Abstract

Low-temperature selective catalytic oxidation (SCO) is crucial for removing the NH3 slip from the upstream of NH3-selective catalytic reduction (NH3-SCR). Herein, combining zeolite Cu-SAPO34 and the active oxidant mullite SmMn2O5, we developed mixed-phase catalysts SmMn2O5/Cu-SAPO34 by grinding powder mixtures to achieve a low-temperature activity and a reasonable N2 selectivity. The physicochemical properties of the catalysts were characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) measurement, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS). The evaluation of NH3 oxidation activity showed that for 30 wt % SmMn2O5/Cu-SAPO34, 90% NH3 conversion was at a temperature of 215 °C in the presence of 500 ppm NH3 and 21% O2 balanced with N2. The in situ DRIFTS spectra reveal the internal SCR mechanism (i-SCR), i.e., NH3 oxidizing to NOx on mullite and NOx subsequently to proceed with SCR reactions, leading to higher conversion and selectivity over the mixed catalysts. This work provides a strategy to design the compound catalyst to achieve low-temperature NH3 oxidation via synergistic utilization of the advantages of each individual catalyst.

1. Introduction

Gas ammonia is an important industrial and agricultural chemical although it causes irritation and is corrosive. However, the direct emission into the atmosphere is detrimental to the environment and the health of living beings. NH3 can react with other pollutants to generate ammonium nitrate and ammonium sulfate particles leading to PM2.5 pollution, and it also directly causes damage to the respiratory tract and mucous membranes. The main pollution sources could originate from ammonia synthesis, vehicle exhausts, and modern agricultural and industrial production.1 In urban areas, NH3 pollution is mainly from vehicle exhausts and has increased rapidly in recent years. With the gradual progress in the control of pollutants such as NOx and PM2.5, NH3 pollution has become prominent. NH3 can be removed by various methods such as absorption, catalytic decomposition, catalytic oxidation, and biodegradation,2−6 among which selective catalytic oxidation (SCO) is potentially promising for effective NH3 removal. To achieve high efficiency and high N2 selectivity of SCO, an effective catalyst is required.

The current NH3-SCO catalysts fall into three categories, i.e., metal-modified zeolites like Cu-β, Fe-ZSM-5, Ag-Y, Fe-β, and Cu-SSZ-13;7−10 supported transition metal oxide catalysts such as MnO2, ZrO2, CuO, and Fe2O3;11−15 and supported noble metal catalysts including Ru, Pt, Rh, and Ag.16−21 The noble metal catalysts normally exhibit a low oxidation temperature (<200 °C) with ∼90% NH3 conversion. Owing to their high cost and limited abundance, extensive studies have been carried out to focus on the supported nonprecious system and metal-modified zeolites. Although these catalysts normally show high N2 selectivity, their NH3 conversion temperature would be rather higher (300–500 °C) with regard to precious catalysts.

For the treatment of the NH3 slip from the upstream of selective catalytic reduction (SCR) in diesel engine exhaust, parts of the reactions follow the internal selective catalytic reduction (i-SCR) mechanism to convert NH3 into NOx and subsequently experience SCR to produce N2 and H2O. During the whole process, it is challenging to achieve high conversion at a low temperature and high selectivity at the same active site simultaneously. Therefore, it would be insightful to develop a mixed catalyst to oxidize NH3 into NOx over one individual catalyst with strong oxidizing capability and subsequently react with NH3 to achieve SCR reactions over another with high SCR performance.

In this work, we proposed combining mullite oxide with Cu-SAPO34 to achieve highly efficient NH3 conversion simultaneously at a low temperature. Mn-based mullite SmMn2O5 has been reported to exhibit remarkable oxidizing properties, which are ascribed to the unique dz2 orbital electronic structure in the vicinity of the Fermi level.22,23 Active sites have been identified in the Mn–Mn dimers for NO oxidation.24 The A-site element in mullite helps stabilize the crystal structure, making it more stable than binary manganese oxide. Meanwhile, silicoaluminophosphate (SAPO) zeolite Cu-SAPO34 with the CHA framework structure has been proved to be an efficient catalyst for SCR reactions.25,26 However, NH3 oxidation of zeolite at low temperatures is inferior owing to the difficult activation of N–H bonds. Through mixing SmMn2O5 and Cu-SAPO34, the i-SCR process of NH3 oxidation can be realized to significantly improve the low-temperature NH3 conversion and selectivity of N2.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Characterization of SMO/CS Mixed Catalysts

As described above, SmMn2O5 and Cu-SAPO34 were ground together (Figure 1a). To check the phase structures of the mixed catalysts, we carried out X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements as shown in Figure 1b. It is shown that both individual SmMn2O5 and Cu-SAPO34 are pure phases. When mixing different amounts of SmMn2O5 with Cu-SAPO34, the two phases are maintained and no other phases are observed (Figure S1). Only 30-SMO/CS is included, as shown in Figure 1b due to its high NH3 conversion and N2 selectivity discussed in the performance characterization. Analogously, a mixed-phase refers to 30-SMO/CS in the main text in the following.

