Abstract

Background

Chronic anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) prevents ischaemic stroke and systemic embolism in people with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) but dose adjustment, coagulation monitoring and bleeding limits its use. Direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) are under investigation as potential alternatives.

Objectives

To assess (1) the comparative efficacy of long‐term anticoagulation using DTIs versus VKAs on vascular deaths and ischaemic events in people with non‐valvular AF, and (2) the comparative safety of chronic anticoagulation using DTIs versus VKAs on (a) fatal and non‐fatal major bleeding events including haemorrhagic strokes, (b) adverse events other than bleeding and ischaemic events that lead to treatment discontinuation and (c) all‐cause mortality in people with non‐valvular AF.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (July 2013), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), (The Cochrane Library, May 2013), MEDLINE (1950 to July 2013), EMBASE (1980 to October 2013), LILACS (1982 to October 2013) and trials registers (September 2013). We also searched the websites of clinical trials and pharmaceutical companies and handsearched the reference lists of articles and conference proceedings.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing DTIs versus VKAs for prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in people with non‐valvular AF.

Data collection and analysis

All three review authors independently performed data extraction and assessment of risk of bias. Primary analyses compared all DTIs combined versus warfarin. We performed post hoc analyses excluding ximelagatran because this drug was withdrawn from the market owing to safety concerns.

Main results

We included eight studies involving a total of 27,557 participants with non‐valvular AF and one or more risk factors for stroke; 26,601 of them were assigned to standard doses groups and included in the primary analysis. The DTIs: dabigatran 110 mg twice daily and 150 mg twice daily (three studies, 12,355 participants), AZD0837 300 mg once per day (two studies, 233 participants) and ximelagatran 36 mg twice per day (three studies, 3726 participants) were compared with the VKA warfarin (10,287 participants). Overall risk of bias and statistical heterogeneity of the studies included were low.

The odds of vascular death and ischaemic events were not significantly different between all DTIs and warfarin (odds ratio (OR) 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 1.05). Sensitivity analysis by dose of dabigatran on reduction in ischaemic events and vascular mortality indicated that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin although the effect estimate was of borderline statistical significance (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99). Sensitivity analyses by other factors did not alter the results. Fatal and non‐fatal major bleeding events, including haemorrhagic strokes, were less frequent with the DTIs (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.97). Adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment were significantly more frequent with the DTIs (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.82 to 2.61). All‐cause mortality was similar between DTIs and warfarin (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01).

Authors' conclusions

DTIs were as efficacious as VKAs for the composite outcome of vascular death and ischaemic events and only the dose of dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was found to be superior to warfarin. DTIs were associated with fewer major haemorrhagic events, including haemorrhagic strokes. Adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment occurred more frequently with the DTIs. We detected no difference in death from all causes.

Plain language summary

Direct thrombin inhibitors compared with vitamin K antagonists in people with atrial fibrillation for preventing stroke

Question: We wanted to compare the effectiveness and safety of direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) with vitamin K antagonists in people with atrial fibrillation (AF) to prevent stroke.

Background: Non‐valvular atrial fibrillation is a type of irregular heartbeat that arises in a heart with normal valves. It increases the risk of developing blood clots in the heart which can then travel to the brain, leading to a stroke, and to other parts of the body. Warfarin (a vitamin K antagonist) is a drug that prevents the formation of such clots, thus reducing the risk of stroke. However, the need for frequent blood tests to adjust the dose and the risk of bleeding limits the use of warfarin. The oral DTIs represent a potential alternative. We aimed to establish the comparative effectiveness and safety of these new drugs compared with the standard treatment (warfarin) used for long‐term anticoagulation in people with AF.

Study characteristics: We included eight studies, identified up to October 2013, evaluating the effect of DTIs versus warfarin in people with non‐valvular AF. DTIs included were dabigatran 110 mg or 150 mg twice daily (three studies, 12,355 participants), AZD0837 300 mg once a day (two studies, 233 participants) and ximelagatran 36 mg twice daily (three studies, 3726 participants). Of the total number of participants included in this review 61% were men, and the mean age of participants in all studies was over 70 years. Follow‐up periods after the end of study medication ranged from zero to four weeks.

Key results: We conducted the analyses excluding ximelagatran because this drug was withdrawn from the market owing to toxic effects on the liver. We evaluated the effectiveness of the treatment by the number of vascular deaths and ischaemic events. We evaluated safety by the number of (1) fatal and non‐fatal major bleeding events, including haemorrhagic strokes, (2) adverse events other than bleeding and ischaemic events that led to treatment discontinuation, and (3) death from all causes.

There was no difference in the number of vascular deaths and ischaemic events between all DTIs combined and warfarin, although dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin for this outcome. Major bleeding events were less frequent with the DTIs, making them a potentially safer alternative to anticoagulation in people at high risk. The adverse events that led participants to discontinue treatment were more frequent with the DTIs. Death from all causes was similar between DTIs and warfarin.

Quality of the evidence: We judged the quality of all eight included studies to be adequate to address the main objectives of the review.

Background

Non‐valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) is estimated to affect fewer than 1% of individuals below 50 years of age, increasing to 23.5% in people over 80 years of age (Benjamin 1998). Among people with AF, 76% have a moderate to high risk of stroke (Singer 2008). Dose‐adjusted warfarin reduces this risk by 62% compared with placebo but increases the risk of intracranial bleeding (Hart 2007). Direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) constitute a new class of oral anticoagulants under investigation (Fuster 2006; Squizzato 2009; Weitz 2003).

Description of the condition

AF is a cardiac arrhythmia caused by multiple re‐entrant waveforms within the atria of the heart, which impairs atrial contraction. The resulting left atrial stasis can promote thrombus formation and subsequent embolic events including stroke and systemic embolism (Ferro 2004; Kimura 2005). AF increases the risk of stroke four to five times in all age groups (Friberg 2004; Wolf 1987). Without anticoagulation therapy, the stroke rate among people with AF can vary from 1.9% to 18% per year, depending on individual characteristics (CHADS₂ score) (Gage 2004).

Description of the intervention

DTIs belong to a new class of anticoagulants that were developed as potential alternatives to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for chronic anticoagulation in people with non‐valvular AF (Kirchhof 2007). DTIs offer fixed oral dosing without the need for coagulation monitoring, as well as rapid onset of action and stable pharmacokinetics with little potential for drug interactions (Baetz 2008; Pengo 2004). Ximelagatran was the first oral DTI to be used clinically but it was withdrawn from the market due to liver toxicity (Albers 2006; Boudes 2006; EMEA 2006). Dabigatran etexilate is a DTI that was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in October 2010 for stroke prevention in people with non‐valvular AF. Dabigatran reaches its plasmatic peak and begins its anticoagulant action between half an hour and two hours after oral administration (Baetz 2008). It is primarily eliminated by the kidneys and it is not metabolised by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system in the liver, which yields a better drug interaction profile (Fareed 2012). AZD0837 is another oral DTI under investigation, not yet licensed for clinical use.

How the intervention might work

Thrombin has a central role in thrombogenesis. DTIs act by interfering with the final step of the coagulation cascade, namely, the conversion of fibrinogen to insoluble fibrin by thrombin.

Why it is important to do this review

Although there is much experience with VKA treatment, it has several disadvantages including its narrow therapeutic index and wide variability of anticoagulation intensity, which requires frequent dose adjustments (Go 2003; Rose 2008). Despite regular monitoring, 30% to 50% of the time the international normalised ratio (INR) values fall outside the therapeutic target range (Jones 2005). Moreover, the risk of bleeding remains a pivotal concern with warfarin therapy, particularly among the elderly (Oldgren 2011). These limitations result in undertreatment of a considerable proportion of people with AF who remain at high risk for stroke (Frykman 2001) and create a need for safer and more convenient alternatives. In this context, the evaluation of the efficacy and safety of the new DTIs is of critical importance.

