Abstract

Introduction

The aims of this observational study were to determine if endodontists' practices in early 2021 experienced changes in patient characteristics compared with a comparable prepandemic period and to determine whether the changes reported during the initial outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2020 were reversed 1 year later.

Methods

Demographic, diagnostic, and procedural data of 2657 patient visits from 2 endodontist private offices from March 16 to May 31 in 2019, 2020, and 2021 were included. Bivariate analyses and multiple logistic regression models were used to examine the impact of ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on patient data.

Results

Bivariate analyses showed that patients' self-reported pain levels and the number of visits with irreversible pulpitis in 2021 were higher than 2019 (P < .05). Patients' self-reported pain, percussion pain, and palpation pain levels in 2021 were less than 2020 (P < .05). Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that endodontists' practices in 2021 had an increase in the number of nonsurgical root canal treatments (odds ratio [OR] = 1.482; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.102–1.992), and apicoectomies (OR = 2.662; 95% CI, 1.416–5.004) compared with 2019. Compared with the initial outbreak in 2020, endodontists' practices in 2021 had visits with older patients (OR = 1.288; 95% CI, 1.045–1.588), less females (OR = 0.781; 95% CI, 0.635–.960), more molars (OR = 1.389; 95% CI, 1.065–1.811), and less pain on percussion (OR = 0.438; 95% CI, 0.339–0.566).

Conclusions

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic was associated with an increase in the number of nonsurgical root canal treatments. Some of the changes observed during the initial outbreak in 2020, including objective pain parameters, returned to normal levels 1 year later.

Key Words: Coronavirus disease 2019, endodontics, nonsurgical root canal treatment, pain, practice management

Significance.

The impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic on public dental health is unknown. This study shows that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 was associated with an increase in the number of nonsurgical root canal treatments. It also shows that some of the changes observed during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 returned to normal 1 year later.

The emergence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic1 , 2 initially resulted in nationwide lockdowns and disruption in dental health care services in countries around the world, including the United States. This period lasted ∼2.5 months, from March 16 to May 31, 2020. In a previous study on the characteristics of patients seen during the lockdown period, our group showed that the initial COVID-19 outbreak was associated with having younger patients who had higher levels of pain and received more primary root canal treatments and apicoectomies than in the same period 1 year before3.

After the initial outbreak period, most dental offices resumed their services, and there was a consensus that a gradual return to normalcy would ensue4. The assumption was that many of the changes in patient characteristics during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 were due to the nationwide lockdown and the lack of access to dental care. Therefore, the changes would reverse over time as dental offices reopened and with the advent of vaccination and more effective treatment of the disease. However, the change in the public's behavior toward dental care during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a multifactorial phenomenon. For example, the hesitancy among older patients to attend dental visits could have been partly associated with their higher risk of morbidity and mortality with COVID-19 infection5. Studies showed that worsened socioeconomic conditions led to an increase in dental pain and deterioration in dental health during the initial outbreak of COVID-196. Given the continued prevalence of disease and societal disruption, some of the factors associated with changes in patient characteristics during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 continued to be present in 2021. In addition, the emergence of new variants as well as vaccine hesitancy have caused and will likely continue to cause surges in the number of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map). Nevertheless, the fluctuating trends in COVID-19 case numbers (https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map), vaccinations (https://www.mayoclinic.org/coronavirus-covid-19/vaccine-tracker), and other societal responses in 2021 might have helped with the reversal of changes observed during the initial COVID-19 outbreak. There is a lack of data on how all these pandemic-related factors may have changed the endodontic patient characteristics and the practice of endodontists. Therefore, the aims of this observational study, which is a follow-up analysis on our previous study3, were to determine if endodontists' practice in early 2021 saw changes in patient demographic, diagnostic, and procedural characteristics compared with a similar prepandemic period in 2019 and to determine whether the changes reported during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 were reversed 1 year later in 2021.

Materials and Methods

The present study builds on the results of our previous study3. The study protocol was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, and received an IRB exempt approval (IRB 300006461). This observational study followed the guidelines for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology.

