Abstract

Background

Urinary dipsticks are sometimes used for screening asymptomatic people, and for case‐finding among inpatients or outpatients who do not have genitourinary symptoms. Abnormalities identified on screening sometimes lead to additional investigations, which may identify serious disease, such as bladder cancer and chronic kidney disease (CKD). Urinary dipstick screening could improve prognoses due to earlier detection, but could also lead to unnecessary and potentially invasive follow‐up testing and unnecessary treatment.

Objectives

We aimed to quantify the benefits and harms of screening with urinary dipsticks in general populations and patients in hospitals.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register to 8 September 2014 through contact with the Trials Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials and other study types that compared urinary dipstick screening with no dipstick screening were eligible for inclusion. We searched for studies that investigated the use of urinary dipsticks for detecting haemoglobin, protein, albumin, albumin‐creatinine ratio, leukocytes, nitrite, or glucose, alone or in any combination, and in any setting. We planned to exclude studies conducted in patients with urinary disorders.

Data collection and analysis

It was planned that two authors would independently extract data from included studies and assess risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. However, no studies met our inclusion criteria.

Main results

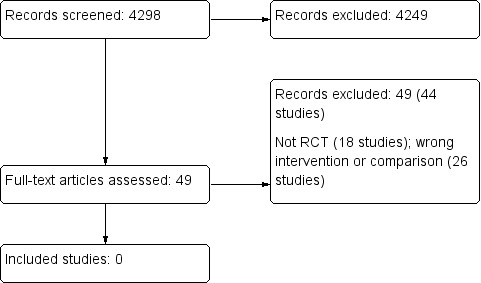

Literature searches to 8 September 2014 yielded 4298 records, of which 4249 were excluded following title and abstract assessment. There were 49 records (44 studies) eligible for full text assessment; of these 18 studies were not RCTs and 26 studies compared interventions or controls that were not relevant to this review. Thus, no studies were eligible for inclusion.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence to assess the benefits and harms of screening with urinary dipsticks, which remain unknown.

Keywords: Humans; Reagent Kits, Diagnostic; Kidney Diseases; Kidney Diseases/diagnosis; Kidney Diseases/urine

Plain language summary

Screening with urinary dipsticks for reducing morbidity and mortality

Urinary dipsticks are sometimes used for screening healthy people and patients that do not have symptoms of urinary disease. Urinary dipsticks can be used to test for several different substances, such as blood, sugar, protein, white blood cells and nitrite in the urine, which may indicate the presence of disease. Identified abnormalities sometimes lead to additional investigations, which may identify serious disease, such as bladder cancer and chronic kidney disease. Detection could improve health outcomes from finding disease at earlier stages, but could also lead to unnecessary follow‐up testing, which may be invasive, and lead to unnecessary treatment.

We searched the literature to September 2014 to identify studies that compared urinary dipstick screening with no dipstick screening. However, we found no studies that met our inclusion criteria. We were unable to determine benefits and harms associated with urinary dipstick screening.

Background

Urinary dipstick testing is widely used to screen for the presence of disease with the aim of reducing morbidity and mortality in both healthy people and patients (Grønhøj Larsen 2010; Merenstein 2006; Prochazka 2005). Dipsticks can test for either single or multiple substances in urine, and are sometimes used in general health checks.

Urinary dipstick testing is recommended for screening people with diabetes to detect a specific protein (albumin) in the urine (albuminuria) (NICE 2008b). Another potential screening population is people with high blood pressure (hypertension). At present, there is a lack of consensus on these recommendations, and most guidelines recommend use of albumin‐creatinine or protein‐creatinine ratios rather than dipsticks to detect proteinuria or albuminuria. However, dipsticks are less expensive than these tests and dipstick proteinuria is strongly related to total and cardiovascular mortality (CKDPC 2010). Screening with urine culture is recommended for pregnant women to detect bacteria in the urine (bacteriuria) (Lin 2008; NICE 2008a).

Since the 1970s, school children and employed adults in Japan have been offered urinary dipstick screening for blood and protein; from 1983, this was extended to all adults aged 40 years and over (Imai 2007). Taiwan implemented dipstick screening for children in 1990, and Korea in 1998 (Hogg 2009).

There appear to be no recommendations for population‐based screening with urinary dipsticks, and the scientific debate persists about screening for CKD with other methods (Brown 2011). Opportunistic screening is often recommended, but only for high risk groups (Krogsbøll 2014). A systematic review of screening for CKD with any method found no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and concluded that the role of screening was uncertain (Fink 2012).

There is, however, discrepancy between recommendations and practice. Ease of use, low cost, and the perceived test safety may contribute to this discrepancy. Although screening can work (Holme 2013; Raffle 2003; Thomason 1998), it is noteworthy that experience with other screening interventions for diseases such as prostate cancer (Djulbegovic 2010), breast cancer (Gøtzsche 2013), and neuroblastoma (Schilling 2002; Woods 2002) have indicated that screening benefits can be less than expected, and that screening can cause more harm than good.

Dipstick testing is routinely used for case‐finding among people with conditions that increase the risk of kidney disease, such as diabetes and hypertension. Both have wide spectrums of severity, do not often cause symptoms, and encompass a large proportion of adults. Definitions for these conditions are derived through consensus, and have been the subject of debate as they have been broadened over time. Thus, case‐finding in such broad categories borders on screening, but RCTs are unlikely to be performed and the question must therefore be informed by detailed analysis of observational studies, which is outside the scope of this review.

Description of the condition

Microscopic blood in urine (haematuria) can be caused by urological cancers of any kind, but because bladder cancer is relatively common, and haematuria a frequent sign, most research has centred on detecting blood. The prognosis for people with bladder cancer is highly dependent on the extent of invasion into the bladder wall; in contrast to muscle‐invasive lesions, non‐muscle‐invasive lesions often have a favourable prognosis following minimally invasive treatment. However, unexpected post mortem findings are less common than for other urological cancers, such as prostate and kidney cancers (Avgerinos 2001; Karwinski 1990), which suggests that bladder cancer may have a short preclinical phase, possibly rendering it a poor target for screening. Furthermore, microscopic haematuria is not a robust marker for bladder cancer because it can be associated with a plethora of benign conditions (Malmström 2003), and novel markers have not yet been tested sufficiently.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major health problem with a long preclinical phase. Staging is based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and evidence of kidney damage, such as proteinuria or pathological findings with ultrasound imaging (NKF 2002). When this staging formula was applied to the adult population in the United States, CKD prevalence was found to be 13%, and more than 45% among people over 70 years of age (Coresh 2007). Although most people with CKD do not go on to develop end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD), its prevalence is increasing (Hemmelgarn 2006). It has been argued that the current staging system is inappropriate because many people with CKD have low eGFR but no evidence of kidney damage (Moynihan 2013). Low eGFR could be considered normal, particularly among older people, most of whom are unlikely to develop symptomatic kidney disease (Bauer 2008).