Objectives

To assess (1) the comparative efficacy of long‐term anticoagulation using DTIs versus VKAs on vascular deaths and ischaemic events in people with non‐valvular AF, and (2) the comparative safety of long‐term anticoagulation using DTIs versus VKAs on (a) fatal and non‐fatal major bleeding events including haemorrhagic strokes, (b) adverse events other than bleeding and ischaemic events that lead to treatment discontinuation, and (c) all‐cause mortality in people with non‐valvular AF.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing anticoagulation with direct thombin inhibitors (DTIs) versus vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in people with non‐valvular AF.

Types of participants

People with non‐valvular AF and one or more risk factors for stroke.

Types of interventions

Administration of DTIs at standard doses (dabigatran 110 mg twice daily and 150 mg twice daily, AZD0837 300 mg twice daily and ximelagatran 36 mg twice daily) compared with VKAs (adjusted‐dose warfarin) for an INR between 2 and 3.

Both doses of dabigatran included in this review are available for clinical use. The dose of dabigatran 150 mg twice daily has been approved by the FDA for preventing stroke in people with non‐valvular AF (Beasley 2011). The European Society of Cardiology recommends both dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and dabigatran 110 mg twice daily for people at low and high risk of bleeding respectively (Camm 2009). The dose of ximelagatran 36 mg twice daily was commercially available until 2006 when it was withdrawn from the market owing to safety concerns. We chose to include the dose of AZD0837 300 mg twice daily even though it has not yet been licensed because in the analysis of individual doses it appeared to have the best efficacy and safety profile among the different tested doses.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The composite outcome of vascular deaths and ischaemic events, including non‐fatal ischaemic strokes and transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs), non‐fatal systemic embolic events (SEE) and non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI). Vascular death is defined as any death related to a vascular cause not including fatal haemorrhages or cardiovascular deaths (e.g. sudden arrhythmia, pump failure). Systemic embolism is defined as any event of acute non‐intracerebral or non‐coronary vascular origin including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

The composite outcome of fatal or non‐fatal major bleeding events, including haemorrhagic strokes. We did not include minor bleeding events.

Secondary outcomes

Fatal or non‐fatal adverse events other than haemorrhage and ischaemic events that lead to discontinuation of treatment.

Death from all causes during treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

See the 'Specialized register' section in the Cochrane Stroke Group module. We searched for relevant trials in all languages and, where necessary, arranged translation of trial reports published in languages other than English or Spanish.

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Register (last searched July 2013). In addition, we searched the following electronic databases: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, May 2013, Issue 5) (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Ovid) (1950 to July 2013) (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Ovid) (1980 to October 2013) (Appendix 3), and LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature) (1982 to October 2013) (Appendix 4). We also searched ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov), Current Controlled Trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), TrialResults‐center (www.trialresultscenter.org), Stroke Trials Directory (www.strokecenter.org/trials) and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/) (last searched September 2013).

We developed the search strategies for MEDLINE, EMBASE and CENTRAL with the help of the Cochrane Stroke Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator and adapted the MEDLINE search strategy for the other databases.

Searching other resources

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials we:

screened the reference lists of relevant articles;

identified and handsearched the following relevant journals and the proceedings of relevant conferences (last search: September 2013): Congresses of the European Society of Cardiology, Scientific sessions of the American Heart Association, Heart Rhythm Society and Annual Meeting of the American College of Cardiology;

reviewed the websites of the following pharmaceutical companies for clinical trial results: AstraZeneca (www.astrazenecaclinicaltrials.com) and Boehringer‐Ingelheim (www.boehringer‐ingelheim.com).

Data collection and analysis

All three review authors screened the records obtained from the electronic searches and excluded obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained the full text of the remaining papers and the same three authors selected trials for inclusion based on the selection criteria described previously. We arranged translation of titles and abstracts of articles in languages other than English or Spanish, and if the title and the abstract potentially met the inclusion criteria we had the entire text of the article translated. We resolved any disagreements through discussion and consensus.

Selection of studies

All three review authors independently assessed eligibility of studies based on prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteria. We resolved disagreements by discussion and consensus. We listed studies excluded at the full‐text review stage along with the reasons for exclusion. See the study flow chart (Figure 1).

Data extraction and management

All three review authors independently extracted data using predesigned abstraction forms. We verified these forms to ensure that all relevant data were included. We compared the abstraction forms with each other to ensure reproducibility between abstractors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

All three review authors independently assessed the methodological quality of each included study using the domain‐based evaluation tool described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Quality criteria consisted of (1) random sequence generation, (2) allocation concealment, (3) blinding of participants and personnel (4) blinding of outcome assessment (5) incomplete outcome data addressed, (6) selective reporting and (7) other potential biases. Each author issued a judgement of risk (low, high or uncertain) for each quality criterion. When a rating of high or low would not have been feasible or prudent, we assigned a grade of unclear. We resolved disagreements by discussion. We addressed publication bias using graphical statistics such as funnel plots. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Measures of treatment effect

The outcomes were binary and we summarised the dichotomous data using odds ratios (ORs). Results are presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

The included RCTs had a simple parallel group design. In this design, the participants are individually randomised to either the intervention group (DTIs) or the control group (VKAs) and we collected and analysed a single measurement for each outcome from each participant. For phase II studies including multiple treatment arms with different doses of the DTIs, we selected the data from the treatment arm using the standard or intermediate doses. See Types of interventions.

Dealing with missing data

We complemented data from the final report of included studies with: (1) protocol descriptions (e.g. rationale and design articles), (2) clinical trial registers, (3) editorials and subanalyses of main studies, and (4) FDA briefing documents. If the missing data could not be obtained, then we analysed the available data and noted any assumptions made. We carefully considered missing data when evaluating potential biases and in the interpretation of results.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistical test (Higgins 2003) to ascertain heterogeneity among studies. The I² is expressed as a percentage, and describes the proportion of variability that is due to heterogeneity rather than to sampling error. We categorised heterogeneity as follows: low (I² values less than 25%), moderate (I² above 25% but less than 50%) and high (I² between 50% and 75%).

Assessment of reporting biases

We performed a comprehensive search for published, unpublished and ongoing studies that met our eligibility criteria. The evaluation of methodological quality of included studies comprised the assessment of selective reporting.

Data synthesis

We used either fixed‐effect or random‐effects models to synthesise the evidence quantitatively, depending on the heterogeneity across studies. For an analysis with low heterogeneity we planned to use a fixed‐effect meta‐analysis. Conversely, for moderate or high heterogeneity we planned to use a random‐effects meta‐analysis. Finally, if the combination of studies resulted in very high heterogeneity (greater than 75%), we did not perform a combined analysis.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Other than the analysis of grouped and individual doses described in the Sensitivity analysis section, we could not undertake the subgroup analyses prespecified in the protocol due to insufficient data. See Differences between protocol and review.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed the following sensitivity analyses:

re‐analysis of data using a different statistical approach (random‐effects instead of fixed‐effect and vice versa);

different doses of DTIs: all tested doses grouped and isolated.