Study Population and Design

Data from all patient visits that took place in 2 private endodontic practices, Centreville Endodontics and Capitol Endodontics, during March 16 to May 31 in 2021 (ongoing COVID-19 pandemic), 2020 (initial COVID-19 outbreak), and 2019 (normal pre–COVID-19) were included in the present study. The 2 private practices are in the Northern Virginia and Washington DC area; are operated by the same team of endodontists and administrative and clinical staff; and serve a similar population of patients. The 2 practices stayed fully operational without any limitation for patients who needed endodontic care during the lockdown phase in 2020 and thereafter during the COVID-19 pandemic throughout 2021. The staffing in the practices was also stable with no changes throughout the periods studied.

When patients contacted the offices, the administrative staff filled out a “call sheet” during the phone call. They collected some patient demographic data, including sex, address, tooth number, and pain level. They used a 4-point verbal rating system (ie, no, mild, moderate, and severe) to determine patients' self-reported pain level. An electronic chart was created for each patient in a secure electronic record software program (PBS Endo Enterprise, Cedar Park, TX), and a copy of this call sheet was scanned and saved into the chart documents. After arrival at the clinic, the endodontists recorded the patients' chief complaint and performed a series of examinations on tooth/teeth associated with the chief complaint. These examinations included percussion, palpation, the bite test, thermal tests (cold and/or hot), periodontal probing, and mobility. The pain level on percussion and palpation was objectively recorded using the 4-point verbal rating system (no, mild, moderate, and severe). After the clinical examinations, the clinical staff took a periapical radiograph of the tooth using the XCP paralleling device (Dentsply Sirona, Charlotte, NC) and Carestream digital sensors (Carestream Dental, Atlanta, GA). Finally, a diagnosis was made, and treatment options were offered to the patient. After the treatment, the endodontist entered all diagnostic and procedural data into the patient's electronic chart.

Data Collection

For data collection, daily schedules were reviewed, and patients' electronic charts were accessed manually. The following 3 sets of data were collected for each patient visit as described previously3:

-

1.

Demographic data: age; sex; tooth type (molar, premolar, or anterior); self-reported pain level (using the 4-point verbal rating system); self-reported systemic diseases (diabetes, liver disease, and kidney disease); and the distance traveled to the office, which was the distance between the patient's residential zip code and the office zip code determined using Google Maps (Google, Mountain View, CA; https://www.google.com/maps)

-

2

.Diagnostic data: pain level (using the 4-point verbal rating system) on percussion and palpation, pulpal diagnosis, and periapical diagnosis

-

3.

Procedural data: the type of procedure (evaluation, nonsurgical root canal treatment, retreatment, apicoectomy, pulpotomy, or incision for drainage), the number of visits to complete nonsurgical root canal treatment or retreatment (multiple or single), and the type of restoration (permanent or temporary)

Finally, the number of patient visits per month was calculated.

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed in 2 stages: for the first aim, we analyzed patient visit characteristics in mid-March to the end of May 2021 (ongoing COVID-19 pandemic) with the same period in 2019 (normal pre–COVID-19), and for the second aim, a comparison of patient visit characteristics in the same periods in 2021 and 2020 (initial COVID-19 outbreak) was performed. At each stage, bivariate analyses and multivariable analyses were performed as detailed later.

Bivariate analyses were performed using 2 tests: the chi-square test for categoric data of demographics (sex, tooth type, and medical history), diagnoses, and procedures and logistic regression (each test only has 1 explanatory variable in the logistic regression with binary years being the response variable)7 for continuous data of age, distance from the office, and pain levels (converted to numeric data: no and mild = 0, moderate and severe = 1). A logarithmic scale for distance from the office was used because this made the data distributed normally. The outliers (>100 miles) were excluded.

Because a number of these variables may interact with one another and to control for potential confounders, multivariable analyses were performed for each aim separately. We used a multiple logistic regression model in which data from 2021 were the binary response variable, and all others were explanatory variables. Multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to compare 2021 with 2019 (aim 1) and to compare 2021 with 2020 (aim 2). The following variables were excluded from multiple logistic regression analyses: patients' self-reported pain levels due to the number of missing entries and incision for drainage, type of restoration, and single/multiple visits because they were related to a subgroup of patient visits (ie, those who received nonsurgical root canal treatment, retreatment, or pulpotomy) and not all patient visits.

