, proliferation, and upregulation of adhesion molecules, such as integrin α4β7, α4β1, β2 integrins, and CCR9 for small intestinal homing, and integrin α4β7, and GPR15 for migration to the colon.153–155 Tethering and rolling are mediated by low-affinity binding of CD62L (L-selectin) and integrins (α4β7 and α4β1) on T cells to glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion molecule-1 (GlyCAM-1), mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1(VCAM-1) on endothelial cells, which slows down the exposure of cells to a chemokine gradient.156,157 After being activated, the T cell changes to its active conformation and adheres to the endothelial wall via interaction of integrin and its ligands (β2 integrin heterodimers to ICAM-1, α4β1 to VCAM-1 and α4β7 to MAdCAM-1), followed by firm arrest and extravasation to the tissue.158 T cells either retain in the tissue or recirculate back to the blood and lymph via sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) and S1P receptors (S1PRs).159,160 Numerous therapies targeting different steps of immune cell trafficking have been evolved, which will be introduced in the last part.

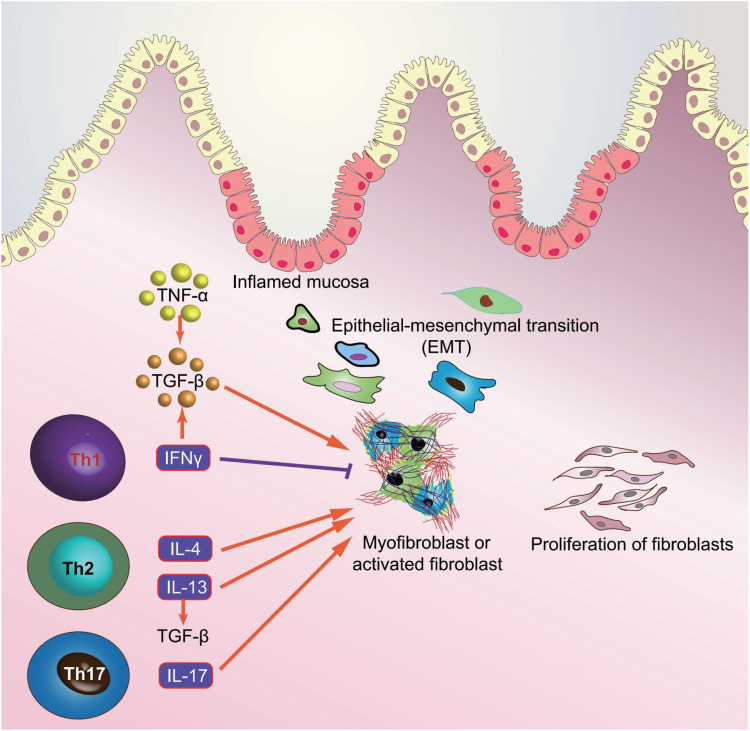

Immunological Pathogenesis of Intestinal Fibrosis in IBD

Intestinal fibrosis is a severe and common complication of IBD with approximately >30% of patients in CD and 5% patients in UC, which can contribute to intestinal obstruction and surgical resection.161,162 Intestinal fibrosis is characterized by chronic, recurrent or unsolved, intestinal inflammation, contributing to an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) and loss of normal function.163,164 Although great progress has been made in the understanding of the pathogenesis of IBD, the specific cellular and molecular fibrosis pathways remain undetermined.163,165,166 Therefore, we, in this part, mainly described the molecular mechanisms underlining the pathogenesis of intestinal fibrogenesis and provide new therapeutic targets in IBD (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Interactions between the gut immune system and intestinal fibroblasts.

Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) Signaling Pathway

TGF-β signaling pathway plays a critical role in the development of intestinal fibrosis, and both TGF-β and its receptors are particularly overexpressed in intestinal cells of fibro-stenotic CD and in animal models of intestinal fibrosis.167,168 The canonical TGF-β signaling pathway is mediated by Smad proteins as TGF-β receptor activation phosphorylates Smad2 and Smad3, which then form a complex with Smad4, ultimately translocating into nucleus to regulate the transcription of TGF-β target genes169 (Figure 3). Moreover, the expressions of TGF-β at the transcription level and phosphorylated Smad2/3 were elevated in the mucosa overlying strictures than in mucosa overlying non-strictures areas in CD patients.167 The activated TGF-β signaling pathway exerts several effects with regards to intestinal fibrosis through differentiating from fibroblasts to myofibroblasts, promoting the production of ECM, and inhibiting the expressions of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).164 However, Smad6 and Smad7 can inhibit the TGF-β signaling pathway via competing with Smad2 and Smad3 for TGF-β receptors.170 Additionally, Smad7 downregulation and Smad2/3 upregulation detected in intestinal strictures of CD, implying the pro-fibrogenic role of the TGF-β signaling pathway.167 Nevertheless, blockade of TGF-β signaling pathway, either by increasing Smad7 expression, or decreasing Smad2/3, can reduce intestinal fibrosis, providing an effective therapeutic strategy targeting the TGF-β signaling pathway in the intestinal fibrosis of IBD in the future.

