Abstract

Combination nanodrugs are promising therapeutic agents for cancer treatment. However, they often require the use of complex nanovehicles for transportation into the tumor site. Herein, a new class of carrier-free ionic nanomaterials (INMs) is presented, which are self-assembled by the drug molecules themselves. In this regard, a photothermal therapy (PTT) mechanism is combined with a chemotherapy (chemo) mechanism using ionic liquid chemistry to develop a combination drug to deliver multiple cytotoxic mechanisms simultaneously. Nanodrugs were developed from an ionic material-based chemo-PTT combination drug by using a simple reprecipitation method. Detailed examination of the detailed photophysical properties (absorption, fluorescence emission, quantum yield, radiative and non-radiative rate) of the INMs revealed significant spectral changes which are directly related to their therapeutic effect. The reactive oxygen species quantum yield and the light to heat conversion efficiency of the photothermal agents were shown to be enhanced in combination nanomedicines as compared to their respective parent compounds. The ionic nanodrugs exhibited an improved dark and light cytotoxicity in vitro as compared to either the chemotherapeutic or photothermal parent compounds individually, due to a synergistic effect of the combined therapies, improved photophysical properties and their nanoparticles’ morphology that enhanced the cellular uptake of the drugs. This study presents a general framework for the development of carrier-free dual-mechanism nanotherapeutics.

Graphical Abstract

In this study, self-assembled combination chemo-PTT nanomedicines are developed that display high synergystic toxicity towards breast cancer cells.

Introduction

The use of nanotechnology in cancer therapy has changed the conventional approaches in therapeutic drug design. Nanomedicines are able to treat cancer using passive strategies via the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) phenomenon. Furthermore, specialized coatings of nanomedicine can target specific receptors at the cell’s surface. Organic nanoparticles (NPs) have attracted considerable attention among researchers due to their excellent biocompatibility, biodegradability and non-toxicity. Drugs can be encapsulated in organic NPs such as carbon quantum dots,1 polymeric NPs,2 and polypeptide-based NPs3 for better drug delivery.4 However, these carriers often have no therapeutic effect and involve a complex synthetic protocol, which can further complicate clinical application.5 Thus, carrier-free nanoformulations have also been investigated.6

Although nanoscale therapeutics have shown great development over the years, there is still a need to enhance the efficacy of these drugs due to multi-drug resistance of chemotherapy (chemo) compounds alone. It has become common practice to use chemotherapeutics in conjunction with other traditional treatment methods such as radiation or surgical removal of cancerous tissue. Such combination therapy approaches use two or more mechanisms simultaneously to treat the cancer with greater efficacy, lower concentration of therapeutic agents and minimized side effects of the drug.7 For effective treatment of cancer, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several combinations of medication for clinical use.8,9 The use of NPs in combination cancer therapy is very popular due to enhanced therapeutic efficacy, reduced drug resistance and minimal side effects. However, the high cost and complex syntheses of currently available commercial drugs and their NPs production are some of the major issues that obstruct the use of existing nanomedicine in combination therapy.

Recently, the combination of chemo with photodynamic therapy (PDT) or photothermal therapy (PTT) has shown to be promising in treating various cancers in vitro and in vivo.10 PTT is a promising approach to cure cancer because of its selectivity and lesser side effects than traditional methods.11,12 PTT exploits photothermal agents (PTAs) which usually absorb near infrared (NIR) or longer wavelength electromagnetic radiation that can penetrate deeper in the body tissue and treat deep seated tumors. In addition, an excellent PTA should exhibit exceptional molar extinction coefficient and high internal conversion rate (non-radiative) which are key features to acquiring superior light to heat conversion efficiency.13,14 Moreover, PTAs are known to generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) as well when irradiated with light.15 Recent studies involving PTT have utilized precious metal plasmonic NPs and nanomaterials which have been demonstrated to be highly effective at generating high heat.16 However, these non-biodegradable inorganic NPs can be very expensive and have possible metal-related toxicity which may cause detrimental side-effects to normal cells.17,18 Moreover, many promising inorganic NPs have failed during clinical trials.19,20 Thus, recent efforts have sought out to utilize organic nanomedicines in PTT.

Organic indocyanine dyes, such as indocyanine green, IR783, and IR820 (NIR dyes) are commonly studied PTAs due to their high absorbance at longer wavelength (from 700–900 nm). One major issue of utilizing these molecules alone as PTT drugs is their water-solubility, meaning that the only method of cellular uptake is via passive diffusion into the cell.21 The clinical use of IR820 in humans poses other challenges as well, such as short half-life in vivo and rapid metabolism by the liver.3 NPs based on organic PTAs have been developed and shown promising efficacy compared to the free aqueous drug.22,23 However, this process requires complex synthetic protocol and/or formation of complicated nanostructures by utilizing multistep, expensive and time-consuming protocol.24 A best idea yet may be carrier-free nanomedicines that are self-assembled by the drug molecules themselves. There have been increasing efforts in developing this type of therapeutic agent which already have drawn much attention in cancer treatment.25 In this work, a facile synthesis of carrier-free nanomedicines was introduced from chemo-PTT combination therapy molecule by taking advantage of ionic liquid (IL) chemistry.

ILs are a class of materials that have gained much interest of researchers over the last few decades due to their unique properties which are attractive for many different applications.26–29 Some of these properties include high thermal and photostability as well as an incredible ease of tunability.30,31 A subset of this class includes frozen ionic salts, or ionic materials (IMs). These materials are not liquid at room temperature, but they retain many of the desirable characteristics of room temperature ILs. IMs are getting tremendous attention due to the formation of stable NPs, while ILs can only produce nanodroplets.32 It is anticipated that creating carrier free ionic nanomaterials (INMs) from chemo-PTT IMs may be an effective new avenue for combination cancer therapy applications. Herein, chemo-PTT IMs are prepared by combining a chemotherapeutic cation with a PTA counter anion using IL chemistry. The NPs derived from IMs i.e., chemo-PTT INMs are prepared without utilizing any matrices. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of combination chemo-PTT IM-based carrier-free nanomedicines. The photophysical properties and the in vitro cytotoxicity are studied in detail to investigate the potential of newly developed combination nanodrugs