All covariates were converted to binary variables in multiple logistic regression analyses. For categoric variables with multiple categories (ie, tooth type, pulpal diagnosis, periapical diagnosis, and procedure), 1 category was defined as a reference group as described previously3. Pain levels were converted to 0 or 1 for none to mild or moderate to severe, respectively. An “old” patient was defined as a patient who was older than the average age of the entire cohort of all 3 years (49.5 years). Patients who traveled more than the average distance in the entire cohort (12.6 miles) were defined as having traveled a “long distance.” These figures exclude the outliers of >100 miles. Analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) with the P value set at <.05.

Results

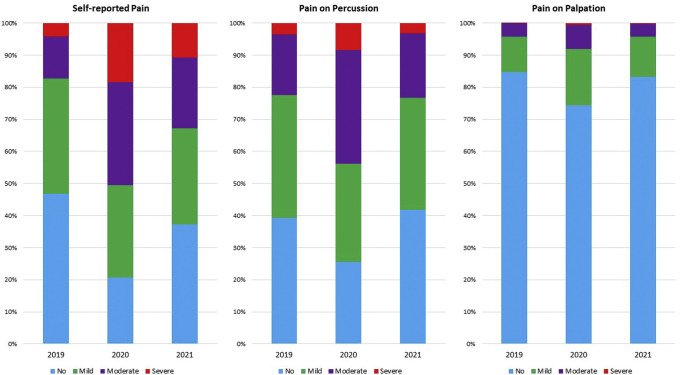

During the period between mid-March and the end of May (2019, 2020, and 2021), a total of 2657 patient visits took place in the 2 endodontics offices, and all were included in the analyses (1137 in 2021, 693 in 2020, and 827 in 2019). Patients' age ranged from 8–99 years (49.51 ± 16.59 years) in 2021, 7–94 years (48.21 ± 15.80 years) in 2020, and 7–92 years (50.66 ± 15.62 years) in 2019. Patients traveled 0.3–93.6 miles (12.83 ± 10.14 miles) in 2021, 0.70–81.60 miles (13.11 ± 10.52 miles) in 2020, and 0.70-77.80 miles (11.94 ± 9.897 miles) in 2019. These figures excluded those who traveled >100 miles (18 [1.5%] in 2021, 8 [1.1%] in 2020, and 5 [0.6%] in 2019). A proportional distribution of patient visits based on their subjective and objective pain levels is shown in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Proportional distribution of 2657 patient visits based on subjective and objective pain levels (no, mild, moderate, and severe) in 2019, 2020, and 2021. Self-reported pain, pain on percussion, and pain on palpation. The illustrations show how the proportion of moderate (purple) and severe (red) pain dramatically increased during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020. Although in 2021 the subjective pain levels (pain on percussion and palpation) returned to the norms of 2019, self-reported pain remained significantly higher than 2019. See Tables 2, 3, 5, and 6 for the details of the statistical analyses.

Comparison of the Ongoing Pandemic Year 2021 with Prepandemic Data from 2019

Bivariate analyses showed significant differences in few variables (Table 1 ). Patients reported higher levels of self-reported pain in 2021 (P < .05), but pain on percussion and palpation were not different than 2019 (P ≥ .05) (Table 2 ). There was a significant increase in the number of cases diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis and chronic apical abscess, and a significant decrease in the number of previously treated teeth (P < .05) (Table 1). Patient visits in which nonsurgical root canal treatment and apicoectomy were performed were significantly higher in 2021 (P < .05). Patients had more multiple-visit treatments and received more permanent restorations in 2021 (P < .05). The rest of the variables did not show differences (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19] Pandemic) with 2019 (Normal Pre–COVID-19)

| Variable | 2019, n (%) | 2021, n (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Sex | Female | 459 (56.25) | 633 (55.68) | .8167 | |

| Male | 357 (43.75) | 504 (44.32) | ||||

| Tooth type | Anterior | 93 (11.25) | 137 (12.05) | .5844 | ||

| Premolar | 148 (17.90) | 183 (16.09) | .2925 | |||

| Molar | 586 (70.85) | 817 (71.86) | .6291 | |||

| Diabetes∗ | 56 (6.88) | 67 (5.93) | .3958 | |||

| Liver disease∗ | 9 (1.11) | 6 (0.53) | .1531 | |||

| Kidney disease∗ | 9 (1.11) | 14 (1.24) | .7908 | |||

| Pulpal diagnosis | Normal pulp | 30 (3.66) | 57 (5.02) | .1502 | ||

| Reversible pulpitis | 14 (1.71) | 12 (1.06) | .2148 | |||

| Irreversible pulpitis | 251 (30.61) | 397 (34.86) | .0487† | |||

| Pulp necrosis | 186 (22.68) | 270 (23.77) | .5756 | |||

| Previously initiated | 24 (2.93) | 20 (1.76) | .0861 | |||

| Previously treated | 315 (38.41) | 381 (33.54) | .0262† | |||

| Periapical diagnosis | Normal periapex | 125 (15.28) | 205 (18.05) | .1076 | ||

