Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is a major cause of death worldwide, with 1.5 million deaths in 2020. While TB incidence and mortality had previously been on a downwards trend, in 2020, TB mortality actually rose for the first time in a decade, largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Undernutrition is the leading risk factor for TB, with a population attributable fraction (PAF) of 15%, compared to 7.6% for HIV. Individuals who are undernourished are more likely to develop active TB compared to those with a healthy bodyweight. They are also more likely to have greater severity of TB, and less likely to have successful TB treatment outcomes. The likelihood of TB mortality significantly increases as weight decreases. Nutritional interventions are likely to improve both nutritional status and TB treatment success, thereby decreasing TB mortality. However, many previous studies focusing on nutritional interventions have provided insufficient calories or been underpowered. Nutritional supplementation will be particularly important as factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and political conflict further threaten food security. The global TB elimination effort can no longer afford to ignore undernutrition.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Undernutrition, BMI, Nutritional interventions

1. Introduction

The End TB Strategy aims to reduce tuberculosis (TB) incidence by 80% and TB mortality by 90% by 2030, but this approach is not meeting its milestones [1]. Despite a goal of reduction in TB incidence of 20% between 2015 and 2020, TB incidence only fell by 11% [2]. Moreover, while TB incidence and mortality had been on a downwards trend worldwide, in 2020, TB mortality actually rose from 1.4 million to 1.5 million deaths- the first increase in 10 years, likely due to factors associated with the COVID-19 pandemic [3]. Funding for TB also decreased in 2020, with an 8.7% decline in spending compared to 2019 [2].

While substantial progress has been made in the field of TB care in recent years, investments are dominated by direct costs of diagnosis and treatment as well as research on novel tests and treatments [4]. Although these are critical investments in reducing global mortality and morbidity related to TB, focusing research funds on innovations in testing and treatment risks ignoring one of the key accelerants of the TB pandemic: undernutrition.

2. Metrics for undernutrition

Macronutrient and micronutrient deficiency both play key roles in the immune response against TB [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Nutritional assessments can be performed using diverse methods including food intake assessments from food frequency questionnaires or dietary recalls; body composition measurements using anthropometry or bioelectric impedance; or biochemical measurement of specific nutrients [11]. However, the most common metric for defining undernutrition in the TB literature is the body mass index (BMI) (unit: weight in kilogram/height in meters2) due to its ease of measurement. BMI in the 17–18.5 kg/m2 range corresponds to mild undernutrition, a BMI of 16–16.9 kg/m2 represents moderate undernutrition, and BMI < 16 kg/m2 represents severe undernutrition [12]. BMI does not provide information regarding specific nutrient deficiencies; however, individuals with low BMIs frequently have both macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies.

3. A history of nutrition and TB

Historical events have shown the impact of undernutrition on TB incidence and mortality. Prior to the mid-1800s, TB was the leading cause of death in Europe and the United States [13]. Robert Koch would not discover Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the infectious agent that caused TB until 1882 [13] and the first effective TB drug, streptomycin, was not developed until 1944 [14]. However, the greatest decline in TB mortality occurred in the mid-1800s to mid-1900s, prior to the development of antimycobacterials or the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine [15]. Physician and historian Thomas McKeown posited that the decreased TB incidence and mortality in the pre-antimycobacterial era was largely a product of socioeconomic progress, which included better living conditions and increased nutrition [16].

Several examples that illustrate this concept have been observed in the past century [17]. In the Papworth Village Settlement in England, a social experiment played out between 1918 and 1943 [18]. After being discharged from a sanitorium, TB patients were provided with employment, nutritional supplementation, and medical monitoring. There was a dramatic decrease in TB disease incidence among children under 5 years of age who were born within the Papworth settlement as compared to the rate prevailing at the time in England: 0 cases vs 1,217 cases per 100,000 person-years. These striking results demonstrated the benefits of social protections, including nutritional interventions, on decreasing TB rates [18].

In 1939, before the start of the Second World War, TB mortality in Amsterdam was approximately 35 per 100,000 (Fig. 1 [19]). The German army invaded the Netherlands in 1940. They left TB services relatively unaffected and even introduced pasteurization of milk, but food availability and quality declined during the occupation [20]. In addition to increased undernutrition, factors such as cramped living conditions and a transition to home treatment of TB (because of shortages in sanatorium beds) led to a doubling of TB mortality to 75 per 100,000 by 1943 [19]. From September-November 1944, the German army blocked road and water routes, which led to disruption of TB clinic services as well as an acute shortage of food and fuel, particularly in Dutch cities [20]. The average adult caloric intake dropped to approximately 1000 Kcal/day by November 1944 and further declined to 580 Kcal/day by February 1945, despite the end of the German embargo and airdrop of rations from the allied forces [21]. In this period, called the hunger winter, many Dutch citizens resorted to eating grass, sugar beets, and tulip bulbs to survive, and there were 91,000 excess deaths, including deaths from starvation, TB, and other causes [22]. In addition to deaths directly due to starvation, there was a sharp rise in TB mortality, which, in Amsterdam, rose to 85 per 100,000 in 1944 and peaked at 105 per 100,000 in 1945 before rapidly declining in 1946 and returning to pre-war levels by 1947 [20].