Figure 1.

(a) Catalyst preparation schematics and (b) XRD patterns of SmMn2O5, Cu-SAPO34, and the mixed catalyst 30-SMO/CS.

To further study the morphologies of the pure phase and the mixed ones, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) measurements were conducted, as shown in Figure 2. More SEM images of different compound catalysts with various SmMn2O5 loadings are shown in Figure S2. For the pure phase of SmMn2O5, rodlike shapes are observed with a length varying from 100 to 200 nm and a diameter of about 30 nm. The synthesized Cu-SAPO34 exhibits a cubic shape with a cell length of 2–4 μm. When grinding the two powders, as shown in Figure 2d, most of the SmMn2O5 comes in contact with Cu-SAPO34. Elemental mapping of P (Figure 2f) clearly shows the cubic shape of Cu-SAPO34, while Sm and Mn distributions are also cubic-like. In addition to the SmMn2O5 attached to Cu-SAPO34, separated SmMn2O5 is also found, being consistent with SEM images and EDS mappings (Figure 2d–h). It can be seen that the particles of SmMn2O5 on the Cu-SAPO34 surface increase in quantity significantly, along with increasing the SmMn2O5 content. Meanwhile, the specific surface area of mixed catalysts shows a significant linear change owing to the large difference between the specific surface areas of SmMn2O5 (66 m2/g) and Cu-SAPO34 (589 m2/g) displayed in Figure S3.

Figure 2.

SEM images of (a) SmMn2O5, (b, c) Cu-SAPO34, and (d) 30-SMO/CS. (e) SEM image and (f–h) elemental mappings of P, Mn, and Sm of 30-SMO/CS, respectively.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the 30-SMO/CS sample with different zoom-in magnifications are shown in Figure 3. Figure 3a describes one part of Cu-SAPO34 together with SmMn2O5. The SmMn2O5 nanorods aggregate to form particles and locate on the surfaces of the cubic, which are also observed in the higher magnification of images in Figure 3b. Additionally, pure nanoparticles are also identified in Figure 3c. Heart-shaped SmMn2O5 shows a (131) surface facet with a spacing of 0.241nm.

Figure 3.

(a–c) TEM images of 30-SMO/CS with different magnifications.

