Abstract

Neurodegenerative complexities, such as dementia, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and so forth, have been a crucial health concern for ages. Transferrin (Tf) is a chief target to explore in AD management. Fluoxetine (FXT) presents itself as a potent anti-AD drug-like compound and has been explored against several diseases based on the drug repurposing readings. The present study delineates the binding of FXT to Tf employing structure-based docking, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, and principal component analysis (PCA). Docking results showed the binding of FXT with Tf with an appreciable binding affinity, making various close interactions. MD simulation of FXT with Tf for 100 ns suggested their stable binding without any significant structural alteration. Furthermore, fluorescence-based binding revealed a significant interaction between FXT and Tf. FXT binds to Tf with a binding constant of 5.5 × 105 M–1. Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) advocated the binding of FXT to Tf as spontaneous in nature, affirming earlier observations. This work indicated plausible interactions between FXT and Tf, which are worth considering for further studies in the clinical management of neurological disorders, including AD.

1. Introduction

The most common yet least noteworthy psychiatric disorders are depression and anxiety. Depression affects millions of individuals globally.1 The condition has a few significant hallmarks: bad mood, anxious behavior, and inability to concentrate.2 The other primary psychiatric conditions associated with depression can be obsessive-compulsive disorder and suicidal behavior. The conditions are attributed to the under-function of serotonergic mechanisms.3 The symptoms many times indicate comorbid conditions of disorders as well. The most frequently prescribed drugs for antidepressant therapy and obsessive-compulsive disorder are the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that block serotonin transporters’ (SERTs’) function. SERT inhibition in the short term increases levels of serotonin in the brain.4 A continued 3–6 week therapy with SSRIs is suggested to alleviate the symptoms of low serotonin-associated disorders.

One of the most commonly used antidepressants and SSRIs is fluoxetine (FXT). FXT is a well-known diphenhydramine derivative with antiobsessional, antidepressant, and antianxiety activities. Figure S1 shows the structure of FXT. Upon administration, like other SSRIs, FXT binds to the presynaptic SERT, negatively modulating the complex and inhibiting serotonin recycling. Serotonin reuptake inhibition by the drug further boosts the serotonergic function by accumulating serotonin in the synaptic space. Additionally, FXT inhibits proinflammatory cytokine expression for IL-6, which prevents inflammation and cytokine release. FXT along with olanzapine is used to treat depression linked to bipolar I disorder. FXT after oral intake is well absorbed, but it is affected extensively during liver metabolism. FXT, by demethylation, is converted into its active metabolite norFXT with the aid of cytochrome P450 enzymes.5,6 The active norFXT is eliminated majorly through oxidative metabolism and excreted through urine.7 The half-life of the drug FXT is estimated to be 1–4 days, while norFXT has a half-life of 7–15 days.8 In the past few decades, FXT has been studied extensively for its effects on other cellular processes.9 Importantly, FXT and other SSRIs show activities and interactions with other cellular processes. It has been proven as an effective candidate to treat other neurological conditions as well.

Recent studies related to clinical Alzheimer’s disease (AD) types followed by depression have shown that FXT administration enhances the cognitive abilities of AD patients.10 FXT has a positive effect on cognitive enhancement in AD mice at early stages.11 However, the protective effect on AD reversal by FXT is still not completely clear. Various interactions of FXT with other proteins in the brain may have a prominent role in curbing the menace resultant from AD.12 One of the major factors playing a significant role in AD progression is iron dyshomeostasis. Free iron acts as a potent neurotoxin due to its contribution to redox reactions. Disrupted homeostasis, that is, iron loss and depositions, can contribute to many neurological conditions. The major reason could be its direct and indirect interactions with other cellular components.13 The labile pool of intracellular iron is well known to alter the expression of many proteins through interactions with the amyloid precursor protein.14 Deposition of transition metals is known to create havoc in the nervous system by assisting neurodegenerative disorder progression.15 Iron deposition and accumulation have been associated with neurodegenerative and neuroferrinopathies as well. Transferrin (Tf) family is a class of iron transporter proteins working across the blood to fulfill the purpose. Human Tf, a glycoprotein that weighs 79.6 kDa, plays a significant role in the progression of neuropathology related to iron dyshomeostasis.16

Tf fulfills its role as a Fe transporter in the endosomal compartments of the cells by associating in a complex of iron, transferrin, and transferrin receptor.17 In low pH conditions, iron is dissociated from the complex and relocated by associated transporters to the cytoplasm. Iron, after dissociation, produces Aβ oligomers and increased toxicity is observed, which is further involved in generating reactive oxygen species. Iron is grabbed and held by Tf, which reduces Aβ toxicity. Tf plays a dual role: first, by sequestering iron, it halts Aβ formation, and second, by discharging free iron, it aids in Aβ formation and thus AD progression.

