Abstract

The perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PNDs) are one of the most common complications in elderly patients characterized by various forms of cognitive decline after anesthesia and surgery. Although the etiology for PNDs remained unclear, neuroinflammation has been characterized as one of the major causes, especially in the elderly patients. The activation of glial cells including microglia and astrocytes plays a significant role in the inflammatory responses in central nerve system (CNS). Although carefully designed, clinical studies on PNDs showed controversial results. Meanwhile, preclinical studies provided evidence from various levels, including behavior performance, protein levels, and gene expression. In this review, we summarize high‐quality studies and recent advances from both clinical and preclinical studies and provide a broad view from the onset of PNDs to its potential therapeutic targets. Future studies are needed to investigate the signaling pathways in PNDs for prevention and treatment, as well as the relationship of PNDs and future neurocognitive dysfunction.

Keywords: astrocyte, cognitive impairment, microglia, neuroinflammation, perioperative neurocognitive disorders

In this review, we focused on the neuroinflammation in perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PNDs) from bench to bedside. The review not only presented the latest findings of PNDs in both clinical practice and preclinical experiment, but also pointed out useful biomarkers and potential therapeutic strategies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Throughout the ages, general anesthesia has been recognized as an “instantly reversible condition” that leaves no sequalae after emergence, despite remarkable alterations in consciousness and similarly dramatic changes in other organ systems. 1 However, increasing amount of evidence has shown that general anesthesia is not simply an “instantly reversible condition,” but has acute, even long‐lasting influence on central nerve system (CNS). 2 , 3 , 4 Coexisting with general anesthesia, orthopedic or cardiac surgeries often lead to acute or long‐term cognitive decline after surgical procedures. 5 These phenomena urge anesthetists to pay close attention to neurocognitive outcome in clinical practice.

Traditionally, all forms of cognitive impairments after anesthesia and surgery were termed postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), which was recently recommended to change into perioperative neurocognitive disorder (PND). 6 , 7 Depending on the time of onset, PNDs can be classified into neurocognitive disorder (occurring before anesthesia and surgery), postoperative delirium (POD, delirium occurring within hours to days after surgery), delayed neurocognitive recovery (occurring up to 30 days after anesthesia and surgery), and postoperative neurocognitive disorder (POND, occurring within weeks to months after anesthesia and surgery). 7 This classification aligns well with the phenotypically similar diseases defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version 5 (DSM‐5) and International Classification of Disease‐10 (ICD‐10). 8 , 9 In order to distinguish PNDs and traditional dementia (such as Alzheimer's disease), the use of DSM‐5 is also needed. 10 Since the definition for cognitive impairment after anesthesia and surgery has changed over the past several years and different cognitive evaluation tests were used in different studies (eg, whether the learning effect was corrected, and which neuropsychological test was used), 11 , 12 the exact rate of PNDs remain unclear. Nevertheless, consensus is made that newly diagnosed cognitive dysfunction after anesthesia and surgery may increase the risk of future brain dysfunction, including dementia, 10 , 13 Alzheimer's disease (AD), 14 , 15 and long‐term cognitive decline, 4 , 16 making PNDs a highly concerning condition, especially in the elderly population. In this way, the PNDs in this review is also focused postoperatively.

Neuroinflammation caused by anesthesia exposure and surgery has been characterized as a major contributor to cognitive decline in PNDs. 17 Recent studies reported that systemic stressors and other inflammatory cytokines broke down the blood brain barrier (BBB) and further resulted in neuroinflammation. 17 , 18 , 19 Preclinical experiments demonstrated that inflammatory cytokines secreted by either microglia or astrocytes resulted in cognitive decline, 20 , 21 impaired synaptic plasticity, 22 , 23 and brain functional changes. 20 Clinical data showed that PND patients had increased peripheral inflammatory cytokine levels, 24 increased risks of future cognitive impairment 25 and brain function decline. 26 Although effort has been made both clinically and preclinically to investigate the mechanisms, risk factors, clinical onset and development, and the long‐term outcome of PNDs, effective approaches to reverse this neurocognitive situation are lacking. What is more, the detailed mechanisms underlying the complicated clinical symptoms are still unclear and need further investigation.

In this article, we present a broad review of literatures regarding neuroinflammation in PNDs and its translational potential. Both clinical and preclinical studies are reviewed to provide an in‐depth understanding of the molecular mechanisms on the perioperative neuroinflammation and the pathogenesis of PNDs. We also summarize the potential targets and treatment strategies to manage this neurocognitive status, in order for a better long‐term outcome after anesthesia and surgery in the elderly.

2. CURRENT UNDERSTANDING IN PNDS: WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW, AND WE WHAT DO NOT KNOW YET?

Most of clinical studies focused on the POD, delayed neurocognitive recovery, and POND (based on the new definition according to the time of onset). Carefully designed clinical studies proved that intraoperative anesthesia depth monitoring, 27 , 28 , 29 dexmedetomidine infusion 30 , 31 intravenous anesthesia (as compared with inhalational anesthesia), 32 and multi‐modal analgesia 25 , 33 , 34 are effective to reduce the incidence of PNDs. Other approaches such as management of intraoperative body temperature 35 , 36 and blood pressure 37 may also help (Table 1). However, clinical study results differ from one another. For example, some studies showed that intraoperative blood pressure, 38 dexmedetomidine, 39 and anesthesia method 40 , 41 may not be as effective in reducing the incidence of PNDs as expected (Table 1). The reasons for these discrepancies may be the followings: (1) the mechanisms for PNDs may vary from case to case, although they share similar clinical symptoms. Variations in the time‐frame of inflammatory cytokines after abdominal and cardiac surgeries have been observed in preclinical studies 42 ; (2) the definition for postoperative cognitive decline has been changing over the past years, 17 making it hard to evaluate the a certain factor across multiple studies.

TABLE 1.

Studies concerning perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PNDs)

| References | Type of study | Method | Type of PNDs | Main findings | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MacKenzie et al (2018) | Meta‐analysis | Anesthesia depth | POD | POD (38.0% reduction) | Electroencephalogram‐guided anesthesia is associated with decreased POD |

| Bocskai et al (2020) | Meta‐analysis | Anesthesia depth |

POD POND |

POD (6.7% reduction) PND (3.0% reduction) |

BIS‐guided anesthesia reduced rate of POD at 1 day and PND at 12 weeks after anesthesia and surgery |

| Yang et al (2021) | RCT | Anesthesia depth | POD | MoCA score (average 1.24 higher, first 7 days) | Multi‐modal brain monitoring improves postoperative neurocognition. |

| Zhao et al (2020) | RCT | Dexmedetomidine |

POD Delayed Neurocognitive Recovery |

POD (decreased on day 1–3, p < 0.05) Delayed neurocognitive recovery (decreased on day 7, p < 0.05) |

Intraoperative use of dexmedetomidine significantly attenuated the rate of POD and delayed neurocognitive recovery |

| Su, et al, 2016 | RCT | Dexmedetomidine | POD | POD (14.0% reduction, first 7 days) | Use of dexmedetomidine decreases the incidence of POD in ICU in patients >65 yrs undergoing non‐cardiac surgery. |

| Deiner et al (2017) | RCT | Dexmedetomidine | POD | POD (increased for 0.8%, p > 0.94) | Use of dexmedetomidine cannot prevent POD from happening. |

| Zhang et al (2018) | RCT | Intravenous anesthesia | Delayed Neurocognitive Recovery | Delayed neurocognitive recovery (8.4% reduction, first 7 days) | Propofol reduced the rate of delayed neurocognitive recovery as compared with sevoflurane. |

| Konishi et al (2018) | RCT | Intravenous anesthesia |

Delayed Neurocognitive Recovery POND |

Delayed neurocognitive recovery (p = 0.26) PND (p = 0.61 and 0.23, 3 and 12 months after surgery) |