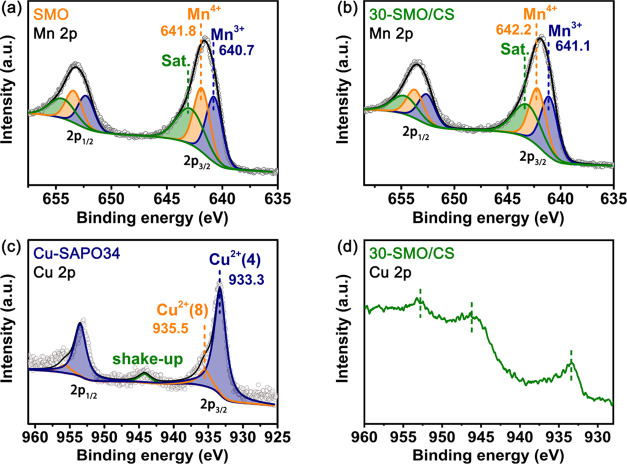

Valence states of active elements are crucial for governing the catalytic performance. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was thus carried out to access the valence states of active manganese and copper in SmMn2O5 and 30-SMO/CS, respectively. The XPS spectra of Mn 2p and Cu 2p are presented in Figure 4 (see Figure S4 for survey spectra information). The Mn 2p peak was fitted with the subpeaks of Mn3+ and Mn4+. For the pure phase SmMn2O5, the peaks at 640.7 and 641.8 eV represent Mn3+ and Mn4+, respectively (Figure 4a). The Mn4+/Mn3+ atomic ratio of SmMn2O5 is 0.98 as calculated with the XPSPEAK, which is less than the unit ratio in the pristine mullite oxide. This might indicate that oxygen vacancies VO on the surface of SmMn2O5 exist. Due to the VO existence, O2 might compensate the vacancy site and form atomic oxygen O* for the subsequent reactions, which might follow the MvK mechanisms.27 For 30-SMO/CS, no observable shift of the Mn 2p peak is detected compared with the pure phase of SmMn2O5 since electron transfer is difficult for physically mixed SmMn2O5 and Cu-SAPO34. The Mn4+/Mn3+ atomic ratio is 0.96, slightly lower than that of the pure SmMn2O5. The Cu 2p peak of the pure phase Cu-SAPO34 comprises subpeaks of different Cu2+, as the sample was calcined at 600 °C and the Cu+ had been fully oxidized. The peaks at 933.3 and 953.5 eV represent the Cu2+ of the tetrahedral coordination (Cu2+(4)) and the higher peaks at 935.5 and 955.7 eV represent the Cu2+ of the octahedral coordination (Cu2+(8)) due to a stronger bond with the zeolite framework. The existence of the shake-up at about 944 eV also proves the presence of Cu2+.28−30 For 30-SMO/CS, the intensity of Cu 2p is quite weak and interfered with the auger peak of Mn (946 eV).31 It is thus difficult to distinguish the Cu valence states in the range 940–960 eV. Nevertheless, Cu2+ might be retained since Cu2+ is observed from 933.4 eV.

Figure 4.

XPS spectra of Mn in (a) SmMn2O5 and (b) 30-SMO/CS; Cu in (c) Cu-SAPO34 and (d) 30-SMO/CS.

2.2. Evaluation of NH3 Oxidation Activity

To determine the synergistic effect of SmMn2O5 on Cu-SAPO34 for NH3 oxidation, the catalytic performance of SmMn2O5/Cu-SAPO34 was measured with regard to the commercial catalyst 1% Pt/Al2O3 (Figure 5). For zeolite Cu-SAPO34 alone, NH3 conversion starts at above 200 °C and reaches about only 10% at 300 °C (Figure 5a), making it unnecessary to discuss the selectivity of Cu-SAPO34. On the other hand, the individual SmMn2O5 catalyst shows high NH3 conversion with 100% NH3 conversion at 215 °C. This result confirms SmMn2O5 to be a strong oxidant. When varying amounts of SmMn2O5 are mixed with the zeolite, the low-temperature activity gradually decreases with more Cu-SAPO34 (Figure S5). Specifically, for the 30-SMO/CS sample, NH3 oxidation is more efficiently compared with the 1% Pt/Al2O3 catalyst.

Figure 5.

Comparison of (a) NH3 conversion and (b) N2 selectivity of SmMn2O5, Cu-SAPO34, 1% Pt/Al2O3, and 30-SMO/CS during NH3 oxidation (NH3-SCO reaction conditions: 500 ppm NH3 and 21% O2 balanced with N2, gas hourly space velocity, GHSV = 100 000 h–1).

In NH3 oxidation, high NH3 conversion does not necessarily mean high N2 production. Instead, in most oxidation processes, NO, NO2, and N2O, referring to NOx, are normally observed in addition to N2.32−34 For practical applications, by-products NOx should be ultimately suppressed to avoid their emission to cause secondary pollution. For the SmMn2O5 catalyst, although the NH3 conversion temperature is low, N2 selectivity is less than 60% at 189 °C. Continuing to increase the temperature leads to a linear decrease of the selectivity. N2 production is ascribed to the i-SCR mechanism. Specifically, NH3 is oxidized into NOx that subsequently reacts with NH3 and O2 to produce environmentally benign nitrogen. However, for zeolite, oxidation of NH3 into NOx is difficult especially for the first step to activate N–H bonds. Therefore, Cu-SAPO34 requires a much higher temperature, as shown in Figure 5a.

To mimic the lifetime of the catalyst, we performed the hydrothermal aging on 30-SMO/CS. The catalyst was treated with 10% H2O at 800 °C for 5 h and after that, the oxidation performance reduced, as shown in Figure S7. The fundamental origin of the reduction is still open to questions. To make the catalyst more practical in future work, one needs to improve the tolerance of SmMn2O5/Cu-SAPO34 against hydrothermal aging and SO2 poisoning.

