Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy through 52 weeks of guselkumab, an interleukin 23-p19 subunit inhibitor, in subgroups of pooled psoriatic arthritis (PsA) patients from the DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 trials defined by baseline patient characteristics.

Methods

Adults with active PsA despite standard therapies were enrolled in DISCOVER-1 (≥3 swollen and ≥3 tender joints, C reactive protein (CRP) level ≥0.3 mg/dL) and DISCOVER-2 (≥5 swollen and ≥5 tender joints, CRP ≥0.6 mg/dL, biological-naïve). Randomised patients received 100 mg guselkumab at weeks 0, 4, and then every 4 or 8 weeks (Q4W/Q8W) or placebo. Guselkumab effects on joint (ACR20/50/70), skin (IGA 0/1, IGA 0), patient-reported outcome (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index/Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue) and disease severity (minimal disease activity/PsA Disease Activity Score low disease activity) endpoints were evaluated by patient sex, body mass index, PsA duration, swollen/tender joint counts, CRP level, percent body surface area with psoriasis, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, and conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug use at baseline.

Results

Baseline patients characteristics in DISCOVER-1 (N=381) and DISCOVER-2 (N=739) were well balanced across randomised groups. At week 24, 62% (232/373) and 60% (225/375), respectively, of guselkumab Q4W-treated and Q8W-treated patients pooled across DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 achieved the primary endpoint of ACR20 response versus 29% (109/372) of placebo-treated patients. Guselkumab treatment effect at week 24 was observed across patient subgroups. Within each patient subgroup, response rates across all disease domains were sustained or increased at week 52 with both guselkumab regimens.

Conclusions

Guselkumab Q4W and Q8W resulted in robust and sustained improvements in PsA signs and symptoms consistently in subgroups of patients defined by diverse baseline characteristics.

Trial registration numbers

Keywords: arthritis, psoriatic; biological therapy; therapeutics

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

In the phase III, randomised, placebo-controlled studies, DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2, the selective interleukin 23 inhibitor guselkumab demonstrated efficacy in improving the signs and symptoms of adults with active psoriatic arthritis (PsA) at week 24, and response rates were maintained or increased through week 52.

What does this study add?

Guselkumab demonstrated superior efficacy versus placebo at week 24 across all PsA disease domains evaluated, regardless of baseline patient demographics, disease characteristics or medication use. Guselkumab also provided sustained or further improvements in each of these domains within the varied patient subgroups.

How might this impact on clinical practice or further developments?

These data indicate that a diverse population of patients with PsA can achieve meaningful improvements across disease domains with the use of guselkumab and may see further decreases in disease burden beyond week 24.

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is a chronic, inflammatory disorder associated with peripheral joint inflammation, enthesitis, dactylitis, cutaneous nail involvement and fatigue. The heterogeneous nature of PsA demands individualised and targeted treatment based on specific clinical manifestations, symptom severity and comorbidities.1–3 For patients who have active disease despite conventional therapies, biologicals offer greater control of PsA symptoms1 2; however, a substantial proportion of patients experience loss of response over time or are intolerant to certain biologicals. Drug tolerability, safety, patient satisfaction and efficacy influence treatment persistence,4 with lack of benefit being a common reason for switching biologicals.5 Persistent use of biological therapies, which in considerable numbers of patients is driven by treatment efficacy, is associated with better patient outcomes.

Guselkumab (Janssen Biotech Inc, Horsham, Pennsylvania, USA) is a human monoclonal antibody that selectively inhibits interleukin (IL)-23 by binding the cytokine’s p19 subunit. Guselkumab is the first IL-23 inhibitor approved to treat adults with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (PsO) and active PsA.6 7 Guselkumab 100 mg administered at week 0, week 4 and every 4 or 8 weeks (Q4W or Q8W) significantly improved PsA signs and symptoms with an acceptable safety profile through weeks 24 and 52 in two phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials conducted in patients with active PsA (DISCOVER-18 9 and DISCOVER-210 11). Treatment effect was maintained through up to 2 years in DISCOVER-2.12 Adverse events were generally consistent with those seen in patients with PsO receiving guselkumab 100 mg Q8W for up to 5 years.13 14

Several patient-specific factors influence treatment response and persistence. In a prior analysis of patients with PsA receiving tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi) and enrolled in the DANBIO registry, obesity was associated with higher disease activity and lower levels of treatment response and persistence.15 A similar effect of decreased efficacy in obese patients with PsA was observed in post-hoc analyses from two phase III studies of the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, tofacinitib.16 Patient sex also correlates with treatment persistence,17–19 as does inadequate response to biologicals, with the use of each subsequent biological yielding successively lower rates of drug persistence.17 19–21 However, the difficult-to-treat inadequate responder subpopulation may initially experience greater efficacy responses by switching to an alternative biological following failure of ≥1 TNFi.22 An understanding of treatment response to available biologicals based on patient characteristics is of practical importance. We therefore undertook the current analysis to gain a better understanding of the efficacy of guselkumab across subgroups of patients with PsA with variable demographics and baseline disease characteristics, which may help clinicians optimise treatment to individual patients.

In patients with PsO, guselkumab Q8W has demonstrated consistent efficacy across different baseline subgroups including sex, body mass index (BMI) and previous use of biologicals.23 In the current post-hoc analyses of pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 patients, we assessed the effect of guselkumab versus placebo at week 24 across multiple PsA domains, as well as maintenance of responses through 1 year of guselkumab treatment, in subgroups of patients with PsA defined by their baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and PsA medication use.

Methods

Study design

Details of the randomised, double-blind, phase III DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 trials have been reported.8 10 Briefly, adults with active PsA who had inadequate responses to standard therapies were randomised 1:1:1 to receive subcutaneous injections of guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4 and then Q4W; guselkumab 100 mg at weeks 0, 4, and then Q8W; or placebo Q4W with crossover to guselkumab Q4W at week 24. Stable doses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), oral corticosteroids and selected conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) were permitted. At week 16, patients with <5% improvement in both tender and swollen joint counts (TJC/SJC) were permitted early escape and had the option to initiate or increase allowed concomitant PsA medications. Treatment continued through week 48 (DISCOVER-1) and week 100 (DISCOVER-2).

Patients

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 have been previously detailed.8 10 Enrolled patients were adults with active PsA despite previous therapy with csDMARDs, apremilast and/or NSAIDs. Patients were diagnosed with PsA for ≥6 months and met Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis. In DISCOVER-1, patients were required to have ≥3 swollen joints, ≥3 tender joints and C reactive protein (CRP) ≥0.3 mg/dL; approximately 30% of enrolled patients had received prior TNFi therapy. In DISCOVER-2, patients were required to have ≥5 swollen joints, ≥5 tender joints and CRP ≥0.6 mg/dL; all patients in DISCOVER-2 were biological-naive. Exclusion criteria included other inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, specified infections including active tuberculosis (TB), most malignancies within 5 years of screening, any prior use of JAK inhibitors, and prior phototherapy or systemic immunosuppressants within 4 weeks of study agent administration.