It has been reported that proteinuria detected using urinary dipsticks was associated with subsequent ESKD (Iseki 2003) and the test can identify some people who are at risk of rapid decline in kidney function (Clark 2011). It has also been reported that asymptomatic microscopic haematuria is associated with ESKD (Iseki 2003; Vivante 2011). Both low eGFR and proteinuria are risk factors for cardiovascular and all‐cause mortality (Hillege 2001; Matsushita 2010); although they do not seem to substantially improve traditional prediction tools (Chang 2011).

Diabetes mellitus can cause glycosuria, and early detection may prevent or postpone complications such as blindness, neuropathy or cardiovascular disease through early treatment and weight loss. A study of screening for diabetes using other methods than dipsticks did not find beneficial effects (Simmons 2012a).

Asymptomatic bacteriuria may be detected with dipstick testing for leukocytes and nitrite, but detection in urine are common findings, particularly among older people, and treatment is not recommended in the absence of symptoms. On the other hand, urinary tract infections (UTI) can present with vague and uncharacteristic symptoms. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria is recommended only for pregnant women and before genitourinary procedures (EAU 2012; Lin 2008).

How the intervention might work

Although many variations exist, the urinary dipsticks commonly used in general health checks usually test for at least haemoglobin, protein or albumin, leukocytes, nitrite and glucose. In screening, the use of a combined urinary dipstick is in some ways comparable with a general health check, which also includes components with different potentials for benefits and harms for a range of very different diseases. Likewise, there is a wide range of relatively harmless conditions that can result in an abnormal test.

Benefits

The potential benefits from dipstick screening are well known. Many diseases screened for using urinary dipsticks are both common and serious. Early diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and appropriate interventions and lifestyle changes may reduce common comorbidities such as blindness, neuropathy, kidney disease, or cardiovascular disease. Identification of CKD may allow early therapy to reduce morbidity and mortality, although a Cochrane review concluded that the value of treating CKD stages 1 to 3 with angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors remains unclear (Sharma 2011). Glomerulonephritis often responds to treatment but it has not been shown if treatment of subclinical glomerulonephritis improves prognosis. If detection of microscopic haematuria enables earlier detection of bladder cancer, morbidity, mortality and harmful effects of invasive treatments for advanced disease may be reduced.

Harms

Harms from dipstick screening mainly relate to superfluous follow‐up tests and therapeutic interventions, and not the screening itself. Harms include discomfort and anxiety related to non‐invasive follow‐up tests such as kidney ultrasound, and from concerns about possible health issues, but most importantly, the possibility of morbidity related to unnecessary invasive investigations.

Investigations for persistent microscopic haematuria often include flexible cystoscopy in local anaesthesia, computed tomography imaging (CT scan) of the urinary tract, and urine cytology. In some instances, rigid cystoscopy and biopsy under general anaesthesia may be required, which carries a risk of complications such as bladder perforation, bleeding, and infection. The initial nephrological work‐up of patients with proteinuria or microscopic haematuria may suggest the need for kidney biopsy, which carries a risk of serious complications such as haemorrhage.

Imaging of the abdomen may reveal unexpected abnormalities, which can lead to further investigations (Furtado 2005). A study of CT colonography reported that the prevalence of incidental abnormalities was very high, around 40%, which led to additional investigations in 14% of cases (Xiong 2005). Even when serious abnormalities such as cancer are found incidentally, there is no guarantee that this improves prognosis (Welch 2004).

Common to all conditions that may be detected using urinary dipstick testing is a risk that the identified condition would never have caused symptoms in the person's remaining lifetime (over‐diagnosis), and that the diagnosis therefore will not improve prognosis, but instead lead to unnecessary worry and over treatment with inherent harms. Over‐diagnosis and over‐treatment are documented in screening for breast cancer (Gøtzsche 2013; Jørgensen 2009), prostate cancer (Djulbegovic 2010), lung cancer, melanoma, and thyroid cancer (Welch 2010). Although the concepts of over‐diagnosis and over‐treatment are most familiar in cancer screening, they also apply to screening for other conditions such as hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes (Welch 2011), and CKD (Moynihan 2013).

The possibility of adverse psychological effects associated with diagnostic tests and treatment must also be considered as a potential harm, as well as the impact of negative screening results on providing a false sense of security, with the possibility of some people ignoring important symptoms.

Why it is important to do this review

The possible benefits of urinary dipstick screening must be weighed against possible harms. The main question is whether screening reduces morbidity and mortality and if the harms are acceptable.

Our review planned to investigate the use of urinary dipsticks to screen healthy people and hospital in‐ or outpatients for the presence of disease. Our main interest was the effects of combined dipsticks use, but we anticipated that the existing literature would be scant and therefore also planned to assess RCTs of screening for individual components of dipsticks, such as blood or protein.

This review focused on clinical outcomes that are relevant to people, such as mortality and ESKD.

Objectives

We aimed to quantify the benefits and harms of screening with urinary dipsticks in general populations and in patients at hospitals.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and other studies in which allocation to screening with urinary dipsticks or no screening was obtained using alternation (e.g. alternate medical records), date of birth or similar methods were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We did not impose age limitations and included studies from both general and patient populations. We included studies of screening using urinary dipsticks performed as part of a health check, such as in general practice or at the community level, as well as studies of screening hospital in‐ or outpatients, and patients in non‐hospital specialist clinics.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded studies where dipstick testing was done on indication, e.g. in people with suspected UTI, as well as studies conducted exclusively in populations of patients with urinary diseases because the pretest probability of disease would be high. Dipstick testing in these situations could also be viewed more properly as diagnostic testing rather than screening.

Types of interventions

We included studies of single or repeat use of urinary dipstick screening that tested for one or more of the following: haemoglobin, protein, albumin, albumin‐creatinine ratio, glucose, leukocytes and nitrite. We included studies regardless of who performed the test, such as healthcare professionals or study participants (following instruction).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

All‐cause mortality

Cardiovascular mortality

Cancer mortality

ESKD (patients requiring renal replacement therapy, i.e. dialysis or kidney transplantation).

Secondary outcomes

Admission to hospital

Drug therapy

Surgery

New diagnoses (cancers, including cancer stages, urolithiasis, CKD (stages 1 to 3), CKD (stages 4 and 5), diabetes mellitus, bacteriuria)

Follow‐up investigations resulting from a positive test

Complications to follow‐up investigations

Self‐reported health

Quality of life

Disability.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Renal Group's Specialised Register to 8 September 2014 through contact with the Trials Search Co‐ordinator using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Renal Group’s Specialised Register contains studies identified from sources.

Quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials CENTRAL

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of renal‐related journals and the proceedings of major renal conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected renal journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of the Cochrane Renal Group. Details of these strategies as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts are available in the Specialised Register section of information about the Cochrane Renal Group.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors who discarded studies that were clearly not eligible and assessed the full text of potentially eligible studies to determine which satisfied inclusion criteria. Disagreements were to be resolved through discussion, with the third author as arbiter when necessary.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was to be carried out independently by two authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were to be translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were to be grouped together and the publication with the most complete data used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were to be used. Any discrepancies between published versions were to be highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We planned to assess risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study (detection bias)?