Many studies have investigated the mechanism of interaction of ligands with important proteins using computational and spectroscopic approaches.18 FXT was taken as a plausible partner for binding to Tf; this study targeted to perform structure-based docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies for 100 nanoseconds, followed by principal component analysis (PCA) and free energy landscape (FEL) analysis. Fluorescence-based binding and isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) ascertained the real affinity between FXT and Tf. The importance of the study stems from the fact that Tf plays a vital role in AD and FXT is a key player in the treatment of neurological conditions. Overall, this study showed plausible interactions between FXT and Tf, which are worth considering for further studies in the clinical management of neurological disorders, including AD.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Docking of FXT and Tf

FXT was docked to Tf with a binding affinity of −7.2 kcal/mol with a predicted pKi value of 5.28 and a ligand efficiency (LE) of 0.327 kcal/mol/non-H atom. We have also calculated the docking energy of the FXT and Tf complex after performing redocking for up to five different runs of InstaDock with independent random seeds and found good consistency in the resultant output (Table S1). FXT forms one conventional hydrogen bond (H-bond) interacting with Gly444, along with one C–H bond with Glu442 and several hydrophobic interactions (Figure 1A,B). These interactions are in close proximity of a metal-binding site in Tf, which is responsible for binding with Fe3+.19 The FXT interaction shows a considerable LE value, that is, >30. As apparent from the docking result illustrated in the figure, FXT binds inside the binding pocket cavity of Tf (Figure 1C). It was evident that FXT had an appreciable binding affinity and LE value, thus intimating its potential to be a decent binding partner of Tf.

Figure 1.

Molecular interaction of FXT with Tf. (A) Ribbon diagram of Tf with FXT. (B) Zoomed ribbon diagram of Tf displaying interactions with FXT. (C) Interpolated charge surface of the binding cavity of Tf occupied by FXT.

The most stable conformational state of FXT with Tf predicted through the docking study was the first one with the highest binding affinity score. This first docked conformation of FXT was explored with Tf in detail to know all possible interactions and their types. The docked complex with the selected docking pose was stabilized by various interactions, including H-bonding with Gly444 and Glu442. Apart from H-bonding, FXT was also engaged in forming alkyl, π–alkyl, and π–π interactions with Phe446 and Ala594 (Figure 2A). Additionally, it showed four hydrophobic interactions with Tyr431, Asn432, Ly433, Tyr445, His554, Gln555, Tyr493, and Arg600 of Tf. Tyr445 is one of the sites which is responsible for the iron binding in Tf. It is evident from the figure that FXT was in close contact with Tyr445 of Tf and shared a hydrophobic interaction (Figure 2A). It was revealed from the study that FXT occupied a deep binding pocket of Tf appropriately (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Molecular interactions of FXT with Tf depicted as a (A) 2D plot and (B) 3D binding pocket.

2.2. MD Simulations

Based on the docking study, we took the first confirmation of FXT for further evaluation through MD simulation studies. It helped us to get to a plausible model of FXT binding with Tf under solvent conditions. The time evolutions of MD plots of Tf in the native form and the complex form with FXT for 100 ns MD simulations are depicted in Figures 3–6. The graphs show a similar trend of MD trajectories of the native system and the protein–ligand complex system. Hence, it is evident that FXT has a decent binding potential for Tf. For the evaluation of the stability of both the systems, various parameters were evaluated from the simulated trajectories, namely, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), solvent-accessible surface area (SASA), radius of gyration (Rg), and intra- and intermolecular H-bonding in the protein (alone) and the complex formed by the protein–ligand interaction.

Figure 3.

Conformational dynamics of Tf and the Tf–FXT complex. (A) RMSD of free Tf and the Tf–FXT complex. (B) Time evolution of the RMSD values. (C) RMSF graph depicting the deviation in the residual movement of Tf. (D) Time evolution of RMSF values.

Figure 6.

Intermolecular hydrogen bonds between FXT and Tf during the simulation time. (A) Time evolution of hydrogen bonds formed between FXT and Tf. (B) Probability of distribution of hydrogen bonds.

The RMSD of Tf in the native and complex state during the 100 ns MD simulation was traced and plotted to validate the structural stability of the protein.20 An examination of the time-evolution graphs shows that the Tf–FXT complex has higher structural stability than the free state of Tf (Figure 3). It was remarkable to note that the structural deviation in Tf–FXT resists expanding, especially after 30 ns of simulation. The plot showed that the RMSD of both systems was equilibrated throughout the simulation of 100 ns. The graph showed that the RMSD pattern was reduced after FXT binding in comparison to the RMSD pattern of the native Tf. The plot showed the RMSD of Tf on the y-axis, while the x-axis showed the time evolution of the simulation trajectory. The average RMSD value when the free Tf and Tf–FXT complex reached equilibrium was ∼0.05 nm. In the ligand-bound state of the protein’s RMSD, a minor fluctuation was observed between 70 and 80 ns of the trajectory. However, the variations were distributed up to 0.15 Å in such a way that it was evident that the protein had not undergone any significant conformational changes. Overall, the result indicated that the Tf–FXT complex is steady throughout the simulation and does not seem to have fluctuated pointedly (Figure 3A). The probability distribution plot of RMSD also noticeably shows that the structure of Tf was stabilized even after FXT binding (Figure 3B).