Post hoc sensitivity analyses included:

excluding the studies of ximelagatran;

evaluating each drug independently;

excluding myocardial infarction (MI) from the primary efficacy outcome.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

Results of the search

We obtained 1025 records through the searches of the electronic databases and 89 additional references from other sources. After removing duplicate records, we screened 1074 records by title and abstract. We excluded 1042 records as not relevant. We obtained the full text of the remaining 32 papers and of these we excluded 24. Eight studies are included in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis (Lip 2009; Olsson 2010; PETRO 2007; RE‐LY 2009; SPORTIF II 2003; SPORTIF III 2003; SPORTIF V 2005; NCT01136408). We did not identify any ongoing trials. The flow diagram describing the search process, selection and exclusion is shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We identified eight randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that met the eligibility criteria, which included a total of 27,557 participants, 26,601 of whom were assigned to standard doses groups and included in the primary analysis. The direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) dabigatran 110 mg twice daily and 150 mg twice daily (three studies, 12,355 participants), AZD0837 300 mg once daily (two studies, 233 participants) and ximelagatran 36 mg twice daily (three studies, 3726 participants) were compared to the vitamin K antagonist (VKA) warfarin (10,287 participants). RE‐LY 2009 represented 66% of the total population. Three RCTs used dabigatran etexilate (NCT01136408; PETRO 2007; RE‐LY 2009). Two RCTs used AZD0837: Lip 2009 used an extended‐release form and Olsson 2010 used immediate‐release pills. Three RCTs used ximelagatran (SPORTIF II 2003; SPORTIF III 2003; SPORTIF V 2005). Three included studies were phase III RCTs designed to assess efficacy and safety (RE‐LY 2009; SPORTIF III 2003; SPORTIF V 2005), while the remaining five were phase II RCTs that evaluated tolerability and safety of different dosages (Lip 2009; NCT01136408; Olsson 2010; PETRO 2007; SPORTIF II 2003).These latter studies also reported events that were included in the efficacy analysis. All studies were funded by the pharmaceutical industry.

From the total number of participants included in this review, 61% were men and the mean age of participants in all studies was over 70 years. The rate of VKA‐naϊve participants (never previously exposed to VKAs) was approximately 50% (range 5% to 100%). The average CHADS₂ score was 2.1 except for PETRO 2007 in which the average score was 3. The studies of ximelagatran did not report CHADS₂ scores. In the groups assigned to warfarin, the international normalised ratio (INR) was maintained within the therapeutic range between 57% and 71% of the time. In five studies (Lip 2009; Olsson 2010; PETRO 2007; RE‐LY 2009; SPORTIF II 2003) the different doses of DTIs were administered in a double‐blind modality whereas warfarin was given openly. NCT01136408 and SPORTIF III 2003 were open‐label for both the DTI and warfarin. SPORTIF V 2005 used a double‐dummy design to blind the administration of both the intervention and the control drug. In PETRO 2007, the three doses of dabigatran used (50, 150, and 300 mg twice daily) were combined in a 3 x 3 factorial fashion with no aspirin, 81 mg or 325 mg aspirin once daily. Aspirin was given openly.

The studies planned outcome assessment over 2.8 to 24 months for dabigatran, three to 4.7 months for AZD0837 and three to 20 months for ximelagatran. Follow‐up periods after discontinuation of study medication ranged from zero to four weeks.

Excluded studies

We excluded a total of 24 studies. We excluded 15 studies because they studied populations other than people with AF (e.g. healthy individuals, people with DVT, with mechanical heart valves, haemodialysis, people undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention, people with acute coronary syndrome) (BISTRO 2005; Eikelboom 2013; Eriksson 2007; ESTEEM 2003; NCT01225822; NCT00152971; NCT00246025; NCT00680186; ; RE‐ALIGN 2012; RECOVER 2009; REDEEM 2011; REMODEL 2007; RENOVATE 2011; Schulman 2013; Vranckx 2013). We excluded six studies (ACTIVE 2006; Amadeus Investig 2008; ARISTOTLE 2011; ENGAGE AF 2010; EXPLORE Xa 2013; ROCKET 2011) because they did not use a DTI as the intervention. We excluded one study for not using warfarin as the comparison (NCT00904800). The international multicentre RELY ABLE 2012 study followed 5851 participants on dabigatran for a further 28 months after completion of RE‐LY 2009. We excluded this study because it had no comparison group and participants randomised to warfarin in the original study were not eligible for inclusion. Moreover, participants continuing in RELY ABLE 2012 differed in several respects from those who did not: continuing participants were less likely to have permanent AF, less likely to have heart failure and less likely to have had a major clinical event during the original study. SPORTIF IV 2006 is a long‐term follow‐up study of people who participated in SPORTIF II 2003. It was stopped prematurely following an adverse event report of serious liver injury in the EXTEND clinical trial. We excluded the SPORTIF IV 2006 study owing to methodological concerns as it introduced significant bias: only people completing the first and seventh visit of SPORTIF II 2003 were eligible for the study, outcome assessment lost blinding and all three different dose arms were combined into a single dose of ximelagatran 36 mg bid and analysed together.

Risk of bias in included studies

See Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

2.

Funnel plot of comparison: Efficacy outcome: Vascular deaths plus ischaemic events

3.

Funnel plot of comparison: Safety outcome: Fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages

4.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

5.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Seven of the included studies achieved randomisation sequence through a computerised interactive system, and three of them maintained the allocation concealment in the same way. Olsson 2010, PETRO 2007 and SPORTIF V 2005 trials did not mention how allocation concealment was maintained after the randomisation. NCT01136408 did not specify how the randomisation sequence or allocation concealment was done.

Blinding

Participants taking warfarin needed constant INR monitoring. Therefore, blinding of both intervention and control groups was not done in most studies. However, the different doses of DTI were blinded to the physician and to the participant. Only SPORTIF V 2005 used a double‐dummy design to maintain blinding of both DTI and warfarin. NCT01136408 and SPORTIF III 2003 were open‐label for both intervention and control groups. In RE‐LY 2009, PETRO 2007, SPORTIF II 2003, SPORTIF III 2003 and SPORTIF V 2005 endpoint adjudication was done by an independent committee blinded to treatment status following the PROBE design in an effort to compensate for open warfarin.

Incomplete outcome data

RE‐LY 2009 showed a rate of discontinuation of treatment of 19.6% and 15% in the dabigatran and warfarin groups respectively. The reasons for discontinuation were uncertain for 208 participants in the dabigatran group and 200 in the warfarin group. This study reported that only 20 (0.11%) participants interrupted follow‐up. In SPORTIF II 2003 47 (18.2%) participants discontinued assigned treatment prematurely. Reasons for discontinuation remained uncertain in 24 participants. SPORTIF III 2003 reported premature discontinuation of study treatment in 309 (18%) participants in the ximelagatran group and 246 (14%) participants in the warfarin group. The reasons for discontinuation were uncertain for 125 participants in the ximelagatran group and 124 in the warfarin group. In this study interrupted follow‐up was seen in 138 (4%) participants. Status could not be ascertained in 18 of 78 participants assigned to ximelagatran and 17 of 60 participants assigned to warfarin. SPORTIF V 2005 reported that 37% and 33% discontinued treatment prematurely in the ximelagatran and warfarin groups respectively. This study reported a total of 226 (6%) participants who interrupted follow‐up. Status remained uncertain for 23 of them. Lip 2009 also had a significant percentage of discontinuation of treatment in the DTI group (16.8%) compared with that of the warfarin group (7.9%). However, the overall follow‐up interruption was less than 10% (8.9% for AZD0837 and 4.7% for warfarin). The treatment discontinuation percentages in the other studies were: Olsson 2010: 6.4% and PETRO 2007: 7.5%. NCT01136408 did not report the number of discontinuations.

Reported outcomes in RE‐LY 2009 were complemented with data from a RE‐LY update publication, Conolly 2010 (included in the RE‐LY 2009 references), which reported additional primary efficacy outcome events recorded during routine clinical site closure visits after the database was locked. Additionally, we used data from a briefing document submitted to the FDA by Boehringer Ingelheim, Pharmaceuticals Boehringer Ingelheim 2010 (included in the RE‐LY 2009 references) to obtain the exact number of individual outcomes included in composite endpoints.

We made assumptions when missing data could not be obtained and when reported outcomes left room for interpretation. All assumptions followed unified criteria across studies and were made before the pooled analysis was carried out. These are detailed as follows:

Dabigatran studies

502 participants were randomised, 13 of whom were included twice in the safety analysis of the study owing to a change in their aspirin dose, reaching a total of 515 participants analysed. In our security analysis, we only included the 502 initially randomised participants.