No difference was found between propofol and sevoflurane for inducing cognitive impairment |

| Sun et al (2019) | Meta‐analysis | Intravenous anesthesia | POD | MMSE score (significantly lower in patients using propofol until 7 days) | Propofol had great adverse effect as compared with sevoflurane |

| Kristek et al (2019) | RCT | Multi‐modal analgesia | POD | POD (22.0% reduction, first 72 hours) | Multi‐modal analgesia significantly reduced the rate of POD. |

| Subramaniam et al (2019) | RCT | Multi‐modal analgesia | POD | POD length (1 day reduced, first 48 hours) | Acetaminophen reduced the length of POD in elderly patients |

| Mu et al (2017) | RCT | Multi‐modal analgesia | POD | POD (4.8% reduction, first 5 days) | Multi‐dose of parecoxib supplemented to intravenous morphine decreased the rate of POD without increasing side effects. |

| Rudiger et al (2016) | Observational | Temperature | POD | Hypothermia (34.5℃ vs. 35.1℃) | Low body temperature is one of the major risks for POD in ICU. |

| Wagner et al (2021) |

Retrospective Exploratory |

Temperature | POD | Hypothermia (χ2 = 54.94, df = 4) | A significant relationship was found between hypothermia and POD |

| Maheshwari et al (2020) | Observational | Blood Pressure | POD | Hypotension (p = 0.009, 95% CI: 1.03–1.20) | Intraoperative hypotension is moderately associated with POD within 5 days after surgery. |

| Feng, et al (2020) | Meta‐analysis | Blood Pressure |

POD POND |

Hypotension (p = 0.10 for POD: p = 0.37 for POCD) | No significant correlations between intraoperative hypotension and POD / PND. |

The type of PNDs were adjusted according to the latest diagnostic criteria.

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; POD, postoperative delirium; POND, postoperative neurocognitive disorder; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

As for the different anesthesia methods, several studies demonstrated that combined anesthesia (eg, combined general anesthesia and epidural anesthesia) or regional anesthesia had lower incidence of PNDs as compared with general anesthesia alone. 43 , 44 , 45 However, there are also studies claiming no significant difference in PND rates between regional and general anesthesia. 46 , 47 The contradictory findings in clinical practice pointed out that the mechanism for PNDs may vary, suggesting that mechanistic studies are obviously warranted.

While clinical studies reported controversial results, most of the preclinical experiments claimed that the neuroinflammation triggered by peripheral inflammatory cytokines/stressors is the major cause of clinical symptoms. 17 , 18 , 48 Previous studies found that surgical trauma‐induced systemic inflammation may cause neuroinflammation through damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), complement cascade and coagulation cascade, all of which could further induce glial activation in the CNS. 18 Inflammatory responses triggered by surgery and anesthesia broke down the blood brain barrier (BBB) and cause further neuroinflammation, 18 the process of which started the inflammatory response in CNS. In elderly patients, the progressive loss of hippocampal BBB integrity has already been proved in individuals without evident cognitive impairments. 49 Preclinical experiment (LPS stimulation) shown that the microglia and astrocyte activation and inflammatory cytokines expression caused long‐lasting cognitive impairment in rodent animals. 20 , 23 , 50 Meanwhile, the anesthetic agents also induced significant microglia/astrocyte activation directly in CNS. 51 , 52 After the microglia and astrocyte activation, both types of the glia secreted inflammatory cytokines including interleukin (IL)‐1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α, and other cognitive‐related cytokines, in the progress of neuroinflammation, 20 , 53 causing impaired synaptic plasticity, 54 which further induced cognitive dysfunction.

Although there are various studies demonstrating the crosstalk between microglia and astrocyte, even the neurons in cognitive dysfunction, only few studies focused on the effect of PNDs. In this case, the effect of the glia response behind the PNDs pathologic process should be further studied to investigate the mechanism behind the clinical symptoms.

3. GLIAL ACTIVATION: THE SOURCE OF NEUROINFLAMMATION AND THE TARGET OF CLINICAL TRANSLATION

Although details remain unclear, increasing body of evidence supports the idea that both the microglia and astrocytes, and their interactions, contribute to the neuroinflammatory processes. 55 , 56 , 57 Long‐term activation of microglia and astrocytes result in long‐term synaptic inhibition and cognitive dysfunction, 17 , 23 inflammatory responses in the hippocampus, 17 , 18 and eventually neurodegenerative diseases. 58 , 59

3.1. Microglia activation

Microglia, one of the major resident cells in CNS (accounting for about 5–10% of the total cells in human and mice), are traditionally considered the major source of neuroinflammatory response. 60 They have long been believed to be CNS‐resident phagocytes to remove excessive debris functionally. In recent years, by means of sequencing technologies and other advancing methods, it was revealed that microglia are not just passive bystanders of CNS pathologies, but also determinants of diseases. 61 , 62

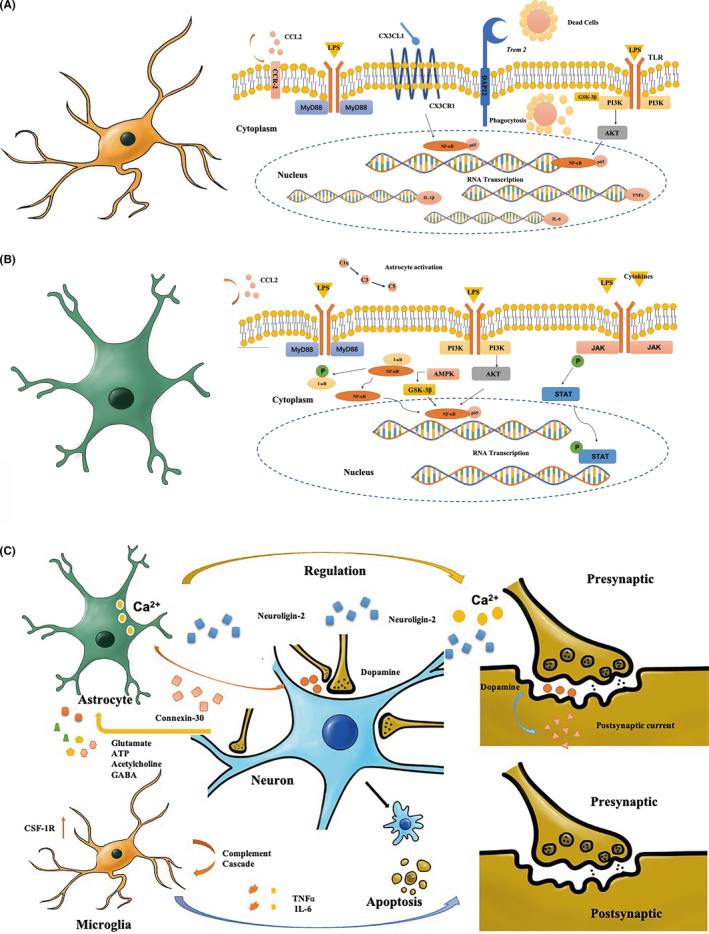

Anesthesia and surgery‐induced microglial activation has been demonstrated to cause cognitive dysfunction (Figure 1A). Preclinical study has shown that the TLR/GSK‐3β/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway reduced the activation of the nuclear factor‐kappa B (NF‐κB) signaling pathway in microglia, decreased the M1 type (classical activation) and increased the M2 type (alternating activation) transformation 63 in a PND model of tibial fracture surgery. In another PND model upon exposure of inhalational anesthesia (3% sevoflurane) in pregnant rats, the NF‐κB signaling pathway played a significant role in microglia activation, which further induced the upregulation of inflammatory cytokines (IL‐1β, IL‐6, and TNFα) and cognitive dysfunction in the descendent pups. 64 The Trem 2, which is mostly seen in activated microglia in AD patients, 65 , 66 was also overexpressed in PND preclinical models. Both preclinical (mice with liver lobe resection) and clinical studies (hip‐fracture patients) proved significant changes in Trem 2 associated with cognitive impairment. 67 , 68 The microglial CX3CL1/CX3CR1 is another overactivated pathway in AD patients, which affects the clearance of Aβ deposits. 69 Although rarely reported in clinical studies, activation of the microglial CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling pathway has been observed in preclinical PND model after tibial fracture. 70 These results suggested that PNDs and neurodegenerative diseases may share similar pathways. Interestingly, aside from directly activated by stress stimulators, the microglia can also be activated indirectly by astrocytes via the CCL2‐CCR2 signaling pathway. 71 In the tibial fracture PND model, the upregulation of astrocyte‐derived CCL2 induced the overexpression of microglial CCR2, while blockade of CCR2 by RS504393 attenuated microglial inflammatory responses and improved cognitive function.