IL-17 Cytokines

IL-17 cytokines are primarily produced by Th17 cells and composed of six related proteins: IL-17A, IL-17B, IL-17C, IL-17D, IL-17E, and IL-17F, which play an important role in the promotion of chemokine production for granulocyte activation and inflammatory response (Figure 3).171 With regards to their role in intestinal fibrosis, both human and animal data suggest that IL-17A is significantly over-expressed in the strictured areas of CD compared with the non-strictured area, which suppresses myofibroblast migration and elevates the production of collagen and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP).172 Moreover, in subepithelial myofibroblast, IL-17A can promote the production of heat shock protein 47 (HSP47) and collagen, which are prominently over-expressed in the intestinal tissues of the patients with active CD, and in turn, result in the expression of IL-17A-induced collagen I.173 In TNBS-induced intestinal fibrosis mice model, blockade of IL-17A with anti-IL-17A antibody can ameliorate intestinal fibrosis by decreasing the expressions of profibrogenic cytokines, such as TGF-β, TNF-α, and IL-1β, and decrease the production of collagen.174 Unfortunately, Secukinumab, as a human anti-IL-17A monoclonal antibody, not only has no therapeutic effect in patients with moderate to severe CD, but also accompanies with serious adverse events, including fungal infections, in a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial.175 Therefore, the IL-17-involved mechanism underlying intestinal fibrosis in IBD might be complex and needs further research.

TNF-α

TNF-α is universally detected in IBD and closely associated with intestinal fibrosis through promoting myofibroblast proliferation and collagen accumulation176 (Figure 3). Moreover, TNF-α can also promote the expressions of TGF-β and TIMP-1 in colonic epithelial cells and elevate the levels of MMP-9 in colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts.177 In addition, TNF-α superfamily members, TNF-like cytokine 1A (TL1A) and TNF superfamily member 15 (TNFSF15), play both pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrogenic roles in the pathogenesis of IBD, which are increased in IBD mucosa and contribute to collagen accumulation in colon.178,179 In CD mouse model, CNTO1081, as a rat-specific anti-TNF-α antibody, targets at blocking TNF-α and effectively prevents the development of intestinal fibrosis.180 In clinical trial, however, infliximab (IFX), a human TNF-α antibody, can not prevent the development of intestinal stricture, rather than longer duration of CD, more severe CD, and isolated small bowel disease was related with intestinal stricture.181 In addition, a multi-center inception cohort study has demonstrated that CD patients administered anti-TNF-α antibody, IFX, have less penetrating complication but not stricture complication compared with those do not receive anti-TNFα.182 Until now, it is generally suggested that the anti-TNF-α antibody cannot attenuate intestinal fibrosis in IBD.

T Helper (Th) 2 Cytokines

Th2 cytokines are consisted of IL-4 and IL-13 and secreted by Th2 cells, which are overexpressed in fibrotic disease, and facilitating fibroblast activation, proliferation, and collagen accumulation.183 Moreover, IL-13 signals can bind with IL-4Rα/IL-13Rα1 receptor and exert a pro-fibrotic effect in experimental model of fibrosis, including IBD.184 Furthermore, IL-13 signaling can elevate the expression of TGF-β and promote intestinal fibrosis by combining with IL-13Rα2 receptor, whereas blockade of IL-13 signaling can suppress the levels of TGF-β and intestinal fibrosis.185,186 However, in IBD, the function and underlying mechanism of IL-4 involved in intestinal fibrosis remain obscure. Although the levels of IL-4 in intestinal mucosa in both CD and UC patients are not detected, blockade of IL-4 can contribute to a striking remission of oxazolone colitis in mouse model.187 Nevertheless, the data from anti-IL-4/IL-13 antibodies in clinical application for IBD are limited. In a randomized multi-center study, anrukinzumab, a human anti-IL-13 antibody, does not have a statistically significant therapeutic effect in patients with active UC compared with placebo.188 Therefore, it is necessary to further confirm the potential role of anti-IL4/IL-13 antibodies in the intestinal fibrosis of IBD.

Th1 Cytokines

Th1 cytokine includes INF-γ, and is released by Th1 cells, which has an antifibrotic effect through suppressing fibroblast proliferation and migration.189,190 INF-γ can inactivate the TGF-β signaling pathway via inducing phosphorylation of Smad3 and increasing the levels of Smad7.191 Although several other models have found that INF-γ has a potent effect on anti-fibrogenesis, clinical studies involved in its therapeutic potential of intestinal fibrosis in IBD remain limited.192,193