Fig. 1.

Tuberculosis mortality in Amsterdam during World War II. Data derived from Daniels, 1949 [19].

The effects of starvation on TB were also evident from a study of Russian and British prisoners of war held captive in Germany. All prisoners had similarly harsh living conditions and were provided with 1600 calories a day, with minimal animal protein, and were required to perform heavy labor. However, the British prisoners received an additional 1,300 calories a day from the Red Cross, including 45.5 additional grams of animal protein. The Russian prisoners of war experienced a 13-fold increased incidence of TB compared to the British prisoners [23].

4. Undernutrition and TB incidence and severity

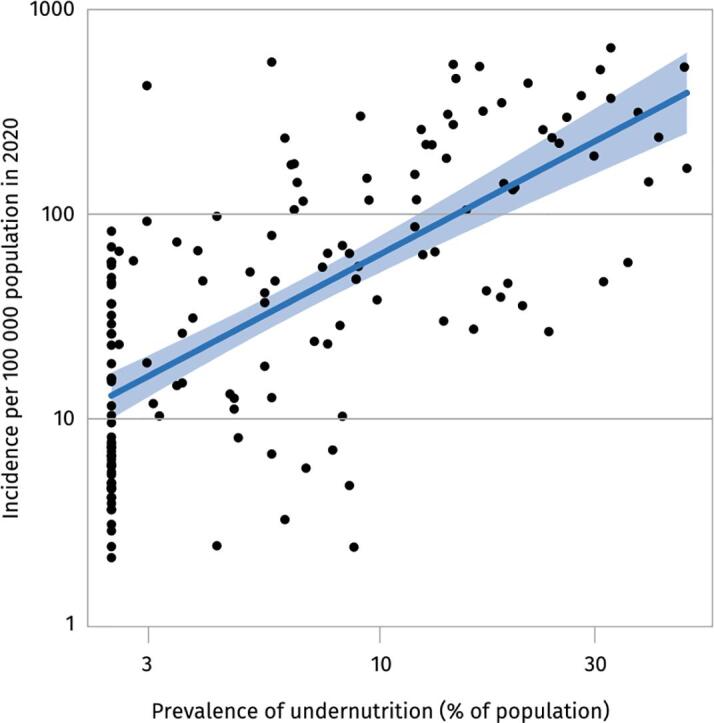

As reviewed previously, numerous animal studies have shown that undernutrition blunts the adaptive and innate immune response to TB [8], [24]. In fact, undernutrition is the leading cause of secondary immunodeficiency worldwide and has even been described as “nutritionally-acquired immunodeficiency (N-AIDS)” [25], [26]. Today, undernutrition is the leading risk factor for TB, with a population-attributable fraction (PAF) of 15%, compared to 7.6% for HIV and 3.1% for diabetes [4]. The PAF of undernutrition for TB is particularly substantial in countries with the highest burdens of TB. For instance, in India, which has a quarter of the global TB burden, over half of all TB cases were attributable to undernutrition in most states [27]. According to a systematic review, comprising 2.6 million patients, there exists a consistent log-linear relationship between pre-morbid BMI and TB incidence [28]. For every 1 kg/m2 increase in BMI, TB incidence is reduced by 13.8% (95% confidence interval 13.4–14.2) [28]. Similarly, as seen in Fig. 2, TB incidence has been shown to increase with rising prevalence of undernutrition in a population.

Fig. 2.

Relationship between TB incidence and prevalence adapted with permission from Global Tuberculosis Report 2021 (license: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) [4].

5. TB Treatment success and mortality

Undernourished individuals are also more likely to have greater severity of TB. A 2019 study in India found that patients who were severely undernourished had 11% more of their lungs affected on chest X-ray (95% CI: 4.0–13.3) [29]. Those who were severely undernourished were also significantly more likely to have lung cavitation (a rate of 4.6 times more; 95% CI, 1.5–14.1) compared to those with a normal BMI. A study in Latvia of 995 MDR-TB patients found that those who were underweight were significantly more likely to be both smear and culture positive compared to patients with a normal body weight (OR 2.2 for both) [30].

Undernutrition also decreases TB treatment success. A Peruvian study found that patients with unsuccessful treatment outcomes were twice as likely not to have gained greater than 5% of their baseline weight at the end of treatment compared to those with successful outcomes (risk ratio [RR] 2.05; 95% CI 1.10–3.80) [31]. In Brazil, researchers found that for every 1 kg increase in weight in the first two months, likelihood of unsuccessful treatment outcomes decreased by 12% [32]. Furthermore, in a 2005 study, patients who were underweight at time of diagnosis (defined as being 10% or more below ideal body weight) had a 19.1% chance of relapse, compared to only a 4.8% likelihood of relapse among those who were not underweight when diagnosed with TB (p < 0.001) [33]. Those who gained 5% or less of their bodyweight over the course of treatment were also significantly more likely to relapse than those who gained more than 5% bodyweight (odds ratio [OR] 2.4; p = 0.03). A nested case-control study in Yemen found that, after adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, disease severity, treatment adherence, and medical comorbidities, persons with TB who had a BMI of ≤18.5 kg/m2 were 3.1 times more likely to relapse compared to patients with a BMI of 18.5 kg/m2 or greater (95% CI 1.6–6.2) [34].