FIGURE 1.

Activated microglia and activated astrocytes in neuroinflammation. (A) Representative image of activated microglia in neuroinflammation. (B) Representative image of activated astrocytes in neuroinflammation. (C) Representative image of activated astrocytes and microglia on neuron dysfunction. CX3CL1/CX3CR1, chemokine fractalkine ligand 1/chemokine fractalkine receptor; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; IL‐1β, interleukin‐1 beta; MyD88, myeloid differentiation factor 88; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐kappa B; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3‐kinase; AKT, Ser/Thr kinase; JAK, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; I‐ κB, inhibitor of NF‐κB; P, Phosphate; AMPK, adenosine 5’‐monophosphate‐activated protein kinase; GSK‐3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; Trem, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell

Meanwhile, perioperative events including hypoxia (STAT1 protein activation drives M1 activation), 72 cerebral ischemia (CysLT2R‐ERK1/2 pathway mediates M1 polarization), 73 hemorrhage (activating the PKA/CREB signaling pathway may promote M2 polarization; IL‐15 mediates the crosstalk of astrocyte and microglia in disease development; using EPZ6438 attenuates neuroinflammation by H3k27me3/SOCS3/TRAF6/NF‐κB signaling pathway after hemorrhage), 74 , 75 , 76 Aβ accumulation (promotes M1 polarization), 77 autoimmune inflammatory disease (P2×4R signaling pathway favored the microglia phagocytosis), 78 and oxidative stress (reducing oxidative stress also attenuates M1 polarization) 79 may also cause microglial activation. However, one should note that not all of these signaling pathways contributes to cognitive impairment.

People then asked whether microglia are the only mediator in neuroinflammation. Recent studies showed that microglia also activate astrocytes in PNDs. 80 , 81 For example, eliminating early microglial activation in hippocampus attenuated etomidate‐induced long‐term hippocampal astrocyte activation. 82 This finding suggested that microglia activation occurs at early phase, while subsequent astrocyte may be responsible for long‐term cognitive impairment.

3.2. Astrocyte activation

Being one of the most abundant glia cells in the CNS (comprising for at least 50% of the brain and spinal cells by number in human and mice), the major function of the astrocyte is believed to participate the BBB maintenance, modulating synaptic plasticity, as well as neuronal survival and differentiation. 83 , 84 However, astrocytes can also be activated by microglia by the complement cascade (C5, C3 and C1q) and further cause neurotoxicity. 85 , 86 Thus, the astrocyte activation should also be considered as a significant contributor for neuroinflammation.

Abnormal astrogliosis has been shown to result in PNDs (Figure 1B). The NF‐κB pathway activation triggered by LPS injection or sevoflurane exposure may induce astrocyte activation and cognitive dysfunction in preclinical PND models 64 , 87 while administration of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), an NF‐κB signaling pathway blocker, can improve cognitive behavioral performance. 23 The PI3K‐AKT signaling pathway may also contribute to astrocytes activation in PNDs. 88 Preclinical study showed that activating the PI3K‐AKT signaling pathway led to significant complement cascade activation and transformation of astrocytes. 89 A further study using primary astrocyte culture demonstrated that the STAT3 protein was also involved after the AKT activation. 90 What is more, the CCL2/CCR2 signaling pathway astrocytes engaged has been proved to increase L‐1β and TNFα secretion in hippocampal CA1 region and in PND rats after tibial fracture surgery. 71 Oxidative scavenger edaravone or adiponectin have been reported to attenuate cognitive dysfunction and reduce inflammatory cytokines levels (IL‐1β, IL‐6, IL‐18 and TNFα), 91 , 92 suggesting that oxidative stress is essential in neuroinflammation. The mechanisms might involve the AMPK/GSK‐3β signaling pathway.

Aside from surgical trauma, perioperative events may also cause abnormal astrogliosis. However, these events are not always related to cognitive dysfunction. Perioperative ischemic/reperfusion events (activated by JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway and other inflammatory cytokines including IL‐6 while modulating by complement activation) 86 , 93 and postoperative pain (mainly by NF‐κB, JAK/STAT3, and CXCL13‐CXCR5 signaling pathway). 94

However, astrocytes also exert a protective effect on cognitive function. Recent study on astrocyte transcriptome sequencing analysis demonstrated that the human astrocytes could promote neuronal survival in vitro. 95 In aged rats undergone abdominal surgery, mesencephalic astrocyte‐derived neurotrophic factor (MANF) was upregulated after surgery, and recombinant human MANF reversed POD‐like behaviors. 96 This finding may provide new therapeutic targets for PNDs. One should be aware that the astrocyte activation is largely dependent on microglia. The crosstalk between astrocytes and microglia is critical. 56

3.3. Effects of activated microglia and astrocytes on neuronal dysfunction

Large amount of evidence demonstrated that astrocytes release neuroactive substances with a variety of effects on synaptic activity (Figure 1C). Astrocytes regulate neuronal synaptic plasticity by controlling Ca2+ flow 97 and reducing astrocytic Ca2+ signaling alters the microcircuits and induces repetitive behavior. 98 Dopamine in the synaptic cleft could increase astrocytic Ca2+ and suppress excitatory postsynaptic currents in mice, which is regulated by Ca2+ signaling manifested astrocyte activation. 99 The astrocytes also express and release several neural factors that affect neuronal functional status. For example, absence of astrocytic neuroligin 2 expression resulted in the loss of cortical excitatory synapse formation, 100 which may further cause cognitive dysfunction. In contrast, astrocytic connexin 30 may shorten the critical period for visual plasticity in mice during development. 101 In addition, evidence exists demonstrating neuronal apoptosis induced by astrocytes. 102

Interestingly, the astrocytes have also been found to respond to neurotransmitters including glutamate, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), acetylcholine, γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA), etc., in response to neuron dysfunction. 103 , 104 , 105 For example, in N‐methyl‐D‐aspartic acid (NMDA)‐induced excitotoxicity model, the astrocytes can sense neuronal activity 106 and protects neurons from excessive oxidation injury in by consuming incoming neuronal‐derived fatty acids. 107

On the contrary, the generation of neurotoxic astrocytes could be induced by activated microglia (Figure 1C). 85 Non‐activated microglia cultures can hardly induce neurotoxic astrocyte formation, even in the presence of LPS. Microglia also play a significant role in neuronal dysfunction. In mice with cognitive decline and hippocampal synaptic loss, the microglia were shown to activate the complement pathway (mainly C3q). 108 In tibial fracture, cognitive dysfunction was accompanied by microglia activation and significantly increased secretion of TNFα and IL‐6. 109 Meanwhile, colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) expression in microglia was upregulated in PND mice (confirmed by impaired performance in Morris water maze) after tibial fracture surgery. 109 As expected, inhibiting CSF1R in aged mice can improve cognitive function. 110 Whether activated microglia are a double‐edged sword in neuronal dysfunction needs further investigations. 111