Efficacy assessments and outcomes

Details of efficacy assessments and outcome measures in the DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies have been previously reported.8 10 For the purpose of these post-hoc analyses, efficacy endpoints evaluated at weeks 24 and 52 included the proportions of patients achieving: (1) ≥20/50/70% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria (ACR20/50/70)24 25; (2) an Investigator’s Global Assessment of skin disease (IGA) score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) and ≥2-grade reduction from baseline, or an IGA 0 response, each among patients with baseline body surface area (BSA) ≥3% with PsO and IGA ≥226 27; (3) ≥4-point improvement from baseline in the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT-F)28 score; (4) ≥0.35-point improvement from baseline in the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)29 score among patients with a baseline HAQ-DI score ≥0.35; (5) a PsA Disease Activity Score (PASDAS)30 ≤3.2, indicative of low disease activity (LDA); and (6) minimal disease activity (MDA).31

Statistical methods

Post-hoc efficacy analyses reported herein were performed using the full analysis set from the pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies, which included all randomised patients who received ≥1 dose of study agent. Efficacy outcomes were stratified by the following demographic and disease characteristics: sex (male, female), BMI (<25, 25 to <30 or ≥30 kg/m2), SJC (<10, 10–15 or >15), TJC (<10, 10–15 or >15), BSA affected by PsO (<3, ≥3 to <10, ≥10 to <20 or ≥20%), time since PsA diagnosis (PsA duration) (<1, ≥1 to <3 or ≥3 years), CRP level (<1, 1 to <2 or ≥2 mg/dL), Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score (<12, ≥12 to <20 or ≥20) and csDMARD/methotrexate (MTX) use (none, any csDMARD or MTX) at baseline.

Patients meeting treatment failure criteria, that is, patients who discontinued study treatment, terminated study participation, initiated or increased doses of csDMARDs or oral corticosteroids, or initiated protocol-prohibited PsA treatment, prior to week 24, were considered non-responders, and missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response.8–11

ORs and 95% CIs for comparing each guselkumab treatment group versus placebo for each baseline patient subgroups at week 24 were based on a logistic regression with treatment group as the explanatory factor. Response rates at weeks 24 and 52 were also determined across baseline patient subgroups. Response rates at weeks 24 and 52 were compared to assess specific increases in response rates post-week 24, that is, <5%, 5% to <10%, 10% to <15%, 15% to <20% and 20% to <25%, within each patient subgroup.

Results

Patients

A total of 1120 patients were randomised and treated in the DISCOVER-18 and DISCOVER-210 studies. Patients pooled from both studies completing study agent through 1 year included 94% (350/373), 93% (350/375) and 90% (335/372) of guselkumab Q4W, guselkumab Q8W, and crossover patients, respectively.

Baseline patient demographics, disease characteristics and csDMARD use were generally well balanced across randomised groups within each trial8 10 and for the pooled PsA population (table 1). Patients in these studies had established and active disease, with substantial joint involvement, systemic inflammation and fatigue at baseline (table 1). Among 1120 pooled patients, the mean SJC was 11, mean TJC was 21 and mean FACIT-F score was 30 (score ranges from 0 to 52, with lower scores indicating worse fatigue); 68% reported csDMARD use at baseline.

Table 1.

Pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 baseline demographics, disease characteristics and concomitant PsA treatment

| GUS Q4W | GUS Q8W | PBO | All patients | |

| Randomised and treated patients (N) | 373 | 375 | 372 | 1120 |

| Male (%) | 56 | 52 | 48 | 52 |

| Age (years) | 46 | 46 | 47 | 47 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 | 29 | 29 | 29 |

| PsA duration (years) | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| SJC (0–66) | 11.4 | 11.4 | 11.5 | 11.4 |

| TJC (0–68) | 20.8 | 19.9 | 21.0 | 20.6 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | ||||

| Mean | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.8 |

| Median | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| csDMARD use at baseline (%) | 68 | 68 | 68 | 68 |

| MTX use at baseline (%) | 58 | 56 | 61 | 58 |

| % BSA with psoriasis (0%–100%) | 17 | 16* | 15† | 16‡ |

| PASI score (0–72) | 10 | 9 | 9† | 10¶ |

| FACIT-F (0–52)§ | 31 | 29 | 30† | 30¶ |

Data are mean values unless stated otherwise.

*N=372.

†N=371.

‡N=1116.

§Higher scores indicate less fatigue.

¶N=1119.

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; GUS, guselkumab; MTX, methotrexate; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PBO, placebo; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks; SJC, swollen joint count; TJC, tender joint count.

Treatment effect at week 24

ACR20/50/70

Patients receiving guselkumab Q4W (62%, 232/373) or Q8W (60%, 225/375) in DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 were more likely to achieve an ACR20 response at week 24 than placebo-treated patients (29%, 109/372) (figure 1). The corresponding ORs (95% CIs) comparing guselkumab Q4W and Q8W versus placebo were 4.0 (2.9 to 5.4) and 3.6 (2.7 to 4.9), respectively (online supplemental table 1).

Figure 1.

Proportions of patients achieving ACR20 response at week 24 and week 52 by patient demographics, disease characteristics and csDMARD use at baseline. Week 24 response rates (NRI) are compared between guselkumab (GUS) and placebo (PBO) via ORs and 95% CIs (depicted via forest plot; actual values provided in online supplemental table 1). Week 52 response rates (NRI) for GUS Q4W and Q8W were determined to assess durability of ACR20 response rates within each patient subgroup. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response. ACR20, American College of Rheumatology 20% improvement; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

rmdopen-2022-002195supp001.pdf (92.3KB, pdf)

The benefit of guselkumab Q4W/Q8W, respectively, over placebo in achieving an ACR20 response at week 24 was seen regardless of patient sex (ORs: 4.2/3.5 for males; 3.5/3.7 for females), baseline BMI (ORs: 4.2/2.4 for <25 kg/m2; 4.4/4.1 for 25 to <30 kg/m2; 3.7/4.3 for ≥30 kg/m2), or years since PsA diagnosis (ORs: 3.6/6.8 for <1; 6.2/4.0 for ≥1 to <3; 3.5/2.9 for ≥3 years). Guselkumab Q4W/Q8W, respectively, also remained superior to placebo in achieving an ACR20 response regardless of baseline disease activity as measured by SJC (ORs: 5.1/3.3 for <10; 3.1/4.1 for 10 to 15; 3.2/4.1 for >15 joints), TJC (ORs: 7.9/4.5 for <10; 4.7/3.5 for 10 to 15; 3.0/3.5 for >15 joints) or serum CRP (ORs: 4.0/3.7 for <1; 8.3/7.7 for 1 to <2; 2.5/2.4 for ≥2 mg/dL). The benefit of guselkumab Q4W/Q8W, respectively, over placebo was also evident regardless of baseline csDMARD/MTX use (ORs: 6.6/5.6 with no use; 3.2/3.0 with use of any csDMARDs; 3.6/2.8 for MTX use) (online supplemental table 1).