RMSF analysis helps us explore the average fluctuation exhibited by each residue in a protein. It can be explored while studying the influence of ligand binding on the protein during the simulation time.21 The RMSF of each residue in Tf was plotted and evaluated compared to the free and ligand-bound state of the protein (Figure 3C). The RMSF plot showed that the average fluctuation of the residues in the protein Tf was minimized after the FXT binding, excluding some minor elevated peaks in the residual fluctuation. The amino acid residues between 270 and 380 have played a crucial role due to their participation in ligand binding. It is evident from the graph that FXT does not induce any significant changes in that region’s RMSF values. However, the plot also showed that the residual fluctuation of the binding pocket is slightly increased after FXT binding during the simulation. The density distribution plot clearly showed that Tf’s overall fluctuations are minimized after FXT binding (Figure 3D).

To further evaluate the compactness of the Tf protein in the native state and in its ligand-bound state with FXT, the Rg of both the systems was calculated and plotted from the trajectory (Figure 4A). The average Rg values for Tf and the Tf–FXT complex were estimated to be 2.89 and 2.90 nm, respectively. A slight increase in the average values of Rg indicated that the Tf structure had some minor loose packing owing to the occupancy of intramolecular space by FXT. However, this minor increase does not seem to induce any large conformational changes in the structure during the simulation. Overall, the plot suggested that the Tf–FXT complex was legitimately stable, maintained throughout the simulation time. The density distribution plot also indicated that Tf and the Tf–FXT complex do not show any major deviations (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Structural compactness of Tf and the Tf–FXT complex during the simulation time. (A) Rg plotted during the 100 ns MD run of Tf (black) and FXT-bound Tf (green). (B) Time evolution of Rg during the simulation. (C) SASA plotted during the 100 nm MD run Tf (black) and FXT-bound Tf (green). (D) Time evolution of the SASA during the simulation.

Exploring the change in solvent accessibility has been useful to evaluate the folding dynamics during the simulation.22 It was assessed as SASA of the Tf protein during the simulation, which helped us investigate the effect of FXT binding on the solvent accessibility of Tf. The time evolution of SASA was evaluated and plotted from the simulated trajectory (Figure 4C). It was cleared from the plot that Tf’s SASA has a minor increase after the FXT binding due to the exposure of some buried residues. However, this minor increase does not seem to change the protein folding during the simulation significantly. As a whole, the SASA distribution showed a rational equilibration throughout the simulation trajectory, without any significant changes. The density distribution plot also indicated that the SASA of the Tf–FXT complex increased somehow but on a minor scale, which further suggested the stability of the protein (Figure 4D).

2.2.1. Dynamics of Intra-/Intermolecular H-Bonds

The study of H-bonding in free proteins and protein–ligand complexes is useful to get insights into their structural stability and integrity.23 The intramolecular H-bonds formed within Tf were calculated and plotted before and after FXT binding (Figure 5A). The results showed that the H-bonds within the Tf protein retain their consistency throughout the simulation with and without FXT. The study suggested that H-bonds in Tf are unwavering, which maintained the geometry of the structure of Tf; FXT did not mess up the intramolecular H-bonds in Tf. The density distribution plot also suggested a slight decrease in H-bonds within Tf with FXT, which meant they used some intramolecular space within the Tf binding pocket (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Intramolecular H-bonding within the structure of the Tf protein during the simulation. (A) Intramolecular H-bonds plotted for Tf (black) and the Tf–FXT complex (green). (B) Probability of distribution of H-bonding during the 100 ns MD run as PDF.

H-bonds between the protein and ligand provide directionality and stability in the protein–ligand complex.24 H-bonds formed between FXT and Tf were examined with time evolution during the simulation (Figure 6A). The plot showed that FXT formed up to three H-bonds with Tf but with fewer fluctuations at several times. The analysis suggested that one H-bond was maintained in the Tf–FXT complex throughout the simulation, which was also shown in the initial complex taken from the molecular docking study. Overall, the analysis showed that the Tf–FXT complex is stable throughout the simulation. The density distribution plot also showed that one H-bond was formed with the highest distribution, responsible for maintaining the complex integrity (Figure 6B).

2.3. Principal Component Analysis

PCA was performed using the first two eigenvectors (EVs) for investigating the impact of FXT binding on the collective motions in Tf (Figure 7A). The scatter plot generated by the native Tf and Tf–FXT complex is shown in Figure 7B. The figure indicated no significant difference between the conformational projections of Tf and the Tf–FXT complex. It was observed that the projection of the protein–ligand complex shrunk on both the EVs during the simulation compared with that of the native protein. The Tf–FXT system explored a reduced phase space compared to that of the native Tf. Overall, as shown in the plot, the conformational motions in both systems were not varied, suggesting complex stability.

Figure 7.

PCA. (A) Time evaluation of conformational projections on EV1 and EV2. (B) 2D projection plot showing the conformation sampling of Tf on EV1 and EV2.