Two deaths in the dabigatran group were reported in the study report on the pharmaceutical company website: one of them was due to heart failure and the other was due to mesenteric ischaemia. Neither is mentioned in the published report. We included both deaths in our analysis as death from all causes. We did not include the death attributed to systemic embolism in the efficacy analysis because we could not elucidate the dosage arm to which it belonged.

One participant had a peripheral embolism and an ischaemic stroke, which counted as two separate events in our efficacy analysis.

We included the number of strokes with uncertain classifications (seven for dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, nine for dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and 10 for warfarin) in the primary efficacy outcome.

We included both clinical and silent MI in the primary analysis.

We included deaths classified as vascular from unknown causes (46 for dabigatran 110 mg twice daily, 41 for dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and 46 for warfarin) as vascular deaths.

We considered a participant who presented with an ischaemic stroke with haemorrhagic conversion only as an ischaemic event.

AZD0837 studies

We counted clinically relevant bleeding events in the safety analysis.

One participant in the warfarin group presented one major bleeding and one clinically relevant bleeding, which we considered as two different events in our safety analysis.

We considered one death due to haemorrhage after a skull fracture as a death from other causes.

We included a participant with MI, considered as an adverse event by the study authors, in the efficacy analysis. A participant who died of sudden chest pain and for whom an autopsy was not performed is considered in our analysis as a death from other causes.

Ximelagatran studies

No assumptions.

One participant had both initial ischaemic and subsequent haemorrhagic stroke. The former is included in the efficacy analyses and the latter in the safety analysis as two separate events.

The 10 deaths reported in participants who had already terminated the study are not accounted for in any analysis.

One participant who had two ischaemic strokes is counted twice in our efficacy analysis.

Selective reporting

All three review authors assessed selective reporting by cross‐checking the results reported in the original articles with those obtained from online trial registers and from the reports of pharmaceutical company websites. We included all reported outcome events in the analyses.

Other potential sources of bias

None detected.

Effects of interventions

Tests for statistical heterogeneity suggested low variability in treatment effects across studies for all outcomes analysed. However, we judged clinical heterogeneity to be moderate owing to differences in methodological aspects and variation in definitions of reported outcomes across studies.

Primary outcomes

Efficacy analysis

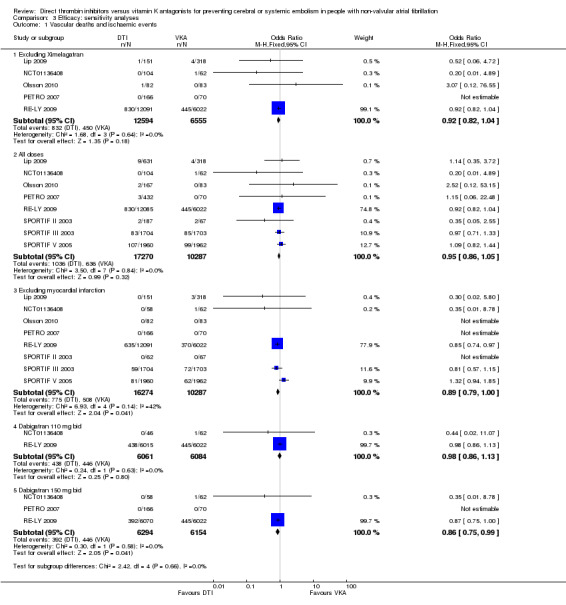

See Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 3.1

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Efficacy, Outcome 1 Vascular deaths and ischaemic events.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Efficacy: sensitivity analyses, Outcome 1 Vascular deaths and ischaemic events.

Vascular deaths and ischaemic events (including ischaemic strokes/transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs), non‐fatal systemic embolic events (SEE) and non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI)) were not significantly different between all DTIs and warfarin (odds ratio (OR) 0.94, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 1.05). The analysis of individual drugs within the class showed similar results for dabigatran versus warfarin (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.04), AZD0837 versus warfarin (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.06 to 4.72) and ximelagatran versus warfarin (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.26). Sensitivity analyses of individual doses of dabigatran showed that numerically fewer events were observed for both dabigatran doses but only dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was significantly superior to warfarin for the primary endpoint (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.99). When we excluded the studies examining ximelagatran, the results were unchanged. The analysis excluding MI favoured the DTIs slightly without reaching statistical significance (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.00).

Safety analysis

See Analysis 2.1 and Analysis 4.1

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Safety, Outcome 1 Fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Safety: sensitivity analyses, Outcome 1 Fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages.

Fatal and non‐fatal major haemorrhages, including haemorrhagic strokes, occurred less frequently with the DTIs compared with VKAs (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.97). The sensitivity analyses revealed that ximelagatran (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.92) and the individual dose of dabigatran 110 mg bid (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.94) contributed most to this result. Numerically, fewer events were observed with all other comparisons (dabigatran both doses versus warfarin, dabigatran 150 mg twice daily versus warfarin, AZD0837 versus warfarin), although none reached statistical significance.

Secondary outcomes

Adverse events

See Analysis 5.1 and Analysis 5.2

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse events, Outcome 1 Adverse events that lead to discontinuation of treatment.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Adverse events, Outcome 2 Serious adverse events.

We excluded studies of ximelagatran for this analysis because this drug was withdrawn from the market due to adverse effects on liver function. Importantly, the risk of transaminase elevation to three times the upper limit of normal was not increased either with dabigatran all doses versus warfarin (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13) or AZD0837 all doses versus warfarin (OR 1.52, 95% CI 0.60 to 3.86).

Adverse events other than bleeding and ischaemic events that led to treatment discontinuation were significantly more frequent with the DTIs compared with VKAs (OR 2.18, 95% CI 1.82 to 2.61).

Serious adverse events were also more frequent in the DTI group (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.56); these were significantly more frequent with dabigatran (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.12 to 1.63) but not with AZD0837 (OR 0.99, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.71).

All‐cause mortality

See Analysis 7.1

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Overall mortality, Outcome 1 Death from all causes.

Death from all causes occurred to a similar extent in both groups (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01). Death rates were slightly lower in the DTI group.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Deaths attributed to vascular causes and total ischaemic events (including ischaemic stroke/transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs), non‐fatal systemic embolic events (SEE) and non‐fatal myocardial infarction (MI)) were not significantly different between direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) and warfarin. Importantly, the analysis of individual doses showed that dabigatran 150 mg was superior to warfarin for this same endpoint.

Bleeding events ‐ namely fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages including haemorrhagic strokes ‐ were significantly lower with the DTIs. The overall estimate was mainly influenced by ximelagatran and by the dose of dabigatran 110 mg twice daily.

Other outcomes evaluated including adverse events that led to discontinuation of treatment were significantly more frequent in the DTI group. Deaths from all causes were comparable between the DTIs and warfarin.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Several aspects of this review attest to its completeness: (1) we conducted a thorough search and included data from published and unpublished studies in the analysis; (2) RE‐LY 2009 was complemented with its update publication by Conolly 2010 (included in RE‐LY 2009 references) and by the briefing document prepared by Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals for the FDA (Boehringer Ingelheim 2010 ‐ included in RE‐LY 2009 references), allowing us to break down composite endpoints accurately with minimal assumptions.

The assessment of the external validity of our results should take into consideration the following.

The eight studies that met the eligibility criteria were considered adequate to address the main objectives of the review. However, studies varied in important aspects: (a) design; (b) number of randomised participants; (c) duration of study, and (d) definitions of primary and secondary outcomes.

All studies were conducted at multiple sites and included participants from the US and Canada, Europe, Asia and Australia. However, fewer black people and Hispanics were enrolled compared to white people and Asians.

Populations were broadly similar for important participant characteristics relevant to the treatment in evaluation (age, stroke severity, type of atrial fibrillation (AF), exclusion of people with marked renal impairment) but they varied in other characteristics such as percentage of vitamin K antagonist (VKA)‐naïve participants included or concomitant antiplatelet therapy.