2.3. In Situ Diffuse Reflectance Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) of NH3 Adsorption and the Reaction Mechanism

The in situ DRIFTS spectra are shown in Figure 6. For preadsorbed NH3 reacting with O2 at 230 °C, the catalyst was exposed to an NH3 atmosphere (500 ppm) for 30 min and then purged with N2 for 30 min at 30 °C. About 21% of O2 balanced with N2 was introduced after completing the preadsorption of NH3. For NH3 + O2 reacting at different temperatures, the catalyst was exposed to NH3 + O2 (500 ppm NO and 21% O2) after dehydration. The temperature was raised from 135 to 390 °C after the spectra were stabilized at each measured temperature point. There are two hydroxyl-induced negative bands (3618 and 3599 cm–1) over 30-SMO/CS, which could be suppressed by NH3 adsorption.10,19,32 Meanwhile, several adsorption bands (3379, 3271, 3190, 1724, 1612, 1454, 1278, and 1213 cm–1) are observed as well (Figure 6a,b). The N–H stretching vibration bands are mainly located between 3100 and 3400 cm–1. The bands at 3379 and 3271 cm–1 indicate N–H vibrations in the NH4+ species and the band at 3190 cm–1 represents the vibrations in adsorbed NH3.10,3510,35 The bands in the range of 1100–1700 cm–1 show the adsorption on the acid sites in the catalyst. Specifically, the bands at 1454 (1462 cm–1 in Figure S8a) and 1724 cm–136−39 are related to the NH4+ groups adsorbed on Brønsted acid sites and the bands at 1213 and 1612 cm–1 40−4240−42 are assigned to NH3 adsorbed on the Lewis acid sites. The appearance of the 1278 cm–1 band is slightly slower than that of other bands, presuming that it is the monodentate nitrate adsorption peak formed after NH3 oxidation by the lattice oxygen on the catalyst.19,32,43 There is only one weak band of NH3 adsorbed on the Lewis acid sites at 1184 cm–1 43,4443,44 over SmMn2O5. Several bands of nitrate appear as the temperature increases (Figure 6c). Due to strong oxidation, the bands at 1550, 1275, and 1235 cm–1 41,43,4541,43,45 were assigned to bidentate nitrate, monodentate nitrate, and bridged nitrate, respectively.

Figure 6.

In situ DRIFTS spectra of (a) preadsorbed NH3 reacting with O2 at 230 °C over 30-SMO/CS, (b) NH3 + O2 reacting over 30-SMO/CS at different temperatures, and (c) NH3 + O2 reacting over SmMn2O5 at different temperatures.

The changes of preadsorbed NH3 reacting with O2 over Cu-SAPO34 and SmMn2O5 are displayed in Figure S8. At 230 °C, the NH3 adsorbed on Cu-SAPO34 almost remains the same with no change. While for SmMn2O5, it could be observed that NH3 adsorbed on the Lewis acid sites (1184 cm–1) was consumed and two new strong bands of bidentate nitrate (1538 cm–1) and bridged nitrate (1248 cm–1) appeared simultaneously indicating that NH3 adsorbed on SmMn2O5 is easily oxidized to NOx. When SmMn2O5 was combined with Cu-SAPO34, NH3 adsorbed on the catalyst showed a completely different scenario. During the reaction of preadsorbed NH3 with O2, the intensity of all bands decreases with increasing the time from 0 to 30 min. The bands corresponding to the Brønsted acid sites and Lewis acid sites have all reduced, demonstrating that NH3 adsorbed on both acid sites can participate in the NH3 oxidation reaction.

The oxidation process occurring on 30-SMO/CS is explored in combination with in situ DRIFTS spectra and NH3 oxidation activity results. To facilitate the analysis, high temperatures and low temperatures are divided depending on the presence of NH3 in the mixture of product gases. The concentration changes of each gas component (Figure S6) clearly show that the oxidation products include NO, NO2, N2, and the by-product N2O. At low temperatures (<∼230 °C), only NH3 and N2O can be detected. Figure 6c shows that SmMn2O5 has the capability to activate the N–H bond and oxidize NH3 to generate nitrate below 230 °C, and thus, it is reasonable to assume that NH3 is first oxidized to NOx at low temperatures. NH3 is in excess, leading to an SCR reaction with NOx, which is also the main source of N2 in the product. It explains the absence of NO and NO2 emissions at low temperatures as well. NH3 oxidation over individual Cu-SAPO34 is rather inactive below 300 °C. The by-product N2O is widely known to be composed of ammonium nitrate formed from NH3 and NO.28,46,47 As the temperature increases, the catalyst gradually shows stronger oxidizing ability and more NO is formed during the reaction. In the case where NH3 is not completely consumed, the amount of N2O also tends to increase with temperature. At high temperatures (>∼230 °C), excessive oxidation of NH3, one of the reactants of SCR, causes a gradual decrease in N2 selectivity for the catalyst with stronger oxidizing properties. At the same time, with the increase of temperature, the SCR activity of Cu-SAPO34 is enhanced. Thus, on 10-SMO/CS with relatively weak oxidization, N2 selectivity is improved compared with the individual SmMn2O5. SmMn2O5 can oxidize NH3 at high temperatures to generate a large amount of nitrate, and it also reduces the NH3 combining with NOx to form ammonium nitrate. Thus, N2O shows a downward trend after NH3 disappears.