Results and Discussion

Synthesis of chemo-PTT IMs and INMs combination drugs

Synthesis of chemo-PTT combination drugs derived from PTAs (NaIR783 or NaIR820 dye) and chemotherapeutic molecule, trihexyltetradecylphosphonium chloride ([P66614]Cl) were performed using a facile, one-step ion exchange reaction which has been previously reported.32 Briefly, NaIR820 dye was dissolved in water and one molar equivalent of [P66614]Cl was dissolved in dichloromethane (DCM), separately (Scheme 1a). The aqueous and organic solutions were combined and stirred under dark conditions for 48 hr. The aqueous layer containing sodium chloride (NaCl) was removed, and the organic layer was washed 5 times with water to remove any remaining byproduct. The DCM layer, containing trihexyltetradecylphosphonium IR820 ([P66614][IR820]) was dried via rotary evaporation and further freeze dried to remove any trace amounts of water. A similar method was implemented to prepare another chemo-PTT IM, trihexyltetradecylphosphonium IR783 ([P66614][IR783]). Synthetic scheme of [P66614][IR783] IM is shown in Scheme S1 of the supporting information.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis scheme of a) chemo-PTT combination drug [P66614][IR820] and b) chemo-PTT INMs

INMs are derived from chemo-PTT combination IMs. NPs were prepared using a reprecipitation method similar to previously reported methods.33,34 Briefly, a concentrated stock solution of the combination IMs was prepared in ethanol and an aliquot was dropwise added to the vial containing water under sonication in a sonication bath. The solution was sonicated for 10 min with a 15 min resting time before characterization (Scheme 1b). For in vitro studies, INMs are prepared using the same method as mentioned before with slight modification.33 Briefly, a stock solution of chemo-PTT IMs was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and resuspended into cell media under sonication for in vitro studies. Several concentrations of INMs were prepared by using different volume of stock solution using similar method.

Characterization

Synthesized IMs, [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][IR820] were firstly characterized using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS). The mass-to-charge ratio peaks in positive and negative ion mode verified the presence of both the cation and anion in [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][IR820] IMs. An expected m/z+ peak of 483.5 was calculated for trihexyltetradecylphosphonium cation (P66614+) which is observed in positive ion mode with an experimental value of m/z+ peak at 483.5 and 483.6 for [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][IR820], respectively. In negative ion mode, the experimental m/z− peak for IR783 at 725.2 corresponds to a calculated value of 726.4 for [P66614][IR783] and an experimental m/z− peak for IR820 at 825.4 corresponds to a calculated value of 826.4 for [P66614][IR820]. Mass spectra results are given for both compounds in Figure S1–S4 in the supporting information. These chemo-PTT IMs are further characterized using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) instrument. NMR spectra are presented in Figure S5 and S6 in the supporting information. [P66614][IR783]: Green solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO): δ 0.85 (m, 14H), 1.34 (m, 62H), 1.80 (m, 14H), 2.12 (m, 8H), 2.75 (t, 4H), 4.32 (t, 4H), 6.39 (d, 1H), 7.49 (t, 1H), 7.62 (t, 1H), 7.78 (d, 1H), 8.05 (t, 2H), 8.30 (q, 2H). [P66614][IR820]: Green/brown solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, (CD3)2SO): δ 0.86 (m, 14H), 1.35 (m, 54H), 1.74 (m, 22H), 2.18 (m, 8H), 2.73 (t, 4H), 4.21 (t, 4H), 6.39 (d, 2H), 7.29 (t, 2H), 7.45 (d,t, 4H), 7.61 (d, 2H), 8.27 (d, 2H).

Thermogravimetric analysis of the samples was also performed to determine the samples’ thermal stability. Usually, organic compounds do not exhibit high thermal stability and PTAs can generate significant heat after absorbing electromagnetic radiation. Therefore, thermal stabilities of the synthesized IMs were investigated and compared to parent PTAs. Examination of results reveals greater thermal stability of IMs (Figure S7 in the supporting information). Further discussion is given in the supporting information document.

INMs from NIR dye-based IMs were characterized by transmission electron microscope (TEM) to investigate their size and morphology. INMs of [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][I820] were found to be spherical in shape with diameters of 28.9±4.2 nm and 41.2±9.2 nm, respectively. Previous research has shown that NPs with sizes from 10–200 nm can passively target cancerous tissue via the EPR effect.10,35,36 It is observed from TEM images (Figure 1a and Figure 1b) that [P66614][IR783] formed stable NPs while [P66614][I820] NPs showed agglomeration. From dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements, the average hydrodynamic diameter of the [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][I820] NPs were found to be 104.1 and 126.6 nm, respectively (Figure 1c and Figure 1d). Zeta potential for [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][I820] INMs in deionized distilled water was found to be −33.1±1.6 mV and −32.5±2.5 mV, respectively. The negative value implies that most of the NIR dye anion is localized at the surface of NPs while the hydrophobic phosphonium moieties mostly reside in the core of NPs.

Figure 1.

TEM images of (a) [P66614][IR783] and (b) [P66614][IR820] NPs where the scale bar is 100 nm. DLS plots for (c) [P66614][IR783] and (d) [P66614][IR820] NPs.

Photophysical properties

Photophysical characteristics of NIR dye parent compounds, combination IMs as well as INMs were investigated in ethanol and in water. This fundamental characterization is very important to investigate the performance of a PTA in the chemo-PTT combination IMs (ethanol) and INMs (water). The absorption maxima wavelength, molar absorptivity, fluorescence emission and quantum yield, are the crucial parameters which affect the light to heat conversion efficiency, non-radiative rate constant and the ROS quantum yield of a PTA agent. Therefore, changes in the absorption and fluorescence spectra were studied in detail and compared with their respective parent compounds. Since the chemotherapeutic drug cannot absorb or emit light, photophysical properties of IMs and INMs were compared with their respective NIR parent compounds (PTAs only).

In ethanol, both NaIR783 and [P66614][IR783] IM samples exhibit a similar absorption spectra with peak position at 785 nm (Figure 2a). In water, NaIR783 absorption spectrum is slightly blue shifted to 776 nm while [P66614][IR783] INMs spectrum shows a 22 nm bathochromic shift to 798 nm. Since the typical laser irradiation wavelength is 808 nm, the red-shift of absorption peak is beneficial as it will absorb more light at laser wavelength. Fluorescence emission spectra of parent NaIR783, derived chemo-PTT IMs and INMs samples are presented in Figure 2b. NaIR783 and chemo-PTT [P66614][IR783] IM in ethanol exhibited similar fluorescence emission spectra shape and wavelength maxima (816 nm, Ex: 783 nm). Aqueous NaIR783 has a fluorescence emission peak maximum at 798 nm (Ex: 783 nm), while a blue shift of approximately 18 nm is observed (in comparison to IMs) in the fluorescence emission peak of chemo-PTT INMs.