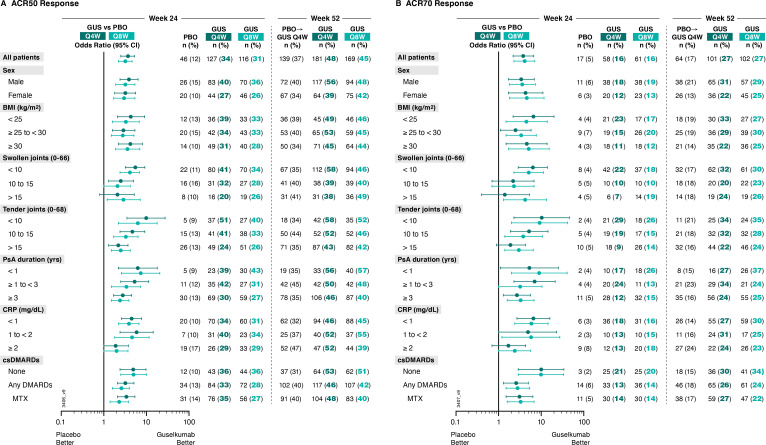

Importantly, generally consistent results were seen for achievement of ACR50 and ACR70 responses at Week 24 (figure 2, (online supplemental table 1). Guselkumab Q4W/Q8W ORs (95% CIs) versus placebo were 3.7 (2.5 to 5.3) and 3.2 (2.2 to 4.6), respectively, for ACR50 response, and 3.8 (2.2 to 6.7) and 4.1 (2.3 to 7.1), respectively, for ACR70 response. ORs pertaining to ACR50 and ACR70 responses ranged from 1.9 to 9.9 and 1.4 to 10.3 across subgroups with adequate sample size (online supplemental table 1).

Figure 2.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) ACR50 and (B) ACR70 responses at week 24 and week 52 by patient demographics, disease characteristics and csDMARD use at baseline. Week 24 response rates (NRI) are compared between guselkumab (GUS) and placebo (PBO) via ORs and 95% CIs (depicted via forest plot; actual values provided in online supplemental table 1). Week 52 response rates (NRI) for GUS Q4W and GUS Q8W were determined to assess durability of ACR50 and ACR70 response rates within each patient subgroup. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through Weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response. ACR50/70, American College of Rheumatology 50/70% improvement; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; MTX, methotrexate; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

IGA 0/1 and IGA 0. Among patients with ≥3% BSA with PsO and IGA ≥2 at baseline, IGA 0/1 response rates at week 24 were substantially higher with guselkumab Q4W (71%, 193/273) and Q8W (66%, 171/258) than with placebo (18%, 47/261) (figure 3). Corresponding ORs (95% CIs) comparing guselkumab Q4W and Q8W versus placebo were 11.0 (7.3 to 16.5) and 8.9 (6.0 to 13.5), respectively (online supplemental table 2).

Figure 3.

Proportions of patients with ≥3% BSA with PsO and IGA ≥2 at baseline achieving an (A) IGA 0/1 response (IGA psoriasis score of 0 (cleared) or 1 (minimal) and ≥2-grade reduction from baseline) and (B) IGA 0 response (IGA psoriasis score of 0) at week 24 and week 52 by patient demographics, disease characteristics, and csDMARD use at baseline. Week 24 response rates (NRI) are compared between guselkumab (GUS) and placebo (PBO) via ORs and 95% CIs (depicted via forest plot; actual values provided in online supplemental table 2). Week 52 response rates (NRI) for GUS Q4W and GUS Q8W were determined to assess durability of IGA 0/1 and IGA 0 response rates within each patient subgroup. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response. *Plot is undrawable due to NC values. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; MTX, methotrexate; NC, no count; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

rmdopen-2022-002195supp002.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)

Higher rates of achieving clear or almost clear skin with guselkumab Q4W or Q8W versus placebo were also seen when stratifying patients by baseline demographics (sex ORs: 7.4–14.6; BMI ORs: 8.6–11.5), disease characteristics (duration of PsA ORs: 8.0–12.1; baseline serum CRP ORs: 7.6–12.9) or csDMARD use at baseline (ORs: 8.1–21.1). Importantly, guselkumab Q4W/Q8W, respectively, also demonstrated greater achievement of IGA 0/1 response over placebo regardless of baseline skin disease, as measured by percent BSA with PsO involvement (ORs: 6.8/7.2 for ≥3% to <10%; 8.1/5.9 for ≥10% to <20%; 24.6/15.9 for ≥20%) and PASI score (ORs: 7.8/7.2 for <12; 20.0/13.9 for ≥12 to 20; 22.3/14.8 for ≥20) at baseline (online supplemental table 2).

Results were consistent when assessing achievement of clear skin (IGA 0 response) at week 24 (figure 3, online supplemental table 2). Guselkumab Q4W/Q8W ORs (95% CIs) versus placebo were 12.9 (7.7 to 21.5) and 10.3 (6.1 to 17.3), respectively, for IGA 0 response. ORs pertaining to IGA 0 response ranged from 6.6 to 24.1 across subgroups with adequate sample size (online supplemental table 2).

Patient-reported fatigue

Among patients treated with guselkumab Q4W or Q8W, a higher proportion achieved a FACIT-F response at week 24 (61% (227/373) and 58% (218/375), respectively) than those being treated with placebo (42% (156/371)) (figure 4). The ORs (95% CIs) comparing the guselkumab Q4W and Q8W versus placebo treatment groups were 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) and 1.9 (1.4 to 2.6), respectively (online supplemental table 3).

Figure 4.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) FACIT-Fatigue response (≥4-point improvement in FACIT-F score from baseline) and (B) HAQ-DI response (≥0.35-point improvement in HAQ-DI score from baseline among patients with a HAQ-DI score ≥0.35 at baseline) at week 24 and week 52 by patient demographics, disease characteristics and csDMARD use at baseline. Week 24 response rates (NRI) are compared between guselkumab (GUS) and placebo (PBO) via ORs and 95% CIs (depicted via forest plot; actual values provided in online supplemental table 3). Week 52 response rates (NRI) for GUS Q4W and GUS Q8W were determined to assess durability of FACIT-F and HAQ-DI response rates within each patient subgroup. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response. BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; FACIT-F, Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

rmdopen-2022-002195supp003.pdf (90.5KB, pdf)

As was demonstrated for joint and skin efficacy outcomes, the benefit of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W over placebo in achieving a FACIT-F response at week 24 was achieved regardless of patient demographics (sex ORs: 1.7–2.4; BMI ORs: 1.7–2.4) or disease characteristics (PsA duration ORs: 1.5–2.8; SJC ORs: 1.4–2.6; TJC ORs: 1.4–2.3; serum CRP ORs: 1.9–3.0). Guselkumab benefit over placebo in achieving a FACIT-F response was also not influenced by PsA treatment including baseline csDMARD/MTX use (OR: 1.5–3.4) (online supplemental table 3).