| Symptomatic apical periodontitis | 479 (58.56) | 646 (56.78) | .4325 | |||

| Asymptomatic apical periodontitis | 147 (17.97) | 169 (14.88) | .0669 | |||

| Chronic apical abscess | 43 (5.26) | 85 (7.48) | .0498† | |||

| Acute apical abscess | 24 (2.93) | 32 (2.82) | .8784 | |||

| Procedure | Evaluation | 258 (31.2) | 281 (24.71) | .0015† | ||

| Root canal treatment | 381 (46.07) | 603 (53.03) | .0023† | |||

| Retreatment | 169 (20.44) | 203 (17.85) | .1495 | |||

| Apicoectomy | 18 (2.18) | 47 (4.13) | .0167† | |||

| Pulpotomy | 1 (0.12) | 3 (0.26) | .4879 | |||

| Incision for drainage‡ | 16 (2.9) | 36 (4.49) | .1180 | |||

| Restoration‡ | Temporary | 521 (94.55) | 704 (87.02) | <.00001† | ||

| Permanent | 30 (5.44) | 105 (12.97) | ||||

| Number of visits‡ | Single | 483 (87.65) | 657 (81.21) | .0015† | ||

| Multiple | 68 (12.34) | 152 (18.78) | ||||

Results of bivariate analyses on categoric data. Chi-square analyses for the association between each categoric variable and the COVID binary variable. For variables with more than 2 categories, the test was run for each category compared with the rest.

Categories with missing entries (13 in 2019 and 6 in 2021).

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

The total sample size was calculated as the total number of root canal treatments, retreatments, and pulpotomies (551 in 2019, 511 in 2020, and 809 in 2021).

Table 2.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19]) with 2019 (Normal Pre–COVID-19)

| Variable | Coefficient | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.1436 | .1176 | 0.866 | 0.724–1.037 |

| Distance from the office | 0.1603 | .0895 | 1.1174 | .976–1.412 |

| Self-report pain | .8494 | .0001∗ | 2.338 | 1.830–2.987 |

| Percussion pain | 0.0440 | .6895 | 1.045 | .842–1.297 |

| Palpation pain | 0.00725 | .9748 | 1.007 | .643–1.578 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Results of bivariate analyses on continuous data: logistic regression analyses on age, distance from the office, and pain. The COVID-19 pandemic was the binary response variable.

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that, compared with 2019, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic year 2021 was significantly associated with a decrease in the number of cases diagnosed with reversible pulpitis and previously initiated treatment, with an increase in the number of nonsurgical root canal treatments and apicoectomies (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19] Pandemic) with 2019 (Normal Pre–COVID-19)

| Variable | Coefficient | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older age | −0.1322 | .1796 | 0.876 | 0.722–1.063 |