4. CLINICAL BIOMARKERS: IS THERE ANYTHING WE CAN DO TO PREDICT PNDS FROM THE VERY BEGINNING?

Since PNDs are hard to cure, biomarkers would be of great use for preventive purposes. Recent studies reported several available biomarkers, which can be divided into the following three categories: trauma/surgery‐induced inflammatory markers, neurodegeneration disease‐related biomarkers, and neuroimaging markers (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Clinical biomarkers for perioperative neurocognitive disorders (PNDs)

| Reference | Biomarker | Type | Sample | Evidence | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quan et al (2019) | IL‐1β | Inflammatory | Plasma | Clinical | Lower IL−1β is followed by better cognitive function 7 days after anesthesia |

| Chen et al (2019) | IL‐6 | Inflammatory | Serum | Clinical | Patients developed into delirium had significant higher level of IL−6 at 6, 12 and 18 hours after surgery |

| Quan et al (2019) | CRP | Inflammatory | Plasma | Clinical | Lower CRP is followed by better cognitive function 7 days after anesthesia |

| Zhu et al (2020) | TNFα | Inflammatory | Plasma | Clinical | Higher level of TNFα is followed with lower MMSE score |

| Hov et al (2017) | S100β | Neurodegenerative | CSF | Clinical | In patients without preoperative delirium, higher S100β was observed in those develop into POD |

| Hassan et al (2020) | S100β | Neurodegenerative | Serum | Clinical | Patients without neuroprotective management had higher level of S100β followed with poorer cognitive performance 7 days after surgery. |

| Ballweg et al (2021) | Tau | Neurodegenerative | Plasma | Clinical | Plasma tau was significantly associated with delirium severity (p = 0.026) 1 day after surgery |

| Henjum et al (2018) | Trem2 | Neurodegenerative | CSF | Clinical | Delirium was associated with higher levels of TREM2 in patients without pre‐existing dementia (p = 0.046) |

| Jiang et al (2018) | Trem2 | Neurodegenerative | Hippocampus | Preclinical | The expression of Trem2 gene was down regulated after surgical trauma on day 3, 7 and 14 followed with behavioral changes in Morris Water Maze |

| Passamonti et al (2019) | FC | Neuroimaging |

Rs‐fMRI data PET data |

Clinical | Neuroinflammation in AD induced abnormal FC |

| Franzmeier et al (2019) | FC | Neuroimaging |

Rs‐fMRI data PET data |

Clinical | FC from rs‐fMRI between any given region of interest (ROI) pair was associated with higher covariance in tau‐PET binding in the same ROIs |

| Mu et al (2020) | ALFF | Neuroimaging | Rs‐fMRI data | Clinical | AD patients without depression had higher increased ALFF on bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left middle frontal gyrus and left frontal gyrus |

| Zhuang et al (2020) | ALFF | Neuroimaging | Rs‐fMRI data | Clinical | MCI patients with aggregation vascular risk factors had different ALFF as compared with those without the risks. |

| Parisot, et al (2018) | Topology structure | Neuroimaging | Rs‐fMRI data | Clinical | The topology structures are different in AD and ASD patients |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; ALFF, amplitude of low frequency fluctuations; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; CRP, C‐reactive protein; CSF, cerebral spinal fluid; FC, functional connectivity; IL, interleukin; PET, positron emission tomography; rs‐fMRI, resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; Trem, triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cell.

Commonly used inflammatory cytokines include IL‐1β, 112 IL‐6, 113 C‐reaction protein (CRP), 112 TNFα, 114 etc. Although these inflammatory cytokines have been proved to change significantly in preclinical and clinical settings, their specificity are rather low. For example, increased expression of peripheral IL‐1β is also associated with other conditions such as kidney disease and autoimmunity. 115 In this case, postoperative elevation of IL‐1β should not be simply interpreted as a cognitive impairment predictor. Another example is that the increased expression of CRP inhibits lysis by recruiting factor H and activate complement C3b on damaged cells. 116 However, the C3b is known for activating microglia, 117 which may further induce PNDs. These results suggested that there is no single inflammatory cytokine that could accurate predict PNDs. Further investigations should focus on which combination of cytokine biomarkers would provide best sensitivity and specificity.

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum/plasma biomarkers are largely used in neurodegenerative diseases. The rationale for utilizing these biomarkers is that the PNDs and neurodegenerative diseases share similar clinical symptoms, and that PND patients have higher risks for future neurodegenerative disorders. The S100β protein, tau protein, and Trem2 are all well‐established CSF biomarkers in AD development. 118 Recent studies found that both CSF and serum S100β levels were significantly higher in patients developed into PNDs as compared to those who did not. 119 , 120 The CSF Trem2 is another promising biomarker for predicting neurodegenerative diseases. 121 Both clinical and preclinical studies provided evidence for Trem2 in PNDs. 67 , 68 Another observational study found that the change from preoperative to postoperative plasma tau protein level is associated with POD incidence and severity. 122 A clinical difficulty in anesthesia is that the CSF is hard to obtain, limiting the use of CSF specimen. Meanwhile, whether the expressions of these proteins are responsible for inducing PNDs need further investigation, since a causal relationship between these proteins with PNDs after surgery and anesthesia has not been confirmed yet.

Advances in imaging technology have greatly broadened our scope in studying brain function. The positive emission tomography (PET) examination has been used to evaluate neuroinflammation for years. 123 The resting‐state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs‐MRI) is a recently developed non‐invasive method to study brain functions. Human brain functions as networks, 124 and large amount of studies from recent years have elucidated various changes in functional connectivity (FC), 125 , 126 amplitude of low frequency fluctuations (ALFF) 127 , 128 and topology structures 129 in patients with cognitive impairment. Recent studies aimed to utilize rs‐MRI to analyze cognitive function after surgery. 130 , 131 However, concerns are raised since the results are not replicable in different studies, and different post‐processing methods may result in different MRI analyzing results. Whether the rs‐fMRI or PET can be used for predicting PNDs still need further investigation.

5. POTENTIAL THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES: IF WE CAN CURE OR PREVENT THE PNDS FROM ITS HAPPENING?

Although preclinical experiments pointed out several pathways that may be beneficial for clinical therapy, we must keep in mind that they are mainly used for preventing PNDs instead of curing the PNDs. As a result, the best PND management strategy is prevention from disease happening, through intraoperative anesthesia management for example, rather than treatment after disease onset.

5.1. Ulinastatin

Targeting NF‐κB signaling pathway is the closet to clinical practice since there are drugs available. Ulinastatin is a hydrolase protein inhibitor obtained from human urine. The ulinastatin was initially used for acute pancreatitis 132 while has recently been used for intraoperative anti‐inflammatory management in elderly patients. Clinical data have shown that adding ulinastatin to aged patients is effective to improve mini‐mental state examination (MMSE) score after spinal surgery. 24 In a meta‐analysis enrolling 10 high‐quality studies, ulinastatin treatment led to lower levels of inflammatory cytokines after surgery. 133 Preclinical experiments confirmed that its anti‐inflammatory mechanisms involve blockade of the NF‐κB signaling pathway. 134 Notably, some studies have reported a tendency of decreased mortality in patients following ulinastatin treatment. 132 , 135 Whether the treatment may also reduce the mortality in patients with PNDs still need further validation.

5.2. Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective alpha‐2 (α2) adrenoceptor agonist with sedative, analgesic, anxiolytic, sympatholytic, and opioid‐sparing properties. 136 Using dexmedetomidine has been proved to be able to reduce the rate of PNDs both after surgery and in the ICU. 3 , 31 , 137 Evidence from preclinical experiment found the protective effect may be the α2 receptor agonist activation. 138 Meanwhile, after giving the dexmedetomidine, the NF‐κB signaling pathway activation was also decreased. 139 , 140 These results also suggested that the dexmedetomidine attenuated the inflammatory responses and improved cognitive function by reducing the activation of NF‐κB signaling pathway. However, most of the studies mainly focused on POD, 30 , 31 , 39 the long‐term effect of dexmedetomidine on cognitive function still lacks enough evidence. Meanwhile, some of the studies draw contradictory results. 31 , 39 What is more, there are few studies focused on long‐term mortality in elderly patients. Thus, the effect of using dexmedetomidine still need further investigations.