Patient-reported physical function

Among patients with a baseline HAQ-DI score ≥0.35, 56% (191/338) and 50% (171/340) of guselkumab Q4W-treated and Q8W-treated patients, respectively, versus 31% (106/346) of placebo-treated patients achieved a HAQ-DI response at week 24 (figure 4). Corresponding ORs (95% CIs) comparing guselkumab Q4W and Q8W versus placebo were 2.9 (2.1 to 4.0) and 2.3 (1.7 to 3.1), respectively (online supplemental table 3).

Guselkumab Q4W and Q8W demonstrated a benefit over placebo in achieving HAQ-DI response regardless of patient demographics (sex ORs: 1.9–3.3; BMI ORs:1.9–3.2). Guselkumab-treated patients achieved a HAQ-DI response more often than placebo-treated patients in all patient disease characteristic subgroups (PsA disease duration ORs: 1.5–6.1; SJC ORs: 2.0–3.4; TJC ORs: 2.0–3.9; serum CRP ORs: 1.9–4.2). Guselkumab also demonstrated benefit over placebo in achieving a HAQ-DI response regardless of baseline csDMARD/MTX use (OR: 1.4–7.3) (online supplemental table 3).

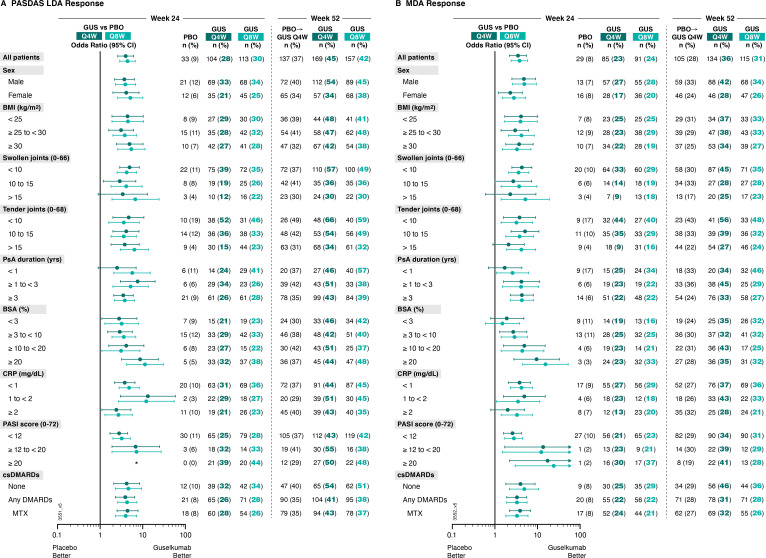

Composite measures of disease activity

Consistent with joint, skin and patient-reported efficacy outcomes, patients receiving guselkumab Q4W or Q8W were more likely than patients receiving placebo to achieve PASDAS LDA at week 24. Among patients receiving guselkumab Q4W and Q8W, 28% (104/373) and 30% (113/375), respectively, achieved PASDAS LDA at week 24, compared with 9% (33/372) of patients receiving placebo (figure 5). Respective ORs (95% CIs) of 4.0 (2.6 to 6.1) and 4.4 (2.9 to 6.7) comparing guselkumab Q4W or Q8W with placebo also suggest guselkumab-treated patients were more likely to achieve PASDAS LDA (online supplemental table 4).

Figure 5.

Proportions of patients achieving (A) PASDAS Low Disease Activity (PASDAS score ≤3.2) and (B) MDA responses at week 24 and week 52 by patient demographics, disease characteristics and DMARD use at baseline. Week 24 response rates (NRI) are compared between guselkumab (GUS) and placebo (PBO) via ORs and 95% CIs (depicted via forest plot; actual values provided in online supplemental table 4). Week 52 response rates (NRI) for GUS Q4W and GUS Q8W were determined to assess durability of PASDAS LDA and MDA response rates within each patient subgroup. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response. *Plot is not drawable due to NC values. BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; LDA, low disease activity; MDA, minimal disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; NC, no count; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; PASDAS, Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

rmdopen-2022-002195supp004.pdf (94.5KB, pdf)

Stratification by baseline patient subgroups, including skin disease characteristics, revealed no notable difference in guselkumab Q4W or Q8W benefit over placebo in achieving PASDAS LDA. Among subgroups with sufficient sample size, this benefit was seen regardless of patient demographics (sex ORs: 3.7–5.1; BMI ORs: 3.1–5.4) or PsA disease characteristics (PsA disease duration ORs: 2.5–7.6; SJC ORs: 2.9–6.7; TJC ORs: 3.6–6.4; serum CRP ORs: 2.4–13.2). The achievement of PASDAS LDA was also not affected by baseline csDMARD/MTX use (ORs: 3.9–4.6). PASDAS LDA was also achieved by a greater proportion of guselkumab-treated patients at week 24 irrespective of patient percent BSA with PsO involvement (ORs: 2.9 and 3.6 for ≥3% to<10%, 4.1 and 3.1 for ≥10% to <20%, and 8.7 and 11.3 for ≥20%) and PASI score (ORs:2.8–7.2; note that no placebo patients with baseline PASI score ≥20 achieved PASDAS LDA at week 24 (figure 5)) at baseline (online supplemental table 4).

MDA was also achieved by a greater proportion of patients receiving guselkumab Q4W or guselkumab Q8W compared with patients receiving placebo at week 24. 23% and 24% of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W patients, respectively, compared with 8% of placebo patients, achieved MDA at Week 24, with corresponding ORs (95% CI) of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W versus placebo of 3.5 (2.2 to 5.5) and 3.8 (2.4 to 5.9) (figure 5, (online supplemental table 4).

Among patient subgroups with adequate sample size, benefit of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W, respectively, over placebo in reducing disease activity, assessed by MDA response, at week 24 was seen regardless of patient demographics (sex ORs: 2.3–4.9; BMI ORs: 3.0–4.2) or disease characteristics (PsA disease duration ORs: 1.7–4.3; SJC ORs: 2.3–5.2; TJC ORs: 2.1–5.1; serum CRP ORs: 2.0–4.9), or skin disease (BSA with PsO involvement ORs: 1.5–15.4; PASI score ORs: 2.6–24.0). We also report no effect of baseline csDMARD/MTX use on guselkumab treatment benefit in achieving MDA (ORs: 3.3–4.9) (online supplemental table 4).

Effects of crossing over from placebo to guselkumab Q4W

Within each patient subgroup, patients who underwent crossover from placebo to guselkumab Q4W achieved similar response rates at week 52 as guselkumab-randomised patients across all efficacy domains (figures 1–5). Although HAQ-DI response patterns in crossover patients were similar to those in guselkumab-randomised patients, fewer of the crossover patients reported clinically meaningful improvements in physical function across all subgroups (figure 4).