| Female sex | −0.0433 | .6559 | 0.958 | 0.792–1.159 |

| Diabetes | −0.0989 | .6202 | 0.906 | 0.613–1.340 |

| Liver disease | −0.8712 | .1166 | 0.418 | 0.141–1.242 |

| Kidney disease | 0.1037 | .8198 | 1.109 | 0.455–2.707 |

| Distance from the office | 0.1151 | .2410 | 1.122 | 0.926–1.360 |

| Anterior tooth | 0.1861 | .3184 | 1.205 | 0.836–1.736 |

| Molar tooth | 0.1980 | .1262 | 1.219 | 0.946–1.571 |

| Percussion pain | 0.0523 | .6905 | 1.054 | 1.718–3.016 |

| Palpation pain | 0.0572 | .8418 | 1.059 | 0.604–1.856 |

| Reversible pulpitis | −0.9466 | .0423∗ | 0.388 | 0.156–0.968 |

| Irreversible pulpitis | −0.3435 | .2449 | 0.709 | 0.397–1.266 |

| Pulp necrosis | −0.4000 | .2067 | 0.670 | 0.360–1.247 |

| Previously initiated | −0.9549 | .0290∗ | 0.385 | 0.163–0.907 |

| Previously treated | −0.4848 | .1215 | 0.616 | 0.333–1.137 |

| Symptomatic apical periodontitis | −0.2668 | .1085 | 0.766 | 0.553–1.061 |

| Asymptomatic apical periodontitis | −0.2836 | .1704 | 0.753 | 0.502–1.130 |

| Chronic apical abscess | 0.2108 | .4141 | 1.235 | 0.744–2.048 |

| Acute apical abscess | −0.2871 | .4384 | 0.750 | 0.363–1.551 |

| Nonsurgical root canal treatment | 0.3931 | .0093∗ | 1.482 | 1.102–1.992 |

| Retreatment | 0.1950 | .2410 | 1.215 | 0.877–1.684 |

| Apicoectomy | 0.9791 | .0024∗ | 2.662 | 1.416–5.004 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Results of the multiple logistic regression analyses. COVID-19 is the binary response variable.

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

Comparison of the Ongoing Pandemic Year 2021 with the Initial Outbreak Period in 2020

This analysis was performed to determine if there were any changes in endodontic practice characteristics 1 year after the pandemic outbreak and after other dental offices resumed their practice. Bivariate analyses showed significant changes in several variables (Table 4 ). The number of patient visits for male patients increased in 2021 (P < .05). Pain levels in all 3 categories of self-report, percussion, and palpation were significantly less in 2021(P < .05) (Table 5 ). Patient visits associated with molar teeth increased in 2021 (P < .05), whereas visits associated with premolars decreased (P < .05). There were less visits for patients with kidney disease in 2021 (P < .05). There were more patient visits with a pulpal diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis and with periapical diagnoses of a normal periapex and asymptomatic apical periodontitis in 2021 (P < .05). There were also fewer patient visits with a pulpal diagnosis of pulp necrosis and periapical diagnosis of an acute apical abscess in 2021 (P < .05). Permanent restorations were placed less frequently in 2021, and patients received multiple-visit treatments more frequently (P < .05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19] Pandemic) with 2020 (Initial COVID-19 Outbreak)

| Variable | 2020, n (%) | 2021, n (%) | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Sex | Female | 422 (61.13) | 633 (55.68) | .0232∗ | |

| Male | 269 (38.87) | 504 (44.32) | ||||

| Tooth type | Anterior | 89 (12.84) | 137 (12.05) | .8191 | ||

| Premolar | 141 (20.34) | 183 (16.09) | .0208∗ | |||

| Molar | 463 (66.81) | 817 (71.86) | .0224∗ | |||

| Diabetes† | 54 (7.92) | 67 (5.93) | .1004 | |||

| Liver disease† | 2 (0.29) | 6 (0.53) | .4596 | |||

| Kidney disease† | 18 (2.60) | 14 (1.24) | .0283∗ | |||

| Pulpal diagnosis | Normal pulp | 28 (4.07) | 57 (5.02) | .3519 | ||

| Reversible pulpitis | 14 (2.03) | 12 (1.06) | .0875 | |||

| Irreversible pulpitis | 196 (28.63) | 397 (34.86) | .0059∗ | |||

| Pulp necrosis | 214 (31.1) | 270 (23.77) | .0006∗ | |||

| Previously initiated | 9 (1.31) | 20 (1.76) | .4540 | |||

| Previously treated | 226 (32.85) | 381 (33.54) | .7618 | |||

| Periapical diagnosis | Normal periapex | 95 (13.83) | 205 (18.05) | .0186∗ | ||