In summary, at low temperatures, NH3 is oxidized to NOx on SmMn2O5 and then follows an SCR reaction to generate N2 on either SmMn2O5 or Cu-SAPO34. At high temperatures, the difference is from the larger portion of NH3 oxidation on SmMn2O5 so that the reactant NH3 is insufficient during the SCR and leads to an excess of NOx in the final products. Generally speaking, the overall reaction follows the i-SCR mechanism. In future work to further improve the N2 selectivity of the SMO/Cu-SAPO34 catalyst, mixing mullite and Cu-SAPO34 through chemical methods could be an effective way to control the oxidation activity through the interface.

3. Conclusions

Mullite and zeolite mixed catalysts, SmMn2O5/Cu-SAPO34, were synthesized via hydrothermal synthesis and subsequent grinding. By the XRD, XPS, and TEM measurements, no phase changes were observed before and after mixing the two catalysts. We found that with the increase of the SmMn2O5 content from 10 to 40 wt %, Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surfaces decrease linearly. For the 30-SMO/CS, 90% NH3 conversion was at 215 °C in the presence of 500 ppm NH3 and 21% O2 balanced with N2. Further using DRIFTS spectra it was found that the whole oxidation process follows the internal SCR mechanism (i-SCR), i.e., NH3 oxidizing into NOx on mullite and NOx subsequently transferring to Cu-SAPO34 to achieve SCR reactions on both mullite and Cu-SAPO34. Through the combination of the two individual catalysts, we provide insights into the compound catalyst design via synergistically utilizing the advantages of each individual catalyst.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Catalyst Preparation

SmMn2O5 was prepared by a one-step facile hydrothermal method without any surfactants, as described in the literature.22 About 1.112 g of Sm(NO3)3, 0.237 g of KMnO4, and 0.858 g of Mn(CH3CO2)·4H2O were dissolved in water and stirred for 30 min followed by dropwise addition of 0.91 g of NaOH dissolved in water. Then, the mixed solution continued to be stirred at room temperature for 30 min before loading into an autoclave reacting for 12 h at 200 °C. Subsequently, the precipitate was filtered and washed with dilute nitric acid and deionized water several times prior to drying at 80 °C for 4 h.

The synthesis of Cu-SAPO34 was as follows. The phosphoric acid was dripped into the bauxite solution and agitated fully to get a sticky gel. Then, amorphous silica and hydrated copper sulfate were added. After thoroughly stirring, tetraethylenepentamine was added. After stirring for 1 h, n-propylamine was added to the above system followed by stirring at room temperature for 12 h before the hydrothermal reaction at 200 °C for 2 days. The chemical ratio is 1Al2O3: 1.14P2O5: 0.57SiO2: 75H2O: 0.3Cu: 0.3 tetraethylenepentamine: 2.4 n-propylamine. The products were thoroughly washed and dried at 80 °C after the reaction was completed. Cu-SAPO34 was calcined at 600 °C for 5 h before synthesizing the mixed catalyst.

The mixed catalyst was obtained by grinding the mixture powder of SmMn2O5 and Cu-SAPO34 using a ceramic mortar until the powder became uniform. For simplicity, the mixed catalyst was abbreviated as x-SMO/CS. SMO represents SmMn2O5, CS represents Cu-SAPO34, and x represents the weight percent of SmMn2O5 in the mixed catalyst. The powder catalyst of 1 wt % Pt/Al2O3 used for comparison was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

4.2. Characterization

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns ranging from 5 to 75 in 2θ were taken with an Ultima IV diffractometer (Rigaku) operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The morphology, particle size, and element distribution were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with an energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) using MERLIN Compact (ZEISS). The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of samples were obtained with a JEM-2010FEF microscope (JEOL) operated at 200 kV. The specific surface area of catalysts was calculated by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method using a 3H-2000PM2 analyzer (BeiShiDe Instrument). The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra were analyzed with a Thermo Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi electron spectrometer with a monochromatized Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV). The C 1s peak at 284.5 eV was used to calibrate the binding energies. The in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements were carried out on a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 spectrometer. All of the samples were dehydrated under a N2 atmosphere at 200 °C for 2 h prior to the DRIFTS study.