5.3. Parecoxib sodium

Parecoxib sodium, a selective cyclooxygenase‐2 (COX‐2) inhibitor, is one of the most widely used non‐steroid anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in clinical practice. Recent studies have shown that parecoxib sodium resulted in decreased rate of PNDs, 141 , 142 possibly through its inhibiting the COX‐2 activity. 143 However, there are several concerns regarding the use of parecoxib sodium in preventing/treating PNDs: (1) most of the studies focused on POD or delayed neurocognitive recovery. Its long‐term effect in cognitive impairment is unknown; (2) parecoxib sodium is not the only drug used in most studies. This may lead to confounding results. Whether parecoxib sodium is effective for preserving long‐term cognitive function after anesthesia and surgery needs further investigations.

6. CX3CL1/CX3CR1 AND TREM 2 GENE EXPRESSION

Although evidence from clinical practice is lacking, preclinical experiment in aged rats suggested that blocking CX3CL1/CX3CR1 signaling with neutralizing antibody reduced inflammatory cytokine secretion and hippocampal astrocyte activation, and improved behavioral performances. 70 , 144 As for microglial Trem2, preclinical experiments found overexpression of Trem2 could downregulate inflammatory cytokines secretion and improve behavioral performances in rats after surgery. 67 Meanwhile, clinical data also suggested that CSF Trem2 levels are highly associated with post‐surgery delirium in patients without pre‐existing dementia. However, direct evidence proving that regulating CX3CL1/CX3CR1 and Trem2 expression can improve cognitive function after surgery is still lacking.

Although advances from both clinical practice and life science pointed out the potential causes and therapeutic targets for PNDs, it is still a major challenge for anesthesia practice. It is under debate whether the PNDs are highly related to cognitive impairment and other type of neurodegenerative disease later in life. Thanks to the sequencing method, the ACE gene missense mutation was found to be responsible for an early‐onset, rapid progressing dementia. 145 This finding highlighted the significance of gene‐sequencing method to studying PND mechanisms. Meanwhile, it also pointed out a novel direction for mechanistic studies, aside from traditional approaches such as taking blood samples and doing neuropsychological assessment. Another study found that the activation of PKC signaling pathway enhanced the treatment effect in refractory depression, 146 implying there might be different signaling pathways in different types of PNDs.

Aside from neurodegenerative disease, neurovascular disease may also cause cognitive dysfunction. For example, clinical practice shown that management of stroke risk factors may also reduce later dementia. 147 Another evidence is that elderly patients with NOTCH3 cysteine altering variants have higher risks of both stroke and cognitive impairment. 148 Meanwhile, brain dysfunction such as delirium can also be found in patients with stroke history. 149 These findings implying potential directions for PND studies.

Although signaling pathways responsible for PND still need further investigation, signaling pathways relating to other neuropsychological diseases are highly valuable to refer to in PND studies. Since preclinical experiments showed that the mechanisms of PNDs may be similar to those of neurocognitive disorders, 150 and PND patients share similar clinical symptoms with neurodegenerative disorders and neurovascular disorders in some extent, studies on the latter would reveal new directions for PND studies both preclinically and clinically.

Since the PNDs are hard to cure by far, future studies should focus on its etiology and risk factors to reduce its incidence. Meanwhile, preclinical experiments should focus on the long‐term activation of astrocytes and crosstalk among microglia, astrocytes and neurons. We believe that effort from both clinical and preclinical studies will finally benefit patient care.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yang Liu: writing the manuscript; Huiqun Fu: illustration drawing; Tianlong Wang: reviewing manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors may express their special thankfulness to Dr. Jian Ren from Department of Neurosurgery, Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University and Dr. Yu Zhang from Department of Urology, Peking University Third Hospital for their generous help on illustrations. The authors may also express their thankfulness to Prof. Yong He from Beijing Normal University for developing the Brain Network Viewer software (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/bnv/), which helped us to make the graphical abstract.

Liu Y, Fu H, Wang T. Neuroinflammation in perioperative neurocognitive disorders: From bench to the bedside. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28:484–496. doi: 10.1111/cns.13794

Funding information

This manuscript was supported by grants from Beijing Municipal Health Commission (Code: Jing2019‐2)

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

This is a review article and all the references have been published online.

REFERENCES

- 1. Saxena S, Uchida Y, Maze M. Restoring order to postoperative neurocognitive disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75:535‐536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Turan A, Duncan A, Leung S, et al. Dexmedetomidine for reduction of atrial fibrillation and delirium after cardiac surgery (DECADE): a randomised placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2020;396:177‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang D, Su X, Meng Z, et al. Impact of dexmedetomidine on long‐term outcomes after noncardiac surgery in elderly: 3‐year follow‐up of a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2019;270:356‐363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Evered LA, Silbert BS. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and noncardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2018;127:496‐505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kotekar N, Shenkar A, Nagaraj R. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction – current preventive strategies. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:2267‐2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eckenhoff RG, Maze M, Xie Z, et al. Perioperative neurocognitive disorder: state of the preclinical science. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:55‐68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Evered L, Silbert B, Knopman DS, et al. Recommendations for the nomenclature of cognitive change associated with anaesthesia and surgery‐2018. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:1005‐1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th Rev. World Helath Organisation 2016.