In addition to increasing TB severity and chance of relapse, undernutrition also increases the likelihood of TB mortality. A 2014 study in Ethiopia found that patients who weighed less than 35 kg had a 3.9 times higher rate of death than patients who weighed 35 kg or more [35]. A South African study found that for every kg decrease in weight at the start of treatment, odds of survival decreased by 7.5% (P < 0.01) among those with extensively drug-resistant TB [36]. Similar results were found in Malawi, where 10.9% of patients with moderate (BMI 16.0–16.9 kg/m2) to severe undernutrition (BMI < 15.9 kg/m2) died in the first four weeks of treatment, compared to only 6.5% of patients with either no undernutrition (BMI greater than 18.5 kg/m2) or mild undernutrition (BMI 17.0–18.5 kg/m2), OR 1.8 (95% CI 1.1–2.7) [37].

Undernutrition likely increases severity and worsens treatment outcomes through numerous mechanisms. Chief among them is likely the impact of undernutrition on the Th1 responses and reduction in regulatory T-cell signaling that result in a delayed and unregulated immune response [8]. Undernutrition may also blunt pharmacotherapy through decreased absorption of key antitubercular medicines such as Rifampin and Isoniazid [38], [39]. Paradoxically, decreased fat-free mass among undernourished persons may also result in supratherapeutic levels of drugs like aminoglycosides and ethambutol with increased toxicity [40].

6. The bidirectional relationship between TB and nutrition

One major limitation of observational studies of undernutrition and TB is the bidirectional relationship between these two conditions. Weight loss is a cardinal symptom of TB, and as such, some have expressed concerns that undernutrition is largely an effect of TB rather than a cause of it. However, some studies have been able to account for this concern. For instance, a 2012 study used premorbid BMI data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) between 1971 and 1992 to assess risk factors related to developing TB [41]. The researchers found that TB incidence among adults with normal BMI was 24.7 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 13.0, 36.3), compared to 260.2 per 100,000 person-years for those with BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 (95% CI: 98.6, 421.8), adjusted hazard ratio (HR): 12.43 (95% CI: 5.75, 26.95). This study also noted that obesity was protective against TB incidence, HR: 0.28 (95% CI: 0.13, 0.63). A study in Hong Kong corroborated that obese and overweight elderly individuals were significantly less likely to develop TB disease compared to those with a normal body weight: HR 0.36 (95% CI 0.20–0.66) for obese individuals and HR 0.55 (95% CI 0.44–0.70) for overweight individuals [42].

More recently, a case control study nested in a prospective cohort has suggested that there is an increased risk of TB incidence in the setting of vitamin deficiencies. The researchers found that vitamin A deficiency in household contacts (HHCs) of pulmonary TB cases was associated with a ten times greater increase in progression to active TB (OR 10.53, 95% CI 3.73–29.70) [9], while vitamin E deficiency was associated with a nearly two times greater increase in progression to active TB (OR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.18, 2.92) [10]. Another study has shown that vitamin D deficiency was associated with a five times greater increase in progression from latent to active TB (adjusted RR 5.1; 95% CI 1.2, 21.3, p = 0.03) [43].

Unpublished data from a multicenter study in India show increased risk of TB treatment failure (a composite of clinical failure, bacteriologic failure, death, relapse/recurrence) in persons who were severely undernourished (BMI < 16). This study adjusted for disease duration and conducted a sensitivity analysis to account for weight loss that may have been due to TB. The association between undernutrition and poor TB treatment outcomes remained unchanged even when the authors accounted for weight lost due to TB by conducting sensitivity analyses to estimate premorbid BMI [44].

7. Effect of nutritional interventions

Despite these historical data, studies focusing on providing nutritional supplementation to persons living with TB have had mixed results. A 2009 study in Timor-Leste found that an intervention group receiving a daily meal for eight weeks, followed by a food package for 14 weeks, had no significant difference in treatment completion compared to a control group [45]. Similarly, a 2011 study in Tamil Nadu, India found that TB patients who received a nutritional intervention of a cereal-lentil mixture and a multivitamin had no significant increase in treatment success compared to a control group [46]. Micronutrient supplementation, such as through multivitamins or supplements such as vitamin A, has also been found in several studies not to decrease TB incidence or improve treatment success [47], [48].

However, other studies have found that nutritional supplementation can decrease TB incidence and improve treatment success. A study in Brazil found that patients who received a monthly food basket alongside the typical treatment regimen had a cure rate of 87.1%, compared to a cure rate of only 69.7% for those who did not receive food baskets [49]. Similarly, an India-based study found that an intervention group who received a monthly supply of rice and lentils had a 9% rate of unsuccessful treatment, compared to 21% for those who did not receive the nutritional intervention (p < 0.001) [50].