Participants and personnel

Outcome assessors

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (mortality, ESKD), we planned to use the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For measurement scale outcomes (self‐reported health, quality of life, disability), we planned to use the mean difference (MD), or the standardised mean difference (SMD) if different scales were used. Some outcomes may have been reported in various ways (admission to hospital, drug therapy, surgery, new diagnoses, follow‐up investigations, complications to follow‐up investigations), such as rates, continuous, or dichotomous outcomes. We planned to choose the format that would have informed the best synthesis of available results.

For measurement scale outcomes, we planned to extract both change from baseline and final means when available. Missing standard deviations were planned to have been estimated from similar studies, when possible. Time‐to‐event data were planned to be treated as dichotomous data, because the relevant outcomes (mortality, ESKD) were likely to have been ascertained for all participants.

Unit of analysis issues

We planned to include cluster RCTs, and when possible, extract effect measures and standard error rates from an analysis that takes clustering into account. If that was not possible, we planned to extract the number of clusters and estimate the intra‐cluster correlation coefficient to inform a reliable analysis. If this was not possible, we planned to disregard the clustering and investigate the effect of this in a sensitivity analysis.

Dealing with missing data

We planned to extract data for intention‐to‐treat analyses (ITT) and contact authors if required information was missing. Where ITT analysis was not possible, we planned to extract data from an available case analysis and assess the risk of bias from attrition.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to analyse heterogeneity using a Chi² test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance, and the I² statistic (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not expect that a sufficient number of studies would be identified to create a useful funnel plot. Assessing reporting bias is difficult, but we planned to note whether outcomes that we considered important were reported. We planned to contact authors about possible unpublished outcomes.

Data synthesis

We planned to use a random‐effects model and to express the results as both relative risks and number‐needed‐to‐screen to achieve the relevant outcomes, both beneficial and harmful.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform the following subgroup analyses.

Risk of bias

Substances tested for (e.g. haemoglobin, protein/albumin or albumin‐creatinine ratio, glycosuria, leukocytes/nitrite, or combinations of substances)

Population type (general populations, pregnant women, patients)

Age of participants.

Sensitivity analysis

If possible, we planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Excluding cluster RCTs

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Searches yielded 4298 records, of which 4249 were excluded based on title and abstract (Figure 1). We identified 49 records (44 studies) for possible inclusion and full‐text assessment. These were either not RCTs (18 studies) or compared interventions or controls that were not relevant to this review (26 studies) (Characteristics of excluded studies). Thus, no studies could be included in this review.

1.

Study flow diagram

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias assessment could not be conducted.

Effects of interventions

No studies met our inclusion criteria.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found no studies that compared screening with urinary dipsticks with no screening. Screening with urinary dipsticks for haemoglobin, protein, albumin, albumin‐creatinine ratio, leukocytes, nitrite, or glucose, alone or in any combination, has unknown benefits and harms.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

General populations

The older observational literature is mainly concerned with assessing the diagnostic yield, or exploring the feasibility and cost of screening programs, tacitly implying that any discovery of asymptomatic illness is beneficial. Given knowledge about over‐diagnosis and over‐treatment associated with several types of screening tests (Black 2010; Independent UK Panel 2012; Welch 2011) and their sometimes disappointing benefits (Djulbegovic 2010; Gøtzsche 2013; Krogsbøll 2012a; Schilling 2002; Simmons 2012; Woods 2002) such an assumption is not warranted.

Some studies avoided this assumption, but used methods that did not enable reliable conclusions to be made about benefits and harms. Japanese urine screening programs for children and adults that used dipstick testing for haemoglobin and protein were implemented in the 1970s. An analysis of incidence rates of ESKD in Japan, using data from a nationwide dialysis registry from 1983 to 2000, found steadily increasing incidence rates during the entire period (Wakai 2004). This rise was mainly due to diabetic kidney disease, nephrosclerosis, and unknown causes, while ESKD due to glomerulonephritis rose until the mid‐1990s, where it started to decline. This observation is compatible with the hypothesis that screening caused the decline, given the expected latency of effect, but other explanations are also possible, such as a decrease in incidence of glomerulonephritis or the implementation of possibly useful treatments for glomerulonephritis (Reid 2011; Samuels 2003). We have not found studies that compared the incidence of glomerulonephritis before and after the introduction of the Japanese screening programs in the 1970s, and an increase in incidence caused by detection of asymptomatic cases is also possible, as glomerulonephritis, particularly immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy, can remain subclinical.

Comparisons between countries are difficult to interpret because of variations in biopsy policies, and a systematic review of glomerulonephritis incidence found very large variations (McGrogan 2011). For example, five studies reported the incidence of IgA nephropathy in children: four non‐screening studies and one screening study. In the non‐screening studies, the incidence ranged between 0.03/100,000/year and 0.57/100,000/year and the screening study found 4.5/100,000/year.

The prognosis of children with screening‐detected glomerular disease appears to be good (Ito 1990), and better than for symptomatic cases (Takebayashi 1992). This could be due to effective treatments arresting or slowing the disease at an early stage, but it could also reflect over diagnosis of subclinical cases, that is, cases that would not have become symptomatic if not discovered by screening, or length bias (screening preferentially detects less aggressive disease as there is more time to detect these cases).

Messing 2006 compared long‐term outcomes of bladder cancer detected through screening with outcomes of clinically detected bladder cancer and found dramatic differences in mortality between men with screen‐detected cancers and men with cancers not detected by screening. However, the populations were probably not comparable because the risk of death from other causes than bladder cancer was smaller among the men with screen detected cancers, which suggests selection bias. Furthermore, the possibility of over‐diagnosis of less aggressive tumours has not been ruled out, and this would also confer a spurious survival advantage to the screened group.

The observations that proteinuria and eGFR are clearly and consistently associated with the risk of ESKD, myocardial infarction, acute kidney injury, and death suggest that screening could be beneficial (Hemmelgarn 2010; James 2010). However, such observations do not resolve the classic screening‐related questions, e.g. whether the efficacy of treating screening‐detected disease is similar to what is observed in studies of disease not detected in screening, whether the compliance with both screening and preventive treatments is adequate in asymptomatic persons, how much over‐diagnosis the screening causes, and whether the benefits outweigh the harms. A simulation study of screening for proteinuria found that it was cost‐effective when targeted to people with hypertension, those aged over 60 years, or when conducted at the infrequent interval of 10 years (Boulware 2003). However, many assumptions are needed for simulation studies, and they cannot constitute proof.

A review of general health checks (Krogsbøll 2012a) included five studies (19,813 participants) that contained screening with a urinary dipstick as part of the intervention (Engberg 2002; Friedman 1986; Lannerstad 1977; Olsen 1976; Tibblin 1982). These studies did not find beneficial effects on morbidity or mortality. Friedman 1986 (which included 10,674 participants and 16 years of follow‐up) reported cause‐specific mortality in detail and did not find effects on deaths from genitourinary disease, or in other cancers, which included cancers of the bladder, kidney and ureter. The studies were likely underpowered to detect small beneficial effects of dipstick screening.

Hospitalised patients and outpatients

A cohort study of dipstick testing in medical outpatients without relevant symptoms, found that 17% had an abnormal result, but that management was changed as a result of this finding in only 0.7% of cases. (Rüttimann 1994) Three older cohorts assessed routine urine microscopy and similarly found many abnormal test results but few consequences for management (Boland 1995; Boland 1996; Kroenke 1986).