- 9. Association AP . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Needham MJ, Webb CE, Bryden DC. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and dementia: what we need to know and do. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:i115‐i125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Daiello LA, Racine AM, Yun Gou R, et al. Postoperative delirium and postoperative cognitive dysfunction: overlap and divergence. Anesthesiology. 2019;131:477‐491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Snyder B, Simone SM, Giovannetti T, Floyd TF. Cerebral hypoxia: its role in age‐related chronic and acute cognitive dysfunction. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:1502‐1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang P, Velagapudi R, Kong C, et al. Neurovascular and immune mechanisms that regulate postoperative delirium superimposed on dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:734‐749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fong TG, Vasunilashorn SM, Gou Y, et al. Association of CSF Alzheimer's disease biomarkers with postoperative delirium in older adults. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2021;7:e12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berger M, Oyeyemi D, Olurinde MO, et al. The INTUIT study: investigating neuroinflammation underlying postoperative cognitive dysfunction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:794‐798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Racine AM, Touroutoglou A, Abrantes T, et al. Older patients with Alzheimer's Disease‐related cortical atrophy who develop post‐operative delirium may be at increased risk of long‐term cognitive decline after surgery. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75:187‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Subramaniyan S, Terrando N. Neuroinflammation and perioperative neurocognitive disorders. Anesth Analg. 2019;128:781‐788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang T, Velagapudi R, Terrando N. Neuroinflammation after surgery: from mechanisms to therapeutic targets. Nat Immunol. 2020;21:1319‐1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guan HL, Liu H, Hu XY, et al. Urinary albumin creatinine ratio associated with postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing elective non‐cardiac surgery: a prospective observational study[published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 20]. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;1‐10. doi: 10.1111/cns.13717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Fu H, Wu Y, et al. Elamipretide (SS‐31) improves functional connectivity in hippocampus and other related regions following prolonged neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide in aged rats. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13: 600484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Raz L, Knoefel J, Bhaskar K. The neuropathology and cerebrovascular mechanisms of dementia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36:172‐186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ronaldson PT, Davis TP. Regulation of blood‐brain barrier integrity by microglia in health and disease: A therapeutic opportunity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2020;40:S6‐S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kan M, Yang T, Fu H, et al. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate prevents neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction after endotoxemia in rats. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang M, Zhang Y, Fu H, Zhang Q, Wang T. Ulinastatin may significantly improve postoperative cognitive function of elderly patients undergoing spinal surgery by reducing the translocation of lipopolysaccharide and systemic inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kristek G, Rados I, Kristek D, et al. Influence of postoperative analgesia on systemic inflammatory response and postoperative cognitive dysfunction after femoral fractures surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019;44:59‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Huang H, Tanner J, Parvataneni H, et al. Impact of total knee arthroplasty with general anesthesia on brain networks: cognitive efficiency and ventricular volume predict functional connectivity decline in older adults. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;62:319‐333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacKenzie KK, Britt‐Spells AM, Sands LP, Leung JM. Processed electroencephalogram monitoring and postoperative delirium: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:417‐427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bocskai T, Kovacs M, Szakacs Z, et al. Is the bispectral index monitoring protective against postoperative cognitive decline? A systematic review with meta‐analysis. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yang S, Xiao W, Wu H, et al. Management based on multimodal brain monitoring may improve functional connectivity and post‐operative neurocognition in elderly patients undergoing spinal surgery. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:705287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhao W, Hu Y, Chen H, et al. The effect and optimal dosage of dexmedetomidine plus sufentanil for postoperative analgesia in elderly patients with postoperative delirium and early postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a single‐center, prospective, randomized, double‐blind, controlled rrial. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:549516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Su X, Meng Z, Wu X, et al. Dexmedetomidine for prevention of delirium in elderly patients after non‐cardiac surgery: a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:1893‐1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhang Y, Shan G, Zhang Y, et al. Propofol compared with sevoflurane general anaesthesia is associated with decreased delayed neurocognitive recovery in older adults. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:595‐604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Subramaniam B, Shankar P, Shaefi S, et al. Effect of intravenous acetaminophen vs placebo combined with propofol or dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium among older patients following cardiac surgery: the DEXACET randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321:686‐696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mu D, Zhang D, Wang D, et al. Parecoxib supplementation to morphine analgesia decreases incidence of delirium in elderly patients after hip or knee replacement surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2017;124:1992‐2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wagner D, Hooper V, Bankieris K, Johnson A. The relationship of postoperative delirium and unplanned perioperative hypothermia in surgical patients. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36:41‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rudiger A, Begdeda H, Babic D, et al. Intra‐operative events during cardiac surgery are risk factors for the development of delirium in the ICU. Crit Care. 2016;20:264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Maheshwari K, Ahuja S, Khanna AK, et al. Association between perioperative hypotension and delirium in postoperative critically ill patients: a retrospective cohort analysis. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:636‐643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Feng X, Hu J, Hua F, Zhang J, Zhang L, Xu G. The correlation of intraoperative hypotension and postoperative cognitive impairment: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol. 2020;20:193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Deiner S, Luo X, Lin HM, et al. Intraoperative infusion of dexmedetomidine for prevention of postoperative delirium and cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing major elective noncardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e171505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Konishi Y, Evered LA, Scott DA, Silbert BS. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction after sevoflurane or propofol general anaesthesia in combination with spinal anaesthesia for hip arthroplasty. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;46:596‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sun H, Zhang G, Ai B, et al. A systematic review: comparative analysis of the effects of propofol and sevoflurane on postoperative cognitive function in elderly patients with lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hovens IB, van Leeuwen BL, Mariani MA, Kraneveld AD, Schoemaker RG. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation; cardiac surgery and abdominal surgery are not the same. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;54:178‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Li Y, Li H, Li H, et al. Delirium in older patients after combined epidural‐general anesthesia or general anesthesia for major surgery: a randomized trial. Anesthesiology. 2021;135:218‐232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jiang P, Li M, Mao AQ, Liu Q, Zhang Y. Effects of general anesthesia combined with epidural anesthesia on cognitive dysfunction and inflammatory markers of patients after surgery for esophageal cancer: a randomised controlled trial. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2021;31:885‐890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ehsani R, Djalali Motlagh S, Zaman B, Sehat Kashani S, Ghodraty MR. Effect of general versus spinal anesthesia on postoperative delirium and early cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients. Anesth Pain Med. 2020;10:e101815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Sprung J, Schulte PJ, Knopman DS, et al. Cognitive function after surgery with regional or general anesthesia: a population‐based study. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1243‐1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Unneby A, Svensson PO, Gustafson PY, Lindgren APB, Bergstrom U, Olofsson PB. Complications with focus on delirium during hospital stay related to femoral nerve block compared to conventional pain management among patients with hip fracture – a randomised controlled trial. Injury. 2020;51:1634‐1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shen Z, Xu H, Song W, et al. Galectin‐1 ameliorates perioperative neurocognitive disorders in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2021;27:842‐856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Montagne A, Barnes SR, Sweeney MD, et al. Blood‐brain barrier breakdown in the aging human hippocampus. Neuron. 2015;85:296‐302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kong J, Du Z, Dong L. Pinitol prevents lipopolysaccharide (LPS)‐induced inflammatory responses in BV2 microglia mediated by TREM2. Neurotox Res. 2020;38:96‐104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dong P, Zhao J, Li N, et al. Sevoflurane exaggerates cognitive decline in a rat model of chronic intermittent hypoxia by aggravating microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation via downregulation of PPAR‐gamma in the hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2018;347:325‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang W, Lu R, Feng D, Zhang H. Sevoflurane inhibits glutamate‐aspartate transporter and glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in hippocampal astrocytes of neonatal rats through the janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:93‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li Y, Zhu Z, Huang T, et al. The peripheral immune response after stroke‐ a double edge sword for blood‐brain barrier integrity. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:1115‐1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xiao J, Xiong B, Zhang W, et al. PGE2‐EP3 signaling exacerbates hippocampus‐dependent cognitive impairment after laparotomy by reducing expression levels of hippocampal synaptic plasticity‐related proteins in aged mice. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:917‐929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jha MK, Jo M, Kim J‐H, Suk K. Microglia‐astrocyte crosstalk: an intimate molecular conversation. Neuroscientist. 2018;25:227‐240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Linnerbauer M, Wheeler MA, Quintana FJ. Astrocyte crosstalk in CNS inflammation. Neuron. 2020;108:608‐622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wei Y, Chen T, Bosco DB, et al. The complement C3–C3aR pathway mediates microglia‐astrocyte interaction following status epilepticus. Glia. 2021;69:1155‐1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Johnson ECB, Dammer EB, Duong DM, et al. Large‐scale proteomic analysis of Alzheimer's disease brain and cerebrospinal fluid reveals early changes in energy metabolism associated with microglia and astrocyte activation. Nat Med. 2020;26:769‐780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kam TI, Hinkle JT, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Microglia and astrocyte dysfunction in Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2020;144: 105028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Subhramanyam CS, Wang C, Hu Q, Dheen ST. Microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative diseases. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;94:112‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kluge MG, Abdolhoseini M, Zalewska K, et al. Spatiotemporal analysis of impaired microglia process movement at sites of secondary neurodegeneration post‐stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2019;39:2456‐2470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jin X, Liu M, Zhang D, et al. Baicalin mitigates cognitive impairment and protects neurons from microglia‐mediated neuroinflammation via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasomes and TLR4/NF‐kappaB signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2019;25:575‐590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Li J, Shi C, Ding Z, Jin W. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta promotes postoperative cognitive dysfunction by inducing the M1 polarization and migration of microglia. Mediators Inflamm. 2020;2020:7860829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Zhu Y, Wang Y, Yao R, et al. Enhanced neuroinflammation mediated by DNA methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor triggers cognitive dysfunction after sevoflurane anesthesia in adult rats subjected to maternal separation during the neonatal period. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Griciuc A, Patel S, Federico AN, et al. TREM2 acts downstream of CD33 in modulating microglial pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2019;103:820–835.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Keren‐Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2017;169:1276–1290.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Jiang Y, Li Z, Ma H, et al. Upregulation of TREM2 ameliorates neuroinflammatory responses and improves cognitive deficits triggered by surgical trauma in Appswe/PS1dE9 mice. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46:1398‐1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Henjum K, Quist‐Paulsen E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Nilsson LNG, Watne LO. CSF sTREM2 in delirium‐relation to Alzheimer's disease CSF biomarkers Abeta42, t‐tau and p‐tau. J Neuroinflammation. 2018;15:304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Zhang L, Xu J, Gao J, Wu Y, Yin M, Zhao W. CD200‐, CX3CL1‐, and TREM2‐mediated neuron‐microglia interactions and their involvements in Alzheimer's disease. Rev Neurosci. 2018;29:837‐848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cho I, Kim JM, Kim EJ, et al. Orthopedic surgery‐induced cognitive dysfunction is mediated by CX3CL1/R1 signaling. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Xu J, Dong H, Qian Q, et al. Astrocyte‐derived CCL2 participates in surgery‐induced cognitive dysfunction and neuroinflammation via evoking microglia activation. Behav Brain Res. 2017;332:145‐153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Butturini E, Boriero D, Carcereri de Prati A, Mariotto S. STAT1 drives M1 microglia activation and neuroinflammation under hypoxia. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2019;669:22‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhao Y, Gan Y, Xu G, Yin G, Liu D. MSCs‐derived exosomes attenuate acute brain injury and inhibit microglial inflammation by reversing CysLT2R‐ERK1/2 mediated microglia M1 polarization. Neurochem Res. 2020;45:1180‐1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lin L, Yihao T, Zhou F, et al. Inflammatory regulation by driving microglial M2 polarization: neuroprotective effects of cannabinoid receptor‐2 activation in intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Immunol. 2017;8:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shi SX, Li YJ, Shi K, Wood K, Ducruet AF, Liu Q. IL (Interleukin)‐15 bridges astrocyte‐microglia crosstalk and exacerbates brain injury following intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:967‐974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Luo Y, Fang Y, Kang R, et al. Inhibition of EZH2 (enhancer of zeste homolog 2) attenuates neuroinflammation via H3k27me3/SOCS3/TRAF6/NF‐kappaB (trimethylation of histone 3 lysine 27/suppressor of cytokine signaling 3/tumor necrosis factor receptor family 6/nuclear factor‐kappaB) in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2020;51:3320‐3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang H, Peng G, Wang B, et al. IL‐1R(‐/‐) alleviates cognitive deficits through microglial M2 polarization in AD mice. Brain Res Bull. 2020;157:10‐17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zabala A, Vazquez‐Villoldo N, Rissiek B, et al. P2X4 receptor controls microglia activation and favors remyelination in autoimmune encephalitis. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:e8743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Hu L, Zhang S, Wen H, et al. Melatonin decreases M1 polarization via attenuating mitochondrial oxidative damage depending on UCP2 pathway in prorenin‐treated microglia. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Litvinchuk A, Wan YW, Swartzlander DB, et al. Complement C3aR inactivation attenuates tau pathology and reverses an immune network deregulated in tauopathy models and Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2018;100:1337–1353.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chen T, Lennon VA, Liu YU, et al. Astrocyte‐microglia interaction drives evolving neuromyelitis optica lesion. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:4025‐4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li D, Chen M, Meng T, Fei J. Hippocampal microglial activation triggers a neurotoxic‐specific astrocyte response and mediates etomidate‐induced long‐term synaptic inhibition. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sinha A, Katyal S, Kauppinen TM. PARP‐DNA trapping ability of PARP inhibitors jeopardizes astrocyte viability: Implications for CNS disease therapeutics. Neuropharmacology. 2021;187:108502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Szabo I, Varga VE, Dvoracsko S, et al. N, N‐Dimethyltryptamine attenuates spreading depolarization and restrains neurodegeneration by sigma‐1 receptor activation in the ischemic rat brain. Neuropharmacology. 2021;192:108612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Liddelow SA, Guttenplan KA, Clarke LE, et al. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature. 2017;541:481‐487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Pekny M, Wilhelmsson U, Tatlisumak T, Pekna M. Astrocyte activation and reactive gliosis‐a new target in stroke? Neurosci Lett. 2019;689:45‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Fu H, Yang T, Xiao W, et al. Prolonged neuroinflammation after lipopolysaccharide exposure in aged rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Xu X, Zhang A, Zhu Y, et al. MFG‐E8 reverses microglial‐induced neurotoxic astrocyte (A1) via NF‐κB and PI3K‐Akt pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234:904‐914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Li T, Liu T, Chen X, et al. Microglia induce the transformation of A1/A2 reactive astrocytes via the CXCR7/PI3K/Akt pathway in chronic post‐surgical pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ryu KY, Lee HJ, Woo H, et al. Dasatinib regulates LPS‐induced microglial and astrocytic neuroinflammatory responses by inhibiting AKT/STAT3 signaling. J Neuroinflammation. 2019;16:190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhou Y, Wu X, Ye L, et al. Edaravone at high concentrations attenuates cognitive dysfunctions induced by abdominal surgery under general anesthesia in aged mice. Metab Brain Dis. 2020;35:373‐383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Liu H, Wu X, Luo J, et al. Adiponectin peptide alleviates oxidative stress and NLRP3 inflammasome activation after cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury by regulating AMPK/GSK‐3beta. Exp Neurol. 2020;329:113302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Balkaya M, Kim ID, Shakil F, Cho S. CD36 deficiency reduces chronic BBB dysfunction and scar formation and improves activity, hedonic and memory deficits in ischemic stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41:486‐501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Ji RR, Donnelly CR, Nedergaard M. Astrocytes in chronic pain and itch. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019;20:667‐685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron. 2016;89:37‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Liu J, Shen Q, Zhang H, et al. The potential protective effect of mesencephalic astrocyte‐derived neurotrophic factor on post‐operative delirium via inhibiting inflammation and microglia activation. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:2781‐2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Stobart JL, Ferrari KD, Barrett MJP, et al. Cortical circuit activity evokes rapid astrocyte calcium signals on a similar timescale to neurons. Neuron. 2018;98:726‐735.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Yu X, Taylor AMW, Nagai J, et al. Reducing astrocyte calcium signaling in vivo alters striatal microcircuits and causes repetitive behavior. Neuron. 2018;99(1170–1187):e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Corkrum M, Covelo A, Lines J, et al. Dopamine‐evoked synaptic regulation in the nucleus accumbens requires astrocyte activity. Neuron. 2020;105(1036–1047):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Stogsdill JA, Ramirez J, Liu D, et al. Astrocytic neuroligins control astrocyte morphogenesis and synaptogenesis. Nature. 2017;551:192‐197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ribot J, Breton R, Calvo CF, et al. Astrocytes close the mouse critical period for visual plasticity. Science. 2021;373:77‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Barbar L, Jain T, Zimmer M, et al. CD49f is a novel marker of functional and reactive human iPSC‐derived astrocytes. Neuron. 