A Cochrane systematic review included only six studies assessing the impact of macronutrient supplementation on treatment outcomes, weight gain, and quality of life. Overall, the systematic review found no evidence for earlier sputum clearance (relative effect, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.86–1.37) and low-grade evidence for improvement in quality of life through macronutrient supplementation [51]. The studies included in the Cochrane review were small and underpowered. Moreover, most of the studies did not track caloric intake and none appear to have attained a recommended daily dietary intake of 2500 kcal/day. As such, it is likely that the mixed results reported were a consequence of inadequate supplementation. Well-powered studies with adequate supplementation and close monitoring of caloric intake are needed to properly understand the clinical impact of nutritional supplementation.

Two upcoming studies from India will shed greater light on the impact of robust nutritional supplementation on TB incidence among household contacts as well as TB treatment outcomes among those with TB [52], [53]. These studies aim to address potential reasons for lack of success in previous nutritional interventions, which include the studies being underpowered, providing insufficient or inadequate interventions, and poor accounting of caloric intake.

In addition to the direct, biological benefits of food provision on nutritional status and the immune system, nutritional interventions can also increase adherence to TB treatment, as previously reviewed [54]. Treatment for TB typically involves six months of a grueling drug regimen, with nonadherence rates ranging from 20% to 50% [55], [56], [57]. Patients who do not complete treatment, or who do not take medication regularly, are more likely to have negative treatment outcomes, so encouraging treatment adherence should be a major goal [58]. The aforementioned food basket study in Brazil saw a nonadherence rate of 12.9% for those receiving the baskets, compared to 30.3% for those who did not [49]. Providing food to individuals when they attend medical visits could encourage increased adherence rates by providing a secondary reason for patients to attend their medical visit.

An oft-cited opposition to nutritional programs is that they are too expensive. This narrative is countered by a recent modeling study that examined providing free, in-kind nutritional supplementation to undernourished persons through an existing government ration program in India. The study found that providing rations sufficient for a 2600Kcal/d diet would be highly cost-effective (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio: $470/DALY averted) in precipitating an 81% reduction in TB incidence and 88% reduction in TB mortality over 5 years [59].

8. Looking towards the future

Reducing undernutrition may result in meaningful reductions in the TB epidemic. A 2015 modeling study found that even modest decreases in the prevalence of undernutrition would result in a reduction of 4.8 million TB cases and 1.6 million TB-related deaths over 20 years in India [60]. Another model in 2014 suggested a 23% reduction in prevalence in Southeast Asia by 2035 with the mitigation of undernutrition as compared to a do-nothing scenario [61]. Taking action to reduce undernutrition is more essential now than ever as food security worldwide is threatened by the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, and political conflict.

8.1. Tuberculosis and COVID-19

Preliminary studies have found that COVID-19 led to a substantial increase in food insecurity worldwide, with the greatest burden falling on high-TB countries [62]. A 2020 paper suggested that COVID-19 lockdowns and long-term effects of the pandemic would affect the “four pillars” of food security: availability, access, stability, and utilization [63]. A report from the United Nations projected that around 118 million more people worldwide experienced hunger in 2020 than in 2019 [62]. This food insecurity was largely due to a decreased ability to work. A 2021 study in Kenya and Uganda found that 70% of respondents reported decreased income during the initial period of COVID-19 [64]. In countries such as India, where strict lockdowns were imposed, many vulnerable households were unable to leave their homes or go to work [65]. A preliminary study from Tamil Nadu, India found that every household surveyed- all of whom had at least one member living with active TB- reported decreased incomes and difficulties purchasing food during the strictest stage of the coronavirus lockdowns [44]. The impacts of COVID-19 on food security are likely to be long-lasting and may compound anticipated increases in TB incidence and mortality due to diversion of funding, decreased case finding, and delayed treatment due to the COVID-19 pandemic [66].

8.2. Tuberculosis and climate change

Climate change greatly threatens food security [67]. The production of wheat and rice is projected to decrease with rising temperatures [68]. Intrusion of salty water after cyclones, which are projected to increase in severity with rising global temperatures, threatens arable land in coastal regions [69]. Changes in rainfall patterns may also impact food production in countries like India which are extremely reliant on rains for irrigation, with 15–40% of rainfed rice-growing areas at risk of becoming less suitable or completely unsuitable for rice production [70]. In addition to availability issues, access to food may also be threatened by extreme weather events related to climate change [71]. For instance, in 2020, vegetable prices rose 20–30% in the aftermath of cyclone Amphan in Southern India due to disrupted supply chains [72]. Such price shocks could result in acute undernutrition and translate into increased TB incidence and mortality as was seen during the hunger winter.