Maintenance of response through week 52

Within each patient subgroup, response rates at week 24 were maintained or increased at week 52 at the population level (figures 1–5). Patient subgroups with specific increases in response rates post-week 24, that is, <5%, 5%–<10%, 10%–<15%, 15%–<20% and 20%–<25%, are highlighted in table 2.

Table 2.

Joint, skin and disease state response rates (%) at week 52 for GUS-randomised patients by baseline subgroups among pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 patients

| ACR20 response* | ACR50 response* | ACR70 response* | IGA 0/1 response† | IGA 0 response‡ | MDA response§ | |||||||

| Q4W | Q8W | Q4W | Q8W | Q4W | Q8W | Q4W | Q8W | Q4W | Q8W | Q4W | Q8W | |

| All patients | 71.6 | 69.6 | 48.5 | 45.1 | 27.1 | 27.2 | 80.2 | 70.9 | 63.7 | 55.0 | 35.9 | 30.7 |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 77.9 | 73.6 | 56.3 | 47.7 | 31.3 | 28.9 | 81.9 | 71.3 | 62.6 | 50.0 | 42.3 | 34.5 |

| Female | 63.6 | 65.2 | 38.8 | 42.1 | 21.8 | 25.3 | 78.0 | 70.4 | 65.3 | 62.0 | 27.9 | 26.4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||||||

| <25 | 75.0 | 69.3 | 48.9 | 45.5 | 32.6 | 26.7 | 81.5 | 70.6 | 61.5 | 55.9 | 37.0 | 32.7 |

| 25–<30 | 74.8 | 71.5 | 52.8 | 45.4 | 29.3 | 30.0 | 81.6 | 75.0 | 73.6 | 54.5 | 38.2 | 33.1 |

| ≥30 | 67.1 | 68.1 | 44.9 | 44.4 | 22.2 | 25.0 | 78.5 | 67.6 | 57.9 | 54.9 | 33.5 | 27.1 |

| Swollen joint count | ||||||||||||

| <10 | 78.9 | 68.1 | 57.7 | 46.1 | 32.0 | 29.9 | 44.8 | 34.8 | ||||

| 10–15 | 61.2 | 68.0 | 38.8 | 40.2 | 20.4 | 22.7 | 27.6 | 27.8 | ||||

| >15 | 66.7 | 75.7 | 38.3 | 48.6 | 23.5 | 25.7 | 24.7 | 23.0 | ||||

| Tender joint count | ||||||||||||

| <10 | 72.6 | 75.0 | 57.5 | 51.5 | 34.2 | 35.3 | 56.2 | 48.5 | ||||

| 10–15 | 75.8 | 68.4 | 52.5 | 45.6 | 32.3 | 28.1 | 39.4 | 31.6 | ||||

| >15 | 69.2 | 68.4 | 43.3 | 42.5 | 21.9 | 23.8 | 26.9 | 23.8 | ||||

| BSA affected by psoriasis (%) |

||||||||||||

| <3 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 34.7 | 31.7 | ||||||

| ≥3–<10 | 75.8 | 67.3 | 62.1 | 60.4 | 32.5 | 32.5 | ||||||

| ≥10–<20 | 87.3 | 72.1 | 70.9 | 50.8 | 42.9 | 25.4 | ||||||

| ≥20 | 78.8 | 74.0 | 59.6 | 52.1 | 35.0 | 32.0 | ||||||

| PsA duration (years) | ||||||||||||

| <1 | 76.3 | 81.4 | 55.9 | 57.1 | 27.1 | 37.1 | 84.6 | 75.6 | 66.7 | 62.2 | 33.9 | 45.7 |

| ≥1–<3 | 75.0 | 73.6 | 50.0 | 48.3 | 34.5 | 24.1 | 85.7 | 73.0 | 69.8 | 52.4 | 45.2 | 28.7 |

| ≥3 | 69.1 | 64.2 | 46.1 | 39.9 | 24.3 | 25.2 | 77.2 | 68.7 | 60.8 | 54.0 | 33.0 | 26.6 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| <1 | 70.7 | 68.6 | 45.9 | 45.4 | 26.8 | 30.4 | 82.3 | 71.8 | 68.8 | 56.5 | 37.1 | 35.6 |

| 1–<2 | 71.4 | 79.1 | 51.9 | 55.2 | 31.2 | 25.4 | 78.3 | 74.5 | 55.0 | 59.6 | 42.9 | 32.8 |

| ≥2 | 73.6 | 65.8 | 51.6 | 38.6 | 24.2 | 22.8 | 77.8 | 67.5 | 61.1 | 50.0 | 27.5 | 21.1 |

| PASI score at baseline (0–72) | ||||||||||||

| <12 | 78.2 | 71.2 | 64.8 | 60.0 | 34.2 | 31.4 | ||||||

| ≥12–<20 | 85.5 | 66.7 | 63.6 | 52.4 | 39.3 | 28.6 | ||||||

| ≥20 | 81.1 | 73.9 | 60.4 | 39.1 | 40.7 | 28.3 | ||||||

| csDMARD/MTX use | ||||||||||||

| None | 80.2 | 73.0 | 52.9 | 50.8 | 29.8 | 33.6 | 86.5 | 76.6 | 66.3 | 60.6 | 46.3 | 36.1 |

| Any csDMARD | 67.5 | 68.0 | 46.4 | 42.3 | 25.8 | 24.1 | 77.2 | 67.7 | 62.5 | 51.8 | 31.0 | 28.1 |

| MTX | 68.3 | 68.4 | 47.7 | 39.7 | 27.1 | 22.5 | 77.6 | 68.1 | 62.7 | 50.0 | 31.7 | 26.3 |

| Change from week 24–52 (percentage points) | ||||||||||||

| −10 to <−5 | −5 to <0 | 0 to <5 | 5 to <10 | 10 to <15 | 15 to <20 | 20– to <25 | ||||||

Heat map shading highlights degree of increase in response rate from week 24 to week 52. Prior to week 24, patients meeting treatment failure criteria were considered non-responders. Missing data through weeks 24 and 52 were imputed as non-response.

*≥20%, ≥50% and ≥70%, respectively, improvement from baseline in both tender joint count (68 joints) and swollen joint count (66 joints), and ≥20%, ≥50% and ≥70%, respectively, improvement from baseline in at least 3 of the 5 assessments: patient’s assessment of pain, patient’s global assessment of disease activity, physician’s global assessment of disease activity, HAQ-DI and CRP.

†IGA psoriasis score of 0 (cleared) or 1 (minimal) and ≥2-grade reduction from baseline in the IGA psoriasis score among patients with ≥3% BSA with psoriasis and IGA ≥2 at baseline.

‡IGA psoriasis score of 0 (cleared) among patients with ≥3% BSA with psoriasis and IGA ≥2 at baseline.