2020;107:436‐453.e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Gruol DL, Huitron‐Resendiz S, Roberts AJ. Altered brain activity during withdrawal from chronic alcohol is associated with changes in IL‐6 signal transduction and GABAergic mechanisms in transgenic mice with increased astrocyte expression of IL‐6. Neuropharmacology. 2018;138:32‐46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Hatakeyama N, Unekawa M, Murata J, et al. Differential pial and penetrating arterial responses examined by optogenetic activation of astrocytes and neurons. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41:2676‐2689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Jantas D, Lech T, Golda S, Pilc A, Lason W. New evidences for a role of mGluR7 in astrocyte survival: possible implications for neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology. 2018;141:223‐237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Dzamba D, Honsa P, Anderova M. NMDA receptors in glial cells: pending questions. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2013;11:250‐262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ioannou MS, Jackson J, Sheu SH, et al. Neuron‐astrocyte metabolic coupling protects against activity‐induced fatty acid toxicity. Cell. 2019;177:1522‐1535.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Vasek MJ, Garber C, Dorsey D, et al. A complement‐microglial axis drives synapse loss during virus‐induced memory impairment. Nature. 2016;534:538‐543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Feng X, Valdearcos M, Uchida Y, Lutrin D, Maze M, Koliwad SK. Microglia mediate postoperative hippocampal inflammation and cognitive decline in mice. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e91229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Elmore MRP, Hohsfield LA, Kramar EA, et al. Replacement of microglia in the aged brain reverses cognitive, synaptic, and neuronal deficits in mice. Aging Cell. 2018;17:e12832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Willis EF, MacDonald KPA, Nguyen QH, et al. Repopulating microglia promote brain repair in an IL‐6‐dependent manner. Cell. 2020;180:833‐846.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Quan C, Chen J, Luo Y, et al. BIS‐guided deep anesthesia decreases short‐term postoperative cognitive dysfunction and peripheral inflammation in elderly patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Chen Y, Lu S, Wu Y, et al. Change in serum level of interleukin 6 and delirium after coronary artery bypass graft. Am J Crit Care. 2019;28:462‐470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Zhu B, Sun D, Yang L, Sun Z, Feng Y, Deng C. The effects of neostigmine on postoperative cognitive function and inflammatory factors in elderly patients – a randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Hutton HL, Ooi JD, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR. The NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney disease and autoimmunity. Nephrology. 2016;21:736‐744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Mold C, Kingzette M, Gewurz H. C‐reactive protein inhibits pneumococcal activation of the alternative pathway by increasing the interaction between factor H and C3b. J Immumol. 1984;133:882‐885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Hickman S, Izzy S, Sen P, Morsett L, El Khoury J. Microglia in neurodegeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1359‐1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Van Hulle C, Jonaitis EM, Betthauser TJ, et al. An examination of a novel multipanel of CSF biomarkers in the Alzheimer's disease clinical and pathological continuum. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17:431‐445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Hov KR, Bolstad N, Idland AV, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid S100B and Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in hip fracture patients with delirium. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2017;7:374‐385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Hassan WF, Tawfik MH, Nabil TM, Abd Elkareem RM. Could intraoperative magnesium sulphate protect against postoperative cognitive dysfunction? Minerva Anestesiol. 2020;86:808‐815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Franzmeier N, Suarez‐Calvet M, Frontzkowski L, et al. Higher CSF sTREM2 attenuates ApoE4‐related risk for cognitive decline and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurodegener. 2020;15:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Ballweg T, White M, Parker M, et al. Association between plasma tau and postoperative delirium incidence and severity: a prospective observational study. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126:458‐466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Kreisl WC, Kim M‐J, Coughlin JM, Henter ID, Owen DR, Innis RB. PET imaging of neuroinflammation in neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:940‐950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Bassett DS, Sporns O. Network neuroscience. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:353‐364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Passamonti L, Tsvetanov KA, Jones PS, et al. Neuroinflammation and functional connectivity in Alzheimer's disease: interactive influences on cognitive performance. J Neurosci. 2019;39:7218‐7226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Franzmeier N, Rubinski A, Neitzel J, et al. Functional connectivity associated with tau levels in ageing, Alzheimer's, and small vessel disease. Brain. 2019;142:1093‐1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Mu Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, et al. Amplitude of low‐frequency fluctuations on Alzheimer's disease with depression: evidence from resting‐state fMRI. Gen Psychiatr. 2020;33:e100147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Zhuang L, Ni H, Wang J, et al. Aggregation of vascular risk factors modulates the amplitude of low‐frequency fluctuation in mild cognitive impairment patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020;12:604246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Parisot S, Ktena SI, Ferrante E, et al. Disease prediction using graph convolutional networks: application to autism spectrum disorder and Alzheimer's disease. Med Image Anal. 2018;48:117‐130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Nir T, Jacob Y, Huang KH, et al. Resting‐state functional connectivity in early postanaesthesia recovery is characterised by globally reduced anticorrelations. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:529‐538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Browndyke JN, Berger M, Harshbarger TB, et al. Resting‐state functional connectivity and cognition after major cardiac surgery in older adults without preoperative cognitive impairment: preliminary findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65:e6‐e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. He HW, Zhang H. The efficacy of different doses of ulinastatin in the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:730‐737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Duan M, Liu F, Fu H, Feng S, Wang X, Wang T. Effect of ulinastatin on early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing surgery: a systemic review and meta‐analysis. Front Neurosci. 2021;15: 618589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Li S, Dai Q, Zhang S, et al. Ulinastatin attenuates LPS‐induced inflammation in mouse macrophage RAW264.7 cells by inhibiting the JNK/NF‐κB signaling pathway and activating the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39:1294‐1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Lagoo JY, D'Souza MC, Kartha A, Kutappa AM. Role of Ulinastatin, a trypsin inhibitor, in severe acute pancreatitis in critical care setting: a retrospective analysis. J Crit Care. 2018;45:27‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Yuan D, Liu Z, Kaindl J, et al. Activation of the alpha2B adrenoceptor by the sedative sympatholytic dexmedetomidine. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16:507‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Duan X, Coburn M, Rossaint R, Sanders RD, Waesberghe JV, Kowark A. Efficacy of perioperative dexmedetomidine on postoperative delirium: systematic review and meta‐analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:384‐397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Li R, Lai IK, Pan JZ, Zhang P, Maze M. Dexmedetomidine exerts an anti‐inflammatory effect via alpha2 adrenoceptors to prevent lipopolysaccharide‐induced cognitive decline in mice. Anesthesiology. 2020;133:393‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Zhang X, Yan F, Feng J, et al. Dexmedetomidine inhibits inflammatory reaction in the hippocampus of septic rats by suppressing NF‐kappaB pathway. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Zhai Y, Zhu Y, Liu J, et al. Dexmedetomidine post‐conditioning alleviates cerebral ischemia‐reperfusion injury in rats by inhibiting high mobility group protein B1 group (HMGB1)/toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4)/nuclear factor kappa B (NF‐kappaB) signaling pathway. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e918617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Hughes CG, Boncyk CS, Culley DJ, et al. American society for enhanced recovery and perioperative quality initiative joint consensus statement on postoperative delirium prevention. Anesth Analg. 2020;130:1572‐1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Huang JM, Lv ZT, Zhang B, Jiang WX, Nie MB. Intravenous parecoxib for early postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients: evidence from a meta‐analysis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2020;13:451‐460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Tufvesson‐Alm M, Schwieler L, Schwarcz R, Goiny M, Erhardt S, Engberg G. Importance of kynurenine 3‐monooxygenase for spontaneous firing and pharmacological responses of midbrain dopamine neurons: relevance for schizophrenia. Neuropharmacology. 2018;138:130‐139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Li Z, Cao X, Ma H, et al. Surgical trauma exacerbates cognitive deficits and neuroinflammation in aged rats: the role of CX3CL1‐CX3CR1 signaling. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77:736‐746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Ni J, Xiao S, Li X, Sun L. ACE gene missense mutation in a case with early‐onset, rapid progressing dementia. Gen Psychiatr. 2019;32:e100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Guo X, Mao R, Cui L, et al. PAID study design on the role of PKC activation in immune/inflammation‐related depression: a randomised placebo‐controlled trial protocol. Gen Psychiatr. 2021;34:e100440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Corraini P, Henderson VW, Ording AG, Pedersen L, Horvath‐Puho E, Sorensen HT. Long‐term risk of dementia among survivors of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. Stroke. 2017;48:180‐186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Hack RJ, Rutten JW, Person TN, et al. Cysteine‐altering NOTCH3 variants are a risk factor for stroke in the elderly population. Stroke. 2020;51:3562‐3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Shaw R, Drozdowska B, Taylor‐Rowan M, et al. Delirium in an acute stroke setting, occurrence, and risk factors. Stroke. 2019;50:3265‐3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Evered L, Silbert B, Scott DA, Ames D, Maruff P, Blennow K. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarker for Alzheimer disease predicts postoperative cognitive dysfunction. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:353‐361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

This is a review article and all the references have been published online.