| Symptomatic apical periodontitis | 446 (64.92) | 646 (56.78) | .0006∗ | |||

| Asymptomatic apical periodontitis | 57 (8.30) | 169 (14.88) | .0001∗ | |||

| Chronic apical abscess | 45 (6.55) | 85 (7.48) | .4536 | |||

| Acute apical abscess | 44 (6.40) | 32 (2.82) | .0002∗ | |||

| Procedure | Evaluation | 156 (22.51) | 281 (24.71) | .2836 | ||

| Root canal treatment | 394 (56.85) | 603 (53.03) | .1115 | |||

| Retreatment | 116 (16.74) | 203 (17.85) | .5419 | |||

| Apicoectomy | 26 (3.75) | 47 (4.13) | .6855 | |||

| Pulpotomy | 1 (0.14) | 3 (0.26) | .5953 | |||

| Incision for drainage‡ | 33 (6.45) | 36 (4.49) | .1416 | |||

| Restoration‡ | Temporary | 307 (60.07) | 704 (87.02) | <.00001∗ | ||

| Permanent | 204 (39.92) | 105 (12.97) | ||||

| Number of visits‡ | Single | 439 (85.9) | 657 (81.21) | .0267∗ | ||

| Multiple | 72 (14.09) | 152 (18.78) | ||||

Results of bivariate analyses on categoric data: chi-square analyses for the association between each categoric variable and the COVID binary variable. For variables with more than 2 categories, the test was run for each category compared with the rest.

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

Categories with missing entries (11 in 2020 and 6 in 2021).

The total sample size was calculated as the total number of root canal treatments, retreatments, and pulpotomies (551 in 2019, 511 in 2020, and 809 in 2021).

Table 5.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19] Pandemic) with 2020 (Initial COVID-19 Outbreak)

| Variable | Coefficient | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.1403 | .1459 | 1.151 | .952–1.390 |

| Distance from the office | −1.677 | .0857 | 0.846 | .698–1.024 |

| Self-report pain | −.736 | .0001∗ | .479 | .391–.587 |

| Percussion pain | −.9444 | .0001∗ | .389 | .317–.478 |

| Palpation pain | −.6697 | .0011∗ | .512 | .343–.764 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Results of bivariate analyses: logistic regression analyses on age, distance from the office, and pain. COVID-19 was the binary response variable.

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

Multiple logistic regression analyses showed that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic year 2021 was significantly associated with older patients, less females, a higher number of molars, and less pain on percussion compared with the period of outbreak in 2020 (Table 6 ).

Table 6.

Comparison of 2021 (Ongoing Coronavirus Disease 2019 [COVID-19] Pandemic) with 2020 (Initial COVID-19 Outbreak)

| Variable | Coefficient | P value | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older age | 0.2531 | .0176∗ | 1.288 | 1.045–1.588 |

| Female sex | −0.2473 | .0192∗ | .781 | 0.635–.960 |

| Diabetes | −0.3602 | .0802 | 0.698 | 0.466–1.044 |

| Liver disease | 2.0785 | .0879 | 7.992 | 0.735–86.944 |

| Kidney disease | −1.0077 | .0112 | .365 | 0.168–0.796 |

| Distance from the office | −0.0914 | .3792 | 0.913 | 0.744–1.119 |

| Anterior tooth | 0.0814 | .6742 | 1.085 | 0.742–1.586 |

| Molar tooth | 0.3285 | .0153∗ | 1.389 | 1.065–1.811 |

| Percussion pain | −0.8250 | .0001∗ | 0.438 | 0.339–0.566 |

| Palpation Pain | 0.1831 | .4698 | 1.201 | 0.731–1.973 |

| Reversible pulpitis | −1.1147 | .0177∗ | 0.328 | 0.131–0.824 |

| Irreversible pulpitis | 0.2356 | .4392 | 1.266 | 0.697–2.299 |

| Pulp necrosis | −0.0875 | .7861 | 0.916 | 0.487–1.724 |

| Previously initiated | 0.5590 | .2909 | 1.749 | 0.620–4.934 |

| Previously treated | −0.4529 | .1661 | 0.636 | 0.335–1.207 |

| Symptomatic apical periodontitis | −0.0653 | .7248 | 0.937 | 0.651–1.347 |

| Asymptomatic apical periodontitis | 0.4341 | .0743 | 1.544 | 0.958–2.486 |

| Chronic apical abscess | 0.0531 | .8417 | 1.055 | 0.626–1.775 |

| Acute apical abscess | −0.3127 | .3555 | 0.731 | 0.377–1.420 |

| Nonsurgical root canal treatment | −0.3009 | .0946 | 0.740 | 0.520–1.053 |

| Retreatment | −0.3009 | .0946 | 1.215 | 0.829–1.781 |

| Apicoectomy | −0.0707 | .8103 | 0.932 | 0.523–1.660 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Significant difference at P < .05 (highlighted in bold).