Time in the therapeutic range (TTR) varied across studies and across different sites within a given study. However, mean TTR was compatible with the one seen in sites with good control of warfarin therapy in everyday clinical practice (Baker 2009), thus avoiding underestimation of the benefits of the standard therapy.

Although challenging for combined analysis, the clinical heterogeneity across studies better supports the external validity of the results as this variation in participant populations is more likely to reflect practice in the real world.

Quality of the evidence

We included eight RCTs involving 27,623 participants and three DTIs. Studies were heterogeneous in their individual quality assessment; see Figure 4 and Figure 5. They also varied in design (phase II and phase III), primary and secondary analyses (intention‐to‐treat (ITT) versus per protocol (PP)) and displayed some diversity in the reporting of outcomes. Nonetheless, all eight studies were judged to be adequate to address the main objectives of the review.

SPORTIF V 2005 and RE‐LY 2009 analysed all randomised participants according to the ITT principle for primary outcomes. SPORTIF II 2003 and SPORTIF III 2003 describe an ITT analysis but three participants from each study were randomised and not analysed. Overall, 16 participants were randomised but not analysed. The remaining four studies performed a PP analysis only including participants who took at least one dose of study treatment. Secondary outcomes from SPORTIF III 2003 and SPORTIF V 2005 included in the safety analysis were based on an on‐treatment (OT) population that allowed a maximum continuous interruption of 30 days (or up to 60 days total) without study medication. Primary safety analyses in RE‐LY 2009 used the randomised set (ITT), and sensitivity analyses using the safety dataset (OT) were performed.

Potential biases in the review process

The risk of having introduced significant bias into the review process is small owing to the fact that all three review authors independently performed study selection, data abstraction and assessment of risk of bias, and cross‐checked them for reproducibility. Added to this, we carried out a comprehensive electronic search complemented with various other sources to minimise overall assumptions.

A limitation of our review is the lack of sufficient data to perform head‐to‐head comparisons between different DTIs. Combining all of them may introduce bias to both the efficacy and safety analyses, as we observed important differences between drugs that were not explained by drug class, such as the hepatotoxicity seen with ximelagatran that was not seen with the other DTIs, and some unexplained variations in bleeding effects across studies.

Another limitation is the relatively short evaluation periods. Anticoagulation in the AF population is intended to be long‐term, and there is therefore a chance that additional adverse events arise with longer periods of treatment. Moreover, people with AF tend to be older and to have more comorbidities and polypharmacy, which increases their risk of developing adverse events.

Importantly, a single study (RE‐LY 2009) represented 75% of the population analysed in our primary results. The dominant effect that this large study has on the overall estimates should be considered in the interpretation of results. Important differences could be present but undetected, given the smaller samples of the other studies.

Finally, we performed several post hoc sensitivity analyses, which may appear to introduce bias. However, the rationale for each analysis is extensively discussed and the findings clearly help in the interpretation of the protocol‐driven composite endpoints.

Publication bias must be considered due to the asymmetry of funnel plots and to the fact that no studies were found published in a language other than English.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

DTIs represent a major advance in stroke prevention in people with non‐valvular AF, as results from our analyses indicate a trend towards similar ‐ and perhaps superior ‐ effectiveness and increased safety. These results are in agreement with the findings from other recently published meta‐analyses: Capodanno 2012, Lip 2012 and Miller 2012. However, these meta‐analyses included drug classes other than DTIs, such as Factor Xa inhibitors, which are beyond the scope of our review.

When comparing our results with those from individual trials, it is important to consider that our primary outcomes were constructed in a different way from those from the original studies. The most relevant difference is that we excluded haemorrhagic stroke from our primary efficacy outcome. The rationale behind this exclusion is that AF does not cause haemorrhagic stroke itself, but anticoagulants do. Moreover, haemorrhagic stroke is not prevented by anticoagulants but rather is associated with their use. Therefore, haemorrhagic stroke belongs more appropriately to the primary safety outcome. The introduction of haemorrhagic stroke in the primary safety endpoint rather than in the primary efficacy endpoint does not undermine its critical clinical relevance. It merely places it where it more appropriately belongs.

For our composite primary efficacy endpoint of vascular deaths and ischaemic events, we found no difference between DTIs and warfarin. However, the sensitivity analysis for individual doses revealed that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin for this same endpoint. This is a concordance with the results from RE‐LY 2009 where the higher dose of dabigatran was found to be superior to warfarin for their primary efficacy outcome of stroke and SEE as well as for their outcome of vascular deaths, particularly those due to strokes. Importantly, our analysis shows that the benefits of dabigatran over warfarin are maintained even after removing the influence of including haemorrhagic strokes in the comparison.

The inclusion of vascular deaths in our primary efficacy endpoint is also clinically relevant because death may act as a competing risk factor for stroke/SEE (Schatzkin 1989). In a geriatric population with considerable comorbidities, the competing risk of death is especially high (Berry 2010). The inclusion of death in a composite endpoint is one way of addressing competing risks.

The efficacy endpoint in our review also included MI. The inclusion of this outcome in the composite endpoint can be controversial as it can be argued that the pathophysiology of MI differs from that of stroke and other embolic events. However, we deemed this inclusion appropriate based on its clinical relevance and the fact that a recent meta‐analysis of seven trials that evaluated dabigatran for various indications found a higher risk of MI compared with warfarin (Uchino 2012). Also, in the RE‐LY 2009 trial, the frequency of MI was greater in participants receiving dabigatran than in those treated with warfarin. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding MI to assess the impact of having included this outcome in the comparison. As expected, the results tended to favour the DTIs but without reaching statistical significance.

We also considered pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) in our primary analysis as systemic embolic events. The consideration was based on the fact that systemic embolism was defined in the largest included study as an acute non‐intracerebral and non‐coronary vascular event. Although the pathophysiology of arterial and venous thrombosis differs in many aspects, the inclusion of these events in the composite outcome seems reasonable per study definitions. RE‐LY 2009 showed slightly higher rates of PE events in both dabigatran groups compared with warfarin but the overall number of these events was low. Both MI and PE were considered as efficacy outcomes in RE‐LY 2009 but the authors did not include either of them in the primary efficacy analysis. This is important because the efficacy of the DTI was comparable to that of warfarin in our analysis even after the introduction of MI and PE in the composite endpoint.

Our safety analysis was designed to evaluate fatal and non‐fatal haemorraghic events referring to major bleeds rather than overall bleeding events, because major bleeds carry important clinical consequences relevant to health professionals when deciding whether or not to use an anticoagulant. A reduction in major bleeding is of particular clinical relevance, as there is increasing evidence to support a significant association between a major haemorrhagic event and adverse prognosis as indicated by an increased risk of death in people with AF (Sharma 2012). In our safety analysis, DTIs were found to be superior to warfarin with fewer fatal and non‐fatal haemorraghic events including haemorrhagic strokes. The sensitivity analyses showed that this favourable result was mainly influenced by ximelagatran and dabigatran at the dose of 110 mg twice daily. Interestingly, although numerically fewer major bleeding events were seen in all three SPORTIF trials, none of the individual studies found a statistically significant difference between the DTI and warfarin. In contrast, RE‐LY 2009 did report a significant reduction in the occurrence of major bleeding events with both doses of dabigatran compared with warfarin.

In the evaluation of new drugs, the assessment of adverse events is fundamental. However, the possibility of researcher bias needs to be considered in this analysis. Researcher bias refers to investigators having more stringent discontinuation criteria for the new treatment in comparison with a standard drug with which they have more experience and feel more comfortable. Since warfarin was given in an open‐label fashion in most studies, this bias could be important. Our analysis included only events that led to treatment discontinuation because participant compliance with long‐term treatment is of critical importance in dealing with chronic conditions like stroke prevention in AF. Our analysis showed that the adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred more frequently with the DTIs compared with warfarin. The most frequent adverse events were gastrointestinal complaints. Interestingly, the analysis of individual drugs showed that adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were significantly more frequent with dabigatran than with AZD0837.