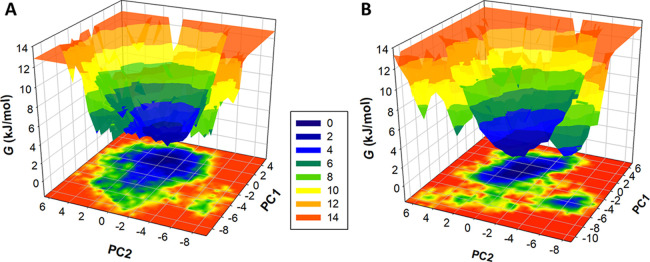

2.4. FEL Analysis

The FEL analysis helps investigate a protein’s folding mechanism and structural stability.25 This study performed FEL analysis for all Cα atoms in Tf before and after the FXT binding. The contour maps shown in Figure 8 indicated deeper blue toward lower energy based on the protein stability. The deep blue spot showed the lowest energy with the most stable conformational state toward the global minima of the protein structure. The y-axis of the plot showed the energy scale with varying values, ranging from 0 to 14 kJ/mol, for the entire course of the Tf folding. The analysis indicated that Tf and the Tf–FXT complex have a single global minimum restricted to a local basin. Overall, the FEL study advocated that no significant conformation and stability changes occurred in the simulation due to the FXT binding (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

FEL plots for (A) free Tf and (B) the Tf–FXT complex.

2.5. MMPBSA Binding Free Energy

The binding free energy of FXT to Tf was calculated using the molecular mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann surface area (MMPBSA) approach. The MD trajectories of a 10 ns stable region, that is, between 50 and 60 ns, were fetched to generate the binding affinity of the complex. FXT shows an appreciable binding affinity with Tf, that is, −108.51 ±14.78 kJ/mol. The MMPBSA result confirmed that FXT binds to Tf with a decent binding affinity and results in a stable complex formation.

2.6. Fluorescence-based Binding

Fluorescence binding studies reveal the real binding affinity of ligand with the protein.26 This method is usually deployed if the receptor and ligand do not have natural fluorescence absorption peaks.27 Fluorescence quenching is a process where a decrease in the fluorescence intensity of the protein is apparent with increasing ligand concentrations. Figure 9A shows fluorescence quenching of Tf with increasing concentrations of FXT (0–0.7 μM). It is apparent that the fluorescence intensity of Tf decreased with increasing FXT concentrations, thus suggesting the complex formation.28 We used the modified Stern–Volmer equation to find the binding parameters of the Tf–FXT complex as per previous studies.29 FXT binds to Tf with an appreciable binding affinity; the binding constant (K) for the Tf–FXT interaction was 5.5 × 105 M–1. The results obtained from the fluorescence assay corroborate in silico observations advocating that FXT binds to Tf with a good affinity.

Figure 9.

(A) Fluorescence emission spectra of Tf (4 μM) in the presence of varying FXT concentrations (0–0.7 μM). (B) Modified Stern–Volmer plot of the Tf–FXT complex.

2.7. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

ITC is performed to gain a deeper insight into the binding of protein with a ligand. Herein, we have performed ITC to authenticate fluorescence-based binding and in silico observations. Figure 10 depicts ITC isotherm obtained upon titration of 200 μM FXT into 25 μM Tf. It is evident from the obtained isotherm that FXT binds to Tf spontaneously affirming the earlier observations. The binding parameters obtained from ITC for the Tf–FXT interaction are listed in Table 1. The data were plotted as a two-site model. The obtained binding parameters are comparable to those obtained from fluorescence spectroscopy, further validating the strong binding of FXT to Tf. Thus, our ITC observations together with in silico and fluorescence binding confirmed the strong binding of FXT to Tf.

Figure 10.

ITC isotherm of titration of FXT into Tf. The sample cell was filled with Tf, while the syringe was filled with FXT.

Table 1. Thermodynamic Parameters for the Tf–FXT Interaction Obtained from ITC.

| Ka (association constant) M–1 | ΔH (enthalpy change) cal/mol | ΔS (cal/mol/deg) |

|---|---|---|

| Ka1 = 1.45 × 105 ± 1.8 × 104 | ΔH1 = 3117 ± 361 | ΔS1 = 34.1 |

| Ka2= 7.66 × 104 ± 9.1 × 103 | ΔH2 = −1.68 × 104 ± 918 | ΔS2 = −34.1 |

3. Conclusions

The molecular interaction of Tf with different entities, including small molecules such as FXT, can be explored for disease management. This study revealed the binding of a potent AD drug, FXT, to Tf, a protein that is a critical player in AD management. The possible interactions of Tf with FXT were explored in detail, and it was found that FXT has a great potential to interact with Tf. The molecular docking study suggested that FXT interacts with Tf with various contacts, including H-bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Furthermore, the simulation study indicated that the Tf–FXT complex is relatively stable throughout the simulation trajectory. Additionally, in silico analyses were validated by in vitro binding studies, viz., fluorescence spectroscopy and ITC. Fluorescence binding suggested that FXT binds to Tf with a significant affinity. ITC was also employed to have thermodynamic insight into the binding of FXT to Tf, and the obtained isotherm was suggestive of sponatneous binding of FXT with Tf. Overall, the results conclude that FXT acts as a potential binding partner of Tf, which can be implicated in the clinical management of Tf-associated complexities. The significance of the work is due to the fact that Tf plays a crucial role in AD and is being increasingly explored.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

FXT and Tf were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. The protein was dialyzed before use to remove the excessive salts, and the purity was checked using gel electrophoresis. All the buffers were made up in double distilled water. All the other chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade.