§5/7 MDA criteria are met (tender joint count ≤1, swollen joint count ≤1, psoriasis activity and severity index ≤1, patient’s assessment of pain ≤15, patient’s global assessment of disease activity ≤20, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index score ≤0.5, tender entheseal points ≤1).

ACR20/50/70, American College of Rheumatology 20/50/70% improvement; BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; CRP, C reactive protein; csDMARD, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GUS, guselkumab; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; IGA, Investigator’s Global Assessment; MDA, minimal disease activity; MTX, methotrexate; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Q4W/Q8W, every 4 weeks/every 8 weeks.

Higher ACR20 response rates at week 52 than week 24 across patient subgroups, together with robust increases in ACR50 and ACR70 response rates from week 24 to 52, suggest patients with varying baseline characteristics may experience continued improvement of joint signs and symptoms post-week 24. There was no evidence of a guselkumab dosing regimen response on improvements in joint signs and symptoms through week 52.

While guselkumab Q4W or Q8W elicited robust IGA 0/1 and IGA 0 response rates at week 24, accrual of patients achieving these endpoints continued through week 52 across patient subgroups. With guselkumab Q4W, most patient subgroups saw a ≥10 percentage point increase in IGA 0/1 and IGA 0 response rates from week 24 to 52.

The increase in proportions of guselkumab-treated patients achieving MDA from week 24 to 52 across patient subgroups also suggests that patients with PsA with a range of differing characteristics may continue to progress to minimal levels of disease activity with continued guselkumab. MDA response rates generally increased by 5%–15% among patients receiving guselkumab Q8W and 10%–25% in patients receiving guselkumab Q4W from week 24 to 52.

Discussion

Due to the heterogenous nature of PsA and accompanying comorbidities, many patients experience lower response and poorer maintenance of response to current treatments than others. Several factors including, but not limited to, patient sex, BMI at baseline and prior biological exposure affect PsA treatment outcomes with TNF, IL-17 and IL-12/23 inhibitors.15 17 19 Clinical practice guidelines do not consistently consider differing baseline patient characteristics when recommending PsA treatments. The current analyses were therefore undertaken to investigate treatment effect and maintenance of response of guselkumab in diverse PsA patient subgroups.

Results of these post-hoc analyses from the pooled DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 studies showed that guselkumab 100 mg Q4W and Q8W demonstrated greater efficacy than placebo at week 24 in multiple PsA disease domains across all baseline subgroups evaluated. In addition, both guselkumab dosing regimens demonstrated durable or higher efficacy responses at week 52 than week 24 across disease domains, including joint and skin manifestations, fatigue and physical function, and when overall disease activity was assessed using validated and accepted composite measures.

Well-known factors that can affect response to PsA treatment include female sex and pre-existing obesity. These observations may relate to females, who have longer PsA disease duration, higher BMI, higher disease severity scores and increased central sensitisation compared with males,32–34 reporting more severe fatigue and poorer physical function than males.32 35–37 Consistent with these predisposing factors, a numerically smaller proportion of females than males achieved an MDA response at weeks 24 and 52, though a similar trend in greater achievement of MDA response at weeks 24 and 52 with guselkumab versus placebo was seen for both the Q4W and Q8W guselkumab dosing regimens in both males and females. Although we did not assess effect of guselkumab on each of the components comprising the MDA efficacy measure within each patient cohort, women have shown a significantly lower prevalence of MDA than men after 1 year of PsA treatment.38 Further investigation is needed to assess guselkumab efficacy by sex for individual PsA disease domains.

Obese patients report worse physical function and pain than non-obese patients.39 These disease domains can be especially recalcitrant to treatment.40 Obese immune-mediated inflammatory disease patients, including patients with PsA, have 60% higher odds of failing TNFi therapy compared with non-obese patients.41 Furthermore, a prospective study assessing the impact of obesity on TNFi treatment efficacy suggests lesser achievement of MDA at 1 year and through 2 years in patients with a BMI >30 versus ≤30 kg/m2, and a lesser likelihood of maintaining MDA achieved at 1 year through 2 years in patients with a BMI >30 kg/m2.42 The IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab demonstrated an inverse association of LDA and BMI in PsA after 6 months of treatment, perhaps due to greater serum IL-17 levels in patients with BMI ≥25 versus <25 kg/m2.43 However, in PsO, a real-world study of secukinumab and the IL-17 inhibitor ixekizumab showed lower rates of skin response at 12 and 24 weeks and at 24 weeks, respectively, among patients with BMI ≥30 versus <30 kg/m2.44 In the current post-hoc study, guselkumab Q4W and Q8W effect at week 24 was maintained through week 52 regardless of sex and obese versus non-obese status, supporting the potential benefits of guselkumab in treating these patient subgroups.

PsA treatment efficacy and persistence may be greater with shorter disease duration,18 45 perhaps because PsA disease burden, including decreased physical function, improves to a greater extent during early disease.46 Here, guselkumab treatment effect was retained regardless of PsA disease duration <1 year, ≥1–<3 years or ≥3 years. Additionally, clinical response rates across all disease domains increased at week 52 from week 24 regardless of PsA disease duration.

Patients with PsA with active skin involvement typically experience worse patient outcomes than those without.47 We observed robust skin response across baseline subgroups, consistent with previous findings in PsO patients treated with guselkumab. High rates of skin clearance23 48 and maintenance of response48 by IL-23p19-subunit inhibitors have been observed regardless of patient sex, BMI, percent BSA affected by PsO, PASI score, or presence of PsA at baseline.

Concomitant MTX increases the persistence of some PsA treatments (ie, TNFi).49 Guselkumab efficacy was comparable and sustained through 52 weeks across clinical outcome measures regardless of baseline csDMARD use, including MTX (used by 58% of the pooled population), for both dosing regimens over placebo. Although we did not report on guselkumab efficacy by prior biological use in these post-hoc analyses, consistent guselkumab effect on achieving the primary endpoint of ACR20 response at week 24 through 52 weeks was demonstrated for both TNFi-experienced and TNFi-naïve patient cohorts in the DISCOVER-1 study.8 9

In light of these results, it is noteworthy that no additional safety signals were reported with guselkumab from weeks 24 to 52,9 11 and the guselkumab safety profile through 2 years in PsA was consistent with that seen in PsO through 5 years.9 11 12 50

There are some potential limitations to these post-hoc analyses. Guselkumab and placebo comparisons extended through only 24 weeks. Although these analyses stratified patients by a broad selection of baseline factors, there may be other patient subgroups identified in the future worthy of exploration. These analyses were also limited by small numbers of patients in several patient subgroups. Stratification of patients by baseline subgroups led to decreased sample sizes; thus, conclusions drawn from these analyses require further confirmation. In particular, a relatively small subset of patients had prior biological use, as only DISCOVER-1 allowed enrolment of TNFi-experienced patients, ultimately comprising ~10% of the pooled patient population.8 Reassuringly, the phase IIIb, randomised, placebo-controlled study of guselkumab in adults with active PsA who discontinued one or two TNFi due to lack of efficacy or intolerance, COSMOS, showed that guselkumab-treated patients had significantly greater improvement in signs and symptoms of PsA than placebo-treated patients, regardless of baseline patient, disease and prior/concomitant medication characteristics evaluated, at week 24, and that improvements were maintained or improved through week 52.51 Finally, the DISCOVER-1 and DISCOVER-2 clinical trial cohorts represent only a portion of patients with PsA seen in clinical practices and are not necessarily representative of a broader population of patients with PsA.