Figure 2.

Absorbance of (a) NaIR783 and [P66614][IR783] (c) NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] in water and ethanol at a concentration of 5 μM. Fluorescence emission of (b) NaIR783 and [P66614][IR783] at 783 nm excitation wavelength (d) NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] at 820 nm excitation wavelength in water and ethanol at a concentration of 5 μM.

Absorbance spectra of the IR820 based compounds in ethanol solvent reveals that the spectra shapes are very similar with a slight enhancement of absorbance intensity of the IR820 in the combination [P66614][IR820] IMs (Figure 2c). In water, the same shape of absorption spectra is observed for parent NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] INMs. However, [P66614][IR820] NPs absorption intensity is about five times greater than NaIR820 soluble parent dye. This enhanced molar absorptivity of [P66614][IR820] chemo-PTT combination NPs compared to parent compound suggests the role of the bulky phosphonium chemotherapeutic cation. Thus, a transparent counterion can affect the photodynamic properties of PTAs. A similar phenomena is seen for other classes of molecules such as porphyrins and phthalocyanines.33 The value of molar absorptivity is calculated for all four compounds in two different solvents and is reported in Table S1 in the supporting information. Two peaks with higher fluorescence emission intensity at wavelength maxima of 857 and 945 nm were observed for NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] IMs in ethanol (Ex: 820 nm, Figure 2d). Fluorescence emission spectra for NaIR820 reveals only one peak in water at 916 nm (Ex: 820 nm), which is consistent with reported spectra.37 However, [P66614][IR820] INMs in water showed two peaks with slight hypsochromic shift at 852 and 941 nm. Photostability experiments were performed by recording fluorescence emission of PTAs over a 30 min time period. It was found that IMs and INMs show exceptionally high photostability (Figure S8 in the supporting information).

Fluorescence quantum yield and photophysical rate constants

Fluorescence quantum yield (FLQY) for parent PTAs, chemo-PTT IMs and its INMs are calculated using relative method to investigate their photothermal performance. For a PTA to be efficient, the majority of photons that are excited need to non-radiatively decay back to ground state in order to generate sufficient heat to induce tumor cell death (Figure 3).38 Thus, the FLQY should be low for PTT capable compounds.39 FLQY was measured using Equation S1 mentioned in the supporting information. FLQY values for all compounds are listed in Table 1 (aqueous) and Table S2 (ethanol) in the supporting information. [P66614][IR783] INMs and IM exhibits significant decrease in FLQY, indicating that replacing sodium ion (Na+) from parent compound via P66614+ to develop IR783-based IM and INMs effectively lowered the FLQY. Similar results were observed for IR820-based INMs. The quantum yield value for NaIR820 in ethanol is increased upon conversion to IMs. However, when the [P66614][IR820] IM is reprecipitated into NPs, the quantum yield is greatly lowered, indicating that the combination INMs have the better potential to serve as photothermal drug as compared to their respective parent PTAs.

Figure 3.

Jablonski diagram showing mechanism of PDT and PTT possibility of PTAs.

Table 1.

Photophysical rates of IR dyes and INMs in water: quantum yield (ΦF), radiative rate (krad), and non-radiative rate (knon-rad).

| Compound | ΦF (%) | krad/s−1 × 106 | knon-rad/s−1 × 108 |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaIR783 in water | 1.78 | 3.42 | 7.22 |

| [P66614][IR783] INMs in water | 0.44 | 7.23 | 16.2 |

| NaIR820 in water | 0.31 | 2.27 | 7.25 |

| [P66614][IR820] INMs in water | 0.14 | 6.73 | 21.4 |

The value of non-radiative rate constant can be correlated to light to heat conversion efficiency of the PTT drug.40 A high value of non-radiative rate constant has been shown for efficient photothermal heat generation.40 Therefore, radiative (krad) and non-radiative (knon-rad) rate constants were also determined for all samples using Equation S2 and S3 in the supporting information. The results are tabulated in Table 1. It can be seen from the data that the photodynamics of PTAs are greatly affected, and the rate is altered when converted into combination INMs. The calculated values of knon-rad was increased more than 2 times in chemo-PTT INMs than their respective NIR dyes in water. Thus, it is predicted that both combination INMs should produce more heat upon irradiation. These results demonstrate the potential of chemo-PTT INMs to serve as a better PTAs in comparison to their parent compounds.

Detailed examination of photophysical characterization revealed that the counterion significantly affects the absorption and fluorescence emission characteristics, FLQY, as well as radiative and non-radiative rate constant of the PTAs. Thus, incorporating bulky phosphonium chemotherapeutic cation does not only induce chemotherapeutic and hydrophobic (essential to make NPs in aqueous media) characteristics in the resulting chemo-PTT combination IMs and INMs but it also affects the photophysical properties which can have significant impact on the photothermal efficacy and in vitro cytotoxicity under light irradiation.

Photothermal heating efficiency

The photothermal heating efficiency is a crucial parameter when assessing the performance of a PTA. Therefore, an experiment is designed to investigate the light to heat conversion efficiency of the PTAs (NIR dyes) in the combination drug in comparison to the parent compounds, The drugs were prepared in cell media (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, DMEM) containing serum (fetal bovine serum, FBS). 1 mL of solution was subjected to laser irradiation (808 nm, 1 W/cm2) for 5 min while monitoring bulk solution temperature change via thermocouple, followed by 5 min of cooling (Figure 4). The maximum change in temperature for the NIR parent dyes and INMs range from 17.7 °C to 21.9 °C indicating that all the samples can adequately heat the solution upon irradiation at room temperature. By using Figure 4 and Equations S4–S7 in the supporting information, the efficiency of the drugs’ light to heat conversion can be quantified. It was found that [P66614][IR783] INMs exhibited very high light to heat conversion efficiency as compared to their corresponding NaIR783 parent dye. Furthermore, the comparison of the present results with the previously reported NPs in literatures revealed that INMs exhibited the better light to heat conversion efficiency. For example, bovine serum albumin NPs loaded with cyanine dye showed only 29%41 light to heat conversion efficiency and amphiphilic polypeptide-based NPs encapsulated with NIR absorbing cyanine derivative exhibited slightly less (41%) efficiency as compared to the combination INMs.42 The high efficiency of INMs is attributed to the improved knon-rad, greater molar absorptivity at 808 nm and high temperature change (when irradiated with laser) of [P66614][IR783] INMs.43 NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] INMs showed similar values of heat efficiency (Table 2). This is expected, as there is no significant shift in absorbance of [P66614][IR820] INMs. Although [P66614][IR820] INMs did not show any enhancements in light to heat conversion efficiency upon irradiation, they possess dual toxicity mechanisms and can still exhibit better cellular uptake due to nanoparticle morphology.