Immunotherapy of IBD

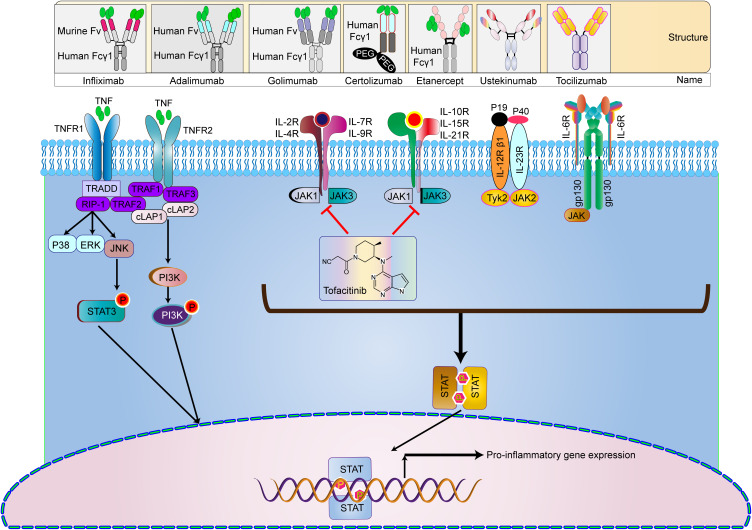

Despite the advancements in the knowledge of mechanisms underlying intestinal fibrosis in IBD, there is still no effective antifibrotic therapy until now. The relationship between intestinal inflammation and fibrosis is closely associated. Therefore, the strategies for the treatment of IBD (such as biological agents) may relieve intestinal fibrosis.162 Moreover, biological agents are effective in inducing and maintaining clinical remission of IBD and promoting mucosal healing. At present, seven biological agents have been officially approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of IBD, as described in the Figure 4. A number of clinical trials of innovative drug candidates for the treatment of IBD are underway. We listed the clinical trials in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Currently approved and available immunotherapy strategies for IBD include: four TNF antibody drugs infliximab, Adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab. Ustekinumab is human monoclonal IgG antibodies that block the p40 subunit receptor of the IL-12/23 complex. Tofacitinib is a JAK inhibitor in the JAK/STAT pathway.

Table 2.

Selected Immunotherapy in IBD

| Therapeutic Drug | Disease | Targeted Cytokine or Pathway | Clinical Trials Phase | ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier (NCT Number) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recombinant IFNβ | UC | IFNβ | Phase II | NCT00616434 |

| Anrukinzumab and tralokinumab | UC | IL-13 | Phase II | NCT01284062 |

| Vedolizumab IV | UC and CD | TNF-α | Phase IV | NCT04804540 |

| Ustekinumab | UC | IL-12/23p40 | Phase III | NCT04963725 |

| CT-P13/AVX-470 | UC and CD | TNF-α | Phase III/I | NCT02539368 |

| Tocilizumab | CD | IL-6R | Phase II | NCT01287897 |

| Secukinumab | CD | IL-17A | Phase II | NCT03568136 |

| Vedolizumab | CD | α4β7 | Phase III | NCT02038920 |

| ABX464 | CD | miR-124 | Phase II | NCT03905109 |

| Tofacitinib | UC | JAK | PhaseIII | NCT03281304 |

| Ontamalimab | UC | MAdCAM-1 | PhaseIII | NCT03290781 |

| Adalimumab, Certolizumab pegol, Infliximab, Golimumab | UC and CD | TNF-α | Phase II | NCT00409617 |

| Brazikumab, Risankizumab, Brazikumab, Guselkumab, Mirkizumab | UC and CD | IL-23p19 | PhaseIII/II | NCT03759288 |

| Recombinant IL-10 | UC | IL-10 | Phase II | NCT00729872 |

| Recombinant IL-11 | CD | IL-11 | Phase II | NCT00040521 |

| Recombinant IFNβ | UC | IFNβ | Phase II | NCT00303381 |

| Recombinant IGF-1 (rhIGF, Increlex) | CD | IGF-1 | PhaseIII/II | NCT00764699 |

| SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotides | CD | TGFβ-SMAD7 | Phase III | NCT02641392 |

| Etrolizumab | Severe UC and CD | α4β7 and αEβ7 integrin | Phase III |

NCT02403323 NCT02394028 |

| Abrilumab | Severe UC | α4β7 integrin | Phase II | NCT01694485 |

| Natalizumab | Severe CD | α4β1 and α4β7 integrins | Phase III | NCT00078611 |

| Alicaforsen (antisense oligonucleotide drug) | CD | Intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1) | Phase III | NCT00048113 |

Abbreviations: UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

Targeting TNF-α

Anti-TNF antibodies have been widely used for approximately 25 years. For now, four TNF-α inhibitors have been approved for clinical use, including IFX, adalimumab (ADL), golimumab (GOLI), and certolizumab pegol (CZP). IFX can induce the healing of mucosal ulcers. It is the first treatment approved for perianal fistulas in CD and proved to be effective in both CD and UC (Figure 4).194 Maintenance treatment is superior to episodic treatment.8 Unlike IFX, ADL is first tested and approved for the treatment of methotrexate (MTX)-refractory rheumatoid arthritis (RA).2 It induces mucosal healing in CD as early as 12 weeks of treatment. It is also effective in both CD and UC, as well as in CD patients who lose response to IFX.8 Although anti-TNF therapy shows clinical effectiveness, 10–30% of IBD patients do not respond, and 20–40% of patients lose their response over time.126 CZP is only developed for CD in two Phase III trials and approved for the treatment of CD in the USA but not in Europe (except for Switzerland), while GOLI is approved and marketed as Simponi at maintenance doses of 100 mg every 4 weeks in the USA and 50 mg every 4 weeks in Europe.6