Discussion

Most research studies published after the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic focused on changes in practices and patient characteristics during the outbreak8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14. There is a lack of data regarding if and how these changes returned to normal after the outbreak. As far as we are aware, the present study is the first analysis of the longer-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on characteristics of patients in need of endodontic treatments. The current study shows that some changes that took place during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 returned to normal 1 year later in 2021, and some did not. It reveals how the COVID-19 pandemic may create ongoing changes in the characteristics of patients seen in endodontic specialists' practices.

Overall, the number of patient visits to the 2 offices decreased by 16% during the initial outbreak of the pandemic but increased by 38% a year later compared with 2019 numbers. This shows a reasonable rebound in patient flow, similar to trends reported in other areas of dentistry4. Future studies should clarify how the patient flow has been affected by subsequent surges in COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths due to the emergence of more transmissible variants and vaccine hesitancy.

In our previous study3, we showed that the initial COVID-19 outbreak was associated with increased patients' self-reported pain, pain on percussion, and pain on palpation. The present investigation showed that in 2021 the presence of pain on percussion and palpation returned to prepandemic 2019 levels. Percussion pain significantly decreased in 2021 compared with 2020. However, self-reported pain levels in 2021 stayed significantly higher than the norms of 2019. These findings may be due to patients' continued hesitancy to visit a dentist15 until the pain becomes significant coupled with the improved availability of general dental offices to address at least some of the acute dental pain. It is worth noting that the spike in the number of visits associated with acute apical abscesses that took place during the initial outbreak in 2020 returned to normal levels in 2021. In other words, patients do not wait too long to face the most severe consequences of pulpal pathosis (ie, acute apical abscesses).

Previous studies showed that the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in a substantial decrease in procedure volume for patients covered by public insurances in the United States16. There are other socioeconomic factors that could contribute to patients' behavior in this regard. A study by Matsuyama et al6 showed that dental pain was associated with household income reduction, work reduction, and job loss during the outbreak of COVID-19. These worsened socioeconomic conditions continued beyond the lockdown period for millions of households in the United States. More clinical studies on different populations in different geographic areas and different settings are needed to assess and compare the pain levels of endodontic patients before and after the COVID-19 pandemic and to investigate other related factors.

Our previous study revealed that the odds for performing nonsurgical root canal treatments significantly increased during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in 20203. The present study showed that the same trend continued in 2021, and it did not return to the norms of 2019. This is an important finding that implies that the public's need for nonsurgical root canal treatment has increased. Also, it is worth noting that nonsurgical root canal treatments constitute most of the emergency visits in endodontic offices. Therefore, our findings indirectly show that the trend of more emergency visits in 2020 compared with 2019 has persisted into 2021. This is consistent with the persistent increase in the level of self-reported pain among patients.

We observed a significant increase in the number of visits with the diagnosis of irreversible pulpitis and a significant decline in the number of visits with the diagnosis of previously treated in 2021 compared with 2019. This finding is a key contributing factor to the increased likelihood of nonsurgical root canal treatments but not nonsurgical retreatments in 2021. The shift in the public's attitude toward their dental health, pain being the motive for dental visits, might be 1 of the factors that has led to this change. Taken together, these findings may indicate that despite the return of general dentists to full-time practice, they were less likely to perform emergency or definitive nonsurgical root canal treatment, perhaps related to busyness with other dental procedures. Another aspect related to this finding that is yet to be studied is the etiologies of pulpal pathosis related to these patient visits. An investigation on the etiology of pulpal disease before and after the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially explain the reasons behind the trend for more nonsurgical root canal treatments after COVID-19 pandemic.

The present study shows that some of the changes observed during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in 2020 returned to normal levels in 2021. The patients seen during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 were significantly younger than those seen during the similar period in 2019. This trend returned to normal in 2021. The previous study showed a significant rise in the number of visits for patients with kidney disease during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 20203. This patient condition also returned to normal in 2021. The number of visits for patients with diabetes and liver disease were not different in 2021 compared with 2019. Clinical studies showed that the risk of hospitalization and the severity of symptoms increase in COVID-19 patients with comorbidities like diabetes, renal disease, and liver disease5 , 17. Therefore, the expectation was to see a persistent decline in the number of visits by these patients due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in 2021. However, these patients had a similar number of visits in 2021 compared with 2019. These are positive findings showing that older patients and patients with systemic diseases are pursuing their dental treatments at a comparable level to prepandemic. This finding may indicate that the overall fear and hesitancy about dental visits among these patients are less than that seen during the period of the initial outbreak, specifically among older patients. Vaccinations, the effectiveness of preventative measures such as masking and social distancing, and the availability of more effective treatment strategies for COVID-19 may all play a role in this finding.