Figure 4.

Bulk photothermal heating and cooling curves of NaIR783 and [P66614][IR783] INMs (a) as well as NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] INMs (b) at a concentration of 50 μM where CM represents cell media control.

Table 2.

Photothermal heat efficiency values and ROS quantum yield (ΦΔ) of NIR dyes in ethanol and water.

ROS generation upon irradiation

A typical mechanism of PDT is the production of ROS upon irradiation of light. Previously, it has also been found that conversion of PDT molecules like porphyrins into IMs can enhance their efficacy due to preventing aggregation of photosensitizer in the presence of bulky ions.34 It has recently been found that NIR-absorbing dyes such as NaIR783 and NaIR820 are capable of producing ROS such as singlet oxygen as well as heat when irradiated with light.14 Thus, an experiment is designed to determine the changes in ROS quantum yield of the compound upon replacing small counter cation (Na+) of both NIR dyes with bulky phosphonium counter cation. To determine the ROS quantum yield, a solution of PTAs (as parent NIR dye or combination chemo-PTT IM) mixed with 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) probe solution in ethanol was irradiated using 808 nm laser (1 W/cm2) at 15 s intervals for a total of 300 s (Figure 5). A control experiment is performed by irradiating DPBF in ethanol and recording absorbance to ensure ROS is produced by PTAs alone (Figure S9 in the supporting information). This result indicates DPBF has a stable absorbance in the absence of PTA. A similar experiment is performed in aqueous media for INMs and PTAs separately (Figure S10 and S11 in the supporting information). ROS quantum yields were calculated using Equation 1. NaIR783 has a reported ROS quantum yield value of 0.7% in water, and NaIR820 has a literature value of 7.7% in ethanol solvent.44 These values were used as a standard to calculate ROS quantum yield of chemo-PTT IMs and INMs. [P66614][IR783] IMs and INMs exhibited greater ROS quantum yield values than NaIR783 in both water and ethanol solvents (Table 2). A similar result was obtained for [P66614][IR820] combination drug, with increased ROS quantum yield in both ethanol and in water compared to parent compound. P66614+ cation has been shown to enhance the ROS production of planar photosensitizers by preventing face-to-face aggregation.33 The enhanced ROS production by INMs-based photosensitizers is of critical importance in the overall phototoxicity of the newly developed chemo-PTT combination INMs. Moreover, combination INMs can provide a mechanism of enhanced dark cytotoxicity due to the presence of chemotherapeutic cation and nanoparticles’ morphology.

Figure 5.

Photodegradation of DPBF upon increasing irradiation time in the presence of [P66614][IR820] in ethanol

In vitro dark toxicity

Dark toxicity is determined to examine the performance of chemotherapeutic ion in the parent molecule and in the chemo-PTT INMs. [P66614]Cl is known to induce cytotoxic effect towards cancerous cells.29 This study can answer if the replacement of small chloride ion of the chemotherapy molecule, [P66614]Cl with NIR dye alters its chemotherapeutic effect. Since the parent [P66614]Cl chemotherapy molecule is used in the liquid form while the hydrophobic chemo-PTT molecules are used as NPs in the cell media, the dark cytotoxicity of the drug should be affected. Previous reports have shown that INMs can show enhanced toxicity compared to their parent drugs.28,29,46 Therefore, cellular dark toxicity of the parent PTAs and chemo-PTT INMs was analyzed in two different cell lines (cancerous breast from mouse and human) to inspect potential selectivity of the combination INMs in regard to species. Two cell lines are used since the phosphonium based chemotherapeutic cation is known to exhibit different toxicity in various cell lines.47 In MCF-7 and 4T1 cells, at all concentrations from 0.5 to 20 μM, parent NaIR783 and NaIR820 dyes are completely non-toxic to the cells in dark (Figure 6 and Figure S12 in the supporting information). [P66614][IR783] and [P66614][IR820] INMs displayed decreased half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values (Table S3 in the supporting information) in MCF-7 cells as compared to the parent chemotherapeutic molecule. A significant increase in cytotoxicity of the phosphonium chemotherapeutic drug was observed when converted to combination INMs. This is attributed to the NPs morphology of INMs. No significant change in IC50 values were observed for INMs in two different cell lines which demonstrate that NPs chemotherapeutic activity is not specie dependent.

Figure 6.

Cell viability of (a) NaIR783-based drugs and (b) NaIR820-based drugs in MCF-7 cancer cells at various concentration in dark for 24 hr. P values are determined using two-tailed student’s t-test and are reported as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005

In vitro light toxicity (photothermal effect)

Light cytotoxicity is examined to inspect the performance of the PTAs in combination INMs form as compared to their parent compounds. All photophysical characterization data such as light to heat conversion efficiency, non-radiative rate constant and improved ROS quantum yield suggested the better performance of PTAs in chemo-PTT INMs. Therefore, the PTT capability of each compound was investigated by incubating INMs in MCF-7 cells under irradiation with NIR laser. Dark toxicities of the drugs were similar in both MCF-7 and 4T1 cells, thus further cellular experiments were performed only in MCF-7 cells. This study is performed at 4 hr to avoid the cytotoxicity impact of the chemotherapeutic moiety present in INMs. After 4 hr incubation of cells with INMs and parent compounds separately, the drug containing media was removed, and cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Finally, cells were exposed to 808 nm laser at 5 W/cm2 power for 5 min. Afterward, cell viability was determined via MTT assay (Figure 7). A control experiment for light cytotoxicity was also performed using [P66614]Cl drug (Figure S13). For [P66614][IR820] INMs, the IC50 is lowered by more than half with laser irradiation. NaIR820 showed a much greater IC50 value under laser irradiation compared to INMs (Table 3). Light toxicity of INMs and PTAs were also investigated at a lower laser power of 1 W/cm2 (Figure S14). Their IC50 value are increased slightly, as expected (Table S4). However, they still exhibit a higher toxicity as compared to parent compounds. This is attributed to combination therapy effect, improved photophysical properties, enhanced light to heat conversion efficiency, and excellent ROS quantum yield of INMs compared to parent molecules.