8.3. Tuberculosis and political conflict

Politics and social conflict also threaten food security. In Venezuela, with political upheaval and disruption to the social safety net, TB has seen a major increase in recent years, likely attributable to massive food shortages [73]. Increased rates of poverty are also leading to multiple families living in single homes, providing additional opportunities for TB to spread. The Venezuelan government is not releasing health statistics, making it difficult to assess the true burden of disease, but two Caracas TB centers have seen a 40% increase in TB patients [73]. Political conflict can also cause an increase in forced migration with associated food insecurity. Colombian provinces with high numbers of Venezuelan migrants have seen an increased incidence in TB in recent years as migrants flee political turmoil in Venezuela [74]. As noted previously, it is difficult to separate the effect of undernutrition from that of socioeconomic determinants and a deterioration in public health infrastructure. However, based on previously presented epidemiologic and historical data, the effect of acute undernutrition during political conflict may be meaningful. Even as we write this paper, war in Ukraine is generating a refugee crisis of massive proportions which threatens TB elimination in both Ukraine and surrounding countries.

9. Conclusions

In this perspective piece, we have presented compelling evidence from epidemiological studies in both the global North and South that supports the view that undernutrition is a key risk factor for TB and a driver of poor outcomes. Although the evidence presented largely pertains to adults, there is a body of evidence that shows a similar effect of undernutrition on TB incidence and mortality among children [38], [75], [76]. Given what we already know, we should not be asking if we need to address undernutrition to eliminate TB; we must instead ask what should be done and how.

Both lack of knowledge and lack of political will may contribute towards why undernutrition is ignored as an integral part of TB programming, so strategies should be adopted to improve both these areas. The WHO produced a guidance document on undernutrition in persons with TB and identified priority areas for basic, clinical, and health systems research [77]. However, we have not seen screening and care for undernutrition among persons with TB be integrated into standard TB care as was done for other key comorbidities such as HIV and diabetes.

With a few exceptions, such as India’s Nikshay Poshan Yojana, most high TB burden countries have not integrated screening and treatment for undernutrition as a part of standard TB care [78]. Currently, nutritional interventions are largely taking place in the form of small pilot studies rather than coordinated, large-scale programs based on extensive research [77].

While many may consider the evidence we present and then decide to implement large nutritional programs to reduce TB incidence and mortality, we believe that such action may not constitute the best utilization of resources. Some critical questions around nutritional supplementation remain unanswered: what is the optimal diet for persons with TB? What diet should be provided to pregnant mothers with TB? Are prepared foods more effective than raw ingredients? Should food be provided during clinic visits? How can we improve the nutritional status of the community to decrease TB risk? Perhaps the best way forward is for hybrid trials that seek to answer such questions while also asking and answering implementation questions that will expedite policy change.

The scientific and development communities need to take coordinated action exigently. We propose the following priorities: (1) integrating nutritional assessment and care into standard TB care; (2) improving nutrition on a population level to reduce TB incidence; and (3) increasing funding for undernutrition-TB research to address critical knowledge gaps previously identified by the WHO [8]. To catalyze action, we suggest convening a high-level meeting of experts in nutrition and experts in TB with the dual purpose of determining tangible next steps and promoting coordinated action. As undernutrition is a cross-cutting issue that has an impact on myriad health issues beyond TB, input by experts from a variety of sectors and regions would increase the ability to make definitive recommendations on required interventions. The WHO could lead the creation of a working group on nutrition and TB to further develop actionable steps.

Addressing undernutrition would bolster pillars 1 and 2 of the End TB Strategy [1], and would also help attain numerous sustainable development goals (SDG): SDG1 (no poverty), SDG2 (zero hunger), SDG3 (good health and well-being), SDG8 (decent work and economic growth), SDG10 (reduced inequalities), and SDG16 (peace, justice, and strong institutions) [79]. Thus far, undernutrition has been the neglected twin of HIV—the global TB elimination effort cannot afford to ignore it anymore.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number 5T32AI052074-13 to PS]; the Burroughs Wellcome/ASTMH Postdoctoral fellowship to PS; US Civilian Research and Development Foundation [grant number USB-31150-XX-13 to N. S. H. ]; the National Science Foundation [cooperative agreement OISE-9531011 to N. S. H.], with federal funds from the Government of India’s Department of Biotechnology, the Indian Council of Medical Research, the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the Office of AIDS Research and distributed in part by CRDF Global; grant from the Warren Alpert Foundation and Boston University School of Medicine [N.S.H]; the Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute [grant number 1UL1TR001430 to N.S. H.]; and funding from Boston University Foundation India [to N.S.H.]. The funders had no role in study design, analysis, or reporting.

Ethical statement

There are no consent issues to report.

Author contribution

MEC, NSH, and PS all contributed to both the development and the writing of the paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.The end TB strategy [Internet]. World Health Organization. Geneva; 2015 Aug [cited 2021 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/the-end-tb-strategy.

- 2.Tuberculosis [Internet]. World Health Organization. 2021 [cited 2021 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis.

- 3.Tuberculosis deaths rise for the first time in more than a decade due to the COVID-19 pandemic. World Health Organization [Internet]. 2021 Oct 14 [cited 2021 Nov 27]; Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/14-10-2021-tuberculosis-deaths-rise-for-the-first-time-in-more-than-a-decade-due-to-the-covid-19-pandemic.

- 4.Global Tuberculosis Report. Geneva; 2021.