High risk patients

A special issue is case‐finding in people with known conditions that are strongly associated with kidney disease where screening borders on monitoring the development of a disease. Although we found no RCT evidence for such populations, this practice may be justified when the association is very strong, such as with diabetes mellitus. Also, this practice is so ubiquitous that randomised trials are unlikely to be conducted. Exactly what level of risk justifies case‐finding in high‐risk groups is not clear and is not the topic of this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We found no trials that investigated dipstick screening versus no dipstick screening, and therefore the benefits and harms remain unknown. Because there are potential harms related to dipstick screening, and since any screening program entails financial and opportunity costs, the findings of our review justify the use of dipstick screening in non‐pregnant persons only in the context of a study setting. This conclusion does not address dipstick testing done on clinical indications such as fever, or in high risk patients such as people with diabetes.

Implications for research.

Conduct of RCTs are feasible for routine screening of healthy people, hospital inpatients and outpatients because the intervention is widespread but not standard of care. Careful consideration to ensure that studies are adequately powered is needed for future studies.

Feedback

Comment, 10 March 2015

Summary

Thank you for this recent Cochrane review regarding screening with urinary dipsticks. I was puzzled by the assertion that "Urinary dipstick testing is recommended for screening pregnant women to detect bacteria in the urine (bacteriuria) (Lin 2008; NICE 2008a)".

Certainly the NICE guideline states that "1.8.1.1 New Women should be offered routine screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria by midstream urine culture early in pregnancy. Identification and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria reduces the risk of pyelonephritis." Of note, it says that screening should be by midstream urine culture, not by dipstick.

The NICE guideline recommends the use of dipstick for protein at each antenatal visit to screen for pre‐eclampsia (rather than bacteriuria). If there is an alternative reference in the NICE guideline that you found as evidence of a recommendation to screen for asymptomatic bacteriuria with dipstick, please could you indicate where it is?

I agree with the conflict of interest statement below:

I certify that I have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of my feedback.

Jane Currie

Reply

Thank you for pointing out this error. Both the NICE guideline and the 2008 USPSTF statement recommends screening pregnant women with urine culture, not dipstick. We have now corrected this.

Lasse Krogsbøll

Karsten Juhl Jørgensen

Peter C Gøtzsche

Contributors

Comment: Jane Currie

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 14 April 2015 | Amended | Feedback incorporated ‐ correction of background |

| 14 April 2015 | Feedback has been incorporated | Responded to feedback and incorporated minor edit to background |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank:

The Cochrane Renal Group.

The referees for their comments and feedback during the preparation of this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Electronic search strategies

| Database | Search terms |

| CENTRAL |

|

| MEDLINE |

|

| EMBASE |

|

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment tool

| Potential source of bias | Assessment criteria |

|

Random sequence generation Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate generation of a randomised sequence |

Low risk of bias: Random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization (minimization may be implemented without a random element, and this is considered to be equivalent to being random). |

| High risk of bias: Sequence generated by odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; sequence generated by hospital or clinic record number; allocation by judgement of the clinician; by preference of the participant; based on the results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; by availability of the intervention. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement. | |

|

Allocation concealment Selection bias (biased allocation to interventions) due to inadequate concealment of allocations prior to assignment |

Low risk of bias: Randomisation method described that would not allow investigator/participant to know or influence intervention group before eligible participant entered in the study (e.g. central allocation, including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation; sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes). |

| High risk of bias: Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or non‐opaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear: Randomisation stated but no information on method used is available. | |

|

Blinding of participants and personnel Performance bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by participants and personnel during the study |

Low risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Blinding of outcome assessment Detection bias due to knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors. |

Low risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. |

| High risk of bias: No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Incomplete outcome data Attrition bias due to amount, nature or handling of incomplete outcome data. |

Low risk of bias: No missing outcome data; reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods. |

| High risk of bias: Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; for dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; for continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘as‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; potentially inappropriate application of simple imputation. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Selective reporting Reporting bias due to selective outcome reporting |

Low risk of bias: The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way; the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk of bias: Not all of the study’s pre‐specified primary outcomes have been reported; one or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not pre‐specified; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect); one or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis; the study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to permit judgement | |

|

Other bias Bias due to problems not covered elsewhere in the table |

Low risk of bias: The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| High risk of bias: Had a potential source of bias related to the specific study design used; stopped early due to some data‐dependent process (including a formal‐stopping rule); had extreme baseline imbalance; has been claimed to have been fraudulent; had some other problem. | |

| Unclear: Insufficient information to assess whether an important risk of bias exists; insufficient rationale or evidence that an identified problem will introduce bias. |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Allen 1991 | Wrong intervention. Compared urinary glucose monitoring in diabetes with blood glucose monitoring |

| Apoola 2009 | Wrong intervention. Compared partner notification with urethral swab and urine antigen testing |

| Balogun 2011 | Not RCT |

| Battelino 2011 | Wrong intervention. Compared blood glucose meter with continuous blood glucose monitoring for children with type 1 diabetes |

| Beatty 1994 | Not RCT |

| Bubner 2009 | Wrong intervention. Compared point‐of‐care testing with laboratory testing in general practice |

| Calderon‐Margalit 2005 | Not RCT |

| Calero 2011 | Not RCT |

| Charles 2009 | Wrong intervention. Compared intensified treatment of people with screen‐detected diabetes with usual care |

| Dallosso 2012 | Wrong intervention. Compared monitoring with blood glucose or urine testing for people with type 2 diabetes |

| Davies 1991 | Wrong intervention. No unscreened control group. Compared two different methods of screening for glycosuria |

| Davies 1993 | Not RCT |

| Davies 1999 | Not RCT |

| Diercks 2002 | Wrong intervention. Factorial design that compared fosinopril, pravastatin and placebo in people with elevated urinary albumin excretion |

| Dolan 1987 | Wrong intervention. Compared urinary glucose monitoring by dipstick with urine glucose monitoring by tablet system |

| Downing 2012 | Not RCT |

| DPPRG 2005 | Wrong intervention. Compared lifestyle intervention, metformin, and placebo for prevention of diabetes in people with elevated fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance |

| Falguera 2010 | Wrong intervention. Compared empirical treatment of pneumonia with targeted treatment based on urine antigen testing |

| Fulcher 1991 | Not RCT |

| Gallichan 1994 | Wrong intervention. Compared blood glucose monitoring with urine dipstick monitoring in patients with type 2 diabetes |

| Goldby 2011 | Not RCT |

| Grimm 1997 | Wrong comparison. Both groups had dipstick testing |

| Jolic 2011 | Not RCT |

| Jou 1998 | Not RCT |

| Kazemier 2012 | Wrong intervention. Compared antibiotic treatment with no treatment in pregnant women with asymptomatic bacteriuria |

| Kenealy 2005 | Wrong intervention. Compared patient reminders, computer reminders, both reminders, and usual care, for screening for diabetes |