Finally, we found all‐cause mortality to be comparable between DTIs and VKAs. The results are in agreement with RE‐LY 2009, where fewer overall deaths were observed in both dabigatran groups compared with the warfarin group, although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The odds of preventing a vascular death or ischaemic event (including ischaemic stroke, transient ischaemic attack, systemic embolic events and myocardial infarction) did not differ substantially between the direct thrombins inhibitors (DTIs) and vitamin K antagonists (VKAs), meaning that DTIs are as efficacious as VKAs to prevent all these clinically relevant outcomes. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was superior to warfarin for this composite endpoint. Fewer major haemorraghic events, including haemorrhagic strokes, were observed with the DTIs, making these new drugs easily administered safe alternatives to adjusted‐dose warfarin. The impact of the higher dose of dabigatran on vascular deaths and ischaemic events is important because it indicates that the advantage of dabigatran compared with warfarin is not limited to effects on bleeding. Thus, in the not infrequent clinical scenario where warfarin administration or monitoring poses significant difficulties, DTIs appear promising. Nonetheless, people on DTIs should still be carefully monitored, as concerns remain with the lack of drug antidote and compliance, given the need for twice daily administration. Several additional factors exist, such as comorbid conditions including reduced renal function, side‐effect profile, cost and patient preference. Therefore, the need to consider the balance of benefit and risk in each individual is no less important than with VKA therapy.

Implications for research.

Our review has evaluated all DTIs combined versus warfarin. However, an important gap in the evidence is the lack of comparisons between different drug classes (e.g. DTIs versus Factor Xa inhibitors) and between different drugs within a class. This should be assessed in future research through multicentre randomised controlled trials comparing newer anticoagulants with each other and through network meta‐analyses. Also, the mean evaluation period across studies was about two years. Since anticoagulation in people with non‐valvular AF is long‐term, it is possible that additional adverse effects may arise with more prolonged use. Observational studies and US Food and Drug Administration‐European Medicines Agency pharmacovigilance should be considered to address this issue.

Finally, the superiority of dabigatran 150 mg compared with warfarin came from a post hoc sensitivity analysis and was found to be borderline statistically significant. Hence, future studies could assess this finding as a primary analysis.

Feedback

Feedback, 17 October 2014

Summary

In the review of direct thrombin inhibitors (DTIs) compared to warfarin for prevention of cerebral and systemic embolism1, the primary composite outcome includes vascular death and ischemic events. It would be more clear and consistent if the title reflected the primary outcome assessed. More importantly, we question the use of the chosen composite primary efficacy outcome and hope that you can elaborate. The justification for choosing vascular deaths in the primary efficacy endpoint was that death may act as a significant competing risk factor for stroke and systemic embolism in an elderly population. In addition, to adjust for death as a competing risk in a composite, total mortality should be included, not a cause specific death2. It appears that you are trying to capture the net impact of DTIs. However, this implies that DTIs have impact only on vascular deaths and ischemic events and no other clinically relevant outcomes. In addition, we found it difficult to interpret the results of the composite primary efficacy outcome for several reasons. First, the definitions used for vascular deaths and ischemic events differed from those used in the clinical trials. Iin the RELY trial, vascular deaths excluded any death deemed to be non‐vascular in nature and included fatal hemorrhage and cardiovascular death. In contrast, the review excluded fatal hemorrhages and cardiovascular deaths (e.g. sudden arrhythmia, pump failure). Using the data from the RELY trial3 and FDA medical review4, we were unable to replicate the same numbers presented in the forest plot for vascular deaths and ischemic events in the publication of the RELY trial. Secondly, it would be useful to present the event rates for individual components of the primary composite outcome separately. Although there was no statistically significant difference in your analysis of the composite outcome of vascular deaths and ischemic events between DTIs and warfarin, this does not necessarily mean the individual components also occurred at a similar frequency. It is possible that one component of the composite may be increasing while another is decreasing and this information would be valuable to clinicians and patients, especially given that their clinical importance may not be perceived as equal4.

It is noted that the RELY trial3 with dabigatran contributed 75% of the data analyzed in the primary analysis. Thus, the results of the systematic review are heavily reliant on a single open‐label RCT, which is associated with a significant risk of bias. In the risk of bias assessment of the RELY trial, the blinding of outcome assessors was judged to be adequate and at low risk of bias. According to the US FDA approval medical review4, major issues were identified in regards to the case report forms that were seen by the adjudication committee. In a verification analysis of a sample of events, 20% of documented events showed evidence of the presence of unblinding. In other words, the adjudicators would have known what study treatments the patients were on. In addition, the risk of bias due to inadequate blinding for participants or personnel was stated as unclear. Given that warfarin was open‐label and required regular follow‐up with health‐care professionals, we believe it is possible that more visits for INR monitoring might have led to more events being captured, even though those were not clinical visits in the usual sense. All outcomes are potentially subject to performance and ascertainment bias. This is also supported by the FDA review which stated that the lack of blinding of patients and clinicians led to differential treatment of patients during the study period. In accordance with Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias, the domains of blinding of outcome assessors and blinding of participants and personnel satisfy the criteria for high risk of bias. Lack of or unclear blinding of treatment assignment is associated with a 13% exaggeration of the experimental treatment effect6. Given this information, we suggest that rating for blinding be changed to high risk and the implications of this be discussed. We feel readers need to be aware of these biases and their implications to make informed conclusions.

The review states that "DTIs are easily administered safe alternatives to warfarin" and "potentially safer in people at high risk". We disagree with these statements. First, according to the exclusion criteria of the RELY trial, patients at high risk for bleeding events, including those with recent gastrointestinal bleeds, prior intracranial hemorrhage and contraindications to warfarin therapy were not eligible for trial entry. Second, ximelegatran has been removed from the market as a result of hepatotoxicity, and AZD0837 is under investigation and not currently available for clinical use. The aforementioned statement should change to make it clear that dabigatran is the only DTI currently available. Third, the review demonstrates that fatal and non‐fatal major hemorrhages (including hemorrhagic strokes) are reduced with DTIs. The review also states that all‐cause mortality is not statistically significant but death rates are "slightly lower" in the DTI group. We find this statement and terminology of "slightly lower" misleading. It would be helpful to provide the death rates in the text to support this claim and we would recommend against framing the non‐significant finding in wishful terms, a practice that is discouraged by the Cochrane Handbook (see section 12.7.4 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions). Furthermore, one would rationalize that if fatal and non‐fatal hemorrhages are decreasing, there would be a corresponding reduction in total serious adverse events (SAEs). To claim increased safety and net benefit of DTIs, there would need to be a decrease in total SAEs. In fact, the review finds an increased risk of SAEs and twice the risk of discontinuing treatment due to adverse events with the DTIs compared with warfarin. The observed discordance may imply that an increase in other SAEs is offsetting the beneficial reduction in hemorrhagic outcomes. This was also the case in the RELY trial, even though the outcomes of stroke, systemic embolism and bleeding were not appropriately included as SAEs3 (C Chen, personal communication, December 2010). In addition, major bleeding events were only counted in the RELY trial up to six days after discontinuing therapy and we feel that additional bleeding events after this time could have been missed for either treatment arm (K Li, personal communication, May 2014 ). Several recent publications also report on subsequent re‐countings of the initial data of bleeding events in study participants of the RELY trial, casting further doubt on the perceived safety of dabigatran7, 8, 9.

At this time, we do not feel that the available data supports a claim of increased safety with the DTIs and the issues identified should be incorporated into the discussion and used to revise the conclusion. Finally, "replication of a significant result is by no means guaranteed" (e.g. if first experiment P value = 0.05, then chance of replication is approximately 50%)10. Therefore, we feel that any firm conclusions regarding safety or efficacy of dabigatran is premature given the results of the RELY trial lack replication. Thank you for your attention to our concerns.