Figure 7.

Cytotoxicity of (a) NaIR783 and [P66614][IR783] INMs and (b) NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] INMs incubated 4 hr in MCF-7 cells and irradiated with 808 nm laser (5 W/cm2) for 5 min. P values are determined using two-tailed student’s t-test and are reported as *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005.

Table 3.

IC50 values (μM) for NIR dye and INMs under 808 nm laser (5 W/cm2) irradiation and in the dark in MCF-7 cells.

| Sample Name | IC50 values under laser (4 hr incubation) | IC50 values in dark (24 hr incubation) |

|---|---|---|

| NaIR783 | 8.26±0.61 | 45.29±1.25 |

| [P66614][IR783] | 3.92±0.31 | 4.76±0.45 |

| NaIR820 | 51.41±1.86 | NA |

| [P66614][IR820] | 2.17±0.14 | 5.01±0.31 |

| [P66614]Cl | 7.60±0.16 | 6.23±0.24 |

The combination index (CI) is an important parameter when discussing the synergy of combination therapy techniques. CI values were calculated using the Chou-Talalay method48 (Equation 2) to investigate the synergy of INMs. It was found that the CI for [P66614]IR783] was 0.99, indicating an additive combination of the two therapies. However, [P66614][IR820] exhibited a CI value of 0.33, indicating that these INMs display exceptionally synergistic behavior towards MCF-7 cells.

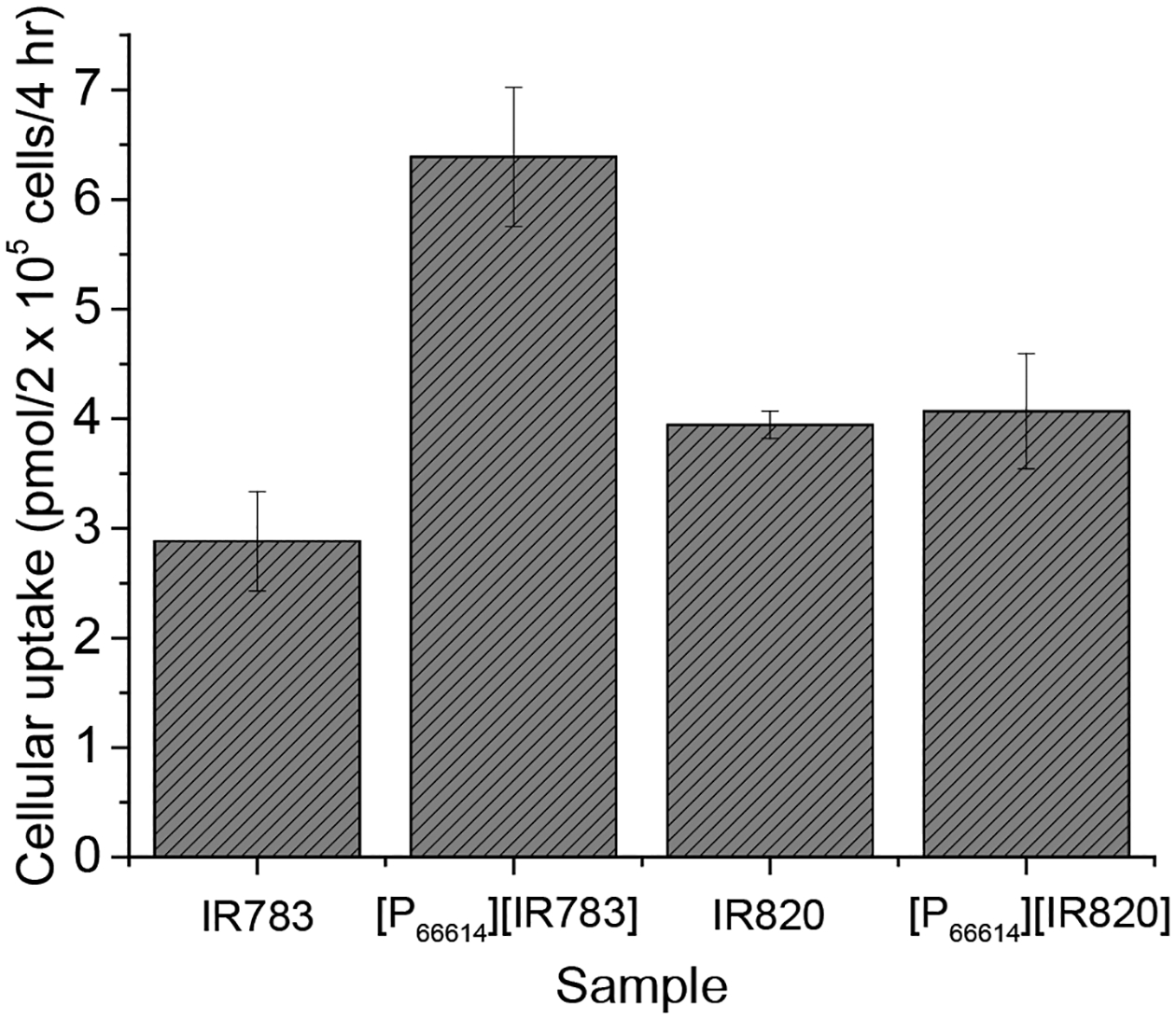

Cellular uptake

In order to better understand the improved efficacy of INMs over parent compounds, cellular uptake was quantitively measured using a spectrophotometric protocol similar to a reported method.6 Cellular uptake of molecules has crucial importance when analyzing drug retention and efficacy. Following incubation of INMs for 4 hr, cells were washed three times with PBS and dissolved with DMSO to expose NIR-absorbing INMs. By comparing absorbance of INMs treated cells to an untreated blank, the cellular uptake was quantified (Figure 8). The cellular uptake of [P66614][IR783] INMs is almost doubled as compared to NaIR783 aqueous parent dye. This proves the enhanced uptake of these chemo-PTT nanomedicines is due to INMs morphology as compared to soluble parent PTAs. Examination of cellular uptake results obtained for NaIR820 and [P66614][IR820] INMs exhibit similar concentration of both compounds. It indicates that [P66614][IR820] INMs did not show preferential uptake which can be attributed to the agglomeration of [P66614][IR820] NPs as observed in TEM (Figure 2). Therefore, a slight change in dark cytotoxicity is observed with [P66614][IR820] NPs.