The benefits of guselkumab Q4W and Q8W in providing robust and durable improvements in the signs and symptoms of active PsA appear to be consistent irrespective of the baseline patient sex, BMI, SJC, TJC, percent BSA affected by PsO, PASI score, PsA disease duration, serum CRP level or prior csDMARD use, including MTX. Considering the high rates of DISCOVER-2 patient retention through 2 years (nearly 90% of patients continued treatment through 2 years); durable guselkumab efficacy assessed by ACR20/50/70, HAQ-DI, IGA and MDA responses at 1 and 2 years; and favourable guselkumab safety profile through 2 years in PsA, guselkumab Q4W and Q8W appears to offer a favourable benefit–risk profile for a broad population of patients with PsA. This is clinically relevant for this heterogenous and often recalcitrant disorder that regularly requires chronic therapy.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Alexandra Guffey, MSc of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC under the direction of the authors in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2015;163:461–4).

Footnotes

Contributors: Substantial intellectual contributions to study conception and design (CTR, PJM, W-HB, JT, ES, SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, JFM, IBM, AD), acquisition of data (SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, SS, YW, SX) or analysis and/or interpretation of data (CTR, PJM, W-HB, JT, ES, SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, SS, YW, SX, JFM, IBM, AD); drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content (CTR, PJM, W-HB, JT, ES, SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, SS, YW, SX, JFM, IBM, AD); final approval of the version to be published (CTR, PJM, W-HB, JT, ES, SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, SS, YW, SX, JFM, IBM, AD), and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved (CTR, PJM, W-HB, JT, ES, SDC, APK, XLX, MS, YJ, SS, YW, SX, JFM, IBM, AD). CTR s responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: Janssen Research & Development, LLC funded this study.