4.2. Protein Receptor and Ligand Preparation

The three-dimensional structure of Tf [PDB ID: 3V83] was retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) at the resolution of 2.10 Å.19a Water molecules were deleted, and missing H-atoms to the polar groups of the protein were added in the PyMOL.30 For structure preprocessing, the Swiss-PDB Viewer program31 was used to clean and supply any missing atoms. The energy minimization of the protein receptor under vacuum conditions was also performed through the Swiss-PDB Viewer, which has a GROMOS force field option.32 The refined structure of the protein receptor was saved separately for further study. The FXT structure was taken from the PubChem database (PubChem CID: 3386). The energy minimization of the ligand structure was performed through the ChemDraw suite, which has the CHARMM force field option.33 The receptor protein and ligand structures were prepared using the “Prepare Receptor” and “Prepare Ligand” modules of InstaDock software.34

4.3. Molecular Docking

The prepared protein receptor and ligand structures were imported into InstaDock software to proceed with the docking study under a blind search space. The grid parameters were positioned around the receptor protein to confine the whole protein within the three-dimensional grid box. The docking was performed by the default setting of the InstaDock program.34 AutoDock Vina’s default scoring function calculates the docking score as binding affinity (ΔG) in InstaDock. After the docking process, all possible docked conformers of FXT were split through the “Ligand splitter” tool embedded in InstaDock. The specific interaction analysis made the final docking pose selection. The detailed interactions between the protein and ligand were explored using PyMOL and Discovery Studio Visualizer.35 pKi and LE for the ligand were also estimated based on the protocol published in our previous reports.34,36

4.4. MD Simulations

The latest version of GROMACS, that is, 2020 beta,37 was employed to conduct MD simulations in accordance with the standard protocol. The structural coordinates for two systems, viz, Tf and the Tf–FXT docked complex, were prepared from the docking result. The GROMACS parameters for FXT were prepared from the PRODRG server.38 The extended simple point charge water model with GROMOS 54A7 force field was utilized on both systems. Both systems were minimized for 1500 steps in the steepest descent process. For electrical neutralization, an appropriate number of counterions were added to the solvated systems, followed by an energy minimization for 50,000 steps. The equilibration process, that is, NVT and NPT, were performed for 1 ns. The final simulations were performed at 300 K for a brief period of 100 ns in periodic boundary settings in the solvent virtual box at a distance of 10 Å. Post-dynamic analyses, such as RMSD, RMSF, Rg, SASA, and H-bond evaluation, were performed using the established protocols.26a,36,39

4.5. Principal Component Analysis

PCA is a helpful approach to reveal the essential motions in protein.40 PCA tools are embedded in the GROMACS package to analyze protein trajectories in a time-evolution manner. In this study, PCA was performed to reveal the conformational projection of Tf and Tf–FXT complex using the Cα atoms. PCA can be calculated based on the covariance matrix described as follows41

where xi/xj signifies the Cartesian coordinate of the ith/jth atom and <−> signifies the ensemble average.

4.6. FEL Analysis

FEL analysis is useful to define the aging of the protein folding mechanism.41 The FELs of a protein structure can provide a quantitative description of folding dynamics under stress conditions.42 In this study, FELs were generated and evaluated for Tf and the Tf–FXT complex from the simulated trajectories. The FELs of both the systems were generated by the gmx sham utility of GROMACS while utilizing the following formula

where KB signifies the Boltzmann constant; T signifies the temperature, that is, 300 K; and P(X) signifies the probability distribution.

4.7. MMPBSA Binding Free Energy Calculation

The MMPBSA approach was also used to estimate the binding free energy of the interactions between the Tf and FXT complex. The MMPBSA was determined using the g_mmpbsa tool embedded in GROMACS.43 The trajectories for every 10 ps from a stable region, that is, between 50 and 60 ns, were collected to estimate the binding energy.

4.8. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

We performed fluorescence-based binding assay to ascertain the binding as per previously published reports.44 The protein was excited at 280 nm with the emission recorded in the range of 300–400 nm. The excitation and emission slit widths were set at 10 nm with a medium response. K was calculated as per the modified Stern–Volmer equation

4.9. Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

The ITC experiment was performed on the VP-ITC microcalorimeter from MicroCal, Inc (GE, MicroCal, USA) as per previous reports.28,45 Tf was dialyzed before loading, followed by degassing for a sufficient amount of time to avoid the impact of bubbles on the experiment. A first false injection of 5 μL followed an automated titration (successive injections of 10 μL FXT solution into the sample cell containing 20 μM Tf). The final figure was obtained using two model sites using MicroCal 8.0.

Acknowledgments

M.S.K. acknowledges the generous support from the Research Supporting Project (RSP-2021/352) of the King Saud University, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00182.

2-D structure of FXT, 3-D structure of FXT, and binding affinities of FXT with Tf in five different runs of InstaDock with independent random seeds (PDF)

Author Contributions

M.S.K. completed the conceptualization; formal analysis; project administration; writing; and writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. M.S. completed the visualization; software; and writing, review, and editing of the manuscript. A.S. completed data validation and data analysis. F.A. completed editing and data curation. S.A.A. completed the methodology and conducted the investigation. B.A. completed visualization, software, and data validation. W.A. completed data validation and software. D.K.Y. completed data curation; supervision; and writing, review, and editing of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper was published ASAP on March 2, 2022, with an duplicate phrase in the article title introduced during production. The corrected version was posted March 3, 2022.