4.3. Catalytic Activity Characterization

The prepared samples were pelletized and sieved to ensure that the particle size varied from 550 to 880 μm. The NH3 oxidation activities of catalysts were measured in a temperature-programmed reactor. Briefly, 1 mL of the catalyst was loaded into a quartz tube reactor with a porous baffle in the middle and silica wool was placed under the catalyst to prevent the sample from being blown off. The feed gas for the NH3-SCO reaction passed through the tube reactor from top to bottom containing 500 ppm NH3 and 21% O2 balanced with N2 (GHSV = 100 000 h–1). The reaction temperature ranged from 130 to 300 °C and each test temperature was maintained stable for 30 min to reach the reaction equilibrium. The concentrations of NH3, NO, NO2, and N2O were detected using a Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) with a 5 m gas cell heated to 120 °C. For the final concentration results of each component, the average values obtained by multiple sampling were taken to reduce sampling errors. The NH3 conversion was calculated according to the following equation

N2 selectivity was defined as

As the FT-IR spectrometer failed to detect N2, due to no dipole moment change during the vibrations, the actual N2 concentration was calculated according to the following equation

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21975136), the Tianjin City Distinguish Young Scholar Fund (No. 17JCJQJC45100), and the Shenzhen Science, Technology, and Innovation Committee under the project contract (No. JCYJ20190808151603654).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c06648.

XRD patterns; SEM images and elemental maps; specific surface areas; full XPS spectra; comparison of NH3 conversion and N2 selectivity; concentration changes of NH3, NO, NO2, and N2O; NH3 conversion of 30-SMO/CS before and after hydrothermal aging; and in situ DRIFTS spectra (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Changzhi University, Changzhi 046011, China