We observed procedural changes during the initial outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 that seemed to be related to changes in operators', patients', and referring dentists' preferences. These procedural changes included an increased number of apicoectomies performed, an increased number of permanent fillings placed, and a reduced number of visits with a diagnosis of previously initiated therapy3. These trends persisted into 2021. Also, even though the number of cases in which patients received permanent fillings was reduced in 2021 compared with 2020 (probably because the general dentists were available to restore these teeth), the patients still received significantly more permanent fillings in 2021 compared with 2019. Patients', operators', and referring dentists' preferences in limiting the number of patient visits could be a factor associated with these changes. The present study showed a significant rise in the percentage of molar cases in 2021 compared with 2020. It may be that general dentists are treating more anterior teeth and premolars in their practice now that they are available.

The present study showed a significant decline in the number of visits for female patients. The reasons for this change in sex distribution are not clear. Other similar studies are needed to determine if these findings are consistent. The sex-specific impacts of socioeconomic fluctuations due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the sex-specific changes in the public's behavior toward their dental health have not been adequately studied. However, it is generally known that the pandemic has affected women in the workforce more than men. It is worth noting that the data from this study are limited to 2 endodontist offices located in the Washington DC and Northern Virginia area. More clinical studies are recommended to determine the sex-specific changes of patients' attitudes toward their dental health around the nation.

Acknowledgments

The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this study.

References

- 1.Wang C., Horby P.W., Hayden F.G., Gao G.F. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet. 2020;395:470–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ather A., Patel B., Ruparel N.B., et al. Coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19): implications for clinical dental care. J Endod. 2020;46:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nosrat A., Dianat O., Verma P., et al. Endodontics specialists' practice during the initial outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. J Endod. 2022;48:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2021.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kranz A.M., Chen A., Gahlon G., Stein B.D. 2020 trends in dental office visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:535–541.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta H.B., Li S., Goodwin J.S. Risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infections, hospitalization, and mortality among US nursing home residents. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e216315. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuyama Y., Aida J., Takeuchi K., et al. Dental pain and worsened socioeconomic conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Dent Res. 2021;100:591–598. doi: 10.1177/00220345211005782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ananth C.V., Preisser J.S. Bivariate logistic regression: modelling the association of small for gestational age births in twin gestations. Stat Med. 1999;18:2011–2023. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990815)18:15<2011::aid-sim169>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weintraub J.A., Quinonez R.B., Smith A.J., et al. Responding to a pandemic: development of the Carolina Dentistry Virtual Oral Health Care Helpline. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151:825–834. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu J., Hua F., Shen Y., et al. Resumption of endodontic practices in COVID-19 hardest-hit area of China: a web-based survey. J Endod. 2020;46:1577–1583.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salgarello S., Salvadori M., Mazzoleni F., et al. Urgent dental care during Italian lockdown: a cross-sectional survey. J Endod. 2021;47:204–214. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu J., Zhang T., Zhao D., et al. Characteristics of endodontic emergencies during coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Wuhan. J Endod. 2020;46:730–735. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beauquis J., Petit A.E., Michaux V., et al. Dental emergencies management in COVID-19 pandemic peak: a cohort study. J Dent Res. 2021;100:352–360. doi: 10.1177/0022034521990314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langella J., Magnuson B., Finkelman M.D., Amato R. Clinical response to COVID-19 and utilization of an emergency dental clinic in an academic institution. J Endod. 2021;47:566–571. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinho F.C., Griffin I.L. A cross-sectional survey on the impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on the clinical practice of endodontists across the United States. J Endod. 2021;47:28–38. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paszynska E., Cofta S., Hernik A., et al. Self-reported dietary choices and oral health care needs during COVID-19 quarantine: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients. 2022;14:313. doi: 10.3390/nu14020313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi S.E., Simon L., Basu S., Barrow J.R. Changes in dental care use patterns due to COVID-19 among insured patients in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152:1033–1043.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2021.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett T.D., Moffitt R.A., Hajagos J.G., et al. Clinical characterization and prediction of clinical severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection among US adults using data from the US National COVID Cohort Collaborative. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2116901. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]