- 5.Cegielski J, Demeshlaira L. Nutrition and Management. In: Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition. p. 294–9.

- 6.Cegielski J, McMurray D. Nutrition and Susceptibility. In: Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition. p. 287–94.

- 7.Koethe J.R., von Reyn C.F. Protein-calorie malnutrition, macronutrient supplements, and tuberculosis. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 2016;20(7):857–863. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sinha P., Davis J., Saag L., Wanke C., Salgame P., Mesick J., et al. Undernutrition and tuberculosis: public health implications. J Inf Dis. 2019;219(9):1356–1363. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aibana O., Franke M.F., Huang C.C., Galea J.T., Calderon R., Zhang Z., et al. Impact of vitamin A and carotenoids on the risk of tuberculosis progression. Clin Inf Dis. 2017;65(6):900. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aibana O., Franke M.F., Huang C.C., Galea J.T., Calderon R., Zhang Z., et al. Vitamin E status is inversely associated with risk of incident tuberculosis disease among household contacts. J Nutrit. 2018;148(1):56–62. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxx006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang A, Smit E, Semba R. Nutrition and infection. In: Nelson K, Masters Williams C, editors. Infectious Disease Epidemiology: Theory Practice. Burlington; 2013. p. 305–18.

- 12.London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Adults and body mass index (BMI) [Internet]. The use of epidemiological tools in conflict-affected populations: open-access educational resources for policy-makers. 2009 [cited 2022 Feb 25]. Available from: http://conflict.lshtm.ac.uk/page_126.htm.

- 13.Murray J.F. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the cause of consumption: from discovery to fact. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(10) doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1639OE. Available from: www.atsjournals.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schatz A., Bugle E., Waksman S.A. Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Exp Biol Med. 1944:66–69. doi: 10.3181/00379727-55-14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: control of infectious diseases. Morb Mort Wkly Rep, 1999;48(29):621–9. [PubMed]

- 16.McKeown T., Record R.G. Reasons for the decline of mortality in England and wales during the nineteenth century. Popul Stud. 1962;16(2):94–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cegielski J.P., McMurray D.N. The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis: evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):286–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhargava A., Pai M., Bhargava M., Marais B.J., Menzies D. Can social interventions prevent tuberculosis? the papworth experiment (1918–1943) revisited. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(5):442–449. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201201-0023OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniels M. Tuberculosis in Europe during and after the second world War.—I. Br Med J. 1949;1065 doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4636.1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Cleeff M.R., Hueting E., Dessing A. In: Tuberculosis and war. Murray J., editor. Karger Publishers; San Francisco: 2018. Tuberculosis in The Netherlands before, during, and after World War II; pp. 134–143. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lumey L.H., Stein A.D., Kahn H.S., van der Pal-de Bruin K.M., Blauw G.J., Zybert P.A., et al. Cohort profile: the Dutch hunger winter families study. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36(6):1196–1204. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ekamper P., Bijwaard G., van Poppel F., Lumey L.H. War-related excess mortality in The Netherlands, 1944–45: New estimates of famine- and non-famine-related deaths from national death records. Histor Methods. 2017;50(2):128. doi: 10.1080/01615440.2017.1285260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cochrane A. Tuberculosis among prisoners of war in Germany. Br Med J. 1945;2(4427):656–658. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4427.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cegielski J., McMurray D. The relationship between malnutrition and tuberculosis: evidence from studies in humans and experimental animals. Int J Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 2004;8(3):286–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bhargava A. Undernutrition, nutritionally acquired immunodeficiency, and tuberculosis control. BMJ Clin Res. 2016;355. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Beisel W. Nutrition and immune function: overview. J Nutrit. 1996;126(10):2611S–2615S. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.suppl_10.2611S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhargava A., Benedetti A., Oxlade O., Pai M., Menzies D. Undernutrition and the incidence of tuberculosis in India: national and subnational estimates of the population-attributable fraction related to undernutrition. Nat Med J India. 2014;27(3):128–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lönnroth K., Williams B.G., Cegielski P., Dye C. A consistent log-linear relationship between tuberculosis incidence and body mass index. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;39(1):149–155. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyp308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoyt K.J., Sarkar S., White L., Joseph N.M., Salgame P., Lakshminarayanan S., et al. Effect of malnutrition on radiographic findings and mycobacterial burden in pulmonary tuberculosis. PloS One. 2019;14(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0214011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Podewils L.J., Holtz T., Riekstina V., Skripconoka V., Zarovska E., Kirvelaite G., et al. Impact of malnutrition on clinical presentation, clinical course, and mortality in MDR-TB patients. Epidemiol Inf. 2010;139(1):113–120. doi: 10.1017/S0950268810000907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krapp F., Veliz J.C., Cornejo E., Gotuzzo E., Seas C. Bodyweight gain to predict treatment outcome in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Peru. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2008;12(10):1153–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peetluk L.S., Rebeiro P.F., Cordeiro-Santos M., Kritski A., Andrade B.B., Durovni B., et al. Lack of weight gain during the first 2 months of treatment and human immunodeficiency virus independently predict unsuccessful treatment outcomes in tuberculosis. J Inf Dis. 2020;221(9):1416–1424. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan A., Sterling T.R., Reves R., Vernon A., Horsburgh C.R. Lack of weight gain and relapse risk in a large tuberculosis treatment trial. Am J Respir Crit Care. 2006;174(3):344–348. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200511-1834OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anaam M.S., Ibrahim M.I.M., Al Serouri A.W., Bassili A., Aldobhani A. A nested case-control study on relapse predictors among tuberculosis patients treated in Yemen’s NTCP. Public Health Action. 2012;2(4):168–173. doi: 10.5588/pha.12.0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birlie A., Tesfaw G., Dejene T., Woldemichael K. Time to death and associated factors among tuberculosis patients in Dangila Woreda, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2015;10(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kvasnovsky C.L., Cegielski J.P., Erasmus R., Siwisa N.O., Thomas K., van der Walt M.L. Extensively drug-resistant TB in Eastern Cape, South Africa: high mortality in HIV-negative and HIV-positive patients. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndromes. 2011;57(2):146–152. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821190a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zachariah R., Spielmann M.P., Harries A.D., Salaniponi F.M.L. Moderate to severe malnutrition in patients with tuberculosis is a risk factor associated with early death. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2002;96(3):291–294. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(02)90103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Justine M., Yeconia A., Nicodemu I., Augustino D., Gratz J., Mduma E., et al. Pharmacokinetics of first-line drugs among children with tuberculosis in Rural Tanzania. J Pediatric Inf Dis Soc. 2020;9(1):14–20. doi: 10.1093/jpids/piy106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramachandran G., Hemanth Kumar A.K., Bhavani P.K., Poorana Gangadevi N., Sekar L., Vijayasekaran D., et al. Age, nutritional status and INH acetylator status affect pharmacokinetics of anti-tuberculosis drugs in children. Int J Tubercul Lung Disease. 2013;17(6):800–806. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.ter Beek L., Alffenaar J.W.C., Bolhuis M.S., van der Werf T.S., Akkerman O.W. Tuberculosis-related malnutrition: public health implications. J Inf Dis. 2019;220(2):340–341. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cegielski J.P., Arab L., Cornoni-Huntley J. Nutritional risk factors for tuberculosis among adults in the United States, 1971–1992. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(5):422. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leung C.C., Lam T.H., Chan W.M., Yew W.W., Ho K.S., Leung G., et al. Lower risk of tuberculosis in obesity. Arch Internal Med. 2007;167(12):1297–1304. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Talat N., Perry S., Parsonnet J., Dawood G., Hussain R. Vitamin D deficiency and tuberculosis progression. Emerg Inf Dis. 2010;16(5):853. doi: 10.3201/eid1605.091693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sinha P. Personal communication.