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Warneck P.Chemistry of the Natural Atmosphere; Academic Press: San Diego, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangun C. L.; Braatz R. D.; Economy J.; Hall A. J. Fixed bed adsorption of acetone and ammonia onto oxidized activated carbon fibers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1999, 38, 3499–3504. 10.1021/ie990064m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C. H.; Chu H.; Cho C. M. Absorption and reaction kinetics of amines and ammonia solutions with carbon dioxide in flue gas. J. Air Waste Manage. Assoc. 2003, 53, 246–252. 10.1080/10473289.2003.10466139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez M.; Gómez J. M.; Aroca G.; Cantero D. Removal of ammonia by immobilized Nitrosomonas europaea in a biotrickling filter packed with polyurethane foam. Chemosphere 2009, 74, 1385–1390. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüth F.; Palkovits R.; Schlögl R.; Su D. S. Ammonia as a possible element in an energy infrastructure: catalysts for ammonia decomposition. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 6278–6289. 10.1039/C2EE02865D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Zhang C.; He H. The role of silver species on Ag/Al2O3 catalysts for the selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen. J. Catal. 2009, 261, 101–109. 10.1016/j.jcat.2008.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin T.; Lenihan S. Copper exchanged beta zeolites for the catalytic oxidation of ammonia. Chem. Commun. 2003, 1280–1281. 10.1039/b301894f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akah A. C.; Nkeng G.; Garforth A. A. The role of Al and strong acidity in the selective catalytic oxidation of NH3 over Fe-ZSM-5. Appl. Catal., B 2007, 74, 34–39. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2007.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Góra-Marek K.; Tarach K. A.; Piwowarska Z.; Łaniecki M.; Chmielarz L. Ag-loaded zeolites Y and USY as catalysts for selective ammonia oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 1651–1660. 10.1039/C5CY01446H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T.; Chang H. Z.; You Y. C.; Shi C. N.; Li J. H. Excellent Activity and Selectivity of One-Pot Synthesized Cu-SSZ-13 Catalyst in the Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Ammonia to Nitrogen. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 4802–4808. 10.1021/acs.est.8b00267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z.; Fan R.; Wang Z.; Wang H.; Miao L. Selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen over MnO2 prepared by urea-assisted hydrothermal method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 351, 573–579. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.05.154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Can F.; Berland S.; Royer S.; Courtois X.; Duprez D. Composition-Dependent Performance of CexZr1–xO2 Mixed-Oxide-Supported WO3 Catalysts for the NOx Storage Reduction–Selective Catalytic Reduction Coupled Process. ACS Catal. 2013, 3, 1120–1132. 10.1021/cs3008329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chmielarz L.; Węgrzyn A.; Wojciechowska M.; Witkowski S.; Michalik M. Selective catalytic oxidation (SCO) of ammonia to nitrogen over hydrotalcite originated Mg–Cu–Fe mixed metal oxides. Catal. Lett. 2011, 141, 1345–1354. 10.1007/s10562-011-0653-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song S.; Jiang S. Selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen over CuO/CNTs: the promoting effect of the defects of CNTs on the catalytic activity and selectivity. Appl. Catal., B 2012, 117, 346–350. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. L.; Wang H. M.; Ning P.; Song Z. X.; Liu X.; Duan Y. K. In situ DRIFTS studies on CuO-Fe2O3 catalysts for low temperature selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 419, 733–743. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.05.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J.; Yang K. X.; Ma C. J.; Zhang N.; Gai H. J.; Zheng J. B.; Chen B. H. Bimetallic Ru–Cu as a highly active, selective and stable catalyst for catalytic wet oxidation of aqueous ammonia to nitrogen. Appl. Catal., B 2016, 184, 216–222. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M. M.; Wang S. N.; Li Y. S.; Xu H. D.; Chen Y. Q. Promotion of catalytic performance by adding W into Pt/ZrO2 catalyst for selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 402, 323–329. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.12.241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hung C. M. Characterization and performance of Pt-Pd-Rh cordierite monolith catalyst for selectivity catalytic oxidation of ammonia. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 180, 561–565. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.04.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F.; Ma J. Z.; He G. Z.; Chen M.; Zhang C. B.; He H. Nanosize Effect of Al2O3 in Ag/Al2O3 Catalyst for the Selective Catalytic Oxidation of Ammonia. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2670–2682. 10.1021/acscatal.7b03799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lousteau C.; Besson M.; Descorme C. Catalytic wet air oxidation of ammonia over supported noble metals. Catal. Today 2015, 241, 80–85. 10.1016/j.cattod.2014.03.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Liu F. D.; Yu Y. B.; Liu Y. C.; Zhang C. B.; He H. Effects of Adding CeO2 to Ag/Al2O3 Catalyst for Ammonia Oxidation at Low Temperatures. Chin. J. Catal. 2011, 32, 727–735. 10.1016/S1872-2067(10)60220-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Yang Z.; Liu J.; Yao X.; Xiong K.; Liu H.; Wang W.; Lu F.; Wang W. Electronic properties and native point defects of high efficient NO oxidation catalysts SmMn2O5. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 211903 10.1063/1.4968786. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H.; Wang W.; Qian X.; Cheng Y.; Xie X.; Liu J.; Sun S.; Zhou J.; Hu Y.; Xu J.; et al. Identifying Descriptor of Governing NO Oxidation on Mullite Sm(Y, Tb, Gd, Lu)Mn2O5 for Diesel Exhaust Cleaning. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 3971–3975. 10.1039/C5CY01798J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. C.; McCool G.; Kapur N.; Yuan G.; Shan B.; Nguyen M.; Graham U. M.; Davis B. H.; Jacobs G.; Cho K.; et al. Mixed-phase oxide catalyst based on Mn-mullite (Sm, Gd) Mn2O5 for NO oxidation in diesel exhaust. Science 2012, 337, 832–835. 10.1126/science.1225091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X. Q.; Yang M.; Fan D. Q.; Qi G. S.; Wang J.; Wang J. Q.; Yu T.; Li W.; Shen M. Q. The role of pore diffusion in determining NH3 SCR active sites over Cu/SAPO-34 catalysts. J. Catal. 