Figure 8.

Cellular uptake of INMs compared to free dyes after 4 hr incubation of 40 nmol drug with MCF-7 cancer cells. Data are presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

The aggregate of results suggests superior dark and light toxicity of combination INMs as compared to their respective chemotherapeutic and PTT parent molecules. Thus, it demonstrates that a combination drug can easily be developed by simple ion exchange method to attain multiple mechanism in a single drug. These carrier-free nanomedicines can easily be prepared from combination IMs to attain enhanced cytotoxicity via multiple mechanisms with low concentration of the drug.

Conclusion

Two combination chemo-PTT IMs were synthesized using a one-step metathesis reaction that replaced the counterion of a chemotherapeutic IL with two different photothermally active NIR absorbing anions. The resulting products were converted into aqueous NPs using a simple reprecipitation method. The resulting INMs were characterized based on photophysical characteristics as well as their ability to generate heat and ROS upon NIR laser irradiation. The FLQY was decreased in the aqueous INMs which is crucial to enhancing photothermal efficiency and ROS production. Enhanced knon-rad and molar extinction coefficient at 808 nm of IR783-based INMs presented a great increase in photothermal efficiency and ROS quantum yield. Improved cytotoxicity was examined in both MCF-7 and 4T1 cell lines for both INMs. The combination effect of the INMs was also investigated in vitro in MCF-7 cells in dark as well as under light irradiation. It was found that chemo-PTT INMs exhibit lower IC50 values compared to either parent compound. This is due to combination of enhanced local heating by INMs compared to soluble parent IR dye as well as improved photophysical properties. Moreover, [P66614][IR783] INMs also showed improved cellular uptake by cancerous cells in comparison to their NaIR783 parent dye. The comparison of cytotoxicity results obtained for human and mouse breast cancer cells revealed that cytotoxicity of the INMs is not organism dependent. Additionally, CI values were determined and revealed that INMs exhibit synergistic toxicity compared to either treatment alone. Thus, it is concluded that cost effective IMs approach can be used to synthesize a combination therapy molecule. Moreover, carrier-free NPs can easily be prepared using such approach. Furthermore, the photophysical properties can easily be tuned by tailoring the counterions.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

NaIR820 dye (Lot#: MKBZ1942V), NaIR783 dye (Lot#: BCBZ9950), [P66614]Cl, (Lot#: BCBR3818V), and DPBF were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Triply deionized ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm) was obtained using Purelab Ultrapure water purification system (ELGA, Woodridge, IL, USA). Ethanol, DMSO, and DCM were purchased from VWR (Radnor, PA, USA) of reagent quality. DMSO was filtered through 0.2 micron polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter prior to use in cell culture. Starna (Atascadero, CA, USA) quartz cuvettes with 4 polished sides of 1 cm path length were used for spectroscopic measurements. Copper grids were purchased from SPI Supplies for characterization of NPs by TEM. Model breast cancer cell line MCF-7 and 4T1 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). DMEM, Trypsin-EDTA, 0.25% Penicillin and Streptomycin were purchased from Caisson Lab (Smithfield, UT, USA). FBS was obtained from Atlanta Biologicals (Lawrenceville, GA, USA). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) and PBS were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Instruments and methods

Mass spectrometry was performed using electrospray ionization (ESI) technique (Bruker Ultraflex II, Billerica, MA, USA). Scans were performed in both positive and negative mode to determine the molecular weight of newly developed chemo-PTT IMs. JEOL 400 MHz nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer was used to verify purity of IMs. Thermogravimetric analysis (Mettler Toledo, Colombus, OH, USA) was performed to analyze the thermal stability of the combination therapy IMs. Samples were heated in air at a rate of 10 °C/min over a range of 25–800 °C and the data was plotted as a function of mass lost. A Fischer-Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA) FS20H bath sonicator was used for synthesis of carrier free NPs (INMs) from combination IMs. TEM (JEOL FEI Tecnai F20, Tokyo, Japan) was performed to investigate morphology of NPs. Nanobrook 90Plus Zeta (Brookhaven, Holtsville, NY, USA) instrument was used with polystyrene 4-sided cuvette (Thomas, Swedesboro, NJ, USA) to view the hydrodynamic size distribution (dynamic light scattering) and surface charge (zeta potential) of combination NPs in water. UV-Vis absorbance spectrophotometer (Shimadzu 3600, Kyoto, Japan) and fluorescence spectrofluorometer (Horiba Nanolog, Kyoto, Japan) were employed to determine photophysical properties of IMs and INMs. These properties included absorption wavelength maxima, molar absorptivity, FLQY and internal conversion rate. Detailed calculation of FLQY and rate constants related to radiative and non-radiative transitions are given in equations S1–S3 in the supporting information. The quantum yield of IM and INMs were determined relative to the parent NaIR820 compound, using an excitation wavelength of 820 nm and integrating emission from 830–1200 nm.

Photostability

Photostability studies were conducted by acquiring fluorescence emission measurements in kinetic mode every 0.1 s over a time period of 30 min using excitation and emission slit widths of 14–14 nm. These measurements were performed in a four-sided polished window quartz cuvette with a path length of 1 cm. Excitation wavelengths of 798, 785, and 786 nm were used to excite [P66614][IR783] INMs in water, NaIR783 in ethanol, and [P66614][IR783] combination IMs in ethanol respectively, and the fluorescence emission was monitored at 816 nm in ethanol and 800 nm in water. Excitation wavelengths of 837, 846, and 854 nm were used to excite [P66614][IR820] INMs in water, NaIR820 in ethanol, and [P66614][IR820] chemo-PTT combination IMs in ethanol respectively, and the fluorescence emission was monitored at 925 nm

Photothermal conversion efficiency

To study the photothermal effect induced by NIR absorption of PTAs, 1 mL sample of 50 μM of combination INMs prepared in cell culture medium (DMEM) was irradiated by a NIR laser (808 nm, 1 W/cm2) for 5 min. The temperature of the solutions was monitored by a thermocouple microprobe submerged in a quartz cuvette. The probe was placed at such a position that direct irradiation of the laser on the probe was avoided. The photothermal effect of chemo-PTT INMs and parent PTAs (NaIR783 and NaIR820) was measured as described above, and the cooling curve was obtained by monitoring temperature after the laser was powered off. The equations used for quantification of photothermal conversion efficiency are given in Equations S4–S7 in the supporting information.