- 45.Martins N., Morris P., Kelly P.M. Food incentives to improve completion of tuberculosis treatment: randomised controlled trial in Dili, Timor-Leste. BMJ. 2009;339 doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sudarsanam T.D., John J., Kang G., Mahendri V., Gerrior J., Franciosa M., et al. Pilot randomized trial of nutritional supplementation in patients with tuberculosis and HIV–tuberculosis coinfection receiving directly observed short-course chemotherapy for tuberculosis. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(6):699–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02761.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campa A., Baum M.K., Bussmann H., Martinez S.S., Farahani M., van Widenfelt E., et al. The effect of micronutrient supplementation on active TB incidence early in HIV infection in Botswana. Nutrit Dietary Supplem. 2017;45(9) doi: 10.2147/NDS.S123545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pakasi T.A., Karyadi E., Suratih N.M.D., Salean M., Darmawidjaja N., Bor H., et al. Zinc and vitamin A supplementation fails to reduce sputum conversion time in severely malnourished pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Indonesia. Nutrition J. 2010;9(41) doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cantalice Filho J.P. Food baskets given to tuberculosis patients at a primary health care clinic in the city of Duque de Caxias, Brazil: effect on treatment outcomes. J Brasil Pneumol. 2009;35(10):992–997. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132009001000008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuel B., Volkmann T., Cornelius S., Mukhopadhay S., Mejo J., Mitra K., et al. Relationship between nutritional support and tuberculosis treatment outcomes in West Bengal, India. J Tuberculosis Res. 2016;4(4):219. doi: 10.4236/jtr.2016.44023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grobler L., Nagpal S., Sudarsanam T.D., Sinclair D. Nutritional supplements for people being treated for active tuberculosis. Cochr Database System Rev. 2016 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006086.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cintron C., Narasimhan P.B., Locks L., Babu S., Sinha P., Rajkumari N., et al. Tuberculosis—learning the Impact of Nutrition (TB LION): protocol for an interventional study to decrease TB risk in household contacts. BMC Inf Dis. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06734-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bhargava A., Bhargava M., Velayutham B., Thiruvengadam K., Watson B., Kulkarni B., et al. The RATIONS (Reducing Activation of Tuberculosis by Improvement of Nutritional Status) study: a cluster randomised trial of nutritional support (food rations) to reduce TB incidence in household contacts of patients with microbiologically confirmed pulmonary tuberculosis in communities with a high prevalence of undernutrition, Jharkhand, India. BMJ Open. 2021;11(5):e047210. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Pee S., Grede N., Mehra D., Bloem M.W. The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:531–541. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tola H.H., Holakouie-Naieni K., Tesfaye E., Mansournia M.A., Yaseri M. Prevalence of tuberculosis treatment non-adherence in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2019;23(6):741–749. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.18.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.de Oliveira S.M., Altmayer S., Zanon M., Sidney-Filho L.A., Moreira A.L.S., de Tarso D.P., et al. Predictors of noncompliance to pulmonary tuberculosis treatment: an insight from South America. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kulkarni P., Akarte S., Mankeshwar R., Bhawalkar J., Banerjee A., Kulkarni A. Non-adherence of new pulmonary tuberculosis patients to anti-tuberculosis treatment. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(1) doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.109507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Felton CP. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection. New York; [cited 2021 Nov 28]. Available from: www.harlemtbcenter.org.