Targeting IL-12/IL-23

Ustekinumab is the monoclonal antibody directed against the p40 subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, and it has shown a positive effect in the treatment of IBD (Figure 4).5 It is currently the only anti-IL-23 therapy approved by the FDA. Another more specific target is against the p19 subunit of IL-23, which also shows clinical effectiveness, including risankizumab,195 brazikumab,196 guselkumab,197 and mirikizumab.198 However, they are still undergoing clinical trials.

Targeting JAKs

The Janus kinase (JAK) family contains four intracellular tyrosine kinases: JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and non-receptor tyrosine-protein kinase 2, which activate STAT pathway and play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of IBD (Figure 4).4 Currently, 10 JAK inhibitors have been evaluated for the clinical efficacy for IBD, whereas Tofacitinib is the only one with clinical efficacy and is approved for the clinical treatment of UC.7,199,200

Targeting Cell Adhesion Molecules

As the essential mediators of T cell recruitment and intestinal inflammation, cell adhesion molecules serve as promising targets for IBD (Figure 4). For example, the anti-α4β7 integrin antibody vedolizumab and anti-a4 integrin antibody natalizumab have shown great efficacy in the treatment of IBD, which are currently approved and widely used in clinical practice.3,201 Etrolizumab (an IgG1 monoclonal antibody selectively binding the β7 subunit), abrilumab (an IgG2 monoclonal antibody blocking the α4β7 integrin) and ontamalimab (a monoclonal IgG2 humanized antibody targeting MAdCAM-1) are also effective in pre-clinical data but still undergoing clinical trials.202–204

Targeting NLRP3 Inflammasome

Elevated levels of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pro-inflammatory cytokines are the main pathological mechanism of IBD. It has been observed that CD patients have high levels of the NLRP3 inflammasome.142 Moreover, activated NLRP3 inflammasome can promote excess IL-1β production and alter TJ expression in the colonic epithelium, thus accelerating disease progression.205 Therefore, targeting NLRP3 inflammasome provides a promising strategy for IBD therapy (Figure 4). Various types of innovative drugs that target the NLRP3 inflammasome can be reasonably developed for IBD treatment, including direct and indirect inhibitors, some old drugs, and naturally sourced medicines, which have shown great efficacy in experimental models.206–209 However, the development of targeting agents still has a long way to go before they reach clinical applications for IBD therapy.

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In this review, we clarified the interactions of different components in the intestinal immune system and summarized the currently found immunological pathogenesis and the relative immunotherapies in intestinal fibrosis and IBD. Over the past several decades, the immunological mechanisms of IBD have made great advancements, providing new strategies for the treatment of IBD. However, the immunological mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of intestinal fibrosis are still obscure. Therefore, in-depth understanding of molecular mechanisms that underlie the pathogenesis of fibrosis is critical and may pave the way for the development of anti-fibrotic drugs for IBD.

It has long been accepted that adaptive immune responses play a central role in the pathogenesis of IBD. Although T cell response is the key driver of intestinal inflammation in IBD, the specific interaction and contribution of different T cells should be further elucidated. On the other hand, the inherent defects in innate immunity in IBD have been increasingly raised concerns. The utilization of technological innovations and model systems and the development of reliable biomarkers to predict response may help us better understand the heterogeneity and complexity of IBD.

In the past decades, the field of IBD genetics has made great progress, and numerous relative molecular and cellular pathways have been found. Alterations in specific gene loci can be promising therapeutics for IBD in the future. Moreover, FMT, naturally sourced or derived medicines, novel antibodies or inhibitors, combined treatment programs, and multifactor blockers are also expected to break the bottleneck of therapeutics of IBD. In addition, therapeutic strategies combining the use of drugs with anti-inflammatory actions and drugs with antifibrotic actions will provide great insights into the current treatment of IBD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2018A0303100024), Three Engineering Training Funds in Shenzhen (No. SYLY201718, No. SYJY201714 and No. SYLY201801), Technical Research and Development Project of Shenzhen (No. JCYJ20150403101028164, No. JCYC20170307100911479, No. JCYJ20190807145617113 and JCYJ20210324113802006), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81800489).