References

Salazar CA, del Aguila D, Cordova EG. Direct thrombin inhibitors versus vitamin K antagonists for preventing cerebral or systemic embolism in people with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 3. Art. No.:CD009893.

Kleist P. Composite endpoints for clinical trials, current perspectives. Int J Pharm Med 2007; 21(3):187‐198.

Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine 2009; 361(12):1139‐51.

U.S Food and Drug Administration. Drugs@FDA. FDA Approved Drug Products. [Internet]. Available from http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/Scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm.

Freemantle N, Calvert M, Wood J, Eastaugh J, Griffin C. Composite outcomes in randomized trials: greater precision but with greater uncertainty. JAMA 2003; 289:2554‐9.

Savovic J, et al. Influence of reported study design characteristics on intervention effect estimates from randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157:429‐38.

Cohen D. Dabigatran: how the drug company withheld important analyses. BMJ 2014;349:4670 Cohen D. Concerns over data in key dabigatran trial. BMJ 2014; 349:4747.

Connolly S, Wallentin L, Yusuf S. Additional events in the RE‐LY trial. New England Journal of Medicine 2014.

Wood J, Freemantle N, King M, Nazareth I. Trap of trends to statistical significance: likelihood of near significant p value becoming more significant with extra data. BMJ 2014; 348.

We agree with the conflict of interest statement below: We certify that we have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with a financial interest in the subject matter of our feedback. Sarah Burgess, Cait O’Sullivan, Aaron M Tejani

Reply

To date, no reply has been forthcoming from the review authors.

Contributors

Feedback authors: Sarah Burgess, Cait O’Sullivan, Aaron M Tejani

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 March 2016 | Feedback has been incorporated | Feedback added; awaiting response from the review authors |

Acknowledgements

We thank the Cochrane Stroke Group for its guidance and helpful collaboration during the development of this review. And special thanks to our parents for their never‐ending support.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials search strategy

#1 MeSH descriptor Atrial Fibrillation, this term only

#2 MeSH descriptor Atrial Flutter, this term only

#3 (atrial or atrium or auricular) near5 (fibrillation* or arrhythmia* or flutter*):ti,ab,kw

#4 (AF):ti,ab,kw

#5 (#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4)

#6 MeSH descriptor Thrombin, this term only with qualifier: AI

#7 (direct* near5 thrombin near5 inhib*):ti,ab,kw

#8 (DTI or DTIs)

#9 MeSH descriptor Antithrombins explode all trees

#10 MeSH descriptor Hirudin Therapy, this term only

#11 (argatroban or MD805 or MD‐805 or dabigatran or ximelagatran or melagatran or efegatran or flovagatran or inogatran or napsagatran or bivalirudin or lepirudin or hirudin* or desirudin or desulfatohirudin or hirugen or hirulog or AZD0837 or bothrojaracin or odiparcil):ti,ab,kw

#12 (#6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11)

#13 MeSH descriptor Warfarin, this term only

#14 (warfarin* or adoisine or aldocumar or athrombin* k or carfin or coumadin* or coumafene or coumaphene or jantoven or kumatox or lawarin or marevan or panwarfarin or panwarfin or prothromadin or sofarin or tedicumar or tintorane or waran or warfant or warfilone or warnerin):ti,ab,kw

#15 MeSH descriptor Vitamin K explode all trees with qualifier: AI

#16 (vitamin K antagonist* or VKA or VKAs):ti,ab,kw

#17 MeSH descriptor Coumarins, this term only

#18 MeSH descriptor 4‐Hydroxycoumarins explode all trees

#19 MeSH descriptor Phenindione, this term only

#20 (coumarin* or cumarin* or phenprocoum* or phenprocum* or dicoumar* or dicumar* or acenocoumar* or acenocumar* or fluindione or phenindione or clorindione or diphenadione):ti,ab,kw

#21 (#13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20)

#22 (#5 AND #12 AND #21)

Appendix 2. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

1. atrial fibrillation/ or atrial flutter/

2. ((atrial or atrium or auricular) adj5 (fibrillation$ or arrhythmia$ or flutter$)).tw.

3. AF.tw.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. thrombin/ai

6. (direct$ adj5 thrombin adj5 inhib$).tw.

7. exp antithrombins/ or hirudin therapy/.

8. DTI$1.tw.

9. (argatroban or MD805 or MD‐805 or dabigatran or ximelagatran or melagatran or efegatran or flovagatran or inogatran or napsagatran or bivalirudin or lepirudin or hirudin$ or desirudin or desulfatohirudin or hirugen or hirulog or AZD0837 or bothrojaracin or odiparcil).tw.

10. (argatroban or MD805 or MD‐805 or dabigatran or ximelagatran or melagatran or efegatran or flovagatran or inogatran or napsagatran or bivalirudin or lepirudin or hirudin$ or desirudin or desulfatohirudin or hirugen or hirulog or AZD0837 or bothrojaracin or odiparcil).nm.

11. 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10

12. Warfarin/

13. (warfarin$ or adoisine or aldocumar or athrombin$ k or carfin or coumadin$ or coumafene or coumaphene or jantoven or kumatox or lawarin or marevan or panwarfarin or panwarfin or prothromadin or sofarin or tedicumar or tintorane or waran or warfant or warfilone or warnerin).tw.

14. (warfarin$ or adoisine or aldocumar or athrombin$ k or carfin or coumadin$ or coumafene or coumaphene or jantoven or kumatox or lawarin or marevan or panwarfarin or panwarfin or prothromadin or sofarin or tedicumar or tintorane or waran or warfant or warfilone or warnerin).nm.

15. exp Vitamin K/ai [Antagonists & Inhibitors]

16. (vitamin K antagonist$ or VKA or VKAs).tw.

17. 4‐hydroxycoumarins/ or acenocoumarol/ or coumarins/ or dicumarol/ or ethyl biscoumacetate/ or phenindione/ or phenprocoumon/

18. (coumarin$ or cumarin$ or phenprocoum$ or phenprocum$ or dicoumar$ or dicumar$ or acenocoumar$ or acenocumar$ or fluindione or phenindione or clorindione or diphenadione).tw.

19. (coumarin$ or cumarin$ or phenprocoum$ or phenprocum$ or dicoumar$ or dicumar$ or acenocoumar$ or acenocumar$ or fluindione or phenindione or clorindione or diphenadione).nm.

20. 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19

21. 4 and 11 and 20

Appendix 3. EMBASE (Ovid) search strategy

1. heart atrium arrhythmia/ or heart atrium fibrillation/ or heart atrium flutter/

2. ((atrial or atrium or auricular) adj5 (fibrillation$ or arrhythmia$ or flutter$)).tw.

3. AF.tw.

4. 1 or 2 or 3

5. exp thrombin inhibitor/

6. (direct$ adj5 thrombin adj5 inhib$).tw.

7. DTI$1.tw.

8. (argatroban or MD805 or MD‐805 or dabigatran or ximelagatran or melagatran or efegatran or flovagatran or inogatran or napsagatran or bivalirudin or lepirudin or hirudin$ or desirudin or desulfatohirudin or hirugen or hirulog or AZD0837 or bothrojaracin or odiparcil).tw.

9. 5 or 6 or 7 or 8

10. exp coumarin anticoagulant/

11. antivitamin K/

12. (warfarin$ or adoisine or aldocumar or athrombin$ k or carfin or coumadin$ or coumafene or coumaphene or jantoven or kumatox or lawarin or marevan or panwarfarin or panwarfin or prothromadin or sofarin or tedicumar or tintorane or waran or warfant or warfilone or warnerin).tw.

13. (vitamin K antagonist$ or VKA or VKAs).tw.

14. (coumarin$ or cumarin$ or phenprocoum$ or phenprocum$ or dicoumar$ or dicumar$ or acenocoumar$ or acenocumar$ or fluindione or phenindione or clorindione or diphenadione).tw.