Competing interests: CTR has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Lilly, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; and speaker fees from Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma. PJM has received research grants, consulting fees and/or speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Galapagos, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, SUN Pharma and UCB Pharma. W-HB has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Novartis and UCB Pharma; speaker fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, Leo and UCB Pharma; fees for expert testimony from Novartis; and fees for participation on an advisory board from AbbVie, Almirall, Janssen, Leo, Novartis and UCB Pharma. JT has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, CoreVitas, Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Pfizer and Sun Pharma; consulting fees from AbbVie, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer; speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Janssen and Pfizer; and advisory board fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. ES has received research grants and consulting fees from Janssen. SDC is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC is a wholly owned subsidiary. APK, XLX, SS and SX are employees of Janssen Research & Development, LLC and own stock in Johnson & Johnson, of which Janssen Research & Development is a wholly owned subsidiary. MS is an employee of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson and owns stock in Johnson & Johnson. YJ is a consultant employed by Cytel, Inc and funded by Janssen to provide statistical support. YW is a consultant employed by IQVIA, Inc and funded by Janssen to provide statistical support. JFM has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Arena, Biogen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Dermavant, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sun Pharma and UCB Pharma. IBM has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Causeway Therapeutics, Gilead, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron and Sanofi; has served as a board member for NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde; has served as Vice Principal & Head of MVLS College at University of Glasgow; and has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Causeway Therapeutics, Lilly, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. AD has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Lilly, MoonLake, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; speaker fees from Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer and UCB Pharma; and advisory board fees from AbbVie, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, MoonLake, Novartis and UCB Pharma.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at http://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and both trials were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practices. Protocols were approved by ethics committees at each site (Sterling IRB approval numbers (US sites): 5959C and 5910C). Participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Gossec L, Baraliakos X, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2019 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79:700–12. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68:1060–71. 10.1002/art.39573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coates LC, Soriano E, Corp N, et al. The Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis (GRAPPA) treatment recommendations 2021. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:139–40. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-eular.4091 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yeung H, Wan J, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Patient-reported reasons for the discontinuation of commonly used treatments for moderate to severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2013;68:64–72. 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorenzin M, Ortolan A, Cozzi G, et al. Predictive factors for switching in patients with psoriatic arthritis undergoing anti-TNFα, anti-IL12/23, or anti-IL17 drugs: a 15-year monocentric real-life study. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:4569–80. 10.1007/s10067-021-05799-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen Biotech Inc . Tremfya: package insert. Horsham, PA, 2020. https://www.janssenlabels.com/package-insert/product-monograph/prescribing-information/TREMFYA-pi.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehncke W-H, Brembilla NC, Nissen MJ. Guselkumab: the first selective IL-23 inhibitor for active psoriatic arthritis in adults. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2021;17:5–13. 10.1080/1744666X.2020.1857733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deodhar A, Helliwell PS, Boehncke W-H, et al. Guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who were biologic-naive or had previously received TNFα inhibitor treatment (DISCOVER-1): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1115–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30265-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchlin CT, Helliwell PS, Boehncke W-H, et al. Guselkumab, an inhibitor of the IL-23p19 subunit, provides sustained improvement in signs and symptoms of active psoriatic arthritis: 1 year results of a phase III randomised study of patients who were biologic-naïve or TNFα inhibitor-experienced. RMD Open 2021;7:e001457. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mease PJ, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Guselkumab in biologic-naive patients with active psoriatic arthritis (DISCOVER-2): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2020;395:1126–36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30263-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McInnes IB, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an interleukin-23p19-specific monoclonal antibody, through one year in biologic-naive patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;73:604–16. 10.1002/art.41553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McInnes IB, Rahman P, Gottlieb AB, et al. Long-Term efficacy and safety of guselkumab, a monoclonal antibody specific to the P19 subunit of interleukin-23, through 2 years: results from a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in biologic-naïve patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2021;74:475–85. 10.1002/art.42010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reich K, Gordon KB, Strober BE, et al. Five-year maintenance of clinical response and health-related quality of life improvements in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis treated with guselkumab: results from VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2. Br J Dermatol 2021;185:1146–59. 10.1111/bjd.20568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blauvelt A, Tsai T-F, Langley RG, et al. Consistent safety profile with up to 5 years of continuous treatment with guselkumab: pooled analyses from the phase 3 VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 trials of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.11.004. [Epub ahead of print: 17 Nov 2021]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Højgaard P, Glintborg B, Kristensen LE, et al. The influence of obesity on response to tumour necrosis factor-α inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis: results from the DANBIO and ICEBIO registries. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:2191–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kew326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giles JT, Ogdie A, Gomez Reino JJ, et al. Impact of baseline body mass index on the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in patients with psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open 2021;7:e001486. 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad A, Gazitt T, Feldhamer I, et al. Treatment persistence of biologics among patients with psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2021;23:44. 10.1186/s13075-021-02417-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navarini L, Costa L, Tasso M, et al. Retention rates and identification of factors associated with anti-TNFα, anti-IL17, and anti-IL12/23R agents discontinuation in psoriatic arthritis patients: results from a real-world clinical setting. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:2663–70. 10.1007/s10067-020-05027-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geale K, Lindberg I, Paulsson EC, et al. Persistence of biologic treatments in psoriatic arthritis: a population-based study in Sweden. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2020;4:rkaa070. 10.1093/rap/rkaa070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glintborg B, Loft AG, Omerovic E, et al. To switch or not to switch: results of a nationwide guideline of mandatory switching from originator to biosimilar etanercept. One-year treatment outcomes in 2061 patients with inflammatory arthritis from the DANBIO registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2019;78:192–200. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrold LR, Stolshek BS, Rebello S, et al. Impact of prior biologic use on persistence of treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis enrolled in the US Corrona registry. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:895–901. 10.1007/s10067-017-3593-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merola JF, Lockshin B, Mody EA. Switching biologics in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017;47:29–37. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Foley P, et al. Efficacy of guselkumab in subpopulations of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: a pooled analysis of the phase III VOYAGE 1 and VOYAGE 2 studies. Br J Dermatol 2018;178:132–9. 10.1111/bjd.16008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, et al. American College of rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35. 10.1002/art.1780380602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Lange ML, et al. Should improvement in rheumatoid arthritis clinical trials be defined as fifty percent or seventy percent improvement in core set measures, rather than twenty percent? Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1564–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman SR, Krueger GG. Psoriasis assessment tools in clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64 Suppl 2:ii65–8. 10.1136/ard.2004.031237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langley RGB, Feldman SR, Nyirady J, et al. The 5-point Investigator's Global Assessment (IGA) scale: a modified tool for evaluating plaque psoriasis severity in clinical trials. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26:23–31. 10.3109/09546634.2013.865009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chandran V, Bhella S, Schentag C, et al. Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:936–9. 10.1136/ard.2006.065763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol 2005;23:S14–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helliwell PS, FitzGerald O, Fransen J, et al. The development of candidate composite disease activity and responder indices for psoriatic arthritis (GRACE project). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:986–91. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coates LC, Fransen J, Helliwell PS. Defining minimal disease activity in psoriatic arthritis: a proposed objective target for treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:48–53. 10.1136/ard.2008.102053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nas K, Capkin E, Dagli AZ, et al. Gender specific differences in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2017;27:345–9. 10.1080/14397595.2016.1193105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Queiro R, Tejón P, Coto P, et al. Clinical differences between men and women with psoriatic arthritis: relevance of the analysis of genes and polymorphisms in the major histocompatibility complex region and of the age at onset of psoriasis. Clin Dev Immunol 2013;2013:482691. 10.1155/2013/482691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mease PJ. Fibromyalgia, a missed comorbidity in spondyloarthritis: prevalence and impact on assessment and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2017;29:304–10. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braaten TJ, Zhang C, Presson AP, et al. Gender differences in psoriatic arthritis with fatigue, pain, function, and work disability. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis 2019;4:192–7. 10.1177/2475530319870776 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krajewska-Włodarczyk M, Owczarczyk-Saczonek A, Placek W. Prevalence and severity of fatigue in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Adv Dermatol Allergol 2020;37:46–51. 10.5114/ada.2019.83629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tobin AM, Sadlier M, Collins P, et al. Fatigue as a symptom in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: an observational study. Br J Dermatol 2017;176:827–8. 10.1111/bjd.15258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passia E, Vis M, Coates LC, et al. Sex-specific differences and how to handle them in early psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2022;24:22. 10.1186/s13075-021-02680-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cañete JD, Tasende JAP, Laserna FJR, et al. The impact of comorbidity on patient-reported outcomes in psoriatic arthritis: a systematic literature review. Rheumatol Ther 2020;7:237–57. 10.1007/s40744-020-00202-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gudu T, Gossec L. Quality of life in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14:405–17. 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1468252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh S, Facciorusso A, Singh AG, et al. Obesity and response to anti-tumor necrosis factor-α agents in patients with select immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0195123. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.di Minno MND, Peluso R, Iervolino S, et al. Obesity and the prediction of minimal disease activity: a prospective study in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:141–7. 10.1002/acr.21711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pantano I, Iacono D, Favalli EG, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in patients with PSA is not dependent on patients' body mass index. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:e42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pirro F, Caldarola G, Chiricozzi A, et al. Impact of body mass index on the efficacy of biological therapies in patients with psoriasis: a real-world study. Clin Drug Investig 2021;41:917–25. 10.1007/s40261-021-01080-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McInnes IB, Chakravarty SD, Apaolaza I, et al. Efficacy of ustekinumab in biologic-naïve patients with psoriatic arthritis by prior treatment exposure and disease duration: data from PSUMMIT 1 and PSUMMIT 2. RMD Open 2019;5:e000990. 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-000990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Husted JA, Tom BD, Farewell VT, et al. A longitudinal study of the effect of disease activity and clinical damage on physical function over the course of psoriatic arthritis: does the effect change over time? Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:840–9. 10.1002/art.22443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Vlam K, Merola JF, Birt JA, et al. Skin involvement in psoriatic arthritis worsens overall disease activity, patient-reported outcomes, and increases healthcare resource utilization: an observational, cross-sectional study. Rheumatol Ther 2018;5:423–36. 10.1007/s40744-018-0120-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Strober B, Menter A, Leonardi C, et al. Efficacy of risankizumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis by baseline demographics, disease characteristics and prior biologic therapy: an integrated analysis of the phase III UltIMMa-1 and UltIMMa-2 studies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020;34:2830–8. 10.1111/jdv.16521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glintborg B, Østergaard M, Dreyer L, et al. Treatment response, drug survival, and predictors thereof in 764 patients with psoriatic arthritis treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor α therapy: results from the nationwide Danish DANBIO registry. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:382–90. 10.1002/art.30117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rahman P, Ritchlin CT, Helliwell PS, et al. Pooled safety results through 1 year of 2 phase III trials of guselkumab in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2021;48:1815–23. 10.3899/jrheum.201532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coates LC, Gossec L, Theander E, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab in patients with active psoriatic arthritis who are inadequate responders to tumour necrosis factor inhibitors: results through one year of a phase IIIB, randomised, controlled study (COSMOS). Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:359–69. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-220991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2022-002195supp001.pdf (92.3KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2022-002195supp002.pdf (114.8KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2022-002195supp003.pdf (90.5KB, pdf)

rmdopen-2022-002195supp004.pdf (94.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sharing policy of Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson is available at http://www.janssen.com/clinical-trials/transparency. As noted on this site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted through Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project site at http://yoda.yale.edu.