- 59.Sinha P., Lakshminarayanan S.L., Cintron C., Narasimhan P.B., Locks L.M., Kulatilaka N., et al. Nutritional supplementation would be cost-effective for reducing tuberculosis incidence and mortality in India: the ration optimization to impede tuberculosis (ROTI-TB) model. Clinical Inf Dis. 2021 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oxlade O., Huang C.-C., Murray M. Estimating the impact of reducing under-nutrition on the tuberculosis epidemic in the Central Eastern States of India: a dynamic modeling study. PLoS One. 2015;10(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128187. e0128187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Odone A., Houben R.M.G.J., White R.G., Lönnroth K. The effect of diabetes and undernutrition trends on reaching 2035 global tuberculosis targets. Lancet Diab Endocrinol. 2014;2(9):754–764. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70164-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 [Internet]. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO; 2021 Jul [cited 2021 Nov 27]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/online/cb4474en.html#chapter-2_1.

- 63.Devereux S., Béné C., Hoddinott J. Conceptualising COVID-19’s impacts on household food security. Food Security. 2020;12(4):769–772. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01085-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kansiime M.K., Tambo J.A., Mugambi I., Bundi M., Kara A., Owuor C. COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev. 2021;137 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.India under COVID-19 lockdown. Lancet. 2020; 395(10233):1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Cilloni L., Fu H., Vesga J.F., Dowdy D., Pretorius C., Ahmedov S., et al. The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tuberculosis epidemic a modelling analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;28 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang Y., Khan S., Ma X. Climate change impacts on crop yield, crop water productivity and food security – a review. Prog Nat Sci. 2009;19(12):1665–1674. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gregory P., Ingram J., Campbell B., Goudriaan J., Hunt L., Landsberg J., et al. In: The terrestrial biosphere and global change: implications for natural and managed systems. Walker B., Steffen W., Canadell J., Ingram J., editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1999. Managed production systems; pp. 229–270. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kumar S.S. Cyclone, Salinity intrusion and adaptation and coping measures in coastal Bangladesh. Space Culture India. 2017;5(1):12. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Singh K., McClean C.J., Büker P., Hartley S.E., Hill J.K. Mapping regional risks from climate change for rainfed rice cultivation in India. Agric Syst. 2017;156:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stott P. How climate change affects extreme weather events. Science. 2016;352(6293):1517–1518. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Food prices go up in West Bengal due to Cyclone Amphan. Money Control [Internet]. 2020 May 25 [cited 2021 Nov 29]; Available from: https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/business/pb-fintech-arm-invests-rs-10-8-crore-more-in-visit-health-holds-minority-stake-7778511.html.

- 73.Semple K. ‘We’re losing the fight’: tuberculosis batters a venezuela in crisis. New York Times. 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/20/world/americas/venezuela-tuberculosis.html Mar 20 [cited 2021 Nov 27]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arenas N.E., Cuervo L., Avila E.F., Duitama-Leal A., Pineda-Peña A.-C. The burden of disease and the cost of illness attributable to Tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS associated to massive migration between Colombia and Venezuela. Int J Mycobacteriol. 2021;10(5):29. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rytter M.J.H., Kolte L., Briend A., Friis H., Christensen V.B. The immune system in children with malnutrition–a systematic review. PloS one. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105017. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25153531/ Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Auld A.F., Tuho M.Z., Ekra K.A., Kouakou J., Shiraishi R.W., Adjorlolo-Johnson G., et al. Tuberculosis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children starting antiretroviral therapy in Côte d’Ivoire. Int J Tubercul Lung Dis. 2014;18(4):381–387. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guideline: Nutritional care and support for patients with tuberculosis. Geneva; 2013 [cited 2021 Nov 27]. Available from: www.who.int. [PubMed]

- 78.Yadav S., Atif M., Rawal G. Nikshay Poshan Yojana-another step to eliminate TB from India. IP Indian J Immunol Respir Med. 2018;3(2):28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 79.The 17 Goals | Sustainable Development [Internet]. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [cited 2021 Nov 29]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.