| Koschinsky 1984 | Wrong intervention. Compared urinary and blood glucose testing in diabetics. Both groups tested for urinary glucose for 4 weeks and then for blood glucose for 4 weeks |

| Lauritzen 1994 | Wrong intervention. Described variation in albumin‐creatinine ratio in the RCT screened arms |

| Lauritzen 2008 | Wrong intervention. Compared health checks, health checks and lifestyle conversations, and usual care |

| Lenz 2002 | Wrong comparison. Compared nurse practitioner and physician treatment of diabetes |

| Little 2009 | Wrong intervention. Compared five different management strategies for suspected UTI |

| McEwan 1990 | Wrong intervention. Dipstick screening was part of a complex intervention |

| McGhee 1997 | Not RCT |

| Messing 1995 | Not RCT |

| Morris 2012 | Not RCT. Systematic review of diagnostic studies comparing spot protein‐creatinine ratio with 24 hour protein‐creatinine ratio for screening pregnant women |

| Naimark 2001 | Wrong intervention. Tested education directed towards physicians to increase their microalbuminuria testing pattern among people with type 2 diabetes. |

| Neumann 2008 | Wrong intervention. Compared urine microscopy with a malaria dipstick |

| Nevedomskaya 2011 | Not RCT |

| Ochoa 2007 | Not RCT |

| Reyburn 2007 | Wrong intervention. Compared urine microscopy and a rapid diagnostic test for malaria |

| Schwab 1992 | Not RCT |

| Simmons 2012 | Wrong intervention. Compared screening for diabetes with no screening for diabetes (no dipsticks) |

| Tissot 2001 | Not RCT |

| Worth 1982 | Wrong intervention. Compared dipstick testing for glycosuria with dipstick testing for glycosuria combined with one of two methods for blood glucose measurements. Used cross‐over design. Included people with known diabetes |

RCT ‐ randomised controlled trial; UTI ‐ urinary tract infection

Contributions of authors

Drafting the protocol: LTK, KJ, PCG

Study selection: LTK, KJ

Extract data from studies: LTK, KJ

Enter data into RevMan: LTK

Carry out the analysis: not performed

Interpret the analysis: not performed

Draft the final review: LTK, KJ, PCG

Disagreement resolution: not performed

Update the review: LTK

Declarations of interest

Lasse T Krogsbøll: none known

Karsten Juhl Jørgensen: none known

Peter C Gøtzsche: none known.

Edited (no change to conclusions), comment added to review

References

References to studies excluded from this review

Allen 1991 {published data only}

- Allen BT, DeLong ER, Feussner JR. Impact of glucose self‐monitoring on non‐insulin‐treated patients with type II diabetes mellitus. Randomized controlled trial comparing blood and urine testing. Diabetes Care 1990;13(10):1044‐50. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Apoola 2009 {published data only}

- Apoola A, Beardsley J. Does the addition of a urine testing kit to use of contact slips increase the partner notification rates for genital chlamydial infection?. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2009;20(11):775‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Balogun 2011 {published data only}

- Balogun W, Abbiyesuku FM. Excess renal insufficiency among type 2 diabetic patients with dip‐stick positive proteinuria in a tertiary hospital. African Journal of Medicine & Medical Sciences 2011;40(4):399‐403. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Battelino 2011 {published data only}

- Battelino T, Phillip M, Bratina N, Nimri R, Oskarsson P, Bolinder J. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34(4):795‐800. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beatty 1994 {published data only}

- Beatty OL, Ritchie CM, Hadden DR, Kennedy L, Bell PM, Atkinson AB. Is a random urinary albumin concentration a useful screening test in insulin‐treated diabetic patients?. Irish Journal of Medical Science 1994;163(9):406‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bubner 2009 {published data only}

- Bubner TK, Laurence CO, Gialamas A, Yelland LN, Ryan P, Willson KJ, et al. Effectiveness of point‐of‐care testing for therapeutic control of chronic conditions: results from the PoCT in General Practice Trial. Medical Journal of Australia 2009;190(11):624‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gialamas A, Yelland LN, Ryan P, Willson K, Laurence CO, Bubner TK, et al. Does point‐of‐care testing lead to the same or better adherence to medication? A randomised controlled trial: the PoCT in General Practice Trial. Medical Journal of Australia 2009;191(9):487‐91. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Calderon‐Margalit 2005 {published data only}

- Calderon‐Margalit R, Mor‐Yosef S, Mayer M, Adler B, Shapira SC. An administrative intervention to improve the utilization of laboratory tests within a university hospital. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 2005;17(3):243‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Calero 2011 {published data only}

- Calero A, Katz S, Thomas P, Rosenberg J, Fagan D. Use of screening urine dipsticks in well‐child care to detect asymptomatic proteinuria without proper interpretation leads to unnecessary referral of pediatric patients [abstract no: 816]. Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; 2011 Apr 25‐28; San Diego, CA. 2011. [CENTRAL: CN‐00832172]

Charles 2009 {published data only}

- Charles M, Ejskjaer N, Witte DR, Sandbaek A. Neuropathy in a population with screen‐detected type 2 diabetes [abstract no: 94]. Journal of the Peripheral Nervous System 2009;14(3):254. [EMBASE: 70092065] [Google Scholar]

Dallosso 2012 {published data only}

- Dallosso HM, Eborall HC, Daly H, Martin‐Stacey L, Speight J, Realf K, et al. Does self monitoring of blood glucose as opposed to urinalysis provide additional benefit in patients newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes receiving structured education? The DESMOND SMBG randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Family Practice 2012;13:18. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davies 1991 {published data only}

- Davies M, Alban‐Davies H, Cook C, Day J. Self testing for diabetes mellitus. BMJ 1991;303(6804):696‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davies 1993 {published data only}

- Davies MJ, Williams DR, Metcalfe J, Day JL. Community screening for non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus: self‐testing for post‐prandial glycosuria. Quarterly Journal of Medicine 1993;86(10):677‐84. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Davies 1999 {published data only}

- Davies MJ, Ammari F, Sherriff C, Burden ML, Gujral J, Burden AC. Screening for Type 2 diabetes mellitus in the UK Indo‐Asian population. Diabetic Medicine 1999;16(2):131‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diercks 2002 {published data only}

- Diercks GF, Stroes ES, Boven AJ, Roon AM, Hillege HL, Jong PE, et al. Urinary albumin excretion is related to cardiovascular risk indicators, not to flow‐mediated vasodilation, in apparently healthy subjects. Atherosclerosis 2002;163(1):121‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dolan 1987 {published data only}

- Dolan M, Clarke H, Heffernan A, McKenna TJ. Assessment of home urine sugar tests: sensitivity, frequency of use and effect on diabetes control. Practical Diabetes 1987;4(4):161‐2. [EMBASE: 1988056922] [Google Scholar]

Downing 2012 {published data only}

- Downing H, Thomas‐Jones E, Gal M, Waldron CA, Sterne J, Hollingworth W, et al. The diagnosis of urinary tract infections in young children (DUTY): protocol for a diagnostic and prospective observational study to derive and validate a clinical algorithm for the diagnosis of UTI in children presenting to primary care with an acute illness. BMC Infectious Diseases 2012;12:158. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DPPRG 2005 {published data only}

- Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Strategies to identify adults at high risk for type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 2005;28(1):138‐44. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Falguera 2010 {published data only}

- Falguera M, Ruiz‐González A, Schoenenberger JA, Touzón C, Gázquez I, Galindo C, et al. Prospective, randomised study to compare empirical treatment versus targeted treatment on the basis of the urine antigen results in hospitalised patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Thorax 2010;65(2):101‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fulcher 1991 {published data only}

- Fulcher RA, Maisey SP. Evaluation of dipstick tests and reflectance meter for screening for bacteriuria in elderly patients. British Journal of Clinical Practice 1991;45(4):245‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallichan 1994 {published data only}

- Gallichan MJ. Self‐monitoring by patients receiving oral hypoglycaemic agents: A survey and a comparative trial. Practical Diabetes 1994;11(1):28‐30. [EMBASE: 1994174437] [Google Scholar]

Goldby 2011 {published data only}

- Goldby S, Gray LJ, Khunti K, Williams S, Sheppard D, Taub N, et al. Using the Leicester practice risk score to identify people with Type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose regulation [abstract no: P331]. Diabetic Medicine 2011;28(Suppl 1):131. [EMBASE: 70631142] [Google Scholar]

Grimm 1997 {published data only}

- Grimm RH Jr, Svendsen KH, Kasiske B, Keane WF, Wahi MM. Proteinuria is a risk factor for mortality over 10 years of follow‐up, MRFIT Research Group. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Kidney International ‐ Supplement 1997;63:S10‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jolic 2011 {published data only}

- Jolic M, Lim YL, Hamblin S, Kinney S. A retrospective audit of screening practices used to detect abnormal glucose regulation in a cohort of AMI patients admitted to a coronary care unit ‐ An Australian study [abstract]. European Heart Journal 2011;32(Suppl 1):66‐7. [EMBASE: 70533291] [Google Scholar]

Jou 1998 {published data only}

- Jou WW, Powers RD. Utility of dipstick urinalysis as a guide to management of adults with suspected infection or hematuria. Southern Medical Journal 1998;91(3):266‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kazemier 2012 {published data only}

- Kazemier BM, Schneeberger C, Miranda E, Wassenaer A, Bossuyt PM, Vogelvang TE, et al. Costs and effects of screening and treating low risk women with a singleton pregnancy for asymptomatic bacteriuria, the ASB study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 2012;12:52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kenealy 2005 {published data only}

- Kenealy T, Arroll B, Petrie KJ. Patients and computers as reminders to screen for diabetes in family practice. Randomized‐controlled trial. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2005;20(10):916‐21. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Koschinsky 1984 {published data only}

- Koschinsky T, Toeller M, Berger H, Dannehl K, Dopstadt K, Yousefian M, et al. Improved metabolic state in insulin‐tested diabetes. Self‐testing of blood or urine glucose on 2 days per week [Bessere Stoffwechseleinstellung des insulinbehandelten Diabetes. Blut‐ oder Urin‐Glucose‐Selbstkontrolle an 2 Tagen pro Woche]. Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift 1984;109(5):174‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lauritzen 1994 {published data only}

- Lauritzen T, Christiansen JS, Brock A, Mogensen CE. Repeated screening for albumin‐creatinine ratio in an unselected population. The Ebeltoft Health Promotion Study, a randomized, population‐based intervention trial on health test and health conversations with general practitioners. Journal of Diabetes & its Complications 1994;8(3):146‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lauritzen 2008 {published data only}

- Lauritzen T, Jensen MS, Thomsen JL, Christensen B, Engberg M. Health tests and health consultations reduced cardiovascular risk without psychological strain, increased healthcare utilization or increased costs. An overview of the results from a 5‐year randomized trial in primary care. The Ebeltoft Health Promotion Project (EHPP). Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 2008;36(6):650‐61. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lenz 2002 {published data only}

- Lenz ER, Mundinger MO, Hopkins SC, Lin SX, Smolowitz JL. Diabetes care processes and outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians. Diabetes Educator 2002;28(4):590‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Little 2009 {published data only}

- Leydon GM, Turner S, Smith H, Little P, UTIS team. Women's views about management and cause of urinary tract infection: qualitative interview study. BMJ 2010;340:c279. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little P, Moore MV, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Lowes JA, et al. Effectiveness of five different approaches in management of urinary tract infection: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c199. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little P, Turner S, Rumsby K, Warner G, Moore M, Lowes JA, et al. Dipsticks and diagnostic algorithms in urinary tract infection: development and validation, randomised trial, economic analysis, observational cohort and qualitative study. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2009;13(19):1‐73. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner D, Little P, Raftery J, Turner S, Smith H, Rumsby K, et al. Cost effectiveness of management strategies for urinary tract infections: results from randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;340:c346. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McEwan 1990 {published data only}

- McEwan RT, Davison N, Forster DP, Pearson P, Stirling E. Screening elderly people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. British Journal of General Practice 1990;40(332):94‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGhee 1997 {published data only}

- McGhee M, O'Neill K, Major K, Twaddle S. Evaluation of a nurse‐led continence service in the south‐west of Glasgow, Scotland. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1997;26(4):723‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Messing 1995 {published data only}

- Messing EM, Young TB, Hunt VB, Gilchrist KW, Newton MA, Bram LL, et al. Comparison of bladder cancer outcome in men undergoing hematuria home screening versus those with standard clinical presentations. Urology 1995;45(3):387‐96. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Morris 2012 {published data only}

- Morris RK, Riley RD, Doug M, Deeks JJ, Kilby MD. Diagnostic accuracy of spot urinary protein and albumin to creatinine ratios for detection of significant proteinuria or adverse pregnancy outcome in patients with suspected pre‐eclampsia: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2012;345:e4342. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Naimark 2001 {published data only}

- Naimark DM, Bott MT, Tobe SW. Facilitating the adoption of microalbuminuria (MAU) screening among type II diabetic patients in primary care: preliminary results of a randomized educational intervention trial [abstract no: SU‐PO826]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2002;13(September, Program & abstracts):638A. [CENTRAL: CN‐00446889] [Google Scholar]

- Naimark DM, Bott MT, Tobe SW, Reznick RK, David D. Promotion of urine microalbuminuria screening among primary care physicians: a randomized, controlled, educational intervention trial [abstract]. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2001;12(Program & abstracts):231A. [CENTRAL: CN‐00446890] [Google Scholar]

Neumann 2008 {published data only}

- Neumann CG, Bwibo NO, Siekmann JH, McLean ED, Browdy B, Drorbaugh N. Comparison of blood smear microscopy to a rapid diagnostic test for in‐vitro testing for P. falciparum malaria in Kenyan school children. East African Medical Journal 2008;85(11):544‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nevedomskaya 2011 {published data only}

- Nevedomskaya E, Mayboroda OA, Deelder AM. Cross‐platform analysis of longitudinal data in metabolomics. Molecular Biosystems 2011;7(12):3214‐22. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ochoa 2007 {published data only}