2016, 341, 55–61. 10.1016/j.jcat.2016.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang X.; Wu P.; Cao Y.; Cao L.; Wang Q.; Xu S. T.; Tian P.; Liu Z. Investigation of low-temperature hydrothermal stability of Cu-SAPO-34 for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. Chin. J. Catal. 2017, 38, 918–927. 10.1016/S1872-2067(17)62836-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia J. M.; Prinsloo F. F.; Niemantsverdriet J. W. Mars-van Krevelen-like Mechanism of CO Hydrogenation on an Iron Carbide Surface. Catal. Lett. 2009, 133, 257–261. 10.1007/s10562-009-0179-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D.; Yang R. T. N2O Formation Pathways over Zeolite-Supported Cu and Fe Catalysts in NH3-SCR. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 2170–2182. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b03405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pereda-Ayo B.; De La Torre U.; Illán-Gómez M. J.; Bueno-López A.; González-Velasco J. R. Role of the different copper species on the activity of Cu/zeolite catalysts for SCR of NOx with NH3. Appl. Catal., B 2014, 147, 420–428. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2013.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liakakou E. T.; Isaacs M. A.; Wilson K.; Lee A. F.; Heracleous E. On the Mn promoted synthesis of higher alcohols over Cu derived ternary catalysts. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 988–999. 10.1039/C7CY00018A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. F.; Chastain J.; King R. C. Jr. Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: A Reference Book of Standard Spectra for Identification and Interpretation of XPS Data; Perkin-Elmer Corporation: Eden Prairie, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Song D.; Shao X.; Yuan M.; Wang L.; Zhan W.; Guo Y.; Guo Y.; Lu G. Selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia over MnOx–TiO2 mixed oxides. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 88117–88125. 10.1039/C6RA20999H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha S.; Harold M. P.; Kamasamudram K.; Yezerets A. Selective oxidation of ammonia on mixed and dual-layer Fe-ZSM-5+Pt/Al2O3 monolithic catalysts. Catal. Today 2014, 231, 105–115. 10.1016/j.cattod.2014.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jabłońska M.; Król A.; Kukulska-Zajac E.; Tarach K.; Chmielarz L.; Góra-Marek K. Zeolite Y modified with palladium as effective catalyst for selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen. J. Catal. 2014, 316, 36–46. 10.1016/j.jcat.2014.04.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M.; Jiang B. Q.; Yao S. L.; Han J. Y.; Zhao S.; Tang X. J.; Zhang J. W.; Wang T. Mechanism of NH3 Selective Catalytic Reduction Reaction for NOx Removal from Diesel Engine Exhaust and Hydrothermal Stability of Cu–Mn/Zeolite Catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 122, 455–464. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b09339. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F. D.; He H.; Ding Y.; Zhang C. B. Effect of manganese substitution on the structure and activity of iron titanate catalyst for the selective catalytic reduction of NO with NH3. Appl. Catal., B 2009, 93, 194–204. 10.1016/j.apcatb.2009.09.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long R. Q.; Yang R. T. Selective Catalytic Reduction of Nitrogen Oxides by Ammonia over Fe3+-Exchanged TiO2 -Pillared Clay Catalysts. J. Catal. 1999, 186, 254–268. 10.1006/jcat.1999.2558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G.; Shi Jw.; Liu C.; Gao C.; Fan Z.; Niu C. Mn/CeO2 catalysts for SCR of NOx with NH3: comparative study on the effect of supports on low-temperature catalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 411, 338–346. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. Q.; Li R.; Li Z. B.; Yuan F. L.; Niu X. Y.; Zhu Y. J. Effect of Ni doping in NixMn1–xTi10 (x = 0.1–0.5) on activity and SO2 resistance for NH3-SCR of NO studied with in situ DRIFTS. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 3243–3257. 10.1039/C7CY00672A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P.; Guo R. T.; Liu S. M.; Wang S. X.; Pan W. G.; Li M. Y. The enhanced performance of MnOx catalyst for NH3-SCR reaction by the modification with Eu. Appl. Catal., A 2017, 531, 129–138. 10.1016/j.apcata.2016.10.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L.; Cui S. P.; Guo H. X.; Zhang L. J. The effect of alkali metal over Mn/TiO2 for low-temperature SCR of NO with NH3 through DRIFT and DFT. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 144, 216–222. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2017.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S. J.; Fu Y. W.; Liao Y.; Xiong S. C.; Qu Z.; Yan N. Q.; Li J. H. Competition of selective catalytic reduction and non selective catalytic reduction over MnOx/TiO2 for NO removal: the relationship between gaseous NO concentration and N2O selectivity. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 224–232. 10.1039/C3CY00648D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nam K. B.; Kwon D. W.; Hong S. C. DRIFT study on promotion effects of tungsten-modified Mn/Ce/Ti catalysts for the SCR reaction at low-temperature. Appl. Catal., A 2017, 542, 55–62. 10.1016/j.apcata.2017.05.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P.; Guo R. T.; Liu S. M.; Wang S. X.; Pan W. G.; Li M. Y.; Liu S. W.; Liu J.; Sun X. Enhancement of the low-temperature activity of Ce/TiO2 catalyst by Sm modification for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. Mol. Catal. 2017, 433, 224–234. 10.1016/j.mcat.2016.12.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H.; Cai S. X.; Li H. R.; Huang L.; Shi L. Y.; Zhang D. S. In Situ DRIFTs Investigation of the Low-Temperature Reaction Mechanism over Mn-Doped Co3O4 for the Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 22924–22933. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b06057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Machida M.; Tokudome Y.; Maeda A.; Koide T.; Hirakawa T.; Sato T.; Tsushida M.; Yoshida H.; Ohyama J.; Fujii K.; Ishikawa N. Nanometric Iridium Overlayer Catalysts for High-Turnover NH3 Oxidation with Suppressed N2O Formation. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 32814–32822. 10.1021/acsomega.0c05443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busca G.; Lietti L.; Ramis G.; Berti F. Chemical and mechanistic aspects of the selective catalytic reduction of NOx by ammonia over oxide catalysts: A review. Appl. Catal., B 1998, 18, 1–36. 10.1016/S0926-3373(98)00040-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.