15. 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14

16. 4 and 9 and 15

17. limit 16 to human

18. Randomized Controlled Trial/

19. Randomization/

20. Controlled Study/

21. control group/

22. clinical trial/ or phase 1 clinical trial/ or phase 2 clinical trial/ or phase 3 clinical trial/ or phase 4 clinical trial/ or controlled clinical trial/

23. Double Blind Procedure/

24. Single Blind Procedure/ or triple blind procedure/

25. placebo/

26. drug comparison/ or drug dose comparison/

27. "types of study"/

28. Comparative Study/

29. random$.tw.

30. (controlled adj5 (trial$ or stud$)).tw.

31. (clinical$ adj5 trial$).tw.

32. ((control or treatment or experiment$ or intervention) adj5 (group$ or subject$ or patient$)).tw.

33. (quasi‐random$ or quasi random$ or pseudo‐random$ or pseudo random$).tw.

34. ((singl$ or doubl$ or tripl$ or trebl$) adj5 (blind$ or mask$)).tw.

35. placebo$.tw.

36. (assign$ or alternate or allocat$).tw.

37. controls.tw.

38. trial.ti.

39. or/18‐38

40. 17 and 39

Appendix 4. BVS LILACS search strategy

(tw:(direct thrombin inhibitor)) AND (tw:(atrial fibrillation)) AND (tw:(warfarin)) AND (tw:(trial))

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Efficacy.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vascular deaths and ischaemic events | 8 | 26601 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.85, 1.05] |

| 1.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18509 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.82, 1.04] |

| 1.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.06, 4.72] |

| 1.3 Ximelagatran | 3 | 7458 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.02 [0.83, 1.26] |

Comparison 2. Safety.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages | 8 | 26601 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.78, 0.97] |

| 1.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18509 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.82, 1.03] |

| 1.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [0.03, 1.10] |

| 1.3 Ximelagatran | 3 | 7458 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.55, 0.92] |

Comparison 3. Efficacy: sensitivity analyses.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vascular deaths and ischaemic events | 8 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Excluding Ximelagatran | 5 | 19149 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.82, 1.04] |

| 1.2 All doses | 8 | 27557 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.86, 1.05] |

| 1.3 Excluding myocardial infarction | 8 | 26561 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.79, 1.00] |

| 1.4 Dabigatran 110 mg bid | 2 | 12145 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.86, 1.13] |

| 1.5 Dabigatran 150 mg bid | 3 | 12448 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.75, 0.99] |

Comparison 4. Safety: sensitivity analyses.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Fatal and non‐fatal haemorrhages | 8 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Excluding Ximelagatran | 5 | 19143 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.81, 1.02] |

| 1.2 All doses | 8 | 27557 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.78, 0.96] |

| 1.3 Dabigatran 110 mg bid | 2 | 12145 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.71, 0.94] |

| 1.4 Dabigatran 150 mg bid | 3 | 12448 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.89, 1.16] |

Comparison 5. Adverse events.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Adverse events that lead to discontinuation of treatment | 5 | 19143 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.18 [1.82, 2.61] |

| 1.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18509 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.12 [1.77, 2.56] |

| 1.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.75 [1.79, 12.57] |

| 2 Serious adverse events | 5 | 19077 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.31 [1.09, 1.56] |

| 2.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18443 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [1.12, 1.63] |

| 2.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.57, 1.71] |

Comparison 6. Hepatotoxicity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 ALT or AST > 3x ULN | 5 | 19980 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.76, 1.16] |

| 1.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18781 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.74, 1.13] |

| 1.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 1199 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.52 [0.60, 3.86] |

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Hepatotoxicity, Outcome 1 ALT or AST > 3x ULN.

Comparison 7. Overall mortality.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Death from all causes | 8 | 26601 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.83, 1.01] |

| 1.1 Dabigatran | 3 | 18509 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.80, 1.01] |

| 1.2 AZD0837 | 2 | 634 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.02, 8.76] |

| 1.3 Ximelagatran | 3 | 7458 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.78, 1.17] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Lip 2009.

| Methods | Study design: RCT, dose guiding, safety study Power calculation: not specified Number of participants randomised: 955 (AZD0837: 636; VKA: 319) Number of participants analysed: 949 Number of exclusions post‐randomisation: 6 Number of withdrawals and reasons: AZD0837 groups: 56 (8.9%) prematurely discontinued study and 106 (16.8%) prematurely discontinued treatment. VKA group: 15 (4.7%) prematurely discontinued study and 25 (7.9%) prematurely discontinued treatment. The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment were gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhoea, flatulence, or nausea ITT analysis: no Treatment within target INR: 57% to 68% Source of funding: pharmaceutical: AstraZeneca |

|

| Participants | Country: Austria, Denmark, Hungary, Ireland, Norway, Poland, Russia, Sweden, UK Setting/location: hospitals Number of centres: 95 Age: 68 Sex: 68% male Inclusion criteria

Exlusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Treatments: participants were randomised into 4 parallel groups: 4 groups receiving AZD0837 extended‐release tablets (150, 300, or 450 mg od or 200 mg bid) Control: VKA (warfarin) with target INR: 2.0 to 3.0 Duration: 142 days |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Computer‐generated scheme |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Central randomisation through interactive web response system |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Double‐blind for AZD0837 doses but open for VKA |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | It is mentioned that participant, caregiver and investigator were blinded; nevertheless the methodology is not specified |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | A greater proportion of participants in the AZD0837 treatment groups (9.2%) discontinued study treatment than in the VKA treatment group (1.6%). The reasons for treatment abandonment are not specified, it is only reported that the most common reasons for discontinuation were gastrointestinal disorders. Nevertheless, participants were analysed as if they were in the original randomisation group |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The study is registered in clinicaltrials.gov and their outcomes are reported according to that guideline. Protocol could not be found |

NCT01136408.

| Methods | Study design: RCT, safety study Power calculation: not specified Number of participants randomised: 174 (dabigatran: 112; VKA: 62) Number of participants analysed: 166 Number of exclusions post‐randomisation: 8 Number of withdrawals and reasons: not specified ITT analysis: no Treatment within target INR: not specified Source of funding: pharmaceutical: Boehringer Ingelheim |

|

| Participants | Country: Japan Setting/location: Boehringer Ingelheim investigational sites and 1 hospital Number of centres: 28 Age: not specified Sex: both, proportion not specified Inclusion criteria

Exlusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Treatments: dabigatran etexilate 110 mg and 150 mg bid Control: VKA (warfarin) with target INR: 2.0 to 3.0 Duration: 84 days |

|

| Outcomes | Primary outcomes

Secondary outcomes

|

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not specified |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | High risk | Open‐label study |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | There is no information regarding treatment discontinuation. Adverse events are not assessed properly |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | The study is registered in clinicaltrials.gov and their outcomes are reported according to that guideline. Protocol could not be found |

Olsson 2010.

| Methods | Study design: RCT, dose guiding, safety study Power calculation: not specified Number of participants randomised: 250 (AZD0837: 167; VKA: 83) Number of participants analysed: 249 Number of exclusions post‐randomisation: 1 Number of withdrawals and reasons: AZD0837 groups: 8 (4.7%) prematurely discontinued study and 15 (9.0%) prematurely discontinued treatment. VKA group: 1 (1.2%) prematurely discontinued study and 1 (1.2%) prematurely discontinued treatment. The most common adverse events leading to discontinuation of treatment were: gastrointestinal disorders, such as diarrhoea, flatulence, or nausea; and cardiac disorders with ischaemic or arrhythmic origin ITT analysis: no Treatment within target INR: 60% to 71% Source of funding: pharmaceutical: AstraZeneca |

|

| Participants | Country: Denmark, Norway, Sweden Setting/location: hospitals Number of centres: 20 Age: 71 Sex: 78% male Inclusion criteria

Exlusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Treatments: participants were randomised into 2 groups: AZD0837 150 mg and 350 mg immediate‐release tablets bid Control: VKA (warfarin) with target INR: 2.0 to 3.0 Duration: 91 days |

|