Abbreviation

IBD, Inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; SYNPO, synaptopodin; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; TJs, tight junctions; WFDC2, Whey acidic protein four-disulfide core domain 2; AMPs, antimicrobial peptides; TNF-a, tumor necrosis factor a; DCs, dendritic cells; NK, natural killer; ILCs, innate lymphoid cells; TLRs, Toll-like receptors; NLRs, Nod-like receptors; PAMPs, pathogen associated molecular patterns; APCs, antigen-presenting cells; GALT, gut-associated lymphoid tissue; CAMs, cellular adhesion molecules; STAT3, transcriptional activation factor 3; GWAS, genome-wide association studies; FOXP3, factor forkhead box P3; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4; ECM, extracellular matrix; TGF-β, Transforming growth factor-β; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TIMP1, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; TL1A, TNF-like cytokine 1A; TNFSF15, TNF superfamily member 15; INF-γ, interferon gamma.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Hodson R. Inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2016;540(7634):S97. doi: 10.1038/540S97a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boland BS, Sandborn WJ, Chang JT. Update on Janus kinase antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:603–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Gasink C, et al. Ustekinumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1946–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berends SE, Strik AS, Jansen JM, et al. Pharmacokinetics of golimumab in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: the GO-KINETIC study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54:700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandborn WJ, Nguyen DD, Beattie DT, et al. Development of gut-selective Pan-Janus kinase inhibitor TD-1473 for ulcerative colitis: a translational medicine programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1202–1213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Haens GR, van Deventer S. 25 years of anti-TNF treatment for inflammatory bowel disease: lessons from the past and a look to the future. Gut. 2021;70:1396–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang X, Yang MF, Fan W, et al. Bioinformatic analysis suggests that three hub genes may be a vital prognostic biomarker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Comput Biol. 2020;27(11):1595–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shastry RP, Rekha PD. Bacterial cross talk with gut microbiome and its implications: a short review. Folia Microbiol (Praha). 2021;66(1):15–24. doi: 10.1007/s12223-020-00821-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavelle A, Sokol H. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites as key actors in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(4):223–237. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0258-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumar S, Kumar A. Microbial pathogenesis in inflammatory bowel diseases. Microb Pathog. 2021;163:105383. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2021.105383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khanna S. Management of Clostridioides difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Intest Res. 2021;19(3):265–274. doi: 10.5217/ir.2020.00045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.An D, Oh SF, Olszak T, et al. Sphingolipids from a symbiotic microbe regulate homeostasis of host intestinal natural killer T cells. Cell. 2014;156:123–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Troy EB, Kasper DL. Beneficial effects of Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharides on the immune system. Front Biosci. 2010;15:25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lozupone CA, Stombaugh JI, Gordon JI, et al. Diversity, stability and resilience of the human gut microbiota. Nature. 2012;489:220–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carding S, Verbeke K, Vipond DT, et al. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disease. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2015;26:26191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hold GL, Smith M, Grange C, et al. Role of the gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: what have we learnt in the past 10 years? World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1192–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeGruttola AK, Low D, Mizoguchi A, et al. Current understanding of dysbiosis in disease in human and animal models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1137–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank DN, St Amand AL, Feldman RA, et al. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13780–13785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker AW, Sanderson JD, Churcher C, et al. High-throughput clone library analysis of the mucosa-associated microbiota reveals dysbiosis and differences between inflamed and non-inflamed regions of the intestine in inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manichanh C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, et al. Reduced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut. 2006;55:205–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parent K, Mitchell P. Cell wall-defective variants of pseudomonas-like (group Va) bacteria in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:368–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chervy M, Barnich N, Denizot J. Adherent-invasive E. coli: update on the lifestyle of a troublemaker in Crohn’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:3734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lloyd-Price J, Arze C, Ananthakrishnan AN, et al. Multi-omics of the gut microbial ecosystem in inflammatory bowel diseases. Nature. 2019;569:655–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:16731–16736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossi O, van Berkel LA, Chain F, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii A2-165 has a high capacity to induce IL-10 in human and murine dendritic cells and modulates T cell responses. Sci Rep. 2016;6:18507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Britton GJ, Contijoch EJ, Mogno I, et al. Microbiotas from humans with inflammatory bowel disease alter the balance of gut Th17 and RORgammat(+) regulatory T cells and exacerbate colitis in mice. Immunity. 2019;50:212–224 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:156–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1218–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rossen NG, Fuentes S, van der Spek MJ, et al. Findings from a randomized controlled trial of fecal transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:110–118 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu S, Zhao W, Lan P, et al. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to therapy. Protein Cell. 2021;12:331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalile B, Van Oudenhove L, Vervliet B, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:461–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown EM, Kenny DJ, Xavier RJ. Gut microbiota regulation of T cells during inflammation and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2019;37:599–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li F, Xiong F, Xu ZL, et al. Polyglycolic acid sheets decrease post-endoscopic submucosal dissection bleeding in early gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Banfi D, Moro E, Bosi A, et al. Impact of microbial metabolites on microbiota-gut-brain axis in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:9–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kurashima Y, Kiyono H. Mucosal ecological network of epithelium and immune cells for gut homeostasis and tissue healing. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35:119–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johansson ME, Gustafsson JK, Holmen-Larsson J, et al. Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63:281–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martini E, Krug SM, Siegmund B, et al. Mend your fences: the epithelial barrier and its relationship with mucosal immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;4:33–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorofeyev AE, Vasilenko IV, Rassokhina OA, et al. Mucosal barrier in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:431231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn AC, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:117–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parikh K, Antanaviciute A, Fawkner-Corbett D, et al. Colonic epithelial cell diversity in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2019;567:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pott J, Hornef M. Innate immune signalling at the intestinal epithelium in homeostasis and disease. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:684–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arijs I, De Hertogh G, Lemaire K, et al. Mucosal gene expression of antimicrobial peptides in inflammatory bowel disease before and after first infliximab treatment. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu Y, Nakamura K, Yoshii A, et al. Paneth cell alpha-defensin misfolding correlates with dysbiosis and ileitis in Crohn’s disease model mice. Life Sci Alliance. 2020;3. doi: 10.26508/lsa.201900592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramanan D, Cadwell K. Intrinsic defense mechanisms of the intestinal epithelium. Cell Host Microbe. 2016;19:434–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marchiando AM, Graham WV, Turner JR. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Pathol. 2010;5:119–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Sadi R, Nighot P, Nighot M, et al. Lactobacillus acidophilus induces a strain-specific and toll-like receptor 2-dependent enhancement of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier and protection against intestinal inflammation. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:872–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeissig S, Burgel N, Gunzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2007;56:61–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown EM, Sadarangani M, Finlay BB. The role of the immune system in governing host-microbe interactions in the intestine. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:660–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su L, Nalle SC, Shen L, et al. TNFR2 activates MLCK-dependent tight junction dysregulation to cause apoptosis-mediated barrier loss and experimental colitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:407–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ma TY, Boivin MA, Ye D, et al. Mechanism of TNF-{alpha} modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G422–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Knutson CG, Mangerich A, Zeng Y, et al. Chemical and cytokine features of innate immunity characterize serum and tissue profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2332–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, et al. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wallace KL, Zheng LB, Kanazawa Y, et al. Immunopathology of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geremia A, Biancheri P, Allan P, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holleran G, Lopetuso L, Petito V, et al. The innate and adaptive immune system as targets for biologic therapies in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Smith PD, Ochsenbauer-Jambor C, Smythies LE. Intestinal macrophages: unique effector cells of the innate immune system. Immunol Rev. 2005;206:149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hart AL, Al-Hassi HO, Rigby RJ, et al. Characteristics of intestinal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:50–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Malmstrom V, Shipton D, Singh B, et al. CD134L expression on dendritic cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes drives colitis in T cell-restored SCID mice. J Immunol. 2001;166:6972–6981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lai LJ, Shen J, Ran ZH. Natural killer T cells and ulcerative colitis. Cell Immunol. 2019;335:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huang Y, Chen Z. Inflammatory bowel disease related innate immunity and adaptive immunity. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:2490–2497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nagasawa M, Spits H, Ros XR. Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILCs): cytokine hubs regulating immunity and tissue homeostasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a030304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mjosberg J, Spits H. Human innate lymphoid cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138:1265–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vivier E, Artis D, Colonna M, et al. Innate lymphoid cells: 10 years on. Cell. 2018;174:1054–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kramer B, Goeser F, Lutz P, et al. Compartment-specific distribution of human intestinal innate lymphoid cells is altered in HIV patients under effective therapy. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Forkel M, van Tol S, Hoog C, et al. Distinct alterations in the composition of mucosal innate lymphoid cells in newly diagnosed and established Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bernink JH, Peters CP, Munneke M, et al. Human type 1 innate lymphoid cells accumulate in inflamed mucosal tissues. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Creyns B, Jacobs I, Verstockt B, et al. Biological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients partly restores intestinal innate lymphoid cell subtype equilibrium. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schulz-Kuhnt A, Wirtz S, Neurath MF, et al. Regulation of human innate lymphoid cells in the context of mucosal inflammation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu Z, Zou Q, Su B. Regulation of T cell immunity by cellular metabolism. Front Med. 2018;12:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arseneau KO, Cominelli F. Targeting leukocyte trafficking for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97:22–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jovani M, Danese S. Vedolizumab for the treatment of IBD: a selective therapeutic approach targeting pathogenic a4b7 cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14:1433–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Muhl L, Becker E, Muller TM, et al. Clinical experiences and predictors of success of treatment with vedolizumab in IBD patients: a cohort study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Tyrrell H, et al. Etrolizumab for the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: an overview of the phase 3 clinical program. Adv Ther. 2020;37:3417–3431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sakuraba A, Sato T, Kamada N, et al. Th1/Th17 immune response is induced by mesenteric lymph node dendritic cells in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1736–1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bouma G, Strober W. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Raphael I, Nalawade S, Eagar TN, et al. T cell subsets and their signature cytokines in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2015;74:5–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Caza T, Landas S. Functional and Phenotypic Plasticity of CD4(+) T Cell Subsets. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:521957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Woznicki JA, Saini N, Flood P, et al. TNF-alpha synergises with IFN-gamma to induce caspase-8-JAK1/2-STAT1-dependent death of intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harrington LE, Hatton RD, Mangan PR, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, et al. The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14:585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zhao J, Lu Q, Liu Y, et al. Th17 cells in inflammatory bowel disease: cytokines, plasticity, and therapies. J Immunol Res. 2021;2021:8816041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Diaz Pena R, Valdes E, Cofre C, et al. Th17 response and autophagy–main pathways implicated in the development of inflammatory bowel disease by genome-wide association studies. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Franke A, McGovern DP, Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kobayashi T, Okamoto S, Hisamatsu T, et al. IL23 differentially regulates the Th1/Th17 balance in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2008;57:1682–1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rovedatti L, Kudo T, Biancheri P, et al. Differential regulation of interleukin 17 and interferon gamma production in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2009;58:1629–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang Z, Zheng M, Bindas J, et al. Critical role of IL-17 receptor signaling in acute TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:382–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang XO, Chang SH, Park H, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by IL-17F. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1063–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Di Sabatino A, Biancheri P, Rovedatti L, et al. New pathogenic paradigms in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:368–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Strober W, Fuss IJ. Proinflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1756–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Galvez J. Role of Th17 cells in the pathogenesis of human IBD. ISRN Inflamm. 2014;2014:928461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Maul J, Loddenkemper C, Mundt P, et al. Peripheral and intestinal regulatory CD4+ CD25(high) T cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1868–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mayne CG, Williams CB. Induced and natural regulatory T cells in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1772–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wing JB, Tanaka A, Sakaguchi S. Human FOXP3(+) regulatory T cell heterogeneity and function in autoimmunity and cancer. Immunity. 2019;50:302–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ohnmacht C, Park JH, Cording S, et al. MUCOSAL IMMUNOLOGY. The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORgammat(+) T cells. Science. 2015;349:989–993. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Acharya S, Timilshina M, Jiang L, et al. Amelioration of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and DSS induced colitis by NTG-A-009 through the inhibition of Th1 and Th17 cells differentiation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):7799. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-26088-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yu R, Zuo F, Ma H, et al. Exopolysaccharide-producing bifidobacterium adolescentis strains with similar adhesion property induce differential regulation of inflammatory immune response in Treg/Th17 Axis of DSS-colitis mice. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):782. doi: 10.3390/nu11040782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Holmen N, Lundgren A, Lundin S, et al. Functional CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells are enriched in the colonic mucosa of patients with active ulcerative colitis and increase with disease activity. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(6):447–456. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200606000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee YK, Mukasa R, Hatton RD, et al. Developmental plasticity of Th17 and Treg cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(3):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chang JT, Wherry EJ, Goldrath AW. Molecular regulation of effector and memory T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(12):1104–1115. doi: 10.1038/ni.3031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gebhardt T, Wakim LM, Eidsmo L, et al. Memory T cells in nonlymphoid tissue that provide enhanced local immunity during infection with herpes simplex virus. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(5):524–530. doi: 10.1038/ni.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Park CO, Kupper TS. The emerging role of resident memory T cells in protective immunity and inflammatory disease. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):688–697. doi: 10.1038/nm.3883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chang JT. Pathophysiology of inflammatory bowel diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2652–2664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Castro-Dopico T, Colombel JF, Mehandru S. Targeting B cells for inflammatory bowel disease treatment: back to the future. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;55:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2020.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Cerutti A, Rescigno M. The biology of intestinal immunoglobulin A responses. Immunity. 2008;28(6):740–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kaetzel CS. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor: bridging innate and adaptive immune responses at mucosal surfaces. Immunol Rev. 2005;206(1):83–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Batista FD, Harwood NE. The who, how and where of antigen presentation to B cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(1):15–27. doi: 10.1038/nri2454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Uo M, Hisamatsu T, Miyoshi J, et al. Mucosal CXCR4+ IgG plasma cells contribute to the pathogenesis of human ulcerative colitis through FcgammaR-mediated CD14 macrophage activation. Gut. 2013;62:1734–1744. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Martin JC, Chang C, Boschetti G, et al. Single-cell analysis of Crohn’s disease lesions identifies a pathogenic cellular module associated with resistance to Anti-TNF therapy. Cell. 2019;178(6):1493–1508 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Leiper K, Martin K, Ellis A, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of rituximab (anti-CD20) in active ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2011;60(11):1520–1526. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.225482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Boland BS, He Z, Tsai MS, et al. Heterogeneity and clonal relationships of adaptive immune cells in ulcerative colitis revealed by single-cell analyses. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabb4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Zhou L, Sonnenberg GF. Essential immunologic orchestrators of intestinal homeostasis. Sci Immunol. 2018;3:eaao1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Fung TC, Bessman NJ, Hepworth MR, et al. Lymphoid-tissue-resident commensal bacteria promote members of the IL-10 cytokine family to establish mutualism. Immunity. 2016;44(3):634–646. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pham TA, Clare S, Goulding D, et al. Epithelial IL-22RA1-mediated fucosylation promotes intestinal colonization resistance to an opportunistic pathogen. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16(4):504–516. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fukui H, Sekikawa A, Tanaka H, et al. DMBT1 is a novel gene induced by IL-22 in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(5):1177–1188. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lindemans CA, Calafiore M, Mertelsmann AM, et al. Interleukin-22 promotes intestinal-stem-cell-mediated epithelial regeneration. Nature. 2015;528(7583):560–564. doi: 10.1038/nature16460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Van Kemseke C, Belaiche J, Louis E. Frequently relapsing Crohn’s disease is characterized by persistent elevation in interleukin-6 and soluble interleukin-2 receptor serum levels during remission. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15(4):206–210. doi: 10.1007/s003840000226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Atreya R, Neurath MF. New therapeutic strategies for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(3):175–182. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Atreya R, Mudter J, Finotto S, et al. Blockade of interleukin 6 trans signaling suppresses T-cell resistance against apoptosis in chronic intestinal inflammation: evidence in Crohn disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6(5):583–588. doi: 10.1038/75068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Leppkes M, Neurath MF. Cytokines in inflammatory bowel diseases - Update 2020. Pharmacol Res. 2020;158:104835. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104835 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Roda G, Jharap B, Neeraj N, et al. Loss of response to anti-TNFs: definition, epidemiology, and management. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016;7(1):e135. doi: 10.1038/ctg.2015.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(2):133–146. doi: 10.1038/nri1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, et al. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13(5):715–725. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00070-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Teng MW, Bowman EP, McElwee JJ, et al. IL-12 and IL-23 cytokines: from discovery to targeted therapies for immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Nat Med. 2015;21(7):719–729. doi: 10.1038/nm.3895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Schiering C, Krausgruber T, Chomka A, et al. The alarmin IL-33 promotes regulatory T-cell function in the intestine. Nature. 2014;513(7519):564–568. doi: 10.1038/nature13577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Saraiva M, O’Garra A. The regulation of IL-10 production by immune cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(3):170–181. doi: 10.1038/nri2711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wei H, Li B, Sun A, et al. Interleukin-10 family cytokines immunobiology and structure. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1172:79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Glocker E-O, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2033–2045. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Mas-Orea X, Sebert M, Benamar M, et al. Peripheral opioid receptor blockade enhances epithelial damage in piroxicam-accelerated colitis in IL-10-deficient mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:7387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Saha P, Golonka RM, Abokor AA, et al. IL-10 receptor neutralization-induced colitis in mice: a comprehensive guide. Curr Protoc. 2021;1:e227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Xu M, Pokrovskii M, Ding Y, et al. c-MAF-dependent regulatory T cells mediate immunological tolerance to a gut pathobiont. Nature. 2018;554:373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Powrie F, Leach MW, Mauze S, et al. Inhibition of Th1 responses prevents inflammatory bowel disease in scid mice reconstituted with CD45RBhi CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1994;1:553–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Rodrigues VF, Bahia MPS, Candido NR, et al. Acute infection with Strongyloides venezuelensis increases intestine production IL-10, reduces Th1/Th2/Th17 induction in colon and attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in BALB/c mice. Cytokine. 2018;111:72–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Knochelmann HM, Dwyer CJ, Bailey SR, et al. When worlds collide: th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol. 2018;15:458–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Li B, Alli R, Vogel P, et al. IL-10 modulates DSS-induced colitis through a macrophage-ROS-NO axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:869–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ligumsky M, Simon PL, Karmeli F, et al. Role of interleukin 1 in inflammatory bowel disease–enhanced production during active disease. Gut. 1990;31:686–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Liu L, Dong Y, Ye M, et al. The pathogenic role of NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammatory bowel diseases of both mice and humans. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:737–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Siegmund B, Lehr HA, Fantuzzi G, et al. IL-1 beta -converting enzyme (caspase-1) in intestinal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13249–13254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Dinarello CA, Novick D, Kim S, et al. Interleukin-18 and IL-18 binding protein. Front Immunol. 2013;4:289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Lopetuso LR, Chowdhry S, Pizarro TT. Opposing functions of classic and novel IL-1 family members in gut health and disease. Front Immunol. 2013;4:181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Aardoom MA, Veereman G, de Ridder L. A review on the use of anti-TNF in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Armuzzi A, Bouhnik Y, Cummings F, et al. Enhancing treatment success in inflammatory bowel disease: optimising the use of anti-TNF agents and utilising their biosimilars in clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:1259–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Ngo B, Farrell CP, Barr M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor blockade for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: efficacy and safety. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2010;3:145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shih DQ, Michelsen KS, Barrett RJ, et al. Insights into TL1A and IBD pathogenesis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;691:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Siakavellas SI, Bamias G. Tumor necrosis factor-like cytokine TL1A and its receptors DR3 and DcR3: important new factors in mucosal homeostasis and inflammation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2441–2452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]