- Ochoa Sangrador C, Conde Redondo F, Grupo Investigador del Proyecto. Utility of distinct urinalysis parameters in the diagnosis of urinary tract infections [Utilidad de los distintos parametros del perfil urinario en el diagnostico de infeccion urinaria]. Anales de Pediatria 2007;67(5):450‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reyburn 2007 {published data only}

- Reyburn H, Mbakilwa H, Mwangi R, Mwerinde O, Olomi R, Drakeley C, et al. Rapid diagnostic tests compared with malaria microscopy for guiding outpatient treatment of febrile illness in Tanzania: randomised trial. BMJ 2007;334(7590):403. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schwab 1992 {published data only}

- Schwab SJ, Dunn FL, Feinglos MN. Screening for microalbuminuria: A comparison of single sample methods of collection and techniques of albumin analysis. Diabetes Care 1992;15(11):1581‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simmons 2012 {published data only}

- Simmons RK, Echouffo‐Tcheugui JB, Sharp SJ, Sargeant LA, Williams KM, Prevost AT, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes and population mortality over 10 years (ADDITION‐Cambridge): a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9855):1741‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tissot 2001 {published data only}

- Tissot E, Woronoff‐Lemsi MC, Cornette C, Plesiat P, Jacquet M, Capellier G. Cost‐effectiveness of urinary dipsticks to screen asymptomatic catheter‐associated urinary infections in an intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine 2001;27(12):1842‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Worth 1982 {published data only}

- Worth R, Home PD, Johnston DG, Anderson J, Ashworth L, Burrin JM, et al. Intensive attention improves glycaemic control in insulin‐dependent diabetes without further advantage from home blood glucose monitoring: results of a controlled trial. BMJ 1982;285(6350):1233‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Avgerinos 2001

- Avgerinos DV, Björnsson J. Malignant neoplasms: discordance between clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings in 3,118 cases. APMIS 2001;109(11):774‐80. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bauer 2008

- Bauer C, Melamed ML, Hostetter TH. Staging of chronic kidney disease: time for a course correction. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2008;19(5):844‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Black 2010

- Black WC, Welch HG. Overdiagnosis in cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2010;102(9):605‐13. [EMBASE: 2010268614] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boland 1995

- Boland BJ, Wollan PC, Silverstein MD. Review of systems, physical examination, and routine tests for case‐finding in ambulatory patients. American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1995;309(4):194‐200. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boland 1996

- Boland BJ, Wollan PC, Silverstein MD. Yield of laboratory tests for case‐finding in the ambulatory general medical examination. American Journal of Medicine 1996;101(2):142‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulware 2003

- Boulware LE, Jaar BG, Tarver‐Carr ME, Brancati FL, Powe NR. Screening for proteinuria in US adults: a cost‐effectiveness analysis. JAMA 2003;290(23):3101‐14. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brown 2011

- Brown RS. Has the time come to include urine dipstick testing in screening asymptomatic young adults?. JAMA 2011;306(7):764‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chang 2011

- Chang A, Kramer H. Should eGFR and albuminuria be added to the Framingham risk score? Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease risk prediction. Nephron 2011;119(2):c171‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CKDPC 2010

- Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium, Matsushita K, Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta‐analysis. Lancet 2010;375(9731):2073‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clark 2011

- Clark WF, Macnab JJ, Sontrop JM, Jain AK, Moist L, Salvadori M, et al. Dipstick proteinuria as a screening strategy to identify rapid renal decline. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2011;22(9):1729‐36. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coresh 2007

- Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA 2007;298(17):2038‐47. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Djulbegovic 2010

- Djulbegovic M, Beyth RJ, Neuberger MM, Stoffs TL, Vieweg J, Djulbegovic B, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2010;341:c4543. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

EAU 2012

- Grabe M, Bjerklund‐Johansen TE, Botto H, Wullt B, Çek M, et al. Guidelines on urological infections. European Association of Urology. www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/17_Urological%20infections_LR%20II.pdf (accessed 10 December 2014).

Engberg 2002

- Engberg M, Christensen B, Karlsmose B, Lous J, Lauritzen T. General health screenings to improve cardiovascular risk profiles: a randomized controlled trial in general practice with 5‐year follow‐up. Journal of Family Practice 2002;51(6):546‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fink 2012

- Fink HA, Ishani A, Taylor BC, Greer NL, MacDonald R, Rossini D, et al. Screening for, monitoring, and treatment of chronic kidney disease stages 1 to 3: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force and for an American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Annals of Internal Medicine 2012;156(8):570‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Friedman 1986

- Friedman GD, Collen MF, Fireman BH. Multiphasic Health Checkup Evaluation: a 16‐year follow‐up. Journal of Chronic Diseases 1986;39(6):453‐63. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Furtado 2005

- Furtado CD, Aguirre DA, Sirlin CB, Dang D, Stamato SK, Lee P, et al. Whole‐body CT screening: spectrum of findings and recommendations in 1192 patients. Radiology 2005;237(2):385‐94. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grønhøj Larsen 2010

- Grønhøj Larsen C. Staying healthy or getting sick? Presentation on websites of benefits and harms from health checks by providers: cross sectional study. Data on file 2010.

Gøtzsche 2013

- Gøtzsche PC, Jørgensen KJ. Screening for breast cancer with mammography. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 6. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001877.pub5] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hemmelgarn 2006

- Hemmelgarn BR, Zhang J, Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Larsen E, Ghali WA, et al. Progression of kidney dysfunction in the community‐dwelling elderly. Kidney International 2006;69(12):2155‐61. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hemmelgarn 2010

- Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Lloyd A, James MT, Klarenbach S, Quinn RR, et al. Relation between kidney function, proteinuria, and adverse outcomes. JAMA 2010;303(5):423‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2003

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327(7414):557‐60. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011

- Higgins JP, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Hillege 2001

- Hillege HL, Janssen WM, Bak AA, Diercks GF, Grobbee DE, Crijns HJ, et al. Microalbuminuria is common, also in a nondiabetic, nonhypertensive population, and an independent indicator of cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular morbidity. Journal of Internal Medicine 2001;249(6):519‐26. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hogg 2009

- Hogg RJ. Screening for CKD in children: a global controversy. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2009;4(2):509‐15. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Holme 2013

- Holme Ø, Bretthauer M, Fretheim A, Odgaard‐Jensen J, Hoff G. Flexible sigmoidoscopy versus faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer screening in asymptomatic individuals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 9. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009259.pub2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Imai 2007

- Imai E, Yamagata K, Iseki K, Iso H, Horio M, Mkino H, et al. Kidney disease screening program in Japan: history, outcome, and perspectives. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN 2007;2(6):1360‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Independent UK Panel 2012

- Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening. The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet 2012;380(9855):1778‐86. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Iseki 2003

- Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Iseki C, Takishita S. Proteinuria and the risk of developing end‐stage renal disease. Kidney International 2003;63(4):1468‐74. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ito 1990

- Ito K, Kawaguchi H, Hattori M. Screening for proteinuria and hematuria in school children‐‐is it possible to reduce the incidence of chronic renal failure in children and adolescents?. Acta Paediatrica Japonica 1990;32(6):710‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

James 2010

- James MT, Hemmelgarn BR, Wiebe N, Pannu N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, et al. Glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria, and the incidence and consequences of acute kidney injury: a cohort study. Lancet 2010;376(9758):2096‐103. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jørgensen 2009

- Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. Overdiagnosis in publicly organised mammography screening programmes: systematic review of incidence trends. BMJ 2009;339:b2587. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Karwinski 1990

- Karwinski B, Svendsen E, Hartveit F. Clinically undiagnosed malignant tumours found at autopsy. APMIS 1990;98(6):496‐500. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kroenke 1986

- Kroenke K, Hanley JF, Copley JB, Matthews JI, Davis CE, Foulks CJ, et at. The admission urinalysis: impact on patient care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1986;1(4):238‐42. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krogsbøll 2012a

- Krogsbøll LT, Jørgensen KJ, Grønhøj Larsen C, Gøtzsche PC. General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009009.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Krogsbøll 2014

- Krogsbøll LT. Guidelines for screening with urinary dipsticks differ substantially ‐ a systematic review. Danish Medical Journal 2014;61(2):A4781. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lannerstad 1977

- Lannerstad O, Sternby NH, Isacsson SO, Lindgren G, Lindell SE. Effects of a health screening on mortality and causes of death in middle‐aged men. A prospective study from 1970 to 1974 of mean in Malmo, born 1914. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine 1977;5(3):137‐40. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lin 2008

- Lin K, Fajardo K, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2008;149(1):W20‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Malmström 2003

- Malmström PU. Time to abandon testing for microscopic haematuria in adults?. BMJ 2003;326(7393):813‐5. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Matsushita 2010

- Chronic Kidney Disease Prognosis Consortium, Matsushita K, Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all‐cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta‐analysis. Lancet 2010;375(9731):2073‐81. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McGrogan 2011

- McGrogan A, Franssen CF, Vries CS. The incidence of primary glomerulonephritis worldwide: a systematic review of the literature. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2011;26(2):414‐30. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Merenstein 2006

- Merenstein D, Daumit GL, Powe NR. Use and costs of nonrecommended tests during routine preventive health exams. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2006;30(6):521‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Messing 2006

- Messing EM, Madeb R, Young T, Gilchrist KW, Bram L, Greenberg EB, et al. Long‐term outcome of hematuria home screening for bladder cancer in men. Cancer 2006;107(9):2173‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moynihan 2013

- Moynihan R, Glassock R, Doust J. Chronic kidney disease controversy: how expanding definitions are unnecessarily labelling many people as diseased. BMJ 2013;347:f4298. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

NICE 2008a

- National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence. Antenatal care. Routine care for the healthy pregnant woman. NICE Clinical Guideline 62. 2008. www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG062NICEguideline.pdf (accessed 10 December 2014).

NICE 2008b

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Chronic Kidney Disease: early identification and management of chronic kidney disease in adults in primary and secondary care. NICE guidelines [CG72]. 2008. www.nice.org.uk/CG73 (accessed 10 December 2014).

NKF 2002

- National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1‐266. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olsen 1976

- Olsen DM, Kane RL, Proctor PH. A controlled trial of multiphasic screening. New England Journal of Medicine 1976;294(17):925‐30. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prochazka 2005

- Prochazka AV, Lundahl K, Pearson W, Oboler SK, Anderson RJ. Support of evidence‐based guidelines for the annual physical examination: a survey of primary care providers. Arch Intern Med 2005;165(12):1347‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Raffle 2003

- Raffle AE, Alden B, Quinn M, Babb PJ, Brett MT. Outcomes of screening to prevent cancer: analysis of cumulative incidence of cervical abnormality and modelling of cases and deaths prevented. BMJ 2003;326(7395):901. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reid 2011

- Reid S, Cawthon PM, Craig JC, Samuels JA, Molony DA, Strippoli GF. Non‐immunosuppressive treatment for IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003962.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rüttimann 1994

- Rüttimann S, Clémençon D. Usefulness of routine urine analysis in medical outpatients. Journal of Medical Screening 1994;1(2):84‐7. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Samuels 2003

- Samuels JA, Strippoli GF, Craig JC, Schena FP, Molony DA. Immunosuppressive agents for treating IgA nephropathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2003, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003965] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schilling 2002

- Schilling FH, Spix C, Berthold F, Erttmann R, Fehse N, Hero B, et al. Neuroblastoma screening at one year of age. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(14):1047‐53. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sharma 2011

- Sharma P, Blackburn RC, Parke CL, McCullough K, Marks A, Black C, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers for adults with early (stage 1 to 3) non‐diabetic chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011, Issue 10. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007751.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Simmons 2012a

- Simmons RK, Echouffo‐Tcheugui JB, Sharp SJ, Sargeant LA, Williams KM, Prevost AT, et al. Screening for type 2 diabetes and population mortality over 10 years (ADDITION‐Cambridge): a cluster‐randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012;380(9855):1741‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Takebayashi 1992

- Takebayashi S, Yanase K. Asymptomatic urinary abnormalities found via the Japanese school screening program: a clinical, morphological and prognostic analysis. Nephron 1992;61(1):82‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Thomason 1998

- Thomason MJ, Lord J, Bain MD, Chalmers RA, Littlejohns P, Addison GM, et al. A systematic review of evidence for the appropriateness of neonatal screening programmes for inborn errors of metabolism. Journal of Public Health Medicine 1998;20(3):331‐43. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Tibblin 1982

- Tibblin G, Welin L, Larsson B, Ljungberg IL, Svärdsudd K. The influence of repeated health examinations on mortality in a prospective cohort study, with a comment on the autopsy frequency. The study of men born in 1913. Scandinavian Journal of Social Medicine 1982;10(1):27‐32. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vivante 2011

- Vivante A, Afek A, Frenkel‐Nir Y, Tsur D, Farfel A, Golan A, et al. Persistent asymptomatic isolated microscopic hematuria in Israeli adolescents and young adults and risk for end‐stage renal disease. JAMA 2011;306(7):729‐36. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wakai 2004

- Wakai K, Nakai S, Kikuchi K, Iseki K, Miwa N, Masakane I, et al. Trends in incidence of end‐stage renal disease in Japan, 1983‐2000: age‐adjusted and age‐specific rates by gender and cause. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2004;19(8):2044‐52. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Welch 2004

- Welch HG. Should I be tested for cancer? Maybe not and here's why. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

Welch 2010

- Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2010;102(9):605‐13. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Welch 2011

- Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed ‐ making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston: Beacon Press, 2011. [ ISBN: 978‐080702200‐9] [Google Scholar]

Woods 2002

- Woods WG, Gao RN, Shuster JJ, Robison LL, Bernstein M, Weitzman S, et al. Screening of infants and mortality due to neuroblastoma. New England Journal of Medicine 2002;346(14):1041‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Xiong 2005

- Xiong T, Richardson M, Woodroffe R, Halligan S, Morton D, Lilford RJ. Incidental lesions found on CT colonography: their nature and frequency. British Journal of Radiology 2005;78(925):22‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Krogsbøll 2012b

- Krogsbøll LT, Jørgensen KJ, Gøtzsche PC. Screening with urinary dipsticks for reducing morbidity and mortality. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012, Issue 8. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010007] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]