ROS quantum yield

PTAs mainly generate heat, but they are known to also produce ROS. Therefore, ROS quantum yield experiment is designed to investigate the performance of combination drug in comparison to their parent compound upon irradiation with laser. ROS quantum yield was determined by monitoring the decrease in absorbance of DPBF probe after irradiation of PTA in ethanol and aqueous solution. In a typical experiment, the sample was dissolved in ethanol along with DPBF at a final concentration of 100 μM probe and 5 μM sample (PTA). The rate of ROS production was quantified by irradiating the solution with 808 nm laser (1 W/cm2) and then recording the absorption of the solution using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The ROS produced during irradiation of photosensitizer was scavenged using DPBF. After each irradiation treatment, changes in the absorbance intensity of DPBF at 411 nm were monitored using UV-Vis spectrophotometer. ROS quantum yield of the sample, ΦΔ(std), was determined for each sample using the following Equation 1:

| (1) |

Where ФΔ(x) is the ROS quantum yield of standard and Sx and Sstd are slope values of decrease in probe absorbance (411 nm) for unknown and standard sample, respectively NaIR820 in ethanol was used as a standard to calculate the ROS quantum yield using a relative method (Equation 1) by comparing absorbance decrease of the probe and samples (parent PTAs, IMs and INMs). The ROS quantum yield of the IMs was reported as a ratio of the slope of probe’s absorbance decrease in IMs over in the NaIR820 (standard) using Equation 1.

Cell culture and in vitro cytotoxicity

Cell culture

Cell lines used include MCF-7 (ATCC® HTB-22) human breast cancer and 4T1 (ATCC® CRL-2539) mouse breast cancer. All cell lines were maintained as a monolayer at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in complete medium. MCF-7 and 4T1 cells were cultured in DMEM, with phenol red, supplemented with FBS (10% v/v) and penicillin/streptomycin antibiotic solution (500 units/ml).

In vitro dark cytotoxicity

Prior to experimentation, cells were seeded in 96 well plates at 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hr. DMSO was used to prepare drug stock solutions and the highest final concentration of 0.5% was used to avoid any cellular toxicity. Cells were then treated with different concentrations of drugs overnight at 37 °C. Chemo-PTT INMs were prepared at various concentrations by diluting stock solution in cell culture media following bath sonication, while maintaining a sterile environment. Appropriate controls with complete media alone and DMSO control without drug were included. Following treatment, cells were washed with PBS buffer. MTT assay was used to determine cell viability as described previously.51 An absorbance microplate reader (Synergy, H1) was used to determine optical density at 570 nm for MTT assay. For in vitro cell culture studies, each experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated independently at least three times. All data showing error bars are presented as mean ± S.D. unless otherwise mentioned. Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed student’s t-test.

Photothermal effect in vitro

Prior to experimentation, MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96 well plates at 104 cells per well and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hr. Upon reaching 70% confluence, the growth medium was replaced with drugs (INMs suspensions of the drugs and parent compounds) in complete cell medium. After incubation of the cells for 4 hr with drug, the cells were washed with PBS buffer, and growth medium was replaced prior to exposure to 808 nm laser (5 W/cm2 or 1 W/cm2) for 5 min. The cells were incubated for an additional 24 hr, and then the medium was replaced with culture medium (without phenol red) containing the MTT cell viability assay solution. The cell viability of the parent PTT and chemo-PTT INMs treated MCF-7 cells was then determined according to the above protocol.

Determination of combination index

CI was determined by Equation 252 using IC50 values of the various drugs under laser irradiation.

| (2) |

Where A+B indicates the combination drug (INMs) and drug A and B are the two parents drugs ([P66614]Cl or PTA).

Cellular uptake

Cellular uptake experiments were performed using MCF-7 cancer cells. Uptake of the drugs was quantified by use of UV-Vis spectrophotometer using a similar protocol reported in literature.6 In this case, 20 μM of INMs or parent dye in 2 mL cell media were added to a petri-dish with 2.0 × 105 cells. After incubation for 4 hr, drug containing cell media was removed, and cells were washed with PBS three times. The cells were digested with 3.5 mL DMSO, causing dissolution of internalized INMs/NIR dyes. The resulting solution was analyzed by measuring absorbance from INMs/parent molecules against a DMSO-digested cell media containing reference.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using two tailed Student’s t-test. P-values of *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Results shown are representative of at least three experiments and are expressed as mean ± S.D.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by the Arkansas INBRE program, supported by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, (NIGMS), P20 GM103429 from the National Institutes of Health. N.S. gratefully acknowledges financial support through the National Science Foundation EPSCoR Research Infrastructure under award number RII Track 4-1833004. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge Jeff Kamykowski at University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences for help with TEM imaging of INMs and Stuti Chatterjee at University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Footnotes

Footnotes relating to the title and/or authors should appear here.