Supplementary Material

References

- Smith K. Mental health: a world of depression. Nature 2014, 515, 180. 10.1038/515180a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a American Psychiatric Association, A . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, 1980; Vol. 3. [Google Scholar]; b Perahia D. G. S.; Quail D.; Desaiah D.; Montejo A. L.; Schatzberg A. F. Switching to duloxetine in selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor non- and partial-responders: Effects on painful physical symptoms of depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2009, 43, 512–518. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Willner P.; Scheel-Krüger J.; Belzung C. The neurobiology of depression and antidepressant action. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 37, 2331–2371. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bespalov A. Y.; van Gaalen M. M.; Gross G. Antidepressant treatment in anxiety disorders. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010, 2, 361–390. 10.1007/7854_2009_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jacobsen J. P. R.; Medvedev I. O.; Caron M. G. The 5-HT deficiency theory of depression: perspectives from a naturalistic 5-HT deficiency model, the tryptophan hydroxylase 2 Arg 439 His knockin mouse. Philos. Trans. R. Soc., B 2012, 367, 2444–2459. 10.1098/rstb.2012.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blier P.; de Montigny C. Possible serotonergic mechanisms underlying the antidepressant and anti-obsessive-compulsive disorder responses. Biol. Psychiatr. 1998, 44, 313–323. 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00114-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis J. M.; O’Donnell J. P.; Mankowski D. C.; Ekins S.; Obach R. S. (R)-, (S)-, and racemic fluoxetine N-demethylation by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2000, 28, 1187–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ring B. J.; Eckstein J. A.; Gillespie J. S.; Binkley S. N.; VandenBranden M.; Wrighton S. A. Identification of the human cytochromes p450 responsible for in vitro formation of R- and S-norfluoxetine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2001, 297, 1044–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood A. J. J.; Gram L. F. Fluoxetine. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 331, 1354–1361. 10.1056/nejm199411173312008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Altamura A. C.; Moro A. R.; Percudani M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluoxetine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1994, 26, 201–214. 10.2165/00003088-199426030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hankey G. J.; Hackett M. L.; Almeida O. P.; Flicker L.; Mead G. E.; Dennis M. S.; Etherton-Beer C.; Ford A. H.; Billot L.; Jan S. Safety and efficacy of fluoxetine on functional outcome after acute stroke (AFFINITY): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 661. 10.1016/s1474-4422(20)30219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Terstappen G. C.; Pellacani A.; Aldegheri L.; Graziani F.; Carignani C.; Pula G.; Virginio C. The antidepressant fluoxetine blocks the human small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels SK1, SK2 and SK3. Neurosci. Lett. 2003, 346, 85–8. 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00574-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Traboulsie A.; Chemin J.; Kupfer E.; Nargeot J.; Lory P. T-type calcium channels are inhibited by fluoxetine and its metabolite norfluoxetine. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 1963–1968. 10.1124/mol.105.020842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chow T. W.; Pollock B. G.; Milgram N. W. Potential cognitive enhancing and disease modification effects of SSRIs for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatric Dis. Treat. 2007, 3, 627. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Taragano F. E.; Lyketsos C. G.; Mangone C. A.; Allegri R. F.; Comesaña-Diaz E. A double-blind, randomized, fixed-dose trial of fluoxetine vs. amitriptyline in the treatment of major depression complicating Alzheimer’s disease. Psychosomatics 1997, 38, 246–252. 10.1016/s0033-3182(97)71461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qiao J.; Wang J.; Wang H.; Zhang Y.; Zhu S.; Adilijiang A.; Guo H.; Zhang R.; Guo W.; Luo G.; Qiu Y.; Xu H.; Kong J.; Huang Q.; Li X.-M. Regulation of astrocyte pathology by fluoxetine prevents the deterioration of Alzheimer phenotypes in an APP/PS1 mouse model. Glia 2016, 64, 240–254. 10.1002/glia.22926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang J.; Zhang Y.; Xu H.; Zhu S.; Wang H.; He J.; Zhang H.; Guo H.; Kong J.; Huang Q.; Li X.-M. Fluoxetine improves behavioral performance by suppressing the production of soluble β-amyloid in APP/PS1 mice. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2014, 11, 672–680. 10.2174/1567205011666140812114715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kohl Z.; Winner B.; Ubhi K.; Rockenstein E.; Mante M.; Münch M.; Barlow C.; Carter T.; Masliah E.; Winkler J. Fluoxetine rescues impaired hippocampal neurogenesis in a transgenic A53T synuclein mouse model. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2012, 35, 10–19. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li W.-L.; Cai H.-H.; Wang B.; Chen L.; Zhou Q.-G.; Luo C.-X.; Liu N.; Ding X.-S.; Zhu D.-Y. Chronic fluoxetine treatment improves ischemia-induced spatial cognitive deficits through increasing hippocampal neurogenesis after stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2009, 87, 112–122. 10.1002/jnr.21829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D. F. The regulation of iron absorption and homeostasis. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2016, 37, 51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Cho H.-H.; Cahill C. M.; Vanderburg C. R.; Scherzer C. R.; Wang B.; Huang X.; Rogers J. T. Selective Translational Control of the Alzheimer Amyloid Precursor Protein Transcript by Iron Regulatory Protein-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31217–31232. 10.1074/jbc.m110.149161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Frackowiak J.; Potempska A.; Mazur-Kolecka B. Formation of amyloid-β oligomers in brain vascular smooth muscle cells transiently exposed to iron-induced oxidative stress. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 117, 557–567. 10.1007/s00401-009-0497-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Berg D.; Youdim M. B. H. Role of iron in neurodegenerative disorders. Top. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2006, 17, 5–17. 10.1097/01.rmr.0000245461.90406.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dexter D. T.; Jenner P.; Schapira A. H. V.; Marsden C. D. Alterations in levels of iron, ferritin, and other trace metals in neurodegenerative diseases affecting the basal ganglia. Ann. Neurol. 1992, 32, S94–S100. 10.1002/ana.410320716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi A.; Mohammad T.; Khan M. S.; Shahwan M.; Husain F. M.; Rehman M. T.; Hassan M. I.; Ahmad F.; Islam A. Unraveling Binding Mechanism of Alzheimer’s Drug Rivastigmine Tartrate with Human Transferrin: Molecular Docking and Multi-Spectroscopic Approach towards Neurodegenerative Diseases. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 495. 10.3390/biom9090495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z. M.; Tang P. L. Mechanisms of iron uptake by mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Cell Res. 1995, 1269, 205–214. 10.1016/0167-4889(95)00098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Tang L.; Duan R.; Hu X.; Geng F.; Zhang Y.; Peng L.; Li H. Interaction mechanisms and structure-affinity relationships between hyperoside and soybean β-conglycinin and glycinin. Food Chem. 2021, 347, 129052. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Noinaj N.; Easley N. C.; Oke M.; Mizuno N.; Gumbart J.; Boura E.; Steere A. N.; Zak O.; Aisen P.; Tajkhorshid E.; Evans R. W.; Gorringe A. R.; Mason A. B.; Steven A. C.; Buchanan S. K. Structural basis for iron piracy by pathogenic Neisseria. Nature 2012, 483, 53–58. 10.1038/nature10823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Calmettes C.; Alcantara J.; Yu R.-H.; Schryvers A. B.; Moraes T. F. The structural basis of transferrin sequestration by transferrin-binding protein B. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 358–360. 10.1038/nsmb.2251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Duan R.; Tang L.; Hu X.; Geng F.; Sun Q.; Zhang Y.; Li H. Binding mechanism and functional evaluation of quercetin 3-rhamnoside on lipase. Food Chem. 2021, 359, 129960. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad T.; Khan F. I.; Lobb K. A.; Islam A.; Ahmad F.; Hassan M. I. Identification and evaluation of bioactive natural products as potential inhibitors of human microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 4 (MARK4). J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 1813–1829. 10.1080/07391102.2018.1468282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A.; Mukaiyama A.; Itoh Y.; Nagase H.; Thøgersen I. B.; Enghild J. J.; Sasaguri Y.; Mori Y. Degradation of Interleukin 1β by Matrix Metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 14657–14660. 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R. E.; Kamran Haider M.. Hydrogen Bonds in Proteins: Role and Strength. In eLS; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. A.; Ladbury J. E. Hydrogen Bonds in Protein-Ligand Complexes. Methods Princ Med. Chem. 2003, 19, 137. 10.1002/3527601813.ch6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arcon J. P.; Defelipe L. A.; Modenutti C. P.; López E. D.; Alvarez-Garcia D.; Barril X.; Turjanski A. G.; Martí M. A. Molecular Dynamics in Mixed Solvents Reveals Protein-Ligand Interactions, Improves Docking, and Allows Accurate Binding Free Energy Predictions. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 846–863. 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Anwar S.; Khan S.; Shamsi A.; Anjum F.; Shafie A.; Islam A.; Ahmad F.; Hassan M. I. Structure-based investigation of MARK4 inhibitory potential of Naringenin for therapeutic management of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. J. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 122, 1445. 10.1002/jcb.30022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Khan S. N.; Islam B.; Yennamalli R.; Sultan A.; Subbarao N.; Khan A. U. Interaction of mitoxantrone with human serum albumin: Spectroscopic and molecular modeling studies. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 35, 371–382. 10.1016/j.ejps.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Duan R.; Tang L.; Zhou D.; Zeng Z.; Wu W.; Hu J.; Sun Q. In-vitro binding analysis and inhibitory effect of capsaicin on lipase. Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 2022, 154, 112674. 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi A.; Anwar S.; Mohammad T.; Alajmi M. F.; Hussain A.; Rehman M. T.; Hasan G. M.; Islam A.; Hassan M. I. MARK4 Inhibited by AChE Inhibitors, Donepezil and Rivastigmine Tartrate: Insights into Alzheimer’s Disease Therapy. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 789. 10.3390/biom10050789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Shamsi A.; Ahmed A.; Khan M. S.; Al Shahwan M.; Husain F. M.; Bano B. Understanding the binding between Rosmarinic acid and serum albumin: In vitro and in silico insight. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 311, 113348. 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113348. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Anwar S.; Shamsi A.; Shahbaaz M.; Queen A.; Khan P.; Hasan G. M.; Islam A.; Alajmi M. F.; Hussain A.; Ahmad F.; Hassan M. I. Rosmarinic Acid Exhibits Anticancer Effects via MARK4 Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10300. 10.1038/s41598-020-65648-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano W. L.Pymol: An Open-Source Molecular Graphics Tool; CCP4 Newsletter on protein crystallography, 2002;Vol. 40 ( (1), ), pp 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Guex N.; Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 1997, 18, 2714–2723. 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostenbrink C.; Villa A.; Mark A. E.; Van Gunsteren W. F. A biomolecular force field based on the free enthalpy of hydration and solvation: The GROMOS force-field parameter sets 53A5 and 53A6. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1656–1676. 10.1002/jcc.20090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanommeslaeghe K.; Hatcher E.; Acharya C.; Kundu S.; Zhong S.; Shim J.; Darian E.; Guvench O.; Lopes P.; Vorobyov I. CHARMM general force field: A force field for drug-like molecules compatible with the CHARMM all-atom additive biological force fields. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 671–90. 10.1002/jcc.21367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad T.; Mathur Y.; Hassan M. I. InstaDock: A single-click graphical user interface for molecular docking-based virtual high-throughput screening. Briefings Bioinf. 2021, 22, bbaa279. 10.1093/bib/bbaa279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biovia D. S.Discovery Studio Modeling Environment; Dassault Systèmes: San Diego, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- a Alhumaydhi F. A.; Aljasir M. A.; Aljohani A. S. M.; Alsagaby S. A.; Alwashmi A. S. S.; Shahwan M.; Hassan M. I.; Islam A.; Shamsi A. Probing the interaction of memantine, an important Alzheimer’s drug, with human serum albumin: In silico and in vitro approach. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 116888. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Shamsi A.; Shahwan M.; Khan M. S.; Husain F. M.; Alhumaydhi F. A.; Aljohani A. S. M.; Rehman M. T.; Hassan M. I.; Islam A. Elucidating the interaction of human ferritin with quercetin and naringenin: Implication of natural products in neurodegenerative diseases: Molecular docking and dynamics simulation insight. ACS omega 2021, 6, 7922–7930. 10.1021/acsomega.1c00527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham M. J.; Murtola T.; Schulz R.; Páll S.; Smith J. C.; Hess B.; Lindahl E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1-2, 19–25. 10.1016/j.softx.2015.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Aalten D. M. F.; Bywater R.; Findlay J. B. C.; Hendlich M.; Hooft R. W. W.; Vriend G. PRODRG, a program for generating molecular topologies and unique molecular descriptors from coordinates of small molecules. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1996, 10, 255–262. 10.1007/bf00355047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi A.; Mohammad T.; Anwar S.; Alajmi M. F.; Hussain A.; Hassan M. I.; Ahmad F.; Islam A. Probing the interaction of Rivastigmine Tartrate, an important Alzheimer’s drug, with serum albumin: Attempting treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 533–542. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David C. C.; Jacobs D. J.. Principal component analysis: a method for determining the essential dynamics of proteins. In Protein Dynamics; Springer, 2014; pp 193–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altis A.; Otten M.; Nguyen P. H.; Hegger R.; Stock G. Construction of the free energy landscape of biomolecules via dihedral angle principal component analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 245102. 10.1063/1.2945165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaleo E.; Mereghetti P.; Fantucci P.; Grandori R.; De Gioia L. Free-energy landscape, principal component analysis, and structural clustering to identify representative conformations from molecular dynamics simulations: the myoglobin case. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2009, 27, 889–899. 10.1016/j.jmgm.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari R.; Kumar R.; Lynn A.; Lynn A. g_mmpbsa-A GROMACS Tool for High-Throughput MM-PBSA Calculations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54, 1951–1962. 10.1021/ci500020m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Anwar S.; Mohammad T.; Shamsi A.; Queen A.; Parveen S.; Luqman S.; Hasan G. M.; Alamry K. A.; Azum N.; Asiri A. M.; Hassan M. I. Discovery of Hordenine as a potential inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 3: implication in lung Cancer therapy. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 119. 10.3390/biomedicines8050119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Anwar S.; Shamsi A.; Shahbaaz M.; Queen A.; Khan P.; Hasan G. M.; Islam A.; Alajmi M. F.; Hussain A.; Ahmad F. Rosmarinic Acid exhibits Anticancer Effects via MARK4 Inhibition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10300–13. 10.1038/s41598-020-65648-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan P.; Rahman S.; Queen A.; Manzoor S.; Naz F.; Hasan G. M.; Luqman S.; Kim J.; Islam A.; Ahmad F. Elucidation of dietary polyphenolics as potential inhibitor of microtubule affinity regulating kinase 4: in silico and in vitro studies. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9470–15. 10.1038/s41598-017-09941-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.