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: [details of any supplementary information available should be included here]. See DOI: 10.1039/x0xx00000x

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare

Notes and references

- 1.Liu R, Zhang L, Zhao J, Luo Z, Huang Y and Zhao S, Adv. Ther, 2018, 1, 1800041. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valcourt DM, Dang MN and Day ES, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part A, 2019, 107, 1702–1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang K, Gao M, Fan L, Lai Y, Fan H and Hua Z, Biomater. Sci, 2018, 6, 2925–2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, Hanes J and Ensign LM, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2016, 99, 28–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang J, Tang H, Liu Z and Chen B, Int. J. Nanomedicine, 2017, 12, 8483–8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen M, Bhattarai N, Cong M, Pérez RL, McDonough KC and Warner IM, RSC Adv, 2018, 8, 31700–31709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mokhtari RB, Homayouni TS, Baluch N, Morgatskaya E, Kumar S, Das B and Yeger H, Combination therapy in combating cancer, Impact Journals LLC, 2017, vol. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blagosklonny MV, Cell Cycle, 2004, 3, 1035–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryan Q, Ibrahim A, Cohen MH, Johnson J, Ko C, Sridhara R, Justice R and Pazdur R, Oncologist, 2008, 13, 1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang D, Zhang J, Li Q, Tian H, Zhang N, Li Z and Luan Y, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10, 30092–30102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou L, Wang H, He B, Zeng L, Tan T, Cao H, He X, Zhang Z, Guo S and Li Y, Theranostics, 2016, 6, 762–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung HS, Verwilst P, Sharma A, Shin J, Sessler JL and Kim JS, Chem. Soc. Rev, 2018, 47, 2280–2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang X, Jain PK, El-Sayed IH and El-Sayed MA, Lasers Med. Sci, 2008, 23, 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Lu Z, Zhu X, Wang X, Liao Y, Ma Z and Li F, Biomaterials, 2013, 34, 9584–9592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li WT, Peng JR, Tan LW, Wu J, Shi K, Qu Y, Wei XW and Qian ZY, Biomaterials, 2016, 106, 119–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Panikkanvalappil SR, Hooshmand N and El-Sayed MA, Bioconjug. Chem, 2017, 28, 2452–2460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Debele TA, Peng S and Tsai HC, Int. J. Mol. Sci, 2015, 16, 22094–22136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan IU, Khan RU, Asif H, Alamgeer, Khalid SH, Asghar S, Saleem M, Shah KU, Shah SU, Rizvi SAA and Shahzad Y, Int. J. Pharm, 2017, 533, 111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luque-Michel E, Imbuluzqueta E, Sebastián V and Blanco-Prieto MJ, Expert Opin. Drug Deliv, 2017, 14, 75–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vega-Villa KR, Takemoto JK, Yáñez JA, Remsberg CM, Forrest ML and Davies NM, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2008, 60, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao JF, Wei XW, Ran B, Peng JR, Qu Y and Qian ZY, Nanoscale, 2017, 9, 2479–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumar P and Srivastava R, RSC Adv, 2015, 5, 56162–56170. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duong T, Li X, Yang B, Schumann C, Albarqi HA, Taratula O and Taratula O, Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol. Med, 2017, 13, 955–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu H, Cheng P, Chen P and Pu K, Biomater. Sci, 2018, 6, 746–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong T, Yao X, Zhang S, Guo Y, Duan XC, Ren W, Dan H, Yin YF and Zhang X, Sci. Rep, 2016, 6, 36614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng L, Li J, Yu M, Jia W, Duan S, Cao D, Ding X, Yu B, Zhang X and Xu FJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2020, 142, 20257–20269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Itoh H, Naka K and Chujo Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2004, 126, 3026–3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macchi S, Zubair M, Ali N, Guisbiers G and Siraj N, J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol, 2021, 21, 6143–6150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Macchi S, Zubair M, Hill R, Alwan N, Khan Y, Ali N, Guisbiers G, Berry B and Siraj N, ACS Appl. Bio Mater, 2021, 4, 7708–7718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welton T, Biophys. Rev, 2018, 10, 691–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moodley KG, Der Pharma Chem, 2019, 11, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhattarai N, Siraj N, Magut PKS, Mcdonough K, Sahasrabudhe G and Warner IM, Mol. Pharm, 2018, 15, 3837–3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Siraj N, Kolic PE, Regmi BP and Warner IM, Chem. - A Eur. J, 2015, 21, 14440–14446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolic PE, Siraj N, Hamdan S, Regmi BP and Warner IM, J. Phys. Chem . C, 2016, 120, 5155–5163. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fang J, Nakamura H and Maeda H, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev, 2011, 63, 136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou W, Zhao X, Qian X, Pan F, Zhang C, Yang Y, De La Fuente JM and Cui D, Nanoscale, 2016, 8, 104–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fernandez-Fernandez A, Manchanda R, Lei T, Carvajal DA, Tang Y, Kazmi SZR and McGoron AJ, Mol. Imaging, 2012, 11, 99–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu S, Zhou X, Zhang H, Ou H, Lam JWY, Liu Y, Shi L, Ding D and Tang BZ, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2019, 141, 5359–5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou B, Li Y, Niu G, Lan M, Jia Q and Liang Q, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 29899–29905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ou H, Li J, Chen C, Gao H, Xue X and Ding D, Sci. China Mater, 2019, 62, 1740–1758. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou B, Li Y, Niu G, Lan M, Jia Q and Liang Q, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2016, 8, 29899–29905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laxman K, Reddy BPK, Mishra SK, Gopal MB, Robinson A, De A, Srivastava R and Ravikanth M, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2020, 12, 52329–52342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu S, Liu H-W, Huan S-Y, Yuan L and Zhang X-B, Mater. Chem. Front, 2020, 5, 1076–1089. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fückel B, Roberts DA, Cheng YY, Clady RGCR, Piper RB, Ekins-Daukes NJ, Crossley MJ and Schmidt TW, J. Phys. Chem. Lett, 2011, 2, 966–971. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi C, Wu JB and Pan D, J. Biomed. Opt, 2016, 21, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Magut PKS, Das S, Fernand VE, Losso J, McDonough K, Naylor BM, Aggarwal S and Warner IM, J. Am. Chem. Soc, 2013, 135, 15873–15879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stepnowski P, Składanowski AC, Ludwiczak A and Łaczyńska E, Hum. Exp. Toxicol, 2004, 23, 513–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chou TC, Cancer Res, 2010, 70, 440–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lei T, Fernandez-Fernandez A, Manchanda R, Huang YC and McGoron AJ, Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 535, 2014, 5, 313–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paardekooper LM, Van Vroonhoven E, Ter Beest M and Van Den Bogaart G, Int. J. Mol. Sci, DOI: 10.3390/IJMS20174147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kilaparty SP, Agarwal R, Singh P, Kannan K and Ali N, Cell Stress Chaperones, 2016, 21, 593–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Emamzadeh M, Desmaële D, Couvreur P and Pasparakis G, J. Mater. Chem. B, 2018, 6, 2230–2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.